This review brings to light the significant yet often overlooked role of dermal sheath cells (DSCs) in wound healing. It emphasizes their multifunctional roles in inflammation modulation, proliferation aid, and ECM remodeling, and illuminates DSCs’ paracrine effects and their involvement in fibrosis, offering a new perspective on skin repair processes.

Introduction

Wound healing in medical practice is challenging, requiring a multifaceted approach that includes both the body’s natural healing processes and advanced therapies like cell transplantation and bioengineered skin. Overcoming complications such as infection, inadequate blood supply, and excessive inflammation is critical to prevent delayed healing, chronic wounds, or excessive scarring. The orchestration of key biological processes, such as cell migration, proliferation, and the secretion of the extracellular matrix (ECM) by skin cells, is essential for successful wound healing.

Dermal fibroblasts (DFs) have been widely studied in the mechanism of wound repair. They contain multiple subtypes stored mainly in the papillary and reticular dermis, exhibiting functional heterogeneity and undergoing significant dynamic changes during skin wound healing [

1,

2,

3]. Currently, Dermal sheath cells (DSCs) are considered to be one of the subgroups of DFs [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The dermal sheath (DS) is a vital component of the hair follicle mesenchyme, situated at the outermost layer of the hair follicle and separated from epidermal cells by a basement membrane [

8,

9]. DSCs are known for their roles in hair follicle formation and cycling, acting as resident stem cells within the skin [

5,

10,

11]. These cells have shown potential in modulating key processes in wound healing, such as inflammation, cell proliferation, and ECM remodeling.

Exploring the intricate roles of DSCs and their potential to modulate wound healing processes promises to advance strategies in wound care and regenerative medicine. By understanding how DSCs contribute to these processes, we can develop new therapeutic approaches to improve healing outcomes, particularly in distinguishing between hairy and non-hairy skin sites.

Background

Wound healing is typically divided into three overlapping phases: inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [

12,

13]. During the inflammation phase, hemostasis is achieved through the activation of platelets, which form a clot to prevent excessive bleeding [

14]. This clot provides a provisional matrix for subsequent cell migration and tissue repair [

15,

16]. Meanwhile, immune cells are recruited to the wound site to clear debris, neutralize pathogens, and release cytokines and growth factors that initiate the healing process [

17,

18,

19,

20]. The proliferation stage is marked by the migration and proliferation of diverse cell types, notably fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and keratinocytes [

21]. Fibroblasts play a crucial role in producing and remodeling the ECM, which provides structural support to the healing tissue [

22]. Endothelial cells contribute to angiogenesis to ensure sufficient blood supply to the affected area [

23]. Keratinocytes migrate and proliferate to reestablish the epidermal barrier [

24,

25]. This stage also involves the breakdown of the provisional ECM formed during hemostasis, mediated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and proteinases secreted by fibroblasts, while concurrently, fibroblasts synthesize ECM proteins, contributing to the formation of granulation tissue [

26]. In the final stage, remodeling, the newly formed ECM undergoes maturation and reorganization, enhancing the tensile strength of the healing tissue. Collagen fibers align along tension lines, and excessive scar tissue undergoes gradual remodeling, transitioning into a more organized and functional structure [

27].

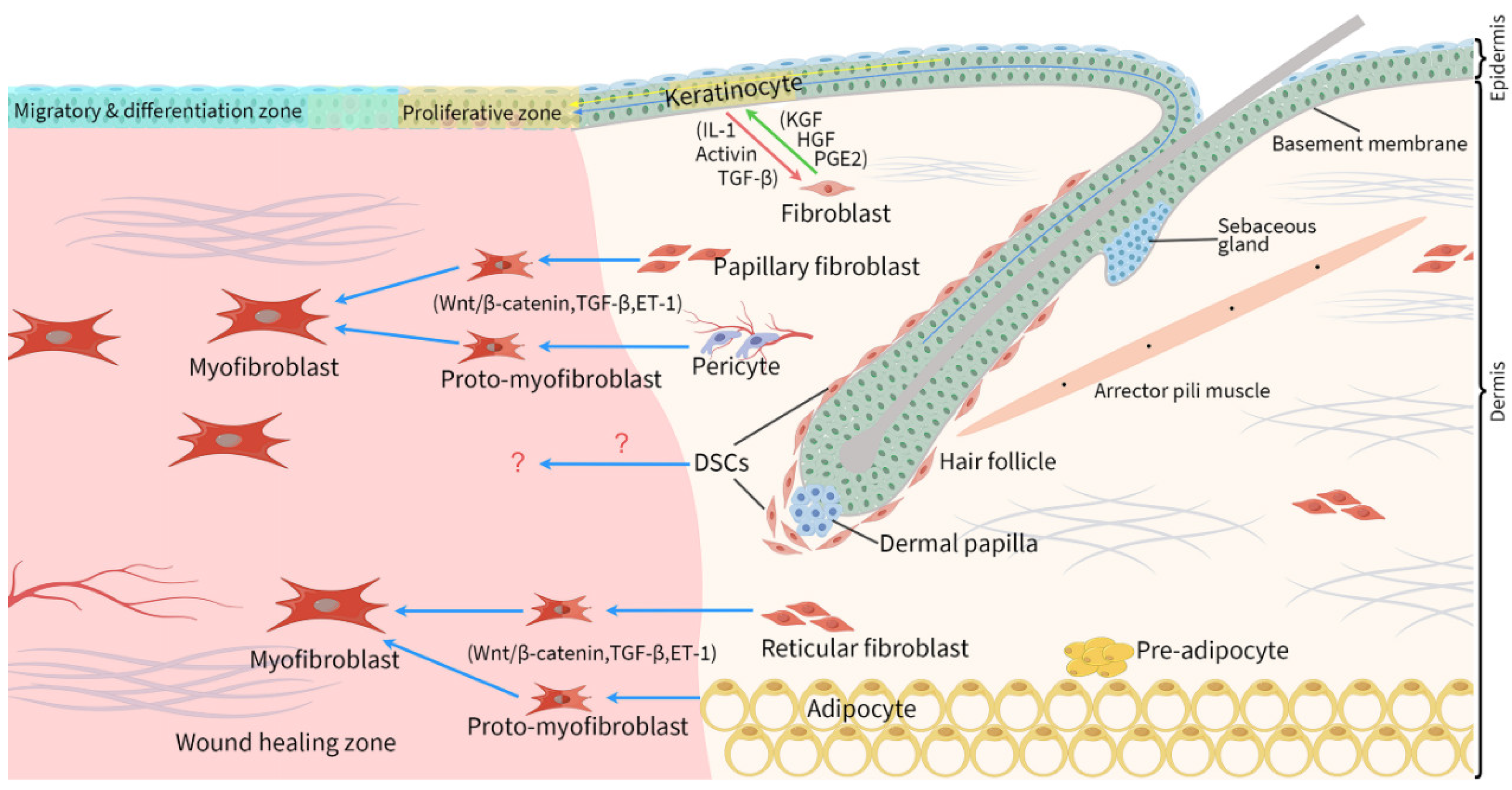

Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions are pivotal in the wound healing process. As depicted in

Figure 1, skin epithelial and mesenchymal cells exhibit notable heterogeneity and plasticity. Post injury, an inflammatory response dominates the very beginning of the healing process. Under the sustained influence of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, reticular fibroblasts undergo significant activation, characterized by proliferation, migration, and synthesis of thick and well-organized collagen fibers [

1,

28]. Simultaneously, adipose precursor cells proliferate and evolve into mature adipocytes, collaboratively contributing to wound filling and granulation tissue formation [

29]. Dermal papillary fibroblasts, in contrast, migrate into the wound site at a slightly later stage (during epithelialization) and produce poorly organized ECM [

28]. Epidermal cells move into the healing wound by polymerizing cytoskeletal actin fibers in the outgrowth and forming new adhesion complexes, culminating in wound closure [

30].

Initially, cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) from epidermal cells prompt adjacent DFs to synthesize and secrete a spectrum of growth factors (

Figure 1), including keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-6, IL-8, IL-1, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF), and to express cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [

31,

32]. In its turn, these soluble factors, mainly KGF, HGF, and PGE2 (

Figure 1), enhance the proliferation, physiological differentiation and basement membrane deposition of epidermal cells [

32]. In later stages, an increase in TGF-β-dependent gene expression and a decrease in nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation occur. Concurrently, under the combined influence of TGF-β and endothelin-1 (ET-1), a subset of DFs begins to express significant levels of alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), transitioning into myofibroblasts [

33]. This transition is crucial for establishing mechanical tension within the wound area [

28]. At the same time, a delicate balance between pro-fibrotic and anti-fibrotic signals, cellular activities, and mechanical cues mitigates excessive fibrosis in the wound repair area.

Another crucial process is ECM remodeling, involving the synthesis and arrangement of collagen, elastin, and other constituents. In the early stages of wound healing, fibrin is deposited to create a temporary matrix clot. This clot helps to stop bleeding and provides a provisional scaffold for cell migration and tissue repair [

34,

35]. As the wound healing process progresses, fibroblasts migrate into the wound area and secrete new collagen, primarily Type III collagen, to replace the temporary fibrin clot. Type III collagen provides initial strength to the healing tissue. Over time, the Type III collagen is gradually replaced by Type I collagen, which is stronger and more durable [

36,

37]. Disruptions in collagen synthesis, degradation, or organization can lead to impaired wound healing and the formation of abnormal scars.

Dermal Sheath Cells: Characteristics and Heterogeneity

DSCs are derived from the neural crest during embryonic development and are characterized by their distinct molecular markers and phenotypic features. Key markers used to sort DSCs include αSMA, SOX2 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα) [

8,

38,

39]. Recent single-cell transcriptome sequencing (scRNA-seq) analyses have identified new markers for DSCs, such as

COL11A1 in humans,[

2,

6]. and

ACAN and

ITGA8 in mice [

38,

40]. DSCs are now recognized as resident stem cells in the skin [

5,

10,

11], and their functions vary according to their specific locations. A key characteristic of DSCs is their ability to induce the formation of new hair follicles [

5,

41,

42]. A particular subset of DSCs that remain after catagen and tightly wrap the telogen dermal papilla (DP) are a stem cell population that self-renews and replenishes the entire DS and contributes to the DP during the following anagen hair growth, and have been termed hair follicle dermal stem cells [

8,

40,

43]. Additionally, in humans, DSCs derived from the lower part of the DS have been considered as hair follicle-derived mesenchymal stromal cells [

44]. These cells express neural markers and possess stem cell properties, and are viewed as a promising source for immunomodulation [

44]. There are also DSCs in humans that express CD36, undergo changes in location in accordance with the hair cycle, and appear to be involved in the process of angiogenesis [

45]. Furthermore, DSCs are also linked to the production of ECM proteins.

In this review, we examined every subset and all name variations of DSCs across different species; however, the differences and similarities among them have not yet been fully explained. These include hair follicle dermal stem cells in mice [

43,

46]; hair follicle-derived mesenchymal stromal cells [

44], CD36-expressing DSCs [

45], and hair follicle dermal sheath mesenchymal stromal cells in humans [

47]; and upper and lower follicle DSCs in rats [

48].

Modulatory Potential of Dermal Sheath Cells in Inflammatory Responses

The inflammatory phase of wound healing is characterized by the activation of immune cells and the release of various inflammatory mediators. Recent research suggests that DSCs may play a crucial role in this phase, potentially influencing immune cell behavior and cytokine secretion, thereby modulating the inflammatory response and promoting tissue repair.

Studies have indicated that DSCs may influence the inflammatory response by secreting several cytokines and chemokines, like platelet-derived growth factor C (PDGF-C), PDGF-D, IL-6 and IL-8. [

38,

47]PDGFs drive cell recruitment to damaged tissue [

49]. They initiate chemotaxis of neutrophils, macrophages, fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells, facilitating the healing process to the inflammation stage [

50,

51]. A conditioned medium from human hair follicle dermal sheath mesenchymal stromal cells demonstrated enhanced wound-healing effects on human skin keratinocytes, fibroblasts and endothelial cells

in vitro, and shorter wound-healing time in diabetic mice in vivo [

47]. Later these cells were found to secrete paracrine factors such as IL-6 and IL-8 [

47]. IL-6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that helps in recruiting immune cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, to the wound site [

52,

53]. In IL-6 knockout mice, the reduction of wound area was delayed with attenuated leukocyte infiltration, re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, and collagen accumulation [

53]. IL-8 primarily functions as a chemoattractant for neutrophils, involved in balancing pro- and anti-inflammatory responses, as well as the polarization and depolarization of neutrophils at the wound site [

54,

55]. Under the influence of these cytokines, DSCs may modulate neutrophil infiltration to the wound site, promoting their recruitment or limiting excessive infiltration. Additionally,

Moreover, human hair follicle-derived mesenchymal stromal cells from the lower DS have been found to promote the polarization of macrophages towards the M2 phenotype, which is associated with a more regenerative environment [

44]. M1 macrophages promote inflammation. This M1–M2 transition is critical for the resolution of inflammation and tipping the balance to tissue repair [

56].

Additionally, an unbiased reassessment of unpublished single-cell RNA-Seq data by Jeff Biernaskie et al. revealed significant interactions between CD200

+Stmn2

+ DSCs (including dermal stem cells of the dermal cup) and CD68

+F480

+ peri-follicular macrophages [

57]. These cells were co-isolated from 28-day-old anagen backskin of mice using the 10× Chromium platform. By employing the Cell-Cell Interactions (CCInx) R package to analyze intercellular communication interactomes, a variety of macrophage-derived ligands (e.g., C1qa, C1qb, C1qc, ApoE, and Gelsolin) were identified with corresponding receptors on dermal sheath cells [

57]. Multiple macrophage receptors were found predicted to be activated by DS-derived ligands, primarily components of the ECM [

57]. These interactions suggest a complex communication network between DSCs and macrophages, which may have significant implications for wound healing and fibrosis.

In summary, while DSCs show promise in modulating inflammatory responses through the secretion of various cytokines and chemokines, the complex interactions between DSCs and macrophages, as suggested by recent findings, indicate significant potential for influencing wound healing and fibrosis. Further research is needed to directly link DSCs to specific immune cell infiltration and to fully elucidate their role in these processes.

Dermal Sheath Cells Are Activated in the Proliferation Phase

In the proliferation phase, there is an increase in the activity of various cell types. These cells proliferate and migrate to the wound site, contributing to the rebuilding of the dermal and epidermal tissues.

Jahoda et al. first proposed the hypothesis that DSCs might have significant value in skin wound healing [

5]. Experiments using fluorescent dye to trace cells revealed that hair follicle DSCs appear in the newly formed granulation tissue during the proliferation phase [

48]. Certain research has suggested that hair follicle–associated fibroblasts, including DSCs and DP cells, are vital for the regeneration of hair follicles following injury [

40]. Jahoda et al. argued that DSCs from different parts of the hair follicle have distinct roles during the healing process: DSCs from the upper part (upper follicle dermal sheath, UDS) only participate in wound healing, whereas those from the lower part (lower follicle dermal sheath, LDS) not only contribute to wound healing but also engage in the growth cycle of adjacent follicles [

48]. This discovery aligns with the findings of Abbasi et al. in 2019 [

46]. They conducted cell lineage tracing studies using αSMACreER

T [

2]:Rosa26

YFP mice and found that the DS-derived dermal stem cells are activated after a wound occurs [

46]. A portion of these cells actively migrate into the wound area to participate in skin wound healing. Another portion integrates into the DP of peri-wound hair follicles; this bias toward a DP fate only occurred when a wound was induced during certain stages of the hair cycle. This finding was also supported by Rahmani’s research [

43]. In addition, a lineage tracing study has shown that in wound-induced hair follicle neogenesis (WIHN) – a phenomenon involving the reemergence of hair follicles at the center of large-size wounds in adult mouse back skin – the fibroblasts of the DS and DP within hair follicles contribute minorly to the formation of new hair follicles. Instead, a separate extrafollicular lineage of fibroblasts distinguished by Hic1 expression gave rise to 90% of the DP cells within the newly formed follicles [

58]. For a long time, DSCs have been considered as the cellular pool that replenishes the DP during the hair follicle regeneration cycle [

48,

59,

60], with the control of thrombin signaling through PI3K being a mechanism that underlies this process [

61]. Incredibly, it now appears that this concept is not applicable to WIHN. In the field of tissue-engineered skin, Higgins et al. reported that four subtypes of DFs (papillary fibroblasts, reticular fibroblasts, DSCs, and DP cells) all support the growth of overlying epidermal cells, both in vivo and in vitro [

62]. Surprisingly, DSCs were found to be more conducive to the formation of the basement membrane [

48,

62]. This may be related to the characteristic of DSCs in abundantly expressing type IV collagen and laminin, both critical components of the basement membrane [

38,

63]. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that DP cells do not participate in skin wound healing [

64,

65].

Dermal Sheath Cells may Contribute to Angiogenesis and Vascularization

Angiogenesis and vascularization are crucial for delivering oxygen and nutrients to the healing tissue and typically occur during the proliferative phase of wound healing. Studies have suggested that DSCs may contribute to these processes.

Yoshida et al. reported a subset of DSCs exhibits high levels of CD36 expression, a characteristic not observed in DP cells or DFs [

45]. CD36 expression was observed at the perivascular region in the entire LDS at anagen III-IV, and in the UDS at anagen V-VI. Co-culture experiment confirmed that CD36-enriched DSCs promoted proliferation of blood endothelial cells in vitro in a cell-cell contact-dependent manner [

45]. These interactions may contribute to the stabilization and maturation of newly formed blood vessels, facilitating their integration into the surrounding tissue. Besides, CD36-enriched DSCs, compared to CD36-negative DSCs, demonstrated increased expression of HGF, which is a known pro-angiogenic factor [

45]. However, it should be noted that Yoshida

et al.‘s study did not specifically separate DSCs from other cell types within the connective tissue sheath (CTS), which consists of multiple cell types such as DSCs, blood vessels, immune cells, fat cells, and sparsely intermingled αSMA- fibroblasts distinct from the DSCs [

66]. Further, they have not provided any evidence that CD36 is expressed by DSCs by performing any dual stains.

The secretion of cytokines such as PDGF-C and PDGF-D by DSCs [

38]. can influence endothelial cell behavior and promote vascularization. PDGF-C [

38], for instance, is known to be involved in angiogenesis [

67,

68,

69]. While endothelial cells are directly responsible for the formation of these new blood vessels, PDGF-C influences this process primarily acting on pericytes and smooth muscle cells [

70]. There are other studies confirmed that PDGF-C can not only promote the angiogenic effect of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) but also independently promote the formation of new blood vessels [

71]. PDGF-D [

38], another member of the PDGF family that involved in angiogenesis, exerts its effects by binding to specific cell surface receptors, primarily PDGF receptor β (PDGFR-β) [

72]. This binding activates signaling pathways that lead to cell proliferation, migration, and survival [

73,

74,

75], all of which are essential for angiogenesis and vascularization.

Overall, while DSCs are likely to contribute to angiogenesis and vascularization through direct cell-cell contact and the secretion of cytokines that promote the formation and maturation of new blood vessels, it remains unclear whether DSCs enhance vascularization during follicle regeneration and cannot be extrapolated to the wound healing scenario without more evidence.

Extracellular Matrix Remodeling and Dermal Sheath Cells

ECM remodeling is a sophisticated and intricate process that plays a crucial role in the final phase of healing. Currently, there is limited research available on the direct involvement of DSCs in ECM remodeling. However, the findings presented here suggest that DSCs possess the capability to regulate ECM remodeling.

Collagen is the main structural component and the most abundant protein in the ECM, with 85% of the dermis being collagen. Heitman et al. characterized 483 enriched genes reflecting specialized functions of DS compared to DP and DF in the anagen skin of mice [

76]. From

Table 1, we can see collagen types 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 11, 12, 16, and 27 were expressed in DSCs. In the study, DSCs expressed more types of collagen compared to other cell types. Specifically, collagen type I was expressed in both DSCs and DFs, while collagen type III could only be seen in DSCs. During remodeling, the wound area experiences a significant transition from type III to type I collagen, enhancing tissue strength and resilience [

36,

37]. DSCs have been shown to migrate into granulation tissue during wound healing [

46,

48], suggesting they are involved in collagen remodeling.

MMPs are key enzymes in this phase, responsible for degrading old or damaged ECM components, and are balanced by tissue inhibitors to prevent excessive breakdown. DFs and myofibroblasts are central to this process, whereas DSCs have not been reported in this respect. In spite of this, we still attempted to explore the MMPs that can be expressed by DSCs (

Table 2) and to delve into their roles in wound healing. One in situ study found that the expression of MMP1 in human scalp hair follicle DSCs elevated with age [

77]. In a rat model, MMP-1 improved the wound-healing process of skin with higher epithelial hyperplasia and reduced scar formation [

78]. Heitman

et al.’s study [

38], which used P5 mice for transcriptome analysis, revealed that MMP11 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1) were expressed in anagen hair follicle DSCs, in contrast to MMP2, MMP19, and MMP27, which were expressed in DFs; MMP23 was found to be expressed in both cell types (

Table 2). Recent research has shown that MMP23 is involved in inflammatory bowel disease [

79] and wound healing after traumatic injury [

80]. MMP11 was also found to be expressed in DSCs of human scalp [

81]. Unlike most MMPs, which are secreted as inactive proenzymes and activated extracellularly, MMP11 is secreted in its active form yet cannot degrade any major ECM components [

82,

83]. Active MMP11 released by fibroblasts promotes epithelial cell apoptosis and growth of connective tissues [

84]. MMP11 may thus play a unique role in tissue remodeling processes. A study using the tissue-engineered human cornea investigated MMPs during corneal wound healing. It found that MMP11 expression significantly increased in the central area of wounded, reconstructed corneas within 24 hours and then progressively decreased as the wounds were closing, with MMP11 appearing to be dose-dependently upregulated by IL-1β and TNF-α [

85]. Research in the field of tumor has reported that MMP11 can promote cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, while microRNA-125a/b can inhibit its effects by directly targeting MMP11 [

83,

86]. MMPs can be inhibited in 1:1 stoichiometry by TIMP family (TIMP1~4). TIMP1 inhibits most MMPs but weak for MMP14, MMP16, MMP19 and MMP24 (

Table 2) [

87], binding particularly strongly to MMP9 and pro-MMP9 [

88]. Besides, TIMP1 can interact with the proforms of MMPs in a non-inhibitory manner, and also have functions independent of MMP inhibition by directly binding to CD63 [

89]. This suggests that DSCs may establish contact with endothelial cells and platelets by paracrine signaling. In psoriasis, TIMP1 and TIMP3 are present in the inflammatory infiltrate and in the endothelial cells of the papillary dermis [

89]. In the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers, an increased ratio of serum MMP9 against TIMP1 predicts poor wound healing [

90]. We also determined that TIMP1, TIMP2, and TIMP3 were differentially expressed between human healthy skin DFs and those from patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc) [

2], indicating potential therapeutic targets in SSc. Additionally, TIMP1 is a negative regulator of adipogenesis [

91,

92], suggesting that it may play a role in the recovery of the subcutaneous adipose layer after wound. Above all, although we have identified specific MMPs and their inhibitors expressed by DSCs, the comprehensive mapping of their expression profiles within DSCs throughout the different phases of wound healing remains a largely unexplored territory, presenting a significant opportunity for future studies to unravel these complex interactions and their implications in tissue repair and regeneration.

Paracrine Effects of Dermal Sheath Cells

As mentioned earlier, DSCs exhibit the ability to produce IL-6 and IL-8 during the inflammatory phase of wound healing. Moreover, the discussion extends to the secreted protein CD36, HGF, PDGF-C, and PDGF-D concerning the proliferation stage. The remodeling phase further delves into the role of MMPs and their inhibitors. Ahlers et al. demonstrated that DS-secreted proteins exerted paracrine effects on primary keratinocytes and DFs, promoting proliferation, epidermal thickness and procollagen production [

6]. Specifically, all tested proteins, including midkine, activin A and retinol binding protein 4, increased the proliferation of primary keratinocytes [

6]. In particular, activin A significantly increased epidermal thickness and fibroblast procollagen type I c-peptide production in a 3D skin model [

6]. Importantly, the paracrine effects of DSCs unveil a spectrum of functions that may surpass initial expectations in terms of breadth and complexity.

Potential Role of Dermal Sheath Cells in Fibrosis

The remodeling phase also involves scar maturation, where the scar tissue undergoes changes to become more like the original tissue in terms of appearance and functionality. Research indicates that DSCs are not just passive bystanders but may participate in the fibrotic process. When triggered by certain stimuli, such as injury or inflammatory signals, these cells can differentiate or transform into a myofibroblast or wound healing phenotype [

5,

27,

95]. ScRNA-seq analysis revealed multiple genes shared between DSCs and myofibroblasts [

2], including high

ACTA2 expression, the gene encoding smooth muscle actin (SMA). DSCs express other markers common to myofibroblasts, including

COL11A1, and cluster proximal to myofibroblasts in Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plots [

2], suggesting that DSCs have similar characteristics or expression profiles to myofibroblasts. In wound healing, myofibroblasts are instrumental in fibrosis by producing ECM, which is essential for tissue repair but can also lead to excessive scarring if dysregulated. As mentioned earlier, anagen hair follicle DSCs were found to express TIMP1. TIMP1 is the best predictor of TGF-β1, which has been demonstrated to promote myofibroblast formation and is a hallmark of fibrosis [

89,

96], indicating that DSCs may impact fibrosis. However, it is important to note that the contribution of DSCs to wound healing by differentiating into myofibroblasts is minimal, as suggested by Abbasi et al. (2020) [

58].

Another study also indicated that DSCs might be involved in the process of fibrosis, particularly through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [

8]. TGF-β, Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways are widely recognized as major players for regenerative wound healing. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a well-known key player for enhancement of the overall healing process involving tissue regeneration via crosstalk with other signaling pathways [

97]. The activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway elicits a range of healing responses, including the promotion of angiogenesis [

98,

99], enhancement of fibroblast migration, proliferation, and differentiation [

1,

97], stimulation of keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation [

100,

101], facilitation of re-epithelialization [

102,

103], and the induction of wound-induced hair folliculogenesis [

104,

105]. A cell tracing study reported that constitutive activation of β-catenin in DS not only generated ectopic hair follicle outgrowth, endowing DSCs with hair-inducing ability, but also induced cell-autonomous progressive skin fibrosis in the dermis, where the excessive fibroblasts largely originated from the DS [

8]. Gene expression analysis of purified DSCs with activated β-catenin revealed a significant increase in the expression of Bmp, Fgf, and Notch ligands [

8], potentially serving as precursors to the signaling cascade crucial for skin regeneration. However, it should be noted that there is no direct evidence of DSCs contributing to skin fibrosis during wound healing under physiological conditions. The study by Tao et al. (2019) [

8] represents a scenario where β-catenin is overexpressed in αSMA+ cells, which is not typically seen under normal physiological conditions.

En1-lineage-past fibroblasts (EPFs) of fascia were shown to be responsible for most connective tissue deposition in skin fibrosis during wound healing [

106]. Notably, in all the GEO datasets (GSE215133[

107], GSE136996[

76], GSE81615[

8]) from the transcriptome sequencing studies we have examined, DSCs consistently expresses En1, at levels that are consistent with or even higher than those of DFs (GSE215133 & GSE136996). However, this information alone is not sufficient to definitively determine that DSCs belong to the En1-lineage-past fibroblasts (EPFs), as the identification of EPFs typically involves lineage tracing experiments and additional validation techniques such as dual staining and comparative gene expression profiling.

Abnormal contractions of myofibroblasts result in tissue contractures and stiffness. Myofibroblast contractions are separately regulated by Ca

2+ dependent myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) and Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) within the same cell [

108,

109,

110]. ROCK maintains stress fibers in the center of cells whereas MLCK drives stress fiber assembly in the periphery [

109]. A recent study demonstrates that ET-1, derived from epithelial cells, can trigger DS contraction through both ET

A and ET

B receptors by activating the Ca

2+ dependent MLCK pathway [

107]. This finding suggests that DSCs share a similar contraction mechanism with myofibroblasts. Consequently, when a wound occurs and DSCs migrate to the wound site, abnormal contractions in DSCs could potentially contribute to tissue fibrosis.

Dermal Sheath Cells Work Differently in Healing Hairy and Non-Hairy Sites

Clinicians have long reported that hair-bearing areas (hairy sites) tend to heal more rapidly than those lacking hair follicles (non-hairy sites) [

111]. A study notes that in animals with high densities of hair follicles, differences in wound healing are observed alongside changes in the hair growth cycle [

112]. This observation extends to humans, where apparent differences in wound healing responses are seen between hairy sites and non-hairy sites [

5]. This suggests a link between hair follicle density, DSCs activity, and wound healing efficacy. Furthermore, the study indicates that the involvement of DSCs may lead to qualitatively improved dermal repair. This opens up therapeutic possibilities, such as using DSCs to create dermal or full skin equivalents to improve wound healing and reduce scarring. Additionally, the inductive properties of these cells make them promising for tissue engineering applications. This potential could lead to the development of skin equivalents capable of growing hair follicles when grafted.

Conclusions and Future Challenges

This review has extensively discussed the multifaceted role of DSCs in the context of wound healing. DSCs are pivotal in modulating cell activity, orchestrating collagen synthesis, and influencing ECM remodeling through intricate networks of paracrine signaling and cell-cell interactions. Their contribution is vital for the maintenance and restructuring of the dermal ECM, which is a cornerstone in achieving effective wound healing and tissue homeostasis.

Despite the advancements in understanding the role of DSCs, numerous aspects remain underexplored or unclear, presenting considerable challenges and opportunities for future research. One significant area is the specific molecular pathways and mechanisms by which DSCs regulate these critical processes. Although their influence on cell activity and collagen synthesis is recognized, the detailed molecular interactions and signaling pathways involved are not fully delineated.

Another critical gap lies in our understanding of the heterogeneity and plasticity of DSCs. The diverse subpopulations of DSCs and their respective roles in different phases of wound healing are not comprehensively understood. This diversity hints at a complex regulatory network, where different DSC subsets may have unique functions or interactions with other cell types in the wound microenvironment.

In summary, while DSCs have emerged as crucial players in wound healing, their full potential and the breadth of their roles are yet to be fully uncovered. Future studies should aim to unravel these aspects, potentially leading to novel therapeutic approaches for wound care and tissue regeneration.

Author Contributions

B.Z., L.L., L.H., Y.L. conceived the manuscript. B.Z. and L.H. wrote the manuscript. B.Z. and L.L. designed the figures. B.Z., L.L., L.H. and Y.L. edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060354) and Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (2020MS08166, 2021LHMS08028).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

αSMA, alpha-smooth muscle actin; COX2, cyclooxygenase 2; CTS, connective tissue sheath; DFs, dermal fibroblasts; DP, dermal papilla; DSCs, dermal sheath cells; ET-1, endothelin-1; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HB-EGF, heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IL-1, interleukin-1; KGF, keratinocyte growth factor; LDS, lower follicle dermal sheath; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; PDGF-C, platelet-derived growth factor C; PDGFRα, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; ROCK, rho-associated protein kinase; scRNA-seq, single-cell transcriptome sequencing; SSc, systemic sclerosis; TIMP1, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection; UDS, upper follicle dermal sheath; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; WIHN, wound-induced hair follicle neogenesis.

References

- Driskell, R.R.; Lichtenberger, B.M.; Hoste, E.; Kretzschmar, K.; Simons, B.D.; Charalambous, M.; Ferron, S.R.; Herault, Y.; Pavlovic, G.; Ferguson-Smith, A.C.; et al. Distinct fibroblast lineages determine dermal architecture in skin development and repair. Nature 2013, 504, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabib, T.; Huang, M.; Morse, N.; Papazoglou, A.; Behera, R.; Jia, M.; Bulik, M.; Monier, D.E.; Benos, P.V.; Chen, W.; et al. Myofibroblast transcriptome indicates SFRP2hi fibroblast progenitors in systemic sclerosis skin. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascensión, A.M.; Fuertes-Álvarez, S.; Ibañez-Solé, O.; Izeta, A.; Araúzo-Bravo, M.J. Human Dermal Fibroblast Subpopulations Are Conserved across Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Studies. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 141, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams R, Thornton MJ. Isolation of different dermal fibroblast populations from the skin and the hair follicle. Molecular Dermatology: Methods and Protocols 2020;13-22.

- Jahoda CA, Reynolds AJ. Hair follicle dermal sheath cells: unsung participants in wound healing. The Lancet 2001;358:1445-1448.

- Ahlers, J.M.D.; Falckenhayn, C.; Holzscheck, N.; Solé-Boldo, L.; Schütz, S.; Wenck, H.; Winnefeld, M.; Lyko, F.; Grönniger, E.; Siracusa, A. Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Human Skin Reveals Age-Related Loss of Dermal Sheath Cells and Their Contribution to a Juvenile Phenotype. Front. Genet. 2022, 12, 797747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plikus MV, Wang X, Sinha S, Forte E, Thompson SM, Herzog EL, Driskell RR, Rosenthal N, Biernaskie J, Horsley V. Fibroblasts: Origins, definitions, and functions in health and disease. Cell 2021;184:3852-3872.

- Tao Y, Yang Q, Wang L, Zhang J, Zhu X, Sun Q, Han Y, Luo Q, Wang Y, Guo X, Wu J, Li B, Yang X, He L, Ma G. beta-catenin activation in hair follicle dermal stem cells induces ectopic hair outgrowth and skin fibrosis. J Mol Cell Biol 2019;11:26-38.

- Martino, P.A.; Heitman, N.; Rendl, M. The dermal sheath: An emerging component of the hair follicle stem cell niche. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 30, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; John, J.R. Role of stem cells in the management of chronic wounds. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2012, 45, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, N.; Bartfeld, S.; Clevers, H. Tissue-Resident Adult Stem Cell Populations of Rapidly Self-Renewing Organs. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 7, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurtner, G.C.; Werner, S.; Barrandon, Y.; Longaker, M.T. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 2008, 453, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park E, Lee SM, Jung I-K, Lim Y, Kim J-H. Effects of genistein on early-stage cutaneous wound healing. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2011;410:514-519.

- Nurden AT, Nurden P, Sanchez M, Andia I, Anitua E. Platelets and wound healing. Front Biosci 2008;13:3532-48.

- A Lenselink, E. Role of fibronectin in normal wound healing. Int. Wound J. 2013, 12, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Sommerville, L.; Nellenbach, K.; Mihalko, E.; Erb, M.; Freytes, D.O.; Hoffman, M.; Monroe, D.; Brown, A.C. Platelet-like particles improve fibrin network properties in a hemophilic model of provisional matrix structural defects. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 577, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross R, Odland G. Human wound repair: II. Inflammatory cells, epithelial-mesenchymal interrelations, and fibrogenesis. The Journal of cell biology 1968;39:152-168.

- Barbul, A.; Shawe, T.; Rotter, S.; Efron, J.; Wasserkrug, H.; Badawy, S. WOUND-HEALING IN NUDE-MICE - A STUDY ON THE REGULATORY ROLE OF LYMPHOCYTES IN FIBROPLASIA. 1989, 105, 764–769.

- Barbul, A.; Breslin, R.J.; Woodyard, J.P.; Wasserkrug, H.L.; Efron, G. The Effect of In Vivo T Helper and T Suppressor Lymphocyte Depletion on Wound Healing. Ann. Surg. 1989, 209, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artuc M, Hermes B, Stckelings U, Grützkau A, Henz B. Mast cells and their mediators in cutaneous wound healing–active participants or innocent bystanders? Experimental dermatology 1999;8:1-16.

- Landén, N.X.; Li, D.; Ståhle, M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: a critical step during wound healing. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3861–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, L.E.; Minasian, R.A.; Caterson, E. Extracellular Matrix and Dermal Fibroblast Function in the Healing Wound. Adv. Wound Care 2016, 5, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kirsner, R.S. Angiogenesis in wound repair: Angiogenic growth factors and the extracellular matrix. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2002, 60, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja KS, Garcia MS, Isseroff RR. Wound re-epithelialization: modulating keratinocyte migration in wound healing. Front Biosci-Landmrk 2007;12:2849-2868.

- Tang, F.; Li, J.; Xie, W.; Mo, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Zhao, F.; Fu, X.; Chen, X. Bioactive glass promotes the barrier functional behaviors of keratinocytes and improves the Re-epithelialization in wound healing in diabetic rats. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 3496–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, A.D.; Davis, F.M.; Kunkel, S.L.; Gallagher, K.A. Targeting epigenetic mechanisms in diabetic wound healing. Transl. Res. 2018, 204, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, I.A.; Laverdet, B.; Bonté, F.; Desmouliere, A. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in wound healing. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 7, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippa, A.L.; Kalabusheva, E.P.; Vorotelyak, E.A. Regeneration of Dermis: Scarring and Cells Involved. Cells 2019, 8, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.A.; Horsley, V. Intradermal adipocytes mediate fibroblast recruitment during skin wound healing. Development 2013, 140, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousselle, P.; Braye, F.; Dayan, G. Re-epithelialization of adult skin wounds: Cellular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 146, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Krieg, T.; Smola, H. Keratinocyte–Fibroblast Interactions in Wound Healing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, B.; Brembilla, N.C.; Chizzolini, C. Interplay Between Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts: A Systematic Review Providing a New Angle for Understanding Skin Fibrotic Disorders. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira RC, Wilson SE. Fibrocytes, Wound Healing, and Corneal Fibrosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2020;61:28.

- Hsu, P.W.; Salgado, C.J.; Kent, K.; Finnegan, M.; Pello, M.; Simons, R.; Atabek, U.; Kann, B. Evaluation of porcine dermal collagen (Permacol) used in abdominal wall reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2009, 62, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midwood, K.S.; Williams, L.V.; Schwarzbauer, J.E. Tissue repair and the dynamics of the extracellular matrix. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 36, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hade, M.D.; Suire, C.N.; Mossell, J.; Suo, Z. Extracellular vesicles: Emerging frontiers in wound healing. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 2102–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Jackson, C.J. Extracellular Matrix Reorganization During Wound Healing and Its Impact on Abnormal Scarring. Adv. Wound Care 2015, 4, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitman, N.; Sennett, R.; Mok, K.-W.; Saxena, N.; Srivastava, D.; Martino, P.; Grisanti, L.; Wang, Z.; Ma’ayan, A.; Rompolas, P.; et al. Dermal sheath contraction powers stem cell niche relocation during hair cycle regression. Science 2019, 367, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agabalyan NA, Hagner A, Rahmani W, Biernaskie J. SOX2 in the skin. In: Sox2. Elsevier: 2016; 281-300.

- Shin, W.; Rosin, N.L.; Sparks, H.; Sinha, S.; Rahmani, W.; Sharma, N.; Workentine, M.; Abbasi, S.; Labit, E.; Stratton, J.A.; et al. Dysfunction of Hair Follicle Mesenchymal Progenitors Contributes to Age-Associated Hair Loss. Dev. Cell 2020, 53, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, K.; Wickett, R.R.; Andl, T.; Zhang, Y. Dermal sheath cells contribute to postnatal hair follicle growth and cycling. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2016, 82, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, T.; Inamatsu, M.; Yoshizato, K. The upper dermal sheath has a potential to regenerate the hair in the rat follicular epidermis. Differentiation 1996, 60, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, W.; Abbasi, S.; Hagner, A.; Raharjo, E.; Kumar, R.; Hotta, A.; Magness, S.; Metzger, D.; Biernaskie, J. Hair Follicle Dermal Stem Cells Regenerate the Dermal Sheath, Repopulate the Dermal Papilla, and Modulate Hair Type. Dev. Cell 2014, 31, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernaez-Estrada, B.; Gonzalez-Pujana, A.; Cuevas, A.; Izeta, A.; Spiller, K.L.; Igartua, M.; Santos-Vizcaino, E.; Hernandez, R.M. Human Hair Follicle-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells from the Lower Dermal Sheath as a Competitive Alternative for Immunomodulation. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, Y.; Soma, T.; Kishimoto, J. Characterization of human dermal sheath cells reveals CD36-expressing perivascular cells associated with capillary blood vessel formation in hair follicles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 516, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Biernaskie, J. Injury modifies the fate of hair follicle dermal stem cell progeny in a hair cycle-dependent manner. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Kua, J.E.H.; Lim, W.K.; Lee, S.T.; Chua, A.W.C. In vitro characterization of human hair follicle dermal sheath mesenchymal stromal cells and their potential in enhancing diabetic wound healing. Cytotherapy 2015, 17, 1036–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharzi, A.; Reynolds, A.J.; Jahoda, C.A.B. Plasticity of hair follicle dermal cells in wound healing and induction. Exp. Dermatol. 2003, 12, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Liu, G.; Halim, A.; Ju, Y.; Luo, Q.; Song, G. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration and Tissue Repair. Cells 2019, 8, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diller, R.B.; Tabor, A.J. The Role of the Extracellular Matrix (ECM) in Wound Healing: A Review. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ather S, Harding K, Tate S. Wound management and dressings. In: Advanced textiles for wound care. Elsevier: 2019; 1-22.

- Fielding, C.A.; McLoughlin, R.M.; McLeod, L.; Colmont, C.S.; Najdovska, M.; Grail, D.; Ernst, M.; Jones, S.A.; Topley, N.; Jenkins, B.J. IL-6 Regulates Neutrophil Trafficking during Acute Inflammation via STAT3. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 2189–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.-Q.; Kondo, T.; Ishida, Y.; Takayasu, T.; Mukaida, N. Essential involvement of IL-6 in the skin wound-healing process as evidenced by delayed wound healing in IL-6-deficient mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2003, 73, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, S.; Hug, S.; Stratmann, A.E.P.; Erber, M.; Vidoni, L.; Knapp, C.L.; Thomaß, B.D.; Fauler, M.; Nilsson, B.; Ekdahl, K.N.; et al. Interleukin 8 Elicits Rapid Physiological Changes in Neutrophils That Are Altered by Inflammatory Conditions. J. Innate Immun. 2021, 13, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, R.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, Q.; Kong, R.; Xiang, X.; Liu, H.; Feng, M.; Wang, F.; Cheng, J.; Li, Z.; et al. Liver tumour immune microenvironment subtypes and neutrophil heterogeneity. Nature 2022, 612, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosser, D.M.; Edwards, J.P. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, W.; Sinha, S.; Biernaskie, J. Immune modulation of hair follicle regeneration. npj Regen. Med. 2020, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi S, Sinha S, Labit E, Rosin NL, Yoon G, Rahmani W, Jaffer A, Sharma N, Hagner A, Shah P, Arora R, Yoon J, Islam A, Uchida A, Chang CK, Stratton JA, Scott RW, Rossi FMV, Underhill TM, Biernaskie J. Distinct Regulatory Programs Control the Latent Regenerative Potential of Dermal Fibroblasts during Wound Healing. Cell Stem Cell 2021;28:581-583.

- Tobin, D.J.; Magerl, M.; Gunin, A.; Handijski, B.; Paus, R. Plasticity and Cytokinetic Dynamics of the Hair Follicle Mesenchyme: Implications for Hair Growth Control. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 120, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.Y.; Enshell-Seijffers, D.; Morgan, B.A. De Novo Production of Dermal Papilla Cells during the Anagen Phase of the Hair Cycle. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 2664–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feutz, A.-C.; Barrandon, Y.; Monard, D. Control of thrombin signaling through PI3K is a mechanism underlying plasticity between hair follicle dermal sheath and papilla cells. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.; Roger, M.; Hill, R.; Ali-Khan, A.; Garlick, J.; Christiano, A.; Jahoda, C. Multifaceted role of hair follicle dermal cells in bioengineered skins. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 176, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharzi, A. Dermal and epidermal cell functions in the growth and regeneration of hair follicles and other skin appendages. Durham University: 1998.

- Rognoni, E.; Watt, F.M. Skin Cell Heterogeneity in Development, Wound Healing, and Cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, G.S.; Rognoni, E.; Lichtenberger, B.M.; Driskell, R.R.; Kretzschmar, K.; Hoste, E.; Watt, F.M. Fate of Prominin-1 Expressing Dermal Papilla Cells during Homeostasis, Wound Healing and Wnt Activation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 2926–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, P.A.; Heitman, N.; Rendl, M. The dermal sheath: An emerging component of the hair follicle stem cell niche. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 30, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Kumar, A.; Zhang, F.; Lee, C.; Li, Y.; Tang, Z.; Arjunan, P. VEGF-independent angiogenic pathways induced by PDGF-C. Oncotarget 2010, 1, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, Y.; Kasman, I.; Yu, L.; Zhong, C.; Wu, X.; Modrusan, Z.; Kaminker, J.; Ferrara, N. PDGF-C Mediates the Angiogenic and Tumorigenic Properties of Fibroblasts Associated with Tumors Refractory to Anti-VEGF Treatment. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriya, J.; Ferrara, N. Inhibition of protein kinase C enhances angiogenesis induced by platelet-derived growth factor C in hyperglycemic endothelial cells. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2015, 14, 19–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folestad, E.; Kunath, A.; Wågsäter, D. PDGF-C and PDGF-D signaling in vascular diseases and animal models. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Zhang, F.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. PDGF-C: a new performer in the neurovascular interplay. Trends Mol. Med. 2013, 19, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Leng, P. Research progress on the role of PDGF/PDGFR in type 2 diabetes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang ZB, Ruan CC, Lin JR, Xu L, Chen XH, Du YN, Fu MX, Kong LR, Zhu DL, Gao PJ. Perivascular Adipose Tissue-Derived PDGF-D Contributes to Aortic Aneurysm Formation During Obesity. Diabetes 2018;67:1549-1560.

- Lu, J.-F.; Hu, Z.-Q.; Yang, M.-X.; Liu, W.-Y.; Pan, G.-F.; Ding, J.-B.; Liu, J.-Z.; Tang, L.; Hu, B.; Li, H.-C. Downregulation of PDGF-D Inhibits Proliferation and Invasion in Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells. Clin. Breast Cancer 2021, 22, e173–e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma S, Tang T, Wu X, Mansour AG, Lu T, Zhang J, Wang L-S, Caligiuri MA, Yu J. PDGF-D− PDGFRβ signaling enhances IL-15–mediated human natural killer cell survival. PNAS 2022;119:e2114134119.

- Heitman, N.; Sennett, R.; Mok, K.-W.; Saxena, N.; Srivastava, D.; Martino, P.; Grisanti, L.; Wang, Z.; Ma’ayan, A.; Rompolas, P.; et al. Dermal sheath contraction powers stem cell niche relocation during hair cycle regression. Science 2019, 367, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Westgate, G.E.; Pawlus, A.D.; Sikkink, S.K.; Thornton, M.J. Age-Related Changes in Female Scalp Dermal Sheath and Dermal Fibroblasts: How the Hair Follicle Environment Impacts Hair Aging. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 141, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin ES, Keskin ER, Öztürk MB, Çakan D. The effect of MMP-1 on wound healing and scar formation. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2021;45:2973-2979.

- Fonseca-Camarillo, G.; Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Martínez-Benitez, B.; Barreto-Zuñiga, R.; Yamamoto-Furusho, J.K. Increased expression of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) and MMP10, MMP23 in inflammatory bowel disease: Cross-sectional study. Scand. J. Immunol. 2020, 93, e12962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Hu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ye, Q.; et al. Effect of Matrix Metalloproteinase 23 Accelerating Wound Healing Induced by Hydroxybutyl Chitosan. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 1460–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niiyama, S.; Ishimatsu-Tsuji, Y.; Nakazawa, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Soma, T.; Ideta, R.; Mukai, H.; Kishimoto, J. Gene Expression Profiling of the Intact Dermal Sheath Cup of Human Hair Follicles. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 2018, 98, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matziari, M.; Dive, V.; Yiotakis, A. Matrix metalloproteinase 11 (MMP-11; stromelysin-3) and synthetic inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev. 2006, 27, 528–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, P.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, J. MicroRNA-125b as a tumor suppressor by targeting MMP11 in breast cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2020, 11, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, L.G.; Thode, H.; Eslambolchi, Y.; Chopra, S.; Young, D.; Gill, S.; Devel, L.; Dufour, A. Matrix Metalloproteinases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Pharmacology. Materials 2022, 74, 712–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couture, C.; Zaniolo, K.; Carrier, P.; Lake, J.; Patenaude, J.; Germain, L.; Guérin, S.L. The tissue-engineered human cornea as a model to study expression of matrix metalloproteinases during corneal wound healing. Biomaterials 2016, 78, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waresijiang, N.; Sun, J.; Abuduaini, R.; Jiang, T.; Zhou, W.; Yuan, H. The downregulation of miR-125a-5p functions as a tumor suppressor by directly targeting MMP-11 in osteosarcoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 4859–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brew, K.; Nagase, H. The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): An ancient family with structural and functional diversity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Cell Res. 2010, 1803, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke RE, Libert C. Is there new hope for therapeutic matrix metalloproteinase inhibition? Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014;13:904-927.

- Cabral-Pacheco, G.A.; Garza-Veloz, I.; la Rosa, C.C.-D.; Ramirez-Acuña, J.M.; A Perez-Romero, B.; Guerrero-Rodriguez, J.F.; Martinez-Avila, N.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. The Roles of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, S.; Yao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T. Increased ratio of serum matrix metalloproteinase-9 against TIMP-1 predicts poor wound healing in diabetic foot ulcers. J. Diabetes its Complicat. 2013, 27, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meissburger, B.; Stachorski, L.; Röder, E.; Rudofsky, G.; Wolfrum, C. Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1) controls adipogenesis in obesity in mice and in humans. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 1468–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, C.M.; Selvarajan, S.; Mudgett, J.; Werb, Z. Stromelysin-1 Regulates Adipogenesis during Mammary Gland Involution. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 152, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, V.L.; Caley, M.; O’toole, E.A. Matrix metalloproteinases and epidermal wound repair. Cell Tissue Res. 2012, 351, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravanti, L.; Kähäri, V.M. Matrix metalloproteinases in wound repair (review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2000, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrazy, V.; Billet, F.; Micallef, L.; Coulomb, B.; Desmoulière, A. Mechanisms of pathological scarring: Role of myofibroblasts and current developments. Wound Repair Regen. 2011, 19, s10–s15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirastschijski, U.; Schnabel, R.; Claes, J.; Schneider, W.; Ågren, M.S.; Haaksma, C.; Tomasek, J.J. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition delays wound healing and blocks the latent transforming growth factor-β1-promoted myofibroblast formation and function. Wound Repair Regen. 2010, 18, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Yoon, M.; Choi, K.-Y. Approaches for Regenerative Healing of Cutaneous Wound with an Emphasis on Strategies Activating the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Adv. Wound Care 2022, 11, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Zhou H, Zhang T, Gao X, Tao B, Xing H, Zhuang Z, Dardik A, Kyriakides TR, Goodwin JE. Loss of endothelial glucocorticoid receptor promotes angiogenesis via upregulation of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Angiogenesis 2021;24:631-645.

- Guo R, Wang X, Fang Y, Chen X, Chen K, Huang W, Chen J, Hu J, Liang F, Du J, Dordoe C, Tian X, Lin L. rhFGF20 promotes angiogenesis and vascular repair following traumatic brain injury by regulating Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2021;143:112200.

- Popp T, Steinritz D, Breit A, Deppe J, Egea V, Schmidt A, Gudermann T, Weber C, Ries C. Wnt5a/β-catenin signaling drives calcium-induced differentiation of human primary keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2014;134:2183-2191.

- Zhu, X.-J.; Liu, Y.; Dai, Z.-M.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Qiu, M.; Fu, J.; Hsu, W.; Chen, Y.; et al. BMP-FGF Signaling Axis Mediates Wnt-Induced Epidermal Stratification in Developing Mammalian Skin. PLOS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004687–e1004687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, M.; Kim, E.; Seo, S.H.; Kim, G.-U.; Choi, K.-Y. KY19382 Accelerates Cutaneous Wound Healing via Activation of the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon M, Seo SH, Choi S, Han G, Choi K-Y. Euodia daniellii Hemsl. Extract and Its Active Component Hesperidin Accelerate Cutaneous Wound Healing via Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Molecules 2022;27:7134.

- Ito, M.; Yang, Z.; Andl, T.; Cui, C.; Kim, N.; Millar, S.E.; Cotsarelis, G. Wnt-dependent de novo hair follicle regeneration in adult mouse skin after wounding. Nature 2007, 447, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Chen H, Tian R, Zhang Y, Drutskaya MS, Wang C, Ge J, Fan Z, Kong D, Wang X, Cai T, Zhou Y, Wang J, Wang J, Wang S, Qin Z, Jia H, Wu Y, Liu J, Nedospasov SA, Tredget EE, Lin M, Liu J, Jiang Y, Wu Y. Macrophages induce AKT/beta-catenin-dependent Lgr5(+) stem cell activation and hair follicle regeneration through TNF. Nat Commun 2017;8:14091.

- Rinkevich, Y.; Walmsley, G.G.; Hu, M.S.; Maan, Z.N.; Newman, A.M.; Drukker, M.; Januszyk, M.; Krampitz, G.W.; Gurtner, G.C.; Lorenz, H.P.; et al. Identification and isolation of a dermal lineage with intrinsic fibrogenic potential. Science 2015, 348, aaa2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, P.; Sunkara, R.; Heitman, N.; Rangl, M.; Brown, A.; Saxena, N.; Grisanti, L.; Kohan, D.; Yanagisawa, M.; Rendl, M. Progenitor-derived endothelin controls dermal sheath contraction for hair follicle regression. Nature 2023, 25, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasek, J.J.; Gabbiani, G.; Hinz, B.; Chaponnier, C.; Brown, R.A. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castella, L.F.; Buscemi, L.; Godbout, C.; Meister, J.-J.; Hinz, B. A new lock-step mechanism of matrix remodelling based on subcellular contractile events. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 1751–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Follonier Castella, L.; Gabbiani, G.; McCulloch, C.A.; Hinz, B. Regulation of myofibroblast activities: Calcium pulls some strings behind the scene. Exp. Cell Res. 2010, 316, 2390–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, F.; Poblet, E.; Izeta, A. Reflections on how wound healing-promoting effects of the hair follicle can be translated into clinical practice. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 24, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debono, R. Histological and immunohistochemical studies of excisional wounds in the rat with special reference to the involvement of the hair follicles in the wound healing process. Durham University: 2000.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

This review brings to light the significant yet often overlooked role of dermal sheath cells (DSCs) in wound healing. It emphasizes their multifunctional roles in inflammation modulation, proliferation aid, and ECM remodeling, and illuminates DSCs’ paracrine effects and their involvement in fibrosis, offering a new perspective on skin repair processes.

This review brings to light the significant yet often overlooked role of dermal sheath cells (DSCs) in wound healing. It emphasizes their multifunctional roles in inflammation modulation, proliferation aid, and ECM remodeling, and illuminates DSCs’ paracrine effects and their involvement in fibrosis, offering a new perspective on skin repair processes.