Submitted:

09 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

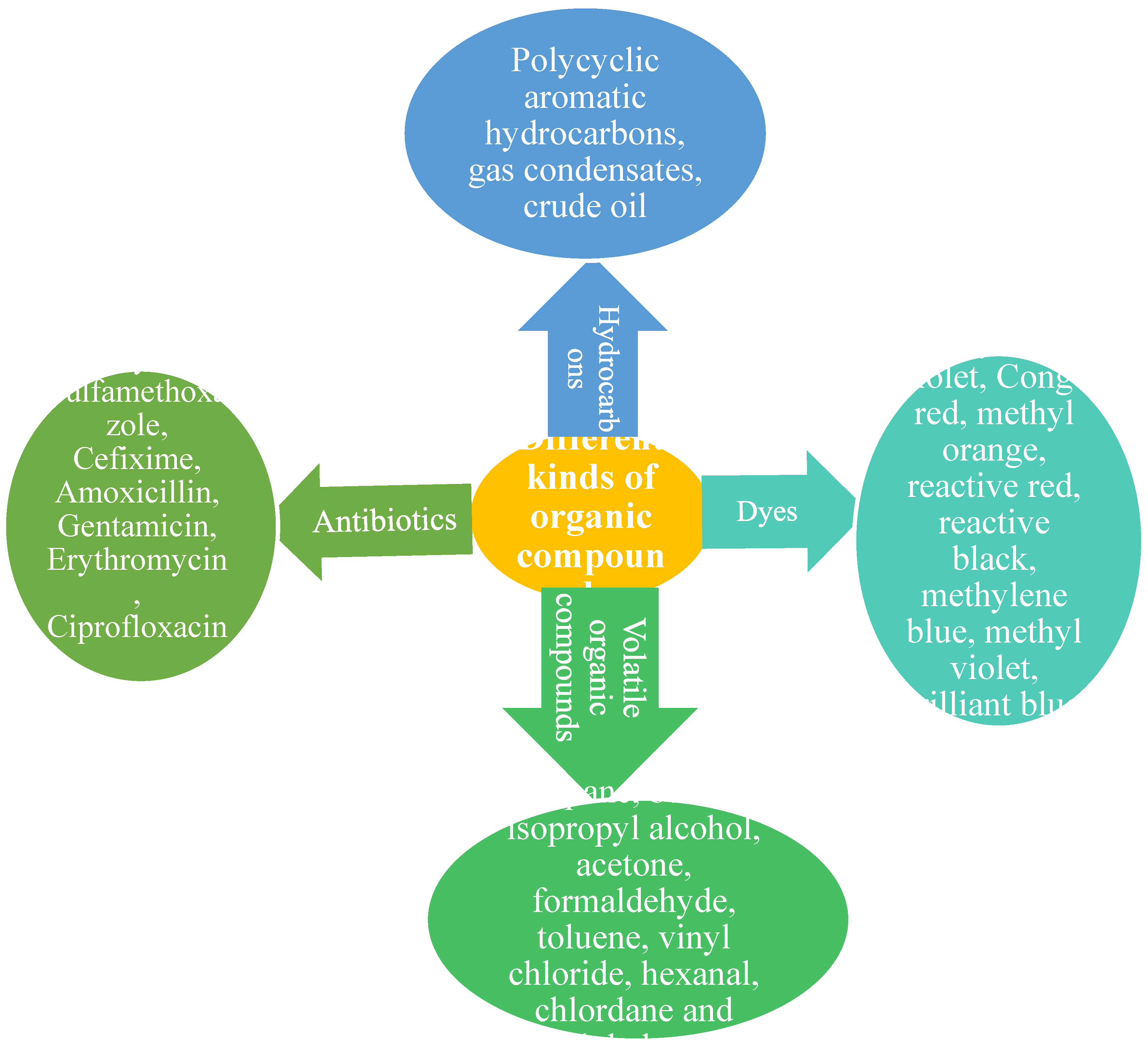

2. Organic Pollutants

3. TiO2 Photocatalyst

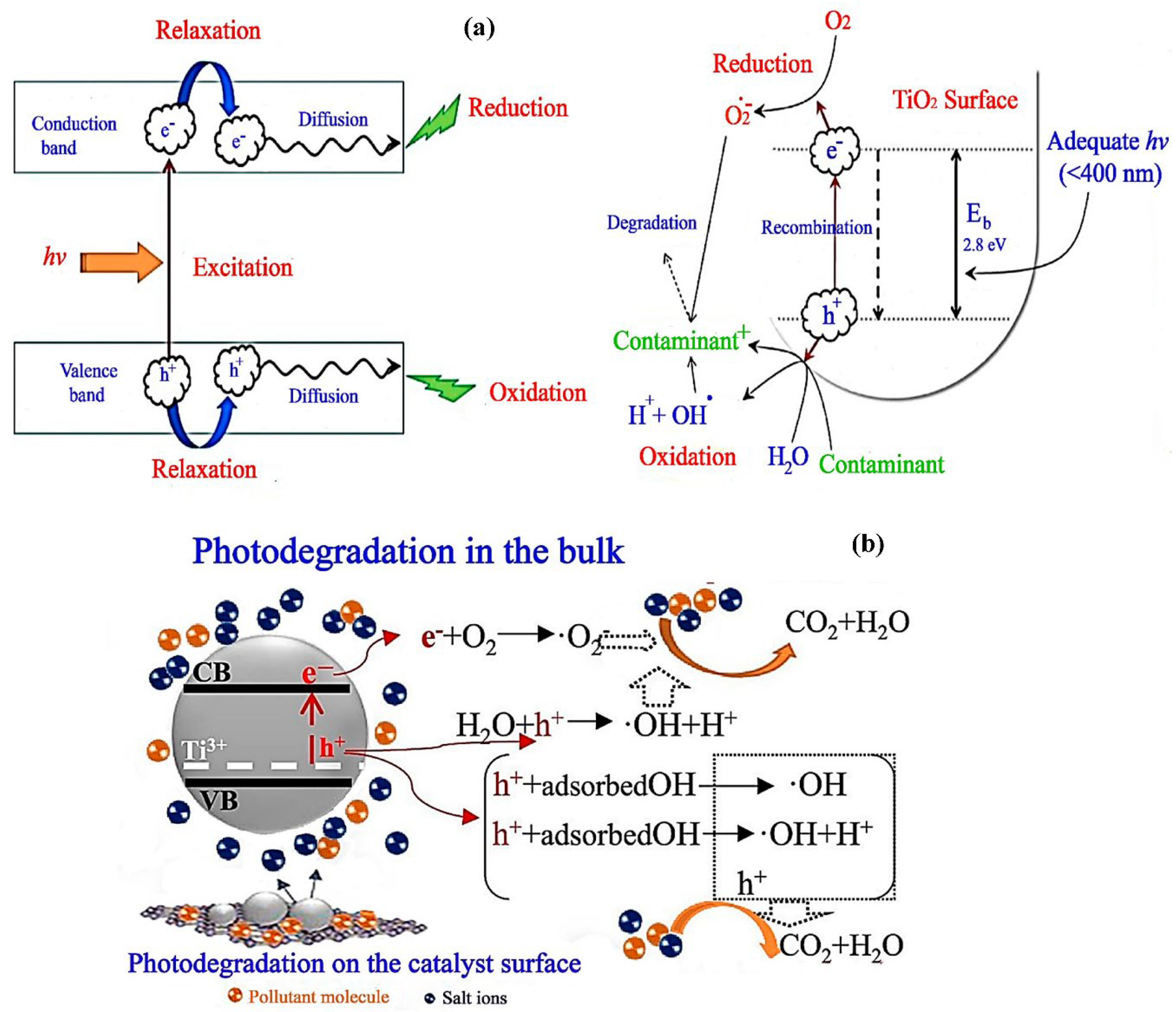

3.1. Features and Reaction Mechanism of TiO2 Photocatalyst

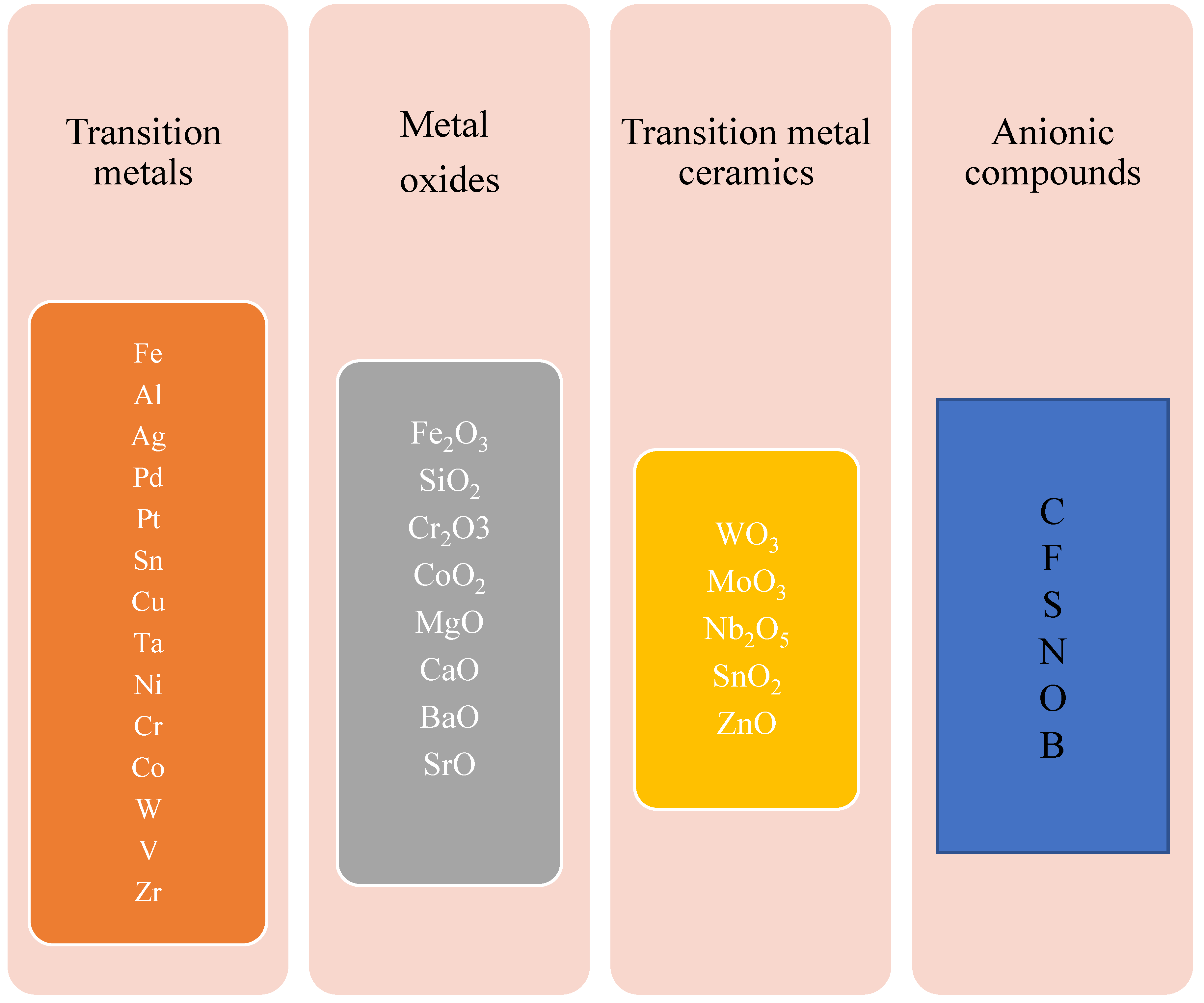

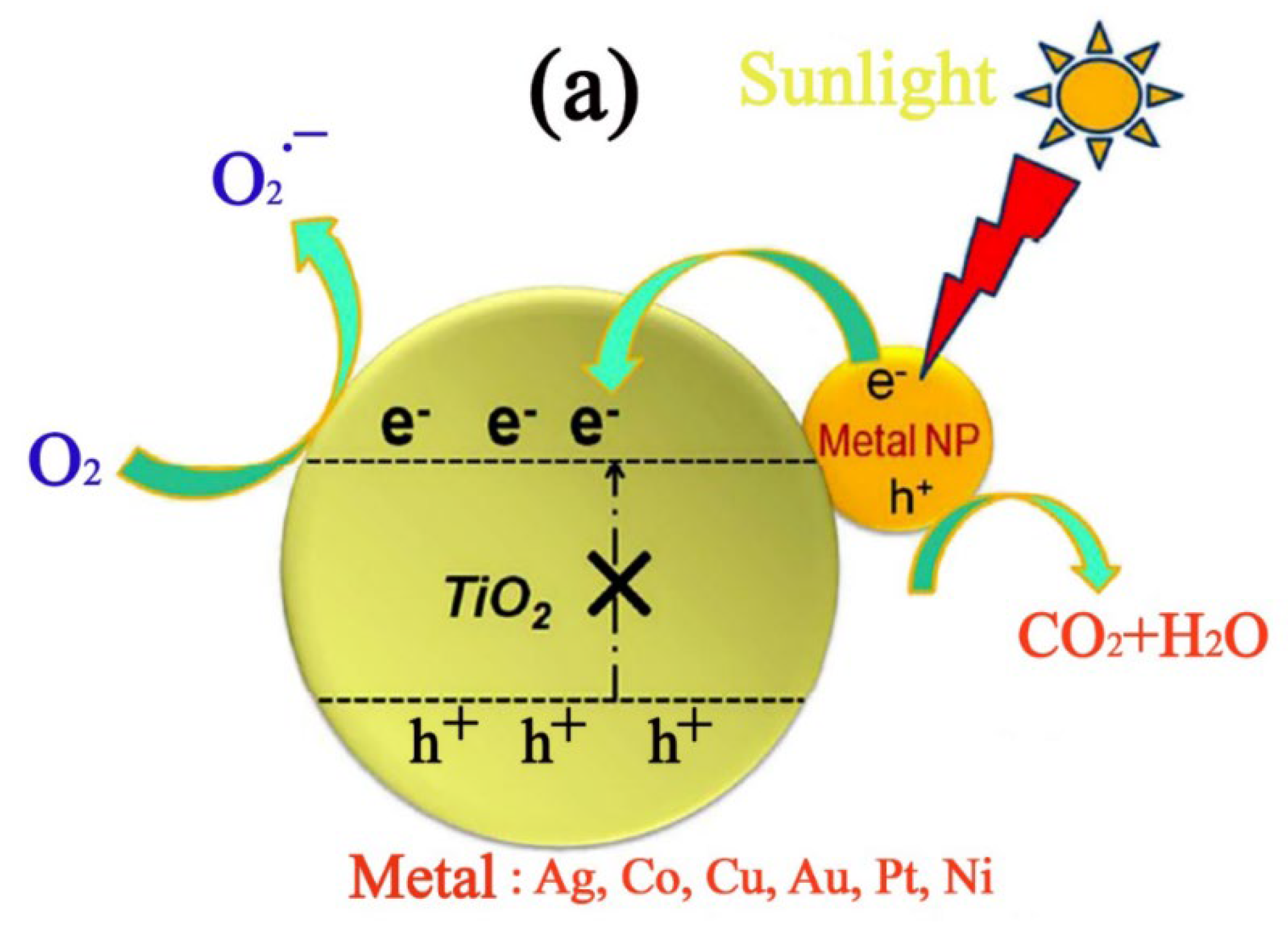

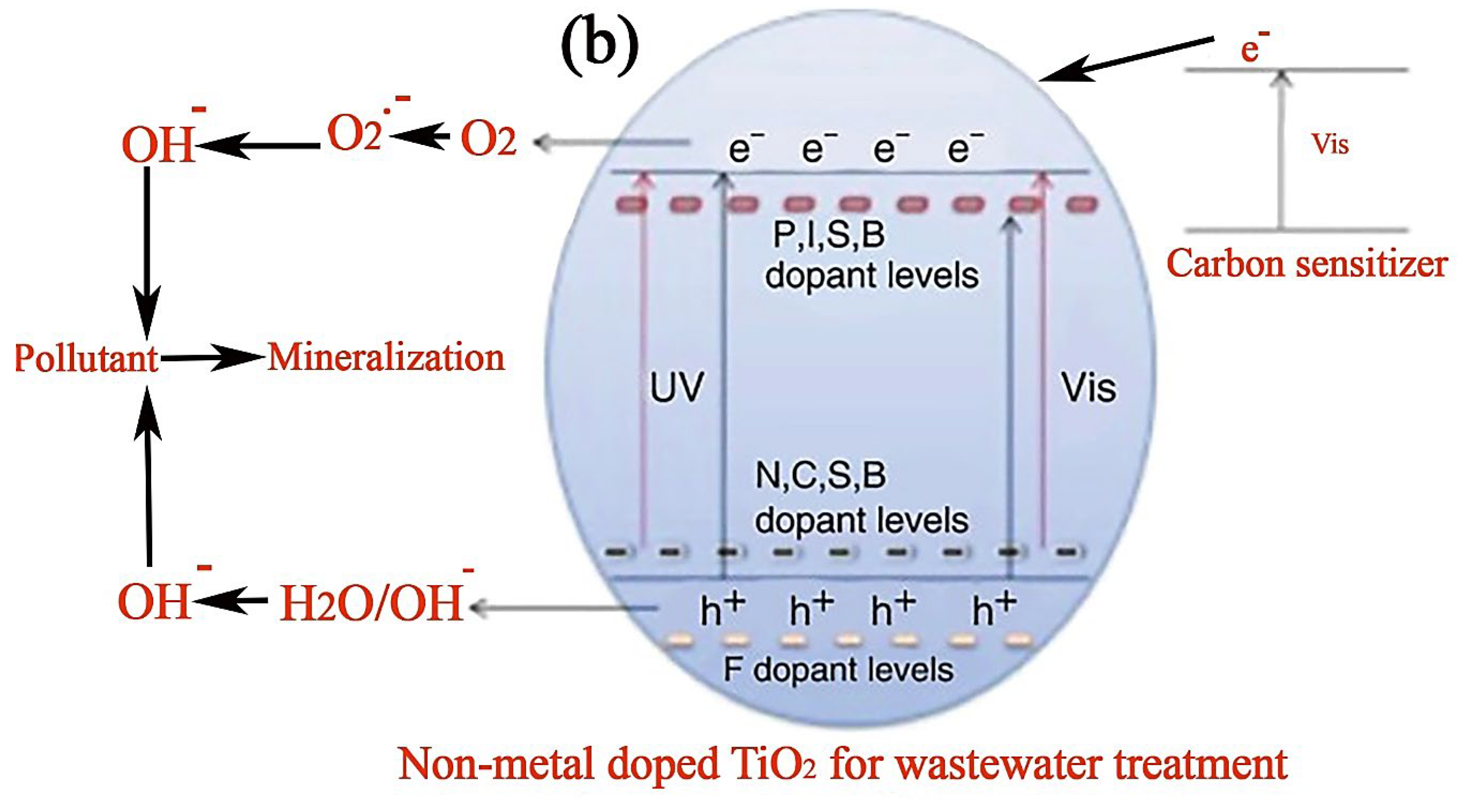

3.2. Improved Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Using Metallic and Non-Metallic Dopants

4. ZnO nano-photocatalyst

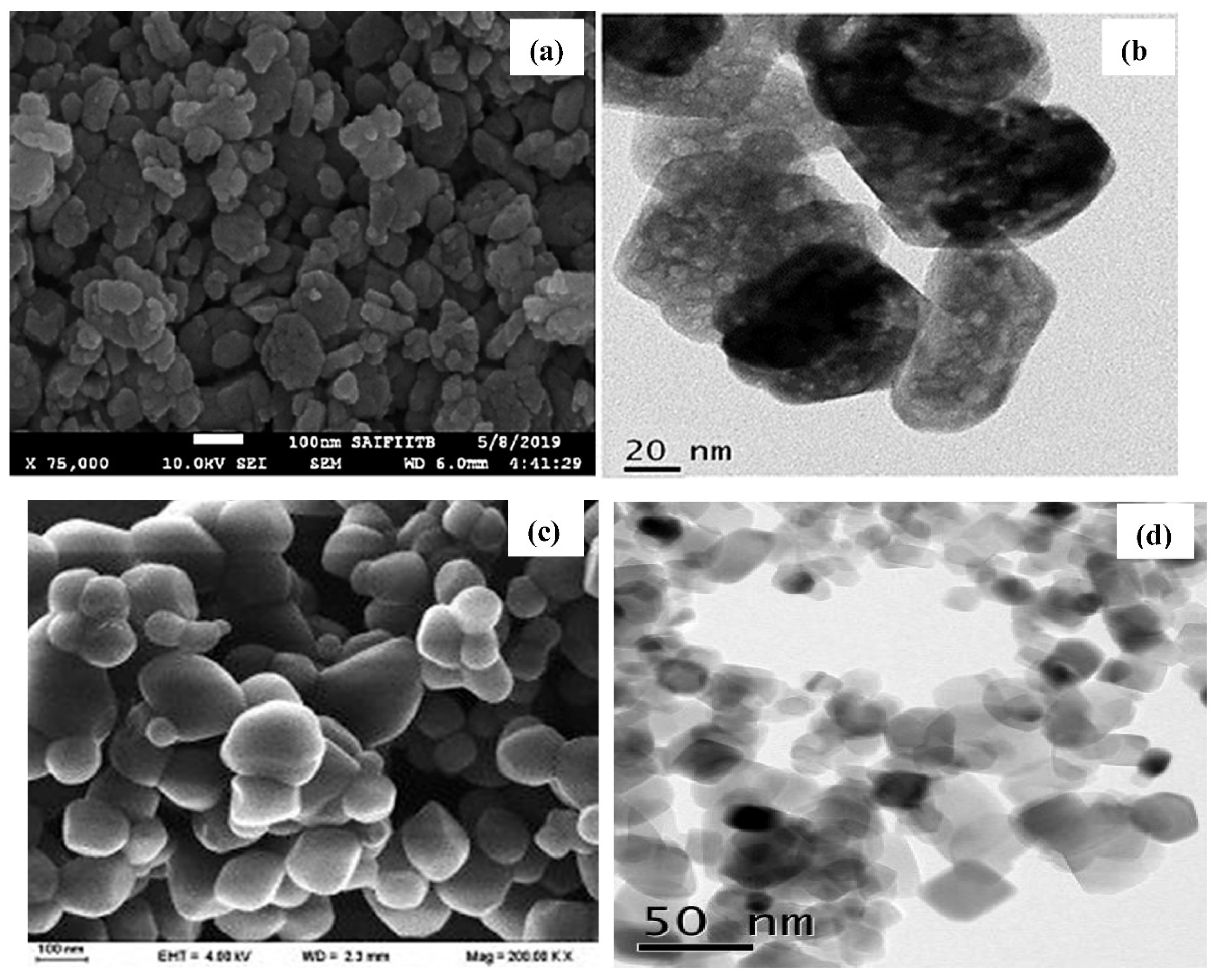

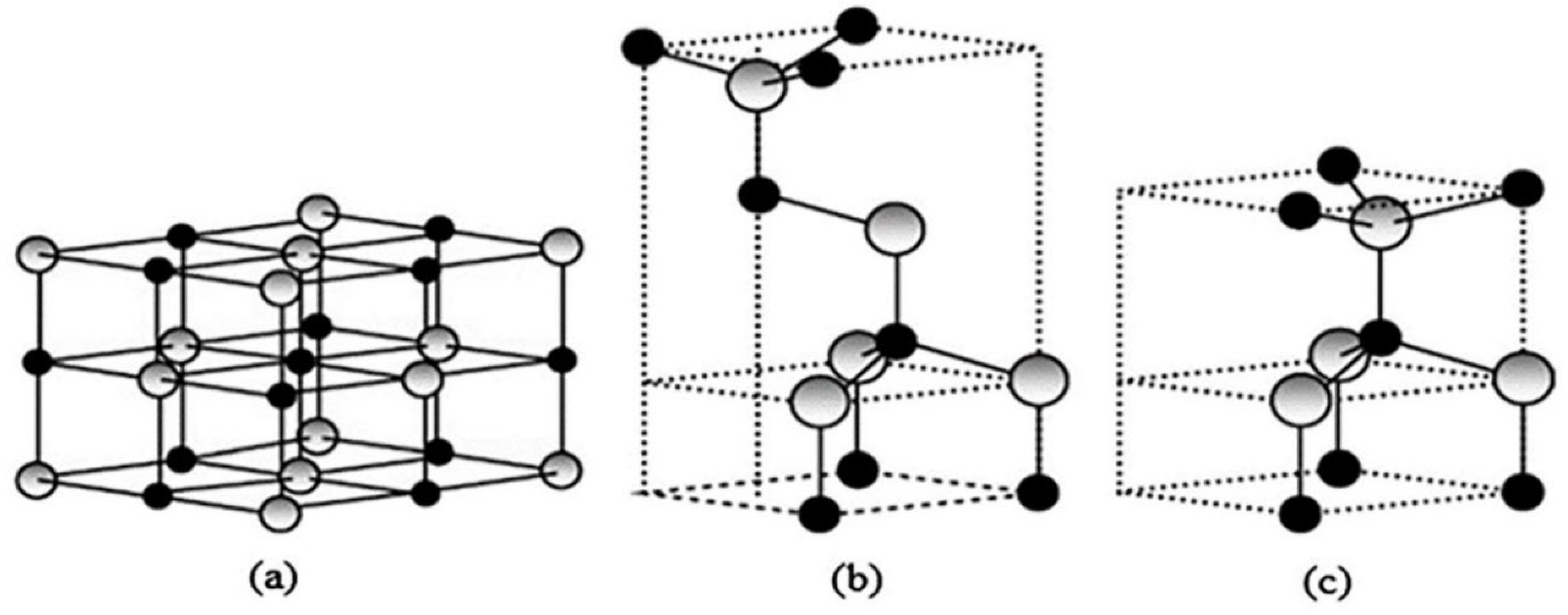

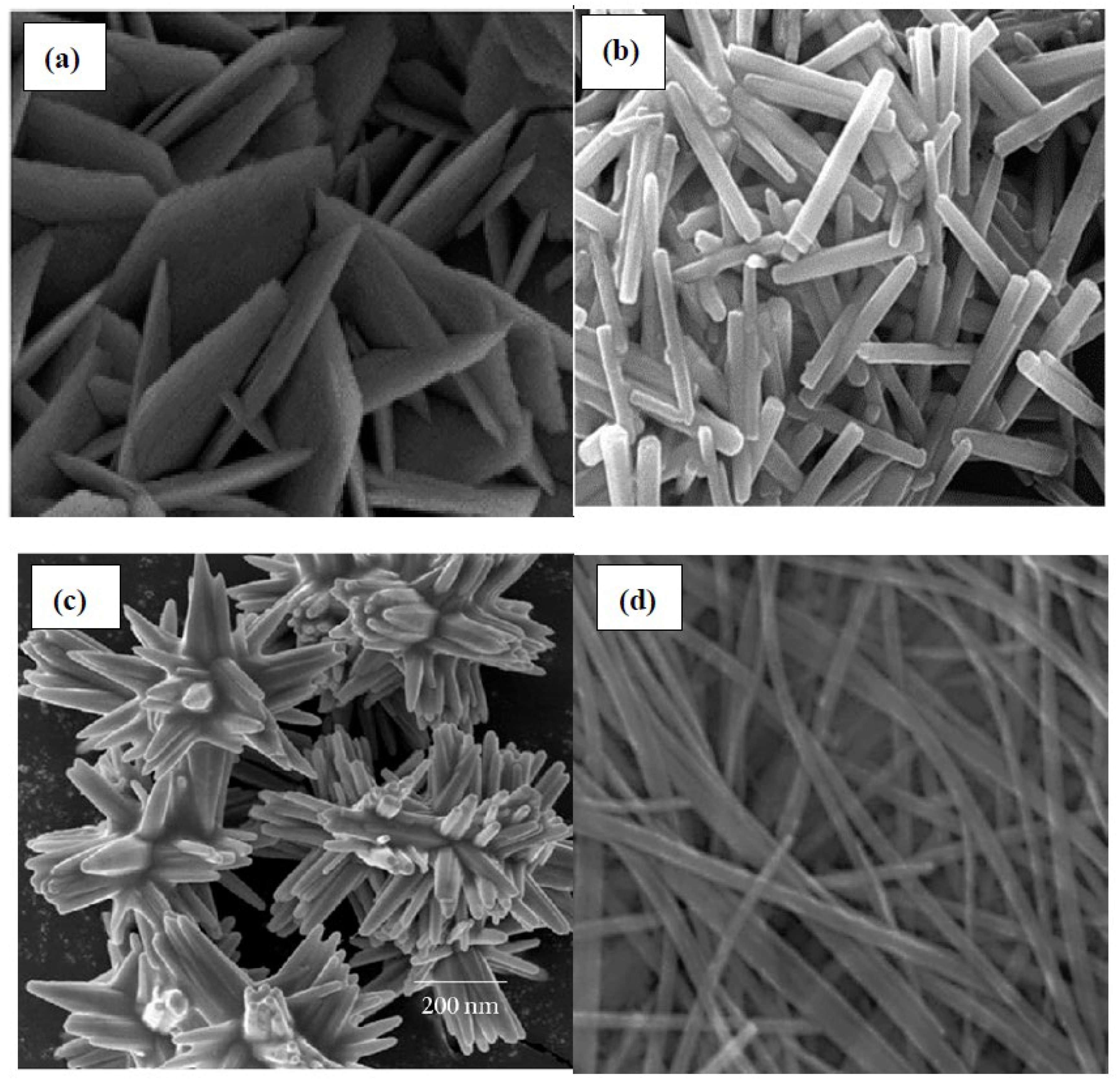

4.1. Characterization of ZnO Nanocatalyst

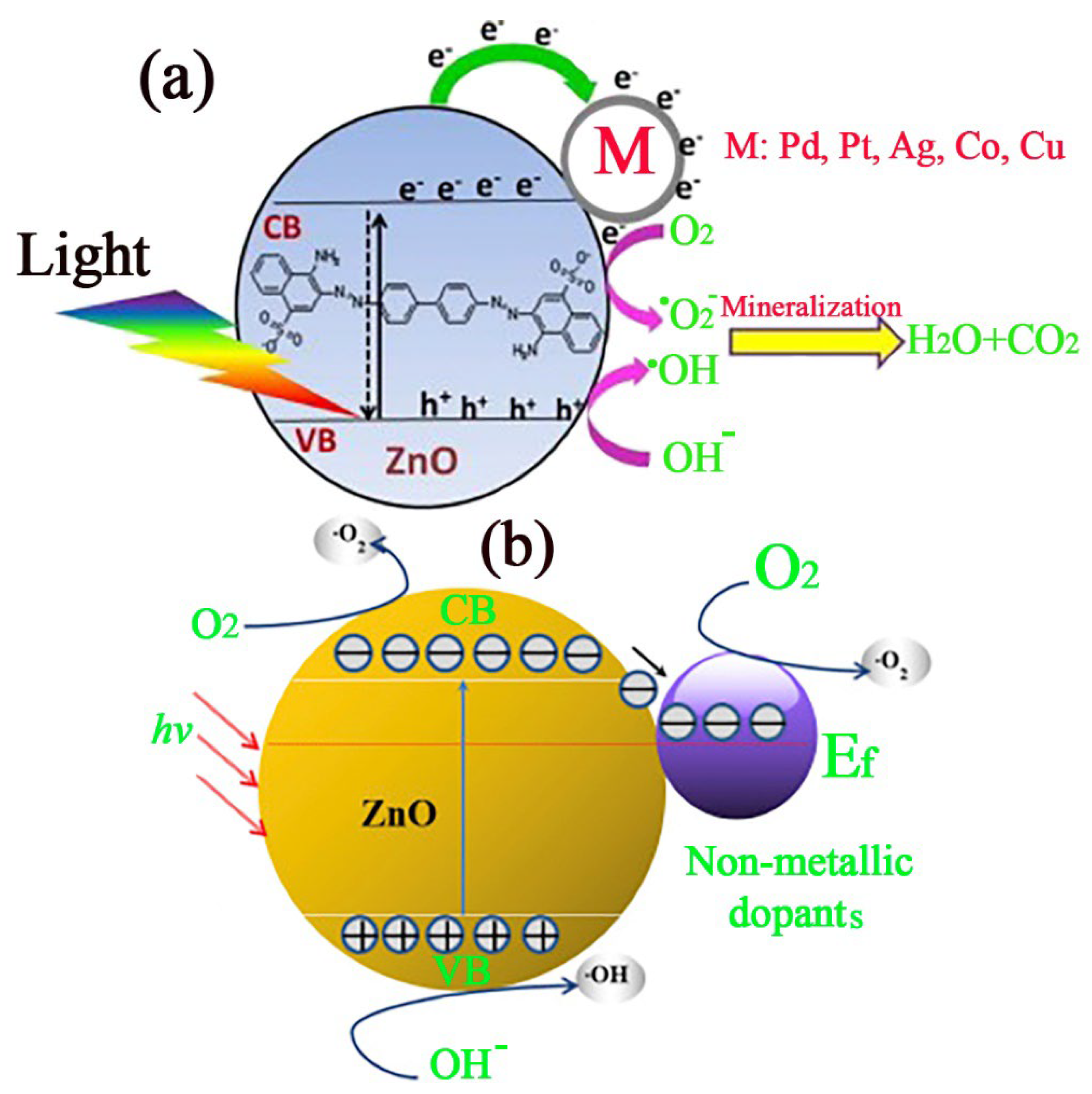

4.2. Photocatalysis Mechanism of ZnO

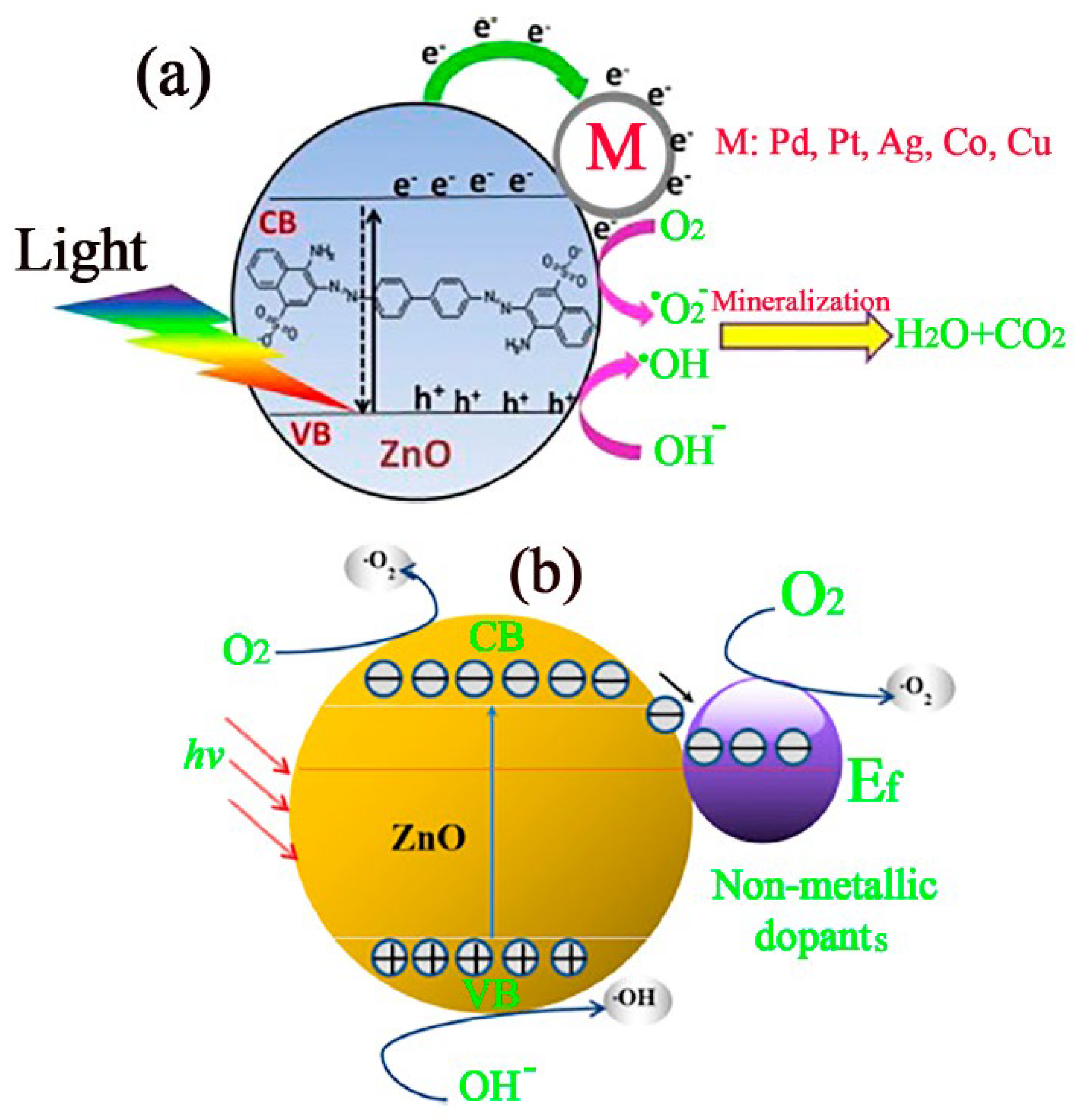

4.3. Improving the Photodegradation Efficiency of ZnO

5. Factors Affecting Photodegradation Efficiency

5.1. Photocatalyst Dosage

5.2. Photocatalyst Structure

5.3. Contaminant Concentration on Photodegradation Efficiency

5.5. Light Intensity and Wavelength

5.6. Temperature

5.7. Reaction Time

6. Recyclability of ZnO and TiO2 Photocatalysts

7. Literature Review

8. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tamjidi, S.; Moghadas, B.K.; Esmaeili, H.; Khoo, F.S.; Gholami, G.; Ghasemi, M. Improving the surface properties of adsorbents by surfactants and their role in the removal of toxic metals from wastewater: A review study. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 148, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Dynamic Relationship of Urban and Rural Water Shortage Risks Based on the Economy–Society–Environment Perspective. Agriculture 2022, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Selmi, A.; Esmaeili, H. A review study on new aspects of biodemulsifiers: Production, features and their application in wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaleghi, H.; Esmaeili, H.; Jaafarzadeh, N. B. Ramavandi, Date seed activated carbon decorated with CaO and Fe3O4 nanoparticles as a reusable sorbent for removal of formaldehyde. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 39, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, H.; Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Mowla, D. Effect of surfactant on stability and size distribution of gas condensate droplets in water. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2014, 59, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhad, R.C.; Gupta, R. Biological remediation of petroleum contaminants. In Advances in applied bioremediation; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009; pp. 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Lürling, M.; Kang, L.; Mucci, M.; van Oosterhout, F.; Noyma, N.P.; Miranda, M.; Huszar, V.L.; Waajen, G.; Marinho, M.M. Coagulation and precipitation of cyanobacterial blooms. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 158, 106032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Othman, N.; Asharuddin, S. Applications of natural coagulants to treat wastewater− a review. MATEC Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences 2017, 103, 06016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, T. Study of Water Treatment Using Photocatalytic Material. Doctoral dissertation, Gunma University, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karale, R.S.; Wadkar, D.V.; Wagh, M.P. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and ferrous ion on the degradation of 2-Aminopyridine. J. Appl. Water Eng. Res. 2023, 11, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Esmaeili, H. Application of nanomaterials for demulsification of oily wastewater: A review study. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 22, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerda-Correa, E.M.; Alexandre-Franco, M.F.; Fernández-González, C. Advanced oxidation processes for the removal of antibiotics from water. An overview. Water 2020, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, J.; Kamran, U.; Park, M.; Pant, B.; Park, S.J. Nitrogen and Sulfur Co-Doped Graphene Quantum Dots Anchored TiO2 Nanocomposites for Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. Catalysts 2022, 12, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Hu, J.; Esmaeili, H.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Y. A review study on wastewater decontamination using nanotechnology: Performance, mechanism and environmental impacts. Powder Technol. 2022, 412, 118023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirsath, S.R.; Pinjari, D.V.; Gogate, P.R.; Sonawane, S.H.; Pandit, A.B. Ultrasound assisted synthesis of doped TiO2 nano-particles: characterization and comparison of effectiveness for photocatalytic oxidation of dyestuff effluent. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013, 20, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, H. A critical review on the economic aspects and life cycle assessment of biodiesel production using heterogeneous nanocatalysts. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 230, 107224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yao, Z.; Wang, X. Characterization techniques for graphene-based materials in catalysis. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2017, 4, 755–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ware, P.; Shimpi, N. Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using peels of Passiflora foetida and study of its activity as an efficient catalyst for the degradation of hazardous organic dye. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.E.; Tasat, D.R.; Ramos, E.; Paparella, M.L.; Evelson, P.; Rebagliati, R.J.; Cabrini, R.L.; Guglielmotti, M.B.; Olmedo, D.G. Impact through time of different sized titanium dioxide particles on biochemical and histopathological parameters. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2014, 102, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Cai, D.; Yang, K.; Yu, J.C.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, C. Sol–gel derived S,I-codoped mesoporous TiO2 photocatalyst with high visible-Light photocatalytic activity. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2010, 71, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghian, F.; Najafi, A. CuO/WO3/TiO2 photocatalyst for degradation of phenol wastewater. Sci. Iran. 2018, 25, 3345–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razip, N.I.M.; Lee, K.M.; Lai, C.W.; Ong, B.H. Recoverability of Fe3O4/TiO2 nanocatalyst in methyl orange degradation. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 075517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayegan, Z.; Haghighat, F.; Lee, C.S. Carbon-doped TiO2 film to enhance visible and UV light photocatalytic degradation of indoor environment volatile organic compounds. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Liu, L.; Pang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wei, M.; Wu, Y.; Dong, G.; Zhang, J.; Shan, D.; Wang, B. N,P-codoped carbon quantum dots-decorated TiO2 nanowires as nanosized heterojunction photocatalyst with improved photocatalytic performance for methyl blue degradation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 9932–9943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tju, H.; Taufik, A.; Saleh, R. Enhanced UV photocatalytic performance of magnetic Fe3O4/CuO/ZnO/NGP nanocomposites. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 710, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, S.; Thangavel, S.; Raghavan, N.; Krishnamoorthy, K.; Venugopal, G. Visible-light driven photocatalytic degradation of methylene-violet by rGO/Fe3O4/ZnO ternary nanohybrid structures. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 665, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaee, M.; Olya, M.E.; Drean, J.Y.; Hekmati, A.H. Synthesize, characterization and application of ZnO/W/Ag as a new nanophotocatalyst for dye removal of textile wastewater; kinetic and economic studies. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 80, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, P.; Puttaiah, S.H.; Wantala, K.; Shahmoradi, B. Preparation of modified ZnO nanoparticles for photocatalytic degradation of chlorobenzene. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baaloudj, O.; Nasrallah, N.; Assadi, A.A. Facile synthesis, structural and optical characterizations of Bi12ZnO20 sillenite crystals: Application for Cefuroxime removal from wastewater. Mater. Lett. 2021, 304, 130658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Li, H.; Su, M.; Liang, S.X. Occurrence and removal of organic pollutants by a combined analysis using GC-MS with spectral analysis and acute toxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 207, 111237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Khan, S.A.; Sharma, K.; Jadhao, P.R.; Pant, K.K.; Ziora, Z.M.; Blaskovich, M.A. Current perspective of innovative strategies for bioremediation of organic pollutants from wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre Hernandez, E.A. Management of Produced Water from the Oil and Gas Industry: Characterization, Treatment, Disposal and Beneficial Reuse. Doctoral dissertation, Politecnico di Torino, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- David, E.; Niculescu, V.C. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) as Environmental Pollutants: Occurrence and Mitigation Using Nanomaterials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2021, 18, 13147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez Castillo, F.Y.; Avelar González, F.J.; Garneau, P.; Marquez Diaz, F.; Guerrero Barrera, A.L.; Harel, J. Presence of multi-drug resistant pathogenic Escherichia coli in the San Pedro River located in the State of Aguascalientes, Mexico. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Franco, J.H.; Galeano, L.-A.; Vicente, M.-A. Fly ash as photo-Fenton catalyst for the degradation of amoxicillin. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavasol, F.; Tabatabaie, T.; Ramavandi, B.; Amiri, F. Design a new photocatalyst of sea sediment/titanate to remove cephalexin antibiotic from aqueous media in the presence of sonication/ultraviolet/hydrogen peroxide: Pathway and mechanism for degradation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 65, 105062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, M.; Esmaeili, H. Ultrasonic-assisted synthesis of zeolite/activated carbon@ MnO2 composite as a novel adsorbent for treatment of wastewater containing methylene blue and brilliant blue. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, I.A.W.; Ahmad, A.L.; Hameed, B.H. Enhancement of basic dye adsorption uptake from aqueous solutions using chemically modified oil palm shell activated carbon. Colloids Surf. A. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2008, 318, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Cui, J.; Yu, S.; Jiang, H.; Zhong, C.; Hongshun, J. Preparation of aminated chitosan microspheres by one-pot method and their adsorption properties for dye wastewater. Royal Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 182226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, K.C.; Suhaimi, H.; Sambudi, N.S. Electrospun-based TiO2 nanofibers for organic pollutant photodegradation: a comprehensive review. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2022, 38, 641–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskar, N.; Kumar, U. Adsorption of crystal violet from wastewater by modified bambusa tulda. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 2755–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyonyi, W.C.; Onyari, J.M.; Shiundu, P.M. Adsorption of Congo red dye from aqueous solutions using roots of Eichhornia crassipes: kinetic and equilibrium studies. Energy Procedia 2014, 50, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diantoro, M.; Kusumaatmaja, A.; Triyana, K. Study on photocatalytic properties of TiO2 nanoparticle in various pH condition. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1011, 012069. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiari, R.; Kamkari, B.; Afrand, M.; Abdollahi, A. Preparation of stable TiO2-Graphene/Water hybrid nanofluids and development of a new correlation for thermal conductivity. Powder Technol. 2021, 385, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, S. Photocatalytic activity assessment of micro-sized TiO2 used as powders and as starting material for porcelain gres tiles production. 2014.

- Sarafraz, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Yazdanbakhsh, A.; Amini, M.M.; Sadani, M.; Eslami, A. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin by black Ti3+/N-TiO2 under visible LED light irradiation: Kinetic, energy consumption, degradation pathway, and toxicity assessment. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 137, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamuddin, I.; Asiri, A.M.; Lichtfouse, E. Nanophotocatalysis and environmental applications. Detoxification and Disinfection. Springer. 2020, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.H.; Chen, W.H. Graphene Family Nanomaterials (GFN)-TiO2 for the Photocatalytic Removal of Water and Air Pollutants: Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neppolian, B.; Wang, Q.; Jung, H.; Choi, H. Ultrasonic-assisted sol-gel method of preparation of TiO2 nano-particles: characterization, properties and 4-chlorophenol removal application. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008, 15, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MODAN, E.M.; PLĂIAȘU, A.G. Advantages and disadvantages of chemical methods in the elaboration of nanomaterials. The Annals of “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati. Fascicle IX, Metallurgy and Materials Science 2020, 43, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamukamba, P.; Okoh, O.; Mungondori, H.; Taziwa, R.; Zinya, S. Synthetic methods for titanium dioxide nanoparticles: a review. Titanium dioxide-material for a sustainable environment 2018, 151–1755. [Google Scholar]

- Madjene, F.; Aoudjit, L.; Igoud, S.; Lebik, H.; Boutra, B. A review: titanium dioxide photocatalysis for water treatment. Transnational Journal of Science and Technology 2013, 3, 1857–8047. [Google Scholar]

- Otieno, S.; Lanterna, A.E.; Mack, J.; Derese, S.; Amuhaya, E.K.; Nyokong, T.; Scaiano, J.C. Solar Driven Photocatalytic Activity of Porphyrin Sensitized TiO2: Experimental and Computational Studies. Molecules 2021, 26, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.V. Structural and Morphological modification of TiO2 doped metal ions and investigation of photo-induced charge transfer processes. Doctoral dissertation, Université du Maine; Instituto politécnico nacional, México, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stamate, M.; Lazar, G. Application of titanium dioxide photocatalysis to create self-cleaning materials. Romanian Technical Sciences Academy MOCM 2007, 13, 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, A.; Gągol, M.; Makoś, P.; Khan, J.A.; Boczkaj, G. Integrated photocatalytic advanced oxidation system (TiO2/UV/O3/H2O2) for degradation of volatile organic compounds. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 224, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, W.Y.; Urakawa, A.; Ng, Y.H.; Sit, P. Heterogeneous Catalysts: Advanced Design, Characterization, and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.; Yoon, M. Facile synthesis of pure TiO2 (B) nanofibers doped with gold nanoparticles and solar photocatalytic activities. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2012, 111, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Tran, Q.B.; Nguyen, X.C.; Ho, T.T.T.; Shokouhimehr, M.; Vo, D.V.N.; Lam, S.S.; Nguyen, H.P.; Hoang, C.T.; Ly, Q.V.; Peng, W. Submerged photocatalytic membrane reactor with suspended and immobilized N-doped TiO2 under visible irradiation for diclofenac removal from wastewater. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 142, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, N.; Hayashi, T. Preparation of TiO2 nanoparticles surface-modified by both carboxylic acid and amine: Dispersibility and stabilization in organic solvents. Colloids Surf. A. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2008, 317, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuraje, N.; Asmatulu, R.; Mul, G. Green photo-active nanomaterials: sustainable energy and environmental remediation. Royal Society of Chemistry 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.N.I.; Julkapli, N.M.; Bagheri, S.; Yousefi, A.T. TiO2 hybrid photocatalytic systems: impact of adsorption and photocatalytic performance. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 35, 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul, A.R.; Manjulavalli, T.E.; Venckatesh, R. Visible light proven Si doped TiO2 nanocatalyst for the photodegradation of Organic dye. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 1760–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczarek, M.; Kowalska, E. On the origin of enhanced photocatalytic activity of copper-modified titania in the oxidative reaction systems. Catalysts 2017, 7, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, M.S.; Nayak, V.; Reddy, K.R.; Naveen, S.; Raghu, A.V. Non-metal (Oxygen, Sulphur, Nitrogen, Boron and Phosphorus)-Doped Metal Oxide Hybrid Nanostructures as Highly Efficient Photocatalysts for Water Treatment and Hydrogen Generation. Nanophotocatalysis and Environmental Applications: Materials and Technology 2019, 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rengaraj, S.; Li, X.Z. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of TiO2 by doping with Ag for degradation of 2, 4, 6-trichlorophenol in aqueous suspension. J. Mol. Catal. A. Chem. 2006, 243, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, T.J.; Huang, H.Y.; Hsieh, M.T.; Chen, J.J. Laser-induced silver nanoparticles on titanium oxide for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 4707–4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.; Yang, C.; Liao, L. Photoelectrocatalytic degradation of high COD dipterex pesticide by using TiO2/Ni photo electrode. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 24, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaoulani, S.; Chaker, H.; Cadet, C.; Bychkov, E.; Cherif, L.; Bengueddach, A.; Fourmentin, S. Wastewater treatment by cyclodextrin polymers and noble metal/mesoporous TiO2 photocatalysts. C. R. Chim. 2015, 18, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Tang, T.; Wei, Y.; Dang, D.; Huang, K.; Chen, X.; Yin, H.; Tao, X.; Lin, Z.; Dang, Z.; Lu, G. Photocatalytic debromination of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) on metal doped TiO2 nanocomposites: Mechanisms and pathways. Environ. Int. 2019, 127, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V.; Verma, P.; Sharma, H.; Tripathy, S.; Saini, V.K. Photodegradation of 4-nitrophenol over B-doped TiO2 nanostructure: effect of dopant concentration, kinetics, and mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 10966–10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sescu, A.M.; Favier, L.; Lutic, D.; Soto-Donoso, N.; Ciobanu, G.; Harja, M. TiO2 doped with noble metals as an efficient solution for the photodegradation of hazardous organic water pollutants at ambient conditions. Water 2020, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekha, K.; Nirmala, M.; Nair, M.G.; Anukaliani, A. Structural, optical, photocatalytic and antibacterial activity of zinc oxide and manganese doped zinc oxide nanoparticles. Phys. B. Condens. Matter. 2010, 405, 3180–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitia, P.J.P.; Soares, N.D.F.F.; Coimbra, J.S.D.R.; de Andrade, N.J.; Cruz, R.S.; Medeiros, E.A.A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, antimicrobial activity and food packaging applications. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2012, 5, 1447–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruganandam, G.; Mala, N.; Pandiarajan, S.; Srinivasan, N.; Ramya, R.; Sindhuja, E.; Ravichandran, K. Synergistic effects of Mg and F doping on the photocatalytic efficiency of ZnO nanoparticles towards MB and MG dye degradation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. 2017, 28, 18228–18235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, V.A.; Jagadish, C. Basic properties and applications of ZnO. In Zinc oxide bulk, thin films and nanostructures; Elsevier Science Ltd, 2006; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shaba, E.Y.; Jacob, J.O.; Tijani, J.O.; Suleiman, M.A.T. A critical review of synthesis parameters affecting the properties of zinc oxide nanoparticle and its application in wastewater treatment. Appl. Water Sci. 2021, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saedy, S.; Haghighi, M.; Amirkhosrow, M. Hydrothermal synthesis and physicochemical characterization of CuO/ZnO/Al2O3 nanopowder. Part I: Effect of crystallization time. Particuology 2012, 10, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Yang, C.S.; Huang, H.J.; Hu, S.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Cheng, C.F.; Huang, C.C.; Tsai, M.K.; Kuang, H.C. Structural and optical properties of ZnO nanopowder prepared by microwave-assisted synthesis. J. Lumin 2010, 130, 1756–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasang, T.; Namratha, K.; Parvin, T.; Ranganathaiah, C.; Byrappa, K. Tuning of band gap in TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles by selective doping for photocatalytic applications. Mater. Res. Innov. 2015, 19, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, E.; Esrafili, A.; Jafari, A.J.; Kalantary, R.R.; Nourmoradi, H.; Farzadkia, M. The comparison of ZnO/polyaniline nanocomposite under UV and visible radiations for decomposition of metronidazole: degradation rate, mechanism and mineralization. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 128, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Dang, F.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y. Solvothermal Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange and p-Nitrophenol. Water 2021, 13, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berjilia, M.M.; Manikandan, S.; Dhanalakshm, K.B. PHOTOCATALYTIC DEGRADATION OF RESORCINOL OVER ZnO POWDER THE INFLUENCE OF PEROXOMONOSULPHATE AND PEROXODISULPHATE ON THE REACTION RATE. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 1316–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofrano, G.; Libralato, G.; Brown, J. Nanotechnologies for environmental remediation. Springer International Publishing. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.H.; Hong, K.; Kwon, S.H.; Lim, D.C. Development of Inverted Organic Photovoltaics with Anion doped ZnO as an Electron Transporting Layer. Journal of the Korean Institute of Surface Engineering 2016, 49, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, J.; Hoang, Q.V.; Han, J.W. A. Prasetio, M. Jahandar, Y.H. Kim, S. Cho, D.C. Lim, The role of cation and anion dopant incorporated into a ZnO electron transporting layer for polymer bulk heterojunction solar cells. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 37714–37723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güy, N.; Çakar, S.; Özacar, M. Comparison of palladium/zinc oxide photocatalysts prepared by different palladium doping methods for congo red degradation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 466, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzhalosai, V.; Subash, B.; Senthilraja, A.; Dhatshanamurthi, P.; Shanthi, M. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic properties of SnO2–ZnO composite under UV-A light, Spectrochim. Acta A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 115, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeel, M.; Saeed, M.; Khan, I.; Muneer, M.; Akram, N. Synthesis and characterization of Co–ZnO and evaluation of its photocatalytic activity for photodegradation of methyl orange. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 1426–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallejo, W.; Cantillo, A.; Díaz-Uribe, C. Methylene blue photodegradation under visible irradiation on Ag-doped ZnO thin films. Int. J. Photoenergy 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, W.; Cantillo, A.; Salazar, B.; Diaz-Uribe, C.; Ramos, W.; Romero, E.; Hurtado, M. Comparative study of ZnO thin films doped with transition metals (Cu and Co) for methylene blue photodegradation under visible irradiation. Catalysts 2020, 10, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkallas, F.H.; Ben Gouider Trabelsi, A.; Nasser, R.; Fernandez, S.; Song, J.M.; Elhouichet, H. Promising Cr-Doped ZnO Nanorods for Photocatalytic Degradation Facing Pollution. Appl. Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragupathy, S.; Priyadharsan, A.; AlSalhi, M.S.; Devanesan, S.; Guganathan, L.; Santhamoorthy, M.; Kim, S.C. Effect of doping and loading Parameters on photocatalytic degradation of brilliant green using Sn doped ZnO loaded CSAC. Environ. Res. 2022, 210, 112833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzewei, T.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Abidin, C.Z.A.; Ridwan, F.M. The effect of iron doping on ZnO catalyst on dye removal efficiency. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 476, 012108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.Z.; Li, A.D.; Li, X.Y.; Zhai, H.F.; Zhang, W.Q.; Gong, Y.P.; Li, H.; Wu, D. Photo-degradation of methylene blue using Ta-doped ZnO nanoparticle. J. Solid State Chem. 2010, 183, 1359–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, E.; Pillay, K. Synthesis of N-doped ZnO nanoparticles with cabbage morphology as a catalyst for the efficient photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue under UV and visible light. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 7509–7535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.C.; Huang, Q. Solvothermal synthesis of N-doped ZnO microcrystals from commercial ZnO powder with visible light-driven photocatalytic activity. Mater. Lett. 2014, 119, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi-hao, T.; Hang, Z.; Yin, W.; Ming-hui, D.; Guo, J.; Bin, Z. Facile fabrication of nitrogen-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Micro. Nano. Lett. 2015, 10, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. ZnO/graphene-oxide nanocomposite with remarkably enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 377, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.; Han, G.; Chang, Y.; Dong, J. The synthesis and properties of ZnO–graphene nano hybrid for photodegradation of organic pollutant in water. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechambi, O.; Sayadi, S.; Najjar, W. Photocatalytic degradation of bisphenol A in the presence of C-doped ZnO: effect of operational parameters and photodegradation mechanism. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 32, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, J.; Meng, H. Green synthesis and photo-catalytic performances for ZnO-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 411, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Park, M.; Kim, H.-Y.; El-Newehy, M.; Rhee, K.Y.; Park, S.-J. Effect of TiO2 on photocatalytic activity of polyvinylpyrrolidone fabricated via electrospinning. Compos. B. Eng. 2015, 80, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notodarmojo, S.; Sugiyana, D.; Handajani, M.; Kardena, E.; Larasati, A. Synthesis of TiO2 nanofiber-nanoparticle composite catalyst and its photocatalytic decolorization performance of reactive black 5 dye from aqueous solution. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2017, 49, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiful Amran, S.N.B.; Wongso, V.; Abdul Halim, N.S.; Husni, M.K.; Sambudi, N.S.; Wirzal, M.D.H. Immobilized carbondoped TiO2 in polyamide fibers for the degradation of methylene blue. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2019, 7, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemoğlu, S.; Aksu, S.K.; Sayılkan, F.; Izgi, B.; Asiltürk, M.; Sayılkan, H.; Frimmel, F.; Güçer, Ş. Photocatalytic degradation of Congo Red by hydrothermally synthesized nanocrystalline TiO2 and identification of degradation products by LC–MS. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 155, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Yu, J.; Jaroniec, M. Enhanced photocatalytic H 2-production activity of graphene-modified titania nanosheets. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 3670–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wu, R.; Liu, H.; Yang, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, C. Synthesis of metal-phase-assisted 1T@ 2H-MoS2 nanosheet-coated black TiO2 spheres with visible light photocatalytic activities. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 10302–10312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Wang, Y.; Mai, C.; Pan, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J. Facile in situ growth of ZnO nanosheets standing on Ni foam as binder-free anodes for lithium ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 19253–19260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Ji, Y.L.; Xu, H.; Simon, P.; Wu, Z. Regularly shaped, single-crystalline ZnO nanorods with wurtzite structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 14864–14865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Xie, B.; Jin, L.; Chen, W.; Li, J. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Responsive Characteristics of Hierarchical Zinc Oxide Nanoflowers to Sulfur Dioxide. J. Nanotechnol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Q.; An, M. A facile and flexible approach for large-scale fabrication of ZnO nanowire film and its photocatalytic applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, R.R.; Kumar Vishwakarma, P.; Yadav, U.; Rai, S.; Umrao, S.; Giri, R.; Saxena, P.S.; Srivastava, A. 2D SnS2 Nanostructure-Derived Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants Under Visible Light. Front. Nanotechnol. 2021, 3, 711368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeb, A.M.; Hussein, D.S. Synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles and their photocatalytic activity for methylene blue. American Journal of Nanomaterials 2015, 3, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik, A.; Alalm, M.G.; Awad, H.M.; Islam, M.; Qyyum, M.A.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.A.H.; Osman, A.I.; Lee, M. Solar photo-oxidation of recalcitrant industrial wastewater: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 1839–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, K.M.; Parija, S. Photocatalytic degradation of phenol under solar radiation using microwave irradiated zinc oxide. Sol. Energy 2006, 80, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhabiles, O.; Mahmoudi, H.; Lounici, H.; Goosen, M.F. Effectiveness of a photocatalytic organic membrane for solar degradation of methylene blue pollutant. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 14067–14076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelar, S.G.; Mahajan, V.K.; Patil, S.P.; Sonawane, G.H. Effect of doping parameters on photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue using Ag doped ZnO nanocatalyst. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenzadeh, M.; Mirbagheri, S.A.; Sabbaghi, S. Degradation of 1,2-dichloroethane by photocatalysis using immobilized PAni-TiO2 nano-photocatalyst. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 31328–31343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, B.H.; Salman, J.M.; Ahmad, A.L. Adsorption isotherm and kinetic modeling of 2,4-D pesticide on activated carbon derived from date stones. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 163, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Alvarez, B.; Torres-Palma, R.A.; Penuela, G. Solar photocatalitycal treatment of carbofuran at lab and pilot scale: effect of classical parameters, evaluation of the toxicity and analysis of organic by-products. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 191, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saien, J.; Khezrianjoo, S. Degradation of the fungicide carbendazim in aqueous solutions with UV/TiO2 process: optimization, kinetics and toxicity studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 157, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmolla, E.S.; Chaudhuri, M. Degradation of amoxicillin, ampicillin and cloxacillin antibiotics in aqueous solution by the UV/ZnO photocatalytic process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 173, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, H.E. Evaluation of the performance of photocatalytic systems for the treatment of indoor air in medical environments. Doctoral dissertation, Ecole nationale supérieure Mines-Télécom Atlantique 2018.

- Lee, K.M.; Lai, C.W.; Ngai, K.S.; Juan, J.C. Recent developments of zinc oxide based photocatalyst in water treatment technology: a review. Water Res. 2016, 88, 428–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elaziouti, A.; Ahmed, B. ZnO-assisted photocatalytic degradation of congo Red and benzopurpurine 4B in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Eng. Process. Technol. 2011, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-López, V.M.; Koutchma, T.; Linden, K. Ultraviolet and pulsed light processing of fluid foods, In Novel thermal and non-thermal technologies for fluid foods. Academic Press. 2012, 185–223. [Google Scholar]

- Bayarri, B.; Abellán, M.N.; Giménez, J.; Esplugas, S. Study of the wavelength effect in the photolysis and heterogeneous photocatalysis. Catal. Today 2007, 129, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A. Removal of formaldehyde from industrial waste water. M.Sc. thesis in Chemical Engineering, CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, Sweden 2020.

- Chen, Y.W.; Hsu, Y.H. Effects of reaction temperature on the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 with Pd and Cu cocatalysts. Catalysts 2021, 11, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Liu, B.; Song, M.; Zhao, X. Temperature effect on the photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange under UV-vis light irradiation. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2010, 25, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, N.A.; Kanjwal, M.A.; Chronakis, I.S.; Kim, H.Y. Influence of temperature on the photodegradation process using Ag-doped TiO2 nanostructures: negative impact with the nanofibers. J. Mol. Catal. A. Chem. 2013, 366, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Xiang, C.; Li, L. TiO2-Doped chitosan microspheres supported on cellulose acetate fibers for adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange. Polymers 2019, 11, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M.; Samy, S.; Shaban, M.; Altowyan, A.S.; Hamdy, H.; Ahmed, A.M. Fabrication of TiO2/NiO pn nanocomposite for enhancement dye photodegradation under solar radiation. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoofar, K.; Haghighi, M.; Lashanizadegan, M.; Ahmadvand, Z. ZnO nanorods: efficient and reusable catalysts for the synthesis of substituted imidazoles in water. J. Taibah. Univ. Sci. 2015, 9, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jin, H.; Wu, D.; Nie, Y.; Tian, X.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Y. Fe3O4@ S-doped ZnO: A magnetic, recoverable, and reusable Fenton-like catalyst for efficient degradation of ofloxacin under alkaline conditions. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Aslam, S.; Haider, A.; Naz, S.; Ul-Hamid, A.; Shahzadi, A.; Ikram, M.; Haider, J.; Ahmad, S.O.A.; Butt, A.R. Doping of Mg on ZnO nanorods demonstrated improved photocatalytic degradation and antimicrobial potential with molecular docking analysis. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padikkaparambil, S.; Narayanan, B.; Yaakob, Z.; Viswanathan, S.; Tasirin, S.M. Au/TiO2 reusable photocatalysts for dye degradation. Int. J. Photoenergy 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z. The preparation of self-floating Sm/N co-doped TiO2/diatomite hybrid pellet with enhanced visible-light-responsive photoactivity and reusability. Adv. Powder Technol. 2019, 30, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Jing, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Xiong, J. High reusability and durability of carbon-doped TiO2/carbon nanofibrous film as visible-light-driven photocatalyst. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 3795–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrudin, N.N.; Nawi, M.A.; Nawawi, W.I. Enhanced photocatalytic decolorization of methyl orange dye and its mineralization pathway by immobilized TiO2/polyaniline. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2019, 45, 2771–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, S.; Li, R.Y.M.; Lai, C.W.; Yusof, Y.; Gan, S.; Akbarzadeh, O.; Chowhury, Z.Z.; Yue, X.G.; Johan, M.R. Methylene blue dye photocatalytic degradation over synthesised Fe3O4/AC/TiO2 nano-catalyst: degradation and reusability studies. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J. An efficient, stable and reusable polymer/TiO2 photocatalytic membrane for aqueous pollution treatment. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 11335–11351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh-Faal, A.; Bordbar, M.; Negahdar, N.; Nasrollahzadeh, M. Green synthesis of the Ag/ZnO nanocomposite using Valeriana officinalis L. root extract: application as a reusable catalyst for the reduction of organic dyes in a very short time. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 11, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, G.A.; Bastami, T.R.; Ahmadpour, A.; Eshaghi, Z. Environmental application of nanotechnology. Annu. Rev. Nano. Res. 2008, 2, 439–493. [Google Scholar]

- Baaloudj, O.; Nasrallah, N.; Bouallouche, R.; Kenfoud, H.; Khezami, L.; Assadi, A.A. High efficient Cefixime removal from water by the sillenite Bi12TiO20: Photocatalytic mechanism and degradation pathway. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Wang, X.; Feng, Y.; Li, J.; Lim, C.T.; Ramakrishna, S. Coaxial electrospinning of (fluorescein isothiocyanate-Conjugated bovine serum albumin)-Encapsulated poly ("-caprolactone) nanofibers for sustained release. Biomacromolecule 2006, 7, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, C.S.; Wang, M.K.; Ko, C.H.; Ou, C.C.; Wu, C.H. Removal of benzene and toluene by carbonized bamboo materials modified with TiO2. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Cai, Y.; Song, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Q. Electrospun TiO2 nanofibers coated with polydopamine for enhanced sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic dyes. Surf. Interface Anal. 2019, 51, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baaloudj, O.; Assadi, A.A.; Azizi, M.; Kenfoud, H.; Trari, M.; Amrane, A.; Assadi, A.A.; Nasrallah, N. Synthesis and characterization of ZnBi2O4 nanoparticles: photocatalytic performance for antibiotic removal under different light sources. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, M.; Fazeli, A.; Tavakoli, O. Photocatalytic degradation of phenol under visible light using electrospun Ag/TiO2 as a 2D nano-powder: Optimizing calcination temperature and promoter content. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.J.; Lin, C.C. Photocatalytic decolorization of methylene blue in aqueous solutions using coupled ZnO/SnO2 photocatalysts. Powder Technol. 2013, 246, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process | Advantages and disadvantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermal | Advantages: Good size distribution, crystal shape control, low defects, synthesizing large crystals with high quality, fine particle size Disadvantages: high equipment cost, high temperature and pressure needed, long synthesis time |

[50] |

| Sol-gel | Advantages: High purity products, good size distribution, remarkable specific surface area, economical, uniform size of particles, fine particle size, ease of synthesis Disadvantages: agglomeration of particles, long processing time, using organic solvents which may be toxic |

[50] |

| Flame pyrolysis | Advantages: Rapid and mass production Disadvantages: Requires high energy, ease of rutile formation |

[48] |

| Solvothermal | Advantages: High crystallinity, suitability for materials, low defects, better control of the features of TiO2 compared to hydrothermal process Disadvantages: requires organic solvents, unstable at high temperature |

[48,51] |

| Inverse micelle | Advantages: Fine particle sizes, high crystallinity, low defects Disadvantages: High cost, high crystallization temperature |

[48] |

| Sonochemical | Advantages: High-specific surface area, simple control of particles and morphology, efficient for mesoporous materials, improve reaction rate, short time, no additive Disadvantages: Low yield, inefficient energy |

[15,50] |

| Microwave heating | Advantages: Fast heating, short reaction time, high reaction rate and efficiency | [51] |

| Dopant | Light source/pollutant | Conditions | PE for TiO2 (%) | PE for Doped TiO2 (%) | Ref. |

| Ag | UV-A illumination/ 2,4,6-trichlorophenol | 0.5 wt.% Ag, 120 min | - | 95 | [66] |

| Ag | Halogen lamp/MB | 2 Wt.% Ag, 120 min | - | 82.3 | [67] |

| Ni | Ultraviolet/Dipterex | pH 6, dipterex concentration= 40 mg/L, 2 h | - | 83.5 | [68] |

| Ce | UV lamp, crystal violet | 0.8 mol Ce in TiO2, 0.2 g/L catalyst, 30 ppm dye concentration, pH 6.5, intensity of 2000 W/cm2 | 70 | 92 | [15] |

| Fe | UV lamp/ Crystal violet | 1.2 mol Fe in TiO2, 0.2 g/L catalyst, 30 ppm dye concentration, pH 6.5, intensity of 2000 W/cm2 | 70 | 80 | [15] |

| Au | UV lamp/Total Organic Carbon | 8.71 mg/L Total Organic Carbon, 15W UV lamp | - | 93 | [69] |

| Si | UV lamp/MB | 20 h for TiO2 and 2 h for Si-doped TiO2, 10 ppm MB | 68 | 86.7 | [63] |

| Pd | UV lamp/2,2',4,4'-tetrabromodiphenylether | 5% Pd, 300 WUV lamp | - | 100 | [70] |

| B | UV light/4-nitrophenol | 5% B in TiO2, 1 g/L catalyst dose, 1 mg/L 4-nitrophenol | 79 | 90 | [71] |

| Au/UI | UV irradiation/2,4 dinitrophenol | 20 mg/L contaminant concentration, 120 min, 1 g/L catalyst dose | 60 | 37 | [72] |

| Au/IWI | UV irradiation/2,4 dinitrophenol | 20 mg/L contaminant concentration, 120 min, 1 g/L catalyst dose | 60 | 50 | [72] |

| Pd/IWI | UV irradiation/2,4 dinitrophenol | 20 mg/L contaminant concentration, 120 min, 1 g/L catalyst dose | 60 | 67 | [72] |

| Pd/IWI | UV irradiation/ Rhodamine 6G | 20 mg/L contaminant concentration, 120 min, 1 g/L catalyst dose | 88 | 96 | [72] |

| Dopant | Light source/pollutant | Operating conditions | *PE (%) for ZnO | PE (%) for Doped ZnO | Ref. |

| Co | Visible light irradiation/MO | 10 wt.% Co, 130 min, 100 mg/L MO | 46 | 93 | [89] |

| Ag | Visible irradiation/MB | 5 wt.% Ag, 120 min | 2.7 | 45.1 | [90] |

| Co | Visible light irradiation/MB | 5 wt.% Co, 10 ppm dye concentration, 140 min | 2.7 | 62.6 | [91] |

| Cu | Visible light irradiation/MB | 5 wt.% Cu, 10 ppm dye concentration, 140 min | 2.7 | 42.5 | [91] |

| Cr | UV-vis light illumination/MO | 1 wt.% Cr, 100 min | - | 99.8 | [92] |

| Sn | Sunlight/Brilliant green | 120 min | 72.6 | 96.52 | [93] |

| Fe | Sunlight/MB | Time=3 h | 90 | 95 | [94] |

| Ta | Visible light irradiation/MB | 20 min, 1 g/L catalyst dosage, pH 8, 10 mg/L dye concentration | - | 97.5 | [95] |

| Dopant | Light source/pollutant | Conditions | PE (%) ZnO | PE (%) Doped ZnO | Ref. |

| N | UV light or Visible light irradiation/MB | - | - | 99.6 | [96] |

| N | Visible light irradiation/Rhodamine 6G | 60 min, 0.01 g N | 76.2 | 81.6 | [97] |

| N | Visible light irradiation/Rhodamine B | 10 mg/L dye concentration, Room temperature, 2 h | - | 97 | [98] |

| N | Visible light irradiation/MB | 10 mg/L dye concentration, Room temperature, 2 h | - | 99 | [98] |

| C | Visible light/MB | 60 min | 54.3 | 98.1 | [99] |

| C | Visible light/MB | 2.5% Catalyst, 200 oC | 26 | 80 | [100] |

| C | UV irradiation/ Bisphenol A | 24 h | - | 100 | [101] |

| C | Sunlight irradiation/ Rhodamine B | 2.5 h | 54.6 | 92.9 | [102] |

| Catalyst | Pollutant | PE* (%) | PE (%)after n cycles | Ref. |

| ZnO nanorodes | imidazole | 83% | n=4, 80% | [135] |

| Ag-doped ZnO nanocomposite | MB | 95% | n=4, 89.5% | [118] |

| Fe3O4@S-doped ZnO | ofloxacin | Above 90% | n=6, Above 90% | [136] |

| ZnO NPs | MB | 93.25% | n=5, 86.63% | [22] |

| ZnO NPs | Rhodamine B | 91.06% | n=5, 83.61% | [22] |

| Mg-doped ZnO nanorodes | MB and ciprofloxacin | 82% | n=4, 75% | [137] |

| 2%Au-doped TiO2 nanocatalyst | MO | 100% | n=11, 100% | [138] |

| Sm/N co-doped TiO2/diatomite | tetracycline | 87.1% | n=5, 83.2% | [139] |

| C-doped TiO2/carbon nanofibrous | rhodamine B | 94.2% | n=6, 92% | [140] |

| TiO2 | MO | 58.3% | n=10, 36.1% | [141] |

| TiO2/polyaniline | MO | 86% | n=10, 46.2% | [141] |

| Fe3O4/AC/TiO2 | MB | 98% | n=7, 93% | [142] |

| 2-(methacryloyloxy) ethyltrimethylammonium chloride/TiO2 | MB | 99.66% | n=20, 98.7% | [143] |

| TiO2/2NiO | MB | 100% | N=5, 72.6% | [134] |

| Nanocatalysts | Contaminants | Optimal conditions | DE (%) | References |

| TiO2 | Nitrobenzene | * CD=O.1M, CC=50 ppm | 100 | [145] |

| TiO2 | Parathion | CD=1 g/L, CC=50 ppm | 70 | [147] |

| TiO2 | Toluene | CD=5 g, CC=45 ppm | 71 | [145] |

| TiO2 | Phenol | 1.8 g/L catalyst dose | 100 | [145] |

| TiO2 | Benzene | CD=5 g, CC=45 ppm | 72 | [148] |

| TiO2 | MO | CD=3 g/L, CC=30 ppm | 100 | [145] |

| Fe3O4/TiO2 (P25) | MO | 1 h under UV light irradiation | 90.3 | [22] |

| Fe3O4/TiO2 (UV100) | MO | 1 h under UV light irradiation | 51.6 | [22] |

| CuO/WO3/TiO2 | 4-Chlorophen | CD= 0.75 g/L, H2O2 amount=563.16 mmol/L, 3 h | 94.8 | [21] |

| CuO/WO3/TiO2 | 3-Phenyl-1-propan | CD= 0.75 g/L, H2O2 amount=563.16 mmol/L, 3 h | 85.13 | [21] |

| Carbon-doped TiO2 | Methyl ethyl ketone | Under UV light | 94 | [23] |

| La/TiO2 | RamazolBrilliant Blue | - | 72 | [22] |

| PVP/TiO2/polydopamine | malachite green | 60 min, 10 mg/L of dye | 45 | [149] |

| PVP/TiO2/polydopamine | MB | 60 min, 10 mg/L of dye | 25 | [149] |

| PVP/TiO2/polydopamine | MO | 60 min, 10 mg/L of dye | 24 | [149] |

| ZnO | Amoxicillin | Ultraviolet, pH=11, Catalyst dose=0.5 g/L, time 180 min | 100 | [123] |

| ZnO | Ampicillin | Ultraviolet, pH=11, Catalyst dose=0.5 g/L, time 180 min | 100 | [123] |

| ZnO | Claxocillin | Ultraviolet, pH=11, Catalyst dose=0.5 g/L, time 180 min | 100 | [123] |

| rGO/Fe3O4/ZnO | MV | 120 min, CD= 0.04 g/L | 83.5 | [26] |

| Fe3O4/CuO/ZnO/graphene | MB | 120 min, CD= 0.3 g/L | 93 | [25] |

| Tungsten/silver/ZnO | Ponceau 4R | pH 5.64, CD= 0.08 g/L, 25oC | 78.8 | [27] |

| Bi12TiO20 | Cefixime | 3 h | 94.93 | [146] |

| Bi12ZnO20 | Cefuroxime | 4 h | 80 | [29] |

| ZnBi2O4 | Cefixime | Solar light (98 mW/cm2), 30 min | 89 | [150] |

| ZnBi2O4 | Cefixime | UV irradiation (20 mW/cm2), 2h | 88 | [150] |

| Ag/TiO2 | Phenol | pH 7, CD= 1.5 g/L, CC= 5 ppm, power light= 18 W | 82.65 | [151] |

| ZnO/SnO2 | MB | pH 12, CD= 0.5 g/L, time 60 min | 96 | [152] |

| Pure ZnO | Chlorobenzene | LED light | 71 | [28] |

| Pb/ZnO | Chlorobenzene | LED light | 100 | [28] |

| Ag/ZnO | Chlorobenzene | LED light | 95 | [28] |

| Cd/ZnO | Chlorobenzene | LED light | 90 | [28] |

| Pure ZnO | Chlorobenzene | Tungsten light | 90 | [28] |

| Pb/ZnO | Chlorobenzene | Tungsten light | 100 | [28] |

| Ag/ZnO | Chlorobenzene | Tungsten light | 83 | [28] |

| Cd/ZnO | Chlorobenzene | Tungsten light | 73 | [28] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).