Submitted:

22 May 2024

Posted:

23 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.1. Electrical Conductivity Literature

2.2. Glass Transition Temperature Literature

2.3. Raman Spectroscopy Literature

2.3.1. Borate Glasses

2.3.2. Silicate Glasses

2.3.3. Borosilicate Glasses

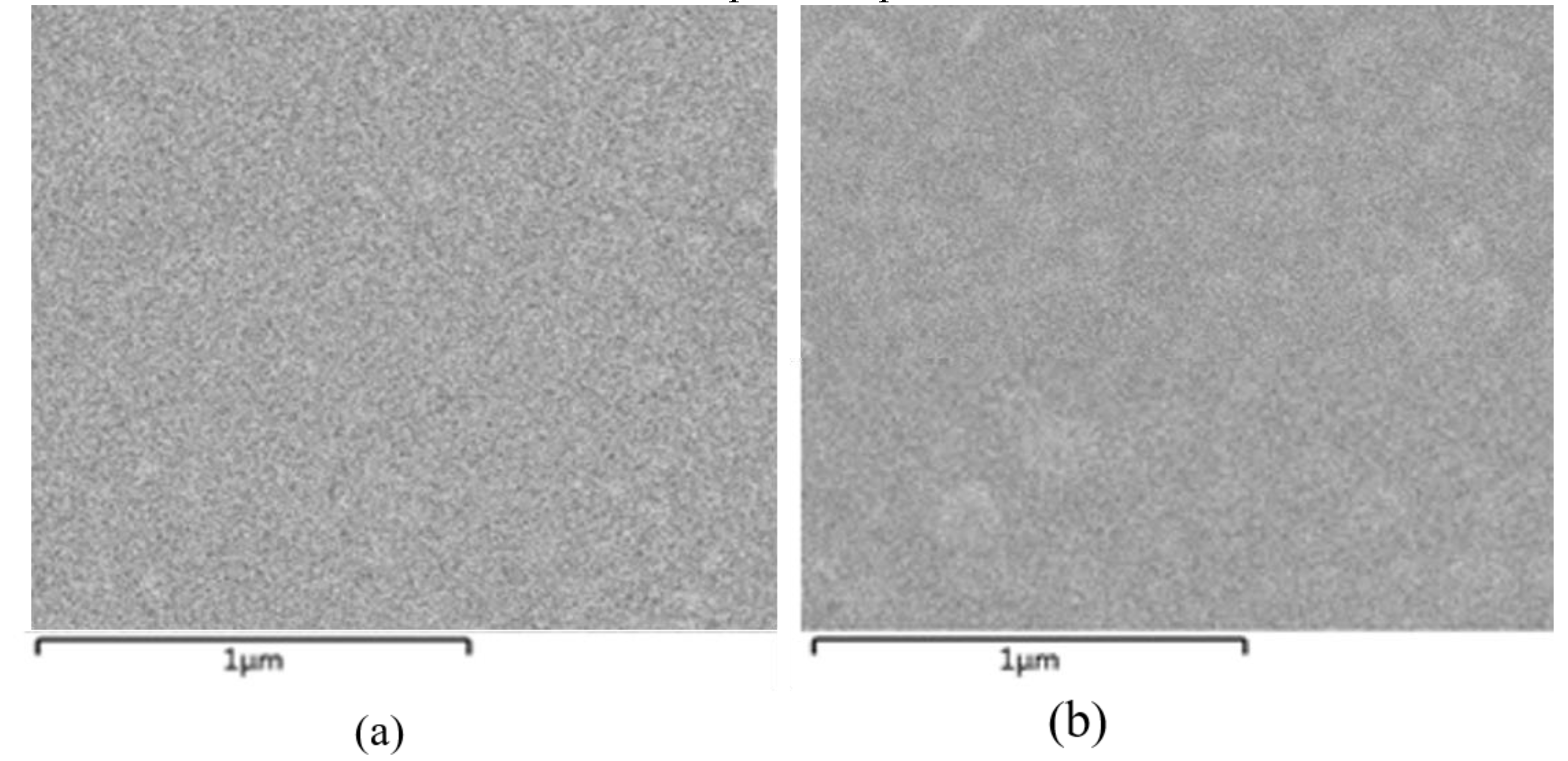

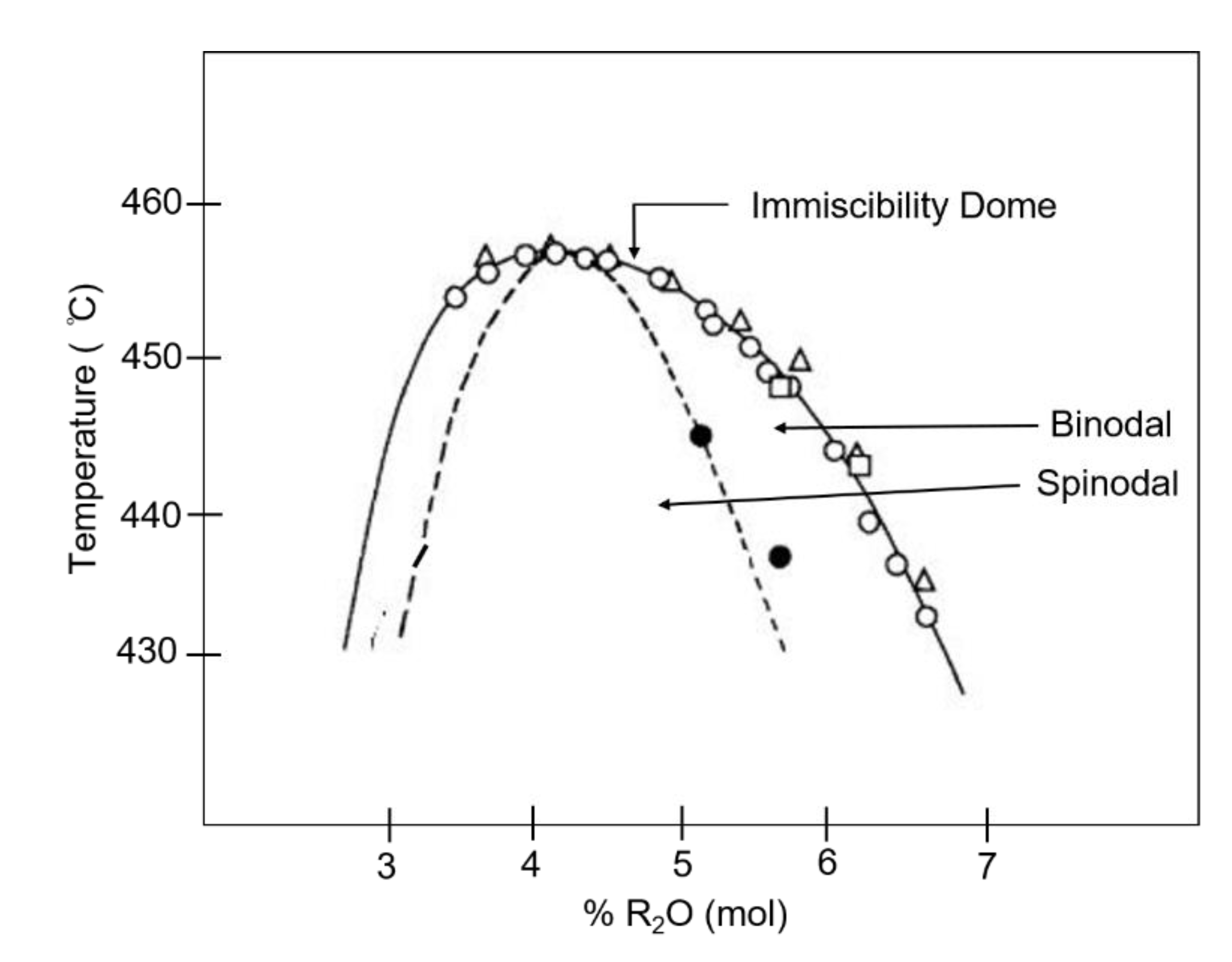

2.4. Spinodal Decomposition in Glasses

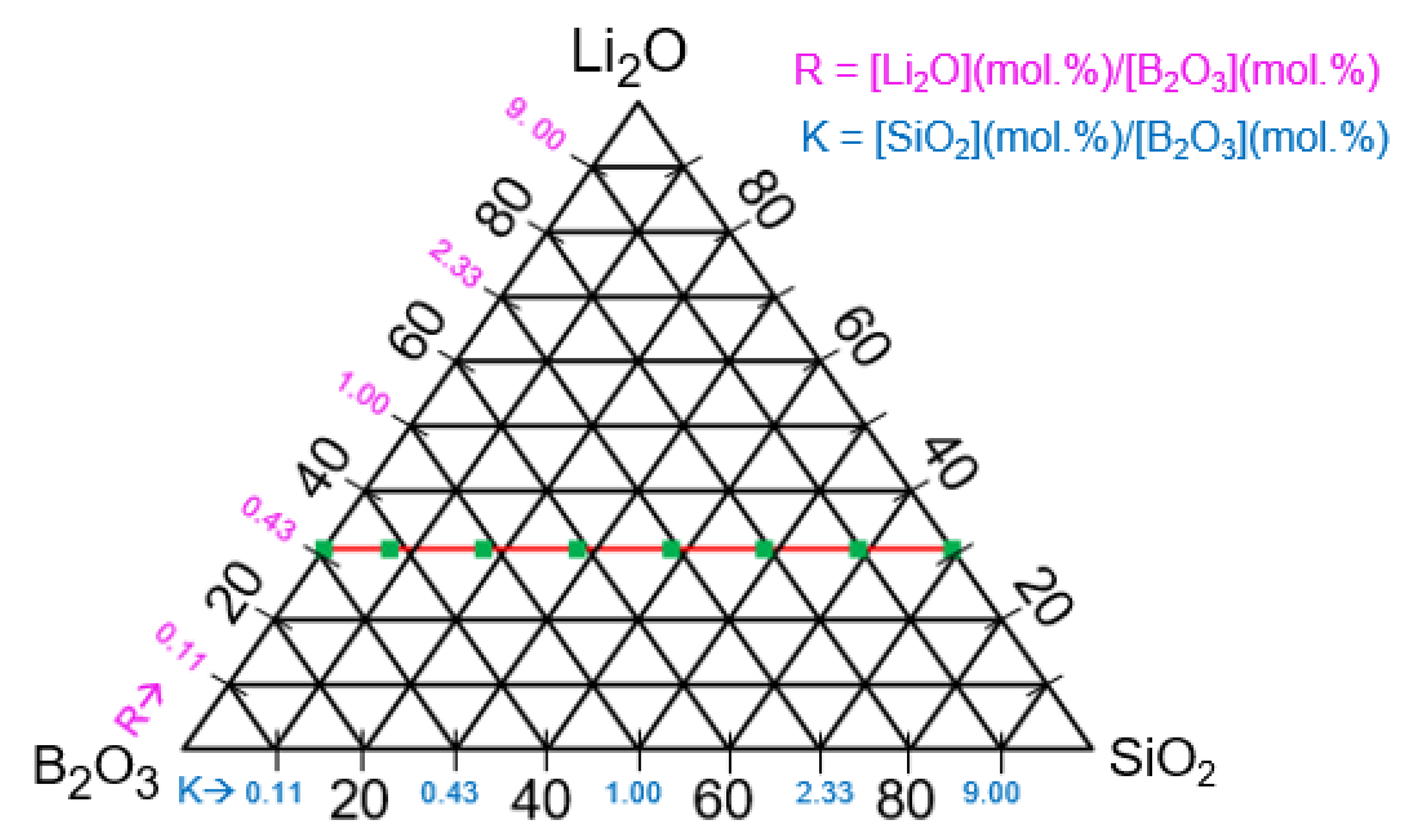

3. Experimental

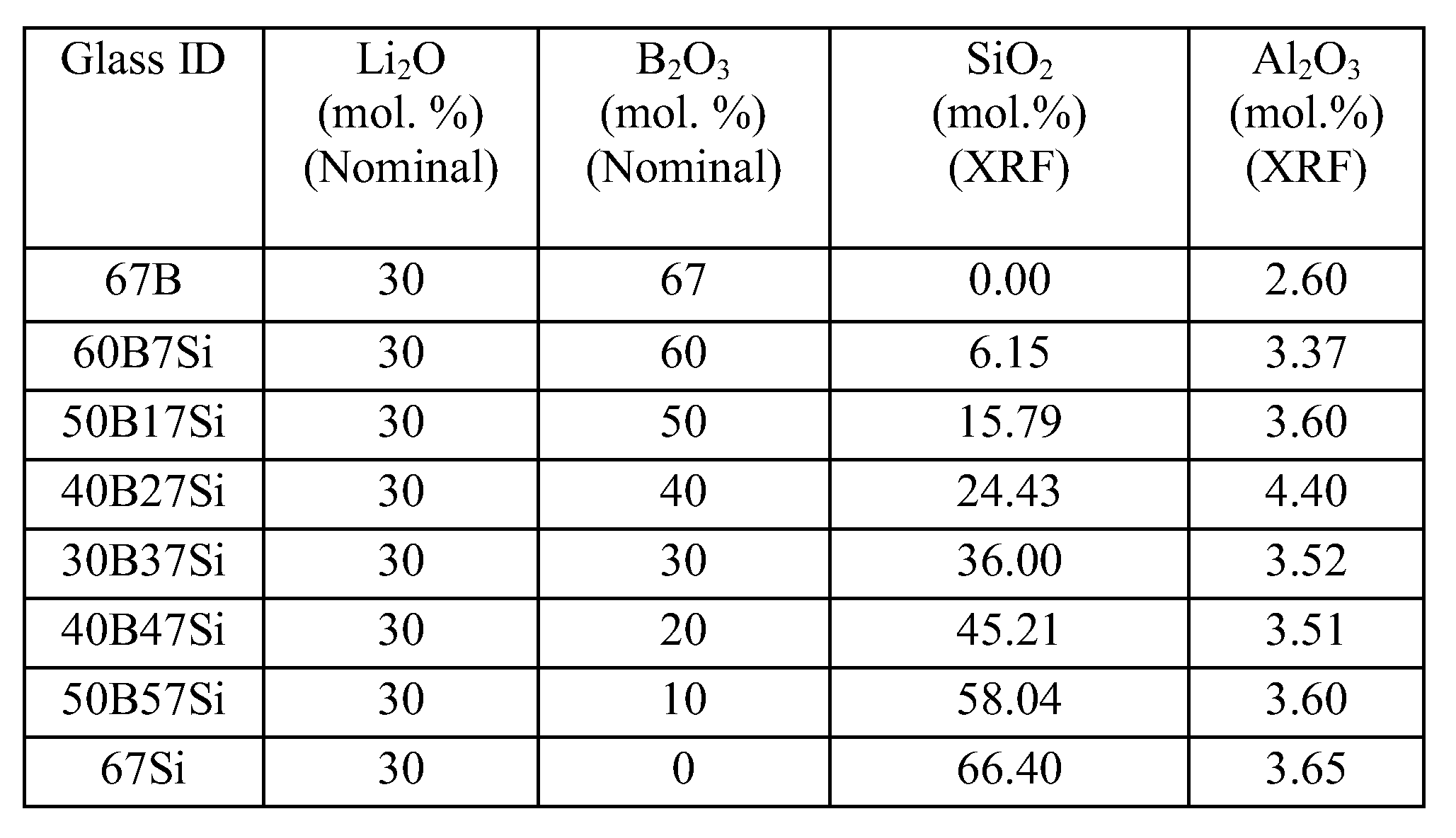

3.1. Glass synthesis

3.2. Electrical Conductivity Measurements

3.2. Raman Spectroscopy

4. Results

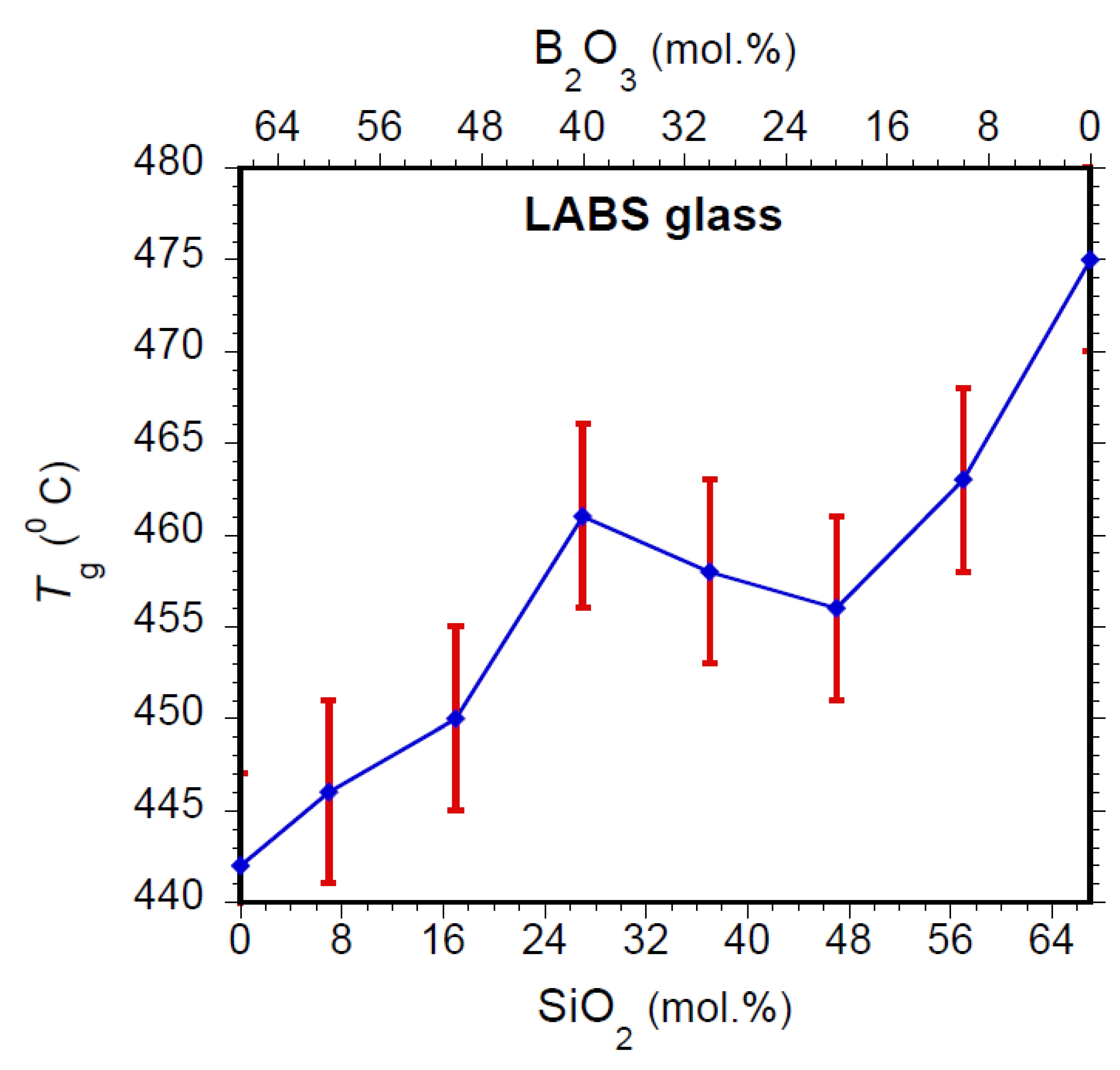

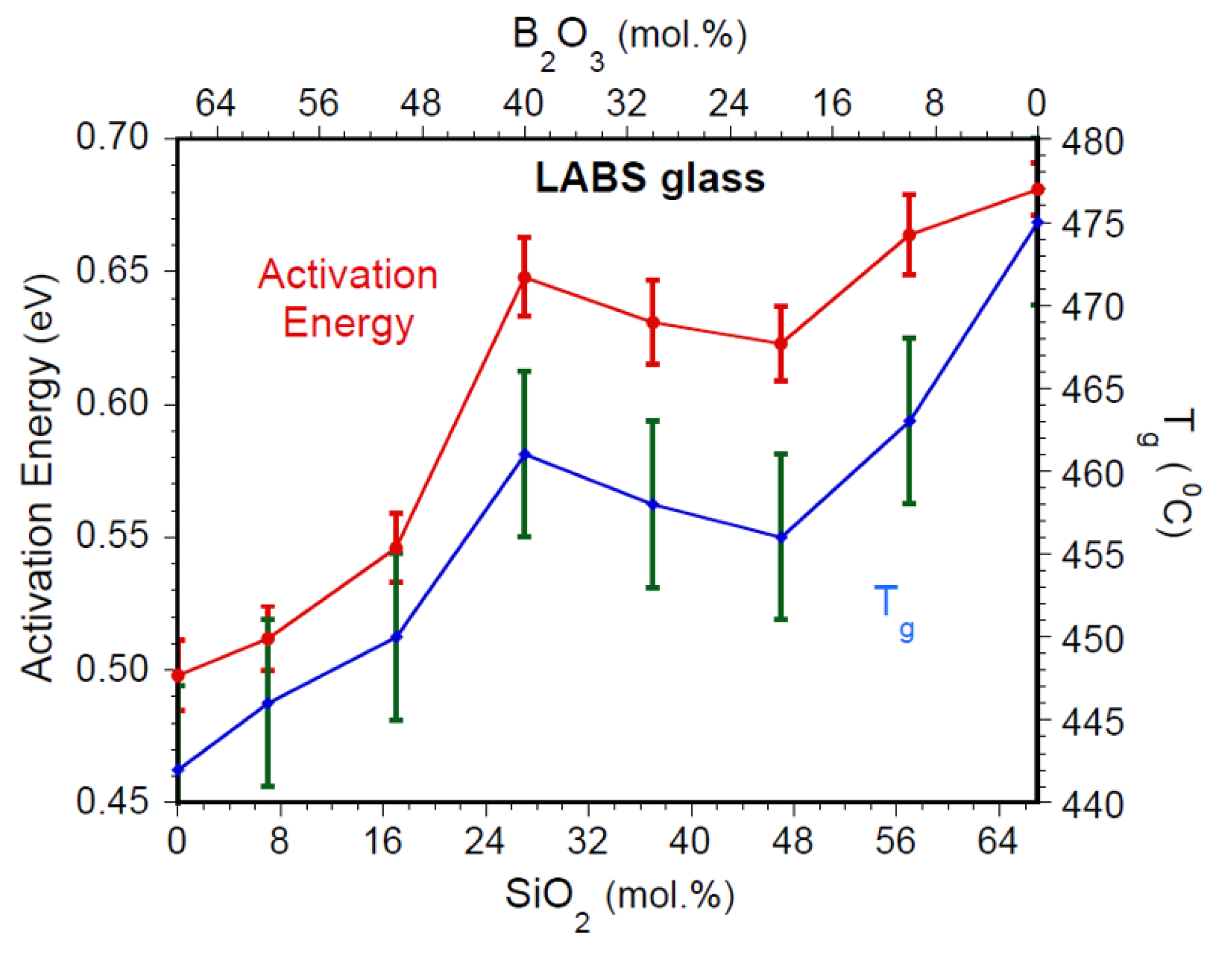

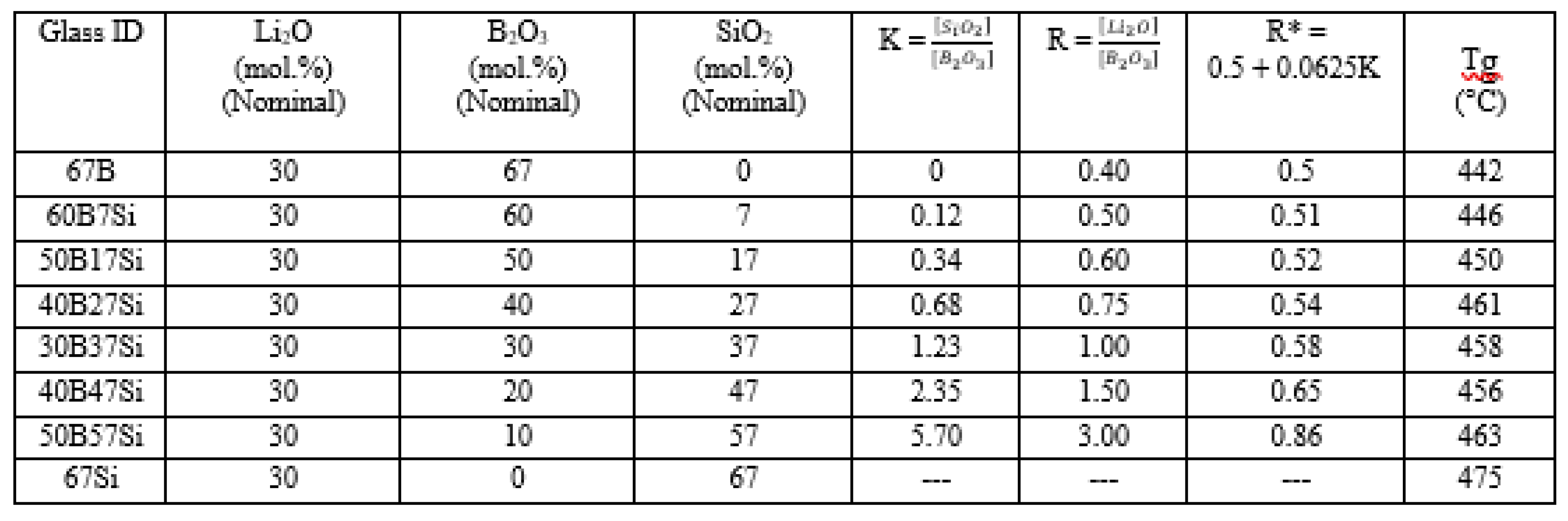

4.1. Glass Transition Temperature (Tg)

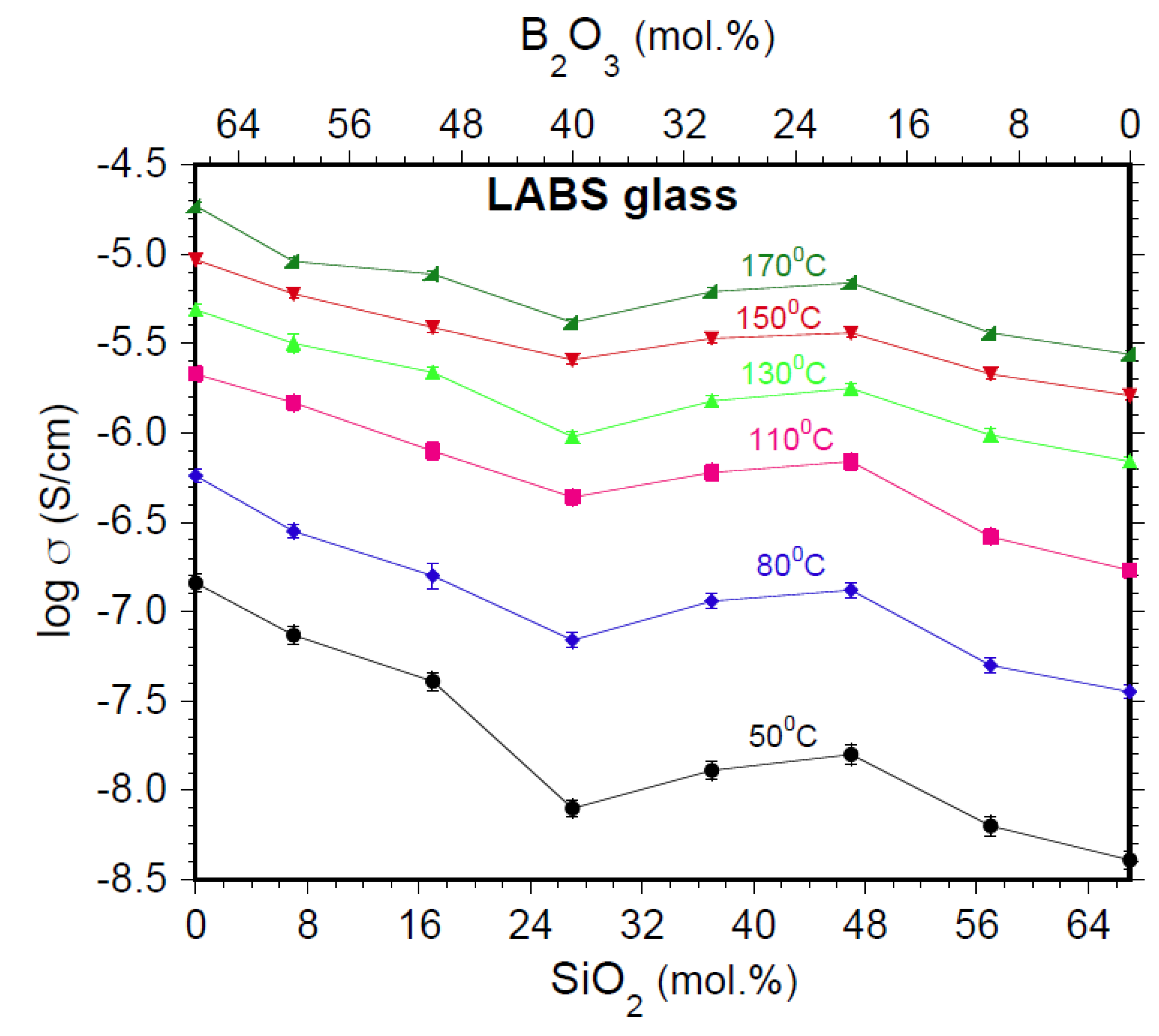

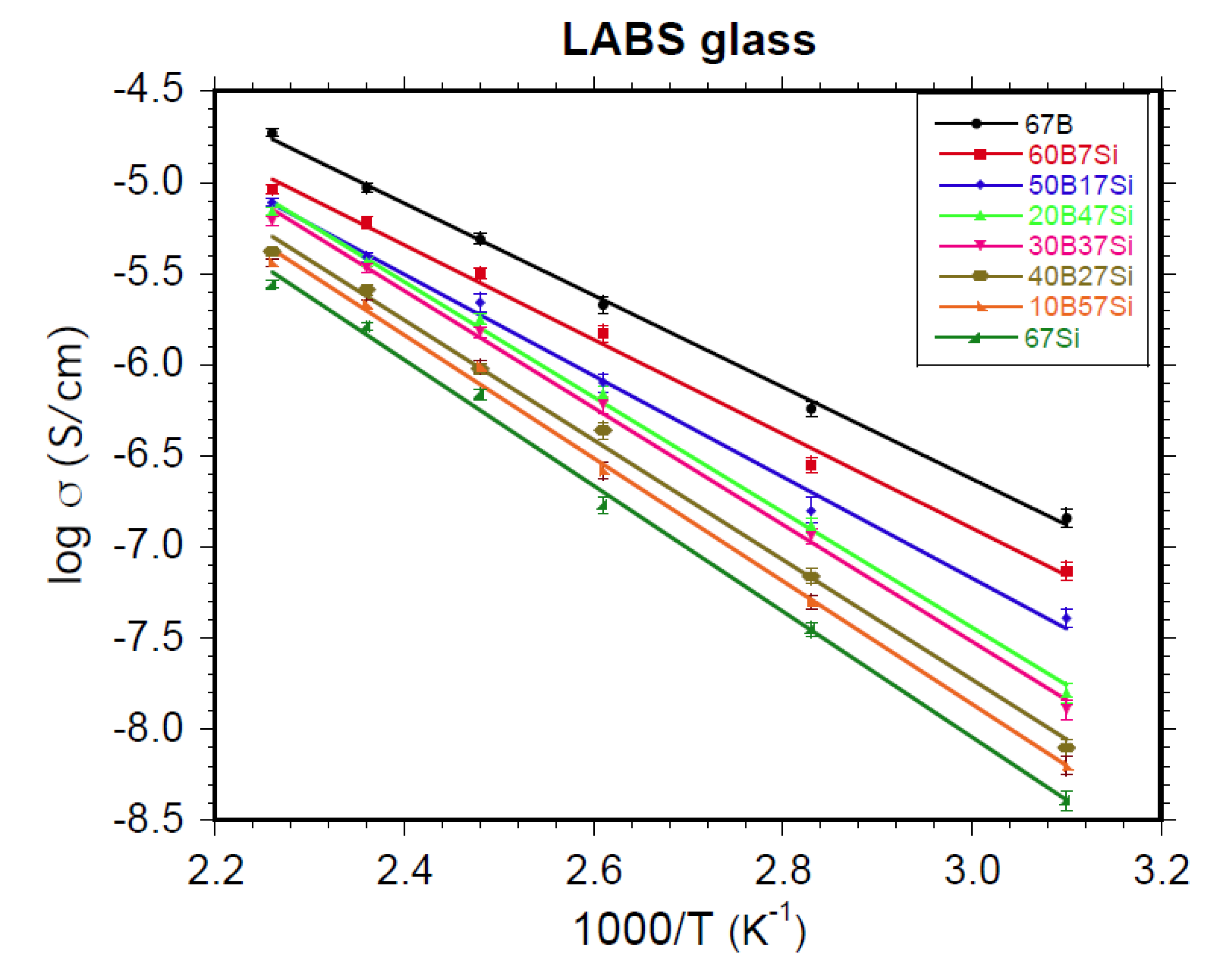

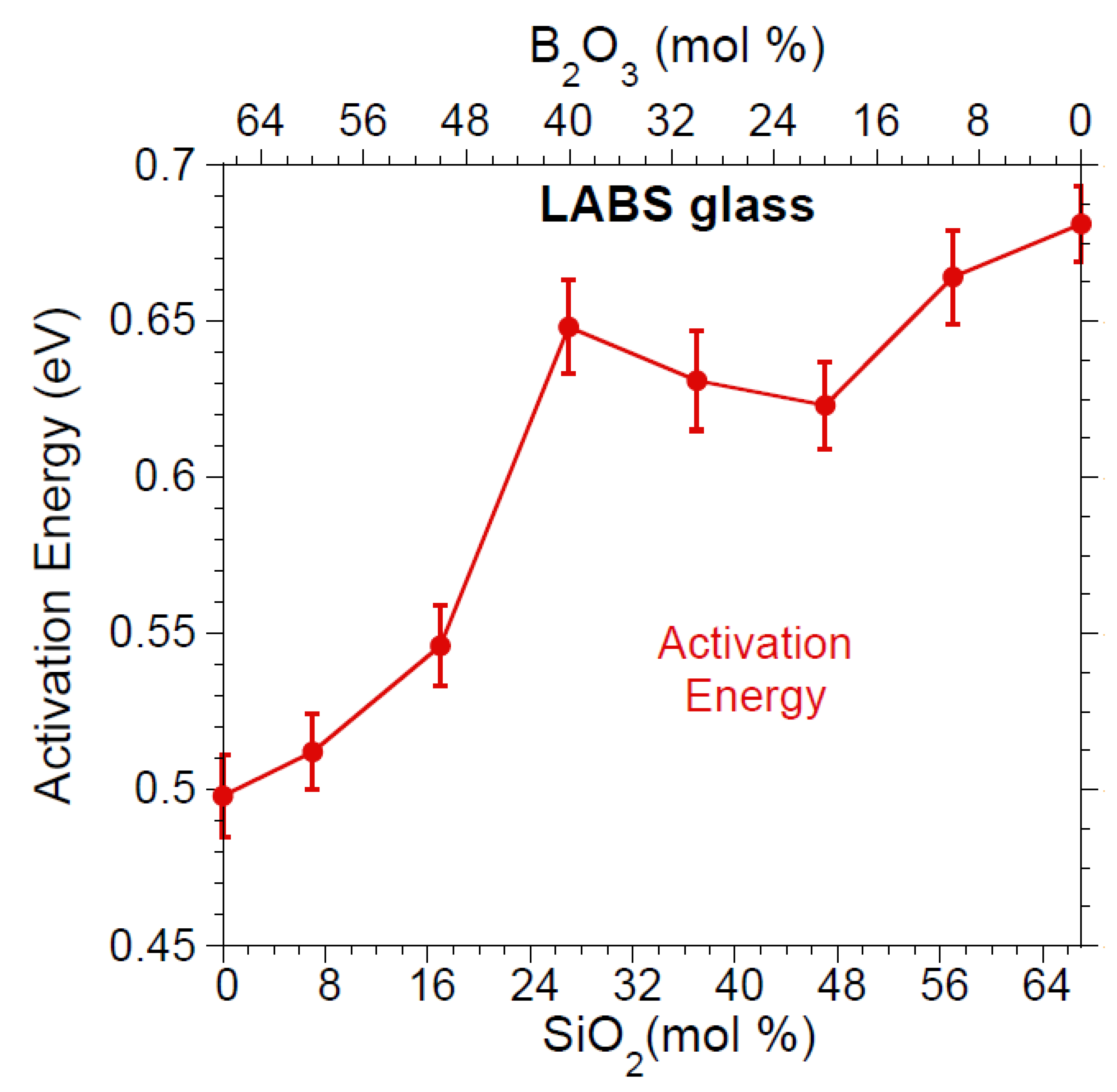

4.2. Electrical Conductivity (σ)

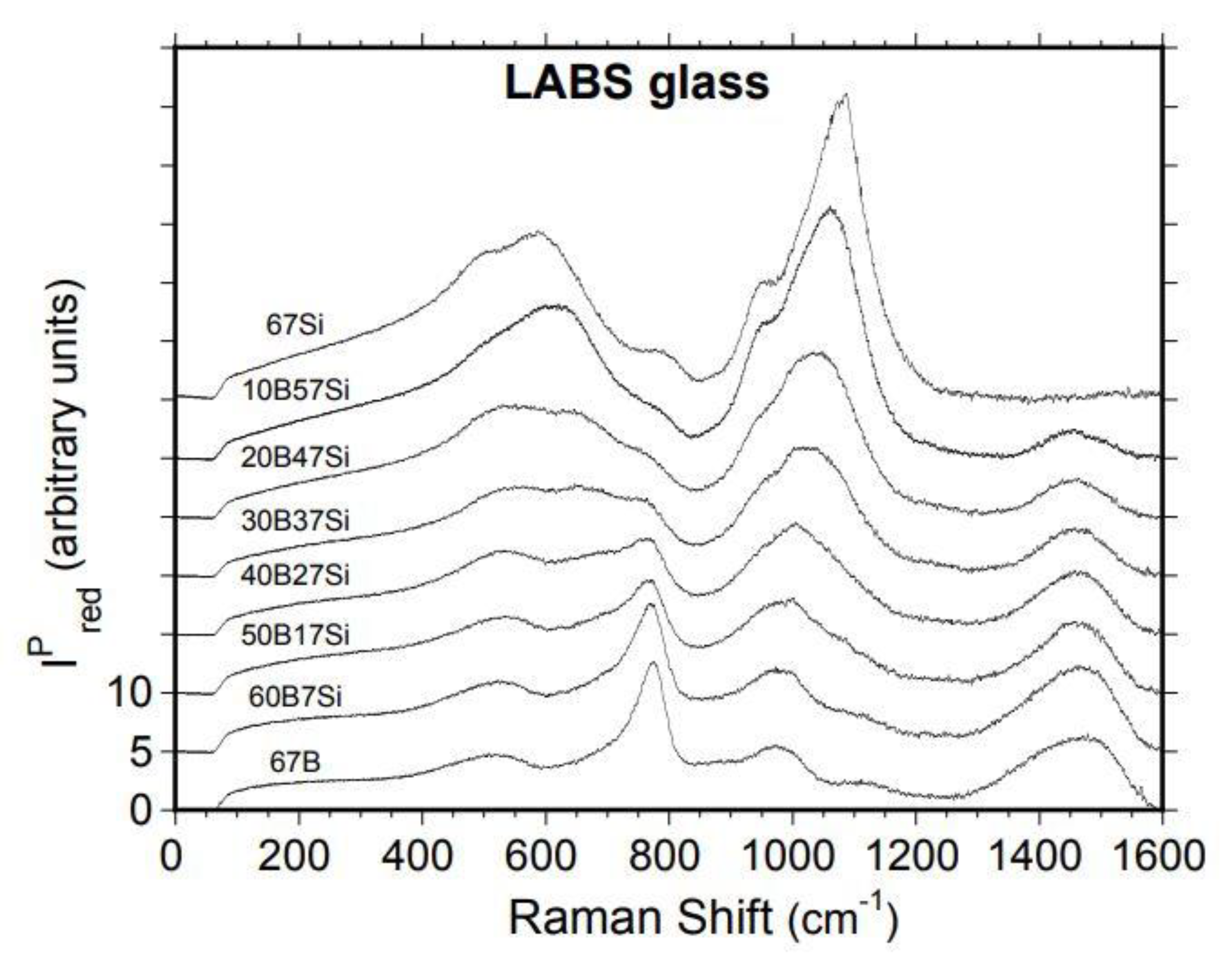

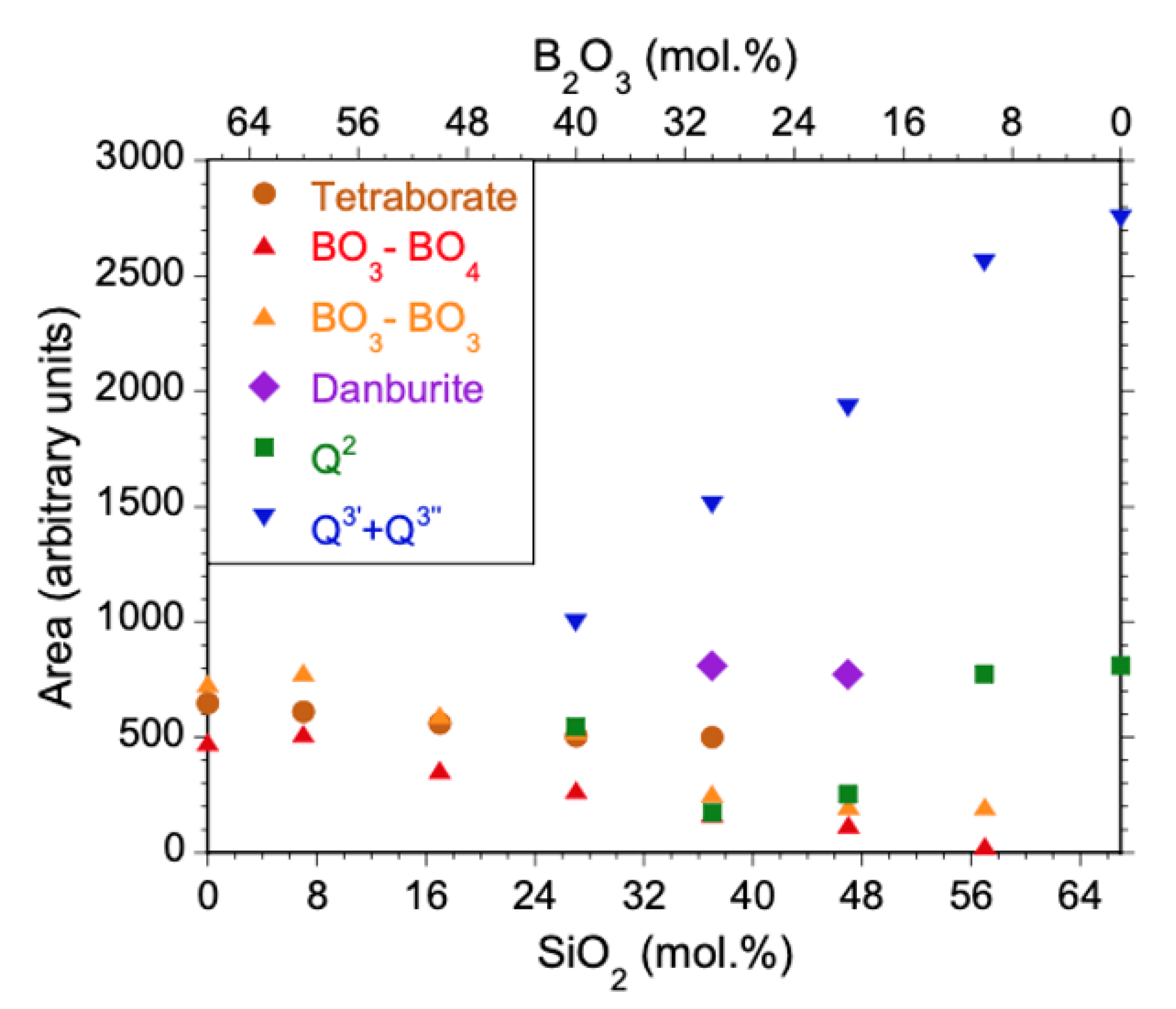

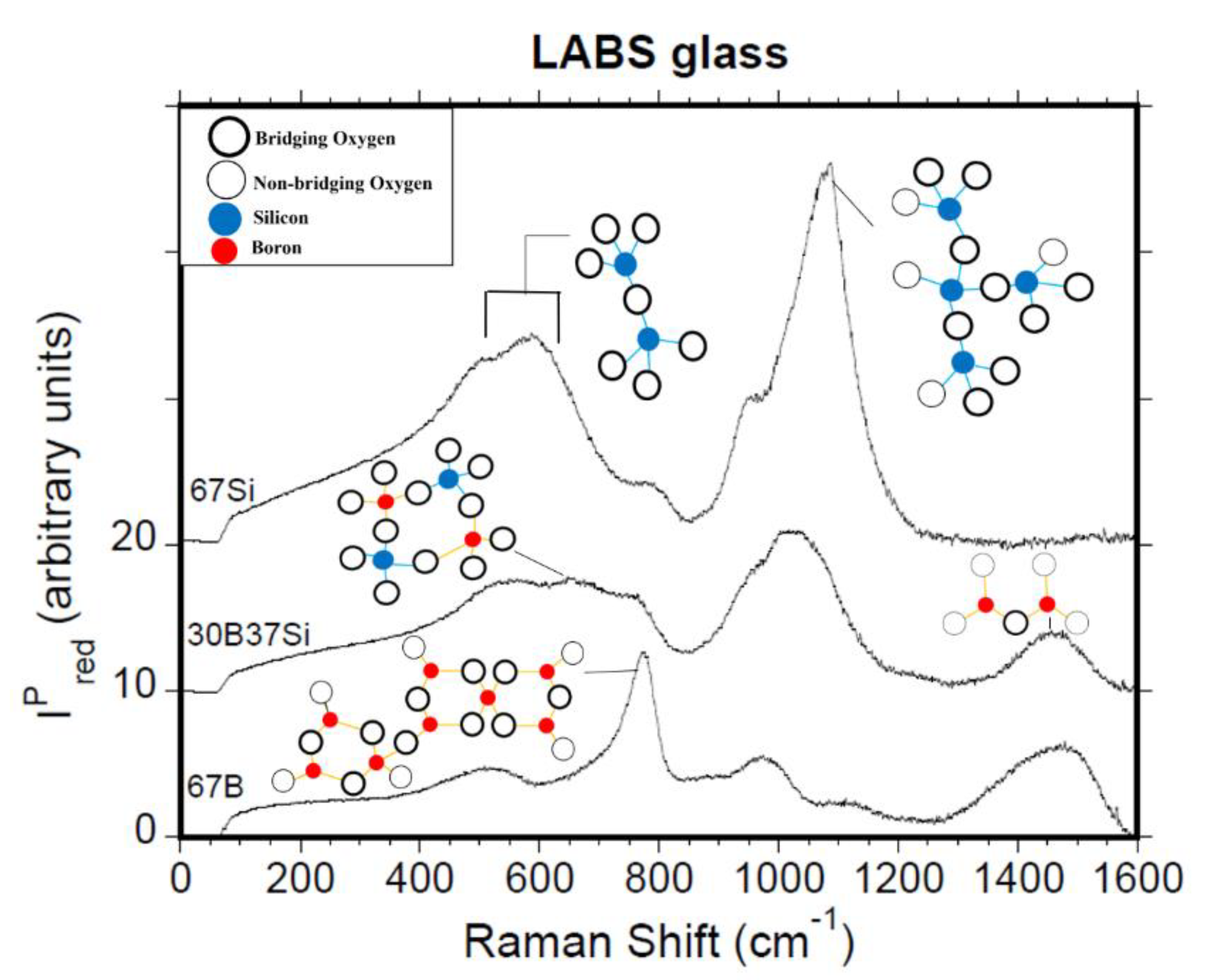

4.3. Raman Spectroscopy

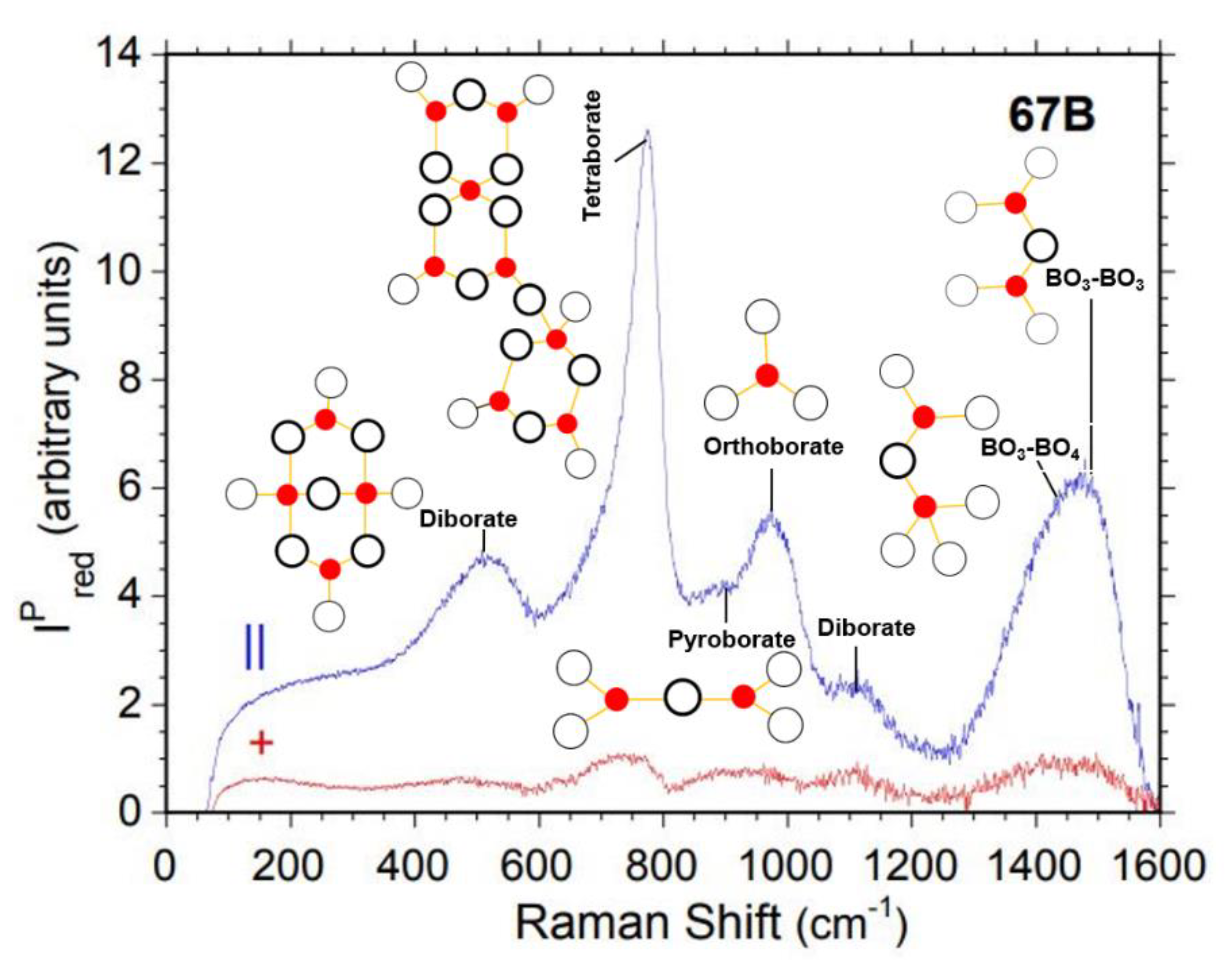

4.3.1. Borate Dominated 67B, 60B7Si, and 50B17Si Glasses

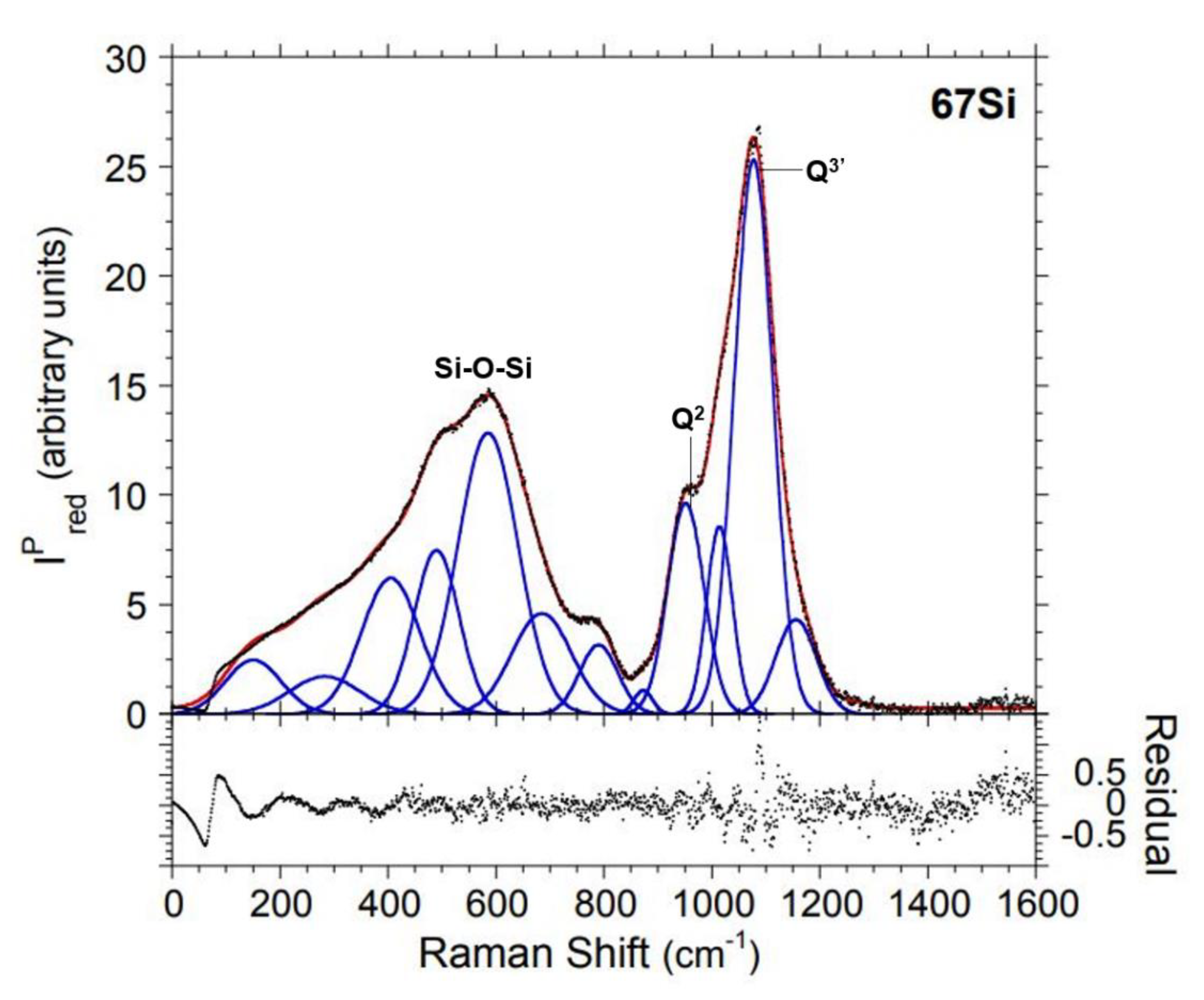

4.3.3. Silicate Dominated 20B47Si, 10B57Si, and 67Si Glasses

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Z. A. Gardy, C. J. Wilkinson, C. A. Randall, and J. C. Mauro, “Emerging Role of Non-crystalline Electrolytes in Solid-State Battery Research”, Front. Energy Res., Sec. Electrochemical Energy Storage, 2020, vol. 8.

- A. Chandra, A. Bhatt, and A. Chandra, “Ion Conduction in Superionic Glassy Electrolytes: An Overview,” J Mater Sci Technol, Mar. 2013, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 193–208. [CrossRef]

- A. Pradel, and M. Ribes, “Ionic conductive glasses”, Materials Science and Engineering: B, 1989, vol. 3, pp. 45-56.

- Magistris, G. Chiodelli, and M. Duclot, “Silver boro-phosphate glasses: Ion transport, thermal stability and electrochemical behavior”, Solid State Ionics, 1983, vol. 9 – 10, pp. 611-615.

- S. A. Shuhaimi, R. Hisam, and A. K. Yahya, “Effects of mixed glass former on AC conductivity and dielectric properties of 70[xTeO2+(1-x) B2O3] +15Na2O+15K2O glass system,” Solid State Sci, 2020, vol. 107. [CrossRef]

- R. V. Salodkar, V. K. Deshpande, and K. Singh, “Enhancement of the ionic conductivity of lithium boro-phosphate glass: a mixed glass former approach,” J Power Sources, 1989, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 257–263. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumar, P. Vinatier, A. Levasseur, and K.J. Rao, “Investigations of structure and transport in lithium and silver borophosphate glasses”, Journal of Solid-State Chemistry, 2004, vol. 177, pp. 1723–1737.

- A. Shaw and, A. Ghosh, “Dynamics of lithium ions in borotellurite mixed former glasses: Correlation between the characteristic length scales of mobile ions and glass network structural units,” Journal of Chemical Physics, 2014, vol. 141. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Lee, K.H. Joo, J. H. Kim, S. G. Woo, H. J. Sohn, T. Kang, Y. Park, and J. Y. Oh, “Characterizations of a new lithium ion conducting Li2O–SeO2–B2O3 glass electrolyte,” Solid State Ion, 2002, vol. 149, pp. 59–65, 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Gundale, V. V. Behare, and A. V. Deshpande, “Study of electrical conductivity of Li2O-B2O3-SiO2-Li2SO4 glasses and glass-ceramics,” Solid State Ion, 2016, vol. 298, pp. 57–62. Solid State Ion. [CrossRef]

- L. F. Maia and A. C. M. Rodrigues, “Electrical conductivity and relaxation frequency of lithium borosilicate glasses,” Solid State Ion, 2004, vol. 168, no. 1–2, pp. 87–92. [CrossRef]

- K. Otto, “Electrical conductivity of SiO2-B2O3 glasses containing lithium or sodium,” Phys Chem Glasses, 1966, vol. 7, pp. 29–33.

- R. H. Doremus, Glass Science, Wiley, 1994.

- P. F. McMillan, “Structural studies of silicate glasses and melts: Applications and limitations of Raman spectroscopy”, American Mineralogist, 1984, vol.69, pp.622-644.

- R. E. Hummel, “Electrical Properties of Polymers, Ceramics, Dielectrics, and Amorphous Materials.” Electronic Properties of Materials: 2011, pp. 181–211, Springer, New York.

- S. J. Edward, “Optimization of fast ionic conducting glasses for lithium batteries “, Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 3046, 2005. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/3046.

- O. L. Anderson and D. A. Stuart, “Calculation of Activation Energy of Ionic Conductivity in Silica Glasses by Classical Methods”, Journal of American Ceramics Society, 1954, vol 37 (12), pp 553-582.

- A. A. Ramadan, R. D. Gould, and A. Ashour, “On the Van Der Pauw method of resistivity measurements.” Thin Solid Films, 1994, vol. 239 (2), pp. 272-275.

- A. Bunde, K. Funke, M. D. Ingram, “Ionic glasses: History and challenges.” Solid State Ionics, 1998, vol. 105(1), pp. 1-13.

- V. Montouillout, H. Fan, L. Campo, and S. Ory, “Ionic conductivity of lithium borate glasses and local structure probed by high-resolution solid-sate NMR,” Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 2018, vol. 484, pp. 57–64. [CrossRef]

- P. Kluvanek, R. Klement, and M. Karacon, “Investigation of the conductivity of the lithium borosilicate glass system”, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 2007, vol. 353, pp. 2004-2007.

- J. Ketter, Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy: Basics of EIS, Gamry Instruments, 2022.

- M. Neyret, M. Lenoir, A. Grandjean, N. Massoni, B. Penelon, and M. Malki, “Ionic transport of alkali in borosilicate glass. Role of alkali nature on glass structure and on ionic conductivity at the glassy state”, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 2015, vol. 410 (15), pp. 74 - 81.

- A. C. Wright, G. Dalba, F. Rocca, and N. M. Vedishcheva, Borate versus silicate glasses why are they so different, Physics and Chemistry of Glasses - European Journal of Glass Science and Technology, 2010, Part B, Volume 51, Number 5.

- M. Kodama, and S. Kojima, “Anharmonicity and fragility in lithium borate glasses.”, Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2002, vol. 69, pp. 961-970.

- I. Avramov, Ts. Vassilev, and I. Penkov, “The glass transition temperature of silicate and borate glasses.”, Journal of Non-crystalline Solids, 2005, vol. 351, pp. 472- 476.

- R. Boekenhauer, H. Zhang, S. Feller, D. Bain, S. Kambeyanda, K. Budhwani, P. Pandikuthira, F. Alamgir, A. M. Peters, S. Messer, and K. L. Loh, “The glass transition temperature of lithium borosilicate glasses related to atomic arrangements.” Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 1994, vol. 175, pp. 137-144.

- Y. H. Yun, and P. J. Bray, “Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the glasses in the system Na2O-B2O3-SiO2”, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 1978, vol. 27 (3), pp. 363 – 380.

- Y. H. Yun, S. A. Feller, and P. J. Bray, “Correction and addendum to Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies of the Glasses in the System Na 2O-B 2O 3-SiO 2”, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 1979, vol. 33 (2), pp. 273-277.

- W. J. Dell, P. J. Bray, and S. Z. Xiao, “11B NMR studies and structural modeling of Na2O-B2O3-SiO2 glasses of high soda content”, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 1983, vol. 58(1), pp. 1-16.

- B. N. Meera, and J. Ramakrishna, “Raman spectral studies of borate glasses”, Journal of Non-crystalline Solids, 1993, vol. 159 pp.1 – 21.

- W. L. Konijnendijk, and J. M. Stevels, “The Structure of Borate Glasses Studied by Raman Scattering”, Journal of Non-crystalline Solids, 1975, vol. 18, pp. 307 – 331.

- W. L. Konijnendijk, and J. M. Stevels, “The Structure of Borosilicate Glasses Studied by Raman Scattering”, Journal of Non-crystalline Solids, 1976, vol. 20, pp. 193 – 224.

- E. I. Kamitsos, and G. D. Chryssikos, “Borate glass structure by Raman and infrared spectroscopies”, Journal of Molecular Structure, 1991, vol. 247, pp. 1 – 16.

- E. I. Kamitsos, M. A. Karakassides, and G. D. Chryssikos, “Structure of borate glasses: Pt. 1”, Physics and Chemistry of Glasses, 1989, vol. 30 (6), pp. 229 – 234.

- A. Winterstein-Beckmann, D. Möncke, D. Palles, E.I. Kamitsos, and L. Wondraczek, “A Raman-spectroscopic study of indentation-induced structural changes in technical alkali-borosilicate glasses with varying silicate network connectivity”, J Non Cryst Solids, 2014, vol. 405, pp. 196–206. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Krogh-Moe, “The Crystal Structure of Lithium Diborate, Li2O.2B2O3”, Acta Cryst., 1962, vol. 15, pp. 190 – 193.

- R. L. Mozzi, and B. E. Warren, “The structure of vitreous boron”, Journal of Applied Crystallography, 1970, vol. 3, pp. 251 – 257.

- 39. T. W. Bril, “Raman spectroscopy of crystalline and vitreous borates. [. Ph.D. Thesis, 1 (Research TU/e / Graduation TU/e), ” Chemical Engineering and Chemistry, Technische Hogeschool Eindhoven, 1976. [CrossRef]

- E. I. Kamitsos, A. Karakassides, and G. D. Chryssikost, “Vibrational Spectra of Magnesium-Sodium-Borate Glasses. 2. Raman and Mid-Infrared Investigation of the Network Structure”, Journal of Phys. Chem., 1987, vol. 91, pp. 11073 – 1079. [Online]. Available: https://pubs.acs.org/sharingguidelines.

- M. Martizez-Ripoll, S. Martinez-Carrera, and S. Garcia-Blanco, “The Crystal Structure of Zinc Diborate ZnB4O7”, Acta Cryst., 1971, vol. B27, pp.672-577.

- E. I. Kamitsos, and A. Karakassides, “Structural Studies of Binary and Pseudo Binary Sodium Borate Glasses of High Sodium Content”, Physics and Chemistry of Glasses, 1989, vol. 30 (1), pp. 19 – 26.

- R. Akagi, N. Ohtori, and N. Umesaki, “Raman spectra of K2O–B2O3 glasses and melts”, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 2001, vol. 295, pp. 471–476.

- B. P. Dwivedi, M. H. Rahman, Y. Kumar, and B. N. Khanna, “Raman Scattering Study of Lithium Borate Glasses”, J. Phys. Chem. Solids, 1993, vol. 54 (5), pp. 621 – 628.

- D. Manara, A. Grandjean, and D. R. Neuville, “Advances in understanding the structure of borosilicate glasses: A Raman spectroscopy study”, American Mineralogist, 2009, vol. 94, pp. 777–784. [CrossRef]

- T. Yano, T. Kobayashi, S. Shibata, and M. Yamane, “High temperature Raman spectra of R2O-B2O3 glass melts”, Physics and Chemistry of Glasses, 2002, vol. 43C, pp. 90–95.

- T. Furukawa, and W. B. White, “Raman spectroscopic investigation of sodium-boro silicate glass structure”, Journal of materials Science, 1981, vol. 16, pp 2689-2700.

- T. Furukawa, K. E. Fox and W. B. White, “Raman spectroscopic investigation of the structure of silicate glasses. III. Raman intensities and structural units in sodium silicate glasses,” Journal of Chemical Physics, 1998, vol. 75, pp. 3226–3237.

- D. A. McKeown, A. C. Nobles, M. I. Bell, “Vibrational analysis of wadeite K2ZrSi 3O9 and comparisons with benitoite BaTiSi3O9”, Physical Review B, 1996, vol. 54, pp. 291.

- D. A. McKeown, F. L. Galeener, and G. E. Brown, “Raman Studies of AI Coordination in Silica-Rich Sodium Aluminosilicate Glasses and some Related Minerals,” Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 1984, vol. 68, pp. 361.

- D.A. McKeown, A. C. Buechele, C. Viragh, and I. L. Pegg, “Raman and X-ray absorption spectroscopic studies of hydrothermally altered alkali-borosilicate nuclear waste glass”, Journal of Nuclear Materials, 2010, vol. 399, pp. 13–25.

- T. Seuthe, M. Grehn, A. Mermillod-Blondin, J. Bonse, and M. Eberstein, “Compositional dependent response of silica-based glasses to femtosecond laser pulse irradiation, in Laser-Induced Damage”, Optical Materials, SPIE, 2013, pp. 88850M. [CrossRef]

- N. Zotov, H. Keppler, Phys. Chem, Miner., 1998, vol. 25, pp. 259.

- N. Zotov, H. Keppler, Am. Mineral, 1998, vol. 83, pp. 823.

- A. A. Osipov, L. M. Osipova, and V. E. Eremyashev, “Structure of alkali borosilicate glasses and melts according to Raman spectroscopy data”, Glass Physics and Chemistry, 2013, vol. 39, pp. 105–112. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Phillips, G. V. Gibbs, and P. H. Ribbe, “The crystal structure of danburite: A comparison with anorthite, albite, and reedmergnerite”, American Mineralogist, 1974, vol. 59, pp. 79–85.

- G. Johansson, “A Refinement of the Crystal Structure of Danburite”, Acta Cryst., 1959, vol. 12, pp. 522-526.

- B. C. Bunker, D. R. Tallant, R. J. Kirkpatrick, and G. L. Turner, “Multinuclear nuclear magnetic resonance and Raman investigation of sodium borosilicate glass structures”, Physics and Chemistry of Glasses, 1990, vol. 31, pp. 30–41.

- D. Manara, A. Grandjean, D. Neuville, “Structure of borosilicate glasses and melts: A revision of the Yun, Bray and Dell model”, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids., 2009, vol. 355, pp. 2528-2531.

- A. A. Osipov, and L. M. Osipova, “Structure of lithium borate glasses and melts: investigation by high-temperature Raman spectroscopy”, European Journal of Glass Science and Technology, 2009, vol. 50, pp. 343–354.

- W. E. S. Turner, and F. Winks, J. Soc. Glass Tech., 1926, vol. 10, pp. 102.

- J. W. Cahn, Acta. Mate., 1961, vol. 9, pp. 745.

- Van der Pauw, L.J. , “A method of measuring the resistivity and Hall coefficient on lamellae of arbitrary shape”, Philips Technical Review, 1958, vol. 20, pp. 220-224.

- P. Umari, and A. Pasquarello, “First-principles analysis of the Raman spectrum of vitreous silica: comparison with the vibrational density of states”, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter, 2003, vol. 15, S1547.

- Igor Pro Manual, Version 6.3, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.wavemetrics.com/.

- G. D. Chryssikos, J. A. Kapoutsis, A. P. Patsis, and E. I. Kamitsos, “A classification of metaborate crystals based on Raman spectroscopy”, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular Spectroscopy, 1991, vol. 47(8), pp. 1117 – 1126.

- W. L. Konijnendijk, “The structure of borosilicate glasses”, 1975, [Phd Thesis 1 (Research TU/e / Graduation TU/e), Chemical Engineering and Chemistry]. Technische Hogeschool Eindhoven. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Osipov, and L. M. Osipova, “Structural studies of Na2O B2O3 glasses and melts using high-temperature Raman spectroscopy”, Physical Condens Matter, 2010, vol. 405, pp. 4718–4732. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Osipov, and L. M. Osipova, “Structure of lithium borate glasses and melts: investigation by high-temperature Raman spectroscopy”, European Journal of Glass Science and Technology, 2009, vol. 50, pp. 343–354.

- A. A. Osipov, and L. M. Osipova, “Structure of glasses and melts in the Na2O-B2O3 system from high-temperature Raman spectroscopic data: I. Influence of temperature on the local structure of glasses and melts”, Glass Physics and Chemistry, 2009, vol. 35, pp. 121–131. [CrossRef]

- S. Petrescu, M. Constantinescu, E.M. Anghel, I. Atkinson, M. Olteanu, and M. Zaharescu, “Structural and physico-chemical characterization of some soda lime zinc alumino-silicate glasses”, Journal of Non-crystalline Solids, 2012, vol. 328, pp. 3280-3288.

- N. Umesaki, M. Takahashi, M. Tatsumisago, and T. Minami, “Raman spectroscopic study of alkali silicate glasses and melts”, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 1996, vol. 205, pp. 225-230.

- D. A. McKeown, I. S. Muller, A. C. Buechele, I. L. Pegg, and C. A. Kendziora, “Structural characterization of high-zirconia borosilicate glasses using Raman spectroscopy”, Journal of Non-crystalline Solids, 2000, vol. 262 (1 – 3), pp. 126 – 134.

- B. O. Mysen and J., D. Frantz, “Raman spectroscopy of silicate melts at magmatic temperatures: Na2O-SiO2, K2O-SiO2 and Li2O-SiO2 binary compositions in the temperature range 25-1475 °C,” Chemical Geology, 1992, vol. 96, pp. 321-332. Chemical Geology.

- M. Nascimento, and N. O. Dantas, “Anderson-Stuart model of ionic conductors in Na2O-SiO2 glasses,” Science & Engineering Journal, 2003, vol. 12(1), pp. 07-13.

- M. Tatsumisago, K. Yoneda, N. Machida, and T. Minami, “Ionic conductivity of rapidly quenched glasses with high concentration of lithium ions”, Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, vol. 95, 1987, pp. 857 - 864.

- A. C. Wright, “My borate life: an enigmatic journey”, Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci., 2015, vol. 6, pp. 45-63.

- E. A. Porai-Koshits, V. V. Golubikov, and A. P. Titov, “ The fluctuation structure of vitreous boron oxide and two-component alkali borate glasses.”, Borate Glasses, Structure, Properties, Application, Materials Science Research, 1978, vol. 12, pp. 183-199.

- F. L. Galeener, “Planar rings in glasses”, Soild State Commun., 1982, vol. 44, pp. 1037-1040.

| Vibrational Assignment | 67B | 60B7Si | 50B17Si | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position (cm -1) | peak width | Area | Position (cm -1) | peak width | Area | Position (cm -1) | peak width | Area | |

| Diborate (506 cm -1) [29,39] | 527 | 133 | 575 | 527 | 135 | 746 | 543 | 154 | 994 |

| Ring type metaborate (600-650 cm -1) [29,30,31,32] | 612 | 84 | 148 | 607 | 83 | 142 | 599 | 90 | 0 |

| Chain type metaborate (700-735 cm -1) [29,30,31,32] | 703 | 113 | 646 | 701 | 126 | 890 | 690 | 123 | 790 |

| Tetraborate (740-775 cm -1) [29,38] | 772 | 59 | 649 | 772 | 63 | 612 | 769 | 72 | 561 |

| Pyroborate (820 cm -1) [29,30,31,32,40] | 857 | 89 | 347 | 854 | 91 | 364 | 861 | 105 | 373 |

| Orthoborate (875-1000 cm -1) [29,39,62] | 971 | 127 | 745 | 973 | 133 | 1009 | 981 | 134 | 1127 |

| Diborate (1000-1110 cm -1) [34,52,57] | 1114 | 106 | 254 | 1109 | 110 | 326 | 1098 | 104 | 357 |

| BO3 symmetric stretch (1200 cm -1) [31,35,43] | 1236 | 127 | 168 | 1233 | 125 | 195 | 1233 | 125 | 179 |

| BO3-BO4 (1300-1450 cm -1) [28,29,30,31] | 1381 | 122 | 479 | 1384 | 125 | 517 | 1393 | 125 | 358 |

| BO3-BO3 (1450-1600 cm -1) [28,29,30,31] | 1483 | 117 | 733 | 1480 | 112 | 783 | 1475 | 109 | 597 |

| Vibrational Assignment | 40B27Si | 30B37Si | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position (cm -1) | peak width | Area | Position (cm -1) | peak width | Area | |

| Vibration of bridge bonds B-O-B, B-O-Si, Si-O-Si (500-600 cm -1) [44,45,52] | 543 | 155 | 1072 | 539 | 144 | 980 |

| danburite and reedmergnerite rings [42,52,53] | 681* | 118* | 742* | 664 | 121 | 809 |

| Tetraborate (740-775 cm -1) [29,38] | 765 | 79 | 505 | 764 | 102 | 505 |

| orthosilicate-pyroborate (850 cm -1) [40,67] | 858 | 120 | 380 | 888 | 87 | 241 |

| Q2 (950 cm -1) [46,47,48] | 952 | 93 | 548 | 942 | 59 | 174 |

| Q3’ (1020 cm -1) [46,47,48] | 1014 | 80 | 546 | 1020 | 121 | 1369 |

| Q3’’ (1080 cm -1) [46,47,48,51] | 1079 | 90 | 448 | 1085 | 54 | 138 |

| Q4 (1140 cm -1) [46,47,48] | 1148 | 88 | 117 | 1138 | 68 | 148 |

| Symmetric stretching of BO3 units (1200 cm -1) [31,35,43] | 1234 | 121 | 143 | 1227 | 92 | 50 |

| BO3-BO4 (1300-1450 cm -1) [28,29,30,31] | 1391 | 117 | 273 | 1415 | 77 | 172 |

| BO3-BO3 (1450-1600 cm -1) [28,29,30,31] | 1473 | 107 | 529 | 1478 | 78 | 255 |

| Vibrational Assignment | 20B47Si | 10B57Si | 67Si | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position (cm -1) | peak width | Area | Position (cm -1) | peak width | Area | Position (cm -1) | peak width | Area | |

| breathing vibration in four membered rings (485 cm -1) [45,50] | 531 | 138 | 1119 | 509 | 127 | 855 | 490 | 98 | 781 |

| breathing vibration in three membered rings (600 cm -1) [52,63,65] | 641** | 138** | 772** | 601 | 131 | 1279 | 585 | 131 | 1790 |

| stretching plus bending of Si-O-Si bond (654 cm -1) [44,45] | 690 | 121 | 436 | 673 | 117 | 735 | 685 | 130 | 635 |

| Si-O-Si bending modes (800 cm -1) [47,66] | 777 | 89 | 314 | 774 | 89 | 333 | 790 | 83 | 280 |

| Orthosilicate (850 cm -1) [67] | 891 | 87 | 239 | 881 | 87 | 156 | 873 | 41 | 47 |

| Q2(950 cm -1) [46,47,48,69] | 941 | 59 | 253 | 950 | 76 | 774 | 952 | 79 | 811 |

| Q3’(1020 cm -1) [46,47,48,68] | 1018 | 105 | 1442 | 1016 | 72 | 841 | 1014 | 56 | 513 |

| Q3’’(1080 cm -1) [46,47,48] | 1084 | 70 | 484 | 1076 | 87 | 1715 | 1077 | 83 | 2234 |

| Q4(1140 cm -1) [46,47,48,69] | 1145 | 68 | 176 | 1159 | 68 | 150 | 1156 | 88 | 407 |

| Symmetric stretching of BO3 units (1200 cm -1) [31,35,43] | 1227 | 92 | 68 | 1229 | 92 | 64 | --- | --- | --- |

| BO3-BO4(1300-1450 cm -1) [28,29,30,31] | 1416 | 62 | 121 | 1449 | 87 | 201 | --- | --- | --- |

| BO3-BO3(1450-1600 cm -1) [28,29,30,31] | 1476 | 74 | 202 | 1512 | 45 | 30 | --- | --- | --- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).