1. Introduction

Sporothrix spp. is a thermodimorphic, saprophytic fungus, which can contaminate humans and animals, causing sporotrichosis [

1,

2]. Infection occurs via traumatic inoculation by the bite or scratch of contaminated animals, mostly felines, or through inoculation of the fungus from contaminated organic material, such as soil, thorns, or wood [

3,

4]. It is well known that even healthy house cats can transmit

Sporothrix spp., by scratching due to the habit of burying waste and sharpening their nails in potentially contaminated organic matter [

5,

6].

The most clinically relevant species of the genus

Sporothrix are

S. schenckii,

S. globosa, and

S. brasiliensis [

7,

8]. Among them,

S. brasiliensis is considered the most virulent; and is responsible for the highest number of case reports in Brazil, and represents a zoonotic transmission disease [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The clinical manifestations of sporotrichosis are characterized by the appearance of lesions in the cutaneous or subcutaneous tissues [

4,

12] and are classified as cutaneous-localized, cutaneous-lymphatic, disseminated, and extracutaneous forms [

13,

14,

15]. The clinical form of sporotrichosis and severity of the symptoms are directly related to the individual’s immune status, microbial load, depth of the affected tissue, and virulence factors of the inoculated strain [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

This study aimed to collect, identify, and characterize clinical isolates of Sporothrix spp., from humans and cats, from the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. The virulence factors, such as melanization capacity, thermotolerance, urease production, and biofilm formation were evaluated among these isolates of Sporothrix spp. Also, the susceptibility to itraconazole and amphotericin B, which are the main antifungals used in the treatment of sporotrichosis, were evaluated among these isolates. Finally, the results between human and felines isolates were compared to assess whether there are any differences between these isolates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

This research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte Hospital, Minas Gerais, Brazil, under CAAE no 55549216.2.0000.5138, and by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil, under CEUA no 189/2021.

2.2. Sporothrix Strains

To compose the group of human isolates, twenty-seven Sporothrix spp. strains were obtained from patients with sporotrichosis, treated at the Santa Casa Hospital of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. To compose the group of feline isolates, twenty-one Sporothrix strains were isolated from domestic cats with sporotrichosis, attended in veterinary clinics of the Ribeirão das Neves city, which belongs to the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. Additionally, a control S. schenckii strain (ATCC 32286) was also included in this study.

2.3. Macro and Micro-Morphological Identification

For macro-morphological identification, clinical samples (swab, lesion scraping, or biopsy) were cultured at 27°C in a Sabouraud Agar culture medium containing 0.05% chloramphenicol, for 7 to 20 days. Colony morphology of all the isolates was studied on PDA at 27°C. For the transition of mycelial to yeast phase, the cultures were inoculated on to brain heart infusion agar incubated at 35 °C for up to 21 days. Macroscopic identification was performed according to the morphological characteristics of the culture. Microculture slides were prepared using the Hidell method from isolated cultures for microscopic identification [

19]. After 21 days of growth, the slides were stained with Lactophenol dye (Methyl blue, phenol crystals and lactic acid) and then microscopically identified according to their conidiation type [

19].

2.4. Molecular Identification

DNA was extracted from the cultures through the following steps: Cell lysis, using a buffer of Tris-HCl (0.5M), EDTA (0.005M), NaCl (0.1M), and SDS (1%); protein precipitation using chloroform isoamyl alcohol (24:1); DNA precipitation using sodium acetate (3M) and DNA hydration using Tris-EDTA buffer (0.001 M). The extracted DNA was subjected to the PCR reaction, using specific primers to Sporothrix genus: Forward (5′-TCACAACTCCCAACCCTTGC-3′) and Reverse (5′-GGGAGAACATGCGTTCGGTA-3′), developed by Fernandes and collaborators [

20]. The following volumes were used for the PCR reactions: 0.3µL of H2O; 1.0 µL of Buffer (10x); 0.5µL of Primer Forward (10 mM); 0.5µL of Primer Reverse (10 mM); 0.3µL Mgcl2 (50 mM); 0.2µL dNTP (10 mM); 0.2µL Taq (1U) and 1.0µL DNA. The temperature standard used in the run was: Denaturation 95ºC/30 seconds, annealing 60ºC/30sec, extension 72ºC/30sec and, 40 cycles were performed. After confirmation of the genus in the first PCR reaction, another PCR reaction was performed using specific primers to the calmodulin’ gene [

21] followed by the sequencing to species identification. The following volumes were used for this PCR reaction: 0.3µL of H2O, 1.0µL of Buffer (10x), 0.5µL of Primer Forward (10 mM), 0.5µL of Primer Reverse (10 mM), 0.3µL Mgcl2 (50 mM), 0.2µL dNTP (10 mM), 0.2µL Taq (1U) and 1.0µL DNA. The temperature standard used in the run was: denaturation 95ºC/30sec, annealing 60ºC/30sec, extension 72ºC/30 sec. Forty cycles were performed. All 1% agarose gel electrophorese procedures were conducted at 220W for 20 minutes. The amplicon obtained through the PCR reaction was sequenced using specific kits for sequencing and the obtained results were deposited in Gene Bank and analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) software (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast).

2.5. Antifungal Susceptibility

A plate microdilution test was performed, based on the methodology described by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [

22]. The antifungals investigated were itraconazole in the interval range from 16 to 0.03 µg/mL and amphotericin B in the interval range from 8 to 0.015 µg/mL. For the experiments, the antifungals were diluted in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). The culture medium used in the experiment was RPMI plus 0.165 mol/L MOPS (3-[N-morpholino] propanesulfonic acid). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Brazil, and used without further purification. The isolates were previously cultured for seven days at 37°C on potato and dextrose agar (PDA) (Himedia, India). Approximately 5 mL of saline solution (85%) were added to the plate containing the isolate, gently homogenizing the solution over the isolate so that some fungal cells were detached. The saline solution containing the cells was transferred to a sterile test tube, and the inoculum was then standardized at 530 nm using a Shimadzu UV VIS spectrophotometer, Model UV 1800, and read between 80 to 82% transmittance. The inhibition of

Sporothrix sp. growth was considered for the well that presented 80% growth inhibition caused by itraconazole, and 100% inhibition induced by amphotericin B.

2.6. Fungi Thermotolerance

The Sporothrix isolates were cultured in BHI broth (Sigma-AldrichBrazil) for seven days at 37°C and under constant agitation using a mechanical shaker. After growth, the yeasts were centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 5 minutes and washed in 0.9% saline. Then, a fungal suspension in saline of 1x10⁶ cells/mL was prepared in a Neubauer chamber. Ten microliters of fungal cell suspension were inoculated into Petri dishes containing Sabouraud Dextrose Agar and incubated at 27, 37, 41, and at 50 °C for seven days. The results were visually evaluated, analyzing the degree of yeast growth, and classified as follows: (-) no growth, (+) low growth, (++) moderate growth and (+++) high growth. The conditions and parameters of this experiment were standardized by our laboratory.

2.7. Melanin Production

The conditions and parameters of this experiment were standardized by our laboratory. In this way, ten microliters of the Sporothrix´ cell suspension were inoculated into Petri dishes containing Sabouraud Dextrose Agar and incubated at 27°C for 14 days. The evaluation of the results was performed visually, analyzing the degree of darkening of the isolate and classified as follows: (-) no melanin production, (+) low melanin production, (++) moderate melanin production, (+++) high melanin production.

2.8. Urease Production

The conditions and parameters of this experiment were standardized by our laboratory. For this assay, 100 µL of the yeast suspension were inoculated into 1 mL of Christensen’s urea broth (BD, USA) and incubated at 37 °C, for 14 days. The results were visually evaluated, based on the intensity of the pink color generated in the medium, that is directly proportional to the amount of urease produced by each isolate, and classified as follows: (-) no urease production, (+) low urease production, (++) moderate urease production, (+++) high urease production.

2.9. Biofilm Formation

The

Sporothrix´ isolates were cultured in BHI broth for seven days at 37 °C, with constant shaking at 100 rpm. The yeasts were centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 5 minutes and washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) [137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.76 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4]. A

Sporothrix´ cell suspension in PBS was adjusted to 1x10⁷ cells/mL in a Neubauer chamber. In 96-well microplates, 100 μL of the fungal suspension was added in RPMI and incubated at 37 °C in a shaker at 75 rpm for 90 minutes, during which the initial cell adhesion stage occurs. After this period, the supernatant was removed, and each well was washed twice with 200 μL of PBS solution. Then, 200 μL of RPMI (Sigma-Aldrich, Brazil) were added to the wells, and the plate was incubated under agitation at 37 °C for 48h; the culture medium was changed every 24h. To evaluate the total biofilm biomass, Crystal Violet was used, which stains viable and non-viable cells and the matrix, based on the methodology described by Pierce et al., 2008 [

23].

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data evaluation was performed using the software Excel (2015) and Stata-SE, version 17.0. To present the results, tables and/or graphs were created. For quantitative variables, measures of central tendency and dispersion were obtained. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages related to each category were calculated. Quantitative variables were assessed for Normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Variables with Normal distribution were compared by Student’s t-test, and for those not Normal, the Mann-Whitney test was used. For categorical variables, in which were evaluated the difference between proportions, the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test or Monte Carlo Simulation were used, each one following the assumptions necessary for its use. In all statistical tests, a significance level of 5% was considered, thus those associations whose p-value was less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

2.11. Phylogenetic Tree

Nucleotide-BLAST searches comparing the isolates sequenced in this study with published

Sporothrix calmodulin-related sequences available in NCBI GenBank were performed on BLAST, available from:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21097/.

The sequences were selected and obtained in FASTA format. The sequences were sent to MAFFT version 7 [

24], a multiple sequence alignment software (MSA). The overall confidence score of the MSA was checked with Guidance2 version 2.02 [

25], to improve the quality of chosen samples and identify unreliable alignment regions due to the high uncertainty associated with multiple sequence alignment, the overall score of the MSA was 0.99. Despite the difference in size, no editing was performed. The multiple sequence alignment corresponded to 49 taxa, with 904 sites, 28.66% of gaps, and 67.59% invariant sites. A reference tree was inferred on RAxML-NG version 1.1.0 [

26], a phylogenetic inference software based on Maximum-Likelihood (ML). We conducted a heuristic search for the ML tree to select the best-scoring topology. Following that, a non-parametric bootstrap analysis was performed. The MRE-based bootstrapping test was performed after every 50 replicates, the test was terminated once convergence occurred, bootstrapping converged after 450 replicates. To finalize, we conducted a support check with the trees generated by the heuristic search for the Maximum likelihood of the best-scoring topology and conducted a bootstrap analysis using the Transfer Bootstrap Expectation support metric in RAXML-NG. The phylogenetic tree and annotations were constructed on interactive tree of life, iTol version 6 [

27].

3. Results

3.1. Macro and Micro-Morphological Identification

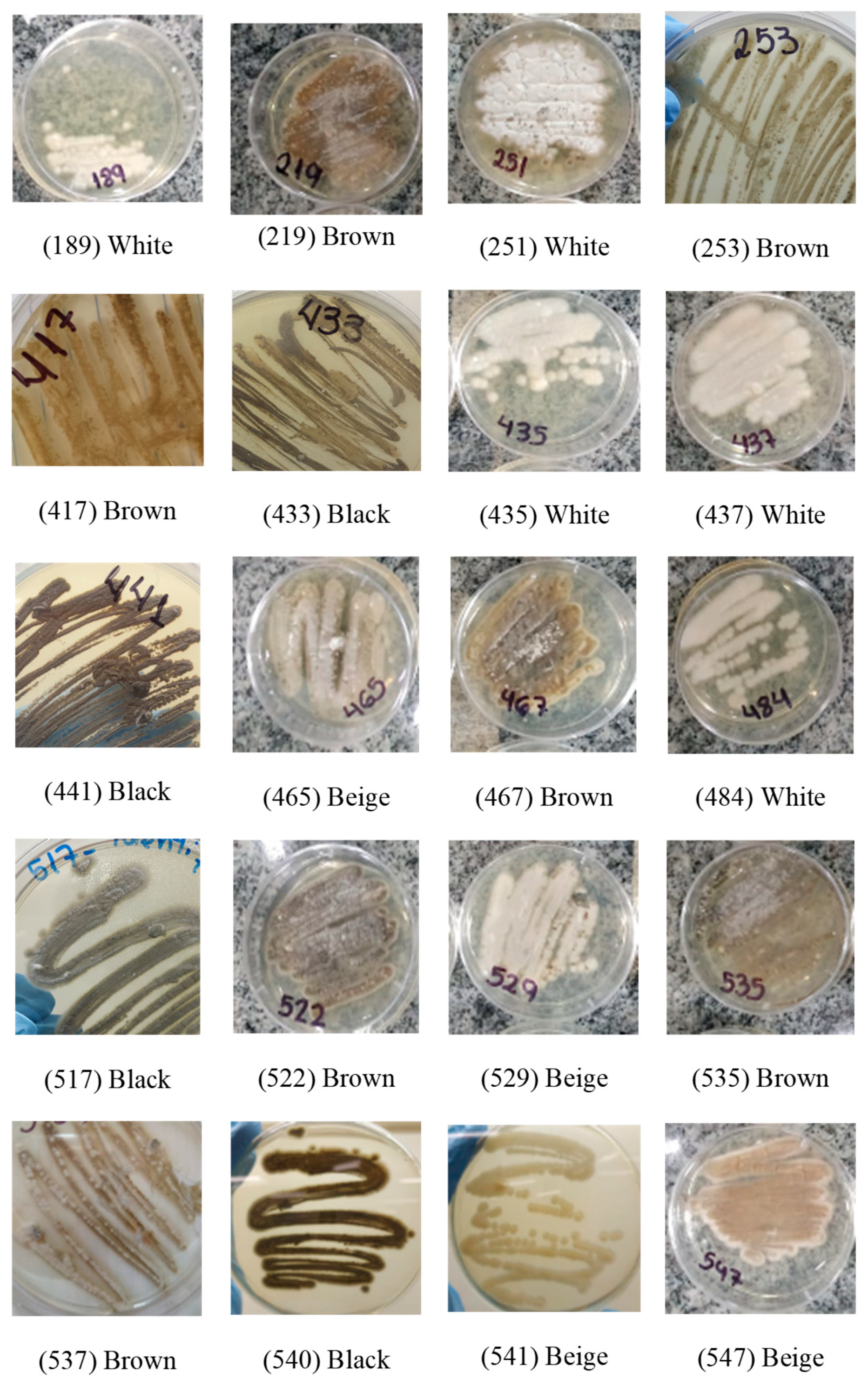

In relation to macro and micro-morphological aspects, all cultures obtained from biological samples were suggestive of Sporothrix sp. with filamentous at 27°C, whitish coloration in the first days of growth, and some cultures turned brown to black at the end of 21 days. It was also observed that all strains showed dimorphism capacity when cultivated at 37° (

Figure 1).

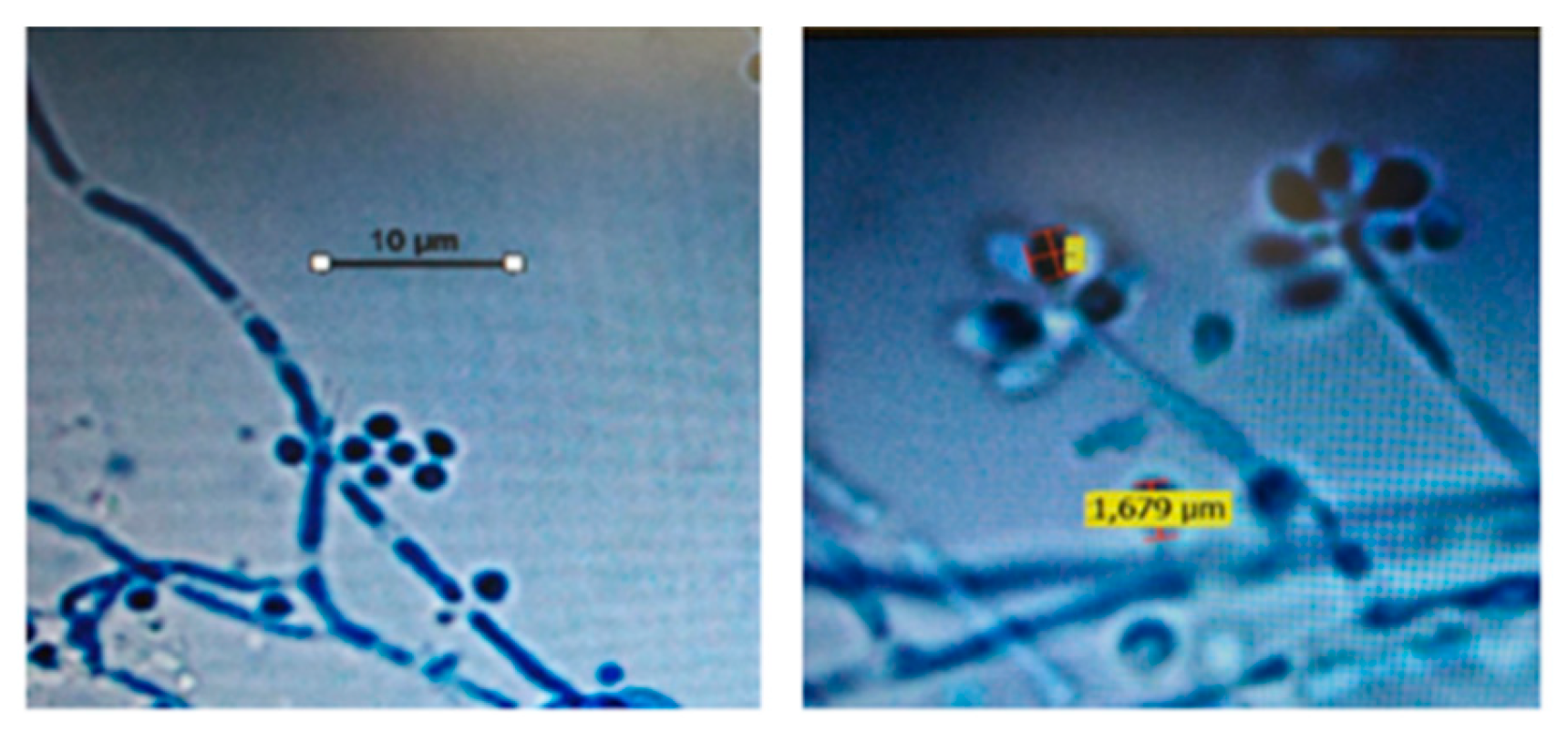

The cultures were also submitted to microscopic analysis after the microculture was performed, and in all isolates, it was possible to observe septate, branched, delicate hyaline hyphae, and conidia arranged in terminal clusters, resembling daisies, characteristic aspects of genus Sporothrix (

Figure 2).

3.2. Molecular Identification

According to the results of the PCR reaction using gender-specific primers, was observed an amplification of a 450 base pair fragment for all isolates, both from humans and F. catus, as well as in the sample of S. schenkii (ATCC 32286) used as positive control. There was no negative control amplification, thus confirming that all isolated samples belong to the genus Sporothrix. After the results of this PCR reaction, fifteen human and nine F. catus isolates were chosen by sampling to be sequenced, using primers from the Calmodulin gene, CL1 and CL2A.

3.3. Antifungal Susceptibility

Regarding the evaluation of susceptibility of amphotericin B against isolates de Sporothrix tested, we observed that for the majority of human isolates (37,04%), the MIC was 0.25 µg/mL. For cat isolates, we observed that the majority (90.48%) were sensitive at a concentration of 1.0 µg/mL of amphotericin B. As for itraconazole, the majority of human isolates (81.48%) and all cat isolates tested were sensitive at a concentration of 0.5 µg/mL. A comparison of MIC values revealed that human isolates were more susceptible to antifungal agents compared to feline isolates. A higher proportion of susceptible human isolates were observed at lower dosages of antifungals, whereas a greater proportion of susceptible feline isolates were observed at higher dosages of antifungals. However, this difference was only statistically significant in the evaluation of amphotericin B (p < 0.05). In the evaluation involving itraconazole, the statistical test did not show significance (p = 0.115;

Table 1).

3.4. Thermotolerance

It was possible to observe high growth (+++) in all isolates, both from humans and feline, at temperature up to 37°C. At a temperature of 41°C, a high growth (+++) of 38.10 % was observed of the felines isolates and no growth was observed for the human isolates. Low growth (+) was observed in 50% of the human isolates versus no low growth (+) in the felines isolates, these results were significant (p<0.05). When growth at 45°C was evaluated, a high growth (+++) was not observed for either human or felines isolates. Nevertheless, it was possible to observe an intermediate growth (++) of 71.43% of the felines isolates and 19.05% of the human isolates. A low growth (+) in 80.95% of human isolates compared to 28.57% of felines isolates, these results were also significant (p<0.05). Surprisingly at 50°C, there was neither high (+++) nor intermediate (++) growth, only low growth (+) for both types of isolates, 11 of 27 (40.7%) in human isolates and 15 of 21 (71.4%) in felines isolates.

3.5. Melanin Production

In this study, it was observed that all isolates, whether from humans or felines, could produce melanin. The human isolates exhibited slightly higher melanin production (37.04% highly melanin-producing) compare to the feline isolates (33.33% highly melanin-producing), although this difference was statistical significance (p=0,651) (

Table 1). Most feline isolates displayed higher melanization levels during the initial days of growth, whereas melanization in the human isolates only was observed only after the fifth day of cultivation.

3.6. Urease Production

It was observed that all isolates from both humans and felines could produce urease. The isolated samples from felines were slightly higher urease producers (52.38% highly urease producers) than samples isolated from humans (44, 44% highly urease-producing). But this comparison was not significant (p=0.765), statistically these proportions were similar (

Table 1).

3.7. Biofilm Production

It was observed that all isolates from humans and cats were capable of producing biofilm. A higher proportion of human isolates (44.4%) exhibited high biofilm production (+++) compared to feline isolates (14.29%); however, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.081) (

Table 1).

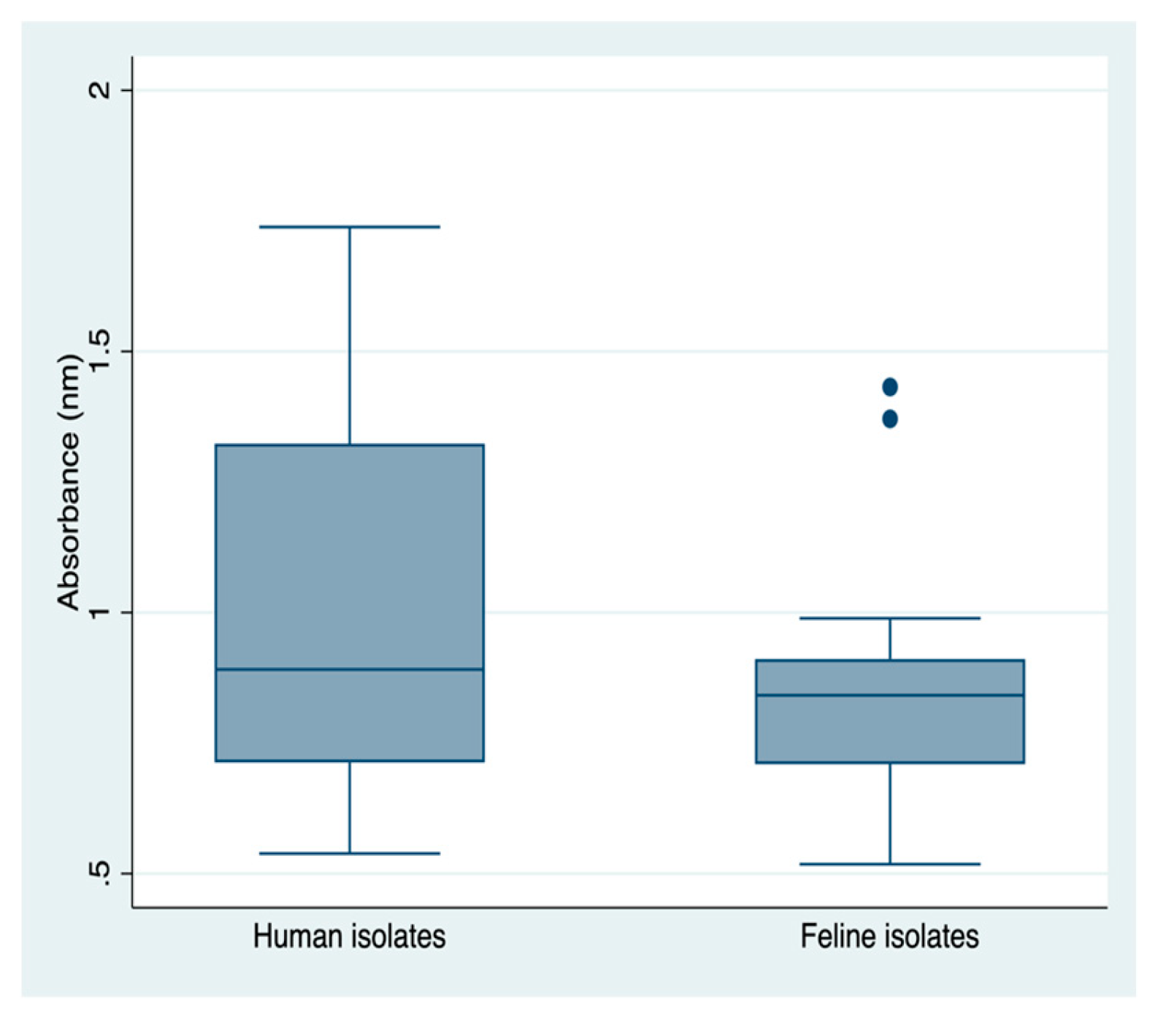

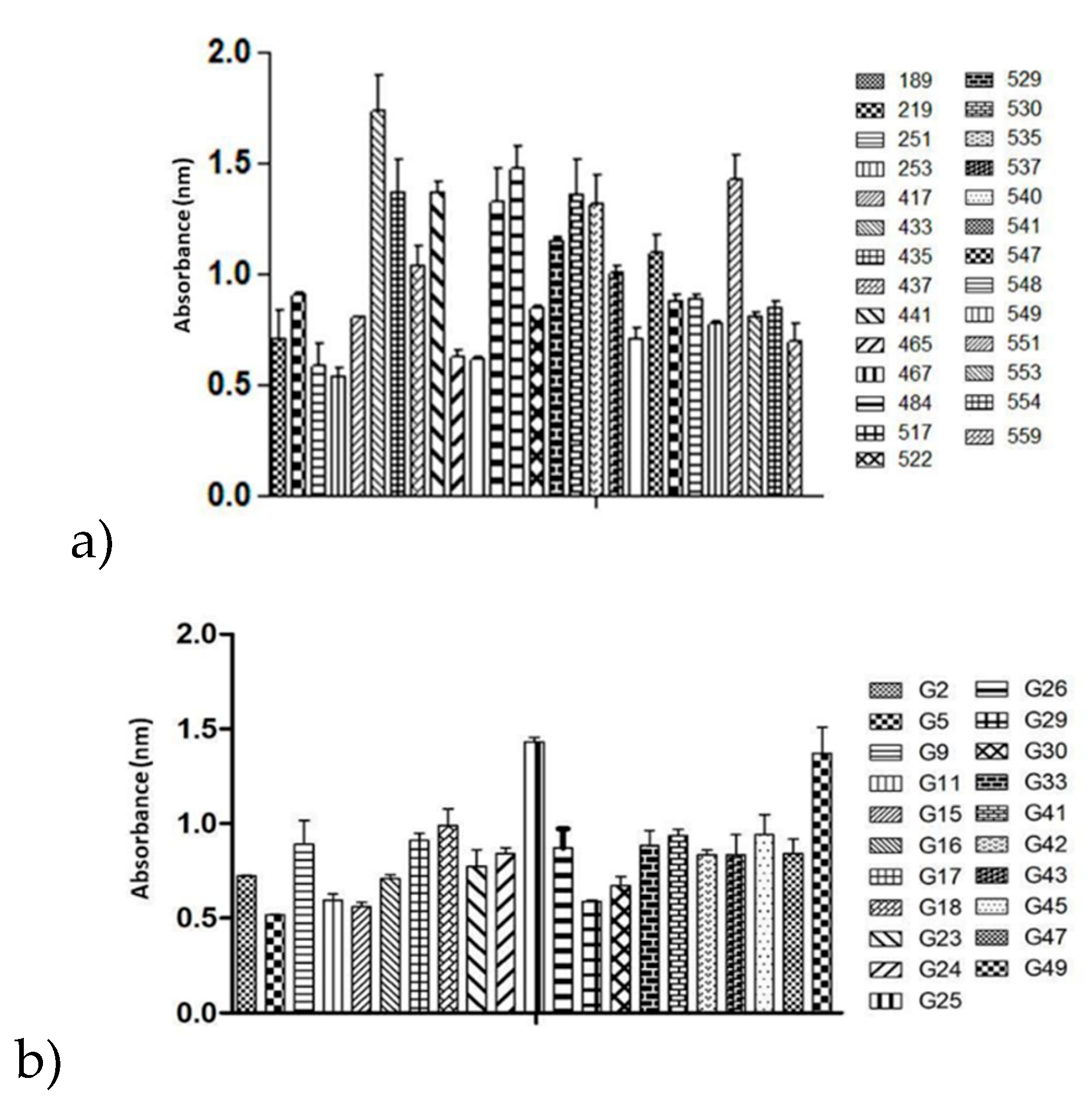

Regarding the analysis of biofilm production measured by absorbance readings (OD), it was observed that human isolates had a higher median value (median: 0.891) compared to feline isolates (median: 0.841). However, this difference was not statistically significant. The average biofilm formation readings of isolates from felines were lower than the overall average biofilm formation in human isolates (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Isolate 433 exhibited the highest biofilm production among the human isolates, with an OD reading exceeding 1.7 nm. This isolate showed a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to 51% of the other isolates in the statistical analysis (

Figure 4). Similarly, the G25 isolate displayed the highest biofilm production among the feline isolates, with an OD reading exceeding 1.4 nm. This isolate also showed a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to 86% of the other isolates in the statistical analysis (

Figure 4).

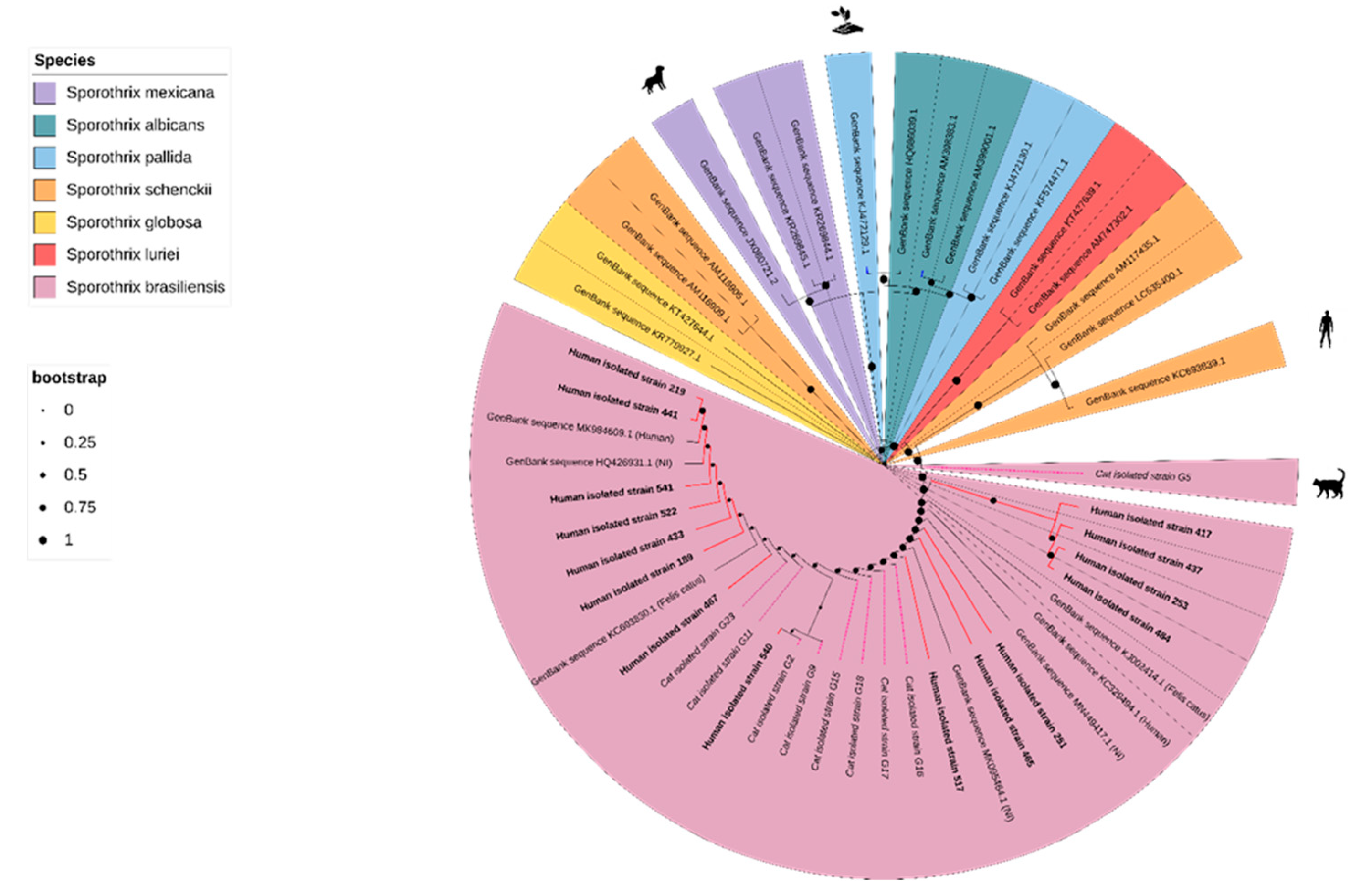

3.8. Phylogenetic Tree

Phylogenetic tree was constructed to illustrate the groupings of the samples of this study with published Sporothrix´ calmodulin-related sequences available in NCBI GenBank. The analysis revealed no distinct separation between groups of human and cat isolates, showing that there is a flow of strains between humans and cats (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The PCR technique, using specific primers for the genus

Sporothrix [

1,

20], confirmed that all isolates in this study belonged to the

Sporothrix genus. Subsequently, sequencing of a sample using Calmodulin gene primers demonstrated that all isolates belonged to the species

Sporothrix brasiliensis. The finding that both human and cat samples belonged to the same species without distinct groupings between them suggests a disease associated with zoonotic transmission. This indicates that the increase in human sporotrichosis cases may be linked to domestic contact with felines, as suggested by Gremião et al., 2017 [

28]. Furthermore, these results suggest that

S. brasiliensis is the predominant species in Belo Horizonte and its metropolitan region, supporting data showing it as the most reported species in Brazil [

10,

11,

29,

30].

In general, a greater antifungal susceptibility was observed in human isolates compared to feline isolates. Although a defined resistance cutoff for antifungals targeting the genus

Sporothrix has not been established by the CLSI, some authors propose cutoff values of 4.0 µg/mL for amphotericin B and 2.0 µg/mL for itraconazole [

31,

32].This outcome may be related to the fact that treatment for most of these animals was discontinued by their respective owners before the recommended period for complete disease remission, according to a report from employees of the Municipal Kennel of Ribeirão das Neves, where the samples were collected. This challenge of maintaining proper adherence to treatment in felines has also been noted by other authors such as Gremião et al., 2015; Lloret et al., 2013 [

5,

33].

All strains included in this study demonstrated the ability to grow at mammalian body temperature, indicating their potential as pathogens for mammals [

34,

35,

36]. An important finding in this study was the high temperature tolerance observed among the isolates, with 98% of them capable of growth at elevated temperatures. Specifically, 87.5% of the isolates grew at 45°C, and 54.1% of the isolates exhibited growth at 50°C. This high thermal tolerance suggests adaptability to mammalian hosts and underscores the pathogenic potential of these isolates. Which would allow fungus survival in regions with high temperatures, for example, in Rio de Janeiro, which was one of the first states to become an endemic region for sporotrichosis [

5]. In recent years, Rio de Janeiro gauged temperatures above 40°C, according to the National Institute of Meteorology (Inmet). These results contrast with findings from other studies, such as one from India where isolates were able to grow at temperatures of 30°C and 37°C but not at 40°C [

37]. In another study from Venezuela, the isolates grew up to 42°C [

38]. This suggests that the strains isolated in the present study, from the metropolitan area of Belo Horizonte, exhibit a high degree of thermotolerance. A higher thermotolerance capacity was observed in feline isolates compared to human samples. One hypothesis for this result is that the animals included in the study may have had the disseminated or extracutaneous form of the disease. According to Almeida-Paes et al., 2015 [

16], isolates capable of growing at higher temperatures are more associated with these clinical manifestations of the disease. This suggests a potential correlation between thermotolerance and disease severity or clinical presentation.

All isolates were able to produce melanin; however, it was possible to observe that the felines samples started the melanization process in the first days of growth. On the other hand, human samples remained whitish in the first days and presented melanization only after the fifth day of cultivation. This result may be explained because the cats included in the study had extensive lesions throughout the body, and melanin gives the fungus a greater ability of tissue invasion in the host [

39]. It is known that the virulence of the fungus provided by melanin is associated with resistance to antifungal agents [

40,

41,

42]. However, in the present study, an increase in resistance to antifungals was not observed in the isolates that produced more melanin than the other isolates. It was also expected that the isolates that presented higher melanin production would grow at higher temperatures [

39,

43]. However, this correlation was not observed in this study. One hypothesis for this result is that melanization and other factors may influence these isolates to grow at higher temperatures.

Urease production is linked to the fungus’s ability to alkalize the pH of its surrounding environment, which can aid in its survival within host cells and contribute to the transition from a saprophytic to a parasitic phase [

44].

In the present study, all isolates demonstrated the ability to produce urease, with the majority being high producers of the enzyme. Interestingly, feline isolates exhibited higher urease production compared to human isolates, with 52% of feline isolates classified as highly urease-productive, whereas only 45% of human isolates showed high urease production levels. This elevated urease production in feline isolates may contribute to the extensive dissemination of lesions observed in these animals. According to Mobley, Island, and Hausinger (1995) [

45], urease facilitates fungal penetration into host cells and tissues, thereby promoting the spread of infection. The higher urease production in feline isolates suggests a potential link between urease activity and the severity or dissemination of sporotrichosis in cats, highlighting urease as a virulence factor that may contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease in this host species.

The finding of higher urease production in strains isolated from felines compared to those from humans is a unique observation not previously documented in the literature. Additionally, it was noted that among the highly urease-producing human isolates, 16.6% exhibited the ability to grow at 50°C. The discovery that 81% of highly urease-producing feline isolates were capable of growing at 50°C is a significant and novel finding. To date, no other studies in the literature have reported a correlation between urease production capacity and thermotolerance in Sporothrix isolates.

In the present study, all strains, whether from humans or felines, demonstrated the ability to produce biofilm. However, interestingly, the average biofilm formation readings of the feline isolates were lower than the overall average of biofilm formation in human isolates. This specific observation regarding biofilm formation differences between feline and human isolates is novel and has not been previously reported in the literature. Other studies have investigated the biofilm formation capacity of

Sporothrix spp. using human isolates [

50,

55,

56]. Biofilm formation is associated with the ability of microbial communities to protect cell viability [

46,

47,

48,

49]. The mechanism behind this protection involves the complex architecture of biofilms and increased expression of drug efflux pumps, which contribute to resistance against antimicrobial agents and host immune factors [

48,

50,

51]. Additionally, biofilms enable microbial communities to adhere to both biotic and abiotic surfaces [

52,

53,

54].

Based on the grouping of sequences from the isolates in this study compared with sequences from a database, it was observed that there was no distinct separation between the isolates from humans and cats. This finding reinforces the notion of a high flux of strains between felines and humans (see

Figure 2). This data confirms what has been demonstrated in other studies, indicating that the transmission of

Sporothrix sp., particularly

S. brasiliensis, within cities is indeed a zoonotic issue [

6,

8,

14,

18,

20,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Therefore, it is crucial to take precautions to prevent increasing outbreaks that may result from poor management of urban hygiene and quality of life for citizens.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, S. brasiliensis is the predominant species in the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, found in both feline and human isolates, and urease production was identified as a crucial factor related to the growth of S. brasiliensis isolates at 50°C. When comparing the isolates of S. brasiliensis (humans vs. felines), we observed that feline isolates exhibit higher urease enzyme production, greater thermotolerance, and more resistance to tested antifungal agents. However, human isolates produce a more robust biofilm than feline isolates. Therefore, we observed in this study that S. brasiliensis isolates demonstrate distinct virulence behaviors depending on the host from which they were isolated, which may be related to various factors, such as the host’s immune system. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the specific mechanisms underlying host adaptation and virulence variability in Sporothrix, which can inform targeted approaches for disease management and control.

Author Contributions

Blenda Fernandes: Conception and design of the study, Acquisition of data, Drafting the article. Rachel Basques Caligiorne: Conception and design of the study, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting the article, Final approval of the version to be submitted. Thais Almeida Marques da Silva: Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting the article. Emanoelle Rodrigues Rutren La Santrer: Bioinformatics studies, Drafting the article. Iara Furtado Santiago: Bioinformatics studies, Drafting the article. Cláudia Barbosa Assunção: Bioinformatics studies, Analysis and interpretation of data. Keterlly Silva Mota de Souza: Conception and design of the study, Acquisition of data. Aline Dias Valério: Conception and design of the study, Analysis and interpretation of data. Sônia Maria de Figueiredo: Acquisition of data, Final approval of the version to be submitted. Susana Johann: Conception and design of the study, Analysis and interpretation of data; Drafting the article, Final approval of the version to be submitted.

Funding

This study was supported by CNPq (Conselho Nacional Pesquisa) and FAPEMIG (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa de Minas Gerais).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte Hospital, Minas Gerais, Brazil, under CAAE no 55549216.2.0000.5138, and by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil, under CEUA no 189/2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans.

Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants of this study, who allow their samples for this research. The authors thank the Brazilian funding agencies: CAPES, CNPq and FAPEMIG.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fernandes B, Caligiorne RB, Coutinho DM, Gomes RR, Rocha-Silva F, Machado AS, Santrer EFR, Assunção CB, Guimarães CF, Laborne MS, Nunes MB, Vicente VA, de Hoog S. A case of disseminated sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2018; 21:34–36. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gaviria M, Martínez-Álvarez JA, Mora-Montes HE. Current Progress in Sporothrix brasiliensis Basic Aspects. J Fungi (Basel). 2023; 9(5):533. [CrossRef]

- Rubio G, Sánchez G, Porras L Alvarado Z. Sporotrichosis: prevalence, clinical and epidemiological features in a reference center in Colombia. Rev. Iberoam Micologia. 2010;27(2):75–9. :. [CrossRef]

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Diagnosis and treatment of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis: What are the options? Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2013; 7:252–259. [CrossRef]

- Gremião IDF, Menezes RC, Schubach TM, Figueiredo AB, Cavalcanti MC, Pereira SA. Feline sporotrichosis: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Med. Mycol. 2015;53(1):15–21. [CrossRef]

- Macêdo-Sales PA, Souto SRLS, Destefani CA, Lucena RP, Machado RLD, Pinto MR, Rodrigues AM, Lopes-Bezerra LM, Rocha EMS, Baptista ARS. Domestic feline contribution in the transmission of Sporothrix in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil: A comparison between infected and non-infected populations. BMC Vet. Res.2018; 14:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues A, Hoog G, Camargo Z. Genotyping species of the Sporothrix schenckii complex by PCR-RFLP of calmodulin. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78(4):383-7. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho JA, Beale MA, Hagen F, Fisher MC, Kano R, Bonifaz A, Toriello C, Negroni R, Rego RSM, Gremião IDF, Pereira SA, de Camargo ZP, Rodrigues AM. Trends in the molecular epidemiology and population genetics of emerging Sporothrix species. Stud Mycol. 2021;100 (100129):1-31. [CrossRef]

- Moncrieff IA, Capilla J, Fernández AM, Fariñas F, Mayayo E. Diferencias en la patogenicidad del complejo de especies Sporothrix en un modelo animal Artículo original. Patol. Rev. Latinoam. 2010; 48(2): 82–87.

- Teixeira MM, de Almeida LG, Kubitschek-Barreira P, Alves FL, Kioshima ÉS, Abadio AK, Fernandes L, Derengowski LS, Ferreira KS, Souza RC, Ruiz JC, de Andrade NC, Paes HC, Nicola AM, Albuquerque P, Gerber AL, Martins VP, Peconick LD, Neto AV, Chaucanez CB, Silva PA, Cunha OL, de Oliveira FF, dos Santos TC, Barros AL, Soares MA, de Oliveira LM, Marini MM, Villalobos-Duno H, Cunha MM, de Hoog S, da Silveira JF, Henrissat B, Niño-Vega GA, Cisalpino PS, Mora-Montes HM, Almeida SR, Stajich JE, Lopes-Bezerra LM, Vasconcelos AT, Felipe MS. Comparative genomics of the major fungal agents of human and animal Sporotrichosis: Sporothrix schenckii and Sporothrix brasiliensis. BMC Genomics. 2014; 15:943. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues AM, Della Terra PP, Gremião ID, Pereira SA, Orofino-Costa R, de Camargo ZP. The threat of emerging and re-emerging pathogenic Sporothrix species. Mycopathologia. 2020;185(5):813–842. [CrossRef]

- Rossow JÁ, Queiroz-Telles F, Caceres DH, Beer KD, Jackson BR, Pereira JG, Gremião IDF, Pereira SA. A one health approach to combatting Sporothrix brasiliensis: Narrative review of an Emerging Zoonotic Fungal Pathogen in South America. J Fungi (Basel). 2020;6(4):247. [CrossRef]

- Aung AK, Teh BM, McGrath C, Thompson PJ. Pulmonary sporotrichosis: Case series and systematic analysis of literature on clinico-radiological patterns and management outcomes. Med. Mycol.2013;51(5):534–544. [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Paes R, de Oliveira MM, Freitas DF, do Valle AC, Zancop-Oliveira RM, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC. Sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Sporothrix brasiliensis is associated with atypical clinical presentations. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014; 8(9): e3094. [CrossRef]

- Belda W, Domingues Passero LF, Stradioto Casolato AT. Lymphocutaneous Sporotrichosis. Refractory to First-Line Treatment. Case Rep. Dermatol. Med. 2021:9453701. [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Paes R, De Oliveira LC, Oliveira MME, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Nosanchuk JD, Zancopé-Oliveira RM. Phenotypic characteristics associated with virulence of clinical isolates from the Sporothrix complex. Biomed Res. Int. 2015; 2015:212308. [CrossRef]

- Arrillaga-Moncrieff I, Capilla J, Mayayo E, Marimon R, Mariné M, Gené J, Cano J, Guarro J. Different virulence levels of the species of Sporothrix in a murine model. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009;15(7):651–655. [CrossRef]

- Rabello VBS, Almeida MA, Bernardes-Engemann AR, Almeida-Paes R, de Macedo PM, Zancopé-Oliveira RM. The Historical Burden of Sporotrichosis in Brazil: a Systematic Review of Cases Reported from 1907 to 2020. Braz J Microbiol. 2022;53(1):231–244. [CrossRef]

- Sidrim JJC, Rocha MFG. Micologia médica à luz de autores contemporâneos. Ed Guanabara Koogan S.A. Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. 2004; 396pp.

- Fernandes B, Santrer EFR, Figueiredo SM, Rocha-Silva F, Assunção CB, Abreu AG, Santiago IF, Johann S, Caligiorne RB. Sporotrichosis: In silico design of new molecular markers for the Sporothrix genus. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2023; 56(e0217-2022):1-4. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues AM, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP. Genotyping species of the Sporothrix schenckii complex by PCR-RFLP of calmodulin. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78(4):383–7.

- CLSI. Reference method for broth dilution. M27-A3 Ref. Method Broth Diluition Antifung. Susceptibility Test. Yeasts; Approv. Stand. - Third Ed. 28, (2008).

- Pierce, CG. , Uppuluri P, Tristan AR, Wormley FL, Mowat E, Ramage G, Lopez-Ribot JL. A simple and reproducible 96 well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat Protoc. 2008; 3(9): 1494–1500. [CrossRef]

- Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform, Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(14):3059–3066. [CrossRef]

- Sela I, Ashkenazy H, Katoh K, Pupko T. GUIDANCE 2: accurate detection of unreliable alignment regions accounting for the uncertainty of multiple parameters. Nucleic Acids Res, 2015; 43(W1): W7-W14. [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics, 2014;30(9):1312-1313. [CrossRef]

- Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2007; 23(1):127-8. [CrossRef]

- Gremião IDF, Miranda LHM, Reis EG, Rodrigues AM, Pereira SA. Zoonotic Epidemic of Sporotrichosis: Cat to Human Transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2017; 13(1):e1006077. [CrossRef]

- Colombo SA, Bicalho GC, de Oliveira CSF, Soares DFM, Salvato LA, Keller KM, Bastos CV, Morais MHF, Rodrigues AM, Cunha JLR, de Azevedo MI. Emergence of zoonotic sporotrichosis due to Sporothrix brasiliensis in Minas Gerais, Brazil: A molecular approach to the current animal disease. Mycoses. 2023; 66: 911-922. [CrossRef]

- Lecca LO, Paiva MT, de Oliveira CSF, Morais MHF, de Azevedo MI, Bastos CV, Keller KM, Ecco R, Alves MRS, Pais GCT, Salvato LA, Xaulim GMD, Barbosa DS, Brandão ST, Soares DFM. Associated factors and spatial patterns of the epidemic sporotrichosis in a high density human populated area: A cross-sectional study from 2016 to 2018. Prev. Vet. Med. 2020; 176:104939. [CrossRef]

- Espinel-Ingroff A, Abreu DBR, Almeida-Paes R, Brilhante RSN, Chakrabarti A, Chowdhary A, Hagen F, Córdoba S, Gonzalez GM, Govender NP, Guarro J, Johnson EM, Kidd SE, Pereira SA, Rodrigues AM, Rozental S, Szeszs MW, Ballesté-Alaniz R, Bonifaz A, Bonfietti LX, Borba-Santos LP. Capilla J. Colombo AL, Dolande M, Isla MG, Melhem MSC, Mesa-Arango AC, Oliveira MME, Panizo MM, Camargo ZP, Zancope-Oliveira RM, Meis JF, Turnidge J. Multicenter, International Study of MIC / MEC Distributions for Definition of Epidemiological Cutoff Values for Sporothrix Species Identified by Molecular Methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017; 61(10):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Paes R, Brito-Santos F, Figueiredo-Carvalho MHG, Machado ACS, Oliveira MME, Pereira SA, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Zancopé-Oliveira RM. Minimal inhibitory concentration distributions and epidemiological cutoff values of five antifungal agents against Sporothrix brasiliensis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2017; 112(2): 376–381. [CrossRef]

- Lloret A, Hartmann K, Pennisi MG, Ferrer L, Addie D, Belák S, Boucraut-Baralon C, Egberink H, Frymus T, Gruffydd-Jones T, Hosie MJ, Lutz H, Marsilio F, Möstl K, Radford AD, Thiry E, Truyen U, Horzinek MC. Sporotrichosis in cats: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2013; 15(7): 619–623. [CrossRef]

- He D, Zhang X, Gao S, You H, Zhao Y, Wang L. Transcriptome Analysis of Dimorphic Fungus Sporothrix schenckii Exposed to Temperature Stress. Int. Microbiol. 2021; 24(1): 25–35. [CrossRef]

- Hogan LH, Klein BS, Levitz SM. Virulence factors of medically important fungi. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1996; 9(4):469–488. [CrossRef]

- Nosanchuk JD, Casadevall A. Impact of melanin on microbial virulence and clinical resistance to antimicrobial compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50(11):3519–3528. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh A, Maity PK, Hemashettar BM, Sharma VK, Chakrabarti A. Physiological characters of Sporothrix schenckii isolates. Mycoses. 2002; 45(11-12): 449–454. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza M, Alvarado P, Díaz-de-Torres E, Lucena L, De Albornoz MC. Comportamiento fisiológico y de sensibilidad in vitro de aislamientos de Sporothrix schenckii mantenidos 18 años por dos métodos de preservación. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2005; 22(3): 151–156. [CrossRef]

- Madrid IM, Xavier MO, Mattei AS, Fernandes CG, Guim TN, Santin R, Schuch LFD, Nobre MO, Araújo-Meireles MC. Role of melanin in the pathogenesis of cutaneous sporotrichosis. Microbes Infect. 2010; 12(2): 162–165. [CrossRef]

- García-Carnero LC, Martínez-Álvarez JA. Virulence Factors of Sporothrix schenckii. J. Fungi. 2022; 8(3): 318. [CrossRef]

- Morris-Jones R, Youngchim S, Gomez BL, Aisen P, Hay RJ, Nosanchuk JD, Casadevall A, Hamilton AJ. Synthesis of melanin-like pigments by Sporothrix schenckii in vitro and during mammalian infection. Infect. Immun. 2003; 71(7): 4026–4033. [CrossRef]

- Van-Duin D, Casadevall A, Nosanchuk JD. Reduces Their Susceptibilities to Amphotericin B and Caspofungin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2002; 46(11): 3394–3400. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, ES. Pathogenic roles for fungal melanins. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000; 13(4): 708–717. [CrossRef]

- Mirbod-Donovan F, Schaller R, Hung CY, Xue J, Reichard U, Cole GT. Urease produced by Coccidioides posadasii contributes to the virulence of this respiratory pathogen. Infect. Immun. 2006;74(1):504–515. [CrossRef]

- Mobley HLT, Island MD, Hausinger RP. Molecular biology of microbial ureases. Microbiol. Rev. 1995; 59(3): 451–480. [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos GMP, Borba-Santos LP, Vila T, Gremião IDF, Pereira SA, De Souza W, Rozental SI. Sporothrix spp. Biofilms Impact in the Zoonotic Transmission Route: Feline Claws Associated Biofilms, Itraconazole Tolerance, and Potential Repurposing for Miltefosine. Pathogens. 2022; 11(2): 206. [CrossRef]

- Di Bonaventura G, Pompilio A, Picciani C, Iezzi M, D’Antonio D, Piccolomini R. Biofilm formation by the emerging fungal pathogen Trichosporon asahii: Development, architecture, and antifungal resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006; 50(10):3 269–3276. [CrossRef]

- Fanning S, Mitchell AP. Fungal biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(4):1–4. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell KF, Zarnowski R, Andes DR. Fungal Super Glue: The Biofilm Matrix and Its Composition, Assembly, and Functions. PLoS Pathog. 2016; 12(9): 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Brilhante RSN, Fernandes MR, Pereira VS, Costa AC, Oliveira JS, de Aguiar L, Rodrigues AM, de Camargo ZP, Pereira-Neto WA, Sidrim JJC, Rocha MFG. Biofilm formation on cat claws by Sporothrix species: An ex vivo model. Microb. Pathog. 2021; 150:104670. [CrossRef]

- Finkel JS, Mitchell AP. Genetic control of Candida albicans biofilm development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011; 9(2): 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Boltz JP, Smets BF, Rittmann BE, Van Loosdrecht MCM, Morgenroth E, Daigger GT. From biofilm ecology to reactors: a focused review. Water Sci. Technol. 2017; 75(7-8): 1753–1760. [CrossRef]

- Cavalheiro M, Teixeira MC. Candida Biofilms: Threats, challenges, and promising strategies. Front. Med. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018; 5:28. [CrossRef]

- Ramage G, Rajendran R, Sherry L, Williams C. Fungal biofilm resistance. Int J Microbiol. 2012; 2012:528521. [CrossRef]

- Garcia LGS, de Melo-Guedes GM, Fonseca XMQC, Pereira-Neto WA, Castelo-Branco DSCM, Sidrim JJC, de Aguiar-Cordeiro R, Rocha MFG, Vieira RS, Brilhante RSN. Antifungal activity of different molecular weight chitosans against planktonic cells and biofilm of Sporothrix brasiliensis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;143:341–348. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Herrera R, Flores-Villavicencio LL, Pichardo-Molina JL, Castruita-Domínguez JP, Aparicio-Fernández X, López MS, Villagómez-Castro JC. Analysis of biofilm formation by Sporothrix schenckii. Med. Mycol. 2021; 59(1): 31–40.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).