Submitted:

18 July 2024

Posted:

19 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Synthesis of Graphene Oxide, Metal Oxides and Graphene Oxide/Metal Oxide Hybrids

2.3. Structural, Chemical and Textural Characterization

2.4. Electrochemical Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Structural, Chemical, and Textural Characterization of Hybrid Materialssubsection

3.1.1. XPS, Raman Spectroscopy and Gases Adsorption

3.1.2. XRD and SEM Measurements

3.2. Electrochemical Performances

3.2.1. Cyclic Voltammetry

3.2.2. Galvanostatic Charge Discharge GCD

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAN | Acetonitrile |

| CV | Cyclic voltammetry |

| E | Energy density |

| EDLC | Electrochemical double layer capacitor |

| Et4NBF4 | Tetraethylammonium tetrafluoroborate |

| G | Graphene |

| GCD | Galvanostatic charge-discharge measurements. |

| GO | Graphene oxide |

| rGO | Reduced graphene oxide |

| GOMn41 | Hybrid with a 4/1 GO/ Mn(CH3COO)2 weight ratio. |

| GOMn11 | Hybrid with a 1/1 GO/ Mn(CH3COO)2 weight ratio. |

| GOMn14 | Hybrid with a 1/4 GO/ Mn(CH3COO)2 weight ratio. |

| P | Power density |

| SC | Specific capacitance obtained at 3-electrode cell in KOH |

| SCEDLC | Specific capacitance obtained at 2-electrode cell in organic medium. |

| SCFR | SC- SCEDLC |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy. |

| TMO | Transition Metal oxide |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray Powder Diffraction |

References

- Smol, J.P. Climate Change: A planet in flux. Nature 2012, 483, S12–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, E.; et al. Supersonically Sprayed Zn2SnO4/SnO2/CNT Nanocomposites for High-Performance Supercapacitor Electrodes. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2019, 7, 14031–14040. [Google Scholar]

- Lichchhavi, A. Kanwade, and P. M. Shirage, A review on synergy of transition metal oxide nanostructured materials: Effective and coherent choice for supercapacitor electrodes. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105692. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, M.E.; Blaabjerg, F.; Sangwongwanich, A. A Comprehensive Review on Supercapacitor Applications and Developments. Energies 2022, 15, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; et al. Battery-supercapacitor hybrid energy storage system in standalone DC microgrids: Areview. IET Renewable Power Generation 2017, 11, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; et al. Mesoporous nickel cobalt hydroxide/oxide as an excellent room temperature ammonia sensor. Scripta Materialia 2017, 128, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Zhao, X.S. Carbon-based materials as supercapacitor electrodes. Chemical Society Reviews 2009, 38, 2520–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balducci, A.; et al. High temperature carbon–carbon supercapacitor using ionic liquid as electrolyte. Journal of Power Sources 2007, 165, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragone, D.V. Review of Battery Systems for Electrically Powered Vehicles. 1968, SAE International.

- Afif, A.; et al. Advanced materials and technologies for hybrid supercapacitors for energy storage – A review. Journal of Energy Storage 2019, 25, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibona, T.E.; et al. Specific capacitance–pore texture relationship of biogas slurry mesoporous carbon/MnO2 composite electrodes for supercapacitors. Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects 2019, 17, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lebedeva, M.V.; et al. Micro–mesoporous carbons from rice husk as active materials for supercapacitors. Materials for Renewable and Sustainable Energy 2015, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibona Enock, T. King’ondu, C. K.; Pogrebnoi, A. Effect of biogas-slurry pyrolysis temperature on specific capacitance. Materials Today: Proceedings 2018, 5, 10611–10620. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. A carbon-based 3D current collector with surface protection for Li metal anode. Nano Research 2017, 10, 1356–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; et al. Influence of graphene microstructures on electrochemical performance for supercapacitors. Progress in Natural Science: Materials International 2015, 25, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, M.D.; et al. Graphene-Based Ultracapacitors. Nano Letters 2008, 8, 3498–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; et al. Supercapacitive vertical graphene nanosheets in aqueous electrolytes. Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects 2017, 10, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Q.; Wang, J. Graphene-based materials for supercapacitor electrodes – A review. Journal of Materiomics 2016, 2, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorso, F.; et al. Graphene, related two-dimensional crystals, and hybrid systems for energy conversion and storage. Science 2015, 347, 1246501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodankar, N.R.; Ji, S.-H.; Kim, D.-H. Surface Modified Carbon Cloth via Nitrogen Plasma for Supercapacitor Applications. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2018, 165, A2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asadi, A.S.; et al. Aligned carbon nanotube/zinc oxide nanowire hybrids as high performance electrodes for supercapacitor applications. Journal of Applied Physics 2017, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futaba, D.N.; et al. Shape-engineerable and highly densely packed single-walled carbon nanotubes and their application as super-capacitor electrodes. Nature Materials 2006, 5, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; et al. Carbon nanotube- and graphene-based nanomaterials and applications in high-voltage supercapacitor: A review. Carbon 2019, 141, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamdar, A.I.; et al. Chemically grown, porous, nickel oxide thin-film for electrochemical supercapacitors. Journal of Power Sources 2011, 196, 2393–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; et al. Transition metal based battery-type electrodes in hybrid supercapacitors: A review. Energy Storage Materials 2020, 28, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; et al. Strong synergetic electrochemistry between transition metals of α phase Ni−Co−Mn hydroxide contributed superior performance for hybrid supercapacitors. Journal of Power Sources 2019, 412, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Abdah, M.A.A.; et al. Review of the use of transition-metal-oxide and conducting polymer-based fibres for high-performance supercapacitors. Materials & Design 2020, 186, 108199. [Google Scholar]

- Kötz, R.; Carlen, M. Principles and applications of electrochemical capacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2000, 45, 2483–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; et al. Oxygen-Vacancy and Surface Modulation of Ultrathin Nickel Cobaltite Nanosheets as a High-Energy Cathode for Advanced Zn-Ion Batteries. Advanced Materials 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; et al. Flexible rechargeable Ni//Zn battery based on self-supported NiCo2O4 nanosheets with high power density and good cycling stability. Green Energy & Environment 2018, 3, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chodankar, N.R.; et al. Direct growth of FeCo2O4 nanowire arrays on flexible stainless steel mesh for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitor. NPG Asia Materials 2017, 9, e419–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.B.; et al. One-pot synthesis of η-Fe2O3 nanospheres/diatomite composites for electrochemical capacitor electrodes. Materials Letters 2018, 215, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodankar, N.R.; et al. Superfast Electrodeposition of Newly Developed RuCo2O4 Nanobelts over Low-Cost Stainless Steel Mesh for High-Performance Aqueous Supercapacitor. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2018, 5, 1800283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; et al. 3D interconnected ultrathin cobalt selenide nanosheets as cathode materials for hybrid supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2018, 269, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Pandey, V.K.; Verma, B. Facile synthesis of graphene oxide-polyaniline-copper cobaltite (GO/PANI/CuCo2O4) hybrid nanocomposite for supercapacitor applications. Synthetic Metals 2022, 286, 117036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, N.A.; Sampath, S.; Shukla, A.K. Hydrogel-polymer electrolytes for electrochemical capacitors: An overview. Energy & Environmental Science 2009, 2, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; et al. Influences of graphene oxide support on the electrochemical performances of graphene oxide-MnO2 nanocomposites. Nanoscale Research Letters 2011, 6, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repp, S.; et al. Synergetic effects of Fe3+ doped spinel Li4Ti5O12 nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide for high surface electrode hybrid supercapacitors. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmouwahidi, A.; et al. Carbon-TiO2 composites as high-performance supercapacitor electrodes: Synergistic effect between carbon and metal oxide phases. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018, 6, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, F.; et al. Microwave-mediated synthesis of tetragonal Mn3O4 nanostructure for supercapacitor application. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 71464–71471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.W.; Zhitomirsky, I. Influence of Capping Agents on the Synthesis of Mn3O4 Nanostructures for Supercapacitors. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2023, 6, 4428–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhitomirsky, I. Colloidal methods for the fabrication of Mn3O4-graphene film and bulk supercapacitors. Materials Letters 2023, 335, 133811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beknalkar, S.A.; et al. Mn3O4 based materials for electrochemical supercapacitors: Basic principles, charge storage mechanism, progress, and perspectives. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2022, 130, 227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; et al. A novel solvothermal synthesis of Mn3O4/graphene composites for supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2013, 90, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; et al. Mn3O4 nanoparticles embedded into graphene nanosheets: Preparation, characterization, and electrochemical properties for supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2010, 55, 6812–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; et al. One-pot hydrothermal synthesis of Mn3O4/graphene nanocomposite for supercapacitors. Materials Letters 2013, 95, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Graphene and Nanostructured Mn3O4 Composites for Supercapacitors. Integrated Ferroelectrics 2013, 144, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; et al. High performance Flower-Like Mn3O4/rGO composite for supercapacitor applications. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2022, 910, 116170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, T.A.; Stoeckli, F. Surface-related capacitance of microporous carbons in aqueous and organic electrolytes. Electrochimica Acta 2011, 56, 7334–7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; et al. Preparation of Porous Graphene@Mn3O4 and Its Application in the Oxygen Reduction Reaction and Supercapacitor. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2019, 7, 831–837. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H.; et al. Designing oxygen bonding between reduced graphene oxide and multishelled Mn3O4 hollow spheres for enhanced performance of supercapacitors. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2019, 7, 6686–6694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, R.S.; López-Díaz, D.; Velázquez, M.M. Graphene Oxide Thin Films: Influence of Chemical Structure and Deposition Methodology. Langmuir 2015, 31, 2697–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claramunt, S.; et al. The Importance of Interbands on the Interpretation of the Raman Spectrum of Graphene Oxide. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2015, 119, 10123–10129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Díaz, D.; et al. Evolution of the Raman Spectrum with the Chemical Composition of Graphene Oxide. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2017, 121, 20489–20497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Diaz, D.; Merchán, M.D.; Velázquez, M.M. The behavior of graphene oxide trapped at the air water interface. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2020, 286, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; et al. Graphene-manganese oxide hybrid porous material and its application in carbon dioxide adsorption. Chinese Science Bulletin 2012, 57, 3059–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-H.; et al. Structural Evolution of Hydrothermally Derived Reduced Graphene Oxide. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 6849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubinin, M.M. Adsorption properties and microporous structures of carbonaceous adsorbents. Carbon 1987, 25, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.; Do, D.D. The Dubinin–Radushkevich equation and the underlying microscopic adsorption description. Carbon 2001, 39, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; et al. Carbon Nanotube/Manganese Oxide Ultrathin Film Electrodes for Electrochemical Capacitors. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3889–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Díaz, D.; et al. Towards Understanding the Raman Spectrum of Graphene Oxide: The Effect of the Chemical Composition. Coatings 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radinger, H.; et al. Manganese Oxide as an Inorganic Catalyst for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction Studied by X-Ray Photoelectron and Operando Raman Spectroscopy. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noviyanto, A.; et al. Anomalous Temperature-Induced Particle Size Reduction in Manganese Oxide Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 45152–45162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.J.; et al. Oxygen functional groups and electrochemical capacitive behavior of incompletely reduced graphene oxides as a thin-film electrode of supercapacitor. Electrochimica Acta 2014, 116, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; et al. Carbon nanotube@Mn3O4 composite as cathode for high-performance aqueous zinc ion battery. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2022, 898, 162747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Mousavi-Khoshdel, S.M. Preparation of a Cu-Doped Graphene Oxide–Glutamine Nanocomposite for Supercapacitor Electrode Applications: An Experimental and Theoretical Study. ACS Applied Electronic Materials 2024, 6, 4108–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, B.; et al. Capacitance and surface of carbons in supercapacitors. Carbon 2017, 122, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, C.H.; Kim, D.; Bai, B.C. Correlation of EDLC Capacitance with Physical Properties of Polyethylene Terephthalate Added Pitch-Based Activated Carbon. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; et al. Unveiling the electrochemical advantages of a scalable and novel aniline-derived polybenzoxazole-reduced graphene oxide composite decorated with manganese oxide nanoparticles for supercapacitor applications. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 73, 109109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

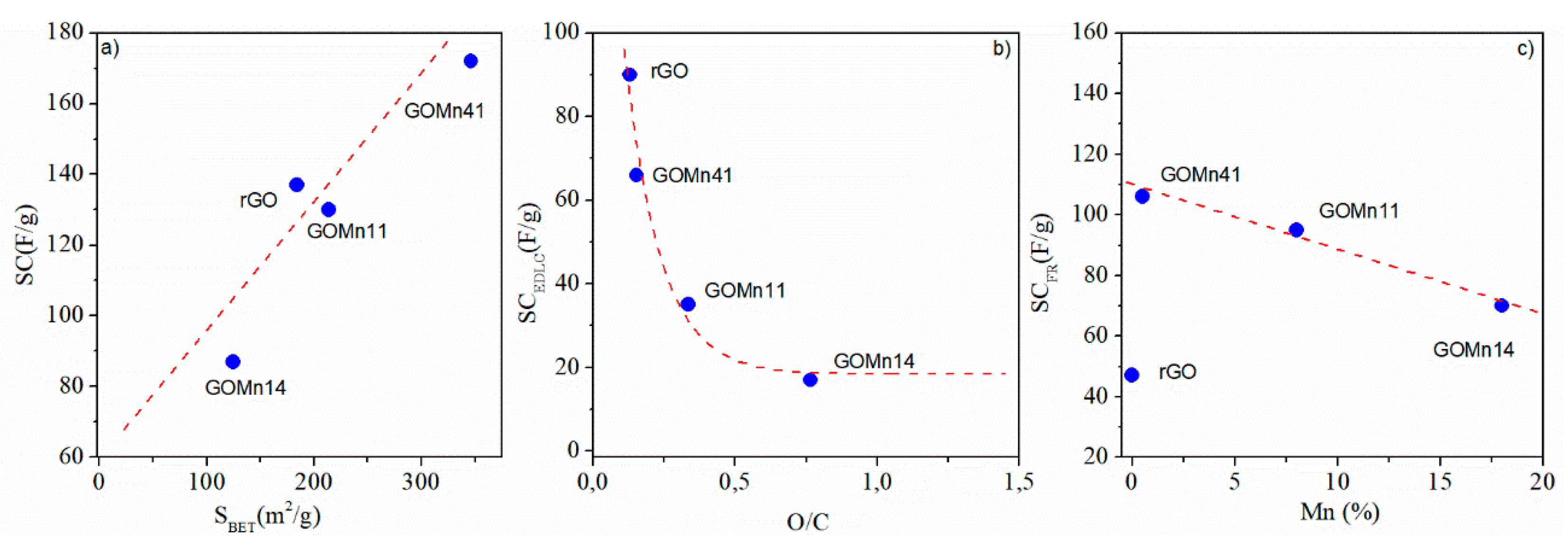

| Materials | C1s Atomic (%) |

O1s Atomic (%) |

Mn2p Atomic (%) |

O/C | SBET (m2/g) |

VMP (cm3/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rGO | 88.4 ± 3 | 11.5 ± 0.9 | --- | 0.13 | 184 | 0.06 |

| GOMn41 | 86.2 ± 4 | 13.2 ± 0.6 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.15 | 346 | 0.10 |

| GOMn11 | 68.8 ± 3 | 23.1 ± 1 | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 0.33 | 214 | 0.06 |

| GOMn14 | 46.4 ± 2 | 35.5 ± 2 | 18.0 ± 0.9 | 0.77 | 125 | 0.04 |

| KOH 1M (3 electrodes cell) |

Et4NBF4/CAN (2 electrodes cell) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials | SC (F g-1) |

E (W h kg-1) |

P (W kg-1) |

SC retention after 500 cycles (%) |

SCEDLC (F g-1) |

| rGO | 137 ± 27 | 27 | 736 | 73 ± 15 | 90 ± 18 |

| GOMn41 | 173 ± 34 | 34 | 753 | 76 ± 15 | 66 ± 13 |

| GOMn11 | 136 ± 26 | 26 | 761 | 74 ± 15 | 35 ± 7 |

| GOMn14 | 89 ± 17 | 17 | 768 | 71 ± 14 | 17 ± 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).