1. Introduction

Cyclotorsion is a compensatory ocular movement during head tilt, the purpose of which is aligning the eyeball to the visual reference and minimizing visual roll [

1]. The change of gravitational vector also induces cyclotorsion response via vestibulo-ocular response (VOR) [

2]. The previous studies regarding cyclotorsion have all been performed with subjects voluntarily tilting their heads on the solid earth [

1,

3,

4,

5].

Recently, researchers in the field of aerospace medicine found a compensatory head movement during body tilt and named it optokinetic cervical reflex (OKCR) [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. During aircraft tilt, the body and environment tilting induces compensatory head tilting [

6]. During OKCR, compensatory ocular cyclotorsion is expected to occur because of the visual and vestibular tilting stimuli. However, it is not known how a man will respond with ocular cyclotorsion in combination with head movement during body tilt.

During voluntary head tilt, responsive cyclotorsion develops composed of biphasic ocular movement: compensatory counterrolling and anticompensatory saccade [

1,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The situation of body tilt is completely different from that of voluntary head tilt; one can use head tilt in addition to ocular cyclotorsion in response to body tilt [

6]. Whereas head movement is a voluntary movement, ocular cyclotorsion is a reflexive movement (VOR) [

1,

17]. Therefore, the combination of ocular cyclotorsion and head tilt during body tilt is a complex response composed of voluntary and reflexive movements. It is not easy to predict the dynamic nature of ocular cyclotorsion in combination with compensatory head tilt during body tilt. Moreover, the effect of visual cue on ocular and head movement during body tilt has not been studied either. By analyzing ocular and head movement, it can be determined how a man perceives visual information during head tilt and body tilt. However, the experiment of tilting subject’s whole body needs very special equipment and can hardly be performed in usual laboratories.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the combined response of ocular cyclotorsion and head tilt during body tilt using a flight simulator and to interpret the physiologic role of those movements.

2. Methods

Subjects were three healthy male volunteers aged 20, 20, and 22 years respectively. They were flight trainees and participated in flight simulation programs in Aero Space Medical Center of ROK (Republic of Korea) Air Force. All the subjects underwent ophthalmologic examinations, including ocular alignment measurements with an alternate cover test in six diagnostic positions of gaze and the binocular vision test. Ophthalmologic examinations showed no abnormalities in all subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and all procedures regarding the subjects followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

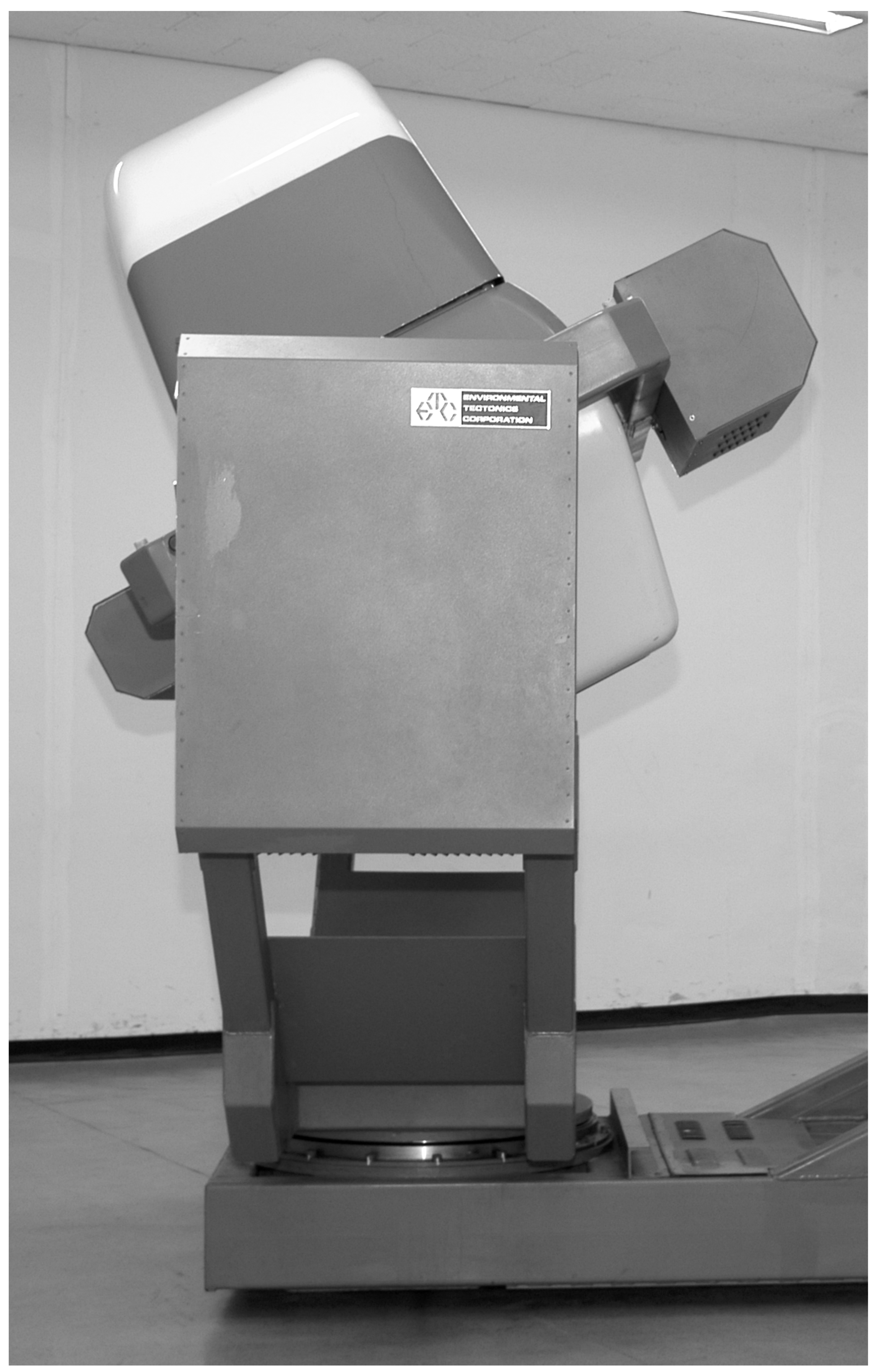

The experiments were performed using a constant-radius planetary flight simulator (GyroLab 2000, ETC, USA,

Figure 1A). The circuit radius of the flight simulator was 2.4 m. In the simulator, there was a front monitor 1m in front of the subject, which showed a simulated exterior view (a horizon) – visual cue. The field of view was 15 from the subject’s viewpoint. A video camera was placed 0.7 m in front of the subject, and a small light was placed in the upper right corner inside the simulator as viewed by the subject, and no outer lights could be seen from inside the cockpit. Due to the limitation in programming the simulator movements, the simulator rotated with a lowest speed of 1 rpm in a clockwise direction throughout the experiment, which induced a centrifugal force of 0.00268 G. This was too small to allow subjects to perceive a tilting sensation (equivalent to 0.115° tilting to left). The simulator was always tilted to the left and the rotation axis penetrates the pelvis of the subject.

The subjects were seated on the stiff pilot’s seat with their torsos fastened securely to the back of the seat with an X-shaped seat belt so that the amount of body tilt should be equal to that of simulator tilt. The head of the subject was not fixed to simulator and was allowed free movement. Since the head was not constrained, there might be head movement in the third dimension during the experiment, which could cause measurement errors. To minimize the errors, if we found head movement of flexion and extension during the experiment, we discarded the recorded data and repeated the experiment again.

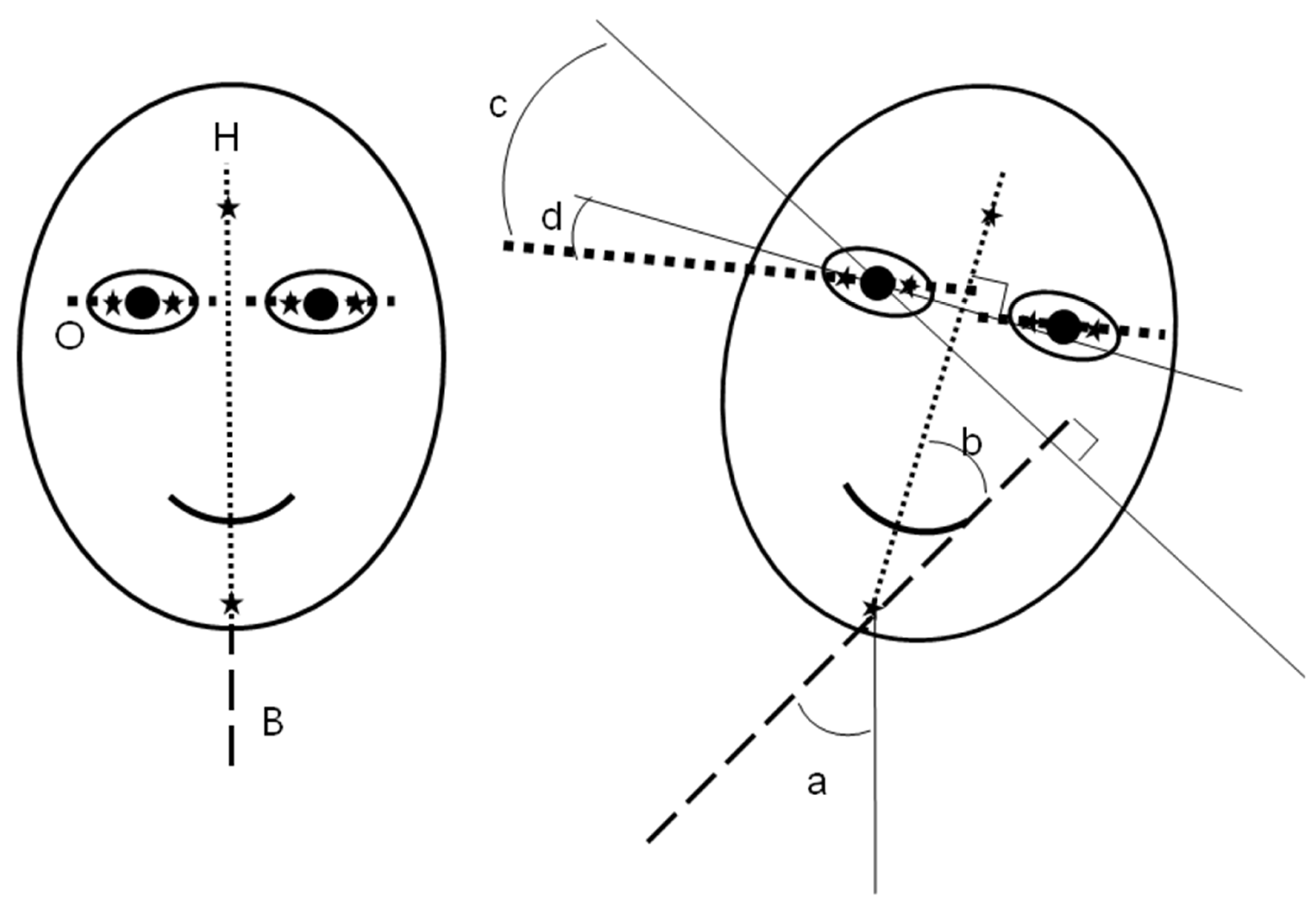

Markings were made on the subject’s forehead, chin, and ocular conjunctiva for the determination of the amount of head movement and ocular cyclotorsion (

Figure 1B). Markings on the temporal and nasal conjunctiva were made just proximal to the limbus of both eyes using a soft marking pen for ophthalmic surgery after instillation of topical ophthalmic anesthetics. The movements of the marked points in the frontal plane were recorded throughout the experiment with the digital video camera. The recorded digital movie data were transferred into digital still pictures at an interval of 100 milliseconds. The captured marked points were converted into numerical values of rectangular coordinates of x and y using the computer software developed by us. The coordinates were then transformed into the degree data of head tilt and ocular cyclotorsion using Excel program (Excel 2007 for Windows, Microsoft, USA). According to Herring’s law, the movement of the left eye could be assumed as the same as that of the right eye and we measured the cyclotorsion of only the right eye. As the simulator was always tilted to the left, head tilt to the right and excyclotorsion of the right eye were indicated as positive values and the opposite as negative.

The experiment was composed of five phases; a stationary pre-tilting phase, an active tilting phase, a stationary tilting phase, an active restoration phase, and a stationary after-tilting phase. Fifteen seconds after the stationary pre-tilting phase, the simulator tilted to the left over 5 seconds (an active tilting phase) and it maintained its tilting degree for 10 seconds (stationary tilting phase). After 5 seconds of returning to the original upright position (an active restoration phase) 15 seconds of stationary after-tilting phase continued, and then the experiment ended. The degree of tilt was in three modes of 30, 45, and 60° under two visually different conditions of with visual cue (VC) and without visual cue (noVC): 6 different modes in total for each subject. VC is a simulated condition in which the subjects are looking at the simulated horizon through the front monitor. Under noVC, the front monitor was turned off and there was no visual clue of tilting inside the simulator. By imposing the subjects into two visually different conditions, the effect of visual stimuli on ocular cyclotorsion and head tilt could be evaluated.

In the present study, “cyclotorsion” (angle c in

Figure 1B) was defined as an ocular cyclotorsional movement in reference to the head vertical axis (axis H) and “ocular tilting” (angle d) as ocular cyclotorsional movement in reference to the body axis (axis B).

3. Results

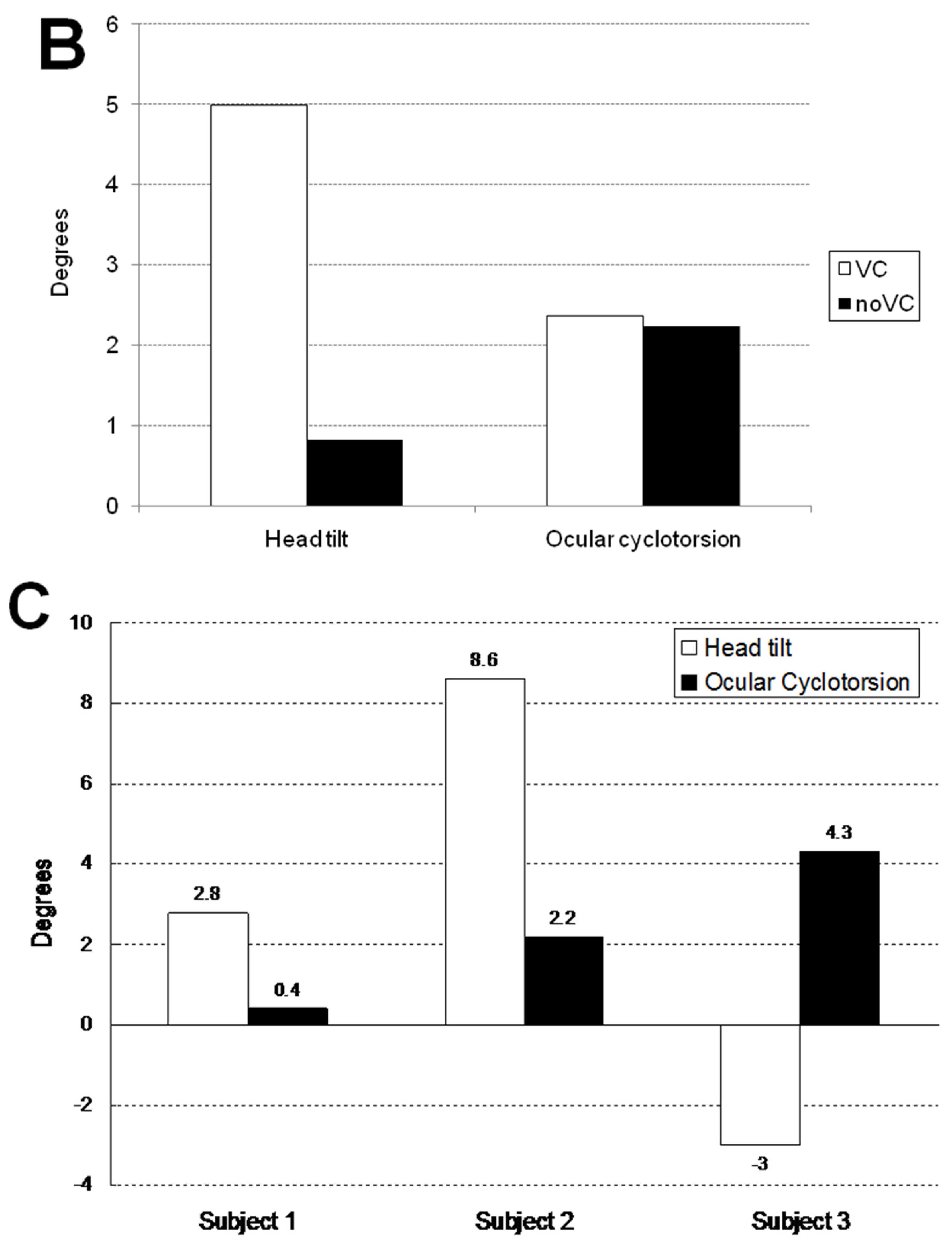

Eighteen obtained experiment results from 3 subjects are presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, and in Table 1.

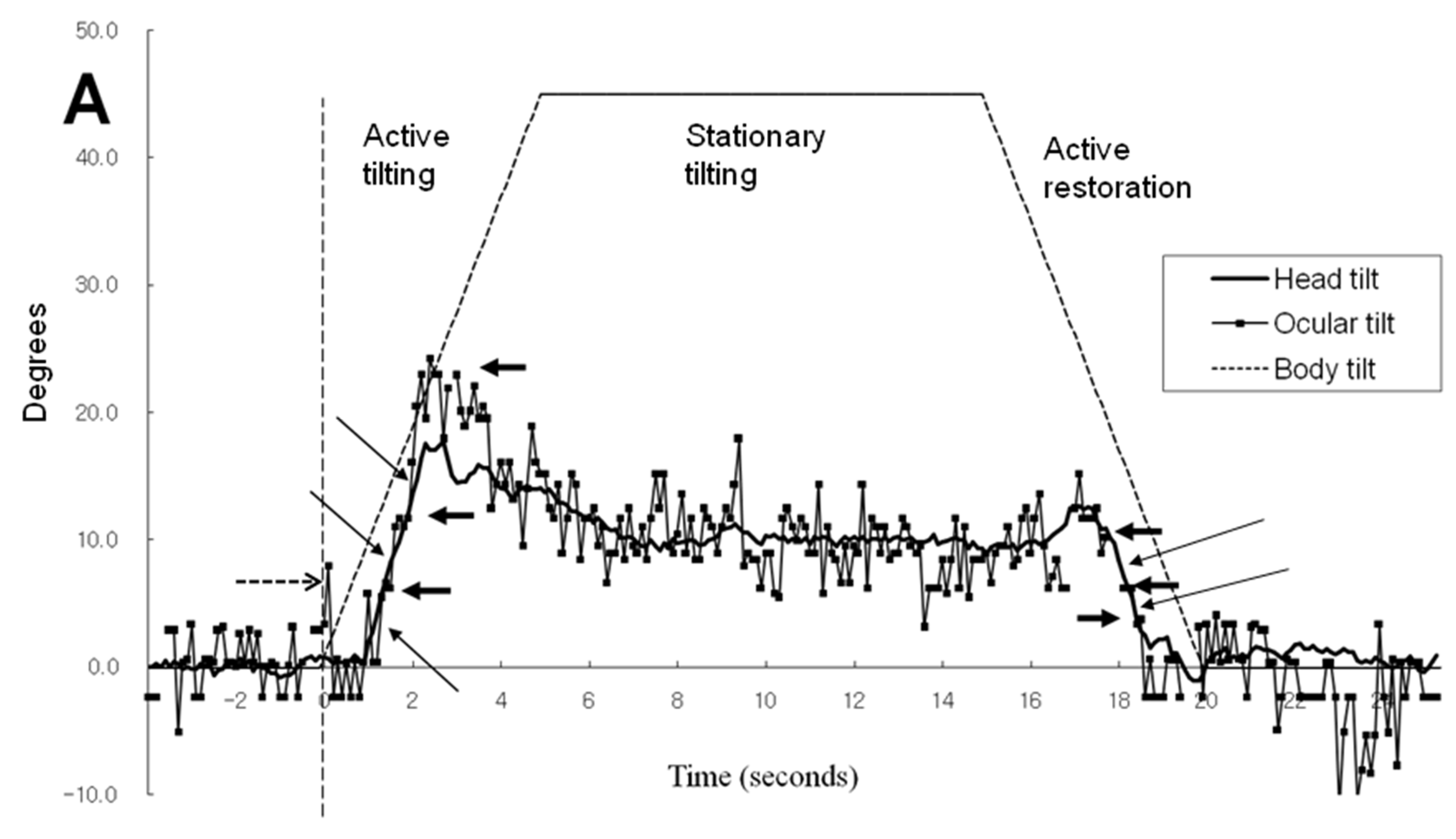

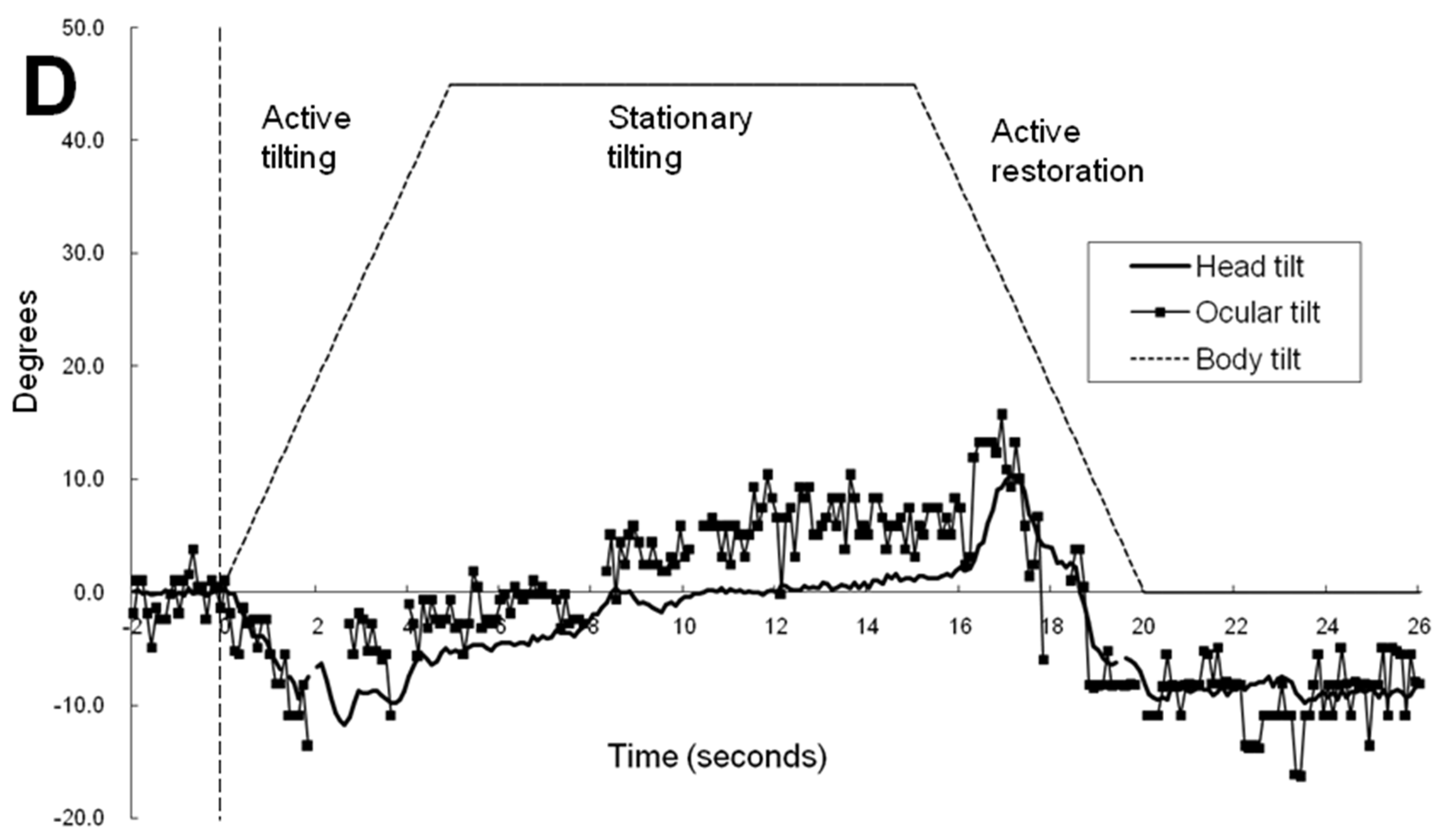

Figure 2A,B illustrates the time-sequence change of ocular tilt and cyclotorsion and head tilt when subject 1 was exposed to a 45° body tilt with visual cue. As a result of the video camera being tilted along with the simulator, the reference of ocular cyclotorsion and head tilt was the environment inside the simulator. In

Figure 2A, the head movement was of a smooth continuous movement while the ocular cyclotorsion showed movements with varying velocities consisting of fast and slow movements. As soon as the simulator and body of the subject tilted to the left, the right eye immediately made a fast compensatory excyclotorsion (a dashed line in

Figure 2A) while the head movement showed some latency. After a short period of fast excyclotorsion and incyclotorsion, the first rapid ocular excyclotorsion occurred when the difference between the axis of head and the simulator reached about 7.8°. Then slow incyclotorsion continued for about 0.3 seconds. Another fast excyclotorsion occurred to catch up with and even overpass the head tilt, followed by slow incyclotorsion. Then the right eye showed a third fast excyclotorsion and was followed by small multiple repeats of excyclotorsion and incyclotorsion. The slow incyclotorsion indicated with short arrows in

Figure 2A,B were compensating for the head tilt and minimized the ocular rotation (ocular tilt) in reference to the inside simulator environment. The angular velocity of the fast excyclotorsion indicated with long arrows in

Figure 2B was 44-54° per second, while the angular velocity of the body tilt was only 9° per second. These two different modes of cyclotorsion alternated to reach the maximum amount of ocular tilting, and then the amount of excyclotorsion gradually decreased. During the stationary tilting phase, the amount of ocular cyclotorsion decreased to a mean of -0.3°.

In

Figure 2C, without visual cue and in a 45° tilted condition, the mean amount of head tilt in the stationary tilting phase (3.3°) was smaller than that (10.0°) with visual cue (p<0.001 by t test, Table 1). The mean amount of ocular cyclotorsion in the stationary tilting phase was larger without visual cue (2.7° of excyclotorsion) than that (0.3° of incyclotorsion) with visual cue (p<0.001 by t-test). The stepladder pattern of ocular tilting can also be seen in the active tilting phase.

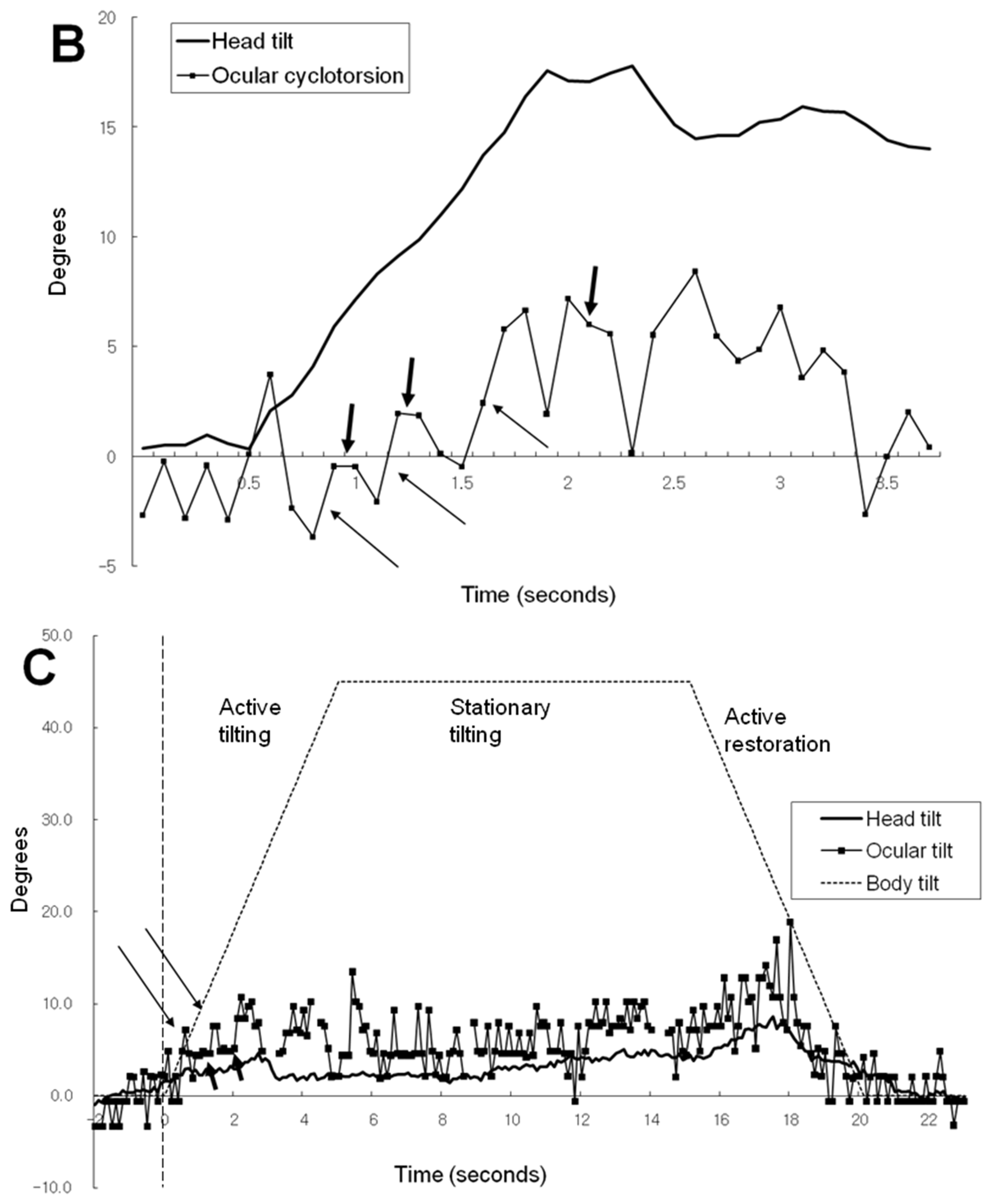

Figure 2D illustrates the ocular cyclotorsion and head tilt of subject 3 under VC in a 45° tilted condition. The subject 3 showed a distinct feature of response in that he showed a negative head tilt initially and showed a large positive peak of head tilt at the restoration phase. During the stationary tilting phase, subject 3 showed a larger degree of mean ocular cyclotorsion (4.3°) than subject 1 (0.4°) and subject 2 (2.2°). During the restoration phase, the right eye showed a multiple repeats of excyclotorsion and incyclotorsion in a stepladder pattern.

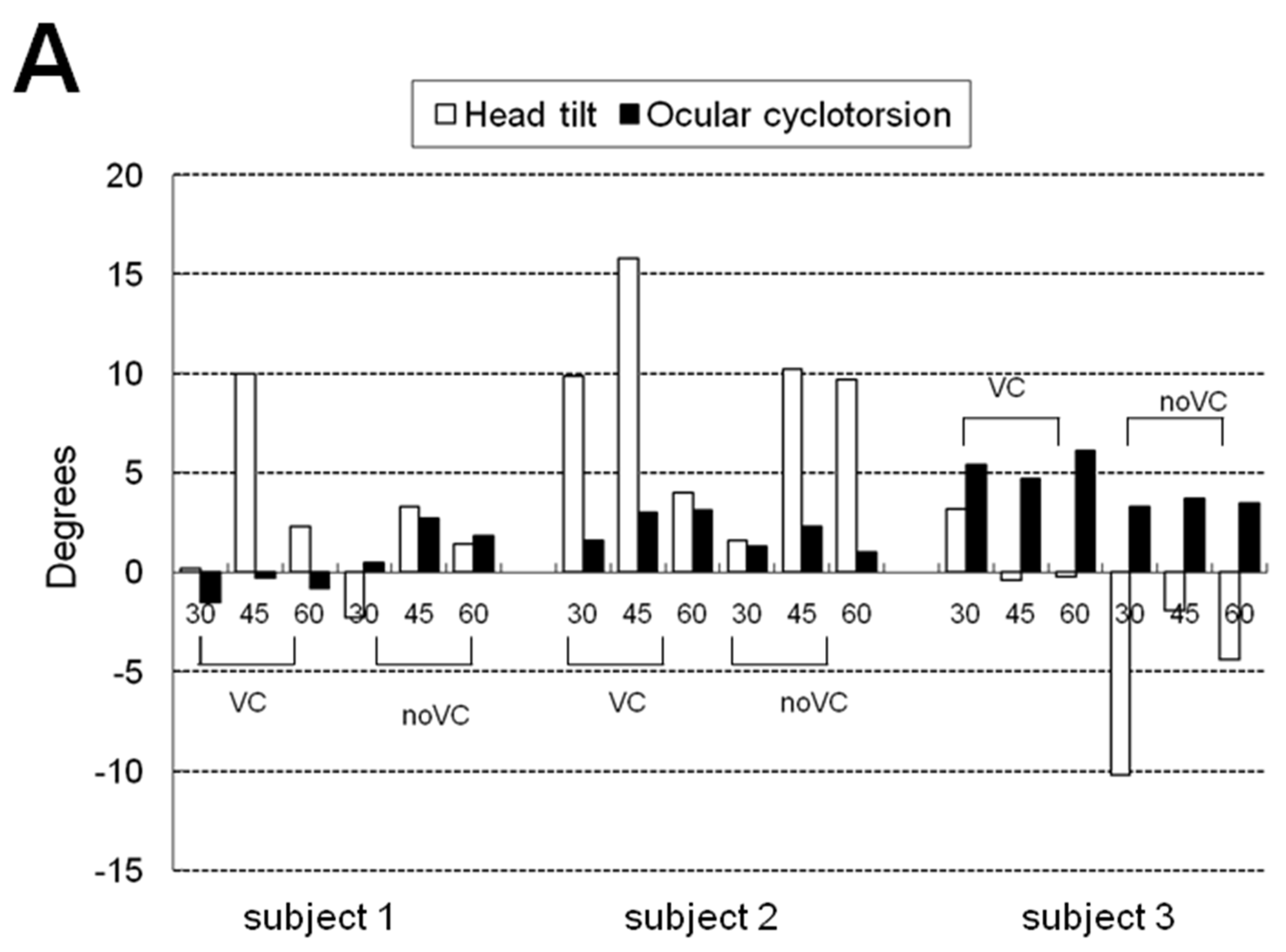

Table 1 and

Figure 3 show the mean and maximum degree of ocular cyclotorsion and mean amount of head tilt in the stationary tilting phase. The mean amount of ocular cyclotorsion showed no difference between the presence and absence of visual cue. The mean amount of head tilt was larger in VC than in noVC in all subjects except 60° in subject 2 (1 out of 9 comparisons). The maximum amount of ocular cyclotorsion observed during the experiments was 10.2±2.1°. The relationship between head tilt and ocular cyclotorsion is illustrated in

Figure 3C. Subject 3 showed larger degree of ocular cyclotorsion while showing smaller degree of head tilt than subject 1 and 2 (p<0.05 by t-test) except in a comparison with subject 1 in VC 30° (1 out of 12 comparisons).

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that, during body tilt, a combined response of head tilt and ocular cyclotorsion develops and it compromises the conflicting needs of binocular vision and gravitational orientation. Whereas ocular cyclotorsion is beneficial to maintaining the gravitational and visual orientation, a large amount of cyclotorsion deteriorates the binocular vision interfering with stereopsis and convergence [

1]. The head tilt, by reducing the amount of ocular cyclotorsion, can improve the binocular vision and the gravitational and visual orientation [

6,

7,

8]. To our knowledge, the combined movement of ocular cyclotorsion and head tilt during body tilt was not studied before.

In the active tilting phase of 45° with visual cue in

Figure 2A, the stepladder pattern ocular tilting induced by alternating ocular cyclotorsion is shown, which is similar to the cyclotorsional pattern induced by head tilt alone [

1,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The stimuli inducing ocular cyclotorsion are changes in gravitational vector and visual filed. Thus, VOR and optokinetic reflex (OKR) are the mechanism of ocular cyclotorsional response induced by body and head tilt. Noteworthy is the slope of the horizontal segments of incyclotorsion indicated with short arrows. It is parallel to the X axis of

Figure 2A indicating the inside simulator environment which occupied most of the peripheral visual field. It is not parallel to the dashed line indicating both the body tilt and the tilt of central visual field. Therefore, the purpose of stepladder pattern ocular cyclotorsional movements is to stabilize the peripheral visual roll induced by head tilt. Therefore, in the active tilting phase, the environment and body tilting are mainly compensated by head tilt and that the ocular cyclotorsion cancel out the rapid movement of peripheral visual field induced by head movement.

The excyclotorsion of the right eye during stationary body tilt to left could be explained by the following complicated mechanisms. First, the VOR in response to gravitational stimuli works positively to excyclotorsion as in response to head tilt alone [

1,

18]. Second, the effort to maintain the binocular vision works negatively to ocular cyclotorsion [

1]. Third, cervico-ocular reflex (COR) could be another negative factor for excyclotorsion. In the stationary tilting phase when the head axis (axis H in

Figure 1D) was in the tilted state against the vertical axis of the body (axis B in

Figure 1D), the COR induced by the somatosensory stimuli to the cervical vertebrae [

19] give the eyes a cyclotorsional signal in the opposite direction to the head tilt. In case of positive head tilt (subject 1 and 2), the cervico-ocular reflex causes negative effect to ocular excyclotorsion and in case of negative head tilt (subject 3), it causes positive effect. Although most of the past studies on COR dealt with body rotations about a vertical axis [

19,

20,

21], our results is an evidence of COR in the frontal plane like VOR and OKR [

1,

17,

18,

22].

Subject 3 showed relatively larger degrees of excyclotorsion than subject 1 and 2 (

Figure 2D and 3 and Table 1). This suggests that, in case of inadequate head compensation for the body tilt, the ocular compensation may work more in spite of some decrease in binocular vision. In individuals who usually respond to the body tilt with minimal head movement like subject 3, the large amount of cyclotorsion can be an adapted response. Although subject 3 showed negative head tilting, he made a compensatory contraction of neck muscles but it was not strong enough to resist his head weight, which could be inferred from a large peak of head tilt in the restoration phase. It can be thought that the head movement to body tilting is subject to individual variation such as neck muscle contractility. As the ocular cyclotorsion is a kind of involuntary reflexive movement and has little room for individual variation, the response of ocular cyclotorsion during body tilt depends largely on the subject’s ability to tilt his head. Therefore, the quality of binocular vision during body tilt can be also different among subjects depending on their ability of head tilt in response to body tilt.

In the stationary tilting phase, the amount of head tilt with visual cue was generally larger than without it while the amount of ocular cyclotorsion was similar between the two conditions. (

Figure 3B) The visual cue of body tilt through central visual field induced larger amount of head tilt, but affected little to ocular cyclotorsion. The visual clue gave brain additive information of body tilt and induced larger amount of head tilt [

10]. The absence of difference in ocular cyclotorsion between the two visually different conditions was possibly from the necessity for preservation of binocular vision. The small view field (15°) of front monitor could be another cause. From this fact, it can be assumed that the central visual field mainly induces the compensatory tilting response via head tilting and that the peripheral visual field does via ocular cyclotorsion.

During each experiment, we could observe that there was a maximum limit in the amount of cyclotorsion. The maximum amount of cyclotorsion could be observed mainly during the active tilting phase with an average value of 10.2 ± 2.1°. It was noteworthy that the maximum amounts of cyclotorsion were relatively uniform among subjects in different conditions. This result implies that the maximum amount of cyclotorsion in physiologic state is about 10°. There have been controversies about the amount of cyclotorsion during head tilt among researchers. Most investigators reported that the amount of cyclotorsion was partially compensatory to the degree of head tilt such as 10% to 30 % of head tilt [

1,

3,

4,

5,

12,

13,

14,

23,

24,

25]. Kushner reported during 40° of head tilt, about 10° of compensatory cyclotorsion developed [

1,

13,

14]. These results of prior studies can be explained by our result; the amount of cyclotorsion can be varied among situations but has a maximum limit of about 10° in the physiologic state.

Prior studies[

26,

27] showed that head movements accounted for most of the field of fixation in the horizontal roll plane. Other studies [

28,

29] regarding reading behavior also showed ocular rotations did not exceed 6° to 8° to either side (a maximum of 12°) and eye movements, in general, preceded head movements. Although the axis of ocular rotation is different from that of our study, those results correspond well to our results in many aspects.

The limitation of our study was that we used manual videographic analysis on discontinuous still pictures of ocular movement. A more advanced measurement system using sclera search coils might have yielded more detailed information on ocular movement. Many spikes of ocular cyclotorsion which are seen in

Figure 2 might appear to be noise or measurement errors. However, we think the amounts of noise or measurement errors are smaller than 2.0-2.5° considering that the standard deviations of ocular tilting and cyclotorsion were 2.0-2.5° in the stationary tilting phase (Table 1). Therefore, the multiple saccades exceeding 2.5°, especially during active tilting and restoration phase, should be regarded as real ocular movements rather than noise or measurement errors.

5. Conclusions

Combined dynamic response of ocular cyclotorsion and head movement occur during body tilt with individual variation and the purpose of response is to meet the conflicting needs of binocular vision and maintenance of orientation. The ocular cyclotorsional response is mediated by interactions of VOR, OKCR, and COR.

6. Value Statement

What was known:

-

Cyclotorsion is a compensatory ocular movement during head tilt to align the eyeball to the visual reference and minimizing visual roll.

-

The change of gravitational vector also induces cyclotorsion response via vestibulo-ocular response (VOR).

-

During a compensatory head movement during body tilt, optokinetic cervical reflex (OKCR), compensatory ocular cyclotorsion is expected to occur because of the visual and vestibular tilting stimuli.

-

It is not known how a man will respond with ocular cyclotorsion in combination with head movement during body tilt.

What this paper adds:

-

Combined dynamic response of ocular cyclotorsion and head movement occur during body tilt with individual variation and the purpose of response is to meet the conflicting needs of binocular vision and maintenance of orientation.

-

The ocular cyclotorsional response is mediated by interactions of VOR, OKCR, and cervico-ocular reflex.

Author Contributions

S.J.W., H.K.Y, S-H.H., and K.Y.C. performed the experiment. S.B.H. and J-M.H. made the study design, supervised the study and revised the manuscript. All of the authors extracted and analyzed the data, interpreted the results, made figures, and wrote the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by a grant from the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A080299).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study adhered to the relevant tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and approval was obtained from the institutional review board of Aero Space Medical Center of ROK Air Force.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any financial or proprietary interest in the materials or methods.

References

- Kushner, B.J. Ocular torsion: Rotations around the “Why” Axis. J AAPOS. 2004, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Dieterich, M. Pathological eye-head coordination in roll: Tonic ocular tilt reaction in mesencephalic and medullary lesions. Brain. 1987, 110, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.F. , 2nd. Counterrolling of the human eyes produced by head tilt with respect to gravity. Acta Otolaryngol. 1962, 54, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.F., 2nd; Graybiel, A. Effect of gravitoinertial force on ocular counterrolling. J. Appl. Physiol. 1971, 31, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linwong, M.; Herman, S.J. Cycloduction of the eyes with head tilt. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1971, 85, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merryman, R.F.; Cacioppo, A.J. The optokinetic cervical reflex in pilots of high-performance aircraft. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 1997, 68, 479–487. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, F.R.; Cacioppo, A.J.; Gallimore, J.J.; Hinman, G.E.; Nalepka, J.P. Aviation spatial orientation in relationship to head position and attitude interpretation. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 1997, 68, 463–71. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.R.; Cacioppo, A.J.; Hinman, G.E., Jr. Aviation spatial orientation in relationship to head position, altitude interpretation, and control. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 1997, 68, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite, M.G.; Beal, K.G.; Alvarez, E.A.; Jones, H.D.; Estrada, A. The optokinetic cervico reflex during simulated helicopter flight. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 1998, 69, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar]

- Gallimore, J.J.; Brannon, N.G.; Patterson, F.R.; Nalepka, J.P. Effects of fov and aircraft bank on pilot head movement and reversal errors during simulated flight. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 1999, 70, 1152–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Gallimore, J.J.; Patterson, F.R.; Brannon, N.G.; Nalepka, J.P. The opto-kinetic cervical reflex during formation flight. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2000, 71, 812–821. [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, A.P.; Zenkin, G.M. Torsional eye movements and constancy of the visual field. Vision Res. 1973, 13, 2465–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushner, B.J.; Kraft, S. Ocular torsional movements in normal humans. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1983, 95, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushner, B.J.; Kraft, S.E.; Vrabec, M. Ocular torsional movements in humans with normal and abnormal ocular motility--part i: Objective measurements. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmo.l Strabismus. 1984, 21, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collewijn, H.; Van der Steen, J.; Ferman, L.; Jansen, T.C. Human ocular counterroll: Assessment of static and dynamic properties from electromagnetic scleral coil recordings. Exp. Brain Res. 1985, 59, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferman, L.; Collewijn, H.; Van den Berg, A.V. A direct test of listing’s law--ii. Human ocular torsion measured under dynamic conditions. Vision Res. 1987, 27, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, M.; Gioanni, H. Role of the cervico-ocular reflex in the “Flying” Pigeon: Interactions with the optokinetic reflex. Vis. Neurosci. 2004, 21, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jampel, R.S. The myth of static ocular counter-rolling: The response of the eyes to head tilt. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 956, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.; Freedman, W. Cervico-ocular reflex in the normal adult. Acta Otolaryngol. 1980, 89, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, M.; Leopold, H.C.; Thoden, U. Vestibulo-ocular reflex (vor), cervico-ocular reflex (cor) and its interaction in active head movements. Arch. Psychiatr. Nervenkr. 1981, 230, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikosaka, O.; Maeda, M. Cervical effects on abducens motoneurons and their interaction with vestibulo-ocular reflex. Exp. Brain Res. 1973, 18, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, C.; Borel, L.; Magnan, J.; Lacour, M. Torsional optokinetic nystagmus after unilateral vestibular loss: Asymmetry and compensation. Brain. 2005, 128, 1511–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, R.S. Torsional eye movements. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1951, 34, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quereau, J.V. Some aspects of torsion. AMA. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1954, 51, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krejcova, H.; Highstein, S.; Cohen, B. Labyrinthine and extra-labyrinthine effects on ocular counter-rolling. Acta Otolaryngol. 1971, 72, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, F.P. Uber die verwendung von kopfbewegungen beim umhersehen. I and ⅱ. Mitteilung. Grafes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1925, 115, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudlock, F.A.; Shekhar, H.; Gottlob, I. Coordination of eye and head movements during reading. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 2991–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ciuffreda, K.J.; Selenow, A.; Ali, S.R. Dynamic interactions of eye and head movements when reading with single-vision and progressive lenses in a simulated computer-based environment. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 1534–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Eye and head coordination in reading: Roles of head movement and cognitive control. Vision Res. 1999, 39, 3761–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).