1. Introduction

Fungi are integral components of many ecosystems. Many fungi produce sporocarps, macroscopic structures in which sexual spores develop and from which spores are released. Fungi play many roles in nature: predators, parasites, mutualists, and/or recyclers. A given fungal species may be a mycorrhizal companion of nearby plants, food and shelter for developing invertebrates, and may itself be parasitized by microorganisms, while also consuming bacteria and benefiting from bacterial breakdown products. Mycetophagous flies in turn may consume fungal material (mycelia or fruiting bodies) and utilize volatiles from fungal pathogens or bacterial breakdown products to select optimal oviposition sites [

1].

Wild sporocarp-forming fungi are populated with a rich diversity of dipterans [

2]. In the northeastern United States the fruiting structures of the fungal genus

Agaricus are predominantly colonized by drosophilids, and to a lesser extent, by phorids and tipulids [

3]. In contrast, only a handful of fly species are considered economic pests of mushroom production worldwide. Fly pests are predominantly from the families Phoridae, Sciaridae, and Cecidae (in some places Drosophilidae are also problematic) [

4,

5]. In Pennsylvania mushroom farms, the two major pest species are

Lycoriella ingenua (Dufour 1839) and

Megaselia halterata (Santos Abreu, 1921) [

6].

Agricultural monocultures are optimized for maximum crop yield, but are also susceptible to opportunistic colonization by pest species that can establish themselves, as well as the pathogens and pests they may transmit. Mushroom houses serve as an ideal experimental environment in which to study the dynamics of microbe-fly-cultivated crop interactions when conditions are optimized for mushroom crop production. Here we describe our investigation into the bacterial communities of adult Lycoriella ingenua (Diptera: Sciaridae) and phorid Megaselia halterata (Diptera: Phoridae) collected from button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) production houses in Pennsylvania.

These two pest species have distinct but overlapping biologies.

L. ingenua consume the compost material (and any associated microbes) prior to addition of mushroom spawn [

7]. Once the compost is fully colonized by

Agaricus bisporus, the populations of

I. ingenua decline [

8]. In contrast, populations of

M. halterata thrive on mycelial growth, gradually building up from Spring until Fall and then declining when mushrooms are harvested and beds replaced [

9]. We predicted that there would be some overlap in bacterial community composition between the two fly species, but we suspected there would be differences that might be unique to each fly species. We collected specimens of each species, extracted their nucleic acids, and sequenced the bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences using the Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform. While we did detect some overlap in bacterial diversity, we additionally identified two phylogenetically distinct

Wolbachia sequences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection Sites and Sampling

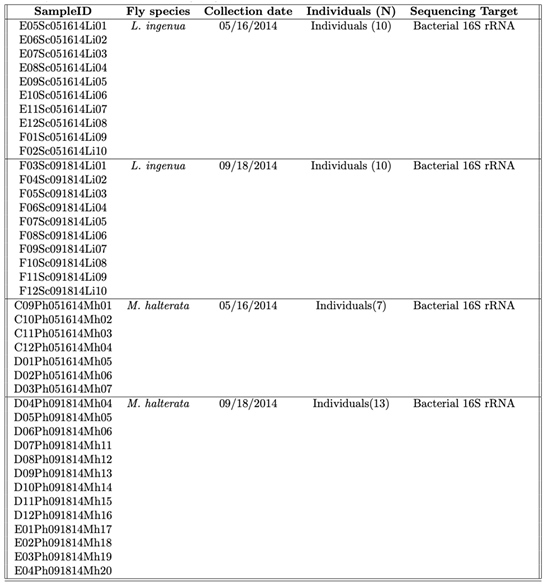

We collected

Lycoriella ingenua and

Megaselia halterata adults by aspiration from two mushroom production houses in Kennett Square, Chester County, PA, at two times (May and October of 2014;

Table 1). Flies were collected in separate vials by species (

L. ingenua or

M. halterata) and transported alive on ice to University Park, PA to prevent damage to the nucleic acids. Flies were then placed at -80 C until processed.

2.2. Sample Processing for Bacterial 16S rRNA Sequencing

We extracted genomic DNA from 40 individual flies (

Table 1) and sequenced the v4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene to describe the bacterial community composition. DNA extractions were conducted using the Omega E.Z.N.A. Tissue DNA kit (SKU\#: D3396) following the manufacturer’s suggested protocol. Barcoded PCR of the v4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene, followed by sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform.

2.3. Analysis of Bacterial Communities of Flies

Sequences were aligned, filtered to remove chimeric sequences, and analyzed in RStudio using Dada2 and Phyloseq, followed by further refinements using the R/Bioconductor framework “miaverse” [

10]. Reads were assigned taxonomic identity using the Dada2 taxonomy assigner and Silva (v138) reference database of eubacterial 16S ribosomal RNA sequences [

11,

12,

13]. After an initial analysis, we detected taxa that matched mitochondrial sequences or were suspected to be contaminants from other samples sequenced in the same run (see “Post-Illumina sequence confirmation and phylogenetic placement of

Wolbachia sequences”). Thereafter, we filtered out reads matching “mitochondria”, “

Rickettsia”, and “

Rickettsiella” before continuing with diversity analyses. Shannon and inverse Simpson indices were used for measuring richness and evenness. Statistical comparisons within species were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Community dissimilarity (Bray-Curtis index) was evaluated between groups. Multidimensional scaling analyses (MDS) were calculated and plotted to visualize bacterial community structure between groups using Phyloseq. Statistical comparison between groups was performed to run permutational multivariate analyses of variance (PERMANOVA using 999 permutations). The significance level was set to 0.05.

2.4. Post-Illumina Sequence Confirmation & Phylogenetic Placement of Wolbachia Sequences

Our samples were sequenced with samples from other arthropod studies (two different mosquito species and a tick species). Because of this, it was important to confirm the presence of the three bacterial genera that were also detected in one or more of those arthropod hosts. We used PCR primers for

Rickettsia,

Rickettsiella, and

Wolbachia [

14,

15]. We did not detect the presence of

Rickettsia or

Rickettsiella, both of which were taxa in high abundance in tick samples sequenced on the same run. However, we did detect fragments of

Wolbachia 16S rRNA using primers W-Specf (5’\-CATACCTATTCGAAGGGATAG\-3’) and W-Specr (5’\-AGCTTCGAGTGAAACCAATTC\-3’) to amplify a 438 bp fragment [

14]. Amplicons from four fly samples (2 of each fly species) were gel-separated, purified, and submitted for Sanger sequencing. Amplicons were aligned to known GenBank deposited sequences of

Wolbachia, trimmed to 330 bp to eliminate indels, and phylogenies estimated using Maximum Likelihood with MEGA X using the best-estimated model of evolution selected by jmodeltest [

16,

17].

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial Community Composition

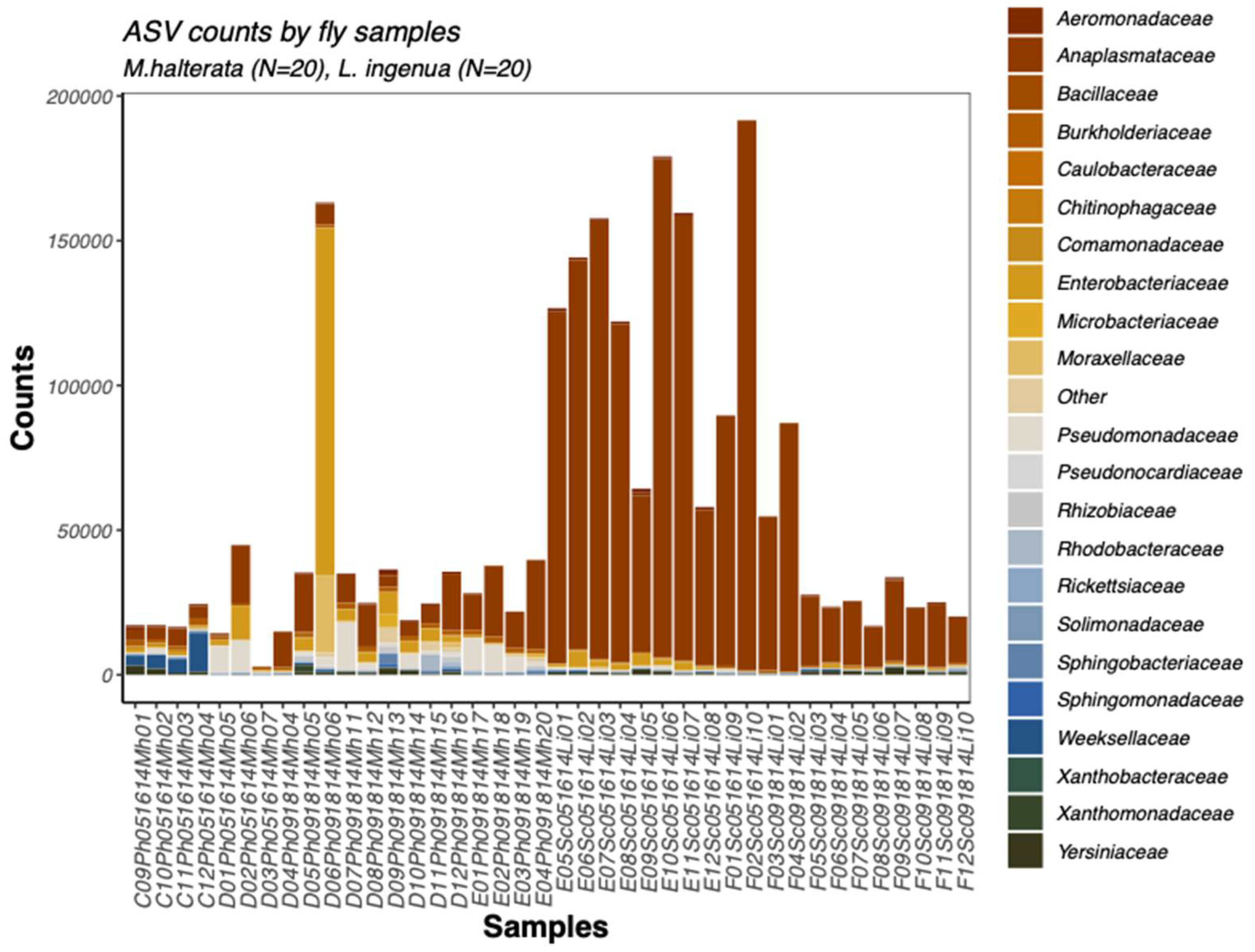

In total, 2,389,953 16S rRNA reads passed quality control and chimera checking. Read counts were higher from

L. ingenua (1,695,053) than

M. halterata (694,900) (

Figure 1). Reads matching

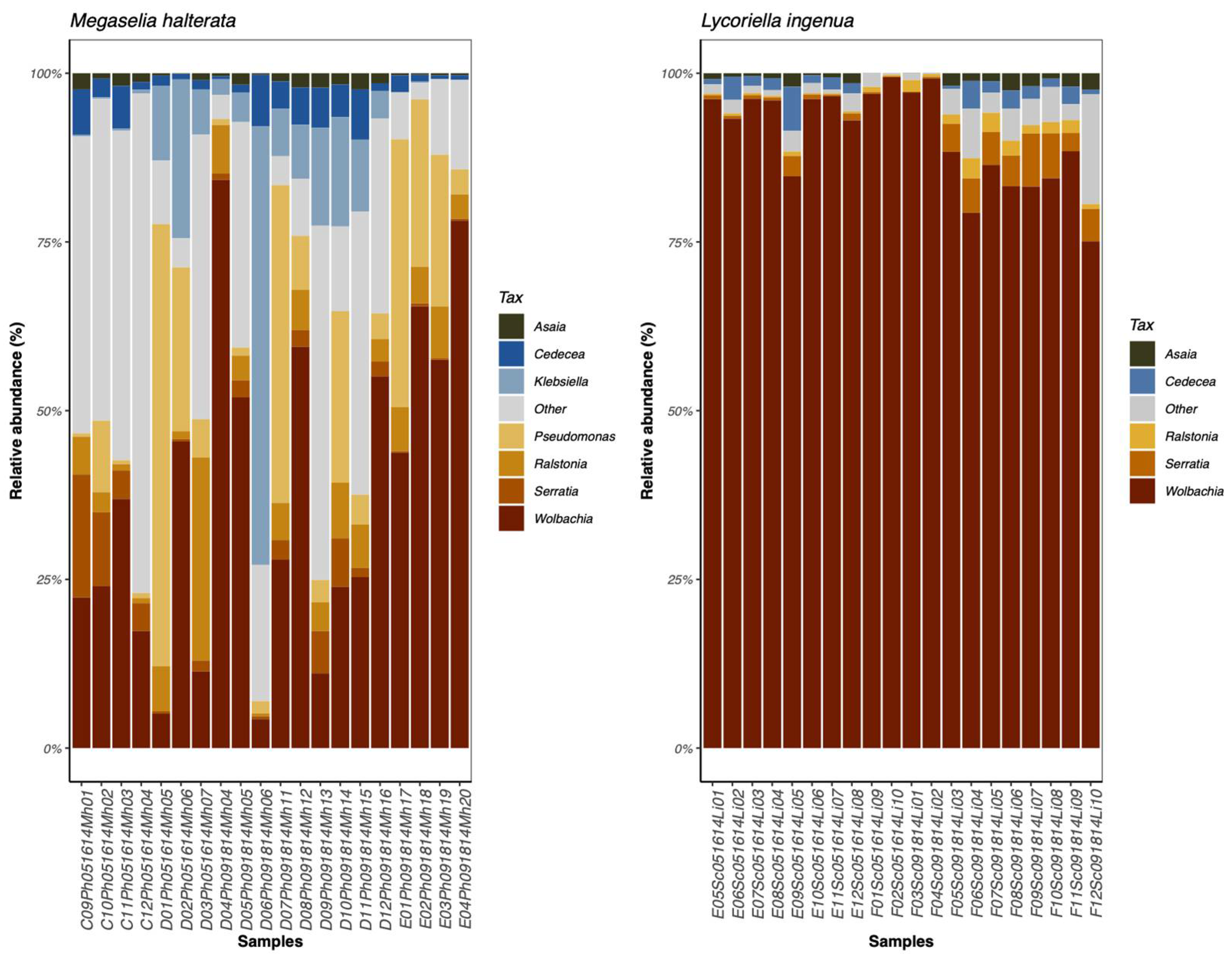

Wolbachia were found in all individual flies from both species.

Wolbachia was the dominant taxon in all individuals of

L. ingenua. In

M. halterata the abundance of

Wolbachia was variable and did not always represent the dominant taxon.

Klebsiella,

Pseudomonas,

Ralstonia were often more abundant in

M. halterata than in

L. ingenua) (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

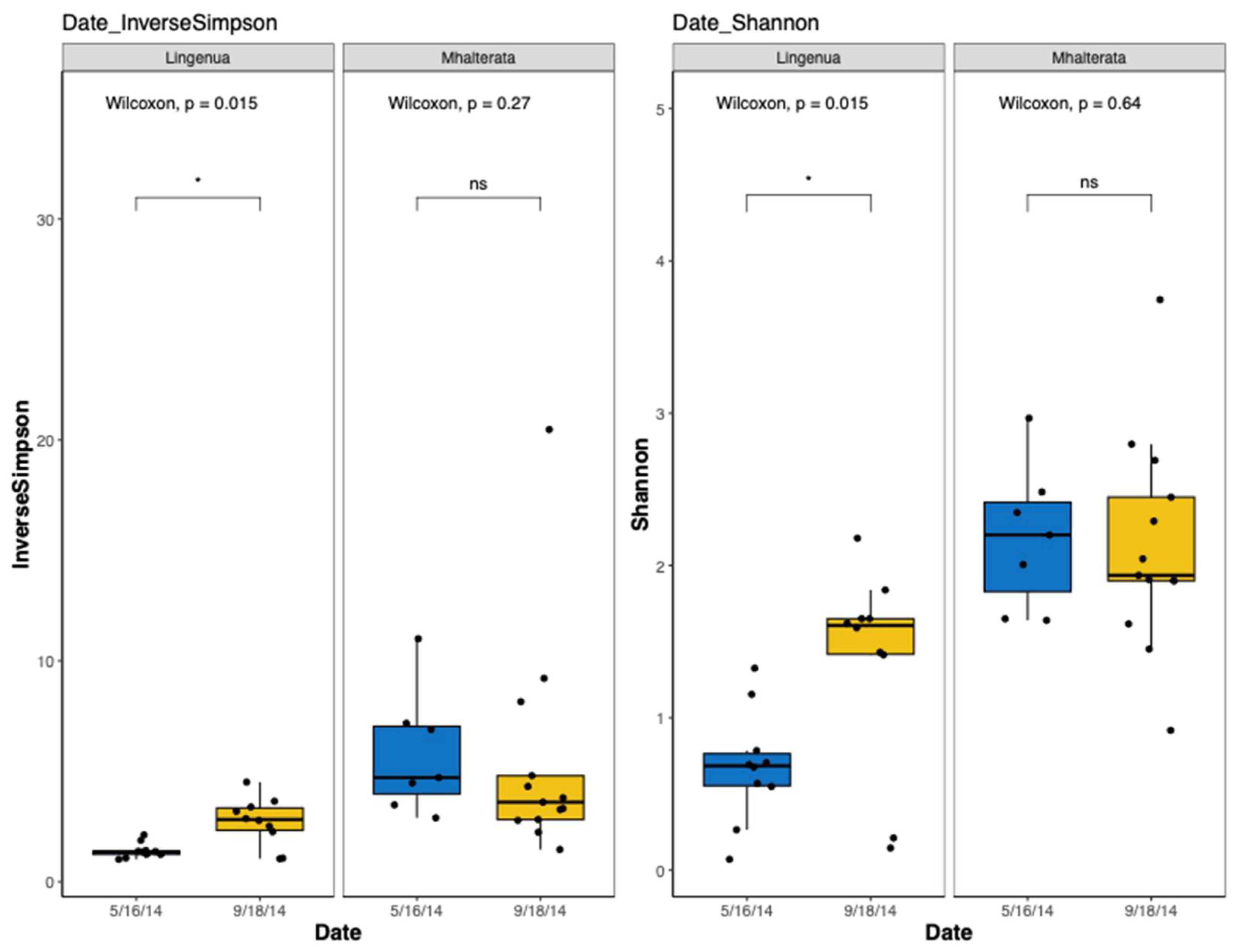

3.2. Bacterial Diversity

L. ingenua microbiota are not evenly distributed and fewer taxa (lower richness) were identified than observed in

M. halterata. We detected significant differences in diversity between collection times in

L. ingenua, but not in

M. halterata (

Figure 4). While the alpha diversity measures of

L. ingenua individuals differed between May and September collections, this was not the case for

M. halterata (most

M. halterata bacterial taxa clustered together regardless of dates).

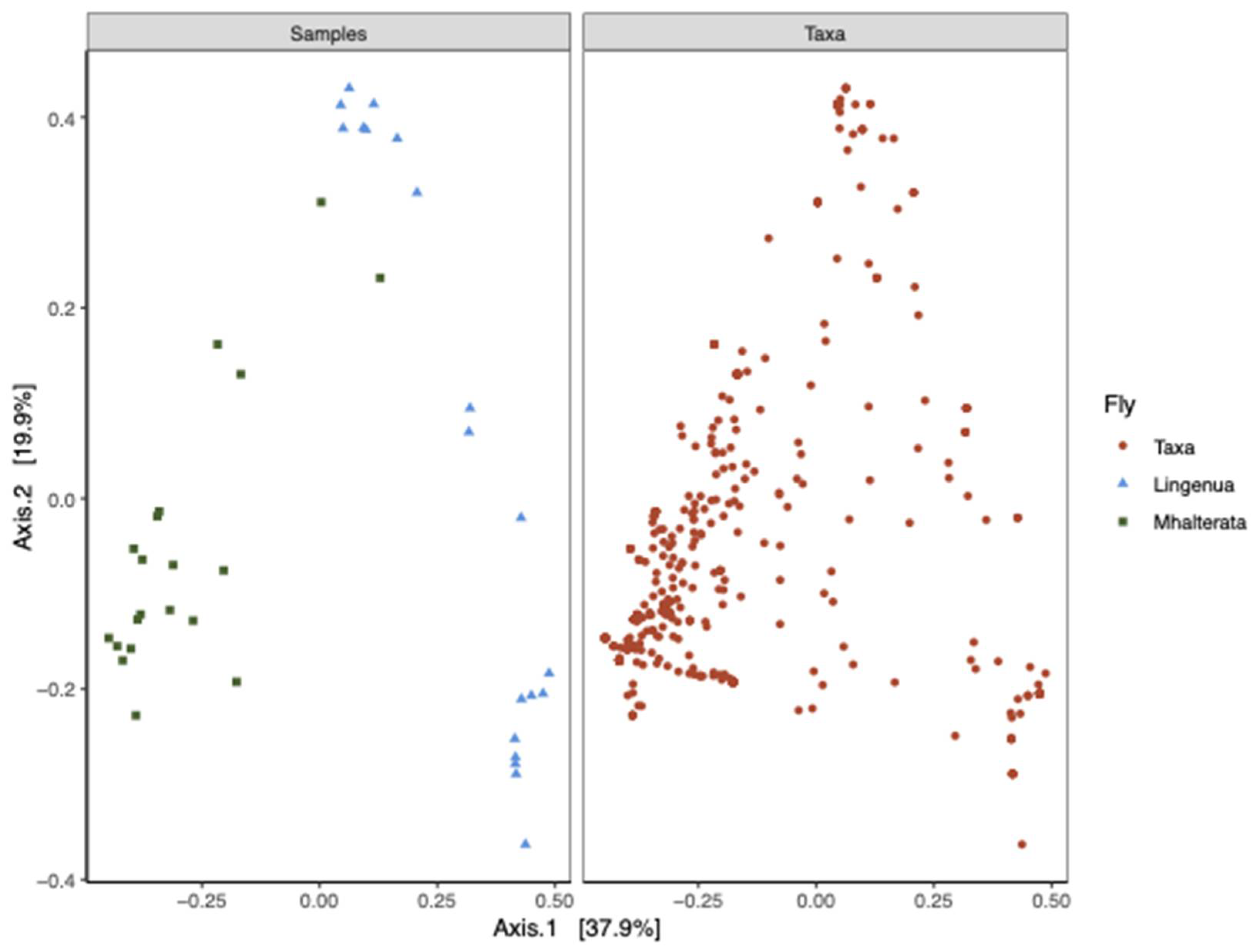

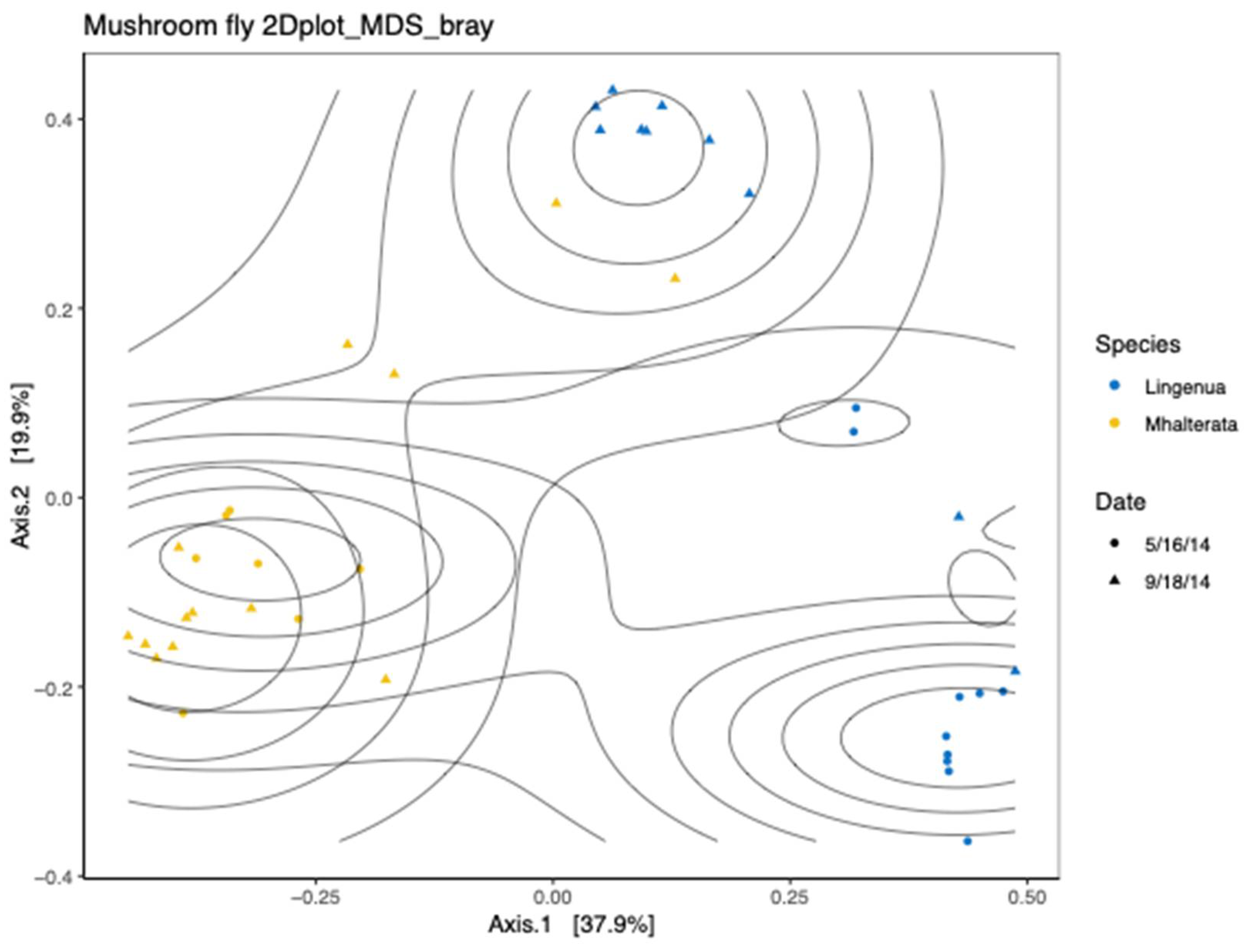

When we examined the beta diversity, we observed that the diversity measures of the two species were distinct from each other, although there was some clustering between fly species that corresponded to the fall collection (

Figure 5). We confirmed that there was a significant interaction between fly species and collection date using a Permanova analysis (Species

p=0.001; Date

p= 0.022; Species*Date

p=0.008). We therefore analyzed the two species separately to confirm the effect of the collection date. In both species, there was a significant effect of collection date (Li, R2=0.36726,

p>0.005; Mh, R2=0.13511,

p>0.003).

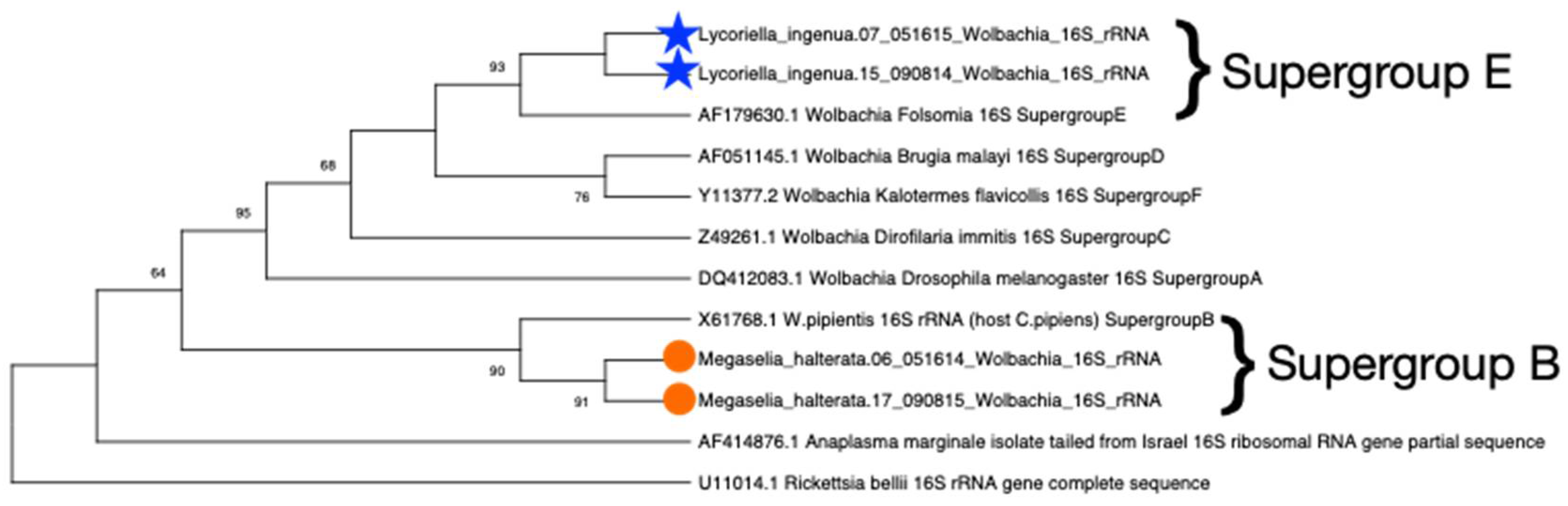

3.3. Sequence Confirmation and Phylogenetic Placement of Wolbachia Sequences

Fragments of

Wolbachia 16S rRNA sequences from four samples (two from each fly species) were amplified, gel-purified, and submitted for Sanger sequencing. We confirmed that the

Wolbachia sequences identified in the dataset were not due to sequence contamination and that the isolates from each fly species were from phylogenetically distinct clades (Supergroup E for

L. ingenua and Supergroup B for

M. halterata) (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

Bacterial community compositions were distinct for each fly pest species. We also observed an effect of collection date, particularly in

L. ingenua. The two collection dates were chosen to compare spring versus fall population increases and fall mating behavior may have contributed to the difference in bacterial communities. It has been speculated that

M. halterata adults, which leave the mushroom houses in fall to mate, may maintain populations outside of mushroom houses during the fall, although evidence of phorid presence was not detected in adjacent residential properties [

18].

Because bacterial read counts were much higher from

L. ingenua than

M. halterata (

Figure 1), it was important to consider this when interpreting differences in microbial communities between fly species. For instance,

Serratia was found in higher absolute abundance in

L. ingenua, but this only accounted for proportionally less than 10% of the total OTU abundance. On the other hand, the dominant bacterial taxon detected in both fly species was confirmed to be

Wolbachia. Absolute and relative abundance of

Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, and

Ralstonia were higher in

M. halterata than

L. ingenua.

Wolbachia occurred at higher relative (and absolute) abundance in

L. ingenua than in

M. halterata. It is not unusual to find

Wolbachia in fly species. However, phylogenetic analysis suggests that the

Wolbachia found in both fly species may have been acquired independently.

Wolbachia sequences contained in the fly species were determined to be from different clades. The presence of

Wolbachia in both fly species was confirmed (post-Illumina sequencing) because of a concern that the sequences represented contamination from mosquito samples that were also sequenced in the same run. However, while the

M. halterata Wolbachia was from a similar clade to

Culex pipiens Wolbachia, it was distinct from the

Wolbachia sequenced from the mosquito samples. Further, the

Wolbachia identified in

L. ingenua was from a completely different cluster (within the Supergroup E clade), a clade that has been previously associated primarily with springtails and several mite species [

19,

20]. One predatory mite (

Hypoaspis aculeifer) known to be an effective biocontrol agent against both species of flies, was not observed or known to be in these mushroom houses, but even if it was present, it is not a species known to harbor

Wolbachia [

21,

22]. Since the sequencing was conducted on whole flies (flies were too small to dissect for sufficient DNA for sequencing), we cannot exclude the possibility that the

Wolbachia detected came from infected springtails or mites that may have been consumed by fly larvae in the mushroom mats. Whether or not the

Wolbachia found in

L. ingenua existed in the flies as a co-evolved associate, or acquired through horizontal transfer through interactions with other organisms in mushroom beds (e.g. springtails or mites) needs further research.

Lastly,

Pseudomonas is a ubiquitous bacterial taxon and several species of

Pseudomonas have been described from mushroom farms. Its presence was therefore not a surprise in our sequence data. While some species of

Pseudomonas are important enhancers of mushroom development (metabolizing compost compounds that might otherwise inhibit

A. bisporus primordial development), other species (e.g.

P. tolaasii and

P. reactans) are known pathogens [

23]. Although we detected

Pseudomonas in both fly species, we did not isolate or characterize them and cannot ascribe their nature as pathogenic, beneficial, or commensal within the mushroom house microbiome.

4.2. Limitations of the Study

Because bacterial metagenomic sequencing was performed on samples collected in different years, we cannot make any conclusions about the interactions of the bacteria in the microbial communities of their respective fly host. We cannot speculate whether the Wolbachia detected in this study caused sex ratio distortion or reproductive effects because we did not separate the males or females. We do not know the extent to which the microbial communities of flies and the mushrooms are shared, nor how they influence the behavior of the flies, nor can we determine the interactions of fly microbiota on secondary ecological interactions such as on parasitoids of mushroom flies, springtails, predatory mites, or nematodes.

4.3. Future Studies

Cultivated button mushroom farming represents a rich microbial ecosystem under fairly homogeneous environmental conditions. The current study connects one more piece of the multi-trophic ecological puzzle, but many questions are still unanswered. For instance, can the interactions and dynamics of mushroom flies with other microbial (e.g. viruses or nematodes) or invertebrate associates be used to facilitate the biocontrol of flies, or bacterial pathogens, or fungal pathogens of mushroom houses?

The purpose of the exploration of mushroom fly microbial dynamics was to identify biocontrol options in a cultivated setting. A broader ecological question we could not ignore was: What are the factors that dictate which fly species becomes a pest? Wild mycophagous flies are dependent on a resource whose abundance is heavily affected by rainfall and other variables. Thus, resource unpredictability would likely favor polyphagy, not host specialization in mycophagous flies [

1]. The diversity of mycophagous fly taxa encountered in wild mushrooms reflects this and represents an arena for resource competition. Wild mushrooms (

Agaricus spp. in particular) in the Northeastern United States are largely colonized by mycophagous drosophilids (

Drosophila and

Leucophenga spp.), wood gnats, mushroom flies, and crane flies [

1,

3]. While a limited food source (e.g. single basidiocarp) might result in inter- and intraspecies competition and subsequent reduction in size, an effectively inexhaustible food source (such as a mushroom house) would likely favor mushroom flies.

In theory, any mycophagous fly in the vicinity should benefit from such an abundance of resources. Yet, in Pennsylvania mushroom houses only Phoridae and Sciaridae (specifically the two species in this study) are of concern as pests, although in other regions of the country, other fly species may become problematic (Cecidomyiidae;

Mycophila speyeri) and

Heteropeza pygmaea), house and stable flies (as nuisance pests of compost heaps), and members of the Drosophilidae) [

5]. Some cultivation practices and control practices may exclude some of these species, but one future study includes an in-depth investigation of the multitrophic dynamics of fly colonization of wild mushrooms in adjacent wooded areas to identify possible explanations for the exclusion/establishment of other fly species in cultivated settings.

Mushroom cultivation began in the 1600s, but structures or caves were not used until the early 1900s [

24]. Modern mushroom houses were started in the early 1900s, but were quickly plagued by sciarid pests [

25]

. While earlier attempts at control included chemical applications, the quick development of resistance necessitated changes in cultivation practices and biocontrol agents as integrated pest management strategies [

26,

27]

. Cultivation practices such as compost pasteurization and the use of chemicals and biocontrol agents (e.g. predatory mites, entomopathogenic nematodes and fungi) can help control fly pests, but exclusion is preferred [

21,

28,

29]

. It should be noted that pasteurization alone may not be sufficient, as adult female sciarid (L. ingenua) are attracted to compost and the volatiles released by pathogenic molds [

30]

.

What role Wolbachia play in the lifecycle of either of these fly species is unknown. Further studies would include attempts to cure colonized flies of Wolbachia infections and determine whether/how this affects biology, behavior, or pathogen vector competence. We can also determine the population genetics of the Wolbachia isolates in mushroom houses and in wild mushroom populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and sample collection, JS and JR; methodology, and literature review, JS and IS; data analysis and visualization, JS; manuscript writing and editing, JS, IS, JR; funding acquisition, JS and JR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Institute of Food and Agriculture and Hatch Appropriations under Project #PEN04912 (Accession #7006384) and Project #PEN04769 (Accession #1010032). Additional funds to JS and JR were provided from the Giorgi Mushroom Research Fund. JR was partially supported by the Dorothy Foehr Huck and J. Lloyd Huck endowment.

Data Availability Statement

Sanger sequences of Wolbachia 16S rRNA fragments can be found at Genbank Accession # PP549140-PP549143. Illumina sequences of bacterial 16S rRNA sequences from fly samples are at Genbank under Bioproject Accession # PRJNA1093092.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Claire Thomas for lessons and discussions on fly rearing in general (and Drosophila in particular). The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their time and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grimaldi, D.; Jaenike, J. Competition in Natural Populations of Mycophagous Drosophila. Ecology 1984, 65, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovlev, J. Fungal Hosts of Mycetophilids (Diptera: Sciaroidea Excluding Sciaridae): A Review. Mycology 2012, 3, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunyard, B.A. Biodiversity and Ecology of Mycophagous Diptera in Northeastern Ohio. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 2003, 105, 847–858. [Google Scholar]

- Stamets, P.; Chilton, J.S. The Mushroom Cultivator: A Practical Guide to Growing Mushrooms at Home; Agarikon Press ; Western distribution by Homestead Book Co: Olympia, Wash. : Seattle, Wa, 1983. ISBN 978-0-9610798-0-2.

- Willette, A.; Van Slambrook, L.; Hollingsworth, C. Mushroom Pests: Mushroom-Mushroom Fly. In Pacific Northwest Insect Management Handbook [online]; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wuest, P.J.; Bengtson, G.D.; Schisler, L.C. Pennsylvania State University College of Agricultural Sciences Penn State Handbook for Commercial Mushroom Growers: A Compendium of Scientific and Technical Information Useful to Mushroom Farmers; Penn State, College of Agricultural Sciences University Park, PA: University Park, PA, 2003.

- Jess, S.; Murchie, A.K.; Bingham, J.F.W. Potential Sources of Sciarid and Phorid Infestations and Implications for Centralised Phases I and II Mushroom Compost Production. Crop Protection 2007, 26, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepmaker, J.W.A.; Geels, F.P.; Van Griensven, L.J.L.D.; Smits, P.H. Substrate Dependent Larval Development and Emergence of the Mushroom Pests Lycoriella Auripila and Megaselia Halterata. Entomologia Exp Applicata 1996, 79, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazin, M.; Andreadis, S.S.; Jenkins, N.E.; Cloonan, K.R.; Baker, T.C.; Rajotte, E.G. Activity and Distribution of the Mushroom Phorid Fly, Megaselia Halterata, in and around Commercial Mushroom Farms. Entomologia Exp Applicata 2019, 167, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, F.G.M.; Shetty, S.; Borman, T.; Lahti, L. Mia: Microbiome Analysis. 2023.

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucl. Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werren, J.H.; Windsor, D.M. Wolbachia Infection Frequencies in Insects: Evidence of a Global Equilibrium? Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 2000, 267, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, J.M.; Silva Diaz, G.E.; Wagner, E.A. Bacterial Communities of Ixodes Scapularis from Central Pennsylvania, USA. Insects 2020, 11, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More Models, New Heuristics and Parallel Computing. Nature Methods 2012, 9, 772–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikano, I.; Woolcott, J.; Cloonan, K.; Andreadis, S.; Jenkins, N.E. Biology of Mushroom Phorid Flies, Megaselia Halterata (Diptera: Phoridae): Effects of Temperature, Humidity, Crowding, and Compost Stage. Environ Entomol 2021, 50, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konecka, E.; Olszanowski, Z. Wolbachia Supergroup E Found in Hypochthonius Rufulus (Acari: Oribatida) in Poland. Infect Genet Evol 2021, 91, 104829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konecka, E.; Olszanowski, Z.; Koczura, R. Wolbachia of Phylogenetic Supergroup E Identified in Oribatid Mite Gustavia Microcephala (Acari: Oribatida). Mol Phylogenet Evol 2019, 135, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jess, S.; Bingham, J.F.W. Biological Control of Sciarid and Phorid Pests of Mushroom with Predatory Mites from the Genus Hypoaspis (Acari: Hypoaspidae) and the Entomopathogenic Nematode Steinernema Feltiae. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2004, 94, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütte, C.; Dicke, M. Verified and Potential Pathogens of Predatory Mites (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Exp Appl Acarol 2008, 46, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Zeid, M.A. Pathogenic Variation in Isolates of Pseudomonas Causing the Brown Blotch of Cultivated Mushroom, Agaricus Bisporus. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology: [publication of the Brazilian Society for Microbiology] 2012, 43, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, J. Cultivation in Western Countries: Growing in Caves. In The Biology and Cultivation of Edible Mushrooms; Elsevier, 1978; pp. 251–298 ISBN 978-0-12-168050-3.

- Insect Pest Control for the Amateur Mushroom Grower.; E-347; United States. Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine.: Place of publication not identified, 1935.

- Shamshad, A. The Development of Integrated Pest Management for the Control of Mushroom Sciarid Flies, Lycoriella Ingenua (Dufour) and Bradysia Ocellaris (Comstock), in Cultivated Mushrooms: IPM for Control of Sciarid Flies in Mushrooms. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2010, 66, 1063–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snetsinger, R.; Wuest, P. A Historical Perspective on Mushroom Arthropod Pest Control. In Developments in Crop Science; Elsevier, 1987; Vol. 10, pp. 641–648 ISBN 978-0-444-42747-2.

- Beyer, D.M.; Rinker, D. Nematode Problems in Mushroom Cultivation and Their Sustainable Management. In Nematode Diseases of Crops and their Sustainable Management; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 337–347 ISBN 978-0-323-91226-6.

- Andreadis, S.S.; Cloonan, K.R.; Bellicanta, G.S.; Paley, K.; Pecchia, J.; Jenkins, N.E. Efficacy of Beauveria Bassiana Formulations against the Fungus Gnat Lycoriella Ingenua. Biological Control 2016, 103, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloonan, K.R.; Andreadis, S.S.; Baker, T.C. Attraction of Female Fungus Gnats, Lycoriella Ingenua, to Mushroom-Growing Substrates and the Green Mold Trichoderma Aggressivum. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2016, 159, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).