Submitted:

28 May 2024

Posted:

28 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Reagents and Materials

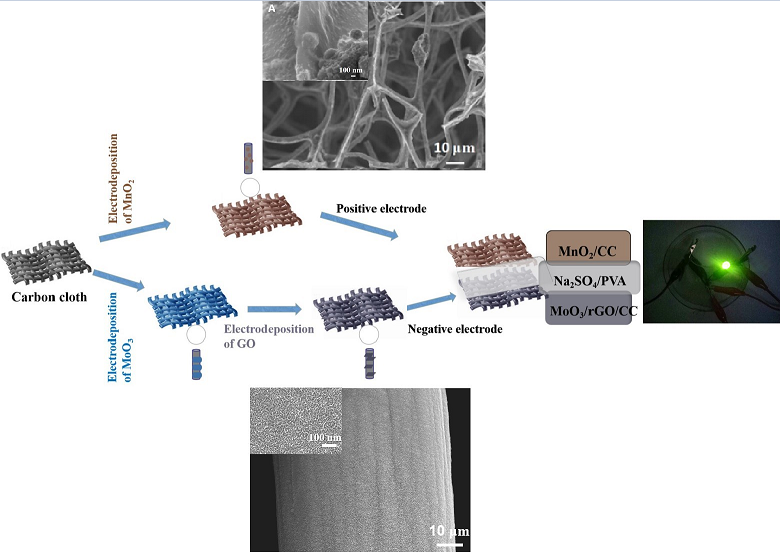

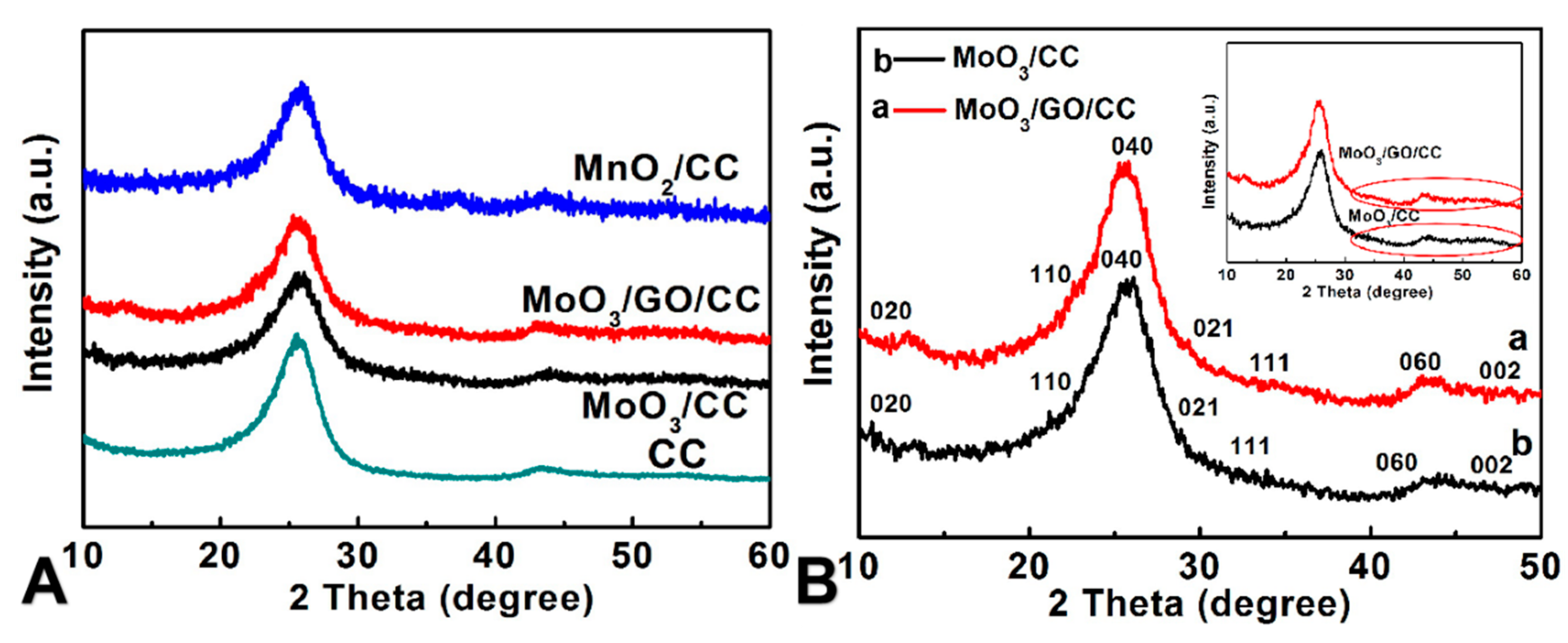

2.2. Preparation of the Negative Electrodes

2.3. Fabrication of the Electrode of MnO2/CC

2.4. Fabrication of the FASC Devices

2.5. Characterization and Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

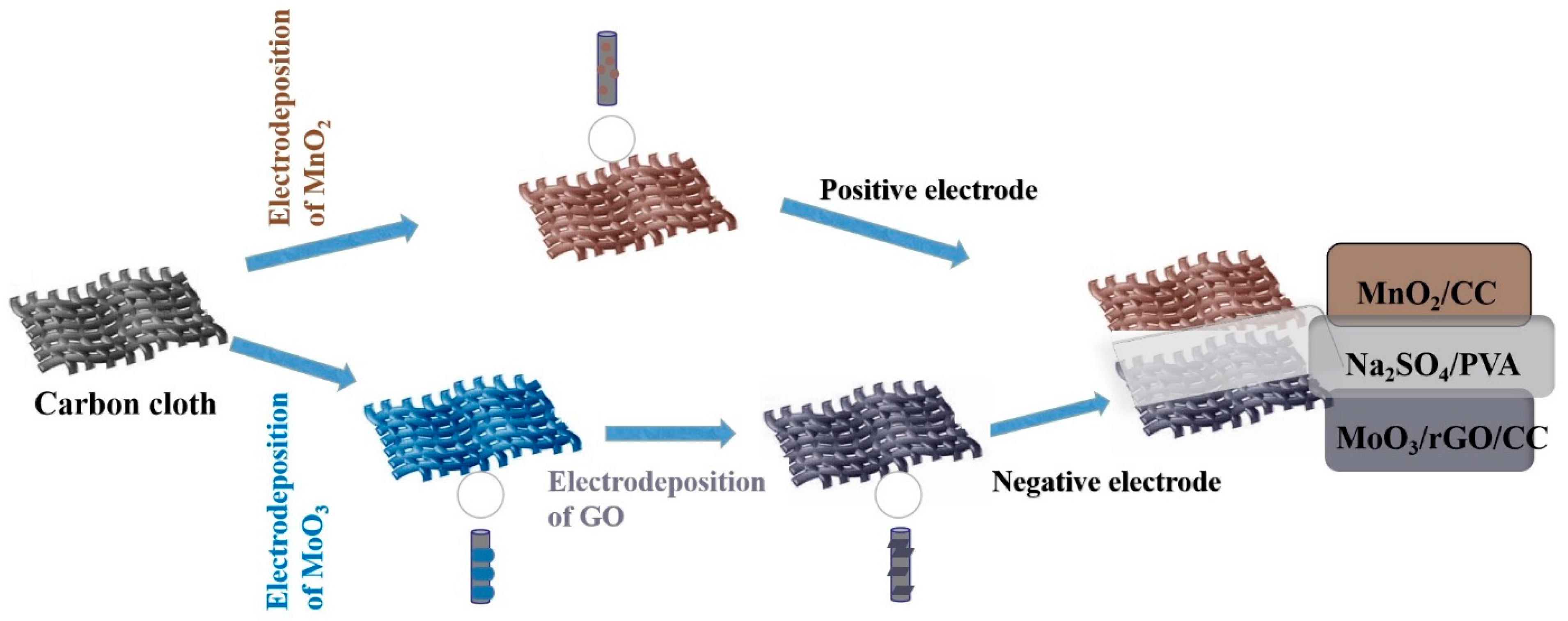

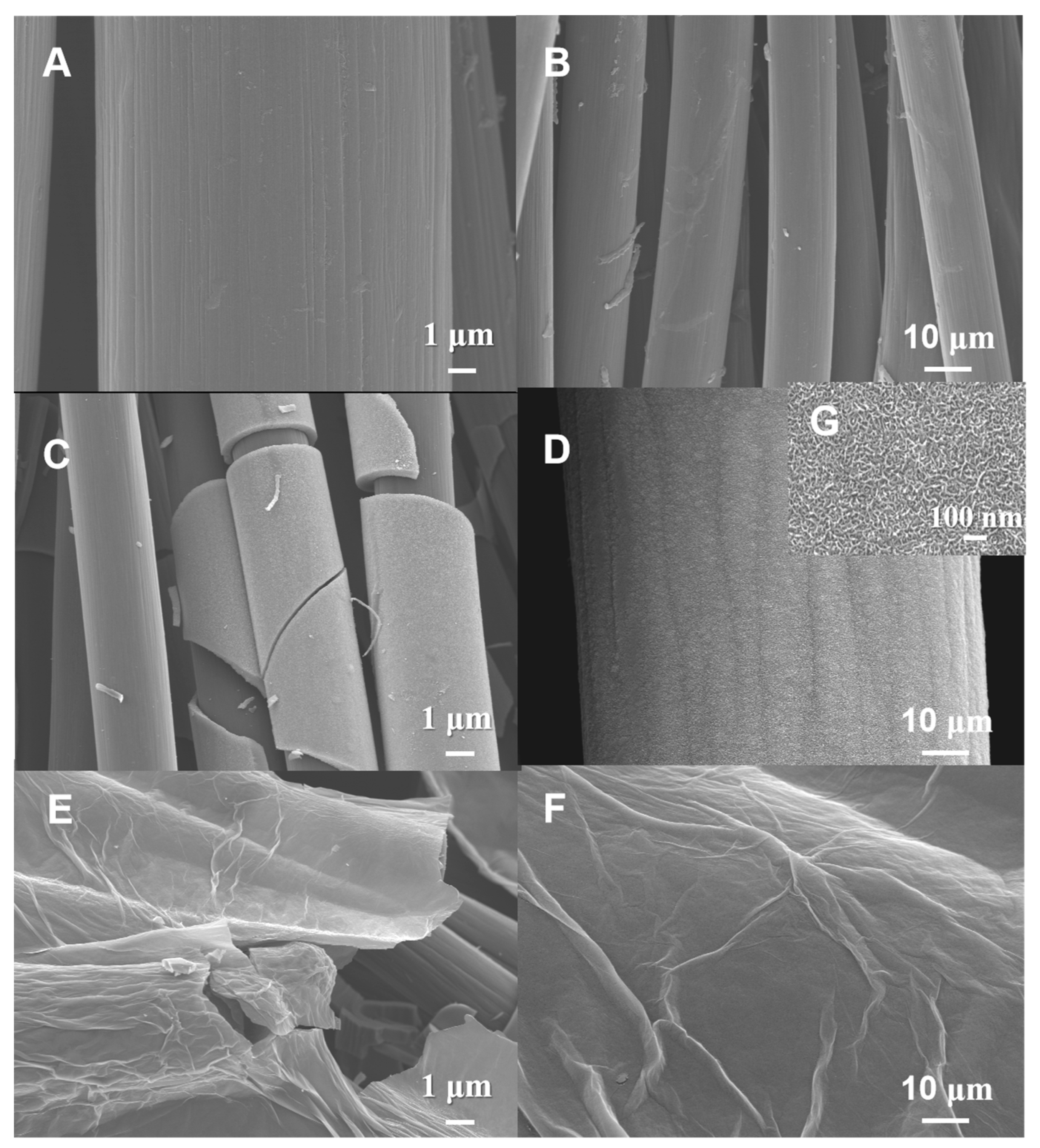

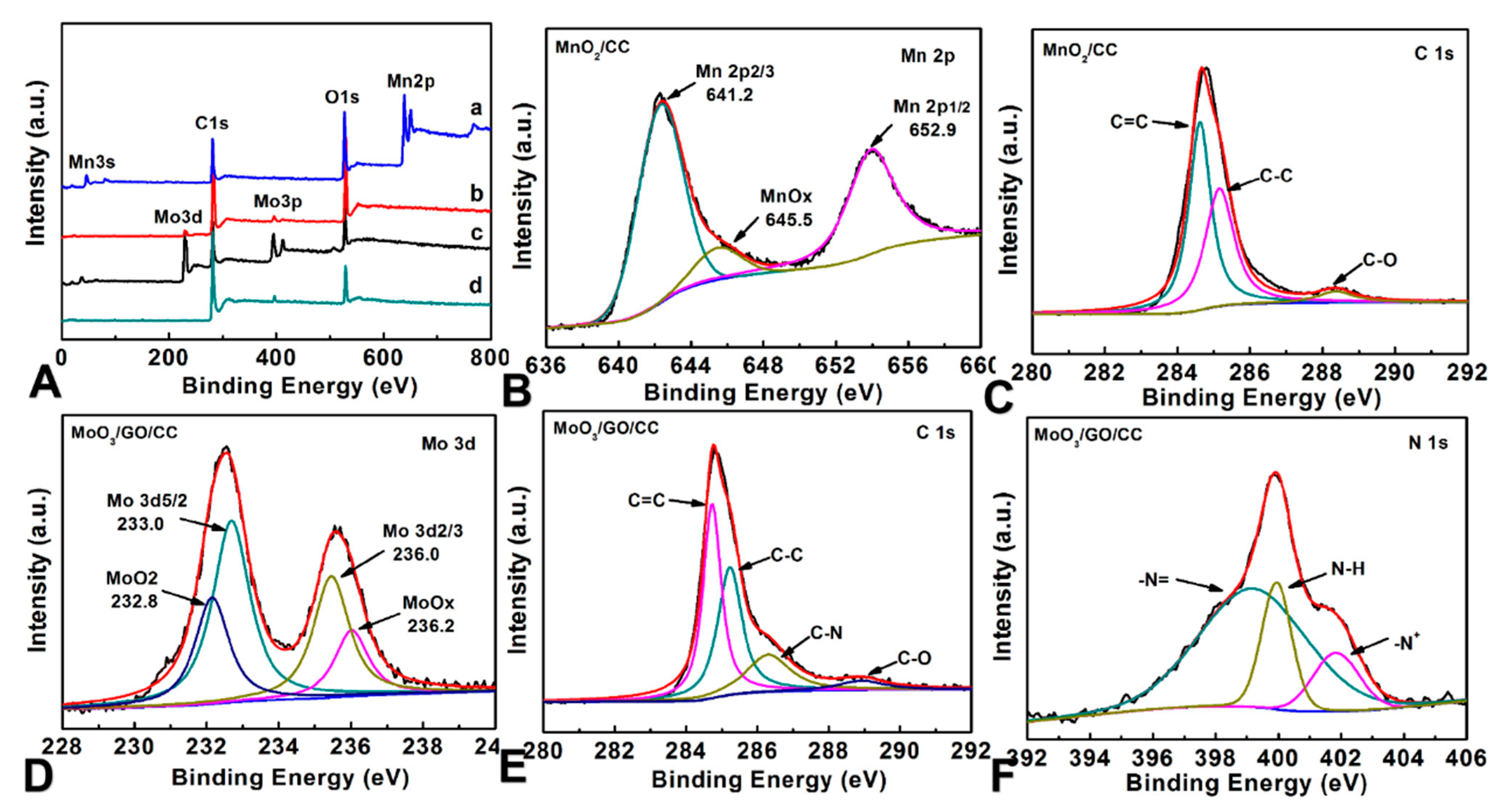

3.1. Structural Properties Characterization of All Samples

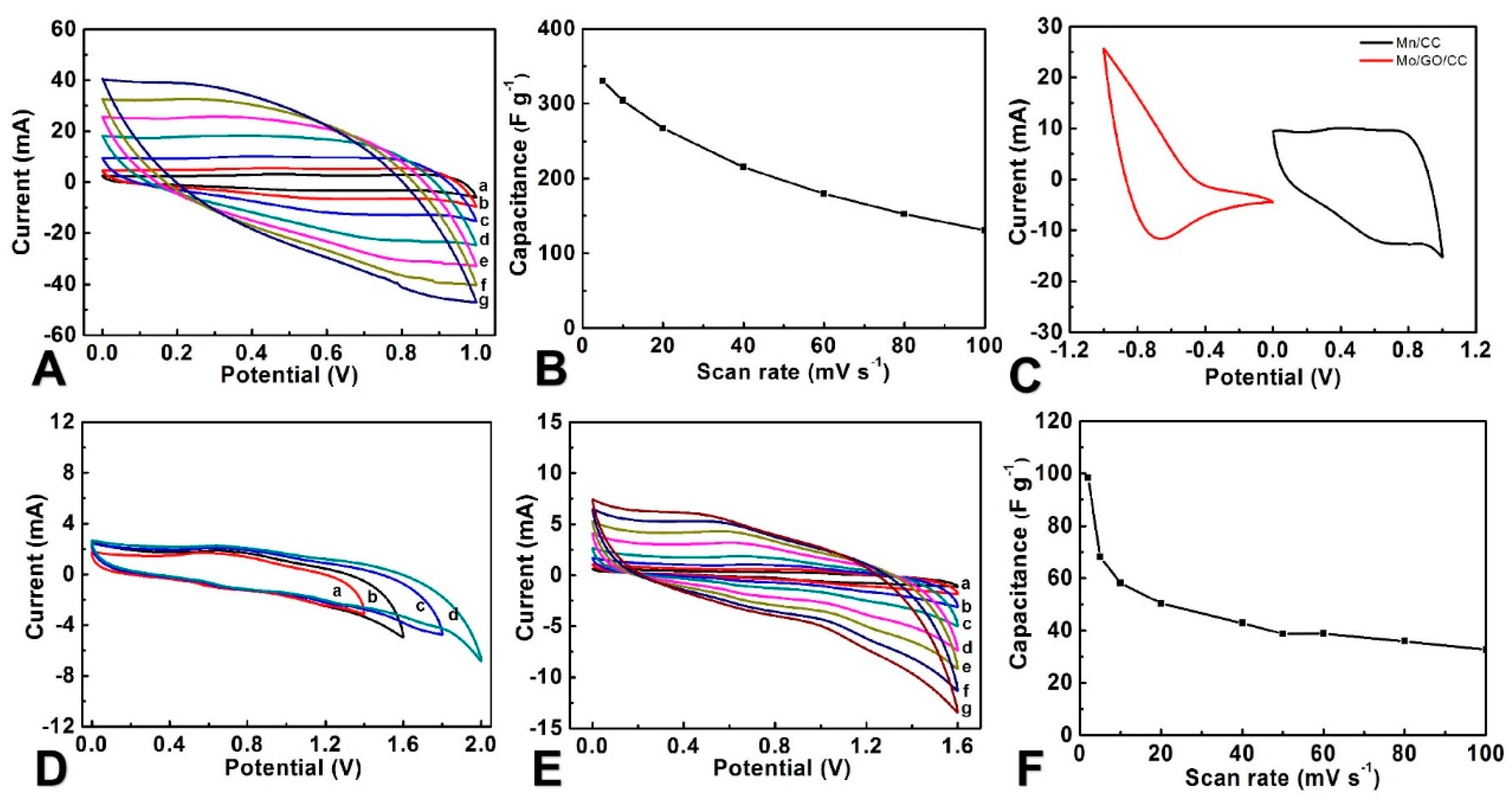

3.2. The Electrochemical Properties of MoO3/rGO/CC

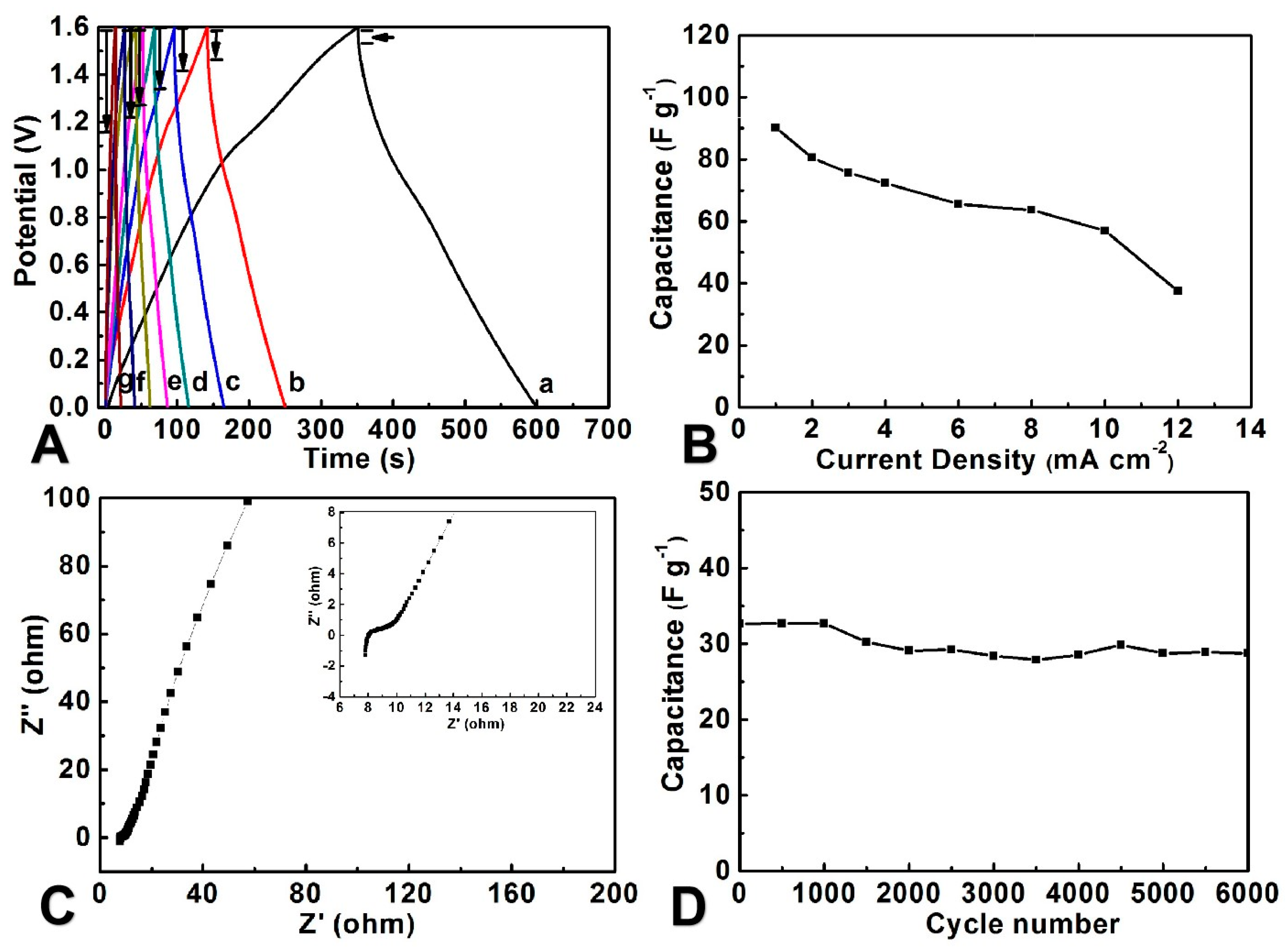

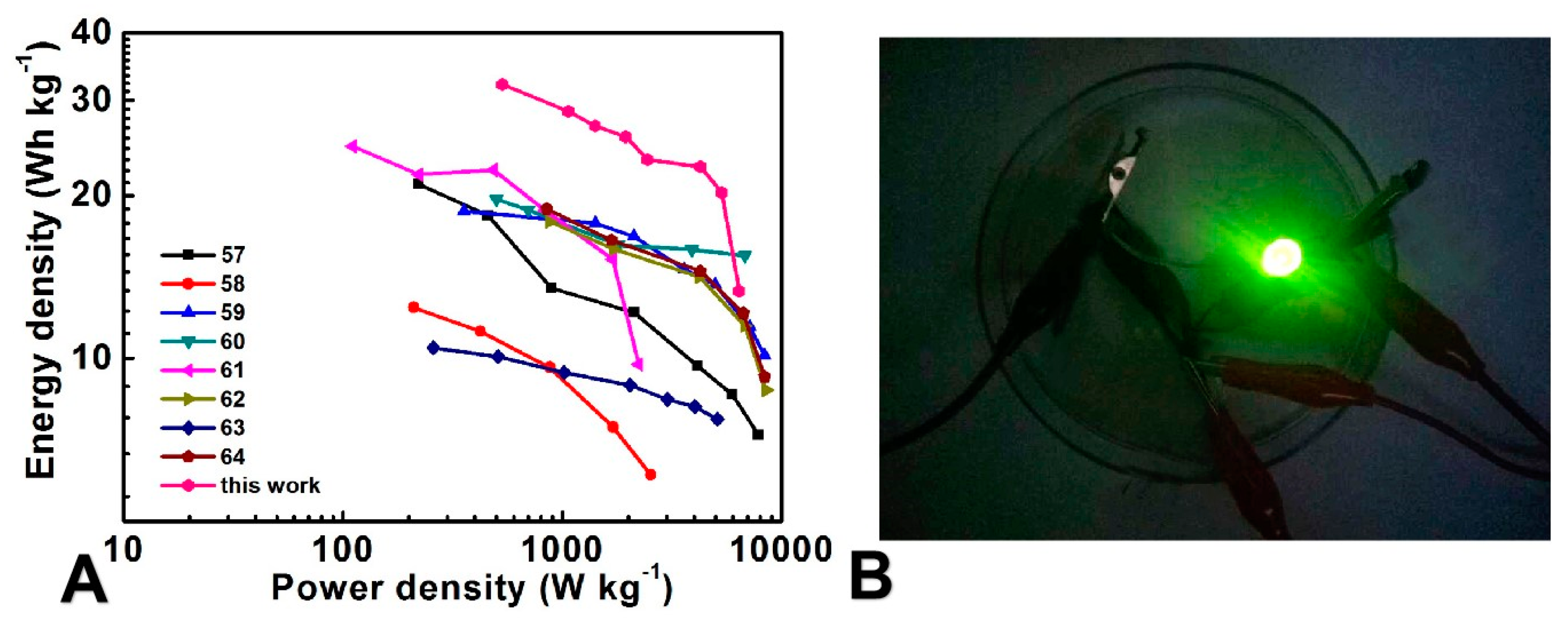

3.3. Electrochemical Performance of the FASC

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- W. He: Bo W., M.T. Lu, Z. Li, H. Qiang, Fabrication and Performance of Self-Supported Flexible Cellulose Nanofibrils/Reduced Graphene Oxide Supercapacitor Electrode Materials, Molecules 12 (2020) 2793-2807. [CrossRef]

- G.Q. Zhou, G. Liang, W. Xiao, L.L. Tian, Y.H. Zhang, R. Hu, Y. Wang, Porous α-Fe2O3 Hollow Rods/Reduced Graphene Oxide Composites Templated by MoO3 Nanobelts for High-Performance Supercapacitor Applications, Molecules 6 (2024) 1262-1351. [CrossRef]

- S. Saha, P. Samanta, N.C. Murmu, T. Kuila, A review on the heterostructure nanomaterials for supercapacitor application, J. Energy Storage 17 (2018) 181-202. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, J. Xu, D. Chen, G.Z. Shen, Flexible electronics based on inorganic nanowires, Chem Soc Rev 44 (2015) 161-192. [CrossRef]

- B.C. Kim, J.Y. Hong, G.G. Wallace, H.S. Park, Recent Progress in Flexible Electrochemical Capacitors: Electrode Materials, Device Configuration, and Functions, Adv Energy Mater 5 (2015) 1500959. [CrossRef]

- X.F. Wang, X.H. Lu, B. Liu, D. Chen, Y.X. Tong, G.Z. Shen, Flexible Energy-Storage Devices: Design Consideration and Recent Progress, Adv Mater 26 (2014) 4763-4782. [CrossRef]

- X. Lu, M. Xu, G. Wang, Flexible solid-state supercapacitors: design, fabrication and applications, Energ Environ Sci 7 (2014) 2160-2181. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, Z. Wu, S. Yuan, X.B. Zhang, Advances and challenges for flexible energy storage and conversion devices and systems, Energ Environ Sci 7 (2014) 2101-2122. [CrossRef]

- W.D. He, C.G. Wang, H.Q. Li, X.L. Deng, X.J. Xu, T.Y. Zhai, Ultrathin and Porous Ni3S2/CoNi2S4 3D-Network Structure for Superhigh Energy Density Asymmetric Supercapacitors, Adv Energy Mater 7 (2017) 1700983. [CrossRef]

- C. Guan, W. Zhao, Y.T. Hu, Z.C. Lai, X. Li, S.J. Sun, H. Zhang, A.K. Cheetham, J. Wang, Cobalt oxide and N-doped carbon nanosheets derived from a single two-dimensional metal-organic framework precursor and their application in flexible asymmetric supercapacitors, Nanoscale Horizons 2 (2017) 99-105. [CrossRef]

- N. Jabeen, A. Hussain, Q.Y. Xia, S. Sun, J.W. Zhu, H. Xia, High-Performance 2.6 V Aqueous Asymmetric Supercapacitors based on In Situ Formed Na0.5MnO2 Nanosheet Assembled Nanowall Arrays, Adv Mater 29 (2017) 1700804. [CrossRef]

- M.F. El-Kady, R.B. Kaner, Scalable fabrication of high-power graphene micro-supercapacitors for flexible and on-chip energy storage, Nat Commun 4 (2013) 1475-1484. [CrossRef]

- H. Gwon, H.S. Kim, K.U. Lee, D.H. Seo, Y.C. Park, Y.S. Lee, B.T. Ahn, K. Kang, Flexible energy storage devices based on graphene paper, Energ Environ Sci 4 (2011) 1277-1283. [CrossRef]

- S.W. Lee, B.S. Kim, S. Chen, Y. Shao-Horn, P.T. Hammond, Layer-by-Layer Assembly of All Carbon Nanotube Ultrathin Films for Electrochemical Applications, J Am Chem Soc 131 (2009) 671-679. [CrossRef]

- Y.W. Zhu, S. Murali, M.D. Stoller, K.J. Ganesh, W.W. Cai, P.J. Ferreira, A. Pirkle, R.M. Wallace, K.A. Cychosz, M. Thommes, D. Su, E.A. Stach, R.S. Ruoff, Carbon-Based Supercapacitors Produced by Activation of Graphene, Science 332 (2011) 1537-1541. [CrossRef]

- J.Z. Ling, H.B. Zou, W. Yang, W.S. Chen, Facile fabrication of polyaniline/molybdenum trioxide/activated carbon cloth composite for supercapacitors, Journal of Energy Storage 20 (2018) 92-100. [CrossRef]

- Y.Y. Horng, Y.C. Lu, Y.K. Hsu, C.C. Chen, L.C. Chen, K.H. Chen, Flexible supercapacitor based on polyaniline nanowires/carbon cloth with both high gravimetric and area-normalized capacitance, J. Power Sources 195 (2010) 4418-4422. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, G. Qin, Y. Lin, D. Zhang, H. Liao, Z. Li, J. Tian, Q. Wu, A novel flexible electrode with coaxial sandwich structure based polyaniline-coated MoS2 nanoflakes on activated carbon cloth, Electrochim. Acta 264 (2018) 91-100. [CrossRef]

- L.G.H. Staaf, P. Lundgren, P. Enoksson, Present and future supercapacitor carbon electrode materials for improved energy storage used in intelligent wireless sensor systems, Nano Energy 9 (2014) 128-141. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, Y. Huang, M.S. Zhu, W.J. Meng, Z.X. Pei, C. Liu, H. Hu, C.Y. Zhi, Magnetic-Assisted, Self-Healable, Yarn-Based Supercapacitor, ACS Nano 9 (2015) 6242-6251. [CrossRef]

- M.X. Wang, Q.L.Yan, F. Xue, J. Zhang, J.Q. Wang, Design and synthesis of carbon nanotubes/carbon fiber/reduced graphene oxide/MnO2 flexible electrode material for supercapacitors, J. PHYSICS AND CHEMISTRY OF SOLIDS 119 (2018) 29-35. [CrossRef]

- B. Mendoza-Sánchez, T. Brousse, C. Ramirez-Castro, V. Nicolosi, P.S. Grant, An investigation of nanostructured thin film α-MoO3 based supercapacitor electrodes in an aqueous electrolyte, Electrochim. Acta 91 (2013) 253–260. [CrossRef]

- T. Liu, W.G. Pell, B.E. Conway, Self-discharge and potential recovery phenomena at thermally and electrochemically prepared RuO2 supercapacitor electrodes, Electrochim. Acta 42 (1997) 3541–3552. [CrossRef]

- M.J. Klink, M.E. Makgae, A.M. Crouch, Physico-chemical and electrochemical characterization of Ti/RhOx –IrO2 electrodes using sol–gel technology, Mater. Chem. Phys. 124 (2010) 73–77. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, P. Yu, H. Zhang, D. Zhang, X. Sun, Y. Ma, Rapid hydrothermal synthesis of hierarchical nanostructures assembled from ultrathin birnessite-type MnO2 nanosheets for supercapacitor applications, Electrochim. Acta 89 (2013) 523–529. [CrossRef]

- X. Cao, B. Zheng, W. Shi, J. Yang, Z. Fan, Z. Luo, X. Rui, B. Chen, Q. Yan, H. Zhang, Reduced graphene oxide-wrapped MoO3 composites prepared by using metal-organic frameworks as precursor for all-solid-state flexible supercapacitors, Adv. Mater. 27 (2015) 4695–4701. [CrossRef]

- F. Barzegar, A. Bello, D. Momodu, J. Dangbegnon, F. Taghizadeh, J. Madito, T.M. Masikhwa, N. Manyala, Asymmetric supercapacitor based on α-MoO3 cathode and porous activated carbon anode materials, RSC Adv. 5 (2015) 37462–37468. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, B. Lin, J. Wang, P. Han, T. Xu, Y. Sun, X. Zhang, H. Yang, Polyoxometalates@Metal-organic frameworks derived porous MoO3@CuO as electrodes for symmetric all-solid-state supercapacitor, Electrochim. Acta 191 (2016) 795–804. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, X. Liu, Preparation and characterization of α-MoO3 nanobelt and its application in supercapacitor, Mater. Lett. 112 (2013) 39–42. [CrossRef]

- R.B. Pujari, V.C. Lokhande, V.S. Kumbhar, N.R. Chodankar, C.D. Lokhande, Hexagonal microrods architectured MoO3 thin film for supercapacitor application, J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 27 (2015) 3312–3317. [CrossRef]

- R. Liang, H. Cao, D. Qian, MoO3 nanowires as electrochemical pseudocapacitor materials, Chem. Commun. 47 (2011) 10305–10307. [CrossRef]

- G.R. Li, Z.L. Wang, F.L. Zheng, Y.N. Ou, Y.X. Tong, ZnO@MoO3 core/shell nanocables: facile electrochemical synthesis and enhanced supercapacitor performances, J. Mater. Chem. 21 (4217) (2011). [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, K. Dou, Y. Dong, Y. Zou, H. Zeng, Supercapacitor based on few-layer MoO3 nanosheets prepared by solvothermal method, Int. J. Nanomanuf. 12 (2016) 404. [CrossRef]

- J.C. Icaza, R.K. Guduru, Characterization of α-MoO3 anode with aqueous beryllium sulfate for supercapacitors, J. Alloys Compd. 726 (2017). [CrossRef]

- B. Mendoza-Sánchez, T. Brousse, C. Ramirez-Castro, V. Nicolosi, P.S. Grant, An investigation of nanostructured thin film α-MoO3 based supercapacitor electrodes in an aqueous electrolyte, Electrochim. Acta 91 (2013) 253–260. [CrossRef]

- M. Huang, F. Li, F. Dong, Y.X. Zhang, L.L. Zhang, MnO2-based nanostructures for high-performance supercapacitors, J Mater Chem A 3 (2015) 21380-21423. [CrossRef]

- W. Yao, J. Wang, H. Li, Flexible α-MnO2 paper formed by millimeter-long nanowires for supercapacitor electrodes, J. Power Sources 247 (2014) 824-830. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie, Z. Cheng, B. Guo B, Preparation of activated carbon paper by modified Hummer’s method and application as vanadium redox battery, Ionics 21 (2015) 283-287. [CrossRef]

- J. Chang, M. Jin, F. Yao, T.H. Kim, V.T. Le, H. Yue, et al., Asymmetric supercapacitors based on graphene/MnO2 nanospheres and graphene/MoO3 nanosheets with high energy density, Adv. Funct. Mater. 23 (2013)5074e5083.

- M.T. Greiner, M.G. Helander, W. Tang, Z. Wang, J. Qiu, Z. Lu, Universal energylevel alignment of molecules on metal oxides, Nat. Mater. 11 (2012) 76e81.

- Z. Zhang, K. Chi, F. Xiao, S. Wang, Advanced solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors based on 3D graphene/MnO2 and graphene/polypyrrole hybrid architectures, J. Mater. Chem. A 3 (2015) 12828–12835. [CrossRef]

- K. Lu, B. Song, K. Li, J.T. Zhang, Cobalt hexacyanoferrate nanoparticles and MoO3 thin films grown on carbon fiber cloth for efficient flexible hybrid supercapacitor, Journal of Power Sources 370 (2017) 98-105. [CrossRef]

- S. Han, L. Lin, K. Zhang, L. Luo, X. Peng, N. Hu, ZnWO4 nanoflakes decorated NiCo2O4 nanoneedle arrays grown on carbon cloth as supercapacitor electrodes, Mater. Lett. 193 (2017) 89-92. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, Y. Ding, Y. Xiong, Q. Yang, Y. Xie, One-step solution-based catalytic route to fabricate novel a-MnO2 hierarchical structures on a large scale, Chem. Commun. 7 (2005) 918e920. [CrossRef]

- J. Noh, C.M. Yoon, Y.K. Kim, J. Jang, High performance asymmetric supercapacitor twisted from carbon fiber/MnO2 and carbon fiber/MoO3, Carbon 116 (2017) 470-478. [CrossRef]

- F. Jiang, W. Li, R. Zou, Q. Liu, K. Xu, L. An, J. Hu, MoO3/PANI coaxial heterostructure nanobelts by in situ polymerization for high performance supercapacitors, Nano Energy 7 (2014) 72–79. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhou, W. Zhou, X. Liu, Y. Sang, S. Ji, W. Li, J. Lu, L. Li, W. Niu, H. Liu, Ultrathin MoO3 nanocrystalsself-assembled on graphene nanosheets via oxygen bonding as supercapacitor electrodes of high capacitance and long cycle life, Nano Energy 12 (2015) 510-520. [CrossRef]

- B.G. Choi, M. Yang, W.H. Hong, J.W. Choi, Y.S. Huh, 3D macroporous graphene frameworks for supercapacitors with high energy and power densities, ACS Nano 6 (2012) 4020e4028. [CrossRef]

- H. Cao, N. Wu, Y. Liu, S. Wang, W. Du, J. Liu, Facile synthesis of rod-like manganese molybdate crystallines with two-dimentional nanoflakes for supercapacitor application, Electrochim. Acta 225 (2017) 605–613. [CrossRef]

- B. Senthilkumar, R.K. Selvan, Hydrothermal synthesis and electrochemical performances of 1.7 V NiMoO₄⋅xH₂O||FeMoO₄ aqueous hybrid supercapacitor, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 426 (2014) 280–286. [CrossRef]

- Q.Y. Lv, S. Wang, H. Sun, Solid-State Thin-Film Supercapacitors with Ultrafast Charge/Discharge Based on N-Doped-Carbon-Tubes/Au-Nanoparticles-Doped-MnO2 Nanocomposites, Nano Lett 16 (2016) 40-47. [CrossRef]

- J. Cheng, M. Sprik, Alignment of electronic energy levels at electrochemical interfaces, Phys Chem Chem Phys 14 (2012) 11245-11267. [CrossRef]

- J.S. Lee, D.H. Shin, J. Jang, Polypyrrole-coated manganese dioxide with multiscale architectures for ultrahigh capacity energy storage, Energ Environ Sci 8 (2015) 3030-3039. [CrossRef]

- J.S. Lee, D.H. Shin, J. Jun, C. Lee, J. Jang, Fe3O4/Carbon Hybrid Nanoparticle Electrodes for High-Capacity Electrochemical Capacitors, Chemsuschem 7 (2014) 1676-1683. [CrossRef]

- S.K. Kim, Y.K. Kim, H. Lee, S.B. Lee, H.S. Park, Superior Pseudocapacitive Behavior of Confined Lignin Nanocrystals for Renewable Energy-Storage Materials, Chemsuschem 7 (2014) 1094-1101. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, Y.H. Chang, G.Y. Han, Y.M. Xiao, Asymmetric supercapacitor based on reduced graphene oxide/MnO2 and polypyrrole deposited on carbon foam derived from melamine sponge, Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 130 (2019) 100-110. [CrossRef]

- P. Du, W. Wei, D. Liu, Fabrication of hierarchical MoO3-PPy core-shell nanobelts and “worm-like” MWNTs–MnO2 core–shell materials for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitor, Journal of Materials Science (53) 2018 5255-5269. [CrossRef]

- J. Duay, E. Gillette, R. Liu, S.B. Lee, Highly flexible pseudocapacitor based on freestanding heterogeneous MnO2/conductive polymer nanowire arrays, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14 (2012) 3329-3337. [CrossRef]

- H. Fan, R. Niu, J. Duan, W. Liu, W. Shen, Fe3O4@carbon nanosheets for all-solidstate supercapacitor electrodes, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8 (2016) 19475-19483. [CrossRef]

- B.G. Choi, S.-J. Chang, H.-W. Kang, C.P. Park, H.J. Kim, W.H. Hong, S. Lee, Y.S. Huh, High performance of a solid-state flexible asymmetric supercapacitor based on graphene films, Nanoscale 4 (2012) 4983-4988. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jin, H. Chen, M. Chen, N. Liu, Q. Li, Graphene-patched CNT/MnO2 nanocomposite papers for the electrode of high-performance flexible asymmetric supercapacitors, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5 (2013) 3408-3416. [CrossRef]

- W. Liu, X. Li, M. Zhu, X. He, High-performance all-solid state asymmetric supercapacitor based on Co3O4 nanowires and carbon aerogel, J. Power Sources 282 (2015) 179-186. [CrossRef]

- H. Gao, F. Xiao, C.B. Ching, H. Duan, Flexible all-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors based on free-standing carbon nanotube/graphene and Mn3O4 nanoparticle/graphene paper electrodes, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4 (2012) 7020-7026. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, Z. Tang, M. Leng, J. Xue, Flexible solid-state supercapacitor based on graphene-based hybrid films, Adv. Funct. Mater. 24 (2014) 7495-7502. [CrossRef]

- N. Padmanathan, S. Selladurai, K.M. Razeeb, Ultra-fast rate capability of a symmetric supercapacitor with a hierarchical Co3O4 nanowire/nanoflower hybrid structure in non-aqueous electrolyte, RSC Adv. 5 (2015) 12700–12709. [CrossRef]

| Electrode materials | Electrolyte | Energy density (Wh kg-1) |

Stability (capacitance retention %, cycles) |

Ref. |

| MoO3-PPy//CNTs-MnO2 | Na2SO4/PVA gel | 21.0 | 76.0, 10000 cycles | [57] |

| MnO2@PEDOT//PEDOT | LiClO4/PMMA gel | 9.8 | 86.0, 1250 cycles | [58] |

|

Fe3O4 embedded in Carbon nanosheet//porous carbon |

KOH/PVA gel | 18.3 | 70.8, 5000 cycles | [59] |

| Graphene (IL-CMG) //RuO2-IL-CMG | H2SO4/PVA gel | 19.7 | 95.0, 2000 cycles | [60] |

| CNTs/MnO2//CNTs/PANI | Na2SO4/PVP gel | 24.8 | - | [61] |

|

Co3O4 nanowires/Ni-foam //carbon aerogel |

KOH/PVA gel | 17.9 | - | [62] |

| Mn3O4 nanoparticle/graphene //CNT/graphene | KCl/PVA gel | 32.7 | 86.0, 10000 cycles | [63] |

| Graphene/Ni(OH)2// graphene/CNT | KOH/PVA gel | 18 | - | [64] |

| MoO3/rGO/CC//MnO2/CC | Na2SO4/PVA gel | 32.1 | 88.1, 6000 cycles | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).