1. Introduction

Sleep is an essential aspect of human life. worldwide, a significant number of people suffer from sleep disorders, with insomnia being the most commonly reported sleep disturbance [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Sleep disorder is characterized by difficulties in initiating or maintaining sleep, non-restorative sleep, or poor-quality sleep [

5,

6]. There has been much research into the effects of stress on sleep in rodents [

7]. The primary stressors used in previous studies were immobilization stress and mild electric shock, with few reports using other methods [

8,

9,

10]. These sleep disturbances are a prominent feature, and potentially even a hallmark, of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [

7].

Orexin is a neuropeptide whose main function is regulation of the sleep-wake cycle. Orexin regulates a wide variety of important bodily functions, such as eating behavior, stress response, reward processing, mood, and cognition [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Previous studies reported daytime sleepiness, narcolepsy, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep abnormalities, and in some cases an association between orexin deficiency narcolepsy [

11,

12,

13,

14].

The classes of drugs commonly used for the treatment of sleep disorder include γ-Aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA)-benzodiazepine (BZD) receptor agonists, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, melatonin receptor agonists, antidepressants, and antihistamines [

15,

16,

17]. GABA is an amino acid that occurs naturally in the human body, and it is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system of mammals. GABA plays a crucial role in maintaining mental health. It is involved in various physiological processes such as increasing brain protein synthesis, elevating growth hormone concentration, lowering high blood pressure, regulating diabetes, and facilitating diuresis. GABA has a calming effect and is potentially useful in treating insomnia and depression [

16,

17,

18].

GABALAGEN (GBL) is a type of collagen with a low molecular weight that contains GABA, which has the same structure as collagen molecules. Through a fermentation process involving specialized Lactobacillus strains (L.Brevis-BJ20 and plantarum-BJ21), GBL is converted into a peptide form that is easily absorbed by the body. This process also produces GABA, which is specialized for Lactobacillus strains. GBL is known for its positive effects on skin health, stress relief and promoting sleep. However, research on the impact of GBL on sleep is limited despite various research, and there is currently no conclusive understanding of the mechanisms for treating or improving sleep and related disorders.

The present study work evaluated the effects of GABALAGEN(GBL), a low-molecular-weight collagen infused with GABA, through receptor binding assays. The sedative effects of GBL were investigated through electroencephalography (EEG) analysis in the electro foot shock (EFS) stress-induced sleep animal model and then we examined the expression orexin, GABAA receptor in the brain region using immunohistochemistry.

2. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

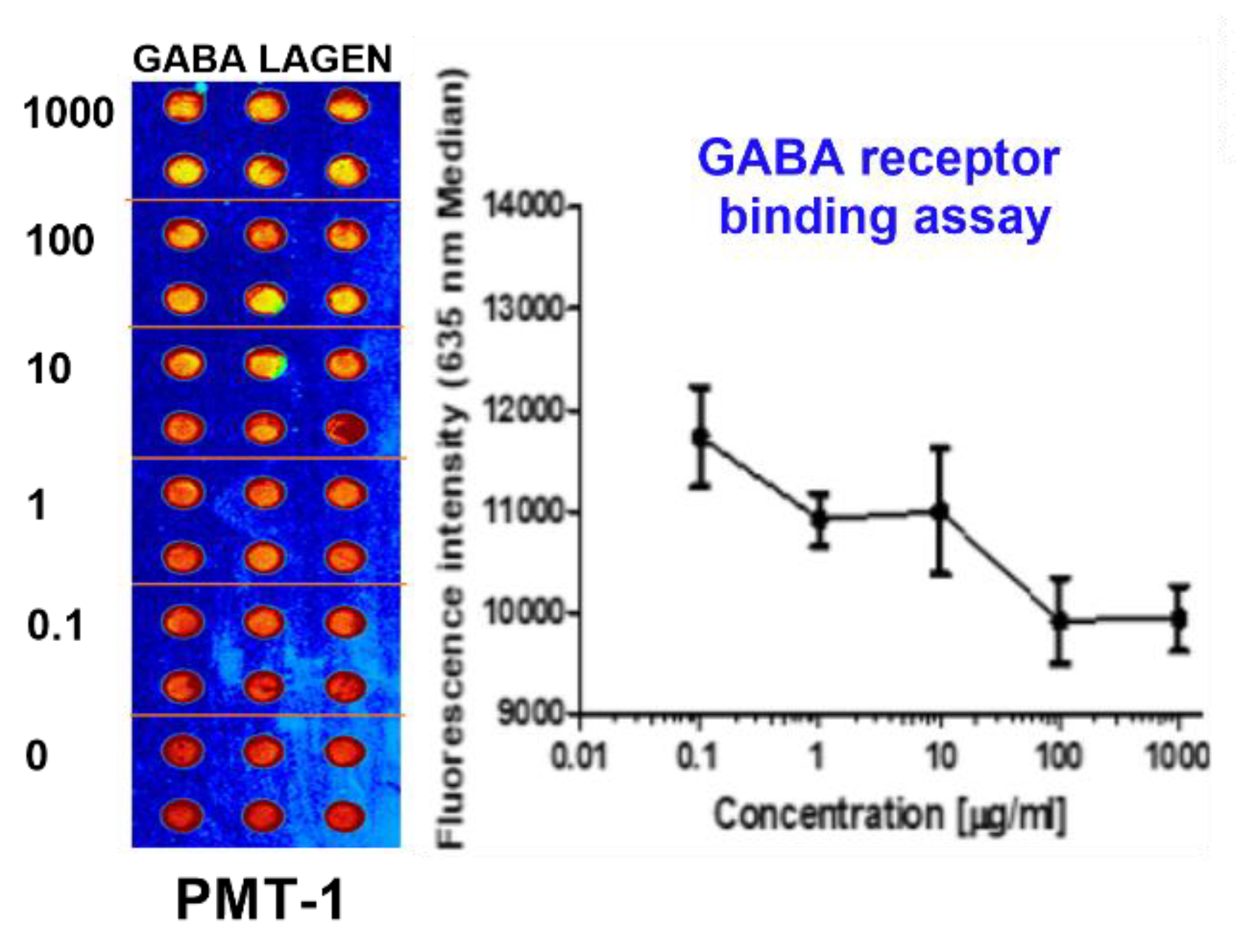

2.1. GABAA and 5-HT2c Receptor Binding Assay

As shown in

Figure 1, the binding activities of GBL to the GABA

A receptor, indicative of its role as a GABA

A receptor agonist, were substantiated. The IC50 value for GBL in this context was measured at 31. 5 µg/mL (

Figure 1).

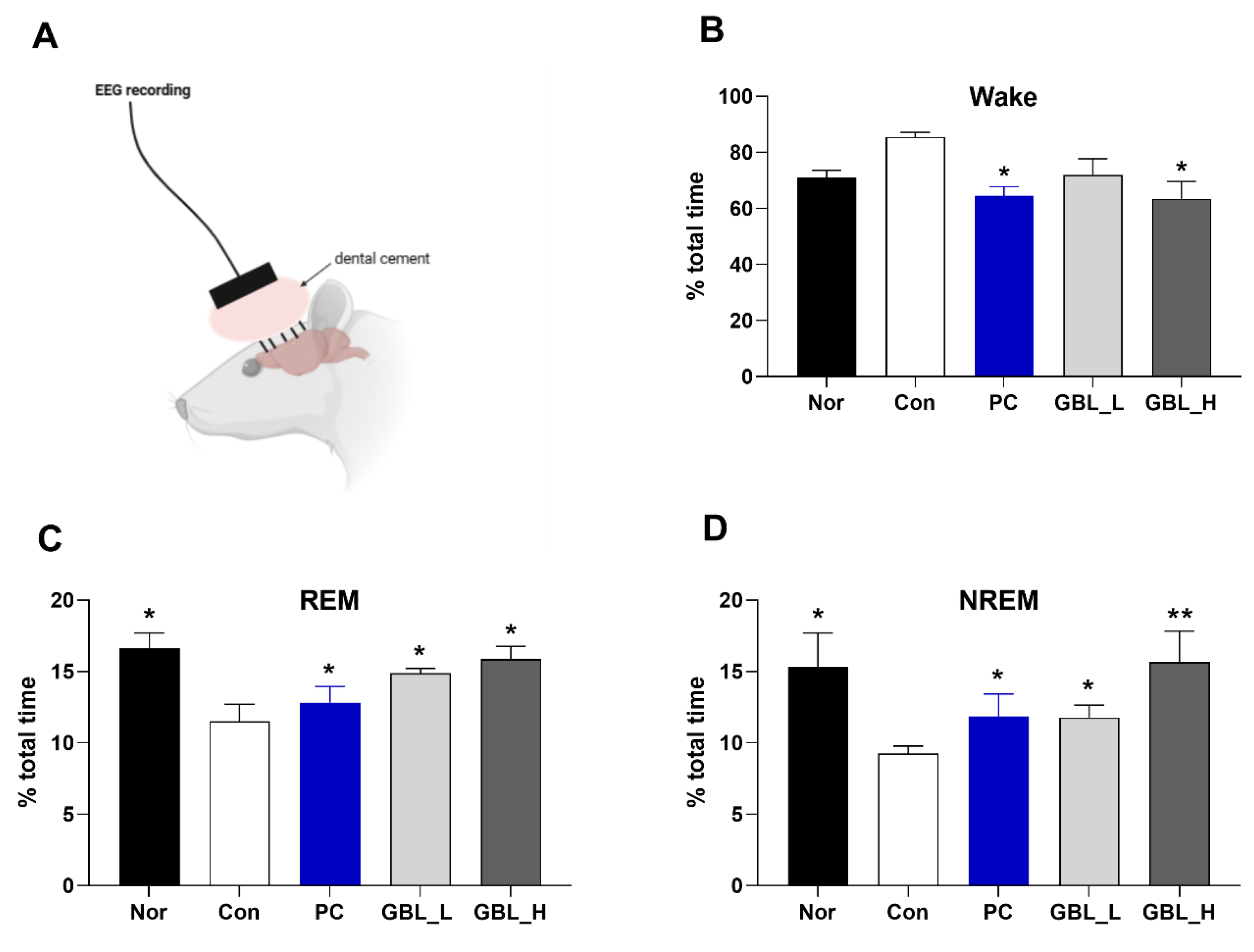

2.2. Effect of GBL on EEG Sleep Architecture and Profile

The effect of GBL on EEG sleep architecture and profile was investigated. There was a trend increase in wake time of Con group (

P > 0.05,

Figure 2A), however the GBL_H-treated group showed slightly increased wake time compared to the Con group (

P < 0.05). Also, the Con group was markedly decrease in REM (

P < 0.05, Figure. 2B), and NREM (

P < 0.05, Figure. 2C), compared to that of the Nor group. However, after treatment of GBL, percent of total time of REM and NREM significantly and dose-dependently increased compared to the Con group (REM:

P < 0.05,

Figure 2B; NREM:

P < 0.05,

Figure 2C).

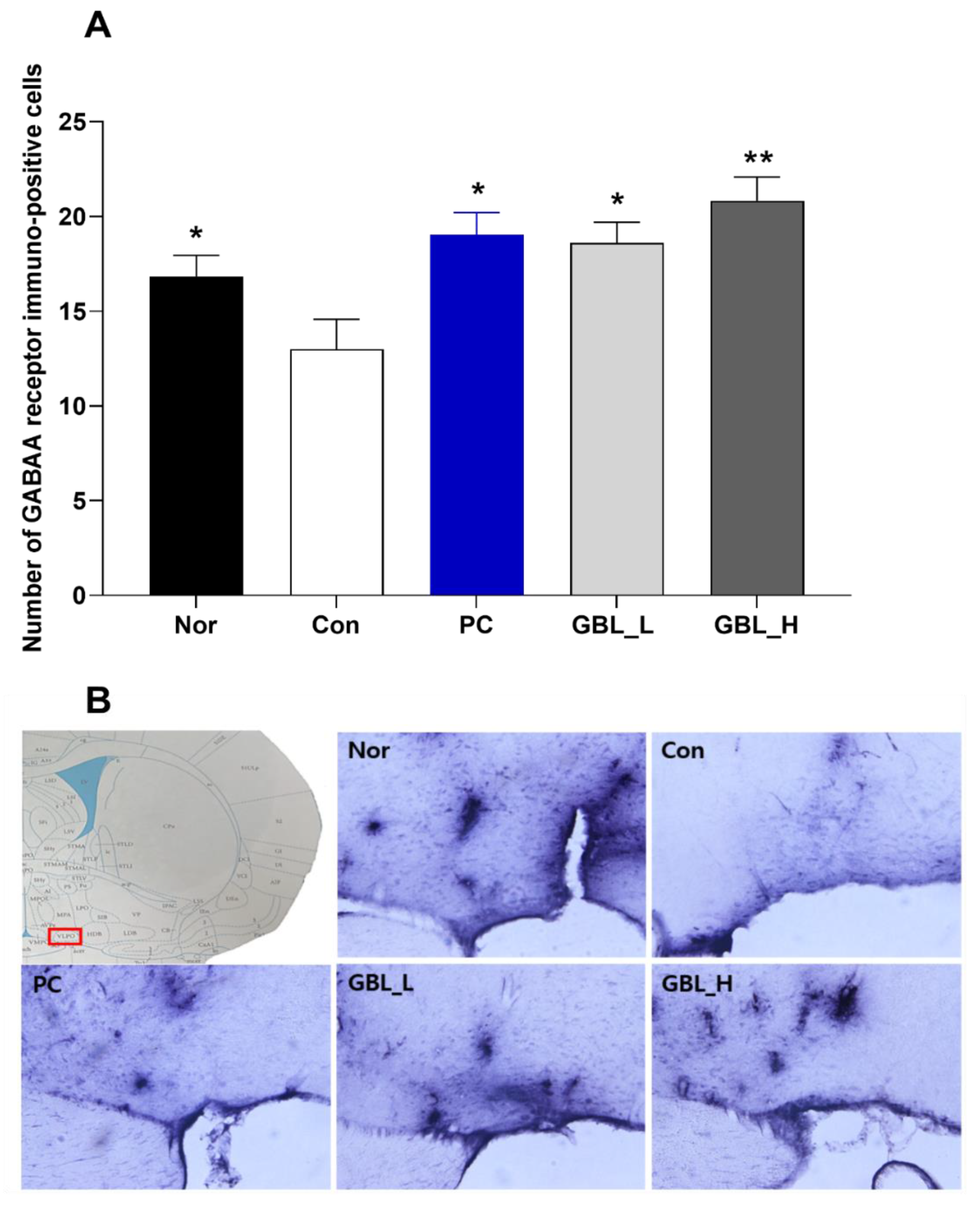

2.3. Effect of GBL on the Number of GABAA Receptor Positive Cells in the Ventrolateral Preoptic Nucleus (VLPO)

We measured GABA

A receptors immunoreactivity in the VLPO (

Figure 3(A) and (B)). The numbers of GABA

A receptor immuno-positive cells were significantly decreased in the Con group (

P < 0.05,

Figure 3(A) and (B)). However, the GBL-treated groups showed that the expression of GABA

A receptor immune-positive cells in the VLPO were markedly and dose-dependently increased compared to the Con group (

P < 0.05).

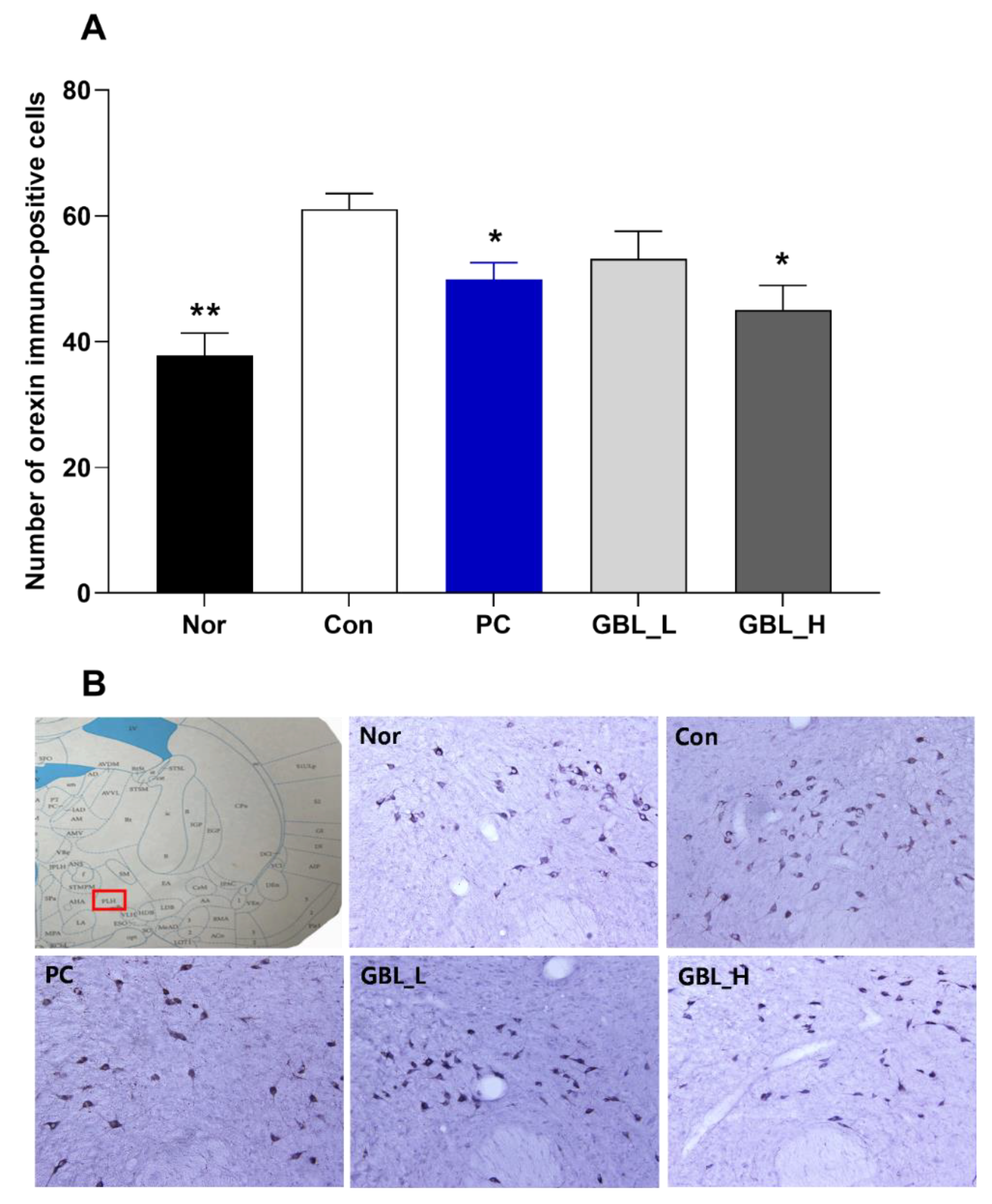

2.4. Effect of GBL on the Number of Orexin Positive Cells in the Lateral Hypothalamus (LH)

We measured orexin immunoreactivity in the LH (

Figure 4(A) and (B)). The numbers of orexin immuno-positive cells were significantly increased in the Con group (

P < 0.01,

Figure 4(A) and (B)). However, the GBL-treated groups showed that the expression of orexin immune-reactive cells in the LH were significantly decreased compared to the Con group (

P < 0.05).

3. Discussion

Present study found that in the binding assay, GBL displayed binding affinity to GABAA receptor (IC50 value, 31.5µg/mL) and 5-HT2c receptor (IC50 value, 7.14µg/mL). Also, after treatment of GBL, percent of total time of REM and NREM were significantly and dose-dependently increased compared to the Con group. Consistent with behavioral results, the GBL-treated groups showed that the expression of GABAA receptor immune-positive cells in the VLPO were markedly and dose-dependently increased compared to the Con group. Also, the GBL-treated groups showed that the expression of orexin immune-reactive cells in the LH were significantly decreased compared to the Con group. GBL showed efficacy and potential to be used as an anti-stress therapy to treat sleep deprivation through antagonism of GABA receptors and consequent inhibition of orexin activity.

Stress can have a significant, long -lasting negative impact on health including changes in behavior and sleep [

8,

9,

10]. Sleep reactivity tends to cause sleep disturbances during environmental disturbances, pharmacological issues, or stressful life events [

20]. As a result, individuals with highly responsive sleep systems are prone to insomnia disorders after stressors, pose a risk of psychopathology, and potentially hinder their recovery from traumatic stress [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Therefore, there is tremendous value in improving sleep responsiveness, creating a robust sleep system for stress exposure, and ultimately preventing insomnia and subsequent consequences.

GABALAGEN (GBL) is a type of collagen with a low molecular weight that contains GABA, which has the same structure as collagen molecules. GBL is known for its positive effects on skin health, stress relief and promoting sleep. We measured GABA

A receptors immunoreactivity in the VLPO. The numbers of GABA

A receptor immuno-positive cells were significantly decreased in the Con group. However, the GBL-treated groups showed that the expression of GABA

A receptor immune-positive cells in the VLPO were markedly and dose-dependently increased compared to the Con group. Previous studies proved that many herbal medicines have been proposed to enhance GABAergic signaling, many through interactions with the GABA

A receptor [

28,

29,

30,

31].

Orexin neurons are characterized by wakefulness-promoting activity, reaching peak firing rates during wakefulness [

32,

33,

34], and exhibiting the highest extracellular levels of orexin during wakefulness [

35]. The LH coordinates sleep-promoting activities, and disruptions in orexin function may upset the delicate balance between sleep and wakefulness, thereby contributing to a spectrum of sleep-related problems [

36,

37,

38]. This emphasizes the importance of investigating the role of the LH and orexin in comprehending and addressing sleep-related disturbances [

33,

38]. We found that GBL decreased expression of Orexin positive cells in the LH region. GBL may decrease Orexin in the LH, leading to a reduction in arousal and potentially enhancing the quality of sleep.

Taken together, these data suggest that earthing mats may be helpful in stress management via the regulation of GABAergic mechanisms. In light of such limitations, our finding provides preliminary evidence of the safety of GBL and their potential to improve sleep quality in an animal model.

4. Materials and Methods

Preparation of GBL

GBL was acquired from Marine Bioprocess Co., Ltd. (Busan, Republic of Korea). GBL production required two consecutive fermentations via Lactobacillus brevis BJ20 (accession No. KCTC 11377BP) and Lactobacillus Plantarum BJ21 (accession No. KCTC 18911P). Seed media composed of 1% yeast extract (Choheung, Ansan, Korea), 0.5% glucose (Choheung, Ansan, Korea), and 98.5% water was sterilized for 15 min at 121 °C before being inoculated with 0.02% BJ20 and 0.02% Lactobacillus Plantarum BJ21 and cultured for 24 h at 37 °C separately. For the first fermentation, 10% (v/v) of the Lactobacillus brevis BJ20 cultured seed media was fermented in a fermentation medium (yeast extract 2%, glucose 0.28%, collagen 29% [Geltech Co., Ltd., Busan, Republic of Korea], L-glutamic acid 5.5% [Samin chemical, Siheung, Korea], water 63.22%) at 37 °C for 24 hr. Then, 10% (v/v) of BJ21 cultured seed medium was added and fermented at 37 °C for a further 24 hr. The fermentation medium was sterilized and spray-dried to prepare GBL powder samples.

GABA Receptor Binding Assay

The GABA receptor was sourced from rat brain tissue. The Protein Chip was obtained from Proteogen, Cy5-labeled muscinol were acquired from Peptron. The stock buffer for the GABA receptors comprised 50 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7.4), 0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10% sucrose. The GABA receptor-binding assay buffer comprised 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at pH 7.4. The receptor (50 µg/mL) was immobilized on the Protein Chip, serving as a substrate to capture protein, for 16 h at 4 °C. After double washing in 0.05% phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBST) for 10 min and drying with Nitrogen gas (N2), the Protein Chip underwent a 1-hour blocking step at room temperature using 3% BSA. Following three washes with PBST and drying, Cy5-labeled muscimol (500 µM, with 30% glycerol in PBS as a buffer) and GBL (using 30% glycerol in PBS as a buffer) were applied to the Protein Chip and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the Protein Chip was rinsed with PBST and DW and dried under a stream of N2 gas. GBL, dissolved in ethanol and diluted to the desired concentration using PBS, covered a concentration range from 1,000 µM to 15.625 µg/mL. Muscinol were used as negative controls. GBL was used to evaluate the sedative

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Samtako (Osansi, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea). These animals were accommodated in a climate-controlled environment with temperatures maintained between 20 °C to 25 °C and humidity levels set at 45% to 65%, following a 12-hour light and 12-hour dark cycle (lights on at 8 a.m.). Food and water were provided ad libitum throughout the study. The laboratory animals were handled and treated in compliance with the guidelines outlined by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) National Institute of Toxicological Research, per the standards for laboratory animal care and usage (Approval No. KHUASP[SE]-14-051).

Surgery

The subjects were divided into five groups: normal (Nor; n = 7), control (con; n = 8), low-dose GBL-treated (GBL_L; n = 8), high-dose GBL-treated (GBL_H; n = 7), and diazepam-treated (DZP; n = 7). Electroencephalogram (EEG) electrodes were surgically implanted to facilitate polygraphic recordings, following the guidelines delineated in the Paxinos and Watson stereotaxic atlas [

19]. Surgical anesthesia was induced with intraperitoneal pentobarbital (40 mg/kg). Subsequently, the rats were subjected to chronic implantation of a head mount. The transmitter body was subcutaneously placed off the midline, posterior to the scapula, secured to the skin, and stabilized using three sutures. Skull-mounted electrodes were secured with screws and dental cement. All surgical interventions were performed using a stereotaxic methodology in an aseptic environment. Postoperatively, each rat was allowed a 7-day recovery period in separate transparent enclosures. After electroencephalogram (EEG) operation, the animals received electro foot shock (EFS) once a day for 5 days. EFS was administered in accordance with the following conditions at random: frequency = 10 times in 3 s; intensity = 3 mA; duration = 5 min.

Methology of EEG Recording

Following the recovery phase, the rats were acclimated to the recording settings before testing. GBL_L, GBL_H, and DZP were prepared in 0.9% saline (GBL_L concentration = 100 mg/kg, GBL_H concentration = 250 mg/kg, DZP concentration = 10 mg/kg) and orally administered for five consecutive days before the EEG recording commenced. The oral administration of saline, GBL_L, GBL_H, and DZP was performed 10 minutes before the EEG recording sessions. The recordings were initiated at 8:00 p.m., capturing 12 h of EEG recordings and activity in all subjects. The cortical EEG signals were amplified (x 100), filtered through a low-pass filter at 100 Hz, digitized at a sampling rate of 200 Hz, and recorded using a PAL-8200 data acquisition system from Pinnacle Technology Inc. The recordings were performed at a chart speed of 25 mm/s.

The SleepSign Ver. 3 software (Kissei Comtec, Nagano, Japan) automatically classified sleep-wake states into three categories: wakefulness (Wake), rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and NREM sleep. Sleep latency was defined as the duration from the administration of the sample to the onset of the initial uninterrupted NREM sleep episode, lasting a minimum of 2 min and not interrupted by more than six 4-second epochs that were not scored as NREM sleep.

Immunohistochemistry

After transcranial perfusion, the rat brains were removed with 4% formaldehyde solution (Sigma-Aldrich Co.), post-fixed in the same fixative for 24 h, and placed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 20% sucrose for 72 h. Serial 30 µm-thick coronal sections were cut using a cryostat microtome (CM1850UV; Leica Microsystems Inc., Wetzlar, Germany) and stored at -20 °C; they were histochemically processed as free-floating sections. Sections were washed three times with PBST. Primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies against orexin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) were diluted to 1:800. Antibody targeting the GABAA receptor (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) was diluted to 1:800. The sections underwent a 12-hour incubation at 4 °C with constant agitation. After rinsing with PBST, a 2-hour incubation at room temperature was performed using a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) diluted to 1:200 in PBST with 2% v/v normal goat serum. Subsequently, the sections were exposed to an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex reagent (Vector Laboratories) for 2 h at room temperature. After further rinsing with PBST, the tissues were developed using a DAB substrate kit (Vector Laboratories). The final steps included mounting the sections on slides, air-drying, and covering them for microscopic observation.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (IBMⓇ SPSSⓇ Statistics Ver. 23 Chicago, IL, USA). For multiple comparisons, behavioral data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to identify significant differences among groups. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

In summary, GBL showed efficacy and potential to be used as an anti-stress therapy to treat sleep deprivation through antagonism of GABA receptors and consequent inhibition of orexin activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S.; Data curation, H.P., and W.J.; Writing, H.P., and I.S.; Formal analysis, W.J. and H.P.; Investigation, I.S.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Foundation of Korea, grant number NRF-2021R1A2C1093825.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University (protocol code KHUASP[SE]-14-051).” for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

References

- Cicolin, A.; Ferini-Strambi, L. Focus on Multidisciplinary Aspects of Sleep Medicine. Brain sciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miletínová, E.; Bušková, J. Functions of Sleep. Physiological research 2021, 70, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, R.S.; Martínez-García, M.; Rapoport, D.M. Sleep apnoea in the elderly: a great challenge for the future. The European respiratory journal 2022, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Rosillo, M.G.; Vega-Robledo, G.B. [Sleep and immune system]. Revista alergia Mexico (Tecamachalco, Puebla, Mexico : 1993) 2018, 65, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Z.L.; Eigenberger, P.M.; Sharkey, K.M.; Conroy, M.L.; Wilkins, K.M. Insomnia and Other Sleep Disorders in Older Adults. The Psychiatric clinics of North America 2022, 45, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopheide, J.A. Insomnia overview: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and monitoring, and nonpharmacologic therapy. The American journal of managed care 2020, 26, S76–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlyk, A.C.; Morrison, A.R.; Ross, R.J.; Brennan, F.X. Stress-induced changes in sleep in rodents: models and mechanisms. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2008, 32, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaSilva, J.K.; Lei, Y.; Madan, V.; Mann, G.L.; Ross, R.J.; Tejani-Butt, S.; Morrison, A.R. Fear conditioning fragments REM sleep in stress-sensitive Wistar-Kyoto, but not Wistar, rats. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry 2011, 35, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polta, S.A.; Fenzl, T.; Jakubcakova, V.; Kimura, M.; Yassouridis, A.; Wotjak, C.T. Prognostic and symptomatic aspects of rapid eye movement sleep in a mouse model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 2013, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Palacios, G.; Velazquez-Moctezuma, J. Effect of electric foot shocks, immobilization, and corticosterone administration on the sleep-wake pattern in the rat. Physiology & behavior 2000, 71, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, C.L.A.; Adamantidis, A.; Burdakov, D.; Han, F.; Gay, S.; Kallweit, U.; Khatami, R.; Koning, F.; Kornum, B.R.; Lammers, G.J.; et al. Narcolepsy - clinical spectrum, aetiopathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nature reviews. Neurology 2019, 15, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blattner, M.; Maski, K. Narcolepsy and Idiopathic Hypersomnia. Sleep medicine clinics 2023, 18, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemelli, R.M.; Willie, J.T.; Sinton, C.M.; Elmquist, J.K.; Scammell, T.; Lee, C.; Richardson, J.A.; Williams, S.C.; Xiong, Y.; Kisanuki, Y.; et al. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell 1999, 98, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornum, B.R.; Knudsen, S.; Ollila, H.M.; Pizza, F.; Jennum, P.J.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Overeem, S. Narcolepsy. Nature reviews. Disease primers 2017, 3, 16100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollu, P.C.; Kaur, H. Sleep Medicine: Insomnia and Sleep. Missouri medicine 2019, 116, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gottesmann, C. GABA mechanisms and sleep. Neuroscience 2002, 111, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jo, K.; Hong, K.B.; Han, S.H.; Suh, H.J. GABA and l-theanine mixture decreases sleep latency and improves NREM sleep. Pharmaceutical biology 2019, 57, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamatsu, A.; Yamashita, Y.; Maru, I.; Yang, J.; Tatsuzaki, J.; Kim, M. The Improvement of Sleep by Oral Intake of GABA and Apocynum venetum Leaf Extract. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology 2015, 61, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxinos, G.; Watson, C.; Pennisi, M.; Topple, A. Bregma, lambda and the interaural midpoint in stereotaxic surgery with rats of different sex, strain and weight. Journal of neuroscience methods 1985, 13, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reffi, A.N.; Kalmbach, D.A.; Cheng, P.; Drake, C.L. The sleep response to stress: how sleep reactivity can help us prevent insomnia and promote resilience to trauma. Journal of sleep research 2023, 32, e13892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Jones, E.C.; Clark, K.P.; Jefferson, F. Sleep disturbances and post-traumatic stress disorder in women. Neuro endocrinology letters 2014, 35, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horenstein, A.; Morrison, A.S.; Goldin, P.; Ten Brink, M.; Gross, J.J.; Heimberg, R.G. Sleep quality and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Anxiety, stress, and coping 2019, 32, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinhausen, C.; Prather, A.A.; Sumner, J.A. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep, and cardiovascular disease risk: A mechanism-focused narrative review. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association 2022, 41, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.E.; Brownlow, J.A.; Woodward, S.; Gehrman, P.R. Sleep and Dreaming in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Current psychiatry reports 2017, 19, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, B.A.; Brock, M.S.; Brager, A.; Collen, J.; LoPresti, M.; Mysliwiec, V. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Traumatic Brain Injury, Sleep, and Performance in Military Personnel. Sleep medicine clinics 2020, 15, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, S.; Wu, D.J.H.; Wang, J.; Qian, Y.; Ye, D.; Mao, Y. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences 2022, 31, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, R.; Yang, L.H.; Tang, X.D. [A Review of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Sleep Disturbances]. Sichuan da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban = Journal of Sichuan University. Medical science edition 2021, 52, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisden, W.; Yu, X.; Franks, N.P. GABA Receptors and the Pharmacology of Sleep. Handbook of experimental pharmacology 2019, 253, 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, O.; Ferini-Strambi, L.; Giacomoni, E.; Pellegrino, P. Herbal Remedies and Their Possible Effect on the GABAergic System and Sleep. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.E.; Spratt, T.J.; Kaplan, G.B. Translational approaches to influence sleep and arousal. Brain research bulletin 2022, 185, 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; Ahn, Y.; Cho, H.J.; Kwak, W.K.; Jo, K.; Suh, H.J. Chemical compositions and sleep-promoting activities of hop (Humulus lupulus L.) varieties. Journal of food science 2023, 88, 2217–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.E. Arousal and sleep circuits. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogavero, M.P.; Godos, J.; Grosso, G.; Caraci, F.; Ferri, R. Rethinking the Role of Orexin in the Regulation of REM Sleep and Appetite. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scammell, T.E.; Arrigoni, E.; Lipton, J.O. Neural Circuitry of Wakefulness and Sleep. Neuron 2017, 93, 747–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, M.D.; Kilduff, T.S. The Neurobiology of Sleep and Wakefulness. The Psychiatric clinics of North America 2015, 38, 615–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falup-Pecurariu, C.; Diaconu, Ș.; Țînț, D.; Falup-Pecurariu, O. Neurobiology of sleep (Review). Experimental and therapeutic medicine 2021, 21, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koob, G.F.; Colrain, I.M. Alcohol use disorder and sleep disturbances: a feed-forward allostatic framework. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppi, P.H.; Fort, P. Sleep-wake physiology. Handbook of clinical neurology 2019, 160, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).