Submitted:

15 May 2024

Posted:

16 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

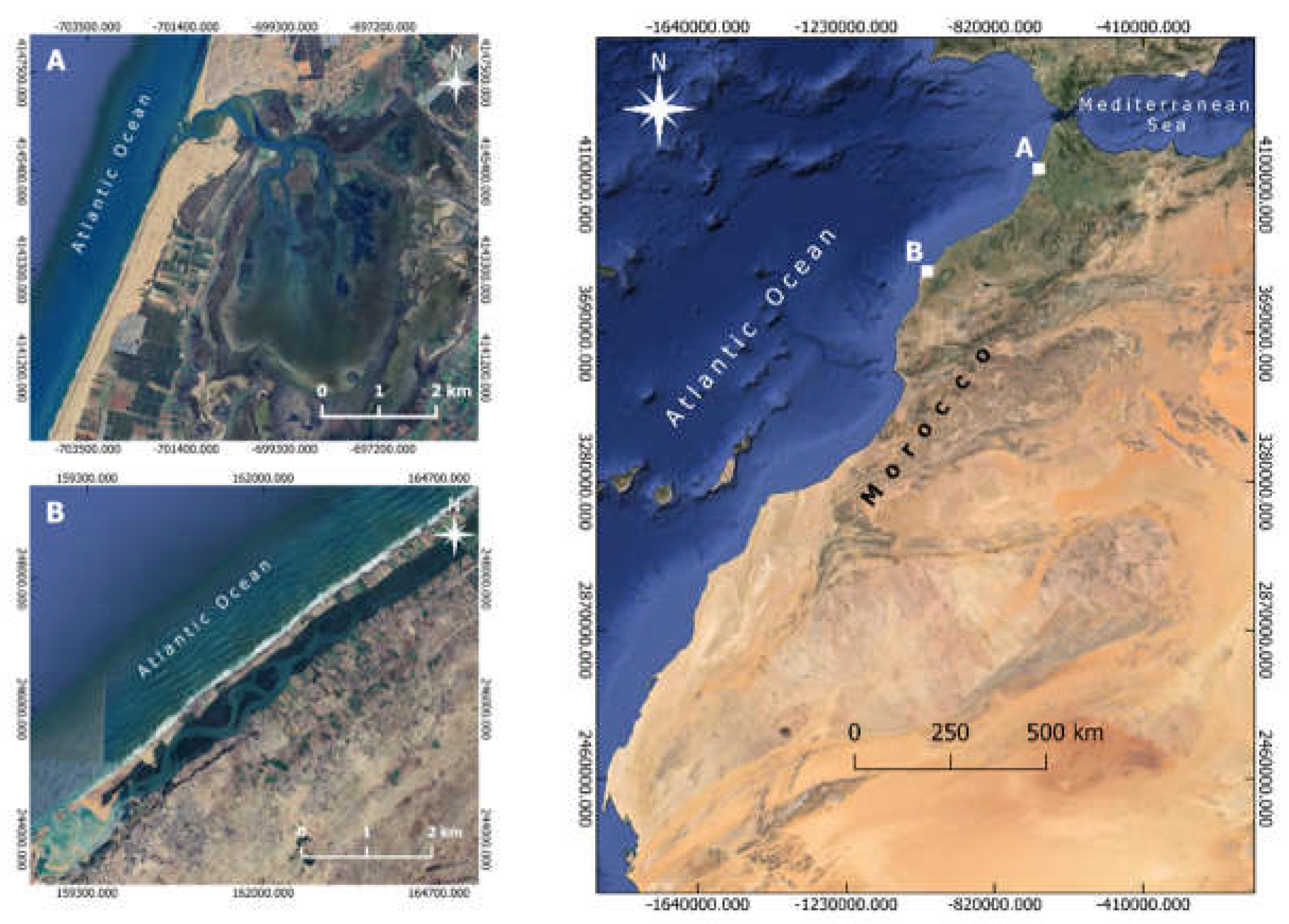

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Sampling and Microscopic Analysis

2.3. DNA Extraction, Amplification and Sequencing

3. Results

3.1. Biometric Characteristics of Analysed Specimens of Callinectes sapidus

3.2. The Hemolymph Smear Assay with Neutral Red

3.3. PCR-Based Method and Sequence Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nehring, S. Invasion history and success of the American blue crab Callinectes sapidus in European and adjacent waters. In the wrong place-alien marine crustaceans: distribution, biology and impacts. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. 2011, pp. 607-426. [CrossRef]

- Nehring, S. Callinectes sapidus. In: NOBANIS- Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet. Online Database of the European Network on Invasive Alien Species, NOBAMIS. 2012. http://www.nobanis.org.

- Williams, A.B. The swimming crabs of the genus Callinectes (Decapoda: Portunidae). Fish. Bull. 1974, 72, 685–798. [Google Scholar]

- Castriota, L.; Andaloro, F.; Costantini, R.; De Ascentiis, A. First record of the Atlantic crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Crustacea: Brachyura: Portunidae) in Abruzzi waters, central Adriatic Sea. Acta Adriat. 2012, 53, 467–471. [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier, E.L. Sur un Callinectes sapidus M. Rathbun trouvé à Rocheford. Bull. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat. 1901, 7, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Giordani Soika, A. II Neptunus pelagicus (L. ) nell’Alto Adriatico. Natura 1951, 42, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pashkov, A.N.; Reshetnikov, S.I.; Bondarev, K.B. The capture of the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus, Decapoda, Crustacea) in the Russian sector of the Black Sea. Russ. J. Biol. Invasions 2012, 3, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejón, D.; Guerao, G. A new record of the American blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae), from the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula. BioInvasions Rec. 2013, 2, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, R.Ç.; Terzi, Y.; Feyzioğlu, A.M.; Şahin, A.; Aydın, M. Genetic Characterization of the Invasive Blue Crab, Callinectes sapidus (Rathbun 1896), in the Black Sea. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 39, 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streftaris, N.; Zenetos, A. Alien marine species in the Mediterranean - the 100 ‘Worst Invasives’ and their impact. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2006, 7, 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartosia, N.; Anastasiadis, D.; Bazairi, H.; Crocetta, F.; Deidun, A.; Despalatović, M.; Di Martino, V.; Dimitriou, N.; Dragičević, B.; Dulčić, J.; Durucan, F.; Hasbek, D.; Ketsilis-Rinis, V.; Kleitou, P.; Lipej, L.; Macali, A.; Marchini, A.; Ousselam, M.; Piraino, S.; Stancanelli, B.; Theodosiou, M.; Tiralongo, F.; Todorova, V.; Trkov, D.; Yapici, S. New Mediterranean Biodiversity Records. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2018, 19, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oussellam, M.; Benhoussa, A.; Pariselle, A.; Rahmouni, I.; Salmi, M.; Agnèse, J.F.; Selfati, M.; El Ouamari, N.; Bazairi, H. First and southern-most records of the American blue crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Decapoda, Portunidae) on the African Atlantic coast. Bioinvasions Rec. 2023, 12, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouti, A.; Belattmania, Z.; Nadri, A.; Serrão, E.; Encarnação, J.; Teodósio, A.; Reani, A.; Sabour, B. The Invasive Atlantic Blue Crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun 1896 Expands its Distributional Range Southward to Atlantic African Shores: First Records Along the Atlantic Coast of Morocco. BioInvasions Rec. 2022, 11, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairi, H. , González-Ortegón, E. Additional records of the blue crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 in the Moroccan Sea, Africa. BioInvasions Rec. 2022, 11, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanevakis, S.; Wallentinus, I.; Zenetos, A.; Leppäkoski, E.; Çinar, M.E.; Oztürk, B.; Grabowski, M.; Golani, D.; Cardoso, A.C. Impacts of marine invasive alien species on ecosystem services and biodiversity: a pan-European review. Aquat. Invasions 2014, 9, 391–423. [Google Scholar]

- Crowl, T.A.; Crist, T.O.; Parmenter, R.R.; Belovsky, G.; Lugo, A.E. The spread of invasive species and infectious disease as drivers of ecosystem change. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 2008. 6, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedknegt, M.A.; Feis, M.E.; Wegner, K.M.; Luttikhuize, P.C.; Buschbaum, C.; Camphuysen, K.C.J.; Vander Meer, J.; Thieltges, DW. Parasites and marine invasions: Ecological and evolutionary perspectives. J. Sea Res. 2016, 113, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojko, J.; Burgess, A.L.; Baker, A.G.; Orr, C.H. Invasive Non-Native Crustacean Symbionts: Diversity and Impact. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2021, 186, 107482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.R.; Becker, C.R.; Simonis, J.L.; Duffy, M.A.; Tessier, A.J.; Cáceres, C.E. Friendly competition: evidence for a dilution effect among competitors in a planktonic host–parasite system. Ecology 2009, 90, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.W.; Paterson, R.A.; Townsend, C.R.; Poulin, R.; Tompkins, D.M. Parasite spillback: A neglected concept in invasion ecology? Ecology 2009, 90, 2047–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, N.; Roznik, E.A.; Surbaugh, K.L.; Cano, N.; Price, W.; Campbell, T.; Rohr, J.R. Parasite spillover to native hosts from more tolerant, supershedding invasive hosts: Implications for management. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 59, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedknegt, M.A.; Havermans, J.; Waser, A.M.; Luttikhuizen, P.C.; Vellila, E.; Camphuysen, K.C.J.; Vander Meer, J.; Thieltges, D.W. Cross-species comparison of parasite richness, prevalence, and intensity in a native compared to two invasive brachyuran crabs. Aquat. Invasions 2017, 12, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaither, M.R.; Aeby, G.; Vignon, M.; Meguro, Y.I.; Rigby, M.; Runyon, C.; Bowen, B.W. An invasive fish and the time-lagged spread of its parasite across the Hawaiian archipelago. PloS ONE 2013, 8, e56940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogiel, V.A.; Lutta, A.S. On the mortality of Acipenser nudiventris of the Aral Sea in 1936. J. Rybn. Choz. 1937, 12, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Barse, A.M.; McGuire, S.A.; Vinores, M.A.; Eierman, L.E.; Weeder, J.A. The swimbladder nematode Anguillicola crassus in American eels (Anguilla rostrata) from middle and upper regions of Chesapeake Bay. J. Parasitol. 2001, 87, 1366–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Køie, M. Swimbladder nematodes (Anguillicola spp.) and gill monogeneans (Pseudoactylogyrus spp.) parasitic on the European eel (Anguilla anguilla). ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1991, 47, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvach,Y. ; Skóra, K.E. Metazoan parasites of the invasive round goby Apollonia melanostoma (Neogobius melanostomus) (Pallas) (Gobiidae: Osteichthyes) in the Gulf of Gdansk, Baltic Sea, Poland: a comparison with the Black Sea. Parasitol. Res. 2007, 100, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasal, P.; Taraschewski, H.; Valade, P.; Grondin, H.; Wielgoss, S.; Moravec, F. Parasite communities in eels of the Island of Reunion (Indian Ocean): a lesson in parasite introduction. Parasitol. Res. 2008, 102, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Engel, W. A.; Dillon, W. A.; Zwerner, D.; Eldridge, D. Loxothylacus panopaei (Cirripedia, Sacculinidae) an introduced parasite on a xanthid crab in Chesapeake Bay, USA. Crustacean 1966, 10, 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers, E.M.; Simmonds, K.; Messick, G.A.; Sullivan, L.; Schott, E.J. PCR-based prevalence of a fatal reovirus of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus (Rathbun) along the northern Atlantic coast of the USA. J. Fish Dis. 2016, 39, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messick, G.A.; Sindermann, C.J. Synopsis of principal diseases of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus. NOAA Tech. Memo. 1992, Woods Hole.

- Kampouris, T.E.; Kouroupakis, E.; Batjakas, I.E. Morphometric relationships of the global invader Callinectes sapidus Rathbun,1896 (Decapoda, brachyura, portunidae) from Papapouli lagoon, NW Aegean Sea, Greece. with notes on its ecological preferences. Fishes 2020, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattos, A.; Papadopoulos, D.K.; Giantsis, I.A.; Stamelos, A.; Karagiannis, D. Histopathology and Phylogeny of the Dinoflagellate Hematodinium perezi and the Epibiotic Peritrich Ciliate Epistylis sp. Infecting the Blue Crab Callinectes sapidus in the Eastern Mediterranean. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentiford, G.D.; Shields, J.D. A review of the parasitic dinofagellates Hematodinium species and Hematodinium-like infections in marine crustaceans. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2005, 66, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, J.D. The impact of pathogens on exploited populations of decapod crustaceans. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2012, 110, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

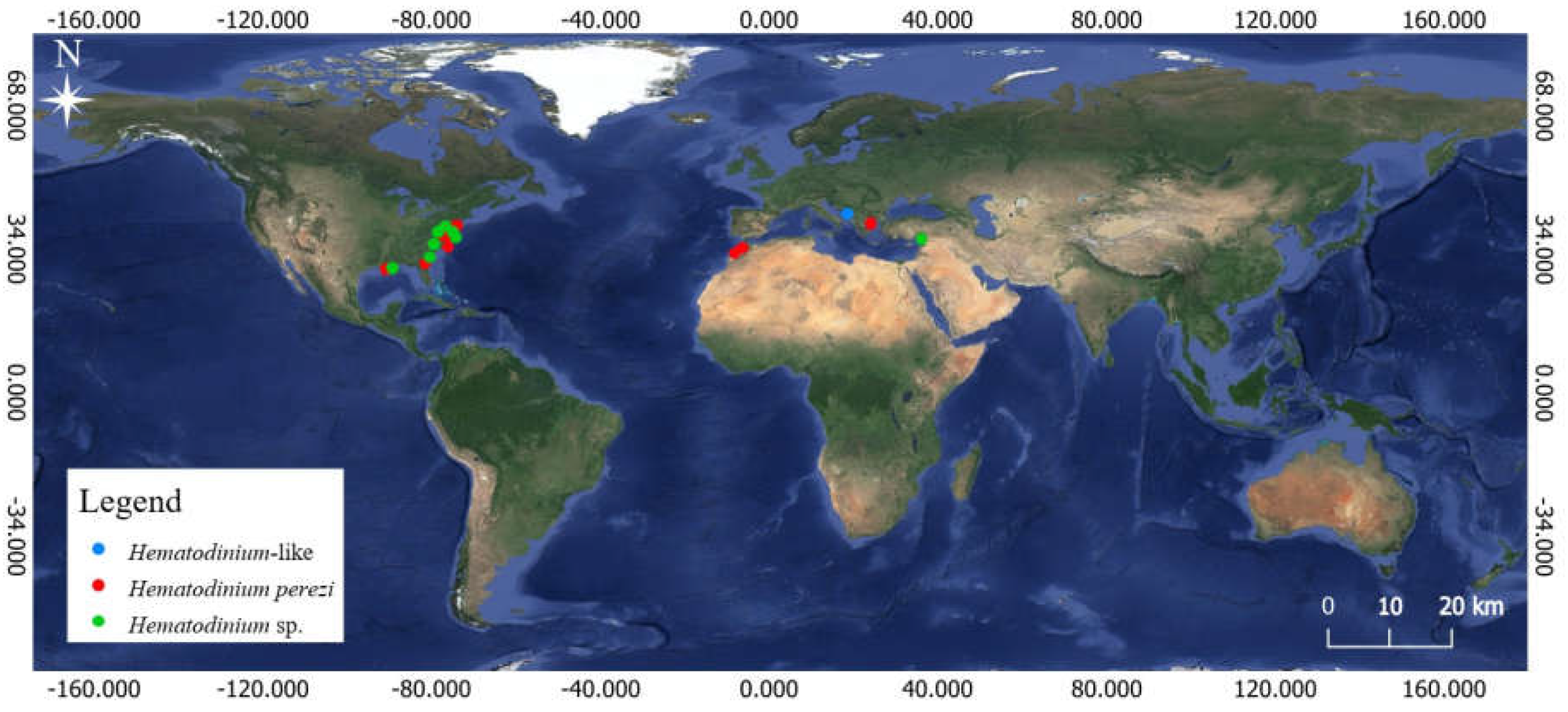

- Small, H.J. Advances in our understanding of the global diversity and distribution of Hematodinium spp. significant pathogens of commercially exploited crustaceans. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2012, 110, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, J.D.; Overstreet, R. Diseases, parasites, and others Symbionts. In The blue crab Callinectes sapidus; Kennedy, V., Cronin, L., Eds.; Maryland Sea Grant, College Park, Maryland. 2007,1, pp. 299−417.

- Field. R.; Appleton. P.; A Hematodinium-like dinoflagellate infection of the Norway lobster Nephrops norvegicus: observations on pathology and progression of infection. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1995, 22, 115–128.

- Taylor, A.; Field, R.; Parslow-Williams, P. The effects of Hematodinium sp.-infection on aspects of the respiratory physiology of the Norway lobster, Nephrops norvegicus (L.). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1996, 207, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, K.; Shields, J.D.; Taylor, D.M. Pathology of Hematodinium infections in snow crabs (Chionoecetes opilio) from Newfoundland. Canada. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2007, 95, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalat, A.; Collard, A.; Cadam, B.; Coates, C.J.; Fox, C.J. Physiological condition, short-term survival, and predator avoidance behavior of discraded Norway lobsters (Nephrops norvegicus). J. Shellfish Res. 2012, 35, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDAPM. Plan directeur des Aires protégées du Maroc. Les sites d’intérêt biologique et écologique de domaine littoral. BCEOM/SECA, BAD, EPHE, ISR, IB. 1996, 3, 166.

- Bououarour, O.; El Kamcha, R.; Boutoumit, S.; Pouzet, P.; Maanan, M.; Bazairi, H. Effects of the Zostera noltei meadows on benthic macrofauna in North Atlantic coastal ecosystems of Morocco: spatial and seasonal patterns. Biologia 2021, 76, 2263–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutoumit, S.; Bououarour, O.; El Kamcha, R.; Pouzet, P.; Zourarah, B.; Benhoussa, A.; Maanan, M.; Bazairi, H. Spatial patterns of macrozoobenthos assemblages in a sentinel coastal Lagoon: Biodiversity and environmental drivers. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, M. Dynamique des systèmes parasites-hôte, entre trématodes digènes et coque Cerastoderma edule: Comparaison de la lagune de Merja Zerga avec le bassin d'Arcachon. Doctoral dissertation. Université Bordeaux 1, 2008.

- Labbardi, H.; Ettahiri, O.; Lazar, S.; Massik, Z.; El Antri, S. Etude de la variation spatio-temporelle des paramètres physico-chimiques caractérisant la qualité des eaux d'une lagune côtière et ses zonations écologiques : cas de Moulay Bousselham, Maroc. C R Geoscience 2005, 337, 504–514. [Google Scholar]

- Maanan, M.; Landesman, C.; Maanan, M.; Zourarah, B.; Fattal, P.; Sahabi, M. Evaluation of the anthropogenic influx of metal and metalloid contaminants into the Moulay Bousselham lagoon, Morocco, using chemometric methods coupled to geographical information systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 4729–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmi, K.; Orbi, A.; Lakhdar Idrissi, J. Hydrodynamisme de la lagune de Oualidia (Maroc) durant l’été et l’automne 2005. Bull. Inst. Sci. Rabat Sect. Sci. Terre 2009, 31, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Makaoui, A.; Idrissi, M.; Agouzouk, A.; Larissi, J.; Baibai, T.; El Ouehabi, Z.; Laamal, M.A.; Bessa, I.; Ettahiri, O.; Hilmi, K. Etat océanographique de la lagune de Oualidia, Maroc (2011-2012). Eur. Sci. J. 2018, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohan, K.M.P.; Reece, K.S.; Miller, T.L.; Wheeler, K.N.; Small, H.J.; Shields, J.D. The role of alternate hosts in the ecology and life history of Hematodinium sp., a parasitic dinoflagellate of the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus). J. Parasitol. 2012, 98, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruebl, T.; Frischer, M.E.; Sheppard, M.; Neumann, M.A.; Maurer, A.N.; Lee, R.F. Development of an 18S rRNA gene-targeted PCR-based diagnostic for the blue crab parasite Hematodinium sp. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2002, 49, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, F.; Li, C. The parasitic dinoflagellate Hematodinium perezi infecting mudflat crabs, Helice tientsinensis, in polyculture system in China. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2019, 166, 107229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish,W. ; Miller,W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Small, H.J.; Shields, J.D.; Reece, K.S.; Bateman, K.; Stentiford, G.D. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Hematodinium perezi (Dinophyceae: Syndiniales), a Dinoflagellate Parasite of the Harbour Crab, Liocarcinus depurator. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2012, 59, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Miao, X.; Li, C.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Genetic variations of the parasitic dinoflagellate Hematodinium infecting cultured marine crustaceans in China. Protist 2016, 167, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, J.D. Infection and mortality studies with Hematodinium perezi in blue crabs. In: Proceedings of the Blue Crab Mortality Symposium; Guillory, V., Perry, H., VanderKooy, S., Eds.; Gulf States Mar. Fish. Comm, Ocean Springs. 2001; pp. 50–60.

- Newman, M.W.; Johnson, C.A. A disease of blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) caused by a parasitic dinofagellate Hematodinium Sp. J. Parasitol. 1975, 61, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messick, G.A.; Shields, J.D. Epizootiology of the parasitic dinofagellate Hematodinium sp. in the American blue crab Callinectes sapidus. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2000, 43, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, M.; Walker, A.; Frischer, M.E.; Lee, R.F. Histopathology and prevalence of the parasitic dinofagellate, Hematodinium sp, in crabs (Callinectes sapidus, Callinectes similis, Neopanopesayi, Libinia emarginata, Menippe mercenaria) from a Georgia estuary. J. Shellfsh Res. 2003, 22, 873–880. [Google Scholar]

- Frischer, M.; Lee, R.; Sheppard, M.; Mauer, A.; Rambow, F.; Neumann, M.; Broft, J.; Wizenmann, T.; Danforth, J. Evidence for a freeliving life stage of the blue crab parasitic dinofagelate Hematodinium sp. Harmful Algae 2006, 5, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H.J.; Shields, J.D.; Hudson, K.L.; Reece, K.S. Molecular detection of Hematodinium sp infecting the blue crab Callinectes sapidus. J. Shellfish Res. 2007, 26, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troedsson, C.; Lee, R.F.; Walters, T.; Stokes, V.; Brinkley. K.; Naegele, V.; Frischer, M.E. Detection and discovery of crustacean parasites in blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) by using 18S rRNA gene-targeted denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 4346–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, L.; Place, A.; Schott, E.; Jagus, R.; Messick, G.; Pitula, J. Real-time PCR-based assay for quantitative detection of Hematodinium sp. in the blue crab Callinectes sapidus. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2009, 84, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmenter, K.J.; Vigueira, P.A.; Morlok, C.K.; Micklewright, J.A.; Smith, K.M.; Paul, K.S.; Childress, M.J. Seasonal prevalence of Hematodinium sp. infections of blue crabs in three South Carolina (USA) rivers. Estuar. Coast 2013, 36, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldik, R.; Cengizler, İ. The investigation of bacteria, parasite and fungi in blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus, Rathbun 1896) caught from Akyatan Lagoon in east Mediterranean Sea. J. VetBio Sci. Tech. 2017, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chatton, E.; Poisson, R. Sur l’existence, dans le sang des crabs, de péridiniens parasites : Hematodinium perezi n. g., n.sp. (Syndinidae). C.R. Séances. Soc. Biol. Paris. 1931, 105, 553–557. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Huang, Q.; Lv, X.; Song, S.; Li, C. The parasitic dinolagellate Hematodinium infects multiple crustaceans in the polyculture systems of Shandong Province, China. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2021, 178, 107523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallien, L.; Sur la presence dans le sang de Platyonychus latipes Penn. d’un Peridinien parasite Hematodinium perezi Chatton et Poisson. Bull. Biol. Fr. Belg. 1938, 72, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean, S.A.; Ruddell, C.L. Three new crustacean hosts for the parasitic dinofagellate Hematodinium perezi (Dinofagellata: Syndinidae). J. Parasitol. 1978, 64, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messick, G.A. Hematodinium perezi infections in adult and juvenile blue crabs Callinectes sapidus from coastal bays of Maryland and Virginia, USA. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1994, 19, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, J.D.; Squyars, C.M. Mortality and hematology of blue crabs, Callinectes sapidus, experimentally infected with the parasitic dinofagellate Hematodinium perezi. Fish. Bull. 2000, 98, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Hanif, A.W.; Dyson, W.D.; Bowers, H.A.; Pitula, J.S.; Messick, G.A.; Jagus, R.; Schott, E.J. Variation in spatial and temporal incidence of the crustacean pathogen Hematodinium perezi in environmental samples from Atlantic Coastal Bays. Aquat. Biosyst. 2013, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.J.; Tiggelaar, J.M.; Shields, J.D. Effects of the parasitic dinofagellate Hematodinium perezi on blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) behavior and predation. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2014, 461, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lycett, K.A.; Chung, J.S.; Pitula, J.S. The relationship of blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) size class and molt stage to disease acquisition and intensity of Hematodinium perezi infections. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H.J.; Huchin-Mian, J.; Reece, K.; Lohan, K.P.; Butler, M.J.; Shields, J.D. Parasitic dinofagellate Hematodinium perezi prevalence in larval and juvenile blue crabs Callinectes sapidus from coastal bays of Virginia. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2019, 134, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Waser, A.M.; Li, C.; Thieltges, D.W. Lack of Hematodinium microscopic detection in crustaceans at the northern and southern ends of the Wadden Sea and an update of its distribution in Europe. Mar. Biol. 2024, 171, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimin, A.W.F.; Yusoff, N.A.H.; Kadriah, I.A.K.; Anshary, H.; Abdullah, F.; Jabir, N.; Hassan, M. Parasitic dinoflagellate Hematodinium in marine decapod crustaceans: a review on current knowledge and future perspectives. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, H.; Soares, A. M.; Pereira, E.; Freitas, R. Are the consequences of lithium in marine clams enhanced by climate change? Environ. Pollut. 2023, 326, 121416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, J.D., Sullivan, S.E.; Small, H.J. Overwintering of the parasitic dinoflagellate Hematodinium perezi in dredged blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) from Wachapreague Creek, Virginia. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 130, 124–132. [CrossRef]

- Morado, J.F.; Jensen, P.; Hauzer, L.; Lowe, V.; Califf, K.; Roberson, N.; shavey, C.; Woodby, D. Species identity and life history of Hematodinium, the causitive agent of bitter crab syndrome in north east pacific snow, Chionoecetes opilio, and tanner, C. bairdi, crabs. 2005. PROJECT 0306 FINAL REPORT. Anchorage, AK, USA: North Pacific Research Board.

- Shields, J.D. Collection techniques for the analyses of pathogens in crustaceans. J. Crus. Biol. 2017, 37, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.O. Molecular diagnosis of fish and shellfish diseases: present status and potential use in disease control. Aquaculture 2002, 206, 19–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.F.; Frischer, M.E. The decline of the blue crab. Am. Sci. 2004, 92, 548–553. [Google Scholar]

- Small, H.J.; Neil, D.M.; Taylor, A.C.; Atkinson, R.J.A.; Coombs, G.H. Molecular detection of Hematodinium spp. in Norway lobster Nephrops norvegicus and other crustaceans. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2006, 69, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.E.; Thomas, J.E.; Malkin, S.H.; Batista, F.M.; Rowley, A.F.; Coates, C.J. Hematodinium sp. infection does not drive collateral disease contraction in a crustacean host. Elife 2022, 11, e70356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lagoon | Sampling period | Number of individuals | W (g) | CW (cm) | CL (cm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min-Max | Mean ±SD | Min-Max | Mean ±SD | Min-Max | Mean ±SD | |||

| Merja Zerga | February 2023 | 20 | 4.6 - 237.5 | 88.9 ± 78.7 | 3.1 - 14.8 | 9.2 ± 4.1 | 2.2 - 6.6 | 4.6 ± 1.8 |

| Oualidia | March 2023 | 16 | 18.8 -207 | 57.0 ± 52.4 | 5.8 - 14.9 | 8.6 ± 2.6 | 3.1 - 7.4 | 4.5 ± 1.4 |

| GenBank accession number | Host | Locality | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| PP056127 | Callinectes sapidus (Portunidae) | Greece | [33] |

| EF065716 | Liocarcinus depurator (Polybiidae) | South Coast of England | [56] |

| EF065708 | Liocarcinus depurator | South Coast of England | [56] |

| EF065711 | Liocarcinus depurator | South Coast of England | [56] |

| KX244637 | Portunus trituberculatus (Portunidae) | China | [57] |

| KX244644 | Portunus trituberculatus | China | [57] |

| KX244641 | Portunus trituberculatus | China | [57] |

| KX244634 | Callinectes sapidus | USA | [57] |

| Merja Zerga | Oualidia | South Coast of England | China | USA | Greece | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Merja Zerga Lagoon | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Oualidia Lagoon | 0%-0.6% | - | - | - | - | - |

| South Coast of England EF065716, EF065708, EF065711 |

0.6%-1.3% | 0.6%-1.3% | - | - | - | - |

| China KX244637, KX244644, KX244641 |

1.7%-2.3% | 1.7%-2.3% | 1%-1.7% | - | - | - |

| USA KX244634 |

3.7%-4% | 3.7%-4% | 3.6%-4% | 3.7%-4% | - | - |

| Greece PP056127 |

0.6%-1.6% | 0.6%-1.6% | 0.3%-0.6% | 1.3%-1.7% | 3.4% | - |

| Lagoon | Groups | Total individuals | W (g) | CW (cm) | CL (cm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min-Max | Mean ±SD | Min-Max | Mean ±SD | Min-Max | Mean ±SD | |||

| Merja Zerga | male adult | 2 | 159.2 – 175.7 | 167.4 ± 11.6 | 11.7 – 12.1 | 11.9 ± 0.2 | 6.2 - 6.5 | 6.3 ± 0.2 |

| female adult | 5 | 109.9 - 153.1 | 131 ± 18.2 | 12.5 - 13.3 | 12.9 ± 0.3 | 5.8 - 6.3 | 6.1 ± 0.2 | |

| male juveniles | 1 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 2.2 | ||||

| female juveniles | 5 | 10.4 - 22.2 | 17.0 ± 5.0 | 4.3 - 6.4 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 2.6 - 3.2 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | |

| Oualidia | male adult | 1 | 70.1 | 9.7 | 5.0 | |||

| female adult | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| male juveniles | 2 | 21.6 - 30.5 | 25.8 ± 6.6 | 6.2 - 7.1 | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 3.3 - 3.7 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | |

| female juveniles | 1 | 18.7 | 6.1 | 3.1 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).