Submitted:

03 June 2024

Posted:

05 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Genotype Affects Synaptic Facilitation in VH of Female Rats

2.2. STSP Differs Between DH and VH from Male and Female Rats of Both Genotypes

2.3. Expression of Synaptotagmin-1 in WT and KO Rat Hippocampus

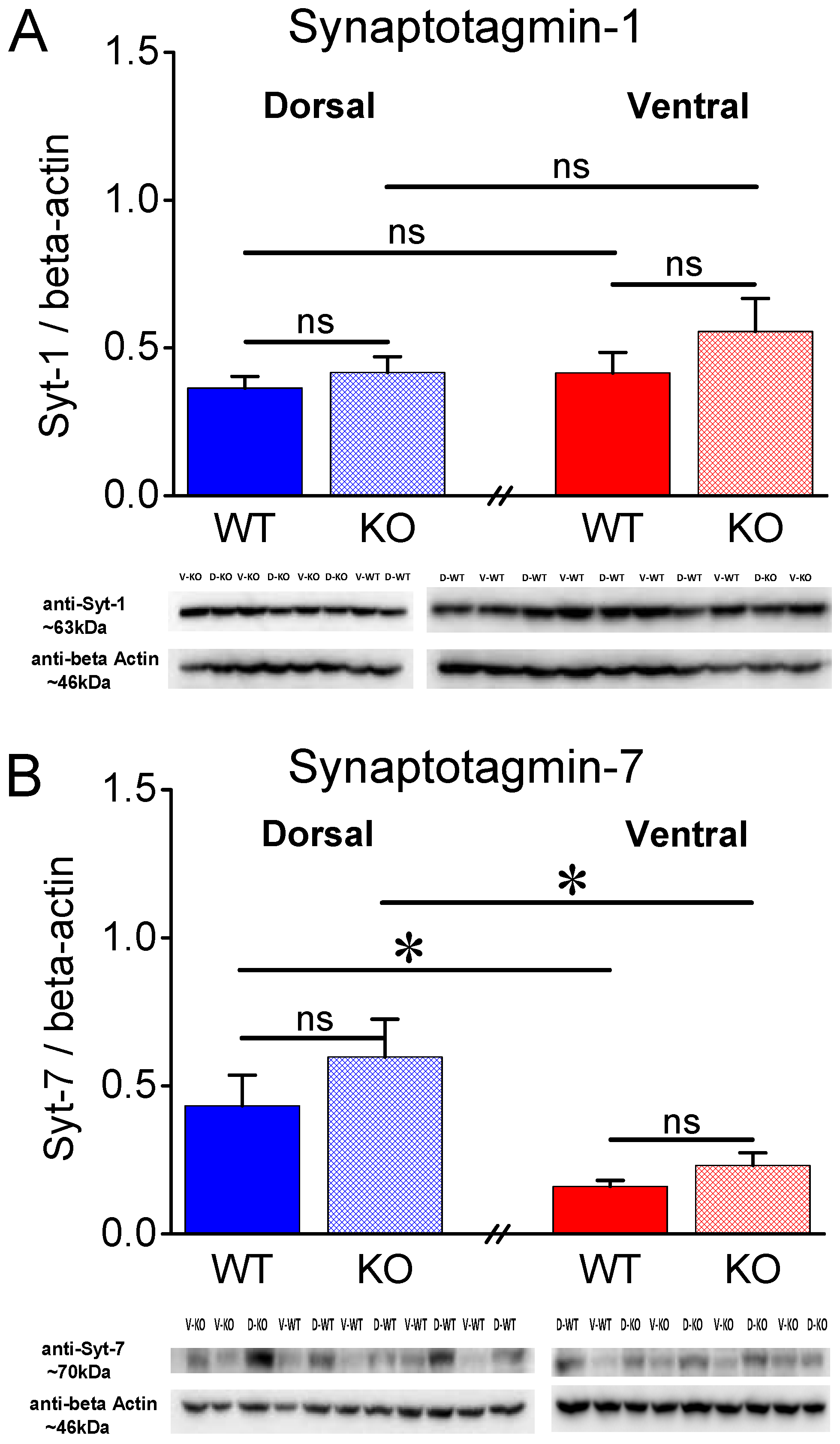

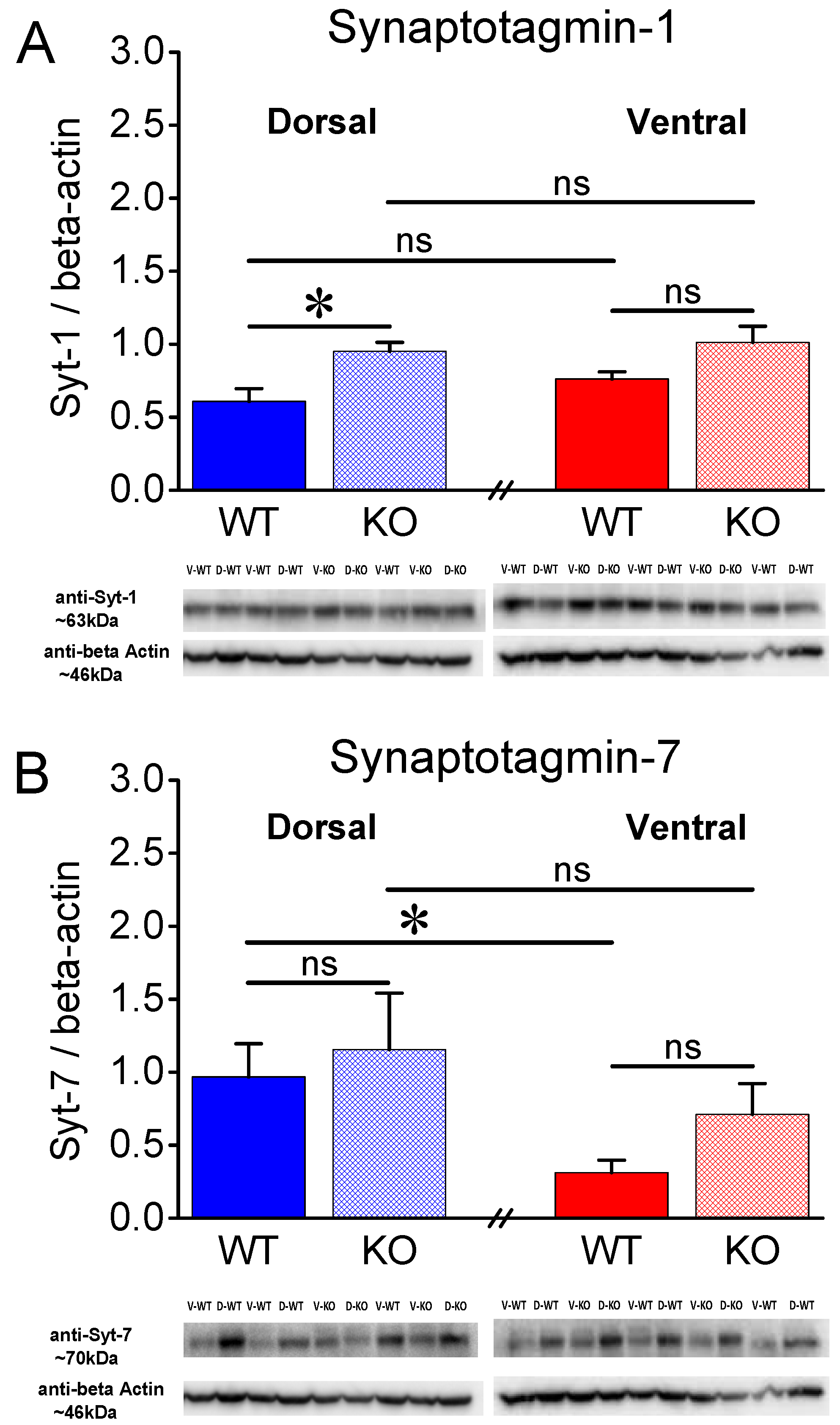

2.4. Higher Levels of Synaptotagmin-7 in DH vs VH

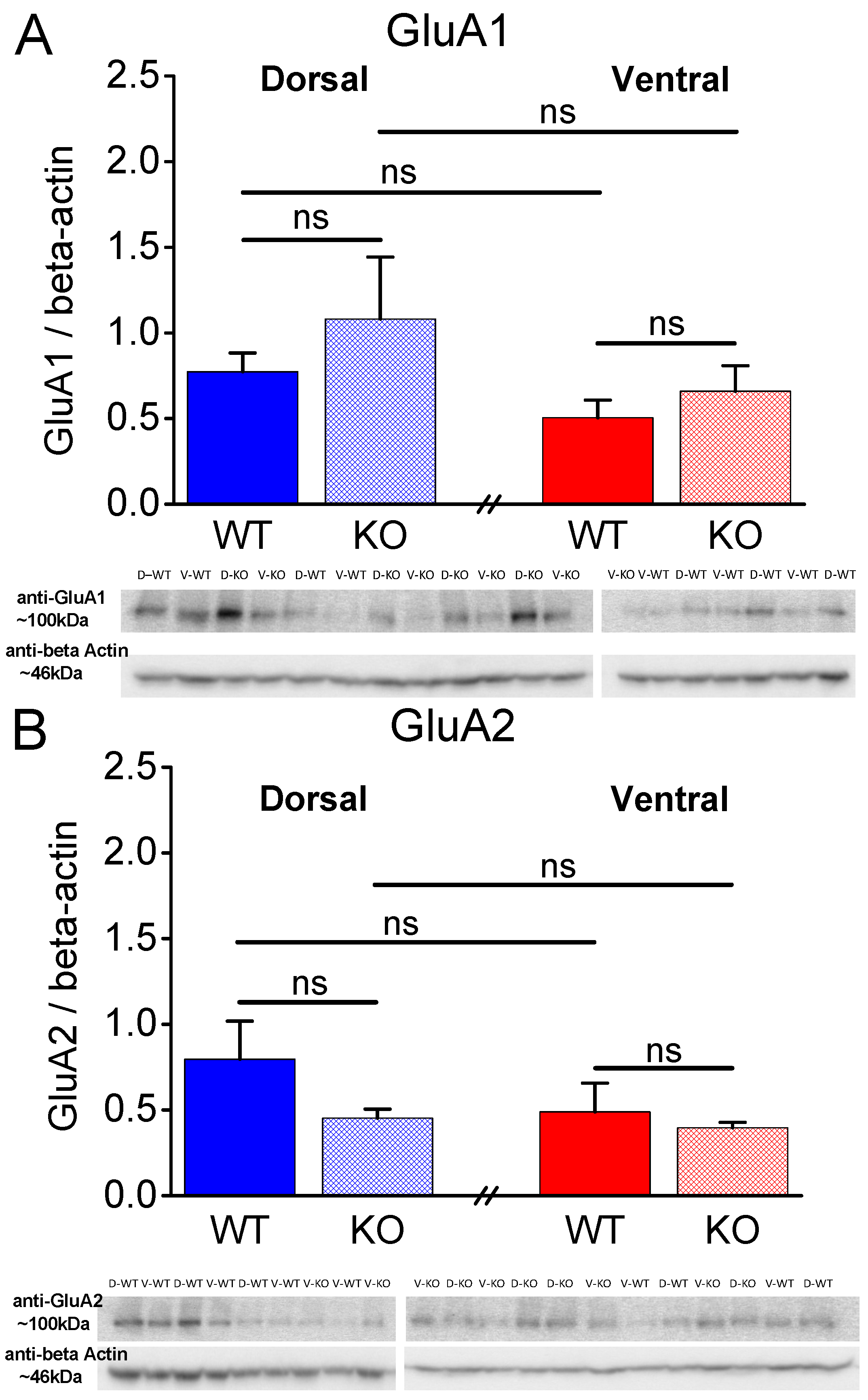

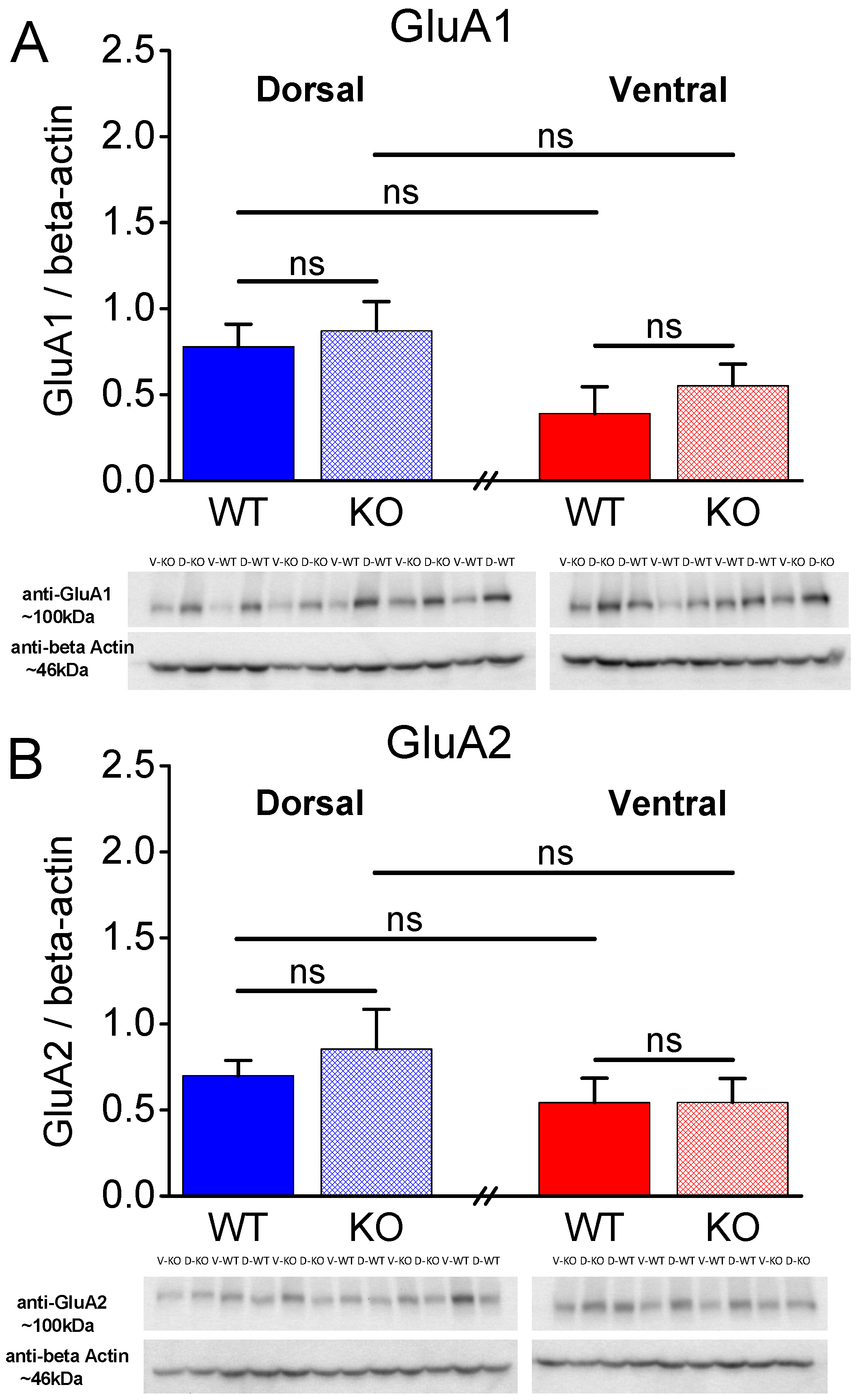

2.5. Similar Expression of AMPA Receptor Subunits GluA1 and GluA2 in WT and KO Rats

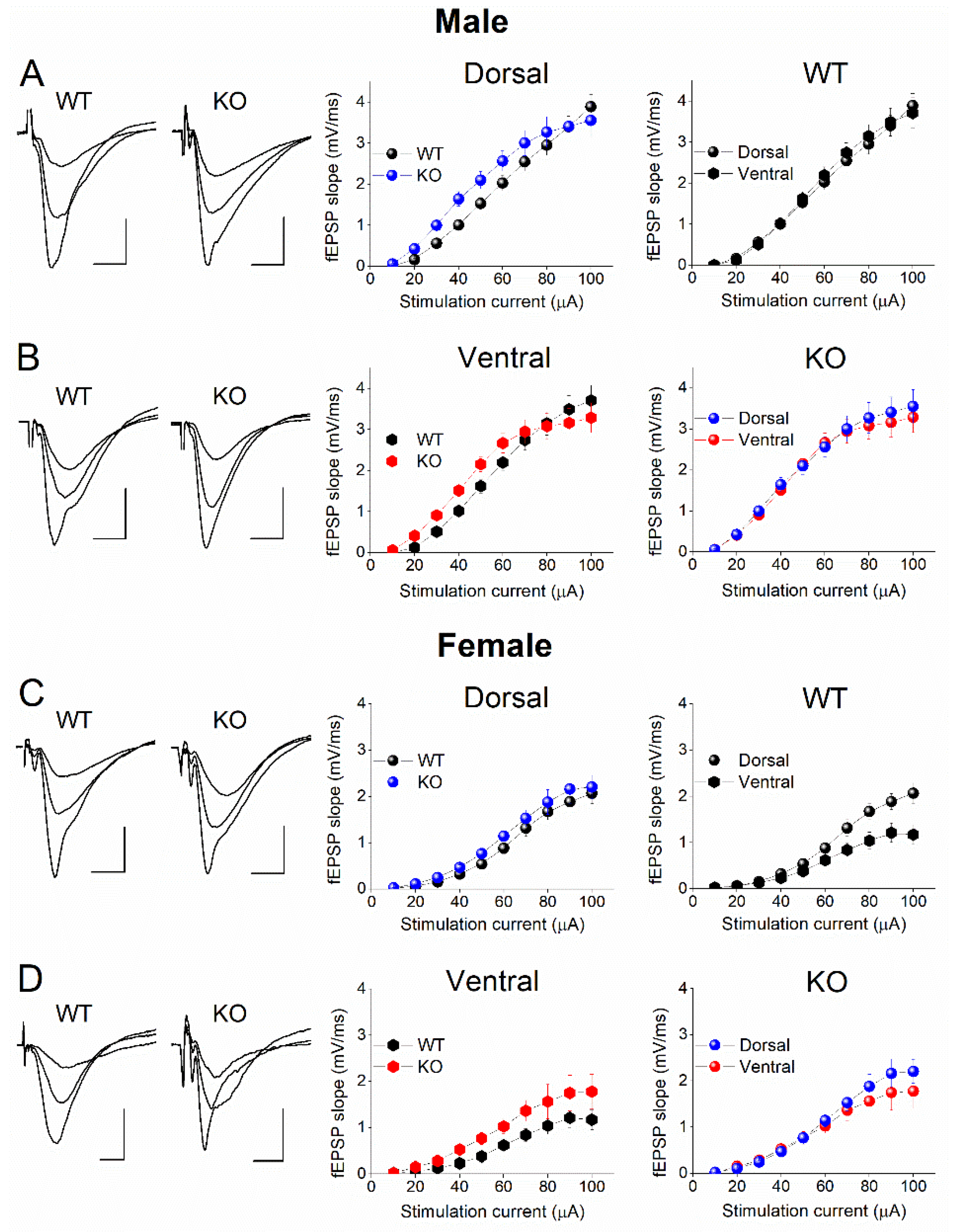

2.6. Similar Excitatory Synaptic Transmission in DH and VH of WT and KO Male Rats

2.7. Increased Excitatory Synaptic Transmission in DH vs VH of WT Female Rats

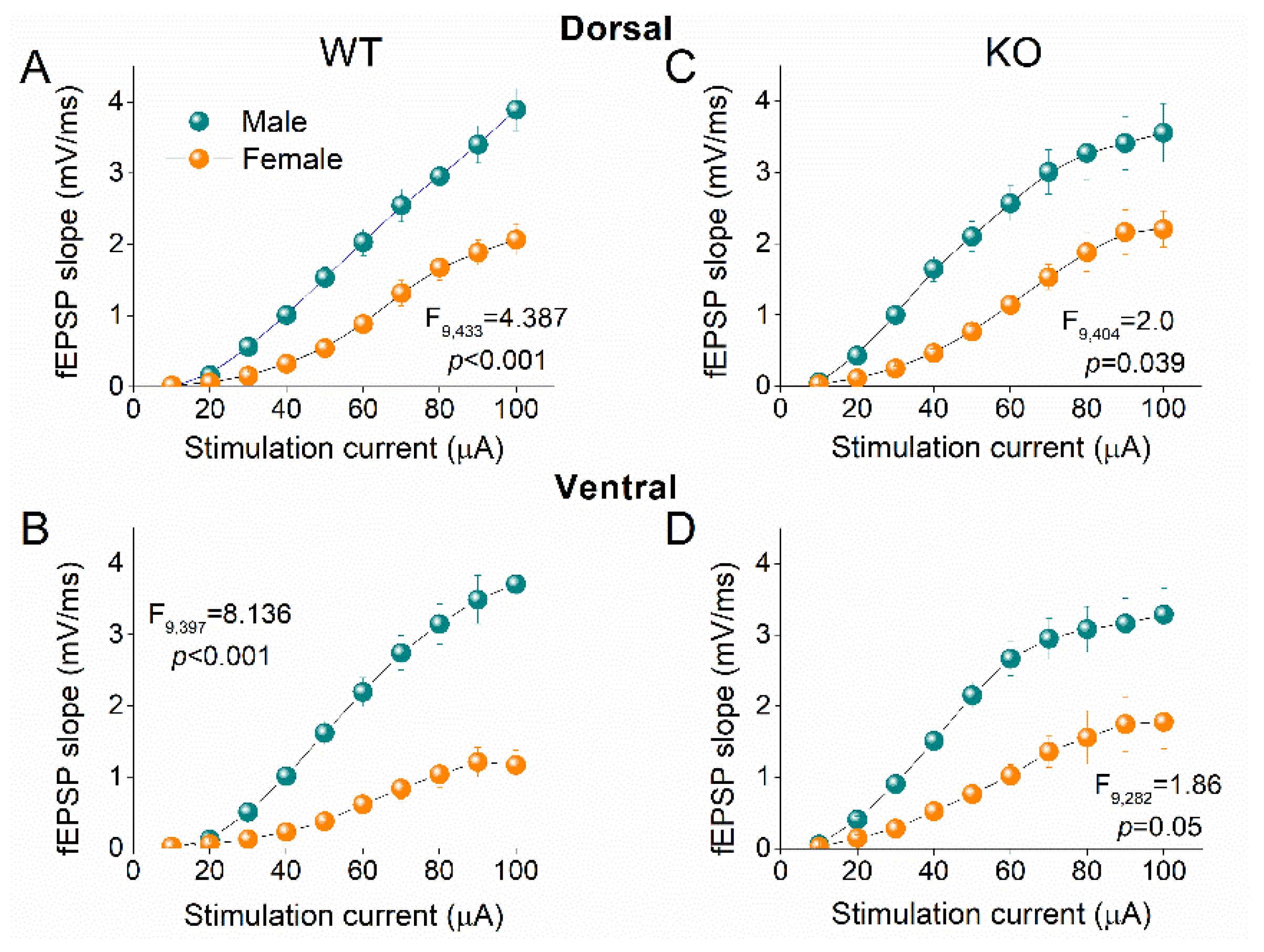

2.8. Higher Excitatory Synaptic Transmission in Male vs Female Hippocampus

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of FXS on STSP and Synaptotagmins

3.2. Dorsoventral Difference in STSP and a Possible Role of Synaptotagmin-7

3.3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Slice Preparation

4.3. Electrophysiology

4.4. Immunoblotting

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Hagerman, R.J.; Berry-Kravis, E.; Hazlett, H.C.; Bailey, D.B., Jr.; Moine, H.; Kooy, R.F.; Tassone, F.; Gantois, I.; Sonenberg, N.; Mandel, J.L.; et al. Fragile X syndrome. Nature reviews. Disease primers 2017, 3, 17065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, S.A.; Lachiewicz, A.; Barbouth, D.; Blitz, R.K.; Delahunty, C.; McBrien, D.; Visootsak, J.; Berry-Kravis, E. Fragile X syndrome: a review of associated medical problems. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, D.B., Jr.; Mesibov, G.B.; Hatton, D.D.; Clark, R.D.; Roberts, J.E.; Mayhew, L. Autistic behavior in young boys with fragile X syndrome. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 1998, 28, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagerman, R.J.; Jackson, A.W., 3rd; Levitas, A.; Rimland, B.; Braden, M. An analysis of autism in fifty males with the fragile X syndrome. American journal of medical genetics 1986, 23, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, W.E.; Kidd, S.A.; Andrews, H.F.; Budimirovic, D.B.; Esler, A.; Haas-Givler, B.; Stackhouse, T.; Riley, C.; Peacock, G.; Sherman, S.L.; et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder in Fragile X Syndrome: Cooccurring Conditions and Current Treatment. Pediatrics 2017, 139, S194–s206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagerman, R.J. Lessons from fragile X regarding neurobiology, autism, and neurodegeneration. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP 2006, 27, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkerk, A.J.; Pieretti, M.; Sutcliffe, J.S.; Fu, Y.H.; Kuhl, D.P.; Pizzuti, A.; Reiner, O.; Richards, S.; Victoria, M.F.; Zhang, F.P.; et al. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell 1991, 65, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassell, G.J.; Warren, S.T. Fragile X syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron 2008, 60, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rylaarsdam, L.; Guemez-Gamboa, A. Genetic Causes and Modifiers of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 2019, 13, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, S.; Halder, S.K.; Hampson, D.R.J.B.r. Expression of fragile X mental retardation protein in neurons and glia of the developing and adult mouse brain. 2015, 1596, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zorio, D.A.; Jackson, C.M.; Liu, Y.; Rubel, E.W.; Wang, Y.J.J.o.C.N. Cellular distribution of the fragile X mental retardation protein in the mouse brain. 2017, 525, 818–849. [Google Scholar]

- Beckel-Mitchener, A.; Greenough, W.T. Correlates across the structural, functional, and molecular phenotypes of fragile X syndrome. Mental retardation and developmental disabilities research reviews 2004, 10, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, M.F.; Dölen, G.; Osterweil, E.; Nagarajan, N. Fragile X: translation in action. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 2008, 33, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyke, W.; Velinov, M. FMR1 and Autism, an Intriguing Connection Revisited. Genes 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.D.; Zhao, X. The molecular biology of FMRP: new insights into fragile X syndrome. Nat Rev Neurosci 2021, 22, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.R.; Kronengold, J.; Gazula, V.R.; Chen, Y.; Strumbos, J.G.; Sigworth, F.J.; Navaratnam, D.; Kaczmarek, L.K. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls gating of the sodium-activated potassium channel Slack. Nature neuroscience 2010, 13, 819–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, P.Y.; Rotman, Z.; Blundon, J.A.; Cho, Y.; Cui, J.; Cavalli, V.; Zakharenko, S.S.; Klyachko, V.A. FMRP regulates neurotransmitter release and synaptic information transmission by modulating action potential duration via BK channels. Neuron 2013, 77, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sela-Donenfeld, D.; Wang, Y. Axonal and presynaptic FMRP: Localization, signal, and functional implications. Hearing research 2023, 430, 108720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.Y.; Sojka, D.; Klyachko, V.A. Abnormal presynaptic short-term plasticity and information processing in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2011, 31, 10971–10982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koga, K.; Liu, M.G.; Qiu, S.; Song, Q.; O’Den, G.; Chen, T.; Zhuo, M. Impaired presynaptic long-term potentiation in the anterior cingulate cortex of Fmr1 knock-out mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2015, 35, 2033–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemmer, P.; Meredith, R.M.; Holmgren, C.D.; Klychnikov, O.I.; Stahl-Zeng, J.; Loos, M.; van der Schors, R.C.; Wortel, J.; de Wit, H.; Spijker, S.; et al. Proteomics, ultrastructure, and physiology of hippocampal synapses in a fragile X syndrome mouse model reveal presynaptic phenotype. The Journal of biological chemistry 2011, 286, 25495–25504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monday, H.R.; Kharod, S.C.; Yoon, Y.J.; Singer, R.H.; Castillo, P.E. Presynaptic FMRP and local protein synthesis support structural and functional plasticity of glutamatergic axon terminals. Neuron 2022, 110, 2588–2606 e2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, J.C.; Van Driesche, S.J.; Zhang, C.; Hung, K.Y.; Mele, A.; Fraser, C.E.; Stone, E.F.; Chen, C.; Fak, J.J.; Chi, S.W.; et al. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell 2011, 146, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhakar, A.L.; Dölen, G.; Bear, M.F. The pathophysiology of fragile X (and what it teaches us about synapses). Annual review of neuroscience 2012, 35, 417–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, R.G. NMDA receptors and memory encoding. Neuropharmacology 2013, 74, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Lu, Y.M.; Agopyan, N.; Roder, J. Gene targeting reveals a role for the glutamate receptors mGluR5 and GluR2 in learning and memory. Physiology & behavior 2001, 73, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, M.R.; Bray, S.M.; Warren, S.T. Molecular mechanisms of fragile X syndrome: a twenty-year perspective. Annu Rev Pathol 2012, 7, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosyreva, E.D.; Huber, K.M. Metabotropic receptor-dependent long-term depression persists in the absence of protein synthesis in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Journal of neurophysiology 2006, 95, 3291–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meredith, R.M.; Holmgren, C.D.; Weidum, M.; Burnashev, N.; Mansvelder, H.D.J.N. Increased threshold for spike-timing-dependent plasticity is caused by unreliable calcium signaling in mice lacking fragile X gene FMR1. 2007, 54, 627–638. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, H.G.S.; Lassalle, O.; Brown, J.T.; Manzoni, O.J. Age-Dependent Long-Term Potentiation Deficits in the Prefrontal Cortex of the Fmr1 Knockout Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. Cereb Cortex 2016, 26, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatton, D.D.; Buckley, E.; Lachiewicz, A.; Roberts, J. Ocular status of boys with fragile X syndrome: a prospective study. J AAPOS 1998, 2, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, O.; Kowal, T.; Banet-Levi, Y.; Gabis, L.V. Executive Function and Working Memory Deficits in Females with Fragile X Premutation. Life (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraju, P.; Yu, J.; Eddins, D.; Mellado-Lagarde, M.M.; Earls, L.R.; Westmoreland, J.J.; Quarato, G.; Green, D.R.; Zakharenko, S.S. Haploinsufficiency of the 22q11.2 microdeletion gene Mrpl40 disrupts short-term synaptic plasticity and working memory through dysregulation of mitochondrial calcium. Molecular psychiatry 2017, 22, 1313–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pals, M.; Stewart, T.C.; Akyürek, E.G.; Borst, J.P. A functional spiking-neuron model of activity-silent working memory in humans based on calcium-mediated short-term synaptic plasticity. PLoS computational biology 2020, 16, e1007936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, R.S.; Regehr, W.G. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annual review of physiology 2002, 64, 355–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, S.B.; Akins, M.R.; Schwob, J.E.; Fallon, J.R. The FXG: a presynaptic fragile X granule expressed in a subset of developing brain circuits. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2009, 29, 1514–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Gutekunst, C.A.; Eberhart, D.E.; Yi, H.; Warren, S.T.; Hersch, S.M. Fragile X mental retardation protein: nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and association with somatodendritic ribosomes. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 1997, 17, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, J.E.; Madison, D.V. Presynaptic FMR1 genotype influences the degree of synaptic connectivity in a mosaic mouse model of fragile X syndrome. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2007, 27, 4014–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferron, L.; Nieto-Rostro, M.; Cassidy, J.S.; Dolphin, A.C. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls synaptic vesicle exocytosis by modulating N-type calcium channel density. Nature communications 2014, 5, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnycastle, K.; Kind, P.C.; Cousin, M.A. FMRP Sustains Presynaptic Function via Control of Activity-Dependent Bulk Endocytosis. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2022, 42, 1618–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catterall, W.A.; Leal, K.; Nanou, E. Calcium channels and short-term synaptic plasticity. The Journal of biological chemistry 2013, 288, 10742–10749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Südhof, T.C.; Rothman, J.E. Membrane fusion: grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science 2009, 323, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfes, A.C.; Dean, C. The diversity of synaptotagmin isoforms. Current opinion in neurobiology 2020, 63, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volynski, K.E.; Krishnakumar, S.S. Synergistic control of neurotransmitter release by different members of the synaptotagmin family. Current opinion in neurobiology 2018, 51, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacaj, T.; Wu, D.; Yang, X.; Morishita, W.; Zhou, P.; Xu, W.; Malenka, R.C.; Südhof, T.C. Synaptotagmin-1 and synaptotagmin-7 trigger synchronous and asynchronous phases of neurotransmitter release. Neuron 2013, 80, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maximov, A.; Südhof, T.C. Autonomous function of synaptotagmin 1 in triggering synchronous release independent of asynchronous release. Neuron 2005, 48, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Satterfield, R.; Young, S.M., Jr.; Jonas, P. Triple Function of Synaptotagmin 7 Ensures Efficiency of High-Frequency Transmission at Central GABAergic Synapses. Cell reports 2017, 21, 2082–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalla, A.; Tucker, W.C.; Chapman, E.R. Synaptotagmin isoforms couple distinct ranges of Ca2+, Ba2+, and Sr2+ concentration to SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Molecular biology of the cell 2005, 16, 4755–4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, D.S.; Coffman, M.D.; Falke, J.J.; Knight, J.D. Hydrophobic contributions to the membrane docking of synaptotagmin 7 C2A domain: mechanistic contrast between isoforms 1 and 7. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 7654–7664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Trussell, L.O. Inhibitory transmission mediated by asynchronous transmitter release. Neuron 2000, 26, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackman, S.L.; Turecek, J.; Belinsky, J.E.; Regehr, W.G. The calcium sensor synaptotagmin 7 is required for synaptic facilitation. Nature 2016, 529, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, T.; Sakurai, A.; Littleton, J.T.; Yoshihara, M. Synaptotagmin 7 switches short-term synaptic plasticity from depression to facilitation by suppressing synaptic transmission. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyrer, C.; Turecek, J.; Harrison, B.; Regehr, W.G. Introduction of synaptotagmin 7 promotes facilitation at the climbing fiber to Purkinje cell synapse. Cell reports 2021, 36, 109719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Kulasiri, D.; Liang, J. A mathematical model of synaptotagmin 7 revealing functional importance of short-term synaptic plasticity. Neural regeneration research 2019, 14, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djillani, A.; Bazinet, J.; Catterall, W.A. Synaptotagmin-7 Enhances Facilitation of Ca(v)2.1 Calcium Channels. eNeuro 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhi, K.; Meng, X. Effects and Mechanisms of Synaptotagmin-7 in the Hippocampus on Cognitive Impairment in Aging Mice. Molecular neurobiology 2021, 58, 5756–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Wang, Q.W.; Liu, Y.N.; Marchetto, M.C.; Linker, S.; Lu, S.Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Guo, C.; Xing, Z.; et al. Synaptotagmin-7 is a key factor for bipolar-like behavioral abnormalities in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020, 117, 4392–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, S.; Han, W.; Butz, S.; Liu, X.; Fernández-Chacón, R.; Lao, Y.; Südhof, T.C. Synaptotagmin VII as a plasma membrane Ca(2+) sensor in exocytosis. Neuron 2001, 30, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hou, L.; Klann, E.; Nelson, D.L. Altered hippocampal synaptic plasticity in the FMR1 gene family knockout mouse models. Journal of neurophysiology 2009, 101, 2572–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S.; Peng, C.Z.; Cai, W.J.; Xia, J.; Jin, D.; Dai, Y.; Luo, X.G.; Klyachko, V.A.; Deng, P.Y. Activity-dependent regulation of release probability at excitatory hippocampal synapses: a crucial role of fragile X mental retardation protein in neurotransmission. The European journal of neuroscience 2014, 39, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlmanns, M.; Valero-Aracama, M.J.; Dahlmanns, J.K.; Zheng, F.; Alzheimer, C. Tonic activin signaling shapes cellular and synaptic properties of CA1 neurons mainly in dorsal hippocampus. iScience 2023, 26, 108001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tidball, P.; Burn, H.V.; Teh, K.L.; Volianskis, A.; Collingridge, G.L.; Fitzjohn, S.M. Differential ability of the dorsal and ventral rat hippocampus to exhibit group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent synaptic and intrinsic plasticity. Brain and neuroscience advances 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milior, G.; Castro, M.A.; Sciarria, L.P.; Garofalo, S.; Branchi, I.; Ragozzino, D.; Limatola, C.; Maggi, L. Electrophysiological Properties of CA1 Pyramidal Neurons along the Longitudinal Axis of the Mouse Hippocampus. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 38242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiec, W.E.; Jami, S.A.; Guglietta, R.; Chen, P.B.; O’Dell, T.J. Differential Regulation of NMDA Receptor-Mediated Transmission by SK Channels Underlies Dorsal-Ventral Differences in Dynamics of Schaffer Collateral Synaptic Function. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2017, 37, 1950–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovyk, V.; Manahan-Vaughan, D. Less means more: The magnitude of synaptic plasticity along the hippocampal dorso-ventral axis is inversely related to the expression levels of plasticity-related neurotransmitter receptors. Hippocampus 2018, 28, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruki, K.; Izaki, Y.; Nomura, M.; Yamauchi, T. Differences in paired-pulse facilitation and long-term potentiation between dorsal and ventral CA1 regions in anesthetized rats. Hippocampus 2001, 11, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodoropoulos, C.; Kostopoulos, G. Dorsal-ventral differentiation of short-term synaptic plasticity in rat CA1 hippocampal region. Neuroscience letters 2000, 286, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papatheodoropoulos, C. Striking differences in synaptic facilitation along the dorsoventral axis of the hippocampus. Neuroscience 2015, 301, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaleonidopoulos, V.; Trompoukis, G.; Koutsoumpa, A.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. A gradient of frequency-dependent synaptic properties along the longitudinal hippocampal axis. BMC neuroscience 2017, 18, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoumpa, A.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Short-term dynamics of input and output of CA1 network greatly differ between the dorsal and ventral rat hippocampus. BMC neuroscience 2019, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoumpa, A.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Frequency-dependent layer-specific differences in short-term synaptic plasticity in the dorsal and ventral CA1 hippocampal field. Synapse 2021, e22199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samara, M.; Oikonomou, G.D.; Trompoukis, G.; Madarou, G.; Adamopoulou, M.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Septotemporal variation in modulation of synaptic transmission, paired-pulse ratio and frequency facilitation/depression by adenosine and GABA(B) receptors in the rat hippocampus. Brain and neuroscience advances 2022, 6, 23982128221106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompoukis, G.; Tsotsokou, G.; Koutsoumpa, A.; Tsolaki, M.; Vryoni, G.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Age-dependent modulation of short-term neuronal dynamics in the dorsal and ventral rat hippocampus. The International journal of developmental biology 2022, 66, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, B.A.; Witter, M.P.; Lein, E.S.; Moser, E.I. Functional organization of the hippocampal longitudinal axis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2014, 15, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontiadis, L.J.; Trompoukis, G.; Felemegkas, P.; Tsotsokou, G.; Miliou, A.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Increased Inhibition May Contribute to Maintaining Normal Network Function in the Ventral Hippocampus of a Fmr1-Targeted Transgenic Rat Model of Fragile X Syndrome. Brain sciences 2023, 13, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontiadis, L.J.; Trompoukis, G.; Tsotsokou, G.; Miliou, A.; Felemegkas, P.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Rescue of sharp wave-ripples and prevention of network hyperexcitability in the ventral but not the dorsal hippocampus of a rat model of fragile X syndrome. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, A.; Schiavi, S.; La Rosa, P.; Rossi-Espagnet, M.C.; Petrillo, S.; Bottino, F.; Tagliente, E.; Longo, D.; Lupi, E.; Casula, L.; et al. Sex Differences in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Diagnostic, Neurobiological, and Behavioral Features. Frontiers in psychiatry 2022, 13, 889636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werling, D.M.; Geschwind, D.H. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. Current opinion in neurology 2013, 26, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderoni, S. Sex/gender differences in children with autism spectrum disorder: A brief overview on epidemiology, symptom profile, and neuroanatomy. Journal of neuroscience research 2023, 101, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.J.; Gonzales, E.L.; Mabunga, D.F.N.; Valencia, S.T.; Kim, D.G.; Kim, Y.; Adil, K.J.L.; Shin, D.; Park, D.; Shin, C.Y. Sex-specific Behavioral Features of Rodent Models of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Experimental neurobiology 2018, 27, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsoumpa, A.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Frequency-dependent layer-specific differences in short-term synaptic plasticity in the dorsal and ventral CA1 hippocampal field. Synapse 2021, 75, e22199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regehr, W.G. Short-term presynaptic plasticity. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2012, 4, a005702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvaros, S.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Theta burst stimulation-induced LTP: Differences and similarities between the dorsal and ventral CA1 hippocampal synapses. Hippocampus 2016, 26, 1542–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaleonidopoulos, V.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. beta-adrenergic receptors reduce the threshold for induction and stabilization of LTP and enhance its magnitude via multiple mechanisms in the ventral but not the dorsal hippocampus. Neurobiology of learning and memory 2018, 151, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenney, J.; Manahan-Vaughan, D. NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in dorsal and intermediate hippocampus exhibits distinct frequency-dependent profiles. Neuropharmacology 2013, 74, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.D.; Jones, L.S.; Wilson, M.A. Sex differences in hippocampal slice excitability: role of testosterone. Neuroscience 2002, 109, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monfort, P.; Gomez-Gimenez, B.; Llansola, M.; Felipo, V. Gender differences in spatial learning, synaptic activity, and long-term potentiation in the hippocampus in rats: molecular mechanisms. ACS chemical neuroscience 2015, 6, 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlow, E.G.; Till, S.M.; Russell, T.A.; Wijetunge, L.S.; Kind, P.; Contractor, A.J.N. Critical period plasticity is disrupted in the barrel cortex of FMR1 knockout mice. 2010, 65, 385–398. [Google Scholar]

- Galvez, R.; Greenough, W.T.J.A.j.o.m.g.P.A. Sequence of abnormal dendritic spine development in primary somatosensory cortex of a mouse model of the fragile X mental retardation syndrome. 2005, 135, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Nimchinsky, E.J.A.d.o.d.s.i.F.k.-o.m.J.N. Oberlander AM, and Svoboda K. 2001, 21, 5139–5146. [Google Scholar]

- Berry-Kravis, E.; Filipink, R.A.; Frye, R.E.; Golla, S.; Morris, S.M.; Andrews, H.; Choo, T.H.; Kaufmann, W.E. Seizures in Fragile X Syndrome: Associations and Longitudinal Analysis of a Large Clinic-Based Cohort. Frontiers in pediatrics 2021, 9, 736255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabaratnam, M.; Vroegop, P.G.; Gangadharan, S.K. Epilepsy and EEG findings in 18 males with fragile X syndrome. Seizure 2001, 10, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, D.D.; Spencer, S.S.; Mattson, R.H.; Williamson, P.D.; Novelly, R.A. Access to the posterior medial temporal lobe structures in the surgical treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurosurgery 1984, 15, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babb, T.L.; Brown, W.J.; Pretorius, J.; Davenport, C.; Lieb, J.P.; Crandall, P.H. Temporal lobe volumetric cell densities in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 1984, 25, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bódi, V.; Májer, T.; Kelemen, V.; Világi, I.; Szűcs, A.; Varró, P. Alterations of the Hippocampal Networks in Valproic Acid-Induced Rat Autism Model. Frontiers in neural circuits 2022, 16, 772792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, W.; Gray, C.M. Visual feature integration and the temporal correlation hypothesis. Annual review of neuroscience 1995, 18, 555–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, J.; Legius, E.; Borghgraef, M.; Fryns, J.P. A distinct neurocognitive phenotype in female fragile-X premutation carriers assessed with visual attention tasks. Am J Med Genet A 2003, 116a, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, J.E.; Schmitt, L.M.; De Stefano, L.A.; Pedapati, E.V.; Erickson, C.A.; Sweeney, J.A.; Ethridge, L.E. Neuropsychiatric feature-based subgrouping reveals neural sensory processing spectrum in female FMR1 premutation carriers: A pilot study. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience 2023, 17, 898215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanks, N.F.; Savas, J.N.; Maruo, T.; Cais, O.; Hirao, A.; Oe, S.; Ghosh, A.; Noda, Y.; Greger, I.H.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; et al. Differences in AMPA and kainate receptor interactomes facilitate identification of AMPA receptor auxiliary subunit GSG1L. Cell reports 2012, 1, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrunz, L.E.; Stevens, C.F. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron 1997, 18, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papatheodoropoulos, C. Electrophysiological evidence for long-axis intrinsic diversification of the hippocampus. Frontiers in Bioscience (Landmark Ed.). 2018, 23, 109–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trompoukis, G.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Dorsal-Ventral Differences in Modulation of Synaptic Transmission in the Hippocampus. Frontiers in synaptic neuroscience 2020, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, B.; Miledi, R. The role of calcium in neuromuscular facilitation. The Journal of physiology 1968, 195, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geppert, M.; Goda, Y.; Hammer, R.E.; Li, C.; Rosahl, T.W.; Stevens, C.F.; Südhof, T.C. Synaptotagmin I: a major Ca2+ sensor for transmitter release at a central synapse. Cell 1994, 79, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, N.; Zorn, A.M.; Crease, D.J.; Gurdon, J.B. Activin has direct long-range signalling activity and can form a concentration gradient by diffusion. Current biology : CB 1997, 7, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).