1. Introduction

End-stage organ failure threatens the lives of millions of affected people world-wide and tremendously diminishes their quality of life. It poses a profound challenge, with organ transplantation often being the only available long-term treatment option. However, there remains a substantial gap between the demand for respective donor organs and their availability. [

1,

2,

3]

Addressing this pressing issue one promising avenue is xenotransplantation.

Nevertheless, the immunological mismatch between donor and recipient species is yet one of the most considerable hurdles to overcome with regard to possible future xenotransplantation approaches. Scenarios of different mechanisms of graft rejection, including hyperacute graft rejection (HAR), which leads to immediate graft failure upon transplantation, are relevant consequences of species-related immunological differences. [

4] HAR represents a fast and very strong immune reaction mediated by the binding of preformed antibodies directed to particular xenoantigens present on the cellular surfaces of transplanted organs and tissues. With respect to pig-to-human xenotransplantation settings especially surface glycans play a pivotal role in early graft rejection. Several glycan structures with a relevant meaning in terms of pig-to-human xenotransplantation are known today i.e. αGal, Neu5Gc, and Sda. As in the nature of things, binding of preformed and induced antibodies primarily occurs on endothelial cells (ECs) lining the vasculature of the transplant, which leads to subsequent complement activation and following cell-mediated cytotoxicity, EC activation, and different vascular effects like thrombosis and vasoconstriction finally resulting in early organ failure. [

5,

6]

Today’s most common approach in order to prevent HAR in pig-to-primate xenotransplantation is based on the utilization of organs and tissues derived from specific genetically engineered donor pigs. Enzymes involved in the synthesis of the three known porcine xenogeneic surface glycans (αGal, Neu5Gc, and Sda) are genetically knocked out, leading to an overall reduced binding of human IgG- and IgM- antibodies to respective porcine tissues and cells. [

7,

8]

However, recent investigations have shown, that even tissues derived from respective triple knock-out pigs still possess particular immunogenicity in contact with the human immune system [

9] suggesting the existence of additional xeno-antigenic epitopes on porcine endothelial cells (PEC), which are targeted by preformed or at least induced human antibodies. [

9,

10,

11,

12] As these structures are not yet identified, respective genetic engineering of potential donor pigs is not feasible.

In 2003, De Bank et al. described a method to label and extract cell-surface sialic acid-containing glycans from living animal cells. [

13] This method used mild concentrations of sodium periodate (NaIO

4) to selectively introduce an aldehyde at the glycerol side chain of sialic acids. [

14] At higher concentrations, NaIO

4 can also oxidize vicinal diols within the cyclic sugar backbone enabling oxidation of a broader spectrum of glycans. [

15] Therefore, the NaIO

4-treatment is likely to also chemically modify immunogenic glycans. Thus, NaIO

4 oxidation represents a promising strategy in xenotransplantation for modification of cells and tissues with the aim to destroy immunogenic glycan epitopes against which preformed antibodies might exist within the recipient. In this study, we used porcine endothelial cells (PECs) and porcine tissues to investigate the suitability of NaIO

4-treatment to destroy cellular glycan antigens using αGal as well-known epitope and investigated the effect on the viability of living PECs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Tissue Samples from Porcine Thoracic Aorta

Pigs were bred at the Ferkelerzeugergemeinschaft Coppenbrügge and got delivered to the central animal facility of Hannover Medical School. Explantation of the tissue samples was performed from euthanized animals in an animal operating room under sterile conditions. All pigs included in this study were German landrace crossed with Duroc females and weighed between 31-40 kg prior explantation. Retrieval of aortic sections was conducted secondary to lung procurement which was the primary reason for the animal experiment and which had been approved by an external ethics committee (Lower Saxony State Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety, LAVES, Oldenburg/Germany). Aortic sections with the length of 10 cm were dissected from the descending part of the thoracic aorta. After dissection tissues were stored for a maximum of 4 hours in Ringer’s solution at 4°C.

2.2. Isolation of PECs from Tissue Samples

Connective tissue was removed from the aorta. Afterwards, aortic sections were rinsed in PBS in order to remove tissue debris. Subsequently, aortic sections were cut open lengthwise and placed on top of a 12-well lid with the luminal side up. In order to allow cellular isolation from a specific area, a 3D-printed form defining an area of 20 mm x 40 mm was clamped onto the vessel with spring clamps. Detachment of PECs was conducted by application of 7 mL of collagenase Type 2 (Worthington Biomedical) containing 650 U/mL in PBS onto the vessel area for 8 min at room temperature. Afterwards, collagenase solution containing the detached cells was collected and mixed with Medium 199 (Lonza) containing 10% FCS (PAN Biotech) in 1:1 ratio. Cell scrapers was used in order to support cellular detachment after collagenase treatment. Scrapers were rinsed with Medium 199 containing 10% FCS. In order to maximize the numbers of isolated cells, luminal vessel sides were washed again with PBS, which was collected thereafter as a third fraction. All three preparations were then centrifuged for 5 min 400 xg and supernatants were discarded. Cell pellets were resuspended in 5 mL EGM-2 (Lonza) with additional 5% FCS and cells were subsequently seeded onto separate T-25 cell culture flasks and cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2.

2.3. Cell Monolayer Microfluidic System

The BioFlux one microfluidic system (Fluxion Biosciences) was used to assess the efficiency of chemical oxidation under dynamic flow properties in order to closely emulate physiological conditions. Initially, 48-well microflow plates were coated with 100 μg/mL fibronectin (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 37°C. Channels were washed thereafter with EGM-2 at a shear flow of 15 dyne/cm2 and seeded with 10 µl of PECs (135,000 cells) in EGM-2 through the inlet well. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, plates were filled with fresh EGM-2 and further incubated for 24 hours before use.

2.4. Solubility of Sodium Periodate

10 mM NaIO4 (Honeywell) solutions were prepared in PBS, EBM-2 (Lonza) or isotonic saline (0.9% NaCl) and further diluted to 1 mM, 2 mM, 3 mM, 4 mM, and 5 mM in the respective solvent. Prepared solutions were stored at 4°C for 24 h. After the cooling period all samples were checked for the appearance of precipitations.

2.5. Oxidation of PECs with NaIO4

For oxidation under static conditions, PECs were seeded into 24-well plates and cultivated as described above until reaching confluency. Oxidation of PECs was performed either at 4°C or 37°C. Plates were placed onto a tumbling shaker at a speed of 25 rpm during the procedure. At first, cells were washed once with PBS, afterwards 500 µl NaIO4 solution (final concentration of 1 – 5 mM in 0.9% NaCl) was applied onto the cells. After respective oxidation time, NaIO4 solutions were discarded and the cells were washed once with cold PBS. Depending on further investigations, cells were cultured in order to perform live/dead analysis or fixed for staining. PECs treated only with PBS were used as untreated control, whereas PECs incubated with 70% methanol for 30 min at 37°C were used as negative controls for the live/dead assays.

For investigation of dynamic flow conditions, cells were seeded into channels of 48-well plates (BioFlux) in a microfluidic system, capable of generating shear stresses ranging from 0-200 dyne/cm². Well plates to be processed were placed on a cooling plate throughout the procedure in order to maintain a constant temperature of 4°C or placed into the BioFlux heating plate at 37°C. After rinsing the cells with HBSS using a shear flow of 10 dyne/cm

2, cells were treated with NaIO

4 solutions at concentrations of 1 – 3 mM for 60 minutes under flow conditions (5 dyne/cm

2 for 10 min, 40 min gravity flow, 5 dyne/cm

2 for 10 min). Controls were treated with PBS only. Post-oxidation, cells underwent washing with PBS twice and were either fixed for staining using 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS or replenished with EGM-2 and cultivated for 24 hours. Human endothelial colony forming cells (ECFCs), kindly provided by Michael Pflaum [

16], were used as negative controls for IL-B4 and serum staining and treated similar to the PBS controls.

2.6. Live/Dead Analysis

After periodate oxidation, cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 with EGM-2 cell culture medium for 24 hours. Culture medium was removed and cells were washed with PBS. LIVE / DEAD™ Viability / Cytotoxicity assay (Invitrogen) was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. In the microfluidic system, cells were washed once with PBS employing a shear flow of 15 dyne/cm². Subsequently, 100 μl of Calcein AM and ethidium homodimer were added to the inlet well followed by flushing the channels with a shear flow of 5 dyne/cm² for 5 min.

2.7. Isolectin-B4 (IL-B4) Staining

Immediately after oxidation, cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, cells were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature followed by incubation with Isolectin-B4-Cy5 (DL-1208, Vector Laboratories Inc.) diluted 1:200 in PBS at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, cells were washed with PBS at room temperature and nuclei were stained using DAPI.

In the microfluidic system, cells were fixed using 4% PFA for 5 minutes applying a shear flow of 15 dyne/cm². Fixed cells were blocked for 1 hour with 1% BSA solution and subsequently incubated with 1:200 diluted Isolectin-B4-Cy5 over night at 4°C. Afterwards, channels were washed with PBS under a shear flow of 5 dyne/cm2. Finally, channels were flushed with 2 drops Mount FluorCare DAPI (Carl Roth) solution applying a shear flow of 10 dyne/cm² for 5 min in order to facilitate nuclear staining.

2.8. Binding of Human Serum

Immediately after oxidation under dynamic conditions, cells were exposed to human serum (blood group 0) for 1 hour applying a shear flow of 20 dyne/cm². Afterwards, cells were fixed with 4% PFA employing a shear flow of 15 dyne/cm² for 5 minutes and subsequently blocked with 500μl 1% BSA solution, employing a shear flow of 15 dyne/cm² for 1 hour. After washing with 1x TBS employing a shear flow of 15 dyne/cm² for 10 minutes, human antibodies were detected applying a FITC-conjugated goat anti-human IgA, IgG, IgM (Heavy & Light Chain) antibody (ABIN100791, Rockland immunochemicals, Inc.) for 1 hour using gravity flow. Supernatant antibodies were removed by rinsing with 1x TBS under a shear flow of 15 dyne/cm2 for 2 minutes. Finally, channels were flushed with two drops of DAPI solution using a shear flow of 10 dyne/cm² for 5 minutes to facilitate nuclear staining.

2.8. VE-Cadherin Staining

PFA-fixed cells were washed with 500 µl PBS and blocked with 2% donkey serum in PBS for 60 minutes at room temperature. After discarding the blocking solution, 200 µl of 1:100 diluted rabbit anti-human CD144 antibody (AHP628Z, AbDSerotec/BioRad) and 1:100 diluted rabbit IgG-Isotype control in PBS (abcam) were applied at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, cells were washed with 500 µl PBS and incubated with 200 µl of a 1:300 diluted Cy3- donkey-anti-rabbit IgG (AbDSerotec/BioRad) for one hour at room temperature. Afterwards, the cells were washed with 500 µl PBS and finally covered with 500 µl PBS.

2.9. Analysis of the Penetration Depth

Thoracic aortic sections were prepared as described above. Aortic sections were then washed with 6 mL of 4°C cold PBS prior application of 6 mL of 2 mM NaIO4 solution for 40 minutes at 4°C. NaIO4 solution was discarded thereafter and the luminal sides of the aortic sections were subsequently washed again with 6 mL PBS at 4°C. Tissue pieces of treated aortic sections were afterwards embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. TM (Sakura) and snap-frozen over liquid nitrogen. Cryosections of 5 µm thickness were prepared using a standard cryotome. Cryosections were fixed with 100 µl 4% PFA for 15 minutes at room temperature. Subsequent IL-B4 staining was performed using the same protocol as described above.

2.10. Quantification of Live/Dead Assays

ImageJ2 image analysis software with Fiji plugin was used to quantify images derived from conducted live/dead assays. On that account, RGB channels were split and the red and green channel were anal

yzed separately. After adjustment of brightness, respective images were processed to binary pictures choosing an appropriate threshold. Binary dots, each representing a cell, were then watershed in order to separate agglomerates of cells. Afterwards, automatized dot counting was performed by ImageJ2 software with Fiji plugin. Respective survival rates (% survival) were finally calculated as:

2.12. Statistics

If not stated otherwise, experiments were performed in biological triplicates using materials from 3 different animals. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-tests using GraphPad PRISM software.

3. Results

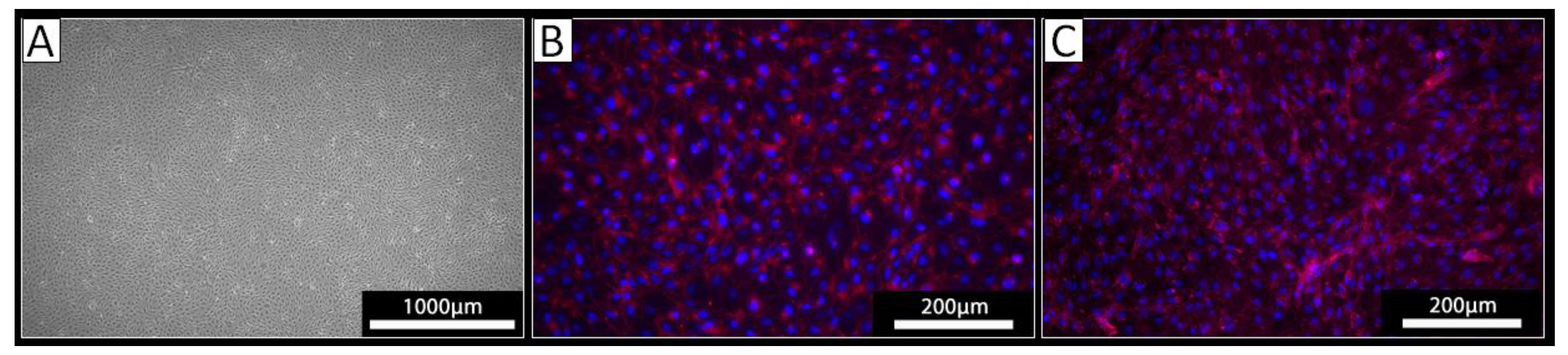

3.1. Isolated Cells Express EC Markers

PECs were isolated from the thoracic aorta of three different pigs using a standard procedure for the isolation of ECs. Cells derived from all three isolations exhibited a typical endothelial cell cobblestone morphology in culture (

Figure 1 A). Staining against VE-cadherin revealed a cell surface localization of this EC marker protein on the cultured cells (

Figure 1 B). The obtained cells were also positive upon staining with the lectin IL-B4 (

Figure 1 C) indicating the expression of αGal-epitopes. Together, these analyses confirmed the EC phenotype of the isolated cells.

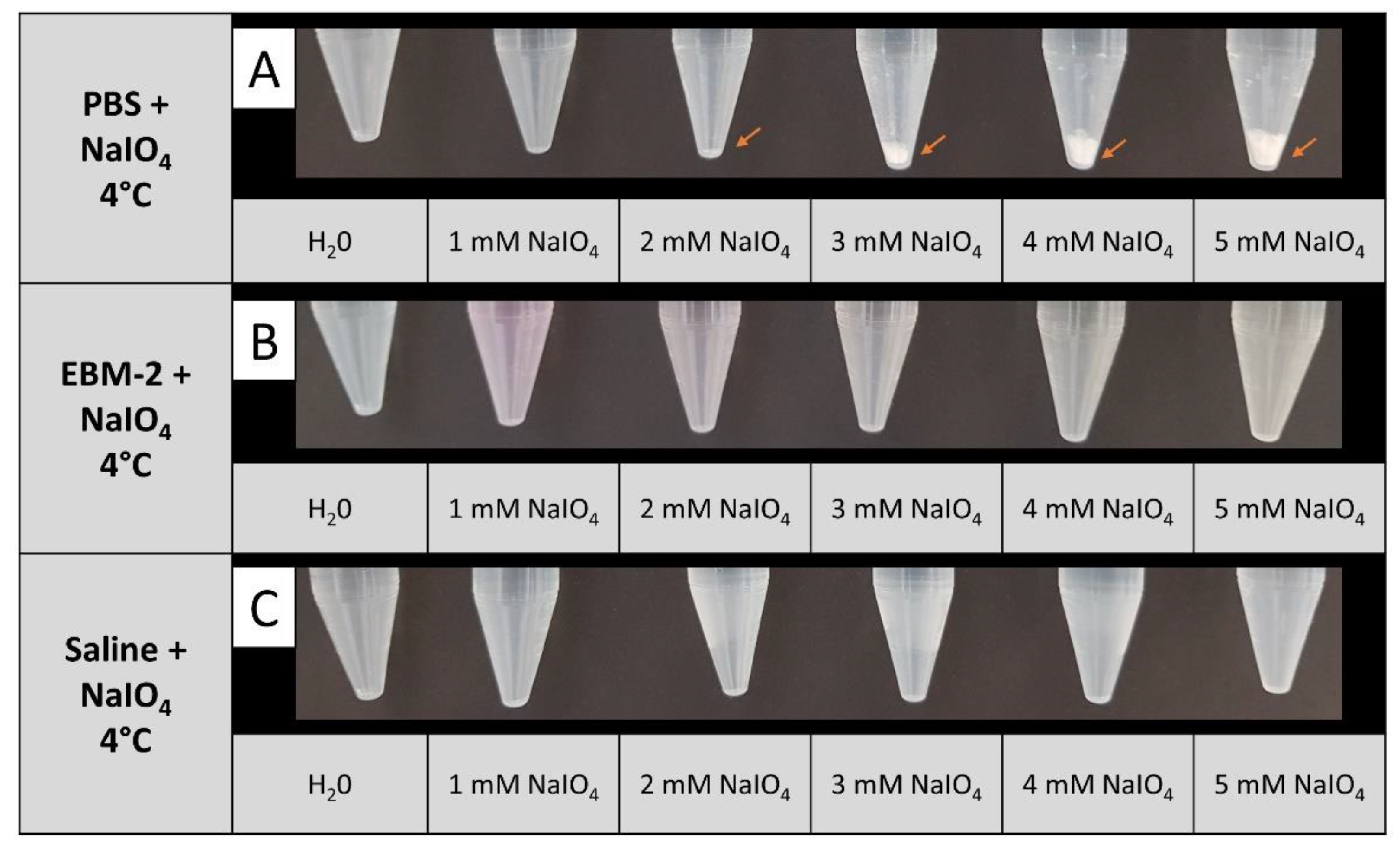

3.2. NaIO4 Can Be Dissolved in Isotonic Saline at Sufficient Concentrations

Periodate oxidation of living cells at 37°C has been described by NaIO

4 dissolved in PBS [

13]. In our experimental setup, different temperature conditions were tested during periodate oxidation. We noted that upon cooling of a NaIO

4 solution in PBS to 4°C, precipitation of a white substance was observed even at 2 mM NaIO

4. The amount of precipitate was augmented with increasing NaIO

4 concentration, implying that NaIO

4 is not fully soluble in 4°C cold PBS at concentrations above 2 mM (

Figure 2 A). In contrast, no precipitation was observed at 4°C up to 5 mM NaIO

4, when EBM-2 or isotonic saline were used as a solvent (

Figure 2 B, C). As EBM-2 medium contains glucose, which is likely to react with NaIO

4, we decided to apply saline as solvent for NaIO

4 for all further experiments.

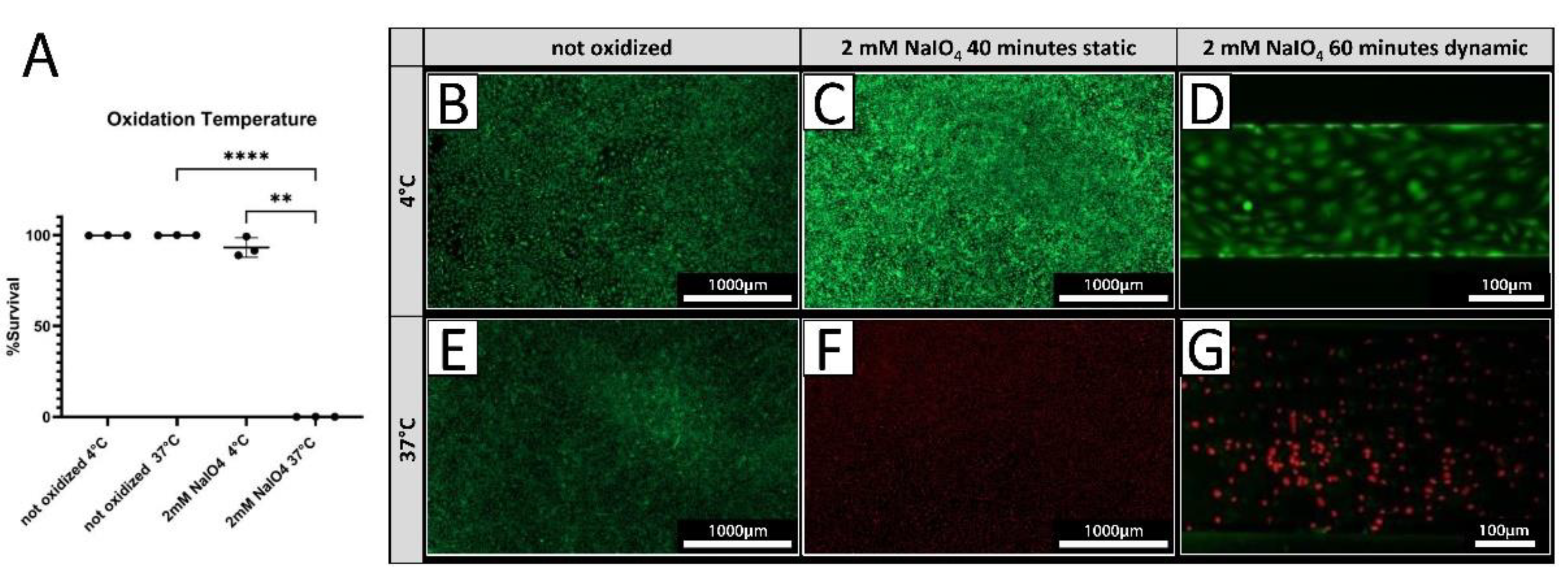

3.3. Cell Survival Can Be Optimized upon Oxidation at Low Temperature

PECs were treated with 2 mM NaIO

4 under static conditions for 40 minutes at either 4°C or 37°C. Cell viability was assessed 24 hours after treatment by live/dead assay. Treatment at 4°C resulted in 93.0 ± 5.4 % viable cells (

Figure 3 A, C), while only 0.09 ± 0.03 % of PEC were viable after treatment conducted at 37°C (

Figure 3 A, F) compared to a 100% survival of untreated cells at both temperatures (

Figure 4 A, B, E). Under dynamic conditions, no viable PECs could be found after oxidation with 2 mM NaIO

4 at 37°C (

Figure 3 G), whereas most cells were viable when oxidized with 2 mM NaIO

4 at 4°C (

Figure 3 D).

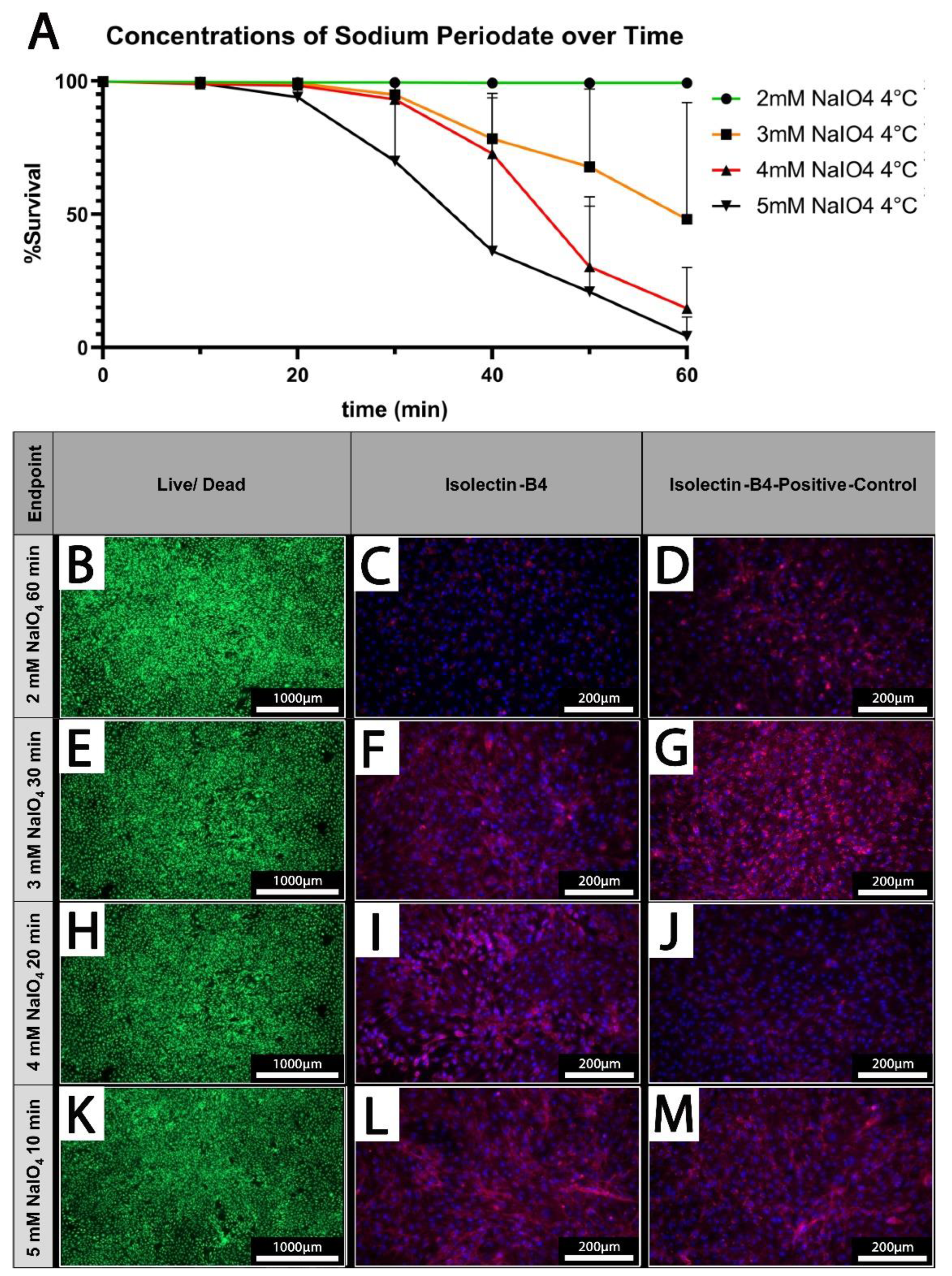

3.4. Increasing Oxidation Time and NaIO4 Concentration Negatively Affect Cell Survival

PECs were treated under static conditions at 4°C with different concentrations of NaIO

4 (2-5 mM) and increasing durations (10-60 minutes). Survival rates of PECs were determined using a live/dead assay. While cellular viability is maintained at 100% upon treatment with 2 mM NaIO

4 even after prolonged treatment up to 60 minutes, higher concentrations of 3 mM, or 4 mM NaIO

4 considerably decrease the survival of PEC when treated for more than 30 minutes (

Figure 4 A)

At 5 mM NaIO

4 viability of PECs was already reduced after 20 minutes of treatment and after 60 minutes, survival rates of only 4.3 ± 7.2% were observed (

Figure 4 A).

3.5. Oxidation of PECs with NaIO4 Reduces Detection of αGal by IL-

Based on our previous analyses, we defined concentrations of periodate and times for treatment at which PECs survived at high rates which were 2 mM NaIO

4 for 60 minutes, 3 mM NaIO

4 for 30 minutes, 4 mM NaIO

4 for 20 minutes, and 5 mM NaIO

4 for 10 minutes at 4°C (

Figure 4 B, E, H, K). These conditions were chosen for the analysis of IL-B4 binding to treated PECs (

Figure 4 C, F, I, L). IL-B4 binding to the cell surface as deduced from staining of cell borders, was considerably reduced in cells oxidized with 2 mM NaIO

4 for 60 min compared to untreated controls (

Figure 4 C, D). The other depicted settings revealed only mild, or no additional reduction of the extent of IL-B4 positive staining (

Figure 4 F, G, I, J, L, M).

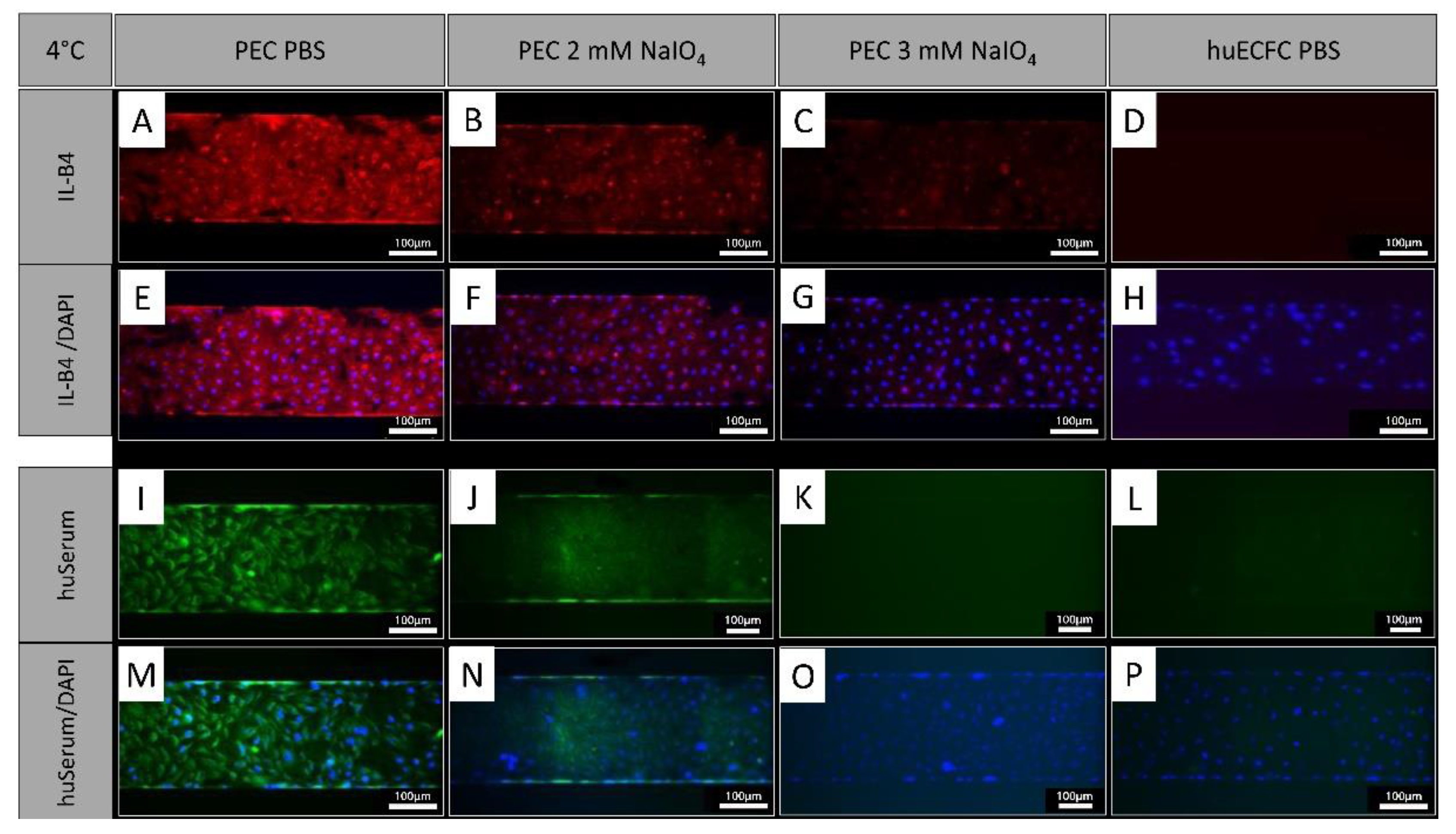

3.6. Binding of IL-B4 and Human Serum Antibodies to Cells is Reduced after Oxidation under Dynamic Conditions

In addition to treatment under static conditions, PECs were treated with NaIO

4 under dynamic conditions employing the BioFlux system. Similar to oxidation under static conditions, cells showed a reduction of IL-B4 staining after an oxidation with 2 mM NaIO

4 for 60 min at 4°C under dynamic conditions (

Figure 5 A, B, E, F). Oxidation with 3 mM NaIO

4 for 60 min further reduced the IL-B4 staining (Figure C, G). Similar observations were made with human serum which showed reduced binding of human antibodies to PEC oxidized for 60 min with 2 mM (

Figure 5 I, J, M, N) and a further reduction with 3 mM NaIO

4 (

Figure 5 K, O). Human ECFC served as negative controls and exhibited even less staining (

Figure 5 D, H, L, P).

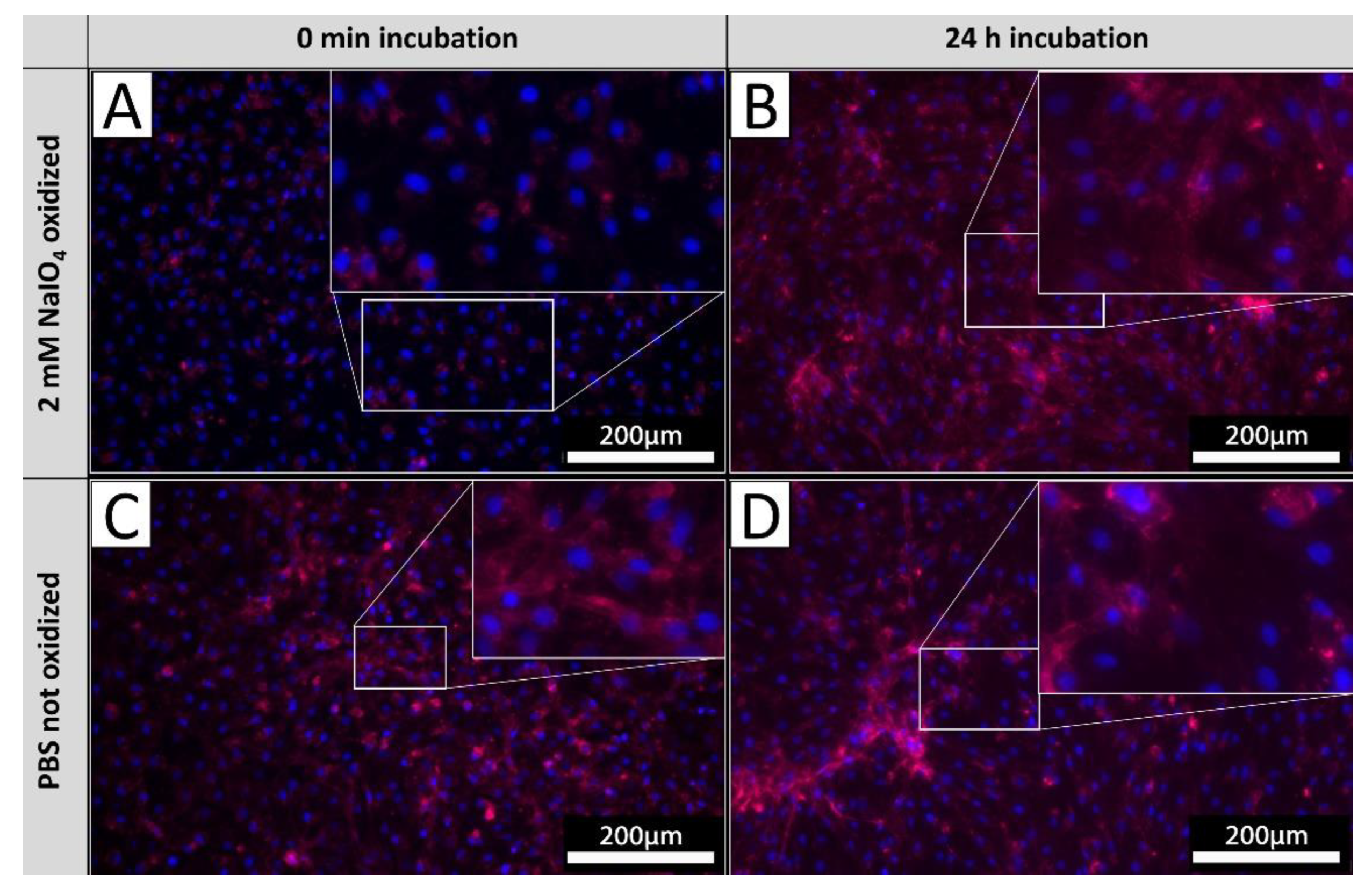

3.7. α. Gal Epitopes on Cell Surfaces Undergo a Quick Turn-Over

In order to investigate the glycan turnover on EC membranes, PECs were cultivated after the oxidation process for 24 hours and subsequently stained with IL-B4. Staining results were afterwards compared to corresponding staining of PECs derived from same isolations directly stained after oxidation as done in previous experiments (

Figure 6). PECs stained directly after oxidation exhibited no staining (

Figure 6 A), whereas PECs cultivated for 24 hours after oxidation exhibited diffuse staining with pronounced accentuation of cellular membranes (

Figure 6 B). Observed intensity of IL-B4 staining did not differ to respective untreated controls (

Figure 6 C, D), indicating a most widely complete turn-over of glycans oxidized before.

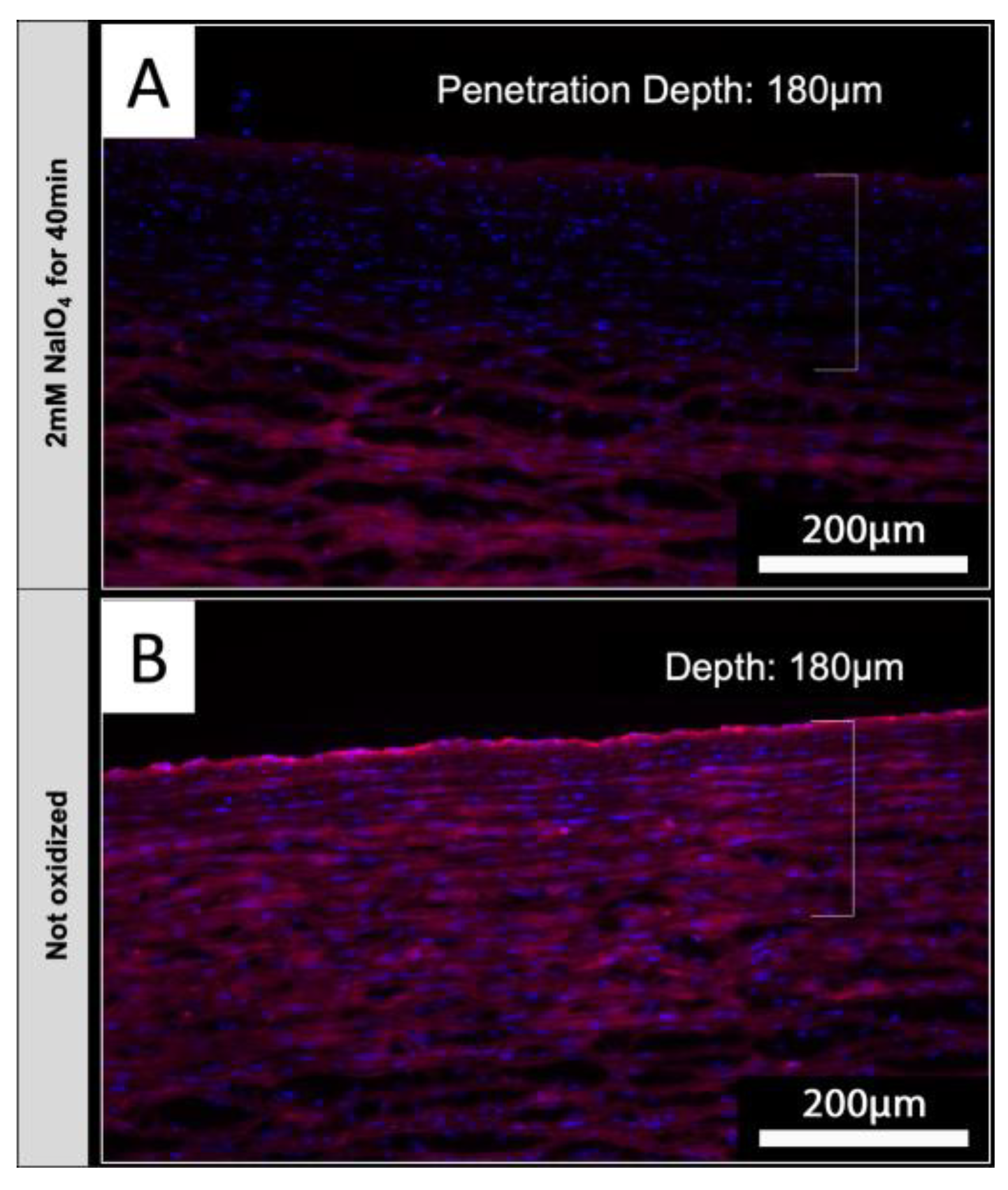

3.8. NaIO4 Can Oxidize Glycans at Deeper Layers upon Diffusion into Native Aortic Tissue

Based on the envisioned application of periodate oxidation for treatment of tissues intended for xenotransplantation, native aortic tissue was used to determine if NaIO

4 treatment does reduce IL-B4 staining also in tissues

. Luminal surfaces of native porcine aortic sections were treated with 2 mM NaIO

4 for 40 minutes at 4°C. Upon staining of tissue sections with IL-B4, it could be shown that periodate was capable to diffuse into the media layers of investigated aortic vessel walls (

Figure 7 A). Staining of endothelial layers appears to be slightly brighter in comparison to underlying vessel layers, but detected intensity of staining was clearly reduced compared to not oxidized controls (

Figure 7 B).

4. Discussion

HAR and acute vascular rejection (AVR) of porcine organs and vascularized tissues are mediated by antibodies binding to xenoantigens on ECs coating the graft-related vessels. Since most of the xenoantigens currently known and characterized are carbohydrates, their removal, or alteration towards non-immunogenic structures are crucial steps in order to reduce the immune response of the human recipient immune system upon exposure to a vascularized porcine transplant. [

9] In this study, we could show that recognition of carbohydrate xenoantigens can be mitigated using simple periodate oxidation, without influencing the vitality of the carrying ECs. By application of this method on the endothelium of a vascularized transplants or blood exposed surfaces in general, hyperacute or acute rejection characteristics of a human immune system towards porcine tissues or organs might be prevented or at least reduced to insignificant extents.

4.1. Porcine Endothelial Cells as Target Cells

In this study, we combined a classical standard protocol for EC isolation with a custom-made device to isolate PECs. Thus, isolated cells exhibited the typical cobblestone endothelial morphology and stained positive for VE-cadherin and IL-B4 indicating an almost pure population of ECs. [

13,

16] ECs have a particular importance with respect to every transplantation scenario including the transplantation of a vascularized graft since they are the first cells of the donor which get in contact with the recipient’s blood flow, which has an eminently relevance in terms of xenotransplantation purposes.

A distinct limitation of this study is the use of only one type of ECs, in particular aortic derived ECs. ECs comprise heterogeneous cell populations with varying properties among each other, depending on their location in the circulatory system. [

16] This variability might also affect their susceptibility to oxidative stress and similarly the properties of their cell surface glycans may differ. Therefore, deduced predictions with respect to other compartments of the porcine circulatory system or whole organs can only be made very careful and most notably require further investigations.

4.2. Oxidation Conditions

Previous studies describe the solubilization of NaIO

4 in PBS prior application as oxidant for cell surface glycans. [

13] However, in our study we observed precipitates when NaIO

4 was solubilized in PBS already at concentrations of 2 mM at 4°C. Most likely, observed precipitations consisted of KIO

4 which is formed upon reaction with potassium ions present in PBS and which is poorly soluble in aqueous solutions [

14]. This prompted us to investigate other solvents for NaIO

4. Cell-culture media, like EBM-2 medium, which would be an ideal diluent for our purposes exhibited no precipitation with NaIO

4 (

Figure 2). However, we decided not to use EBM because NaIO

4 might react with ingredients of the medium e.g. glucose and proteins, thereby altering the effective NaIO

4 concentration. Furthermore, toxic metabolites might be formed as well, which naturally could also relevantly interfere with the achievable results of the experiments conducted in this work. In order to generate reliable concentrations of NaIO

4 and to avoid toxic metabolites we used saline solution for dissolving NaIO

4, which did not lead to any precipitations even at a high concentration of 5 mM NaIO

4 and a low temperature of 4°C (

Figure 2). For future experiments the solvent of choice for NaIO

4 could be optimized by including components that facilitate cell survival but do not interfere with the reaction of NaIO

4.

Additionally, we observed a clear difference in cell survival depending on the temperature at which respective oxidations were conducted. Periodate oxidation at 4°C significantly improved cellular survival rates in comparison to oxidations conducted at 37°C. In this study, we did not perform experiments to elucidate the underlying reasons and mechanisms, but we speculate that due to lower temperatures the uptake of toxic products such as the NaIO

4 itself or already formed aldehydes by the ECs might be reduced. Previous studies suggest, that endocytosis can be reduced to a minimum at 4°C. [

17] A major drawback of periodate oxidation conducted at 4°C is the considerably slower reaction kinetics when compared to respective oxidations performed at 37°C. In order to achieve a similar effectiveness at lower temperatures the incubation time has to be prolonged, which again might cause other relevant side effects. With regard to potential application strategies in the context of intended xenotransplantation scenarios, oxidation at 4°C can be easily combined with cold organ perfusion, which was recently introduced to be highly effective at least when applied in xenogeneic heart transplantations. [

18]

4.4. Xenogenic Epitopes

In our current work, we could show a distinct reduction of IL-B4 binding to porcine tissues and PECs after oxidation with NaIO4, indicating that the αGal epitope, which is recognized by IL-B4, was altered in a way that subsequently hampered the binding capacity of this lectin. In addition, binding of human sera to PECs oxidized by NaIO4 was reduced as well. Therefore, it can be assumed that periodate-mediated oxidation of αGal prevents its recognition by preformed human antibodies as well. Furthermore, based on the broad glycan-spectrum that is affected by the oxidation process, it can be anticipated that also other glycan epitopes to which an immunologically relevant antibody binding is expected to occur upon transplantation might be rendered to be not detectable any longer after this procedure.

However, as described by previous investigations approximately 40-55% of

3H-labeled glycoproteins from cells subjected to periodate oxidation and aniline-catalyzed oxime ligation were afterwards still detectable by subsequent biotin labelling [

14]. This suggests, that not every glycan was modified during described processing. Conclusively, we observed likewise that oxidized PEC still exhibited IL-B4 detection in particular areas surrounding cellular nuclei. Most likely, this can be explained by positive IL B4 detection of not-oxidized glycans present in the Golgi apparatus and other intracellular compartments. Interestingly, these glycans seemed to be protected from the oxidation process conducted in this study and thus could replace oxidized glycans on the cellular surface in the time period after the introduced procedure. Indeed, we observed a recovery of structures positively detectable by IL-B4 staining within 24 hours after initial oxidation indicating the replacement of oxidized glycans with

de novo and thus not oxidized glycans in that time frame. As crucial consequence, the therapeutic window of the beneficial effects of glycan oxidation might be very short and thus is only capable to reduce the severity of early phase hyperacute and acute immune reaction pattern during the first hours after transplantation. On the other hand, the strategy of immune modulation introduced in this study might be very useful for permanently changing potentially xeno-reactive glycans retained in metabolically inactive porcine derived biological implants, for example glutharaldehyde fixed bioprosthetic heart valves.

4.5. Oxidation under Shear Flow Conditions

Experiments were performed in this work under shear flow with the intention to immediately remove toxic byproducts of the oxidation from processed cellular surfaces and by this means to improve cell viability. However, respective experiments included in this study revealed no relevant impact of flow conditions on the cellular survival, suggesting that toxic byproducts might not be a notable cause of decreased cellular viability. One alternative explanation might be a direct cellular uptake of NaIO4 causing deleterious intracellular damages and/or changes of the cellular membranes that are induced by NaIO4 oxidation. During the same experiments, live/dead assays were performed immediately after oxidation revealing cells stained positive for Calcein AM and for nuclear staining as well, indicative for damaged cellular membranes.

4.6. Tissue Penetration Depth

ECs mediate the first contact between the recipient human immune system and a transplanted vascularized xenograft, but shortly after transplantation human cells will migrate into the tissue of the donor organ as well. Therefore, we additionally investigated in this study if NaIO4 mediated oxidation could be applied in porcine donor tissues beyond vasculature as well. Thus, we observed that NaIO4 is capable to penetrate into the examined tissues, even without perfusion through capillaries. This might be relevant in terms of oxidizing whole xenogeneic donor organs in order to further reduce pre-existing immunologic burdens.

4.7. Further Investigations

After demonstrating the proof of principle on PEC monolayers in this study, it remains a crucial necessity to further investigate both immunogenicity and biocompatibility of oxidized PECs as well. In order to improve cellular survival and to expand the therapeutical margin of the techniques introduced in this study the composition of oxidation solution to be applied should be further refined. Another future step in order to further evaluate the potential utility of glycan oxidation approaches will be whole organ perfusion of potential porcine donor organs using ex vivo perfusion systems and strategies.

5. Conclusions

We developed a NaIO4 oxidation protocol that allows chemical modification of glycans impairing their recognition on living PECs by lectins or antibodies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R., A.H., T.G. and F.F.R.B.; methodology, J.T., N.R., S.S. and B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T., N.R. and R.R.; writing—review and editing, B.A., F.F.R.B., T.G., A.H., and R.R.; funding acquisition, A.H., F.F.R.B and T.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) via the TRR127 (Biology of xenogeneic cell and organ transplantation—from bench to bedside) and the German Center for Lung research via the JRG “xenogeneic lung transplantation”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Nils Voß, Doreen Lenz, Daria Wehlage, Mia Goecht, Astrid Diers-Ketterkat and Niveditha Varma for their excellent work and Michael Pflaum for kindly providing human ECFCs. We also want to thank Axel Haverich and Heiner Niemann for their constant encouragement and the administration office of BREATH for supporting our research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Foundation, EI. Yearly Statistics Overview Eurotransplant 2023 [Available from: https://statistics.eurotransplant.org/index.php?search_type=overview&search_text=9023] 05.05.2024.

- Cooper, D.K.C.; Hara, H.; Iwase, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Jagdale, A.; Kumar, V. Clinical Pig Kidney Xenotransplantation: How Close Are We? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020, 31, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaban, R.; Cooper, D.K.C.; Pierson, R.N. , 3rd. Pig heart and lung xenotransplantation: Present status. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022, 41, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, T.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Geng, Z.; Deng, S.; Cheng, C.; Wang, Y. (2022). Current status of xenotransplantation research and the strategies for preventing xenograft rejection. Front. Immunol. 13. [CrossRef]

- Martens, G.R.; Reyes, L.M.; Butler, J.R.; Ladowski, J.M.; Estrada, J.L.; Sidner, R.A.; Eckhoff, D.E.; Tector, M.; Tector, A.J. 2017. Humoral Reactivity of Renal Transplant-Waitlisted Patients to Cells From GGTA1/CMAH/B4GalNT2, and SLA Class I Knockout Pigs. Transplantation 101, e86. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sykes, M. (2007). Xenotransplantation: current status and a perspective on the future. Nat Rev Immunol 7, 519. [CrossRef]

- Ladowski, J.M.; Hara, H.; Cooper, D.K.C. (2024). The Role of SLAs in Xenotransplantation. <italic>105, </italic>300. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.K.C., Ezzelarab, M., Iwase, H., and Hara, H. (2024). Perspectives on the Optimal Genetically Engineered Pig in 2018 for Initial Clinical Trials of Kidney or Heart Xenotransplantation. Transplantation <italic>102, </italic>1974. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemann, H. , and Petersen, B. (2016). The production of multi-transgenic pigs: update and perspectives for xenotransplantation. Transgenic Res 25, 361. [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.P., Layer, J.V., Heja, D., Hirose, T., Lassiter, G., Firl, D.J., Paragas, V.B., Akkad, A., Chhangawala, S., Colvin, R.B., Ernst, R.J., Esch, N., Getchell, K., Griffin, A.K., Guo, X., Hall, K.C., Hamilton, P., Kalekar, L.A., Kan, Y., Karadagi, A., Li, F., Low, S.C., Matheson, R., Nehring, C., Otsuka, R., et al. (2023). Design and testing of a humanized porcine donor for xenotransplantation. Nature <italic>622, </italic>393. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, A.; Hurst, R. Anti-N-glycolylneuraminic acid antibodies identified in healthy human serum. Xenotransplantation 2002, 9, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, L.G. , Choe, L.H., Reardon, K.F., Dow, S.W., and Orton, E.C. (2009). Immunoproteomic identification of bovine pericardium xenoantigens.

- De Bank, P.A. , Kellam, B., Kendall, D.A., and Shakesheff, K.M. (2003). Surface engineering of living myoblasts via selective periodate oxidation. Biotech & Bioengineering 81, 800. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y. , Ramya, T.N.C., Dirksen, A., Dawson, P.E., and Paulson, J.C. (2009). High-efficiency labeling of sialylated glycoproteins on living cells. Nat Methods 6, 207. [CrossRef]

- Fransson, L.-Å. , Malmström, A., Sjöberg, I., Huckerby, T.N., 1980. Periodate oxidation and alkaline degradation of heparin-related glycans. Carbohydrate Research 80, 131–145. [CrossRef]

- Pflaum, M. , Merhej, H., Peredo, A., De, A., Dipresa, D., Wiegmann, B., Wolkers, W., Haverich, A., Korossis, S., 2020. Hypothermic preservation of endothelialized gas-exchange membranes. Artificial Organs 44, e552–e565. [CrossRef]

- Krüger-Genge, Blocki, Franke, and Jung. (2019). Vascular Endothelial Cell Biology: An Update. IJMS 20. [CrossRef]

- Tomoda, H. , Kishimoto, Y., and Lee, Y.C. Temperature Effect on Endocytosis and Exocytosis by Rabbit Alveolar Macrophages.

- Längin, M. , Mayr, T., Reichart, B., Michel, S., Buchholz, S., Guethoff, S., Dashkevich, A., Baehr, A., Egerer, S., Bauer, A., Mihalj, M., Panelli, A., Issl, L., Ying, J., Fresch, A.K., Buttgereit, I., Mokelke, M., Radan, J., Werner, F., Lutzmann, I., Steen, S., Sjöberg, T., Paskevicius, A., Qiuming, L., Sfriso, R., et al. (2018). Consistent success in life-supporting porcine cardiac xenotransplantation. Nature 564, 430. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Analysis of isolated PECs. [A] Light microscopy revealed a cobblestone-like growth pattern of the isolated cells. [B, C] Immunocytochemistry of the isolated cells using [B] an antibody against VE-Cadherin (red) or [C] the lectin IL-B4 against αGal (red); nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue).

Figure 1.

Analysis of isolated PECs. [A] Light microscopy revealed a cobblestone-like growth pattern of the isolated cells. [B, C] Immunocytochemistry of the isolated cells using [B] an antibody against VE-Cadherin (red) or [C] the lectin IL-B4 against αGal (red); nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue).

Figure 2.

Solubility of NaIO4 at 4°C in different solvents. NaIO4 was dissolved in PBS (A), EBM (B), or saline (C) at the indicated concentrations. In PBS, formation of a white precipitate was observed starting from a concentration of 2 mM NaIO4 (red arrows). n=2 .

Figure 2.

Solubility of NaIO4 at 4°C in different solvents. NaIO4 was dissolved in PBS (A), EBM (B), or saline (C) at the indicated concentrations. In PBS, formation of a white precipitate was observed starting from a concentration of 2 mM NaIO4 (red arrows). n=2 .

Figure 3.

Cell viability is dependent on oxidation temperature. [A] Survival rates of PECs oxidized with 2 mM NaIO4 for 40 minutes at 4°C or 37°C with respective controls incubated with PBS (n=3). [B-G] Exemplary pictures of a live/dead assay (green = live; red = dead) of PECs treated at 4°C [B-D], respectively at 37°C [E-G]. [C, F] NaIO4 oxidation under static conditions was compared to oxidation under dynamic conditions [D, G] Experiments were performed with cells from three different donor animals. Scale bar 1000 µm or 100 µm in [D, G].

Figure 3.

Cell viability is dependent on oxidation temperature. [A] Survival rates of PECs oxidized with 2 mM NaIO4 for 40 minutes at 4°C or 37°C with respective controls incubated with PBS (n=3). [B-G] Exemplary pictures of a live/dead assay (green = live; red = dead) of PECs treated at 4°C [B-D], respectively at 37°C [E-G]. [C, F] NaIO4 oxidation under static conditions was compared to oxidation under dynamic conditions [D, G] Experiments were performed with cells from three different donor animals. Scale bar 1000 µm or 100 µm in [D, G].

Figure 4.

Cell Survival is dependent on applied concentrations and treatment duration. [A] The cell survival rate at different concentrations of NaIO4 over time. (n=3) [B, E, H, K] Live/dead staining of PECs oxidized using 2-5 mM NaIO4 for 60, 30, 20, or 10 minutes. [C, F, I, L] IL-B4 staining of PECs treated with the indicated different concentrations of NaIO4 and duration. [D, G, J, M] Respective controls, PECs treated with PBS for the indicated periods. Scale bars show [B, E, H, K] 1000 µm or 200 µm.

Figure 4.

Cell Survival is dependent on applied concentrations and treatment duration. [A] The cell survival rate at different concentrations of NaIO4 over time. (n=3) [B, E, H, K] Live/dead staining of PECs oxidized using 2-5 mM NaIO4 for 60, 30, 20, or 10 minutes. [C, F, I, L] IL-B4 staining of PECs treated with the indicated different concentrations of NaIO4 and duration. [D, G, J, M] Respective controls, PECs treated with PBS for the indicated periods. Scale bars show [B, E, H, K] 1000 µm or 200 µm.

Figure 5.

NaIO4 oxidation under dynamic conditions. [A, E, I, M] PECs treated with PBS as controls stained with IL-B4 or human serum. [B, F] Oxidation for 60 minutes with 2 mM NaIO4 caused a similar reduction of IL-B4 staining as static conditions (blue = DAPI; red = IL-B4). [C, G] Even stronger reduction was observed using 3 mM NaIO4 for 60 minutes. [I-P] Staining of human IgG, IgA and IgM showed reduced binding of human serum antibodies to PEC oxidized for [J, N] 60 minutes with 2 mM and a further reduction with [K, O] 3 mM NaIO4 (blue= DAPI, green = anti-human IgA, IgG, IgM (Heavy & Light Chain)). [D, H, L, P] Human ECFCs served as negative controls. Experiments were performed in technical triplicates with cells from one donor animal. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Figure 5.

NaIO4 oxidation under dynamic conditions. [A, E, I, M] PECs treated with PBS as controls stained with IL-B4 or human serum. [B, F] Oxidation for 60 minutes with 2 mM NaIO4 caused a similar reduction of IL-B4 staining as static conditions (blue = DAPI; red = IL-B4). [C, G] Even stronger reduction was observed using 3 mM NaIO4 for 60 minutes. [I-P] Staining of human IgG, IgA and IgM showed reduced binding of human serum antibodies to PEC oxidized for [J, N] 60 minutes with 2 mM and a further reduction with [K, O] 3 mM NaIO4 (blue= DAPI, green = anti-human IgA, IgG, IgM (Heavy & Light Chain)). [D, H, L, P] Human ECFCs served as negative controls. Experiments were performed in technical triplicates with cells from one donor animal. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Figure 6.

αGal turnover. PECs stained with IL-B4 (red) directly after oxidation [A], corresponding untreated control [B]. PECs cultivated for 24 hours after oxidation and stained with IL-B4 [C], respective unprocessed control [D]. Extent of areas positively detected by IL-B4 staining increases on levels of not oxidized tissues after 24 hours of further incubation. Experiments were performed as biological duplicates with cells from two independent donor animals. Scale bar: 200 µm.

Figure 6.

αGal turnover. PECs stained with IL-B4 (red) directly after oxidation [A], corresponding untreated control [B]. PECs cultivated for 24 hours after oxidation and stained with IL-B4 [C], respective unprocessed control [D]. Extent of areas positively detected by IL-B4 staining increases on levels of not oxidized tissues after 24 hours of further incubation. Experiments were performed as biological duplicates with cells from two independent donor animals. Scale bar: 200 µm.

Figure 7.

NaIO4 penetrates into native aortic tissue. Cross-sections of treated and untreated controls were stained with IL-B4. Oxidation with 2 mM NaIO4 for 40 minutes at 4°C led to a distinct reduction of IL-B4 positivity (red) within the intima layer and parts of the media layer. Cellular nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). This experiment was performed using tissue from only one animal. Scale bar: 200 µm.

Figure 7.

NaIO4 penetrates into native aortic tissue. Cross-sections of treated and untreated controls were stained with IL-B4. Oxidation with 2 mM NaIO4 for 40 minutes at 4°C led to a distinct reduction of IL-B4 positivity (red) within the intima layer and parts of the media layer. Cellular nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). This experiment was performed using tissue from only one animal. Scale bar: 200 µm.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).