Submitted:

06 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stranding Data Collection, Necropsy and Tissue Sampling

2.2. Brucella Isolation and Identification

2.3. Molecular Methods

2.4. Whole Genome Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Brucella Infection Diagnosis and Brucella Isolates Characterization

3.2. Stranding Data and Necropsy Findings from B. ceti Positive Animals

3.3. Comparative genomic analysis and phylogenetic relationship of B. ceti isolates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foster G., Osterman B. S., Godfroid J., Jacques I., Cloeckaert A. Brucella ceti sp. Nov. and Brucella pinnipedialis sp. nov. for Brucella strains with cetaceans and seals as their preferred hosts. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 2688–2693. [CrossRef]

- Foster G., MacMillan A.P., Godfroid J., Howie F., Ross H.M., Cloeckaert A., Reid R. J., Brew S., Patterson I. A. A review of Brucella spp. infection of sea mammals with particular emphasis on isolates from Scotland. Vet. Microbiol. 2002, 90, 563–580. [CrossRef]

- Ewalt D.R., Payeur J. B., Martin B. M., Cummins D.R., Miller G. M. Characteristics of a Brucella species from a bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncates). J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1994, 6, 448–452. [CrossRef]

- Isidoro-Ayza, M. , Ruiz-Villalobos, N., Pérez, L., Guzmán-Verri, C., Muñoz, P.M., Alegre, F., Barberán, M., Chacón-Díaz, C., Chaves-Olarte, E., González-Barrientos, R., Moreno, E., Blasco, J.M., Domingo, M. Brucella ceti infection in dolphins from the Western Mediterranean sea. BMC Vet. Res, 2014; 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofolo, G., Petrella, A., Lucifora, G., Di Francesco, G., Di Guardo, G., Pautasso, A., Iulini, B., Varello, K., Giorda, F., Goria, M., et al. Occurrence of Brucella ceti in Striped Dolphins from Italian Seas. PloS ONE 15, 2020, e0240178.

- Guzmán-Verri, C. , González-Barrientos, R., Hernández-Mora, G., Morales, J.Á., Baquero-Calvo, E., Chaves-Olarte, E., Moreno, E. Brucella ceti and brucellosis in cetaceans. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nymo, I.H., Tryland, M., Godfroid, J. A Review of Brucella Infection in Marine Mammals, with Special Emphasis on Brucella pinnipedialis in the Hooded Seal (Cystophora cristata). Vet. Res. 2011, 42, 93.

- Whatmore, A.M., Dawson, C., Muchowski, J., Perrett, L.L., Stubberfield, E., Koylass, M., Foster, G., Davison, N.J., Quance, C., Sidor, I.F., et al. Characterisation of North American Brucella Isolates from Marine Mammals. PloS ONE, 2017, 12, e0184758.

- Grattarola, C. , Petrella, A., Lucifora, G., Di Francesco, G., Di Nocera, F., Pintore, A., Cocumelli, C., Terracciano, G., Battisti, A., Di Renzo, L., et al. Brucella ceti Infection in Striped Dolphins from Italian Seas: Associated Lesions and Epidemiological Data. Pathogens. [CrossRef]

- Grattarola, C., Pietroluongo, G., Belluscio, D., Berio, E., Canonico, C, Centelleghe, C., Cocumelli, C., Crotti, S., Denurra, D., Di Donato, A., et al. Pathogen Prevalence in Cetaceans Stranded along the Italian Coastline between 2015 and 2020. Pathogens. 2024, 13, 762. [CrossRef]

- Alba, P., Terracciano, G., Franco, A., Lorenzetti, S., Cocumelli, C., Fichi, G., Eleni, C., Zygmunt, M.S., Cloeckaert, A., Battisti, A. The presence of Brucella ceti ST26 in a striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba) with meningoencephalitis from the Mediterranean Sea. Vet Microbiol. 2013 May 31;164(1-2):158-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isidoro-Ayza, M. , Ruiz-Villalobos, N., Pérez, L., Guzmán-Verri, C., Muñoz, P.M., Alegre, F., Barberán, M., Chacón-Díaz, C., Chaves-Olarte, E., González-Barrientos, R., Moreno, E., Blasco, J.M., Domingo, M. Brucella ceti, 2014; 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, T. , Akar, K. , Erdenlig, S., Murugaiyan, J., Sandalakis, V., Boukouvala, E., Psaroulaki, A., Melzer, F., Neubauer, H., Wareth, G. Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Brucellosis in European Terrestrial and Marine Wildlife Species and Its Regional Implications. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJsseldijk, L.L., Brownlow, A.C. & Mazzariol, S. Best practice on cetacean post mortem investigation and tissue sampling – Joint ACCOBAMS and ASCOBANS. document.https://www.ascobans.org/sites/default/files/document/ascobans_ac25_inf3.2_rev1_best-practice-cetacean-post-mortem-investigation.pdf [Accessed August 3, 2023].

- Farrell, I.D. The development of a new selective medium for the isolation of Brucella abortus from contaminated sources. Res Vet Sci, 1974, 16:280–286.

- De Miguel, M.J., Marín, C.M., Muñoz, P.M., Dieste, L., Grilló, M.J., Blasco, J.M. Development of a selective culture medium for primary isolation of the main Brucella species. J Clin Microbiol, 2011, 49:1458–1463.

- World Organization for Animal Health. Brucellosis (infection with <i>B. abortus, B. World Organization for Animal Health. Brucellosis (infection with B. abortus, B. melitensis and B. suis). OIE Terrestrial Manual 2022.

- Bounaadja, L., Albert, D., Chénais, B., Hénault, S., Zygmunt, M.S., Poliak, S., Garin-Bastuji , B. Real-time PCR for identification of Brucella spp.: a comparative study of IS711, bcsp31 and per target genes. Vet Microbiol. 2009, 28;137(1-2):156-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.C. , Corrêa de Sá, M.I., Dias, R. and Tenreiro, R. MLVA-16 typing of Brucella suis biovar 2 strains circulating in Europe. Vet Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- López-Goñi, I. , García-Yoldi, D., Marín, C.M., de Miguel, M.J., Barquero-Calvo, E., Guzmán-Verri, C., Albert, D., Garin-Bastuji, B. New Bruce-ladder multiplex PCR assay for the biovar typing of Brucella suis and the discrimination of Brucella suis and Brucella canis. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 154, 152–155.

- Molina-Mora, J. A. , Campos-Sánchez, R., Rodríguez, C., Shi, L., & García, F. High quality 3C de novo assembly and annotation of a multidrug resistant ST-111 Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome: Benchmark of hybrid and non-hybrid assemblers. Scientific reports, 2020; 10, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z. , Wu, J., Chen, H., Draz, M. S., Xu, J., & He, F. Hybrid Genome Assembly and Annotation of a Pandrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Strain Using Nanopore and Illumina Sequencing. Infection and drug resistance, 2020; 13, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A., Hasman, H. PlasmidFinder and In Silico pMLST: Identification and Typing of Plasmid Replicons in Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS). In: de la Cruz, F. (eds) Horizontal Gene Transfer. Methods in Molecular Biology, 2020, vol 2075. Humana, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Kille, B. , Nute, M.G., Huang, V., Kim, E., Phillippy, A.M., Treangen, T.J. Parsnp 2.0: Scalable Core-Genome Alignment for Massive Microbial Datasets. bioRxiv, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino S, Voldby Larsen M, Møller Aarestrup F, Lund O. PathogenFinder--distinguishing friend from foe using bacterial whole genome sequence data. PLoS One. 2013, 8(10):e77302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077302. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2013;8(12). doi:10.1371/annotation/b84e1af7-c127-45c3-be22-76abd977600f. PMID: 24204795; PMCID: PMC3810466.

- Chen, L. VFDB: a reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Research, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P. , Huynh, W., Chalil, R., Smith, K.W., Raphenya, A.R., Wlodarski, M.A., Edalatmand, A., Petkau, A., Syed, S.A., Tsang, K.K., et al. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakin, S.M. , Dean, C., Noyes, N.R., Dettenwanger, A., Ross, A.S., Doster, E., Rovira, P., Abdo, Z., Jones, K.L., Ruiz, J., Belk, K.E., Morley, P.S., Boucher, C. MEGARes: an antimicrobial resistance database for high throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M. V. , Cosentino, S., Lukjancenko, O., Saputra, D., Rasmussen, S., Hasman, H., Sicheritz -Pontén, T., Aarestrup, F. M., Ussery, D. W., & Lund, O. Benchmarking of Methods for Genomic Taxonomy. J Cli Microbiol, 2014, 52(5), 1529–1539. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.V. , Cosentino, S., Rasmussen, S., Friis, C., Hasman, H., Marvig, R.L., Jelsbak, L., Sicheritz-Pontén, T., Ussery, D.W., Aarestrup, F.M., Lund, O. Multilocus Sequence Typing of Total-Genome-Sequenced Bacteria. J Cli Microbiol, 2012; 50, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florensa, A.F. , Kaas, R.S., Clausen, P.T.L.C., Aytan-Aktug, D., Aarestrup, F.M. ResFinder - an open online resource for identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in next-generation sequencing data and prediction of phenotypes from genotypes. Microb Genom, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maquart, M. , Le Flèche, P., Foster, G. et al. MLVA-16 typing of 295 marine mammal Brucella isolates from different animal and geographic origins identifies 7 major groups within Brucella ceti and Brucella pinnipedialis. BMC Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- Koren, S. , Walenz, B.P., Berlin, K., Miller, J.R., Bergman, N.H., Phillippy, A.M. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res, 2017; 27, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann T, A. (n.d.). Abricate. https://github.com/tseemann/abricate.

- Suárez-Esquivel, M. , Baker, K.S., Ruiz-Villalobos, N., Hernández-Mora, G., Barquero-Calvo, E., González-Barrientos, R., Castillo-Zeledón, A., Jiménez-Rojas, C., Chacón-Díaz, C., Cloeckaert, A., et al. Brucella Genetic Variability in Wildlife Marine Mammals Populations Relates to Host Preference and Ocean Distribution. Genome Biol. Evol, 2017; 9, 1901–1912. [Google Scholar]

- Girault, G. , Freddi, L., Jay, M., Perrot, L., Dremeau, A., Drapeau, A., Delannoy, S., Fach, P., Ferreira Vicente, A., Mick, V., Ponsart, C., Djokic, V. Combination of in silico and molecular techniques for discrimination and virulence characterization of marine Brucella ceti and Brucella pinnipedialis. Front Microbiol, 2024; 15, 1437408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

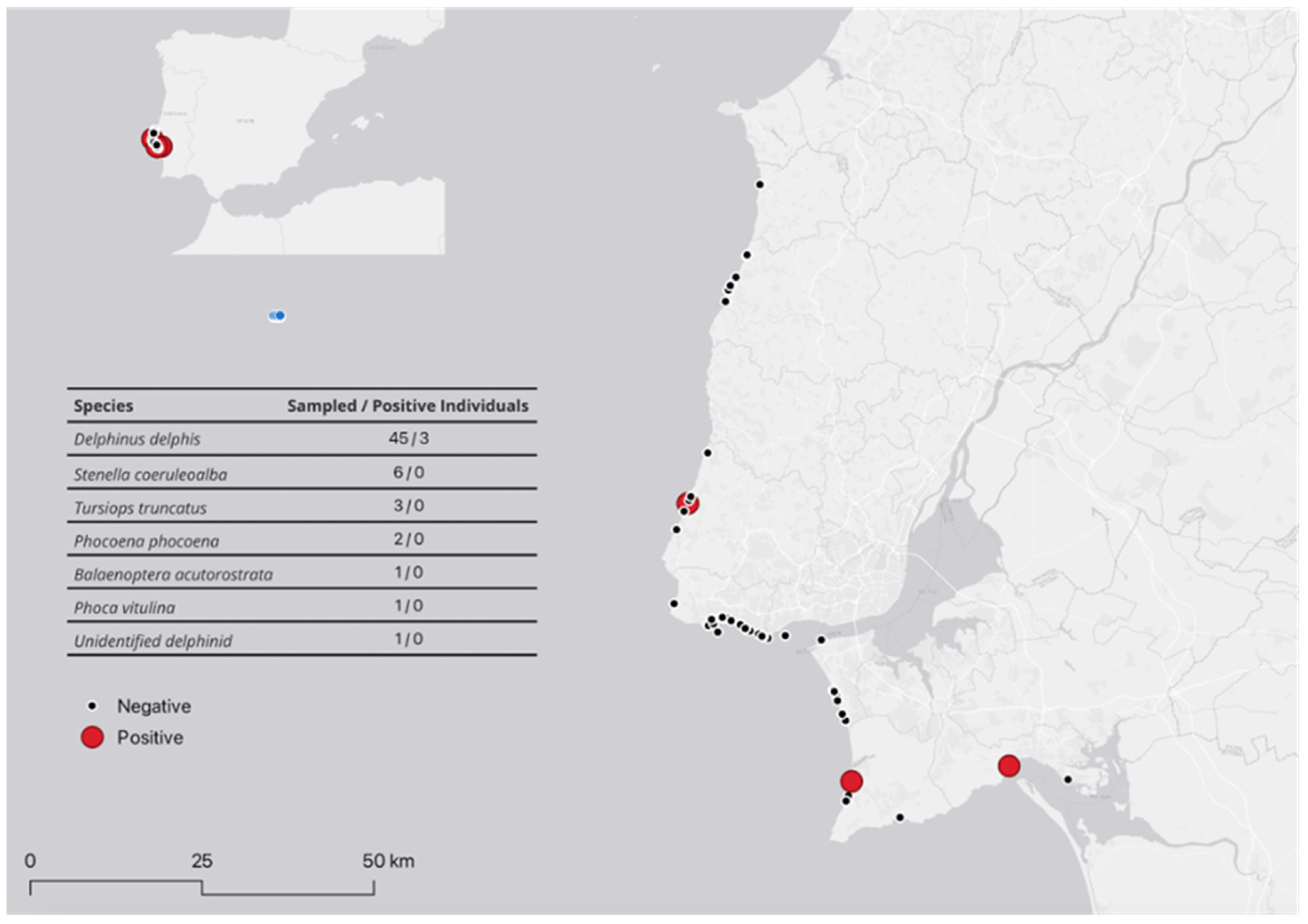

| Animal Identification1 | Sex/Age2 | Status3 | Region | Year of stranding | qPCR positive samples 4 | Bacteriological suspected samples | Brucella characterization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDE001 | F/J | 2 | Sintra | 2022 | B,L,Lg,LN,S | B,L,Lg,S | B. ceti |

| DDE002 | M/J | 2 | Setúbal | 2023 | B,L,Lg,LN,S | L,Lg,LN,S | B. ceti |

| DDE003 | F/A | 1 | Sesimbra | 2023 | B,C | B,L,Lg,LN,S | B. ceti |

| DDE005 | F/A | 4 | Setúbal | 2022 | B,L,Lg,S | N | N |

| DDE008 | M/A | 2 | Sesimbra | 2022 | B,L,Lg,S | N | N |

| DDE013 | M/J | 2 | Cascais | 2022 | LN | N | N |

| SCO016 | M/A | 2 | Almada | 2023 | B | N | N |

| DDE027 | M/J | 2 | Cascais | 2023 | B,L,Lg,LN,S,T | N | N |

| DDE033 | F/A | 1 | Cascais | 2023 | LN | N | N |

| PVI035 | M/J | 4 | Cascais | 2023 | T | N | N |

| DDE036 | M/A | 4 | Cascais | 2023 | LN | N | N |

| DDE037 | F/A | 4 | Cascais | 2023 | LN | N | N |

| DDE040 | M/J | 2 | Cascais | 2023 | B | B | Inconclusive |

| DDE043 | M/J | 2 | Cascais | 2023 | PS | N | N |

| B. ceti isolates | DDE001 | DDE002 | DDE003 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. ceti strains M13/05/1 alignment | 3077 SNVs, 279 insertions, 257 deletions |

2956 SNVs, 248 insertions, 241 deletions |

2478 SNVs, 212 insertions, 215 deletions |

|

| B. ceti strain M644/93/1 alignment | 5855 SNVs, 505 insertions, 562 deletions |

4996 SNVs, 439 insertions 457 deletions |

4997 SNVs, 439 insertions, 464 deletions |

|

| Virulence genes | bspE, vceA, btpB, manAoAg, wbkC, virB7, lpxA, lpxK, manCcore | |||

| Antibiotic resistance genes | mprF, bepC and D, E, F, G | |||

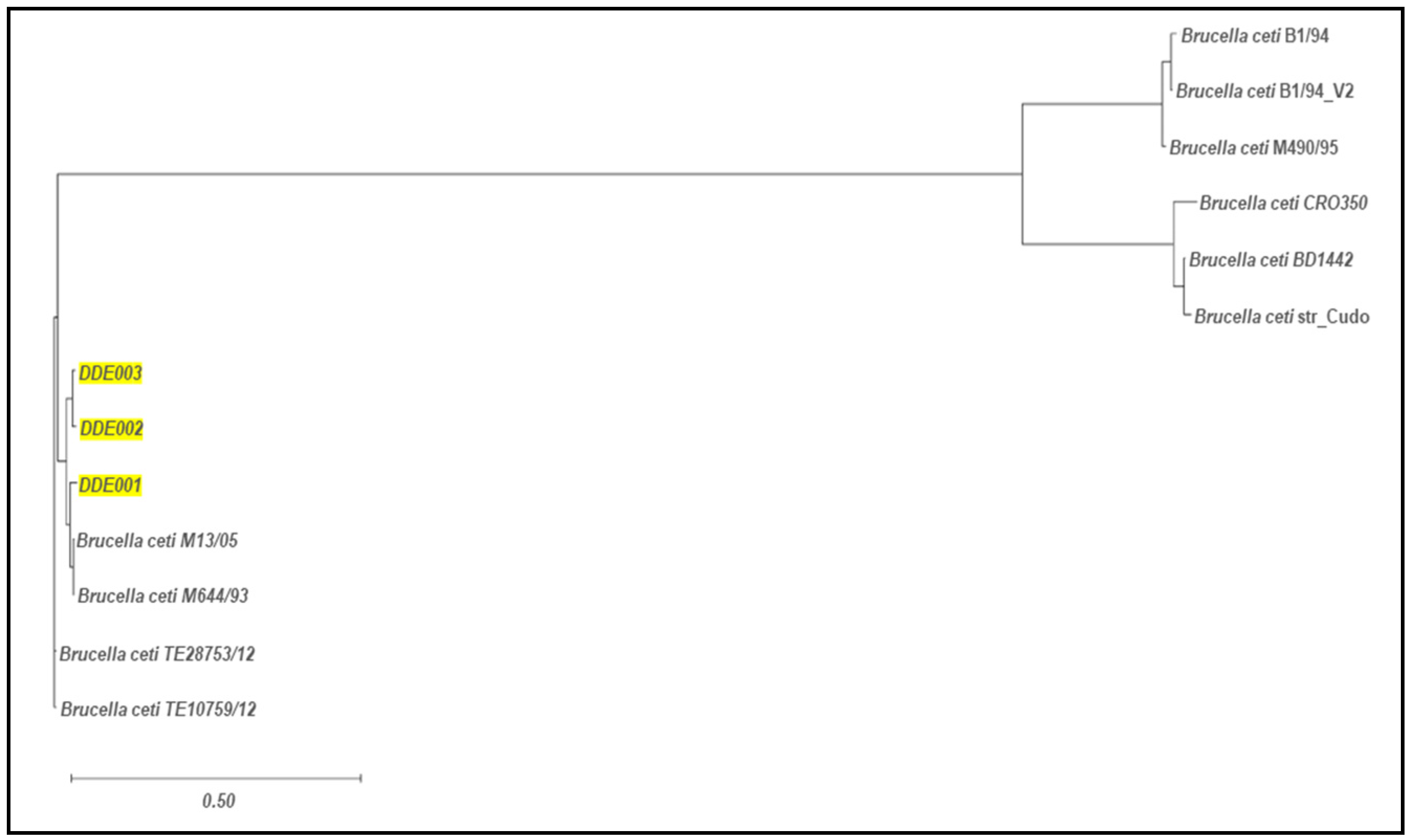

| MLST 1 | ST-49 | ST-26 | ||

| cgMLST 2 | cgST-392 | cgST-340 | ||

| MLVA 3 | Cluster A1 | Cluster A2 | ||

| B. ceti isolates | DDE001 | DDE002 | DDE003 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDE001 | --------------------------------------- | 213 SNVs, 12 insertions, 18 deletions | 216 SNVs, 16 insertions, 20 deletions |

| DDE002 | 213 SNVs, 12 insertions, 18 deletions | ------------------------------------ | 107 SNVs, 13 insertions, 11 deletions |

| DDE003 | 216 SNVs, 16 insertions, 20 deletions | 107 SNVs, 13 insertions, 11 deletions | -------------------------- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).