1. Introduction

Participation of local people is considered nowadays as condition

sine qua non for successful environmental management of protected areas. McAllister [

1] has emphasized the importance of participatory processes to illustrate the complexity of environmental management issues, the involvement of local people in this process and the promotion of systems for the sustainable and equitable use of natural resources. Participation in decision-making has been encouraged as a means to promote the importance, the legality and enforceability of decisions taken [

2,

3,

4,

5], while, apart from the fact that strengthens the relationship among those who govern and those governed, has essentially the power to alter or even reverse the implementation of a particular policy [

6,

7,

8].

According to Kapoor [

9], some of the basics and advantages of participative management, at least in theory, is that participation helps clear and constant communication and strong relationships between the stakeholders, while encourages their commitment and responsibility. Chambers [

10] describing ways in which “participation” is used, emphasizes on that of an empowering process which enables local people to make their own decisions. Because of the complexity that characterizes the management of protected areas [

11,

12], the effective, efficient and successful involvement of all stakeholders, which requires dealing with potential conflict and achieving consensus [

2], is a real challenge.

Involvement of all stakeholders in the management process is essential [

13,

14,

15]. It has been pointed out that the exclusion of those stakeholders who have strong interests or significant influence in the region has resulted in inability of resolving possible disagreements and conflicts, as there is not enrichment by their empirical knowledge [

16]. As the local community is not homogeneous and has no common standards, interests and patterns of resource use vary widely. To ignore this diversity would prevent the achievement of the conservation and management objectives [

17,

18,

19]. Conflicts and negative attitudes towards protected areas have been recorded in studies worldwide, relating - among others - with different economic interests, aspirations and values of the stakeholders [

2,

20,

21,

22,

23]. A usual “victim” of such negative attitudes is the various management projects running in protected areas that frequently have to struggle with local society’s prejudice. Consideration of the views of the local population in a protected area can provide valuable information base and un-cover beliefs that lead to potential conflicts that need to be addressed. Understanding the views enables the relevant support services to manage conflicts between those involved in managing, in order to achieve consensus [

21,

24,

25,

26]. Therefore, many studies [

24,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35] stress the importance of using the views of the local population as a contribution to the design and implementation of appropriate management measures for sustainable development. More specifically, when it comes to management projects, detection of views could focus on specific proposed actions, allowing for identification of key issues. Complementary to the detection of local people’s opinions, using a tool for predicting environmental attitudes and behaviors could build a sufficient frame to portray local environmental orientation. The New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) is one of the most common tools used worldwide as a measure of ecological beliefs, appraising the degree to which respondents view the world ecologically, thus giving their ecological worldview [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

According to Mannigel [

41], adapted from Borrini-Feyerabend [

42], Pimbert and Pretty [

43], Mattes [

44], and Diamond [

45], there are seven different levels of participation along a continuum, from simple sharing of information to transfer of power and responsibilities (

Table 1). LIFE projects developed across Europe, by virtue of their purpose, allow for effective interventions in terms of environmental planning and management, aiming to a favorable conservation status [

46,

47,

48,

49], and enhancement of local participation is among their main objectives. Given that such projects are of specific duration and also of demonstration and/or implementation role, in most cases raising local people’s participation is achieved through information actions, such as campaigns, falling in the B Level of participation [

28,

42,

43,

44], where information receiving is a unilateral interaction. However, the LIFE project implemented in Skyros Island, Greece, included an action of consultation with local people upgrading the participation directly to Level D, where actively consulting or giving of opinions/views is an engaged interaction with the active exchange of views and opinions. Siebert et al. [

50], analyzing literature from six EU member states in relation with factors affecting European farmers’ participation in biodiversity policies, find that one of the key parts of the literature emphasizes that policy needs to be sensitized to local conditions, and suggest that active acceptance of biodiversity protection can only be achieved through a process of dialogue. Yet, such approach contains the risk of possible strong local disagreement during the consultation meetings, endangering the project communication. For this reason, there is the need for a smoother transition from Level B to level D, incorporating Level C (information seeking or informing represents the canvassing of local stakeholders for factual information by the institution).

The present research suggests a way to facilitate transition from Level B to level D, by incorporating Level C, with aim to pave the way for active consulting and, furthermore, negotiation with local people. More specifically, the research combines detection of the

(a) acceptance of the proposed LIFE project conservation actions by local people - as an indication of their intention to participate - by both informing them and asking for their opinions about specific LIFE project management actions, and

(b) environmental orientation of local people, by measuring endorsement of the New Environmental Paradigm, a widely accepted scale for capturing environmental beliefs.

The aim of the research was to investigate main drivers that could enhance acceptance and local participation in relation to management projects, strengthening the effectiveness of participatory and adaptive management of natural areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Skyros (land area: 20,900 Ha, latitude: 38.854411°, longitude: 24.566986°) is one of the larger islands, located at the centre of the Aegean Archipelago, Greece (Figure 1). It is considered one of the most biodiversity-rich islands in the Aegean Sea and an area of special ecological importance. The Mount Kohylas (792 m) in the southern part of Skyros as well as the islets around the island are designated as sites of the Natura 2000 network (92/43/EEC Directive).

Figure 1.

Map of Skyros island, Greece.

Figure 1.

Map of Skyros island, Greece.

According to the census of 2011, 2994 people live permanently in the island [

51]. Active workforce consists of 1054 individuals (35.20%); the majority of them have been inventoried in the tertiary sector of economy (687 ind., 65.18%), mostly in occupations related to tourism, and a less percentage (135 ind., 12.81%) in the primary sector, i.e., agriculture, livestock husbandry and fishing. Major land uses are pastures (61.18%), forests (26.40%) and agricultural land (5.80%), while settlements and open waters cover the rest land. Skyros holds a remarkable biodiversity, in terms of local or very restricted endemic plants and lizards, mainly related to rocky and coastal habitats, as well as native maple forests (

Acer sempervirens), unique in the Aegean Archipelago. Posidonia meadows (

Posidonia oceanica), a breeding habitat for many species of fish and crustaceans, lie on the sea bottom in the marine coastal zone of the island. Also, the Mediterranean monk seal (

Monachus monachus) is frequently found in sea caves. The southern part of the island with Mount Kohylas (792 m) and the surrounding islets as well as the island’s remaining wetlands are important areas for significant see birds. Eleonora’s falcon (

Falco eleonorae), a globally threatened migratory falcon species, nest at the rocky coastline; the area hosts 8.5% of its national breeding population. The unique miniature Skyrian horse (a protected by EU breed of

Equus cabalus) has been living in a semi-wild state in the southern part of the island. Skyrian horses play a significant role in the rural heritage of the island, since in the past they were used by locals for farming, especially during the summer months. The cultivated land of Skyros still maintains features of traditional agricultural fields of high nature value, while the remaining wetlands of Kalamitsa and Palamari are ecosystems of great significance.

Skyros is considered one of the few islands where the natural environment and biodiversity are maintained to a satisfactory degree of naturalness. This is mainly due to the way of using ecosystems in the region for centuries, namely a direct relationship with the benefits provided by the biodiversity of the island to its residents, in terms of practicing agriculture and livestock husbandry. In recent years, however, as in many other islands, this model began to crumble mainly because of the intense development activity and tourism. Specifically, the construction of the airport of Skyros destroyed the extensive seasonal wetlands and grasslands in the region resulting in disruption of the traditional agro-pastoral model, while the development of mass tourism led to the abandonment of remote agricultural crops and the expansion of residential complexes in the coastal region resulted in the deterioration or destruction of the remaining wetlands on the island. Also, livestock husbandry gradually moved out of the framework of sustainability, as the latter was traditionally perceived by local stock breeders, to uncontrolled (a) increase of livestock numbers, and (b) exploitation of land resources. According to LIFE project, current stocking rates amount to a number which strongly exceeds current grazing capacity [

52]. More heavily, these animal units concentrate into a rather short area of productive rangelands, since pastures previously devoted to livestock husbandry have changed their use during the years. Thus, the main characteristics of current livestock husbandry in Skyros are its traditional base, and its modern uncontrolled implementation, in terms of space and time, which is common to other places of Greece [

53,

54].

On the other hand, Skyros still retains a character and a natural and cultural landscape of unique beauty that attracts good quality tourism, and this increases the value of well-preserved natural ecosystems, biodiversity and landscape for the local community. The nature of the island together with its products could provide significant economic benefit to the local community and the opportunity for a higher standard of living through sustainable tourism.

2.2. Projects Related to Environmental Upgrade

The present study is conducted under the following projects:

“LIFE09NAT/GR/000323”: «Demonstration of the Biodiversity Action Planning Approach, to Benefit Local Biodiversity on an Aegean Island, Skyros» (01/09/2010 – 28/02/2016).

“PAMNATURA” (Participatory and Adaptive Management in NATURA areas): «Model Design for Participatory and Adaptive Management of Greek Natura 2000 sites» (27/08/2012- 26/08/2015).

The LIFE programme is the European Union’s funding instrument for the environment and climate action. The general objective of LIFE programme is to contribute to the implementation, updating and development of EU environmental and climate policy and legislation by co-financing projects with European added value. The aim of the LIFE project in Skyros Island, launched in 2010, was the demonstration of integrated planning methods and management measures in order to maintain and restore the biodiversity of Skyros, thus fulfilling the requirement of the local community for conservation of biodiversity, and for compatible sustainable economic and social development of the area. The LIFE project aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of revitalizing the traditional model of integrated management of agricultural and pasture ecosystems of the island, enhancing at the same time the ecosystems protection and promoting sustainable tourism. To achieve this goal, the project used the approach of the participatory development of a Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP), which is a continuous process of action on the part of the local community of Skyros to ensure that important species, habitats and ecosystems will be preserved for the benefit of people and the environment. The BAP included 6 different thematic Action Plans (AP) developed for the LIFE project, namely the Agro-Pastoral AP, the Wetlands AP, the Maple (Acer sempervirens) stands AP, the Islets AP, the Tourism AP and the Endemic plants AP, developed to analyze and propose conservation actions for the island’s important habitats and species.

The aim of the «PAMNATURA» project, launched in 2012, under the aegis of the European Union and the General Secretariat for Research and Technology (Greek Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs), was to develop an integrated model that facilitates the activation and involvement of local stakeholders in the management process design, enhancing participatory and adaptive management. This model was developed through primary social research in Skyros and Andros islands and the Thessaly plain, as a flexible and useful tool in planning participatory and adaptive management of protected areas. The project focused on management projects that were running in each area. In the case of Skyros Island, the “PAMNATURA” project detected acceptance of the LIFE project management actions by local people, together with application of the NEP scale.

2.3. Questionnaire’s Structure

The questionnaire was constructed to record the local acceptability of the LIFE project proposed actions as well as to measure the ecological attitudes using the revised NEP scale [

37,

55]. The questions were grouped into three thematic sections: (i) socio-demographic characteristics, (ii) LIFE project conservation proposals, and (iii) NEP scale items. All questions were closed-ended. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample were described through gender, age, education level and occupation of the respondents.

Regarding the LIFE project conservation proposals, they were derived from the 6 different thematic Action Plans developed in the frame of the project. Three categories related to protection and promotion of the natural capital of the island were set, corresponding to three important aspects that have to be detected in terms of local views, in order the LIFE project to be strengthened. These categories were: a) nature protection, b) agro-pastoralism, and c) ecotourism. The “nature protection” category consisted of questions regarding impose of stricter protection measures in Kochilas mountain and wetlands. The “agro-pastoralism” category comprised questions about the farming activity on the island, such as the re-cultivation of local traditional crop varieties, such as local variety of Vicia faba (“fava”) and the restarting of the agro-pastoral cooperative. Finally, the “ecotourism” category included questions about the eco-touristic emergence of the local wetlands and the further enhancement of the Skyrian horse. For each question or statement there was a 5-point scale, starting from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.

The New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale, originally constructed by Dunlap and VanLiere [

38] as having 12 items, is now a 15-item questionnaire designed to address the five facets of an ecological worldview [

37]. These facets are: a) reality of limits to growth, b) anti-anthropocentrism, c) fragility of nature’s balance, d) rejection of exemptionalism, and e) the possibility of an eco-crisis. The 15 items of the revised NEP scale were accurately translated in Greek, maintaining the facets of an ecological worldview that are designed to address. For each question or statement there was a 5-point Likert scale, starting from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. Agreement with the eight odd-numbered items and disagreement with the seven even-numbered items indicate pro-NEP responses (

Table 4).

2.4. Sampling–Data Analysis

About 40 pilot questionnaires were applied on a small sample of the population, to check their clarity, identify possible shortcomings or errors and calculate the time required to complete them.

The final questionnaires were applied using the method of simple random sampling. A large number of questionnaires (165) were completed through personal interviews, in public buildings, shops, recreation areas and open spaces. The interview lasted approximately 20′-30′. A number of questionnaires (50) were distributed to the respondents. The process of sampling was carried out in two phases, in November and December 2012.

Following the results of descriptive analysis, the questions of the three different categories of the LIFE project actions were grouped to form three new respective variables, with acceptable Cronbach’s alphas. The questions of the NEP scale were also grouped, reversing the scale for the seven even-numbered questions, with acceptable Cronbach’s alpha, which suggests that the use of the NEP scale as a single measure is basically reasonable. Correlation among different variables was detected, by calculation of the Pearson r.

This way, four distinct dependent variables were formed: (a) Single NEP score, (b) Nature protection, (c) Agro-pastoralism, and (d) Ecotourism. These variables were correlated (Pearson r) to each other as well as to the independent variables corresponding to the social characteristics of the sample (Gender, Age, Education level and Occupation). Additionally, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to detect possible impact of specific occupation (agro-pastoralism) to the dependent variables.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

The total number of questionnaires was 200. A number of 165 questionnaires were completed through personal interviews and 35 questionnaires were returned after distributing (50 were distributed, response rate=70%). The sample corresponds approximately to 7% of the total population of Skyros (National Statistical Service of Greece, Census 2011).

Of them, 63% were male and 37% female (

Table 2). There was adequate representation of the different age classes, as well as the different levels of education. As regards occupation, about one third of the sample work in the primary sector exclusively or not (mainly in agriculture and livestock husbandry, rather than fishing), a large percentage are civil servants, while the majority of the sample work in the private sector (employees, merchants).

3.2. Acceptability of the LIFE Project Actions by Local People

The majority of the sample generally agrees with the LIFE project proposed actions, though there ap-pears notable disagreement or neutrality regarding specific actions (

Table 3).

Among the questions of Nature protection category, the highest mean scores were recorded for those regarding the protection of coastal marine areas as important habitat for breeding fish and seabird colonies, as well as the delineation and enhancement of wetlands for the benefit of migratory birds and riparian vegetation. However, remarkable percentages (12-15%) of the sample were not sure or took no position (nor agreement, nor disagreement) for all the five questions of this category.

As regards the Agro-pastoralism category, the highest mean scores were recorded for the questions about the re-cultivation of local traditional varieties (including both fodder crops and other varieties, like fava beans) and the activation of the local Shepherd Cooperative. The only question of this category that scored under 4 (3,90), was that concerning the proposal of the gradual reduction in the number of sheep until it reaches about 75% of the current number. Regarding answers to the latter question, further statistical analysis showed that there is not significant differentiation (p>0.05) between farmers and the rest of the sample.

As for the Ecotourism category, all three questions reached really high scores.

3.3. The NEP Scores

Agreement with the eight odd-numbered items and disagreement with the seven even-numbered items indicate pro-environmental views (

Table 4). The highest mean scores were recorded for items 3 and 7 related to fragility of nature’s balance and anti-anthropocentrism, respectively; the vast majority of the sample believes that human interference with nature often produces disastrous consequences, as well as that plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist. The lowest mean score was recorded for item 6, which was designed to address the facet of recognition of limits to growth and was the only item which scored below 2.50. According to this, the majority of the sample seems to believe that the earth has plenty of natural resources if people just learn how to develop them. Items 1, 4, 10, 11 and 14 scored from 2.50 to 3.50, indicating neither agreement nor disagreement. Items 1 and 11 were designed to address the facet of limits to growth. Items 4 and 14 were designed to address the facet of human exemptionalism, while item 10 the possibility of an eco-crisis.

Table 4.

Percentage distributions and means for the responses to the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale.

Table 4.

Percentage distributions and means for the responses to the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale.

| |

Responses (%)* |

Mean |

| Statement |

SA |

A |

U |

D |

SD |

| |

(%) |

|

| 1. We are approaching the limit of the number of people the earth can support |

18 |

33 |

14 |

26 |

9 |

3.25 |

| 2. Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs |

1 |

4 |

7 |

37 |

51 |

4.33 |

| 3. When humans interfere with nature, it often produces disastrous consequences |

58 |

37 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

4.50 |

| 4. Human ingenuity will ensure that we do NOT make the earth unlivable |

6 |

13 |

23 |

38 |

20 |

3.50 |

| 5. Humans are severely abusing the environment |

35 |

52 |

6 |

5 |

2 |

4.13 |

| 6. The earth has plenty of natural resources if we just learn how to develop them |

45 |

34 |

5 |

11 |

6 |

1.98 |

| 7. Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist |

60 |

35 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

4.51 |

| 8. The balance of nature is strong enough to cope with the impacts of modern industrial nations |

2 |

7 |

13 |

48 |

30 |

3.97 |

| 9. Despite our special abilities, humans are still subject to the laws of nature |

39 |

48 |

4 |

7 |

1 |

4.19 |

| 10. The so-called “ecological crisis” facing humankind has been greatly exaggerated |

12 |

16 |

16 |

39 |

17 |

3.34 |

| 11. The earth is like a spaceship with very limited room and resources |

14 |

43 |

17 |

20 |

6 |

3.39 |

| 12. Humans were meant to rule over the rest of nature |

4 |

10 |

14 |

49 |

24 |

3.80 |

| 13. The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset |

31 |

49 |

9 |

9 |

2 |

3.99 |

| 14. Humans will eventually learn enough about how nature works to be able to control it |

5 |

21 |

24 |

41 |

9 |

3.28 |

| 15. If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe |

43 |

47 |

6 |

3 |

1 |

4.28 |

3.4. Correlation between Acceptability of the LIFE Project Actions and the Single NEP Scale Score

The questions of the three categories of the LIFE project actions were grouped and mean scores emerged for each category, with acceptable Cronbach’s alphas, forming four distinct variables: (a) Single NEP score, (b) Nature protection, (c) Agro-pastoralism, and (d) Ecotourism (

Table 5).

The sample seems to largely agree with the LIFE project proposals, noting high scores (>4.0) for all the three categories of proposed actions (

Table 5). With slight difference, the actions related to ecotourism scored higher than those related to agro-pastoralism and nature protection. Cronbach’s alpha for all the NEP scale questions was 0.63, which suggests that the use of the NEP scale as a single measure is basically reasonable.

Correlation between the Single NEP score and the acceptability of the different categories of the proposed actions resulted significant, regarding all the three different categories (p<0.001). Calculation of Pearson r showed almost the same moderate correlation between the Single NEP score and the Nature protection and Agro-pastoralism, while correlation between the NEP score and the Ecotourism was rather weaker (

Table 6).

3.5. The Single NEP Score and the Acceptability of the LIFE Project Actions in Relation to the Characteristics of the Sample

Possible relationship between the single NEP scale score and the acceptability of the LIFE project actions with the demographic data of the sample was detected. Gender and age were not found to significantly differentiate the sample’s perceptions regarding both the single NEP scale score and the acceptability of the LIFE project actions. However, statistical analysis showed that the education level of the sample correlates weakly to the single NEP score, as well as to the acceptability of the Nature protection and the Agro-pastoralism variables (

Table 7). Specifically, the higher the educational level the higher the NEP score and the approval of the proposed actions related to the protection of nature and the agro-pastoral issues. No significant correlation was found for the Ecotourism variable.

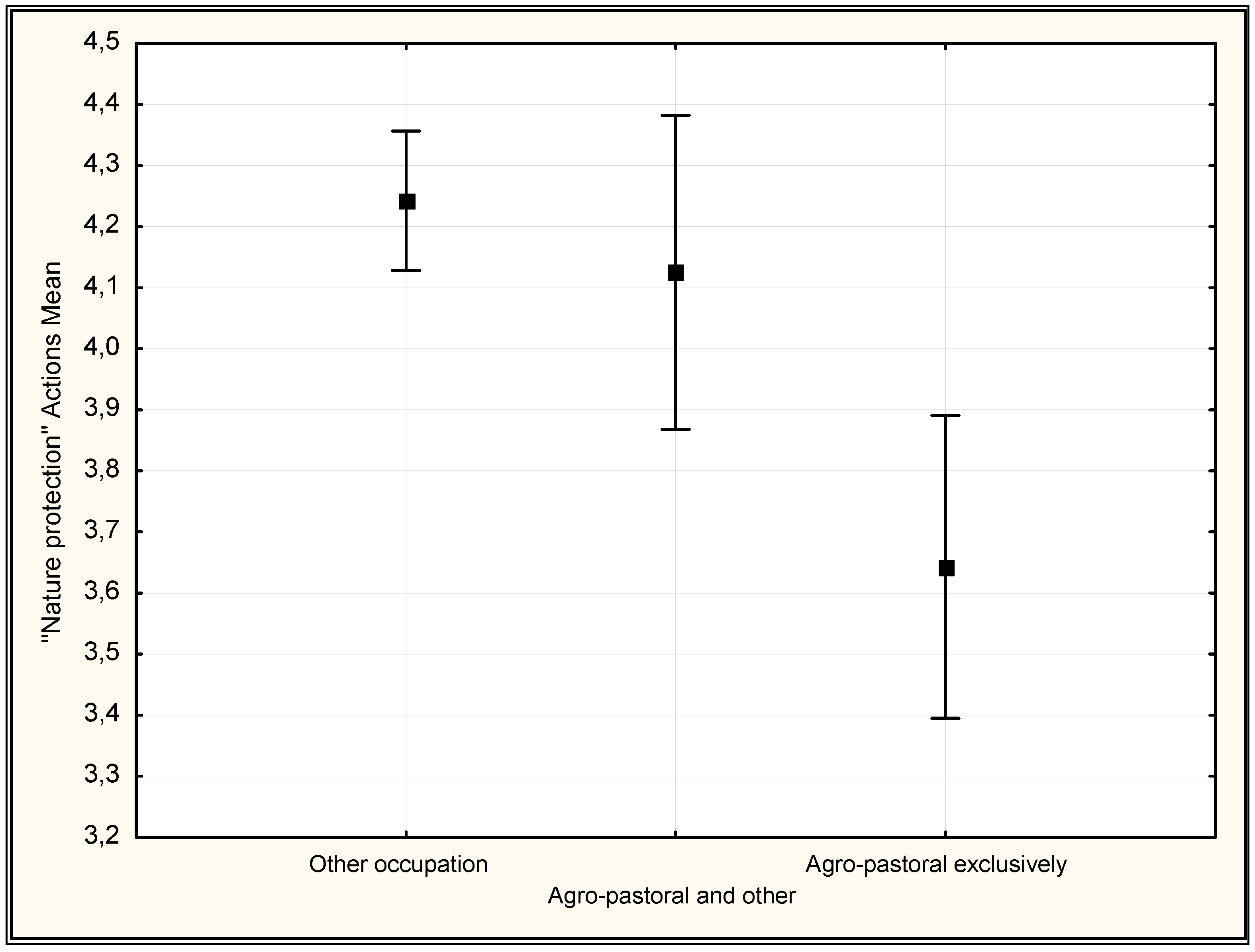

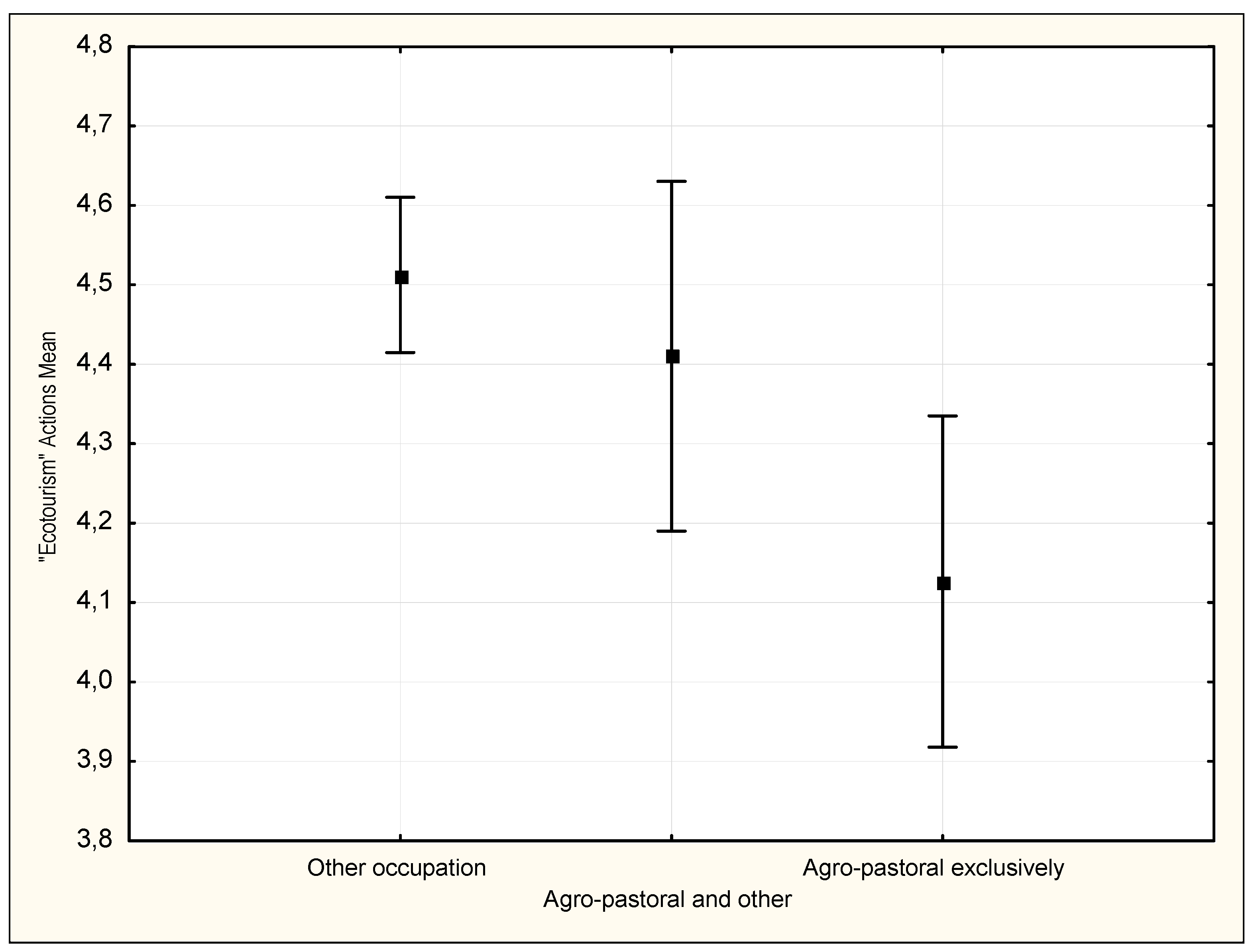

Moreover, considering that people who work in farming and livestock husbandry - of the main stakeholders in the area - are considered to be more or less influenced by the proposed actions, further statistical analysis was carried out to detect any relationship between the single NEP scale score and the acceptability of the LIFE project actions with the relative occupation. In the island, it is usual for people who work in the agro-pastoral sector to work, also, in different sector. For this reason, we grouped occupation of the sample into three groups: those who work in the agropastoral section exclusively, those who work in other section in parallel with agro-pastoralism, and those who work in different sector. The results showed that those who are exclusively farmers scored lower and significantly differentiated from the rest of the sample, as regards the Nature protection and the Ecotourism variables (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of occupation (working in the agro-pastoral section or not) in the Nature protection variable (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Effect of occupation (working in the agro-pastoral section or not) in the Nature protection variable (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Effect of occupation (working in the agro-pastoral section or not) in the Ecotourism variable (p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Effect of occupation (working in the agro-pastoral section or not) in the Ecotourism variable (p<0.01).

4. Discussion

The results showed that the majority of the sample agrees with all the three categories of the LIFE proposed actions, studied in the present research, though there appears notable disagreement or neutrality regarding specific actions. With slight difference, the actions related to ecotourism scored higher than those related to agro-pastoralism and nature protection.

The respondents disagreed or did not take place in notable percentages (8% and 15% respectively) regarding the proposed action about integration of Mount Kohylas’ sites in protection regime with stricter regulations, concerning the questions of Nature protection category. Also, remarkable percentages of the sample (12-15%) chose the “nor agree, nor disagree” answer for all the five questions of this category, implying possible caution about the proposed protection measures. Skyros is designated as one of the receptor islands of the Aegean Sea, where a major renewable development process of 9 wind farms establishment was to take place. The investment involved the installation of 111 wind turbines, under environmental permit procedure, distributed in an area of 2602 ha in Mount Kohylas, i.e., more than 60% of the protected Natura 2000 site. Given the high economic interest anticipated from the investment, reluctance about topics related to the protection of nature is partly understandable and justified. Reluctance seems to be further amplified by the interests related with agro-pastoralism, as additional analysis revealed; those who are exclusively farmers scored lower and significantly differentiated from the rest of the sample regarding the Nature protection proposed actions. Conflicts and negative attitudes towards protected areas have been documented in studies worldwide, related to different economic interests, aspirations, and values of the management shareholders [

2,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The declaration of an area as protected is connected to concerns on the part of those residents that base their livelihood on natural resources, resulting in the adoption of a not-so-positive attitude towards protection [

2,

56,

57,

58]. This is also the case in Skyros island, though it has to be pointed out that farmers may score lower in comparison with the rest of the sample, but their total mean score is high, implying approval of the proposed actions. Siebert et al. [

50] reviewing publications and research reports from six EU member states in relation with factors affecting European farmers’ participation in biodiversity policies, suggested that economic interests are an important, but not the only, determining factor for farmers’ decision-making.

However, when it comes for the actions related to ecotourism activities, the respondents seem to be more receptive as they strongly advocate both the actions relevant to the wetlands, together with the action about the Skyrian horse. Those who are exclusively farmers scored lower in comparison with the rest of the sample, implying less interest in ecotourism activities, though sufficiently high. One of the main elements of successful participatory planning of ecotourism is empowering local communities by linking economic benefits to conservation [

59]. Furthermore, from the Agro-pastoralism category, the questions about the re-cultivation of local traditional varieties and the activation of the local Shepherd Cooperative scored the highest means, with no significant differentiation between farmers and other professionals. This wide acceptance could be attributed to the economic dimension, inherent with the above proposed actions. It seems that an eco- and agro-tourism perspective along with local agro-pastoral development is really appealing to the respondents. This outcome is associated with the possibility of applying participatory and adaptive management in the area, implying willingness for active participation, as the above-mentioned actions are to be performed by the locals themselves.

Henle et al. [

47] argue that conflicts generated from the need to secure biodiversity should be solved by implementing creative management. The latter is based on open and creative partnerships between all parts that have interests on natural resources [

60]. Such approach demands combined actions to exploit information stemmed from the different perceptions of causes, pathways, and consequences and to create joint initiatives. In this respect, three types of conflict reconciliation strategies may be built [

47], (a) regulatory, related to institutional means, (b) participatory, to include interactions with local perceptions into active management processes, and (c) incentives, i.e., compensation means and windows for economic return. Complementary to the latter, Bartkowski and Bartke [

61], reviewing empirical studies of European farmers’ decision-making, pointed out the significant influence of economic incentives on farmers’ decision-making, considering that farmers are also, entrepreneurs.

From the Agro-pastoralism category, the gradual reduction in the number of livestock was the proposed action that scored the least, compared to the other actions of this category. A notable proportion (12%) disagreed with this proposed action, while 16% of the sample seemed to be cautious. However, further statistical analysis regarding this action showed no differentiation between the answers of farmers and the rest of the sample. Extensive livestock husbandry is deeply rooted in the professional life of Skyrians. For centuries, there were three castes in Skyros, those engaged in sea-related professions, those in agricultural activities and those in livestock husbandry. The latter were forming the caste of “tsompanides”, which was the base of traditional Skyrian culture, and livestock was the centre of this culture [

62,

63]. Disagreement and prejudice, regarding the livestock reduction, expressed in remarkable percentages by the sample (and not particularly by farmers), could reflect this traditional culture aspect - on the side of the general population - in combination with the farmers’ concerns. The negative effects on main stakeholders’ activities in protected areas and the relative arising reactions and conflicts have been reported by numerous works [

21,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68].

As a common rule, conflicts are generated when a specific conservation measure touches the economic interests of local people. For example, Reading et al. [

69] reported several areas of conflicts between pastoralism and conservation in the rangelands of Mongolia. Similarly, several reactions from local herders to the introduction of conservation measures for wild fauna have been recorded worldwide (e.g., [

70,

71,

72,

73]. Often, the reduction of conflicts (human activities that oppose to the conservation measures) are found in the core of several conservation programs, like the one for brown bear in the National Park of Abruzzo - Italy (LIFE09 NAT/IT/000160 project). For this reason, specific guidelines for the prevention and management of conflict were realized [

74].

As regards the NEP scale questions, it is noteworthy that all the NEP questions addressing the facet of “reality of limits to growth” scored under 3.5. More specifically, the majority of the sample seems to believe that the earth has plenty of natural resources if people just learn how to develop them, while large percentages of the respondents disagree with the statements that we are approaching the limit of the number of people the earth can support, and that the earth is like a spaceship with very limited room and resources. From the above it could be drawn that those low means concerning the facet of “reality of limits to growth” could be probably associated to some extent to the reluctance expressed regarding the questions about “Nature protection”, reflecting a rather “loose” conception of the capacity and the extent of natural resources utilization, either assisting the relevant reluctance about “Nature protection” issues or originated from it.

The single NEP score of the sample was rather high, implying pro-environmental beliefs. The NEP scale score has been used worldwide in the prediction of behavior and support for conservation programs and management policy and has been found to correlate significantly to behavioral intentions [

40,

75,

76,

77,

78]. Xiao et al. [

79] found the NEP scale as the most powerful predictor of “environmental concern”. Dunlap and Jones [

80] defined “environmental concern” as “the degree to which people are aware of problems regarding the environment and support efforts to solve them and/or indicate a willingness to contribute personally to their solution”. Xiao et al. [

79] also reported that in most cases, studies employing the NEP scale as a predictor of specific environmental beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors, found that the NEP has considerable power in predicting pro-environmental behaviors. Moreover, in the case of Skyros island, the positive correlation between this high single NEP score and the mean scores in all the different categories of the proposed actions further strengthens the possible relationship between pro-environmental beliefs and predicting of behavioral intentions.

The fact that the educational level of the sample positively correlates both to the single NEP score and the acceptability of the proposed actions related to the protection of nature and the agro-pastoral issues, emphasizes the possible significant role of environmental education in raising awareness of local people, that could lead to better understanding of environmental management actions and consequently to higher approval of them. Studies have reported positive correlation between education level and the NEP [

81,

82,

83,

84], as well as the role of education in shaping views related to environmental conservation [

11,

27,

50,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91].

5. Conclusions

The NEP scale, in agreement with the literature worldwide, could be a reliable predictor tool for pro-environmental beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. In Skyros island the rather high NEP score correlates positively to the high recorded local reception of the proposed management actions, confirming the above. Use of the NEP scale during designing a management project could be a first detection step for making the “environmental profile” of local society.

High mean scores regarding all the different categories of the proposed management actions reflect a generally positive attitude towards the relative management project and implies a proper basis for developing cooperation with the inhabitants. There seems to be fertile ground for flourishing of the local Shepherd Cooperative, as well as, for re-cultivating local varieties, while prospect of ecotourism was also well received by locals; agro- and eco-tourism actions exhibit good perspectives for the local economy. In this sense, implementation of actions related directly or indirectly to economic activities, that are more likely to be adopted by the local community, e.g., fava bean cultivation and reconstitution of traditional terraces should be promoted and possibly combined into the agrotourism portfolio. Linking financial incentives to environmental conservation could motivate local societies to be actively involved in management projects. The message of this study regarding the revitalization of local Shepherd Cooperative is not only of local importance; it may serve as a model to be adopted by other local shepherd communities throughout Greece. Indeed, the active connection of rural people in nature conservation projects that simultaneously safeguard or even increase their income and societal status looks like a win-win condition.

Old-fashioned mentalities regarding livestock husbandry are still traceable in the local society, reflected in the reluctance (though, by a small percentage of the sample and - additionally - not exclusively farmers) of the adoption a 1/4 reduction of the livestock capital to restore the pastureland. Such mentalities are deeply rooted in the traditional bonds local people still retain with the activity of stocking animals. The modern appreciation of values that natural environment generates may serve as a boost to accept balanced livestock numbers in respect to carrying capacity of rangelands. Further, it is expected that the inclusion of this professional activity into a developmental framework based on promotion of natural resources will give new perspectives in this activity. Thus, it is expected that nature’s conservationism may serve as a vehicle to shift towards sustainable land use practices.

Respect for local tradition could enhance local participation. When developing management projects, preservation of traditional activities that connect local people with their past is crucial, as it makes them feel safeguarding cultural values, preserving this way the unique local character amid new proposed approaches and actions. Environmental education together with consultation and interactive informing, in the frame of management projects design and implementation, could also enhance local participation. In the case of Skyros island, it is essential the proposed project actions related (directly or not) to protection measures and restrictions to be effectively communicated, so the main stakeholders (farmers, shepherds and fishermen) to be well-informed, in parallel with environmental education activities. This way, misunderstanding, reluctance as well as possible conflicts will be avoided, facilitating the projects’ objectives but also helping in addressing people’s prejudice about protected area.

From the above, it could be argued that Skyros offers an appropriate social background for applying participatory and adaptive management and implementing conservation programs.

Author Contributions

The authors have contributed to the following areas of the study “Conceptualization, VK; methodology, VK; formal analysis, VK, MV; investigation, VK; resources, VK; data curation, VK, MV; writing—original draft preparation, VK, MV; writing—review and editing, VK, MV; visualization, VK, MV; supervision, VK; project administration, VK; funding acquisition, VK.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Projects “LIFE09NAT/GR/000323”, “PAMNATURA”.

Data Availability Statement

Data and material is available upon request.

Acknowledgments:

The present study was conducted under the following projects: • “LIFE09NAT/GR/000323”: «Demonstration of the Biodiversity Action Planning approach, to benefit local biodiversity on an Aegean island, Skyros» (01/09/2010 - 28/02/2016) - European Commission, Municipality of Skyros, Hellenic Ornithological Society, Society for the Environment and Cultural Heritage. • “PAMNATURA” (Participatory and Adaptive Management in NATURA areas): «Model Design for Participatory and Adaptive Management of Greek Natura 2000 sites» (27/08/2012- 26/08/2015) - European Union, General Secretariat of Research and Technology (Greek Ministry of Culture, Education and Religious Affairs), Nature Conservation Consultants (NCC). Authors express their gratitude to anonymous reviewers for the significant improvement of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McAllister, K. Understanding Participation: Monitoring and Evaluating Process, Outputs and Outcomes; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S. Barriers to nature conservation in Germany: a model explaining opposition to protected areas. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2001, 21, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G.A.; Vargas-Chaves, I. Participation in environmental decision making as an imperative for democracy and environmental justice in Colombia. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 2018, 9, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.H.; Koski, J.; Verkuijl, C.; Strambo, C.; Piggot, G. Making Space: How Public Participation Shapes Environmental Decision-Making; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carrick, J.; Bell, D.; Fitzsimmons, C.; Gray, T.; Stewart, G. Principles and practical criteria for effective participatory environmental planning and decision-making. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, T.M. Citizen participation: conflicting interests in state and national agency policy making - Policy lessons for a new century. The Social Science Journals 1999, 36, 441–458. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, B. Evaluating public participation in environmental policy-making. Journal of US-China Public Administration 2012, 9, 407–423. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari, R.; Tonkaboni, M.A. Citizen participation policy making for environmental issues: A literature review. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University 2020, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, I. Towards participatory environmental management? Journal of Environmental Management 2001, 63, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, R. Paradigm shifts and the practice of participatory research and development. In Power and Participatory Development. Theory and Practice; Nelson, N., Wright, S., Eds.; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1994; pp. 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Lu, Y.; Fu, B. Local people’s perceptions as decision support for protected area management in Wolong Biosphere Reserve, China. Journal of Environmental Management 2006, 78, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birendra, K.C. Complexity in balancing conservation and tourism in protected areas: Contemporary issues and beyond. Tourism and Hospitality Research 2022, 22, 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Linkov, I.; Satterstrom, F.K.; Kiker, G.; Batchelor, C.; Bridges, T.; Ferguson, E. From comparative risk assessment to multi-criteria decision analysis and adaptive management: Recent developments and applications. Environment International 2006, 32, 1072–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloni, C.; Daminabo, I.; Alexander, B.C.; Bakpo, M.T. The importance of stakeholders involvement in Environmental Impact Assessment. Resources and Environment 2015, 5, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Kohl, C.; Rebelo da Silva, N.; Schiemann, J.; Spök, A.; Stewart, R.; Sweet, J.B.; Wilhelm, R. A framework for stakeholder engagement during systematic reviews and maps in environmental management. Environmental Evidence 2017, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkerden, G. Adaptive management planning projects as conflict resolution processes. Ecology and Society 2006, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource. Conservation World Development 1999, 27, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, T.; Renard, Y. Beyond community involvement: lessons from the insular Caribbean. Parks 2002, 12, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Ling, G.H.T. Factors influencing collective action of gated communities: a systematic review using an SES framework. Open House International 2023, 48, 325–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.P.; Nielson, E. Indigenous people and co-management: implications for conflict management. Environmental Science and Policy 2001, 4, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.S.; Maikhuri, R.K.; Saxena, K.G. Local people’s knowledge, aptitude and perceptions of planning and management issues in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India. Environmental Management 2003, 31, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechciński, M.; Tusznio, J.; Grodzińska-Jurczak, M. Protected area conflicts: a state-of-the-art review and a proposed integrated conceptual framework for reclaiming the role of geography. Biodiversity and Conservation 2019, 28, 2463–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Conflict and Conservation Nature in a Globalised World; Report No.1; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Trakolis, D. Local people’s perceptions of planning and management issues in Prespes Lakes National Park, Greece. Journal of Environmental Management 2001, 61, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kite-Powell, A.C.; Harding, A.K. Nitrate contamination in Oregon Well Water: Geologic variability and the public’s perception. Journal of the American Water Resources Association 2006, 42, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierman, L.; Ledwith, A.; Lynch, R. Design teams management of conflict in reaching consensus. International Journal of Conflict Management 2020, 31, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newmark, W.D.; Leonard, N.L.; Sariko, H.I.; Gamassa, D.M. Conservation attitudes of local people living adjacent to five protected areas in Tanzania. Biological Conservation 1993, 63, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. Adaptive management in transboundary protected areas: the Bialowieza National Park and Biosphere Reserve as case study. Environmental Conservation 2000, 27, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakolis, D. Perceptions, preferences, and reactions of local inhabitants in Vikos-Aoos National Park, Greece. Environmental Management 2001, 28, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, R.; Tisdell, C. Comparison of rural and urban attitudes to the conservation of Asian elephant in Sri Lanka: empirical evidence. Biological Conservation 2003, 110, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, K.; Vogiatzakis, I.N. Nature protection in Greece: an appraisal of the factors shaping integrative conservation and policy effectiveness. Environmental Science and Policy 2006, 9, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allendorf, T.D. Residents’ attitudes toward three protected areas in southern Nepal. Biodiversity and Conservation 2007, 16, 2087–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerford, E. Understanding why landholders choose to participate or withdraw from conservation programs: A case study from a Queensland conservation auction. Journal of Environmental Management 2014, 141, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, M.; Warriner, G.; Farmer, J.; Larson, B. Private landowners and environmental conservation: A case study of social-psychological determinants of conservation program participation in Ontario. Ecology and Society 2017, 22, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milán-García, J.; Uribe-Toril, J.; Ruiz-Real, J.L.; de Pablo Valenciano, J. Sustainable local development: An overview of the state of knowledge. Resources 2019, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E. The New Environmental Paradigm scale: From marginality to worldwide use. The Journal of Environmental Education 2008, 40, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: a revised NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The New Environmental Paradigm. The Journal of Environmental Education 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J. Renewing the New Environmental Paradigm Scale: the Underlying Diversity of Contemporary Environmental Worldviews. Ph.D. thesis, University of Hawaii at Mānoa, 2017; 117p. [Google Scholar]

- Ntanos, S.; Kyriakopoulos, G.; Skordoulis, M.; Chalikias, M.; Arabatzis, G. An application of the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) scale in a Greek context. Energies 2019, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannigel, E. Integrating parks and people: How does participation work in protected area management? Society & Natural Resources 2008, 21, 498–511. [Google Scholar]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G. Collaborative Management of Protected Area: Tailor the Approach to the Context; IUCN: Gland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pimbert, M.P.; Pretty, J.N. Parks, people and professionals: Putting ‘participation’ into protected area management. In Social Change and Conservation. Environmental Politics and Impacts of National Parks and Protected Areas; Ghimire, K.B., Pimbert, M.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, 1997; pp. 297–330. [Google Scholar]

- Mattes, A. Partizipation der Bevölkerung am Management von zwei Ausgewählten Schutzgebieten in Minas Gerais, Brasilien. Der PRA-Ansatz als Beginn einer Zusammenarbeit Zwischen Schutzgebietsverwaltung und Bevölkerung in der Pufferzone; Diplomarbeit, Faculty of Forestry, Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg: Freiburg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, N. Participatory Conservation for Protected Areas. An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Sources (1996–2001); World Bank: Washington, DC, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chassany, J.-P.; Rulleau, B.; Salles, J.M. Evolution of Biodiversity Policies on the Territory of the Cevennes National Park (France): Some Contractual Approach Issues, Working Papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute, 2004.

- Henle, K.; Alard, D.; Clitherow, J.; Cobb, P.; Firbank, L.; Kull, T.; McCracken, D.; Moritz, R.F.A.; Niemela, J.; Rebane, M.; Wascher, D.; Watt, A.; Young, J. Identifying and managing the conflicts between agriculture and biodiversity conservation in Europe - A review. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2008, 124, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Quetier, F.; Marty, P.; Lepart, J. Farmers management strategies and land use in an agropastoral landscape: roquefort cheese production rules as a driver of change. Agricultural Systems 2005, 84, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, L.; Bollen, A.; Delbaere, B.; Houston, J.; Sliva, J.; Velghe, D. Bringing Nature back through LIFE - The EU LIFE Programme’s Impact on Nature and Society; Delbaere, B., Ed.; European Commission, Environment Directorate-General, 2020.

- Siebert, R.; Toogood, M.; Knierim, A. Factors affecting European farmers’ participation in biodiversity policies. Sociologia Ruralis 2006, 46, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Census 2011, https://www.statistics.gr/en/2011-census-pop-hous.

- Fotiadis, G.; Vrahnakis, Μ.S. Action Plan for Agropastoral Ecosystems. Final Report, LIFE09NAT/GR/000323 - “Demonstration of the Biodiversity Action Planning approach, to benefit local biodiversity on an Aegean island, Skyros», 81 p. (+ ANNEXES) (in Greek), 2012.

- Chouvardas, D.; Vrahnakis, M.S. A semi-empirical model for the near-future evolution of the lake Koronia landscape. Journal of Environmental Protection and Ecology 2009, 10, 867–876. [Google Scholar]

- Vrahnakis, M.S.; Fotiadis, G.; Pantera, A.; Goudelis, G.; Papadopoulos, A.; Papanastasis, V.P. Floristic diversity of valonia oak silvopastoral woodlands in Greece. Agroforestry Systems 2014, 88, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. The new ecological paradigm in social-psychological context. Environment and Behavior 1995, 27, 723–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortenkamp, K.M.; Moore, C.F. Ecocentrism and anthropocentrism: Moral reasoning about ecological commons dilemmas. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2001, 21, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Carrus, G.; Martorella, H.; Bonnes, M. Local identity processes and environmental attitudes in land use changes: The case of natural protected areas. Journal of Economic Psychology 2002, 23, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Ruda, A.; Blahová, M. Stakeholders’ Perception of the impact of the declaration of new protected areas on the development of the regions concerned, Case study: Czech Republic. Forests 2021, 12, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B. Local participation in the planning and management of ecotourism: A revised model approach. Journal of Ecotourism 2003, 2, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; O’Riordan, T. Enhancing biodiversity and humanity. In Biodiversity, Sustainability and Human Communities: Protecting Beyond the Protected; Riordan, T.O., Stoll-Kleemann, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2002; pp. 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski, B.; Bartke, S. Leverage points for governing agricultural soils: A review of empirical studies of European farmers’ decision-making. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faltaits, M. Skyrian Smihtes and Tsompanides, Publication of Historical and Folklore Society of Skyros, (in Greek), 1976.

- Kamilaki-Polymerou, A.; Karamanes, E. Folklore: Traditional Culture; Hellenic Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs: Athens, 2008. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- West, P.C.; Brechin, S.R. National parks, protected areas and resident peoples: a comparative assessment and integration. In Resident Peoples and National Parks, University of Arizona Press; West P.C., Brechin S.R., Eds.; Tucson, 1991.

- Kurek, W.; Faracik, R.; Mika, M. Ecological conflicts in Poland. GeoJournal 2001, 507, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weladji, R.B.; Tchamba, M.N. Conflict between people and protected areas within the Bénoué Wildlife Conservation Area, North Cameroon. Oryx 2003, 37, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmer, H.; Rauschmayer, F.; Klauer, B. How to select instruments for the resolution of environment conflicts? Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, N.; Yenilmez Arpa, N. Guidelines for Engaging Stakeholders in Managing Protected Areas, FAO and MAF, Ankara 2022. [CrossRef]

- Reading, R.P.; Bedunah, D.J.; Amgalanbaatar, S. Conserving biodiversity on Mongolian rangelands: Implications for protected area development and pastoral uses. USDA Forest Service Proceedings 2006, RMRS-P-39, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tamang, B.; Baral, N. Livestock depredation by large cats in Bardia National Park, Nepal: Implications for improving park–people relations. International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management 2008, 4, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riginos, C.; Porensky, L.M.; Veblen, K.E.; Odadi, W.O.; Sensenig, R.L.; Kimuyu, D.; Keesing, F.; Wilkerson, M.L.; Young, T.P. Lessons on the relationship between livestock husbandry and biodiversity from the Kenya. Long-term exclosure experiment (KLEE). Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice 2012, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalida, A.; Campión, D.; Donázar, J.A. Vultures vs livestock: conservation relationships in an emerging conflict between humans and wildlife. Oryx 2014, 48, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, M. Herders’ aversion to wildlife population increases in grassland ecosystem conservation: Evidence from a choice experiment study. Global Ecology and Conservation 2021, 30, e01777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulli, C.; Latini, R.; D’ Amico, D.; Sammarone, L. Protocolo Operative Sperimentale per la Prevenzione e la Gestione del Fenomeno degli orsi Confidentie/o Problematici nell’ Area del Parco Nazionale D’ Abruzzo, Lazzio e Molise, LIFE09 NAT/IT/000160 project, 2012.

- Lopez, A.G.; Cuervo-Arango, M.A. Relationship among values, beliefs, norms and ecological behaviour. Psicothema 2008, 20, 623–629. [Google Scholar]

- Rauwald, K.S.; Moore, C.F. Environmental attitudes as predictors of policy support across three countries. Environment and Behavior 2002, 34, 709–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.E.; Bord, R.J.; Fisher, A. Risk perceptions, general environmental beliefs, and willingness to address climate change. Risk Analysis 1999, 19, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Zelezny, L.C. Values and proenvironmental behavior: A five-country survey. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 1998, 29, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Dunlap, R.E.; Hong, D. Ecological worldview as the central component of environmental concern: Clarifying the role of the NEP. Society & Natural Resources 2019, 32, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Jones, R. Environmental concern: Conceptual and measurement issues. In Handbook of Environmental Sociology; Dunlap, R.E., Michelson, W., Eds.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, 2002; pp. 482–542. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, M.; Hoban, T.J.; Clifford, W.B.; Brant, P. Social and demographic influences on environmental attitudes. Southern Rural Sociology 1997, 13, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Miao, H. Environmental attitudes of stakeholders and their perceptions regarding protected area-community conflicts: A case study in China. Journal of Environmental Management 2010, 91, 2254–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, H.D.; Pereira, L.N. Measuring the level of endorsement of the new environmental paradigm: A transnational study. Dos Algarves: A Multidisciplinary e-Journal 2014, 23, 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- Atav, E.; Altunoğlu, B.D.; Sönmez, S. The determination of the environmental attitudes of secondary education students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2015, 174, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallo, E.A.; Jacobson, S.K. Local communities and protected areas: attitude of rural residence towards conservation and Machalilla National Park, Ecuador. Environmental Conservation 1995, 22, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, J.N.; Heinen, J.T. Does community-based conservation shape favorable attitudes among locals? An empirical study from Nepal. Environmental Management 2001, 28, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y.; Xu, S.S.W. Stifled Stakeholders and Subdued Participation: Interpreting Local Responses Toward Shimentai Nature Reserve in South China. Environmental Management 2002, 30, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleftoyanni, V.; Abakoumkin, G.; Vokou, D. Environmental perceptions of students, farmers and other economically active members of the local population near the protected area of Axios, Loudias, Aliakmonas estuaries, in Greece. Global Nest Journal 2011, 13, 288–299. [Google Scholar]

- Hazzah, L.; Dolrenry, S.; Kaplan, D.; Frank, L. The influence of park access during drought on attitudes toward wildlife and lion killing behaviour in Maasailand, Kenya. Environmental Conservation 2013, 40, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowersd, A.W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological Conservation 2020, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masona, D. The influence of environmental education on conservation in secondary schools in Mvomero District. East African Journal of Education Studies 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).