Submitted:

30 May 2024

Posted:

30 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fruit Sampling

2.2. Evaluation of the Main Agronomic Characteristics

2.3. Determination of Capsaicinoid Content

2.4. Determination of Carotenoid Content

2.5. Determination of Tocopherol Content

2.6. Determination of Total Vitamin C Content

2.7. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

2.8. Measurement of the Radical Scavenging Activity

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Agronomic and Physico-Chemical Traits

3.2. Functional Quality Traits

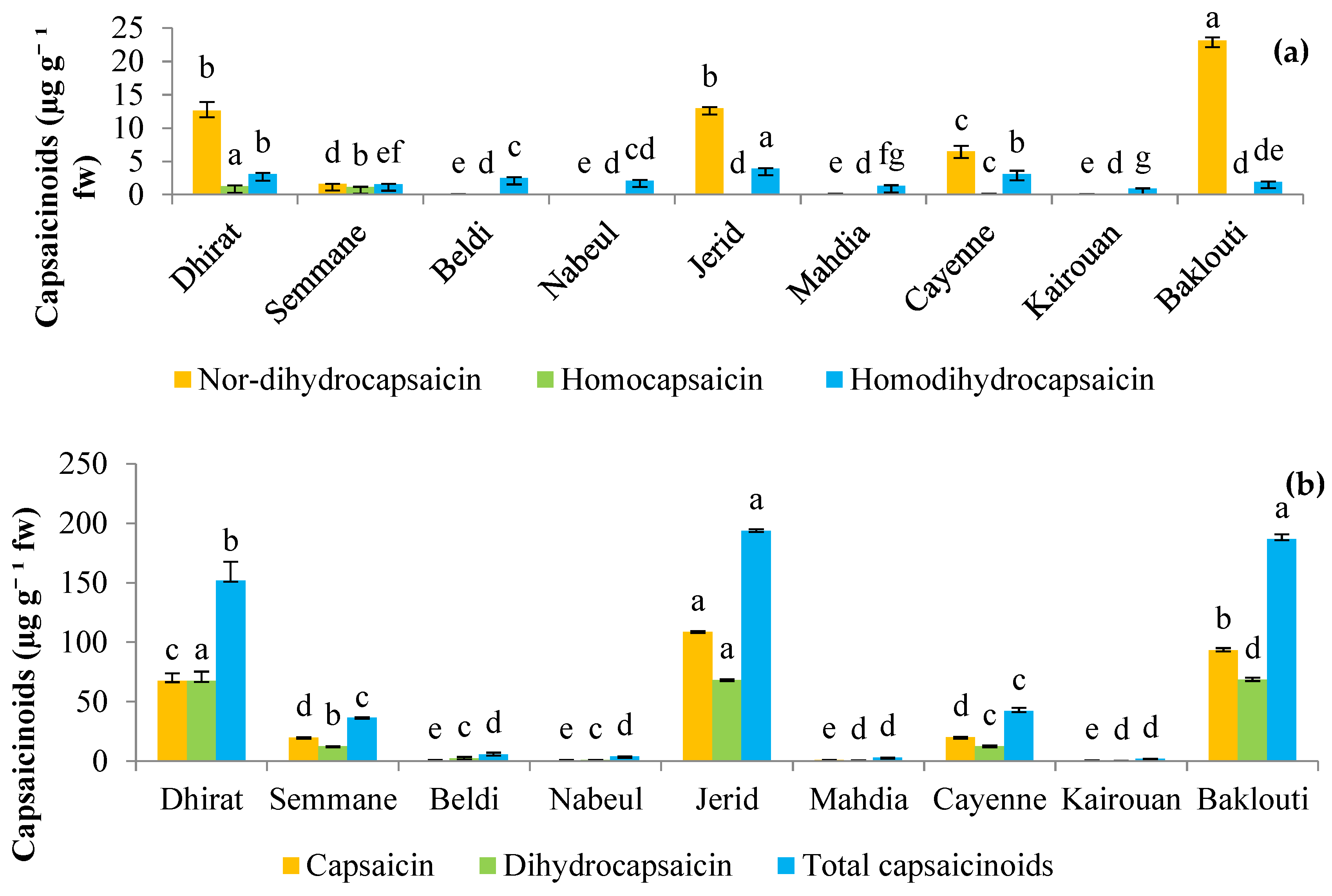

3.2.1. Capsaicinoid Content

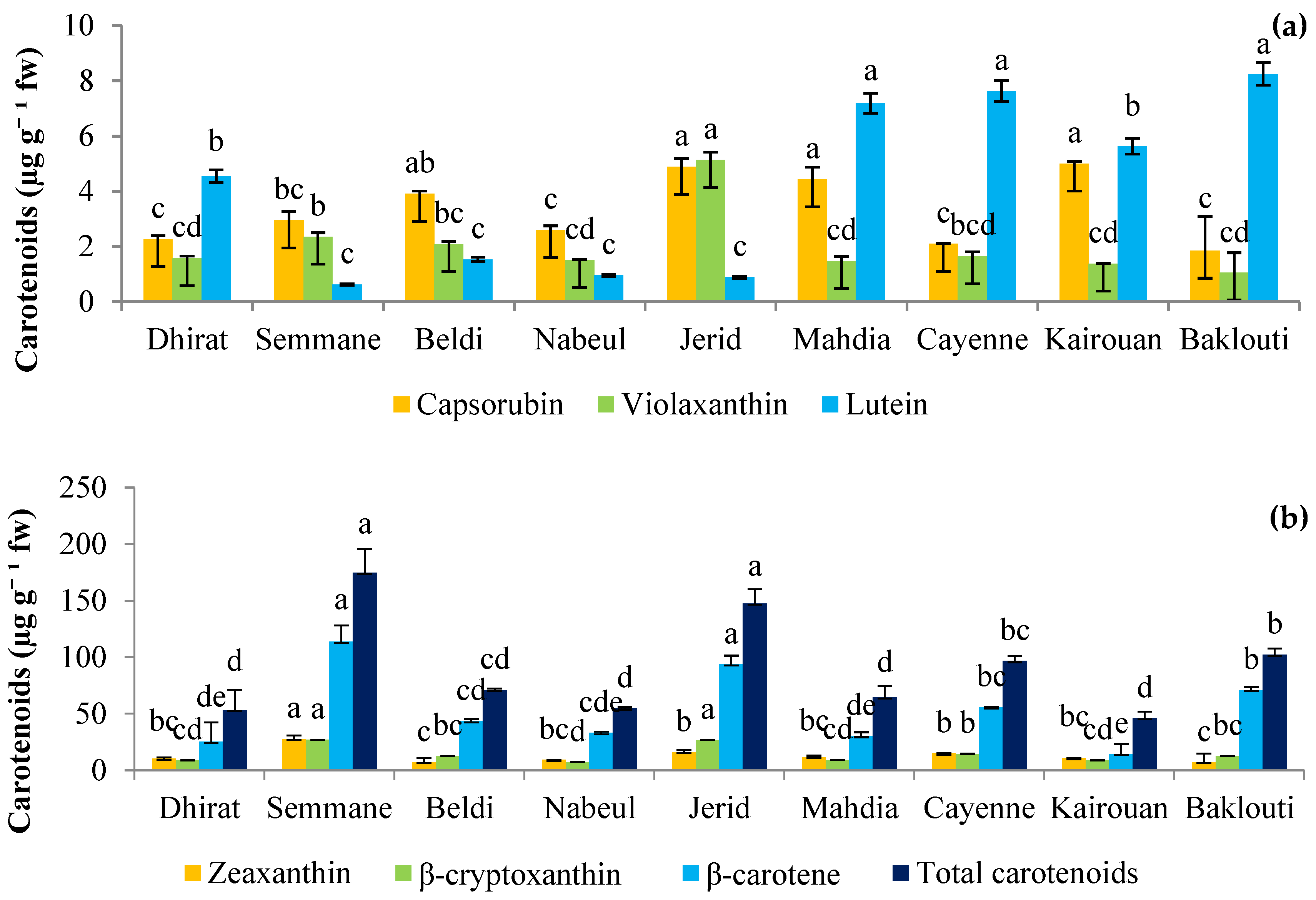

3.2.2. Carotenoid Content

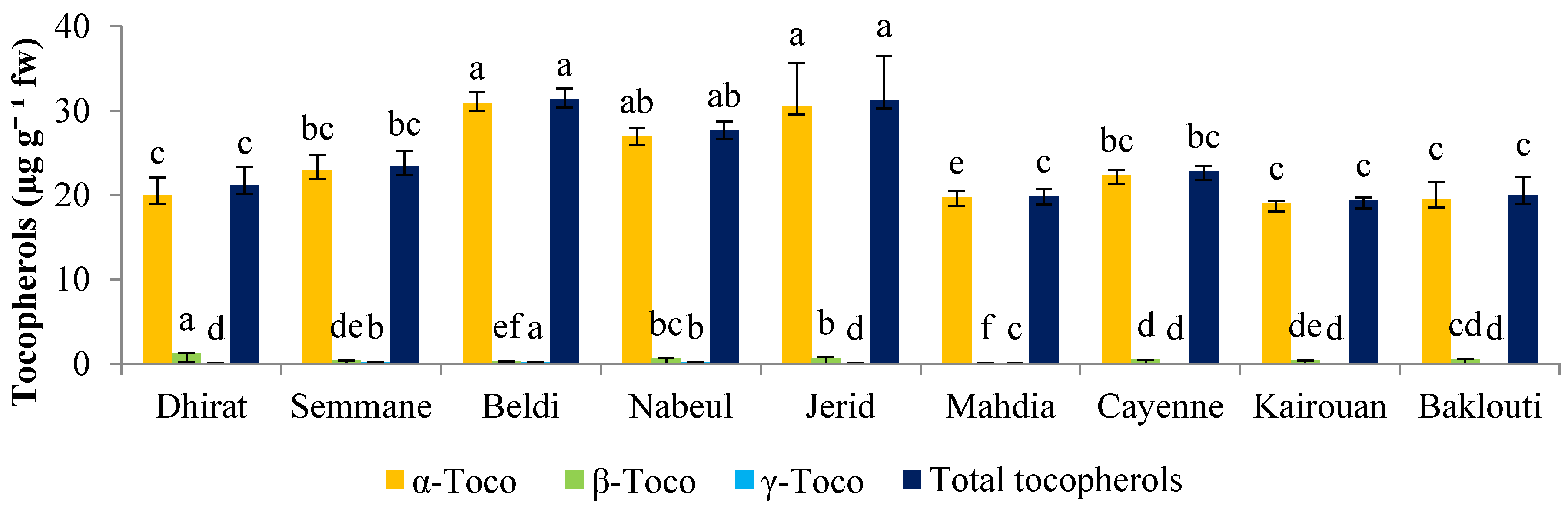

3.2.3. Tocopherol Content

3.2.4. Total Vitamin C Content

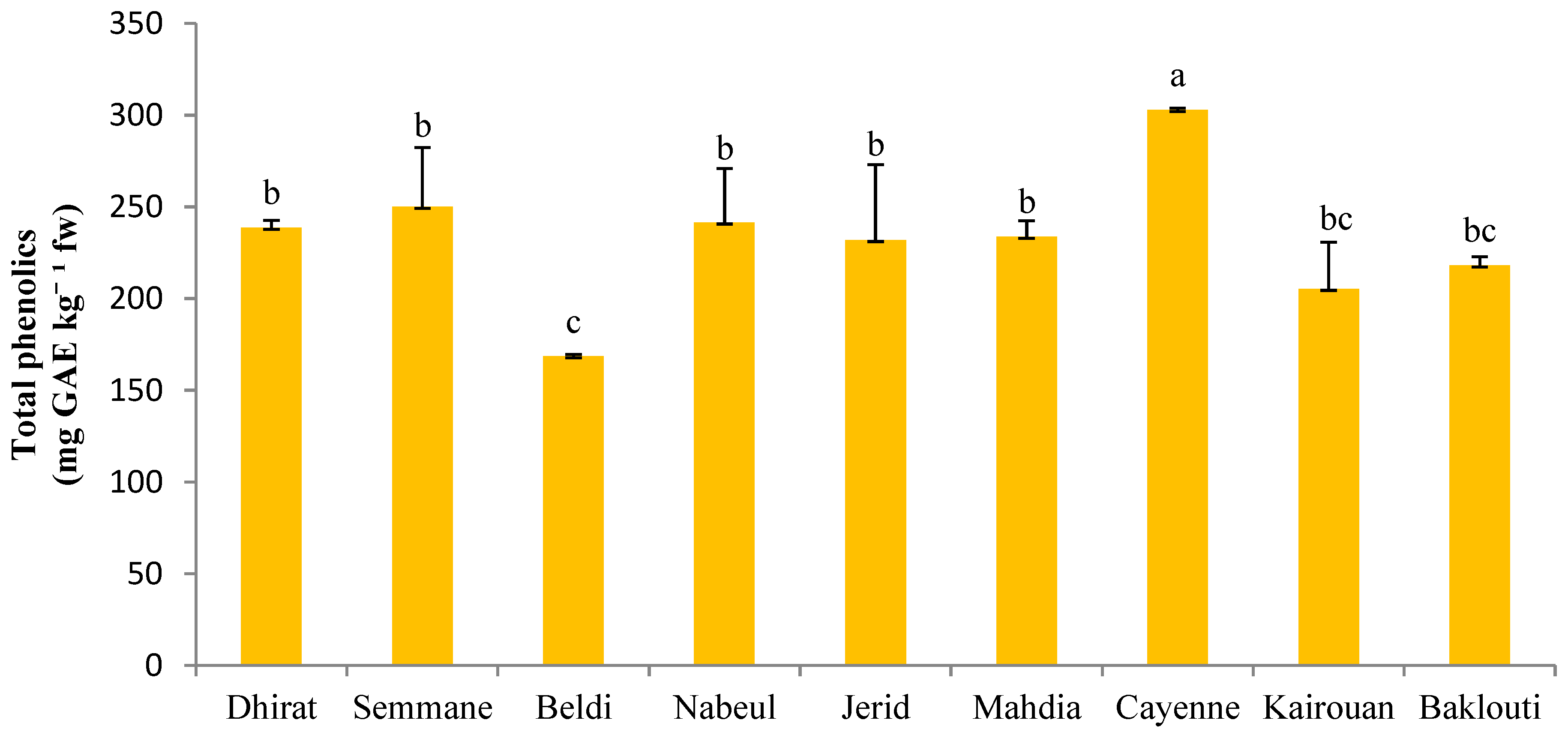

3.2.5. Total Phenols

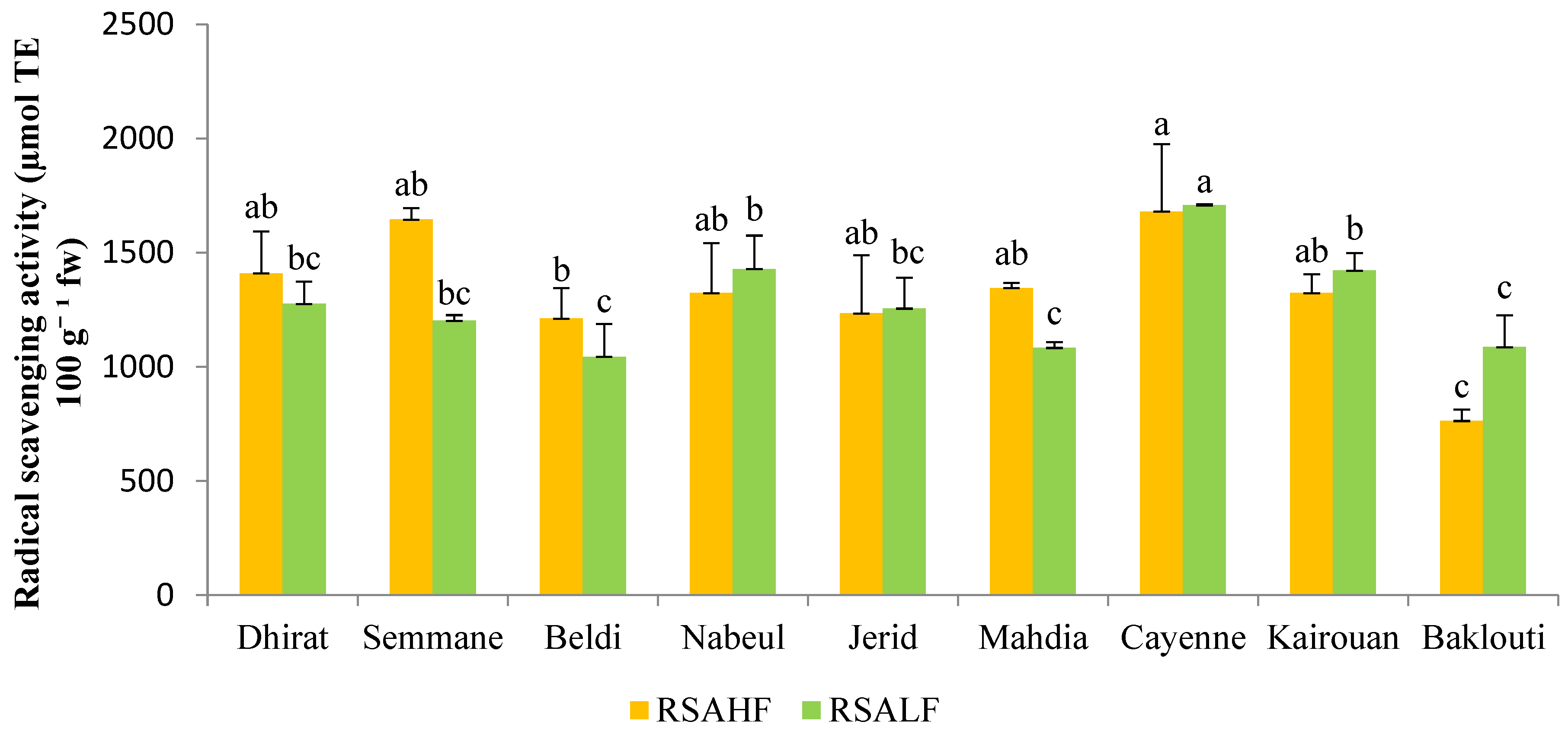

3.2.6. Radical Scavenging Activity

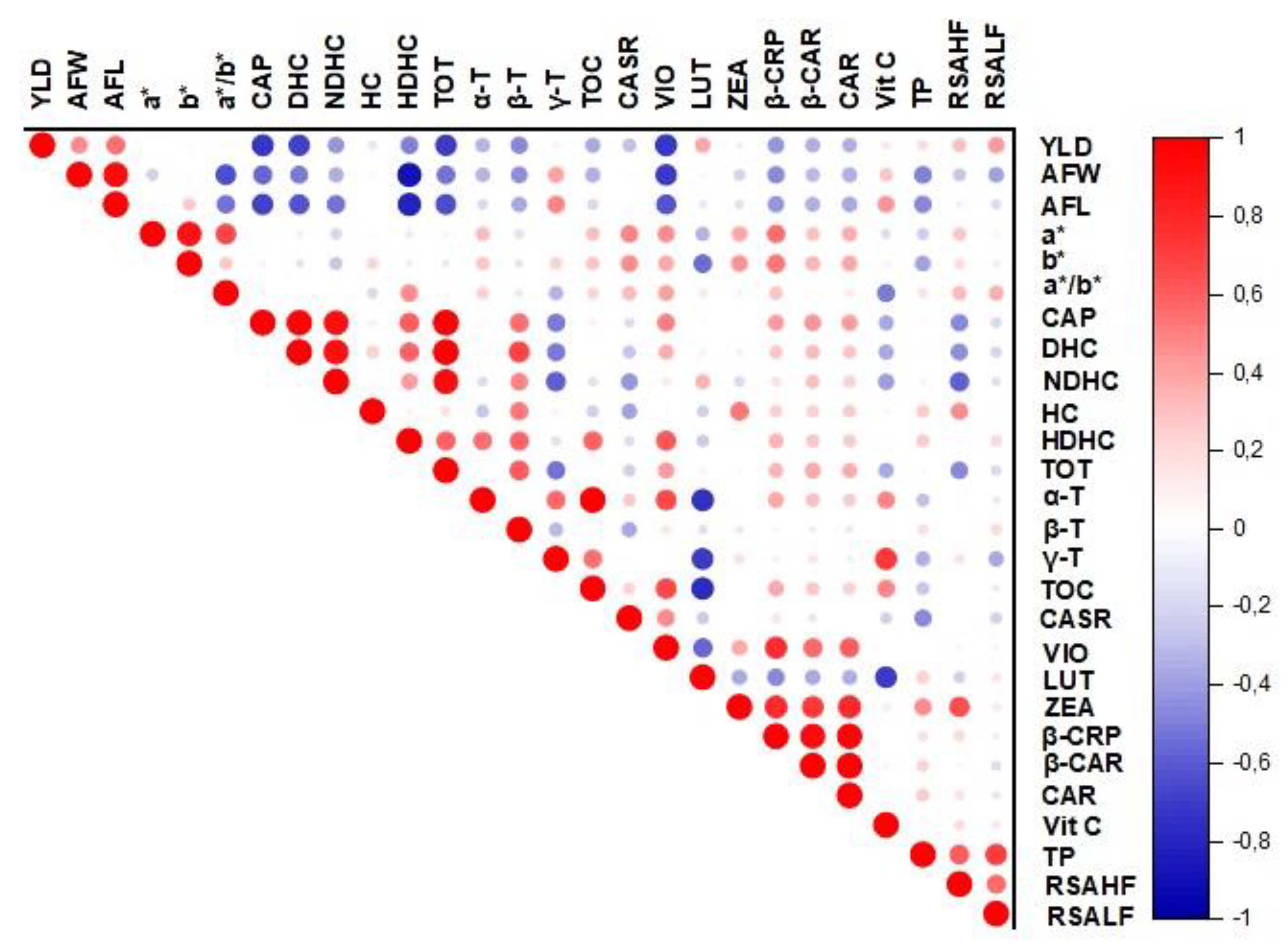

3.3. Correlation Analysis

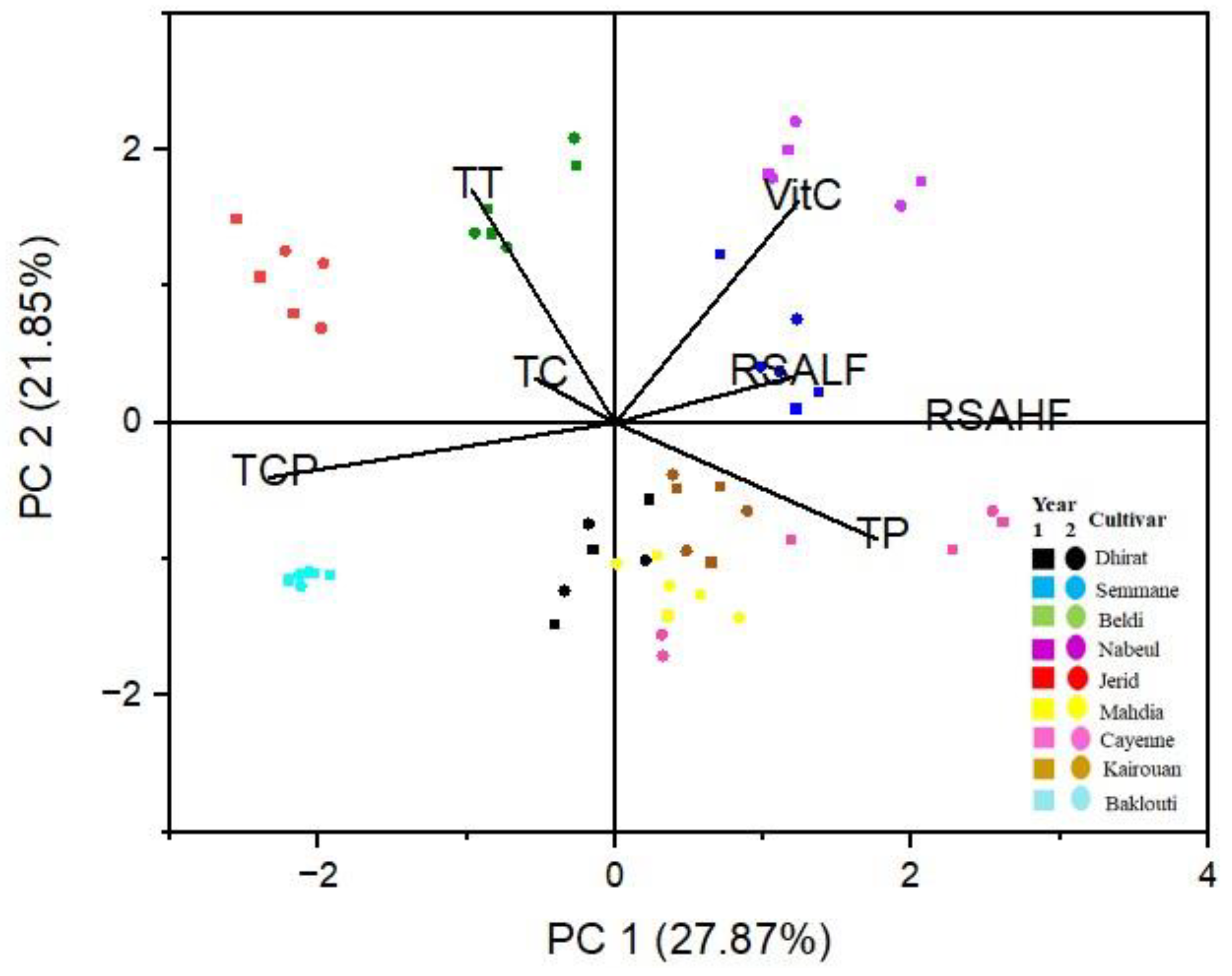

3.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duah, S.A.; Souza, C.S.; Daood, H.G.; Pék, Z.; Neményi, A.; Helyes, L. Content and response to Ɣ-irradiation before over-ripening of capsaicinoid, carotenoid, and tocopherol in new hybrids of spice chili peppers. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 147, 111555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, A.; Atasoy, A.F.; Hayaloglu, A.A. The effects of production methods on the color characteristics, capsaicinoid content and antioxidant capacity of pepper spices (C. annuum L.). Food Chem. 2021, 341, 128184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civan, M.; Kumcuoglu, S. Green ultrasound-assisted extraction of carotenoid and capsaicinoid from the pulp of hot pepper paste based on the bio-refinery concept. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 113, 108320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, N.; Jebari, H.; R’him, T.; Hdider, C.; Khamassy, N.; Ilahy, R.; Tlili, I. Historique et principaux acquis de l’INRAT en matière de cultures maraîchères. Annales de l’INRAT 2013, 86, Numéro Spécial Centenaire.

- Corrado, G.; Caramante, M.; Piffanelli, P.; Rao, R. Genetic diversity in Italian tomato landraces: Implications for the development of a core collection. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 168, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zahra, T.R. Influence of agricultural practices on fruit quality of bell pepper. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 14(18), 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Min, Z.; Fan, D.; Kai, F.; Wang, X. Linear regression between CIE-Lab color parameters and organic matter in soils of tea plantations. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2018, 51, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daood, H.G.; Bencze, G.; Palotas, G.; Pék, Z.; Sidikov, A.; Helyes, L. HPLC analysis of carotenoids from tomatoes using cross-linked C18 column and MS detection. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2014, 52, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushita, A.A.; Hebshi, E.A.; Daood, H.G.; Biacs, P.A. Determination of antioxidant vitamins in tomatoes. Food Chem. 1997, 60, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampfenkel, K.; Van Montagu, M.; Inzé, D. Extraction and determination of ascorbate and dehydroascorbate from plant tissue. Anal. Biochem. 1995, 225, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Valverde, I.; Periago, M.J.; Provan, G.; Chesson, A. Phenolic compounds, lycopene and antioxidant activity in commercial varieties of tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asami, D.K.; Hong, Y.-J.; Barrett, D.M.; Mitchell, A.E. Comparison of the total phenolic and ascorbic acid content of freeze-dried and air-dried marionberry, strawberry, and corn grown using conventional, organic, and sustainable agricultural practices. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.J.; Rice-Evans, C.A. Factors influencing the antioxidant activity determined by the ABTS•+ radical cation assay. Free Radic. Res. 1997, 26, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, I.; Ilahy, R.; Romdhane, L.; R’him, T.; Ben Mohamed, H.; Zgallai, H.; Rached, Z.; Azam, M.; Henane, I.; Saïdi, M.N.; Pék, Z.; Daood, H.G.; Helyes, L.; Hdider, C.; Lenucci, M.S. Functional quality and radical scavenging activity of selected watermelon (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Mansfeld) genotypes as affected by early and full cropping seasons. Plants 2023, 12, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laayouni, Y.; Tlili, I.; Henane, I.; Ahlem, B.A.; Égei, M.; Takács, S.; Azam, M.; Siddiqui, M.W.; Daood, H.; Pék, Z.; Helyes, L.; R’him, T.; Lenucci, M.S.; Ilahy, R. Phytochemical profile and antioxidant activity of some open-field ancient-tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) genotypes and promising breeding lines. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, J.A.; Nabi, G.; Khan, M.; Ahmad, S.; Shah, P.S.; Hussain, S.; Sehrish. Foliar application of humic acid improves growth and yield of chilli (Capsicum annum L.) varieties. Pak. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 33, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriani, L. ; Toekidjo; Purwanti, S. The performance of five cultivated varieties of pepper (Capsicum annum L.) at the middle land. Vegetalika 2013, 2, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ilić, Z.S.; Kevrešan, Ž.; Mastilović, J.; Zorić, L.; Tomšik, A.; Belović, M.; Pestorić, M.; Karanović, D.; Luković, J. Evaluation of mineral profile, texture, sensory and structural characteristics of old pepper landraces. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e13141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilhante, B.D.G.; Santos, T.d.O.; Cansian Júnior, J.C.; Rodrigues, V.A.P.; Almeida, R.d.; Santos, J.O.; Souza Neto, J.D.; Júnior, A.C.S.; Menini, L.; Bento, C.d.S.; Moulin, M.M. Fruit quality and morphoagronomic characterization of a Brazilian Capsicum germplasm collection. Genet. Mol. Res. 2024, 23, GMR19197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, G.F.; Ruiz, A.G.; Liazid, A.; Palma, M.; Vera, J.C.; Barroso, C.G. Evolution of total and individual capsaicinoids in peppers during ripening of the Cayenne pepper plant (Capsicum annuum L.). Food Chem. 2014, 153, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeeatid, N.; Suriharn, B.; Techawongstien, S.; Chanthai, S.; Bosland, P.W.; Techawongstien, S. Evaluation of the effect of genotype-by-environment interaction on capsaicinoid production in hot pepper hybrids (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) under controlled environment. Scientia Hortic. 2018, 235, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Aguilar, C.C.; Castilla, L.L.; Pacheco, N.; Cuevas-Bernardino, J.C.; Garruña, R.; Andueza-Noh, R.H. Phenotypic diversity and capsaicinoid content of chilli pepper landraces (Capsicum spp.) from the Yucatan Peninsula. Plant Genet. Resour. 2021, 19, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Saleh, M.; Mohsin, G.M.; Nadirah, T.A.; Aslani, F.; Rahman, M.M.; Roy, S.K.; Juraimi, A.S.; Alam, M.Z. Evaluation of phenolics, capsaicinoids, antioxidant properties, and major macro-micro minerals of some hot and sweet peppers and ginger land-races of Malaysia. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Ro, N.; Kim, J.; Ko, H. C.; Lee, S.; Oh, H.; Kim, B.; Lee, H.-S.; Lee, G. A. Characterization of diverse pepper (Capsicum spp.) germplasms based on agro-morphological traits and phytochemical contents. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Sánchez, D.D.; López-Sánchez, H.; Silva-Rojas, H.V.; Gardea-Béjar, A.A.; Cruz-Huerta, N.; Ramírez-Ramírez, I.; González-Hernández, V.A. Pungency and fruit quality in Mexican landraces of piquín pepper (Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum) as affected by plant growth environment and postharvest handling. Chilean J. Agric. Res. 2021, 81, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E.; Sánchez-Prieto, M.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B. Assessment of carotenoid concentrations in red peppers (Capsicum annuum) under domestic refrigeration for three weeks as determined by HPLC-DAD. Food Chemistry: X 2020, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiani, G.; Castón, M.J.; Catasta, G.; Toti, E.; Cambrodón, I.G.; Bysted, A.; Granado-Lorencio, F.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Knuthsen, P.; Valoti, M., Böhm, V., Mayer-Miebach, E.; Behsnilian, D.; Schlemmer, U. Carotenoids: actual knowledge on food sources, intakes, stability and bioavailability and their protective role in humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009, 53, S194–218. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Ispizua, E.; Martínez-Cuenca, M.R.; Marsal, J.I.; Díez, M.J.; Soler, S.; Valcárcel, J.V.; Calatayud, Á. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of Valencian pepper landraces. Molecules 2021, 26, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silveira Agostini-Costa, T.; da Silva Gomes, I.; de Melo, L.A.M.P.; Reifschneider, F.J.B.; da Costa Ribeiro, C.S. Carotenoid and total vitamin C content of peppers from selected Brazilian cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 57, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanner, J.; Harel, S.; Mendel, H. Content and stability of R-tocopherol in fresh and dehydrated pepper fruits (Capsicum annuum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1979, 27, 1316–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna-Garcia, J.A.; Wall, M.M.; Waddell, C.A. Endogenous levels of tocopherols and ascorbic acid during fruit ripening of New Mexican-type chile (Capsicum annuum L.) cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 5093–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, K.; Pinar, H.; Ciftci, B.; Kaplan, M. Characterization of phenolics and tocopherol profile, capsaicinoid composition and bioactive properties of fruits in interspecies (Capsicum annuum x Capsicum frutescens) recombinant inbred pepper lines (RIL). Food Chem. 2023, 423, 136173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smirnoff, N.; Wheeler, G. L. Ascorbic acid in plants: Biosynthesis and function. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2000, 19, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.; López, M.; González-Raurich, M.; Bernardo Álvarez, A. The effects of ripening stage and processing systems on vitamin C content in sweet peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 56, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, J.C.; Parulekar, Y.R. El pimiento. In: Tratado de Ciencia y Tecnología de las Hortalizas. Zaragoza, Spain: Acriba; 2004. pp 203-225.

- Lee, Y.; Howard, L.R.; Villalon, B. Flavonoids and antioxidant activity of fresh pepper (Capsicum annuum) cultivars. J. Food Sci. 1995, 60, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, O.A.; Rao, S.A.; Tata, S.S. Phenolics quantification in some genotypes of Capsicum annuum L. J. Phytol. Phytophysiol. 2010, 2, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, C.K.B.; Torres, E.A.F.S. Biochemical pharmacology of functional foods and prevention of chronic diseases of aging. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2003, 57, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R. J.; Spencer, J. P. E.; Rice-Evans, C. Flavonoids: antioxidants or signalling molecules? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Jubete, L.; Wijngaard, H.; Arendt, E.K.; Gallagher, E. Polyphenol composition and in vitro antioxidant activity of amaranth, quinoa, buckwheat and wheat as affected by sprouting and baking. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboh, G.; Rocha, J.B.T. Polyphenols in red pepper [Capsicum annuum var. aviculare (Tepin)] and their protective effect on some pro-oxidants induced lipid peroxidation in brain and liver. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 225, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vásquez, R.; Vera-Guzmán, A.M.; Carrillo-Rodríguez, J.C.; Pérez-Ochoa, M.L.; Aquino-Bolaños, E.N.; Alba-Jiménez, J.E.; Chávez-Servia, J. L. Bioactive and nutritional compounds in fruits of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) landraces conserved among indigenous communities from Mexico. AIMS Agric. Food 2023, 8. http://www.aimspress.com/journal/agriculture.

- Constantino, L.V.; Fukuji, A.Y.S.; Zeffa, D.M.; Baba, V.Y.; Corte, E.D.; Giacomin, R.M.; Vilela Resende, J.T.; Gonçalves, L.S.A. Genetic variability in peppers accessions based on morphological, biochemical and molecular traits. Bragantia 2020, 79, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Aragón, M.G.; Troyo-Diéguez, E.; Preciado-Rangel, P.; Borroel-García, V.J.; García-Carrillo, E.M.; García-Hernández, J.L. Antioxidant profile of hot and sweet pepper cultivars by two extraction methods. Hortic. Bras. 2023, 40, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivar | Earliness | Fruit shape | Intended use | Yield per plant (g plant−1) |

Average fruit length (cm) | Average fruit weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dhirat | Early | Elongate | Fresh market | 1480.58 ± 36.11 d | 11.67 ± 1.11 de | 22.25 ± 0.83 d |

| Semmane | Late | Elongate | Fresh market | 1687.25 ± 40 c | 17.33 ± 1.78 abc | 34.33 ± 1.11 bc |

| Beldi | Early | Elongate | Fresh market/Processing | 1755.08 ± 56.22 c | 18 ± 2 abc | 34.33 ± 1.11 bc |

| Nabeul | Late | Elongate | Fresh market | 1720.83 ± 56.22 c | 18.67 ± 2.44 ab | 35.58 ± 0.89b c |

| Jerid | Early | Triangular | Pickling | 1163.25 ± 47.17 e | 5.33 ± 1.56 f | 6.5 ± 0.5 f |

| Mahdia | Late | Elongate | Fresh market | 1634.92 ± 22.55 c | 13.67 ± 1.11 cde | 33.83 ± 0.39 c |

| Cayenne | Very late | Elongate | Pickling | 1997.33 ± 11.61 a | 9.33 ± 1.56 ef | 14.25 ± 0.5 e |

| Kairouan | Late | Elongate | Fresh market/processing | 1841.67 ± 17.94 b | 20.33 ± 2.22 a | 37.75 ± 0.17 a |

| Baklouti | Late | Triangular | Fresh market/processing | 1644.08 ± 29.61 c | 14.67 ± 1.78 bcd | 35.75 ± 0.17 b |

| Cultivar | Soluble solids (°Brix) | pH | Titratable Acidity (%) | a* | b* | a*/b* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dhirat | 10.6 ± 0.3 bc | 4.95 ± 0.006 c | 0.21 ± 0.01bcd | 36.68 ± 0.76 bc | 40.47 ± 0.04 bc | 0.91 ± 0.02 bcd |

| Semmane | 9.1 ± 0.1e | 4.93 ± 0.05 cd | 0.16 ± 0.04 f | 40.33 ± 1.27 a | 44.81 ± 1.52 a | 0.9 ± 0.01 bcd |

| Beldi | 12.2 ± 0.36 a | 4.97 ± 0.02 c | 0.19 ± 0.01 def | 40.9 ± 1.38 a | 43.59 ± 0.76 a | 0.94 ± 0.01 abc |

| Nabeul | 10.9 ± 0.9 bc | 4.85 ± 0.02 cd | 0.31 ± 0.03 a | 33.94 ± 1.23 c | 39.32 ± 0.94 c | 0.87 ± 0.03 d |

| Jerid | 10.63 ± 0.06 bc | 5.02 ± 0.01 c | 0.22 ± 0.02bcd | 40.57 ± 0.98 a | 42.9 ± 1.2 ab | 0.95 ± 0.004 ab |

| Mahdia | 10.6 ± 0.53 bc | 5.35 ± 0 b | 0.16 ± 0 ef | 34.82 ± 1.43 c | 38.36 ± 1.87 c | 0.91 ± 0.006 bcd |

| Cayenne | 9.6 ± 0.1 de | 5.6 ± 0.35 a | 0.2 ± 0.3 cde | 38.81 ± 1.2 ab | 39.82 ± 1.16 c | 0.97 ± 0.004 a |

| Kairouan | 10.1 ± 0.7 cd | 5.02 ± 0 c | 0.24 ± 0.03 bc | 41.35 ± 0.59 a | 44.48 ± 1.68 a | 0.93 ± 0.02 abc |

| Baklouti | 11.4 ± 0.2 ab | 4.72 ± 0.01 e | 0.25 ± 0.01 b | 35.43 ± 0.77 c | 39.58 ± 0.53 c | 0.89 ± 0.03 cd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).