Submitted:

10 May 2024

Posted:

10 May 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

- The verification in the previous study (Fujii, 2024) was limited because the number of impulsive inputs is fixed to 2 in a critical PDI analysis. The accuracy of the predicted corresponding to depends on the shape of the assumed half cycle of the structural response. In the case of the critical pseudo-multi impulse (PMI) input, the shape of the half cycle of the structural response depends on the number of impulsive inputs (). Therefore, further numerical investigation considering as a parameter is indispensible.

- In the simplified equation using , the influence of the pinching behavior of the RC members on the energy dissipation is not considered. The severe pinching behavior of RC beam-column connections has been reported in experimental studies (e.g., Gentry and Wight, 1994; Kusuhara et al., 2004; Kusuhara and Shiohara, 2008; Benavent-Climent et al., 2009, 2010). Toyoda et al. (2014) compared the shaking table test results of a 1/4-scaled 20-story RC building model conducted at E-defense with NTHA results. They found that, for a better prediction of the peak response, the influence of the pinching behavior of RC beams should be considered. Following their study, Shirai et al. (2024) demonstrated that the pinching behavior of RC members affects the peak responses of 40-story RC super-high-rise buildings. Therefore, the influence of the pinching behavior of RC members on the seismic capacity curve should be investigated.

1.2. Objectives

- (i)

- Considering the critical response of an RC MRF with SDCs subjected to critical PMI input, what is the dependence of the – relationship on the number of impulsive inputs ()?

- (ii)

- How does the pinching behavior of RC members affect the – relationship of RC MRFs? Can the negative influence of the pinching behavior of the RC members on the – relationship be improved by installing SDCs?

- (iii)

- How do and the pinching behavior of RC members affect the ratios of the cumulative energies (cumulative strain energies of the RC MRFs and SDCs) at the end of simulation?

- (iv)

- How does affect the residual equivalent displacement of RC MRFs?

2. Incremental Critical Pseudo-Multi Impulse Analysis

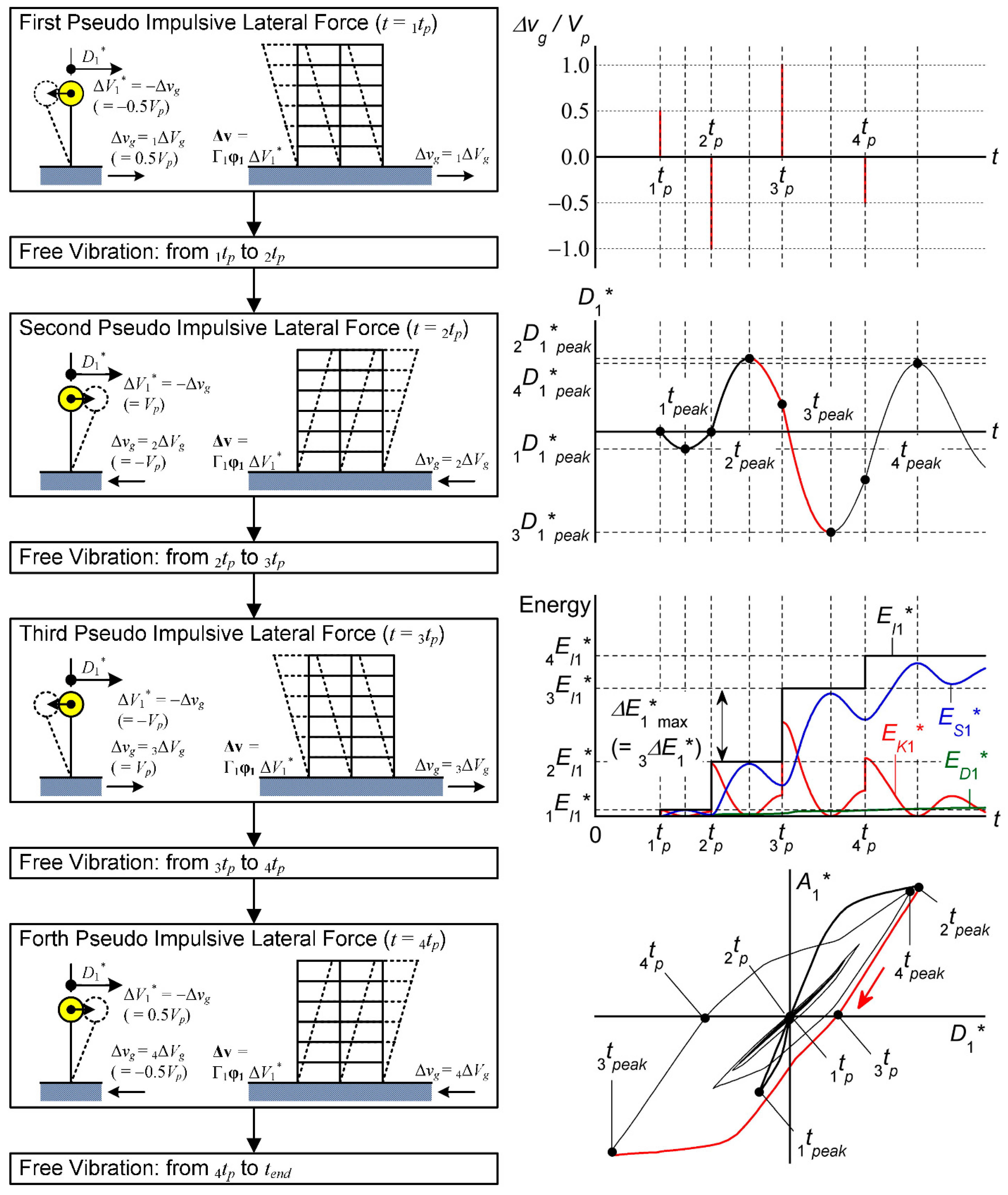

2.1. Outline of the Critical Pseudo-Multi Impulse Analysis

2.1.1. First Pseudo Impulsive Lateral Force

2.1.2. Free Vibration after the First Pseudo Impulsive Lateral Force

2.1.3. Pseudo Impulsive Lateral Force

2.1.4. Free Vibration

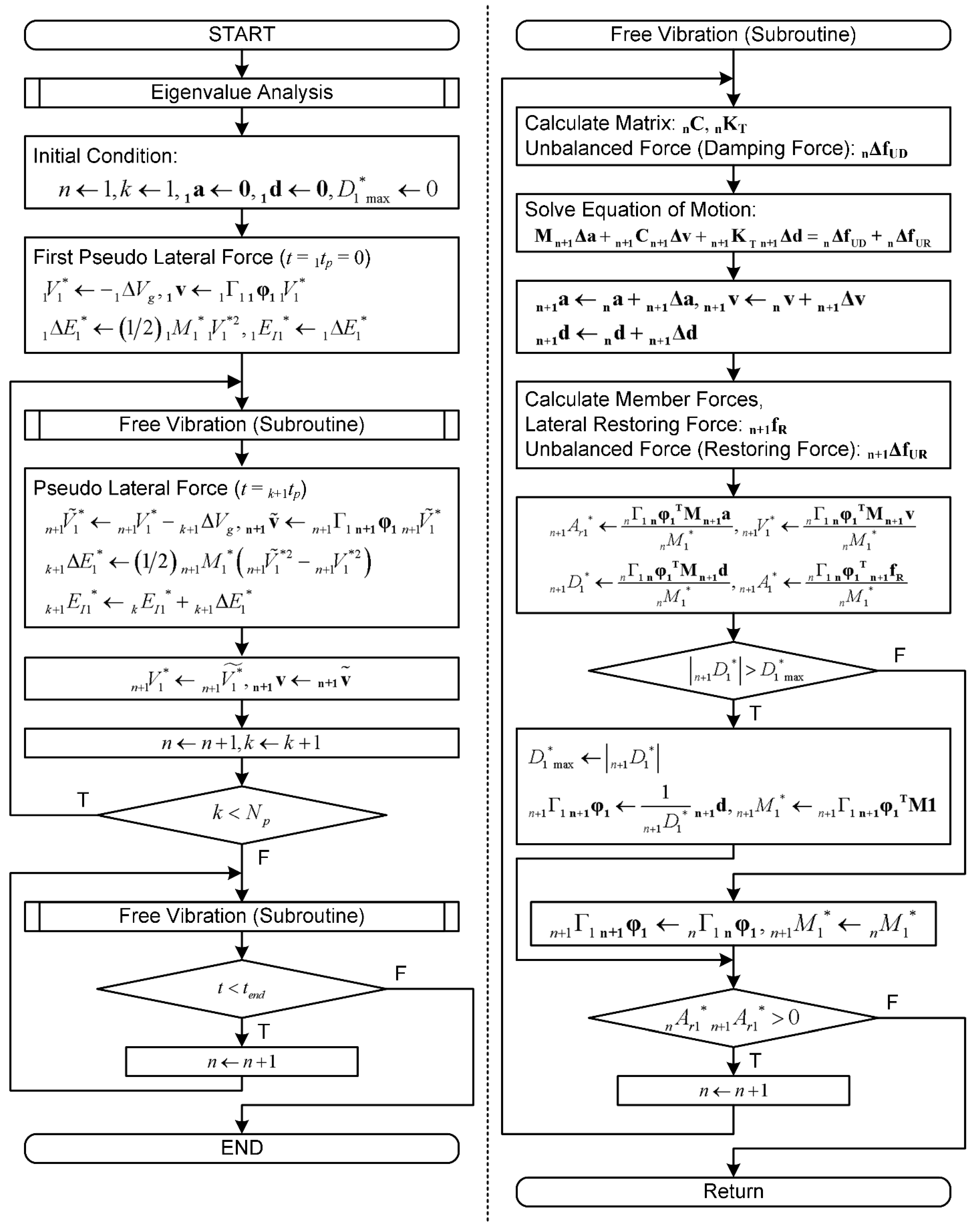

2.2. Analysis Flow of the Critical PMI Analysis

2.3. Calculation of the Seismic Capacity Curve from the Incremental Critical Pseudo-Multi Impulse Analysis (ICPMIA) Results

3. Analysis Data and Methods

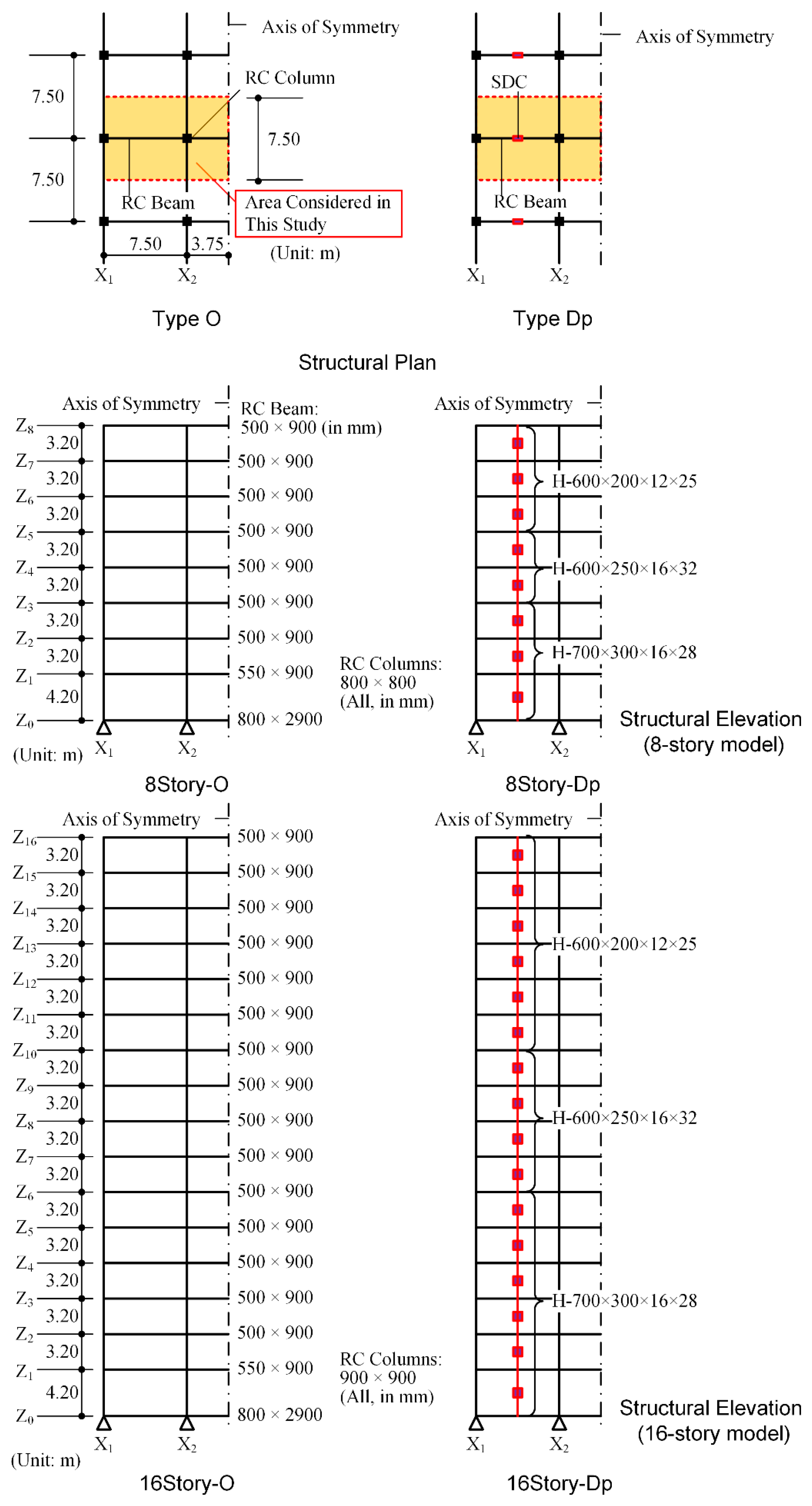

3.1. Building Data

3.2. Analysis Method

4. Analysis Results

4.1. Peak Response

- The peak equivalent displacement () increases as the pulse velocity () increases. For the same value of , the obtained by PDI is smaller than that obtained by PMI ( = 4, 6, and 8).

- For Type O, the increase in as a result of the increase in is significant. This trend is more pronounced when the pinching behavior of the RC members is significant. Comparing of 8story-O with = 0.25 m/s and = 0.25 (significant pinching), is 0.082 m when = 2 (PDI) and 0.247 m when = 8. Similar observations can be mabe for 16story-O.

- For Type Dp, however, the increase in as a result of the increase in is less significant than for Type O. Comparing of 8story-Dp, considering = 0.65 m/s and = 0.25 (significant pinching), is 0.196 m when = 2 (PDI) and 0.258 m when = 8. Similar observations can be made for 16story-Dp.

- For Type O, the increase in the peak story resulting from the increase in is significant, as observed in the trend of . This trend is more pronounced when the pinching behavior of the RC members is significant. Comparing the largest peak story drift of 8story-O, considering = 0.25 m/s and = 0.25 (significant pinching), the largest peak story drift is 0.577% (3rd story) when = 2 (PDI) and 1.78% (3rd story) when = 8. Meanwhile, considering = 0.25 m/s and = 1.00 (perfectly non-pinching), the largest peak story drift is 0.577% (3rd story) when = 2 (PDI) and 1.57% (3rd story) when = 8.

- For Type Dp, however, the increase in the peak story drift as a result of the increase in is less significant than for Type O. Comparing the largest peak story drift of 8story-Dp, considering = 0.65 m/s and = 0.25 (significant pinching), the largest peak story drift is 1.46% (3rd story) when = 2 (PDI) and 1.94% (2nd story) when = 8. Meanwhile, considering = 0.65 m/s and = 1.00 (perfectly non-pinching), the largest peak story drift is 1.46% (3rd story) when = 2 (PDI) and 1.77% (2nd story) when = 8. Similar observations can be made for 16story-Dp.

4.2. Hysteresis Loop and Residual Displacement

- In the critical PDI analysis results ( = 2), the difference in the half cycle of the structural response resulting from the pinching behavior is negligibly small. The displacement response is larger in positive directions than in negative directions. A notable residual equiavalent displacement at = is observed, especially for Type Dp.

- In the critical PMI analysis results ( = 8), the difference in the half cycle of the structural response resulting from the pinching behavior is noticeable. In the case of = 0.25 (significant pinching), the pinching behavior in the half cycle of the structural response is clearly observed for both Types O and Dp. The displacement response is almost symmetric in the positive and negative directions. The residual equivalent displacement is negligibly small for both Types O and Dp.

- For Type O, is smaller than 0.1. The ratio is largest in the critical PDI analysis ( = 2), and increases as increases. However in the critical PMI analysis, is small and no regular trend is observed between and : the ratio may decrease when increases.

- For Type Dp, the ratio increases as increases in the critical PDI analysis ( = 2) and the ratio may be larger than 0.2. The ratio is larger when the parameter is larger (pinching behavior is not significant). However, in the critical PMI analysis, the ratio is smaller than 0.1. In addition, no regular trend is observed between and : the ratio may decrease when increases.

4.3. Cumulative Strain Energy

- For 8story-O, the ratio is close to 0.2 when is less than 0.1 m. The ratio increases as increases when is larger than 0.1 m. When is close to 0.25 m, is between 0.8 and 0.9.

- For 16story-O, the ratio increases as increases when is larger than 0.2 m. When is larger than 0.4 m, is between 0.8 and 0.9.

- The difference in the ratio resulting from the difference in is negligible.

- The ratio increases rapidly as increases. For 8story-Dp, the ratio reaches 0.9 when is larger than 0.2 m. Meanwhile, for 16story-Dp, the ratio reaches 0.9 when is larger than 0.4 m.

- In the PMI analysis results ( ≥ 4), the ratio is larger than that obtained from the PDI analysis results ( = 2).

- The ratio is close to 0.2 when is less than 0.1 m. When is larger than 0.1 m, increases as increases. However, decreases as increases. This trend is pronounced when the parameter is small (the pinching behavior is significant).

- The ratio is negligibly small when is less than 0.06 m. The ratio increases rapidly as increases. The ratio increases as increases. This trend is pronounced when the parameter is small.

- The ratio is close to 0.2 when is less than 0.15 m. When is larger than 0.15 m, increases as increases. However, decreases as increases. Considering = 0.25, the ratio is 0.447 when is 0.487 m in the PDI analysis results ( = 2). Conversely, the ratio is 0.248 when is 0.498 m in the PMI analysis results ( = 8).

- The ratio is negligibly small when is less than 0.1 m. The ratio increases rapidly as increases. The ratio increases as increases. Considering = 0.25, the ratio is 0.466 when is 0.487 m in the PDI analysis results ( = 2). Conversely, the ratio is 0.695 when is 0.498 m in the PMI analysis results ( = 8).

4.4. Summary of the Analysis Results

- A)

- The influence of the number of pseudo impulsive lateral forces () on the – relationship is significant in the case of RC MRFs without SDCs (Type O). For the same value of , the increases as increases. This trend is pronounced when the pinching behaviour is siginificant. In cases of RC MRFs with SDCs (Type Dp), increases as increases; however, this trend is less pronounced than that observed in the RC MRFs without SDCs. The influence of the pinching behavior of the RC MRFs on the – relationship in the RC MRFs with SDCs is smaller than that in the RC MRFs without SDCs.

- B)

- In the PMI analysis results ( ≥ 4), the difference in the half cycle of the structural response resulting from the pinching behavior is more pronounced than that in the PDI analysis results ( = 2). Therefore, the influence of the pinching behavior of the RC members on the peak equivalent displacement () is more notable in PMI than in PDI.

- C)

- The residual displacement obtained from the PMI analysis results is smaller than that obtained from the PDI analysis results ( = 2). This difference is significant in the case of RC MRFs with SDCs.

- D)

- The ratio of the cumulative strain energy of the entire frame model () at the end of the simulation is nearly independent of the number of pseudo impulsive lateral forces (), regardless of the presence or absense of SDCs. Meanwhile, the ratio of the cumulative strain energy of the RC MRFs () decreases and that of the SDCs () increases as increases in the RC MRFs with SDCs (Type Dp). This trend is pronounced when the pinching behavior of the RC members is significant.

5. Prediction of the Maximum Momentary Input Energy of RC MRFs

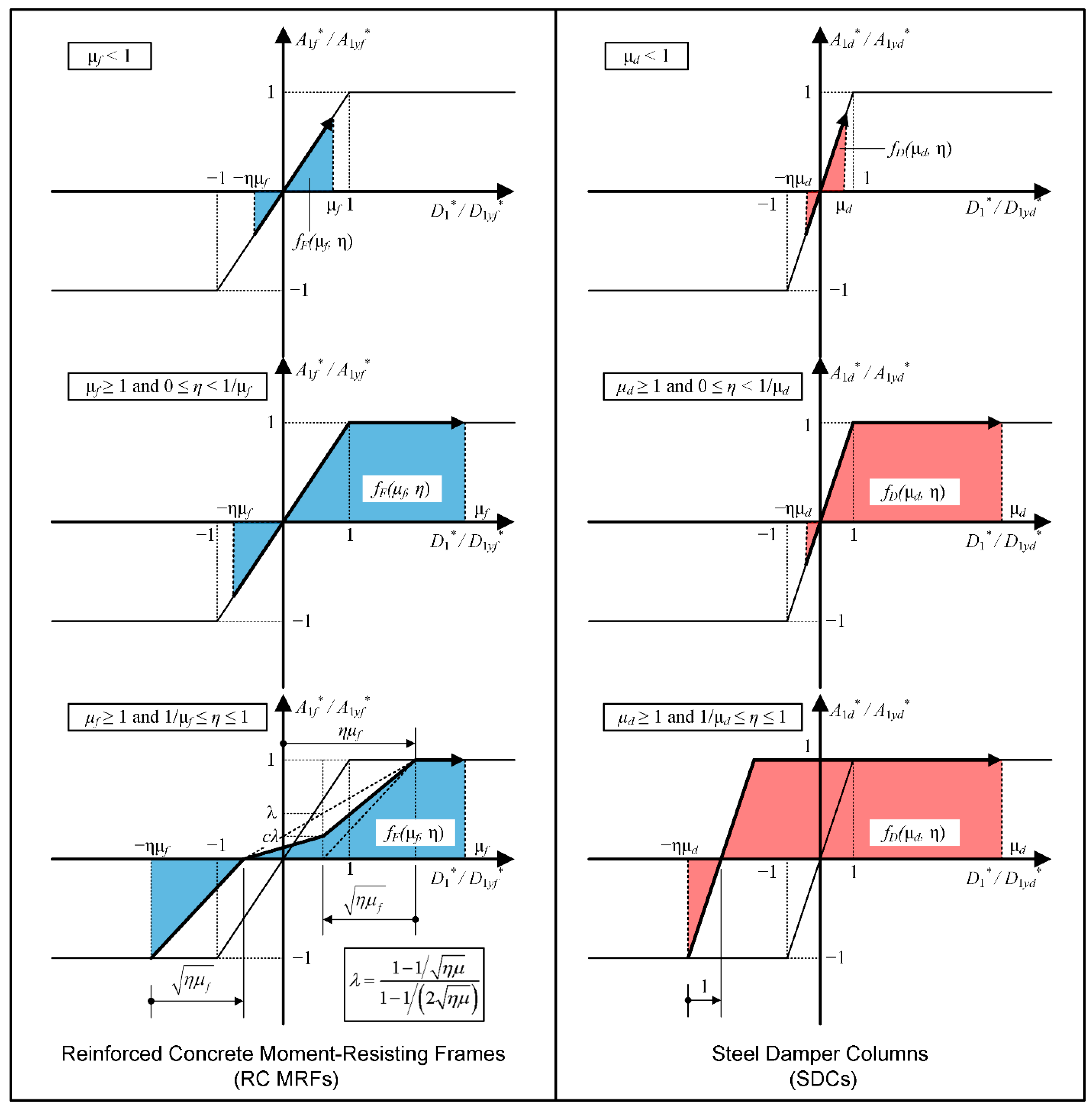

5.1. Simplified Equations for Calculating the Energy Dissipation Capacity during a Half Cycle of the Structural Response

5.2. Prediction of the Seismic Capacity Curve Based on the Pushover Analysis

5.3. Comparisons with ICPMIA Results

- For Type O, the plots obtained from the PDI and PMI analysis ( = 4) results are above the predicted seismic capacity curve. However, the plots obtained from the PMI analysis ( = 6 and 8) results are below the predicted curve. Specifically, for 8story-O, with = 0.25 (significant pinching) and = 8, the value corresponding to = 0.247 m is 0.616 m/s, while the predicted value corresponding to = 0.247 m is 0.802 m/s; this is a 23.1% underestimation of .

- For Type Dp, the plots obtained from the PDI and PMI analysis ( = 4) results agree very well with the predicted seismic capacity curve. In addition, the plots obtained from the PMI analysis ( = 6 and 8) results are slightly below the predicted curve. The dependence of the Type Dp – plots on is limited.

- For Type O, the ratio is between 0.4 and 0.5 in the PDI analysis results. Similarly, in the PMI analysis ( = 4) results, is between 0.5 and 0.6. Meanwhile, in the PMI analysis ( = 6 and 8) results, increases as increases: is between 0.7 and 0.9 when is 6, while is larger than 0.8 when is 8.

- For Type Dp, the ratio is between 0.4 and 0.5 in the PDI analysis results. However, in the PMI analysis ( = 4) results, increases as increases. For 8story-Dp, is close to 0.5 when is close to 0.1 m and reaches 0.7 when is close to 0.25 m. In the PMI analysis ( = 6 and 8) results, is larger than 0.7 and increases as increases; then, approaches 1.

- The contribution from the hysteretic dissipated energy of the RC MRFs () decreases rapidly as increases. Conversely, the contribution from the viscous damping () increases as increases. However, because is much smaller than , the calculated decreases rapidly as increases: is largest when is zero and smallest when is unity.

- The variation in the calculated as a result of the ratio is predominant when the parameter is 0.25 (significant pinching). For 8story-O and = 0.25, the calculated corresponding to = 0 is 0.509 m2/s2, while the calculated corresponding to = 1 is 0.077 m2/s2 (only 15.2% of the value when = 0). Meanwhile, for 8story-O and = 1.00 (perfectly non-pinching), the calculated corresponding to = 0 is 0.509 m2/s2 (the same value as for = 0.25) and the calculated corresponding to = 1 is 0.241 m2/s2 (47.3% of the value when = 0).

- The contribution from the hysteretic dissipated energy of the SDCs () increases as increases. Therefore, the variation in the calculated of Type Dp resulting from the ratio is less significant than that of Type O.

- The variation in the calculated of Type Dp resulting from the ratio is much less significant than that of Type O, even for = 0.25 (significant pinching). For 8story-Dp and = 0.25, the calculated corresponding to = 0 is 0.808 m2/s2, while the calculated corresponding to = 1 is 0.557 m2/s2 (68.9% of the value when = 0). Meanwhile, for 8story-Dp and = 1.00, the calculated corresponding to = 0 is 0.808 m2/s2 (the same value as for = 0.25) and the calculated corresponding to = 1 is 0.751 m2/s2 (92.9% of the value when = 0).

5.4. Summary of the Discussion

- A)

- In the case of RC MRFs without SDCs, the – plots obtained from the PDI and PMI analysis ( = 4) results are above the predicted seismic capacity curve. However, the – plots obtained from the PMI analysis ( = 6 and 8) results are below the predicted curve. The dependence of the – plots of RC MRFs without SDCs on is significant.

- B)

- In the case of RC MRFs with SDCs, the – plots obtained from the PDI and PMI analysis ( = 4) results agree very well with the predicted seismic capacity curve. In addition, the – plots obtained from the PMI analysis ( = 6 and 8) results are slightly below the predicted curve. The dependence of the – plots of the RC MRFs with SDCs on is limited.

- C)

- The ratio of the displacements in the positive and negative directions () increases as increases. In the case of RC MRFs without SDCs, decreases drastically as increases, especially when the pinching behavior of the RC members is significant. Meanwhile, in the case of RC MRFs with SDCs, the variation in resulting from is less significant.

6. Conclusions

- (i)

- In the case of RC MRFs without SDCs, the influence of on the – relationship is notable: decreases as increases. Meanwhile, in the case of RC MRFs with SDCs, the influence of on the – relationship is limited. This is because the energy dissipation capacity in a half cycle of the structural response decreases drastically in the case of RC MRFs without SDCs when the ratio of the displacements in the positive and negative directions is close to unity.

- (ii)

- In the case of RC MRFs without SDCs, the influence of the pinching behavior of RC members on the – relationship is small when is small. However, when is larger, the influence of the pinching behavior of RC members on the – relationship is notable. Conversely, the influence of the pinching behavior of RC members on the – relationship is limited in the case of RC MRFs with SDCs, regardless of .

- (iii)

- For RC MRFs with SDCs, the ratio of the cumulative strain energy of the RC MRFs () decreases and that of the SDCs () increases as increases. This trend is pronounced when the pinching behavior of the RC members is significant.

- (iv)

- The residual equivalent displacement ratio (), defined as the ratio of the residual equivalent displacement to the peak equivalent displacement (), obtained from the critical PMI analysis results is smaller than that obtained from the critical PDI analysis results. This difference is significant in the case of RC MRFs with SDCs. No regular trend was observed between the ratio and : the ratio may decrease when increases.

- How can the number of impulsive inputs as a substitute of recorded ground motions be determined? To the author’s best knowledge, the ratio of the equivalent velocities of the total input energy to the maximum momentary input energy () would be the best parameter for this purpose. If the number were chosen to obtain the ratio of the considered ground motion, the response obtained from the critical PMI analysis results could represent the peak and cumulative response of the structure subjected to the considered ground motion.

- Can the prediction procedure (Fujii and Shioda, 2023) properly predict the cumulative strain energies of RC MRFs and SDCs obtained by the critical PMI analysis results? As far as the peak response is concerned, the prediction procedure has been validated. However, the prediction procedure has not been validated for the cumulative response. In such a validation, the pinching behavior of the RC members and the number of impulsive inputs would be key parameters.

- Can the ICPMIA be extended for the case of seismic sequences? To the author’s best knowledge, the NTHA is the only method that analyzes the responses of structures subjected to seismic sequences. However, the results obtained from NTHA are too complex to derive general conclusions. This is because the NTHA results are intricately intertwined with the nonlinear structural characteristics and the ground motion characteristics. In the case of a seismic sequence, the complexity increases as a result of the mainshock-aftershock (or foreshock-mainshock) combined ground motions. The nonlinear characteristics of the damaged structure would likely be easier to understand using ICPMIA.

Data Availability Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflict of Interest

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| DB-MAP | displacement-based mode-adaptive pushover. |

| ICPMIA | incremental critical pseudo-multi impulse analysis. |

| MDOF | multi-degree-of-freedom. |

| MRF | moment-resisting frame. |

| NTHA | nonlinear time-history analysis. |

| PDI | pseudo-double impulse. |

| PMI | pseudo-multi impulse. |

| RC | reinforced concrete. |

| SDC | steel damper column. |

| SDOF | single-degree-of-freedom. |

References

- Akehashi, H., Takewaki, I. (2021). Pseudo-double impulse for simulating critical response of elastic-plastic MDOF model under near-fault earthquake ground motion. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering. 150, 106887.

- Akehashi, H., Takewaki, I. (2022). Pseudo-multi impulse for simulating critical response of elastic-plastic high-rise buildings under long-duration, long-period ground motion. The Structural Design of Tall and Special Buildings. 31(14), e1969.

- Akiyama, H. (1985). Earthquake resistant limit-state design for buildings. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

- Akiyama, H. (1999). Earthquake-resistant design method for buildings based on energy balance. Tokyo: Gihodo Shuppan.

- Benavent-Climent, A. (2011). An energy-based method for seismic retrofit of existing frames using hysteretic dampers. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, 31, 1385-1396.

- Benavent-Climent, A., Cahís, X., Zahran R. (2009). Exterior wide beam-column connections in existing RC frames subjected to lateral earthquake loads. Engineering Structures, 31, 1414-1424.

- Benavent-Climent, A., Cahís, X., Vico, J. M. (2010). Interior wide beam-column connections in existing RC frames subjected to lateral earthquake loading. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 8, 401-420.

- Benavent-Climent, A., Mollaioli, F. (Eds) (2021). Energy-Based Seismic Engineering, Proceedings of IWEBSE 2021. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Benavent-Climent, A., Mota-Páez, S. (2017). Earthquake retrofitting of R/C frames with soft first story using hysteretic dampers: Energy-based design method and evaluation. Engineering Structures, 137, 19-32.

- Benavent-Climent, A., Oliver-Saiz, E., Donaire-Ávila, J. (2024). Seismic retrofitting of RC frames combining metallic dampers and limited strengthening with FRP/SRP applying energy-based methods. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, 177, 108432.

- Dolšek, M., Fajfar, P. (August 2004). “IN2 – a simple alternative for IDA,” in Proceedings of the 13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Vancouver, Canada.

- Farrow, K.T.; Kurama, Y.C. (2003). SDOF demand index relationships for performance-based seismic design. Earthquake Spectra. 19(4), 799-838.

- Fujii, K. (2022). Peak and cumulative response of reinforced concrete frames with steel damper columns under seismic sequences. Buildings. 12, 275.

- Fujii, K. (2023), Energy-based response prediction of reinforced concrete buildings with steel damper columns under pulse-like ground motions. Frontiers in Built Environment. 9, 1219740.

- Fujii, K. (2024), Critical pseudo-double impulse analysis evaluating seismic energy input to reinforced concrete buildings with steel damper columns. Frontiers in Built Environment. 10, 1369589.

- Fujii, K., Kato, M. (2021). Strength balance of steel damper columns and surrounding beams in reinforced concrete frames. Earthquake Resistant Engineering Structures XIII, WIT Transactions on The Built Environment. 202, PII25–36.

- Fujii, K., Miyagawa, K. (June 2018). “Nonlinear seismic response of a seven-story steel reinforced concrete condominium retrofitted with low-yield-strength-steel damper columns” in Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Earthquake Engineering (Thessaloniki).

- Fujii, K., and Shioda, M. (2023). Energy-based prediction of the peak and cumulative response of a reinforced concrete building with steel damper columns. Buildings. 13, 401.

- Fujii, K., Sugiyama, H., Miyagawa, K. (2019). Predicting the peak seismic response of a retrofitted nine-storey steel reinforced concrete building with steel damper columns. Earthquake Resistant Engineering Structures XII, WIT Transactions on The Built Environment. 185, PII75–85.

- Gentry, T. R., Wight, J. K. (1994). Wide beam-column connections under earthquake-type loading. Earthquake Spectra, 10(4), 675-703.

- Hori, N., Iwasaki, T., Inoue, N. (January 2000). “Damaging properties of ground motions and response behavior of structures based on momentary energy response,” in Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Hori, N., Inoue, N. (2002). Damaging properties of ground motion and prediction of maximum response of structures based on momentary energy input. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics. 31, 1657–1679.

- Hoveidae, N., Radpour, S. (2021). Performance evaluation of buckling-restrained braced frames under repeated earthquakes. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering. 19, 241–262.

- Inoue, N., Wenliuhan, H., Kanno, H., Hori, N., Ogawa, J. (2000). “Shaking table tests of reinforced concrete columns subjected to simulated input motions with different time durations, “in Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Katayama, T., Ito, S., Kamura, H., Ueki, T., Okamoto, H. (January 2000). “Experimental study on hysteretic damper with low yield strength steel under dynamic loading,” in Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Kusuhara, F., Azukawa, K., Shiohara, H., Otani, S. (August 2004). “Tests of reinforced concrete Interior beam-column joint subassemblage with eccentric beams,” in Proceedings of the 13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Vancouver, Canada.

- Kusuhara F., Shiohara, H. (October 2008). “Tests of R/C beam-column joint with variant boundary conditions and irregular details on anchorage of beam bars,” in Proceedings of the 14th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Beijing, China.

- Kojima, K., Fujita, K., Takewaki, I. (2015). Critical double impulse input and bound of earthquake input energy to building structure. Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 5.

- Kojima, K., Takewaki, I. (2015a). Critical earthquake response of elastic–plastic structures under near-fault ground motions (Part 1: Fling-step input). Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 12.

- Kojima, K., Takewaki, I. (2015b). Critical earthquake response of elastic–plastic structures under near-fault ground motions (Part 2: Forward-directivity input). Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 13.

- Kojima, K., Takewaki, I. (2015c). Critical input and response of elastic–plastic structures under long-duration earthquake ground motions. Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 15.

- Mota-Páez, S., Escolano-Margarit, D., Benavent-Climent, A. (2021). Seismic response of RC frames with a soft first story retrofitted with hysteretic dampers under near-fault earthquakes, Applied Sciences. 2021, 11, 1290.

- Mukoyama, R., K. Fujii, K., Irie, C., Tobari, R., Yoshinaga, M., K. Miyagawa, K. (October 2021). “Displacement-controlled Seismic Design Method of Reinforced Concrete Frame with Steel Damper Column,” in Proceedings of the 17th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Sendai, Japan.

- Ruiz-García, J., Negrete-Manriquez, J. C. (2011). Evaluation of drift demands in existing steel frames under as-recorded far-field and near-fault mainshock–aftershock seismic sequences. Engineering Structures. 33. 621-634.

- Ruiz-García, J. (2012a). Mainshock-Aftershock Ground Motion Features and Their Influence in Building's Seismic Response. Journal of Earthquake Engineering. 16(5), 719-737.

- Ruiz-García, J. (2012b). “Issues on the Response of Existing Buildings Under Mainshock-Aftershock Seismic Sequences,” in Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal.

- Shirai, K., Okano, H., Nakanishi, Y., Takeuchi, T., Sasamoto, K., Sadamoto, M., Kusunoki, K. (2024). Evaluation of response, damage, and repair cost of reinforced concrete super high-rise buildings subjected to large-amplitude earthquakes. Japan Architectural Review. 7, e12418.

- Tesfamariam, S. Goda, K. (2015). Seismic performance evaluation framework considering maximum and residual inter-story drift ratios: application to non-code conforming reinforced concrete buildings in Victoria, BC, Canada. Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 18.

- Toyoda S, Kuramoto H, Katsumata H, Fukuyama H. (2014). Earthquake response analysis of a 20-story RC building under long period seismic ground motion. Journal of Structural and Construction Engineering (Transactions of AIJ). 79(702), 1167-1174. (in Japanese).

- Vamvatsikos, D., Cornell, C. A. (2002). Incremental dynamic analysis. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics. 31, 491–514.

- Varum, H., Benavent-Climent, A., Fabrizio Mollaioli, F. (eds) (2023). Energy-Based Seismic Engineering, Proceedings of IWEBSE 2023. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Wada, A., Huang, YH., Iwata, M. (2000). Passive damping technology for buildings in Japan. Progress in Structural Engineering and Materials. 2(3), 335-350.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).