Submitted:

27 May 2024

Posted:

29 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 37.10.Ty

1. Introduction

1.1. Applications of Mathieu (Hill) Equation in Case of Electrodynamic Ion Traps. Nonlinear (Anharmonic) Traps. Kicked Mathieu-Duffing (Parametric) Oscillator

1.2. Mass Spectrometry with Ion Traps. Late Developments

1.3. Ultraprecise Optical Atomic Clocks Based on Ultracold Ions. Current Directions of Action

1.4. Structure of the Paper

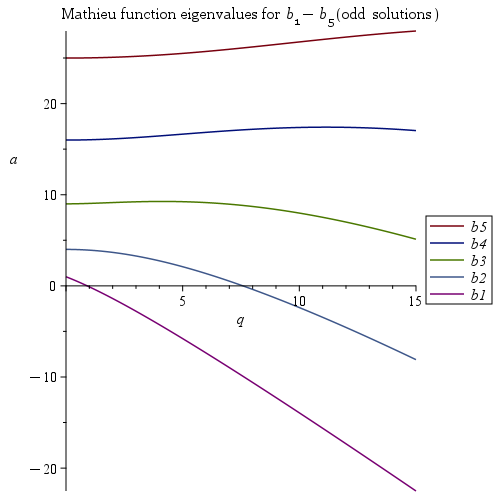

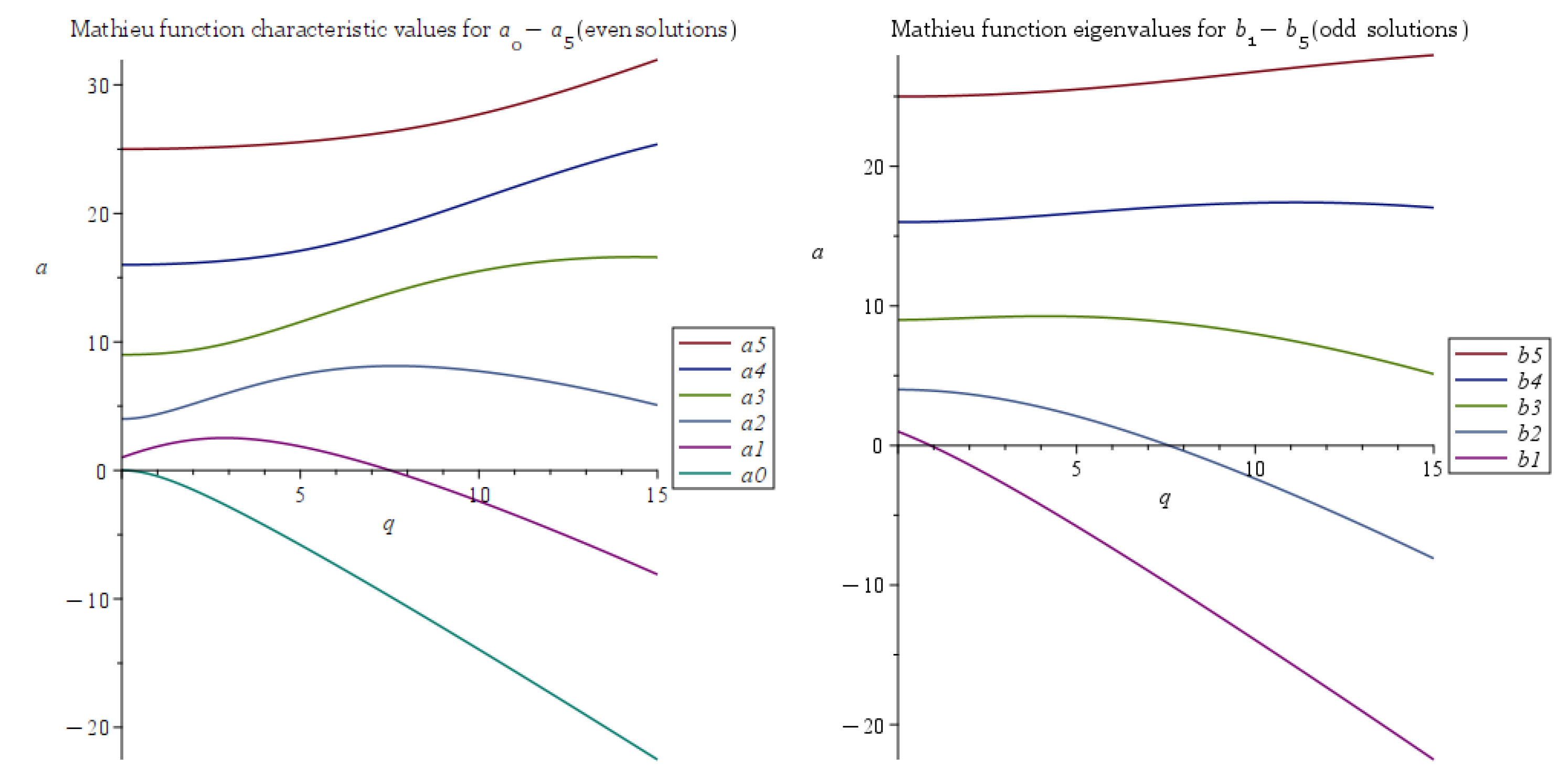

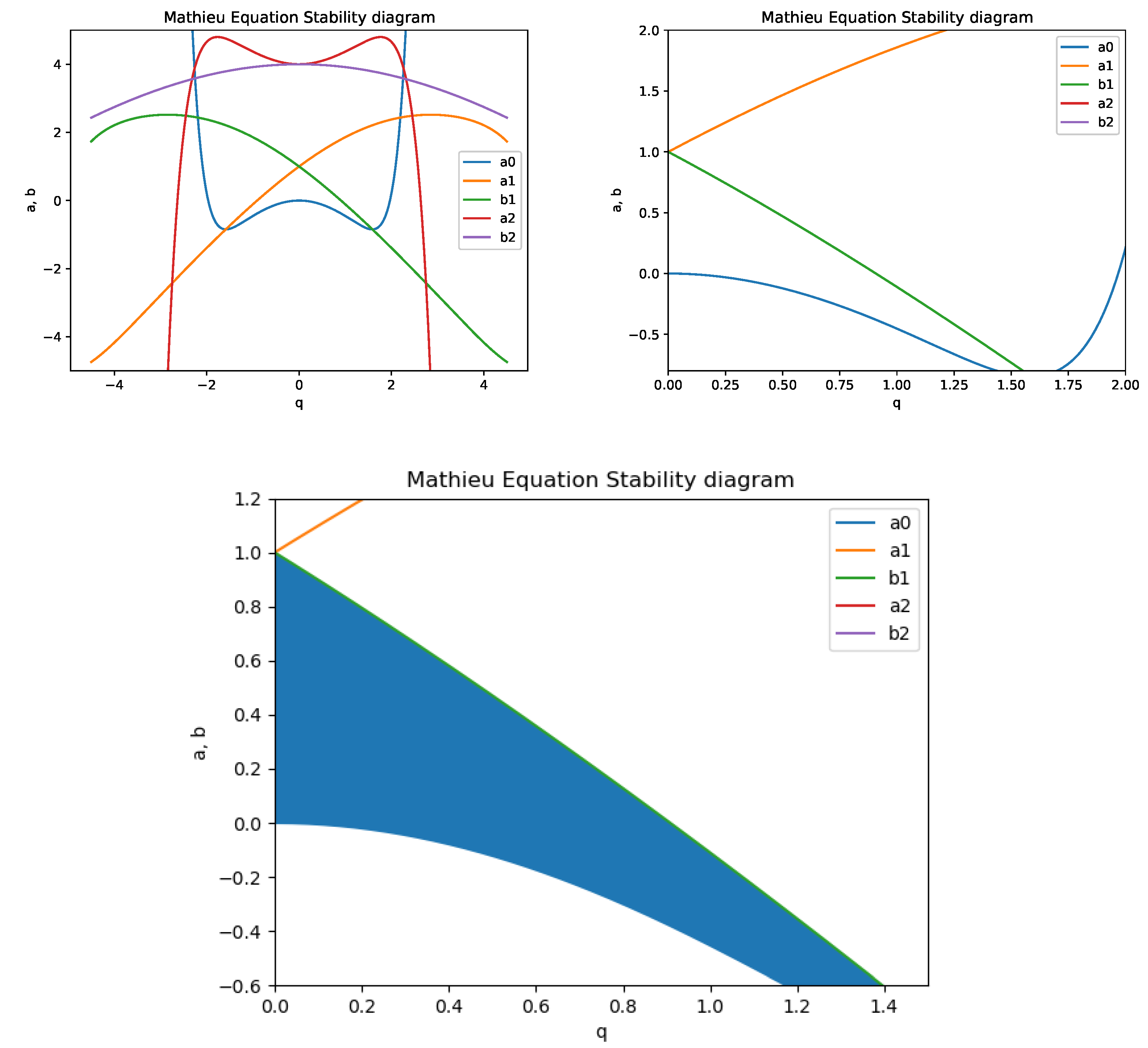

2. Mathieu-Hill Equations

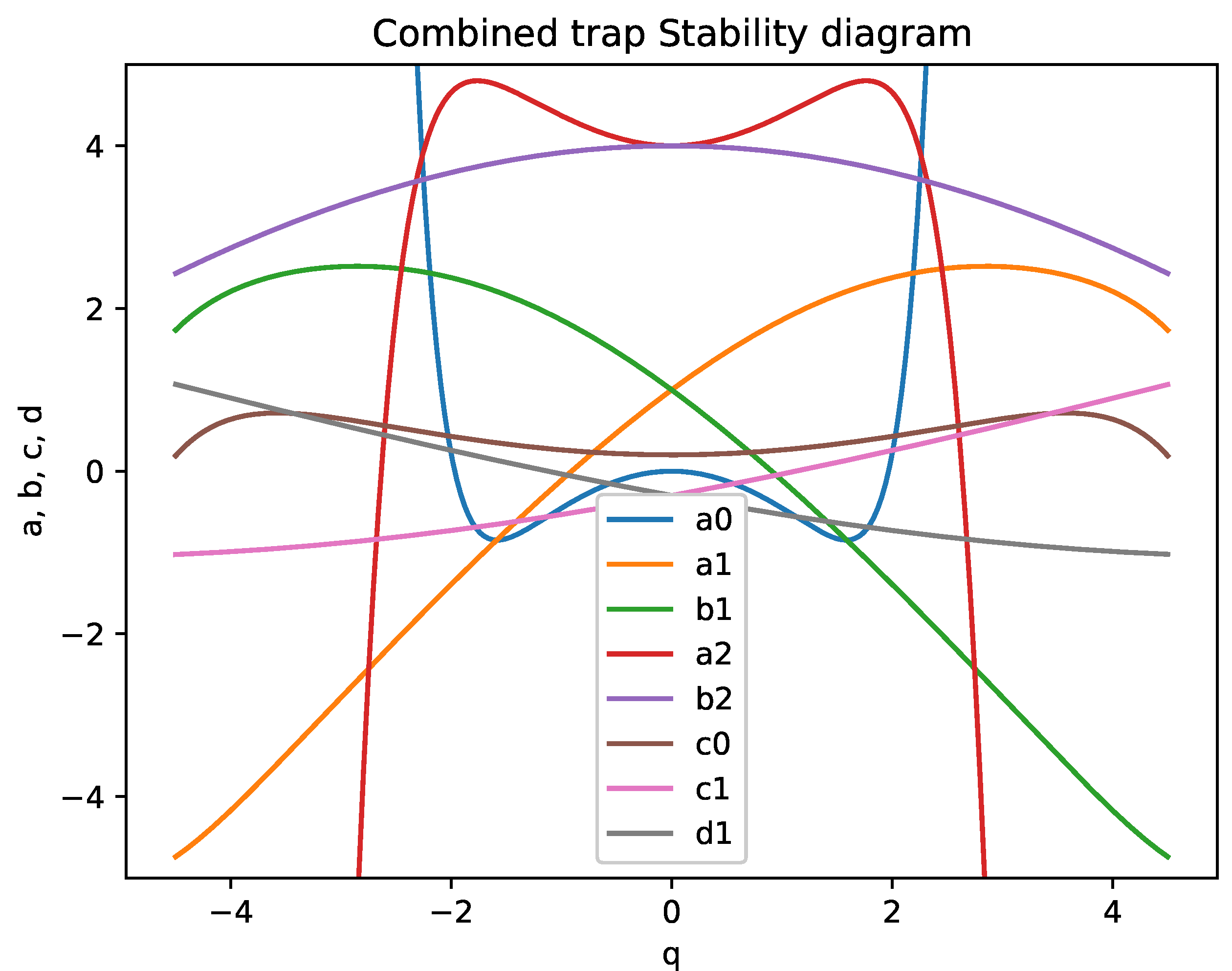

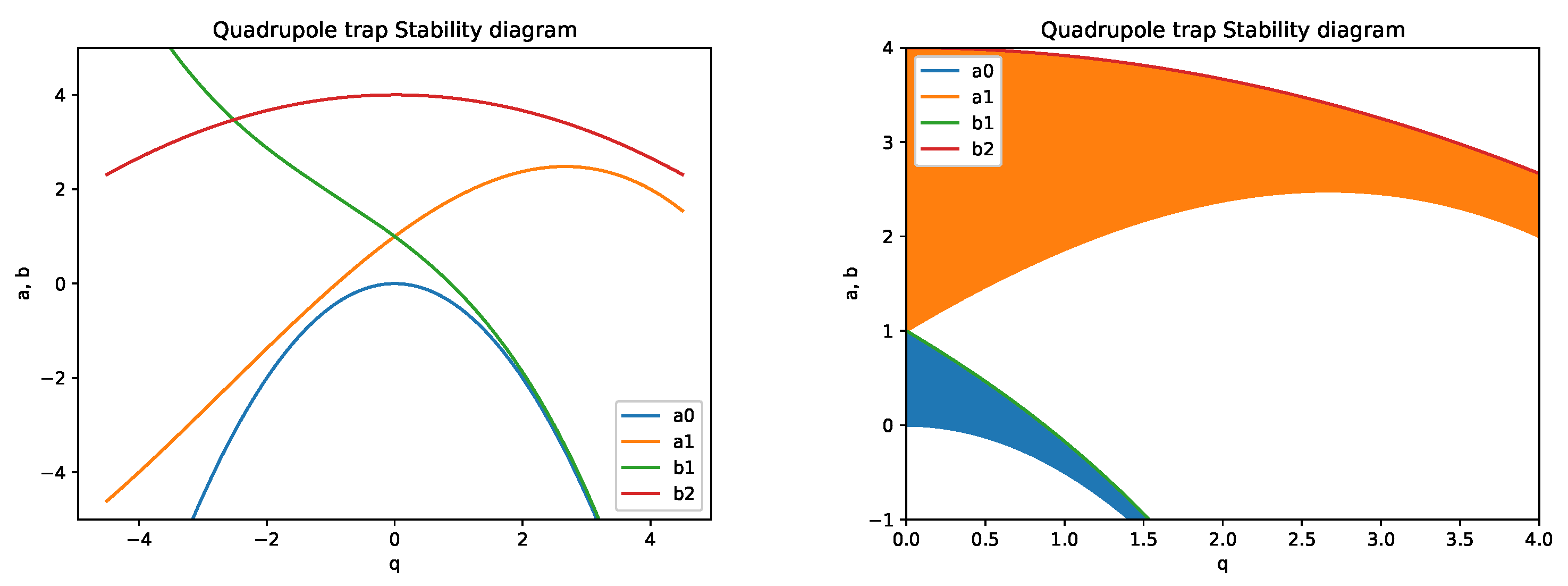

3. Stability of the Solutions of the Mathieu-Hill Equation for a Trapped Ion

3.1. the Kicked Damped Parametric Oscillator

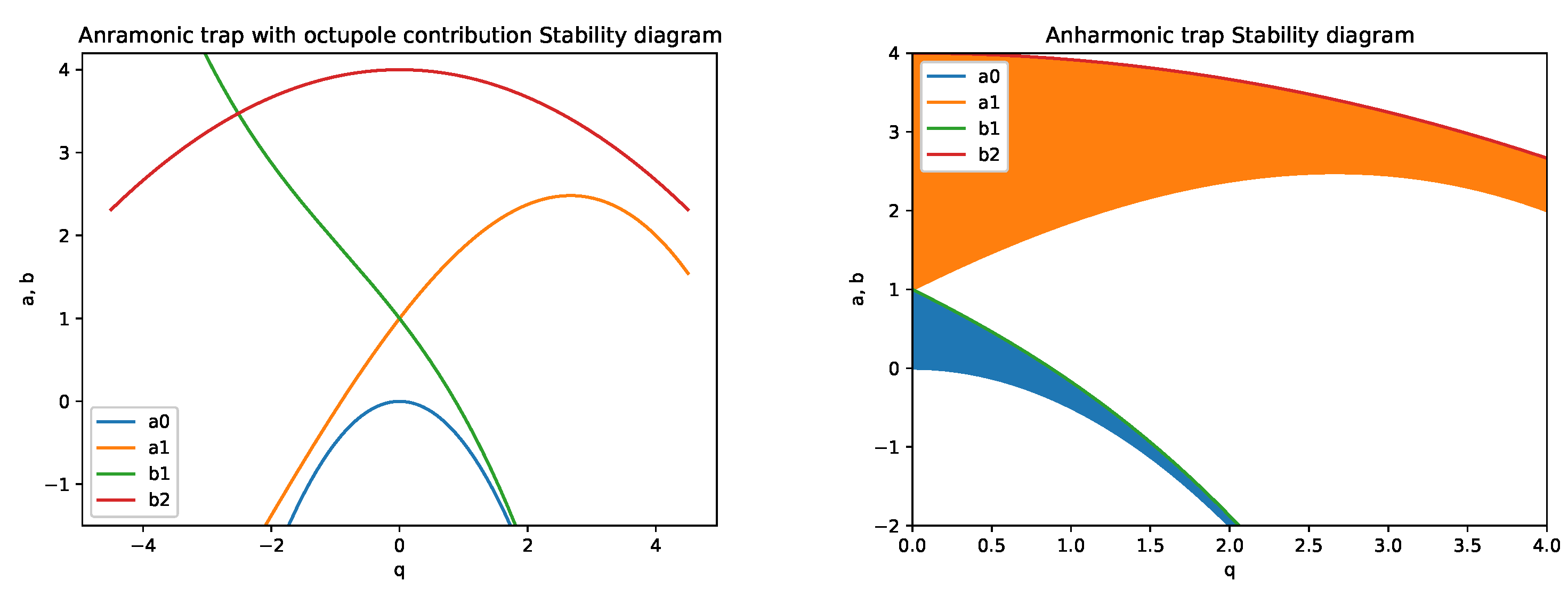

4. Anharmonic Corrections for Electrodynamic (Paul) Traps. Perturbation Method Analysis

4.1. Solutions of the Mathieu Equation

4.2. the Frontiers of the Stability Diagram for the Mathieu Equation with Nonlinear Term

5. Discussion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | 2-Dimensional |

| 3D | 3-Dimensional |

| BSM | Beyond the Standard Model |

| COTS | Commercial Off-The-Shelf |

| DALI | Development and Advancement of Lunar Instrumentation Program |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DE | Differential Equation |

| DO | Duffing Oscillator |

| DSAC | Deep Space Atomic Clock |

| ENABLE | Environmental Analysis of the Bounded Lunar Exosphere |

| GEO | Geostationary Orbit |

| HB | Harmonic Balance |

| HPM | Homotopy Perturbation Method |

| HO | Harmonic Oscillator |

| LIT | Linear Ion Trap |

| LPT | Linear Paul Trap |

| MOT | Magneto-Optical Trap |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| MSOLO | Mass Spectrometer Observing Lunar Operations |

| NLDE | Non-Linear Differential Equations |

| NME | Nonlinear Mathieu Equation |

| ODE | Ordinary Differential Equation |

| QMS | Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer |

| PKL | Poincaré-Lighthill-Kuo |

| PO | Parametric Oscillator |

| QIT | Quadrupole Ion Trap |

| RF | Radiofrequency |

| RK | Runge-Kutta |

| SI | International System of Units |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SQL | Standard Quantum Limit |

| STP | Standard Temperature and Pressure |

| VIPER | Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover |

Appendix A. Hill’S Method to Find the Solution of the Mathieu Equation

Appendix A.1. Sträng’s Recursion Formula for △0

Appendix B. the Frontiers of the Stability Regions

Appendix C. Solving the Mathieu Equation. Perturbation Theory

Appendix C.1. Perturbation Theory

References

- Nayfeh, A.H.; Sanchez, N.E. Bifurcations in a forced softening duffing oscillator. Int. J. Nonlin. Mech. 1989, 24, 483 – 497. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7462(89)90014-0. [CrossRef]

- Serov, V. Fourier Series, Fourier Transform and Their Applications to Mathematical Physics; Applied Mathematical Sciences, Springer: Cham, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65262-7. [CrossRef]

- Gadella, M.; Giacomini, H.; Lara, L. Periodic analytic approximate solutions for the Mathieu equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 271, 436 – 445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2015.09.018. [CrossRef]

- Rand, R.H. CISM Course: Time-Periodic Systems Sept. 5 - 9, 2016. http://audiophile.tam.cornell.edu/randpdf/rand_mathieu_CISM.pdf.

- Krack, M.; Gross, J. In Harmonic Balance for Nonlinear Vibration Problems; Schröder, J.; Weigand, B., Eds.; Mathematical Engineering, Springer: Cham, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14023-6. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E. Mémoire sur le mouvement vibratoire d’une membrane de forme elliptique. J. Math. Pures Appl. 1868, 13, 137–203.

- Arfken, G.B.; Weber, H.J.; Harris, F.E. In Mathematical Methods for Physicists, 7th ed.; Academic Press: Waltham, 2013; chapter 32, pp. 1 – 29.

- Daniel, D.J. Exact solutions of Mathieu’s equation. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2020, 2020, 043A01. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptep/ptaa024. [CrossRef]

- Brimacombe, C.; Corless, R.M.; Zamir, M. Computation and Applications of Mathieu Functions: A Historical Perspective. SIAM Review 2021, 63, 653 – 720. https://doi.org/10.1137/20M135786X. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.A.; Vogt, N.; Golubev, D.S.; Cole, J.H. Approximate solutions to Mathieu’s equation. Physica E: Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2018, 100, 24 – 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2018.02.019. [CrossRef]

- Corless, R.M. An Hermite–Obreshkov method for 2nd-order linear initial-value problems for ODE. Numer. Algor. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11075-023-01738-z. [CrossRef]

- Butikov, E. Analytical expressions for stability regions in the Ince–Strutt diagram of Mathieu equation. Am. J. Phys. 2018, 86, 257 – 267. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.5021895. [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, I.; Rand, R.; Sah, S.M. Mathieu’s Equation and Its Generalizations: Overview of Stability Charts and Their Features. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2018, 70, 020802. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4039144. [CrossRef]

- Nayfeh, A.H. Introduction to Perturbation Techniques; Wiley Classics Library, Wiley, 2011.

- Doroudi, A. Application of a Modified Homotopy Perturbation Method for Calculation of Secular Axial Frequencies in a Nonlinear Ion Trap with Hexapole, Octopole and Decapole Superpositions. J. Bioanal. Biomed. 2012, 4, 85 – 91. https://doi.org/10.4172/1948-593x.1000068. [CrossRef]

- Jazar, R.N. Perturbation Methods in Science and Engineering; Springer: Cham, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73462-6. [CrossRef]

- El-Dib, Y.O. An innovative efficient approach to solving damped Mathieu–Duffing equation with the non-perturbative technique. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2024, 128, 107590. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.cnsns.2023.107590. [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, N.W. Theory and application of Mathieu functions; Vol. 1233, Dover Publications: New York, 1964.

- Abramowitz, M.; Stegun, I.A., Eds. Mathieu Functions; Vol. 55, Appl. Math. Series, US Dept. of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards: Washington, DC, 1972; chapter 20, pp. 722 – 750.

- Major, F.G.; Gheorghe, V.N.; Werth, G. Charged Particle Traps: Physics and Techniques of Charged Particle Field Confinement; Vol. 37, Springer Series on Atomic, Optical and Plasma Physics, Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1007/b137836. [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.; Porter, R.M. Reduced-quaternionic Mathieu functions, time-dependent Moisil-Teodorescu operators, and the imaginary-time wave equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2023, 438, 127588. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.amc.2022.127588. [CrossRef]

- Orszag, M. Quantum Optics: Including Noise Reduction, Trapped Ions, Quantum Trajectories, and Decoherence, 3rd ed.; Springer Intl. Publishing: Cham, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29037-9. [CrossRef]

- Birkandan, T.; Hortaçsu, M. Examples of Heun and Mathieu functions as solutions of wave equations in curved spaces. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2007, 40, 1105 – 1116. https://doi.org/10.1088/1751-8113/40/5/016. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T.; Perrine, R.P.; Richardson, D.C.; Barnes, R. A SYMPLECTIC INTEGRATOR FOR HILL’S EQUATIONS. Astron. J. 2010, 139, 803. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-6256/139/2/803. [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, A.R. Application of the theory of Hill’s equation to the study of the stability of periodic classical orbits. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 1989, 22, L673. https://doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/22/14/004. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, E.T.; Watson, G.N. In A Course of Modern Analysis, 5th ed.; Moll, V.H., Ed.; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009004091. [CrossRef]

- Gadella, M.; Lara, L.P. A variational modification of the Harmonic Balance method to obtain approximate Floquet exponents. Math. Meth. Appl. Sci. 2023, 46, 8956 – 8974. https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.9029. [CrossRef]

- Knoop, M.; Madsen, N.; Thompson, R.C., Eds. Physics with Trapped Charged Particles: Lectures from the Les Houches Winter School; Imperial College Press & World Scientific: London, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1142/p928. [CrossRef]

- Knoop, M.; Madsen, N.; Thompson, R.C., Eds. Trapped Charged Particles: A Graduate Textbook with Problems and Solutions; Advanced Textbooks in Physics, World Scientific Europe: London, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1142/ q0004. [CrossRef]

- Vasil’ev, I.A.; Kushchenko, O.M.; Rudyi, S.S.; Rozhdestvenskii, Y.V. Effective Rotational Potential of a Molecular Ions in a Plane Radio-Frequency Trap. Tech. Phys. 2019, 64, 1379 – 1385. https://doi.org/10.1134/ S1063784219090202. [CrossRef]

- Kajita, M. Ion Traps; IOP Publishing, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1088/978-0-7503-5472-1. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, M. In Particle Confinement in Penning Traps: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Babb, J.; Bandrauk, A.D.; Bartschat, K.; Joachain, C.J.; Keidar, M.; Lambropoulos, P.; Leuchs, G.; Velikovich, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2024; Vol. 100, Springer Series on Atomic, Optical, and Plasma Physics. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-55420-9. [CrossRef]

- Haroche, S.; Raimond, J.M. Exploring the Quantum: Atoms, Cavities and Photons; Oxford Graduate Texts, Oxford Univ. Press: Clarendon, Oxford, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198509141.001.0001. [CrossRef]

- Vinante, A.; Pontin, A.; Rashid, M.; Toroš, M.; Barker, P.F.; Ulbricht, H. Testing collapse models with levitated nanoparticles: Detection challenge. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 100, 012119. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.100. 012119. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R.; Leduc, M.; Perrin, H., Eds. Ultra-Cold Atoms, Ions, Molecules and Quantum Technologies; EDP Sciences: 91944 Les Ulis Cedex A, France, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1051/978-2-7598-2745-9. [CrossRef]

- Paul, W. Electromagnetic traps for charged and neutral particles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1990, 62, 531 – 540. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.62.531. [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, B.M.; Lynch, S. Investigations on Dynamical Stability in 3D Quadrupole Ion Traps. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11072938. [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, B.M.; Filinov, V.S.; Syrovatka, R.A.; Vasilyak, L.M. The physics and applications of strongly coupled Coulomb systems (plasmas) levitated in electrodynamic traps. Phys. Rep. 2023, 1016, 1 – 103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2023.03.004. [CrossRef]

- Baril, M.; Septier, A. Piégeage des ions dans un champ quadrupolaire tridimensionnel à haute fréquence. Rev. Phys. Appl. (Paris) 1974, 9, 525 – 531. https://doi.org/10.1051/rphysap:0197400903052500. [CrossRef]

- Schulte, M.; Lörch, N.; Leroux, I.D.; Schmidt, P.O.; Hammerer, K. Quantum Algorithmic Readout in Multi-Ion Clocks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 013002. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.013002. [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.; Burgermeister, T.; Kalincev, D.; Didier, A.; Kulosa, A.P.; Nordmann, T.; Kiethe, J.; Mehlstäubler, T.E. Controlling systematic frequency uncertainties at the 10-19 level in linear Coulomb crystals. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 013405. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.99.013405. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Granot, O.; Douglas, D.J. Quadrupole Excitation of Ions in Linear Quadrupole Ion Traps with Added Octopole Fields. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 19, 510 – 519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasms.2007. 12.007. [CrossRef]

- Austin, D.E.; Hansen, B.J.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Z. Multipole expansion in quadrupolar devices comprised of planar electrode arrays. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 295, 153 – 158. Harsh Environment Mass Spectrometry: New Developments and Applications, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2010.05.009. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Shao, R.; Xiong, X.; Fang, X.; Deng, Y.; Xu, W. Characterization of geometry deviation effects on ion trap mass analysis: A comparison study. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2014, 370, 125 – 131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2014.07.014. [CrossRef]

- Reece, M.P.; Huntley, A.P.; Moon, A.M.; Reilly, P.T.A. Digital Mass Analysis in a Linear Ion Trap without Auxiliary Waveforms. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 31, 103 – 108. https://doi.org/10.1021/jasms.9b00012. [CrossRef]

- Nolting, D.; Malek, R.; Makarov, A. Ion traps in modern mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2019, 38, 150 – 168. https://doi.org/10.1002/mas.21549. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.; Mukherjee, M. Non-degenerate dodecapole resonances in an asymmetric linear ion trap of round rod geometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2024, 498, 117217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2024.117217. [CrossRef]

- Kaur Kohli, R.; Van Berkel, G.J.; Davies, J.F. An Open Port Sampling Interface for the Chemical Characterization of Levitated Microparticles. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 3441 – 3445. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem. 1c05550. [CrossRef]

- Harris, W.A.; Reilly, P.T.A.; Whitten, W.B. Detection of Chemical Warfare-Related Species on Complex Aerosol Particles Deposited on Surfaces Using an Ion Trap-Based Aerosol Mass Spectrometer. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 2354 – 2358. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac0620664. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.L.; Wang, C.; Hill, S.C.; Coleman, M.; Beresnev, L.A.; Santarpia, J.L. Trapping of individual airborne absorbing particles using a counterflow nozzle and photophoretic trap for continuous sampling and analysis. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 113507. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4869105. [CrossRef]

- Fachinger, J.R.W.; Gallavardin, S.J.; Helleis, F.; Fachinger, F.; Drewnick, F.; Borrmann, S. The ion trap aerosol mass spectrometer: field intercomparison with the ToF-AMS and the capability of differentiating organic compound classes via MS-MS. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 1623 – 1637. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-1623-2017. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, V.; Stokes, C.; Ferzoco, A. A Linear Ion Trap with an Expanded Inscribed Diameter to Improve Optical Access for Fluorescence Spectroscopy. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 29, 260 – 269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-017-1763-3. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M.V.; Kerecman, D.E. Molecular Characterization of Atmospheric Organic Aerosol by Mass Spectrometry. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2019, 12, 247 – 274. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anchem-061516-045135. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, D.T.; Szalwinski, L.J.; St. John, Z.; Cooks, R.G. Two-Dimensional Tandem Mass Spectrometry in a Single Scan on a Linear Quadrupole Ion Trap. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 13752 – 13762. https://doi.org/10.1021/ acs.analchem.9b03123. [CrossRef]

- Newsome, G.A.; Rosen, E.P.; Kamens, R.M.; Glish, G.L. Real-time Detection and Tandem Mass Spectrometry of Secondary Organic Aerosols with a Quadrupole Ion Trap. ChemRxiv 2020. https://doi.org/10.26434/ chemrxiv.12633836.v1. [CrossRef]

- joo Cho, H.; Kim, J.; Kwak, N.; Kwak, H.; Son, T.; Lee, D.; Park, K. Application of Single-Particle Mass Spectrometer to Obtain Chemical Signatures of Various Combustion Aerosols. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2021, 18, 11580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111580. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.E.; Szalwinski, L.J.; Marsh, B.M.; Wells, J.M.; Cooks, R.G. Immediate and sensitive detection of sporulated Bacillus subtilis by microwave release and tandem mass spectrometry of dipicolinic acid. Analyst 2021, 146, 7104 – 7108. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1AN01796A. [CrossRef]

- Wineland, D.J.; Monroe, C.; Meekhof, D.M.; King, B.E.; Leibfried, D.; Itano, W.M.; Bergquist, J.C.; Berkeland, D.; Bollinger, J.J.; Miller, J. Quantum state manipulation of trapped atomic ions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1998, 454, 411 – 429. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1998.0168. [CrossRef]

- Blaum, K.; Novikov, Y.N.; Werth, G. Penning traps as a versatile tool for precise experiments in fundamental physics. Contemp. Phys. 2010, 51, 149 – 175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107510903387652. [CrossRef]

- Wineland, D.J. Nobel Lecture: Superposition, entanglement, and raising Schrödinger’s cat. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013, 85, 1103 – 1114. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.85.1103. [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, B.M. Squeezed coherent states of motion for ions confined in quadrupole and octupole ion traps. Ann. Phys. (N. Y.) 2018, 388, 100 – 113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aop.2017.11.004. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Jördens, R.; Erickson, S.D.; Wu, J.J.; Bowler, R.; Tan, T.R.; Hou, P.Y.; Wineland, D.J.; Wilson, A.C.; Leibfried, D. Ion Transport and Reordering in a 2D Trap Array. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2020, 3, 2000028. https://doi.org/10.1002/qute.202000028. [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, B.M. Quasienergy operators and generalized squeezed states for systems of trapped ions. Ann. Phys. (N. Y.) 2022, 442, 169826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aop.2022.168926. [CrossRef]

- Häffner, H.; Roos, C.F.; Blatt, R. Quantum computing with trapped ions. Phys. Rep. 2008, 469, 155 – 203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2008.09.003. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, G.; Hess, P.W.; Kaplan, H.B.; Tan, W.L.; Richerme, P.; Becker, P.; Kyprianidis, A.; Zhang, J.; Birckelbaw, E.; Hernandez, M.R.; Wu, Y.; Monroe, C. Cryogenic trapped-ion system for large scale quantum simulation. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2018, 4, 014004. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/aae0fe. [CrossRef]

- Bruzewicz, C.D.; Chiaverini, J.; McConnell, R.; Sage, J.M. Trapped-ion quantum computing: Progress and challenges. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2019, 6, 021314. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5088164. [CrossRef]

- Mokhberi, A.; Hennrich, M.; Schmidt-Kaler, F. Chapter Four - Trapped Rydberg ions: A new platform for quantum information processing. In Adv. In Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Phys.; Dimauro, L.F.; Perrin, H.; Yelin, S.F., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; Vol. 69, pp. 233 – 306. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aamop.2020.04.004. [CrossRef]

- LaPierre, R. Introduction to Quantum Computing; The Materials Research Society Series, Springer: Cham, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69318-3. [CrossRef]

- Reiter, F.; Sørensen, A.S.; Zoller, P.; Muschik, C.A. Dissipative quantum error correction and application to quantum sensing with trapped ions. Nature Comm. 2017, 8, 1822. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01895-5. [CrossRef]

- Fountas, P.N.; Poggio, M.; Willitsch, S. Classical and quantum dynamics of a trapped ion coupled to a charged nanowire. New J. Phys. 2019, 21, 013030. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/aaf8f5. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.; Schmidt, P.O. Quantum sensing of oscillating electric fields with trapped ions. Measurement: Sensors 2021, 18, 100271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measen.2021.100271. [CrossRef]

- Affolter, M.; Ge, W.; Bullock, B.; Burd, S.C.; Gilmore, K.A.; Lilieholm, J.F.; Carter, A.L.; Bollinger, J.J. Toward improved quantum simulations and sensing with trapped two-dimensional ion crystals via parametric amplification. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 107, 032425. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.107.032425. [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A. An Introduction to Trapped Ions, Scalability and Quantum Metrology. Quantum Information and Coherence; Andersson, E.; Öhberg, P., Eds. Springer, 2011, Vol. 67, Scottish Graduate Series, pp. 211 – 246. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04063-9_9. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S.; Pedrozo-Peñafiel, E.; Adiyatullin, A.F.; Li, Z.; Mendez, E.; Shu, C.; Vuletić, V. Time-reversal-based quantum metrology with many-body entangled states. Nat. Phys. 2022, 18, 925 – 930. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-022-01653-5. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Watkins, J.; Frame, D.; Given, G.; He, R.; Li, N.; Lu, B.N.; Sarkar, A. Time fractals and discrete scale invariance with trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 100, 011403. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.100.011403. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Gong, Z.X.; Yin, Z.Q.; Quan, H.T.; Yin, X.; Zhang, P.; Duan, L.M.; Zhang, X. Space-Time Crystals of Trapped Ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 163001. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.163001. [CrossRef]

- Vanier, J.; Tomescu, C. The Quantum Physics of Atomic Frequency Standards: Recent Developments; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1201/b18738. [CrossRef]

- Ludlow, A.D.; Boyd, M.M.; Ye, J.; Peik, E.; Schmidt, P.O. Optical atomic clocks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015, 87, 637 – 701. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.87.637. [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, T.; Didier, A.; Doležal, M.; Balling, P.; Burgermeister, T.; Mehlstäubler, T.E. Sub-kelvin temperature management in ion traps for optical clocks. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2020, 91, 111301. https://doi.org/10.1063/ 5.0024693. [CrossRef]

- Hausser, H.N.; Keller, J.; Nordmann, T.; Bhatt, N.M.; Kiethe, J.; Liu, H.; von Boehn, M.; Rahm, J.; Weyers, S.; Benkler, E.; Lipphardt, B.; Doerscher, S.; Stahl, K.; Klose, J.; Lisdat, C.; Filzinger, M.; Huntemann, N.; Peik, E.; Mehlstäubler, T.E. An An 115In+–172Yb+ Coulomb crystalclockwith 2.5 × 10−18 systematic uncertainty, 2024, [arXiv:physics.atom-ph/2402.16807].

- Barontini, G.; Boyer, V.; Calmet, X.; Fitch, N.J.; Forgan, E.M.; Godun, R.M.; Goldwin, J.; Guarrera, V.; Hill, I.R.; Jeong, M.; Keller, M.; Kuipers, F.; Margolis, H.S.; Newman, P.; Prokhorov, L.; Rodewald, J.; Sauer, B.E.; Schioppo, M.; Sherrill, N.; Tarbutt, M.R.; Vecchio, A.; Worm, S. QSNET, a network of clock for measuring the stability of fundamental constants. Quantum Technology: Driving Commercialisation of an Enabling Science II; Padgett, M.J.; Bongs, K.; Fedrizzi, A.; Politi, A., Eds. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE, 2021, Vol. 11881, pp. 63 – 66. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2600493. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.D.; Eby, J.; Safronova, M.S. Direct detection of ultralight dark matter bound to the Sun with space quantum sensors. Nat. Astron. 2023, 7, 113 – 121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-022-01833-6. [CrossRef]

- Safronova, M.S.; Budker, D.; DeMille, D.; Kimball, D.F.J.; Derevianko, A.; Clark, C.W. Search for new physics with atoms and molecules. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 025008. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.90.025008. [CrossRef]

- Schkolnik, V.; Budker, D.; Fartmann, O.; Flambaum, V.; Hollberg, L.; Kalaydzhyan, T.; Kolkowitz, S.; Krutzik, M.; Ludlow, A.; Newbury, N.; Pyrlik, C.; Sinclair, L.; Stadnik, Y.; Tietje, I.; Ye, J.; Williams, J. Optical atomic clock aboard an Earth-orbiting space station (OACESS): enhancing searches for physics beyond the standard model in space. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2022, 8, 014003. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/ac9f2b. [CrossRef]

- Derevianko, A.; Gibble, K.; Hollberg, L.; Newbury, N.R.; Oates, C.; Safronova, M.S.; Sinclair, L.C.; Yu, N. Fundamental physics with a state-of-the-art optical clock in space. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2022, 7, 044002. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/ac7df9. [CrossRef]

- McGrew, W.F.; Zhang, X.; Leopardi, H.; Fasano, R.J.; Nicolodi, D.; Beloy, K.; Yao, J.; Sherman, J.A.; Schäffer, S.A.; Savory, J.; Brown, R.C.; Römisch, S.; Oates, C.W.; Parker, T.E.; Fortier, T.M.; Ludlow, A.D. Towards the optical second: verifying optical clocks at the SI limit. Optica 2019, 6, 448 – 454. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.6.000448. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Guan, J.Y.; Ren, J.G.; Zeng, T.; Hou, L.; Li, M.; Cao, Y.; Han, J.J.; Lian, M.Z.; Chen, Y.W.; Peng, X.X.; Wang, S.M.; Zhu, D.Y.; Shi, X.P.; Wang, Z.G.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.Y.; Pan, G.S.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.H.; Wu, J.C.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Chen, F.X.; Lu, C.Y.; Liao, S.K.; Yin, J.; Jia, J.J.; Peng, C.Z.; Jiang, H.F.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, J.W. Free-space dissemination of time and frequency with 10-19 instability over 113 km. Nature 2022, 610, 661 – 666. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05228-5. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.E.; McGrew, W.F.; Nardelli, N.V.; Clements, E.R.; Hassan, Y.S.; Zhang, X.; Valencia, J.L.; Leopardi, H.; Hume, D.B.; Fortier, T.M.; Ludlow, A.D.; Leibrandt, D.R. Improved interspecies optical clock comparisons through differential spectroscopy. Nat. Phys. 2023, 19, 25 – 29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-022-01794-7. [CrossRef]

- Peik, E. Optical Atomic Clocks. In Photonic Quantum Technologies; Benyoucef, M., Ed.; Wiley, 2023; chapter 14, pp. 333 – 348. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527837427.ch14. [CrossRef]

- Dimarcq, N.; Gertsvolf, M.; Mileti, G.; Bize, S.; Oates, C.W.; Peik, E.; Calonico, D.; Ido, T.; Tavella, P.; Meynadier, F.; Petit, G.; Panfilo, G.; Bartholomew, J.; Defraigne, P.; Donley, E.A.; Hedekvist, P.O.; Sesia, I.; Wouters, M.; Dubé, P.; Fang, F.; Levi, F.; Lodewyck, J.; Margolis, H.S.; Newell, D.; Slyusarev, S.; Weyers, S.; Uzan, J.P.; Yasuda, M.; Yu, D.H.; Rieck, C.; Schnatz, H.; Hanado, Y.; Fujieda, M.; Pottie, P.E.; Hanssen, J.; Malimon, A.; Ashby, N. Roadmap towards the redefinition of the second. Metrologia 2024, 61, 012001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1681-7575/ad17d2. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.K.; Satyajit, K.T.; Rao, P.M. Influence of a geometrical perturbation on the ion dynamics in a 3D Paul trap. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2015, 800, 111 – 118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2015.07.046. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Decker, T.K.; McClellan, J.S.; Wu, Q.; De la Cruz, A.; Hawkins, A.R.; Austin, D.E. Experimental Observation of the Effects of Translational and Rotational Electrode Misalignment on a Planar Linear Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 2018, 29, 1376 – 1385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-018-1942-x. [CrossRef]

- Alheit, R.; Kleineidam, S.; Vedel, F.; Vedel, M.; Werth, G. Higher order non-linear resonances in a Paul trap. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Proc. 1996, 154, 155 – 169. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1176(96)04380-7. [CrossRef]

- Takai, R.; Nakayama, K.; Saiki, W.; Ito, K.; Okamoto, H. Nonlinear Resonance Effects in a Linear Paul Trap. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 2007, 76, 014802. https://doi.org/10.1143/JPSJ.76.014802. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, N.; Zhan, L.; Chen, Y.; Nie, Z. Nonlinear Ion Harmonics in the Paul Trap with Added Octopole Field: Theoretical Characterization and New Insight into Nonlinear Resonance Effect. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 27, 344 – 351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-015-1291-y. [CrossRef]

- Marchenay, M.; Pedregosa-Gutierrez, J.; Knoop, M.; Houssin, M.; Champenois, C. An analytical approach to symmetry breaking in multipole RF-traps. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2021, 6, 024016. https://doi.org/10.1088/ 2058-9565/abeaf6. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.A.; Ozakin, A. Stability analysis of ion motion in asymmetric planar ion traps. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 074904. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4752404. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Y.; Xie, Y.; Wan, W.; Chen, L.; Zhou, F.; Feng, M. A complicated Duffing oscillator in the surface-electrode ion trap. Appl. Phys. B 2014, 114, 81 – 88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00340-013-5541-z. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, I.; Saxena, V.; Krishnamachari, A. Resonance Curves and Jump Frequencies in a Dual-Frequency Paul Trap on Account of Octopole Field Imperfection. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2023, 51, 1924 – 1931. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2023.3285260. [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, B.M.; Visan, G.T.; Giurgiu, L.C.; Radan, S. Optimization of ion trap geometries and of the signal to noise ratio for high resolution spectroscopy. J. Optoelectron. Adv. Mat. 2008, 10, 1994 – 1998.

- Pedregosa, J.; Champenois, C.; Houssin, M.; Knoop, M. Anharmonic contributions in real RF linear quadrupole traps. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 290, 100 – 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2009.12.009. [CrossRef]

- Home, J.P.; Hanneke, D.; Jost, J.D.; Leibfried, D.; Wineland, D.J. Normal modes of trapped ions in the presence of anharmonic trap potentials. New J. Phys. 2011, 13, 073026. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/13/7/073026. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.T.; Yu, Q.; Beck, K.M.; Häffner, H. One- and two-qubit gate infidelities due to motional errors in trapped ions and electrons. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 105, 022437. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.105.022437. [CrossRef]

- Lindvall, T.; Hanhijärvi, K.J.; Fordell, T.; Wallin, A.E. High-accuracy determination of Paul-trap stability parameters for electric-quadrupole-shift prediction. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 124401. https://doi.org/10.1063/ 5.0106633. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zeng, M.; Hao, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, H.; Guan, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, M.; Gao, K. Liquid-Nitrogen-Cooled Ca+ Optical Clock with Systematic Uncertainty of 3 ×10-18. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2022, 17, 034041. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.17.034041. [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, A.; Stacey, J.; Mulholland, S.; Robertson, B.I.; Klein, H.A.; Huang, G.; Barwood, G.P.; Gill, P. An ion trap design for a space-deployable strontium-ion optical clock. Proc. R. Soc. A 2024, 480, 20230593. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2023.0593. [CrossRef]

- Leibrandt, D.R.; Porsev, S.G.; Cheung, C.; Safronova, M.S. Prospects of a thousand-ion Sn2+ Coulomb-crystal clock with sub-10-19 inaccuracy, 2022, [arXiv:physics.atom-ph/2205.15484].

- Martínez-Lahuerta, V.J.; Eilers, S.; Mehlstäubler, T.E.; Schmidt, P.O.; Hammerer, K. Ab initio quantum theory of mass defect and time dilation in trapped-ion optical clocks. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 106, 032803. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.106.032803. [CrossRef]

- Zhiqiang, Z.; Arnold, K.J.; Kaewuam, R.; Barrett, M.D. 176Lu+ clock comparison at the 10-18 level via correlation spectroscopy. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg1971. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adg1971. [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Holliman, C.A.; Shi, X.; Zhang, H.; Straus, M.W.; Li, X.; Buechele, S.W.; Jayich, A.M. Optical Mass Spectrometry of Cold RaOH+ and RaOCH3+. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 023002. https://doi.org/10.1103/ PhysRevLett.126.023002. [CrossRef]

- Landau, A.; Eduardus.; Behar, D.; Wallach, E.R.; Pašteka, L.F.; Faraji, S.; Borschevsky, A.; Shagam, Y. Chiral molecule candidates for trapped ion spectroscopy by ab initio calculations: From state preparation to parity violation. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 159, 114307. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0163641. [CrossRef]

- Rajanbabu, N.; Marathe, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Menon, A.G. Multiple scales analysis of early and delayed boundary ejection in Paul traps. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 261, 170 – 182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2006.09.009. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Deng, Y.; Fang, X.; Xu, W. The coupling effects of hexapole and octopole fields in quadrupole ion traps: a theoretical study. J. Mass Spectrom. 2013, 48, 937 – 944. https://doi.org/10.1002/jms.3239. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, N.; Zhan, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Nie, Z. A Theoretical Method for Characterizing Nonlinear Effects in Paul Traps with Added Octopole Field. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 26, 1338 – 1348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-015-1145-7. [CrossRef]

- Karličić, D.; Chatterjee, T.; Cajić, M.; Adhikari, S. Parametrically amplified Mathieu-Duffing nonlinear energy harvesters. J. Sound Vib. 2020, 488, 115677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2020.115677. [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, I.; Brenner, M.J., Eds. The Duffing Equation: Nonlinear Oscillations and their Behaviour; Theoretical, Computational, and Statistical Physics, Wiley: Chichester, West Sussex, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ 9780470977859. [CrossRef]

- Moatimid, G.M.; Amer, T.S.; Amer, W.S. Dynamical analysis of a damped harmonic forced duffing oscillator with time delay. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6507. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33461-z. [CrossRef]

- Kotana, A.N.; Mohanty, A.K. Computation of Mathieu stability plot for an arbitrary toroidal ion trap mass analyser. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 414, 13 – 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2016.11.021. [CrossRef]

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering, 2nd ed.; Studies in Nonlinearity, CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429492563. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Uehara, K. Dynamics of a single particle in a Paul trap in the presence of the damping force. Appl. Phys. B 1995, 61, 159 – 163. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01090937. [CrossRef]

- Sevugarajan, S.; Menon, A.G. Frequency perturbation in nonlinear Paul traps: A simulation study of the effect of geometric aberration, space charge, dipolar excitation, and damping on ion axial secular frequency. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2000, 197, 263 – 278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1387-3806(99)00265-1. [CrossRef]

- Sevugarajan, S.; Menon, A.G. Transition curves and iso-βu lines in nonlinear Paul traps. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2002, 218, 181 – 196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1387-3806(02)00692-9. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhu, Z.; Xiong, C.; Chen, R.; Xu, W.; Qiao, H.; Peng, W.P.; Nie, Z.; Chen, Y. Characteristics of stability boundary and frequency in nonlinear ion trap mass spectrometer. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 21, 1588 – 1595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasms.2010.04.013. [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, R.; Sata, H.; Shoji, T. Chaos-Induced Diffusion in a Nonlinear Dissipative Mathieu Equation for a Charged Fine Particle in an AC Trap. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2011, 80, 044001. https://doi.org/10.1143/JPSJ.80.044001. [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, J.J.H. Asymptotic solutions for Mathieu instability under random parametric excitation and nonlinear damping. Physica D 2011, 240, 990 – 1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physd.2011.02.009. [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, B.M.; Vişan, G.G. Nonlinear ion trap stability analysis. Phys. Scr. 2010, T140, 014057. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-8949/2010/T140/014057. [CrossRef]

- Rybin, V.; Rudyi, S.; Rozhdestvensky, Y. Nano- and microparticle nonlinear damping identification in quadrupole trap. Int. J. Non Linear Mech. 2022, 147, 104227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2022.104227. [CrossRef]

- Nayfeh, A.H.; Balachandran, B. Applied Nonlinear Dynamics: Analytical, Computational, and Experimental Methods, 2nd ed.; Wiley Series in Nonlinear Science, Wiley-VCH, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527617548. [CrossRef]

- Kyzioł, J.; Okniński, A. Duffing-type equations: Singular points of amplitude profiles and bifurcations. Acta Phys. Pol. B 2021, 52, 1239 – 1262. https://doi.org/10.5506/APhysPolB.52.1239. [CrossRef]

- Hassoul, S.; Menouar, S.; Benseridi, H.; Choi, J.R. Quantum dynamics for general time-dependent three coupled oscillators based on an exact decoupling. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 2022, 604, 127755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2022.127755. [CrossRef]

- El Fakkousy, I.; Zouhairi, B.; Benmalek, M.; Kharbach, J.; Rezzouk, A.; Ouazzani-Jamil, M. Classical and quantum integrability of the three-dimensional generalized trapped ion Hamiltonian. Chaos Solit. Fractals 2022, 161, 112361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112361. [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, B.M. Study of quasiclassical dynamics of trapped ions using the coherent state formalism and associated algebraic groups. Rom. J.. Phys. 2017, 62, 113.

- Rudyi, S.; Vasilyev, M.; Rybin, V.; Rozhdestvensky, Y. Stability problem in 3D multipole ion traps. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2022, 479, 116894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2022.116894. [CrossRef]

- Foot, C.J.; Trypogeorgos, D.; Bentine, E.; Gardner, A.; Keller, M. Two-frequency operation of a Paul trap to optimise confinement of two species of ions. Int. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2018, 430, 117 – 125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2018.05.007. [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, T.S.; Drewello, T. Probability distributions in quadrupole ion traps. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 468, 116641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2021.116641. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, D.T.; Kaplan, D.A.; Danell, R.M.; van Amerom, F.H.W.; Pinnick, V.T.; Brinkerhoff, W.B.; Mahaffy, P.R.; Cooks, R.G. Unique capabilities of AC frequency scanning and its implementation on a Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer linear ion trap. Analyst 2017, 142, 2109 – 2117. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7AN00664K. [CrossRef]

- MSOLO Science Instrument for VIPER Arrives at Johnson Space Center. https://www.nasa.gov/image-article/msolo-science-instrument-viper-arrives-johnson-space-center/, accessed on 03. 05. 2024.

- Patrick, E.L.; Blase, R.C.; Libardoni, M.J.; Poston, M.J. Environmental Analysis of the Bounded Lunar Exosphere (ENABLE): Lessons in Gas Sources from Apollos 11 to 17. Proc. of the 53rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC). Lunar and Planetary Institute & NASA, 2022.

- Paving the way to the Moon and Beyond. https://www.swri.org/technology-today/article/paving-the-way-the-moon-beyond, accessed on 03. 05. 2024.

- Chimwal, D.; Kumar, S.; Joshi, Y.; Lal, A.A.; Nair, L.; Quint, W.; Vogel, M. Electrostatic anharmonicity in cylindrical Penning traps induced by radial holes to the trap center. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 055404. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ad38e7. [CrossRef]

- Nötzold, M.; Hassan, S.Z.; Tauch, J.; Endres, E.; Wester, R.; Weidemüller, M. Thermometry in a Multipole Ion Trap. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10155264. [CrossRef]

- Tomescu, C.; Giurgiu, L. Atomic Clocks and Time Keeping in Romania. Rom. Rep. Phys. 2018, 70, 205.

- Itano, W.M.; Bergquist, J.C.; Bollinger, J.J.; Gilligan, J.M.; Heinzen, D.J.; Moore, F.L.; Raizen, M.G.; Wineland, D.J. Quantum projection noise: Population fluctuations in two-level systems. Phys. Rev. A 1993, 47, 3554 – 3570. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.47.3554. [CrossRef]

- Wineland, D.J.; Bollinger, J.J.; Itano, W.M.; Heinzen, D.J. Squeezed atomic states and projection noise in spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. A 1994, 50, 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.50.67. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.; Shi, C.; Heip, J.C.; Gessner, M.; Pezzè, L.; Smerzi, A.; Schulte, M.; Hammerer, K.; Schmidt, P.O. Motional Fock states for quantum-enhanced amplitude and phase measurements with trapped ions. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2929. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10576-4. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, E.D.; Sinclair, L.C.; Deschenes, J.D.; Giorgetta, F.; Newbury, N.R. Application of quantum-limited optical time transfer to space-based optical clock comparisons and coherent networks. APL Photonics 2024, 9, 016112. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0170107. [CrossRef]

- McAneny, M.; Freericks, J.K. Intrinsic anharmonic effects on the phonon frequencies and effective spin-spin interactions in a quantum simulator made from trapped ions in a linear Paul trap. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 053405. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.90.053405. [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.W. On the part of the motion of lunar perigee which is a function of the mean motions of the sun and moon. Acta Math. 1886, 8, 1 – 36. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02417081. [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, D. The Lindstedt–Poincaré Technique as an Algorithm for Computing Periodic Orbits. SIAM Review 2001, 43, 478 – 495. https://doi.org/10.1137/S0036144500375292. [CrossRef]

- Magnus, W.; Winkler, S. Hill’s Equation; Vol. 20, Interscience Tracts in Pure and Applied Mathematics, Wiley: New York, 1966. https://doi.org/10.1002/zamm.19680480218. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.; Holzer, B.J. Beam Dynamics. In Particle Physics Reference Library : Volume 3: Accelerators and Colliders; Myers, S.; Schopper, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 15–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34245-6_2. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.; Collado, J. Periodic Solutions in Non-Homogeneous Hill Equation. Nonlinear Dyn. Syst. Theory 2020, 20, 78 – 91.

- Brillouin, L. A practical method for solving Hill’s equation. Quart. Appl. Math. 1948, 6, 167 – 178. https://doi.org/10.1090/qam/27111. [CrossRef]

- Moussa, R.A. Generalization of Ince’s Equation. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 2014, 2, 1171 – 1182. https://doi.org/ 10.4236/jamp.2014.213137. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, G. Mathieu Functions and Hill’s Equation. In NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions; Olver, F.W.J.; Lozier, D.W.; Boisvert, R.F.; Clark, C.W., Eds.; NIST & Cambridge Univ. Press: New York, NY, 2010; chapter 28, pp. 651 – 681.

- Landa, H.; Drewsen, M.; Reznik, B.; Retzker, A. Modes of oscillation in radiofrequency Paul traps. New J. Phys. 2012, 14, 093023. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/14/9/093023. [CrossRef]

- Ck Function. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/C-kFunction.html, accessed on 02. 05. 2024.

- Landa, H.; Drewsen, M.; Reznik, B.; Retzker, A. Classical and quantum modes of coupled Mathieu equations. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2012, 45, 455305. https://doi.org/10.1088/1751-8113/45/45/455305. [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, D.; Portugal, R. Algebraic methods to compute Mathieu functions. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 2001, 34, 3541 – 3551. https://doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/34/17/302. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W. Introduction to Mathematical Physics: Methods and Concepts, 2nd ed.; Oxford Univ. Press: Oxford, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199641390.002.0003. [CrossRef]

- Gezerlis, A. Numerical Methods in Physics with Python, 2nd ed.; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009303897. [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. Mathieu’s Equations and the ideal RF-Paul Trap. http://einstein.drexel.edu/~tim/open/mat/mat.pdf, accessed on 21. 05. 2024.

- Sträng, J.E. On the characteristic exponents of Floquet solutions to the Mathieu equation. Bull. Acad. R. Belg. 2005, 16, 269–287. https://doi.org/10.3406/barb.2005.28492. [CrossRef]

- Weyl, H. Meromorphic Functions and Analytic Curves; Vol. 12, Annals of Mathematics Studies, Princeton Univ. Press - De Gruyter: New Jersey, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400882281.

- Meromorphic Function. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/MeromorphicFunction.html, accessed on 02. 05. 2024.

- Canosa, J. Numerical solution of Mathieu’s equation. J. Computat. Phys. 1971, 7, 255 – 272. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0021-9991(71)90088-X. [CrossRef]

- Bibby, M.M.; Peterson, A.F. In Accurate Computation of Mathieu Functions; Balanis, C.A., Ed.; Morgan&Claypool, 2014; Vol. Lecture 32, Synthesis Lectures on Computational Electromagnetics. https://doi.org/10.2200/ S00526ED1V01Y201307CEM032. [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, V.N.; Giurgiu, L.; Stoican, O.; Cacicovschi, D.; Molnar, R.; Mihalcea, B. Ordered Structures in a Variable Length AC Trap. Acta Phys. Pol. A 1998, 93, 625 – 629. https://doi.org/10.12693/aphyspola.93.625. [CrossRef]

- Wuerker, R.F.; Shelton, H.; Langmuir, R.V. Electrodynamic Containment of Charged Particles. J. Appl. Phys. 1959, 30, 342 – 349. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1735165. [CrossRef]

- Dehmelt, H. Radiofrequency Spectroscopy of Stored Ions I: Storage; Academic Press, 1968; Vol. 3, Advances in Atomic and Molecular Physics, pp. 53 – 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2199(08)60170-0. [CrossRef]

- March, R.E.; Todd, J.F.J. In Quadrupole Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry, 2nd ed.; Winefordner, J.D., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2005; Vol. 165, Chemical Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471717983. [CrossRef]

- Breslin, J.K.; Holmes, C.A.; Milburn, G.J. Quantum signatures of chaos in the dynamics of a trapped ion. Phys. Rev. A 1997, 56, 3022 – 3027. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.56.3022. [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.A.; Cirac, J.I.; Zoller, P. Quantum Chaos in an Ion Trap: The Delta-Kicked Harmonic Oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 4790 – 4793. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.4790. [CrossRef]

- Menicucci, N.C.; Milburn, G.J. Single trapped ion as a time-dependent harmonic oscillator. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 76, 052105. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.76.052105. [CrossRef]

- Rudyi, S.S.; Rybin, V.V.; Semynin, M.S.; Shcherbinin, D.P.; Rozhdestvensky, Y.V.; Ivanov, A.V. Period-doubling bifurcation in surface radio-frequency trap: Transition to chaos through Feigenbaum scenario. Chaos 2023, 33, 093133. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0157397. [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, B.M. Semiclassical dynamics for an ion confined within a nonlinear electromagnetic trap. Phys. Scr. 2011, T143, 014018. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-8949/2011/T143/014018. [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, B.M. Nonlinear harmonic boson oscillator. Phys. Scr. 2010, T140, 014056. https://doi.org/10.1088/ 0031-8949/2010/T140/014056. [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, V.N.; Mihalcea, B.M.; Gheorghe, A. Ion stability in laser fields and anharmonic RF potentials. 29th EGAS Conference Abstracts; Kronfeldt, H.D., Ed.; European Physical Society, European Physical Society: Berlin, 1997; p. 427.

- Taylor, M.E. Introduction to Complex Analysis; Vol. 202, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, American Mathematical Society, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1090/gsm/202. [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Shah, R.; Kumam, P.; Baleanu, D.; Arif, M. Laplace decomposition for solving nonlinear system of fractional order partial differential equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 375. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13662-020-02839-y. [CrossRef]

- Richards, D. Advanced Mathematical Methods with Maple; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, 2009.

- Liu, C.S.; Chen, Y.W. A Simplified Lindstedt-Poincaré Method for Saving Computational Cost to Determine Higher Order Nonlinear Free Vibrations. Mathematics 2021, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9233070. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).