Introduction

Sustainability is the most sought-after topic in the polymer industry and are a critically examined value chain in lieu of its ubiquitous nature [

1]. Numerous polymer products are found in our everyday life, from pens, and bottles to different coatings, composites and tires[

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Though a polymer can be technically distinguished into plastics, fibers, elastomers, films, thermosets etc., its universal nature has led to more simplistic “plastic” reference in common discussions[

7]. There is a lack of clarity when it comes to the available standards, certification methods, design guidelines, carbon footprint calculation etc.[

8]. The plethora of terminologies only worsen the already existing confusions and overlaps[

9]. To give clarity of the terms used in sustainability forums, an introductory structure was first adopted in this short communication to provide a more holistic approach. The jargons around polymer sustainability or just sustainability in general is abundant. Without a standardized and established guideline for each, these terms would just remain as words with very less value[

10]. A good understanding of these terms is important for distinguishing what each term encompasses in terms of sustainability[

11]. In the later sections, more in-depth discussion is provided to clarify the concept of biobased/biomass/bioattributed concepts. It sure sounds different, but the foundational factor remain the same and a detailed discussed is entailed. The last section provide a specific perspective on polymer sustainability adopted by the major polymer manufacturers in regard to the greenhouse gas emission reduction targets[

12]. Therefore, an attempt is made in this short communication to contextualize the labyrinth within the polymer sustainability horizon and steps to navigate through them.

Holistic Outlook

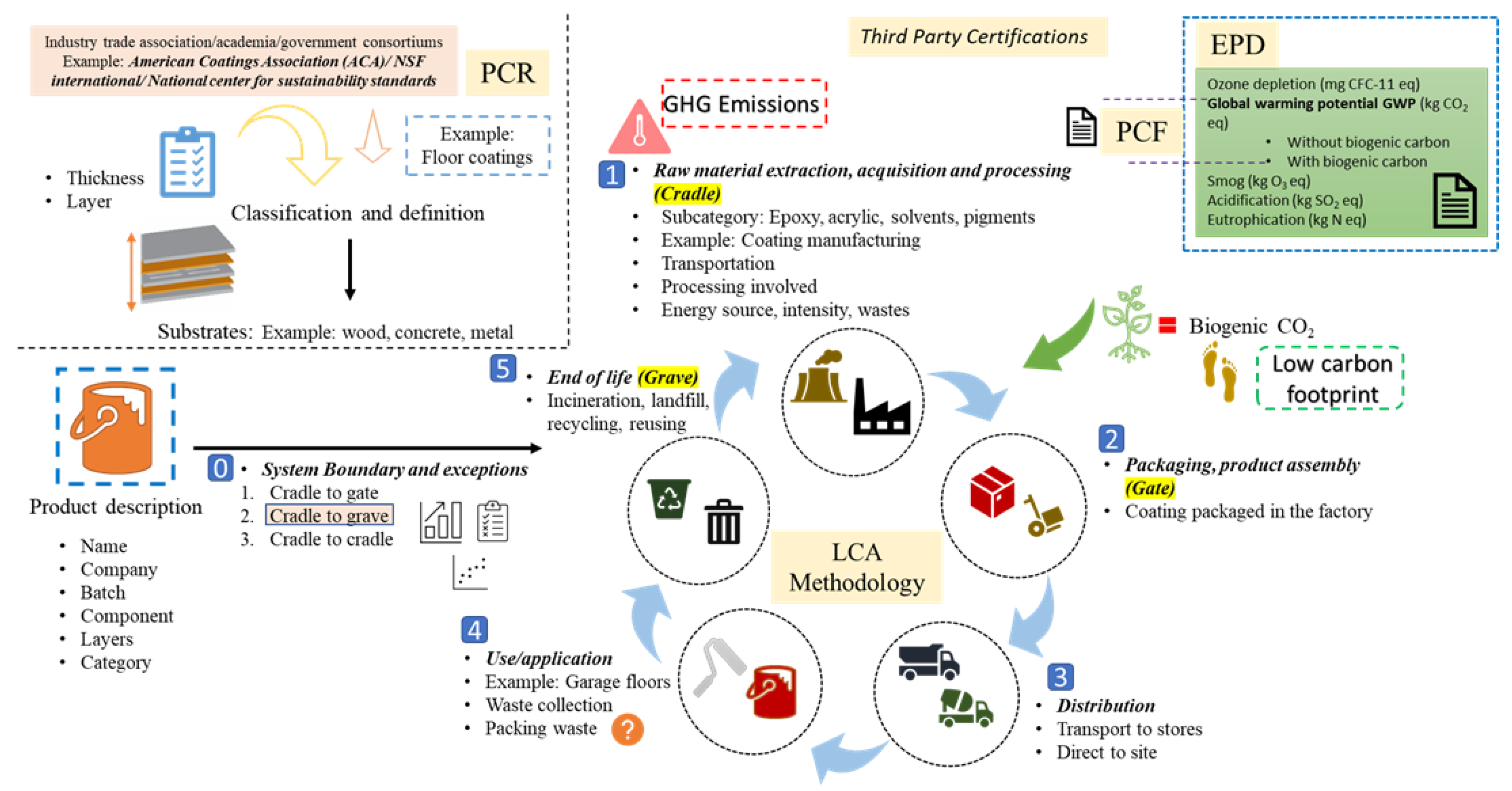

As shown in the

Figure 1 and

Table 1, the first stage in development of a more sustainable product involves setting the guideline called the product category rules (PCR). PCR are a distinct set of environmental product attributes within a defined product category[

13]. These rules can vary by region/geographical location and product category. Most recognized PCRs are usually set by consortium of internal stakeholders within the industry, including industry collaborators, individual manufacturers, LCA practitioners, subject matter experts, often from academia, competing companies, non-biased government, and non-government agencies[

14]. This process is conducted in the presence/mediation of nationally recognized program operators so that these independent science based environmental factors are discussed with highest levels of transparency. For coatings industry specifically, an institution involving in PCR generation would include American coating association (ACA)[

15]. As an American National Standards Institute (ANSI) eligible program operator, NSF’s National Center for Sustainability Standards is an operator that guide industries, trade organizations or individual companies through an ISO 14025-compliant process to develop a PCR for their product categories. An exemplary example of ACA’s contribution in PCR can be observed in the architectural and powder coating industries, wherein a consensus was reached between all the stakeholders on the PCR needed to define architectural and powder coating products[

13,

14]. All polymer industries can follow the footsteps and devise a similar PCR report.

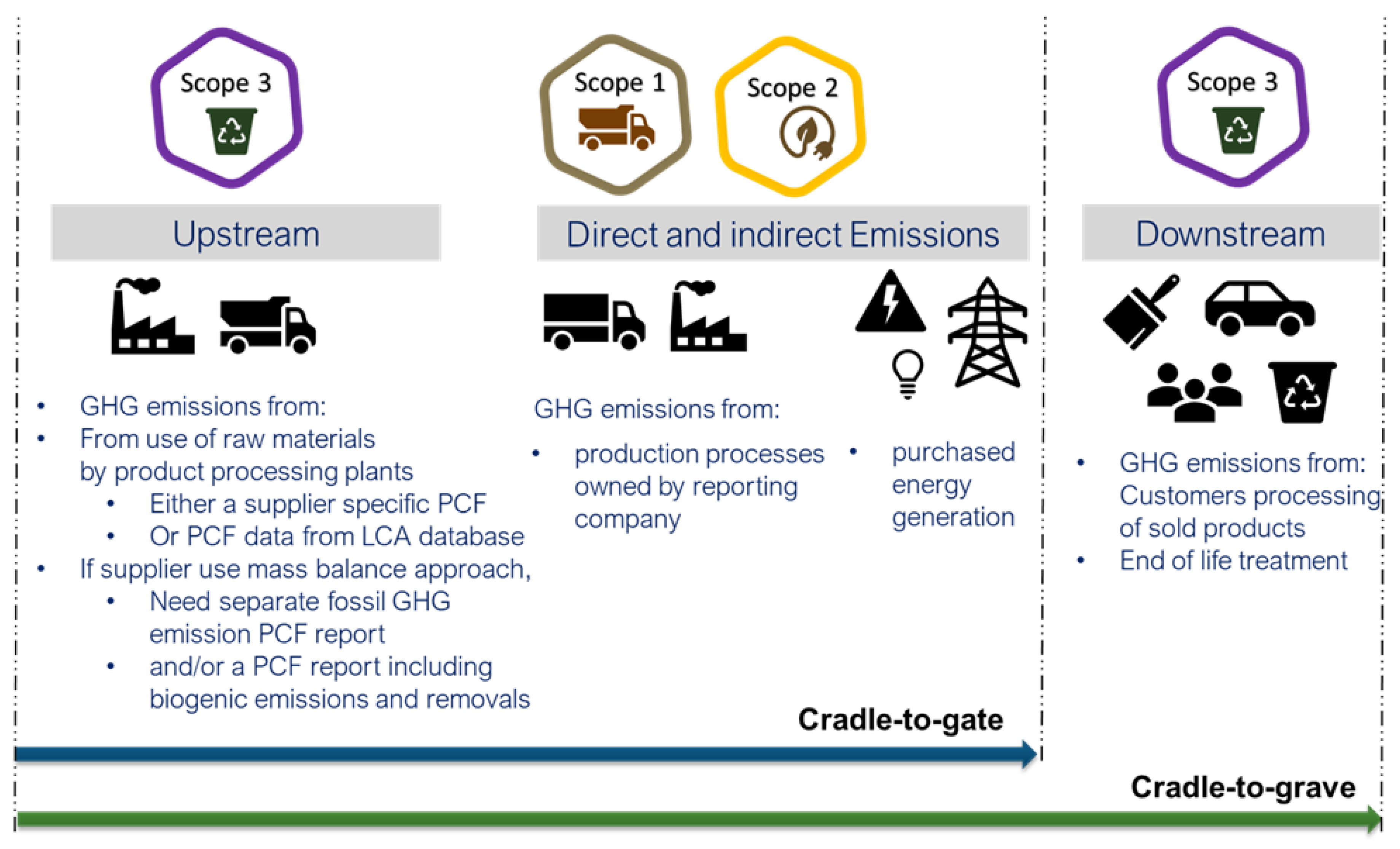

Furthermore, PCR defines the parameters for conducting the life cycle assessment (LCA) for a particular product group. In accordance with the PCR, LCA is carried out (use of software or in-house calculation tool utilizing ISO standards) to evaluate environmental impact of a product[

16]. The process involves raw material acquisition, production processing, use and end of life. It is necessary that scope of the life cycle of a product would need to be set prior as the boundary condition for effectiveness; example, cradle to gate (factory gate), or cradle to end of life (EOL) approach[

17] (

Figure 2). LCA also helps identify the critical environmental impact categories enabling the most beneficial and cost-effective product development operational practices and business approaches. Environmental product declarations (EPD) is a standard report that’s collected during the LCA process of a product utilizing ISO 14,025 standards entailing a critical communication process to ensure that the ISO standards and the industry consensus standards described in the Product Category Rule (PCR) document are followed[

18]. Product carbon footprint (PCF) on another hand, would then be a factor in the EPD as it is derived from the Global warming potential (GWP) part of EPD[

19]. Calculating scope 3 emissions are particularly challenging for a polymer company due to the direct and indirect aspects (upstream and downstream) encompassing the suppliers and customers. Scope 3 targets can be achieved only through co-operations with the associates along the value chain, innovation, and a detailed plan of action involving all the stakeholders involved.

ISO 14,067 is used for the PCF calculation and can be a stand-alone report that polymer manufacturers/suppliers can provide to the customers. Similarly, paint manufacturers can request the same from their suppliers. The cradle-to-gate or partial Product Carbon Footprint (PCF) will be the sum of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, expressed as CO2 equivalents, from the resource extraction up to the production of the final product/factory gate[

20]. EPD thus opens up the possibility to objectively compare and describe a product environmental impact throughout the specified life cycle. EPDs and PCRs are not required by law or Federal regulation at the moment but can give a competitive edge on sustainably advantaged products as they can differentiate products in the marketplace, when responding to increased demand for sustainable product with more transparent and credible environmental claims[

21]. Notably, sustainability guidelines and green certification programs might give preferential treatment to products with verified EPDs. Examples of published EPDs from industry competitors constitute architectural coating products category by companies like PPG and Sherwin Williams utilizing PCRs set by ACA, LCA database by GaBi/Sphera[

22,

23,

24] and together for sustainability (TFS) or Science based target initiative (SBTi) .

In order to decipher

Figure 1 and above discussion with ease, it is important that ongoing chemical transformations are reflected with the help of an example or case study. Further, it can also help illustrate the practical application and benefits of these tools in the industry. In that context, resinous floor coatings are examined here as the case study. PCR for resinous floor coatings was published by ACA.[

14]

Figure 3 shows a detailed schematics on the PCR, LCD, PCF, EPD terminologies. This type of layout can be devised for any type of coatings or polymer products by analogous trade associations or consortiums. GHG emissions are the most prominent in the raw material acquisition and manufacturing stage. Efforts are ongoing to include renewable energy sources (solar, wind, geothermal/0 to offset some of the GHG emissions reducing the scope 1 and 2[

25,

26]. Moreover, utilizing raw materials from bio-based sources (example: bio-epoxides from seed oils, polyols from castor oil etc.) enables the introduction of biogenic carbon into the product life cycle ultimately resulting in a carbon footprint reduction[

5,

27]. Further, wide approval and standardization of such PCR by competing manufacturers would be critical to level the field of sustainable product development.

In summary, PCR provides an agreed–upon framework for measuring the environmental impacts of a product based on a defined set of criteria, which allows the manufacturers to conduct LCA of their products in a standardized way, and publish this information in an EPD, if they so choose, including a separate PCF report. PCF and EPD thus help companies differentiate their products in the marketplace and meet sustainability goals.

Deep Dive into Bio-Based/Biomass/Bio-Attributed Approaches

There are always a couple of terms that keeps dangling when a discussion arises on polymer sustainability, specific to biobased components in products[

28]. Some of these terms are bio-based, biomass, mass balance approach, biogenic CO

2, negative carbon footprint and bio-attributed components. This section discuss each of the topics in detail, trying to untie the knots of terminology-based entanglement. Biogenic CO

2 uptake usually refers to the CO

2 captured from the atmosphere by the biomass/plant during the photosynthesis process across its growth cycle[

29]. Negative product carbon footprint would then imply a net removal of CO

2 from cradle to gate based after factoring in the biogenic CO

2 uptake[

30]. It would mean that the transformation of biomass into products signifies a net CO

2 extraction through its storage in the final product[

31]. Use of actual biobased/recycled raw materials for numerous polymer applications like coatings, composites, tires are the most straight forward route[

32,

33]. Examples include seed oil/vegetable oil-based polymer components, UV cured systems, recycled tires, natural fibers in composites etc.[

4,

34,

35]. With standardize guidelines like the ASTM D6866 (biobased organic carbon content of the product by an

14C isotope quantification method[

36,

37,

38]) and ISO standards (ISO 16620), there exists methodologies to evaluate the biobased content of a polymer product. In regard to official certifications, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has instituted the bio-preferred program or biobased label in the US that follows the ASTM 6866 testing guidelines[

39]. In Europe, the, TUV Austria and DIN CERTCO certification bodies follow the

14C carbon dating based EN 16640, CEN 16,137 and award eco-label if biobased carbon content is equal to or more than 20% [

12]. However, it is not possible or practical to shift an existing formulation into a complete biobased polymer manufacturing overnight. That’s where mass balance approach plays a key role.

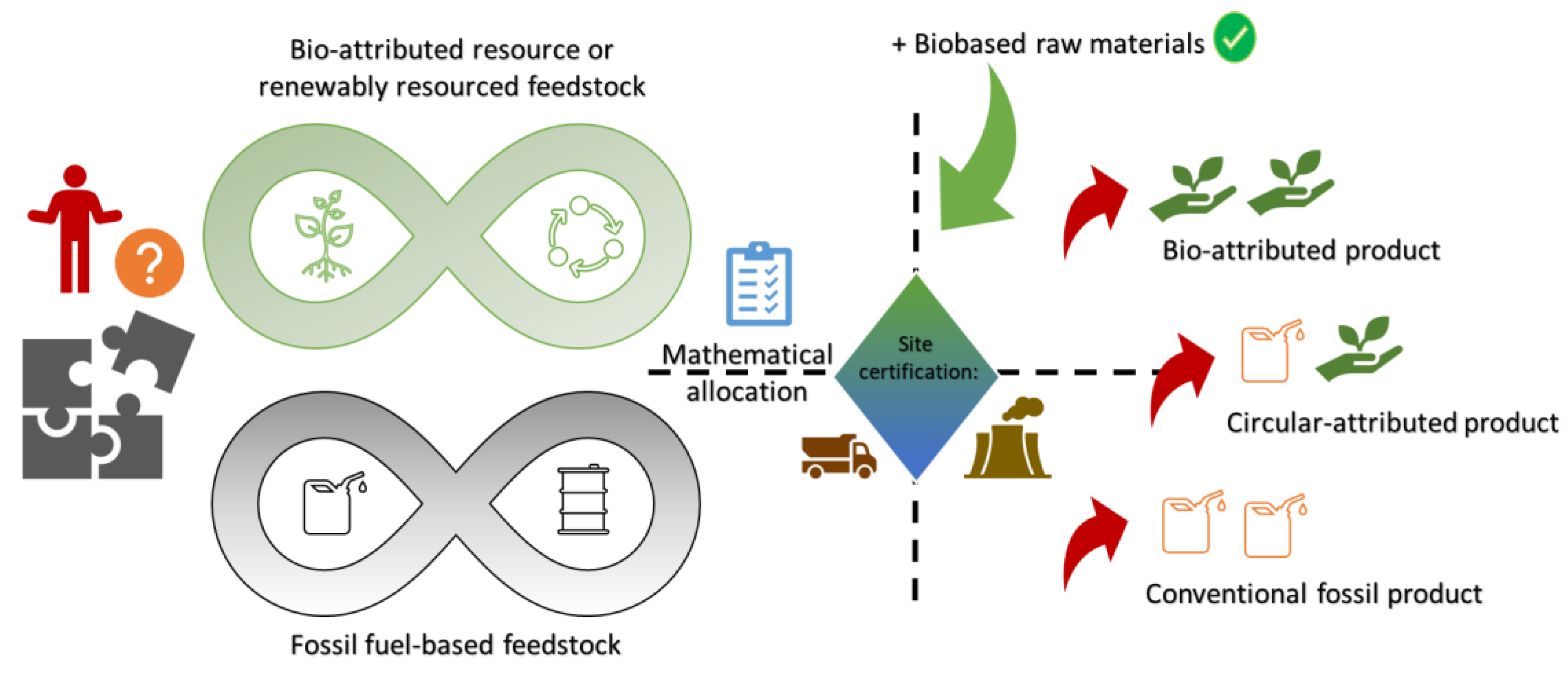

Mass balance approach can be regarded as the first step of a transformative step by step large scale phasing out of fossil based raw materials[

40,

41]. Even in the mass balance approach there are differences depending on the exact terminologies and definitions a manufacturer choose to proceed with and its scope (

Figure 4). One widely accepted mass balance concept is mixing both fossil based and renewable/recycled materials in the existing system and tracking it across the processes allocating them to specific products[

42]. This would mean that there might not be actual biobased components in the final product, but a third party certification would verify the total renewable content that has been allocated in lieu of the initial manufacturing steps[

43]. Initially used in energy sector for electricity and recognized by better cotton initiative, Forest stewardship council etc., the mass balance methodology is now being integrated into the polymer industry[

44]. However, it is crucial that these process allocations are transparent with reliable certifications since complexity rises as a result of differences in applying mass balance method. A point to note here is that terminologies and exact methodology may vary from company to company. Example: 1) Perstorp follows traceable mass balance (chemical and physical traceability) enabling easy identification of recycled or renewable content[

45,

46], 2) mention of “bio-attributed” mass balance (Arkema and Braskem)[

47,

48], and 3) mention of biomass balance (BASF)[

42] and many others. Overall, the underlying principle of mass balance approach is implemented but with specific modifications by the respective company; some of them add the actual biobased component in the later stage of the process whereas others utilize renewable feedstock in the early manufacturing stage or use renewable resources like solar/wind energy in the plant operations. The production route from mass balance bio-attributed or fossil feedstock, have the exact same quality, characteristics, and properties. The use of existing infrastructure and logistics are also advantages. The mass balance method thus traces the material’s footprint across the value chain and allows a gradual transition towards sustainability. Many companies now incorporate a mix of bio-attributed/renewable feedstock in the manufacturing processes coupled with actual biobased raw material in the production formulation. . It is also essential to address some of the possible limitations and challenges associated with implementing such mass balance approaches in practice. It is still a challenge to extract the exact amount of certified material entering into the supply chain[

49] data availability challenges, unit conversion inconsistencies, and levels of uncertainty[

50]. Further, green washing by excessive marketing and promotion without the technical backing, and self-proclaimed “universal” sustainable methodologies are also prevalent[

8,

51]. Regardless, mass balance approach has indeed emerged as the most sought-after sustainable methodologies for developing a sustainable polymer.

Targets, Certifications Within the Polymer Industry

Sustainability certification enables the standardization of sustainable polymer products facilitating guarantee on the credibility of the product claims. It thus helps validate product sustainability claims and can be a strategic move for companies to attain that sustainability marketing edge. It enhances brand reputation, and also incubate a global market where consumers are environmentally conscious. It also helps create a framework to measure and improve sustainability of products and supply chain[

51]. Most importantly, certifications of such a method needs to be transparent, reliable, and applied in all parts of the value chain, all the way back to the point of origin with yearly auditing. The certification bodies that certify the mass balance approach include International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC) PLUS, REDcert etc. focusing on GHGs reduction throughout value chain via sustainable land use, protection of nature, bio-renewable component incorporation and social sustainability intended for commodity manufacturing[

44,

52]. REDcert

2 is specifically used food industry applications sourced from sustainable agricultural raw materials along with biomass derived materials for the chemical industry[

52].

The first and foremost contribution to polymer sustainability is via the supplier of monomers and polymers for product application industries such as coatings, composites etc. which can culminate in most optimized sustainable polymer products for end users[

53,

54]. Thus, it is critical that we understand the sustainability approach of some of such upstream and raw material manufacturing companies[

55,

56,

57]. We identified the major players operating in the polymer manufacturing industry by sifting through market research reports and utilizing the experience in the field.

Table 2 shows the list of companies that were narrowed down based on largest market share, revenue, and diverse polymer products portfolio. Some of the companies listed in the table are pure polymer manufacturers, while others make monomers and chemicals used in polymer manufacturing. In addition to GHG emission targets for Scope 1, 2 and 3, few other important aspect of interest include lower water intake and wastewater, landfilled non-hazardous and hazardous waste reduction etc.[

58,

59,

60,

61]. As observed from the

Table 2, major polymer manufactures are now certified by ISCC+ and incorporate a mixed mass balance approach either by use renewable feedstocks in the plant operating level using mathematical allocation and/or actual biobased components.

Discussion and Future Aspect

The demand for sustainable polymers are surely at its epitome now with trade shows and conferences concentrating on the sustainability topics and introducing new circular economy products[

62]. Sustainable polymer sector is set on impeding growth as part of greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprint reduction, paired with environmentally aware consumer base. Polymer recycling is also an important issue of sustainable development, since the decay period of synthetic polymers is long and plastic pollution is a serious environmental challenge[

63,

64]. There are few challenges that involves a possible recycling difficult by virtue of mixed polymers in the waste recycling streams, inferior properties though new academia researches show comparable properties (recycled PU foam)[

34,

65]. Circular polymer solutions are possible though the increase of resource efficiency via reduction of hazardous chemical use and utilizing more bio-based and recycled systems. Currently, microplastic pollution of the planet is a serious environmental problem[

66,

67]. Considering this ubiquitous microplastic challenge, it’s time to start contemplating the production of polymers from the extraction of raw materials to the disposal of the material (Cradle to grave). End of life evaluation in terms of recycling, reusing, degradability, energy recovery is a key factor to avoid overlooking the LCA[

68].

Sustainability is a necessity for continuous innovation for the future generations and should be regarded just as a trend. Sometimes it’s not just about bio-based raw materials in polymer products but the overall reduction of carbon dioxide emissions in the entire product cycle. PCF and EPD play a major measure in this aspect with the global warming potential and carbon footprint. By reduction of industry’s dependence on virgin fossil raw materials while allowing downstream industries to reduce their Scope 3 emissions, helps create products with a reduced carbon footprint, with no compromise on performance. In a nutshell, for developing a sustainable polymer manufacturing system, one or all aspects of the following need to be considered 1) mass balance approaches with renewable feedstock in the manufacturing process/mathematical allocation and/or followed by use of actual bio-based components, 2) recycling and upcycling of products, 3) use of bio based raw materials as opposed to petroleum derived, lowering carbon footprint 4) a cumulative life cycle analysis (LCA) of products in terms of carbon sequestration, lowest GHG emissions, minimal energy resources used and its degradability/reusability and, 5) establishing measures to prevent further addition of plastic pollution and microplastics due to the new products.

Future developments of a sustainable polymer industry involves materials derived from renewable sources which are further recycled or disposed in environmentally friendly manner. This can be achieved by synthesizing degradable polymer, developing polymers from renewable feedstock, developing reprocessable thermosets, developing novel catalyst catalysts system that can help produce competitive sustainable polymers[

69,

70,

71]. Strong collaboration between academia and industry is also critical for fundamental understanding and efficient commercialization. This contribution attempts to highlight the numerous concepts and terms in the polymer sustainability. We hope that this communication provides a very good foundation for anyone undertaking to formulate sustainable polymers in terms of standards, certifications, methodologies for academia, and industry alike.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, editing, review, and supervision, J.T. and R.S.P.; investigation and writing—original draft preparation, J.J. and M.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- A.K. Mohanty, M. Misra, L.T. Drzal, Natural fibers, biopolymers, and biocomposites, 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. Thomas, R.S. Patil, J. John, M. Patil, A Comprehensive Outlook of Scope within Exterior Automotive Plastic Substrates and Its Coatings, Coatings. 13 (2023). [CrossRef]

- C.P. Constantin, M. Aflori, R.F. Damian, R.D. Rusu, Biocompatibility of polyimides: A mini-review, Materials (Basel). 12 (2019). [CrossRef]

- J. Thomas, R.F. Bouscher, J. Nwosu, M.D. Soucek, Sustainable Thermosets and Composites Based on the Epoxides of Norbornylized Seed Oils and Biomass Fillers, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10 (2022) 12342–12354. [CrossRef]

- J. Thomas, R. Patil, Enabling Green Manufacture of Polymer Products via Vegetable Oil Epoxides, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62 (2023) 1725–1735. [CrossRef]

- S. Grishanov, Structure and properties of textile materials, Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Shamsuyeva, H.J. Endres, Plastics in the context of the circular economy and sustainable plastics recycling: Comprehensive review on research development, standardization and market, Compos. Part C Open Access. 6 (2021) 100168. [CrossRef]

- J. Thomas, R.S. Patil, M. Patil, J. John, Addressing the Sustainability Conundrums and Challenges within the Polymer Value Chain, Sustainability. 15 (2023) 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Business Network, Glossary of sustainability, (2022) 1–7. https://sustainable.org.nz/learn/tools-resources/glossary-of-sustainability/.

- Besley, M.G. Vijver, P. Behrens, T. Bosker, A standardized method for sampling and extraction methods for quantifying microplastics in beach sand, Mar. Pollut. Bull. 114 (2017) 77–83. [CrossRef]

- G.I.C. Righetti, F. Faedi, A. Famulari, Embracing Sustainability: The World of Bio-Based Polymers in a Mini Review, Polymers (Basel). 16 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S. Fadlallah, F. Allais, Sustainability Appraisal of Polymer Chemistry Using E-Factor: Opportunities, Limitations and Future Directions, ACS Symp. Ser. 1451 (2023) 3–30. [CrossRef]

- EPD, Product Category Rule 2020:06, (2020). https://www.environdec.com/pcr-library.

- NSF International, Product Category Rule for Environmental Product Declarations: Fenestration Assemblies, (2023).

- V. Subramanian, W. Ingwersen, C. Hensler, H. Collie, Product Category Rules, (2012) 1–14. http://www.springerlink.com/content/qp4g0x8t71432351/.

- Icca, How to Know If and When it’s Time to Commission a Life Cycle Assessment, Int. Counc. Chem. Assoc. (2013) 20. http://lcacenter.org/lcaxiii/final?presentations/782.pdf.

- UNEP/SETAC Life cycle Initiative, Life Cycle approaches : The road from analysis to practice, Assessment. (2005) 89.

- M. Rangelov, H. Dylla, J. Harvey, J. Meijer, P. Ram, Tech Brief: Environmental Product Declarations - Communicating Environmental Impact for Transportation Products, Fhwa. (2021) 14. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/pavement/sustainability/hif21025.pdf.

- C. Footprint, C. Scope, E. Accounting, The Product Carbon Footprint Guideline for the Chemical Industry Specification for The full PCF Guideline has been launched by TfS, (2024).

- World Resources Institute, World Business Council for Sustainable Development, Product Life Cycle Accounting and Reporting Standard, Septiembre 2011. (2011) 1–148. http://www.ghgprotocol.org/files/ghgp/public/Product-Life-Cycle-Accounting-Reporting-Standard-EReader_041613.pdf.

- S. Gil, Edana Environmental claims guidelines, (2018). https://www.edana.org/docs/default-source/sustainability/edana-guidelines-on-environmental-claims-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=62a27e4f_2.

- P. Operator, D. Holder, D. Number, D. Product, P. Category, P. Operator, T.S. Company, T.P. Gloria, I.E. Consultants, T. Favilla, D. Quality, A. Score, V. Good, Environmental Product Declaration – Product Definition<monospace> </monospace>: Duration <sup>®</sup> Exterior Acrylic is a family of exterior architectural coatings manufactured by The Sherwin-, (2006).

- C. Township, D. Number, D. Product, C. Ultralastik, P. Category, P. Operator, P. Contents, T.P. Gloria, Environmental Product Declaration – COMEX <sup>®</sup> Floor coating system Ultralastik / EFM-104 / EFM-105, (2006).

- F. Clariant, Hostavin 3206 liq *0200, (2023).

- Secretary, Department of Defense Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Off. Under Secr. Def. Acquis. Sustain. (2023). https://media.defense.gov/2023/Jun/16/2003243454/-1/-1/1/2023-DOD-PLAN-TO-REDUCE-GREENHOUSE-GAS-EMISSIONS.PDF.

- J. Heeter, J. McLaren, Innovations in voluntary renewable energy procurement: Methods for expanding access and lowering cost for communities, governments, and businesses, Volunt. Mark. Renew. Energy Status, Trends Options. (2013) 31–83.

- Chakraborty, K. Chatterjee, Polymers and Composites Derived from Castor Oil as Sustainable Materials and Degradable Biomaterials: Current Status and Emerging Trends, Biomacromolecules. 21 (2020) 4639–4662. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Joseph, A.B. Unni, K.S. Joshy, D. Kar Mahapatra, J. Haponiuk, S. Thomas, Emerging Bio-Based Polymers from Lab to Market: Current Strategies, Market Dynamics and Research Trends, C-Journal Carbon Res. 9 (2023). [CrossRef]

- USEPA, Framework for assessing biogenic CO2 emissions from stationary sources, (2014) 63.

- United States Department of State, The Long-Term Strategy of the United States: Pathways to Net-Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2050, Ieee. (2021) 1–63. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/US-Long-Term-Strategy.pdf.

- Thomas, V. Singh, R. Jain, Synthesis and characterization of solvent free acrylic copolymer for polyurethane coatings, Prog. Org. Coatings. 145 (2020) 105677. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. Patil, The Road to Sustainable Tire Materials: Current State-of-the-Art and Future Prospectives, Environ. Sci. Technol. 57 (2023) 2209–2216. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang, J. Thomas, M.D. Soucek, Investigation of UV-curable alkyd coating properties, J. Coatings Technol. Res. (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Thomas, J. Nwosu, M.D. Soucek, Acid-Cured Norbornylized Seed Oil Epoxides for Sustainable , Recyclable , and Reprocessable Thermosets and Composite Application, ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. (2023). [CrossRef]

- R.S. Patil, J. Thomas, M. Patil, J. John, To Shed Light on the UV Curable Coating Technology: Current State of the Art and Perspectives, J. Compos. Sci. 7 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. RameshKumar, P. Shaiju, K.E. O’Connor, R.B. P, Bio-based and biodegradable polymers - State-of-the-art, challenges and emerging trends, Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 21 (2020) 75–81. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Ferreira-Filipe, A. Paço, A.C. Duarte, T. Rocha-Santos, A.L.P. Silva, Are biobased plastics green alternatives?—a critical review, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 (2021). [CrossRef]

- D. Al-Khairy, W. Fu, A.S. Alzahmi, J.C. Twizere, S.A. Amin, K. Salehi-Ashtiani, A. Mystikou, Closing the Gap between Bio-Based and Petroleum-Based Plastic through Bioengineering, Microorganisms. 10 (2022) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- J. Thomas, J. Nwosu, M.D. Soucek, Sustainable biobased composites from norbornylized linseed oil and biomass sorghum fillers, Compos. Commun. 42 (2023) 101695. [CrossRef]

- Wacker AG, the Mass Balance Approach At Wacker, (2023). www.wacker.com/contact.

- Textile Exchange, Preferred Fibers and Materials Definitions, (2023) 1–14.

- D. Circularity, C. Production, Mass Balance Approach, (2025).

- R. Solutions, T. Avenue, F.S. Francisco, Green-e Framework for Renewable Energy Certification, (2017).

- ISCC, Iscc Plus, 3.4 (2023) 1–51.

- Proposal for an EU definition of mass balance, (2023).

- Report, One molecule can change everything, (2021).

- Braskem, Introducing bio-attributed mass balance PP production, (n.d.).

- Arkema, 3 key points about Mass Balance solutions, (n.d.).

- H.K. Jeswani, C. Krüger, A. Kicherer, F. Antony, A. Azapagic, A methodology for integrating the biomass balance approach into life cycle assessment with an application in the chemicals sector, Sci. Total Environ. 687 (2019) 380–391. [CrossRef]

- V. Buytaert, B. Muys, N. Devriendt, L. Pelkmans, J.G. Kretzschmar, R. Samson, Towards integrated sustainability assessment for energetic use of biomass: A state of the art evaluation of assessment tools, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15 (2011) 3918–3933. [CrossRef]

- S. Majer, S. Wurster, D. Moosmann, L. Ladu, B. Sumfleth, D. Thrän, Gaps and research demand for sustainability certification and standardisation in a sustainable bio-based economy in the EU, Sustain. 10 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Frequently Asked Questions ( FAQ ) about the REDcert2 system, (2016) 0–16.

- EPA report, Learn About Sustainability, What is Sustainability ? Why Is Sustainability Important ? How Does EPA Promote, (2022) 1–5.

- J. Thomas, M.D. Soucek, Cationic Copolymers of Norbornylized Seed Oils for Fiber-Reinforced Composite Applications, ACS Omega. 7 (2022) 33949–33962. [CrossRef]

- C. Pasquero, M. Poletto, Deep Green, Proc. 40th Annu. Conf. Assoc. Comput. Aided Des. Archit. 1 (2023) 668–677. [CrossRef]

- WWF Indonesia, Sustainable Sourcing Guideline, (2020).

- USDE, Sustainable Manufacturing and the Circular Economy, (2023) 1–211.

- 2 0 2 3 S U S TA I N A B I L I T Y U P DAT E / P RO G R E S S R E P O RT IN THIS REPORT 2023 LETTER FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, (n.d.).

- E.Q. January, Federal Greenhouse Gas Accounting and Reporting Guidance Council on Environmental Quality, (2016).

- WBCSD, WRI, A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard, Greenh. Gas Protoc. (2012) 116.

- U.S.E.P. Agency, U. S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery Documentation for Greenhouse Gas Emission and Energy Factors Used in the Waste Reduction Model ( WARM ) Construction and Demolition Materials Chapters, (2016).

- Alberta, C. Nrel, S.R. Nrel, T.U. Nrel, H.W. Nrel, P. Lbnl, A.S. Lbnl, I. Ammto, S. Analysis, T. Led, C. Doe, Sustainable and Circular Economy, (2023) 86134.

- S. Madaan, What is Plastic Pollution ?, (2018) 1–6. https://www.eartheclipse.com/environment/environmental-effects-plastic-pollution.html.

- R.A. Wilkes, L. Aristilde, Degradation and metabolism of synthetic plastics and associated products by Pseudomonas sp.: capabilities and challenges, J. Appl. Microbiol. 123 (2017) 582–593. [CrossRef]

- M.B. Johansen, B.S. Donslund, E. Larsen, M.B. Olsen, J.A.L. Pedersen, M. Boye, J.K.C. Smedsgård, R. Heck, S.K. Kristensen, T. Skrydstrup, Closed-Loop Recycling of Polyols from Thermoset Polyurethanes by tert-Amyl Alcohol-Mediated Depolymerization of Flexible Foams, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Thomas, S.K. Moosavian, T. Cutright, C. Pugh, M.D. Soucek, Method Development for Separation and Analysis of Tire and Road Wear Particles from Roadside Soil Samples, Environ. Sci. Technol. 56 (2022) 11910–11921. [CrossRef]

- J. Thomas, T. Cutright, C. Pugh, M.D. Soucek, Quantitative assessment of additive leachates in abiotic weathered tire cryogrinds and its application to tire wear particles in roadside soil samples, Chemosphere. 311 (2023) 137132. [CrossRef]

- P. Ramesh, S. Vinodh, State of art review on Life Cycle Assessment of polymers, Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 13 (2020) 411–422. [CrossRef]

- D.K. Schneiderman, M.A. Hillmyer, 50th Anniversary Perspective: There Is a Great Future in Sustainable Polymers, Macromolecules. 50 (2017) 3733–3749. [CrossRef]

- G.Z. Papageorgiou, Thinking green: Sustainable polymers from renewable resources, Polymers (Basel). 10 (2018). [CrossRef]

- S.A. Miller, Sustainable polymers: Replacing polymers derived from fossil fuels, Polym. Chem. 5 (2014) 3117–3118. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).