1. Introduction

Candida species are among the most prevalent human fungal pathogens worldwide and represent the fourth most common cause of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in the US. Notably,

C. albicans,

C. glabrata,

C. parapsilosis and

C. tropicalis account for approximately 90% of cases of candidemia [

1]. Recently,

C. auris, a new opportunistic

Candida species has emerged and quickly spread worldwide [

2]. In only 7 years this yeast, which is difficult to treat and displays clonal inter- and intra-hospital transmission, has become widespread across several countries, causing a broad range of healthcare-associated invasive infections, including not only central venous catheter (CVC) correlated candidemia , but also pericarditis, respiratory and urinary tracts infections [

3]. Invasive infections by

C. auris mostly occur in critically ill patients, especially patients in intensive care units (ICUs) and those undergoing invasive procedures [

4]. This fungus is of clinical concern for several reasons: 1) about 90% of the clinically isolated strains are resistant to fluconazole and some strains are resistant to all currently available antifungal drugs, thus dramatically limiting the therapeutic options [

5]; 2) although the recently setting up of rapid methods, such as the “Clade-Finder” [

6] has been developed to improve the clade determination for

C. auris, the correct identification in daily routine is still challenging, often leading to inappropriate management; 3) people can be colonized by

C. auris without being aware of it, and such colonization can last for long time and cause epidemic outbreaks in healthcare facilities, although the possible spread in communities cannot be excluded; 4) the ability to evade the host immune system makes this fungus highly virulent [

7]; 5) it causes a high mortality rate in the invasive forms (in-hospital mortality rate of

C. auris candidemia ranges from 30 to 60%) [

5]; 6) it has the ability to form a biofilm that makes the fungus very resistant to disinfectants and therefore particularly hard to clear it also from the surfaces.

C. auris strains are classified in 6 distinct clades named after the geographical areas where the strains were first isolated: South Asian (clade I), East Asian (clade II), African (clade III), South American (clade IV), Iran (clade V) and Singapore (clade VI) [

8,

9,

10]. Differences in genetic backgrounds, biochemical characteristics, and antifungal susceptibility patterns make each clade unique [

11]. Interestingly, not only antifungal susceptibility pattern seems to be different among the different clades as well as within the same clade, but also its virulence traits, such as thermo-tolerance, halo-tolerance, melanization and the capacity to form pseudo-hyphae seem to be strain-dependent [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] . Several aspects of

C. auris biology, such as its genomic and phenotypic characteristics, as well as its pathogenicity, have been studied [

17,

18,

19]. Interestingly, a possible role exerted by the natural environment on the emergence and transmission of this fungus has been hypothesized. It has been suggested, for over a decade, that mycoses in mammalians are infrequent, and this is probably due to the struggle of most fungal species to survive and replicate at the temperatures occurring in mammalian bodies [

20]. Recently, it has been reported that some fungal species are able to increase their thermal tolerance, therefore becoming able to adapt to warmer temperatures in the environment, and consequently defeating the protection provided by the endothermy to mammalians [

21]. For this reason, global warming is becoming a matter of concern, because it exerts selective pressure on some fungal species that may become pathogenic and lead to the emergency of novel fungal diseases. The quick and simultaneous appearance of

C. auris in different and distant regions of our planet supports the “global warming emergence hypothesis”, pointing to this species as a prototype of novel fungal pathogens capable of breaking the mammalian endothermal barrier as a consequence of the global warming adaptation [

22,

23]. Indeed,

C. auris is characterized by genetic variability, capacity to form biofilm, resistance to antifungal drugs and several mechanisms (such as thermotolerance and halotolerance) that make this species capable to adapt to changes in its environment [

24,

25]. In addition, variations in temperature, salinity and pH have been demonstrated to play a role in the capacity of

C. auris to cause disease [

26,

27,

28]. As mentioned above, most of the virulence traits of

C. auris are strain-specific; hence the specific biological and phenotypical behaviour are peculiar of each single strain and could modify its virulence potential. Here, we studied the biological features, antimicrobial susceptibility and phenotypic characteristics of

C. auris strain CDC B11903 in comparison to the

C. albicans reference strain B90028, grown at three different temperatures: 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C to analyse the impact of temperature on their virulence and phenotypes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Candida Strains and Growth Conditions

The experiments were carried out using the C. auris reference strain CDC B11903 and the C. albicans reference strain B90028. Both strains were grown on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA, Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA), supplemented with chloramphenicol (SDA + CAF), for 24 hr at 30 °C. After incubation, Candida yeasts were harvested by washing the slant culture with sterile saline solution (0.85% NaCl; Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, Massachusetts, U.S.). The cell density of Candida suspensions was estimated by direct cell count, using a Bürker chamber, and adjusted to the desired concentration.

2.2. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of C. auris CDC B11903

Antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) was performed using the Thermo Scientific™ SENSITITRE™ YEASTONE™ panels according to manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. Briefly, the

C. auris CDC B11903 strain, grown on SDA at 30 °C, was sub-cultured at the same condition to ensure purity and viability. To prepare the inoculum, four single colonies of at least 1 mm in diameter were picked, suspended in sterile 0.85% sodium chloride solution, vortexed, and adjusted using a Sensititre™ nephelometer to a transmittance equal to a 0.5 McFarland standard at a wavelength of 530 nm as a stock solution. Further, 20 μL of the stock solution were transferred to the Sensititre™ YeastOne™ (SYO) broth medium, and the final density of the working solution was adjusted to 2 × 10

3 CFU/mL by a Bürker chamber, according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27M44S guidelines. Then, 100 µL of the stock solution were transferred into each well of the SYO panels and incubated without agitation at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 24 hr before visual reading. Evident yeast growth was observed as the colour changed from blue (negative, indicating no growth) to pink (positive, indicating growth). We assessed various antifungal agents, including fluconazole, voriconazole, itraconazole, isavucozonale, posaconazole, caspofungin, micafungin, anidulafungin and amphotericin B. Resistance was determined through tentative breakpoints provided by the CDC [

29] for amphotericin B (≥ 2 μg/mL), caspofungin (≥ 2 μg/mL), micafungin (≥ 4 μg/mL) anidulafungin (≥ 4 μg/mL) and fluconazole (≥ 32 μg/mL) while no tentative minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) breakpoints are available for other azoles. MIC were visually determined as–the lowest concentration that produced visual inhibition, compared to the control growth. The results were expressed as geometric means (GM) of two independent experiments performed in duplicate.

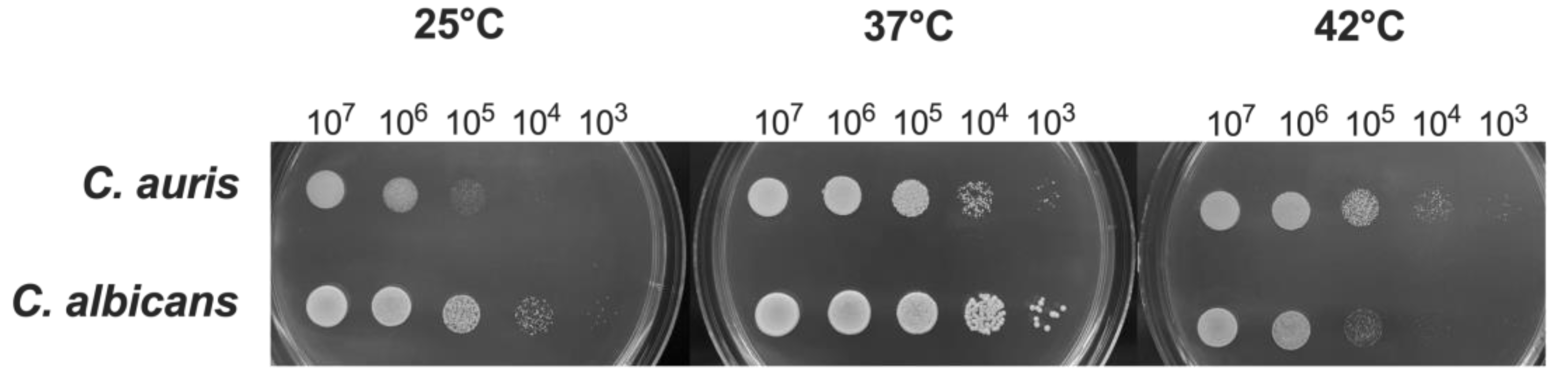

2.3. Growth Determination

C. auris and C. albicans yeast cells in log-phase were counted, resuspended at 1x107 CFU/mL in 5 mL of YPD and then serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy). Twenty μL of each fungal suspension were spotted in a plate of SDA + CAF. The plates were then incubated at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 24-48 hr. After incubation, the spot growth was visually assessed.

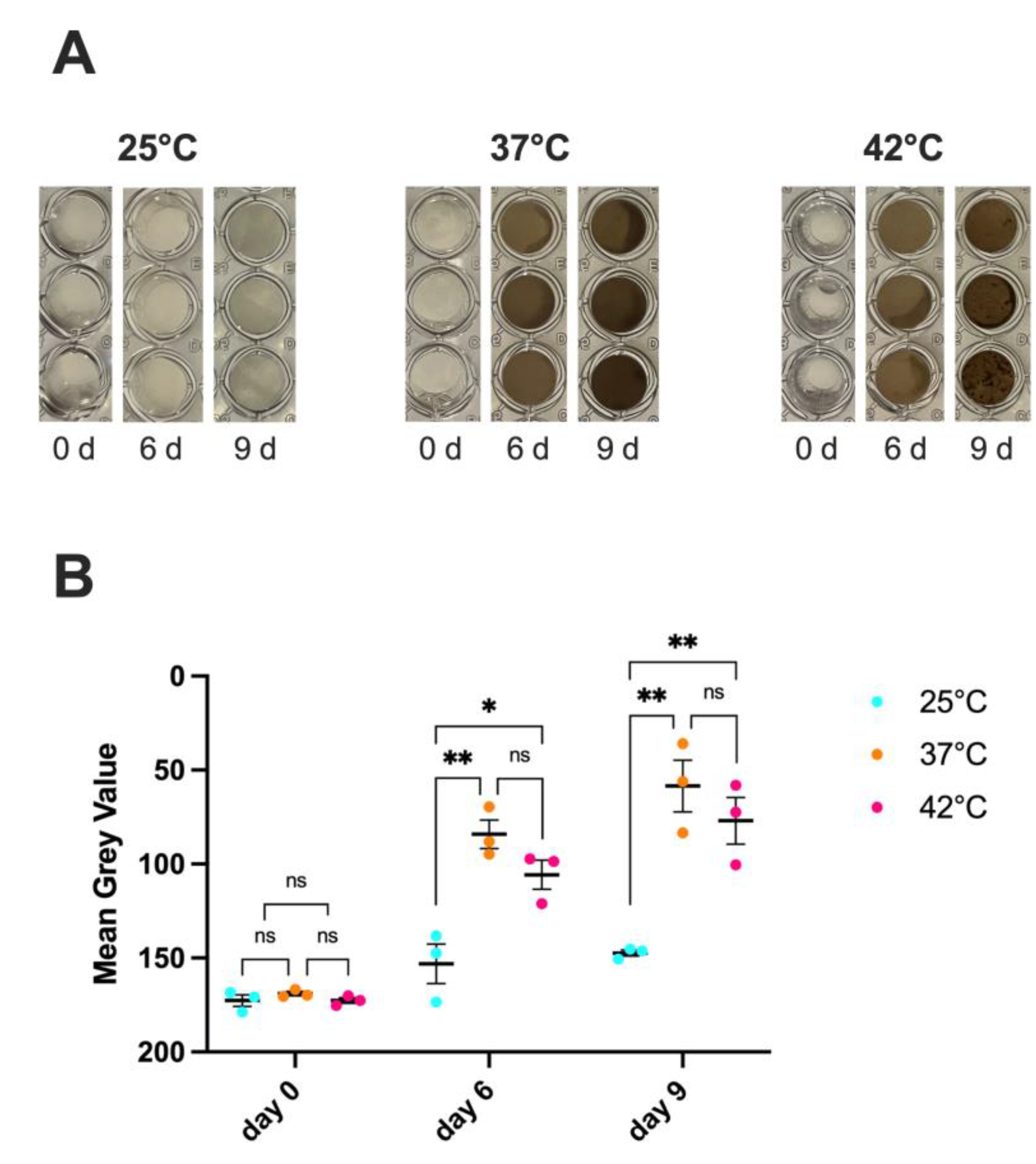

2.4. Melanin Production

To analyse the melanization capacity of

C. auris, we used a protocol described by Smith D.F.Q. and collaborators [

15]. Briefly,

C. auris cells (1x10

7 CFU/200 μL/well in triplicate) were cultured at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 9 days in a minimal medium containing 15 mM C

6H

12O

6, 10 mM MgSO

4, 29,4 mM KH

2PO

4, 13 mM Glycine, 3M Vitamin B1, 1 mM L-DOPA, at pH 5.5. On days 0, 6, and 9 the plates were visually assessed and photographed.

C. albicans grown in the same experimental conditions and in medium alone served as internal controls. The experimental protocol used to test melanization, as well as results from

C. albicans, were shown in

Supplementary Figure S1A. To quantify signal intensity within the wells, images were analyzed using ImageJ2 software (version 2.14.0/1.54f). Each image was first converted to 8-bit grayscale (Image → Type → 8-bit). A region of interest (ROI) corresponding to the inner area of a well was manually defined. This same ROI was then applied to three different wells within each image to measure the mean gray value (Analyze → Measure), ensuring consistency in the area analyzed. The mean gray value represents the average pixel intensity within the selected region and was used as a quantitative measurement of signal intensity.

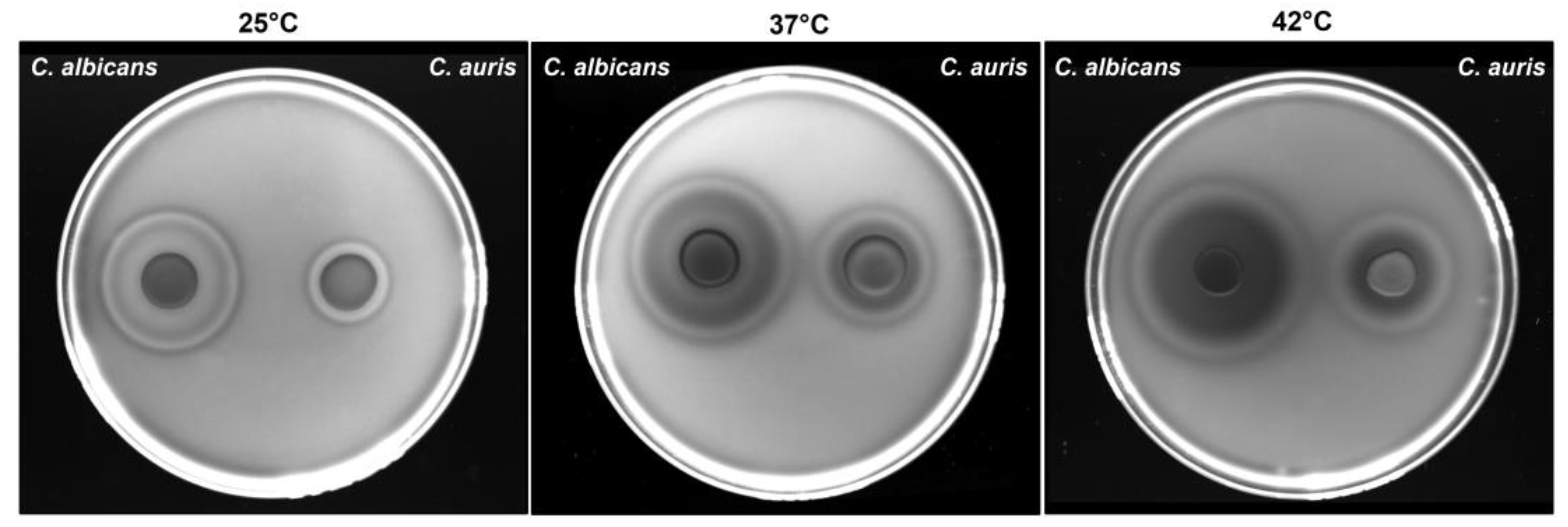

2.5. Determination of Haemolytic Activity

The haemolytic activity of

C. auris was assessed using the method described by Luo

et al. [

30].

C. albicans was used as a positive control due to its significant haemolytic activity [

30]. Briefly, fungal strains were cultured on SDA at 37 °C for 24 hr, then harvested, washed with sterile PBS, and adjusted to 1x10⁸ cells/mL using a haemocytometer. A 10-μL aliquot was spotted onto SDA supplemented with 3% glucose and 7% fresh sheep blood, followed by incubation at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C in 5% CO₂ for 48 hr. Haemolysis was assessed by observing the formation of a translucent halo around the inoculum under transmitted light (iBright Imaging System, Thermo Fisher Scientific, US). The diameters of the lysis zones and colonies were measured using a computerized image analysis system (iBright Analysis Software, Thermo Fisher Scientific, US). Haemolytic activity (Hz) was determined following the method of Price

et al. [

31], calculating the ratio of the colony diameter (mm) to the total diameter of the colony plus the halo of the haemolysis zone. Assays were conducted in triplicate, and results were expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. According to the Hz index, haemolytic activity was classified as follows: Hz = 1.0: no haemolytic activity; Hz = 0.999 – 0.700: low haemolytic activity; Hz = 0.699 – 0.400: moderate haemolytic activity; Hz = 0.399 – 0.100: high haemolytic activity.

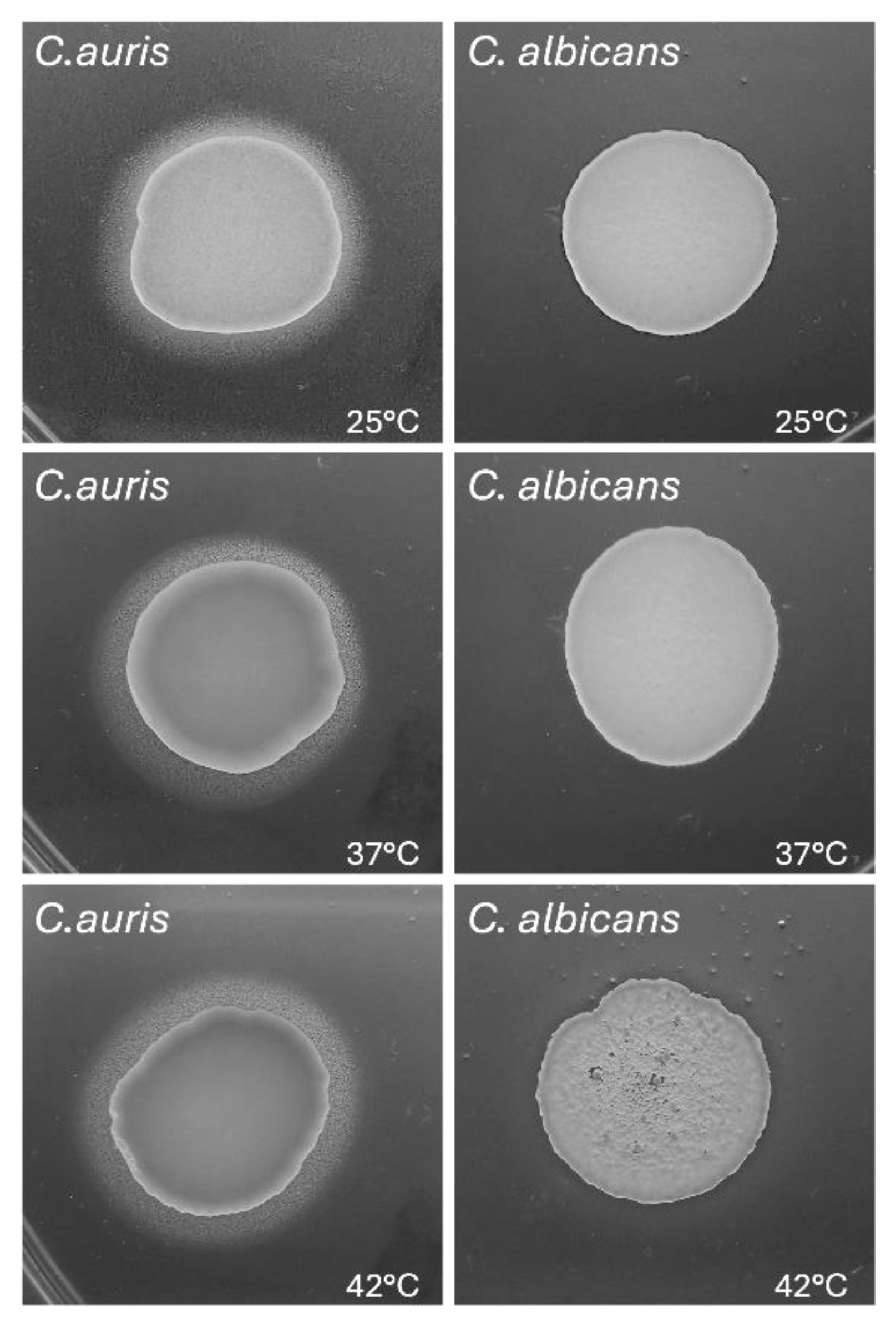

2.6. Phospholipase Activity

Extracellular phospholipase activity was evaluated by the egg yolk agar plate method described by Price

et al. [

31]. Briefly, 10 μL of

C. auris suspension (1x10

8/mL) were spotted onto the egg yolk agar medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, US) and incubated at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 4 days. After incubation, the diameter of precipitation zone around the colony was determined.

C. albicans strain B90028 was used as a control strain. Phospholipase activity (Pz index) was calculated by applying the following formula:

On the basis of Pz value, phospholipase activity was classified in 5 types as follows:

Pz value = 1: no phospholipase activity; Pz value = 0.90-0.99: weak phospholipase activity (+); Pz value = 0.80-0.89: poor phospholipase activity (++); Pz value = 0.70-0.79: moderate phospholipase activity (+++); Pz value <0.70: intense phospholipase activity (++++).

2.7. Lipase Activity

Lipase activity of

C. auris and

C. albicans was performed as previously described, with minor modifications [

32]. Briefly, 20 μL of

C. auris and

C. albicans suspensions (1x10

8/mL) were spotted onto an agar medium prepared as follows: 10.0 g of Bacto Peptone (BD Biosciences), 5.0 g of NaCl, 0.1 g of CaCl

2, 15.0 g of agar in 1000 mL of distilled water. After sterilization by autoclave, the medium was allowed to cool to about 50 °C and 5 mL of Tween 80 (Sigma-Aldrich) were added. The plates inoculated with fungi were incubated at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 48 hr. After the incubation the production of lipase (Lz) was expressed as the ratio of diameter of a colony to the total diameter plus zone of precipitation. The results were expressed as the average of the values obtained. The ranges of activity according to the Lz index were established as follows: high: Lz = 1: none; Lz value = 0.90–0.99: weak; Lz value = 0.70– 0.89: moderate; Lz value ≤ 0.69: high [

33].

2.8. Germ Tube Test

The ability of

C. auris to germinate was assessed using the germ tube test [

34]. Briefly, the strain was grown on SDA + CAF for 24 hr at 30 °C. After incubation, three different isolated

C. auris colonies of at least 1 mm diameter were inoculated into 0.5 mL of FCS and incubated at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C, respectively. After 3 hr of incubation, 10 μL of

Candida cell suspension in FCS were transferred onto a glass slide for examination by a light microscope (Olympus, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) with 100× magnification objective lenses. Images from one representative experiment carried out at each temperature were captured.

2.9. Filamentous Growth Assay

To evaluate the filamentous growth in C. auris, 2 × 103 yeast cells were cultured in 96-well plates in 200 μL of RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FCS, and incubated at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 6 hrs and 24 hr. After incubation, the non-adherent cells were removed by washing the wells three times with PBS and the filamentous growth was visualized microscopically by a light microscope (Olympus, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) with 40× magnification objective lenses. The images were documented with the accompanied digital camera.

2.10. Biofilm Quantification by Crystal Violet and XTT Assays

To evaluate the

in vitro biofilm formation by

C. auris at different temperatures, 2x10

5 fungal cells were cultured in 96-well plates in 200 μL of RPMI 1640 medium (pH 7.0), supplemented with 10% FCS and incubated at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 24 hr. After incubation, planktonic

C. auris cells were gently aspirated and the wells were washed at least thrice with warm PBS. The biofilm biomass and metabolic activity were evaluated by using crystal violet (CV) staining and 2,3-Bis-(2-Methoxy-4-Nitro-5-Sulfophenyl)-2H-Tetrazolium-5-Carboxanilide (XTT) reduction assay, respectively, as previously described [

35]. In all experiments, the absorbance values of the negative control wells (containing no fungal cells) were subtracted from the values of the test wells to account for any background absorbance.

2.11. Human Epithelial Cells and Infection Protocol

In the experiments involving epithelial cell infection, two different human cell lines were employed. The urothelial cell line, T24 cells (Cytion 300352), were cultivated in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM-F12) (Sial, Italy) supplemented with L-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/mL) (Euroclone SpA, Italy), streptomycin (100 μL/mL) (Euroclone SpA, Italy) and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Sial, Italy), and incubated at 37 °C + 5% CO2. The pulmonary cell line, BEAS-2B cells (ATCC CRL-3588) were cultivated in DMEM High Glucose (Sial, Italy) supplemented with L-glutamine (2 mM, Sial, Italy), penicillin (100 U/mL) (Euroclone SpA, Italy), streptomycin (100 μL/mL) (Euroclone SpA, Italy), and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Sial, Italy), and incubated at 37 °C + 5% CO2. Both cell lines were kept viable by subculturing twice a week.

For generating epithelial monolayer, 5x105 cells were seeded into the wells of a 24-well plate (SPL Life Sciences, Korea) (1 mL/well) and incubated at 37 °C + of 5% CO2 (48 hr for T24 cells, 24 hr for BEAS-2B cells). Before being infected, epithelial monolayers were washed with Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS, Sial, Italy), and fresh medium supplemented with 5% FBS was added to each well. Cells were infected with 5x105 CFU of fungi (Multiplicity of Infection, MOI, 1) obtained from a YPD broth fungal culture grown overnight at 37 °C under agitation. After the infection, the plate was incubated at 37 °C + of 5% CO2.

2.12. Adhesion onto Abiotic and Biotic Substrates

The C. auris and C. albicans adhesion to abiotic and biotic surfaces was evaluated at different temperatures. To assess the adhesion on abiotic surface, 1 mL of Candida suspension (5x105 CFU/mL) in YPD broth (Condalab, Spain) was seeded into the wells of a 24-well plate in triplicate. The plate was incubated at 25 °C, 37 °C, or 42 °C for 90 min. Subsequently, the medium was removed, and the wells were washed with PBS to remove non-adherent fungi. Fungal cells adhered to the plastic were detached by adding Soybean Casein Digest Lecithin Polysorbate 80 Medium (SCDLP-80, Biotec, Dueville, Italy) and vigorously pipetting. Samples were diluted, plated onto Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA, Oxoid, UK) and incubated at 37 °C for 24/48 hr. Colony Forming Units (CFU) were counted, and the percentage of adhesion was calculated considering the inoculum as 100%.

T24 or BEAS-2B epithelial cell monolayer was infected with 5x105 CFU (MOI 1) of C. auris or C. albicans and incubated at 37 °C or 42 °C for 90 min. Then, the medium was removed, and non-adherent fungal cells were removed through a PBS wash. Epithelial cells were lysed by adding 1 mL of 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich, USA) to the wells and pipetting. Samples were diluted, plated onto SDA, and incubated at 37 °C for 24-48 hr. Colony Forming Units (CFU) were counted, and the percentage of adhesion was calculated as above.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to analyse the distribution of data within experimental groups. All statistical analyses were performed by using GraphPad Prism 10.3 software.

Statistical differences between groups were assessed by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test or by Two-Way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple-comparison test.

Values of *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001 were considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Survival and growth at physiological body temperature in humans are essential prerequisites for microbial invasion and pathogenicity. Most fungal pathogens are adapted to environmental conditions and thus they do not grow well at relatively high temperatures, as those occurring within the human body, both in physiological conditions (37 °C) or in severe febrile status (over 40 °C). Interestingly,

C. auris strains differ in their growth and virulence factors

in vitro. The ability of some

C. auris isolates to grow at 37 °C and 40 °C appears to be similar to that of

C. albicans, and certain isolates are able to grow even at 42 °C [

40]. In this study we have evaluated the impact of different temperatures on biological properties and antifungal susceptibility of

C. auris reference strain CDC B11903. This strain has been found to grow better at temperatures ranging from 37 °C to 42 °C rather than at 25 °C. Moreover, no difference in biofilm formation has been observed at any of the temperatures tested in terms of total biomass production; however, a reduction in biofilm metabolic activity has been observed both at 25 °C and at 42 °C, with respect to 37 °C. The 25 °C temperature has shown a negative impact on

C. auris growth, when the fungal inoculum had been reduced. This is in line with the data obtained by the antifungal susceptibility test, which show lower values of MIC at 25 °C as compared to 37 °C, while no difference in MIC values has been observed between 37 °C and 42 °C (except for anidulafungin, whose MIC value has increased at 42 °C). These data suggest that in our experimental condition

C. auris CDC B11903 has the capacity to tolerate high temperatures when exposed to drastic increases. On the other hand, temperatures lower than 37 °C seem to have a more negative impact on the fungus, since no growth has been observed at inoculum below 1x10

5 CFU/mL and the MIC values are lower.

A growing number of emerging cases of

C. auris have been reported with fungal resistance to the standard antifungal treatments including azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes, making these infections difficult to treat. In the United States, about 90% of

C. auris isolates have been reported to be resistant to fluconazole, about 30% to amphotericin B, and less than 2% to echinocandins [

41,

42]. Fungal resistance is one of the paramount points in antifungal stewardship. It has been demonstrated that

C. albicans is more susceptible to caspofungin at 37 °C than at 30 °C, in a calcineurin-dependent pathway and not related to

FKS,

CHS, or

CHT genes, all involved in echinocandins resistance [

43]. Based on this evidence, we have performed AFST at the three different temperatures of 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for

C. auris CDC B11903. First, the Sensititre™ YeastOne™ YO10 AST Plate (Thermofisher, Milan, Italy) investigation, with our minor modifications, has worked at all the tested temperatures, supporting the employment of this method for

C. auris AFST profile in clinical and research settings, as previously reported [

44]. Regarding the obtained MIC, our results show that the strain CDC B11903 does not exhibit any resistance to the tested drugs. Indeed, variations in MIC have been highlighted at the selected temperatures, with the lowest values observed at 25 °C for all the tested antifungal drugs and increasing values at 37 °C and 42 °C. Interestingly, these results are in contrast to what had been reported for

C. albicans [

43]. Recent pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis of

C. auris in a mouse model of infection indicates that, under standard dosing, the breakpoint for amphotericin B should be 1 or 1.5, i.e., values similar to those determined for other

Candida species [

45]. Therefore, isolates with a MIC ≥ 2 should now be considered resistant. In our case,

C. auris exhibits an AmB MIC of 0.5 at 25 °C and at 37 °C, while the high temperature of 42 °C results to have increased the MIC value to 1 µg/mL. The temperature-dependent increase in AmB MIC for

C. auris suggests a potential reduction in efficacy under febrile conditions, thereby challenging the reliability of current breakpoints, particularly for clinical isolates of

C. auris and in regions where AmB resistance or elevated MICs have been reported. This underscores the need for susceptibility testing that better reflects clinical realities, especially in immunocompromised patients. Antifungal tolerance is often associated with metabolic dormancy, a reversible low-activity state that reduces drugs efficacy [

46,

47,

48]. Thus, lower MIC at 25 °C may reflect a decrease in metabolic activity and a downregulation of targets like 14-demethylase, β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase, and ergosterol biosynthesis enzymes. Indeed, it has been suggested that higher temperatures accelerate fungal growth and increase susceptibility to drugs targeting metabolism and cell division (e.g., fluconazole, ketoconazole, 5-fluorouracil) [

49]. Similarly, it has been reported that elevated temperatures enhance lipid synthesis, potentially sensitizing fungi to amphotericin B and sterol-inhibiting azoles

[50]. In addition, higher temperatures promote azole uptake through increased membrane solubility [

51,

52]. Differently, our data show that while metabolic activity peaked at 37 °C, MIC remained stable compared to 42 °C, suggesting that thermally induced tolerance mechanisms, rather than metabolic output alone, may drive resistance phenotypes.

The capacity of

C. auris strain CDC B11903 to tolerate high temperatures is only one of the characteristics that delineates its capacity to behave as an opportunistic pathogen. Several non-pathogenic fungi can grow at temperatures around 37 °C. Indeed, all the fungal species belonging to the mycobiome are tolerant to the human body temperature and only a few of them cause disease and mostly in severely immunocompromised subjects [

53]

. It follows that this prerequisite must be owned also by those fungi that have adapted to grow within the human body. Hence, the thermotolerance displayed by

C. auris strain CDC B11903 is not sufficient,

per se, to define it as a potentially opportunistic fungal pathogen [

54]. It is acknowledged that what keeps harmless the members of the commensal mycobiota, in comparison to opportunistic fungal pathogens, is not the capacity to grow at body temperature, but rather the lack of additional virulence factors. Therefore, we analysed the presence of virulence traits of

C. auris CDC B11903 strain that are expressed at body temperature. The production of melanin is an important virulence trait of several

C. auris strains [

15]. Here, we show for the first time that

C. auris strain B11903 can produce melanin when grown at 37 °C and 42 °C, further suggesting its adaptation to the human body temperature: indeed, in such condition this strain can survive, grow and express its virulence factors. Fungal melanin pigments have strong antioxidant properties that allow them to resist oxidative damage caused by the host immune cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils oxidative bursts [

55]. In addition, melanin can bind to and inactivate antimicrobial peptides and antimicrobial enzymes that the host typically uses to degrade and kill fungi during infection, as well as antifungal drugs used to treat infections [

56,

57,

58]. Fungal melanin, located in the fungal cell wall, can alter cell wall composition and physically mask pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that would otherwise be recognized and bound by host’s pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs). These changes may lead to diminished recognition by host immune cells. Hence, our results point to a key role exerted by melanin at 37 °C and 42 °C that increases resistance to fungal drugs and immune responses.

One of the key virulence attributes of pathogenic fungi, including

Candida species, is their ability to acquire nutrients and breach host barriers through the secretion of hydrolytic enzymes and toxins. In this study, we have assessed the production of haemolysins, phospholipases, and lipases by

C. auris CDC B11903 at different temperatures representative of environmental and host conditions. The haemolytic capacity of

C. auris is evident at all the tested temperatures, though more pronounced at 37 °C and 42 °C with respect to 25 °C, as shown by the wider haemolytic halos. Both β-haemolysis and α-haemolysis have been detected, with the latter emerging exclusively at the higher temperatures. This dual haemolytic profile has been reported also in other clinical isolates of

C. auris, particularly under host-mimicking conditions [

59] and it may reflect an adaptive response to evade host immune defences through the lysis of red blood cells. However, unlike

C. albicans, which displays strong haemolytic activity at all temperatures, the performance of

C. auris at 25 °C remains low, suggesting that its full virulence potential may require physiological or febrile host temperatures. This observation supports the hypothesis that temperature acts as a signal for virulence activation, as previously demonstrated in

C. albicans [

60]. Further investigations are required to elucidate the nature of the haemolytic factor, specifically to determine whether it is enzymatic or toxin-mediated.

Phospholipase activity, a well-known virulence trait associated with host cell membrane disruption and tissue invasion, has been detected consistently in

C. auris CDC B11903 across all the tested temperatures. The Pz values, which remain in a narrow range (0.77–0.78), indicate a moderate but stable phospholipase production. This thermostability suggests that

C. auris maintains a constitutive phospholipase expression regardless of environmental conditions, including host-relevant febrile temperatures. Such stability may represent an adaptive advantage, particularly during colonization and systemic infection, where fluctuating temperatures could otherwise impair enzymatic virulence responses. Interestingly, previous studies have reported inconsistent phospholipase activity in

C. auris clinical isolates, with some strains exhibiting little to no detectable enzymatic production [

40,

61]. Our findings, therefore, contribute to the growing evidence that phospholipase expression in

C. auris is strain-dependent and not uniformly absent or negligible as initially suggested in early characterizations of this species. The persistence of phospholipase activity across physiological and stress temperatures in this strain supports its potential contribution to pathogenicity, particularly in niches where host membranes represent a primary barrier to fungal invasion.

Moreover, lipase activity appears to be influenced by temperature in

C. auris, with a high and moderate lipase production at 25 °C and 37 °C, respectively, which is also maintained at 42 °C. These results align with previous findings indicating that lipase expression is regulated under host-mimicking conditions and may play a role in skin colonization and biofilm formation [

61]. Conversely,

C. albicans does not show lipase activity at 42 °C, confirming that the expression of this enzyme is highly variable and context-dependent, even among established pathogens. The lipase activity of

C. auris also at febrile-range temperatures may confer this species a selective advantage during systemic infection, or in the colonization of warm, lipid-rich niches such as skin folds. Moreover, given the high lipophilicity of human skin and medical devices, this enzymatic activity may underlie the persistence and transmission of

C. auris in healthcare settings. Nonetheless, our data highlight the importance of not underestimating enzymatic virulence factors in

C. auris, which may play a more active role in pathogenesis than previously recognized.

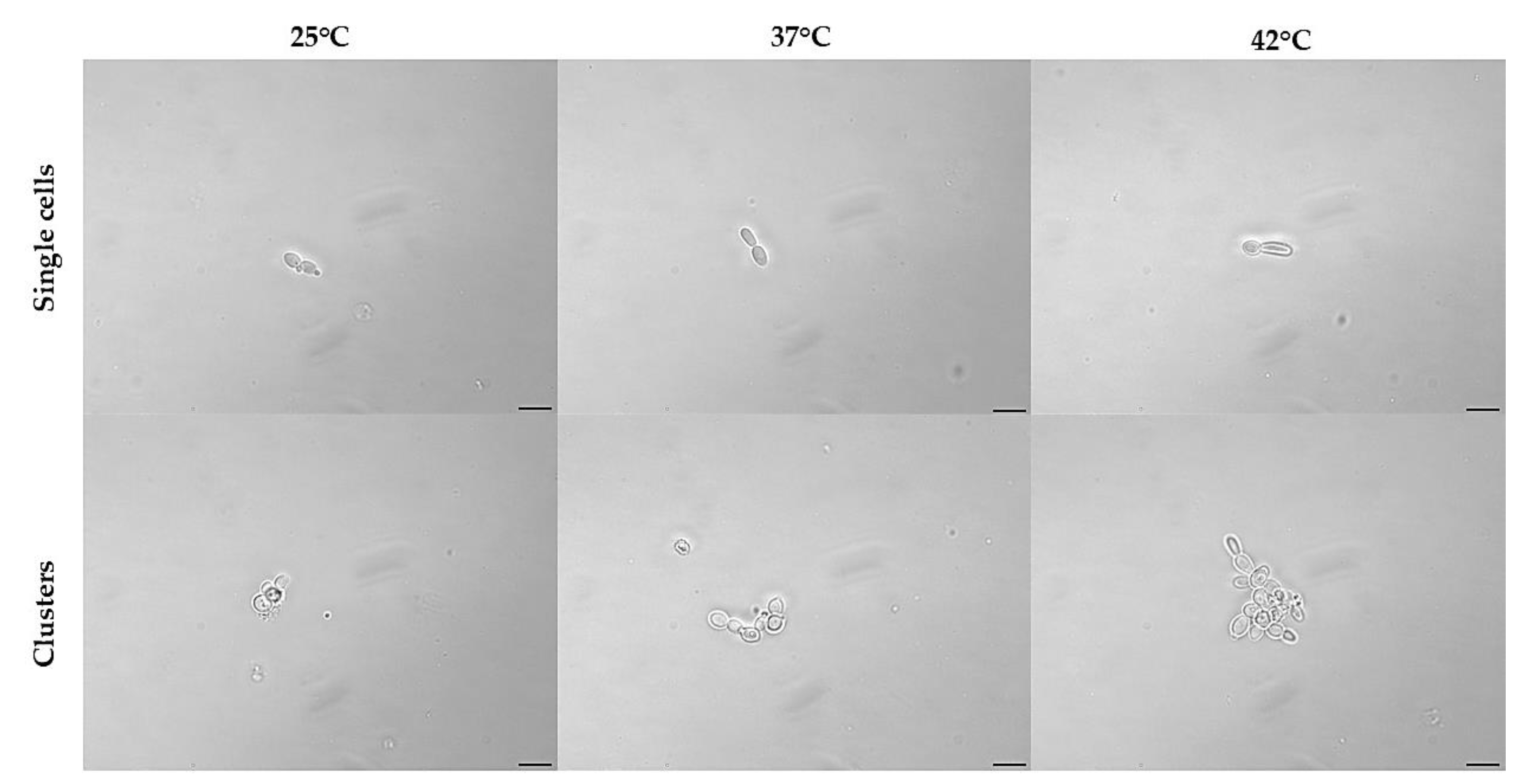

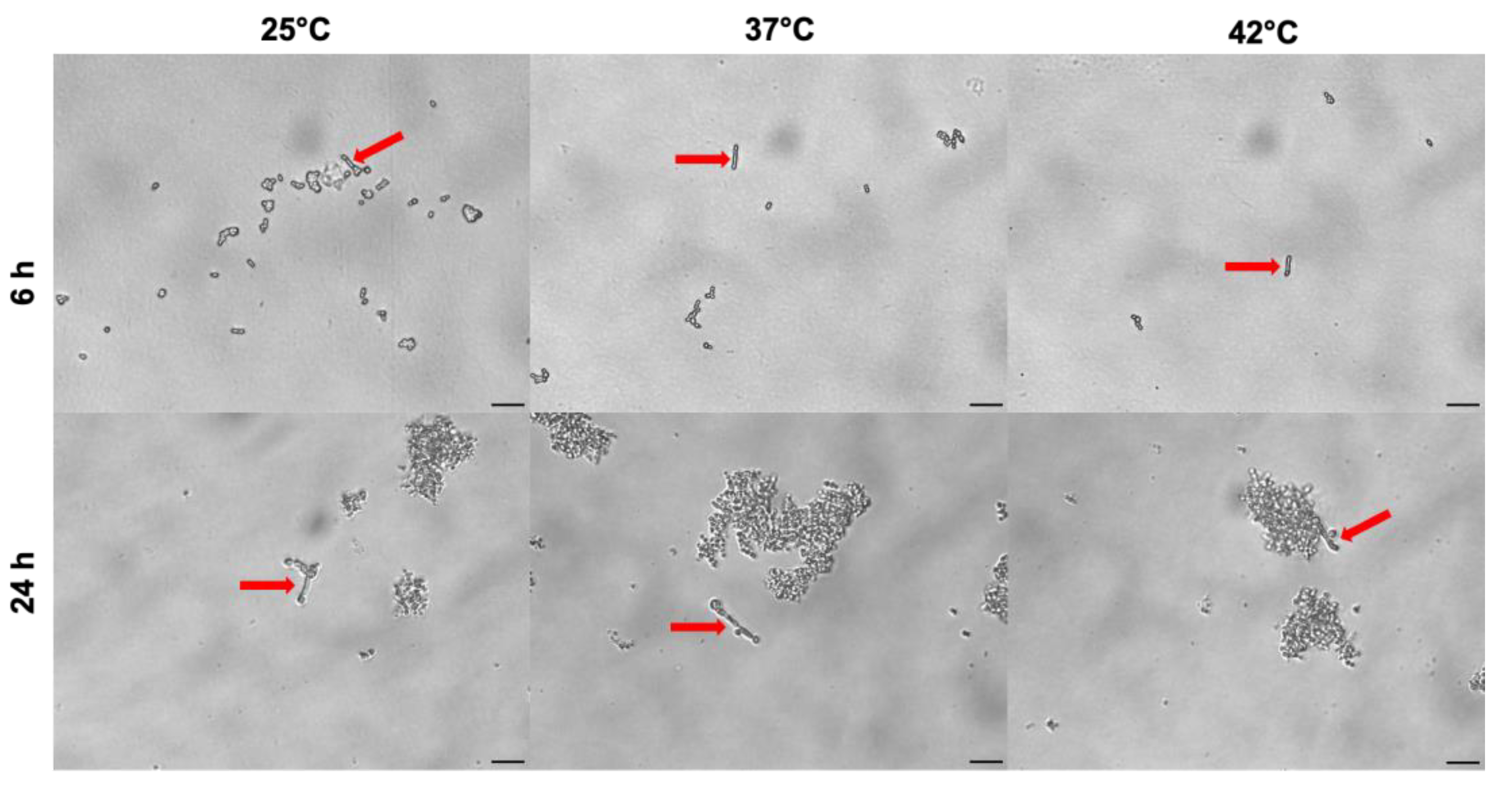

Moreover, our results show that temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 42 °C, do not substantially affect pseudo-hyphae formation in

C. auris. Global warming has been proposed as a contributing factor in the generation and dissemination of high thermotolerant

C. auris strains [

62,

63,

64]. In line with previous studies, the

C. auris strain CDC B11903 has been unable to form true hyphae, when cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, or in the presence of 100% FCS. Under these experimental conditions, only pseudo-hyphae, stemming from single yeast cells rather than from cells gathered in clusters have been detected. The production of pseudo-hyphae as a virulence factor in planktonic cells is supported also by previous

in vivo experimental models showing that non-aggregating isolates of

C. auris exhibit more pathogenicity than aggregating isolates; in addition, such non-aggregating isolates have been shown to be even more virulent than

C. albicans [

14]. On the other hand, strains capable of forming aggregates have been shown to be more resistant to disinfectants, azole antifungals and immune responses. In addition, they are characterized by a higher ability to colonise (and persist on) biotic and abiotic surfaces. Here, we show an aggregative profile for

C. auris CDC B11903. Both pseudo-hyphae formation and aggregative capacity are not modified by changing the temperature from 25 °C to 42 °C.

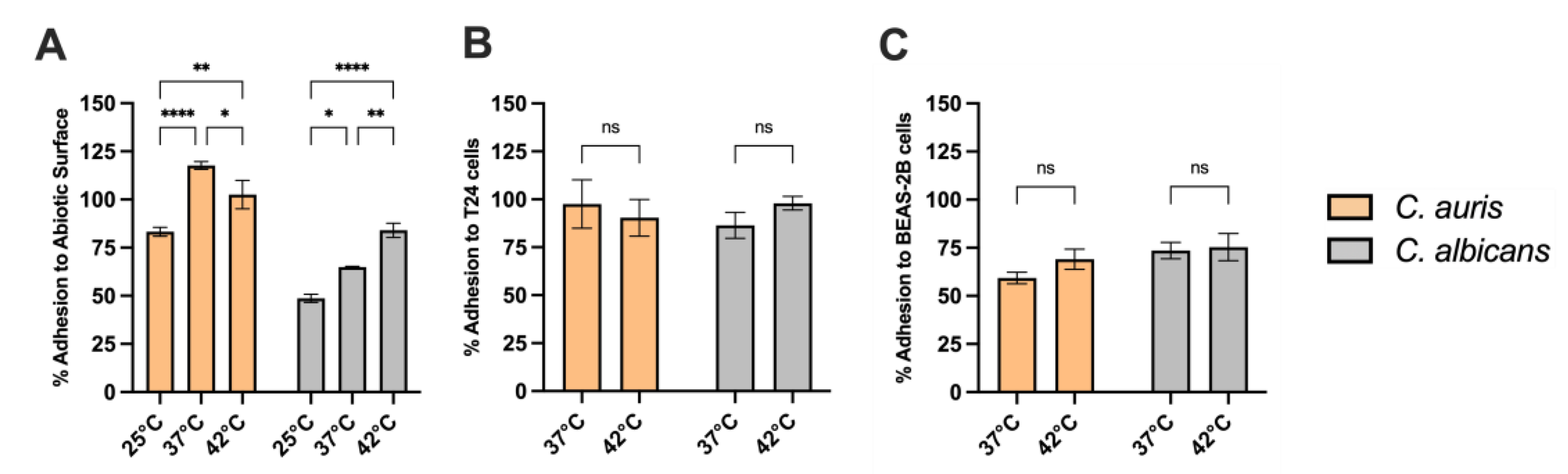

Adherence to both abiotic and biotic surfaces constitute a pivotal early event in fungal pathogenesis, enabling colonization, biofilm development, and persistence within host tissues and healthcare settings. In this study, C. auris CDC B11903 exhibits significantly higher adhesion capacity to abiotic substrates than C. albicans throughout all the tested temperatures, with adhesive capacity increasing from 25 °C to 37 °C and stabilizing at 42 °C. This thermally responsive trend suggests optimal activation of adhesion-related mechanisms at human body temperature, with maintained performance under febrile conditions, reflecting the induction of adhesins or a cell wall restructuring. The enhanced adhesion under both normothermic and hyperthermic conditions may facilitate early colonization and biofilm establishment, complicating eradication efforts due to inherent antifungal tolerance.

Furthermore, C. auris adheres efficiently to T24 urothelial and BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells at both 37 °C and 42 °C, indicating a broad thermotolerance in host-surface interactions. This epithelial tropism may partially explain its frequent detection in urinary and respiratory sites, particularly among critically ill or immunocompromised individuals. Collectively, these observations challenge earlier assumptions regarding the limited virulence of C. auris, instead revealing a consistent and temperature-resilient adhesive phenotype that may act synergistically with enzymatic activity and biofilm formation to promote infection.

Overall, these findings provide a comprehensive view of the virulence arsenal of C. auris CDC B11903 and reinforce the notion that temperature-dependent regulation of specific traits—such as enzyme secretion and melanin production—may critically shape the pathogenic behaviour of this emerging fungal pathogen.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, R.G., C.M. and E.P.; methodology, T.C., N.P., L.S., L.T.D., S.K., S.S., E.S.P.; software, T.C., N.P., L.S., L.T.D., S.K., S.S., E.S.P.; validation, R.G., C.M., and E.P.; formal analysis, T.C., N.P., L.S., L.T.D., S.K., S.S., E.S.P., A.A., R.G., C.M., M.C., and E.P.; investigation, T.C., N.P., L.S., L.T.D., S.K., S.S., E.S.P.; resources, R.G., C.M., A.A. and E.P.; data curation, T.C., N.P., L.S., L.T.D., S.K., S.S., E.S.P., R.G., C.M. and E.P.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C., N.P., L.S., R.G., C.M., A.A., and E.P.; writing—review and editing, T.C., N.P., L.S., R.G., M.C., C.M., A.A., and E.P.; supervision, R.G., C.M., and E.P.; project administration, R.G. and E.P.; funding acquisition, R.G., C.M., A.A. and E.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

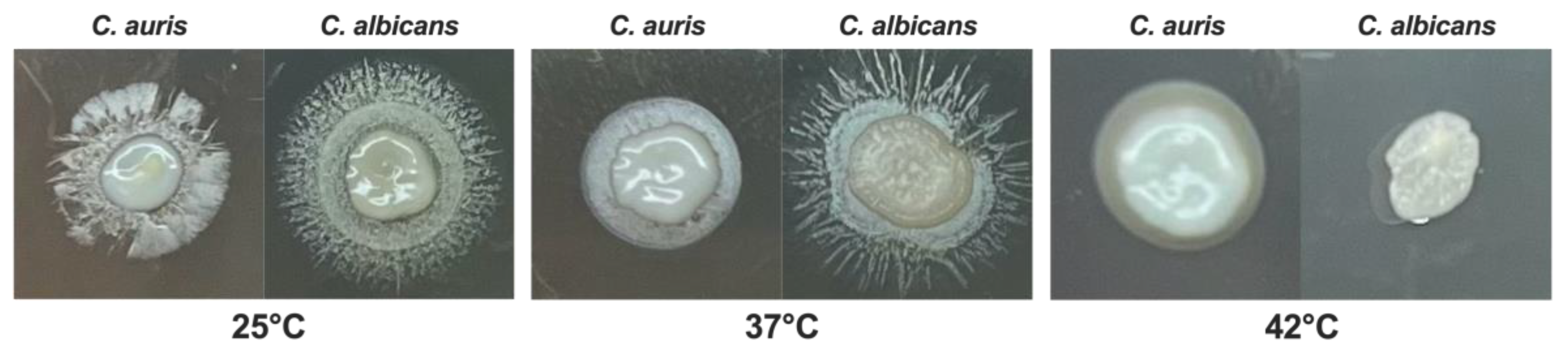

Figure 1.

Impact of temperature on C. auris and C. albicans growth.C. auris and C. albicans yeasts cells (20 μL from 1x107 CFU/mL to 1x103 CFU/mL) were spotted on SDA + CAF and allowed to grow at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 24 hr. A representative image out of 4 with similar results is shown.

Figure 1.

Impact of temperature on C. auris and C. albicans growth.C. auris and C. albicans yeasts cells (20 μL from 1x107 CFU/mL to 1x103 CFU/mL) were spotted on SDA + CAF and allowed to grow at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 24 hr. A representative image out of 4 with similar results is shown.

Figure 2.

Impact of temperature on C. auris melanin production.C. auris CDC B11903 melanization capacity after 0, 6 and 9 days at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. A representative image out of 3 with similar results is shown (A). Mean grey value ± SEM of melanin production by C. auris (B). Differences between groups were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; ns, not significant.

Figure 2.

Impact of temperature on C. auris melanin production.C. auris CDC B11903 melanization capacity after 0, 6 and 9 days at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. A representative image out of 3 with similar results is shown (A). Mean grey value ± SEM of melanin production by C. auris (B). Differences between groups were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; ns, not significant.

Figure 3.

Impact of temperature on C. auris and C. albicans haemolytic activity. C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 haemolytic activity at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. A representative image out of 3 with similar results is shown.

Figure 3.

Impact of temperature on C. auris and C. albicans haemolytic activity. C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 haemolytic activity at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. A representative image out of 3 with similar results is shown.

Figure 4.

Impact of temperature on C. auris and C. albicans phospholipase activity.C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 phospholipase activity at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. A representative image out of 3 with similar results is shown.

Figure 4.

Impact of temperature on C. auris and C. albicans phospholipase activity.C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 phospholipase activity at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. A representative image out of 3 with similar results is shown.

Figure 5.

Impact of temperature on C. auris and C. albicans lipase activity.C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 lipase activity at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C after 48 hr of incubation. A representative image out of 3 with similar results is shown.

Figure 5.

Impact of temperature on C. auris and C. albicans lipase activity.C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 lipase activity at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C after 48 hr of incubation. A representative image out of 3 with similar results is shown.

Figure 6.

Effect of temperatures on germ tube formation in C. auris.C. auris cells were cultured in the presence of 100% FCS at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. The germ tube formation was analysed by light microscopy after 3 hr of incubation. The images were acquired by a light microscope with 40x magnification objective lenses. For each temperature condition, one representative experiment is shown. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Figure 6.

Effect of temperatures on germ tube formation in C. auris.C. auris cells were cultured in the presence of 100% FCS at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. The germ tube formation was analysed by light microscopy after 3 hr of incubation. The images were acquired by a light microscope with 40x magnification objective lenses. For each temperature condition, one representative experiment is shown. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Figure 7.

Effect of temperature on phenotypic switching from yeast to pseudohyphae in C. auris.C. auris cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 24 hr. The phenotypic transition from yeast-to-hyphal morphotype was analysed by light microscopy at 6 and 24 hr. Arrows point to pseudo-hyphal growth in single and not clustered C. auris cells. Images were acquired by a light microscope with 40x magnification objective lenses. One representative experiment out of three for each temperature is shown. Scale bar: 20 µm.

Figure 7.

Effect of temperature on phenotypic switching from yeast to pseudohyphae in C. auris.C. auris cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C for 24 hr. The phenotypic transition from yeast-to-hyphal morphotype was analysed by light microscopy at 6 and 24 hr. Arrows point to pseudo-hyphal growth in single and not clustered C. auris cells. Images were acquired by a light microscope with 40x magnification objective lenses. One representative experiment out of three for each temperature is shown. Scale bar: 20 µm.

Figure 8.

C. auris and C. albicans adhesion to abiotic surfaces and epithelial cells. The impact of the different temperatures on adhesion of C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans 90028 was evaluated on abiotic surfaces (A), T24 urothelial cells (B), and BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells (C). Data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Differences between groups were analysed by Two-Way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple-comparison test. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; **** p<0.0001.

Figure 8.

C. auris and C. albicans adhesion to abiotic surfaces and epithelial cells. The impact of the different temperatures on adhesion of C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans 90028 was evaluated on abiotic surfaces (A), T24 urothelial cells (B), and BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells (C). Data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Differences between groups were analysed by Two-Way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple-comparison test. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; **** p<0.0001.

Table 1.

Antifungal susceptibility testing of C. auris CDC B11903 at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. The values are the geometric means of the MICs (µg/mL).

Table 1.

Antifungal susceptibility testing of C. auris CDC B11903 at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. The values are the geometric means of the MICs (µg/mL).

| Temperature |

25 °C |

37 °C |

42 °C |

| Amphotericin B |

0.50 μg/mL |

1.00 μg/mL |

1.00 μg/mL |

| Fluconazole |

4.00 μg/mL |

8.00 μg/mL |

8.00 μg/mL |

| Isavuconazole |

0.008 μg/mL |

0.12 μg/mL |

0.12 μg/mL |

| Itraconazole |

0.03 μg/mL |

0.12 μg/mL |

0.12 μg/mL |

| Posaconazole |

0.015 μg/mL |

0.06 μg/mL |

0.06 μg/mL |

| Voriconazole |

0.015 μg/mL |

0.06 μg/mL |

0.06 μg/mL |

| Micafungin |

0.03 μg/mL |

0.06 μg/mL |

0.06 μg/mL |

| Anidulafungin |

0.06 μg/mL |

0.07 μg/mL |

0.10 μg/mL |

| Caspofungin |

0.06 μg/mL |

0.12 μg/mL |

0.12 μg/mL |

Table 2.

Haemolytic activity of C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 at 2 5°C, 37 °C and 42 °C. Hz: haemolytic index. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Differences between groups were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. **** p< 0.0001 (C. auris 25 °C vs 37 °C), #### p<0.0001 (C. auris 25 °C vs 42 °C).

Table 2.

Haemolytic activity of C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 at 2 5°C, 37 °C and 42 °C. Hz: haemolytic index. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Differences between groups were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. **** p< 0.0001 (C. auris 25 °C vs 37 °C), #### p<0.0001 (C. auris 25 °C vs 42 °C).

| Temperature |

25 °C |

37 °C |

42 °C |

| |

Hz |

Categorization |

Hz |

Categorization |

Hz |

Categorization |

| C. auris |

0.690±0.073 |

low |

0.46±0.020**** |

moderate |

0.38±0.003####

|

high |

| C. albicans |

0.376±0.011 |

high |

0.322±0.036 |

high |

0.251±0.011 |

high |

Table 3.

Extracellular phospholipase activity of C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. Pz: phospholipase activity index. The results are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments carried out in duplicate. Differences between groups were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. ns (C. auris 25 °C vs 37 °C), ns (C. auris 25 °C vs 42 °C).

Table 3.

Extracellular phospholipase activity of C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. Pz: phospholipase activity index. The results are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments carried out in duplicate. Differences between groups were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. ns (C. auris 25 °C vs 37 °C), ns (C. auris 25 °C vs 42 °C).

| Temperature |

25 °C |

37 °C |

42 °C |

| |

Pz |

Categorization |

Pz |

Categorization |

Pz |

Categorization |

| C. auris |

0. 780±0.055 |

moderate |

0.780±0.063 |

moderate |

0.770±0.030 |

moderate |

| C. albicans |

1 |

none |

1 |

none |

1 |

none |

Table 4.

Lipase activity of C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. Lz: lipase activity index. The results are the mean ± SD of three different experiments. Differences between groups were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. ###p< 0.001 (C. auris 25 °C vs 37 °C and 25 °C vs 42 °C), ###p<0.001 (C. albicans 25 °C vs 42 °C and 37 °C vs 42 °C).

Table 4.

Lipase activity of C. auris CDC B11903 and C. albicans B90028 at 25 °C, 37 °C and 42 °C. Lz: lipase activity index. The results are the mean ± SD of three different experiments. Differences between groups were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. ###p< 0.001 (C. auris 25 °C vs 37 °C and 25 °C vs 42 °C), ###p<0.001 (C. albicans 25 °C vs 42 °C and 37 °C vs 42 °C).

| Temperature |

25 °C |

37 °C |

42 °C |

| |

Lz score |

Categorization |

Lz score |

Categorization |

Lz score |

Categorization |

| C. auris |

0.48±0.014 |

High |

0.72±0.059 |

Moderate |

0.71±0.044 |

Moderate |

| C. albicans |

0.46±0.043 |

High |

0.50±0.113 |

High |

1.00 |

none |

Table 5.

Effect of temperature on C. auris biofilm biomass and metabolic activity. The impact of the different temperatures was evaluated on biofilm biomass and metabolic activity in C. auris. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed by using One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; ns: not significant.

Table 5.

Effect of temperature on C. auris biofilm biomass and metabolic activity. The impact of the different temperatures was evaluated on biofilm biomass and metabolic activity in C. auris. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed by using One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; ns: not significant.

| Temperature |

Biofilm biomass (OD 595 nm) |

p-value |

Biofilm metabolic

activity (OD 490 nm) |

p-value |

| 25 °C |

0.764 ± 0.234 |

- |

0.580 ± 0.112 |

- |

| 37 °C |

0.772 ± 0.236 |

ns |

0.731 ± 0.083 |

**vs 25 °C (p<0.01) |

| 42 °C |

0.749 ± 0.248 |

ns |

0.614 ± 0.087 |

*vs 37 °C (p<0.05) |