1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) is a digital manufacturing process which produce a near-net-shape or final shape parts composing of complicated geometries using a heat source for layer-by-layer build up. For metal AM processes, laser-based heat source has been being used for powder bed fusion (PBF) and direct energy deposition (DED) [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Martensitic stainless steel (MSS) 410 has been received great attentions because it possesses key advantages such as high strength and hardness, good corrosion resistance, forming ease, low material cost, air hardening, and good weldability. Due to its superior performances, it has been using in steam turbine components, pump shafts, valves, and bearings [

5,

6]. However, the MSS 410 is required to control strength and ductility of its inherent embrittlement by means of austenitization and tempering heat treatment processes [

7,

8,

9]. Typically, austenitization heat treatment process is followed by quenching, which increases material strength by the phase transformation of austenite to martensite. The austenite phase grows by heating above the austenite transformation start temperature, and holding a sufficient heating time increases the carbon content and diffusion rate into the austenite grain boundaries to preserve a uniform phase composition and then transforms to the martensitic structure by rapid quenching. As a result, it increases hardness and strength. However, its toughness and ductility are very low, that is, it is highly brittle, so tempering heat treatment is necessary to increase toughness and ductility while sacrificing hardness and strength somewhat. Tempering heat treatment includes low-temperature tempering, which is heat treatment at 100~250°C, and high-temperature tempering, which is heat treatment at 600~750°C. Low-temperature tempering is performed in the application environments where hardness is important and it relieves internal stress and reduces brittleness [

10,

11,

12]. On the other hand, high-temperature tempering decomposes martensite and forms coarse precipitation carbides, making it applicable to the environments where toughness and ductility are important. As mentioned the above conventional cast MSS 410 material, its applications and heat treatment processes are well defined and reported to be utilized in industrial needs [

13,

14].

Recently, Ro et al. [

15] reported the scatter in mechanical properties, especially the toughness. And it is correlated to microstructural heterogeneity in MSS 410 fabricated using arc-based additive manufacturing due to the formation of δ-ferrite in the deposition body. Meanwhile, Zhu et al. [

16] developed MSS 410 large-size block part without the defect of δ-ferrite precipitation using appropriate processing parameters via cold metal transfer wire-arc additive manufacturing. Nezhadfar et al. [

17] reported the microstructure and crystallographic texture of 17-4 PH stainless steel with laser powder directed energy deposition in both non-heated and heat treated conditions. They found that fine ferrite grains along with lath martensite, but coarse ferrite along the grain boundaries were observed.

However, there have been a few 3D printing LP-DED additive manufacturing researches available on the MSS 410 and not much investigated in regard to additive manufacturing δ-ferrite-free-MSS 410. In this study, we researched on the MSS 410 fabricated by LP-DED additive manufacturing to analyze the effects of the microstructures and mechanical properties of LP-DED MSS 410 deposits before and after post heat treatment. In addition, the phase transformation and carbide precipitation were also investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Additive Manufacturing

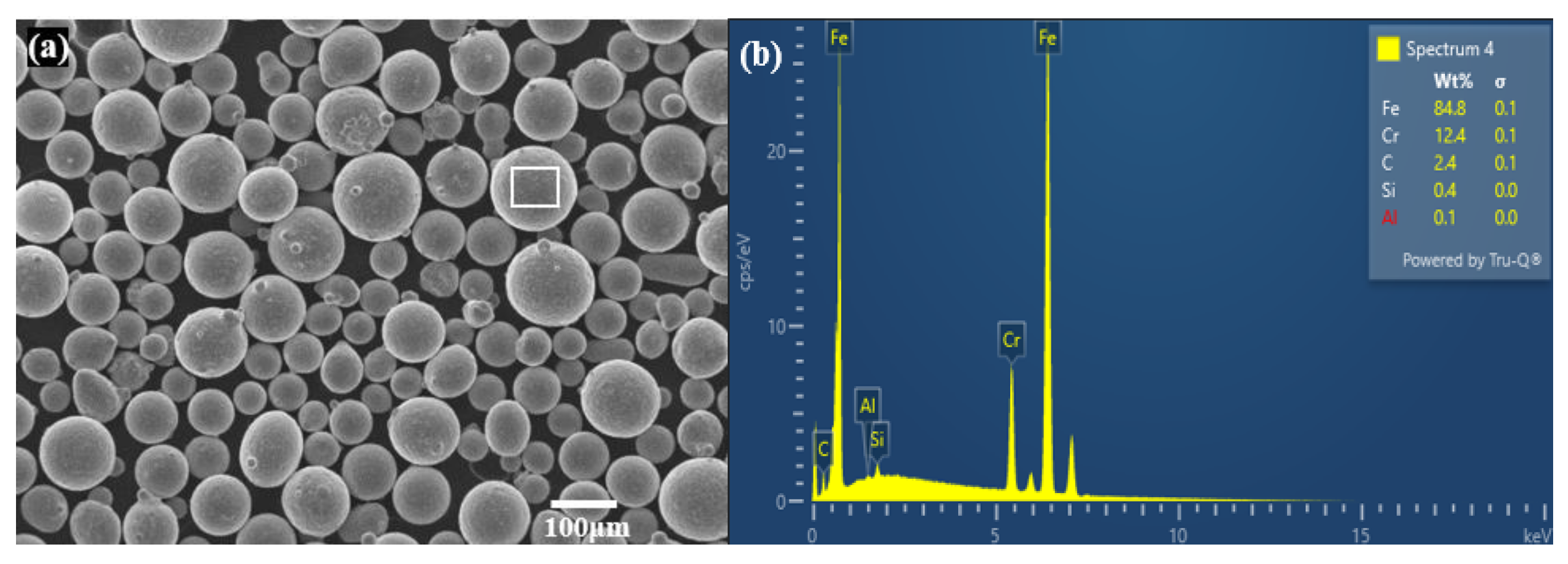

The integrated LP-DED equipment of a CNC machining center assembled with Optomec's LENS(USA) deposition head with beam size of 800um was used for additive manufacturing of the MSS 410. The feedstock material of the MSS 410 powder was manufactured using electrode induction gas atomization (EIGA) process by KOSWIRE(Korea). For sample fabrication, the powder with particle sizes of 45-150um was employed as shown in

Figure 1.

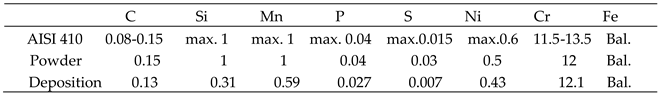

The chemical compositions of the present developed powder and its deposition are indicated in

Table 1, confirming compliance with the AISI 410 standard specification.

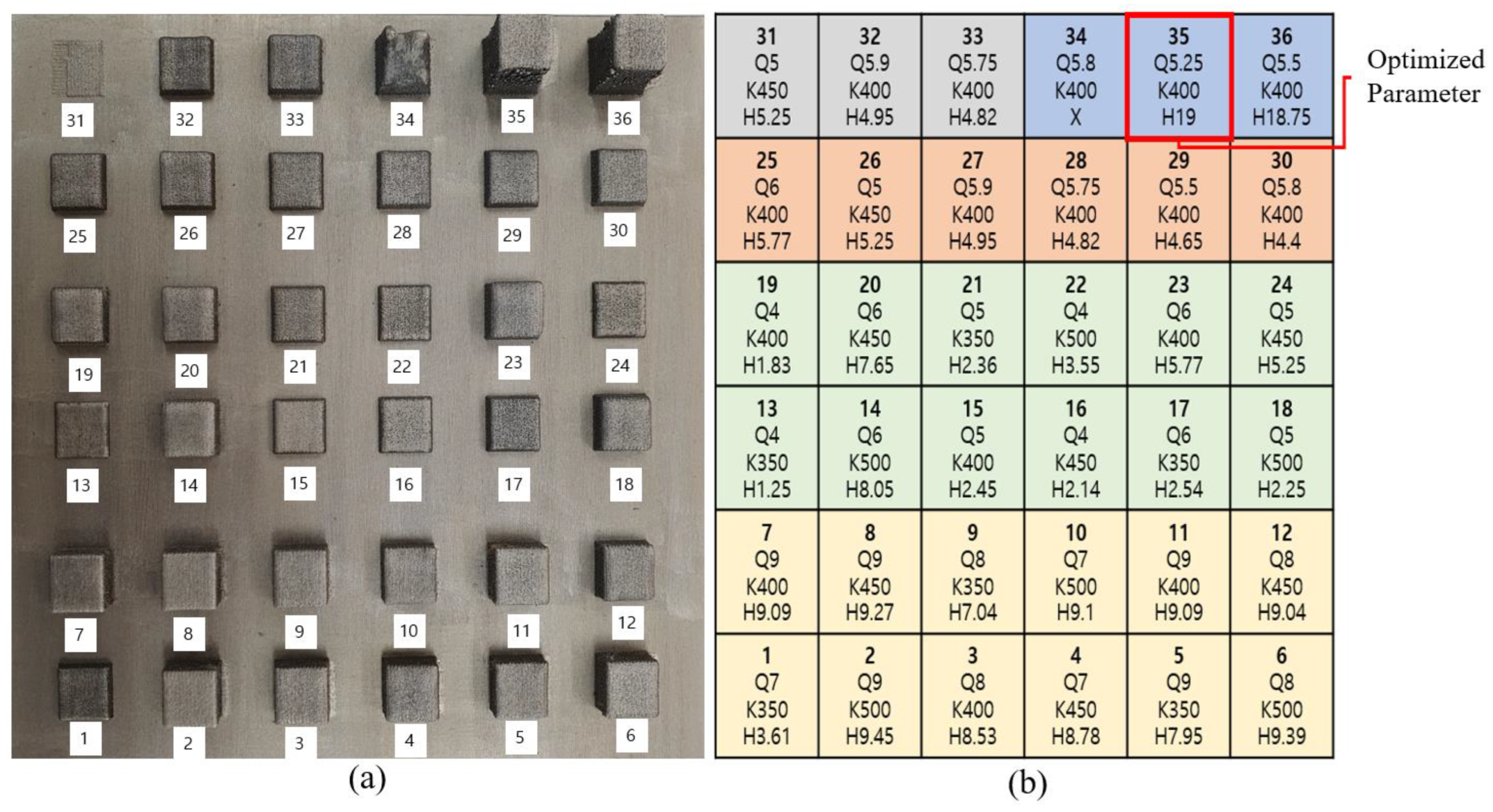

For the preliminary experiments as seen in

Figure 2, we conducted total 36 trial tests with 5 groups to find an optimal condition before producing mechanical characterization samples.

Figure 2a shows the deposition cubes with different experiment parameters such as laser power, travel speed, powder feed rate, hatch distance, layer thickness.

Figure 2b shows 5 groups of laser deposition strategies in this work as follows:

1st Group : explored 12 conditions combining 4 different laser powers (K350, K400, K450, K500, respectively) and 3 different powder feed rates (Q7, Q8, Q9).

2nd Group : deposited over the setting height of 5 mm and investigated 12 conditions again by re-conditioning 3 different powder feed rates (Q4, Q5, Q6).

3rd Group : explored only powder feed rates (Q5, Q6) precisely.

4th Group : deposited the cube height of 5mm again.

5th Group : set and deposited the cube target height of 15 mm and investigated the validity of the optimal conditions.

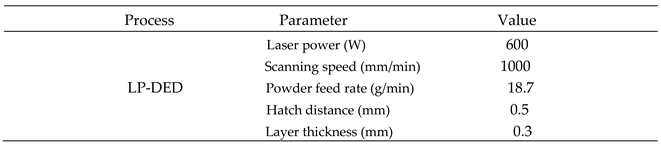

Here, K and Q are factors corresponded to laser power and powder feed rate, respectively. H is the height of the deposited cube. Finally, the optimized LP-DED process parameters obtained from the preliminary experiments are listed in

Table 2. AISI 1045 carbon steel with 200W x 200L x 30H mm was used as a substrate to prevent from deformation during the laser beam deposition.

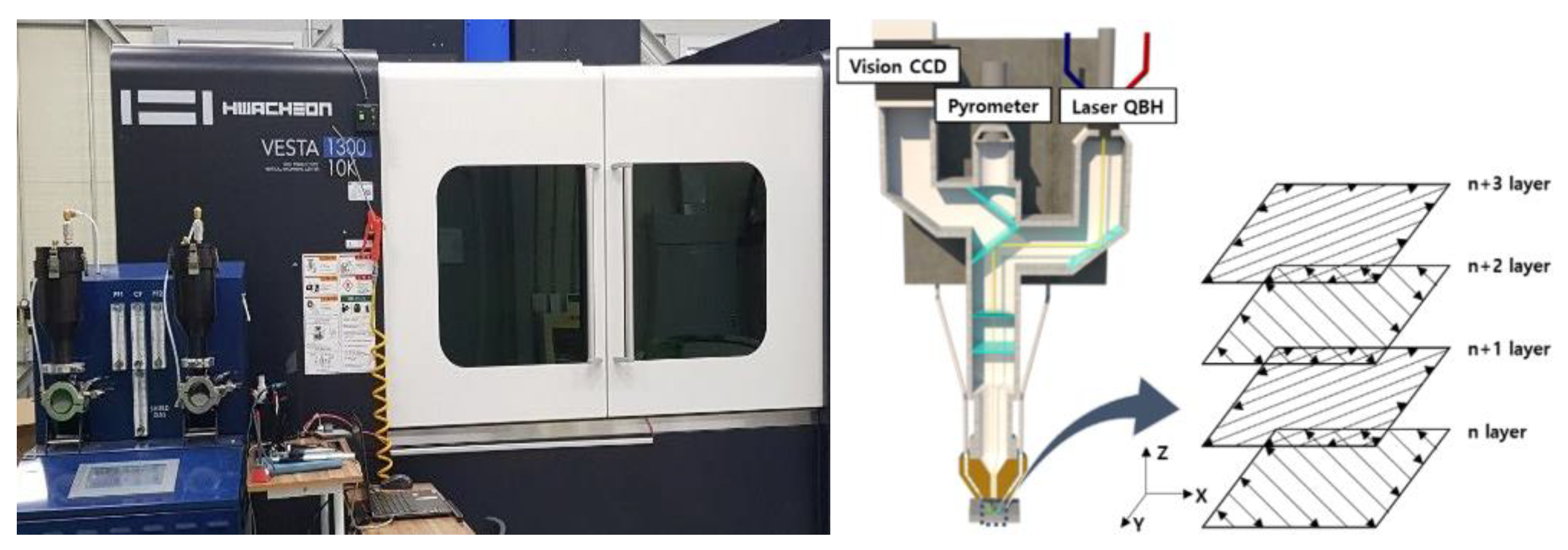

The laser deposition strategy was developed with bidirectional scanning, alternating the laser scanning path by 90° layer by layer, to reduce the anisotropy associated with both microstructures and mechanical properties of the deposition planes as shown in

Figure 3.

2.2. Post-Heat Treatment

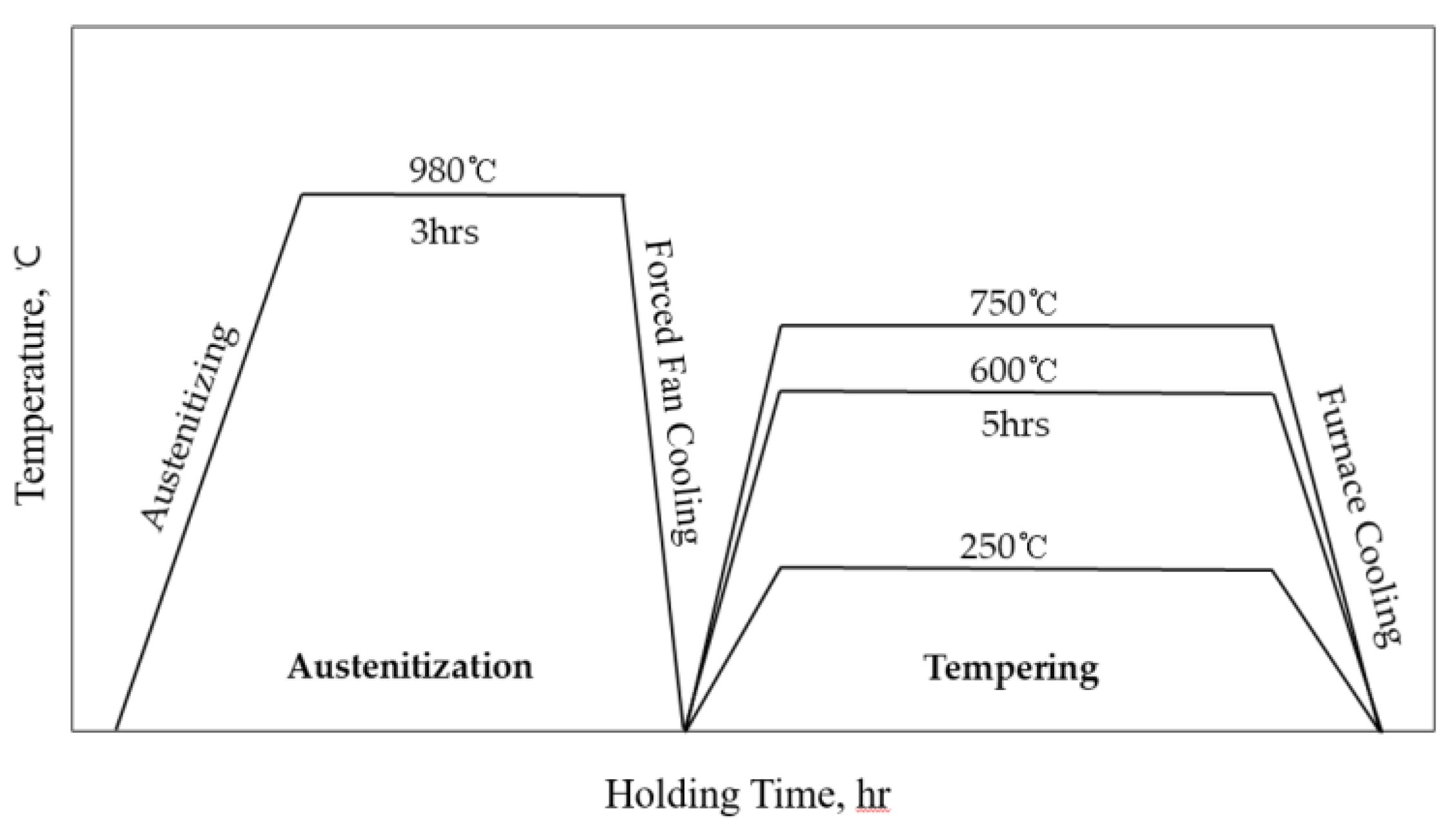

The prepared LP-DED MSS specimens (18 x 18 x 150 mm) underwent the post heat treatments to characterize microstructure, phase transformation, and mechanical property compared with as-built as seen in

Figure 4. The specimens were austenitized at 980°C for 3hrs at a heating rate of 2.3°C/min and followed by forced fan cooling down to 100°C at cooling rate of 22°C/min. and then tempered at 250, 600, 750°C, respectively, for 3hrs followed by furnace cooling.

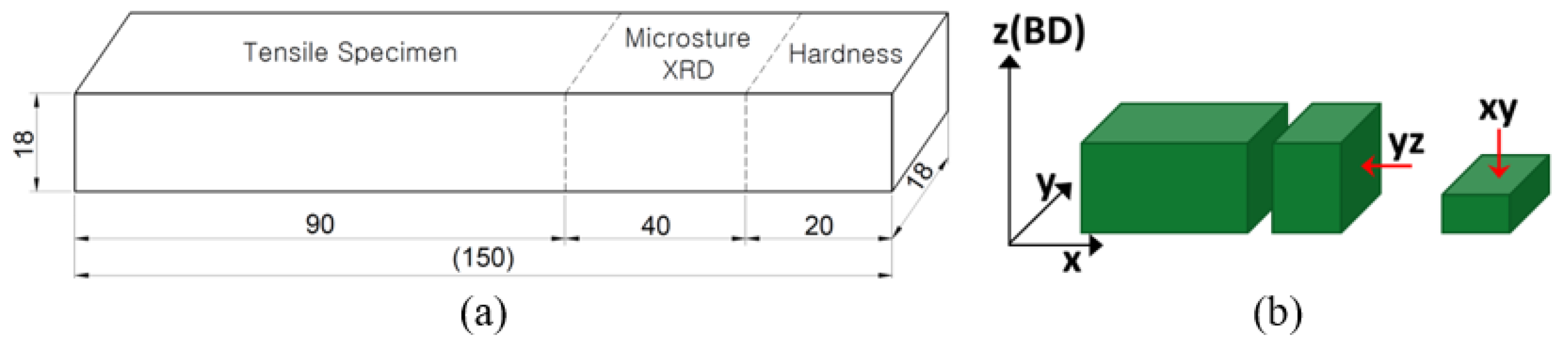

2.3. Characterization of As-Built and Post Heat Treatment Samples

For the characterization of the LP-DED MSS 410, the post heat treatment samples were mainly cut into 3 pieces for the tensile tests, microstructures and X-ray diffractions, and hardness as seen in

Figure 5a. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses of as-built and post heat treatment samples were carried out using an in situ X-ray diffractometer (EMPYREAM, Malvern Panalytical Co.) with Cu Kα radiation. Continuous mode with step size of 0.013°, a scan rate 0.05°/s, 2θ ranging from 30° to 90°, and power of 30mA, 40kV was applied to investigate phase transformation on the samples. The LP-DED samples were also cut into planes parallel (XY) and vertical (YZ) to the longitudinal deposition direction (X) for the microstructural observation as seen in

Figure 5b.

The metallographic samples for SEM-EDS were prepared cautiously by polishing with a 1um diamond suspension and then etched with an aqueous solution (100 ml C2H5OH + 5 ml HCl + 3g C6H3N3O7). Subsequently, electrolytic polishing was conducted in a solution (90ml Methyl alcohol + 10ml perchloric acid) and conditions of 28 volts and 90 seconds to achieve a refined surface state for electron back scatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis. The microstructures were characterized by SEM-EDS and EBSD. Vickers microhardness measurements were performed using a digital microhardness tester with a 1.0kg load for 10 second dwell time on the polished planes parallel and perpendicular to the longitudinal deposition direction in order to investigate the anisotropic texture structure disposition caused by laser scan direction-originated solidification of melt pool. Tensile tests for as-built and post heat treatment samples were performed at the crosshead speed of 1 mm/min and room temperature in accordance with the specifications of round bar specimen No.3 in the ASTM E8 standard using a universal test machine (Intstron 100kN).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phase Analysis

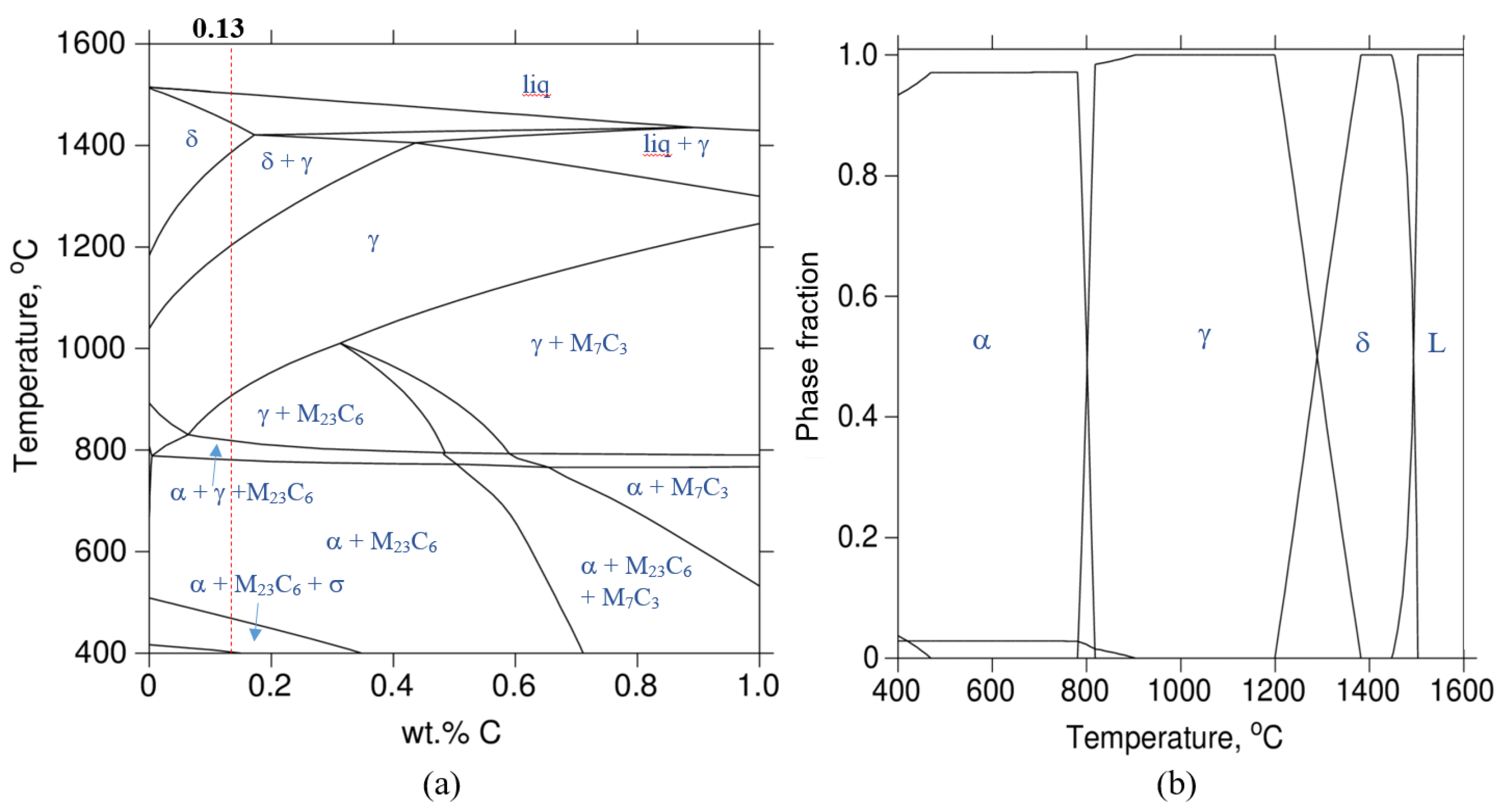

3.1.1. Phase Equilibrium

Figure 6 shows the binary Fe-C phase diagram and phase fraction of LP-DED MSS 410 with 12wt.% Cr and maximum carbon content of 0.2wt.%, which were composed by Thermo-Calc

TM software calculating with the input chemical composition of the deposition shown in

Table 1.

When the LP-DED MSS 410 deposition rapidly transforms at the temperatures of between about 900 and 1100°C from above the liquidus temperature at the carbon content of 0.13wt.%, the LP-DED MSS 410 material is subject to transform in a trice to austenite through several phase transformations from the liquid state. And solidification continuously and rapidly proceeds, martensite is predominant, which consists of ferrite and carbide. Meanwhile, the chromium carbide (Cr23C6) starts to precipitate from the temperature of 950°C and becomes stable below 800°C.

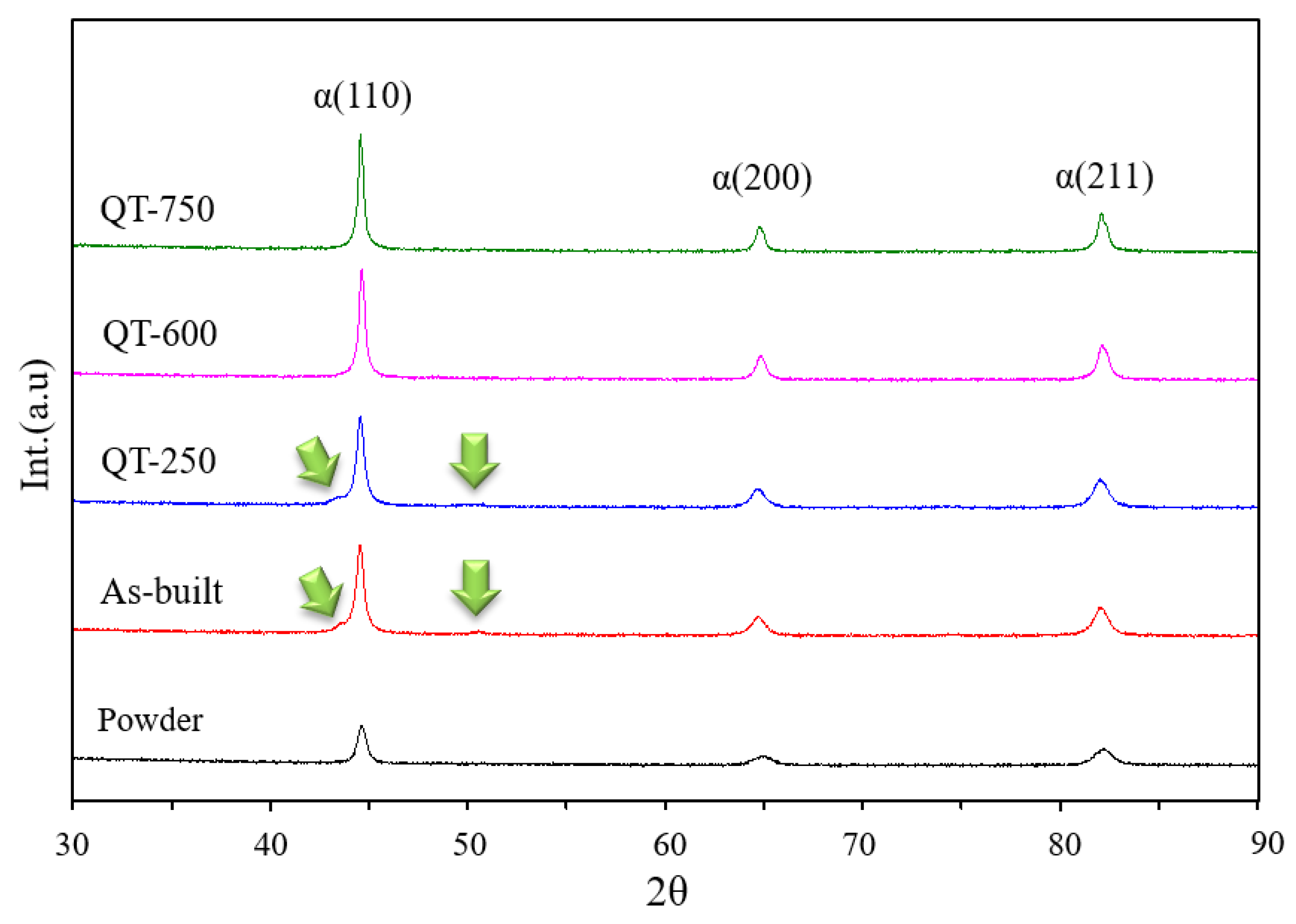

3.1.2. X-ray Diffraction Analysis

The XRD analyses of LP-DED MSS 410 samples with as-built and the different tempering treatments after austenitizing at 980

°C for 3hrs are shown in

Figure 7. The crystalline LP-DED MSS 410 diffraction peaks were identified as the three major martensite peaks with a BCC structure (110), (200) and (210) by the good agreement of JCPDS cards of 96-901-3476(Fe 2.00) and 96-901-4057(Fe 4.00). These X-ray diffraction peaks are also in good agreement with Lu et al. [

18]’s research. The MSS 410 feedstock powder has the lowest peak intensity due to the rapid quenching from the typical electrode induction gas atomization process, which argon gas blows the metal melt [

19]. It is well known that the high-cooling rates of DED AM process of 10

2 ~ 10

3K/s are attributed to the peak intensities, depending on the process parameters, especially the scan speed [

20,

21].

It was revealed that there were somewhat residual stresses in the samples of as-built and QT-250 which imply the broad peaks. Especially, the retained austenite was existed, pointing green arrows on as-built and QT-250. For as-built sample, the residual stress and the retained austenite are considerably attributed to the rapid quenching during additive manufacturing. After tempering at 600 and 750°C, the residual stresses disappeared and became the sharp peaks, releasing the residual stresses. Moreover, the retained austenite was not observed.

3.2. Microstructural Investigation

3.2.1. SEM-EDS Analysis

Figure 8 shows the SEM images of LP-DED MSS 410 with different post heat treatments. The lath martensite and incredibly small carbide precipitation with the red arrows were seen in as-built microstructures of

Figure 8e,m. It implies that the phase transformation was developed through the rapid solidification sequence of the phase: L→ L+γ→ γ+M

23C

6→α+γ+M

23C

6.

The microstructures of tempering at 250°C illustrates the lath martensite and initial growth tempered martensite, showing somewhat uniform distribution of tiny carbides within the developed lath martensite as seen in

Figure 8b,f,j,n. However, the lath martensite microstructures gradually decomposed after tempering heat treatment of 600°C and the tempered martensite grew coarser than that of tempering at 250°C. In addition, most carbides, pointed by red arrows, aggregated and precipitated within the lath boundaries and along with the prior austenite boundaries over the tempered martensite, and the irregular and long-spun carbide size increased as shown in

Figure 8c,g,k,o. Compared to the microstructures of tempering at 600°C, more carbides with somewhat spherical shapes, pointed by red arrows, predominantly precipitated in the vicinities of the tempered martensite boundaries. Almost the same carbide precipitates within laths as well as along with lath boundaries after tempering at 923K were reported by Chakraborty et al. [

7]

Figure 9 shows the analyses of the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy(EDS) on the precipitates with different tempering temperatures. The base material of LP-DED MSS 410 was confirmed as the main chemical compositions of Fe, C, Si, Mn, Cr, Ni as seen in

Table 1. The EDS analyses of the as-built shows that the precipitates contain mainly 1.04wt.% carbon, 12.24wt.% chromium and 85.32wt.% iron as seen in

Figure 9a,b, and its chemical composition table, speculating the precipitates as the carbides (Fe

2C, (Cr, Fe)

23C

6). Compared to the as-built for austenitizing at 980°C for 3hrs, tempering at 250°C for 5hrs reveals that the chemical composition a little bit increased to 1.56 wt.% carbon and 12.39wt.% chromium, respectively, but iron content decreased to 84.46wt.% from 85.32wt.% as shown in

Figure 9c,d, and its chemical composition table. It seems that the tempering heat treatment process appears to have favorably activated the reactions between chromium, iron and carbon together. As a result, both Fe

2C and M

23C

6 carbides would possibly be formed as Chakraborty et al. [

7]. Furthermore, more carbides precipitated at the tempering temperature of 600°C compared to that of 250°C, concentrating most carbides at the grain boundaries and chrome contents are greater than that of tempering at 250°C to 14.47wt.% from 12.39wt.% by gradually decreasing iron contents as seen in

Figure 9i,j, and its chemical composition table. As shown in

Figure 9m,n, and its chemical composition table, tempering at 750°C shows the fully developed Cr-rich M

23C

6 carbides with 4.39 wt.% carbon, 20.64 wt.% chromium and 73.61wt.% iron. It was revealed that the contents of carbon and chromium increased as the tempering temperature increased, which is more favorable to form the carbide of Cr

23C

6 rather than that of Fe

2C. A similar observation was researched with tempering at 732°C for AISI martensitic stainless steel 410 by Godbole et al. [

22].

3.2.2. EBSD Analysis

EBSD phase maps, image quality (IQ) maps, inverse pole figure (IPF) maps, and kernel average misorientation (KAM) maps of perpendicular (YZ) planes of the as-built, QT-250, QT-600, and QT-750 samples are shown in

Figure 10. In the as-built specimen, about 0.7% of retained austenite was observed, but after austenitization and tempering treatment, the amount of retained austenite in the QT-250, QT-600, and QT-750 samples decreased to 0.1% as shown

Figure 10a. The decrease in the amount of retained austenite results from carbide formation, which occurs when the supersaturated carbon within the martensite diffuses out to form carbides during the tempering treatment. The increased size of lath martensite after tempering treatment can be confirmed qualitatively through the IQ map. The increased values can be quantitatively confirmed through the IPF map in

Figure 10c. Compared to the as-built specimen, the size of prior austenite in QT-250, QT-600, and QT-750 has increased after austenitization heat treatment, and the size of lath martensite showing a misorientation within 15° has also increased in QT specimens compared to the as-built. Additionally, it can be confirmed that the KAM value, i.e., residual strain, is relieved as the tempering temperature increases after austenitization heat treatment as shown in

Figure 10d. No evidence of δ-ferrite was observed in the KAM map.

3.3. Mechanical Property Characterization

3.3.1. Hardness Test

Figure 11 shows the Vickers hardness of LP-DED MSS 410 samples with different post heat treatments. It was revealed that the anisotropies of the Vickers hardness between parallel- and vertical-to-the deposition were observed in the samples of as-built and QT-250. It is apparent that these anisotropies are considerably attributed to the microstructural anisotropies as shown in

Figure 8. During depositing the MSS feedstock powder with the high scanning speeds of 1000 mm/min, the melt pool quickly solidifies onto the substrate in layer-by-layer. As a result, the solidification rates are different from top layer to bottom layer. It was a very good trial to set the hardness test condition with the greater load of 1kg rather than 300g as usual to validate the anisotropies of microstructures and mechanical properties as well. After austenitizing at 980°C and tempering the sample at 250°C, these anisotropies gradually decreased, but the lower tempering temperature could not dissolve the deposition layers to uniform ones by recrystallizing the unstable and anisotropy microstructures. The isotropy, however, became prevalent after tempering at 600 and 750°C, bringing the fully tempered microstructure with the homogeneous and coarse carbide precipitates in the vicinities of the prior austenite grain boundaries and lath boundaries. As a result, the reduction in the Vickers hardness was accompanied with the tempering temperatures which activate the nucleation and recrystallized grain growth incorporated with the Arrhenius equation as below.

k is rate constant, T is absolute temperature, A is pre-exponential.

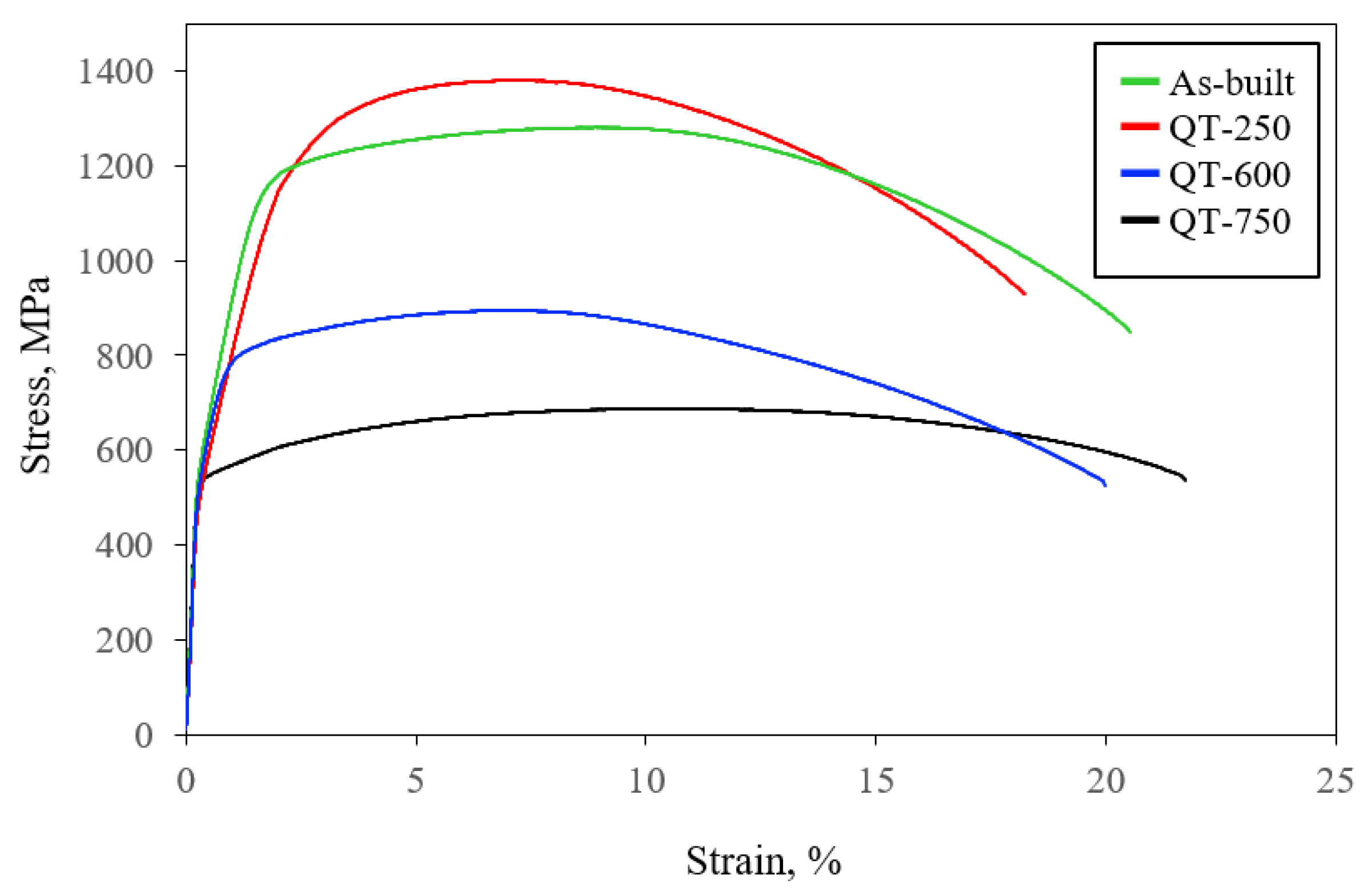

3.3.2. Tensile Test

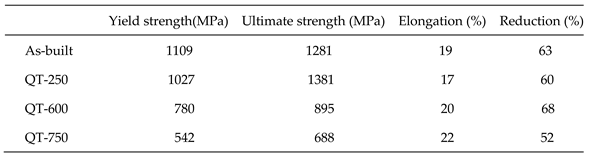

Figure 12 shows the tensile properties of the LP-DED MSS 410 samples with different post heat treatments. The yield strength, tensile strength, and elongation of as-built samples are 1109MPa, 1281 MPa, 19%, respectively. These as-built tensile properties have a little higher values compared to wire-arc based AISI 410 additive manufacturing performed by Roy et al. [

14]. It seems that the fine grains and the residual stress by rapid solidification during additive manufacturing lead to an increase in tensile strength. However, the as-built and QT-250 samples show comparable values in tensile strength.

This can be attributed to recovery processes during the relatively low tempering treatment at 250°C within the martensite formed through fan cooling subsequent to an austenitization treatment. This treatment leads to a reduction in dislocation density, resulting in a slight decrease in yield strength. It is noteworthy that the Vickers hardness in perpendicular to deposition direction at tempered at 250°C was greater than that of as-built which can have the higher tensile strength. Compared to QT-750, the tensile property of QT-600 was greater due to finer grain size of 8.5±6.7um and higher residual strain value of KAM=1.17° as shown in

Figure 10.

Table 3.

Comparison of tensile properties of the LP-DED MSS 410 samples.

Table 3.

Comparison of tensile properties of the LP-DED MSS 410 samples.

4. Conclusion

Martensitic stainless steel 410 samples were produced by the laser powder-directed energy deposition and then the samples underwent various post heat treatments. The following conclusions can be drawn from this study:

- (a)

The three major martensite peaks with a BCC structure (110), (200) and (210) were observed in all of the samples of as-built, QT-250, QT-600, and QT-750.

- (b)

Some residual stresses and retained austenite in the samples of as-built and QT-250 were observed by X-ray diffraction analysis and EBSD.

- (c)

The lath martensite microstructures decomposed after tempering treatment of 600°C and the tempered martensite grew coarser. In addition, most carbides aggregated and precipitated in the vicinities of the prior austenite grain boundaries and lath boundaries.

- (d)

The contents of carbon and chromium increased as the tempering temperature increased, which is more favorable to form the carbide of Cr23C6 rather than that of Fe2C.

- (e)

The decrease in the amount of retained austenite results from carbide formation, which occurs when the supersaturated carbon within the martensite diffuses out to form carbides during the tempering treatment.

- (f)

The anisotropies of the Vickers hardness between parallel- and vertical-to-the deposition were observed in the samples of as-built and QT-250. These anisotropies are considerably attributed to the microstructural anisotropies.

- (g)

The fine grains and the residual stresses by rapid solidification during additive manufacturing lead to an increase in tensile strength of the as-built compared to the different post heat treatments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K.; methodology, H.L.; formal analysis, C.O.; investigation, H.K. and H.L.; resources, J.Y.; data curation, H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, H.K.; visualization, H.K.; supervision, H.K.; project administration, H.K.; funding acquisition, H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by SME Innovation Technology Development Project from the Ministry of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises and Startups, Korea, grant number RS-2023-00220876.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vafadar, A.; Guzzomi, F.; Rassau, A. ; Advances in Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Common Processes, Industrial Applications, and Current Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Mohd Yusu, R.; Zulkifli, N.; Megat Ahma, M. Effective factors on advanced manufacturing technology implementation performance: A review. J. Appl. Sci. 2010, 10, 1229–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citarella, R.; Giannella, V. Additive Manufacturing in Industry. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofail, S.A.M.; Koumoulos, E.P.; Bandyopdhyay, A.; Bose, S.; O’Donoghue, L.; Charitidis, C. Additive Manufacturing: Scientific and Technological Challenges, Market Uptake and Opportunities. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiyama, T.; Tobata, J.; Tao, T.; Nakata, N.; Takaki, S. Quenching and partitioning treatment of a low-carbon martenitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 352, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.J.; Crowe, D.J.; Pickering, F.B. Metallurgical Evolution of Stainless Steels. American Society for Metals 1979, 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, G.; Das, C.R.; Albert, S.K.; Bhaduri, A.K.; Thomas Paul, V.; Panneerselvam, G.; Dasgupta, A. Study on tempering behavior of SISI 410 stainless steel. Mater. Char. 2015, 100, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonagani, S.K.; Vishwanadh, B.; Tenneti, S.; Naveen, K.N.; Vivekanand, K. Influence of tempering treatments on mechanical properties and hydrogen embrittlement of 13 wt% Cr martensitic stainless steel. Inter. J. Pre. Ves. Pip. 2019, 176, 103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbole, K.; Das, C.R.; Joardar, J.; Albert, S.K.; Ramji, M.; Panigrahi, B.B. Toughening of AISI 410 Stainless Steel Through Quenching and Partitioning and Effect of Prolonged Aging on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Metall. Mater. Tran. 2020, 15A, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaeee, M.; Momeni, A.; Keshmiri, H. ; Effect of quenching and tempering on microstructure and mechanical properties of 410 and 410 Ni martensitic stainless steels. J. Mater. Res. 2017, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, A.; Richard, C.; Igual-Munoz, A. Degradation mechanism in martensitic stainless steel: Wear, corrosion and tribocorrosion appraisal. Trib. Int. 2018, 121, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.A.; Gheisari, K.; Moshayedi, H.; Warchomicka, F.; Enzinger, N. Basic alloy development of low-transformation-temperature fillers for AISI 410 martensitic stainless steel. Sci. Tech. Weld. Join. 2020, 25, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-T.; Liu, F.-M.; Hou, W.-H. Application and Characteristics of Low-Carbon Martensite Stainless Steels on Turbine Blades. Mater. Tran. 2015, 56, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Shassere, B.; Yoder, J.; Nycz, A.; Noakes, M.; Narayanan, B.K.; Meyer, L.; Paul, J.; Sridharan, N. Mitigating Scatter in Mechanical Properties in AISI 410 Fabricated via Arc-Based Additive Manufacturing. Mater. 2020, 13, 4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, J.M. .; Pereira, M.; Cruz, J.R.; Jứnior, A.T.; Ferreira, H.S.; Gutjahr, J. Influence of post-processing heat-treatment on the mechanical performance of AISI 410L stainless steel manufactured by the L-DED process. H. J. Laser Appl, 2023; 35, 42056. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.; Lin, J.; Lei, Y.; Sun, Q.; Cheng, S. Additively manufactured δ-ferrite-free 410 stainless steel with desirable performance. Mater. Let. 2021, 293, 129579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhadfar, P.D.; Gradl, P. R.; Shao, S.; Shamsaei, N. A comparative study on the microstructure and texture evolution of L-PBF and LP-DED 17-4 PH stainless steel during heat treatment. Solid Freeform Fabrication 2021: Proceedings of the 32nd Annual International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium – An Additive Manufacturing Conference, 2021. 902-914.

- Lu, S.-Y.; Yao, K.-F.; Chen, Y.-B.; Wang, M.-H.; Shao, Y.; Ge, X.-Y. Effects of austenitizing temperature on the microstructure and electrochemical behavior of a martensite stainless steel. J. appl. Electrochem. 2015, 45, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Zhang, H.-B.; Chen, S.-M.; Zhang, L.-J.; Na, S.J. Intensive laser repair through additive manufacturing of high-strength martensitic stainless steel powders (I) –powder preparation, laser cladding and microstructures and properties of laser-cladded metals. J. Mater. Res. Tech. 2021, 15, 5746–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshidianfar, M.H.; Khajepour, A.; Gerlich, A.P. Effect of real-time cooling rate on microstructure in laser additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2016, 231, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshidianfar, M.H.; Khodabakhshi, F.; Khajepour, A.; Gerlich, A.P. closed-loop control of microstructure and mechanical properties in additive manufacturing by directed energy deposition, Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2021, 803, 140483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbole, K.; Panigrahi, B.B.; Das, C. Tailoring of mechanical properties of AISI 410 martensitic stainless steel through tempering. Metal 2017, 707–710. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).