Appendix A. Mathematical Constraints of the Dual Ontology Model

Introduction

Appendix A presents mathematics constrained by the Dual Ontology (DO). The ontology determines which entities are admissible and how they behave; the mathematics implements those specifications without altering them. Within these bounds, this appendix defines the admissible objects, the single energy-based operator that governs both motion and gravitational response, and the collapse rule that acts in the Planck Domain and is mirrored into discrete 4D spacetime. Methods, solvers, and calibrations are outside this appendix; Appendix B provides five independent mathematical validations using only the Appendix A objects and rules.

For orientation, terminology follows the main text. A Discrete Sphere (DS) is an indivisible spatial unit with fixed volume. A Bell Field is the set of DS currently occupied by a quantum state in 4D spacetime. The Bell Energy Field assigns local energy on those DS. The Planck Domain is a real, independent, timeless domain comprising all DS, with formal dimension and no internal metric or internal spatial separation. A Bell Energy Point is the quantum state’s timeless representation in the Planck Domain. The Bell Identity g mirrors, sphere by sphere and energy total for energy total, between a quantum state in 4D spacetime and the Planck Domain.

Single operator. One operator with a single link kernel drives both kinetic motion and relational gravitational response. The kinetic part updates by energy-weighted exchange across links. The gravitational part couples to a scalar influence generated from the same energy sources through the same kernel. The uniform mode is neutral.

Evolution and collapse. Between collapses, the Unified Evolution Equation deterministically updates the Bell Energy Field on the discrete 4D graph. Collapse is instantaneous in the Planck Domain and mirrored to 4D spacetime on the same tick. An admissible outcome is any connected subset of the pre-collapse Bell Sphere support. The probability of an outcome equals the fraction of the quantum state’s total energy that was in that subset just before collapse. Over any set of mutually exclusive outcomes that together cover the pre-collapse support, the probabilities add to one.

Equivalence consequence. For any body, quantum or classical, the inertial parameter equals the gravitational source, . Free-fall acceleration is independent of composition and depends only on the sources’ energies through the kernel.

Guardrails. Rotation and permutation invariance on the lattice; exact conservation of total intrinsic energy between collapses; neutrality of the uniform mode; no background metric and no independent gravitational field to quantize.

Scope and Linkage

This appendix records the mathematical objects and constraints of the DO model. It is physics- neutral: no observational calibrations, data choices, or run-specific numerical settings are assumed here. Those choices and their statistical vetting are provided in Appendix B.

Conventions used in this appendix.

Graph distance and neighborhood. Unless noted, the graph distance denotes the Chebyshev hop-distance on a 3D cubic network; “” refers to the full nearest-neighbor set. Results rely only on shell isotropy and therefore extend to any graph family whose shell structure admits the arguments of Section 2.10.

Kernel class. Link weights are members of the uniqueness class defined in Section 1.1.9. The concrete kernels used in simulations (Appendix B) are representatives of ; no derivation here depends on a particular representative.

Units and unit mapping. Energy-like quantities are expressed in internal units with unless explicitly restored. The invariant speed c is one hop per time tick by definition.

Observational calibration. The global amplitude mapping used for data comparison is an operational calibration introduced only in Appendix B; it is not a parameter of the theory and does not enter the equations here.

Validation probes. Rotation gates (axis permutations) and -scaling checks are estimator validation tests reported in Appendix B. They are not additional axioms of Appendix A.

Tick labels (metadata only). We reserve for the discrete tick index. When cosmology labels are attached to a run, they are a fixed, monotone metadata map with chosen to denote the CMB epoch; these labels never enter any equations in Appendix A.

This preface makes Appendix A self-contained while remaining compatible with the discrete- relational demonstrations summarized in Appendix B.

1. Formal Structure of the Dual Ontology Model

Appendix A records architecture-level definitions and constraints for the DO. It is method-agnostic: concrete numerical realizations (kernels, stencils, time-steppers, solver tolerances) are outside its remit and may vary provided they respect the axioms and conservation statements given here. Appendix B provides one admissible realization; others are admissible if they obey the same axioms.

The DO framework is constructed entirely from discrete, physically real structures and is structurally incompatible with Hilbert space, Fock space, configuration space, matrix mechanics, and the Schrödinger equation. These constructs do not appear in Appendix A.

The DO model strives for a unified ontological and dynamical framework built without ad hoc assumptions, fine-tuning, or perturbative methods.

The model defines quantum evolution and collapse over a discrete, background-independent 4D spacetime and a -dimensional Planck Domain , where N is the total number of Discrete Spheres. consists of a subset of this fixed set. These two domains are tightly integrated and constrained, with their dynamics and interactions governed by principles detailed below:

Quantum Evolution in 4D Spacetime

Quantum states evolve deterministically in discrete 4D spacetime via the Unified Evolution Equation (UEE), as detailed in

Section 2.3. Lorentz invariance, if it emerges, would appear only in an appropriate continuum limit; the fundamental dynamics of the DO model are discrete.

Quantum Collapse in the Planck Domain

Collapse is a probabilistic, instantaneous, and non-reversible event in the Planck Domain.

Relational Gravity

Gravity emerges from discrete quantum interactions in 4D spacetime. No continuous field or quantization is included in the DO model.

Discrete Cosmological Evolution

The DO model defines cosmological evolution as an instantaneous collapse from a dispersed 4D spacetime at Heat Death to a localized discrete structure at .

1.1 Mathematical Definition of Terms and Structures

1.1.1 DO Sub-Structure

Discrete Spheres (Ontological Definition): Fundamental ontological constituents include set

containing all

N Discrete Spheres (DS) in the ontology (

N = total number, unknown, possibly infinite):

Each element is an irreducible unit of spatial ontology.

State of Absolute Nothingness (SOAN): An explicitly passive, dimensionless ontological entity () without physical properties (space, volume, time). It is the invariant ontological condition enabling mirroring between and but does not interact with DS.

Invariant Speed of Light (c):

In the discrete DO framework,

c is defined as one adjacent-sphere hop per discrete time tick, making

c a dimensionless hop-rate. When mapping to physical units, assign a hop-length

(e.g., the Planck length) and a time tick

such that

This is a choice of units used in simulations; it does not alter dynamical content.

Constants and unit mapping.

|

internal energy per sphere; physical energy

|

| c |

hop/tick internally; map by for physical units |

|

appear only as operator prefactors; symbolic until unit mapping is chosen |

|

global amplitude bridge for spectra (reported in Appendix B); not part of dynamics |

Default simulations take ; physical reporting applies the above maps.

1.1.2. The State Descriptor () and Energy Relational Connectivity in

To describe the state of a quantum system, the DO model introduces a fundamental state descriptor, denoted by the symbol (Phi). The traditional quantum mechanical symbol for the wavefunction, (Psi), is deliberately avoided. This is a critical conceptual distinction. In standard quantum mechanics, represents a complex probability amplitude in an abstract Hilbert space, where defines a probability density. The DO model is ontologically incompatible with this formalism. In the DO model, represents a physically real scalar state corresponding to the distribution of energy across a set of occupied Bell Spheres. Consequently, is not a probability density but a direct measure of physical energy density.

Discrete Spheres in

form a dynamic relational graph. Connectivity between any two spheres

at time

t is determined by the system’s total energy distribution,

Let

where

is the state-dependent link weight (Section 1.1.7.1). One representative

combining exponential decay with a discrete radial Poisson component is detailed in Appendix B; any

is admissible in Appendix A.

1.1.3 Planck Domain ()

The Planck Domain is an ontologically real domain comprising all N Discrete Spheres (individually denoted ). Each is intrinsically 3-dimensional. These N DS integrate within , forming a single, unified structure: the Universal Planck Point. itself represents the maximal Universal Planck Point, encompassing all N DS.

A defining characteristic of any Planck Point (including ) is that, although composed of intrinsically 3D entities (), it lacks internal spatial separation between constituents and has no overall conventional spatial volume. The formal dimensionality of is , arising from its N intrinsically 3D DS.

Its mathematical representation is an explicitly ordered collection of coordinate identifiers assigned purely for indexing and identification, not as physical spatial coordinates:

Each triple

identifies the

i-th DS

within

’s Universal Planck Point structure. Ontologically:

Interpretation: no coordinate embedding or spatial separation is implied between and any other within ; the triples are identifiers only.

The integrated Dual Ontology structure

combines

and

:

Fundamental constraints for

include timelessness and explicit absence of internal metric structure:

Additional constraints and (stress-energy and Einstein tensors, respectively) reflect the absence of standard spacetime dynamics within . Thus, serves strictly as the timeless, metric-free locus for quantum state representations (Bell Energy Points, Section 1.1.5). SOAN (Section A) provides the invariant, property-free reference by which is defined as timeless and metric-free; all PD representations are taken relative to this neutral condition.

1.1.4 Planck Identity and Structural Distinction

The Planck Identity establishes fundamental ontological identity for each Discrete Sphere as represented in

(by

) and

(by

):

where ≡ denotes ontological identity. This ensures a DS maintains consistent unique identifiers (e.g., intrinsic coordinate labels, if assigned) across its manifestation as

(potentially in

) and its corresponding constituent

within

’s Universal Planck Point structure (Section 1.1.3, identified by tuple in Equation (2).

Let

be the set of effective relational connections defining

dynamic topological structure at time

t, determined by Energy Relational Connectivity (Section 1.1.2). Such a relational topological structure is not defined for

(Section 1.1.3), reflecting its Universal Planck Point nature where constituent

lack defined mutual spatial separation. Thus, their topological structures are fundamentally distinct:

This reflects the distinct domain natures despite shared ontological constituents (Discrete Spheres), identified via Equation (6).

1.1.5 Bell Identity

The Bell Identity

g mirrors quantum state properties between domains

and

. For a single-state representation at discrete time

t:

and for general

N-body representations (

):

A quantum state’s representation within the Planck Domain is explicitly defined as a Bell Energy Point (BEP) ( for single-state, for N-body), timelessly encapsulating the state’s total energy and all other fundamental invariant properties (e.g., spin, charge).

Energy Conservation (DO Ontological Postulate): The total intrinsic energy

of any isolated system in

remains constant over discrete time

t. For a hybrid system containing both quantum states (described by

) and classical "hard masses" (described by a real-valued energy field

), this energy is the sum over all sources:

Here, energy may come from the dimensionless magnitude squared of a quantum field, , converted to physical units by the fundamental unit constant , or from the axiomatically defined energy of a classical mass, . Unless explicitly noted otherwise, is assumed for simplicity. This total intrinsic energy equivalently characterizes the system’s Bell Energy Point ( or ) through the Bell Identity g. Consequently, total energy and all associated conserved state properties of the complete system remain persistently encoded in the timeless BEP within .

Binding–Energy Convention. For any composite, the total intrinsic energy is . The inertial parameter equals the gravitational parameter, . Formation of a bound state reduces both inertial response and gravitational sourcing by .

Inertial–Gravitational Energy Identity (DO). For any body

n (quantum or classical) with total intrinsic energy

as mirrored by its BEP via

g, define its inertial parameter by

The Relational gravitational operator

couples only to source energies

(or their classical counterparts), so the net gravitational sourcing strength of a localized body also equals

. Therefore, within the DO ontology,

Accordingly, “mass” in Appendix A is a units label for energy; both inertial response and gravitational sourcing track the same scalar . See also Section A (Equivalence Consequence) for the N-body classical limit using this identity.

1.1.5.1 Formalism for Intrinsic Spin

Postulate I (The Spin Vector). Each Bell Sphere a constituting a quantum state’s Bell Field possesses an intrinsic spin vector .

For a spin-½ entity, the magnitude is invariant:

Postulate II (State Encoding). The complete spin character of a quantum state is defined by the collective configuration . This configuration is timelessly and holistically encoded in the state’s Bell Energy Point (BEP) within .

Postulate III (Entanglement Constraint for the Singlet State). A two-body entangled singlet state, represented by a single BEP

, enforces a strict anti-correlation on the spin vectors of its two constituent Bell Fields (

):

where

and

are corresponding spheres as mapped by the Bell Identity.

1.1.6 N-Body State Representation ()

An N-body system in the DO model consists of quantum states. A “classical” object (e.g., a table) is not a separate category of energy; it is a single, N-body quantum state in the classical limit (where its kinetic spreading term approaches zero on the center of mass).

Dual representations.

Bell Energy Fields in . Each body

n has a quantum state descriptor

with occupied Bell Spheres

. The energy on sphere

is

. The combined occupied set is

Bell Energy Point in . The N-body system is represented as a single Bell Energy Point in , timelessly encoding the total energy , global quantum correlations, and all invariant properties.

Bell Identity (bijective mapping).

Occupied sets map componentwise:

Energy conservation (sum over components). The total energy equals the sum over all component supports and is time-invariant:

Through the Bell Identity, global coherence, entanglement, and all invariant properties reside in the N-body Bell Energy Point within ; updates there occur only by collapse and are mirrored to .

1.1.7 Discrete Operators

Time grid., step

.

Connectivity. On

let

be the Chebyshev hop distance and

A set is connected (notation ) if every two nodes in O are joined by a path in that lies in O. Let .

Local energies..

Kinetic operator. Weighted nearest-neighbor Laplacian on

:

Relational gravity operator. Shell-radial plus shell-tangential steering (Section 2.10):

These two operators are used in the Unified Evolution Equation (Section 2).

0.96 Equivalence consequence. The Inertial–Gravitational Energy Identity () is an ontological postulate. Applied to the Unified Evolution Equation, the resulting acceleration is independent of the test body’s mass. The operator-level proof in the N-body setting appears in Section 2.4.

Barriers. An impenetrable divider is enforced by for all cross-divider pairs ; this splits into disjoint connected components on which the operators act independently.

(Prototype kernels appear in Section 1.1.7.1.)

1.1.7.1 Link-Weight Prototype

The state-dependent link weights

define a dynamic relational metric on

. One concrete realization, detailed in Appendix B, is:

where

is the Chebyshev hop-distance, and

is obtained by inverting the discrete radial Poisson operator (see Appendix B for details). Any

is admissible in Appendix A. Appendix B uses a time-independent representative

; state-dependence enters through the sourcing energies in the operators.

1.1.8 Collapse Operator (C)

PD action and mirroring. Let

be the BEP of total energy

.

and, via

g,

The PD transformation is evaluated relative to SOAN (Section A), which remains unchanged by collapse and carries no energy or quantum numbers.

Admissible outcomes (single state). Let

and

. An outcome is any

with

; post-collapse,

Probability (energy fraction).

Proposition (Energy preservation at collapse).

Let

be the conserved intrinsic energy of the quantum state. If the collapse operator

C selects an admissible connected outcome

with pre-collapse energy

define the post-collapse energy samples by a single scalar rescaling on

:

Then total energy is preserved at collapse:

Proof. By construction, , and all energy outside is set to zero. □

Remark. Outcomes with have under the DO Probability Rule and are not realized, so is well-defined for realized outcomes.

Einstein boxes (corollary). If a barrier yields a partition of the pre-collapse support into two disjoint connected components,

then the collapse probabilities are the corresponding pre-collapse energy fractions:

and exactly one of

or

is realized.

N-body extension (factorized locality). For a unified

N-body BEP with bodies

, let

be body

n’s support (each may decompose into connected components by barriers). If PIs during one tick involve the index set

, then

and in

each

selects one connected

(contained in a single component if

is disconnected); the combined outcome set is

.

Joint probability (with alignment PI). With any alignment-PI reweighting

(see Section 3.1.1, Alignment PI),

(If no analyzer is present, omit this reweighting and use the unmodified .)

1.1.9 Minimal Axioms and Uniqueness Class for the Radial Link Kernel

Let denote the graph geodesic separation on the DS network. The radial link kernel is constrained by the DO ontology as follows.

Axioms.

-

A1

Symmetry: (equivalently ).

-

A2

Positivity: for all d.

-

A3

Monotone decay: for all .

-

A4

Smoothness (continuum limit): There exists a extension ; in particular exists for (used in Section 2.10).

-

A5

Scale fixing (amplitude reference): Choose a reference value

. The theory is invariant under the rescaling

so only ratios

(or the product

) are physical.

-

A6

Vanishing at range:.

-

A7

Emergent Lorentz symbol: In the dense-DS limit, the convolution operator

has low-wavevector symbol

with

(necessary for Lorentz-invariant recovery in Section 2.9).

Regularity assumption (graphs). Results that invoke the low-k symbol assume shells admitting approximate local isotropy and a finite spectral dimension ; graphs that violate shell isotropy or have degenerate spectral dimension are excluded from this analysis.

Asymptotics enforced by A1–A7. On graphs admitting an isotropic continuum embedding of spatial dimension

n,

with constants

,

fixed by

and the target symbol coefficient

C in

A7.

Any yields the same leading-order operator in the continuum limit and is therefore physically equivalent at long wavelengths; differences between members of appear only at . The prototype kernel given in Section 1.1.7.1 is a representative of .

Consequences. (i) exists and (through the centered–shell difference) determines the tangential coefficient (see Section 2.10); (ii) kernels outside violate at least one DO requirement (positivity/monotonicity, energy consistency, or Lorentz-symbol recovery).

Noether Theorem and gauge. Appendix A does not use continuous variational symmetries, gauge potentials, or Noether identities. The DO employs invariance and conservation statements that are discrete consequences of the pinned structure: (i) neutrality

⇒ zero response for the uniform mode; (ii) periodic, homogeneous convolution ⇒ shift-invariant updates; (iii) the two-step tick is algebraically reversible under the stated stability bound; (iv) collapse is handled by the Bell Identity as an exact mirroring (not a continuous flux). See

Section 7.5.

1.1.10 Guardrails (Discrete Geometry and Basis Checks)

G1 — Shell measure. For a selected observation shell with weights , the total weight equals to numerical precision: . This is a geometric sanity check on the shell quadrature.

G2 — Basis closure (M-orthonormality). For any computed modal block , the discrete inner-product metric M satisfies , verifying orthonormality of the working basis/eigenspace.

G3 — Parseval closure. Map-space and mode-space energies agree to numerical precision (Parseval consistency) under the same M, ensuring that projections and accumulations are lossless at the stated tolerance.

G4 — Fixed-law per run (immutability). For any stated result, the evolution map (time-stepping rule), operator coefficients, and boundary conditions are fixed for the entire run; no mid-run masking, rescaling, or operator edits are permitted.

G5 — Diagnostics are read-only. Any “identity”, “seed”, or “gate” functional maps fields to labels/statistics and never modifies or the operators used by Appendix A. Diagnostics may read and derived energies but cannot alter the update or its coefficients.

G6 — Self-adjoint spatial operator (real spectrum). Any spatial operator referenced in Appendix A is real and self-adjoint with respect to the inner product on the finite domain; hence its spectrum is real. This hypothesis underlies the energy functional and stability statements (Sections 2.3 and 2.4).

2 Quantum State Dynamics

Quantum state dynamics in the DO model comprise two processes:

The Bell Identity g (Section 1.1.5) ensures ontological correspondence between the state’s dual representations throughout these processes.

2.1 The Bell Identity (g)

Bell Identity g is the non-dynamical, bijective ontological mirroring between a quantum state’s dual representations in and , underpinned by Planck Identity (Section 1.1.4). Key mappings are:

Single State’s Bell Energy Field and Point:

N-body State’s Bell Energy Fields and Point:

Bell Sphere Collections (Bell Field/Bell Point Structures):

Properties of g:

Ontological Unitarity: Conserves state identity and total energy .

Timelessness of : There is no time in the Planck Domain.

Non-Dynamical: g is distinct from UEE-governed evolution.

Gravity absent in : No gravitational quantity is encoded in Planck-Domain Bell Points; gravity is absent in the PD and arises purely from relational differences in DS-localized energy in , with uniform backgrounds canceling.

SOAN neutrality: The mirroring g is defined relative to SOAN (Section A); SOAN carries no fields, adds no degrees of freedom, and anchors the timeless PD representation.

2.2 Relational Gravitational Influence

Relational curvature in the DO model is driven by the scalar energy distribution. For each Bell Sphere

b, the total scalar energy is defined as:

The gravitational source energy at sphere b is the energy of physical content on that sphere; the constant intrinsic energy (CIE) of Discrete Spheres is excluded. Electromagnetic, strong, and weak observables are diagnostic components of this source energy

Source Description (Ontological Components of ). The total energy is the single source for gravity. The observables of the non-gravitational forces are treated as different manifestations of this total energy, not as separate energies to be added.

Electromagnetic Observables: The quantities are observables on the DS graph, governed by "graph-Maxwell relations" (see Sec 2.5.2). The energy associated with these observables is given by (in internal units). This is not a separate energy, but an observable component of the total energy .

Short-range contact observables (strong/weak): The strong and weak interactions are represented as adjacency-limited contact interactions. The energy associated with these observables is defined by:

with nonnegative, contact-local exchange accounts

that vanish for

. These scalars also represent observable components of the total energy

.

Accounting. These observable components form a partition of the single source:

used only for diagnostics; gravity sees

alone.

The gravitational influence function uses the total, "catch-all" energy

:

where

is the radial link-weight of separation d (see Section 1.1.9).

The relational gravitational operator used in the UEE is

This operator is graph–intrinsic and background–independent. The scalar source enters gravitational dynamics through the bodies’ energies (with ) and the relational kernels; no additional “potential–times–” term is introduced.

2.3 Unified Evolution Equation (Single-State)

The Unified Evolution Equation (UEE) governs the discrete, deterministic evolution of any single coherent state descriptor

on the relational graph:

Here

by the Inertial–Gravitational Energy Identity in Section A, where

As defined in Sections 1.1.7 and 2.2. One concrete, symplectic leapfrog implementation of this update appears in Appendix B; alternative integrators may be employed.

Role split. The UEE updates the scalar energy state on the DS graph. Electromagnetic observables evolve by graph-Maxwell constraints/transport (discrete divergence/curl and continuity) on the same graph. There are no mediator fields; all updates are graph-intrinsic and share the invariant speed c.

The relative dominance of and dictates physical behavior:

Quantum Regime. dominates, yielding spreading of the state’s energy distribution; is a minor perturbation.

Classical Limit. For a non-dispersive “hard mass,” on its center-of-mass, and evolution is governed solely by , producing orbital motion.

2.4 Unified Evolution Equation (N-body Generalization)

The Unified Evolution Equation extends to an

N-body system. For each body

n with inertial parameter

and state descriptor

:

where

is the centered second difference (Section 1.1.7). The kinetic and relational-gravity operators are:

Concrete implementations (time steppers, stencils, kernels) appear in Appendix B; Appendix A remains method-agnostic.

Classical limit (centers of mass).

For non-dispersive “hard masses,”

on the center of mass, and the evolution reduces to pairwise curvature influence proportional to the source energies, yielding accelerations consistent with

Equivalence Consequence (DO).

With

,

so free-fall acceleration is independent of the test body’s energy

. For a narrow quantum wave-packet, the center of mass obeys the same limit since inertial response is

while curvature coupling depends only on source energies.

Local scope (component-wise).

For an

N-body state (entangled or not), the equivalence consequence holds per component. Each component

n responds to its local 4D environment:

If, at a given tick, the supports of different bodies lie in disconnected components under the relational connectivity (cf. Section 1.1.7), the law applies separately on each component; entanglement via the unified Bell Point does not create a single shared free-fall for the composite.

Proposition (Discrete angular-momentum conservation).

Consider

N bodies at sites

with energies

and

. Let the energy density be

on the discrete 4D graph, and let

K be a finite-range link operator with kernel

satisfying: (i) neutrality

, (ii) shell-isotropy/evenness

with coefficients depending only on

, (iii) discrete centrality so that

. Define

and the energy-weighted barycenter

. With periodic (or torque-free) boundaries, the total angular momentum

is invariant,

.

Proof. Write

. By linearity, shell-isotropy and evenness,

with

. Hence

Then

since

makes each cross product zero. Neutrality and periodic (or torque-free) boundaries exclude external torques. □

Remark. The “tangential” taps realize the centered-difference split that makes with spherically symmetric W; thus is discrete-radial and the central-pair argument applies verbatim.

2.4.1 Validation Protocols

Note. The checks listed here are illustrative and implementation-neutral; they do not presuppose any specific two- or three-body orbital scheme and can be restated for any admissible discretization. Detailed run protocols, when needed, belong in Appendix B (and full code in a separate artifact). To verify a correct implementation of the N-body UEE, one must monitor:

Barycenter Drift:, ensure remains below a chosen tolerance (see Appendix B).

-

Energy Conservation:

, reported relative to ; report RMS and final .

Angular Momentum Conservation:, reported relative to ; report RMS and final .

Operational identity (inertial = gravitational energy): For each body n, compare to the fitted source strength inferred from ; require .

Photon/EM audit (massless sector): Launch a localized EM packet past a massive source and verify angular deflection and redshift consistent with the field generated by the same source energies.

2.4.2 Symmetry and Linearity Gates (model-level)

Rotation-invariance (relabeling) gate. For any observable functional built from on with radial kernel satisfying Section 1.1.9, is invariant under rigid permutations of coordinate axes and node relabelings (including any element of the cubic symmetry group ). Operationally: recomputing after , , yields the same value up to numerical error.

-linearity probe. For any scalar , the map-level rescaling implies quadratic observables scale as ; in particular, any power-spectrum estimate satisfies (within numerical precision). These gates are used as implementation checks; they do not add model parameters.

2.4.3 Well-posedness and stability (discrete UEE)

Setting. Let

G be the discrete 3D lattice in

and let

be a symmetric, finite-range link operator with spectrum

(neutrality gives a null mode). Consider the linear update

for

with given

.

UEE–discretization map. Set and . Then the single-state UEE (A21) can be written in the form (A24).

Appendix Theorem (Existence/uniqueness and ℓ2 stability).

Assume . Then:

For any there exists a unique global sequence solving (A24).

-

In an orthonormal eigenbasis

of

K with

, the modal amplitudes

satisfy

With and , one has , hence uniform boundedness in n.

For

the two-step quadratic form

is conserved (

); for

it is nonincreasing. Summing over

j yields a positive-definite functional

that uniformly controls

.

Proof. Diagonalize K and analyze the scalar recurrences. The characteristic roots lie on or inside the unit circle iff , giving the trigonometric representation and boundedness; the conserved form follows by direct verification. □

Appendix Finite-propagation bound (locality).

If K has hop radius R, then the support of expands by at most R hops per tick. If one tick is factorized into M substeps using radius-1 kernels (or ), influence propagates by at most one hop per tick.

Proof. At site x, (A24) depends only on values within the R-hop neighborhood of x; proceed by induction on n. □

2.5 Fundamental Discrete Equations

2.5.1 Discrete Spinor Observables

The discrete evolution of spinor observables

at DS

a in

is governed by a discrete Dirac-type equation:

with discrete spinor Hamiltonian

The Dirac matrices satisfy

The discrete momentum operator acts via the relational kernel:

Scope (Dirac).

Spin and other fermionic observables are represented within the DS/BEP formalism; the DO does not posit an ontic spinor field. Dirac’s equation is treated as an effective continuum descriptor; measurable predictions correspond to discrete updates and collapse on the DS graph.

2.5.2 Discrete Maxwell Relations

Discrete Maxwell equations in the DO model utilize staggered relational structures, ensuring numerical stability and accuracy. Electric (

) and magnetic (

) fields at Bell Sphere

a evolve discretely according to:

Here and are the incidence-matrix divergence and curl on the staggered graph, chosen to satisfy discrete Gauss and Stokes. In internal units set ; restoration to SI follows the unit map in Scope and Linkage (Appendix A).

Discrete spatial operators , act on fields defined on a staggered grid configuration, where electric fields are assigned to Bell Sphere centers and magnetic fields to relational link midpoints between neighboring spheres. This explicit staggering provides a robust numerical scheme consistent with energy and divergence constraints.

The current and charge density at Bell Sphere a are determined from source state descriptors consistent with relational connectivity (Section 1.1.7).

Electromagnetic observables on the DS graph. The quantities E and B are operational observables defined on the DS graph ; they are not ontic background fields and do not introduce new degrees of freedom beyond the Bell Energy Field. “graph-Maxwell relations” denotes the discrete divergence/curl and charge–continuity relations these observables satisfy on . The electromagnetic energy per Discrete Sphere is , and this contributes to the single scalar energy budget used by the relational-gravity operator.

2.5.3 Scope and Consistency of Discrete Equations

The second-order UEE (KG-like) governs scalar Bell Energy Fields; the first-order discrete Dirac update governs spinor fields; and the discrete Maxwell block governs gauge fields.

Terminology (observables vs. fields). Throughout Appendix A, are operational observables defined on the DS graph (via graph divergence/curl and continuity constraints); they are not ontic background fields.

Role split. The UEE updates the scalar energy state on the DS graph. Electromagnetic observables evolve by graph-Maxwell constraints/transport (discrete divergence/curl and charge continuity) on the same graph. There are no mediator fields; all updates are graph-intrinsic and share the invariant speed c.

Ontological status (no independent mediator fields). No independent gauge fields or mediator particles are introduced in Appendix A for electromagnetism, the strong interaction, or the weak interaction. Their effects are represented entirely as observables and adjacency-limited energy exchanges built from the Bell Energy Field on the DS graph, with all contributions entering through the single scalar energy budget .

All three use the same graph calculus (discrete time steps , state-dependent , shell operators) and the same kernel class ; only one equation set is active per field species unless explicit couplings are introduced. This keeps the dynamics unified and avoids double-counting of degrees of freedom across species.

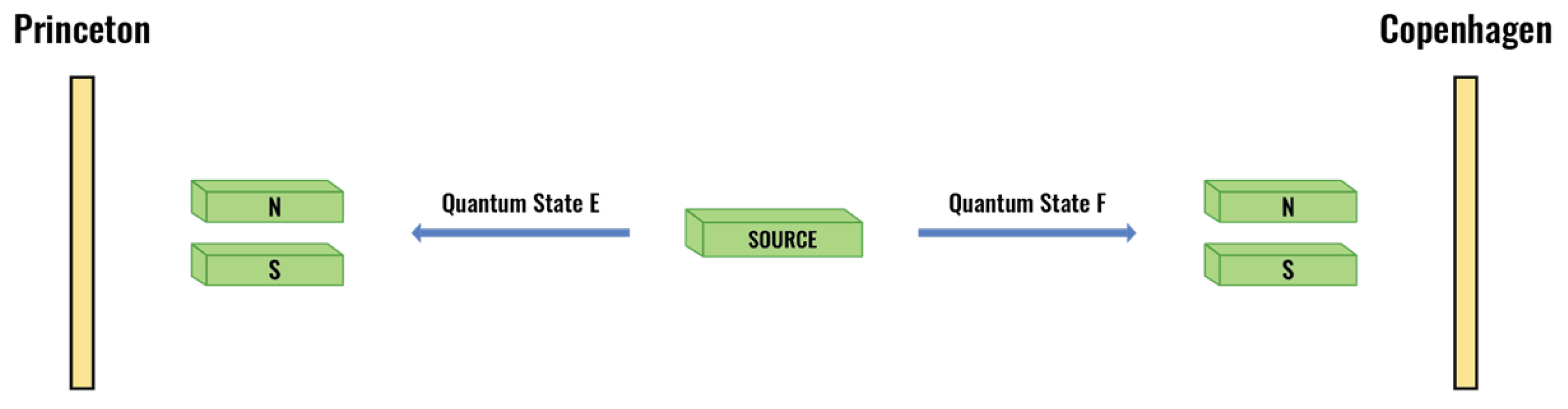

2.6 Bohm/EPR Entanglement in the DO Model

The DO model’s framework of dual representation and -based collapse provides a specific mechanism for understanding entanglement phenomena, such as in the Bohm formulation of the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) experiment.

2.6.1 Initial Entangled State Representation

An entangled system of two spin-½ quantum entities (A, B) in a singlet state is represented in the DO model as follows:

I. Representation (Bell Energy Point):

The system is represented by a single, unified two-body Bell Energy Point, , which holistically encodes the state’s total energy and its spin anti-correlations.

-

The spin anti-correlation is not an abstract attribute but an ontological constraint enforced by the BEP on its constituent Bell Spheres. This is formalized in Postulate III (Section 1.1.5.1), which dictates a strict anti-alignment of the intrinsic spin vectors (

) for any corresponding pair of spheres in the two-body field:

While the direction of any individual is indeterminate prior to collapse, the relationship defined in Equation (A32) is an absolute and defining property of the singlet state BEP.

Associated with is an N-body Bell Point (Section 1.1.6) comprising the constituents of all involved Bell Spheres.

II. Representation (Bell Energy Fields):

2.6.2 Collapse of the Entangled State

A Physical Interaction (PI) in

(

Section 3.1) involving entity A or B at time

triggers collapse.

I. Transformation in (Instantaneous Collapse):

The PI trigger is mirrored from to , initiating the instantaneous transformation of the N-body Bell Energy Point .

The Collapse Operator

C (Section 1.1.8) acts on

:

This transforms the single N-body Bell Energy Point into a product state configuration of two separable single-body Bell Energy Points, and .

These resultant Bell Energy Points represent definite, anti-correlated spin states for entities A and B respectively (e.g., if A is spin-up, represents spin-up, and represents spin-down).

II. Mirroring to (Transformation of Bell Energy Fields):

Via the Bell Identity

g (

Section 2.1), the

transformation (Equation (A33)) is mirrored to

at

.

The pre-collapse Bell Energy Fields (descriptors , ) transform into new, generally localized Bell Energy Fields.

These post-collapse fields,

and

, correspond to the definite outcomes for A and B, mapped from their respective

representations:

The product state nature of Equation (33) ensures manifestation of spin anti-correlations in , independent of the prior spatial separation of Bell Fields for A and B.

2.6.3 Collapse Correlation Rule

The observable correlation

between two analyzer axes

arises when the Bell Energy Point collapses in

, mirrored in

as localization of the Bell Energy Field to discrete outcomes

.Collapse conserves correlational content but amplifies the underlying alignment density by a dimensionless

Amplification Constant d:

Here is the physical average over the Bell Sphere population of the single unified state; for a singlet pair.

Dimensional derivation of . Let the interaction manifold have

degrees of freedom and let

be isotropic. With

and

,

Isotropy gives

and

, hence

The collapse map yields

, so

to reproduce the empirical

correlation. Corollaries: planar spin-

(

)

; fully 3D (

)

.

2.6.4 CHSH Bound (DO)

Setting. Section 1.1.1 yields, for planar spin-

with the singlet anti-alignment and rotational symmetry, the correlation

for unit measurement axes

in the plane and dichotomic outcomes

.

Theorem (CHSH bound ).

For any coplanar unit axes

and correlation

, the CHSH functional

satisfies

, with equality at the canonical

choice.

By Cauchy–Schwarz and

,

The right-hand side is maximized at , giving . Equality holds when and , e.g. with and . □

Remark. This bound follows directly from the DO correlation of Section 2.6.3 and does not invoke Hilbert-space machinery; Appendix B reproduces the same value in the CHSH validation.

2.6.5 DO-Locality Schema (Settings, PI, and No-Signal)

Terminology. A setting is a macroscopic device orientation or axis choice. A Physical Interaction (PI) is the localized coupling that triggers collapse.

Axiom (Free-Setting Independence; Operational).

Let

denote the pre-collapse Bell Energy Point. Let

be the macroscopic setting choices at two spacelike-separated PIs. For the purposes of device modeling the DO adopts the statistical independence

This is an operational assumption about devices, not a claim that global determinism (superdeterminism) is excluded. The DO remains agnostic on that question.

Theorem (Remote-Setting Invariance / No-Signal)

Under the DO Probability Rule (energy-fraction collapse; Section A.0.0.1), the marginal probabilities on one wing depend only on the pre-collapse energy within that wing’s region and are independent of the remote setting:

as proved in

Section 3.2. This result does

not require free-setting independence.

Statement (Single-outcome coupling; non-factorization).

A PD collapse selects a single admissible outcome

for the unified state; the mirrored

localization yields paired readouts on both wings from the

same selection. In general,

so factorization fails while remote-setting invariance and the operational free-setting axiom can both hold. This non-factorization underlies the correlation

used in Section 2.6.4.

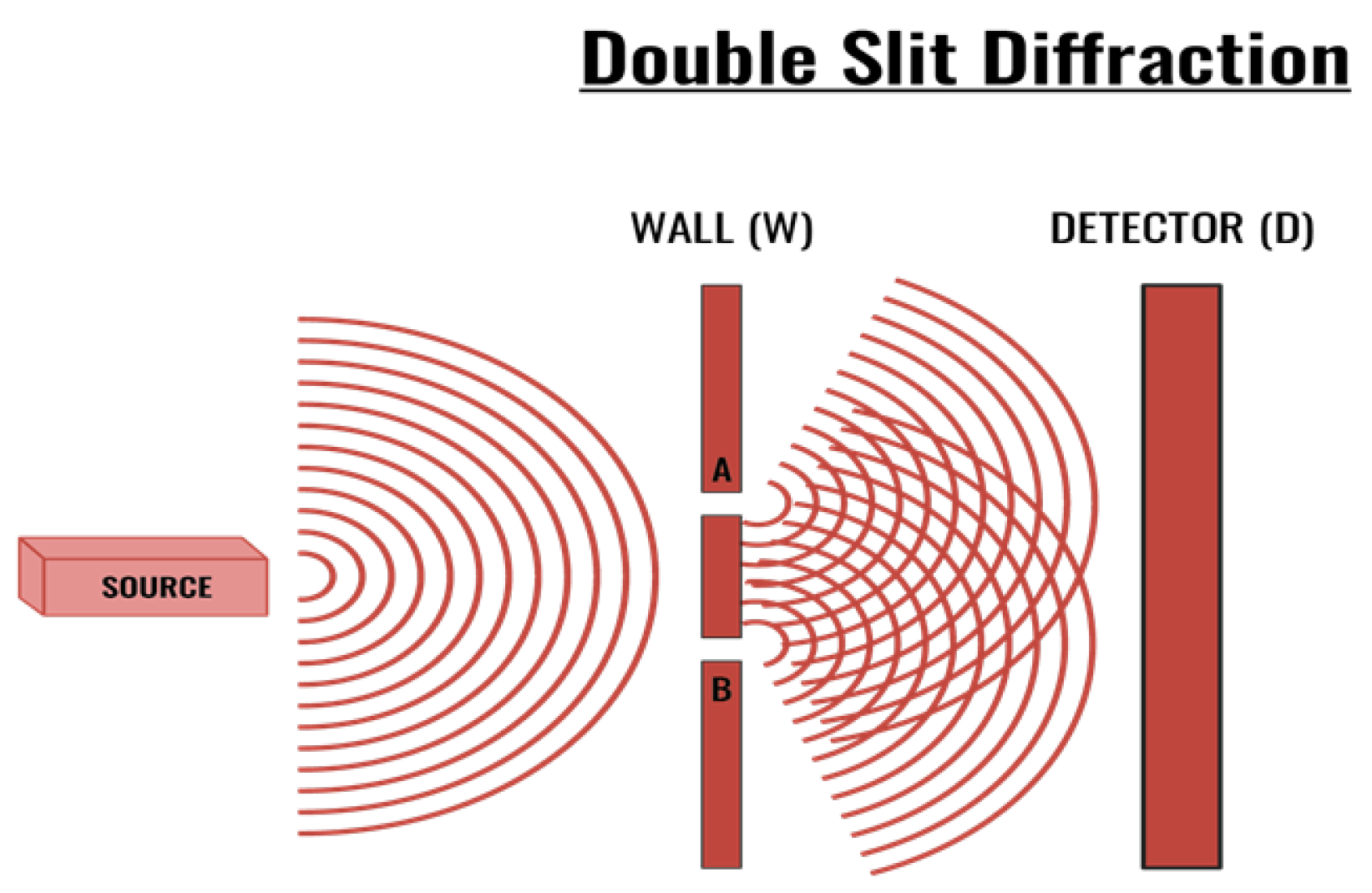

2.7 Double-Slit Experiment in the DO Model

The DO model provides a distinct ontological and dynamical account of the double-slit experiment, grounding its explanation in the physical distribution of the quantum state’s energy and the nature of its collapse.

2.7.1 Initial State and Coherent Multi-Site Occupancy in

A quantum state (total energy ) interacts with a two-slit barrier (slits A, B).

I. Post-Interaction Configuration (Bell Energy Field).

The state’s Bell Energy Field is a physically real scalar distribution over many Bell Spheres with two coherent components, and , associated predominantly with slits A and B.

Energy in component

is

where

is its occupied support.

In overlap regions the scalar descriptor combines coherently,

yielding the cross-term modulation of the

energy distribution on

.

No “superposition of location’’ in DO. The distributed set is a physically real multi-site energy occupancy, not a superposition of mutually exclusive particle positions. Location is represented only by which Bell Spheres in carry nonzero energy samples.

Total energy is conserved: .

II. Representation (Bell Energy Point).

The coherent multi-site occupancy corresponds to a single Bell Energy Point representing the indivisible total energy and other invariants.

Location is not a BEP observable. The BEP is timeless and metric-free; it carries no position information and admits no position operator. Spatial location is strictly a 4D property encoded by the occupied Bell Spheres and samples .

Bell Identity

g (Section 2.1) maps:

Ontological note (location in DO). Appendix A does not use a position operator. “Location’’ means the 4D occupancy set(s) and associated scalar energy samples on . For an N-body state, with (Section 1.1.6). These same act as sources for relational gravity (Section 2.2).

2.7.2 Collapse and Localization at Detection

A Physical Interaction (PI,

Section 3.1) in

with a detector at site

(a Bell Sphere within the pre-collapse field’s support where

) at time

triggers collapse.

Collapse Process & Outcome:

(Probabilistic determination of is per Section 2.7.3).

2.7.3 Interference Pattern Emergence from Probabilistic Localization

The interference pattern arises statistically from many independent localizations. Prior to detection, the

Bell Energy Field may have support on two components associated with the two slits,

and

.

There is no superposition of location in the DO. The local energy at a screen site

is determined by the

total scalar field value at that site, which is the sum of the component contributions:

When both components are nonzero at , the overlap term modulates across the screen, producing the familiar fringe statistics over many runs.

Probability of localization. Let

be the pre-detection support and

the conserved total energy. For any connected outcome

,

For localization to a single screen site

(outcome

),

Normalization holds: over all sites with .

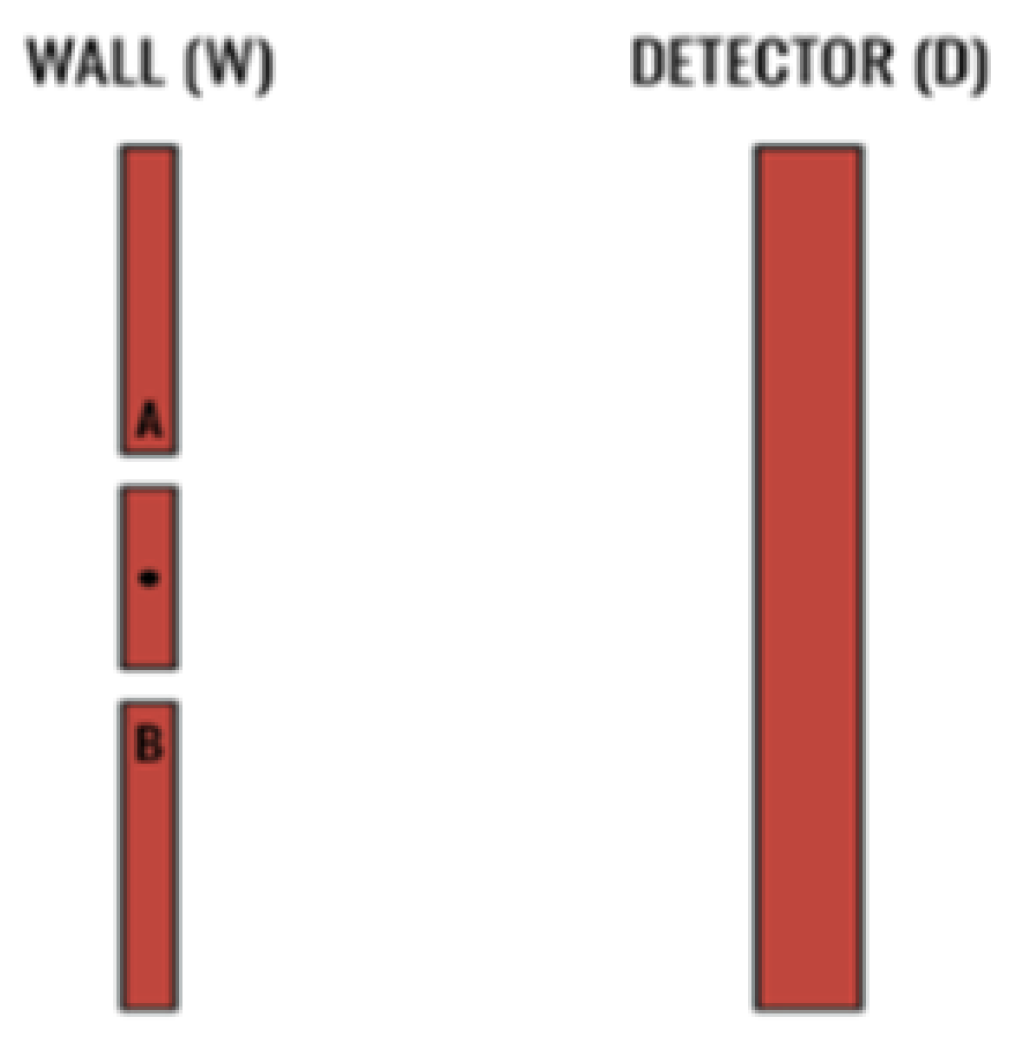

2.8 Which-Way Experiment in the DO Model

The DO model explains the outcome of which-way experiments by invoking a collapse event triggered by the which-way detection mechanism itself.

2.8.1 Initial State and Which-Way Detection Setup

A quantum state (total energy ) is directed towards a two-slit barrier (slits A, B), with a which-way detector (WWD) positioned to interact with the state near the slits.

Pre-Interaction State Representation (Prior to Slits/WWD):

(Bell Energy Field): Described by complex state descriptor , with .

(Bell Energy Point): A single Bell Energy Point, , representing and other intrinsic state properties.

Bell Identity g (Section 2.1): Ensures ontological mirroring:

.

2.8.2 Which-Way Detection as Collapse Trigger

A Physical Interaction (PI,

Section 3.1) between the quantum state (Section 2.8.1) and the which-way detector (WWD) in

near the slits at time

triggers collapse.

Collapse Process & Outcome:

Transformation: The PI mirrors to

, causing

to transform via Collapse Operator

C (Section 1.1.8). The outcome is a new Bell Energy Point,

, where

indicates the slit with which passage is now exclusively associated (e.g.,

for slit A). Outcome

X selection is probabilistic (per

Section 3.2), based on PI specifics and pre-collapse energy distribution of

near the slits.

Mirroring: Via Bell Identity

g (

Section 2.1), the

transformation

is mirrored to

at

. The state’s

Bell Energy Field localizes to

, configured as if the particle passed only through slit

X. This effective path localization precedes significant post-slit propagation that would otherwise lead to interference.

2.8.3 Absence of Interference Pattern

Post-collapse localization at slit (Section 2.8.2), the state propagates from this single origin to the final detector (Detector D).

No interference pattern forms at Detector D. The which-way PI collapses the BEP and restricts the

Bell Energy Field to a single connected subset that contains slit

X. After this event, the propagating field equals the single component

on its domain, so the energy on any screen site

satisfies

and the cross term

vanishes identically on the path to D. Operationally, the observed distribution is the single-slit pattern associated with

X, with no algebraic overlap of the

A and

B components and therefore no fringes.

2.9 Continuum Correspondence

The discrete relational framework of the DO model recovers the dynamical behavior of standard continuous theories when the energy distribution becomes dense and the link-weights vary smoothly over macroscopic scales. In that limit:

where

is defined in Section 1.1.7.1. Likewise, the kinetic term

reproduces

in the continuum limit,and the same

entering the relational operator

yields an emergent, classical curvature influence consistent with weak-field gravity.

Moreover, under nearly uniform

, the spectrum of

approaches the relativistic dispersion relation

and an effective light-cone structure emerges from the state-dependent network, recovering Lorentz invariance at long wavelengths. All continuum and relativistic features thus arise solely from the same dynamic link-weight network that governs both quantum propagation and curvature, without invoking any fixed background metric.

2.9.1 Continuum Correspondence of Operators

Assumptions. Dense occupancy and smooth link variation; (A1–A7). Let .

Operator limits (long wavelength).

Relational gravity (exchange form). With the shell split

,

one has the Fourier symbol

hence

at long wavelengths. No term of the form

appears; neutrality of the uniform mode is preserved.

Neutral mode. and (uniform mode unaffected).

2.9.2 Dispersion Relation and Emergent Special Relativity

Plane-wave analysis (uniform background). For

,

where

.

Long-wavelength limit.

recovering the SR dispersion. Group velocity

(Maxwell/Dirac blocks share the same c and yield the same bound.)

2.9.3 Bell Identity and Energy Conservation

Discrete conservation under UEE. Let

with

. There exists a positive definite functional

with pair forces

satisfying

, such that the UEE implies

Hence the total intrinsic energy is invariant during evolution; at collapse, is preserved by construction (Bell Identity), with support restricted to the selected connected set.

2.9.4 Well-Posedness, Causality, and Stability

Domain of dependence (causal bound). For radius-1 spatial stencils and two-level time updates,

(Maximal front speed hop/tick .)

Energy-preserving update (existence/uniqueness). The discrete-gradient scheme

admits a solution for any

; if

is Lipschitz on the energy sublevel set of

, the solution is unique. It preserves

exactly:

.

Stability and continuity. Energy preservation ⇒ uniform boundedness of ; the one-step map is Lipschitz on sublevel sets ⇒ continuous dependence on initial data.

Local SR reduction. On small, freely falling patches with nearly uniform , the UEE reduces to the SR dispersion of Section 2.9.2 for non-gravitational dynamics; tidal corrections enter via gradients of w.

2.9.5 -Amplitude Mapping (Operational Calibration)

The discrete pipeline yields dimensionless bandpowers

. Comparison to observational means

uses a single global factor on

power. Define

and minimize, over a designated multipole set

L,

and report

. This calibration fixes units only; spectral shape and correlation structure arise from the non-perturbative dynamics. For display we use

.

2.10 Tangential Steering from Shell Isotropy

Let

be the finite DS network with graph geodesic distance

. For

and

, define the

a-centered shell

Let denote the radial link kernel (cf. Sections 1.1.7 and 1.1.7.1).

Radial operator. The central (radial) contribution acting on

at node

a is

Shell restriction and intra-shell Laplacian. For fixed

a and

k, let

be the subgraph induced by

with edge set

Define the combinatorial intra-shell Laplacian contribution “at

a via its shell neighbors” by

This operator is shell-isotropic (annihilates shell-constant fields; equivariant under shell automorphisms).

Tangential operator (definition). The tangential steering is the unique shell-isotropic, pairwise-antisymmetric operator orthogonal to the radial direction, hence

with a scalar coefficient

depending only on the shell index

k.

Action and coefficient identification. Consider the edge-wise action

Its discrete Euler operator

yields the evolution force. Variation under infinitesimal reparameterizations within

generates an intra-shell flux proportional to

, giving the split

Properties. (i) Energy consistency: equals the discrete Euler operator of (44), hence preserves the energy functional in Section 1.1.1. (ii) Shell isotropy: vanishes on shell-constant and commutes with shell automorphisms. (iii) Uniqueness: any shell-isotropic, divergence-free tangential operator compatible with (44) is a scalar multiple of per shell; energy consistency fixes the centered-difference coefficient , which approximates for smooth .

Relational gravity operator. The effective discrete operator is

All objects are graph-intrinsic (shells, induced subgraphs, combinatorial Laplacians); no background metric is introduced. No gravitational quantity is encoded in Planck-Domain Bell Points; gravity is absent in the PD and arises purely from relational differences in DS-localized energy in , with uniform backgrounds canceling.

2.11 Ontological Assumptions and Dependency Map

This subsection records the minimal ontological/mathematical assumptions used in Appendix A and maps them to the derived results, to make explicit that no auxiliary postulates or free parameters are introduced.

Foundational Assumptions (FA).

-

FA1

Discrete Spheres (DS): Finite network with graph geodesic distance .

-

FA2

Symmetry: and depends only on .

-

FA3

Kernel class: (positivity, monotone decay, , normalization, asymptotics, symbol), per Section 1.1.9.

-

FA4

Energy conservation between collapses: total intrinsic energy is constant (Section 1.1.1).

-

FA5

Isotropy (interaction/alignment manifold): uniform distribution on for latent directions in correlation calculations (Section 1.1.1).

-

FA6

Locality of collapse: selection of a connected subset under the connectivity (Section 1.1.8).

Derived Results (DR) and Dependencies.

DR1 — Collapse Operator C (Section 1.1.8): depends on FA1, FA4, FA6.

DR2 — Tangential steering (Section 2.10): depends on FA1, FA2, FA3.

DR3 — Amplification constant (Section 1.1.1): depends on FA1, FA5.

DR4 — Exact energy conservation for the UEE (Section 1.1.1): depends on FA1, FA2, FA4.

DR5 — UEE well-posedness and stability (Section 1.1.1): depends on FA1, FA2, FA3, FA4.

DR6 — Kernel uniqueness class (Section 1.1.1): depends on FA1, FA2, continuum-limit Lorentz recovery.

Consistency. DR1–DR6 require only FA1–FA6 (and the continuum-limit symbol condition in FA3); no additional postulates, free parameters, or perturbative techniques are introduced. Dependencies are acyclic.

3 Physical Implications of the DO Model

3.1 Physical Triggers for Collapse

Collapse of a state’s Bell Energy Point (

) is triggered by a Physical Interaction (PI) in

(Section 1.1.8). Conventionally, such PIs correspond to

In the DO model these labels serve only as traditional force-category names. Fundamentally, every PI is a discrete, contiguous exchange of local energy

(as defined in the Source Catalog of

Section 2.2) along one or more links

in the relational network

(Section 1.1.2). After such an energy exchange, the collapse operator

C may act (Section 1.1.8). Quantitative thresholds for PI triggering are not specified in Appendix A.

3.1.1 Alignment PI (Spin-Axis Interaction)

Postulate IV (Alignment PI). A spin-axis interaction along analyzer axis

constitutes a Physical Interaction (PI) that triggers collapse. The PI imposes an alignment-dependent potential on the pre-collapse Bell Energy Field, remodulating local energies on Bell Sphere

a by

Definitions.

: local energy on sphere a immediately before the PI.

: interaction-strength parameter, constrained so that for all a.

: intrinsic spin vector on sphere a; : unit analyzer axis.

: pre-collapse occupied Bell Spheres; .

Energy conservation (no renormalization).

3.2 Collapse Probabilities from Energy Distribution

Collapse probabilities in the DO model derive from the physical distribution of the quantum state’s total intrinsic energy, , across its pre-collapse () Bell Energy Field (occupied Bell Spheres ). Energy on an individual Bell Sphere is (Section 1.1.5).

Postulate (DO Probability Rule): Collapse (triggered by PI,

Section 3.1; enacted by

C, Section 1.1.8) localizes

onto a subset

of Bell Spheres. The probability,

, of collapse to configuration

is the fraction of

within

at

:

where

is energy in

. If

are outcome configurations that together span

, then

.

This discrete probability rule, based on physical energy distribution, avoids continuous probability densities over abstract spaces. Ontological unitarity (

Section 2.1, via Bell Identity) underpins this by ensuring conserved

and state identity.

Appendix Proposition (No-signaling under energy-fraction collapse).

Let the pre-collapse support decompose as a disjoint union

with energy samples

and total

. For any local choice

s at

A, let

be a pairwise-disjoint family that together spans

(i.e.

). Fix any pairwise-disjoint family

that together spans

. For each admissible connected outcome

, let

Define Bob’s coarse event

as the disjoint union of its connected members in

. Then Bob’s marginal probability is

which is independent of the choice of

(and hence of

s). Therefore the distribution

is the same for all local settings

s at

A.

Proof. Because

is pairwise disjoint and together spans

, additivity of

over disjoint unions gives

The construction does not reference , so is independent of s. □

Remark. The statement is a marginal-invariance property: remote settings only refine the partition of and cannot alter the pre-collapse energy share inside any .

3.3 Tunneling as Collapse Localization

Quantum tunneling is interpreted as probabilistic collapse localization. If a state’s

Bell Energy Field (

) has non-zero energy portion

in a classically forbidden region (subset of Bell Spheres

), a Physical Interaction (PI,

Section 3.1) can trigger collapse localizing the state to

.

Probability of Tunneling (Application of DO Probability Rule): The probability,

, for this tunneling outcome is per Equation (A48):

where

is total state energy. This localization to

is an instantaneous

event mirrored to

; no physical traversal of energy through the barrier occurs during the tunneling event itself.

4 Bell’s Theorem, Locality, and Simultaneity

The DO model’s ontology—dual state representation (, ), Bell Identity (Section 1.1.5, 2.1), and -based collapse (Section 1.1.8)—provides the conceptual and formal basis for addressing Bell’s Theorem and related locality/simultaneity issues.

Detailed arguments on how these foundational DO principles resolve associated paradoxes (e.g., EPR non-locality, consistency with Special Relativistic principles) are in the main text. This Appendix formalizes DO model mathematical/dynamical rules. Implications for Bell’s Theorem, locality, and simultaneity are direct consequences of the structure established in Appendix A. No further specific derivations or discussions on these topics are presented in this Appendix.

5 Quantum Path Irreversibility and the Arrow of Time

The DO model’s two distinct dynamical processes, deterministic evolution of Bell Energy Fields in

via the UEE, and the instantaneous, non-reversible collapse of Bell Energy Points in

, provide an ontological basis for the arrow of time. The Bohm/EPR experiment (detailed in

Section 2.6) serves as an illustrative example.

5.1 State Configuration Pre- and Post-Entangled Collapse

Consider the entangled two-spin-

system (A, B) from

Section 2.6.

I. Pre-Collapse State (Entangled): (As detailed in Section 2.6.1)

: Single N-body Bell Energy Point (BEP) , encoding total energy and spin correlations.

: Two Bell Energy Fields (

,

), evolving per UEE (

Section 2.4).

Mapping (Bell Identity g): System of fields g single N-body BEP.

II. Post-Collapse State (Separable Product): Triggered by a Physical Interaction (PI) in at (Section 2.6.2).

Transformation (Collapse Operator C): The Collapse Operator C transforms into a product of separable single-body Bell Energy Points (, ) representing definite, anti-correlated outcomes.

Mirroring: Pre-collapse fields transform to new, localized fields (, ) corresponding to definite outcomes.

The system transitions from a non-separable entangled state to a separable product state.

5.2 Intrinsic Irreversibility of Collapse

Post-collapse (at

), localized

Bell Energy Fields (

Section 5.1) evolve via UEE. The arrow of time is posited to arise from the intrinsic non-reversibility of the

collapse event

.

Postulate (Non-Reversible Collapse): An inverse collapse operator, , acting on to restore the unique pre-collapse N-body Bell Energy Point , is postulated not to exist.

Justifications for Non-Reversibility in :

Ontological State Change: Transformation from an N-body BEP to separable single-body BEPs represents a fundamental change in ontological structure.

Cessation of Pre-Collapse Configuration: The specific holistic configuration of ceases to exist upon collapse.

Absence of Reversal Dynamics: is intrinsically timeless (Section 1.1.3) and lacks mechanisms to dynamically reverse the ontological splitting of a BEP.

Fundamental Information Transformation: The entanglement correlations uniquely characterizing are fundamentally altered to product state correlations.

Implication (Arrow of Time in ). The non-reversible

collapse implies non-reversible consequences for the

Bell Energy Field, namely a restriction of support from a many-site energy distribution to a localized connected subset. While the UEE governing evolution between collapses may be T-invariant, collapse events themselves introduce a fundamental directionality, forming a basis for the arrow of time in

for processes involving such events:

6.1 Singularity Resolution

General Relativistic (GR) singularities, characterized by diverging quantities (e.g., mass–energy density

), are avoided in the DO model. This resolution arises from the postulate that

is composed of Discrete Spheres (DS), each with an irreducible, invariant minimum volume

fixed to the Planck volume:

The existence of

imposes a fundamental spatial compression limit. Additionally, each Discrete Sphere is postulated to have a maximum intrinsic energy capacity

. Thus, the maximum attainable energy density within any DS is finite and defined as:

Finite and inherently prevent infinite densities, resolving the conditions leading to GR singularities.

6.2 UV Regularization and Vacuum Energy

Quantum Field Theory (QFT) ultraviolet (UV) divergences (e.g., from summing quantum field zero-point energies) are intrinsically resolved by the DO model’s discrete ontology.

fundamental discreteness, composed of Discrete Spheres (DS) with invariant volume (Equation (A50)) and maximum intrinsic energy capacity per sphere (Section 6.1), imposes a natural physical UV cutoff. This implies a maximum mode energy (related to or scales like , Section 2.9.2) and thus maximum momentum. Such a cutoff regularizes field mode sums/integrals, precluding QFT divergences from arbitrarily high energy contributions.

Under the DO, quantum state energy exists exclusively as portions

(the total scalar energy budget from all sources, per

Section 2.2) localized on occupied Bell Spheres

(Section 1.1.5). Unoccupied DS (not part of any Bell Field) are posited to contain no fluctuating quantum field zero-point energies. Consequently, the QFT concept of pervasive, non-zero vacuum energy density from such fluctuations is absent:

This absence of QFT-derived vacuum energy is distinct from DO’s cosmological constant

(

Section 7.4), attributed to intrinsic DS energy. This distinction helps avoid the QFT vacuum energy component of the "cosmological constant problem."

6.3 Background Independence in Gravitational Dynamics

The DO model’s gravitational dynamics are inherently background-independent. No fixed, pre-existing geometric background exists; geometry emerges dynamically from the distribution of energy .

Mechanism of Background Independence:

UEE Evolution: State descriptors evolve via the Unified Evolution Equation (UEE, Sections 2.3 and 2.4).

State-dependent Operators: Effective Relational Kinetic Operators (, Section 1.1.7.1) dynamically define gravitational interactions based solely on the current energy distribution.

Relational Graph Metric: The relational fabric arises explicitly through link weights:

which define kinetic propagation and gravitational effects.

Dynamic Feedback Loop: The relational fabric and energy distribution co-evolve, dynamically determining effective spacetime geometry without external references.

This feedback mechanism guarantees intrinsic background independence, with external influences entering only via explicitly non-gravitational potentials, .

6.4 Time in the DO Model

The DO model treats time distinctly in its two primary ontological domains:

(Planck Domain): Intrinsically timeless (, Equation (5)). It is the static ontological backdrop for instantaneous collapse events, enacted by Collapse Operator C (Section 1.1.8).

(Discrete 4D Spacetime): Incorporates discrete coordinate time t, progressing in fundamental steps . Evolution of state descriptors in is governed by UEE formalism (Sections 2.3, 2.4).

Emergent Special Relativistic (SR) principles (Section 2.9.2) apply in

under appropriate macroscopic/long-wavelength limits (e.g., wavelengths

;

is DS volume, Equation (50)). In such regimes, proper time interval

for an entity

n (velocity

) relates to coordinate time step

via time dilation:

where

c is invariant speed (DO fundamental constant).

is UEE’s fundamental time interval.

A state’s Bell Energy Point collapse in

(via operator

C) is mirrored by Bell Identity

g (

Section 2.1) to

. This mirroring transforms the

Bell Energy Field at a fixed coordinate time

:

This Bell Energy Field transition (pre- to post-collapse/localized) is considered instantaneous in coordinate time (i.e., duration effectively zero, or within one step without intermediate states).

Causal cone (hop form). With hop/tick, the forward light cone from after ticks is ; null paths use exactly one hop per tick, timelike fewer, spacelike more.

6.5 Relational Energy Operator and Non-Quantizability

Definition (4D gravitational exchange).

Gravity enters only through this state-dependent exchange operator inside the UEE; there is no independent gravitational potential V multiplying .

Category statement (intrinsic non-quantizability). There is no separate gravitational degree of freedom to promote: no canonical pair , no , no graviton operators. Quantization targets remain the scalar state ; is a functional of those variables, not an independent field.

Background independence via

; all gravitational effects are carried by the same kernel class as kinetics:

6.6 Relative Strengths of Gravitational and Other Interactions

Scaling rules.

- (I)

-

Strong/Weak (contact).

. Per-site effect .

- (II)

-

Electromagnetism (shell dilution).

. Per-site amplitude .

- (III)

-

Relational gravity (neutral, high-pass).

Small-k suppression.

Ordering (effective strength).

6.7 Black Hole Information (PD Anchoring)

Invariants in . Let

denote conserved labels stored in the BEP. Collapse acts in

and mirrors to

:

with

No loss. Information carried by is preserved at the BEP level; 4D coarse-grained outflows (Hawking-like radiation) inherit those conserved labels via g. These invariants are stored at the BEP level relative to SOAN (Section A); SOAN itself stores no additional data.

No singularity. Bounded DS volume

and maximum per-sphere energy

imply

precluding divergent densities during collapse/evaporation.

7.1 State of at Heat Death ()

As cosmic time

(Heat Death), the matter/radiation in

approaches maximal entropy and zero available work capacity (

). This state is consistent with a spatially flat (

), critical density (

) FLRW model:

where

is DO gravitational entropy.

undergoes continued accelerated expansion, driven by

(

Section 7.4).

Universal State Representation at (Total Energy ):

(Universal Bell Energy Field - UBEF): Described by state descriptor , with .

(Universal Bell Energy Point - UBEP): Denoted , timelessly representing and all other conserved universal state properties.

Bell Identity g (Section 2.1):.

The subsequent collapse of this UBEP,

, initiates a new cosmological epoch at

(

Section 7.2).

7.2 Cosmological Collapse Transition ()

The transition from cosmological Heat Death (

) to a new cosmological epoch at

is posited as a universal-scale collapse event, analogous to instantaneous collapse events described for spatially separated

N-body quantum states (Section 1.1.8, 3.1). The Universal Bell Energy Point (UBEP),

, undergoes instantaneous collapse triggered by a Physical Interaction (PI) in

transforming to a localized UBEP at

:

The UBEP transformation is defined relative to SOAN ((Section A); SOAN supplies the neutral, timeless reference for the

localization. This instantaneous event, mirrored to

via the Bell Identity

g, induces a generalized localization of the Universal Bell Energy Field (UBEF):

Critical properties and outcomes of this cosmological collapse are:

Instantaneous Global Simultaneity: Collapse is simultaneous across the entirety of , ensuring a homogeneous transition preserving large-scale isotropy. Deviations in timing would introduce unwanted anisotropies and violate causal continuity.

Preservation of Homogeneity and Isotropy: Due to the extreme uniformity of , the collapse event maintains isotropy and homogeneity at . This intrinsic preservation removes the necessity for fine-tuned initial conditions.

Finite Energy Density, Pressure, and Temperature at : The DO model’s discrete ontology eliminates divergences, resulting in extreme but finite physical parameters at the cosmological transition, thus resolving conventional singularities associated with .

Entropy Reset: The instantaneous localization from the dispersed state at Heat Death resets gravitational entropy from near-maximal at to minimal at . This entropy reset establishes conditions necessary for the new cosmological epoch.

Invariant Structural Framework: The Discrete Sphere ontology (identities and volumes) remains invariant throughout collapse, providing a stable and consistent underlying spacetime framework; the occupied Bell Sphere support of fields may change, but DS sizes do not.

Independence from Relational Gravity Dynamics: While gravitational interactions in the DO model are relationally embedded within the UEE formalism (Sections 2.3 and 2.4), the instantaneous cosmological collapse itself does not rely explicitly on gravitational relational dynamics. Rather, collapse mirrors quantum state localization mechanisms directly applicable to general N-body quantum state scenarios, independent of the ongoing research complexities inherent in relational gravity.

7.3 Expansion, , and Energy Dynamics

Energy accounting (DS intrinsic density ).

Dilution laws and equation of state.

7.4 Properties and Stability (Discrete Spheres)

Origin (PD-4D mapping). Intrinsic DS energy attribute (in ) ⟷ constant 4D density under g; expansion increases but not .

7.5 Hierarchy Problem (Discrete Cutoff + Relational Neutrality)

(1) Discreteness ⇒ physical UV cutoff. Lattice spacing

gives Brillouin zone

; for any integrand

f,

(2) Relational gravity does not renormalize BEP parameters.

so uniform modes (BEP-intrinsic labels) are untouched; no Planck-scale gravitational dressing of electroweak parameters.

(3) Observed ordering (from Section 6.6).

Appendix B. Relational Gravity and Quantum Nonlocality Validation Models

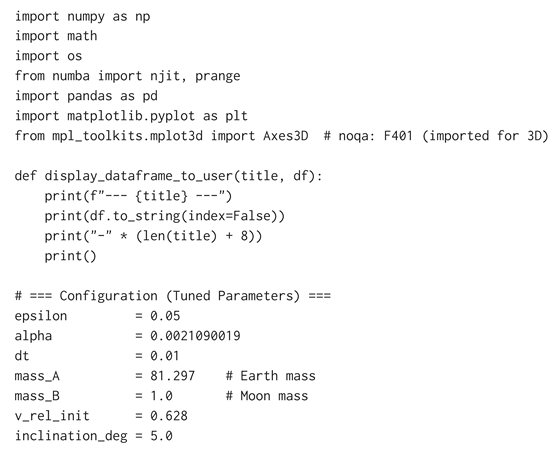

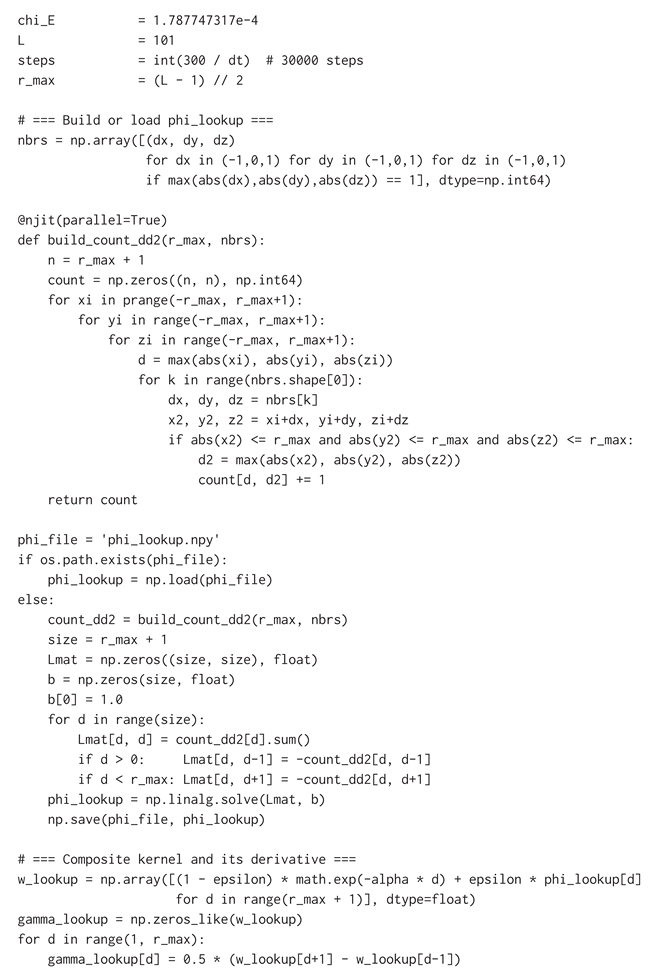

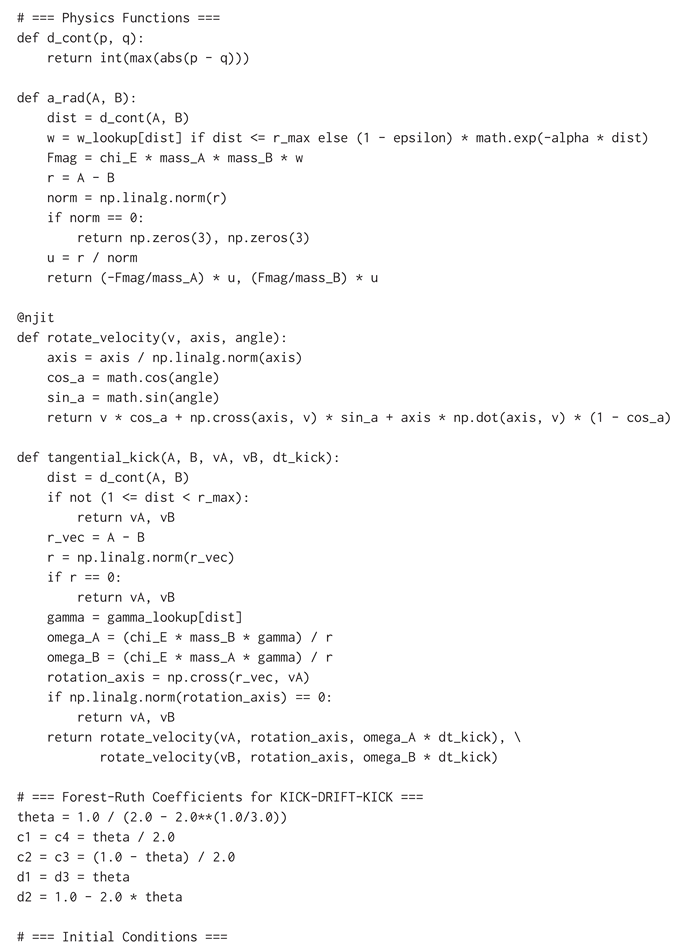

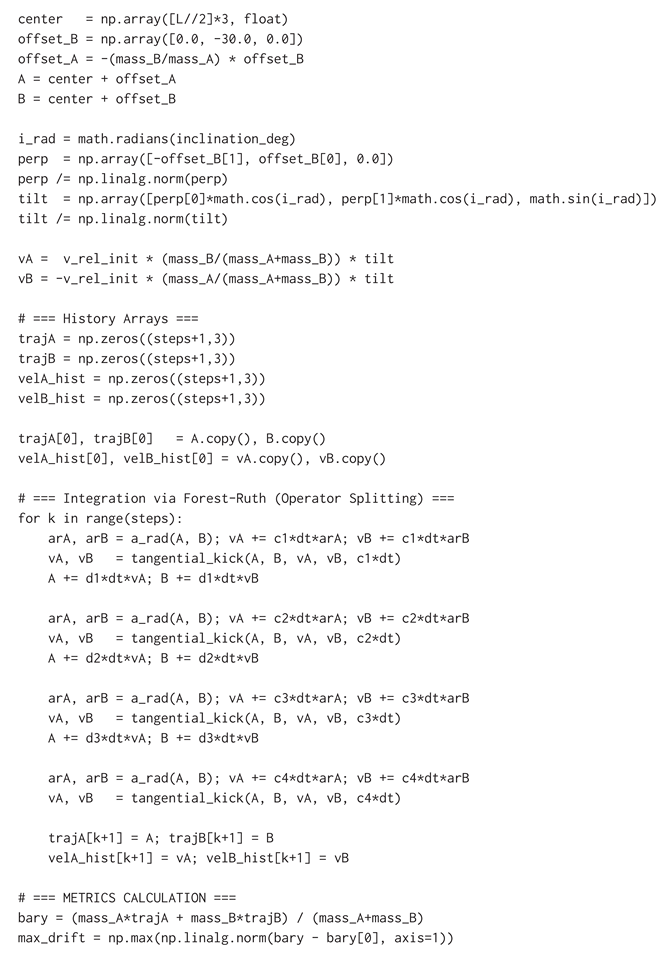

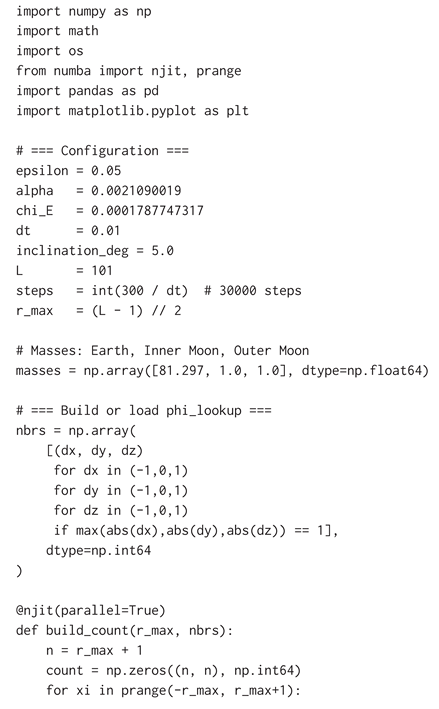

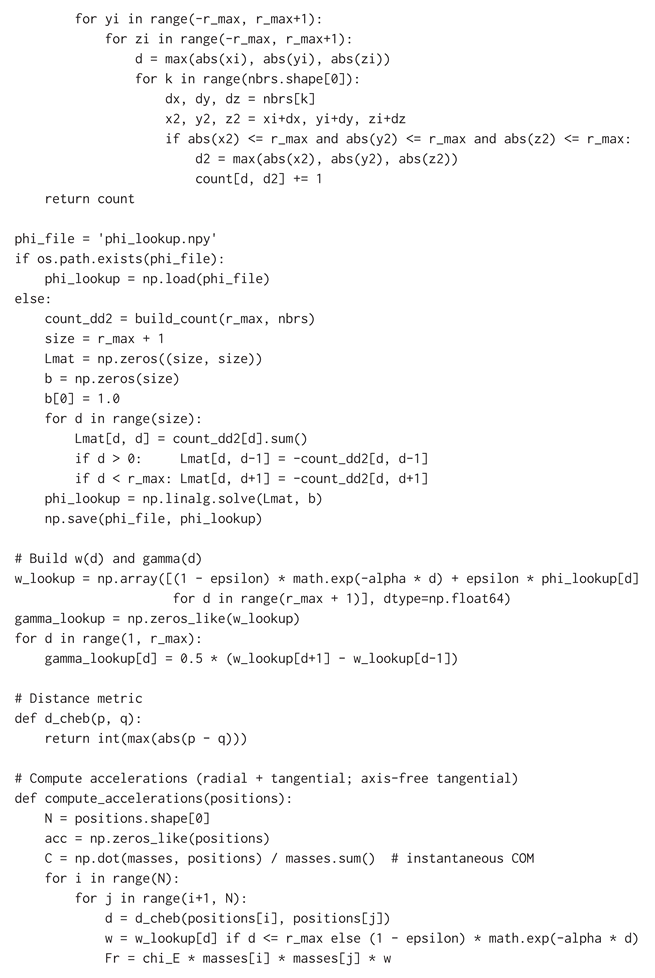

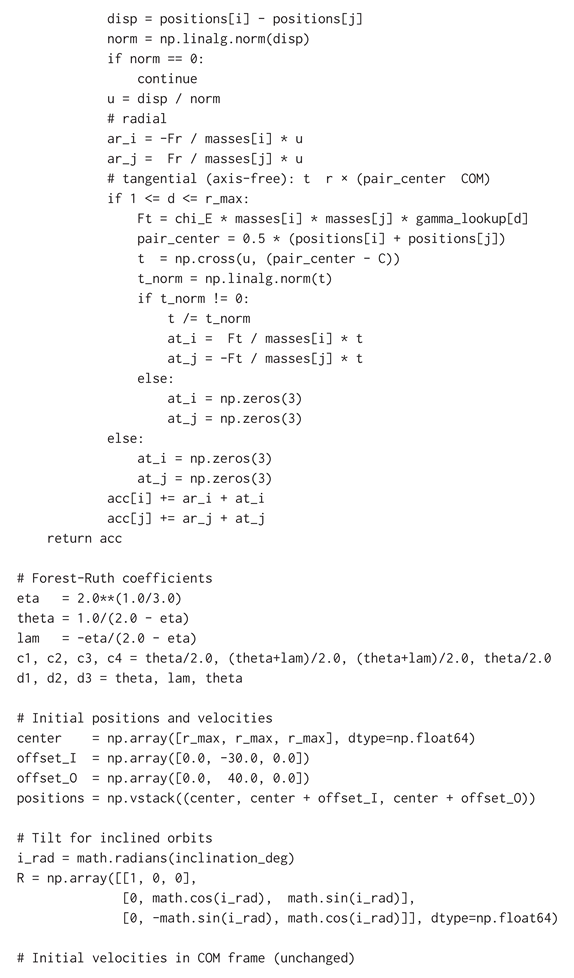

Appendix B integrates five rigorous numerical validations derived entirely from the unified, background–independent, discrete ontology, relational gravity and quantum dynamics of the Dual Ontology (DO) model as formalized in Appendix A. The validations avoid Hilbert spaces and matrix mechanics, non-relativistic Schrödinger equations, continuum field PDEs, Euclidean/Newtonian or EFE formulations, ad-hoc methods, fine-tuning, and perturbative approximations. Each test holds the operator and update fixed, enforces DO invariances and neutrality, and is audited by explicit gates.

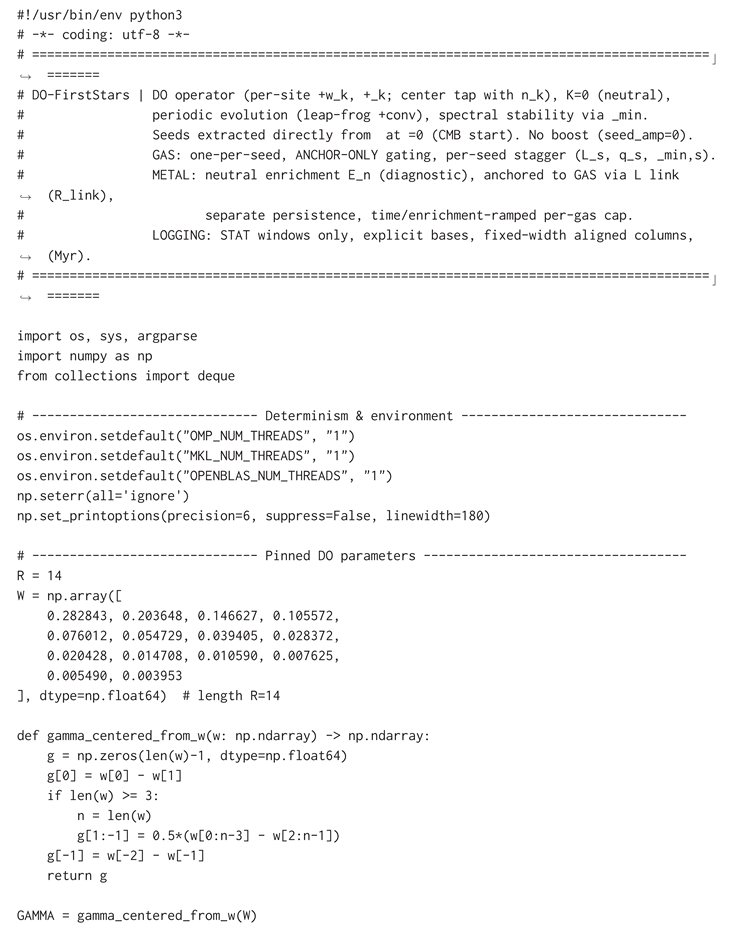

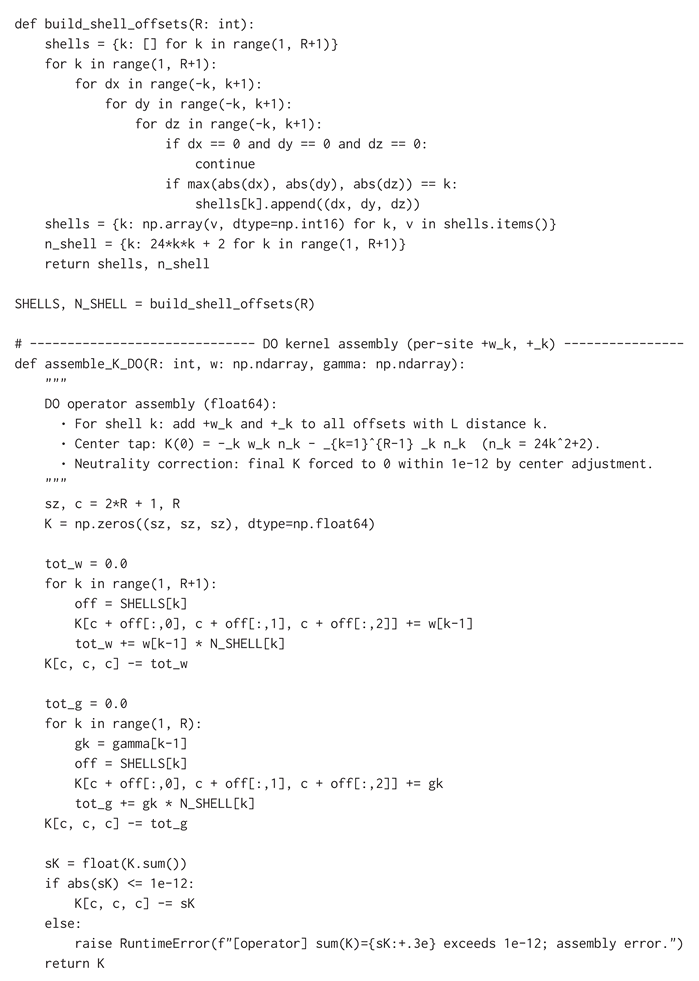

Operator and collapse linkage. Validations I, II, IV–A, and IV–B use the single energy–based operator from Appendix A (kernel class ; centered–difference shell coefficient ; radial central–force magnitude applied along ; uniform mode neutral, ) and the deterministic Unified Evolution Equation (UEE).

As-run note (IV–B). The three-body demonstrator retains the radial magnitude

and uses an axis-free rule for the tangential direction derived from the instantaneous state (details in IV–B). This axis-free rule is background-independent but is not the exact shell-isotropic intra-shell construction of Appendix A.

Validation III (CHSH) uses only the Planck–Domain collapse rule mirrored into and does not employ the operator or the UEE. Where the operator is used, the framework is fixed across runs; differences include grid size, run length, initial conditions/seeds, and diagnostic gating thresholds. In Validation I a single global amplitude on power is fitted for display/comparison only and is not a parameter of the theory.

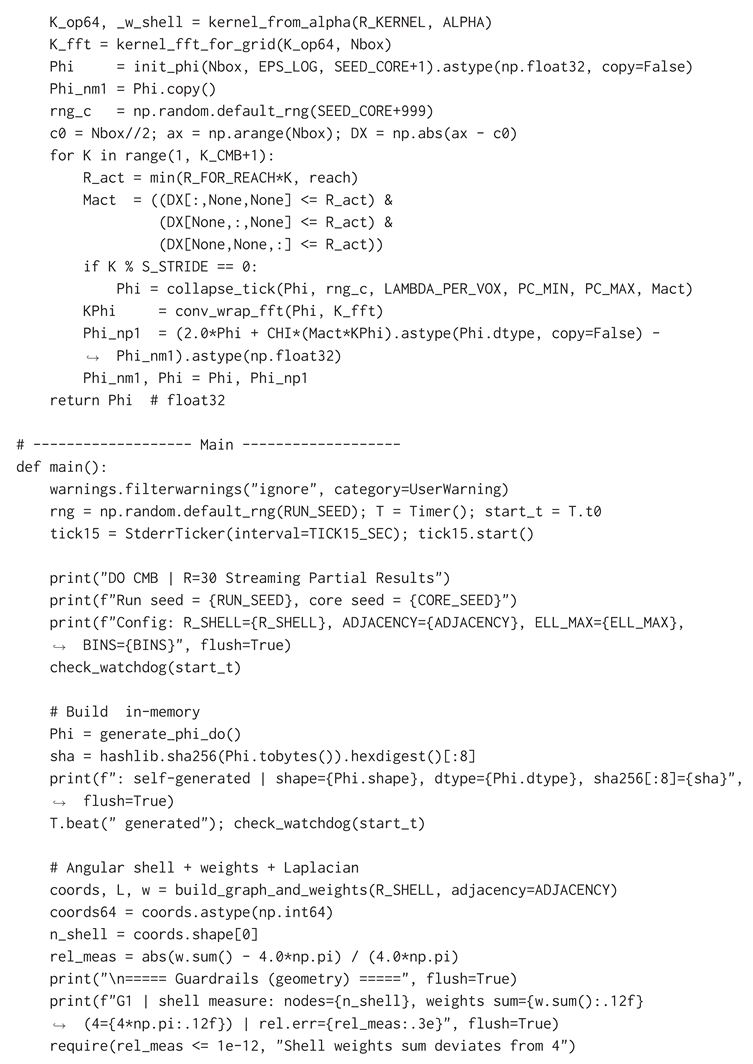

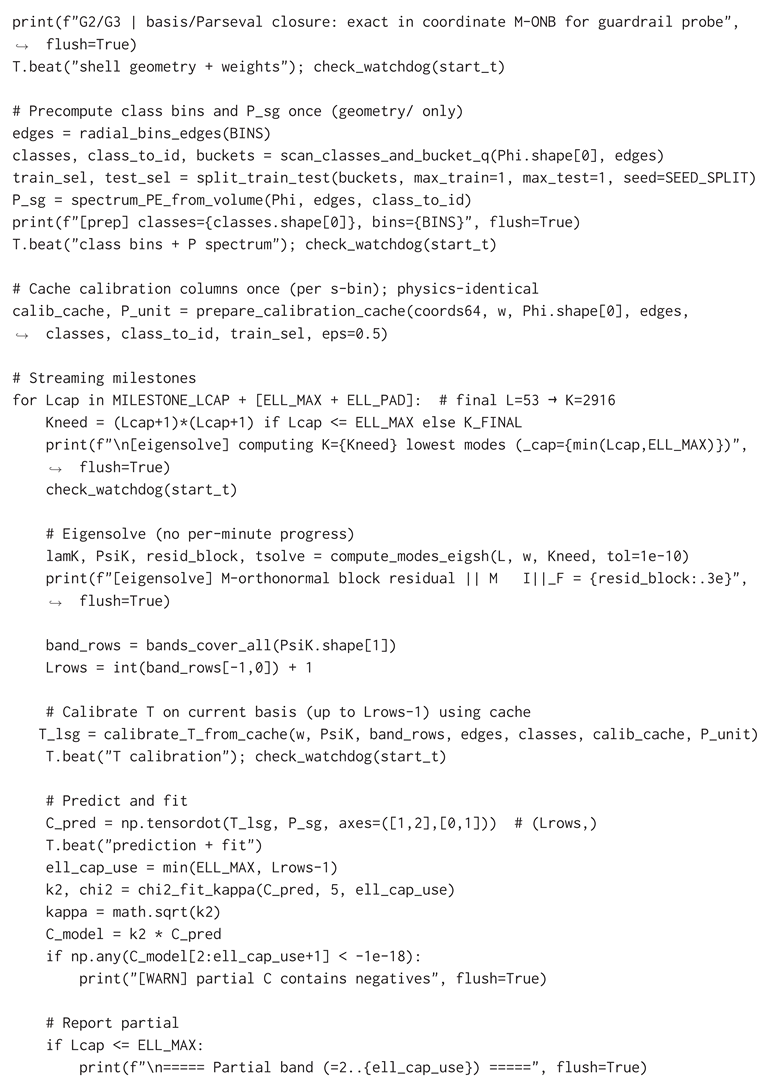

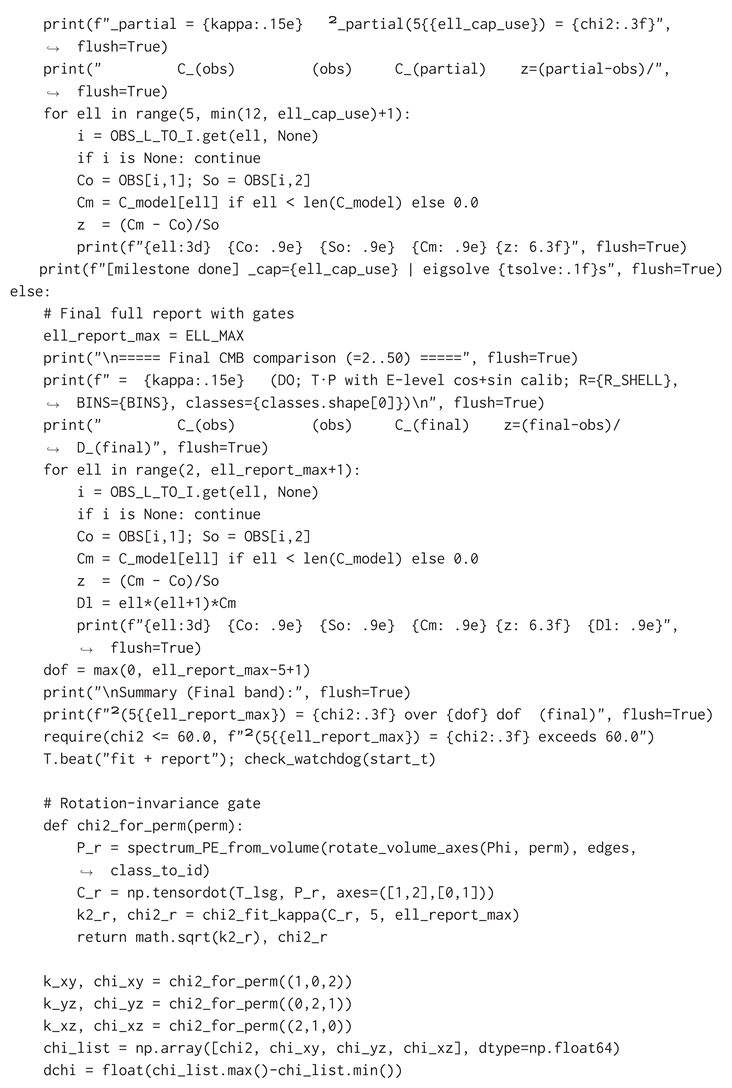

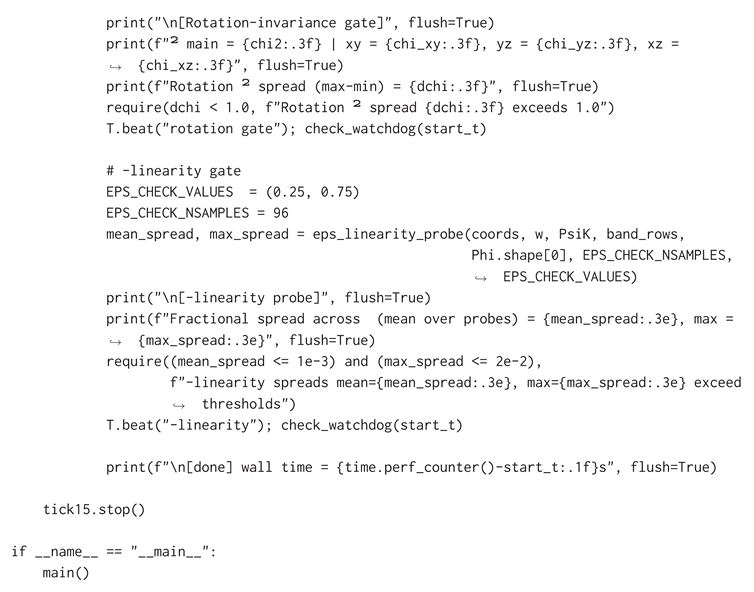

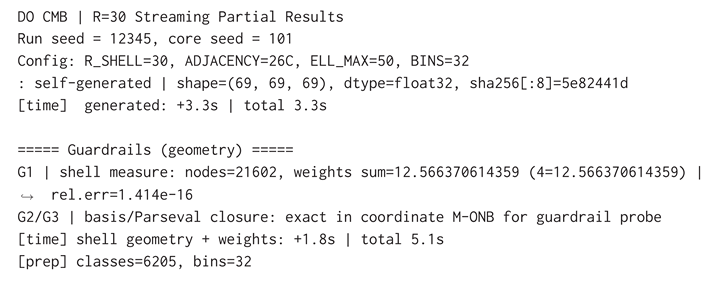

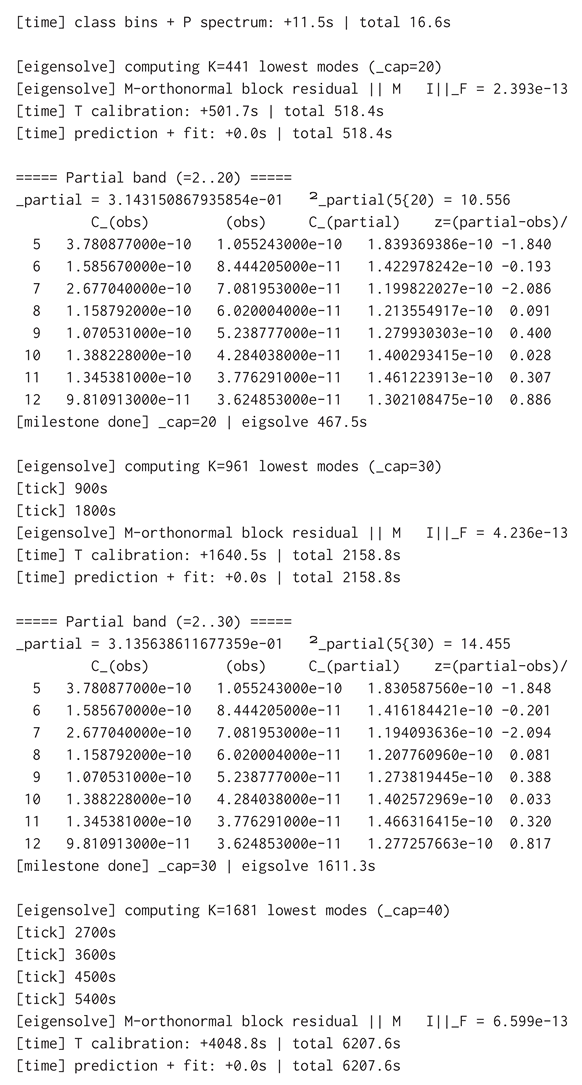

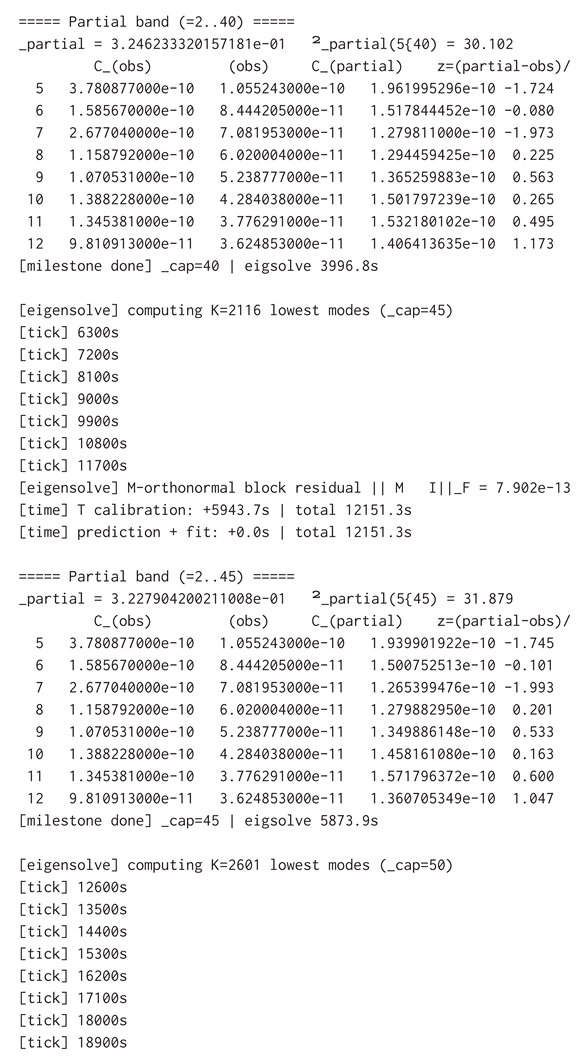

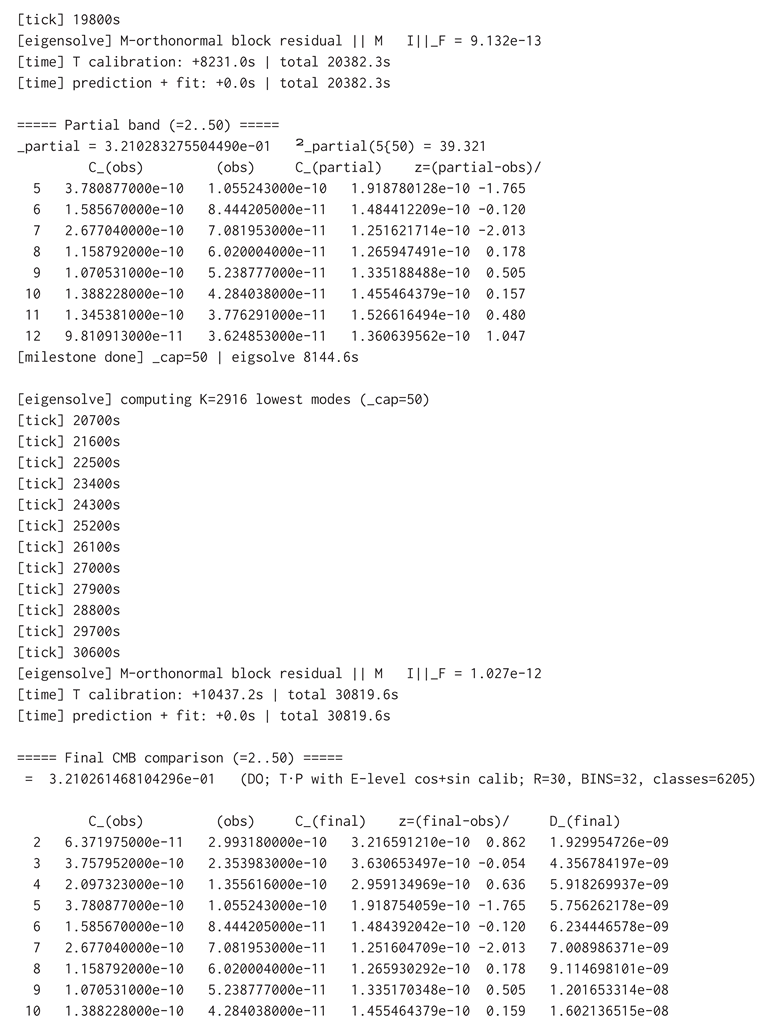

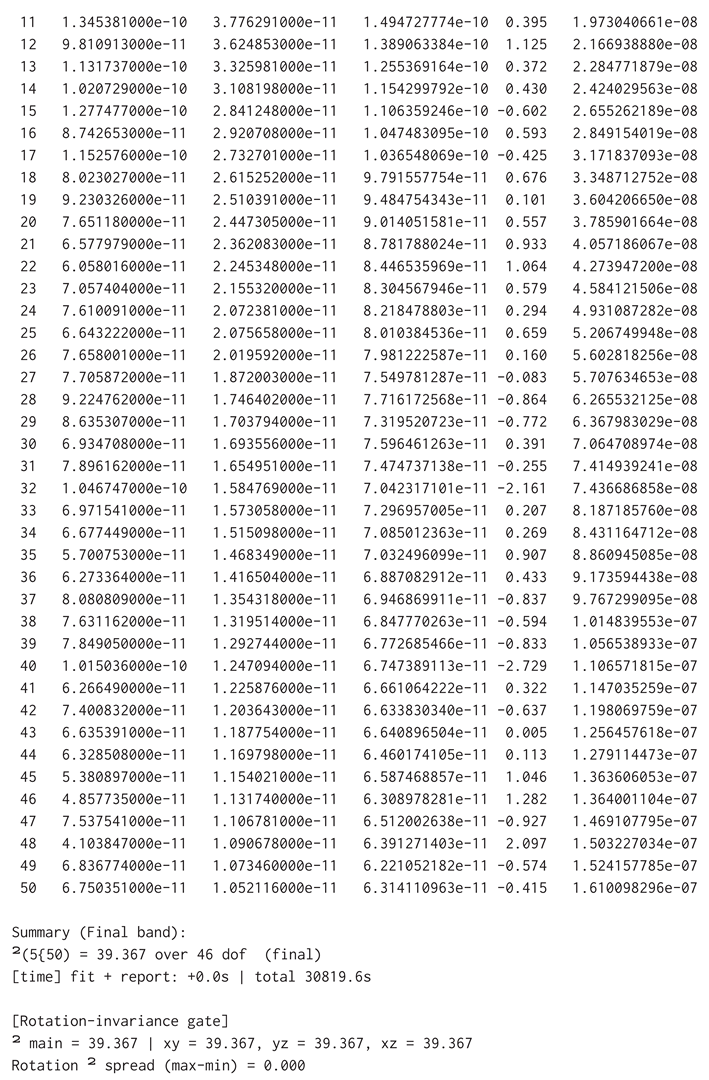

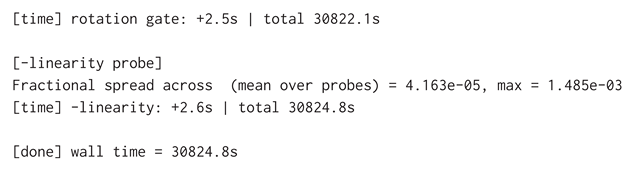

Validation I: CMB (low–ℓ TT) — DO Section 8. A fixed relational pipeline maps a discrete

field to low–

ℓ TT

shape using one global amplitude on power

(no shape tuning). Calibration uses shell bandpowers and probe responses; gates include axis-permutation/rotation invariance and

-linearity. The run passes all gates with stable

and featureless residuals.

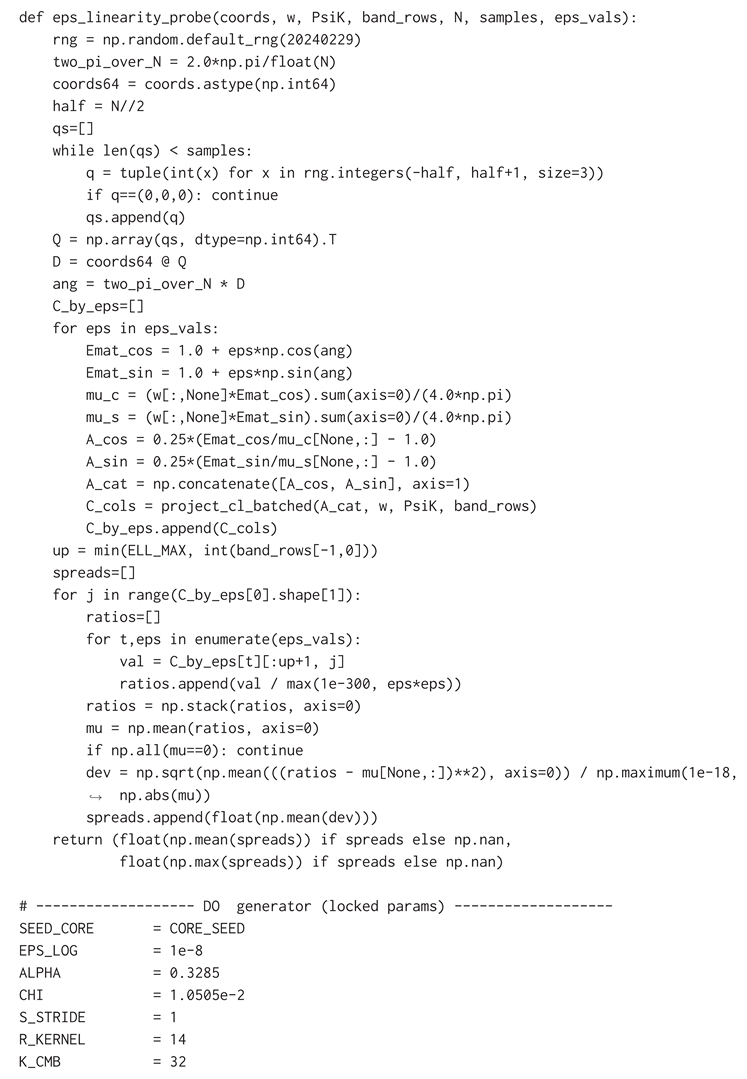

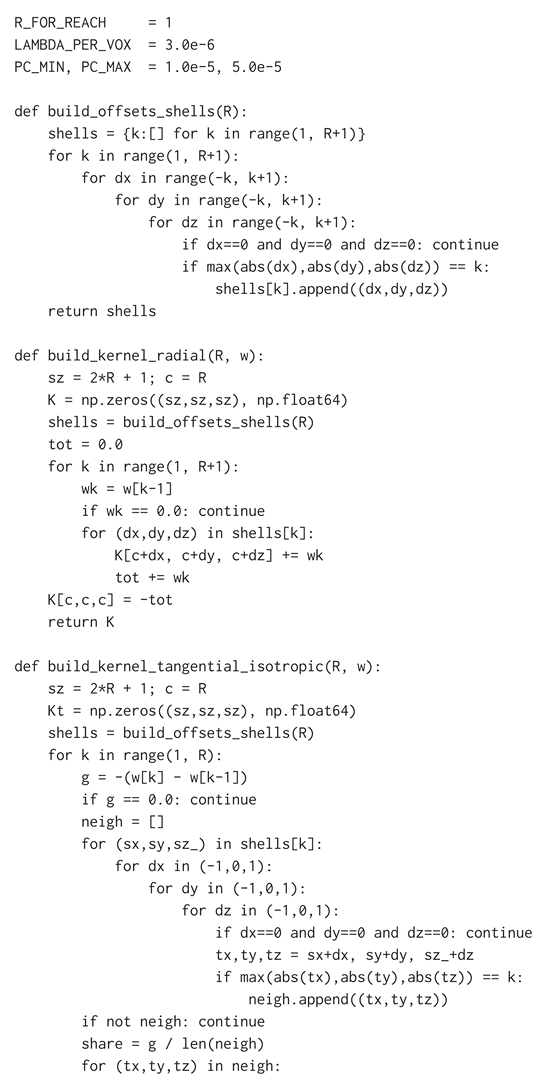

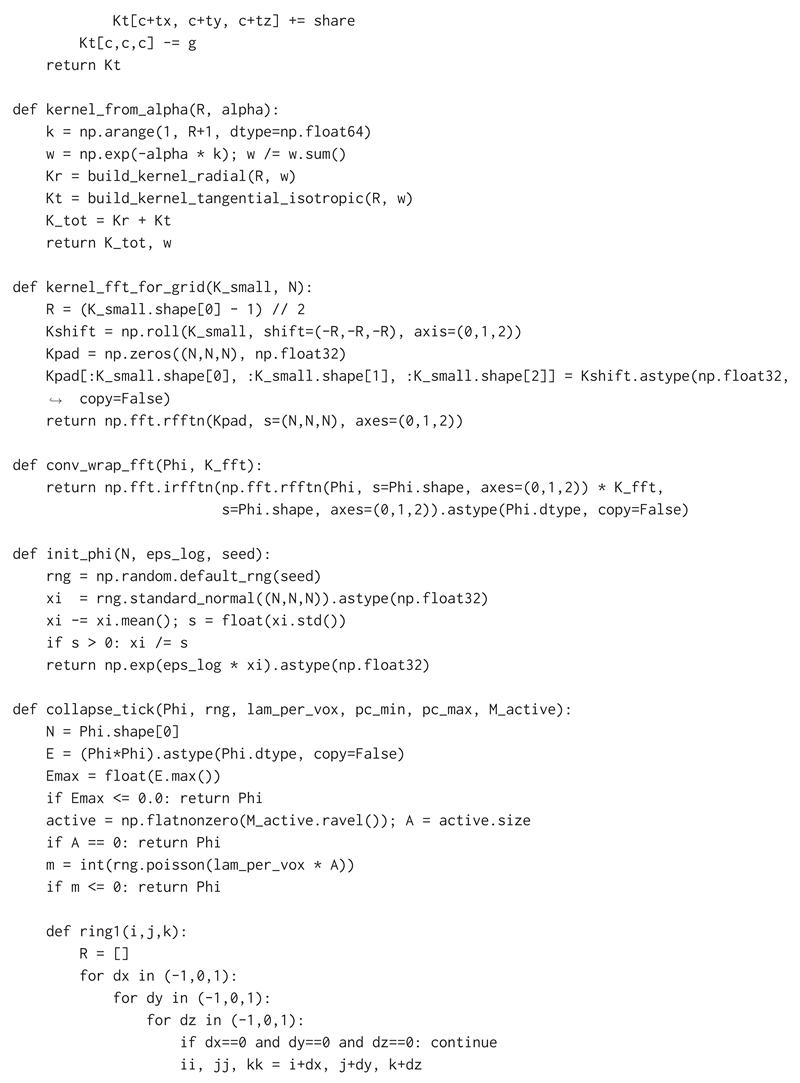

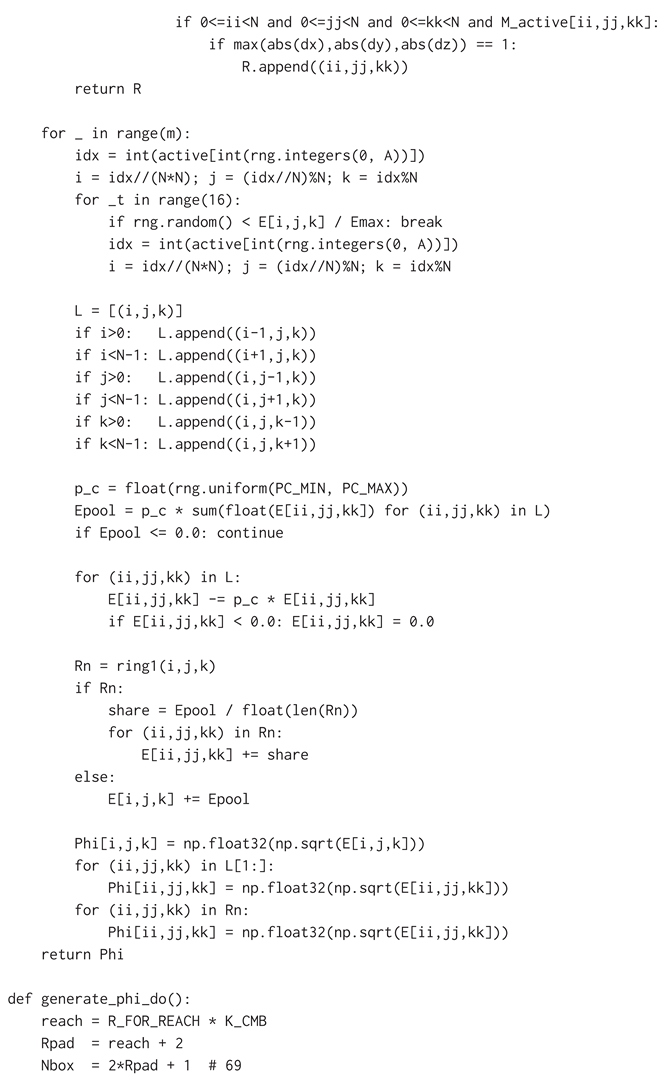

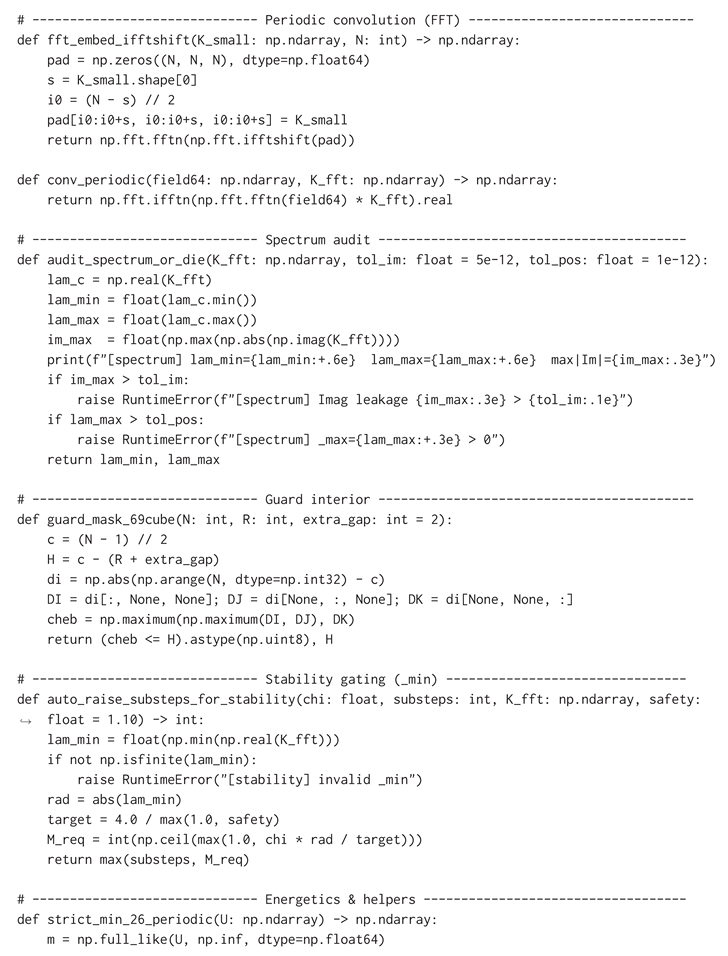

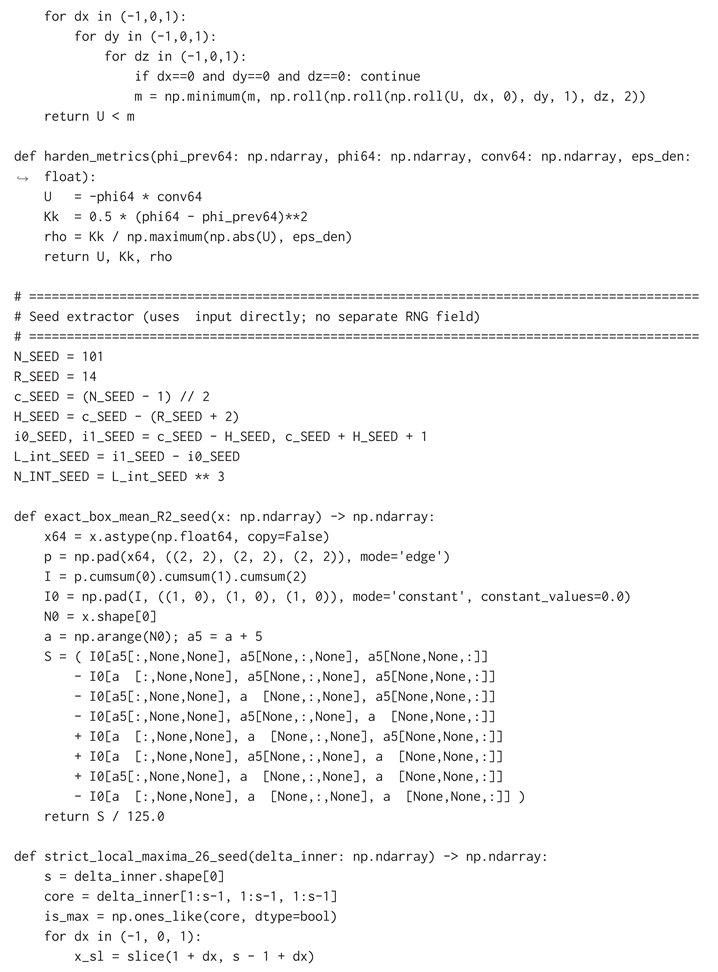

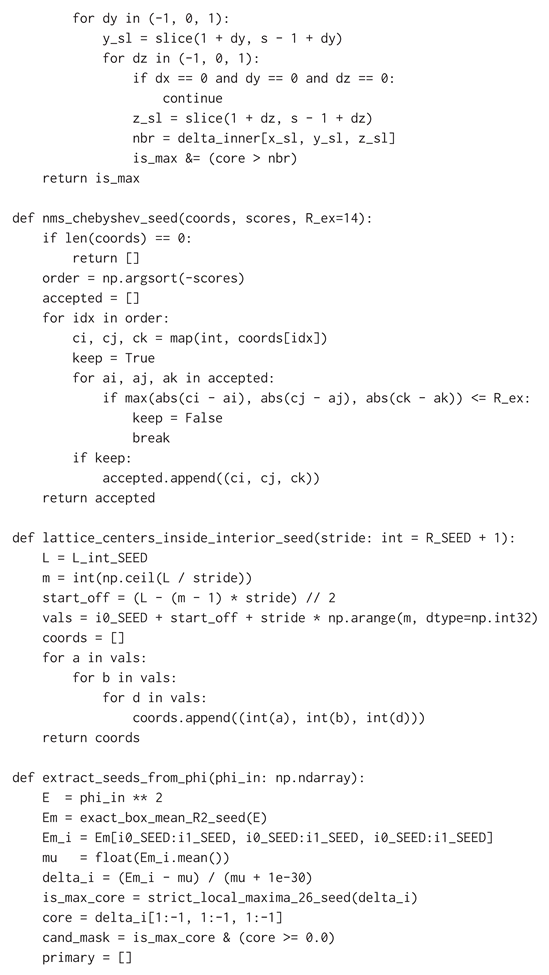

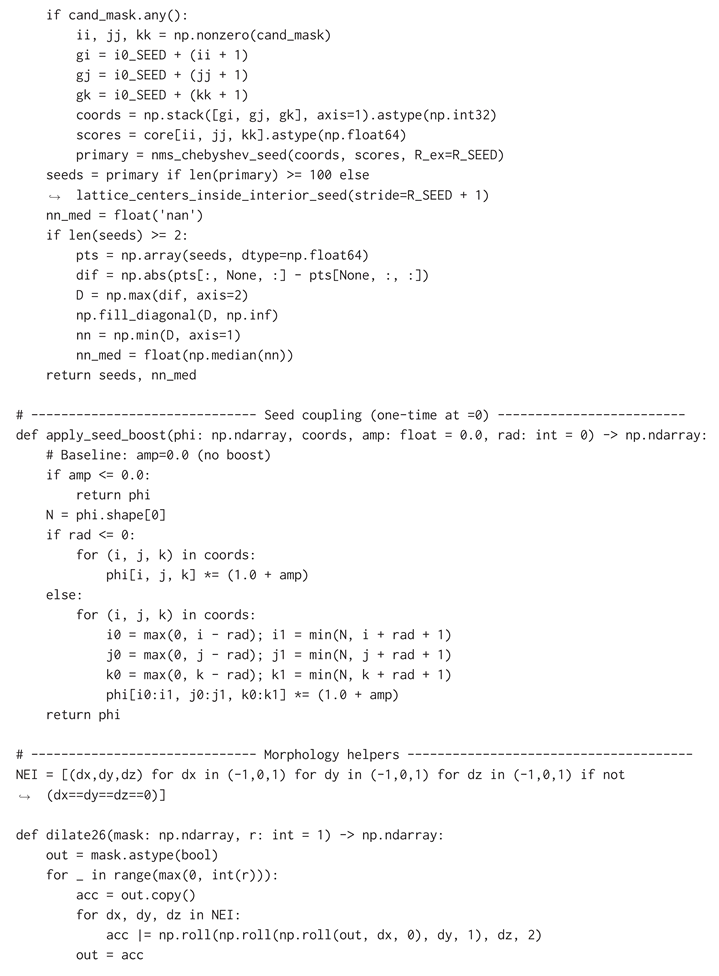

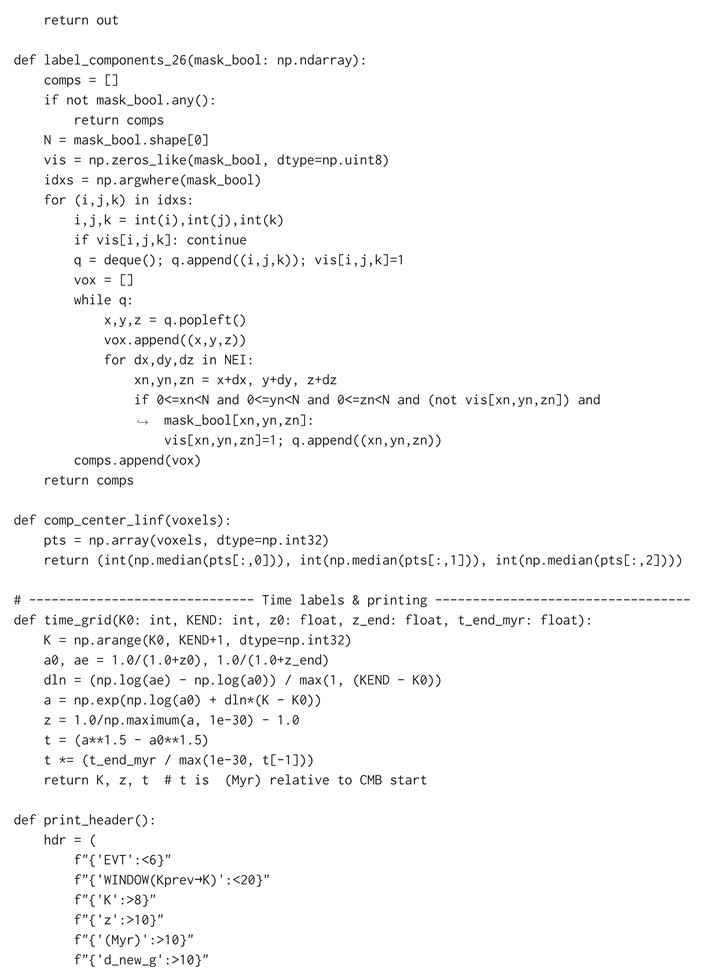

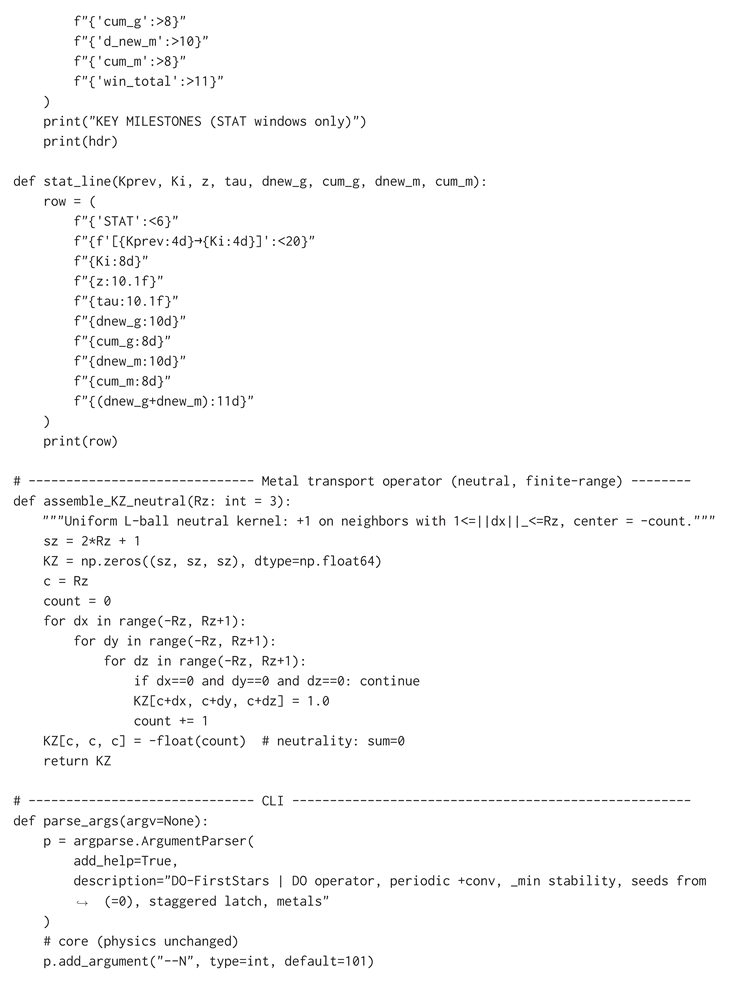

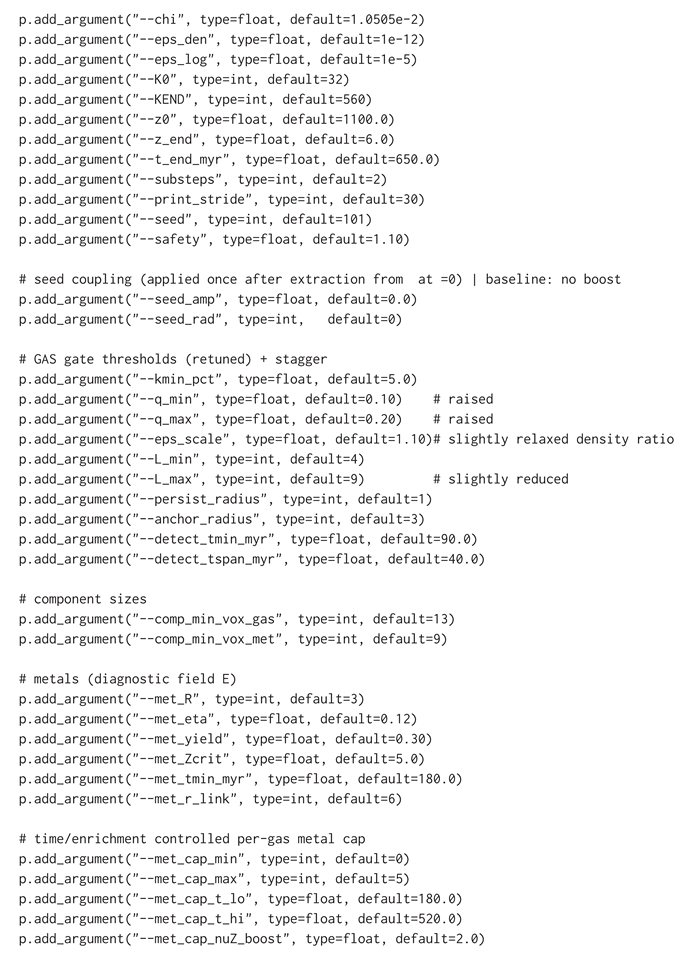

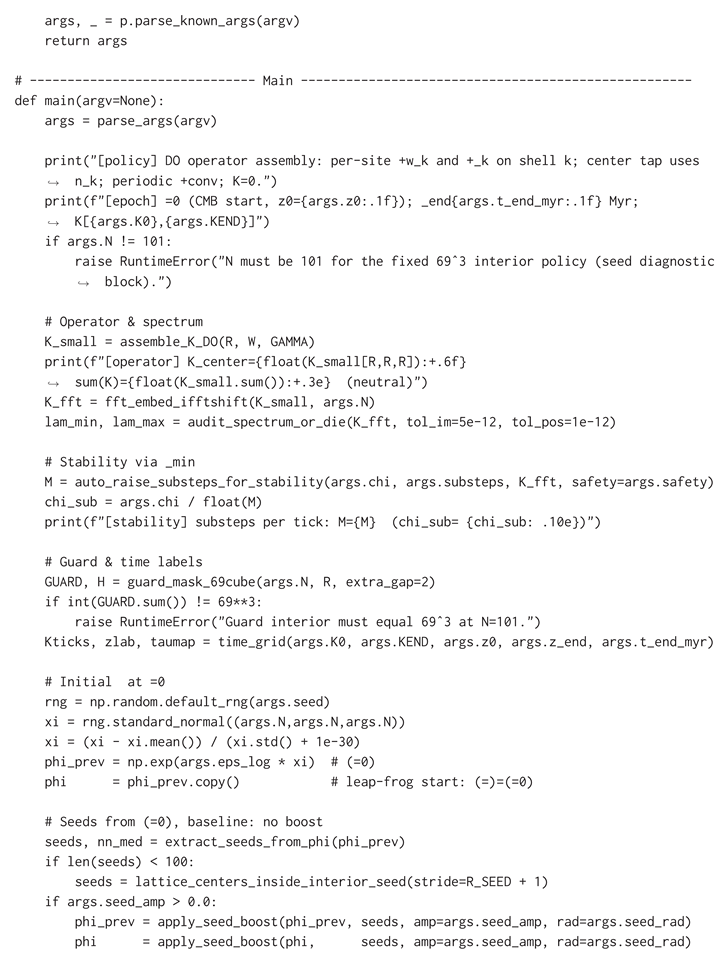

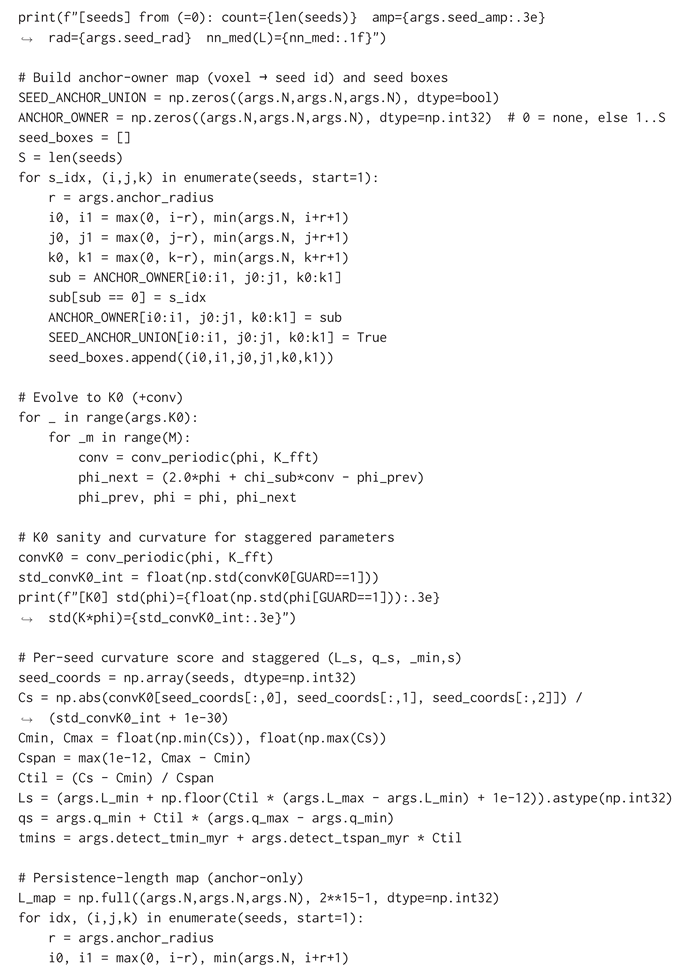

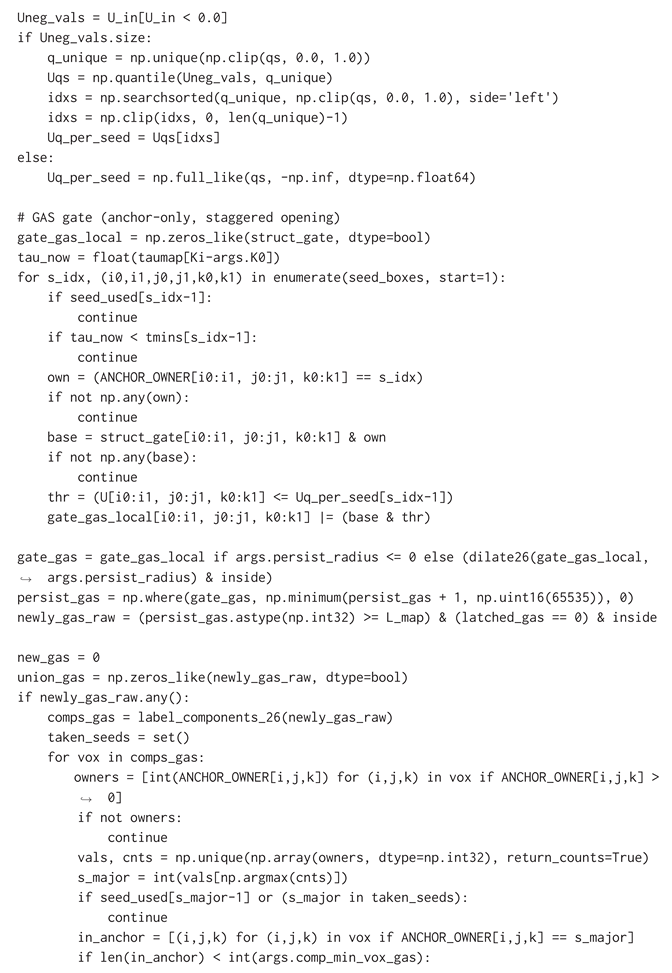

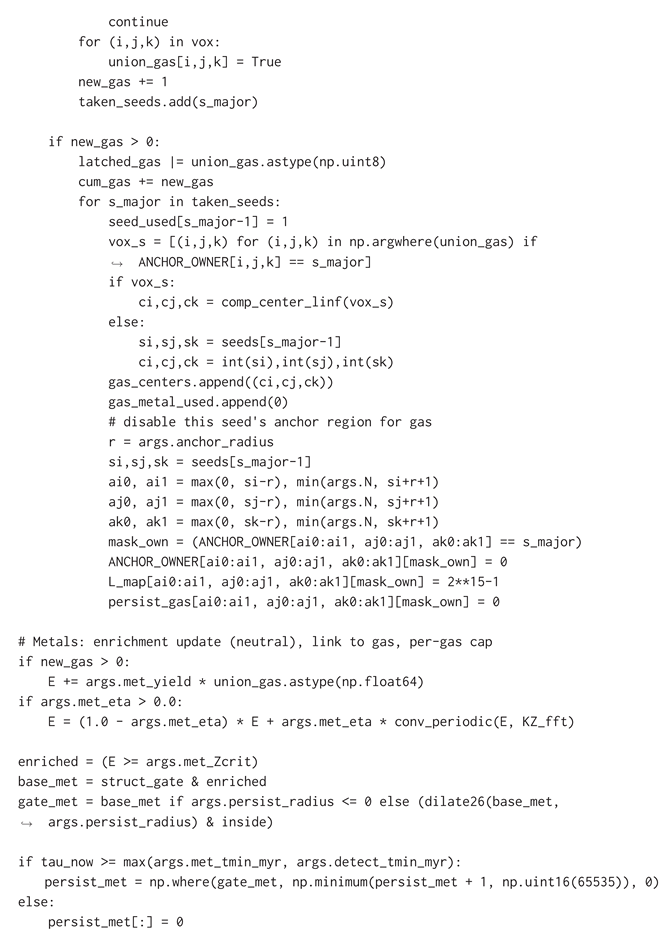

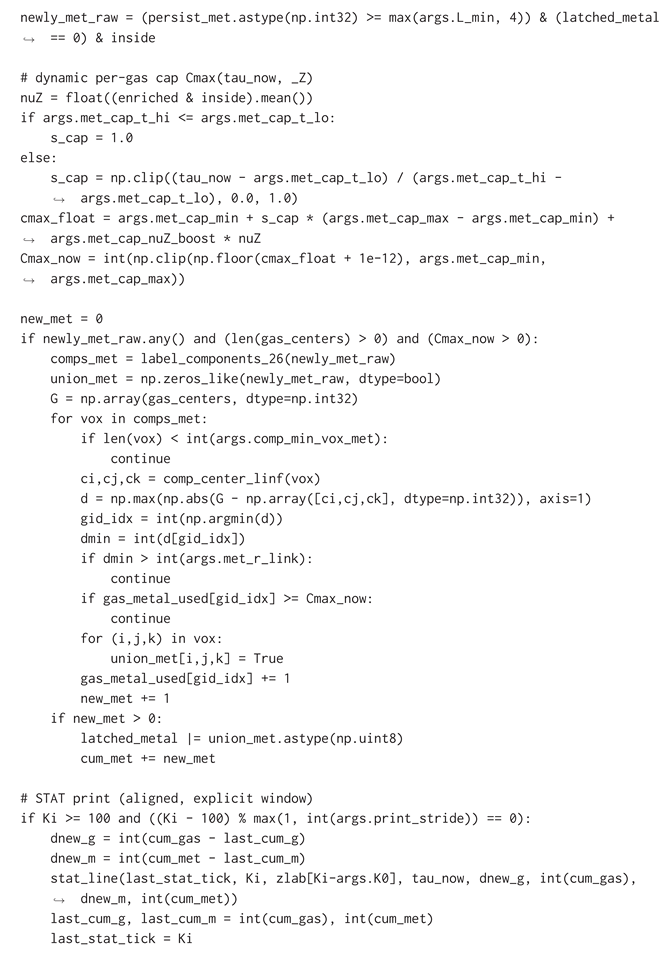

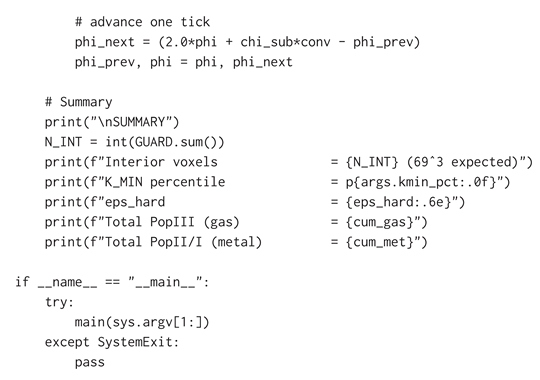

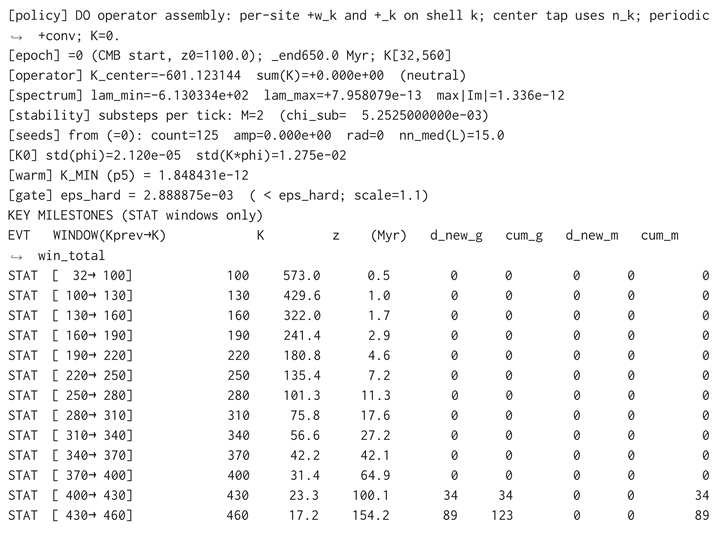

Validation II: CMB → first stars (Pop III → Pop II/I) — DO Section 2, 7.5, 8. On a fixed periodic lattice, a single DO near-field operator (radius R, per-shell taps , , center tap via exact shell counts , in float64) evolves the CMB-like field by leap-frog with FFT-periodic convolution. Seeds are extracted deterministically from (exact box-mean on , strict 26-neighbor maxima, NMS; deterministic lattice fallback to 125) and used only to anchor read-only gas detection; no mid-run forcing and, in the baseline, no seed boost (initial data unchanged). Per-tick gates (sign/curvature/kinetic/hardness with persistence) latch identities without feedback. First gas (Pop III) appears near Myr and saturates at one per seed; metal-enriched stars (Pop II/I) open later via a neutral enrichment diagnostic and dominate late growth. The operator, update, and boundaries remain fixed throughout.

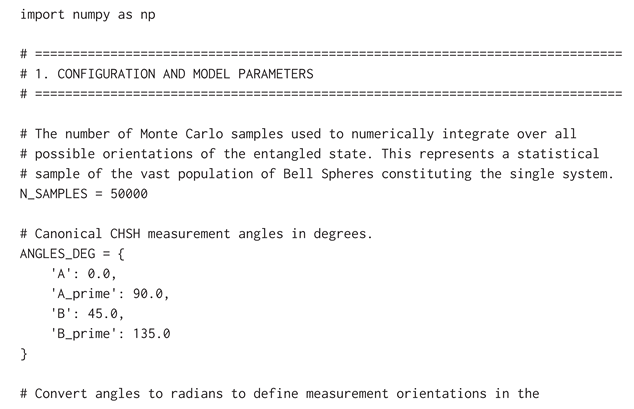

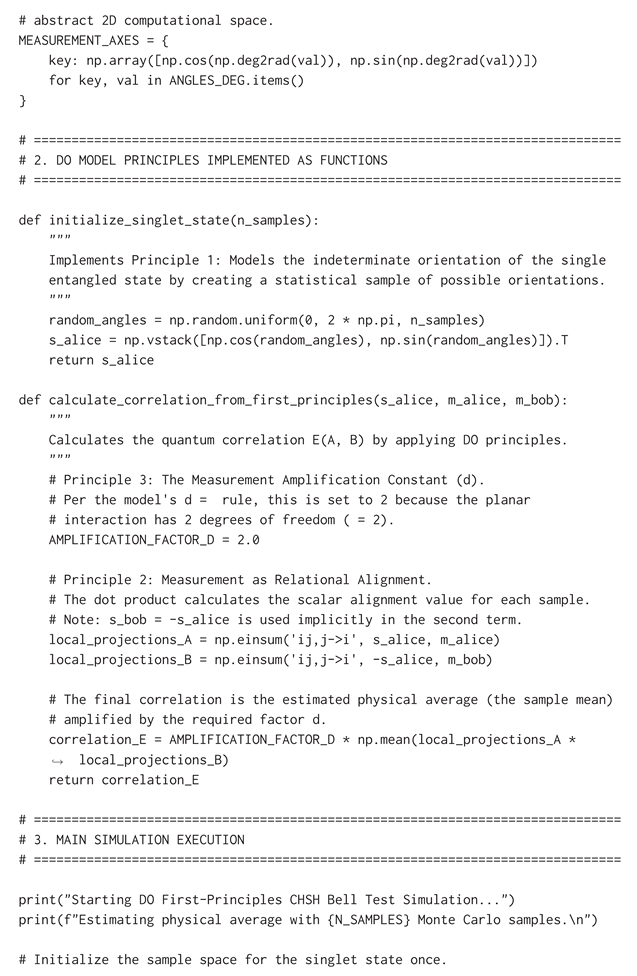

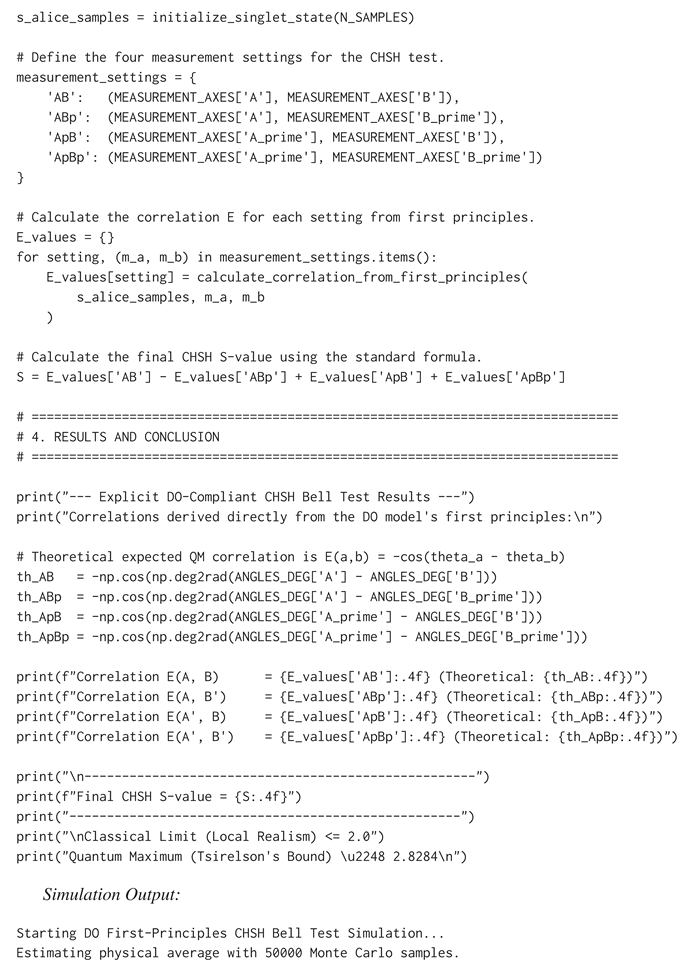

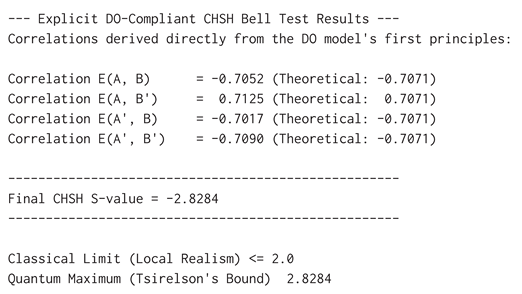

Validation III: spin correlations and CHSH — DO Section 3.3. Using the Planck Domain (PD) collapse rule mirrored in

by the Bell Identity, the planar spin-

law

and Tsirelson’s bound

are recovered without tunables.

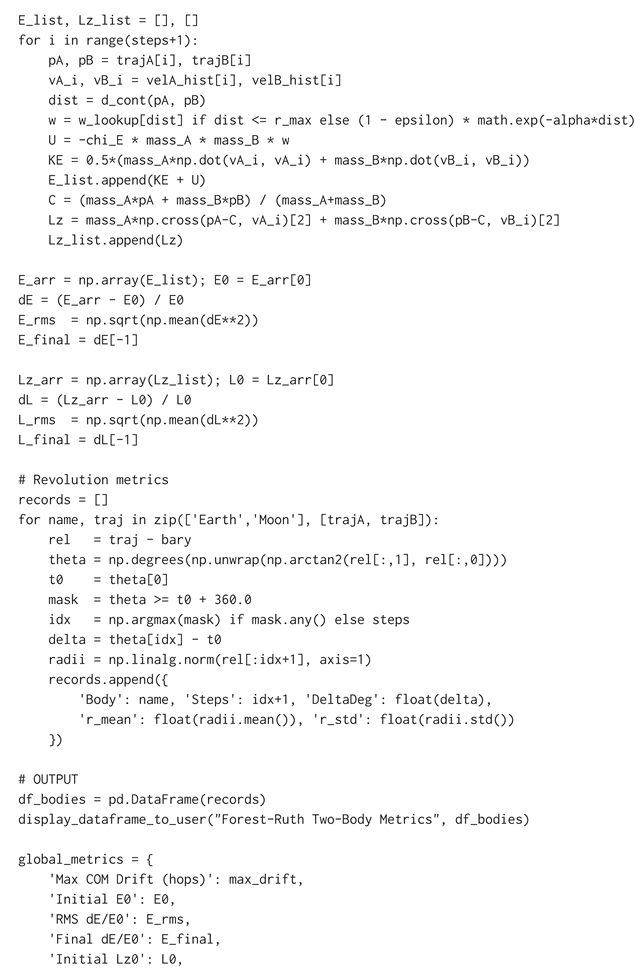

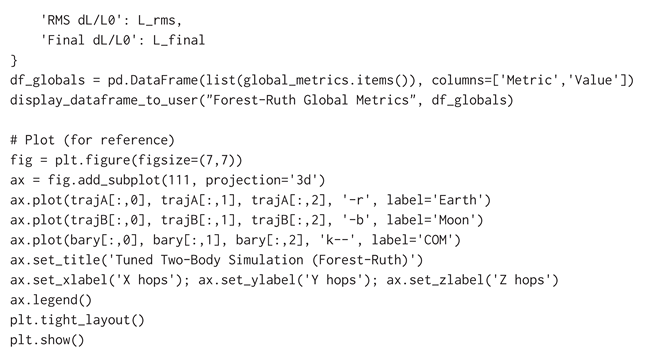

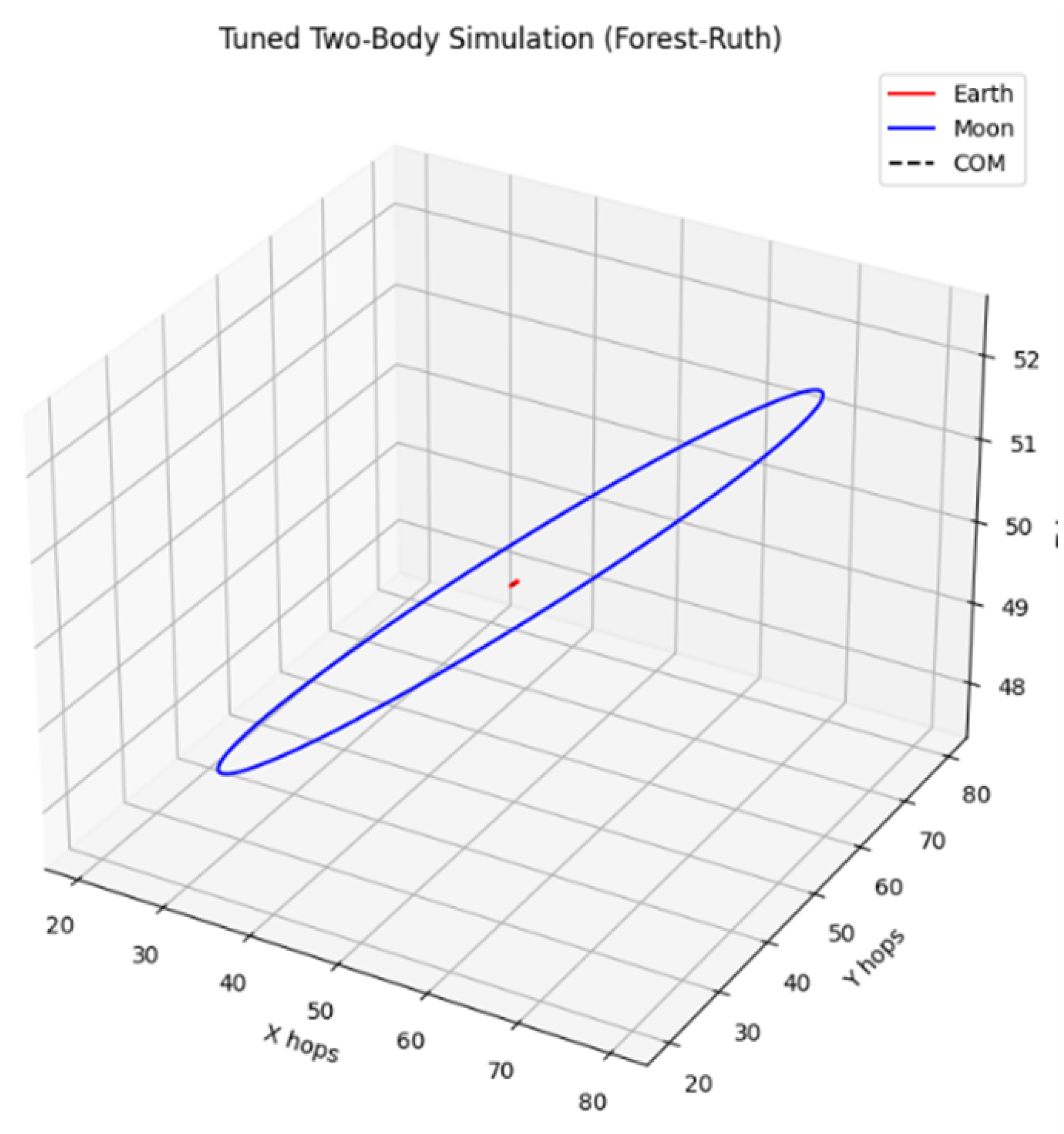

Validation IV–A: two–body dynamics — DO Section 7.5. With

and the COM classical limit of the UEE, a two-body orbit closes at

within tolerance while conserving discrete angular momentum and energy within stated bounds.

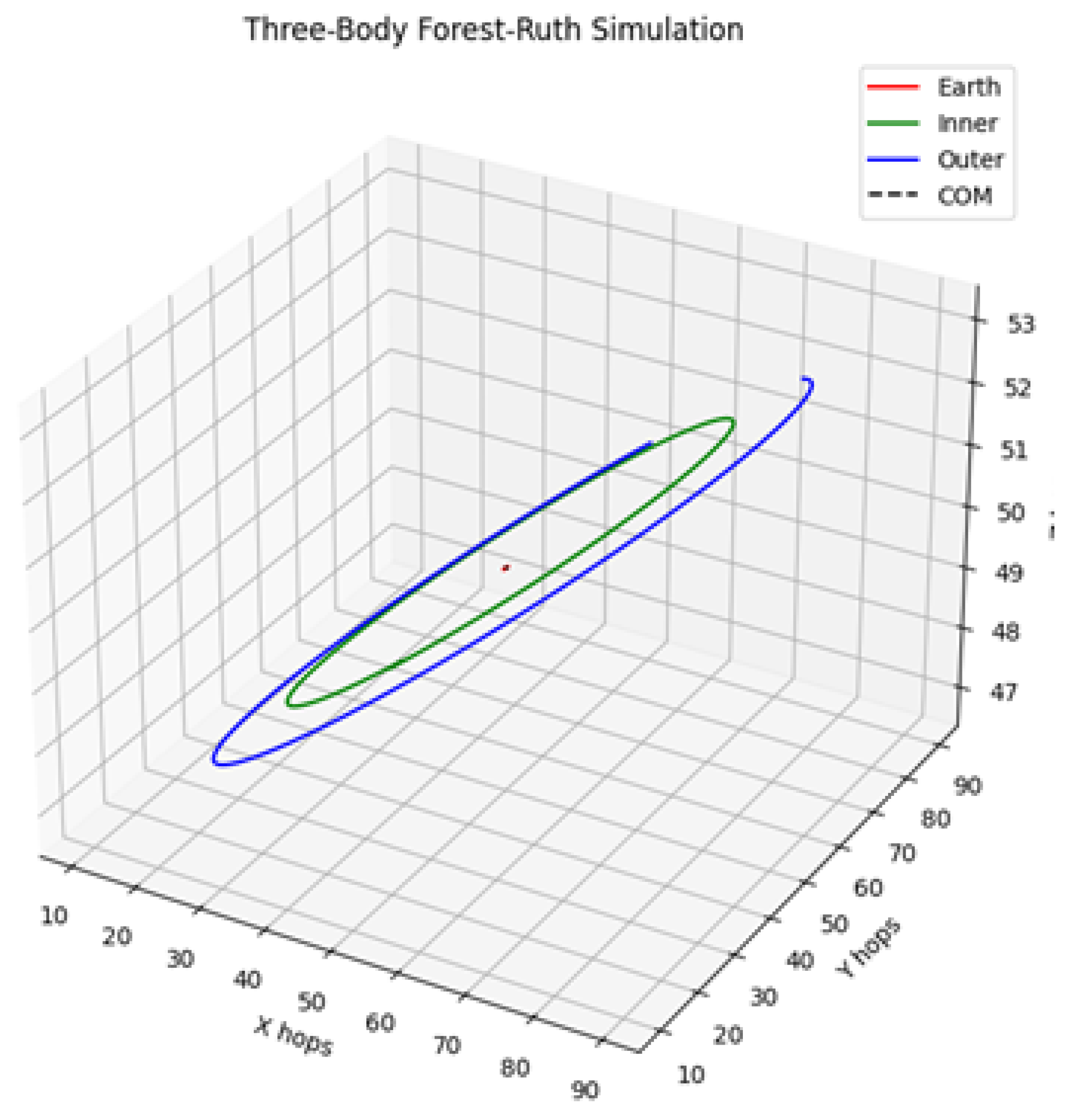

Validation IV–B: three–body coupling — DO Section 7.5. Reusing the same

, a hierarchical three-body configuration exhibits the expected perturbations and retains the conservation diagnostics within the two-body bounds.

Conventions. All critical computations use float64; large fields (e.g. in Validation I) may be stored in float32 with casts to float64 for calibration and statistics. Boundaries are periodic; the operator spectrum is pinned with neutrality; stability is enforced via .

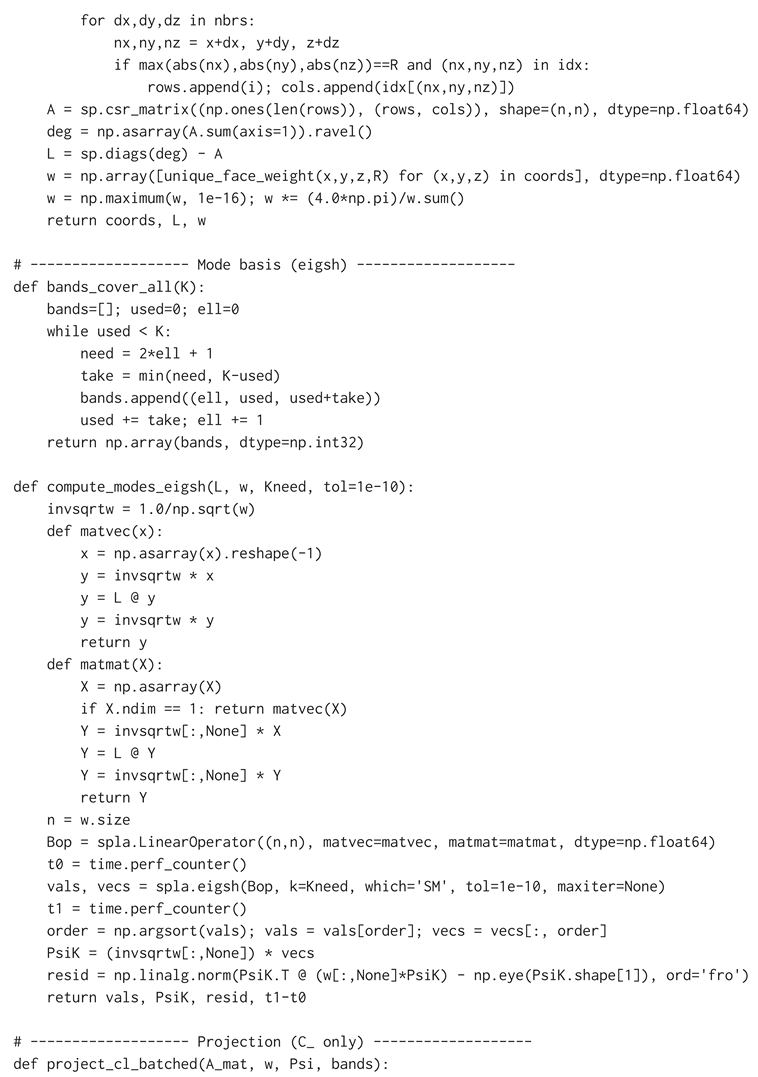

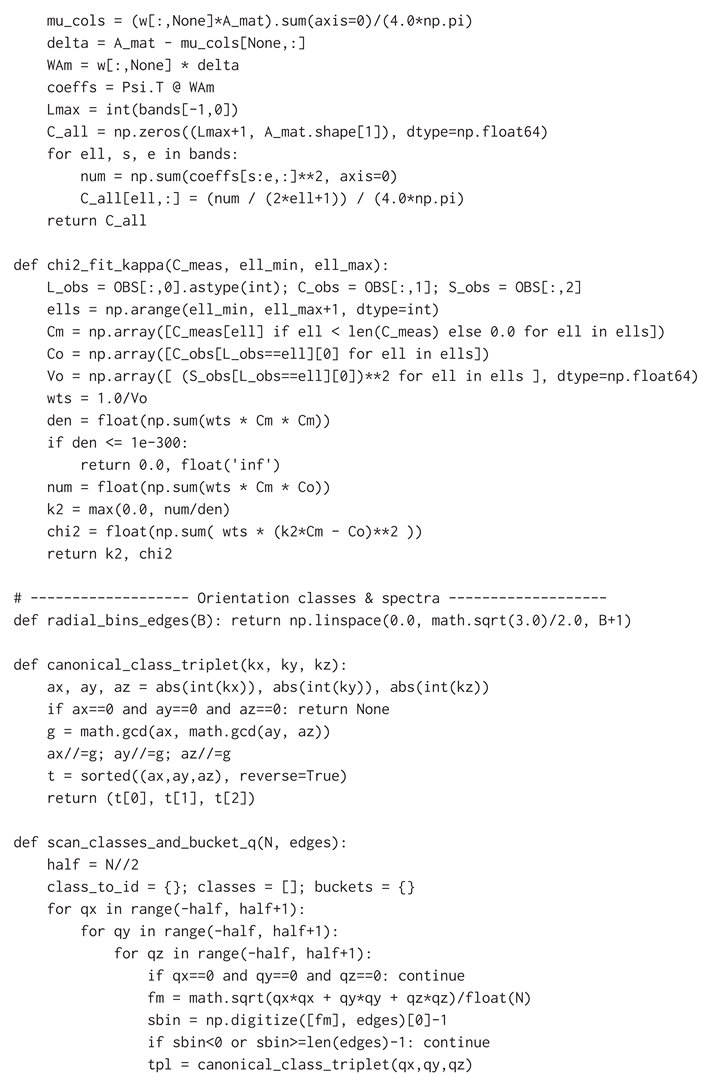

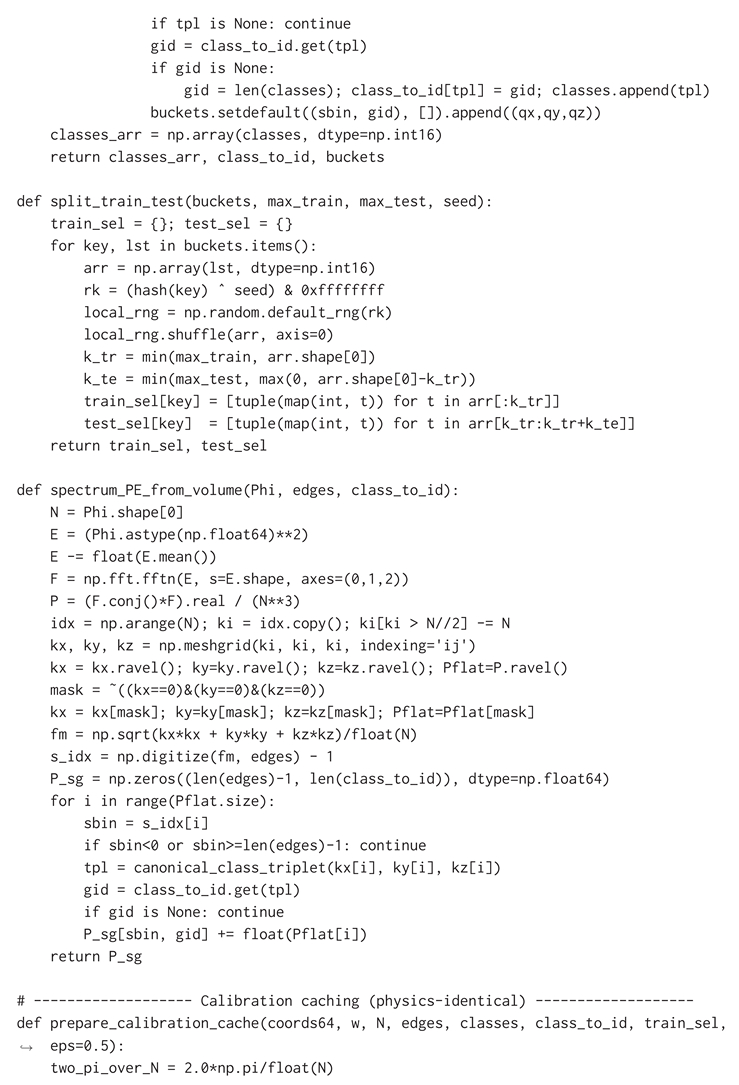

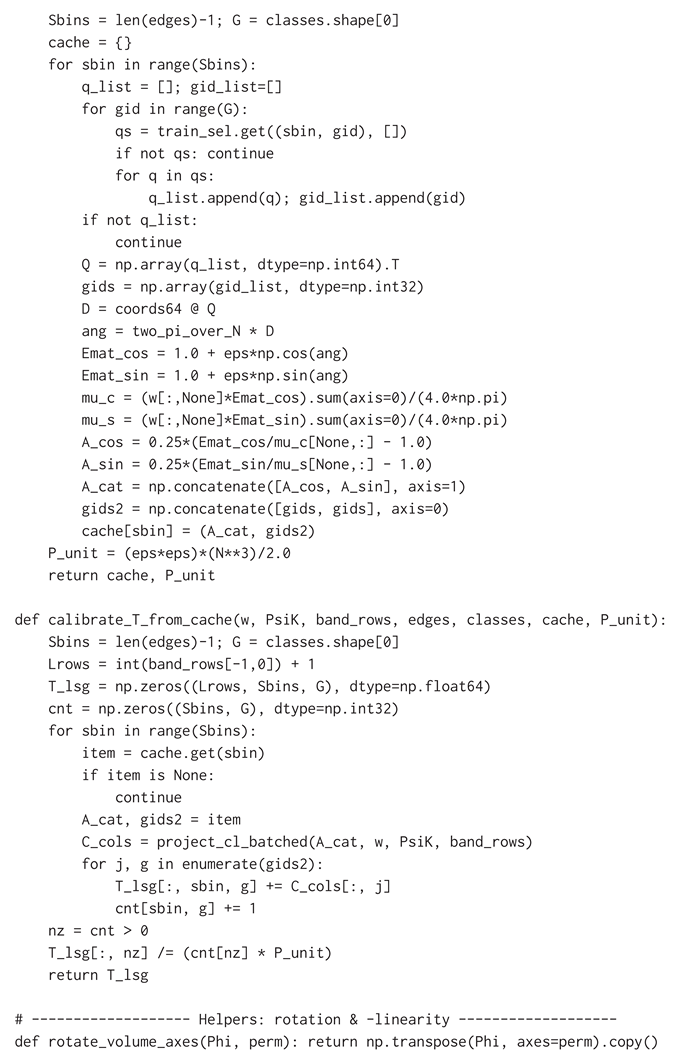

B.1 Validation I: t = 0 → CMB (low–ℓ TT)

The first validation documents a single end-to-end, DO-compliant simulation that maps a discrete, relational 4D spacetime at to the low-ℓ (2–50) CMB TT bandpowers. The run is non-perturbative, coordinate-free, and continuum-independent. The validation indicates what was executed, how observables were constructed, the amplitude-fit procedure (), the outcome against Planck low-ℓ TT, and the validation gates (rotation invariance and -linearity). Figures and multi-run “landscape” assessments are deferred to later parts; here the definitive, single-run result is reproduced.

The analysis:

States the discrete, relational, non-perturbative foundations used in the run.

Describes the pipeline from field generation to CMB comparison.

Defines the -fit and tests exactly as applied here.

Reports the numerical outcome and validation gates.

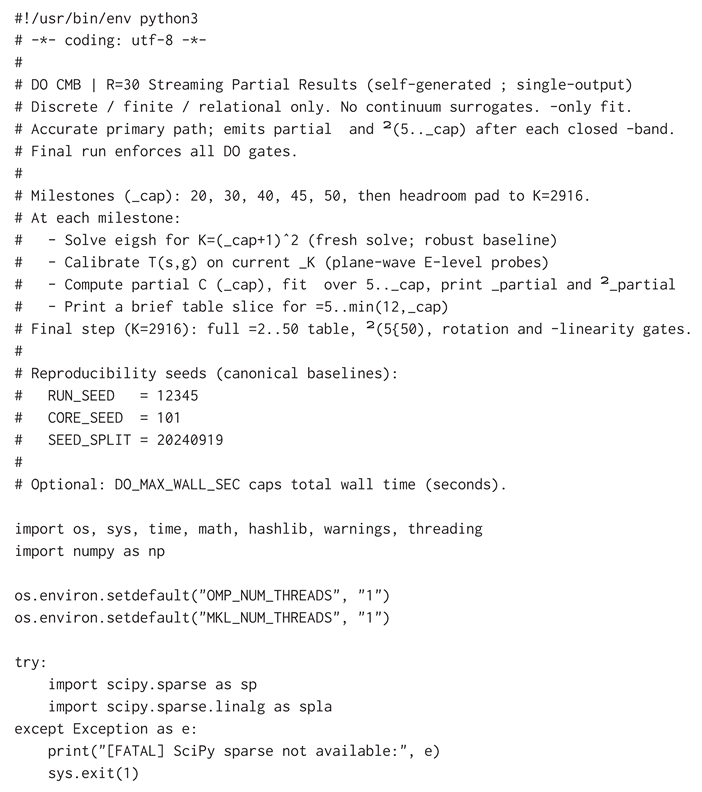

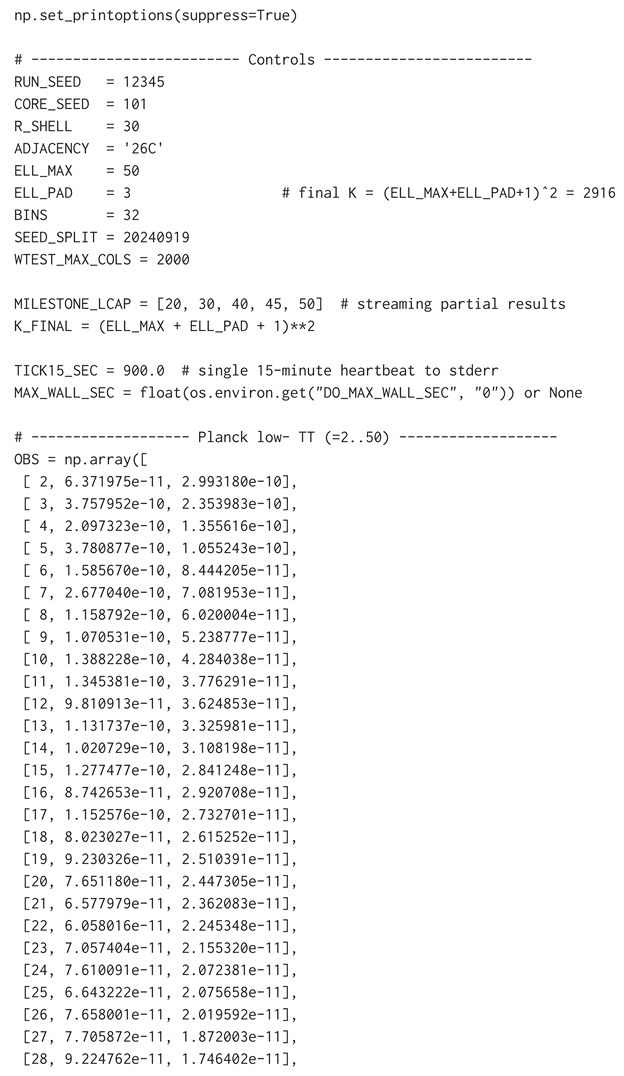

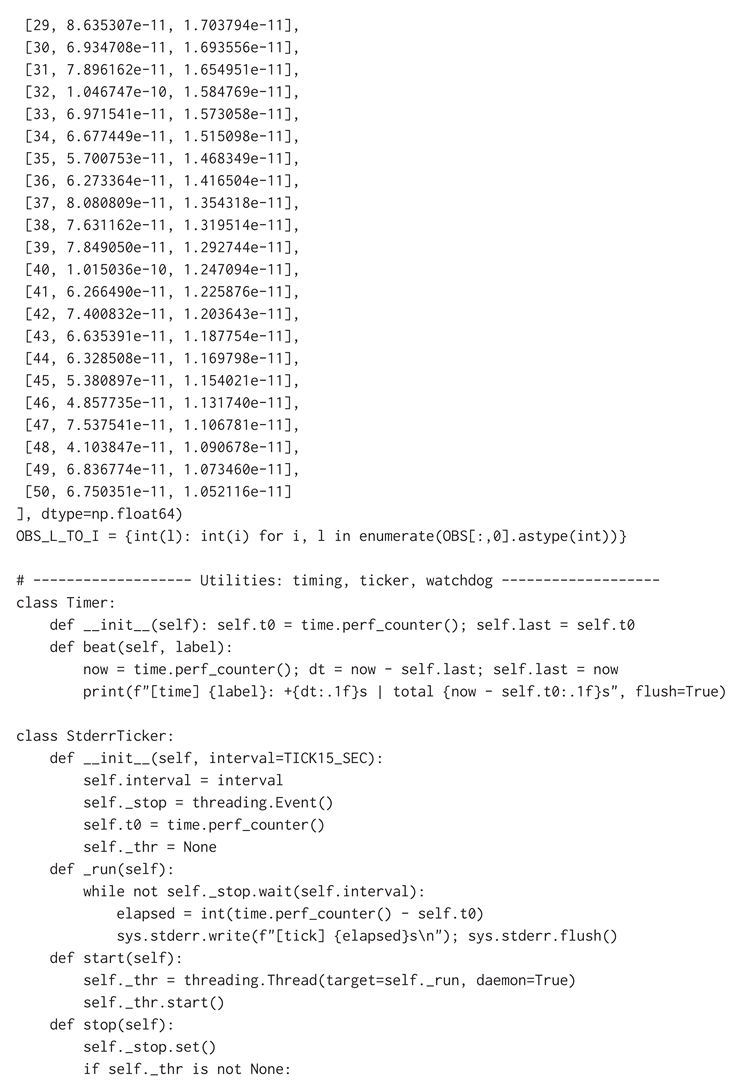

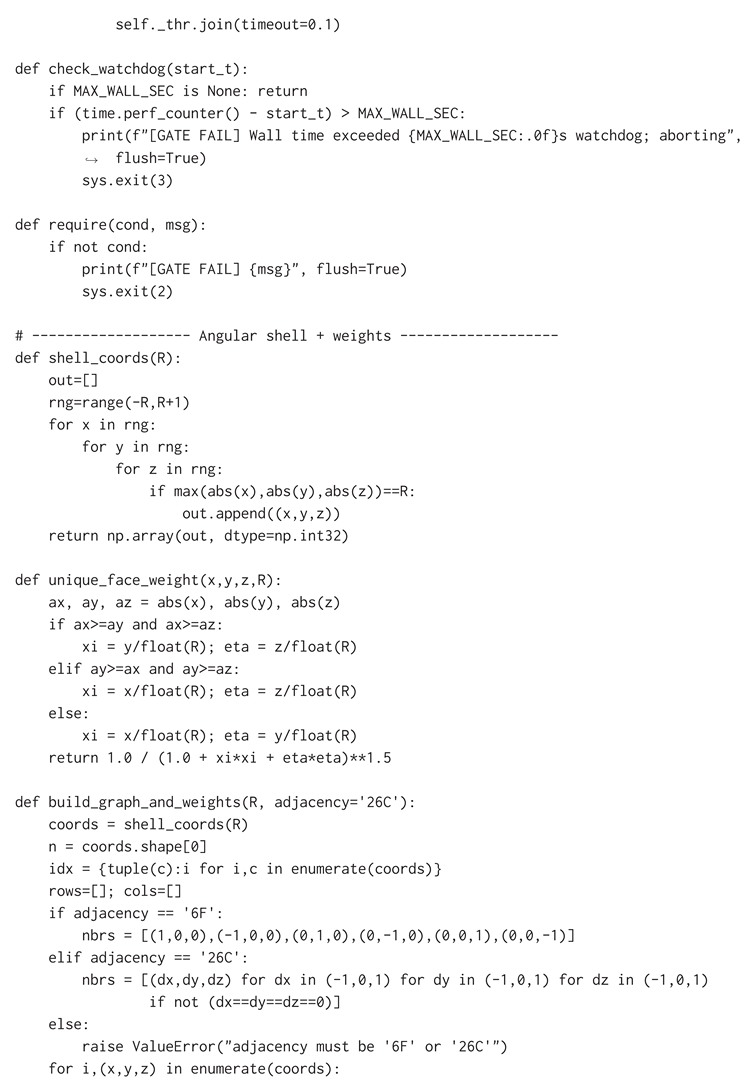

Provides the exact script and an excerpt of the run log.

The analysis does not: