1. Introduction

Infections with bacteria resistant to commonly prescribed antibiotics represent a major public health crisis. In 2008, the Infectious Diseases Society of America designated a group of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, referred to by the acronym ESKAPE pathogens (

Enterococcus faecium,

Staphylococcus aureus,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Acinetobacter baumannii,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Enterobacter ), as especially problematic [

1]. The resistance mechanisms of these pathogens belong to three categories: 1. Acquisition and expression of genes encoding antibiotic-inactivating enzymes, 2. Mutations in the target of antibiotics, making them resistant, and 3. Presence and expression of pumps that expel the antibiotics from cells before they reach toxic levels [

2]. The opportunistic pathogen

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (the P in ESKAPE), in particular, is responsible for a number of acute nosocomial infections and chronic infections such as chronic wounds, urinary tract infections, bacteremia, endocarditis, nosocomial infections, and infections in the lungs of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients [

1,

2]. Furthermore, this organism is difficult to treat due to its high levels of resistance to most clinically useful antibiotics.

P. aeruginosa is best characterized for its resistance to conventional

β–lactam antibiotics, including penicillins, carbapenems, and cephalosporins [

3]. This is due to the ability of

P. aerugionosa to secrete

β–lactamase, an enzyme that hydrolyzes the

β–lactam ring of

β–lactam antibiotics, thereby inactivating the antibiotic [

2,

3,

4]. Regardless,

β–lactams are still considered desirable therapeutics by physicians due to their low cost and lack of toxicity even at high concentrations [

3]. One solution to renew the effectiveness of

β–lactam antibiotics is

β–lactamase inhibitors that are designed to inhibit serine

β–lactamases, thereby restoring the antimicrobial properties of

β–lactams [

4]. However, bacterial species are already beginning to acquire resistance to these inhibitors; avibactam is currently one of the only effective

Pseudomonas β–lactamase inhibitors when prescribed with ceftazidime, and it is already in decline [

5]. While the ceftazidime-avibactam (CAZ-AVI)

β–lactamase inhibitor combination maintains efficacy against

Enterobacteriaceae,

P. aeruginosa has already developed a resistance rate of up to 18% within the first five years of CAZ-AVI’s clinical use (resistance rate defined by the percentage of non-sensitive bacterial isolates) [

5]. This is likely due to

β–lactamase inhibitors’ inactivation mechanism; most

β–lactamase inhibitors exert activity through competitive occupancy of its active site. However, mutations on this enzyme have developed to where the inhibitor can no longer bind to the protein but its respective substrate still maintains these capabilities, rendering the inhibitor ineffective [

6]. Allosteric inhibition, on the other hand, induces a conformational change in the protein of interest, resulting in its complete loss of functionality; this property of allosteric inhibition makes it an ideal strategy for novel

β–lactamase inhibitors. Thus, it is clinically relevant to study the chemical structure and functionality of the

β–lactamase protein to identify new inhibitory sites for

β–lactamase inhibitors.

It is thought that the chromosomal

ampC gene in

Pseudomonas is responsible for the encoding of

β-lactamase, the main mechanism driving

β-lactam antibiotic resistance in

P. aeruginosa [

4]. However, the

ampC gene in

Pseudomonas has not been thoroughly investigated or confirmed for its expression of

β–lactamase. This is likely due to the difficulties involved in studying genes present on bacterial chromosomal DNA; antibiotic resistance genes found on plasmids or other mobile genetic elements can be easily transformed into a host bacterium and is more likely to be expressed. However, it is difficult to study

ampC because it is uncertain how this gene will be expressed when removed from its natural environment and cloned into a plasmid with a different and perhaps incompatible promoter system. For these reasons, the

ampC in

Pseudomonas has never been isolated or studied in a laboratory setting. Therefore, to study the

β-lactamase protein in

Pseudomonas, this experiment aimed to first isolate and clone

ampC of

P. aerugionsa into

E. coli. Furthermore, considering the inefficiency of current

β–lactam antibiotics, the long-term goal of this study was to perform random mutagenesis on

ampC to identify potential allosteric inhibitor sites on

β-lactamase for novel

β-lactamase inhibitors.

2. Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Media

Wild type Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were cultured in Luria-Bertani medium. Chromosomal P. aeruginosa PA01 DNA containing the gene of interest (ampC ) was prepared via phenol-chloroform extraction. pDN19 and pMMB67HE plasmid was purified from DH5α E. coli using a plasmid purification kit from Bio Basic (plasmids later utilized as host vectors for recombination of ampC). Recombinant plasmids were introduced in competent DH5α and BL21 E. coli cells then conjugated into ampC deficient strain of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (∆ampC); conjugation was facilitated by E. coli transformed with pRK2013 plasmid.

For antibiotic susceptibility testing, the following strains of P. aeruginosa were utilized: wild type PAO1 (laboratory strain used to generate ampC deletion), PAO1 ∆ampC, PA14, PA14 Tn-ampC (ampC gene disrupted through insertion of a transposon), PAO1 seq (original sequenced isolate of P. aeruginosa, and PAO1 seq Tn-ampC (ampC gene disrupted through insertion of a transposon, isogenic to PAO1 seq).

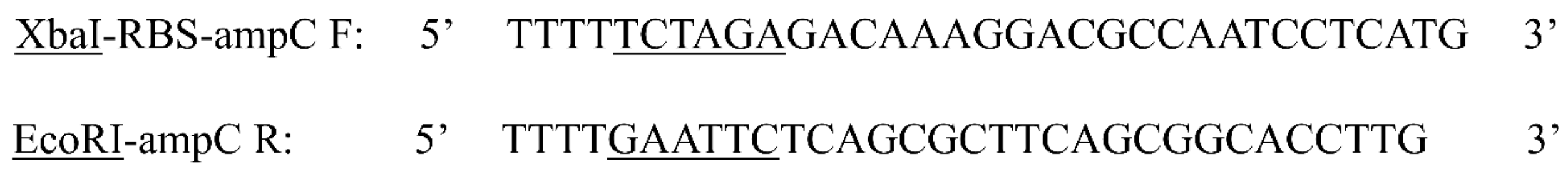

2.2. Cloning the ampC gene

Restriction enzymes EcoRI (forward) and XbaI (reverse) were utilized to amplify

ampC in

P. aeruginosa via PCR at an annealing temperature of 64°C and extension time of one minute and twenty seconds (

Appendix A).

PCR reactions were carried out using a high fidelity polymerase kit (Q5) Purchased from New England Bio Labs, and molecular size of the amplified ampC insert (1.2 kb) was confirmed using gel electrophoresis (GE) on 1% agarose gels. Ligation of ampC into pMMB67HE and pDN19 was performed using the rapid ligation kit purchased from the same manufacturer.

Recombinant pDN19 plasmids were introduced into competent

E. coli DH5

α and BL21 cells and recombinant pMMB67HE plasmids were introduced into competent

E. coli DH5

α cells by transformation. Sixteen randomly selected

E. coli BL21 and Dh5

α transformants were then selected on Luria-Bertani agar supplemented with tetracycline (10

µg/ml), X-Gal, and Isopropyl ß-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to perform Blue-White screening [

7,

8,

9] on transformed

E. coli colonies. White colonies were then amplified via colony PCR and run on 1% agarose gels to verify the presence of recombinant plasmid containing the

ampC gene insert.

2.3. Conjugation of P. aeruginosa

Donor recombinant DH5α E. coli cells containing recombinant pDN19 and pMMB67HE plasmids were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) media supplemented with tetracycline (10 µg/ml). E. coli carrying prk2013 was cultured in kanamycin (10 µg/ml) and recipient P. aeruginosa δampC was grown in LB media overnight. 1 ml of each cell culture was washed and re- suspended with LB media. Equal volumes of donor, recipient, and E. coli prk2013 cultures were mixed then spotted on LB and incubated for 10-12 at 37°C. Recombinant P. aeruginosa ∆ampC containing the plasmid of interest were selected on LB agar supplemented tetracycline (30 µg/ml) and irgasan (25 µg/ml).

2.4. β–Lactamase Assay

Wild type P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 strains (both induced and uninduced with 500 µg/ml of penicillin G benzathine) as well as E. coli DH5α and BL21 cells and P. aeruginosa PAO1 ∆ampC transformed with recombinant pMMB67HE and pDN19 plasmids were directly assessed for their β–lactamase producing capabilities to test the expression of the cloned ampC gene. DH5α and BL21 E. coli recombinant cells were suspended in 100 µM phosphate buffer, pH 7. 100 µl of cell suspensions were mixed with equal volumes of colorimetric substrate of β–lactamase (nitrocefin, 0.5 mg/ml) and color change of solutions (from yellow to red) were observed after a ten-minute incubation at 37°C.

2.5. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (AST) was performed on

E. coli isolates to confirm the expression of

ampC through susceptibility to

β–lactam antibiotics. AST was performed by the Disk diffusion by the Kirby-Bauer method [

10]. Expression of the

ampC gene in

P. aeruginosa was first confirmed by testing pairs of isogenic

P. aeruginosa isolates induced with 50

µg/ml penicillin G benzathine for their susceptibility to

β–lactam antibiotics, including ceftazidime (CAZ, 30

µg/ml), piperacillin (TZP, 110

µg/ml), cefepime (FEP, 30

µg/ml), meropenem (MEM 10

µg/ml), cefotaxime (CTX, 30

µg/ml), and penicillin G benzathine (50

µg/ml).

To identify the antibiotic used for selection of expression of functional β–lactamase, E. coli DH5α and BL21 transformed with recombinant pDN19 and pMMB67HE plasmids were tested for their succeptibility to cefixime (CFM, 10 µg/ml), ampicillin (AMP, 50 µg/ml), carabanicillin (CB, 50 µg/ml), ceftazidime (CAZ, 10µg/ml), gentamicin (GEN, 15 µg/ml), and penicillin G benzathine (PEN 50 µg/ml).

Finally, functional expression of β–lactamase was confirmed in P. aeruginosa ∆ampC transformants, the model that will be used for testing ampC expression during mutagenesis. These strains were tested for their susceptibility to the same antibiotics and concentrations used for E. coli transformants.

A less than 1 cm difference in the inhibition zones between bacterial isolates transformed with plasmid carrying or lacking ampC was used as the criteria for resistance to the β–lactam antibiotics, therefore confirming β–lactamase production and ampC expression.

3. Results

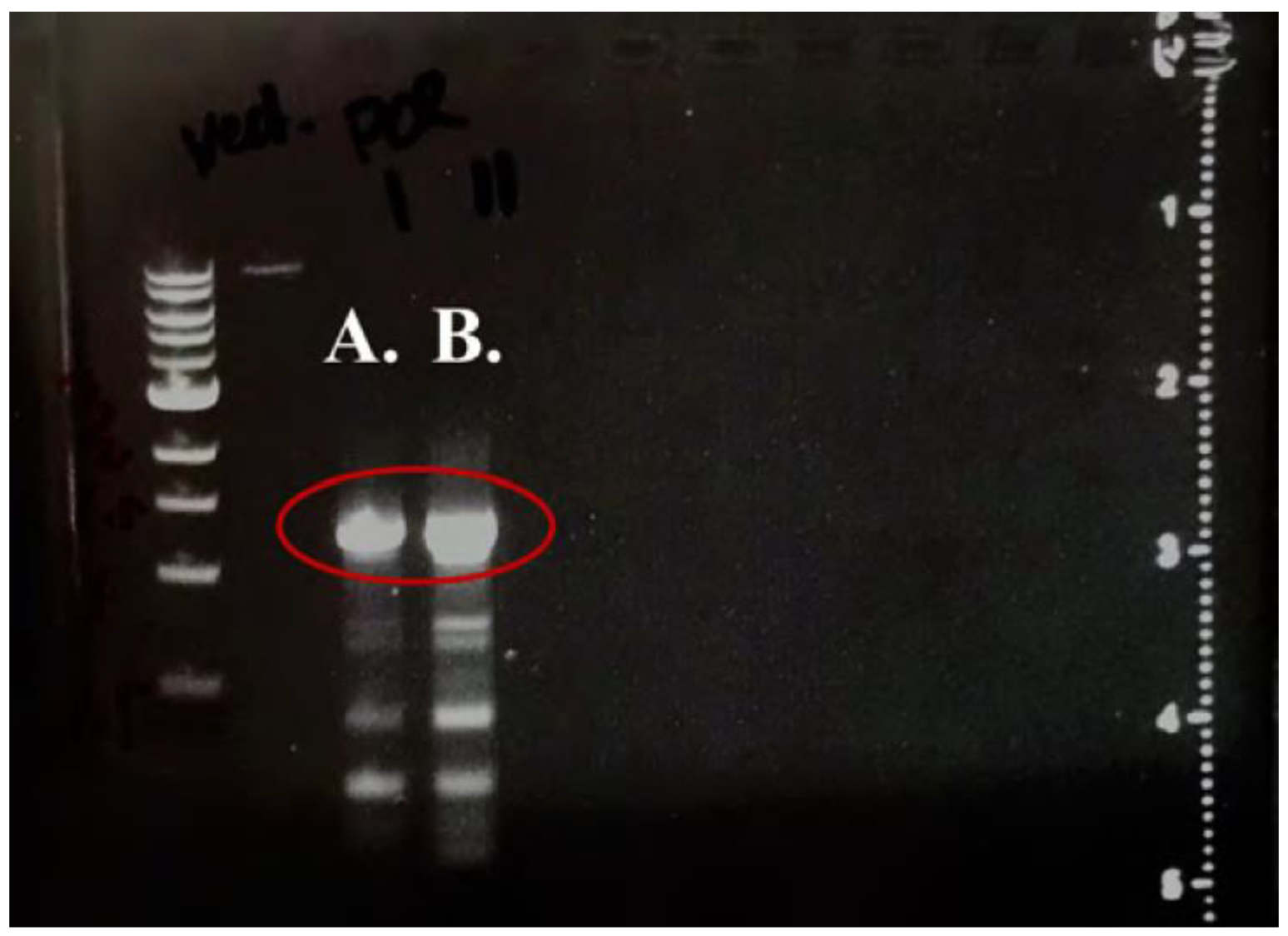

3.1. GE Confirms Successful Cloning of ampC

ampC was successfully amplified via PCR and ligated into pDN19 and pMMB67HE. Presence of PCR product after cutting and cleanup was confirmed on 1% agarose gels, as shown by

Figure 1.

Colony PCR was conducted on 16 randomly selected

E. coli transformants and products were run on 1% agarose gels to confirm presence of recombinant pDN19 and pMMB67HE plasmids and gene insert (

Figure 2). 15 of the 16 randomly selected pMMB67HE colonies and 9 of the 16 pDN19 colonies were successfully transformed with their respective recombinant plasmids.

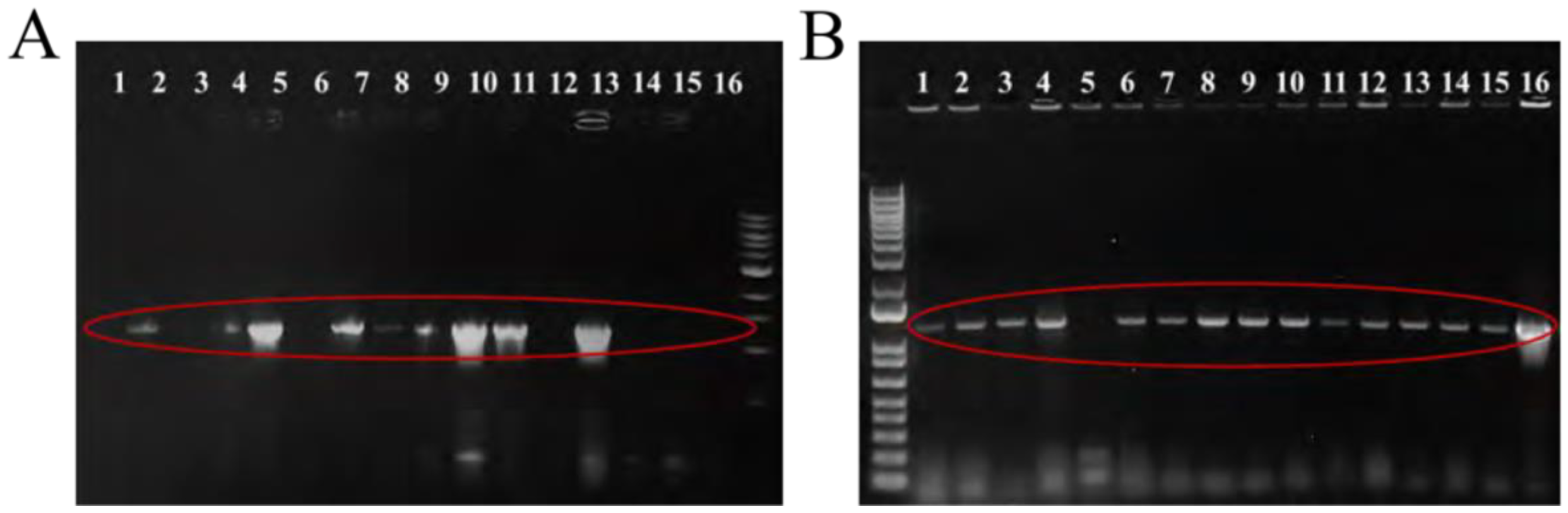

3.2. Successful Conjugation of P. aeruginosa

P. aeruginosa ∆

ampC was successfully conjugated with pDN19 and pMMB67HE plasmid. Little growth was observed on control plates without the helper

E. coli prk2013, whereas individual colonies were seen in mating with all three strains, ensuring that selected

Pseudomonas colonies contained the recombinant plasmids (

Figure 3).

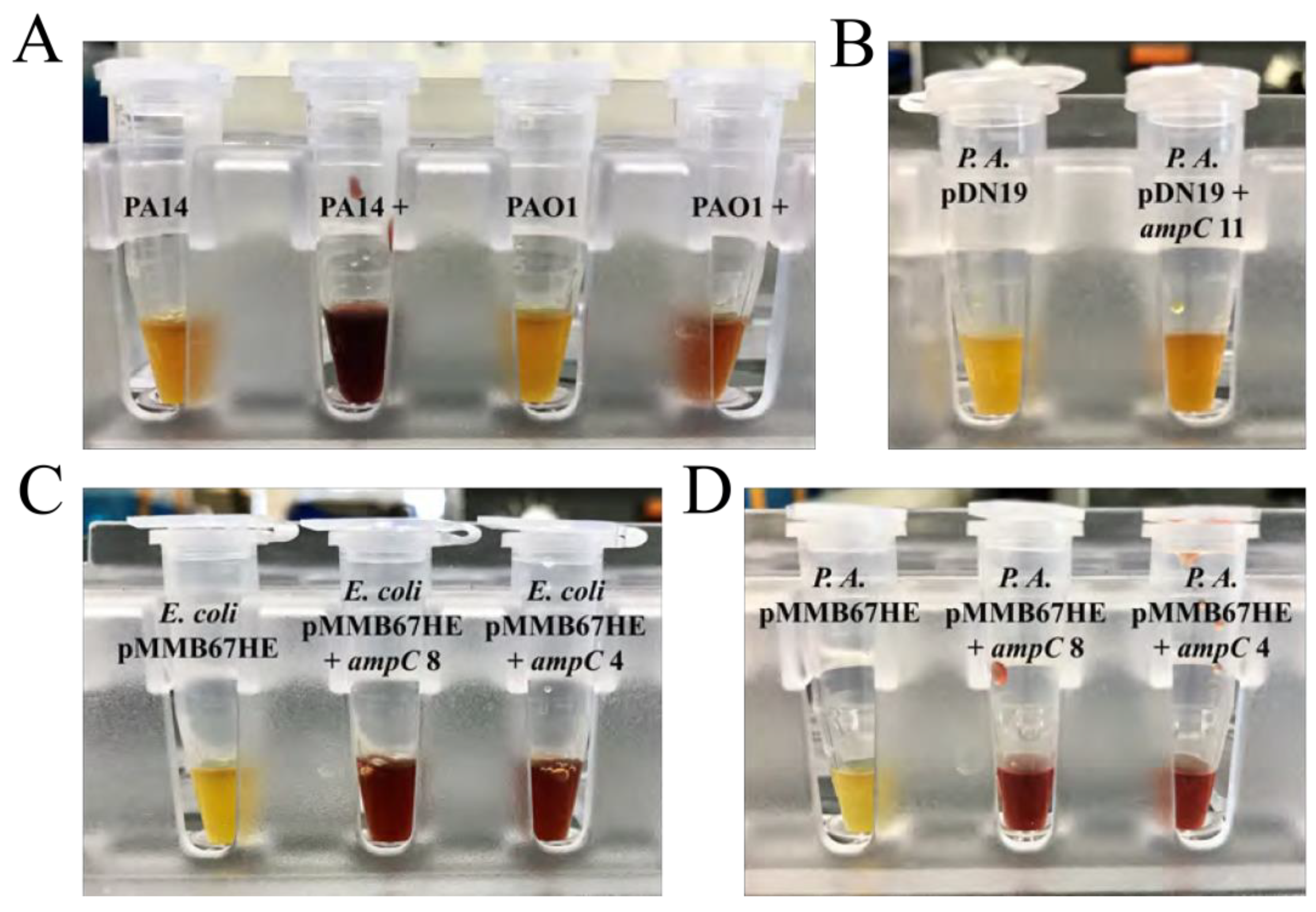

3.3. Induced ampC Produces β–Lactamase

P. aeruginosa PA14 and PAO1 induced with penicillin G produced

β–lactamase, while uninduced strains did not (

Figure 4A). This is likely because expression of

ampC relies on penicillins that are capable of inducing damage to the cell wall without compromising the bacteria.

P. aeruginosa carrying pDN19 with

ampC produced minimal quantities of

β–lactamase, although likely not enough to result in a significant difference in sensitivity to

β–lactams (

Figure 4B). However, both

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa carrying

ampC in the pMMB67HE plasmid both expressed the gene, producing a significant quantities of

β–lactamase (

Figure 4C and (

Figure 4D, respectively). pMMB67HE displayed early signs of promise as a host vector for

ampC ; this is likely because pMMB67HE has its own expression system (tac promoter) within the plasmid, which can lead to much higher system expression.

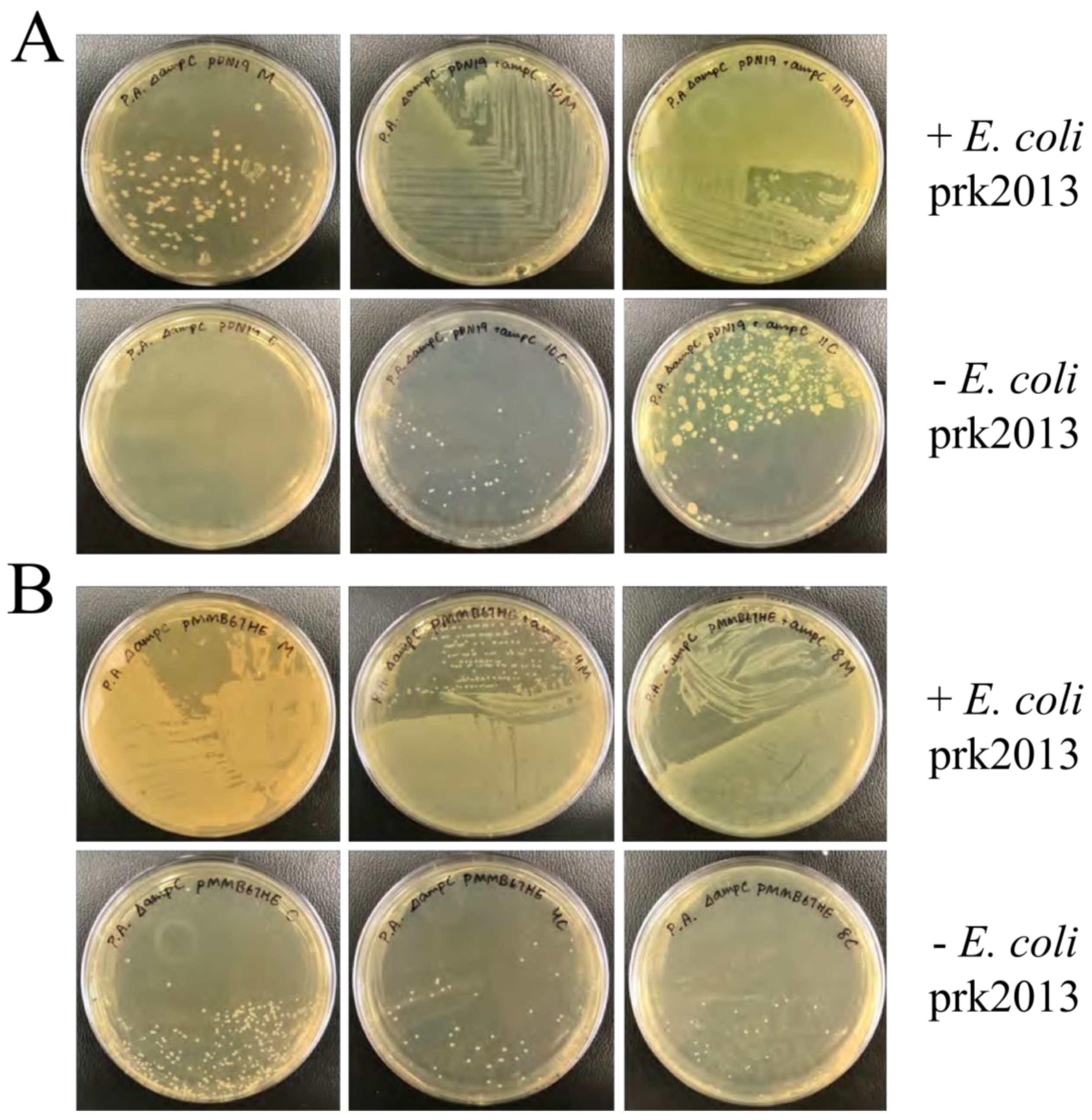

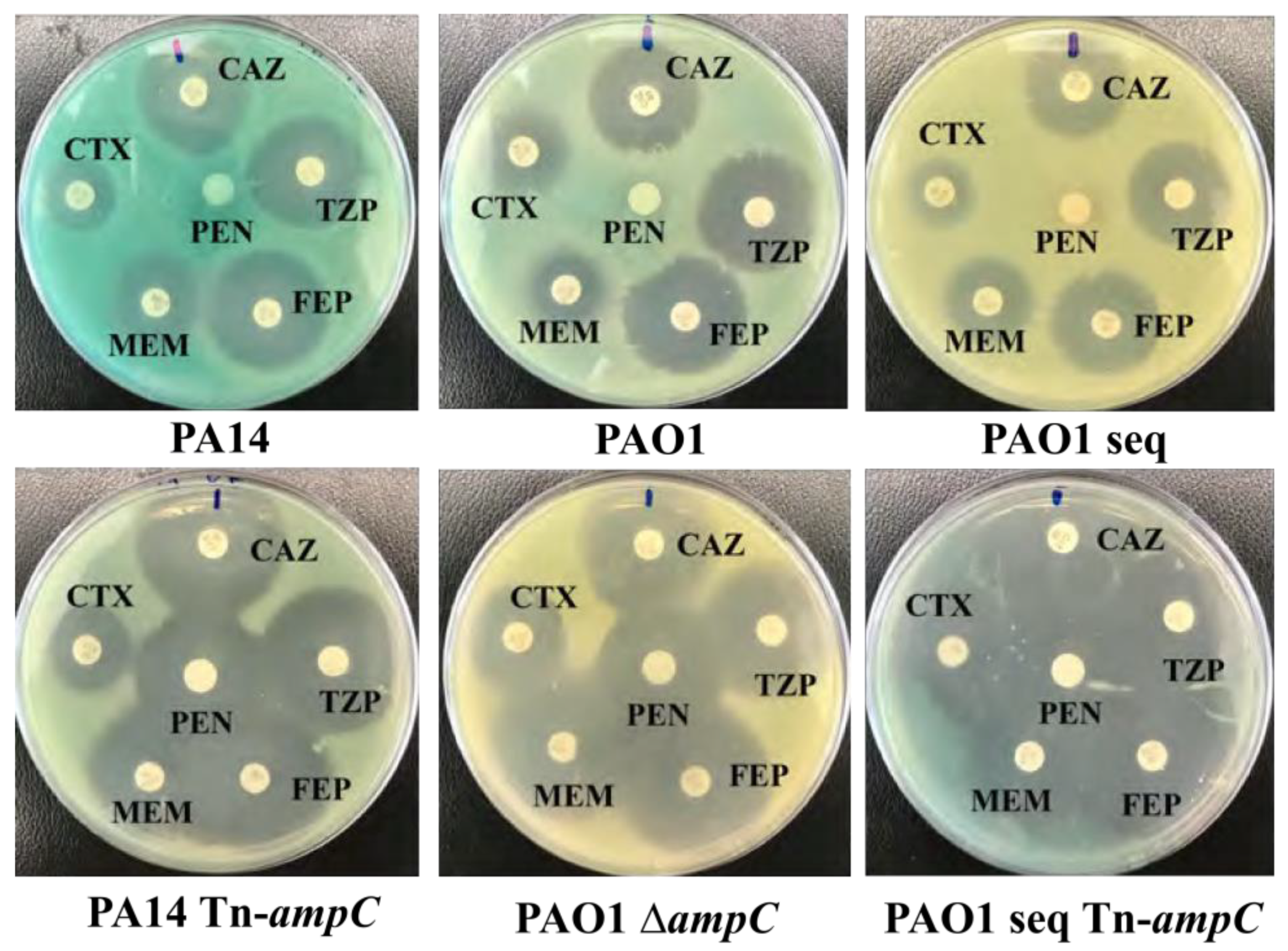

3.4. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing Confirms ampC Expression

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing suggested expression of

ampC through susceptibility to penicillin G, but demonstrated equal susceptibility to cephalasporin antibiotics. This was likely due to inadequate induction of

ampC (50

µg/ml of penicillin G). The additional 50

µg/ml of penicillin added to

P. aeruginosa during AST was likely enough to induce

ampC, explaining why penicillin G was the only antibiotic

P. aeruginosa was resistant to (

Figure 5). When

P. aeruginosa was induced with 500

µg/ml of penicillin G, it produced much greater quantities of

β–lactamase. If antibiotic susceptibility testing was reconducted on isogenic

Pseudomonas, strains containing

ampC would likely confer resistance to most cephalosporins (

Table 1).

ampC expression was not detected in

E. coli DH5

α and BL21 or

P. aeruginosa ∆

ampC transformants containing pDN19 with

ampC, as revealed in

Table 2. This result is supported by the low levels of

β–lactamase produced by

P. aeruginosa ∆

ampC containing pDN19 with

ampC (

Figure 4B). There did not appear to be a signficant difference in

ampC expression between

E. coli DH5

α and the higher expressing BL21 strain (

Table 2).

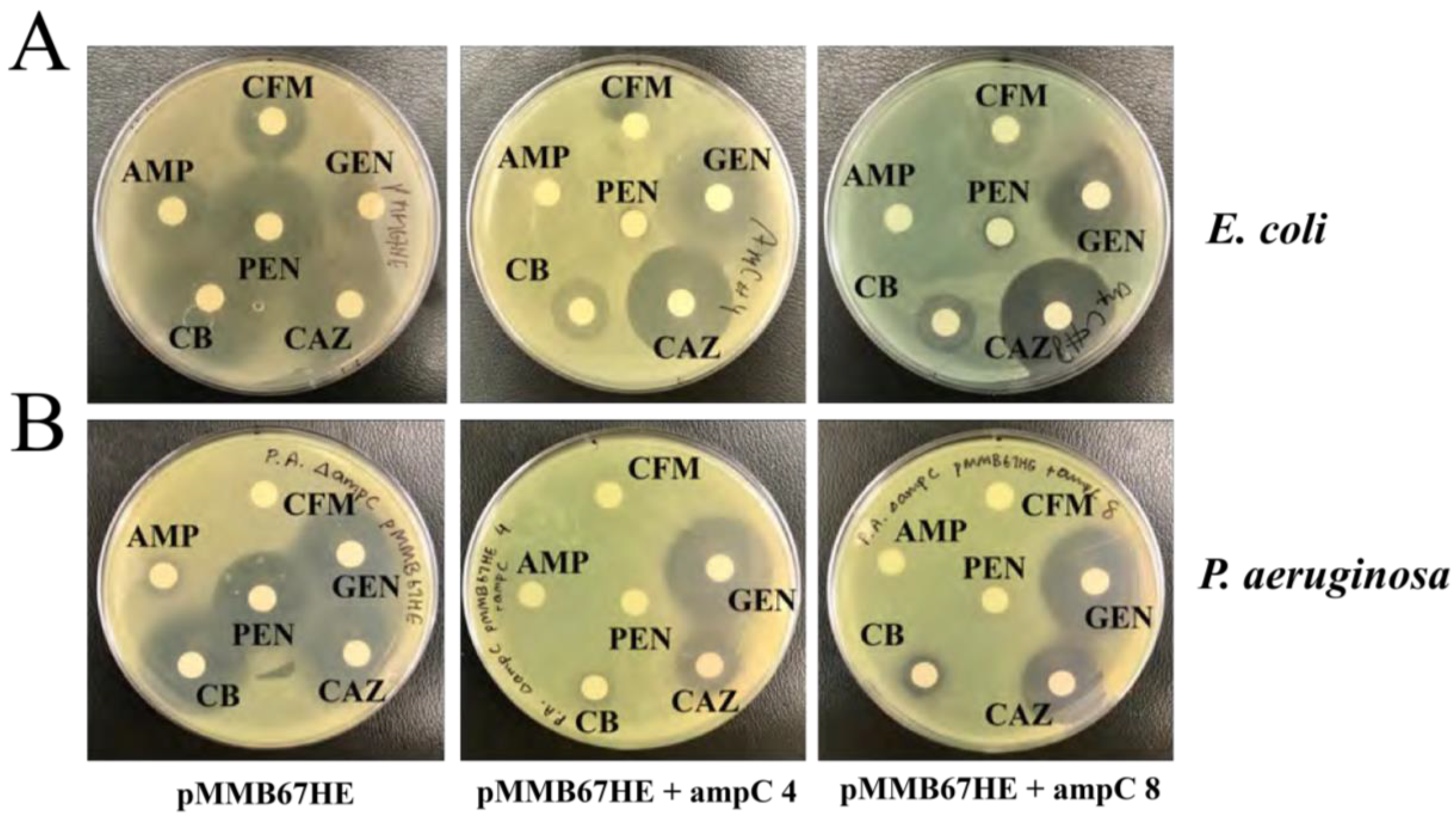

ampC expression was detected in

E. coli DH5

α and

P. aeruginosa ∆

ampC containing pMMB67HE with

ampC, supported by their resistance to ampicillin, penicillin G, and carbenicillin (

Table 3). pMMB67HE was determined as the more effective host vector for

ampC gene expression in both

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa.

Carbenicillin was chosen as the antibiotic used for selection of functional

β–lactamase production during mutagenesis (

Figure 6). This is because both

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa displayed resistance to carbenicillin and it had the largest difference in zones of inhibition between strains with and without

ampC (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

AmpC

β–lactamase produced by

E. coli was the first bacterial enzyme that destroyed penicillins, the most widely prescribed antibiotic [

11]. However, since then, few studies have explored

ampC-regulated

β–lactamase production in

P. aeruginosa, which is more deadly (responsible for millions of deaths) thus its mechanism is relatively unknown.

In this study, the chromosomal

ampC gene was confirmed to express

β–lactamase in

P. aeruginosa, putting to rest alternative theories of

P. aeruginosa β–lactamase produc- tion being primarily plasmid-mediated [

12]. This study is also the first of its kind to isolate chromosomal

ampC in

P. aeruginosa, clone the gene into a vector, and create a successful, self-sustaining system for

ampC expression in both

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa ∆

ampC. Because pMMB67HE contains its own tac promoter, its expression is not reliant on tran- scription regulators inherent to a specific bacterium [

13]. Furthermore, this vector can easily be regulated by IPTG; for these reasons, this is likely why PMMB67HE was more effective than pDN19. pMMB67HE could be a useful tool to induce expression of

ampC and other chromosomal genes.

pMMB67HE being utilized as the host vector will allow for

ampC expression to be detected during mutagenesis. If mutagenesis was conducted on

ampC, potential allosteric binding sites on

β–lactamase would provide groundbreaking insights into developing

β–lactamase inhibitors that inactivate

β–lactamase. Due to the nature of allosteric inhibition, this type of inhibitor would mitigate the possibilities of

P. aeruginosa conferring resistance to it, offering a sustainable solution in combating

Pseudomonas infections. Furthermore, in developing countries where penicillins are more cost-effective, a

β–lactamase inhibitor that renews the efficacy of

β–lactam antibiotics would increase accessibility of

P. aeruginosa therapeutics. This could propel drug discovery in the direction of developing safer therapeutics that remain effective in the long-term. [

14].

5. Future Work

Because ampC was experimentally confirmed as the gene expressing for β–lactamase in P. aeruginosa, and ampC has been isolated and cloned into E. coli, further tests may now be conducted on β–lactamase produced by P. aeruginosa.

Because the pMMB67HE plasmid was identified as the optimal host vector for ampC expression, this plasmid will be used to express ampC during mutagenesis. Furthermore, since the expression in pMMB67HE can be regulated by IPTG, this is a suitable template for mutagenesis. During mutagenesis, copies of ampC will be ligated into pMMB67HE then transformed in P. aeruginosa ∆ampC to test for expression, using carbenicillin as the selecting antibiotic.

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of carbenicillin on P. aeruginosa will need to be determined in order to identify the concentration of antibiotic required for selection of P. aeruginosa cells producing functional β–lactamase. Mutated copies will be sequenced before and after selection to identify mutations that affect the expression of functional β–lactamase. Relevant mutation sites located in close proximity to one another could act as potential allosteric binding sites for novel β–lactamase inhibitors.

6. Conclusion

ampC was first verified as the gene encoding for β–lactamase in P. aeruginosa by a β–lactamase assay. ampC was then successfully isolated and cloned into E. coli in pDN19 and pMMB67HE plasmids. β–lactamase assays on E. coli recombinants found that ampC produced more β–lactamase when in pMMB67HE compared to pDN19, suggesting greater ampC expression in this pMMB67HE.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) conducted on recombinant E. coli confirmed this result: no β–lactamse met the criteria for resistance (thus no β–lactamase expression detected) for pDN19 containing ampC whereas three β–lactams (ampicillin, pen-G, carbeni- cillin) met the criteria for resistance (thus β–lactamase expression detected) in pMMB67HE.

Both recombinant plasmids were conjugated into ampC deficient strain of P. aeruginosa and β–lactamase assay supported greater production of β–lactamase of ampC in pMMB67HE compared to pDN19 within Pseudomonas. AST on these strains confirmed this result, finding β–lactamase to provide most specificity to carbenicillin in P. aeruginosa. It was concluded that the pMMB67HE plasmid was the optimal host vector for ampC expression, and carbenicillin was selected as the antibiotic used for selection. A functional model of measuring β–lactamase for mutagenesis was thus developed: pMMB67HE ligated with ampC in P. aeruginosa with carbenicillin acting as the potential selecting antibiotic.

Appendix A

Figure 7.

Primer sequences of forward (EcoRI) and reverse (XbaI) restriction enzymes used for the cleaving of the ampG gene. The underlined segment of the primer sequence highlights sequence of the enzyme’s restriction site.

Figure 7.

Primer sequences of forward (EcoRI) and reverse (XbaI) restriction enzymes used for the cleaving of the ampG gene. The underlined segment of the primer sequence highlights sequence of the enzyme’s restriction site.

Table 4.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of selected E. coli DH5α pDN19 transformants (10, 11, and 13) treated with cefixime, gentamicin, cephtazadine, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and pen-G.

Table 4.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of selected E. coli DH5α pDN19 transformants (10, 11, and 13) treated with cefixime, gentamicin, cephtazadine, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and pen-G.

| |

Strain |

|

β-lactam |

pDN19 |

pDN19 + ampC 10 |

pDN19 + ampC 11 |

pDN19 + ampC 13 |

| Cefixime |

3.5 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

4.2 |

| Gentamicin |

2.4 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

| Cephtazadine |

2.8 |

3.8 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

| Carbenicillin |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

| Ampicillin |

1.7 |

2.0 |

1.6 |

1.9 |

| Pen-G |

3.0 |

2.7 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

Table 5.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of selected E. coli BL21 pDN19 transformants (10 and 11) treated with cefixime, gentamicin, cephtazadine, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and pen-G.

Table 5.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of selected E. coli BL21 pDN19 transformants (10 and 11) treated with cefixime, gentamicin, cephtazadine, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and pen-G.

| |

Strain |

|

β–lactam |

pDN19 |

pDN19 + ampC 10 |

pDN19 + ampC 11 |

| Cefixime |

5.2 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

| Gentamicin |

2.7 |

2.0 |

2.8 |

| Cephtazadine |

3.6 |

4.2 |

4.2 |

| Carbenicillin |

3.6 |

3.4 |

4.4 |

| Ampicillin |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

| Penicillin G Benzathine |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.4 |

Table 6.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of selected E. coli DH5α pMMB67HE transformants (4 and 8) treated with cefixime, gentamicin, cephtazadine, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and pen-G.

Table 6.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of selected E. coli DH5α pMMB67HE transformants (4 and 8) treated with cefixime, gentamicin, cephtazadine, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and pen-G.

| |

Strain |

|

β–lactam |

DH5α pMMB67HE |

pMMB67HE + ampC 4 |

pMMB67HE + ampC 8 |

| Cefixime |

2.0 |

0 |

0 |

| Gentamicin |

1.8 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

| Cephtazadine |

3.4 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

| Carbenicillin |

3.8 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

| Ampicillin |

1.9 |

0 |

0 |

| Penicillin G Benzathine |

3.2 |

0 |

0 |

Table 7.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of selected P. aeruginosa ∆ampC pDN19 transformants (10 and 11) treated with cefixime, gentamicin, cephtazadine, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and pen-G.

Table 7.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of selected P. aeruginosa ∆ampC pDN19 transformants (10 and 11) treated with cefixime, gentamicin, cephtazadine, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and pen-G.

| |

Strain |

| Beta-lactam |

pDN19 |

pDN19 + ampC 10 |

pDN19 + ampC 11 |

| Cefixime |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Gentamicin |

2.8 |

2.5 |

2.8 |

| Cephtazadine |

2.4 |

2.6 |

2.6 |

| Carbenicillin |

2.0 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

| Ampicillin |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

| Pen-G |

2.6 |

0 |

1.9 |

Table 8.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of selected P. aeruginosa ∆ampC pMMB67HE transformants (4 and 8) treated with cefixime, gentamicin, cephtazadine, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and pen-G.

Table 8.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of selected P. aeruginosa ∆ampC pMMB67HE transformants (4 and 8) treated with cefixime, gentamicin, cephtazadine, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and pen-G.

| |

Strain |

|

β-lactam

|

pMMB67HE |

pMMB67HE + ampC 4 |

pMMB67 + ampC 8 |

| Cefixime |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Gentamicin |

2.6 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

| Cephtazadine |

2.5 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

| Carbenicillin |

2.8 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

| Ampicillin |

0.9 |

0 |

0 |

| Penicillin G Benzathine |

2.4 |

0 |

0 |

References

- G. P. Bodey, R. Bolivar, V. Fainstein, and L. Jadeja. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Reviews of Infectious Diseases, 5(2):279–313, 1983. [CrossRef]

- W.-H. Zhao and Z.-Q. Hu. β-lactamases identified in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 36(3):245–258, 2010. [CrossRef]

- G. F. Gad, R. A. El-Domany, and H. M. Ashour. Antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in egypt. The Journal of Urology, 180(1):176–181, 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Tooke, P. Hinchliffe, E. C. Bragginton, C. K. Colenso, V. H. Hirvonen, Y. Take- bayashi, and J. Spencer. β-lactamases and β-lactamase inhibitors in the 21st century. Journal of Molecular Biology, 431(18):3472–3500, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, J. Wang, R. Wang, and Y. Cai. Resistance to ceftazidime–avibactam and underlying mechanisms. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 22:18–27, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Zasowski, J. M. Rybak, and M. J. Rybak. The β-lactams strike back: Ceftazidime- avibactam. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy, 35(8):755–770, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Ullmann, F. Jacob, and J. Monod. Characterization by in vitro complementation of a peptide corresponding to an operator-proximal segment of the β-galactosidase structural gene of escherichia coli. Journal of Molecular Biology, 24(2):339–343, 1967. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Brandt, A. H. Gabrik, and L. E. Vickery. A vector for directional cloning and expression of polymerase chain reaction products in Escherichia coli. Gene, 97(1):113– 117, 1991. [CrossRef]

- D. Juers, B. Matthews, and R. Huber. Lacz b-galactosidase: Structure and function of an enzyme of historical and molecular biological importance, 21, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Hudzicki. Kirby-bauer disk diffusion susceptibility test protocol. American Society for Microbiology, 15:55–63, 2009.

- G. A. Jacoby. Ampc β-lactamases. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 22(1):161–182, 2009. [CrossRef]

- B. Zhu, P. Zhang, Z. Huang, H.-Q. Yan, A.-H. Wu, G.-W. Zhang, and Q. Mao. Study on drug resistance of pseudomonas aeruginosa plasmid-mediated ampc β-lactamase. Molecular medicine reports, 7(2):664–668, 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Dykxhoorn, R. S. Pierre, and T. Linn. A set of compatible tac promoter expression vectors. Gene, 177(1-2):133–136, 1996. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Grover. Use of allosteric targets in the discovery of safer drugs. Medical Principles and Practice, 22(5):418–426, 2013. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

ampC gene amplified by PCR. Gel electrophoresis confirmed presence of ampC to be used for insertion (A.) and ampC to be used for analysis (B.), as demonstrated by the band located between 1.0 and 1.5 kb (circled in red).

Figure 1.

ampC gene amplified by PCR. Gel electrophoresis confirmed presence of ampC to be used for insertion (A.) and ampC to be used for analysis (B.), as demonstrated by the band located between 1.0 and 1.5 kb (circled in red).

Figure 2.

A. Cloning ampC into pDN19 and transformed into E. coli DH5α. Colony PCR of 16 randomly selected DH5α transformants confirmed the presence of the pDN19 recombinant plasmid containing the ampC gene insert, as demonstrated by the band located between 1.0 and 1.5 kb (circled in red). Colonies 5, 10, 11, and 13 were selected on Luria-Bertani agar supplemented with tetracycline (10 µg/ml) and utilized for antibiotic susceptibility testing. B. Cloning ampC into pMMB67HE and transformed into E. coli DH5α. Colony PCR of 16 randomly selected DH5α transformants confirmed the presence of the pMMB67HE recombinant plasmid containing the ampC, as demonstrated by the band located above 1.5 kb (circled in red). Colonies 4, 9, and 10 were selected on Luria-Bertani agar supplemented with tetracycline (10 µg/ml) and utilized for antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Figure 2.

A. Cloning ampC into pDN19 and transformed into E. coli DH5α. Colony PCR of 16 randomly selected DH5α transformants confirmed the presence of the pDN19 recombinant plasmid containing the ampC gene insert, as demonstrated by the band located between 1.0 and 1.5 kb (circled in red). Colonies 5, 10, 11, and 13 were selected on Luria-Bertani agar supplemented with tetracycline (10 µg/ml) and utilized for antibiotic susceptibility testing. B. Cloning ampC into pMMB67HE and transformed into E. coli DH5α. Colony PCR of 16 randomly selected DH5α transformants confirmed the presence of the pMMB67HE recombinant plasmid containing the ampC, as demonstrated by the band located above 1.5 kb (circled in red). Colonies 4, 9, and 10 were selected on Luria-Bertani agar supplemented with tetracycline (10 µg/ml) and utilized for antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Figure 3.

P. aeruginosa ∆ampC and E. coli matings. A. Matings of P. aeruginosa ∆ampC and E. coli carrying pDN19. Colony growth was significantly larger in matings supplemented with E. coli prk2013 (top row) compared to without (bottom row), indicating that most selected P. aeruginosa colonies were truly conjugated. B. Matings of P. aeruginosa ∆ampC and E. coli recombinant pMMB67HE (pMMB67HE + ampC ). Colony growth was significantly larger in matings supplemented with E. coli prk2013 (top row) compared to without (bottom row), indicating that most selected P. aeruginosa were truly conjugated.

Figure 3.

P. aeruginosa ∆ampC and E. coli matings. A. Matings of P. aeruginosa ∆ampC and E. coli carrying pDN19. Colony growth was significantly larger in matings supplemented with E. coli prk2013 (top row) compared to without (bottom row), indicating that most selected P. aeruginosa colonies were truly conjugated. B. Matings of P. aeruginosa ∆ampC and E. coli recombinant pMMB67HE (pMMB67HE + ampC ). Colony growth was significantly larger in matings supplemented with E. coli prk2013 (top row) compared to without (bottom row), indicating that most selected P. aeruginosa were truly conjugated.

Figure 4.

Color change from yellow to red after ten minutes upon addition of nitrocefin revealed production of β–lactamase. A. P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 induced with penicillin G (+) changed colors from yellow to light red and deep red (respectively), confirming their production of β–lactamase. B. P. aeruginosa ∆ampC conjugated with pDN19 did not change colors while P. aeruginosa conjugated with pDN19 containing ampC changed colors slightly from yellow to light orange. This color change was insufficient to confirm β– lactamase production. C. E. coli carrying pMMB67HE did not change colors while E. coli containing pMMB67HE with ampC changed colors significantly to dark red. This confirmed β–lactamase expression in E. coli transformants carrying ampC. D. P. aeruginosa ∆ampC carrying pMMB67HE did not change colors while P. aeruginosa carrying pMMB67HE with ampC changed colors significantly to dark red. This confirmed β–lactamase expression in P. aeruginosa conjugates with ampC.

Figure 4.

Color change from yellow to red after ten minutes upon addition of nitrocefin revealed production of β–lactamase. A. P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 induced with penicillin G (+) changed colors from yellow to light red and deep red (respectively), confirming their production of β–lactamase. B. P. aeruginosa ∆ampC conjugated with pDN19 did not change colors while P. aeruginosa conjugated with pDN19 containing ampC changed colors slightly from yellow to light orange. This color change was insufficient to confirm β– lactamase production. C. E. coli carrying pMMB67HE did not change colors while E. coli containing pMMB67HE with ampC changed colors significantly to dark red. This confirmed β–lactamase expression in E. coli transformants carrying ampC. D. P. aeruginosa ∆ampC carrying pMMB67HE did not change colors while P. aeruginosa carrying pMMB67HE with ampC changed colors significantly to dark red. This confirmed β–lactamase expression in P. aeruginosa conjugates with ampC.

Figure 5.

Isogenic Pseudomonas strains treated with ceftazidime (CAZ), priperacillin (TZP), cefepime (FEP), meropnem (FEP), cefotaxime (CTX), and penicillin G (PEN) (orientation of antibiotics was the same for all plates). All Pseudomonas strains with ampC were not susceptible to penicillin G compared to strains without ampC.

Figure 5.

Isogenic Pseudomonas strains treated with ceftazidime (CAZ), priperacillin (TZP), cefepime (FEP), meropnem (FEP), cefotaxime (CTX), and penicillin G (PEN) (orientation of antibiotics was the same for all plates). All Pseudomonas strains with ampC were not susceptible to penicillin G compared to strains without ampC.

Figure 6.

A. E. coli pMMB67HE recombinants with and without ampC treated with cefixime (CFM), gentamicin (GEN), ceftazidime (CAZ), carbenicillin (CB), ampicillin (AMP), and penicillin G (PEN) (orientation of antibiotics was the same for all plates). All E. coli recombinants with ampC were not susceptible to penicillin G, ampicillin, and carbenicillin compared to strains without ampC. B. P. aeruginosa ∆ampC pMMB67HE recombinants with and without ampC treated with cefixime (CFM), gentamicin (GEN), ceftazidime (CAZ), carbenicillin (CB), ampicillin (AMP), and penicillin G (PEN) (orientation of antibiotics was the same for all plates). All P. aeruginosa recombinants with ampC were not susceptible to penicillin G and carbenicillin compared to strains without ampC.

Figure 6.

A. E. coli pMMB67HE recombinants with and without ampC treated with cefixime (CFM), gentamicin (GEN), ceftazidime (CAZ), carbenicillin (CB), ampicillin (AMP), and penicillin G (PEN) (orientation of antibiotics was the same for all plates). All E. coli recombinants with ampC were not susceptible to penicillin G, ampicillin, and carbenicillin compared to strains without ampC. B. P. aeruginosa ∆ampC pMMB67HE recombinants with and without ampC treated with cefixime (CFM), gentamicin (GEN), ceftazidime (CAZ), carbenicillin (CB), ampicillin (AMP), and penicillin G (PEN) (orientation of antibiotics was the same for all plates). All P. aeruginosa recombinants with ampC were not susceptible to penicillin G and carbenicillin compared to strains without ampC.

Table 1.

Zones of inhibition (cm) of isogenic P. aeruginosa strains with or without ampC treated with ceftazidime, piperacillin, cefepime, meropenem, ceftotaxime, and penicillin G (pen-G). Pen-G met the requirement for resistance (>1 cm difference in zones of inhibition), thus the expression of ampC was detected.

Table 1.

Zones of inhibition (cm) of isogenic P. aeruginosa strains with or without ampC treated with ceftazidime, piperacillin, cefepime, meropenem, ceftotaxime, and penicillin G (pen-G). Pen-G met the requirement for resistance (>1 cm difference in zones of inhibition), thus the expression of ampC was detected.

| |

Strain |

|

β-lactam |

PA14 |

PA14 Tn-ampC

|

PAO1 |

PAO1 ∆ampC

|

PAO1 seq |

PAO1 Tn-ampC

|

| Ceftazidime |

2.5 |

3.0 |

2.4 |

3.0 |

2.1 |

4.2 |

| Piperacillin |

2.5 |

3.2 |

2.5 |

3.4 |

2.2 |

3.4 |

| Cefepime |

2.6 |

3.2 |

2.7 |

3.4 |

2.4 |

3.1 |

| Meropenem |

1.9 |

2.8 |

2.7 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

3.0 |

| Cefotaxime |

1.5 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

2.8 |

| Pen-G |

0 |

2.6 |

0 |

3.0 |

0 |

2.8 |

Table 2.

Average zones of inhibition (cm) of E. coli DH5α and BL21 and P. aeruginosa ∆ampC transformants with cefixime, gentamicin, ceftazidime, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and penicillin G (Pen-G). No β–lactam met the criteria for resistance, thus expression of ampC was not detected in either E. coli DH5α or BL21.

Table 2.

Average zones of inhibition (cm) of E. coli DH5α and BL21 and P. aeruginosa ∆ampC transformants with cefixime, gentamicin, ceftazidime, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and penicillin G (Pen-G). No β–lactam met the criteria for resistance, thus expression of ampC was not detected in either E. coli DH5α or BL21.

| |

Strain |

| DH5α

|

|

BL21 |

|

∆ampC

|

|

|

β-lactam |

pDN19 |

pDN19 + ampC

|

pDN19 |

pDN19 + ampC

|

pDN19 |

pDN19 + ampC

|

| Cefixime |

3.5 |

3.9 |

5.2 |

5.0 |

0 |

0 |

| Gentamicin |

2.4 |

2.1 |

2.7 |

2.4 |

2.8 |

2.7 |

| Ceftazidime |

2.8 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

4.2 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

| Carabanicillin |

3.0 |

3.1 |

3.6 |

3.9 |

2.0 |

1.2 |

| Ampicillin |

1.7 |

1.8 |

2.4 |

2.5 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

| Pen-G |

3.0 |

2.8 |

5.0 |

5.2 |

2.6 |

1.4 |

Table 3.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of E. coli DH5α and P. aeruginosa ∆ampC pMMB67HE transformants treated with cefixime, gentamicin, ceftazidime, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and penicillin G (Pen-G). Carbenicillin and pen-G met the criteria for resistance for both P. aeruginosa and E. coli transformants while carbenicillin met the criteria for resistance in E. coli ; expression of ampC was thus detected in both bacteria.

Table 3.

Zones of Inhibition (cm) of E. coli DH5α and P. aeruginosa ∆ampC pMMB67HE transformants treated with cefixime, gentamicin, ceftazidime, carbenicillin, ampicillin, and penicillin G (Pen-G). Carbenicillin and pen-G met the criteria for resistance for both P. aeruginosa and E. coli transformants while carbenicillin met the criteria for resistance in E. coli ; expression of ampC was thus detected in both bacteria.

| |

Strain |

| DH5α

|

|

∆ampC

|

|

|

β–lactam |

pMMB67HE |

pMMB67HE + ampC

|

pMMB67HE |

pMMB67HE + ampC

|

| Cefixime |

2.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Gentamicin |

1.8 |

2.9 |

2.6 |

2.9 |

| Ceftazidime |

3.4 |

3.0 |

2.5 |

2.0 |

| Carbenicillin |

3.8 |

1.5 |

2.8 |

1.0 |

| Ampicillin |

1.9 |

0 |

0.9 |

0 |

| Pen-G |

3.2 |

0 |

2.4 |

0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).