1. Introduction

Worldwide, biomass represents a primary carbon source, together with other renewable energy sources. According to the definition provided by directive 2009/28/CE, “

biomass means the biodegradable fraction of products, waste and residues from biological origin from agriculture (including vegetal and animal substances), forestry and related industries including fisheries and aquaculture, as well as the biodegradable fraction of industrial and municipal waste”. Biomass can is a raw material for producing energy, biofuels with high energy value or biochemical fuels, used in different economic activities. To date, according to recent reports, biomass contributes with over 14% to the production of primary energy, while in the developed states it represents 40-50% of the energy requirement [

1,

2].

As it is well known, biomass is a material of organic origin, generated by plants during their development, as a result of the photosynthesis processes. In the photosynthesis process, plants assimilate the carbon dioxide emissions produced by the combustion of other plants, in a closed cycle. As a result, the use of biomass for energy purposes leads to carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere, which will be then used by plants for producing new quantities of biomass [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Moreover, biomass is the only renewable resource that can be used directly through combustion [

8].

The energy provided by renewable sources has a significant social and economic impact because it encourages and promotes the growth of the local industry, creates new jobs, fulfils the energy demands both locally and internationally [

9]. Moreover, worldwide researches show that the emissions of greenhouse gases are significantly lower when biofuels are used in order to produce energy, compared with the ones generated by the combustion of coal [

10]. It is for this reason that the specialized literature mentions that biomass is nearly neutral with regard to carbon dioxide emissions and that it is available from a large variety of resources [

10].

Biomass has many advantages as an energy source because it may be used both for producing power and heat and for obtaining a large variety of combustible products: liquid fuels for the internal combustion engines used in transportation, solid and gaseous fuels etc.

Biomass, as a raw material, is present under different forms and is abundant on Earth. However, in reality, natural biomass is not very used as an energy source due to some unfavorable characteristics such as low bulk density, high humidity ratio, low calorific value per unit volume, thus leading to higher transport, storage and manipulation costs [

11]. In order to improve these characteristics, the biomass feedstock undergoes several mechanical or chemical processes. As an example mechanical processing (densification) of biomass as pellets and briquettes leads to valuable biofuels, with high energy value per unit volume, with high density and hardness, thus enabling a significant reduction of the transport, storage and manipulation costs; in the same time, this allows the automation of the installations used for producing thermal energy through combustion [

12,

13,

14,

15,

17].

Researches emphasize the fact that biomass densification is achieved with significant energy consumption, that depends on the nature and humidity of the raw material, the densification technology, characteristics of the final product etc. [

11,

14]. From this point of view, it was proven that the smaller the mass particles are, the higher is the energy consumption due to the friction at the contact with the surfaces of the active parts of the densification equipment [

16]. Moreover, when the dimensions of the biomass particles exceed the acceptable limit, the densification process is slowed down, especially when producing pellets, as the matrix holes may become clogged.

On the other hand, the use of low capacity equipment and of higher densification pressures than the ones recommended by the respective technology result in significant increases of the energy consumption because some of it is converted into heat, without any significant improvement in the quality of pellets or briquettes [

17,

18,

19]

Taking into account all these aspects it may be concluded that the quality of the densified biomass depends on both the nature of the raw material and the parameters of the briquetting process. For these reasons, both the calorific value (which should be comprised between 17 MJ·kg

−1 and 20 MJ·kg

−1 [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]) and the composition (which should correspond to the requirements of the ISO 17225-3:2021 standard) are considered when evaluating the quality of the briquettes

As the worldwide requests for densified biomass are continuously increasing, new variants for producing thermal and electric energy from renewable resources are studied. This is the reason why biomass produced from the yearly winter pruning of vines is gaining an increased attention.

Vine is a lignified perennial plant, grown worldwide on over 7.4 million ha (in 2022) [

13] due to its economic importance; this figure is also confirmed by the statistics of International Organization of Vine and Wine. The large interest for growing vines in the temperate climate is due to the fact that it can be cultivated on slopes and sandy soils, on less fertile areas and unsuited for other agricultural purposes.

Vines need yearly winter pruning, which results in large quantities of biomass containing lignocellulose, that might be used for producing densified biofuels. This biomass consists of a mixture of tendrils and stems of different lengths, with a diameter up to 40 mm, in quantities reaching 1.5…2.5 t·ha

−1, and a humidity ratio of 40…50% [

12,

26,

27]. Presently, in most of the plantations, this biomass mixture is either chopped and left as mulch between the vine rows (thus raising phytosanitary risks) or is collected and transported away from the vine area, where it is burned into the open air, thus creating negative effects over the environment (emissions of particles into the atmosphere) [

28].

Some of the plantations, especially the large vineyards from Europe, use technologies that convert the biomass into chips, pellets or briquettes, thus contributing to the sustainable development of the countryside areas [

29,

30].

Although biomass from vine pruning might constitute a significant resource for producing renewable energy, with the potential to produce over 7 mil. tones of biofuel, some of its characteristics limit its valorization: seasonal availability (only when pruning takes place); significant costs for transport and manipulation (as vines are placed in limited areas); low efficiency of solar radiation conversion to biomass; high humidity ratio of the resulted biomass, thus requiring operations and equipment with high energy consumptions; not profitable in low surface plantations [

13].

Despite all the disadvantages mentioned so far, the worldwide researches have proven that this biomass, densified as briquettes, may be a reliable source of renewable energy, that can successfully provide a part of the electric and thermal energy in certain areas [

17,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

The aim of the present paper is to evaluate the sustainability of producing briquettes using vine tendrils resulted from the yearly winter pruning, based on the results provided by the authors’ own research on this matter.

2. Materials and Methods

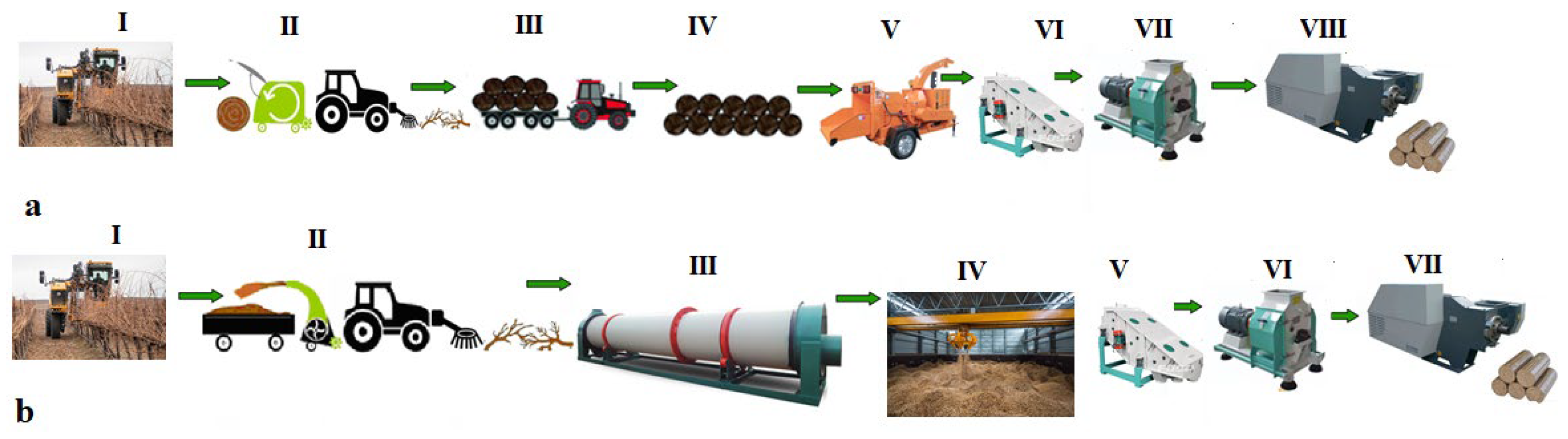

Two technologies were considered with regard to the densification of the biomass resulted from the mechanized pruning of vine: baling and natural drying of the tendrils (

Figure 1a); collection, shredding and artificial drying of the lignocellulose debris (

Figure 1b).

In the case of the first technology (

Figure 1a) the workflow includes the following specific stages: collection of the debris through bailing (II), transportation of the bailed tendrils (III); storage and natural drying of the tendrils (IV); rough shredding of the tendrils (V); sieving and separation of the large particles (VI); grinding of the large particles (VII); briquetting (VIII).

As for the second technology, (

Figure 1b) the workflow consists of the following stages: collection of tendrils through shredding and transport of the debris (II); convective drying of the shredded debris (III); biomass storage (IV); sieving and separation of the large particles (V); grinding of biomass particles (VI); briquetting (VII).

The analysis of the sustainability of briquettes production was based on the following characteristics: yearly quantity of biomass per unit area; calorific value, composition and quality of briquettes and pellets; energy balance for biomass densification and energy efficiency. These indices were evaluated with regard to the vine variety, the harvesting technology and briquettes preparation technology.

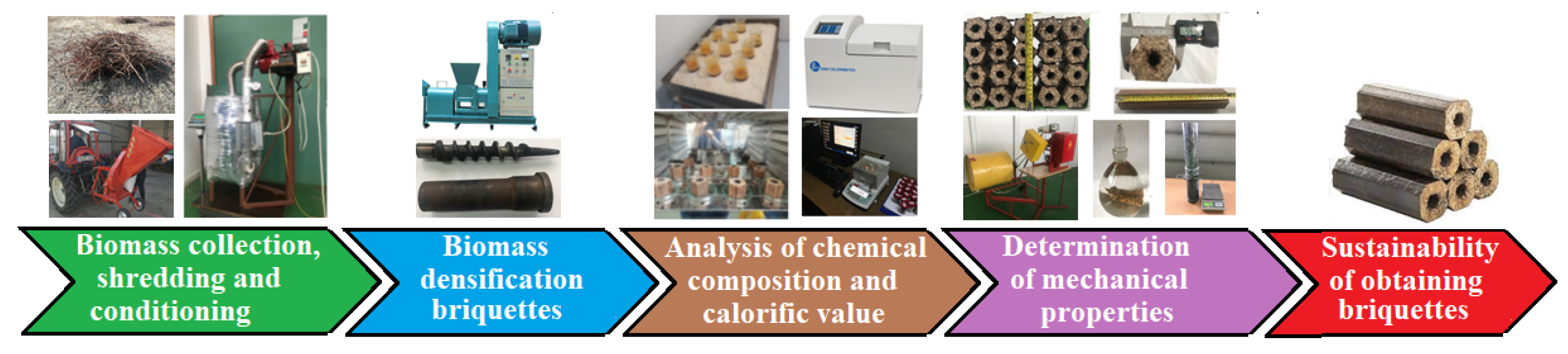

The stages of the research algorithm (

Figure 2) were: collection, shredding and conditioning of the vine tendrils; densification of the biomass as briquettes; chemical analysis of the composition and evaluation of the calorific value for the densified biomass; evaluation of the mechanical properties of the briquettes; sustainability analysis for the production process of the briquettes.

The sustainability analysis for the production of densified biomass from vine tendrils was based on the quality indices, as specified in the ISO 17225-3/2021 standard (which allowed the briquettes to be graded in quality classes) and on the energy balance and energy efficiency, which allowed the evaluation of the overall energy consumption for producing the briquettes, using two different technologies.

The experiments took place in the Agricultural Machinery laboratory of the Iaşi University of Life Sciences; the biomass was harvested from the vineyard located in the "Vasile Adamachi" farm of the university, with the following specifications:

2.1. Collection of the Vine Tendrils

The material for the production of densified biomass was collected from eight vine varieties: Pinot Noir (PN), Muscat Ottonel (MO), Fetească Neagră (FN), Fetească Albă (FA), Fetească Regală (FR), Cabernet Sauvignon (CS), Sauvignon Blanc (SB) and Busuioacă de Bohotin (BB).

The winter pruning was performed manually, with vine scissors; afterwards, the tendrils were gathered and temporally deposited at the end of the plot, where they were labeled according to the variety.

Two indices were taken into account when harvesting the tendrils: the average mass of tendrils per stump, for each variety, and the necessary quantity of biomass for producing the briquettes.

For the first index, the tendrils from five stumps on each row were collected (and from at least five rows for each vine variety); the resulted biomass was weighted using an electronic 10 kg scale (type SKU-BD10TWYD).

For the production of briquettes at least 100 kg of tendrils were collected for each vine variety; the biomass was then transported to the test lab, where the humidity ratio was evaluated. The humidity content of the raw material, shredded material and briquettes was measured using the thermobalance method, by the means of an AGS 210 type humidity analyzer. The method is based on the measurement of weight loss due to water evaporation from the analyzed sample. The sample was heated at 120 °C, under intense air circulation; the flattening of the drying chart has indicated the final drying time [

22].

2.2. Drying of Biomass

In order to densify the collected tendrils, the biomass had to be dried, thus reducing its humidity ratio from 44-46% to 10-12% [

16,

23,

38]. Two drying procedures were used in our experiments: natural and artificial drying.

Natural, passive drying, is a simple method, needing no supplementary equipment and power sources; it was achieved by storing the biomass under a canopy for 90 days, while continuously monitoring the humidity ratio until the necessary value imposed by the densification process was achieved.

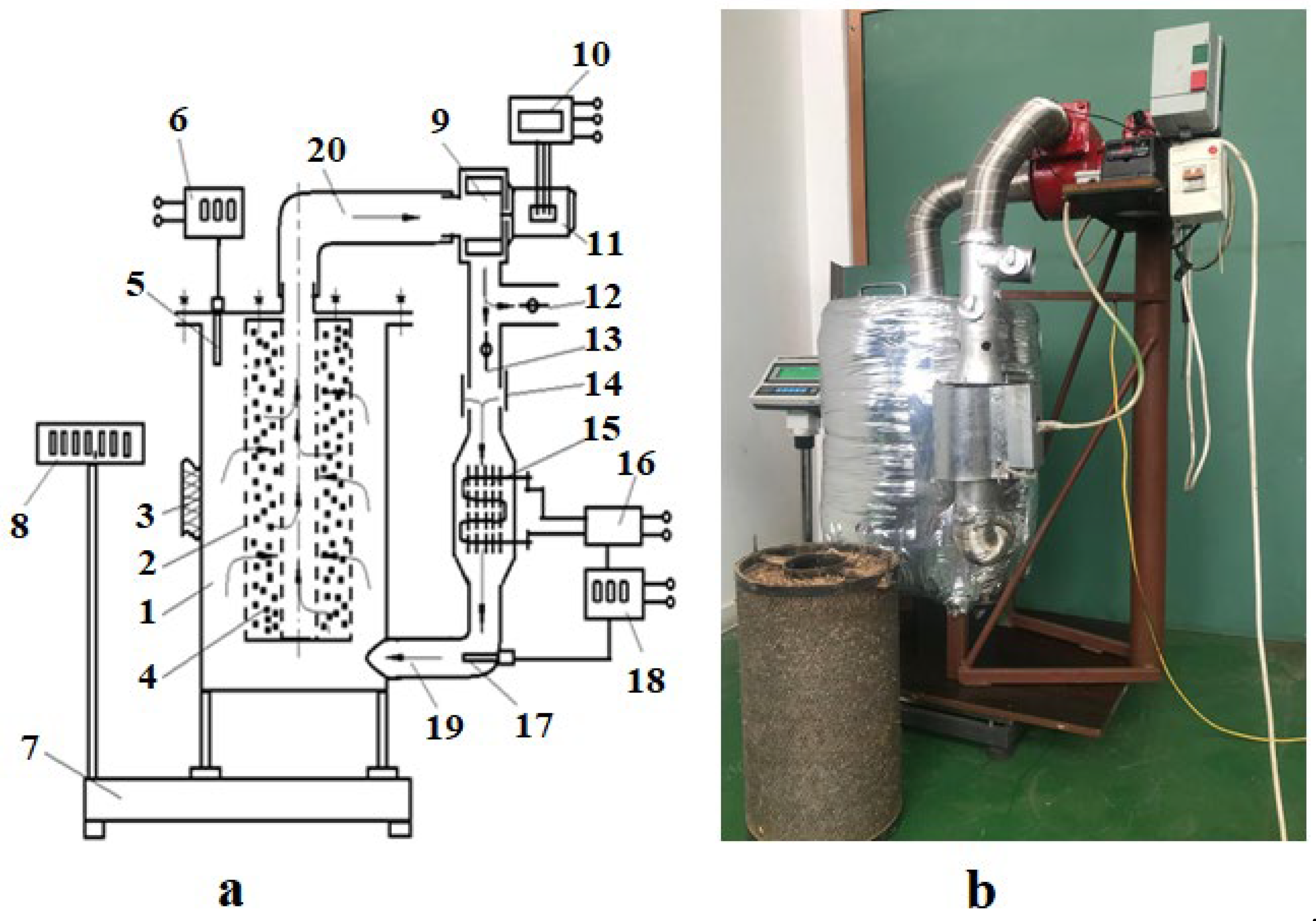

Artificial (convective) drying was performed in laboratory conditions, after the tendrils were shredded, in an original equipment (

Figure 3) which uses hot air as a drying agent. The equipment also allowed the measurement of the energy consumption for drying the biomass [

22].

The drying equipment was fitted with automated devices for monitoring and controlling the air flow and air temperature; an electronic scale was used for measuring the water loss during the operating process. The entire unit is thermally insulated, in order to avoid heat losses.

The convective drying of tendrils was performed at an air temperature of 70 °C and velocity of 1.5 m·s

−1; the duration of the entire process was 200-240 min and the drying velocity was 89-90 [g water·h

−1·kg

−1 biomass] [

38].

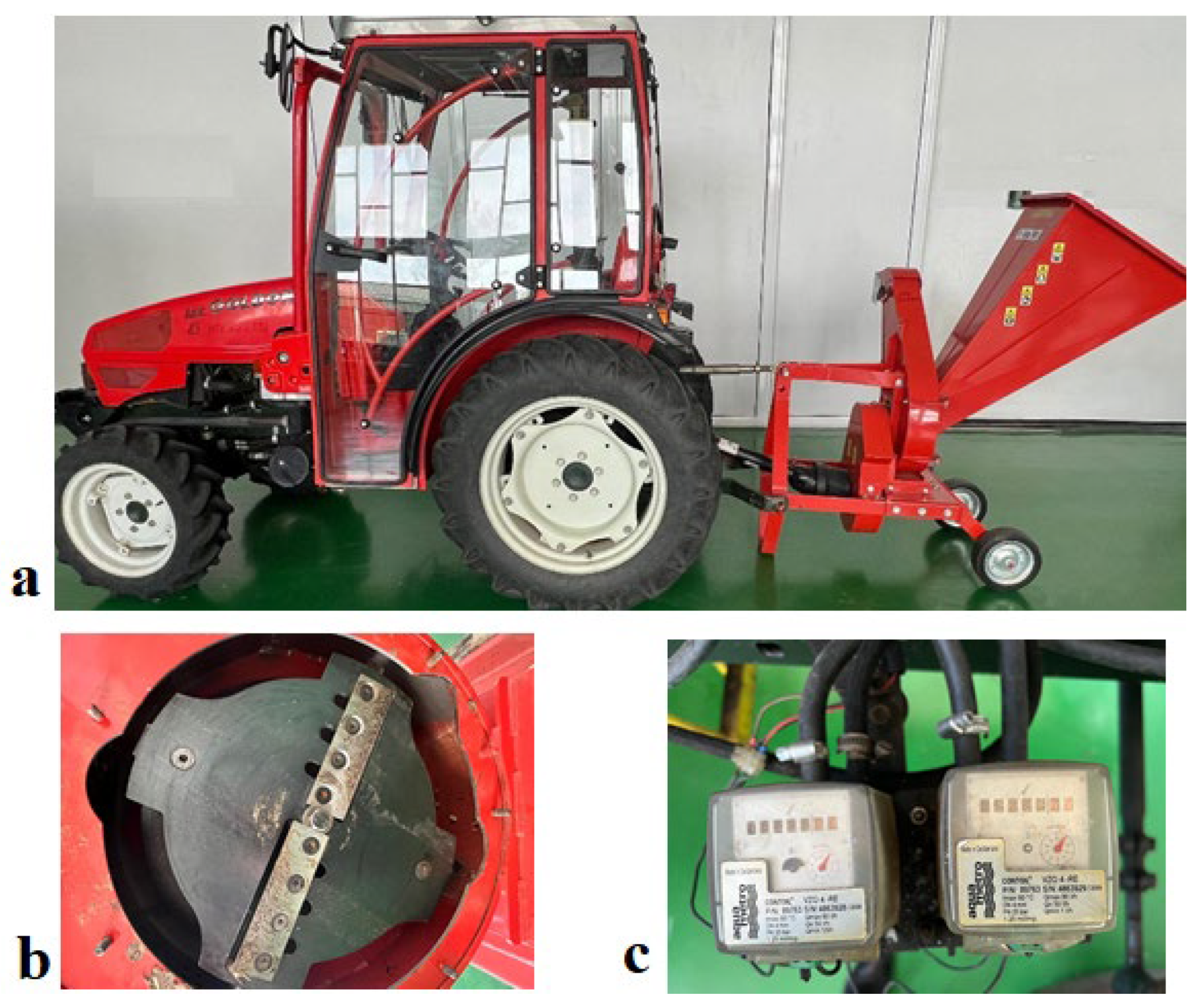

2.3. Tendrils Shredding-Grinding

The preparation of the biomass for briquetting required shredding-grinding technological operations, which were performed in two distinct stages: course shredding and fine shredding (grinding). A Caravaggi BIO 90 shredding machine, driven from a 45 HP tractor PTO (

Figure 4) was used for shredding the tendrils. The machine is equipped with two types of active parts: radial rotating knives and counter knife and articulated knives, mounted on the same rotor.

An universal hammer mill was used for the final grinding of the tendrils; the mill was equipped with a sieve with 8 mm diameter circular holes.

The naturally dried biomass was shredded after dehydration; the artificially dried biomass was shredded immediately after being collected.

The grinded biomass was sieved in order to eliminate the particles with a diameter over 8 mm; these particles were then grinded again. A mechanical sieving machine was used for this operation [

22].

Finally, the grinded biomass (I,

Figure 5) was collected in separated bags for each vine variety.

2.4. Densification of biomass

The shredded and grinded tendrils were densified in order to obtain briquettes (II,

Figure 5), using the GCBA-1 type briquetting machine (

Figure 6). This equipment produces Pini-kay type briquettes in a continuous operating process. The equipment has a truncated screw, with two operating areas: one for biomass feeding and pressing and a second one, with a smooth tip, generating a cylindrical orifice in the central part of the briquette. The screw is rotating with 373 rot·min

−1. The pressing chamber is shaped to generate briquettes in the shape of hexagonal prisms. The overall electric power of the equipment is 25 kW (18 kW the electric motor and 5 kW the heating resistance) [

22].

Before starting the densification process, the pressing device was heated to 170-180 °C, using the electric resistance placed on the outer surface of the pressing chamber. The briquetting temperature was monitored and adjusted by the means of an electronic thermostat.

The grinded biomass, with the dimension of the particles not exceeding 8 mm and a humidity ratio of 12.0 ± 0.5%, is taken over by the truncated screw and densified when passing through the inner bushes. The densified biomass is continuously discharged and is then spilt into briquettes with a length of 200 to 400 mm.

During the experiments at least 50 kg of briquettes were produced from each vineyard variety.

2.5. Evaluation of the Quality Indices of the Briquettes

The produced briquettes were evaluated for compliance with the requirements of the ISO 17225-3/2021 standard based on the following indices:

dimensions – the width and diameter were measured with a caliper for the smaller dimensions and with the measuring tape, for larger dimensions;

humidity ratio of the densified biomass – was evaluated using the thermal balance method;

ash content and chemical composition (N, S, Cl, As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Pb, Hg, Ni and Zn) for briquettes and pellets – according to the specifications of the ISO 16948/2015, ISO 16967/2015, ISO 16968/2015 and ISO 16994 standards (analysis performed at ICIA branch in Cluj-Napoca, Romania);

unit density – a graduated cylinder (62 mm diameter, 440 mm high) and an electronic scale (precision 0.01 g) were used; the cylinder, filled with 500 mL of water (m

a) was weighted and the briquette was then immersed into the cylinder, measuring the volume of dislocated water (V

a) and the overall mass of the cylinder (m

b). The unit density was calculated using the relation [

23]:

The mechanical durability was tested according to the method described in the SR EN ISO 17831-1/2016 standard, using the equipment presented in

Figure 7. The rotating drum of the equipment had an inner volume of 160 dm

3 (length: 598 ± 8 mm; diameter: 598 ± 8 mm) and an interior radial baffle (length: 598 ± 8 mm; height: 200 ± 2 mm; thickness: 2 mm).

The rotating speed of the drum was 21 ± 0.1 rev/min; the overall number of rotations and the rotating speed were measured using a tachometer.

For each test two briquettes with a mass lower than 0.5 kg were weighted (m

E) and then were introduced into the drum. A total number of 105 ±0.5 revolutions was performed; then, the material was sieved through a sieve with 45 mm diameter holes and the material that remained on the sieve was weighted (m

A). Mechanical durability was evaluated using the formula:

The durability tests were repeated three times for each vine variety.

2.6. Evaluation of the Overall Energy Consumption for Producing the Briquettes

In order to evaluate the overall energy consumption each technological phase from

Figure 1 (shredding, drying, sieving, grinding, briquetting) was assessed from the point of view of the energy input. The following equations were used:

where:

Eb1 is the energy consumption for briquetting the artificially dried biomass (MJ·kg−1);

Ebcg is the energy input for shredding the tendrils with a humidity ratio of 44-46% (MJ·kg−1);

Ebd is the energy consumption for the artificial drying of biomass to a humidity ratio of 10-12% (MJ·kg−1);

Ebm is the energy consumption for grinding the fractions bigger than 8 mm (MJ·kg−1);

Ebs is the energy input for sieving the shredded biomass (MJ·kg−1);

Eb is the energy consumption for briquetting the grinded biomass (MJ·kg−1);

Eb2 is the overall energy consumption for briquetting the naturally dried biomass (MJ·kg−1);

Ebcd is the energy consumption for grinding the naturally dried tendrils (MJ·kg−1);

kb1 și kb2 fractions referring to the biomass with particles bigger than 8 mm.

As mentioned before, the shredding of the biomass was performed using the Caravaggi BIO 90 shredding machine, which was driven from a 45 HP tractor PTO. The tractor was equipped with two Contoil VZO 4-RE fuel flowmeters, thus allowing the measurement of the fuel consumption during the shredding process. The energy consumption for shredding the biomass was calculated using the formula:

where ρ = 837 [kg·m

−3] is the density of Diesel fuel, Q

l is the fuel consumption for shredding the biomass [liters], P

i = 42.9 [MJ·kg

−1] is the calorific value of Diesel fuel and Q

m is the quantity of shredded biomass [kg].

Equipment powered with electricity was used for drying, sieving, grinding and briquetting. As a consequence, energy meters, type Voltcraft Energy Logger 4000, were used for measuring the energy consumption; one energy meter was used for each phase of the electric power grid. These energy meters stored data regarding the energy consumption on SDHC cards; the data was then downloaded to a computer for analysis and interpretation.

The energy efficiency for producing briquettes from vine tendrils was calculated using overall energy consumption data, using the following relations:

for the naturally dried biomass:

where Q is the calorific value of the briquettes and E

b1 and E

b2 is the overall energy consumption (as mentioned above).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results Regarding the Quantity of Biomass Collected from the Winter Pruning

In order to emphasize the energy potential of the tendrils resulting from the winter pruning of vine, the following indices were evaluated: average quantity of biomass per stump; average quantity of tendrils per hectare (at the initial humidity ratio and after drying the tendrils to 12% humidity ratio), taking into account the density of 4347 plants/ha. From the results shown in

Table 1 it was concluded that the Muscat Ottonel variety has produced the highest quantity of tendrils, in terms of average mass/stump and overall mass (0.433 kg/stump and 1882.2 kg, respectively), while the smallest amount of tendrils resulted from the Cabernet Sauvignon variety (0.327 kg/stump and 1421.4 kg, respectively). The same variety (Muscat Ottonel) has producved the maximum amount of biomass with 12% humidity ratio (1250.8 kg).

3.2. Results Regarding the Preparation of Biomass for Briquetting

The tests performed in this stage were aiming to the preparation of the tendrils according to the technological requirements of the densification process: humidity ratio lower than 12% and dimensions of the particles smaller than 8 mm in order to allow briquetting. As mentioned above, two technologies were considered: natural drying and artificial drying of biomass.

The shredded biomass was sieved in order to separate the particles of different sizes;

three size fractions were considered, according to

ISO 17827-1 and

ISO 17827-2 standards: particles which are bigger than 8 mm (which are then grinded), particles with dimensions between 8 and 3.15 mm and particles smaller than 3.15 mm (Table 2).

The experimental data has shown that the percentage of particles bigger than 8 mm has increased when high humidity ratio tendrils were shredded, while shredding of dry biomass resulted in a higher percentage of particles smaller than 3.15 mm. The separation of shredded biomass into fractions has provided the coefficients kb1 (equation 4) and kb2 (equation 5) for particles bigger than 8 mm (which must further be grinded), thus allowing the evaluation of the hammer mill operating capacity and energy consumption.

When the shredded biomass containing particles bigger than 8 mm was grinded, over 96% of the resulting particles had dimensions between 3.15 mm and 8 mm, no matter of the drying technology used (natural or artificial).

3.3. Results Regarding the Characteristics of the Briquettes Produced from Vine Tendrils

In order to evaluate the sustainability of the briquettes production using vine tendrils as raw material, the requirements of the ISO 17225-3/2021 standard were considered with respect to the characteristics of the briquettes (

Table 3).

The measured dimensions (diameter and length) correspond to the Pini-kay type briquettes, with D representing the diameter of the hexagon inscribed circle and L being the length of the briquette. The briquetting machine used in these experiments operates continuously and allows the adjustment of the briquette length.

The humidity ratio of the briquettes has recorded values well under the requirements of the standard, comprised between 7.78% and 8.20% for the Busuioacă de Bohotin variety. This is due to the fact that during densification the biomass is quickly heated to 180-220 °C, thus leading to significant water evaporation in a short period of time.

The density of the briquettes was evaluated according to the specifications of the ISO 18847 standard, using equation (1), and it resulted to be above the one prescribed by the ISO 17225-3 standard, due to the higher densification pressures (over 20 MPa) and temperatures achieved by the equipment in use. For all the vine varieties taken into account for the production of briquettes, the unit density was higher than 1389 kg/m3, which is a proof that this type of biomass is very suited for densification.

Ash is a combustion product, being composed of incombustible materials, such as mineral salts. These remain as dust residues into the combustion place. Consequently, the ash content is an important quality index, leading to problems during the processing and combustion of biomass [

38,

39,

40]. In solid biofuels, ash diminishes the calorific value and impedes the diffusion of air into the hotbed, forming plastic conglomerates that include large quantities of fuel, which thus becomes unavailable for combustion.

The ash content of the tested briquettes has recorded values comprised between 2.09%, for the Muscat Ottonel variety, and 3.27%, for the Fetească neagră variety.

The calorific value of the briquettes is an important characteristic, related to the energy content of biomass; this feature was approached in a previous paper [

23]; the results show that the higher calorific value is approximately 19 MJ·kg

−1, while the lower calorific value is 17 MJ·kg

−1.

The importance of the chemical composition of the briquettes has been largely analyzed in another paper [

38]. The chemical composition of the briquettes was analyzed according to the requirements of the respective standards (ISO 16948 for nitrogen; ISO 16994 for Sulphur and chlorine; ISO 16968 for arsenic, cadmium, chrome, copper, mercury, nickel and zinc). The results presented in

Table 3 show that the majority of the parameters were within the limits imposed by the ISO 17225-3/2021 standard for the class A1, A2 and B1 briquettes; the values for chrome, copper and cadmium have exceeded the maximum limits imposed by the standard.

Nevertheless, the biomass produced from vine tendrils, densified as briquettes, is a valuable, worth using solid fuel. Moreover, densification of the biomass in the form of briquettes leads to high energy products with high added value and eliminates the burning of the agricultural waste in open field, with negative impacts over the environment.

3.4. Results Regarding the Energy Consumption and Energy Efficiency for Producing Briquettes from Vine Tendrils

Table 4 presents the experimental results regarding the energy consumption for the shredding, drying, sieving, grinding and densification of biomass.

The energy used for shredding the tendrils with a humidity ratio of 44-46% (E

bcg) and of those which were naturally dried to a humidity ratio of 10-12% (E

bcd) is mainly affected by the state of biomass. Thus, for the tendrils with a high humidity ratio the energy consumption increased with 10-15% in comparison with the dried tendrils. In the meantime, there was no significant effect of the vine variety over the energy consumption. These findings are in accordance with the results presented by other authors [

41].

The energy required for drying the biomass down to 10-12% humidity ratio (E

bd) represents the sum of the energies involved in the heat and mass transfer between the drying agent and the biomass, divided by the quantity of dehydrated tendrils. According to the experimental results, the specific energy consumption for drying was comprised between 2.421 MJ kg

−1, the Fetească albă variety and 2.731 MJ kg

−1 for the Muscat Otonel variety. These results are consistent with the ones reported by other authors [

42,

43].

In order to separate the fractions with particles bigger than 8 mm the shredded biomass was sieved; the energy consumption for this operation was comprised between 7.2 kJ·kg−1 for the Pinot noir, variety and 8.1 kJ·kg−1 for the Fetească neagră variety.

The values of the coefficients k

b1 and k

b2 (referring to particles bigger than 8 mm), shown in

Table 4, are in accordance with the results shown in

Table 2

The energy required for grinding the fractions containing particles bigger than 8 mm (Ebm) recorded values between 0.0976 MJ·kg−1 for the Cabernet Sauvignon variety and 0.1032 MJ·kg−1 for the Muscat Ottonel variety.

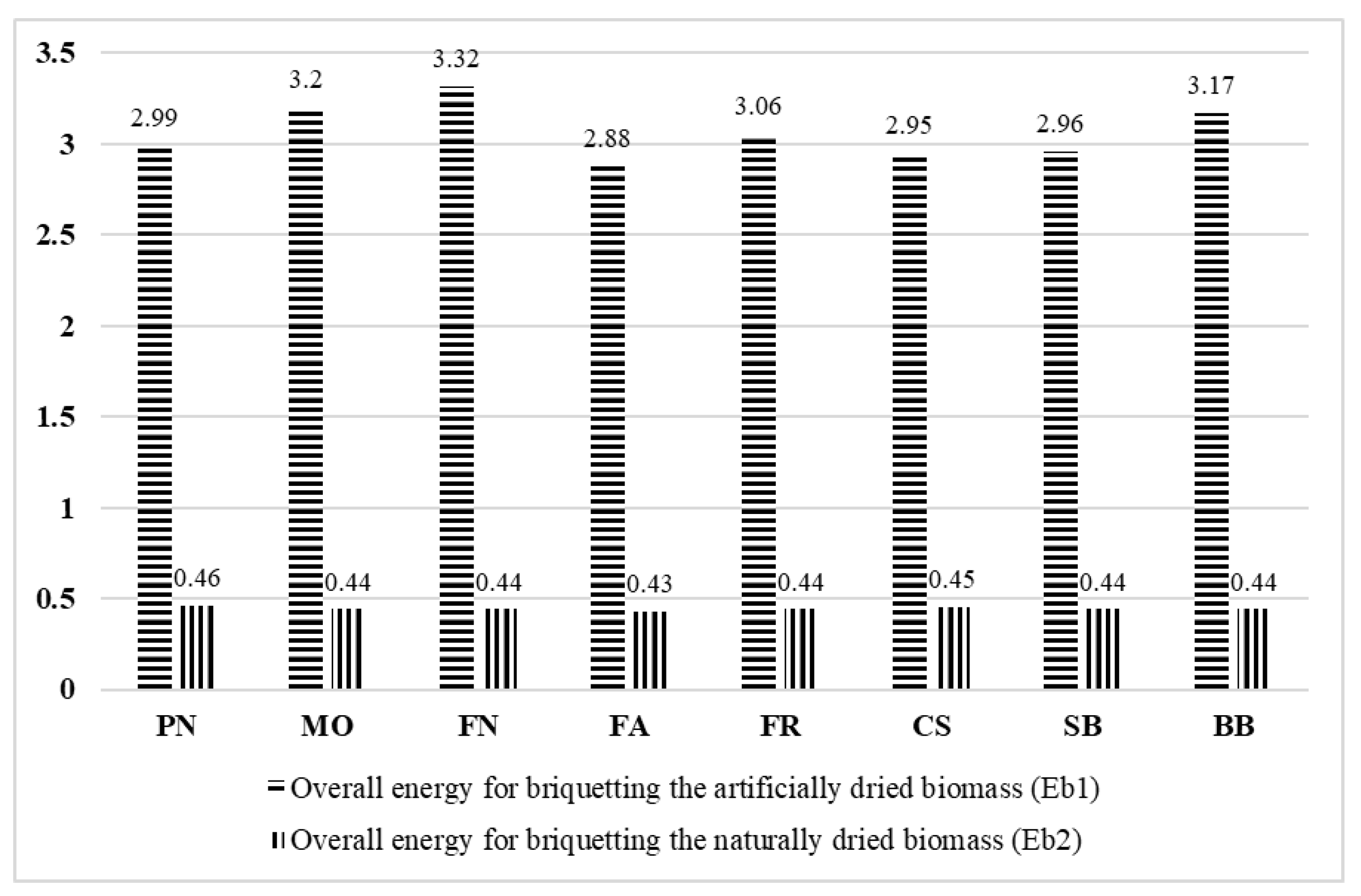

Based on the data presented in

Table 4 and using equations (3) and (4), the overall energy consumption was calculated for the two technologies taken into account: artificial drying (E

b1) and natural drying of the raw material (E

b2). The results are summarized in

Figure 8 and they clearly show that artificial drying significantly increases the energy input for lowering the humidity content from 44% to 12%.

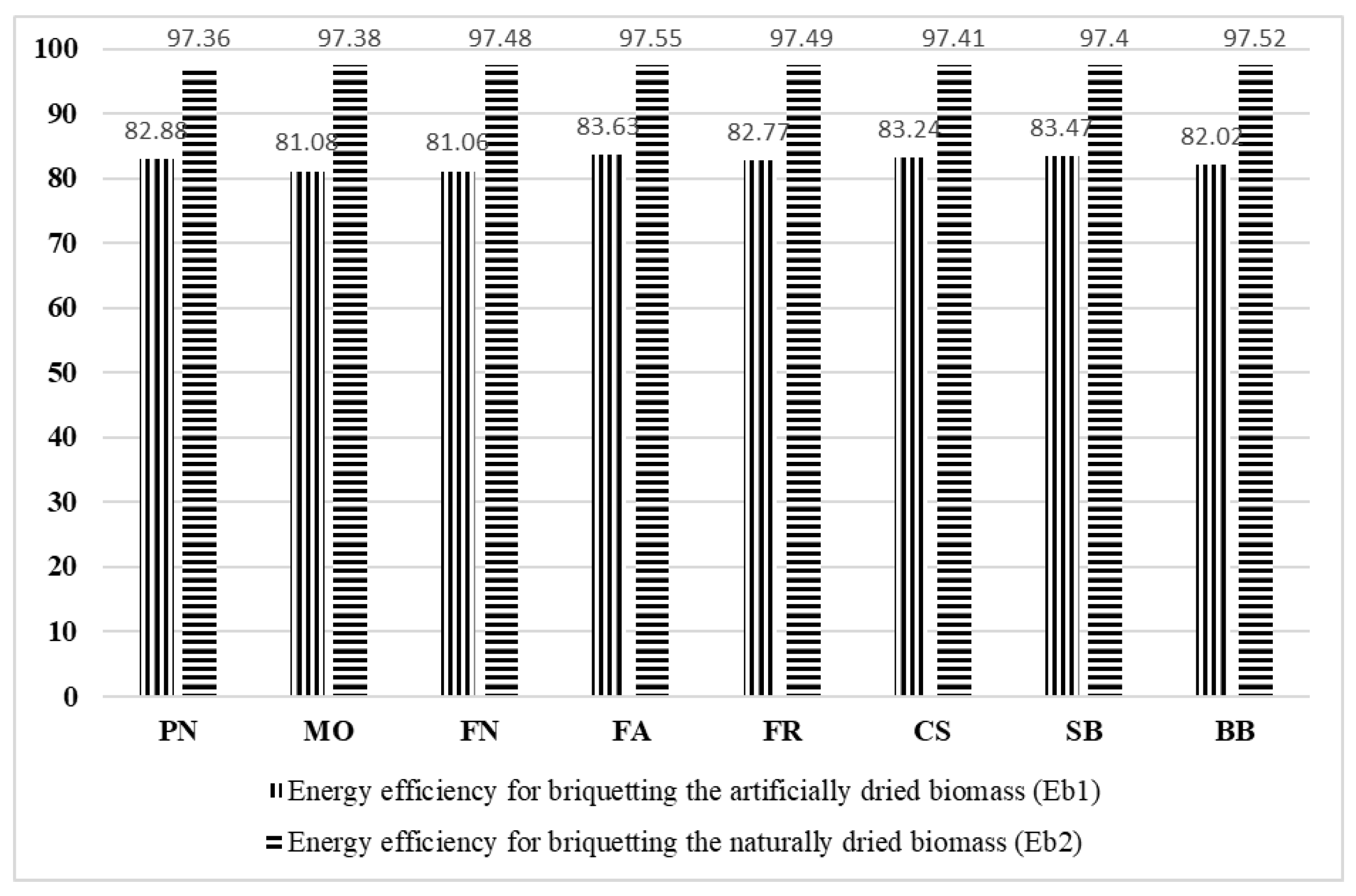

The energy efficiency for briquetting the agricultural waste from vine winter pruning was calculated using the data in

Figure 8 (referring to the overall energy consumption), considering the lower calorific value of the briquettes (

Table 3) and using equations (6) and (7). The results are depicted in

Figure 9 and they clearly show that artificial drying leads to an average efficiency of 82.52%, while natural drying has recorded a higher average efficiency (97.45%). These values are a solid proof that using the vine tendrils as raw material for producing briquettes is a sustainable method and this agricultural waste may be taken into account as an important and reliable source of renewable energy. Moreover, this study emphasizes the idea of using agricultural waste in order to obtain energy carrier products, with high added value, thus avoiding burning them in open field, with major negative impacts over the environment.

The briquettes that were produced have high mechanical properties, due to the fact that biomass has 22.4-35.5% lignin, 30.2-36.2% cellulose and 16.5-24.4% hemicellulose, depending upon the vine variety [

37]. Due to the high lignin content briquetting may be performed without the use of binding substances, and the mechanical durability of the briquettes is higher than 97.0% [

22]; thus, the mechanical integrity of the briquettes is preserved during maneuvering, transport and storage.

This study provides a model for the practical application of the circular economy concept, which is an economic model aiming to minimize the wastes and maximize the use of resources by promoting recycling, reusing and regeneration [

44]. This system, based on the valorization of the wastes from different agricultural and food industry technological processes, provides energy resources for other branches of the economy, thus eliminating the concept of waste.

4. Conclusions

The biomass resulted from the agricultural technological processes is a primary source of carbon, which may be used as raw material for producing solid biofuels with high energy value for different economic activities. Biomass is the only renewable resource that may be directly used for combustion. The combustion of biofuels releases CO2 into the atmosphere, which is then utilized by plants to produce new quantities of biomass.

The aim of the paper was to assess the sustainability of briquettes production using vine tendrils resulted from vine pruning as raw material.

When designing the scientific endeavor, the following aspects were considered: defining the aim and objectives of the research; design of the research algorithm; collection, preparation and conditioning of the biomass; chemical analysis of the briquettes; evaluation of the technological characteristics of the briquettes; evaluation of the energy consumption and energy efficiency for producing the briquettes, taking into account two drying methods (natural and artificial drying).

The analysis of the experimental data led to the following conclusions:

the average quantity of dried biomass (12% humidity ratio) exceeded 1000 kg·ha−1;

the lower calorific value of the briquettes from vine tendrils is over 17 MJ·kg−1;

the unit density of the produced Pini-kay type briquettes is over 1330 kg·m−3;

the dimensions of the briquettes are within the limits imposed by the international standards;

the chemical composition of the briquettes is within the limits imposed by the ISO 17225-3/2021 standard for the class A1, A2 and B1 briquettes for most of the parameters; the values for chrome, copper and cadmium exceed the maximum limits imposed by the standard.

the overall energy consumption for producing the briquettes is mainly affected by the drying method: forced convection requires a significant higher energy consumption for reducing the humidity ratio from 44% to 12% in comparison with natural convection;

artificial drying leads to an average energy efficiency of 82.52%, while a higher average efficiency (97.45%) was obtained for the natural drying of biomass.

Although some of the chemical elements in briquettes exceed the limits imposed by the ISO 17225-3/2021 standard, the biomass produced from vine tendrils may be regarded as a valuable solid biofuel, with high added energy value. In the meantime, the valorization of biomass in the form of briquettes eliminates the need for their disposal through burning in open field, thus eliminating the negative impact over the environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.Ț.; methodology, I.Ț. and P.C.; validation, R.R., P.C. and V.A.; formal analysis, C.R., L.S. and O.R.C.; investigation, I.Ț. and O.R.C.; resources, M.B. and L.B..; data curation, R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C. C.R. and L.S.; writing—review and editing, R.R., P.C. and O.R.C.; project administration, I.Ț. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UEFISCDI Bucuresti, grant number 4PCCDI/2018” and the publication fees were paid by “Ion Ionescu de la Brad” Iași University of Life Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sarker T. R., Nanda S., Meda V., Dalai A. K. Densification of waste biomass for manufacturing solid biofuel pellets: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2023, 21:231–264. [CrossRef]

- Kpalo, S.Y.; Zainuddin, M. F.; Manaf, L.A.; Roslan, A. M. A Review of Technical and Economic Aspects of Biomass Briquetting, Sustainability 2020, 12(11), 4609. [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, G.S.; Makhashvili, K.A. Climate changes and photosynthesis. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2016, 14, 119–126. [CrossRef]

- Kaltschmitt, M. Renewable energy from biomass, Introduction. In Renewable Energy Systems; Kaltschmitt, M., Themelis, N.J., Bronicki, L.Y., Söder, L., Vega, L.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 45–71.

- Tursi, A. A review on biomass: Importance, chemistry, classification, and conversion. Biofuel Res. J. 2019, 6, 962–979. [CrossRef]

- Parmar, K. Biomass. An overview on composition characteristics and properties. IRA-Int. J. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 42–51; [CrossRef]

- Kalak T. Potential Use of Industrial Biomass Waste as a Sustainable Energy Source in the Future. Energies 2023, 16(4), 1783. [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Berry, H.; Boykoff, M.; Montgomery, H.; Costello, A. The 2018 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Shaping the health of nations for centuries to come. Lancet 2018, 392, 2479–2514. [CrossRef]

- Dilpreet, S. B.; Tyler, P.; Neeta, S.; Jamileh, S.; Sreekala, G. B. A review of densified solid biomass for energy production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 96, 296-305. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; McConkey, V.; Huffman, V.; Smith, S.; MacGregor, B.; Yemshanov, D.; Kulshreshtha, S. Potential and impacts of renewable energy production from agricultural biomass in Canada. Appl. Energy, 2014, 130, 222-229. [CrossRef]

- Anenberg, S.C.; Balakrishnan, K.; Jetter, J.; Masera, O.; Mehta, S.; Moss, J.; Ramanathan, V. Cleaner Cooking Solutions to Achieve Health, Climate, and Economic Cobenefits. Env. Sci Technol. 2013, 47, 3944–3952. [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, S.E.; Jen, T.C.; Mahamood, R.M.; Akinlabi, E.T. Densification of agro-residues for sustainable energy generation: an overview. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 75. [CrossRef]

- Maj, G.; Klimek, K.; Kapłan, M.; Wrzesińska-Jędrusiak, E. Using Wood-Based Waste from Grapevine Cultivation for Energy Purposes. Energies 2022, 15, 890. [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, N.; Blujdea, V.; Dallemand, J. Assessment of the availability of agricultural and forest residues for bioenergy production in Romania. Biomass and Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1995-2005. [CrossRef]

- Senila, L.; Ţenu, I.; Carlescu, P.; Corduneanu, O.R.; Dumitrachi, E.P.; Kovacs, E.; Scurtu, D.A.; Cadar, O.; Becze, A.; Senila M.; Roman, M.; Dumitraş D.E.; Roman, C. Sustainable Biomass Pellets Production Using Vineyard Wastes. Agriculture 2020, 10(11), 501. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, H.; Yazdanpanah, F.; Lim, C.J.; Sokhansanj, S. Pelletization properties of refuse-derived fuel—effects of particle size and moisture content. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 205, 106437. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, A.; Rodrigues, M.; Montañés, C.; Dopazo, C.; Fueyo, N. The potential for electricity generation from crop and forestry residues in Spain. Biomass Bioenergy 2010, 34, 703-719. [CrossRef]

- Gong, C; Meng, X.; Thygesen, L.G.; Sheng, K.; Pu, Y.; Wang, L.; Ragauskas, A.; Zhang, X.; Thomsen, S.T. The significance of biomass densification in biological-based biorefineries: A critical review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 183, 113520. [CrossRef]

- Stelte, W.; Sanadi, A.R.; Shang, L.; Holm, J.K.; Ahrenfeldt, J.; Henriksen, U.B. Recent developments in biomass pelletization–A review. Bioresources 2012, 7 (3), 4451–4490; 10.15376/biores.7.3.4451-4490.

- Priyabrata, P.; Amit A.; Sanjay, M.M. Pilot scale evaluation of fuel pellets production from garden waste biomass. Energy for Sustainable Development 2018, 43, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Dragusanu, V.; Lunguleasa, A.; Spirchez, C.; Scriba, C. Some Properties of Briquettes and Pellets Obtained from the Biomass of Energetic Willow (Salix viminalis L.) in Comparison with Those from Oak (Quercus robur). Forests 2023, 14, 1134. [CrossRef]

- Ţenu, I.; Roman, C.; Senila, L.; Roşca, R.; Cârlescu, P.; Băetu, M.; Arsenoaia, V.; Dumitrachi, E.P.; Corduneanu, O.-R. Valorization of Vine Tendrils Resulted from Pruning as Densified Solid Biomass Fuel (Briquettes). Processes 2021, 9, 1409. [CrossRef]

- Zardzewiały, M.; Bajcar, M.; Saletnik, B.; Puchalski, C.; Gorzelany, J. Biomass from Green Areas and Its Use for Energy Purposes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6517. [CrossRef]

- Polonini, L.F.; Petrocelli, D.; Lezzi, A.M. The Effect of Flue Gas Recirculation on CO, PM and NOx Emissions in Pellet Stove Combustion. Energies 2023, 16, 954. [CrossRef]

- Giorio, C.; Pizzini, S.; Marchiori, E.; Piazza, R.; Grigolato, S.; Zanetti, M.; Cavalli, R.; Simoncin, M.; Soldà, L.; Badocco, D.; et al. Sustainability of using vineyard pruning residues as an energy source: Combustion performances and environmental impact. Fuel 2019, 243, 371–380. [CrossRef]

- Waheed, M.A.; Akogun, O.A.; Enweremadu, C.C. An overview of torrefied bioresource briquettes: quality-influencing parameters, enhancement through torrefaction and applications. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2022, 9, 122. [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Liu, Y.; Guan, F.; Wang, N. How to coordinate the relationship between renewable energy consumption and green economic development: from the perspective of technological advancement. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 71. [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, R.; Lombardini, C.; Pari, L.; Sadauskiene, L. An lternative to fieldburning of pruning residues in mountainvineyards. Ecological Engineering 2014, 40. [CrossRef]

- Thornley, P.; Rogers, J.; Huang, Y. Quantification of employment from biomass power plants. Renewable energy, 2008, 33, 1922-1927. [CrossRef]

- Saidur, R.; Abdelaziz, E.A.; Demirbas, A.; Hossain, M. S.; Mekhilef, S. A review on biomass as a fuel for boilers. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011, 15 (5), 2262-2289. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. Possibility of utilizing agriculture biomass as a renewable and sustainable future energy source. Heliyon 2022, 8 (2), e08905. [CrossRef]

- Bechis, S. Possible impact of pelletised crop residues use as a fuel for cooking in Niger. In Renewing Local Planning to Face Climate Change in the Tropics, Springer, Cham, 2017, 311-322. [CrossRef]

- Baum, R.; Wajszczuk, K.; Peplinski, B.; Wawrzynowicz, J. Potential for agricultural biomass production for Energy purposes in Poland: a review. Contemp. Econ. 2013, 7 (1), 63–74. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Ahmad, B. Burning of crop residue and its potential for electricity generation. The Pakistan Dev. Rev. 2014, 53 (3), 275–293. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24398410. Accessed 17 December 2023.

- Swanston, J.S.; Newton, A.C. Mixtures of UK wheat as an efficient andenvironmentally friendly source for bioethanol. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9 (3), 109–126; [CrossRef]

- Nichols, N.N.; Bothast, R.J. Production of Ethanol from Grain. In Genetic Improvement of Bioenergy Crops; Editor: Vermerris, W. Springer, New York, NY, 2008; pp. 75-88. [CrossRef]

- Senila, L.; Ţenu, I.; Cârlescu, P.; Scurtu, D.A.; Kovacs, E.; Senila, M.; Cadar, O.; Roman, M.; Dumitras, D.E.; Roman, C. Characterization of biobriquettes produced from vineyard wastes as a solid biofuel resource. Agriculture 2022, 12(3), 341. https://doi:10.3390/ agriculture12030341.

- Țenu, I.; Roșca, R.; Cârlescu, P.; Cecilia, R.; Senila, L.; Arsenoaia, V.; Corduneanu, O. Researches regarding the evaluation of energy consumption for the manufacturing of pellets from vine pruning residues. In Proceedings of Engineering for Rural Development Conference, Jelgava, Latvia, 20-22.05.2020, pp. 54-62. [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, R.; Magagnotti, N.; Nati, C. Harvesting vineyard pruning residues for energy use. Biosystems Engineering 2010, 105 (3), 16-322. [CrossRef]

- Marian, G.; Ianus, G.; Istrate, B.; Banari, A.; Nazar, B.; Munteanu, C.; Malutan, T.; Daraduda, N.; Paleu, V. Evaluation of Agricultural Residues as Organic Green Energy Source Based on Seabuckthorn, Blackberry, and Straw Blends. Agronomy 2022, 12 (9). [CrossRef]

- Murugan, P.; Dhanushkodi, S.; Sudhakar, K.; Wilson, V.H. Industrial and Small-Scale Biomass Dryers: An Overview. Energy Engineering 2021, 118 (3), 435-446. [CrossRef]

- Lisowski, A.; Klonowski, J.; Sypuła, M.; Chlebowski, J.; Kostyra, K.; Nowakowski, T.; Strużyk, A.; Świętochowski, A.; Dąbrowska, M.; Mieszkalski, L.; Piątek, M. Energy of feeding and chopping of biomass processing in the working units of forage harvester and energy balance of methane production from selected energy plants species. Biomass and Bioenergy 2019, 128, 105301. [CrossRef]

- Dhanushkodi, V.; Wilson, H.; Sudhakar, K. Energy analysis of cashew nut processing agro industries: A case study. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science 2016, 22 (4), 635–642.

- Nattassha, R.; Handayati, Y.; Simatupang, T.M.; Siallagan, M. Understanding Circular Economy Implementation in the Agri-Food Supply Chain: The Case of an Indonesian Organic Fertiliser Producer. Agric. Food Secur. 2020, 9, 10. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).