1. Introduction

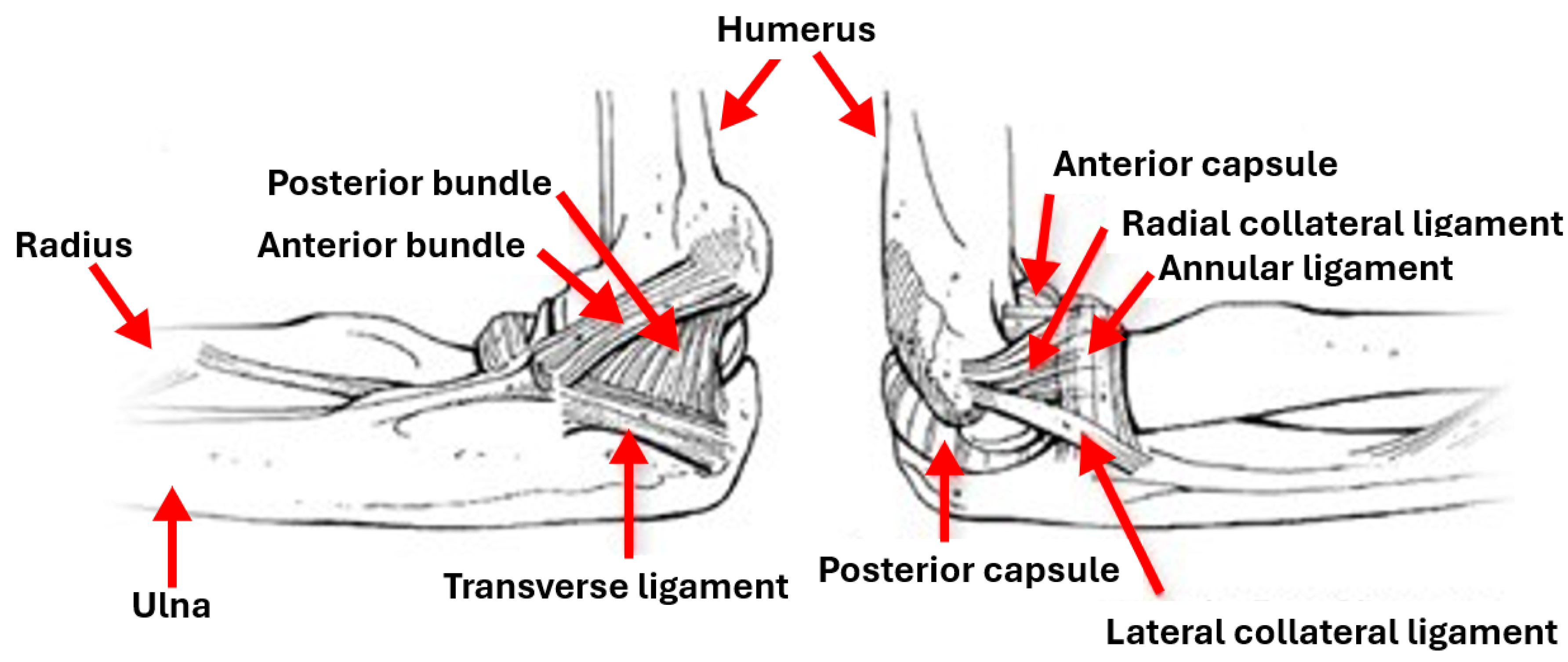

The elbow is a joint connecting the upper and lower arms humerus and radius and ulna parts, with a complex structure that is supported by soft tissues [

2]. It comprises three separate joints: ulnohumeral where movement between the ulna and the proximal humerus occurs, radiohumeral where movement between the radius and the humerus occurs and superior radioulnar where movement between the radius and the ulna occurs. Ligaments form the joint capsule, hold the bones together and play an important role in maintaining the elbow stability and preventing dislocations. Four main ligaments exist: the ulnar collateral ligament, the radial collateral ligament, the annular ligament and the quadrate ligament.

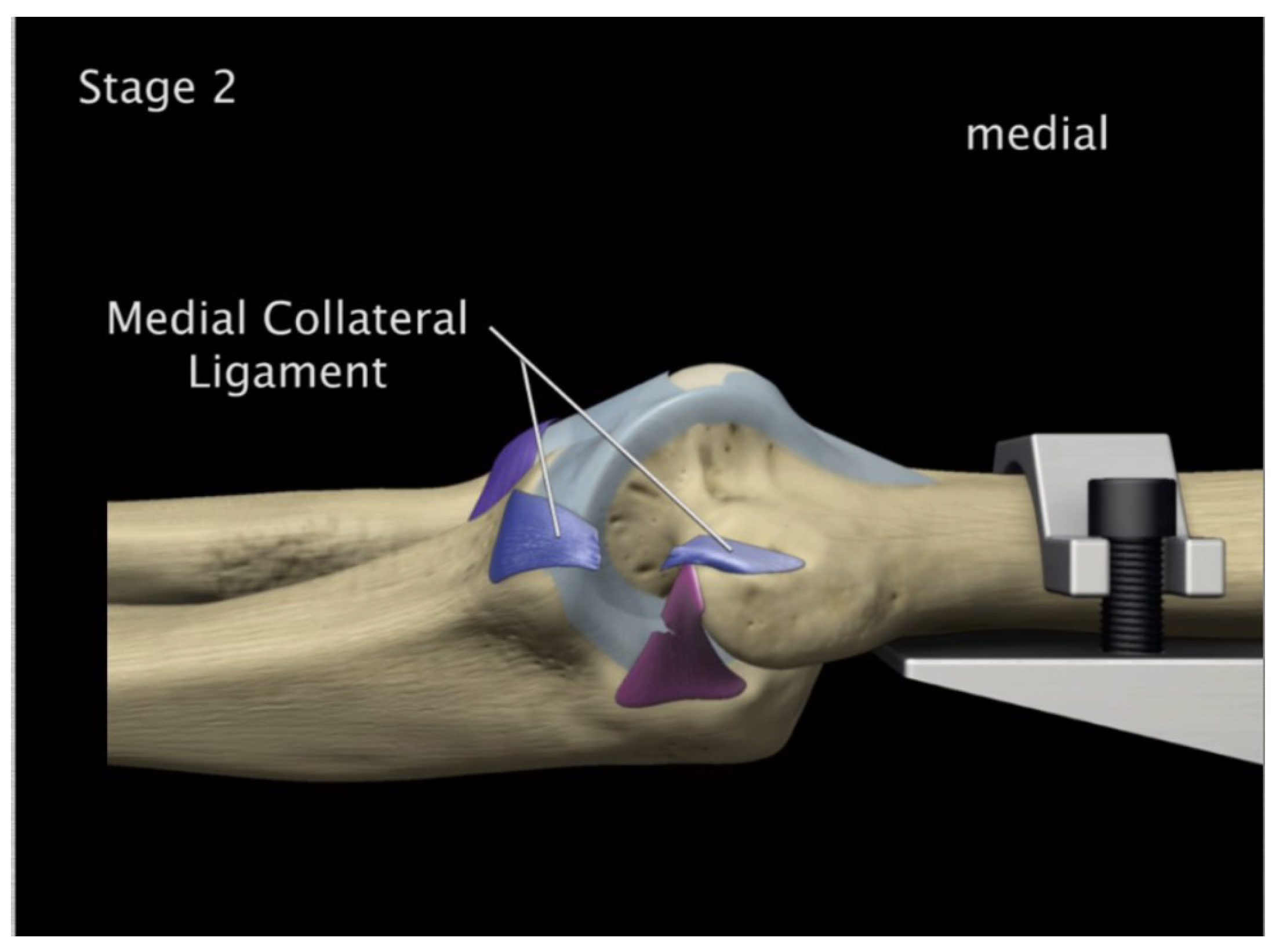

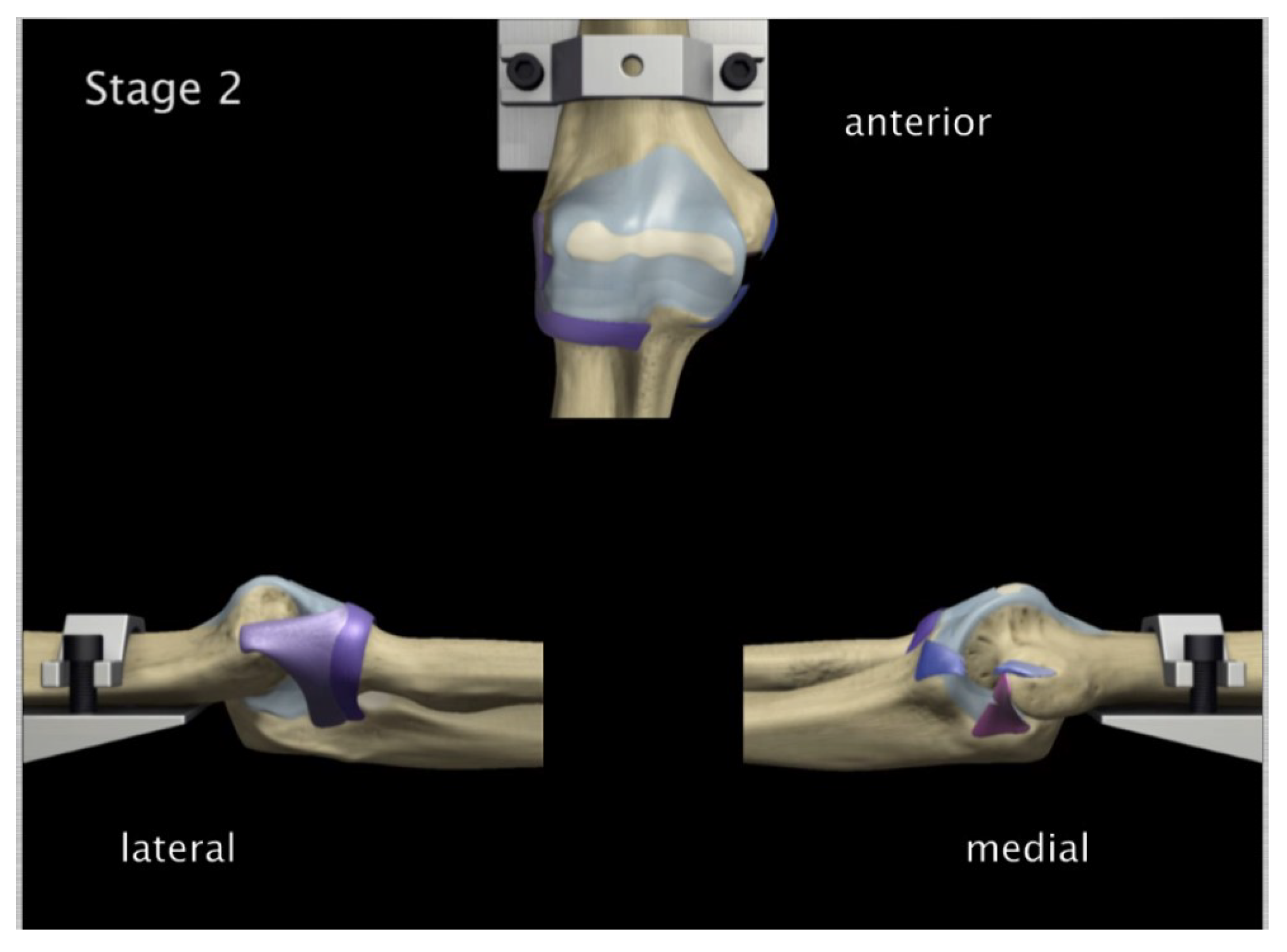

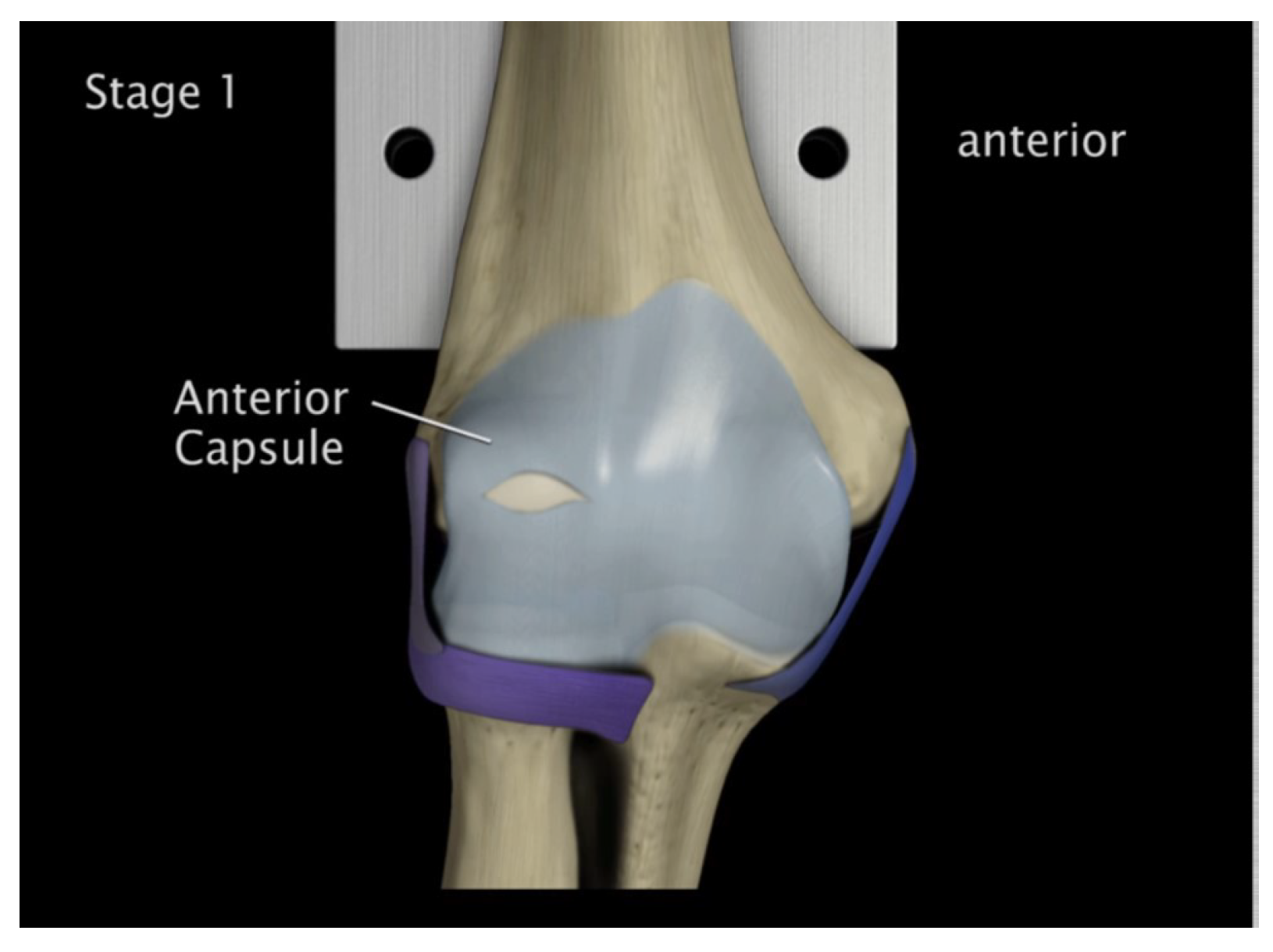

Figure 1 shows different parts involved in the elbow: ulna, radius, humerus, capsules, bundles and ligaments. The elbow allows motions controlled by the contraction (flexion) and relaxation (extension) of muscles, and its range of motion is related to age, sex and body mass index [

3]. The musculotendinous units overlying the ulnar collateral ligament play an important role in maintaining the dynamic valgus stability of the elbow [

4]. Other elements like bone surfaces, capsule and muscles affect the elbow’s range of motion and have stabilizing effects.

Among other joints, the elbow is the most frequently dislocated in children and the second most frequently dislocated in adults, after the shoulder [

5]. Elbow injuries can be seen in sports [

4,

6,

7] and other accidents like falls from heights [

8], and traffic and machine accidents [

9]. Elbow dislocations can affect the hand’s motion and functionality and result from injury mechanisms associated to high energy impacts like falling onto an outstretched hand [

10]. Another known mechanism for elbow dislocation is hyperextention force with the forearm supinated [

11,

12]. They can be simple without fracture or complex with fractures and their treatment may require surgical intervention [

5]. Additionally, they can be classified according to their directions as they can be posterior, lateral, medial, posterolateral, posteromedial or divergent. In elbow dislocation, any of the bone surfaces, ligaments, capsule and muscles can be injured. For the treatment of elbow dislocations, it is not enough to understand the anatomy and the interactions between the bony articulations. Recognizing the precise injury pattern is critical as it helps to restore the functionality and to prevent chronic instability at the elbow [

13].

This study aims to improve the understanding of elbow dislocation mechanics and stages. This is a challenging problem in biomechanics and many models attempted to solve it by focusing on inverse dynamics using mathematical models to determine muscles forces [

14]. The current approach is to establish finite element models of the different parts of the elbow with a high fidelity that allows realistic and precise simulations of different scenarios and underlying conditions. The approach adopted in this study follows the following steps:

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 shows previous work in finite element modeling of human elbows.

Section 3 shows the process followed in this study to establish finite element models of elbows, with boundary conditions and contacts developed in

Section 4. Results are shown and discussed in

Section 5 and a conclusion ends the paper.

2. Finite Element Analysis and Elbow Models

Finite element analysis (FEA) of structural stresses was seen in orthopedics since 1972 [

15]. In this area, applications of finite element stress analysis covered bones, bone-prosthesis structures, fracture fixation devices and tissues [

15]. Since then, the development of computing devices and the increase in their performances has positively affected the usage of FEA in orthopaedic bio-mechanics [

16,

17]. Indeed, FEA can be seen in different parts of the human body [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] and in several applications related to orthopedics, like implant design [

23], alloys for fractures and tissues rehabilitation design [

24], and other aspects of orthopedic and trauma surgery [

25]. Previous work on finite element analysis of the elbow joint had different objectives. Mainly, while some studies addressed fractures and dislocations, others addressed the behavior of different elements under load. Also, other aspects were addressed in FEA like elbow prostheses.

In [

26], MRI results were used to construct a finite element model for the cartilage and ligaments, which allowed to simulate different conditions for the annular ligament. Different buckling angles and muscle strengths were simulated. The used software were Solid Works and ABAQUS and the analysis addressed the load, contact area and stress, as well as the MCL stress. The authors concluded the necessity of reconstructing a ruptured annular ligament for the avoidance of clinical symptoms related to MCL and annular ligament cartilage stresses.In [

27], the humerus, ulna and radius were modeled along with other parts of the elbow and finite element analysis was performed taking into account mechanical properties of the biological tissues. A load was simulated to be applied on the distal part of the ulna-radius, as if an individual were standing on their hands. Results showed areas prone to injury, as well as the presence of stress concentrations especially in the ligament-bone relation areas. The study shown in [

28] relied on finite element analysis and aimed to reach a methodology allowing to predict the behavior of elbow-related muscles under load and during joint movements. To simplify the analysis, a 1D rod element was used instead of 3D hexahedral and tetrahedral elements. Reconstruction of the joints done using NMR images. In [

29], medical images were used to model a human elbow and study the stresses in the elbow during heavy weight lifting. Finite element analysis was used and was shown to allow the prediction of stress level and displacement in bones, and thus the safe load that can be carried without causing bone injuries.

Finite element models of 8 human cadaver elbows were developed in [

30] based on their CT scans. The study also subjected the actual elbows to loads and compared the resulting pressure distributions, stiffness’s and peak pressures with those obtained in the model. Reported results showed correlations between the two. Another study was made in [

31] where the treatment of ulna-coronoid process basal fracture with single and double screws was investigated. CT scans from 63 adult volunteers allowed to reconstruct and measure properties for the ulna and coronoid. Models of basal fractures were developed and a finite element study was made and allowed to conclude that single or double screw fixations are stable when pull-out and rotational stability factors are in reasonable conditions.In another work [

32], the bio-mechanical analysis of the elbow dislocation by a compressive force mechanism was studied. This work included a finite element analysis where CT-scan of a 32 year old male was mapped into a 2D finite element model. The model consisted of the cortical, cancellous and subchondral bones, and the cartilage. Material properties were assumed linear and isotropic. Axial loads were applied as elbow joint changed from 15º hyper-extension and 0º, 30º, 60º and 90º in flexion.

Regarding prostheses in elbows, a study was made in [

33] where FEA was relied on to analyze stresses of total elbow arthroplasty and to identify areas where implant mobilization risks exist. Elbow prosthesis models were obtained using 3D scanning and computer-aided drafting and combined with their elastic properties, resistance and stresses in the analysis. It was found in the study that some variations in positioning in the sagittal plane can result in longer implant survival. In the same vein, the study presented in [

34] investigated the mechanical behavior at the interface between the bone and the cement through FEA. It was shown that such a study can be used to provide guidelines for surgeons aiming to reduce the aseptic loosening through the implant configurations.

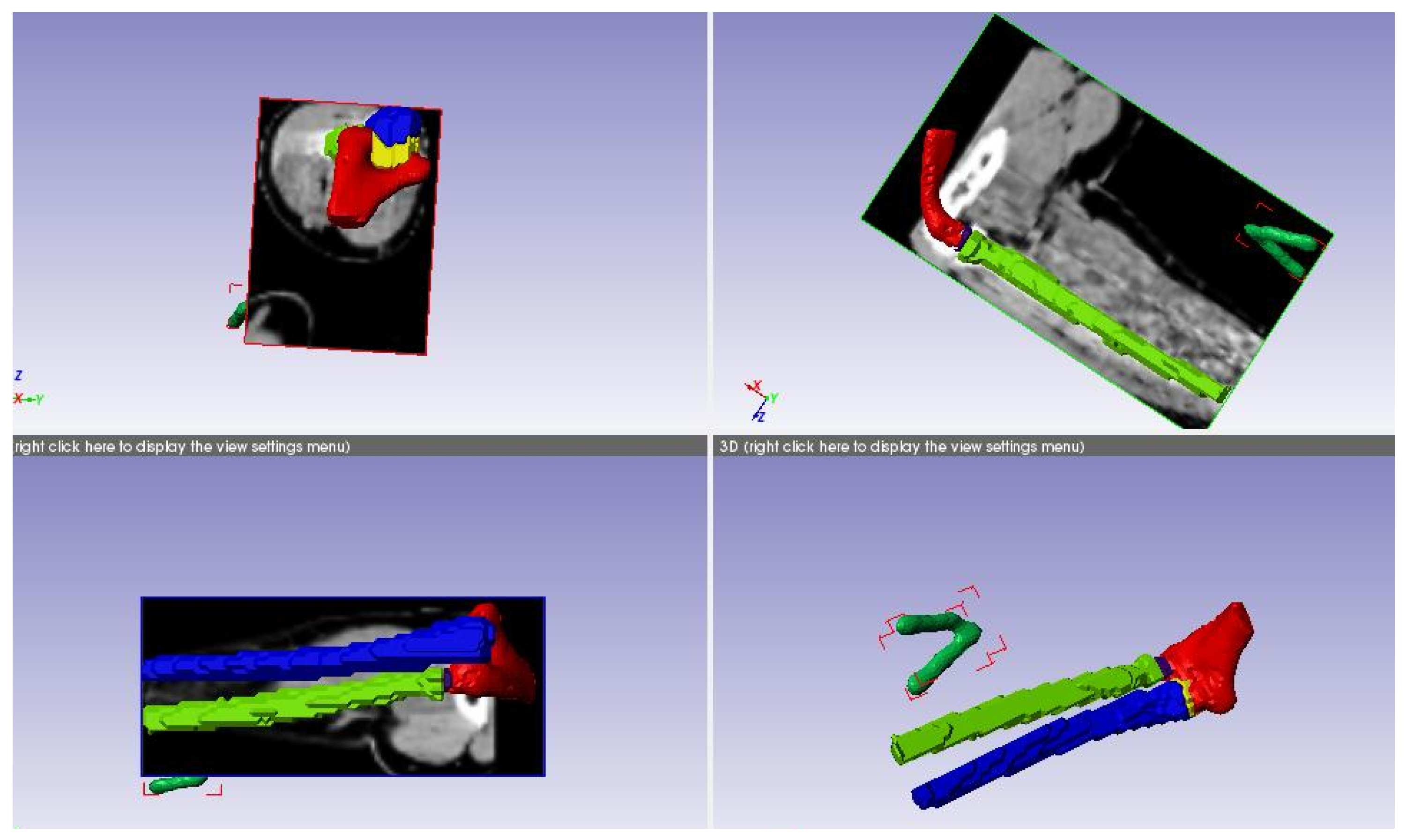

Figure 2.

3D Modeling Procedure followed

Figure 2.

3D Modeling Procedure followed

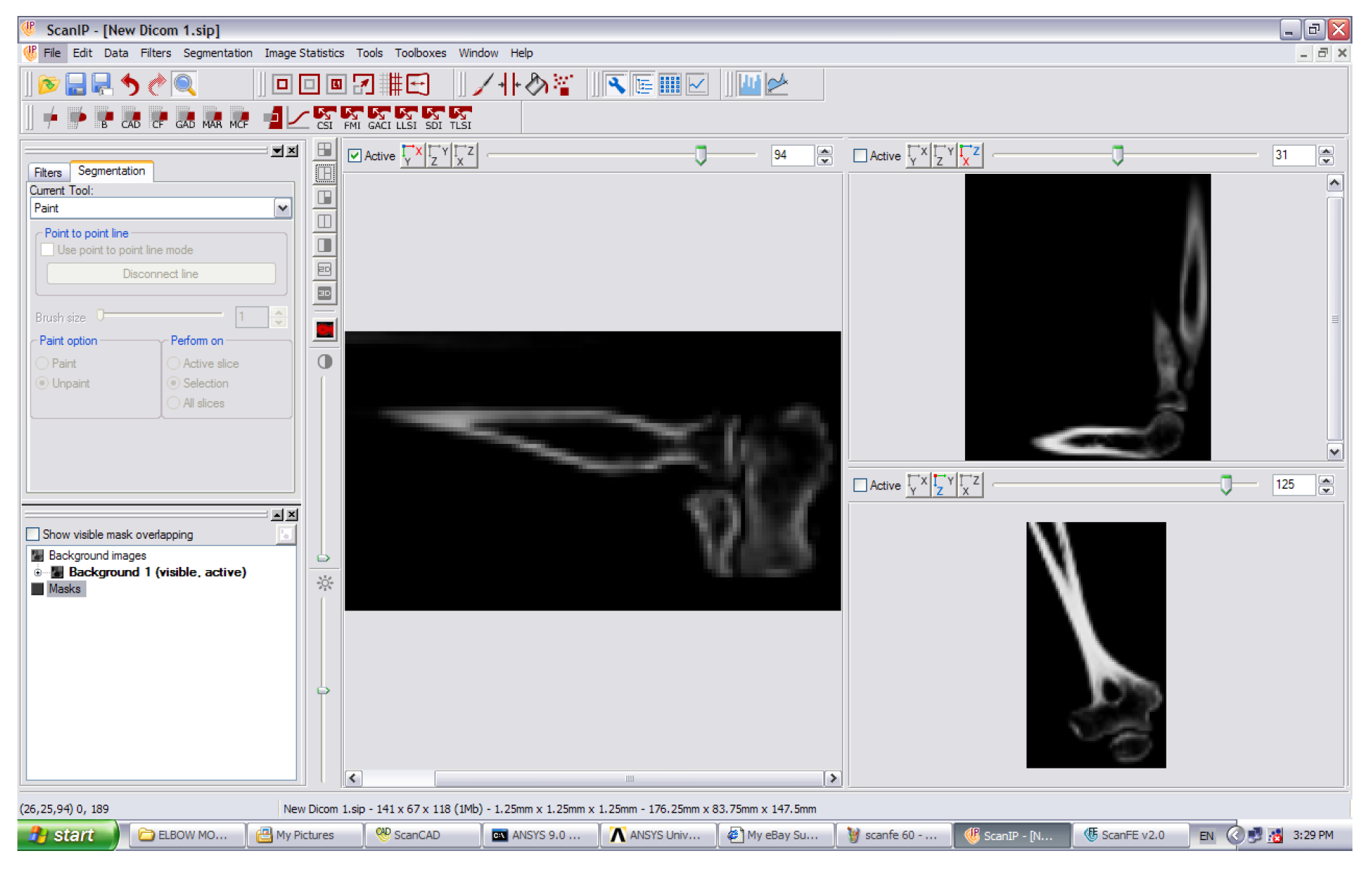

Figure 3.

CT scan data of the elbow joint.

Figure 3.

CT scan data of the elbow joint.

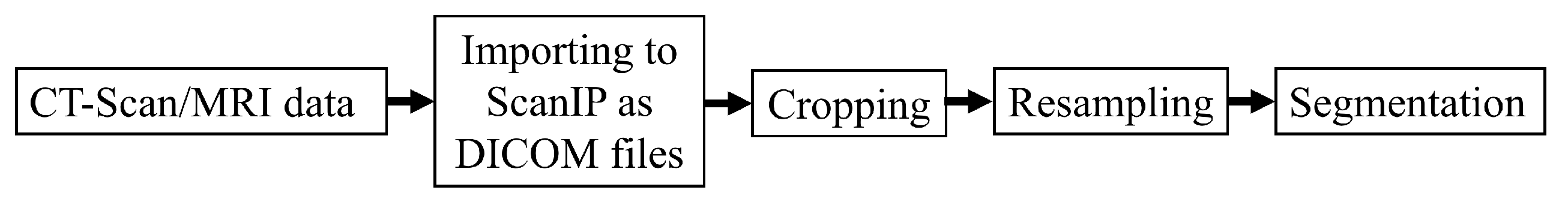

Figure 4.

Medical data processing steps

Figure 4.

Medical data processing steps

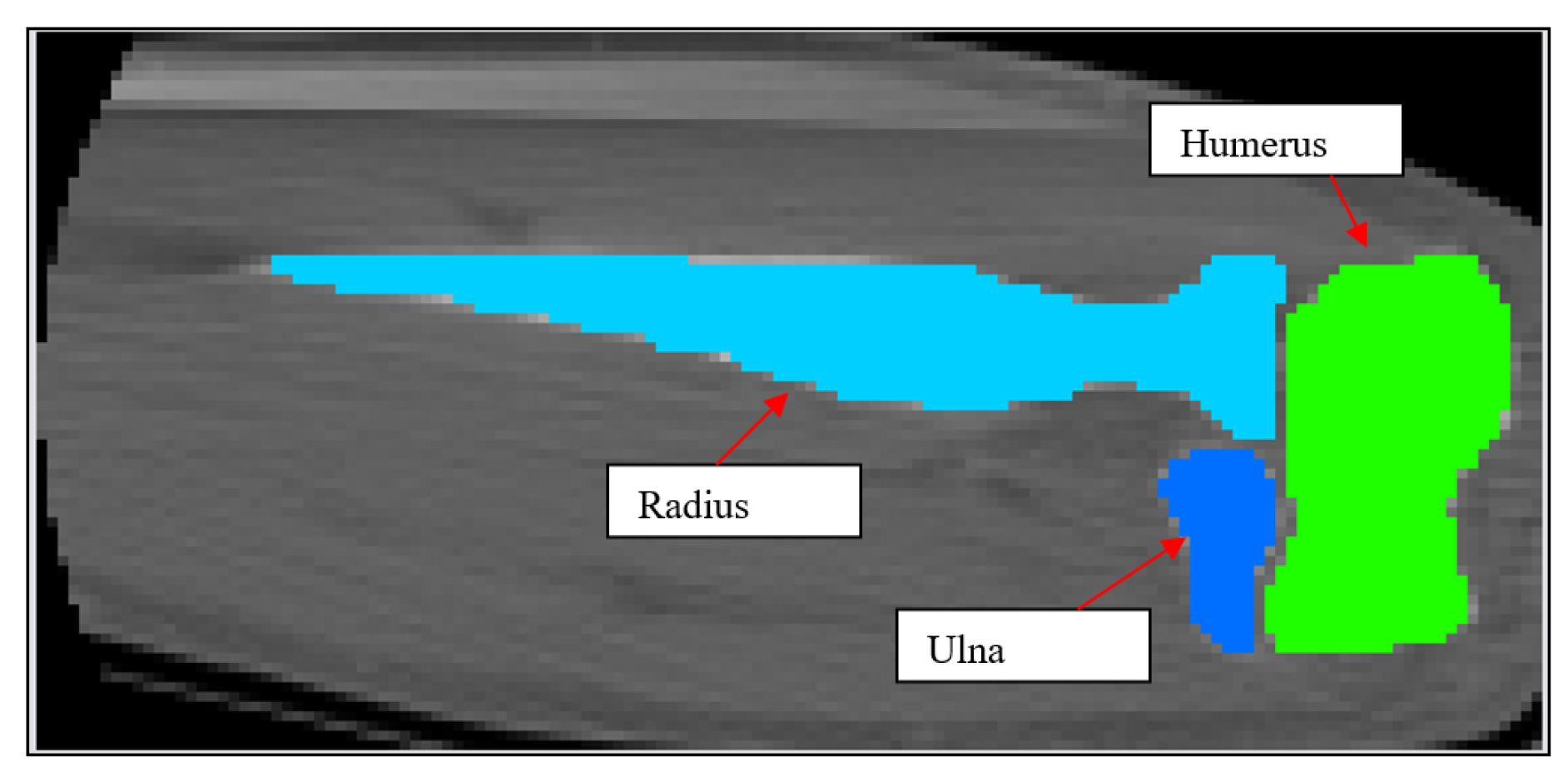

Figure 5.

2D schematic showing mask development of the humerus, ulna and radius.

Figure 5.

2D schematic showing mask development of the humerus, ulna and radius.

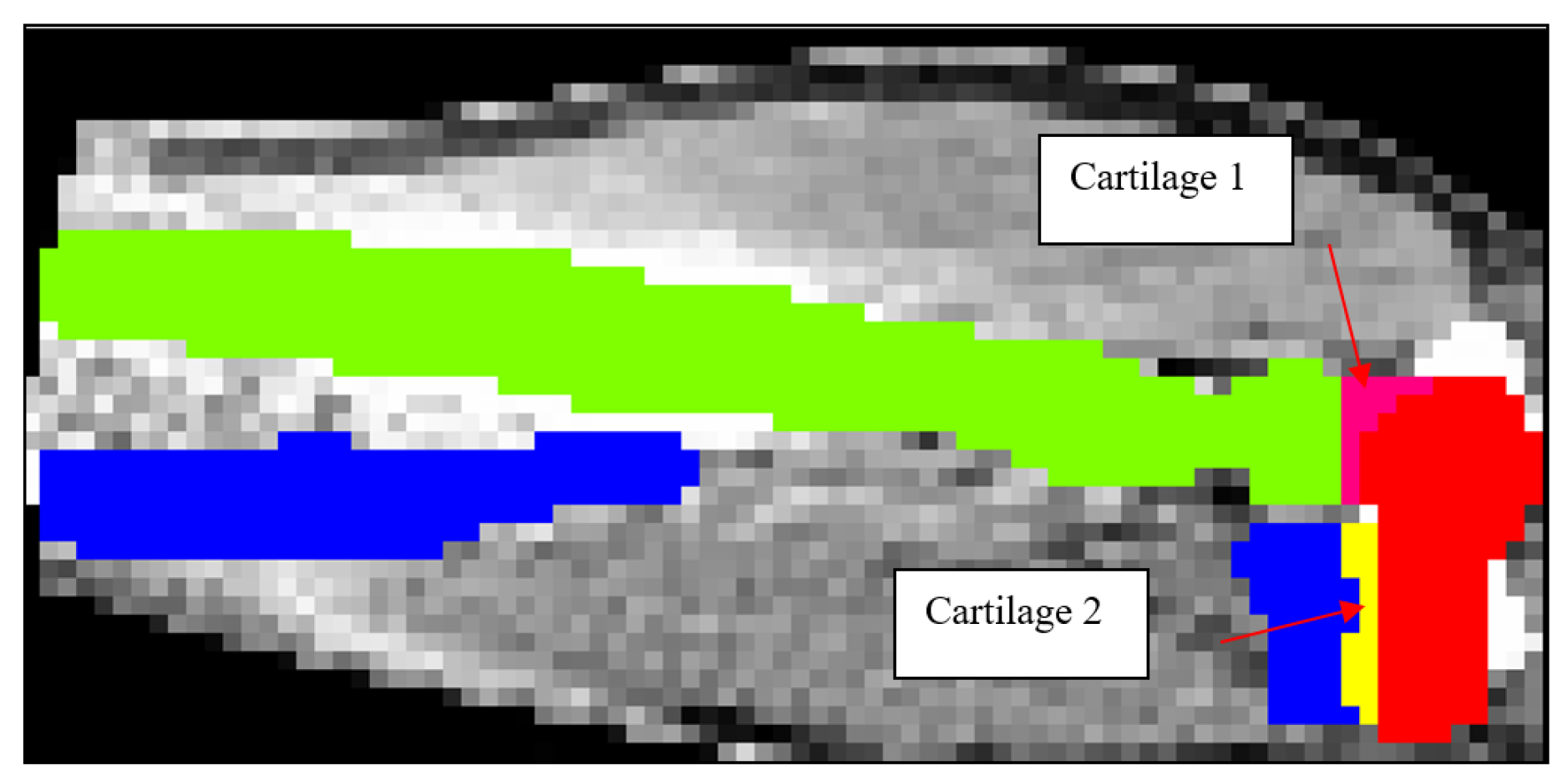

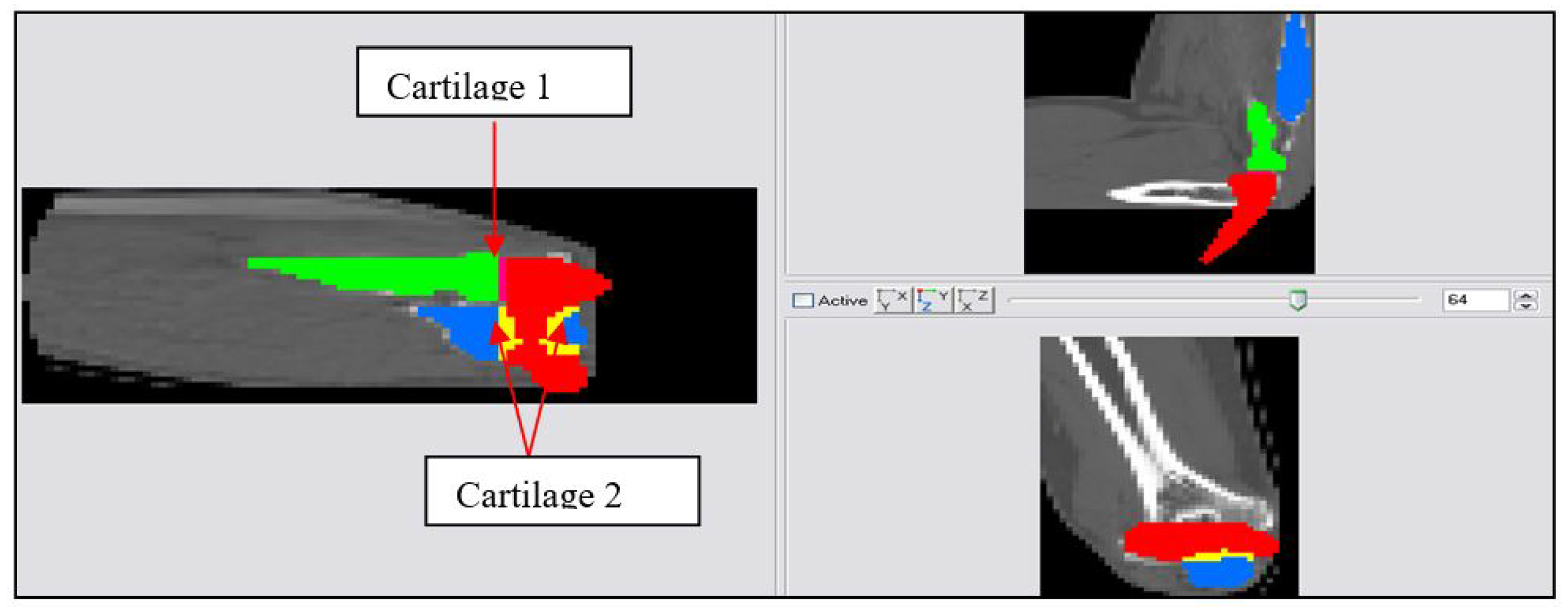

Figure 6.

2D schematic showing mask development of Cartilage 1 and Cartilage 2.

Figure 6.

2D schematic showing mask development of Cartilage 1 and Cartilage 2.

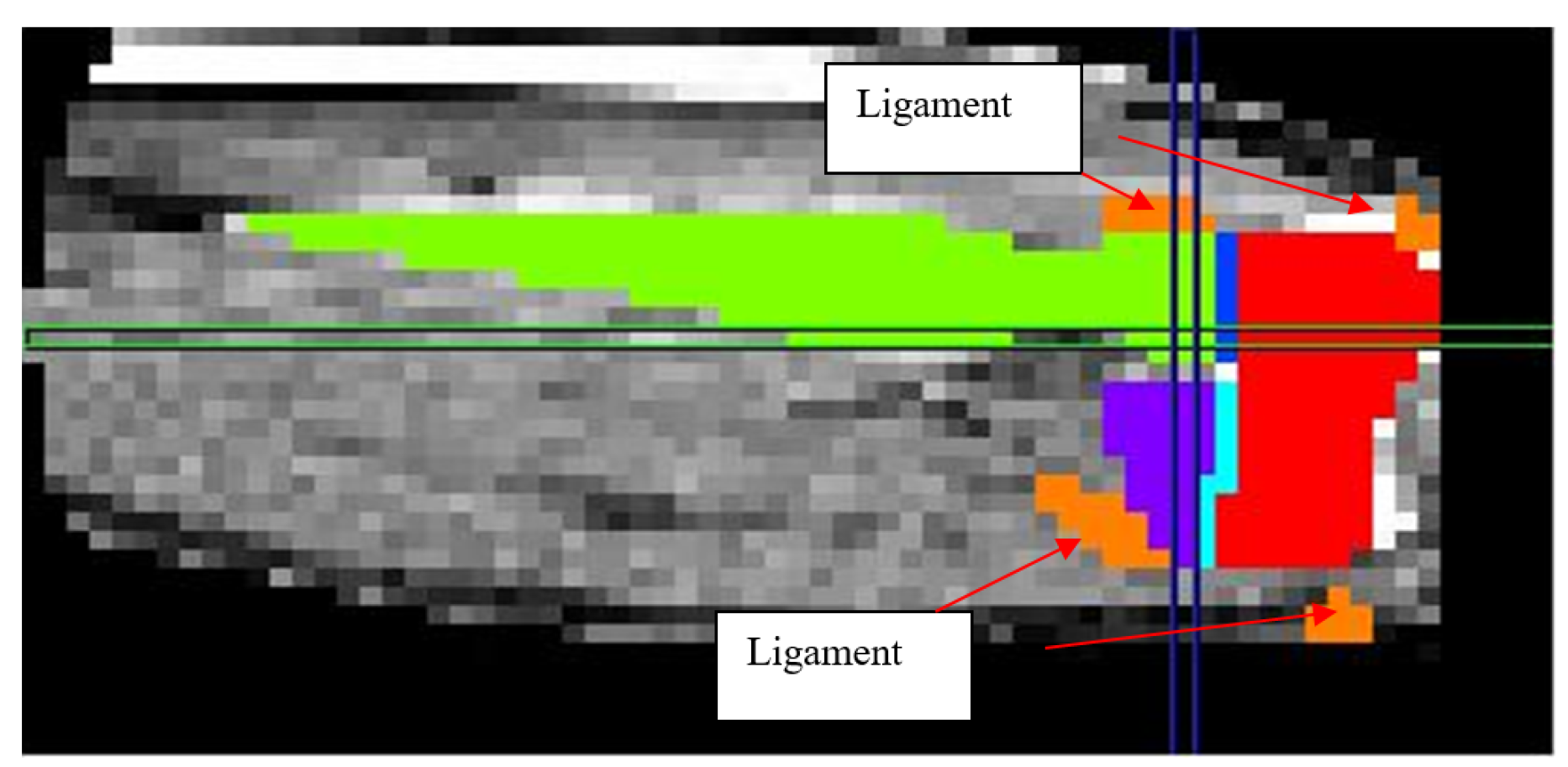

Figure 7.

2D schematic showing mask development of the ligaments.

Figure 7.

2D schematic showing mask development of the ligaments.

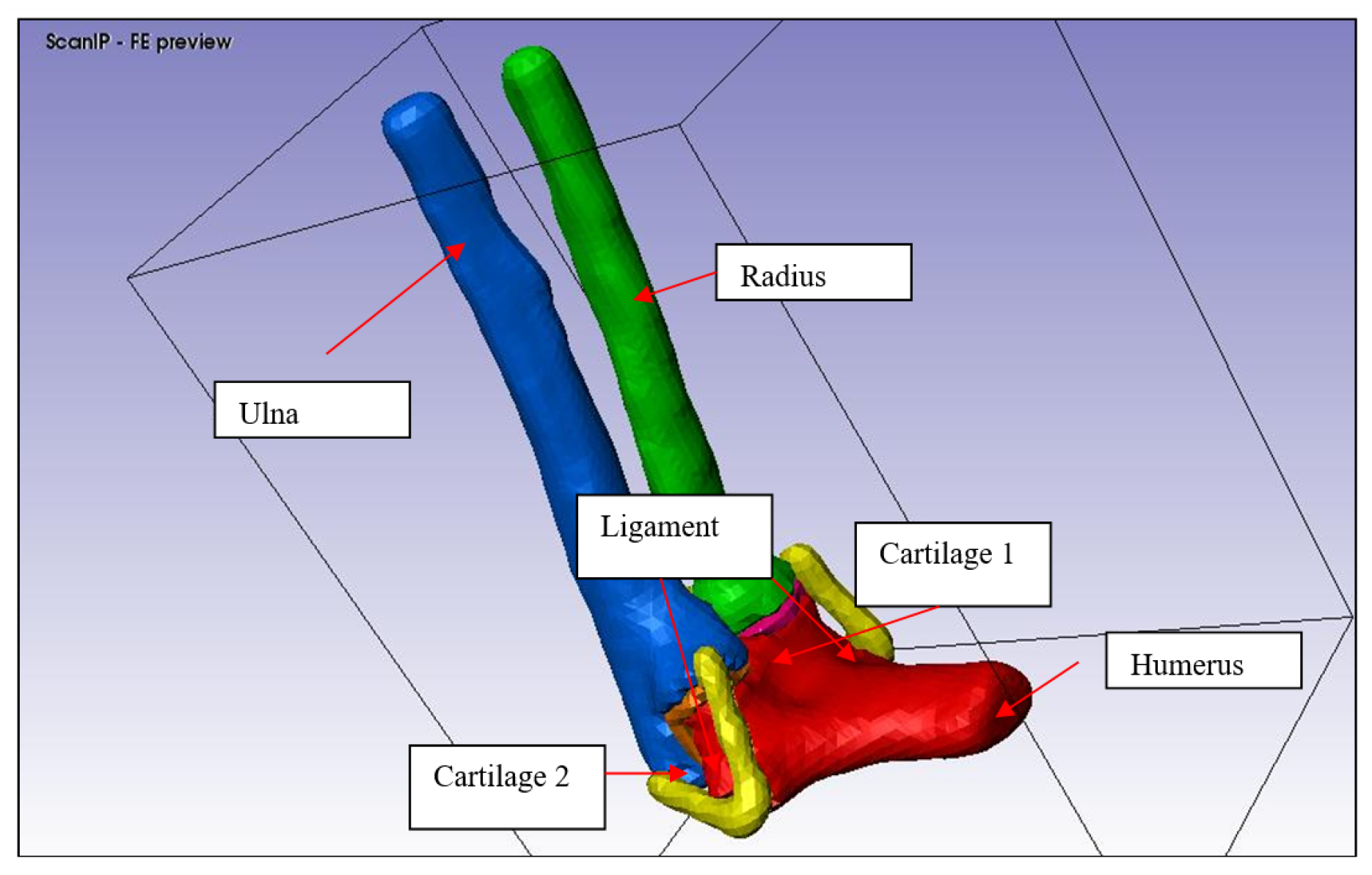

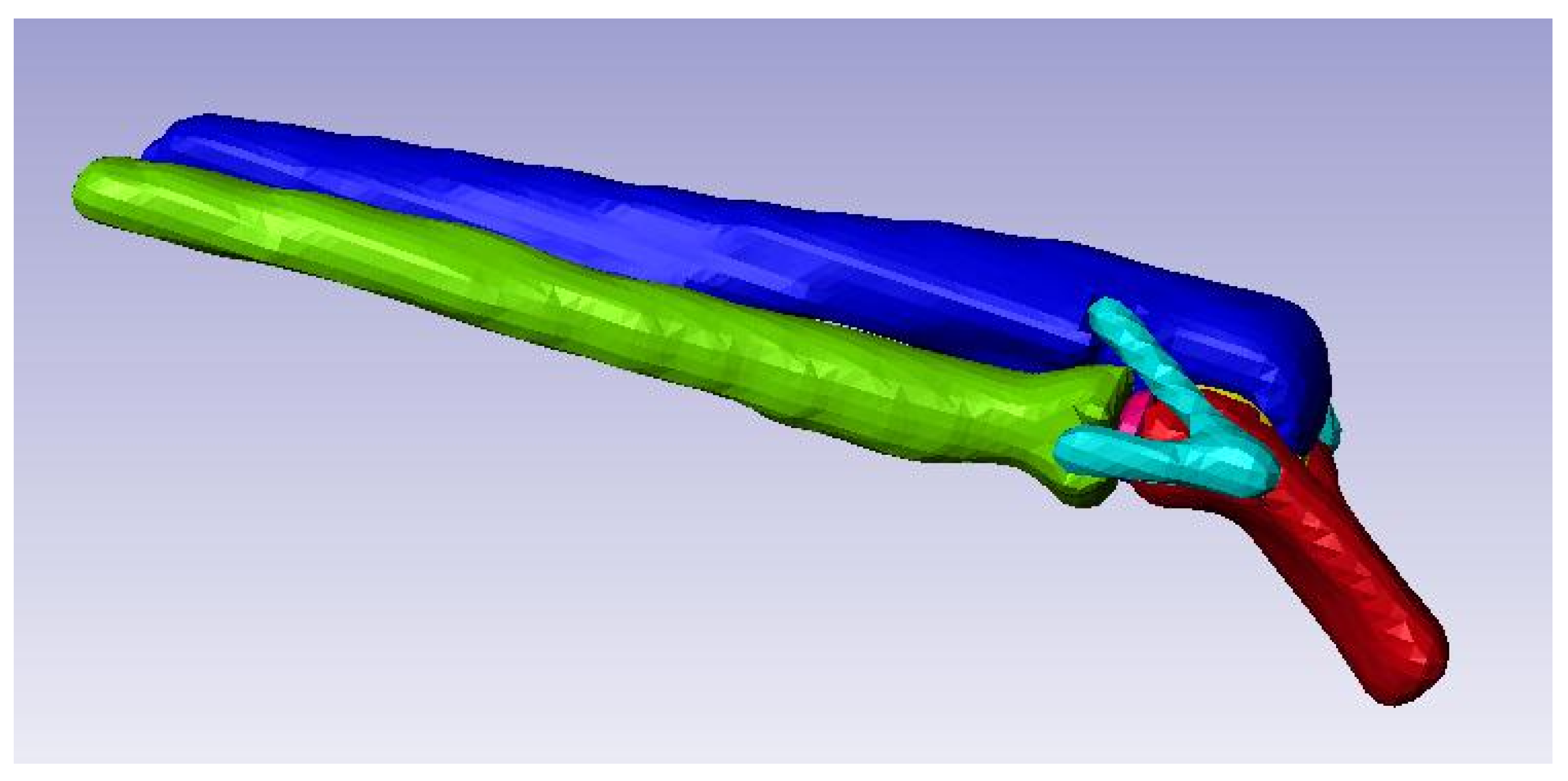

Figure 8.

3D solid model of the elbow joint.

Figure 8.

3D solid model of the elbow joint.

Figure 9.

FE generation without mesh refinement

Figure 9.

FE generation without mesh refinement

Figure 10.

FE generation with mesh refinement

Figure 10.

FE generation with mesh refinement

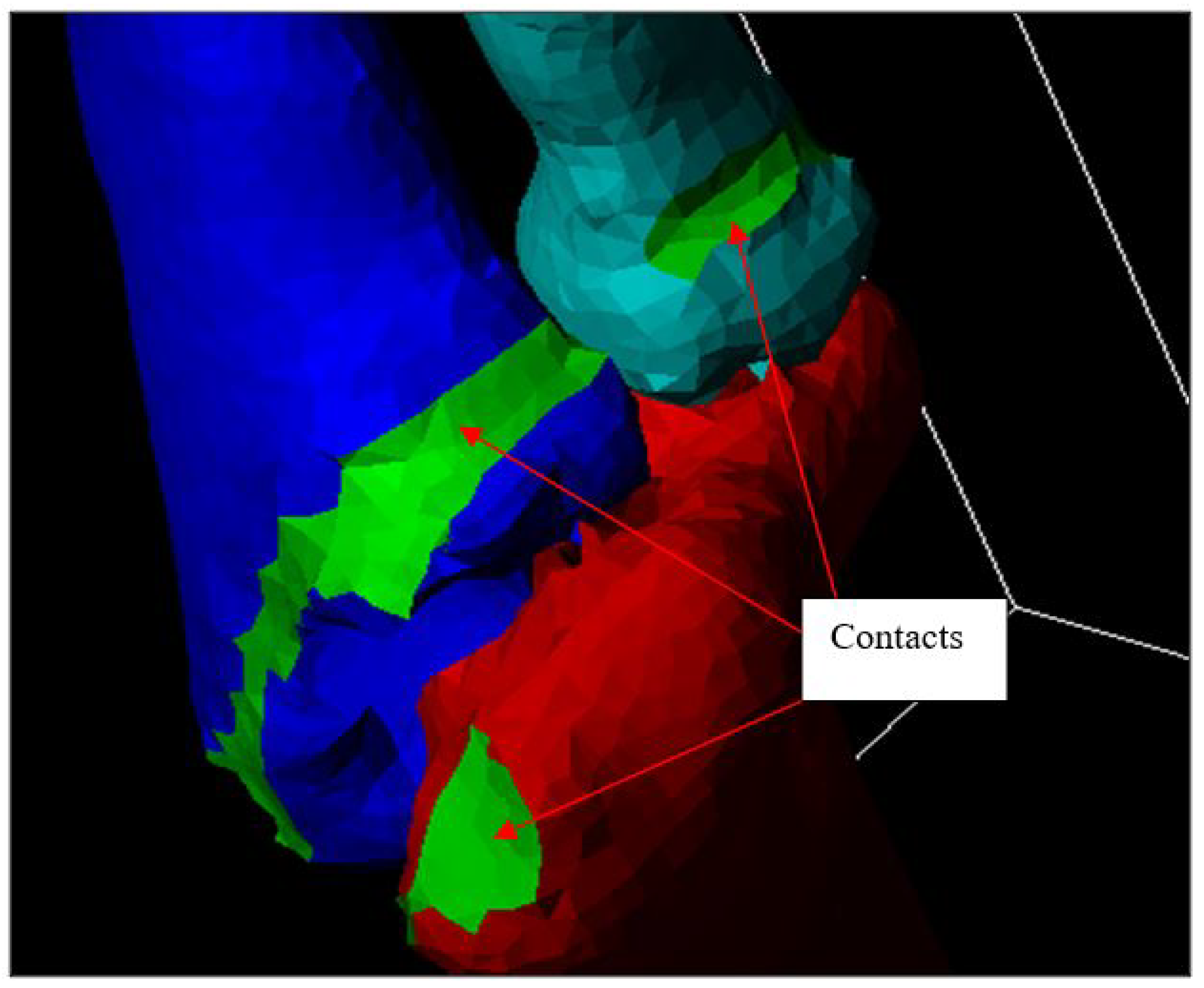

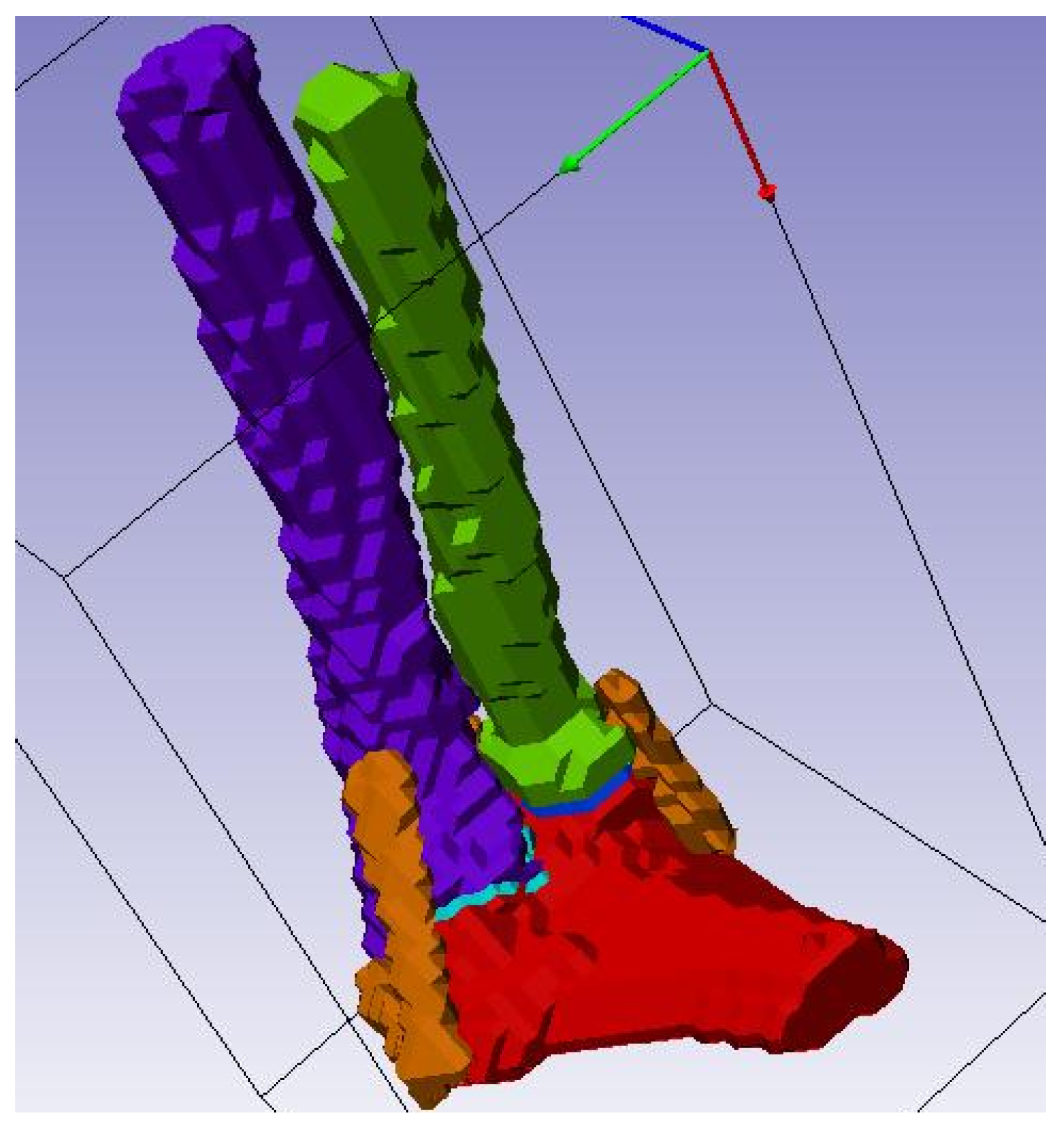

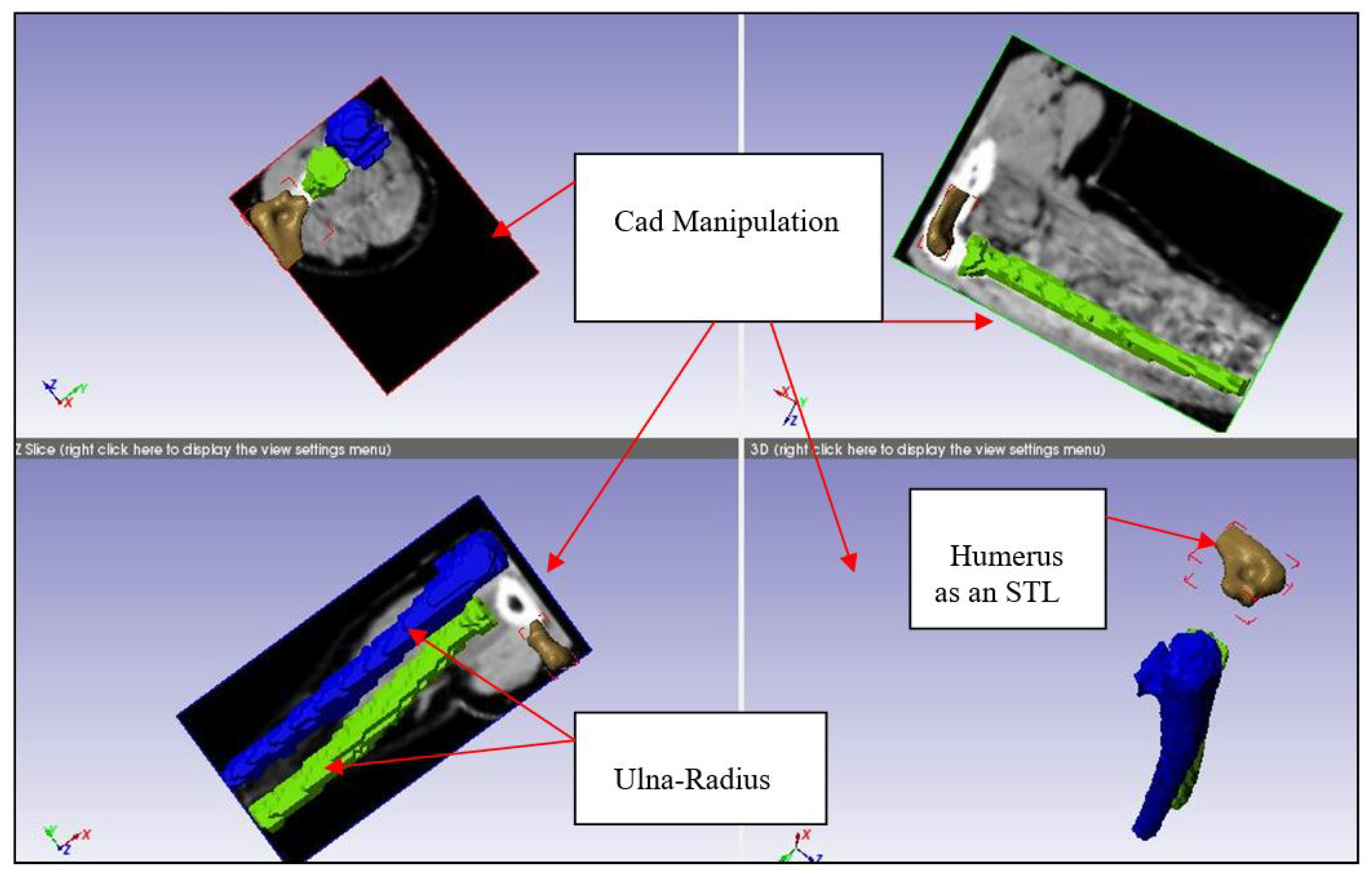

Figure 13.

Humerus and Ulna-Radius manipulation

Figure 13.

Humerus and Ulna-Radius manipulation

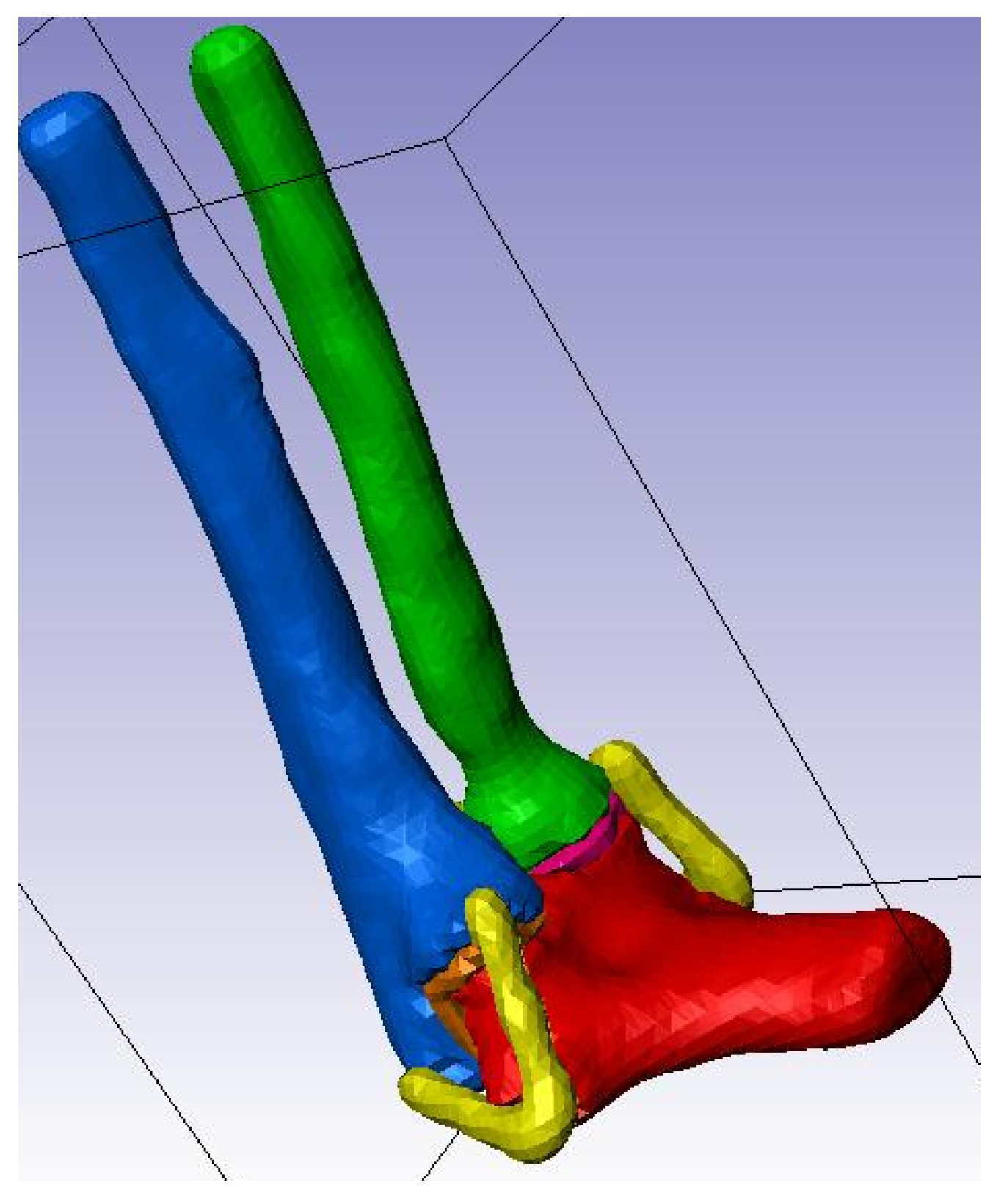

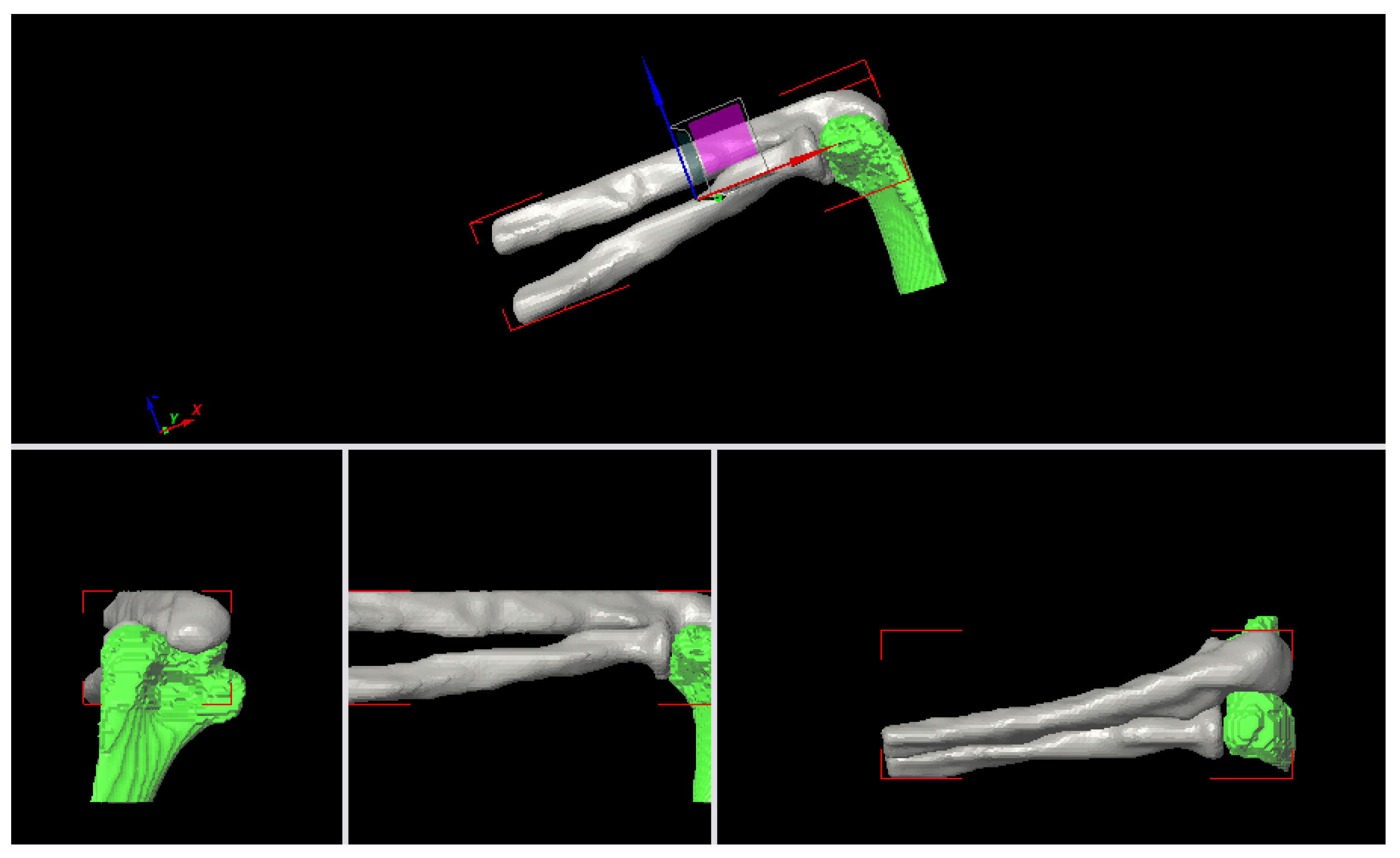

Figure 14.

Elbow joint at 90° of flexion

Figure 14.

Elbow joint at 90° of flexion

Figure 15.

Radial Collateral Ligament (RCL)

Figure 15.

Radial Collateral Ligament (RCL)

Figure 16.

Ulnar Collateral Ligament.

Figure 16.

Ulnar Collateral Ligament.

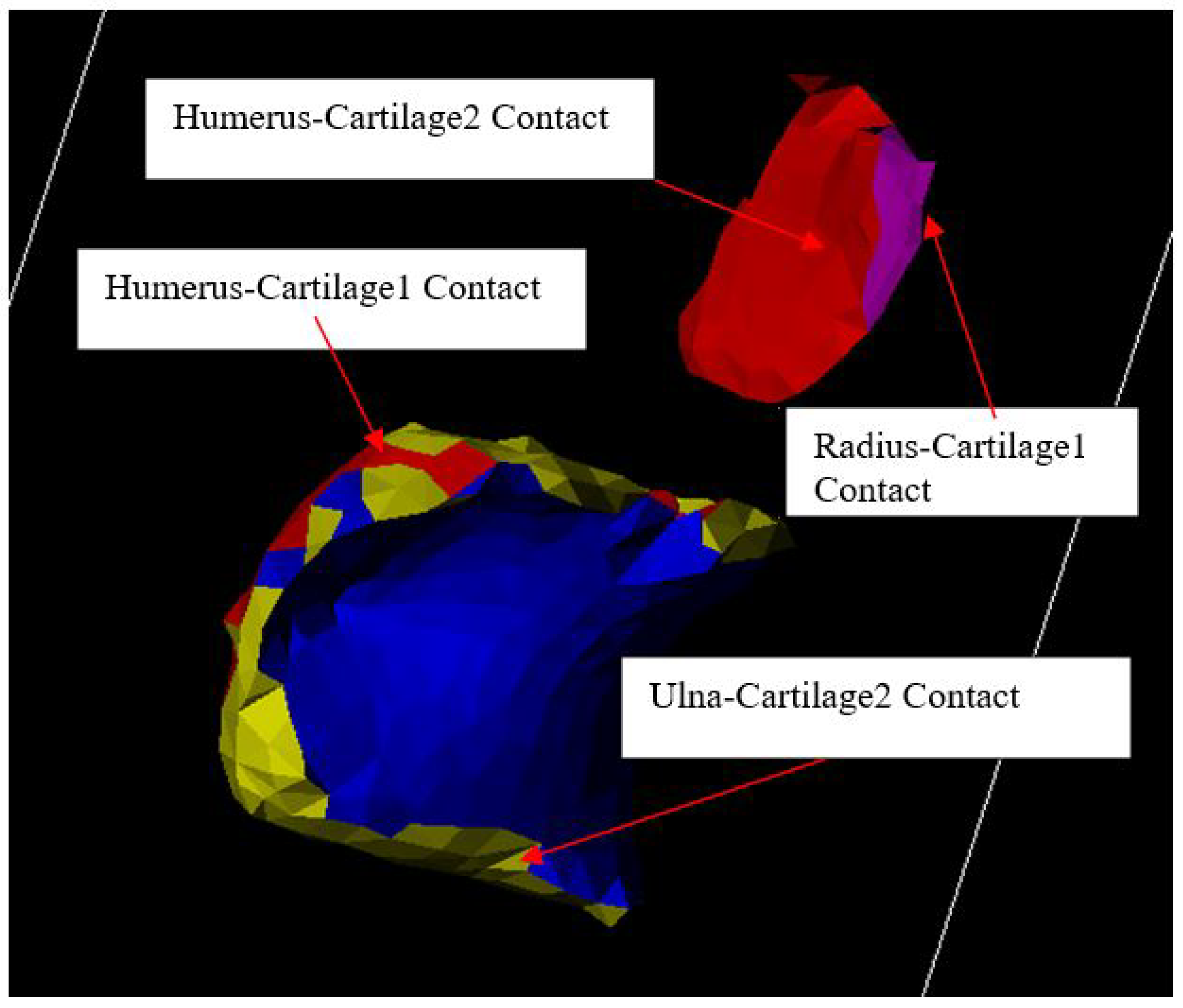

Figure 17.

Cartilage Modeling.

Figure 17.

Cartilage Modeling.

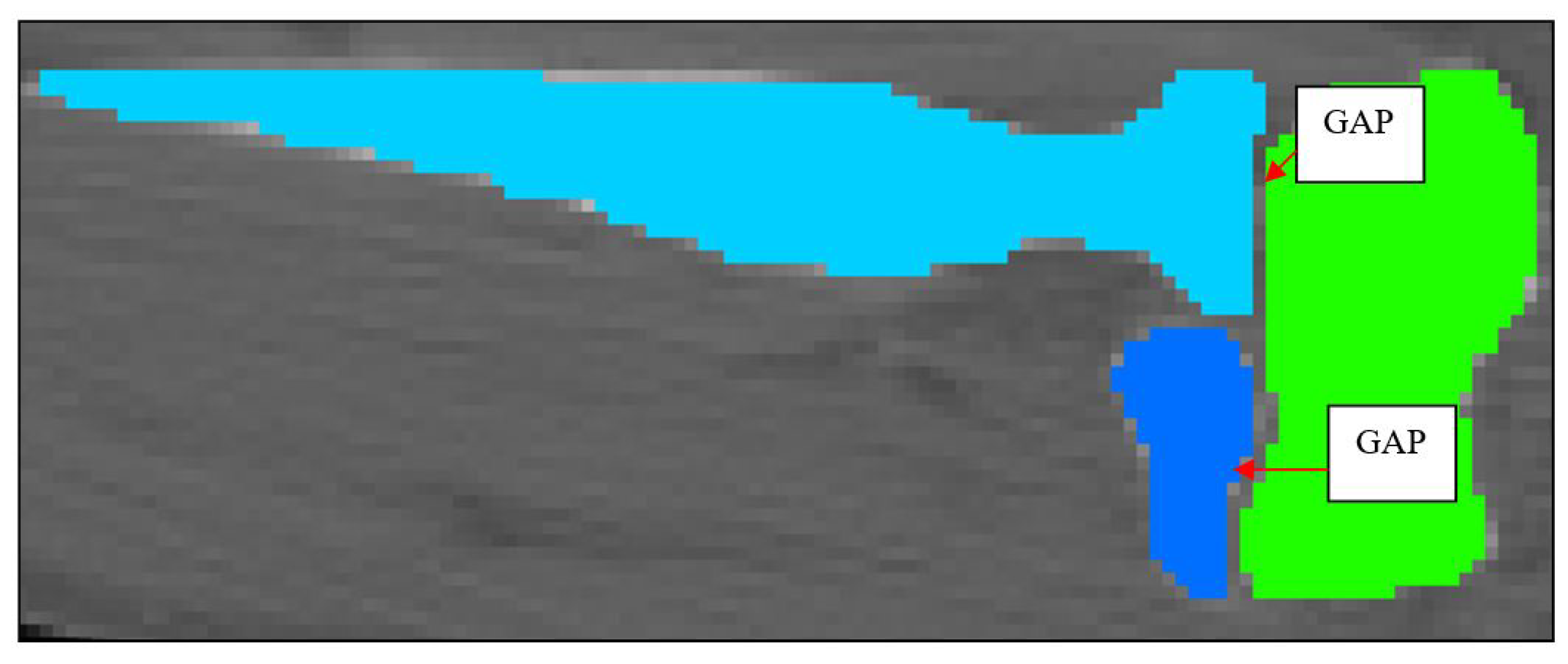

Figure 18.

2D Schematic of Cartilage 1 and Cartilage 2.

Figure 18.

2D Schematic of Cartilage 1 and Cartilage 2.

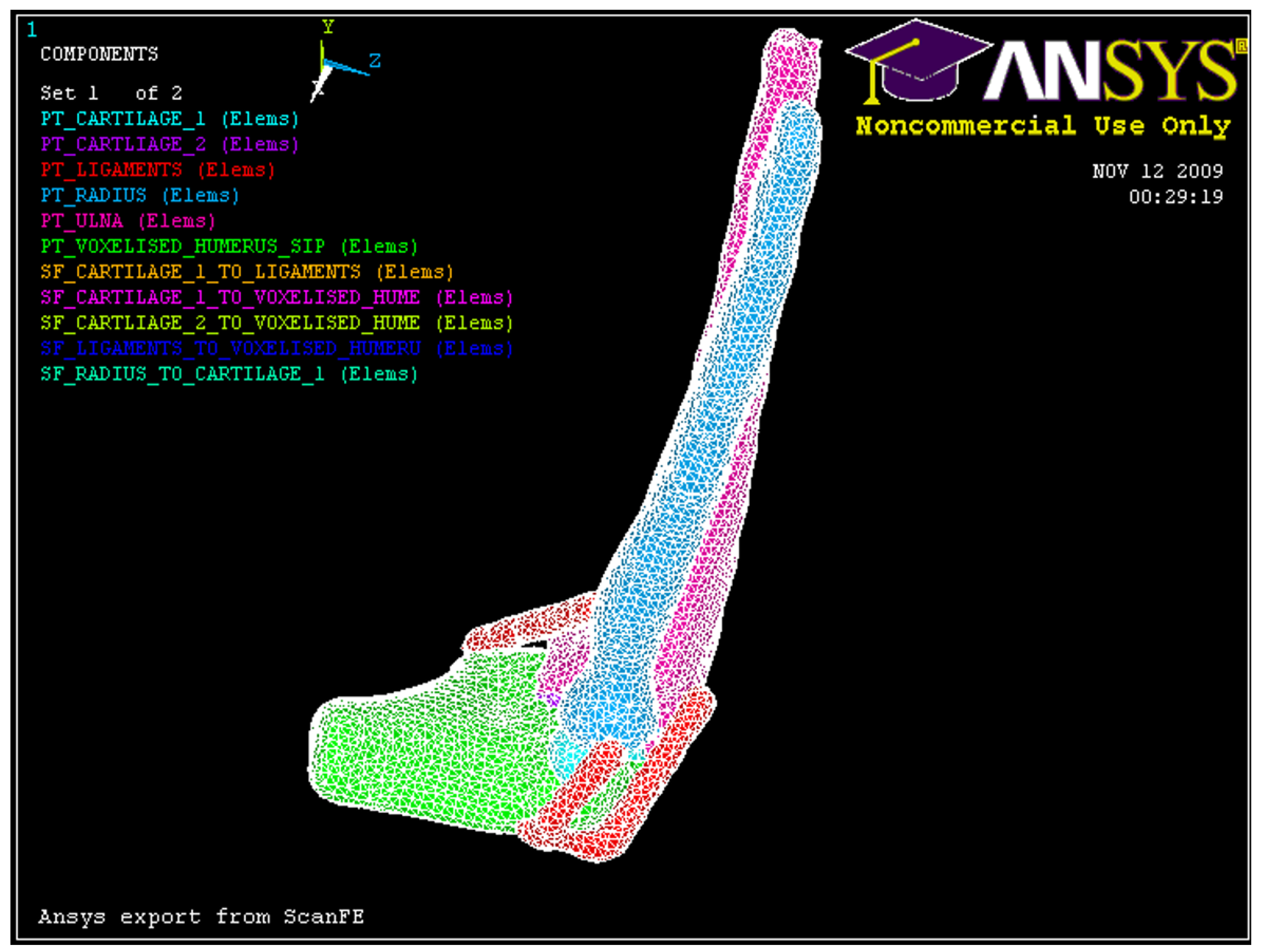

Figure 19.

3D FE model developed in Simpleware.

Figure 19.

3D FE model developed in Simpleware.

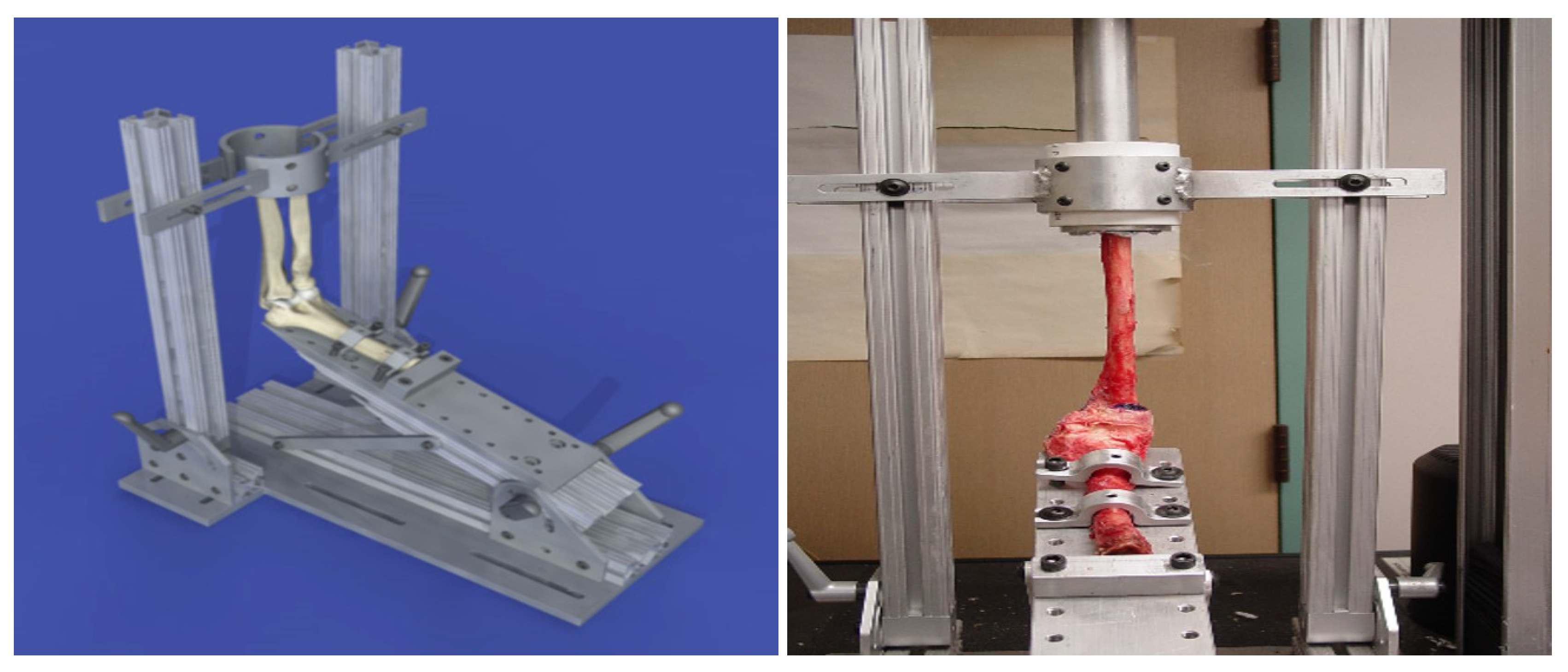

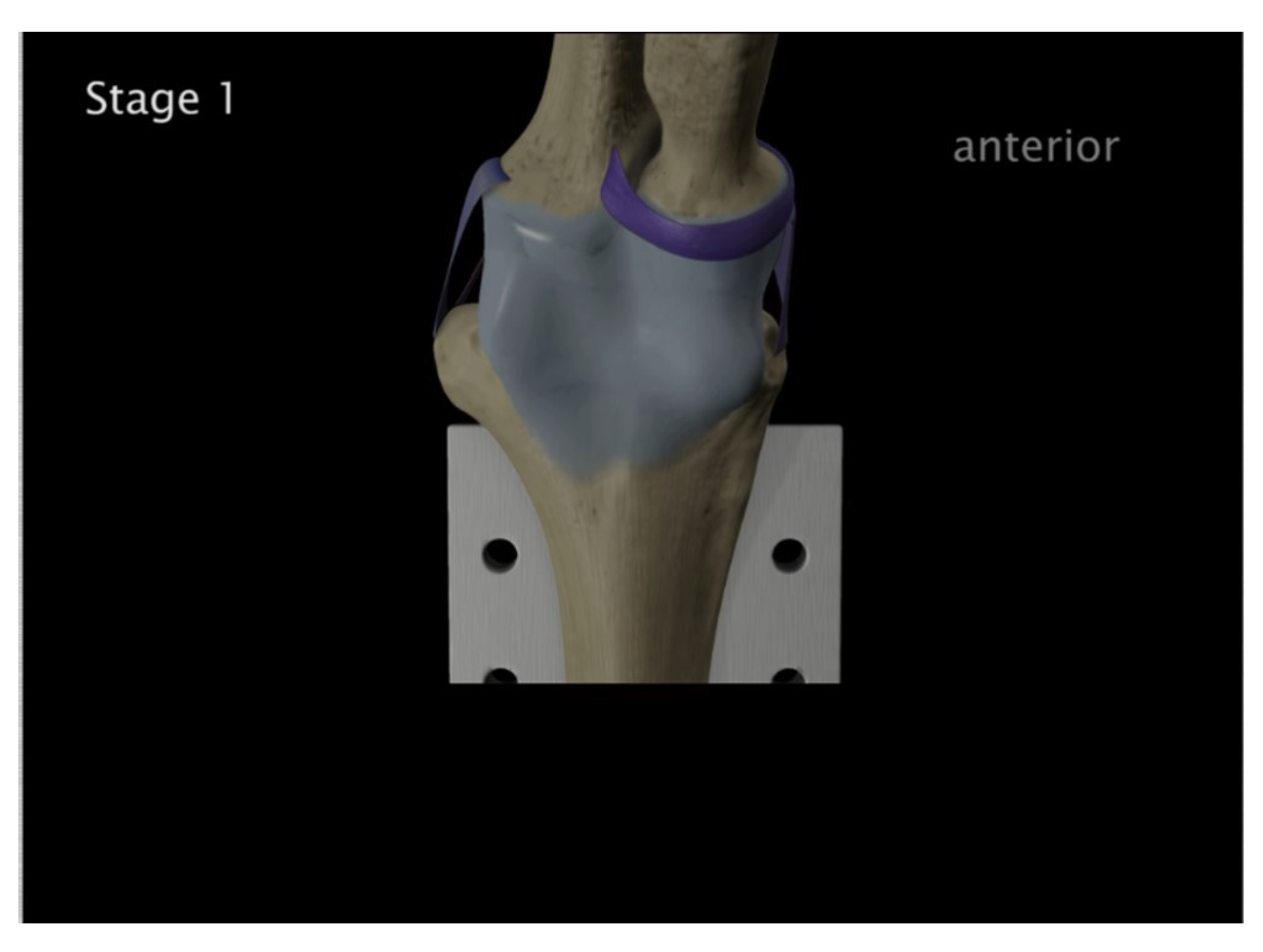

Figure 20.

Loading apparatus used with human cadaver arms [

1]

Figure 20.

Loading apparatus used with human cadaver arms [

1]

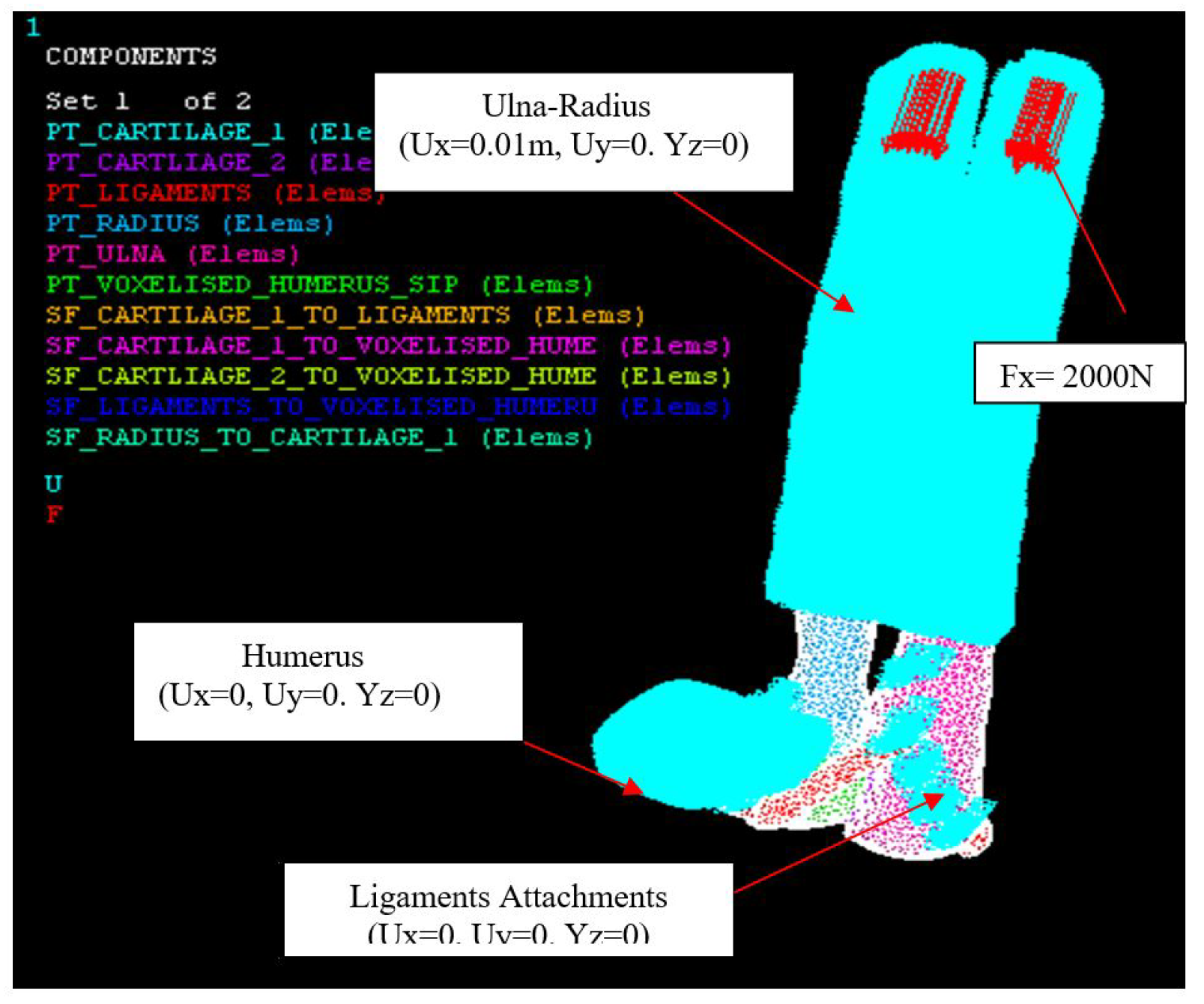

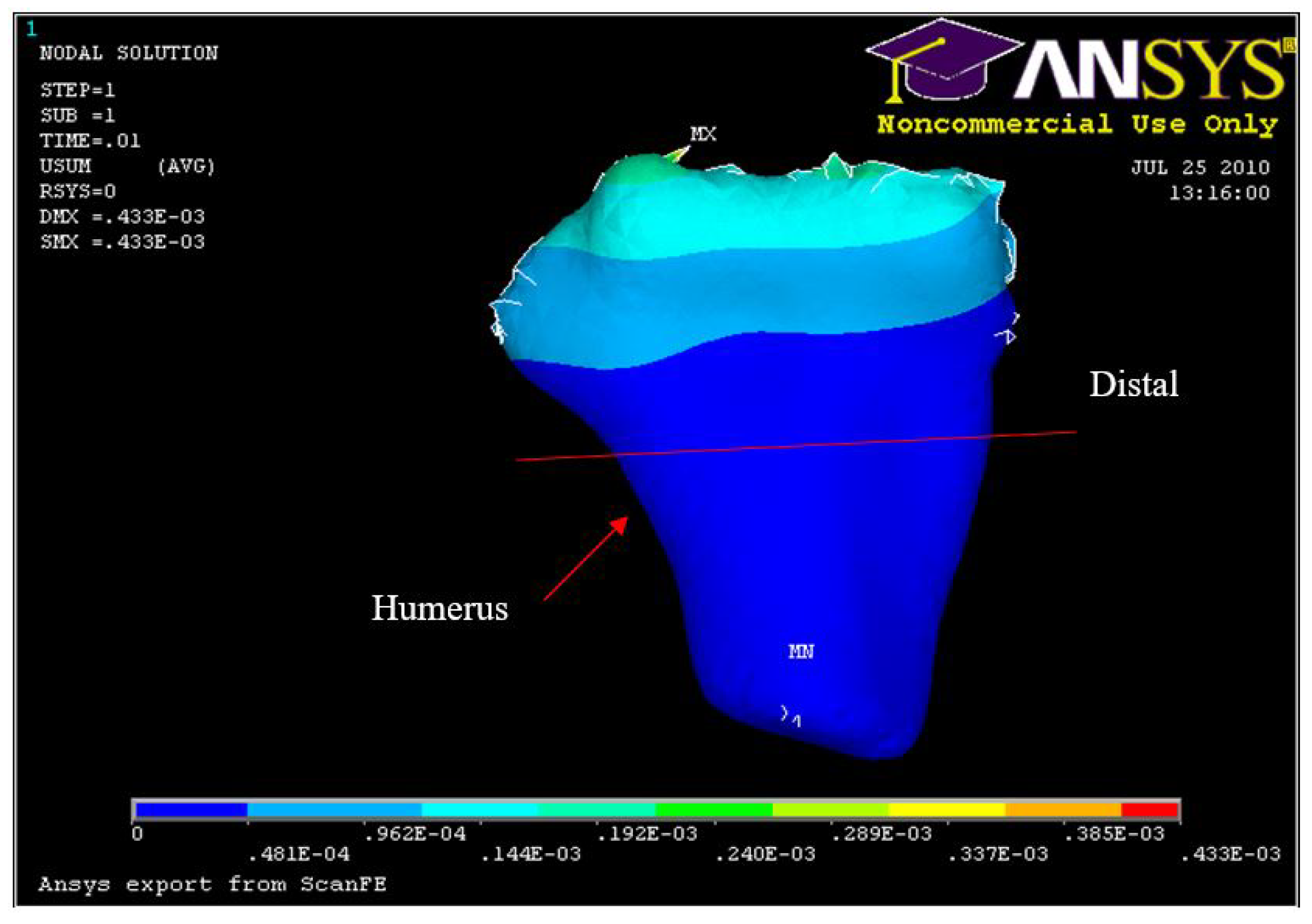

Figure 21.

Axial loading, Fx = 2000 N, Humerus (0.01 m, 0, 0), Ulna-Radius (0, 0, 0).

Figure 21.

Axial loading, Fx = 2000 N, Humerus (0.01 m, 0, 0), Ulna-Radius (0, 0, 0).

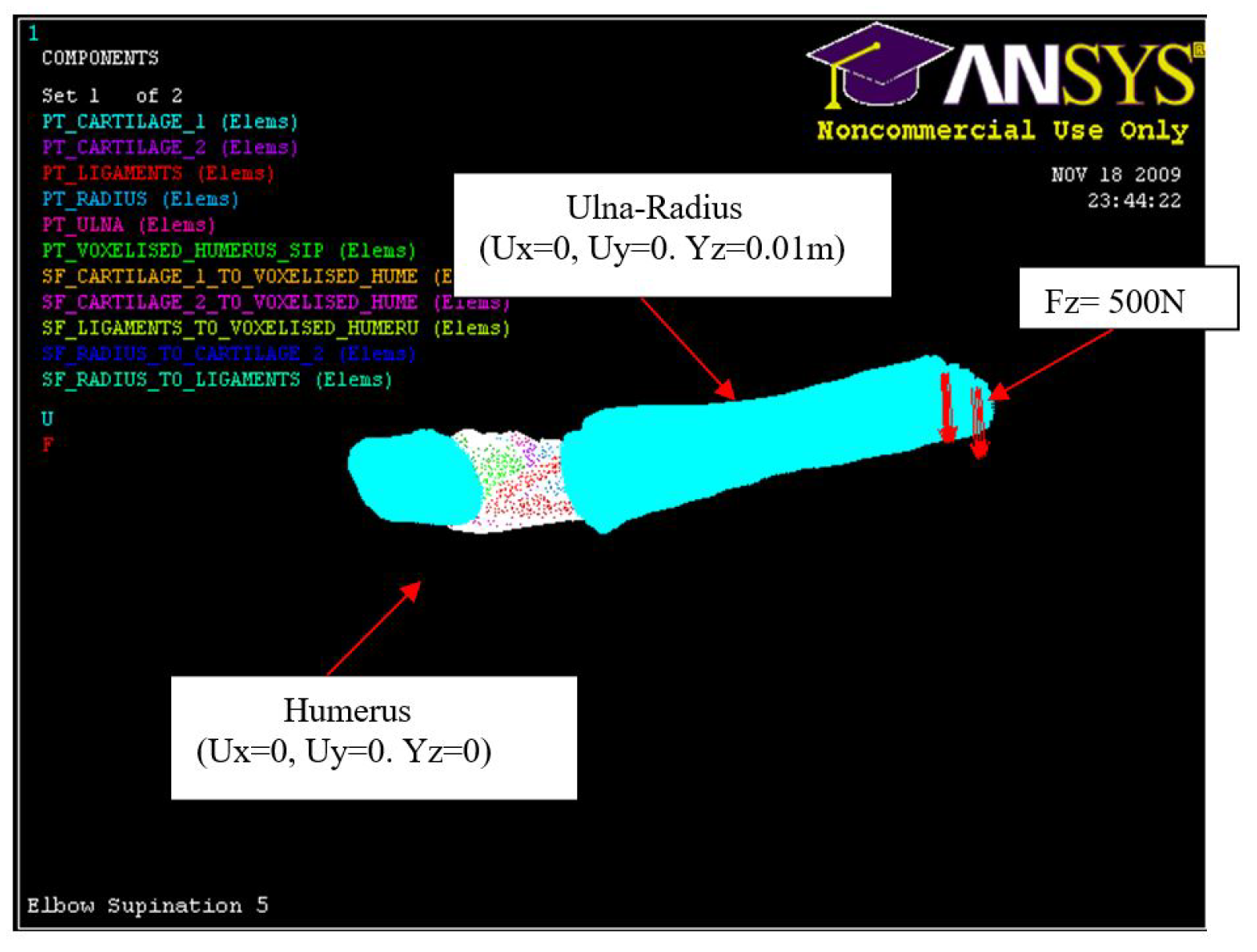

Figure 22.

Hyper-extension loading, Fz = 500 N, Humerus (0, 0, 0), Ulna-Radius (0, 0, 0.01 m).

Figure 22.

Hyper-extension loading, Fz = 500 N, Humerus (0, 0, 0), Ulna-Radius (0, 0, 0.01 m).

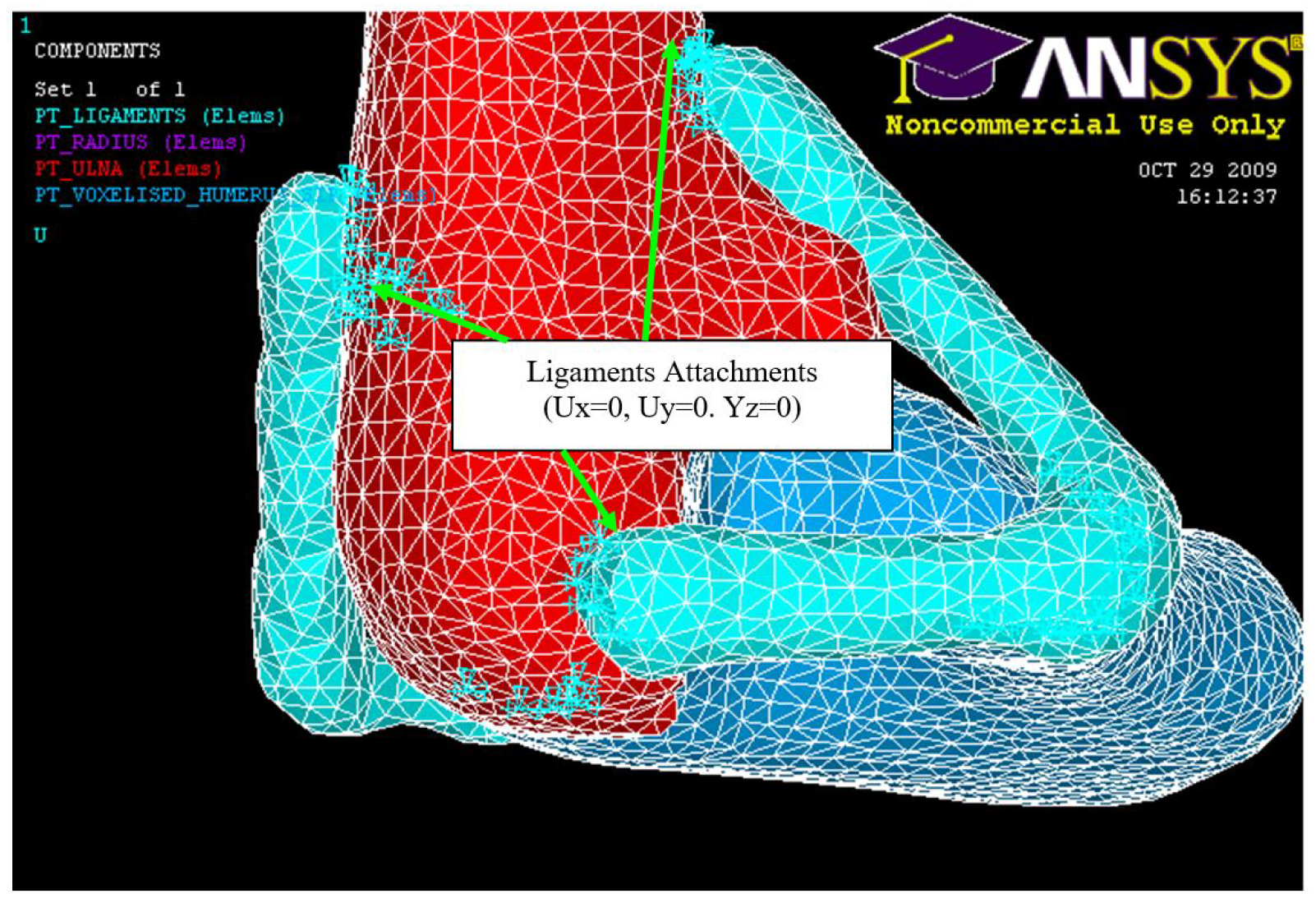

Figure 23.

Ligament attachments (0, 0, 0).

Figure 23.

Ligament attachments (0, 0, 0).

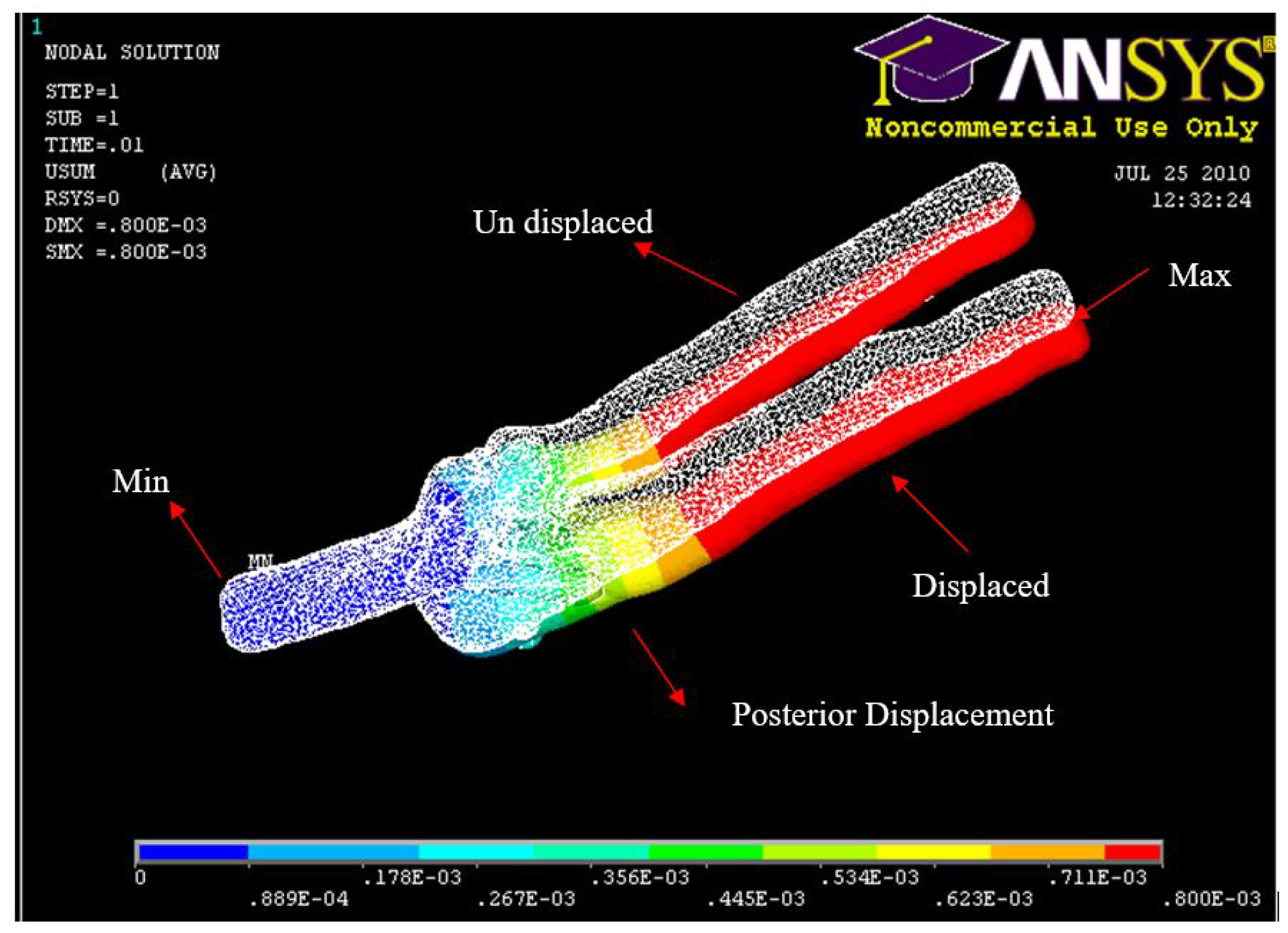

Figure 24.

FE: Posterior Displacement of ulna-radius with 5° of flexion and in pronation

Figure 24.

FE: Posterior Displacement of ulna-radius with 5° of flexion and in pronation

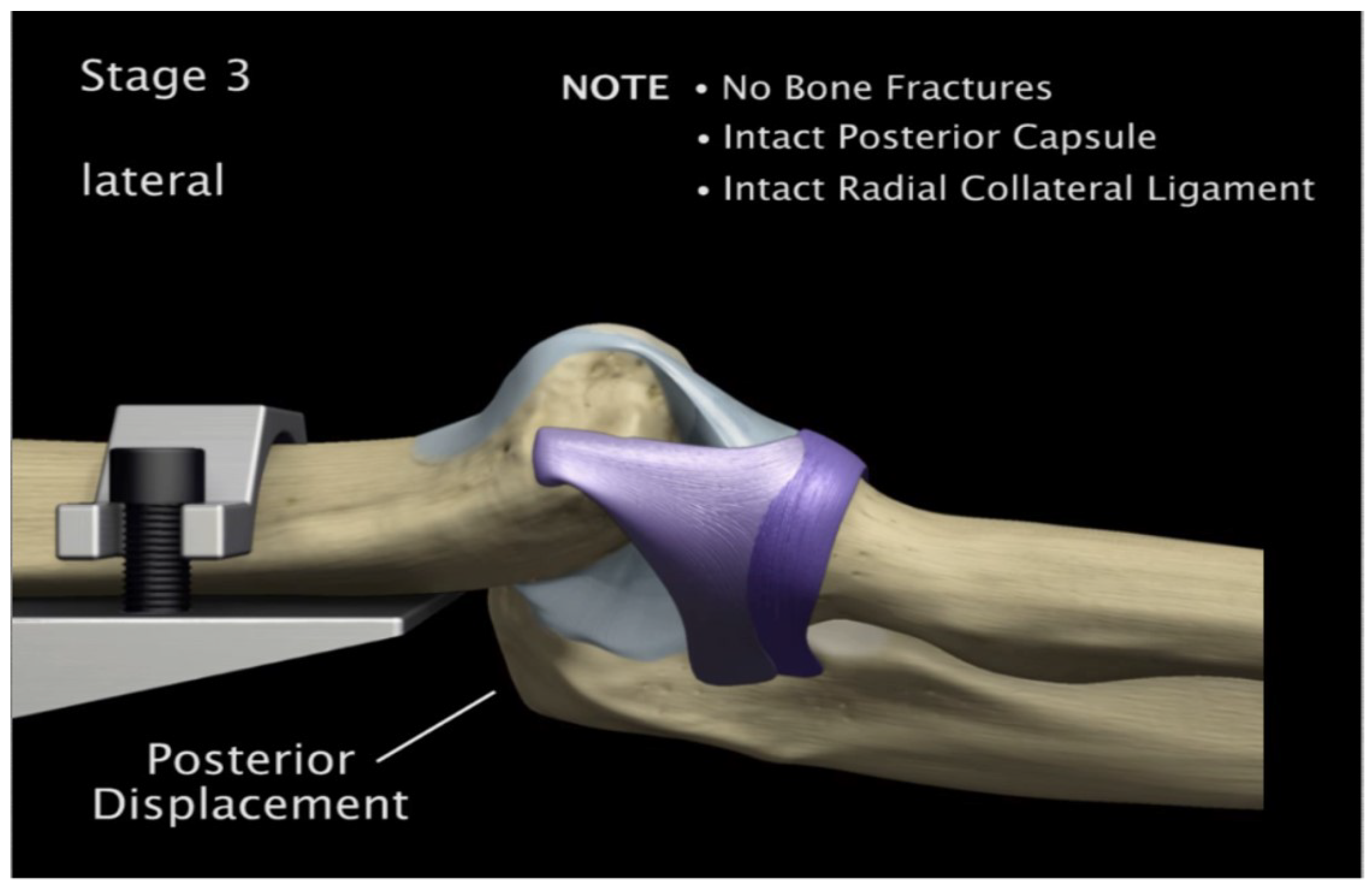

Figure 25.

Experiment: Posterior Displacement of ulna-radius with 5° of flexion and in pronation

Figure 25.

Experiment: Posterior Displacement of ulna-radius with 5° of flexion and in pronation

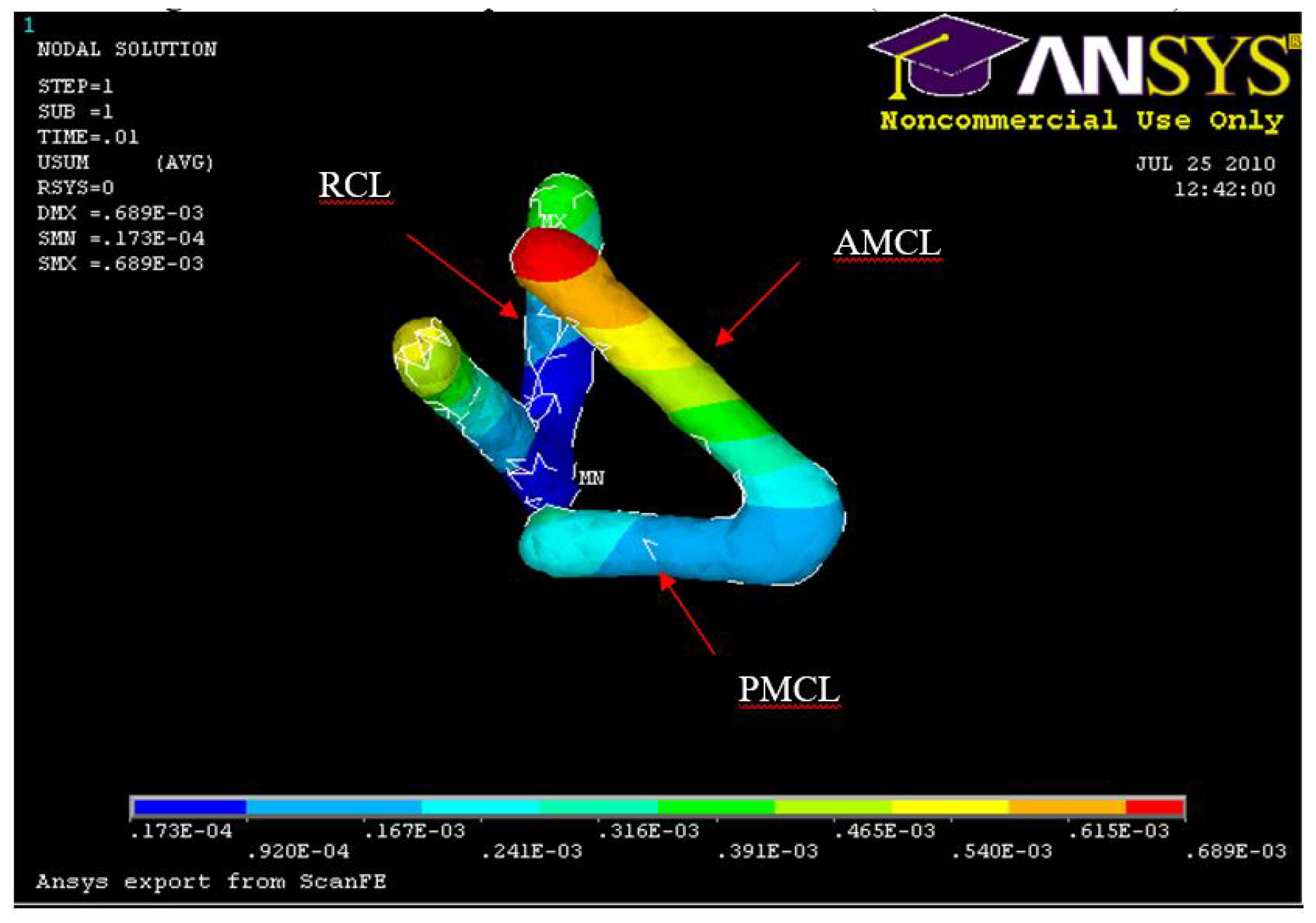

Figure 26.

FE: Displacement of AMCL, PMCL and RCL

Figure 26.

FE: Displacement of AMCL, PMCL and RCL

Figure 27.

Experiment: Anterior medial collateral and anterior capsule complete tear

Figure 27.

Experiment: Anterior medial collateral and anterior capsule complete tear

Figure 28.

FE: Displacement of humerus 5° flexion and in pronation

Figure 28.

FE: Displacement of humerus 5° flexion and in pronation

Figure 29.

Experiment Min Distal Humerus Displacement 5° flexion and in pronation

Figure 29.

Experiment Min Distal Humerus Displacement 5° flexion and in pronation

Figure 30.

Anterior capsule tearing at the mid-portion 5° flexion and in pronation

Figure 30.

Anterior capsule tearing at the mid-portion 5° flexion and in pronation

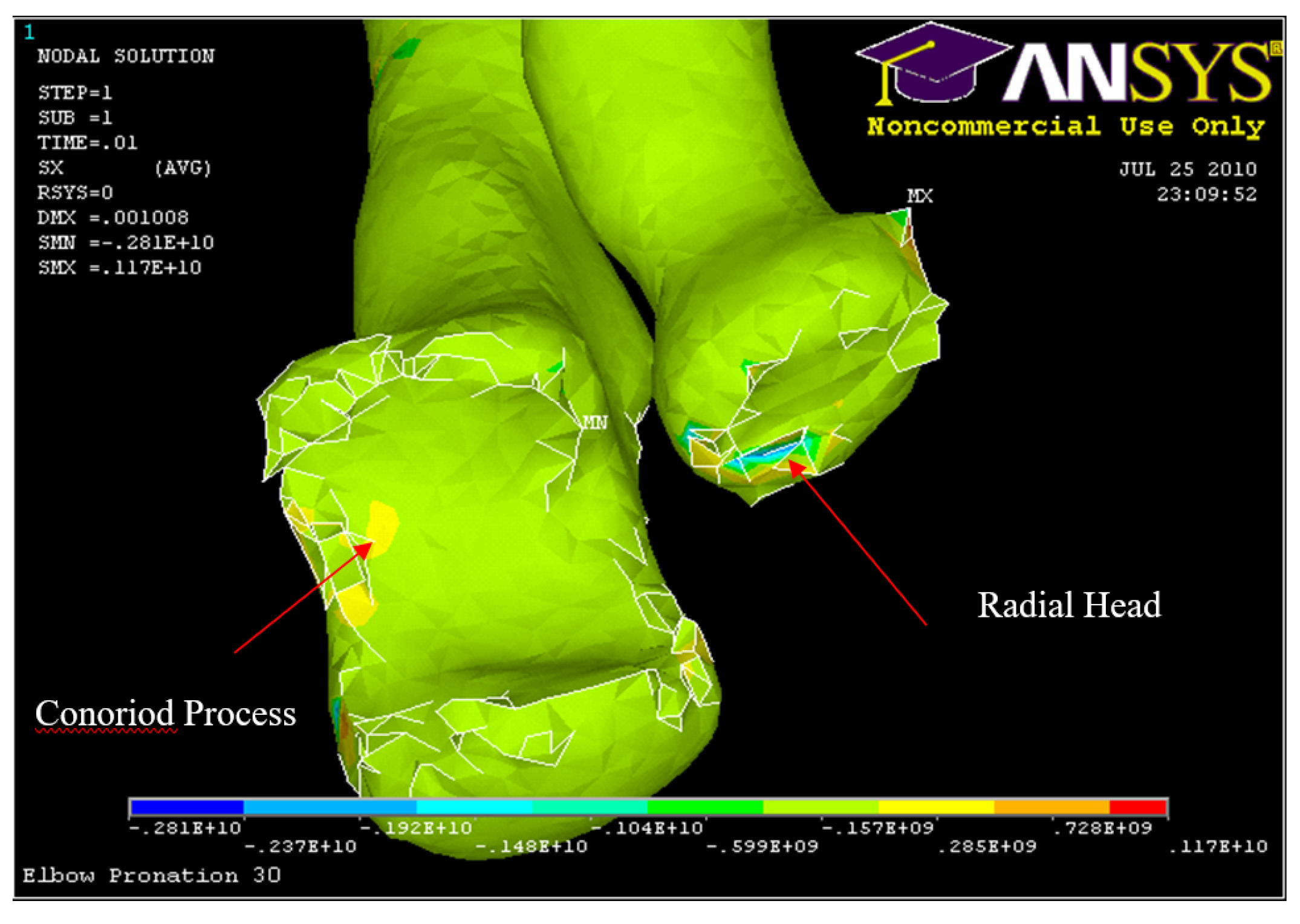

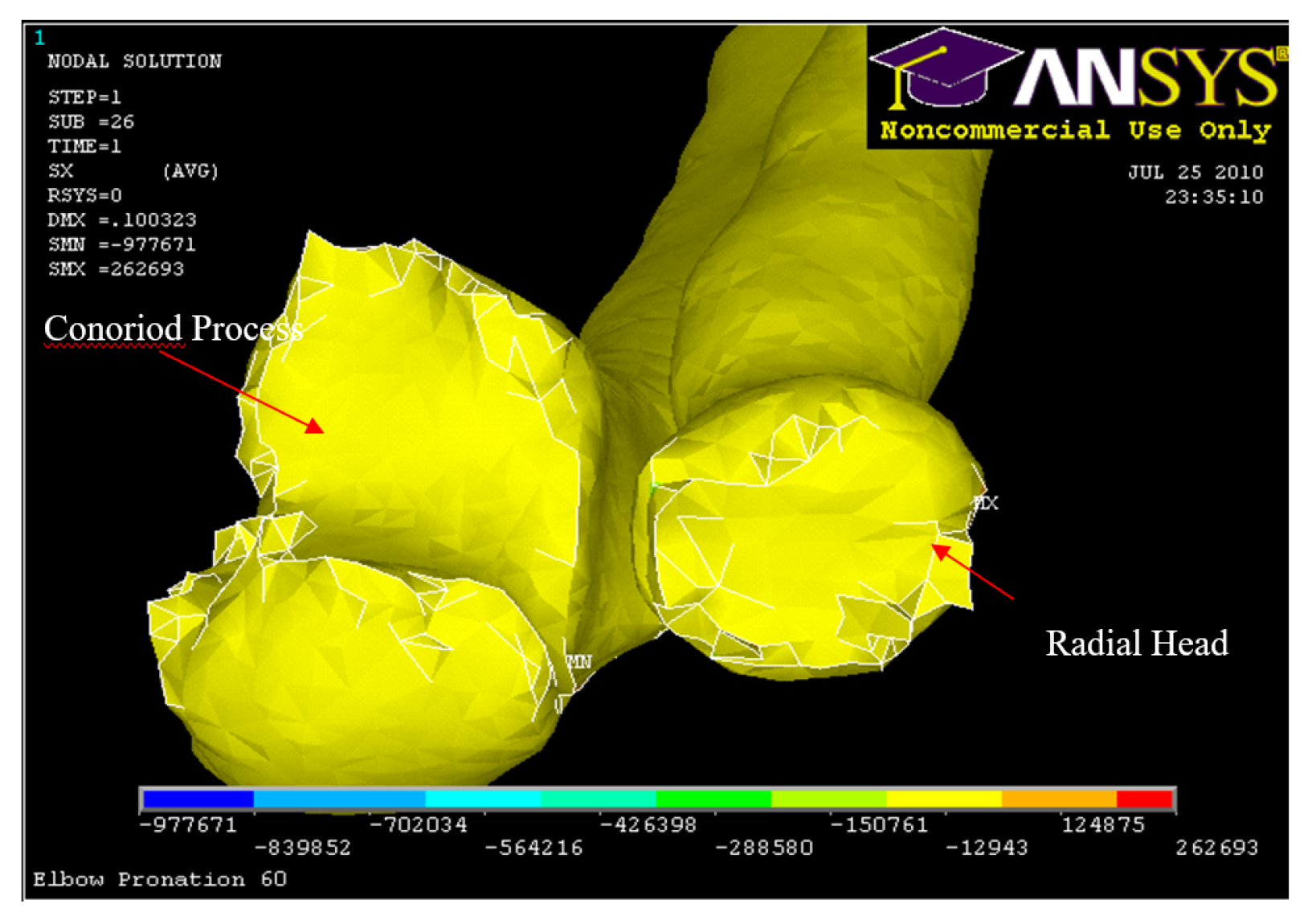

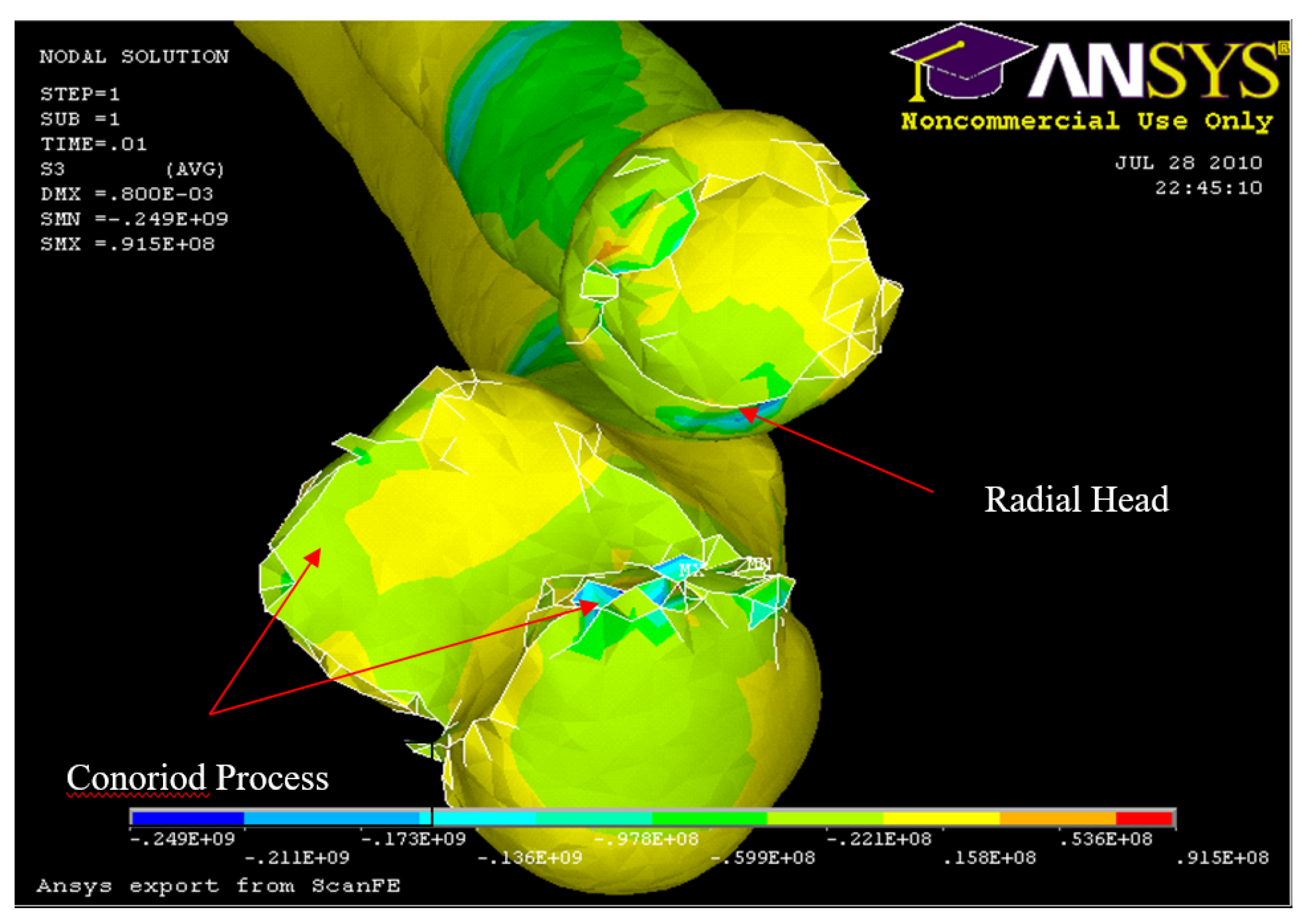

Figure 31.

FE: Nodal Stress at Conoriod Process and Radial Head 5° flexion and in pronation

Figure 31.

FE: Nodal Stress at Conoriod Process and Radial Head 5° flexion and in pronation

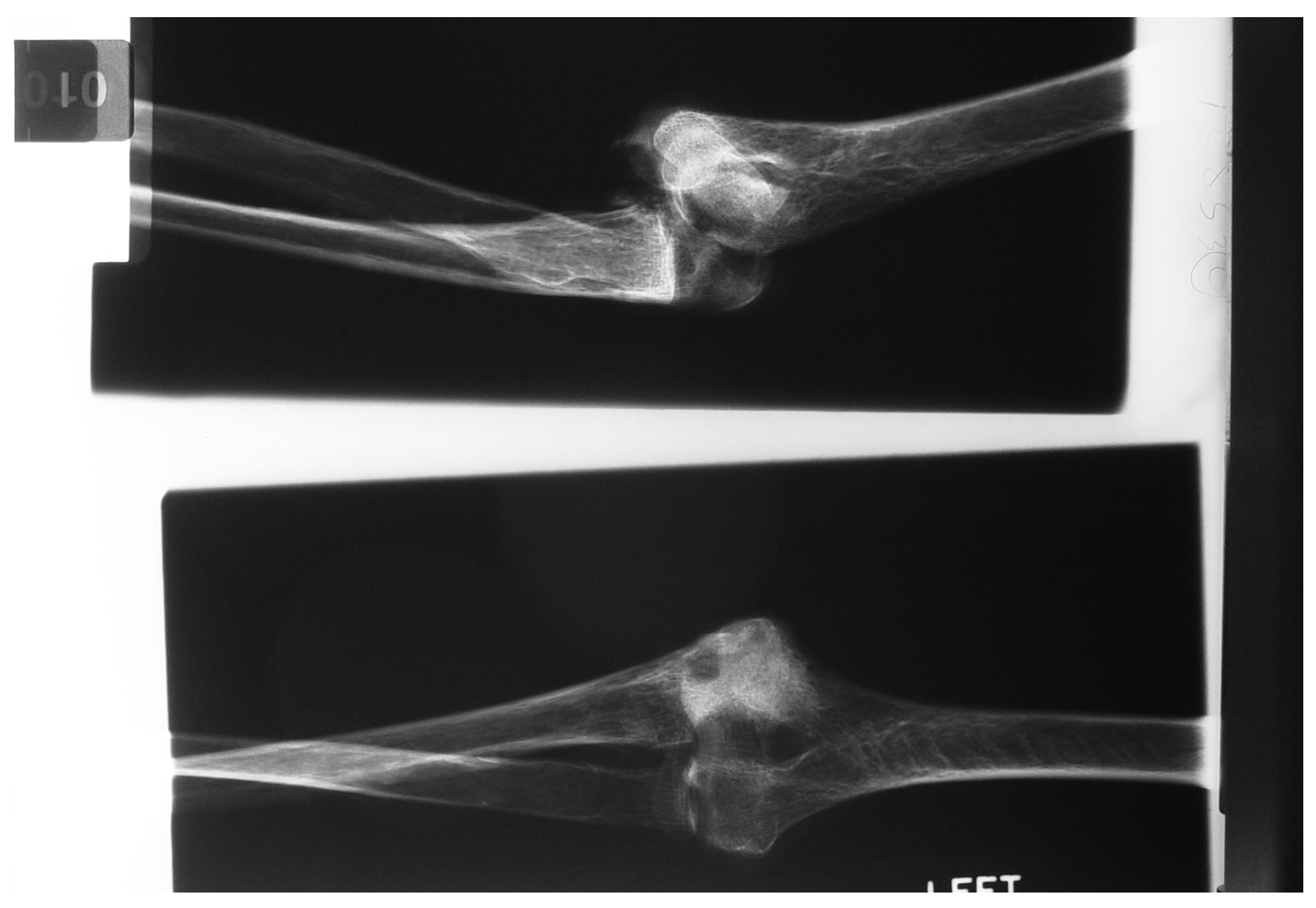

Figure 32.

Experiment: X-ray image of Radial and Conoriod Process Fracture 5° flexion and in pronation

Figure 32.

Experiment: X-ray image of Radial and Conoriod Process Fracture 5° flexion and in pronation

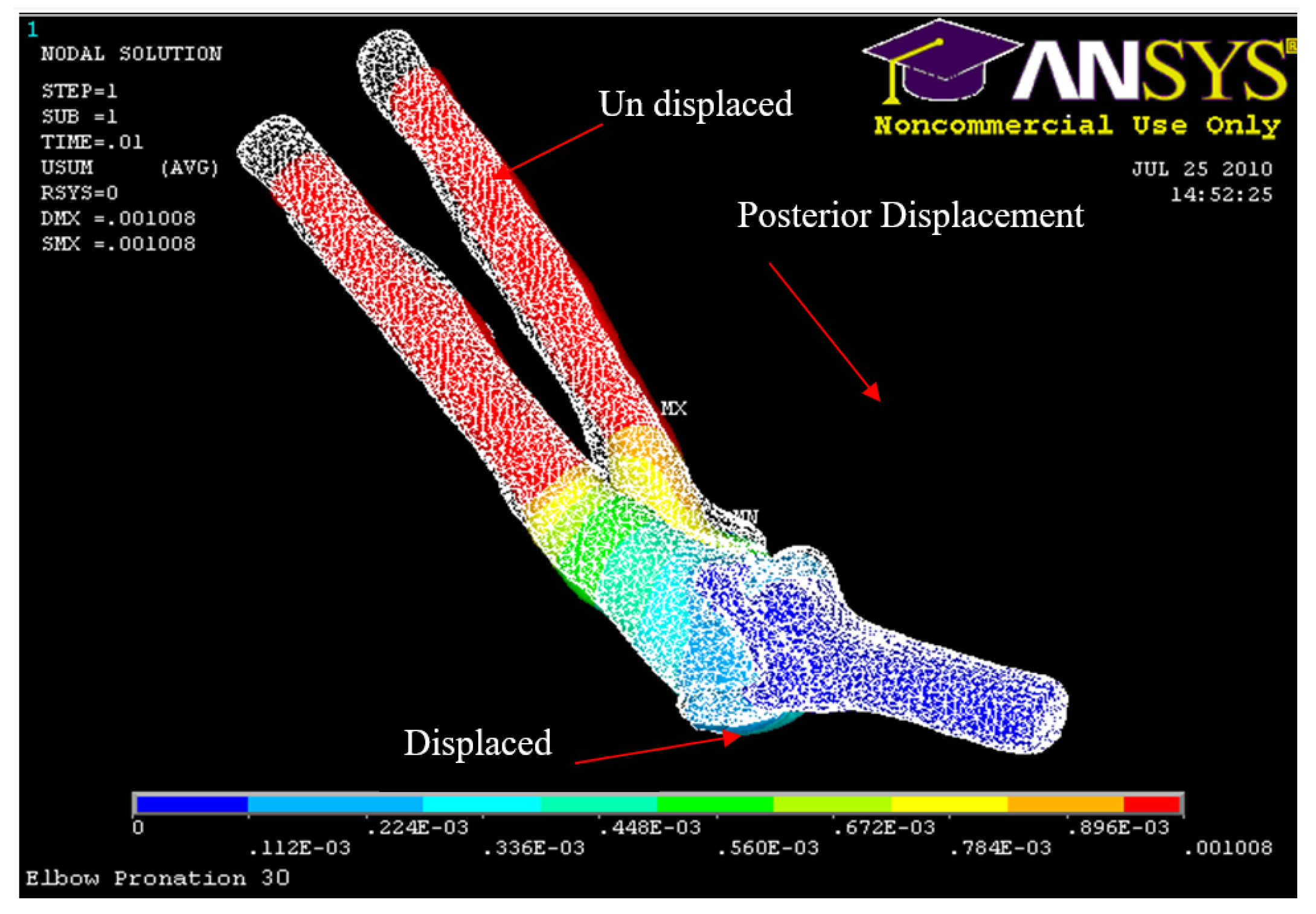

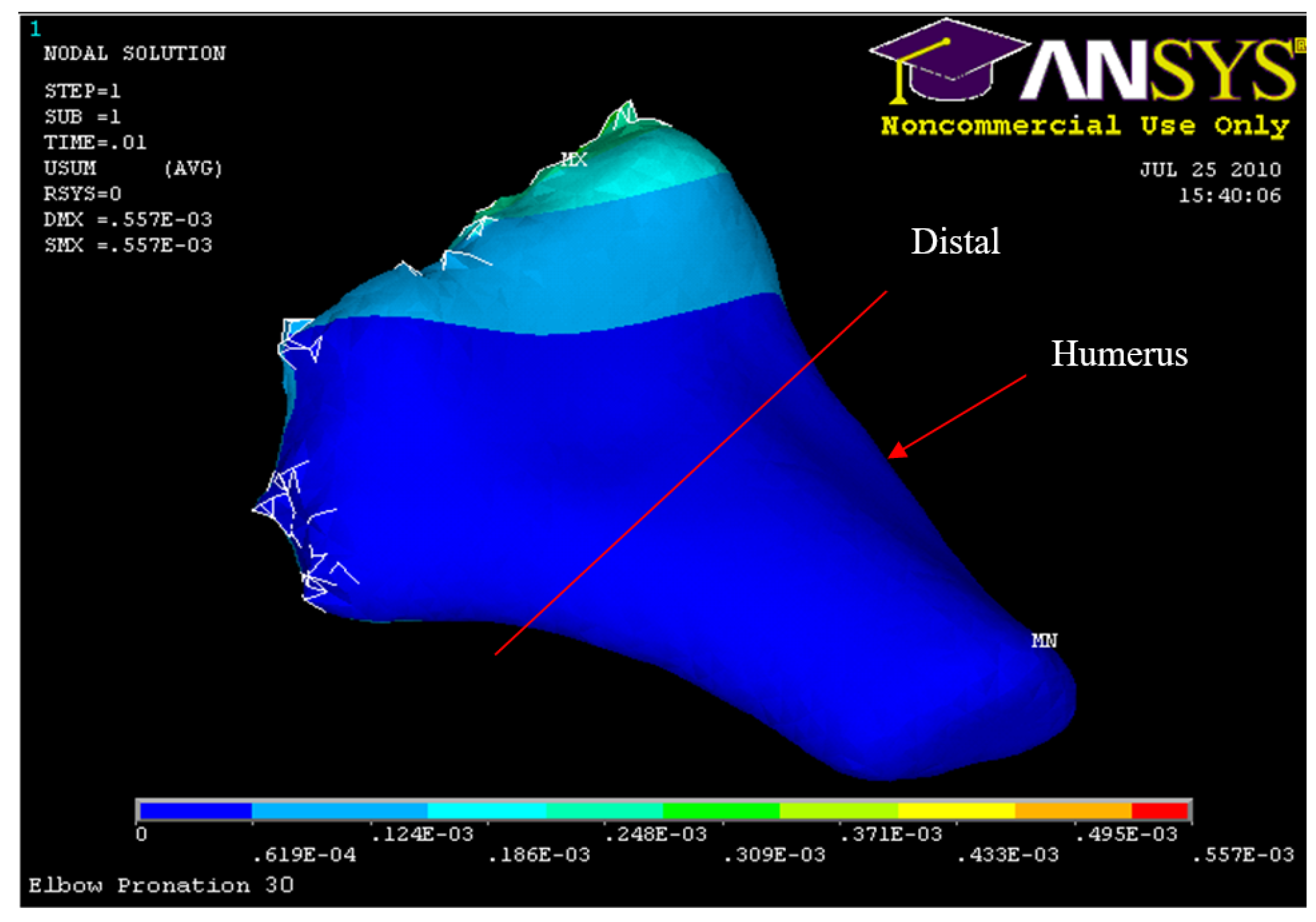

Figure 33.

Posterior Displacement 30° flexion and in pronation

Figure 33.

Posterior Displacement 30° flexion and in pronation

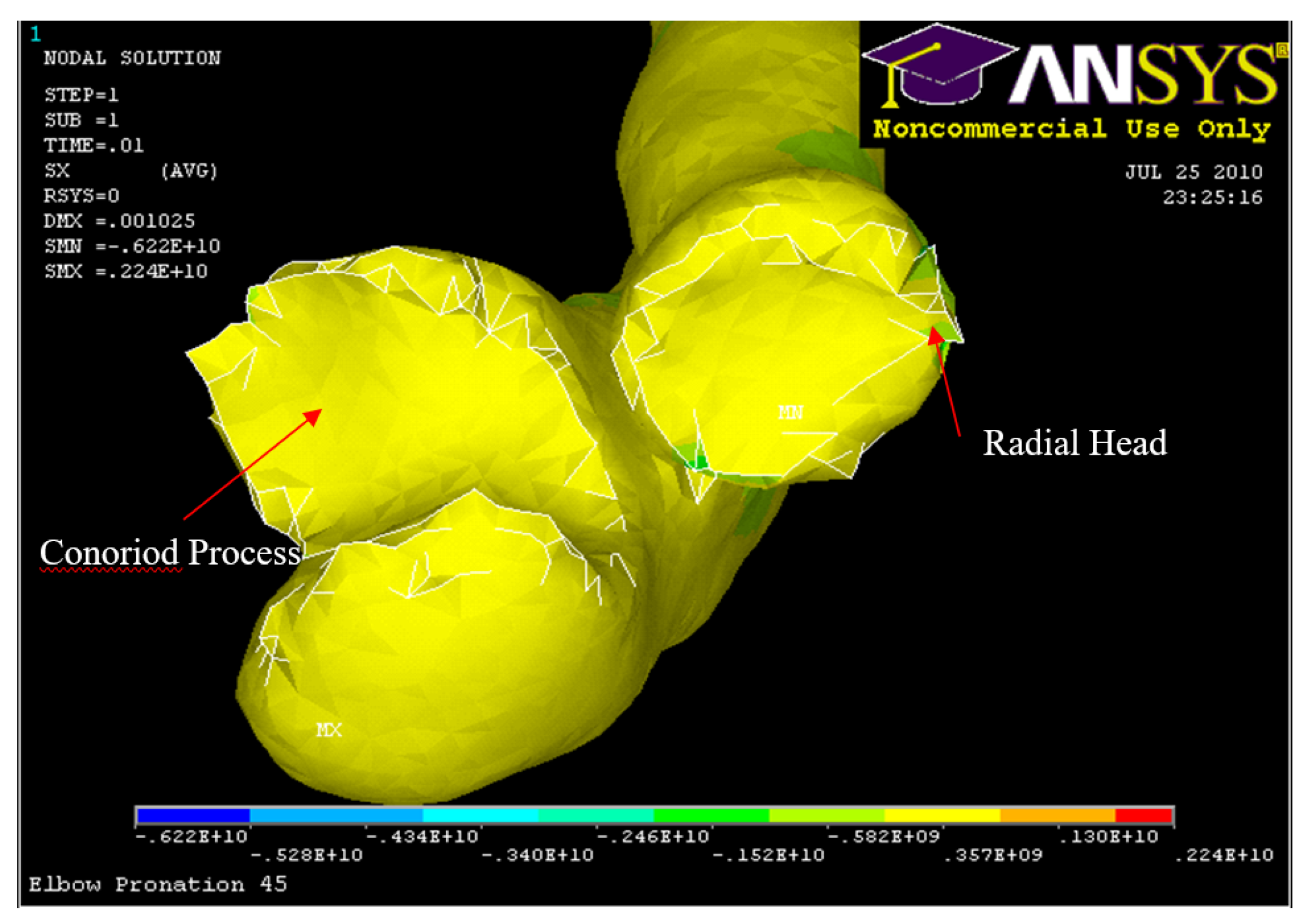

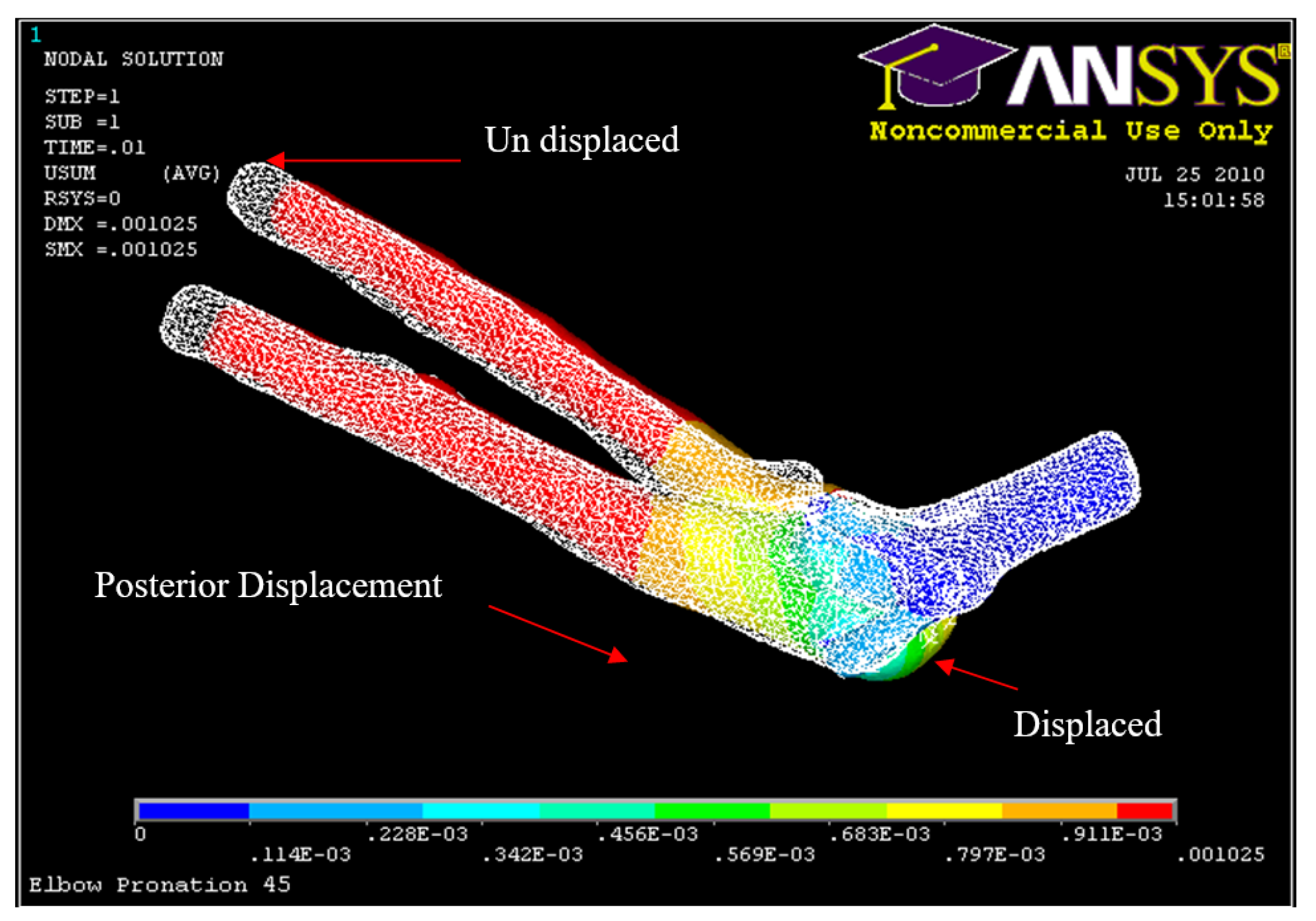

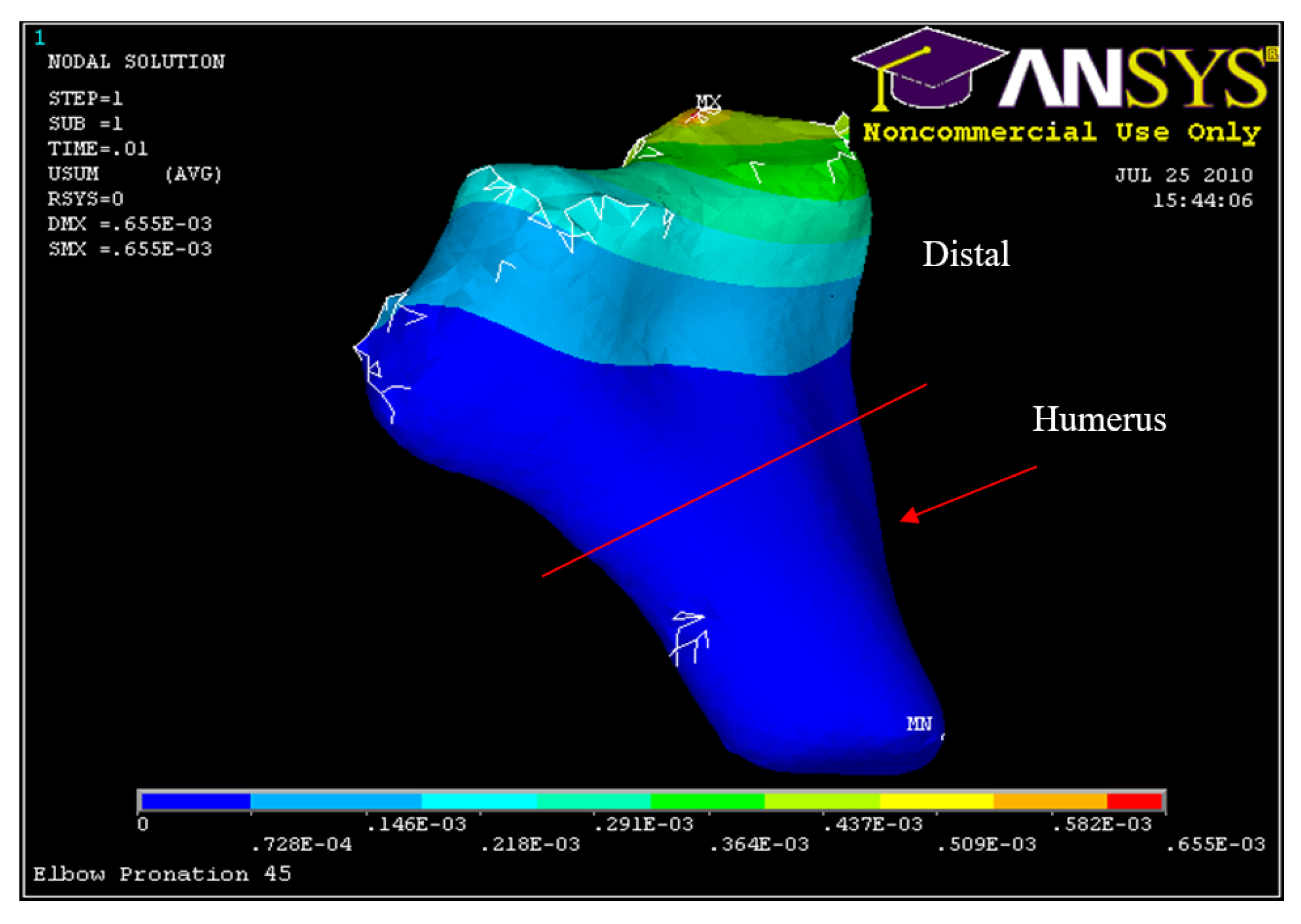

Figure 34.

Posterior Displacement 45° flexion and in pronation

Figure 34.

Posterior Displacement 45° flexion and in pronation

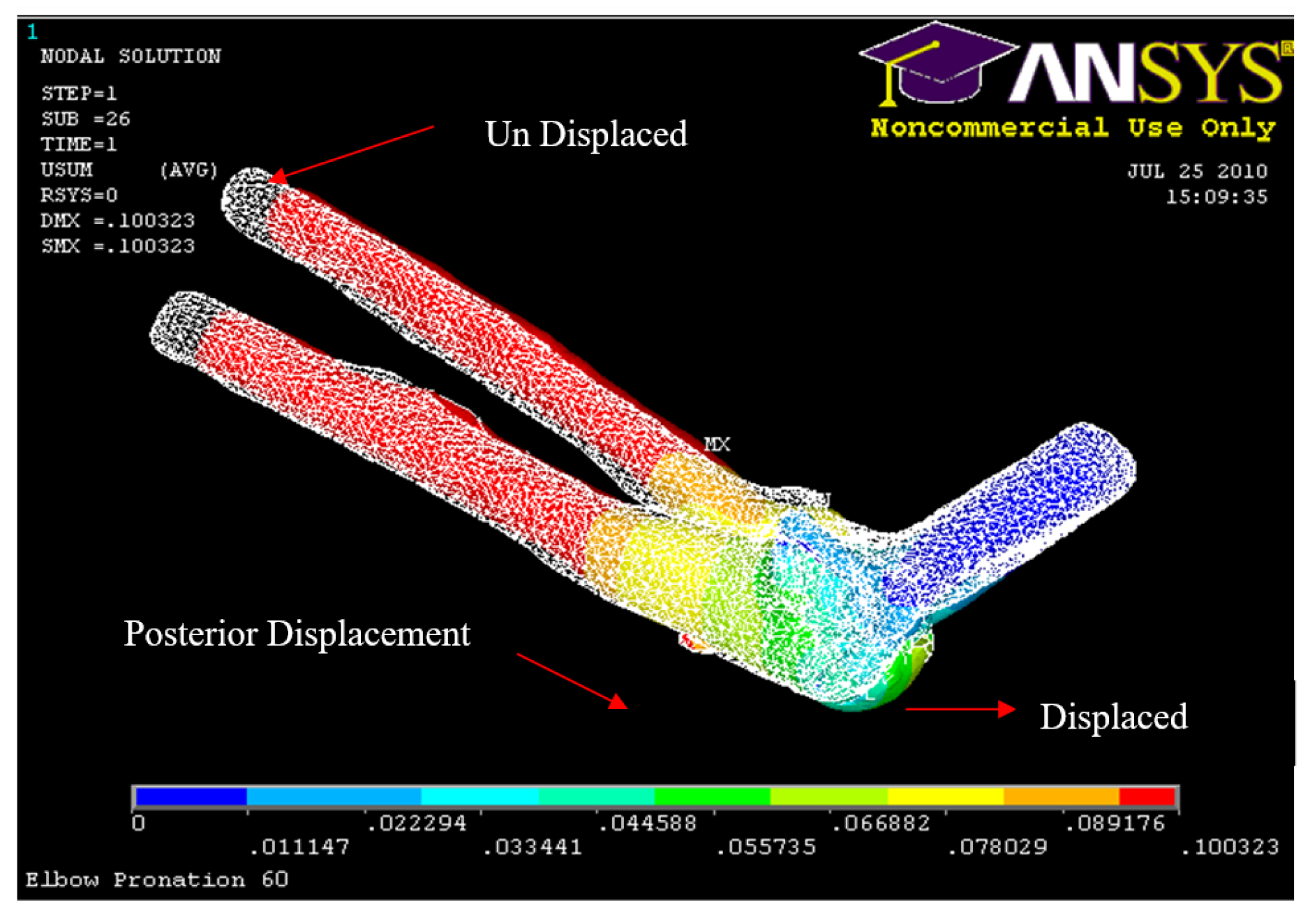

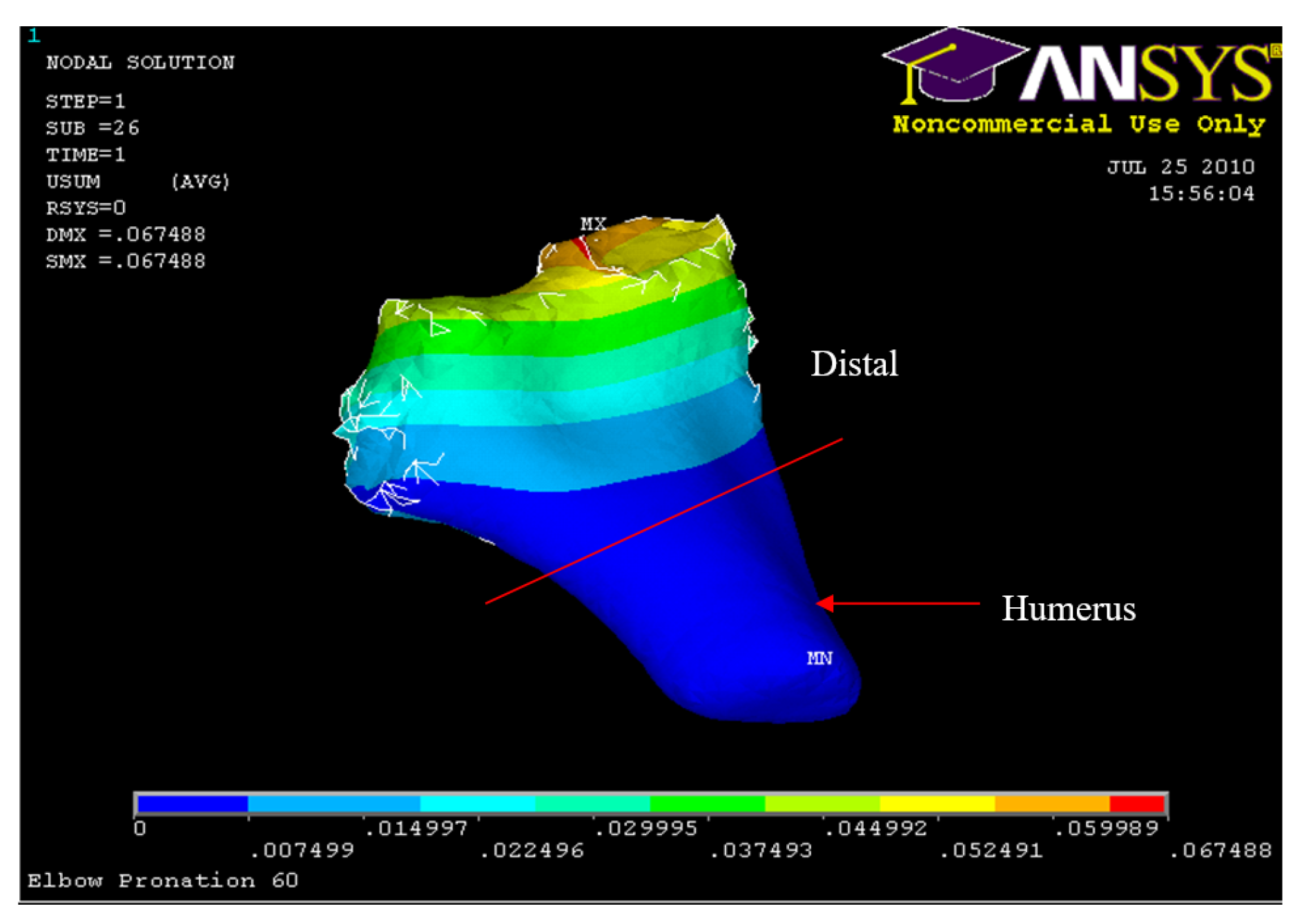

Figure 35.

Posterior Displacement 60° flexion and in pronation

Figure 35.

Posterior Displacement 60° flexion and in pronation

Figure 36.

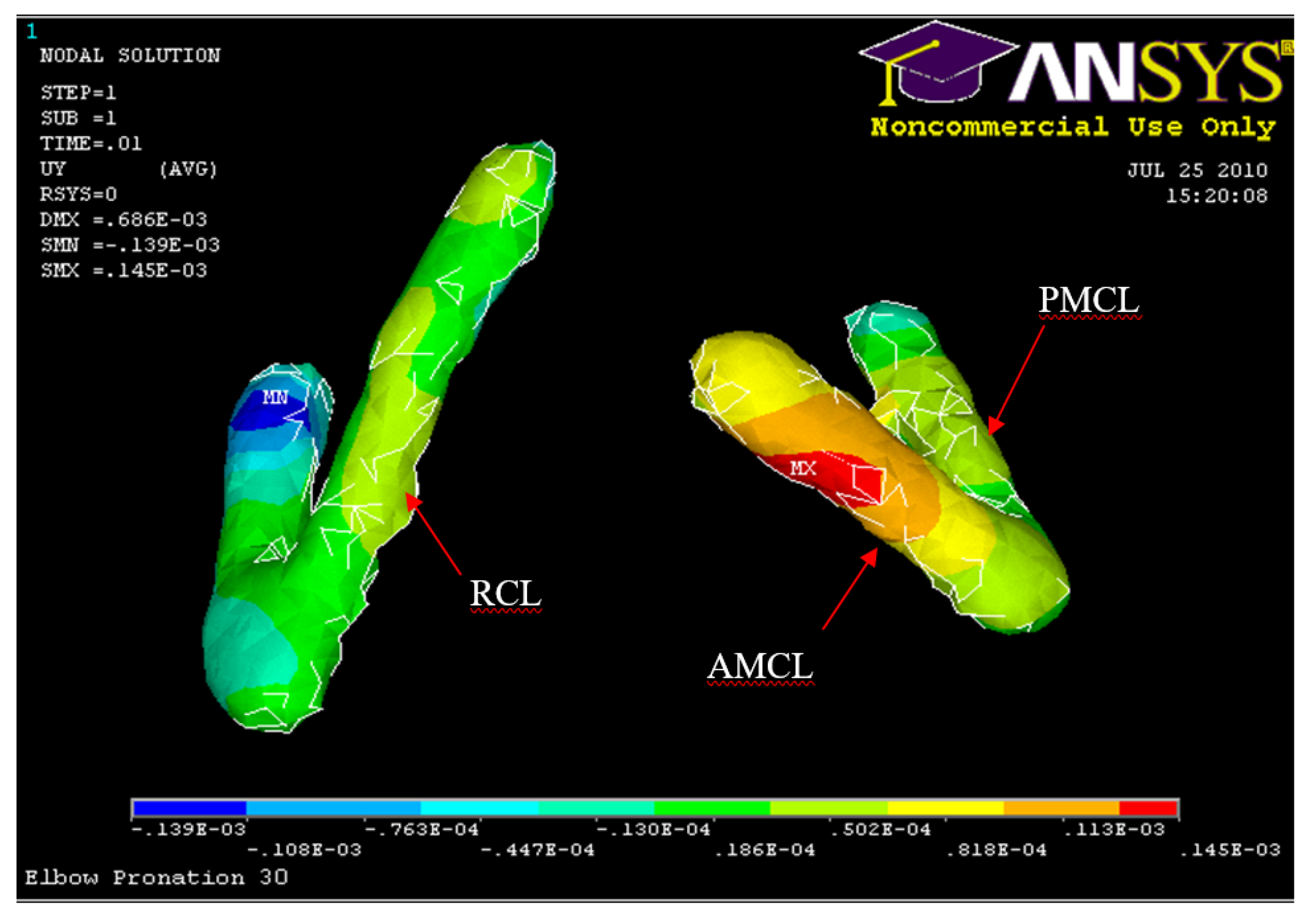

Posterior Displacement of AMCL, PMCL and RCL 30° flexion and in Pronation

Figure 36.

Posterior Displacement of AMCL, PMCL and RCL 30° flexion and in Pronation

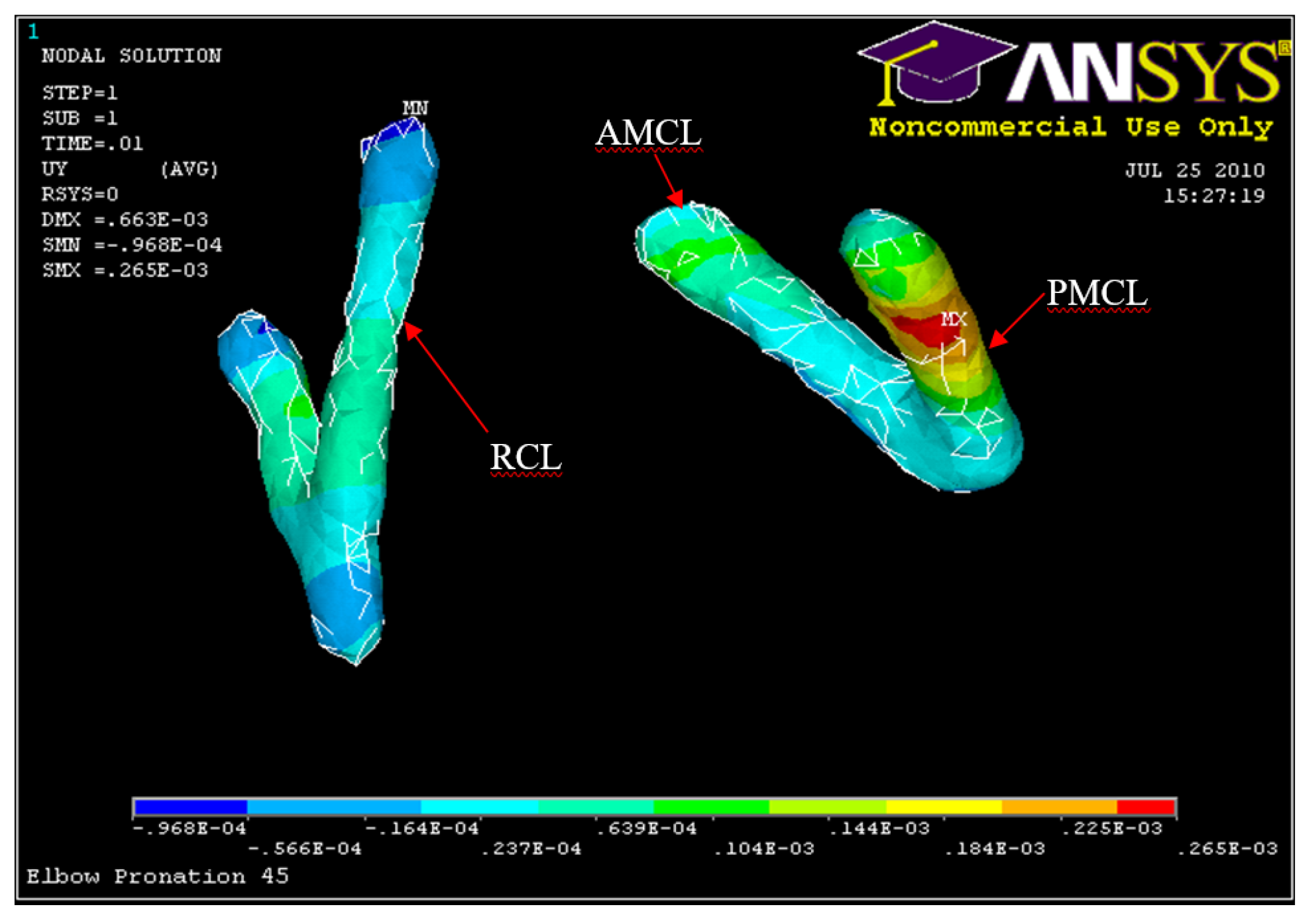

Figure 37.

Posterior Displacement of AMCL, PMCL and RCL 45° flexion and in pronation

Figure 37.

Posterior Displacement of AMCL, PMCL and RCL 45° flexion and in pronation

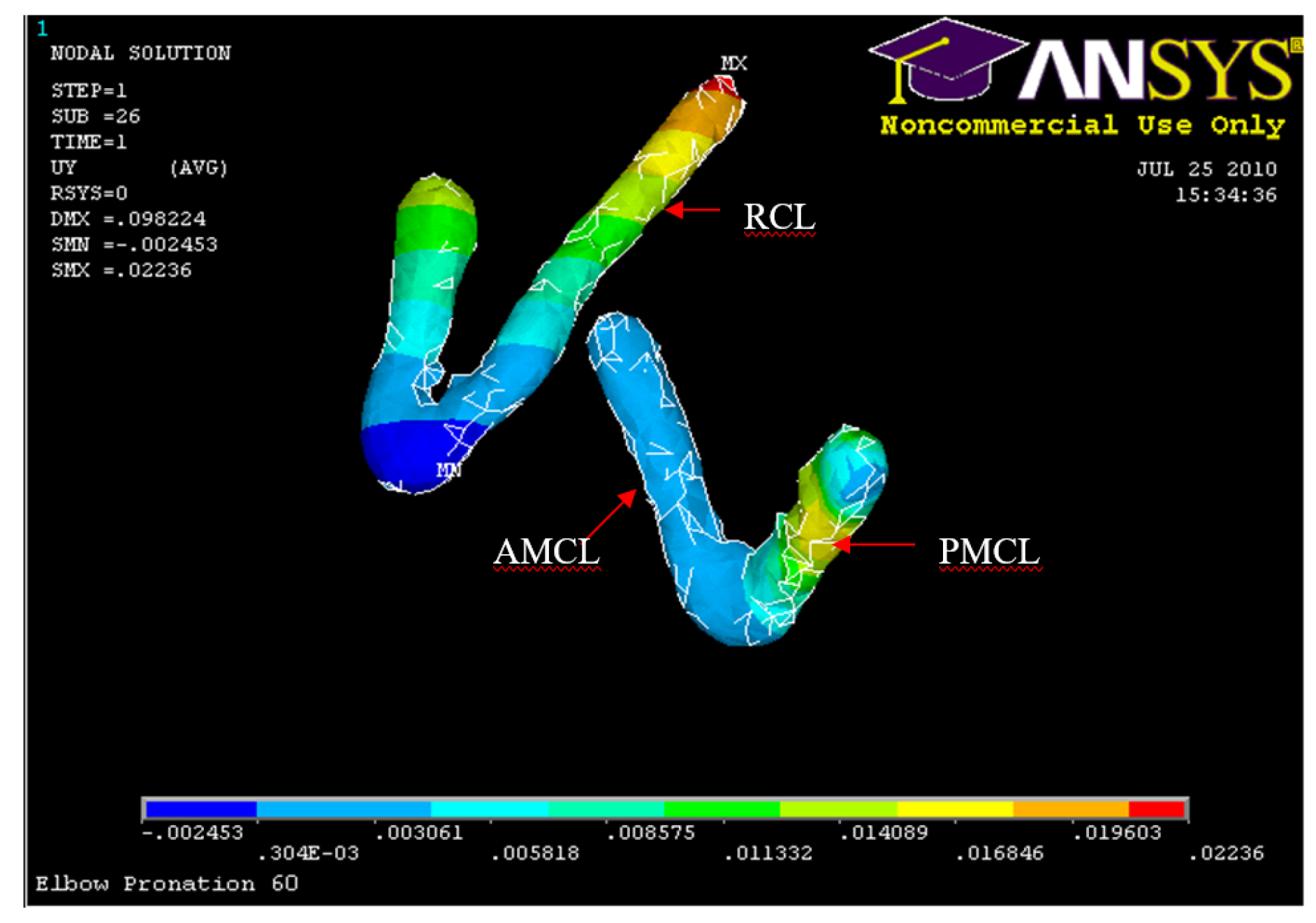

Figure 38.

Posterior Displacement AMCL, PMCL and RCL 60° flexion and in pronation

Figure 38.

Posterior Displacement AMCL, PMCL and RCL 60° flexion and in pronation

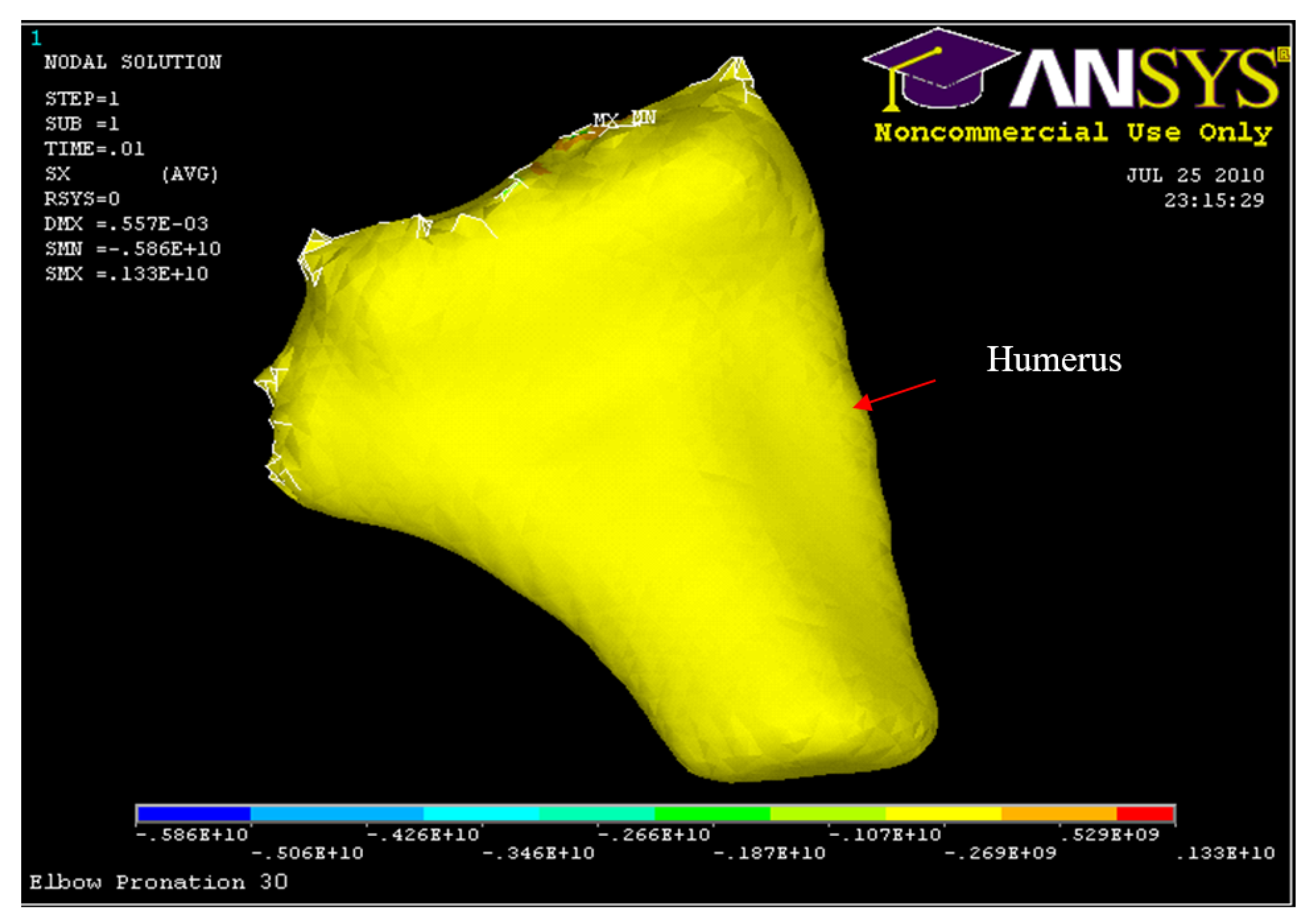

Figure 39.

Humerus Displacement 30° flexion and in pronation

Figure 39.

Humerus Displacement 30° flexion and in pronation

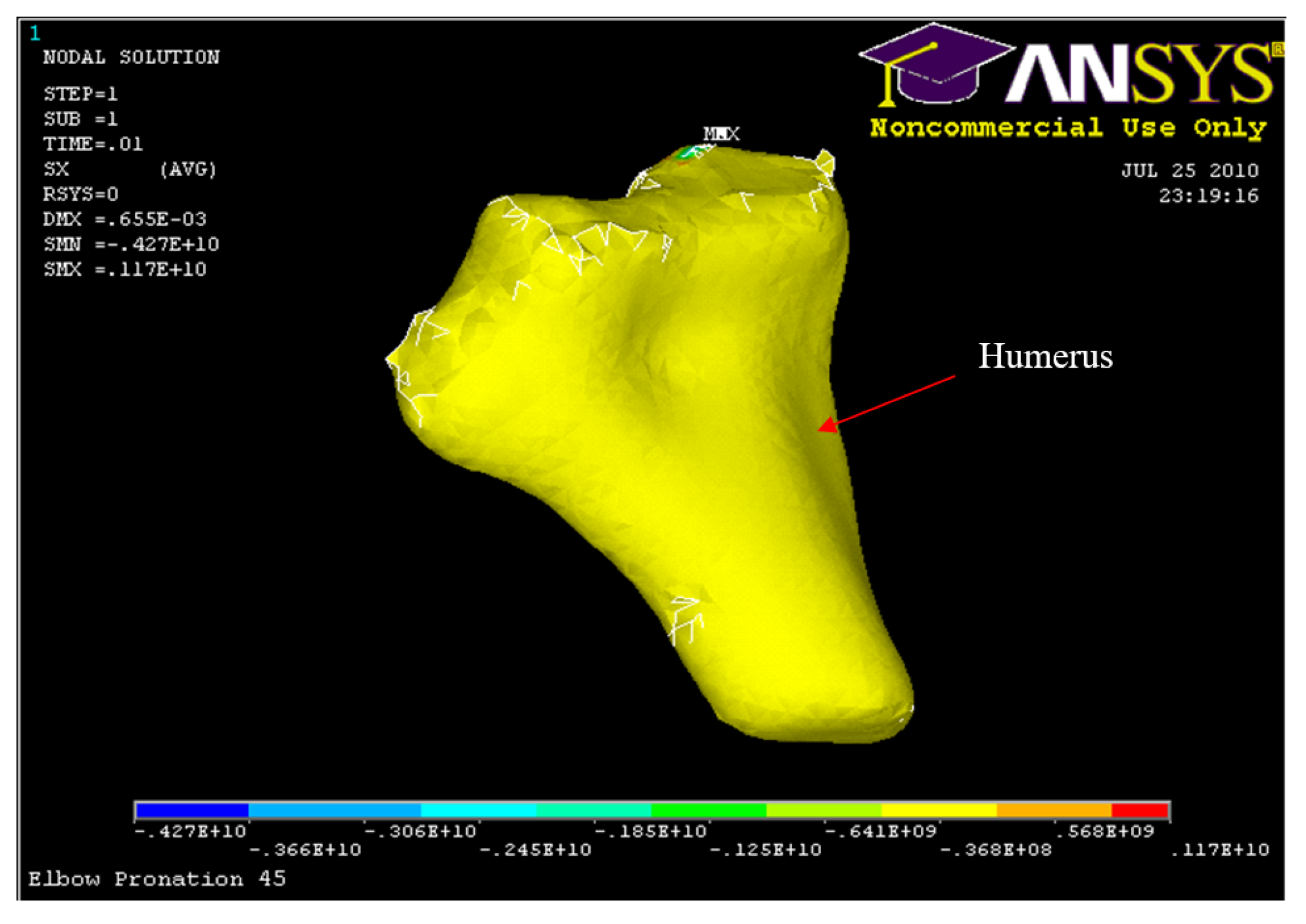

Figure 40.

Humerus Displacement 45° flexion and in pronation

Figure 40.

Humerus Displacement 45° flexion and in pronation

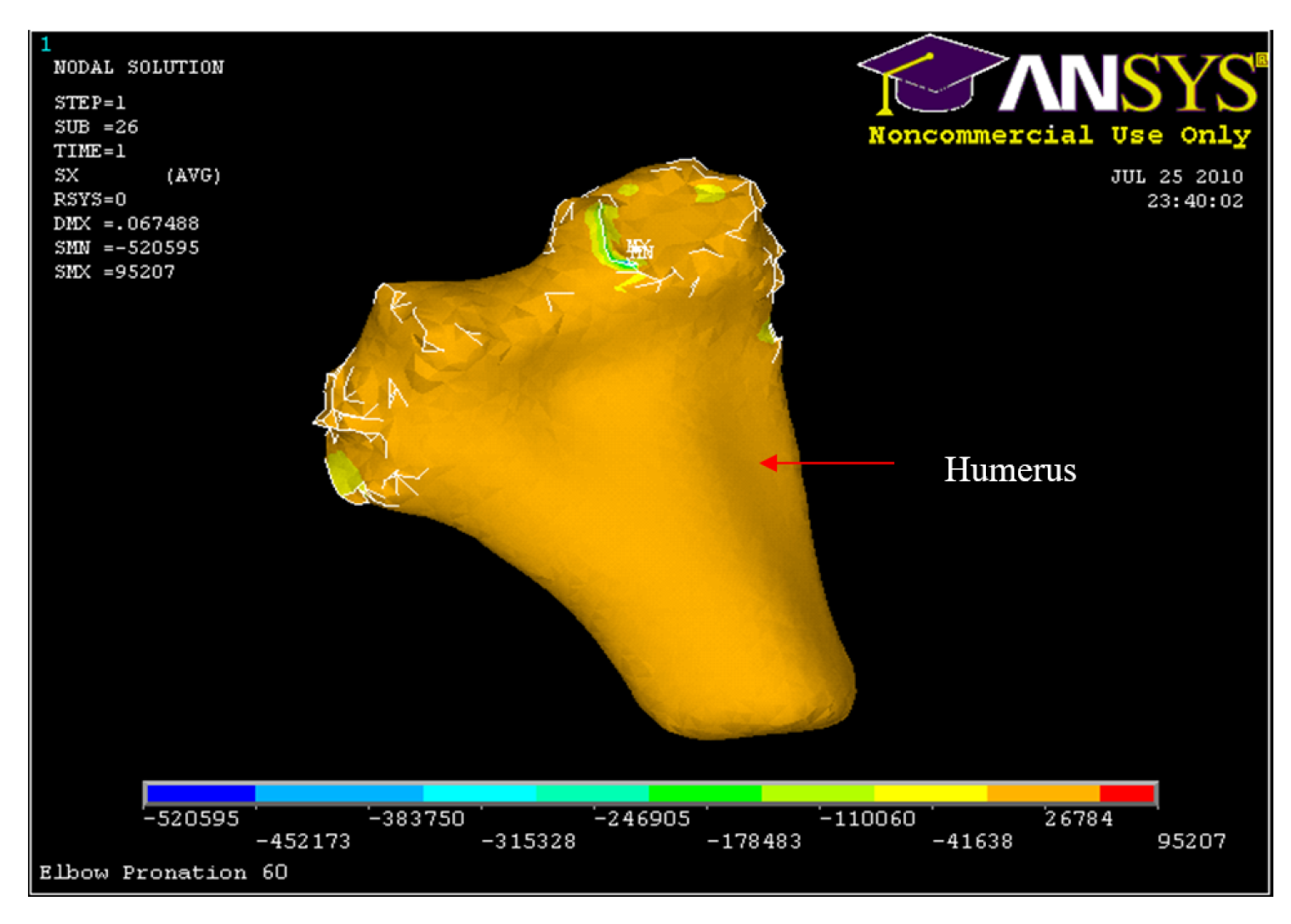

Figure 41.

Humerus Displacement 60° flexion and in pronation

Figure 41.

Humerus Displacement 60° flexion and in pronation

Figure 48.

Posterior Displacement Ulna-Radius

Figure 48.

Posterior Displacement Ulna-Radius

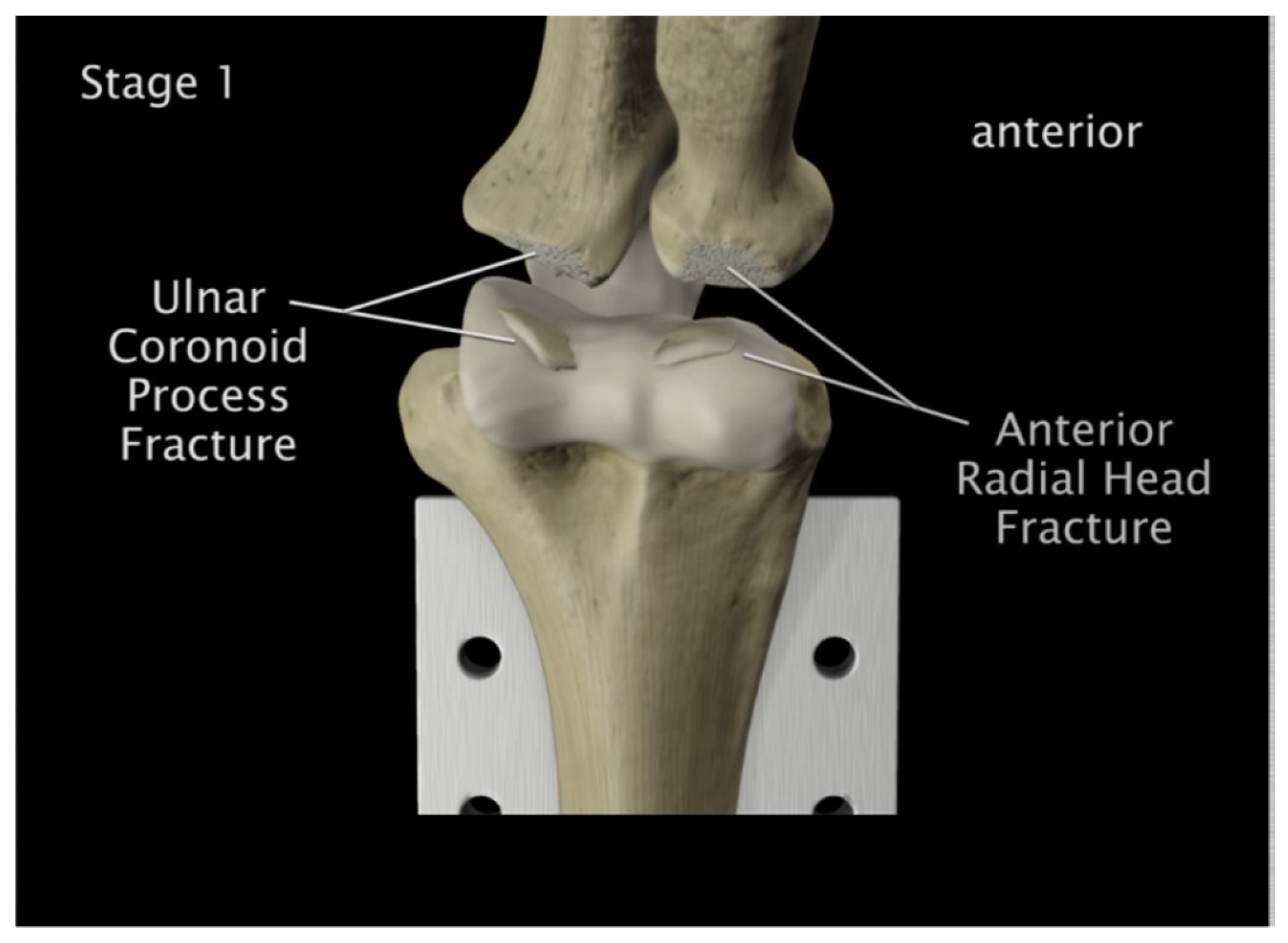

Figure 49.

Radial head & coronoid process fracture

Figure 49.

Radial head & coronoid process fracture

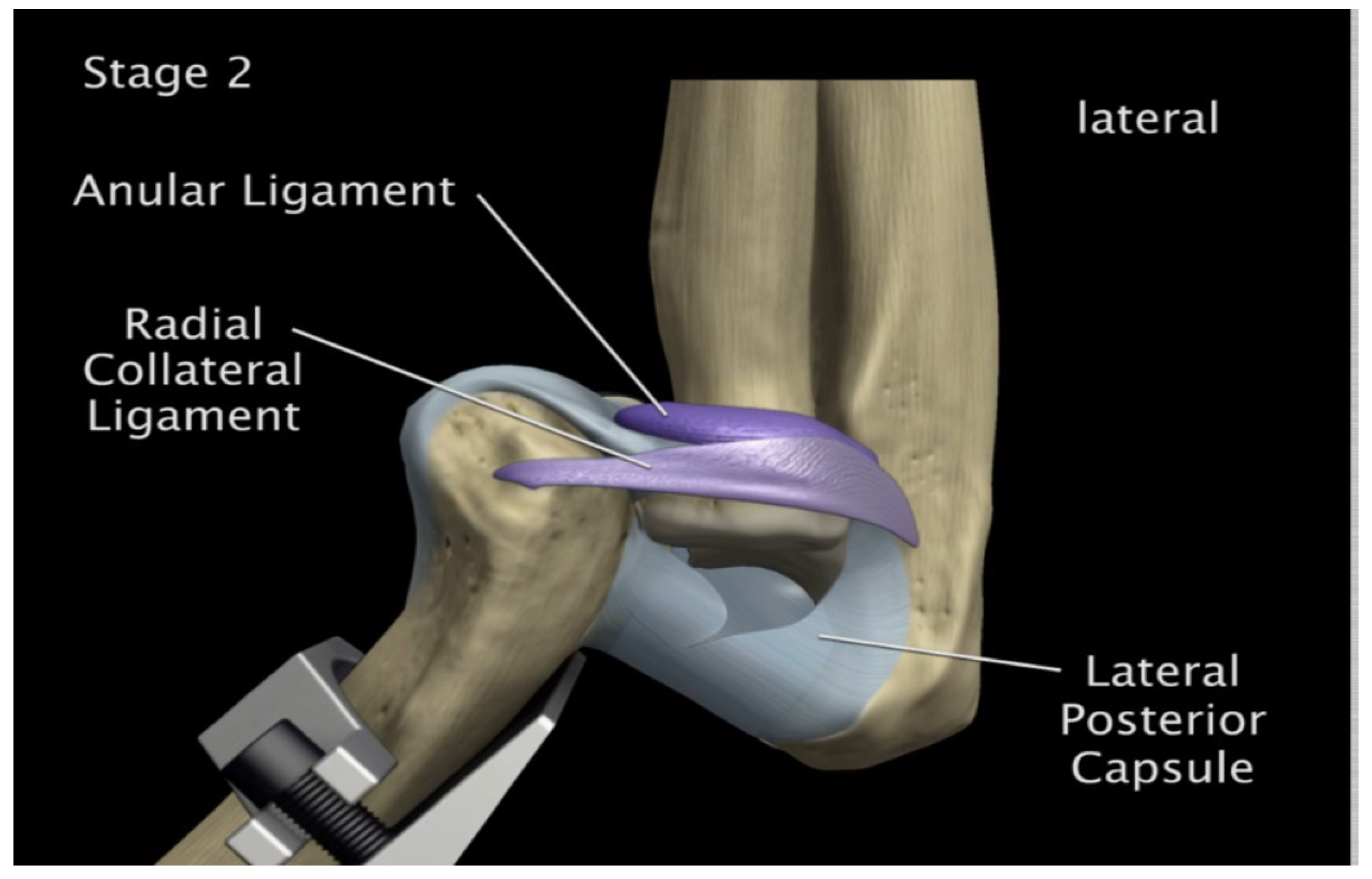

Figure 50.

Medial anterior and lateral posterior capsules were torn

Figure 50.

Medial anterior and lateral posterior capsules were torn

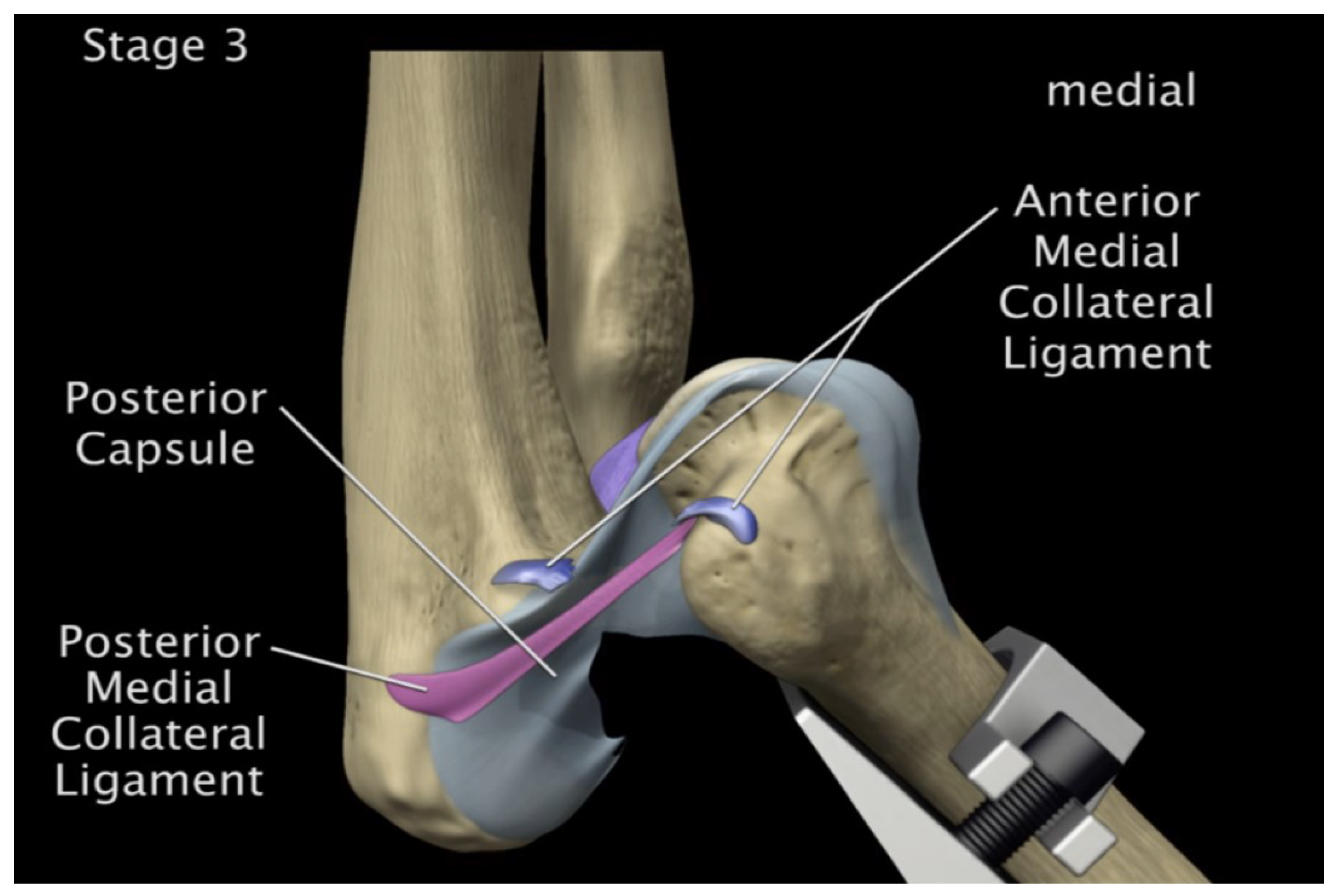

Figure 51.

Medial and lateral tearing of the anterior capsule

Figure 51.

Medial and lateral tearing of the anterior capsule

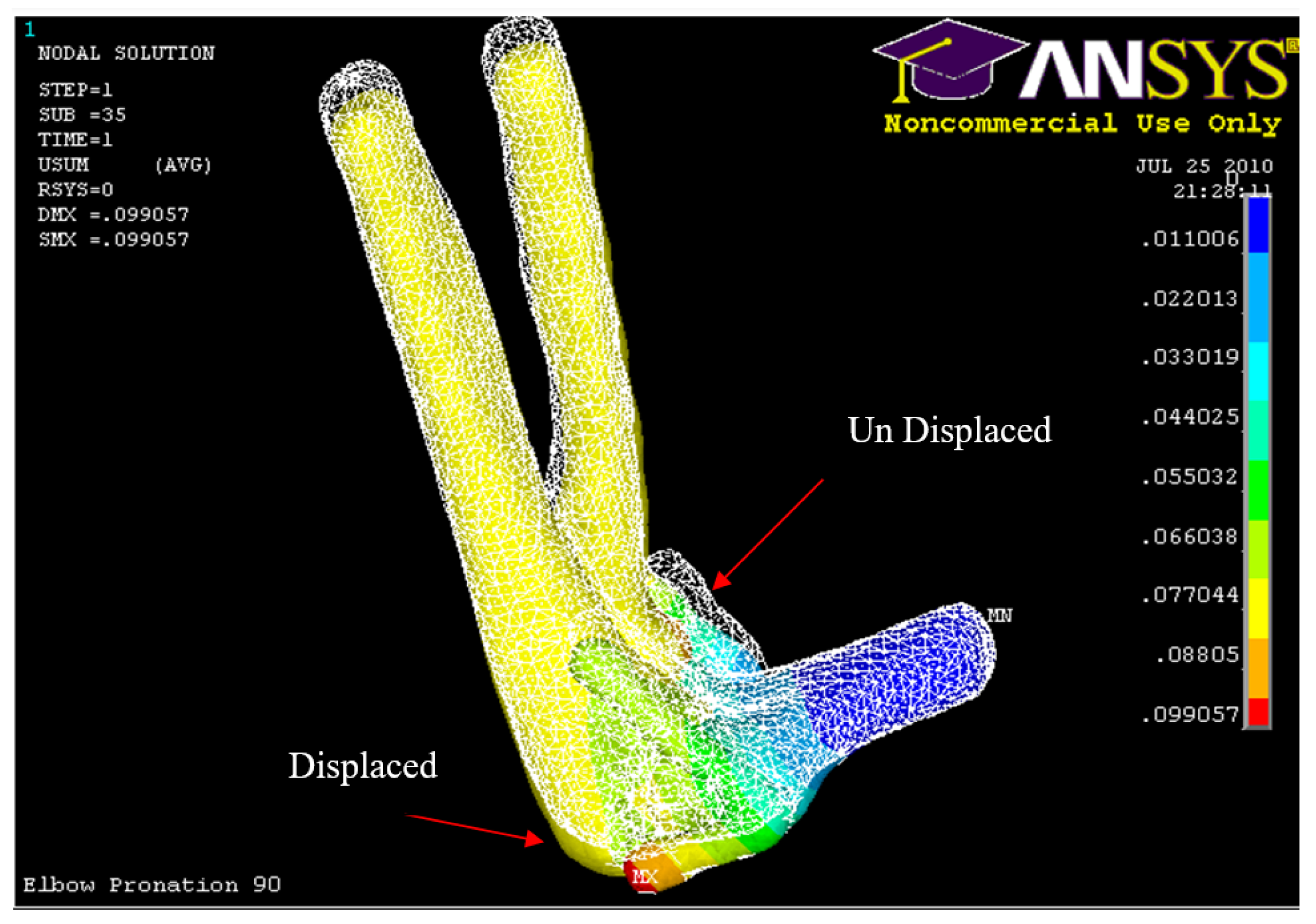

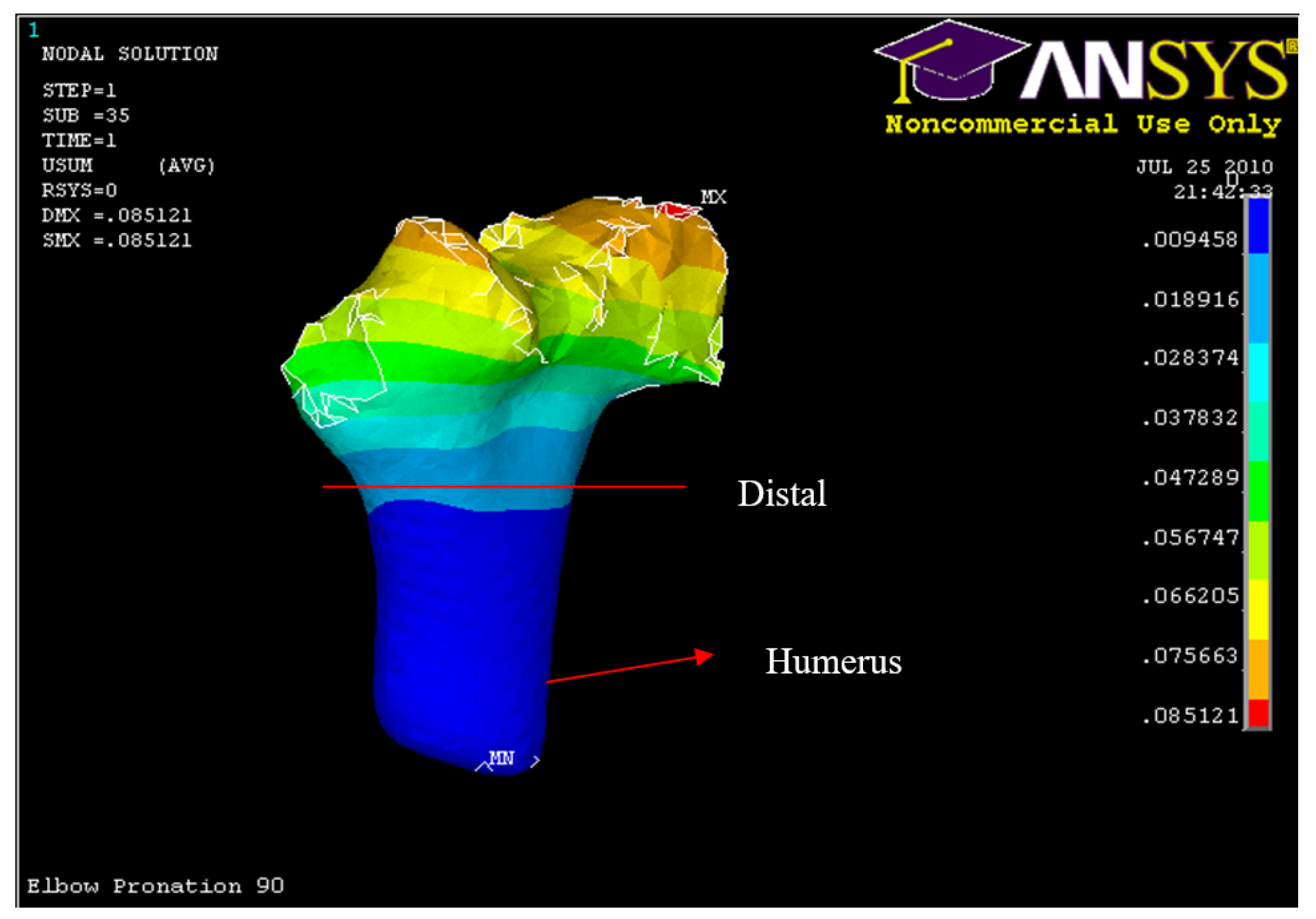

Figure 52.

Posterior displacement of ulna-radius 90° flexion and in pronation

Figure 52.

Posterior displacement of ulna-radius 90° flexion and in pronation

Figure 53.

Posterior Displacement of Humerus 90° flexion and in pronation

Figure 53.

Posterior Displacement of Humerus 90° flexion and in pronation

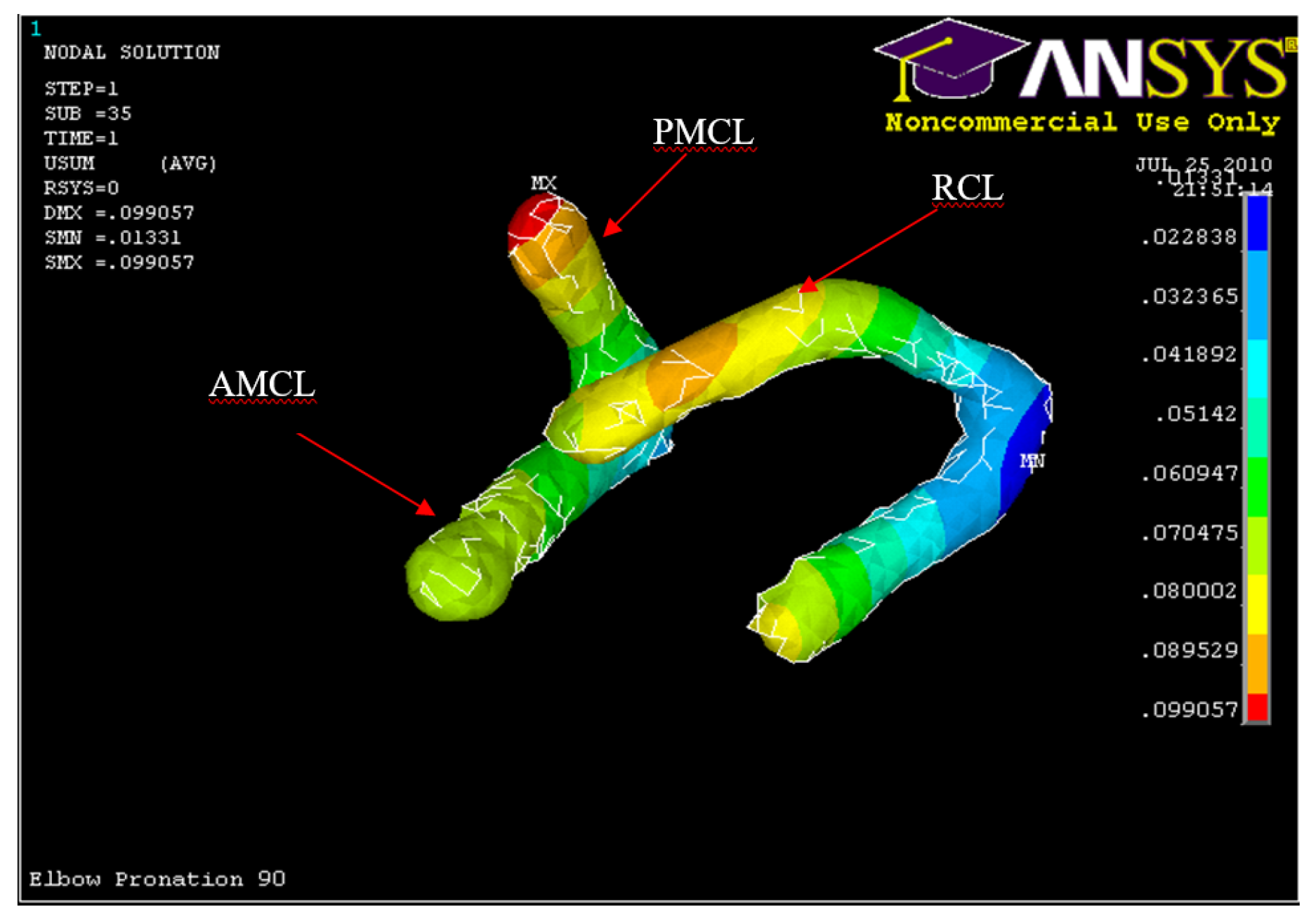

Figure 54.

Posterior Displacement of AMCL, PMCL and RCL in 90° flexion and in pronation

Figure 54.

Posterior Displacement of AMCL, PMCL and RCL in 90° flexion and in pronation

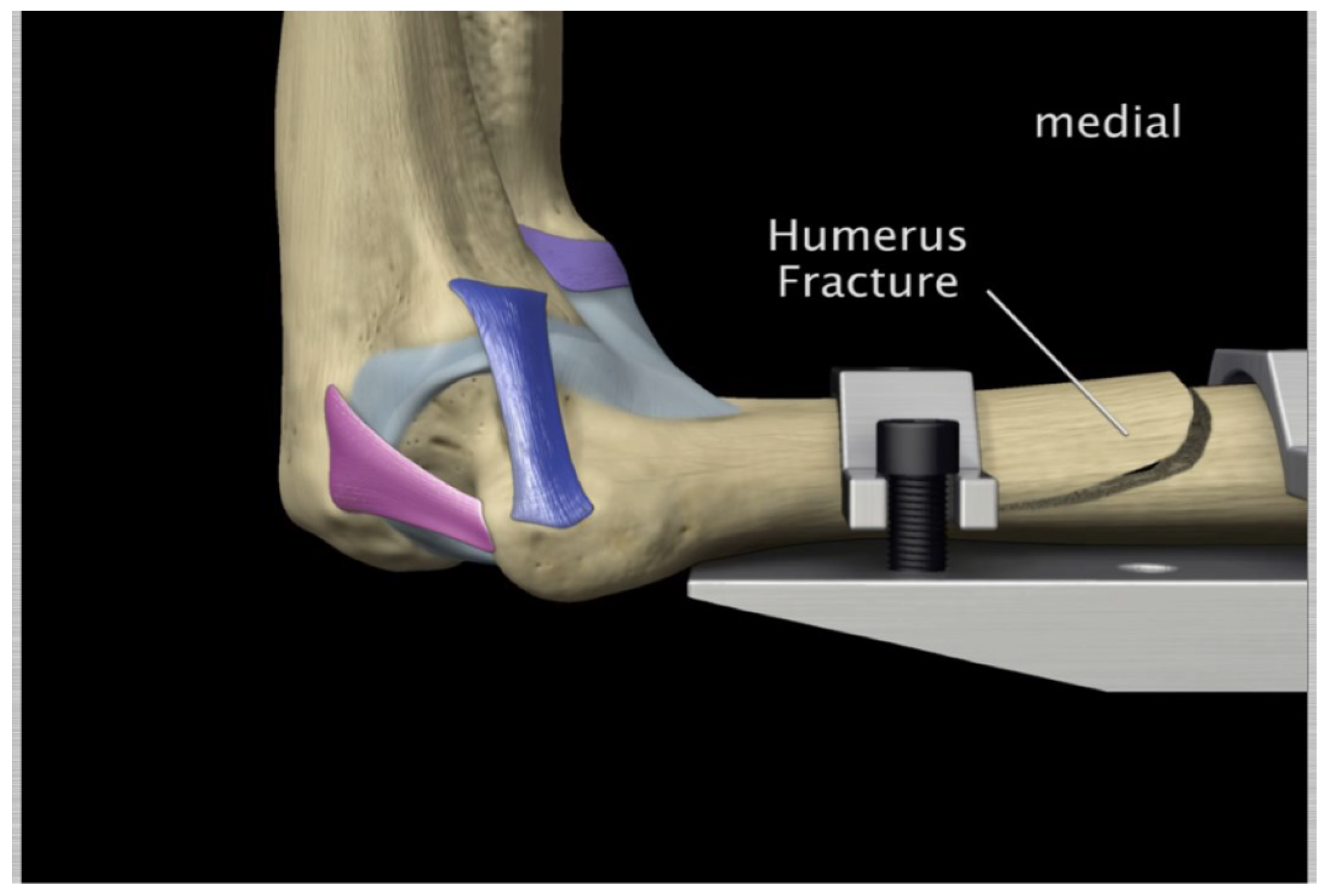

Figure 55.

Humerus distal fracture 90°flexion and in pronation

Figure 55.

Humerus distal fracture 90°flexion and in pronation

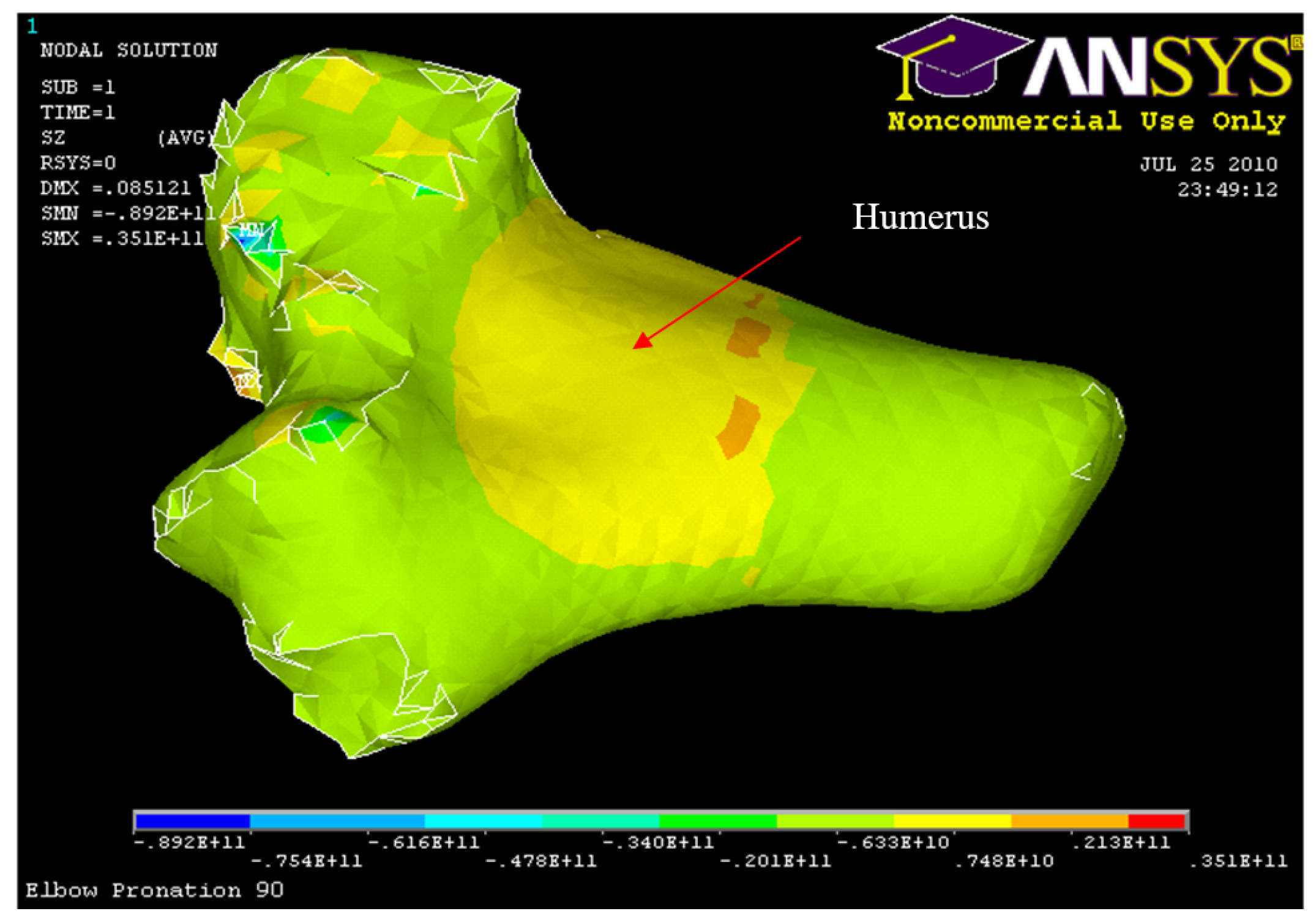

Figure 56.

Nodal Stress at Humerus 90° flexion and in pronation

Figure 56.

Nodal Stress at Humerus 90° flexion and in pronation

Table 1.

Material Properties of Bone and Soft Tissues

Table 1.

Material Properties of Bone and Soft Tissues

| Material |

Young Modulus |

Poisson’s |

Yield Strength |

| Cortical Bone |

15-20 GPa |

0.3 |

115-133 MPa |

| Cancellous Bone |

500-1500 MPa |

0.2 |

3-10 MPa |

| Cartilage |

5 MPa |

0.49 |

|

| AMCL |

118 MPa |

|

21 MPa |

| PMCL |

97 MPa |

|

19 MPa |

| RCL |

54 MPa |

|

16 MPa |

Table 3.

Ligament Mechanical Properties

Table 3.

Ligament Mechanical Properties

| AMCL Stress MPa |

Strain |

PMCL Stress MPa |

Strain |

RCL Stress MPa |

Strain |

| 2 |

4 |

0.6 |

4 |

0.6 |

4 |

| 3 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

| 4 |

6.5 |

1.5 |

6.5 |

1.4 |

6.5 |

| 5 |

7.9 |

2.2 |

7.9 |

2 |

7.9 |

| 7 |

10 |

3.5 |

10 |

3 |

10 |

| 8 |

11.2 |

4.2 |

11.2 |

3.2 |

11.2 |

| 9 |

12.8 |

5.2 |

12.8 |

3.6 |

12.8 |

| 10 |

13.2 |

5.9 |

13.2 |

3.9 |

13.2 |

| 11.6 |

15 |

7.2 |

15 |

4 |

15 |

| 16.9 |

20 |

12 |

20 |

6 |

20 |

| 22.2 |

25 |

17.4 |

25 |

8.9 |

25 |

| 26.9 |

30 |

25 |

30 |

11 |

30 |

Table 4.

Summary of loading and boundary conditions.

Table 4.

Summary of loading and boundary conditions.

| Group |

Components |

Displacements (m) |

Load (N) |

| Axial Group |

Humerus |

Ux = 0, Uy = 0, Uz = 0 |

Fx = 0-2000 N |

| Ulna-Radius |

Ux = 0.01, Uy = 0, Uz = 0 |

| Ligament Attachments |

Ux = 0, Uy = 0, Uz = 0 |

| Hyper-extension Group |

Humerus |

Ux = 0, Uy = 0, Uz = 0 |

Fz = 0-500 N |

| Ulna-Radius |

Ux = 0, Uy = 0, Uz = 0.01 |

| Ligament Attachments |

Ux = 0, Uy = 0, Uz = 0 |

Table 5.

Human Cadaver Arms Groups Experiments: Characteristics and Average Dislocation Loads Obtained

Table 5.

Human Cadaver Arms Groups Experiments: Characteristics and Average Dislocation Loads Obtained

| Group |

Number of elbows |

Side |

Gender |

Characteristics |

Average dislocation load |

| 1 |

4 |

Left |

Male |

Hyper-extension load 0° flexion |

600 N |

| 2 |

8 |

Right |

Female |

Axial load 5°, 15°, 30°, 45° flexion |

1741 N |

| 4 |

Left |

| 2 |

Left |

Male |

2935 N |

| 3 |

2 |

Male |

Left |

Axial load 90° flexion |

2766 N |

Table 6.

Human Cadaver Orientation used in the Experimental Study.

Table 6.

Human Cadaver Orientation used in the Experimental Study.

| Gender |

Left/right |

Orientation |

Flexion angle |

Number of elbows |

| Male |

Left |

Supination |

0° |

4 |

| Neutral |

30° |

1 |

| Pronation |

45° |

3 |

| Female |

Left |

Supination |

30° |

1 |

| Neutral |

15° |

1 |

| 30° |

1 |

| Pronation |

5° |

2 |

| Right |

Pronation |

15° |

4 |

| 30° |

1 |

| 45° |

2 |

| Neutral |

30° |

1 |

Table 7.

Max and min nodal displacement for ulna-radius, AMCL, PMCL, LCL and humerus (5° flexion and in pronation)

Table 7.

Max and min nodal displacement for ulna-radius, AMCL, PMCL, LCL and humerus (5° flexion and in pronation)

| Structure |

Min vector sum displacement (m) |

Max vector sum displacement (m) |

| Ulna-Radius |

0.0178 |

0.08 |

| AMCL |

0.00920 |

0.0689 |

| PMCL |

0.0167 |

0.0316 |

| RCL |

0.0 |

0.0615 |

| Humerus |

0.0 |

0.0192 |

Table 8.

Maximum Nodal Stresses occurred at Conoriod Process, Radial Head and Humerus

Table 8.

Maximum Nodal Stresses occurred at Conoriod Process, Radial Head and Humerus

| Structure |

Max compressive/tension stress MPa |

| Coronoid process |

-13.6 |

| Radial head |

-13.6 |

| Humerus |

-17.5 |

Table 9.

List of max, min vector sum displacement of ulna radius (30°, 45°, and 60° flexion and in pronation)

Table 9.

List of max, min vector sum displacement of ulna radius (30°, 45°, and 60° flexion and in pronation)

| Structure |

Min vector sum displacement (m) |

Max vector sum displacement (m) |

| Ulna-Radius (30° Model) |

0.0224 |

0.1 |

| Ulna-Radius (45° Model) |

0.0569 |

0.1 |

| Ulna-Radius (60° Model) |

0.0668 |

0.1 |

Table 10.

List of max, min vector sum displacement of AMCL, PMCL and RCL (30°, 45°, and 60° flexion and in pronation)

Table 10.

List of max, min vector sum displacement of AMCL, PMCL and RCL (30°, 45°, and 60° flexion and in pronation)

| Structure |

Min vector sum displacement (m) |

Max vector sum displacement (m) |

| AMCL (30° Model) |

0.00106 |

0.0145 |

| PMCL (30° Model) |

-0.00130 |

0.00502 |

| RCL (30° Model) |

0.00106 |

0.00502 |

| AMCL (45° Model) |

0.00639 |

0.0104 |

| PMCL (45° Model) |

0.00639 |

0.0265 |

| RCL (45° Model) |

-0.00968 |

0.00639 |

| AMCL (60° Model) |

0.00857 |

0.00857 |

| PMCL (60° Model) |

0.00857 |

0.0196 |

| RCL (60° Model) |

0.00245 |

0.0223 |

Table 11.

List of max, min vector sum displacement of humerus (30°, 45°, and 60° flexion and in pronation)

Table 11.

List of max, min vector sum displacement of humerus (30°, 45°, and 60° flexion and in pronation)

| Structure |

Min vector sum displacement (m) |

Max vector sum displacement (m) |

| Humerus (30° Model) |

0.0 |

0.0248 |

| Humerus (45° Model) |

0.0 |

0.0437 |

| Humerus (60° Model) |

0.0 |

0.0449 |

Table 13.

Max and Min Nodal Displacement for ulna-radius, AMCL, PMCL, LCL and Humerus 90° flexion and in pronation

Table 13.

Max and Min Nodal Displacement for ulna-radius, AMCL, PMCL, LCL and Humerus 90° flexion and in pronation

| Structure |

Min vector sum displacement (m) |

Max vector sum displacement (m) |

| Ulna-Radius |

0.0330 |

0.0990 |

| AMCL |

0.0323 |

0.0704 |

| PMCL |

0.0323 |

0.0990 |

| RCL |

0.0228 |

0.0895 |

| Humerus |

0.0094 |

0.0756 |