Submitted:

12 January 2024

Posted:

16 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

- In the presented procedure (Fujii and Shioda, 2023), the accuracy of the equivalent velocity of the maximum momentary input energy of the first modal response ()–equivalent displacement of the first modal response () relationship is essential for high quality predictions of the peak displacement. Accordingly, a monotonic pushover analysis was performed to evaluate the – relationship. However, the strain hardening effect observed in low-yield steel shear panels subjected to cyclic loading (Nakashima, 1995) cannot be considered in a monotonic pushover analysis.

- For the prediction of the peak equivalent displacement () and cumulative input energy of the first modal response, the equivalent velocities of the maximum momentary input energy () and the total input energy () are predicted from the linear elastic spectrum (the and spectra, respectively). In the presented procedure (Fujii and Shioda, 2023), the effective period of the first modal response () calculated from the predicted – relationship is used for the predictions of and . Although the accuracies of the predicted and values have been examined by comparing the predicted results with the NTHA results, the accuracy of has not yet been examined. The response period of the first modal response (), which is defined as twice ( where is the interval of a half cycle of the structural response), is a good index for evaluating in NTHA results. However, the value of obtained from the NTHA results is unstable because of the complexity of the characteristics of ground motions and the influence of the higher modal responses of a structure.

1.2. Objectives

- (i)

- What is the – relationship when considering the response of an RC MRF with SDCs subjected to critical PDI input? Does it agree with the predicted – relationship from the simplified equation proposed in the author’s previous study (Fujii and Shioda, 2023)?

- (ii)

- What is the relationship between the response period () and the effective period () calculated from and in the case of an RC MRF with SDCs subjected to critical PDI input?

2. Critical PDI Analysis

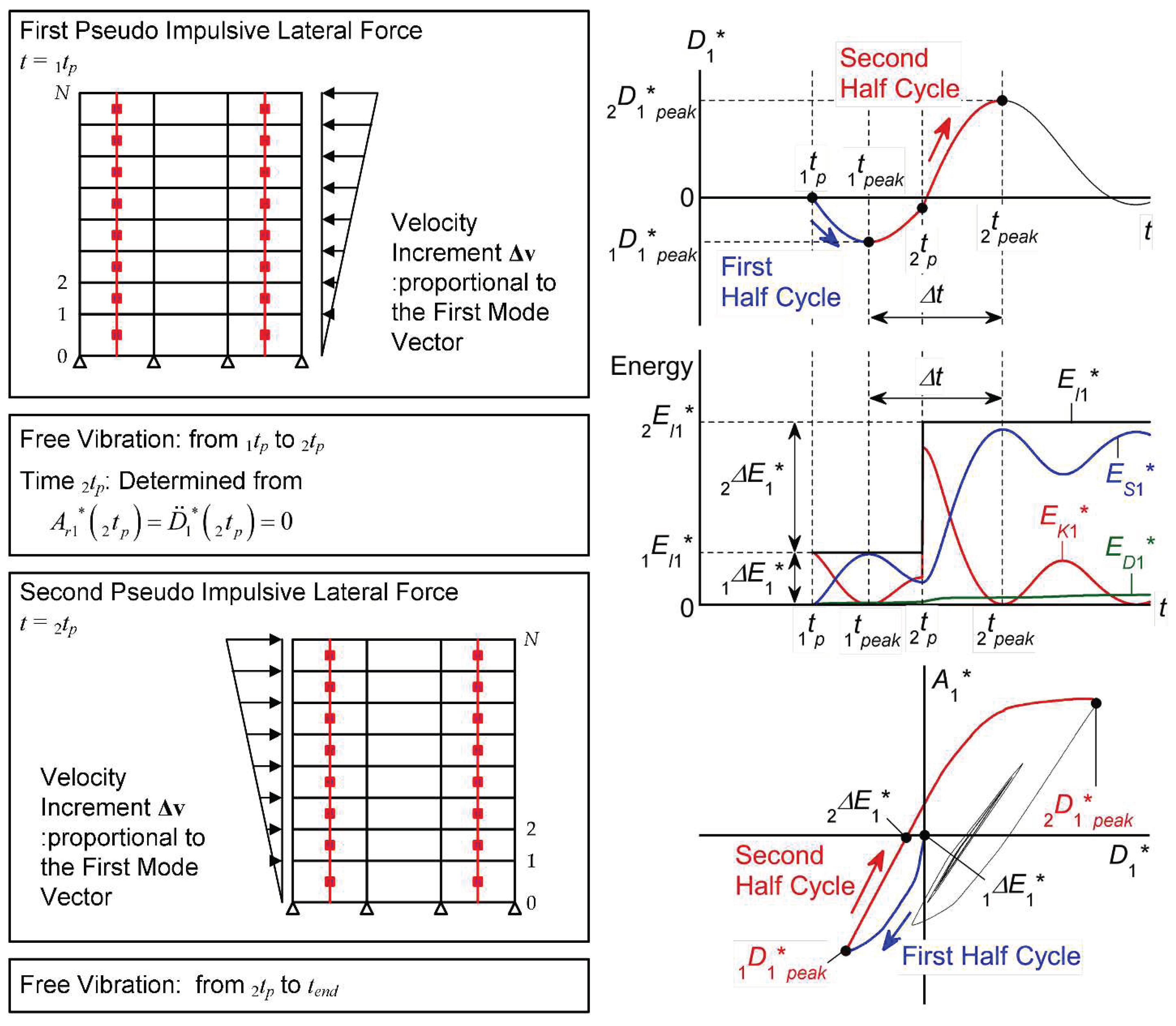

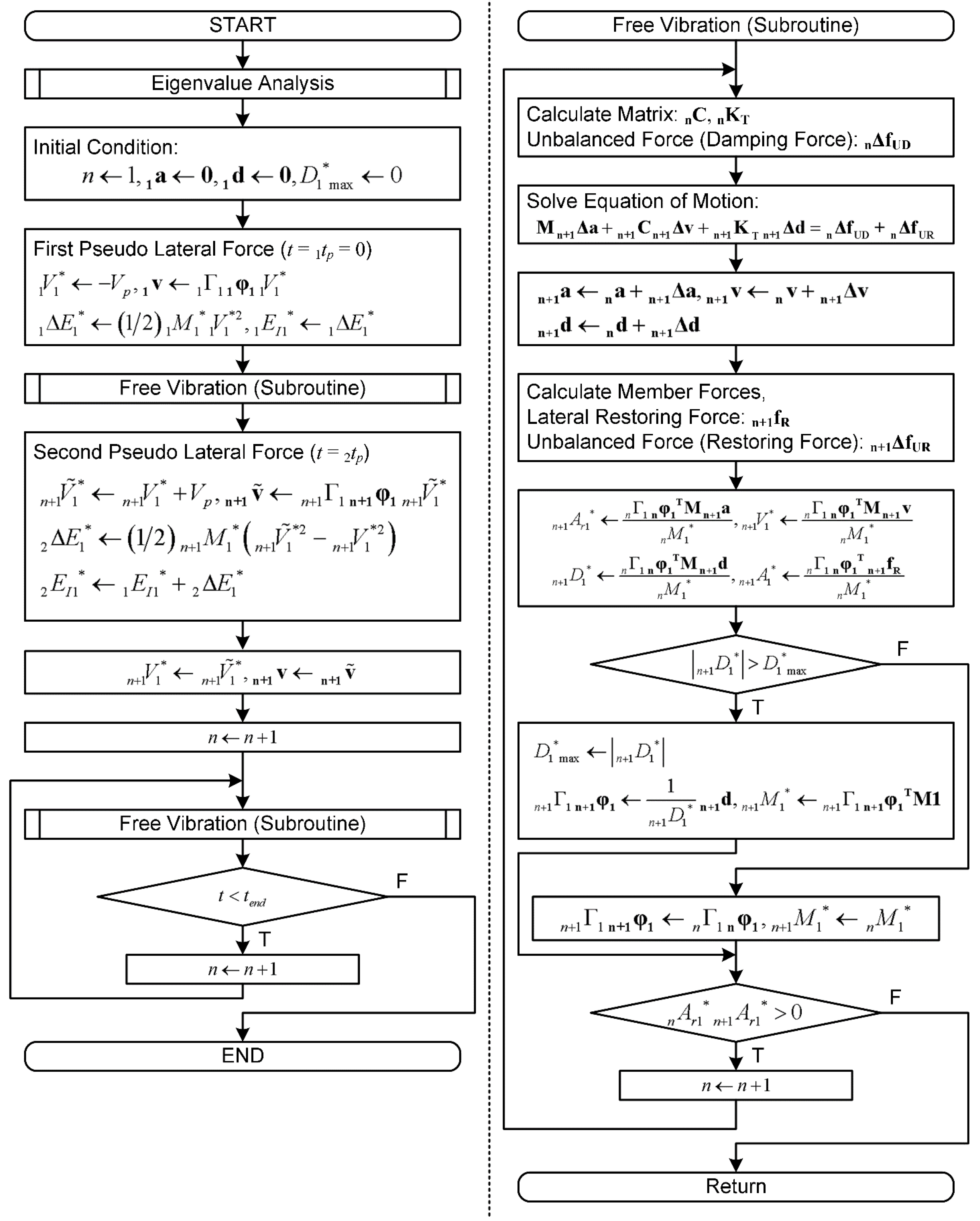

2.1. Outline of the Critical PDI Analysis

2.1.1. First pseudo impulsive lateral force

2.1.2. Free vibration after the first pseudo impulsive lateral force

2.1.3. Second pseudo impulsive lateral force

2.1.4. Free vibration after the second pseudo impulsive lateral force

2.2. Momentary Input Energy in the Critical PDI Analysis

2.3. Analysis Flow

3. Analysis Data and Methods

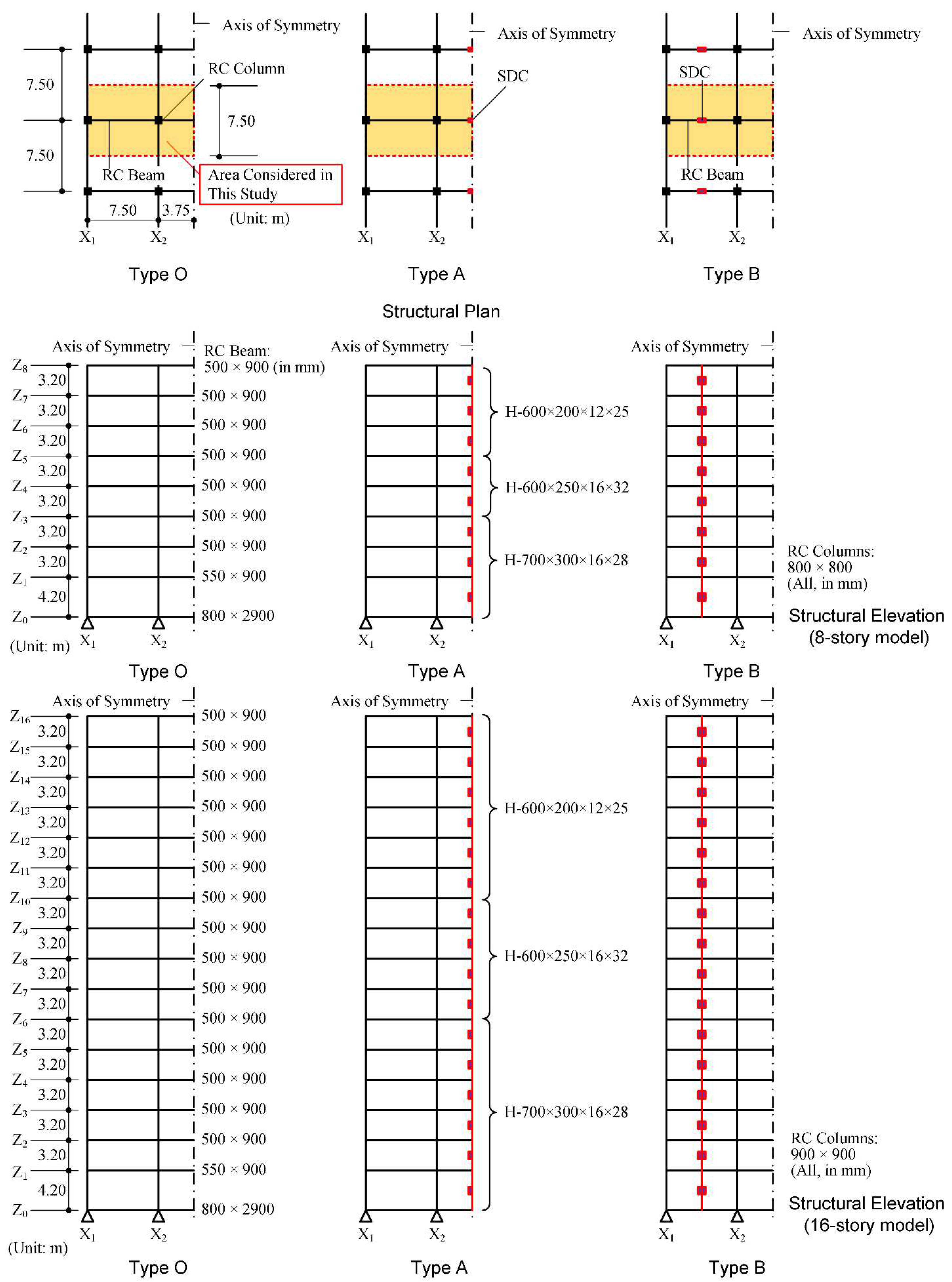

3.1. Building Data

- The “yield displacement” of RCF () in Type A and B models is smaller than that in Type O models. The equivalent drift ratio at the “yielding of RCF” () of the Type O 8-story model is 1/170, while those of the Type A and B models are 1/196 and 1/205, respectively. Similarly, the ratio of the Type O 16-story model is 1/187, while those of the Type A and B models are 1/215 and 1/218, respectively. This is because of the shortening of the beam span resulting from the presence of the SDCs.

- The “yield acceleration” of RCF () in the Type A and B models is nearly the same as that in the Type O models. In case of the 8-story models, the values of the Type O, A, and B models are 2.561 m/s2, 2.567 m/s2, and 2.596 m/s2, respectively. Similarly, in the case of the 16-story models, the values of the Type O, A, and B models are 1.288 m/s2, 1.304 m/s2, and 1.326 m/s2, respectively.

- The “yield acceleration” of SDC () in the Type B models is approximately twice of that in the Type A models. The ratio of the “yield acceleration” of SDC to that of RCF () of the Type A 8-story model is 0.234, while that of the Type B model is 0.458. Similarly, the ratio of the Type A 16-story model is 0.242, while that of the Type B model is 0.471.

- The ratio of the “yield displacement” of SDC to that of RCF () of the 8-story models is smaller than that of the 16-story models. For the 8-story models, the ratios of the Type A and B models are 0.563 and 0.598, respectively. Meanwhile for the 16-story models, the ratios of the Type A and B models are 0.731 and 0.780, respectively.

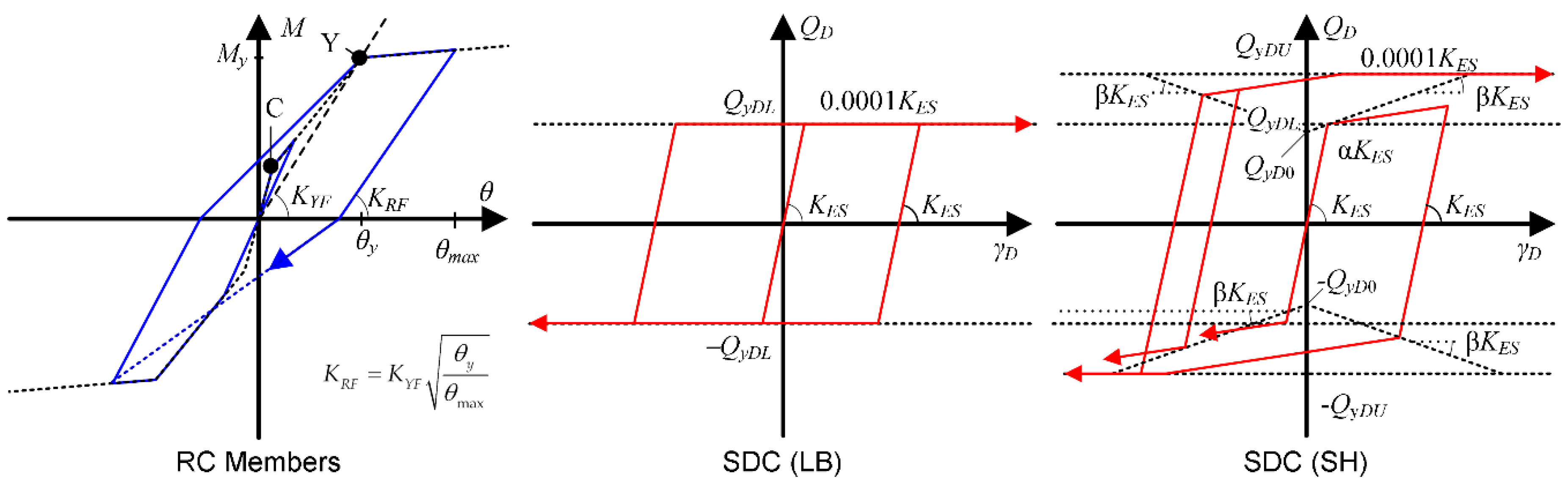

3.2. Analysis Method

4. Analysis Results

4.1. Response of the Overall Building Model

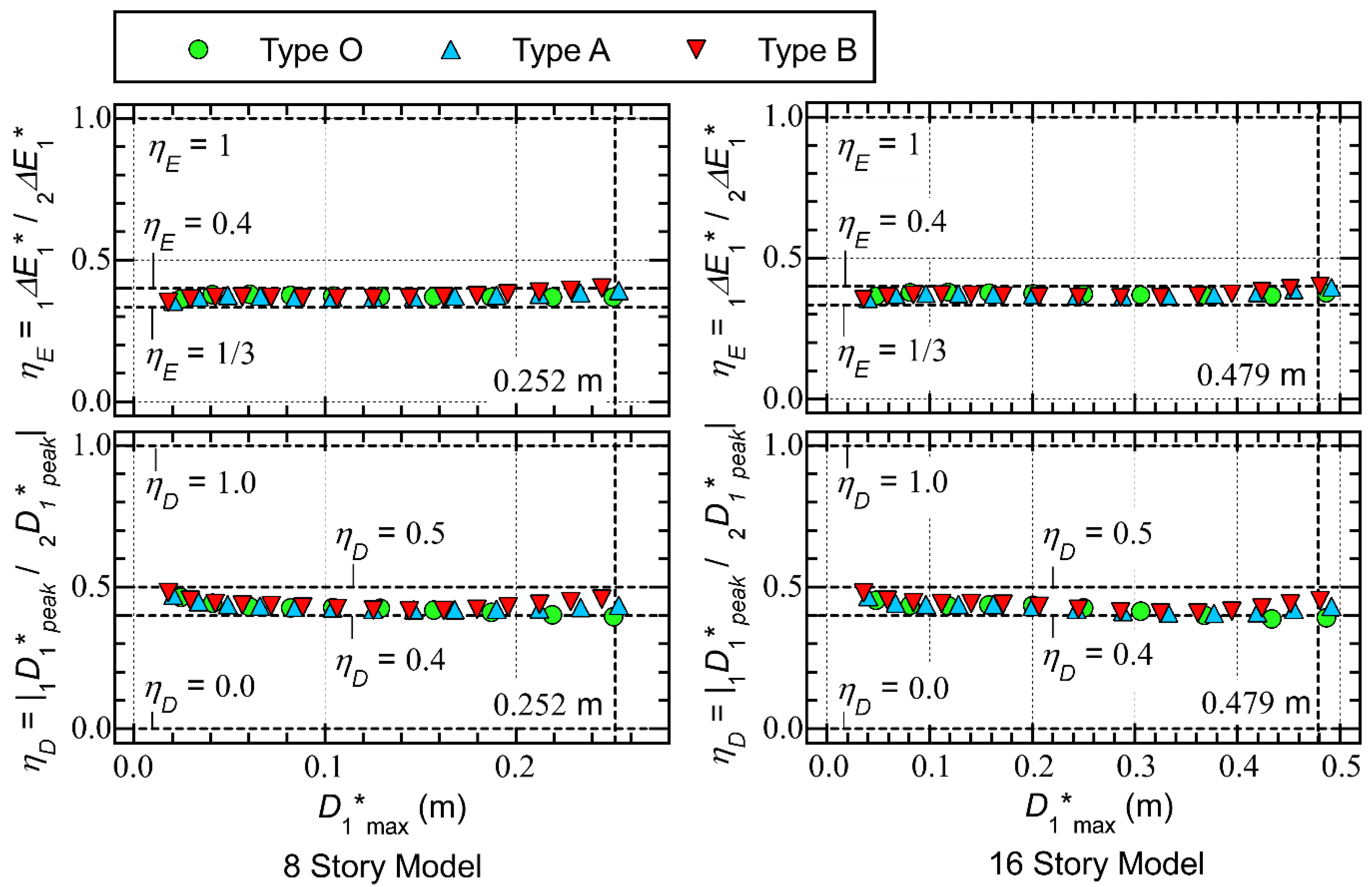

- The seismic intensity parameters (, , and ) increase as increases. The – and – curves are very similar to the – curve of the same model: the ratio ranges from 1.8 to 2.0, while the ratio ranges from 1.5 to 1.7. The differences in the and ratios between models are very small.

- For the same value of , the values of the Type B models are the smallest while those of the Type O models are the largest. Comparing the values of the 8-story models considering the case where = 0.55 m/s, the value for the Type O models is 0.252 m, while those for the Type A and B models are 0.190 m (−24.6 %) and 0.162 m (−35.7 %), respectively. Similarly, comparing the values of the 16-story models considering the case where = 0.55 m/s, the value for the Type O models is 0.487 m, while those for the Type A and B models are 0.377 m (−22.6 %) and 0.325 m (−33.3 %), respectively.

- In all cases, the ratio of the kinetic energy () is close to zero.

- For the Type O 8-story model, the ratio is close to 0.8 when is smaller than 0.111 m (= ). Meanwhile, the ratio decreases and the ratio increases as increases when is larger than 0.111 m. When is 0.251 m, is 0.148 while is 0.852. Because no SDCs are installed in the Type O models, the ratio is zero.

- For the Type A 8-story model, the ratio increases as increases when is larger than 0.054 m (= ). The ratio increases as increases when is larger than 0.096 m (= ). Meanwhile, the ratio decreases as increases. When is 0.254 m, is 0.097 while is 0.553 and is 0.350.

- For the Type B 8-story model, similar observations can be made as for the Type A 8-story model. When is 0.250 m, is 0.084 while is 0.447 and is 0.467.

- For the Type O 16-story model, similar observations can be made as for the Type O 8-story model. When is 0.487 m, is 0.129 while is 0.871. Because no SDCs are installed in the Type O models, the ratio is zero.

- For the Type A 16-story model, the ratio increases as increases when is larger than 0.122 m (= ). The ratio increases as increases when is between 0.167 m (= ) and 0.332 m. However, the ratio is nearly constant when is larger than 0.332 m. When is 0.492 m, is 0.091 while is 0.600 and is 0.310.

- For the Type B 16-story model, similar observations can be made as for the Type A 16-story model. When is 0.480 m, is 0.084 while is 0.499 and is 0.417.

- In all models, larger equivalent displacements occur in the positive direction: is larger than . This means that the peak equivalent displacement of the first modal response over the course of the entire seismic event () occurs at the end of the second half cycle of the response, where the momentary energy input occurs.

- For the Type O models (both 8- and 16-story), the – curves obtained from the pushover analysis results (black dotted curve) agree very well with the hysteresis loops obtained via the critical PDI analyses: the points at the local peak response ( and ) are on the – curves obtained from the pushover analysis results.

- For the Type A and B models (both 8- and 16-story), the – curves obtained from the pushover analyses are slightly different from the hysteresis loops obtained via the critical PDI analyses: the points at the second local peak response () are above the – curve obtained from the pushover analysis results. For the 8-story models, the ratios of the values obtained from the critical PDI analysis and the pushover analysis at the point are 1.086 for the Type A model and 1.141 for the Type B models. Similary, for the 16-story models, the ratios of the values from the critical PDI analysis and the pushover analysis are 1.083 for the Type A model and 1.149 for the Type B model.

- In all models, the ratio is nearly constant: most of the plots are distributed within a narrow range between 1/3 and 0.4.

- In all models, the ratio is nearly constant: most of the plots are distributed within a narrow range between 0.4 and 0.5.

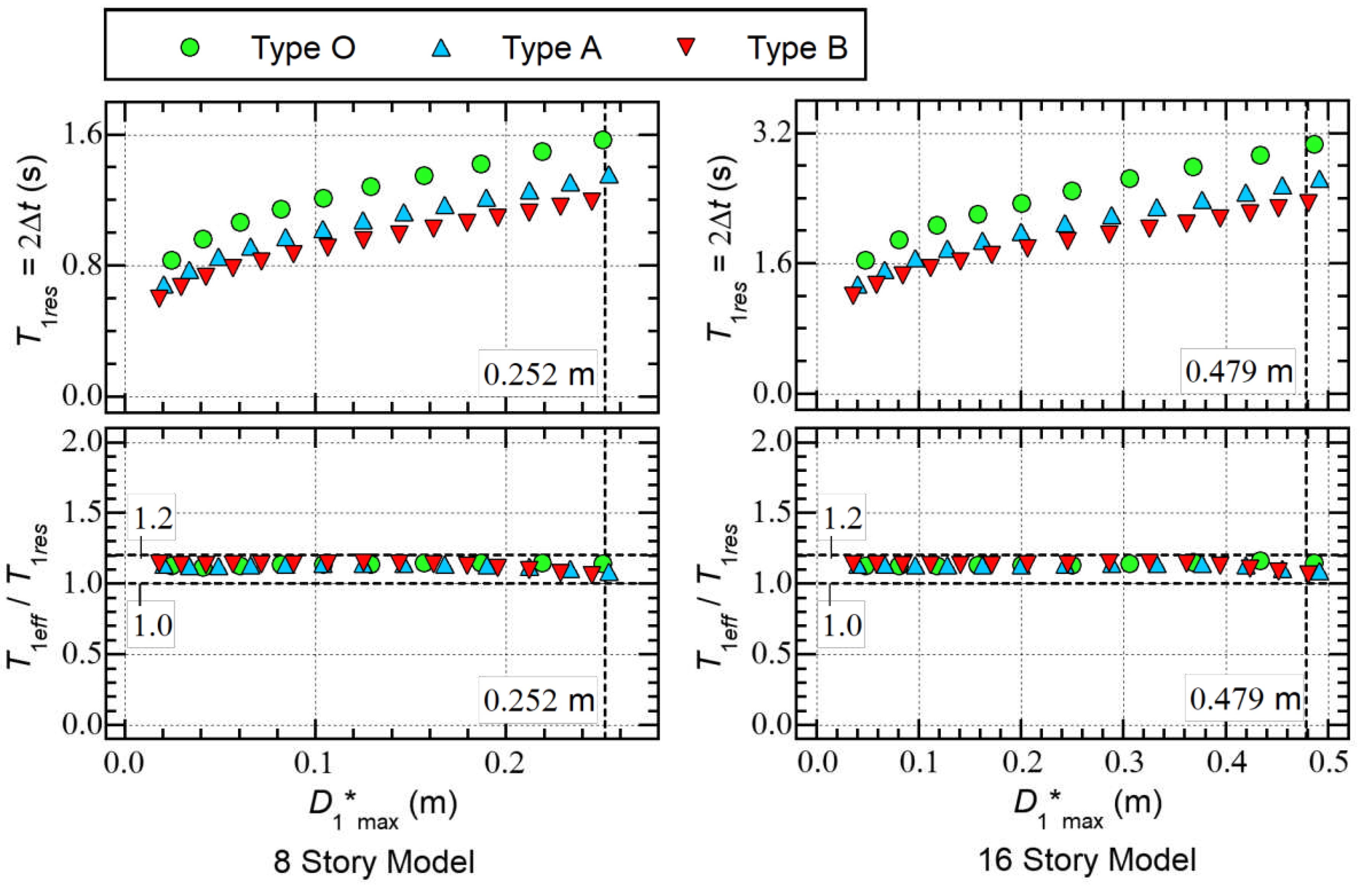

- In all models, increases as increases.

- When comparing in the case of similar , of the Type O models is the largest while that of the Type B models is the smallest. This means that becomes smaller as the number of SDCs increases.

- In all models, the ratio is nearly constant: all of the plots are distributed within a narrow range between 1.0 and 1.2.

4.2. Local Response

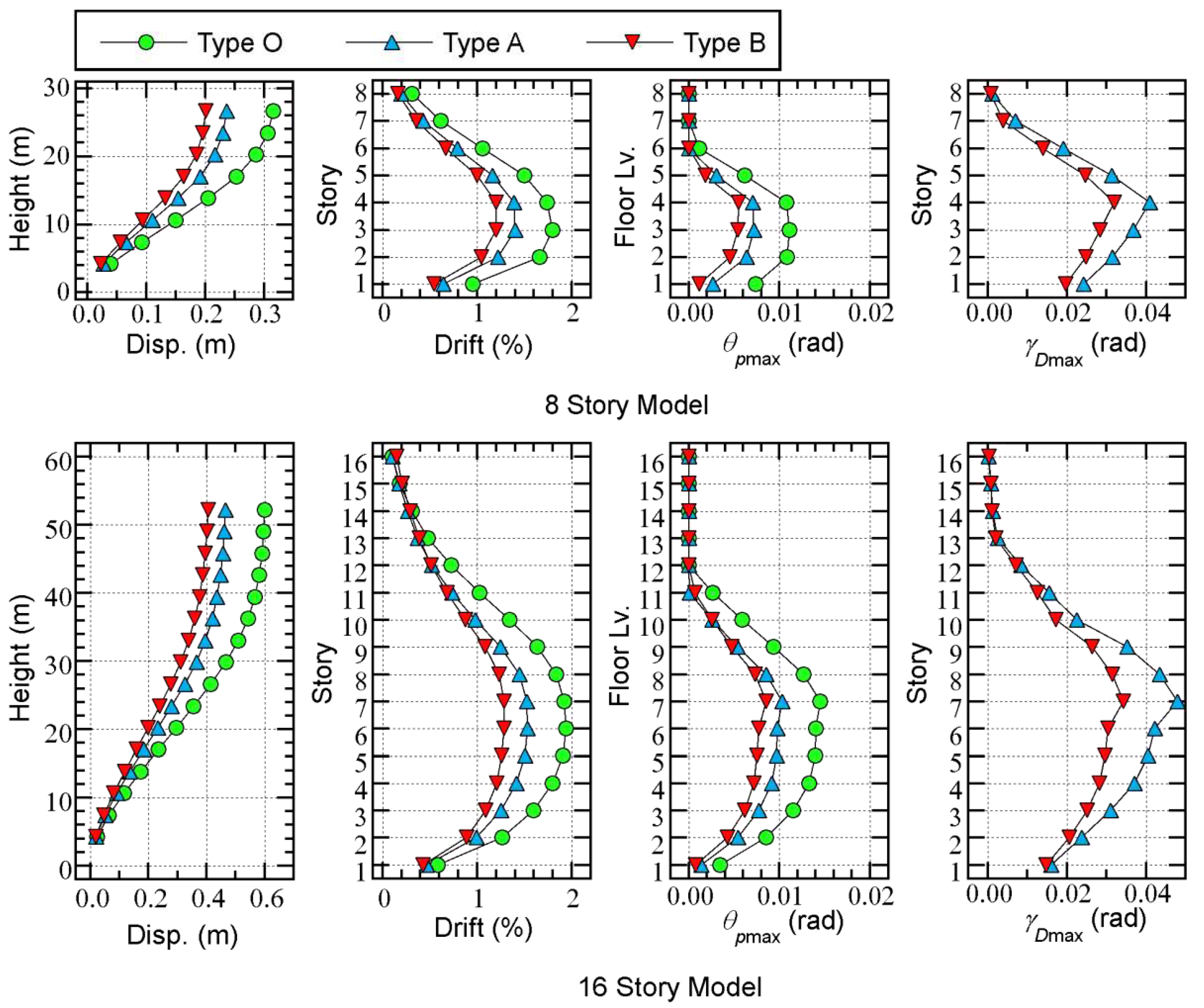

- For both the 8- and 16-story models, the responses of the Type O models are the largest, while those of the Type B models are the smallest.

- For the 8-story models, the largest peak story drift is observed at the third floor level. The largest is observed at the third or forth floor levels. The largest is observed at the forth floor level.

- For the 16-story models, the largest peak story drift is observed at the sixth or seventh floor levels. The largest is observed at the seventh floor level. The largest is observed at the seventh floor level.

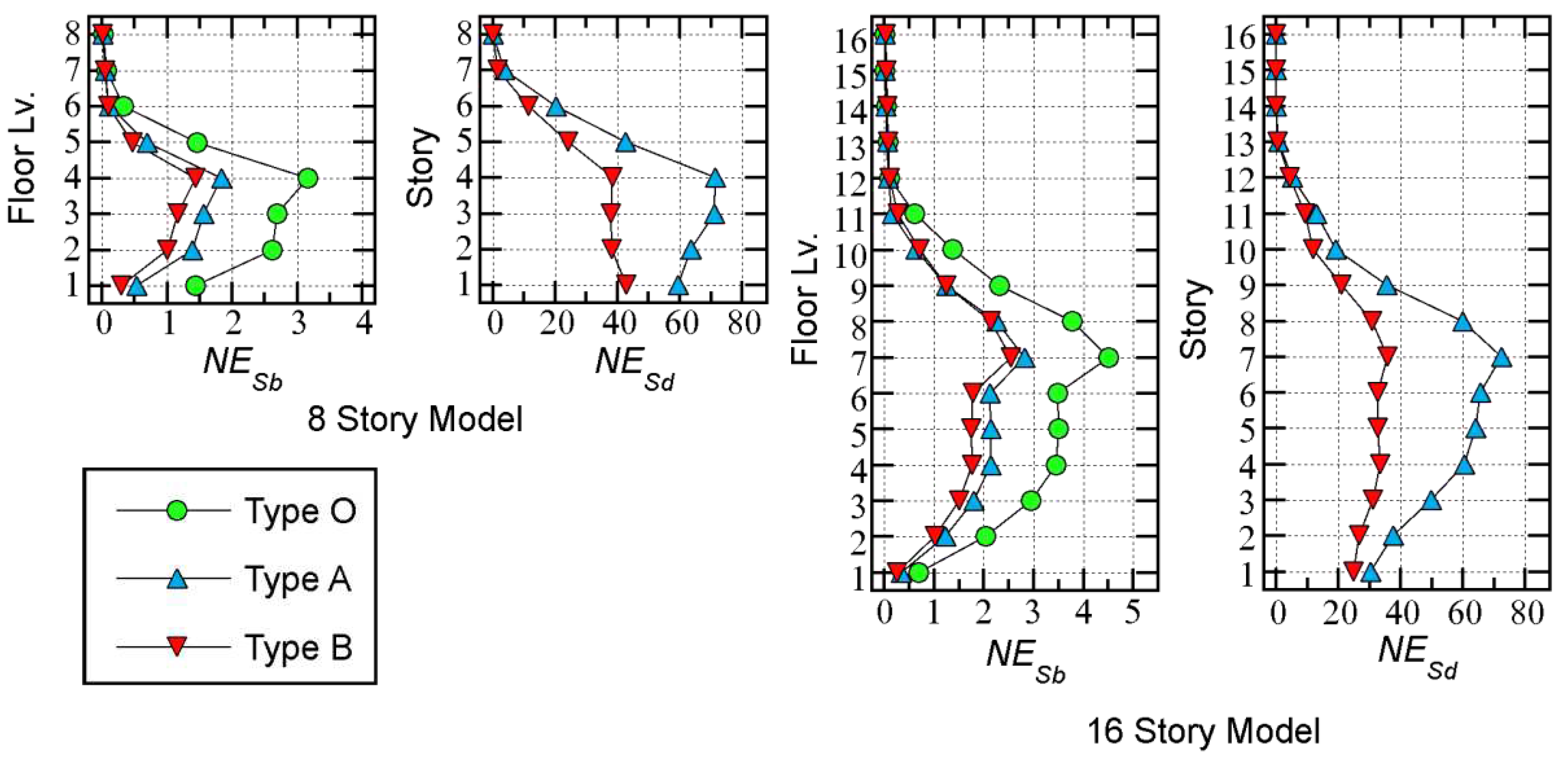

- For both 8- and 16-story models, the values of the Type O models are the largest, while those of the Type B models are the smallest. The largest values are observed at the forth floor level in the 8-story models and at the seventh floor level in the 16-story models.

- For both the 8- and 16-story models, the values of the Type A models are larger than those of the Type B models. In the 8-story models, the largest is observed at the forth floor level in the Type A models, while it is observed at the first floor level in the Type B models. In the 16-story models, the largest is observed at the seventh floor level in both model types.

4.3. Summary of the Analysis Results

- A)

- In the critical PDI analysis results shown herein, the peak equivalent displacement of the first modal response over the course of the entire seismic event () occurs at the end of the second half cycle of the response, when the second pseudo impulsive lateral force acts. The momentary input energy corresponding to the second pseudo impulsive lateral force () is larger than that corresponding to the first pseudo impulsive lateral force ().

- B)

- The equivalent acceleration ()–equivalent displacement () curve obtained from the pushover analysis results agrees very well with the hysteresis loop (the – relationship) obtained by the critical PDI analysis in the case of the Type O models. Meanwhile, in the case of the models with SDCs, the – curve obtained from the pushover analysis is slightly different from the hysteresis loop obtained by the critical PDI analysis. This is due to the strain hardening effect of the damper panel.

- C)

- The ratio of the the effective period of the first modal response (), calculated from Equation (42), to the response period of the first modal response (), , is nearly constant: the ratio is within a narrow range between 1.0 and 1.2.

5. Comparisons with the Predicted Results

5.1. Bare RC Frame Models

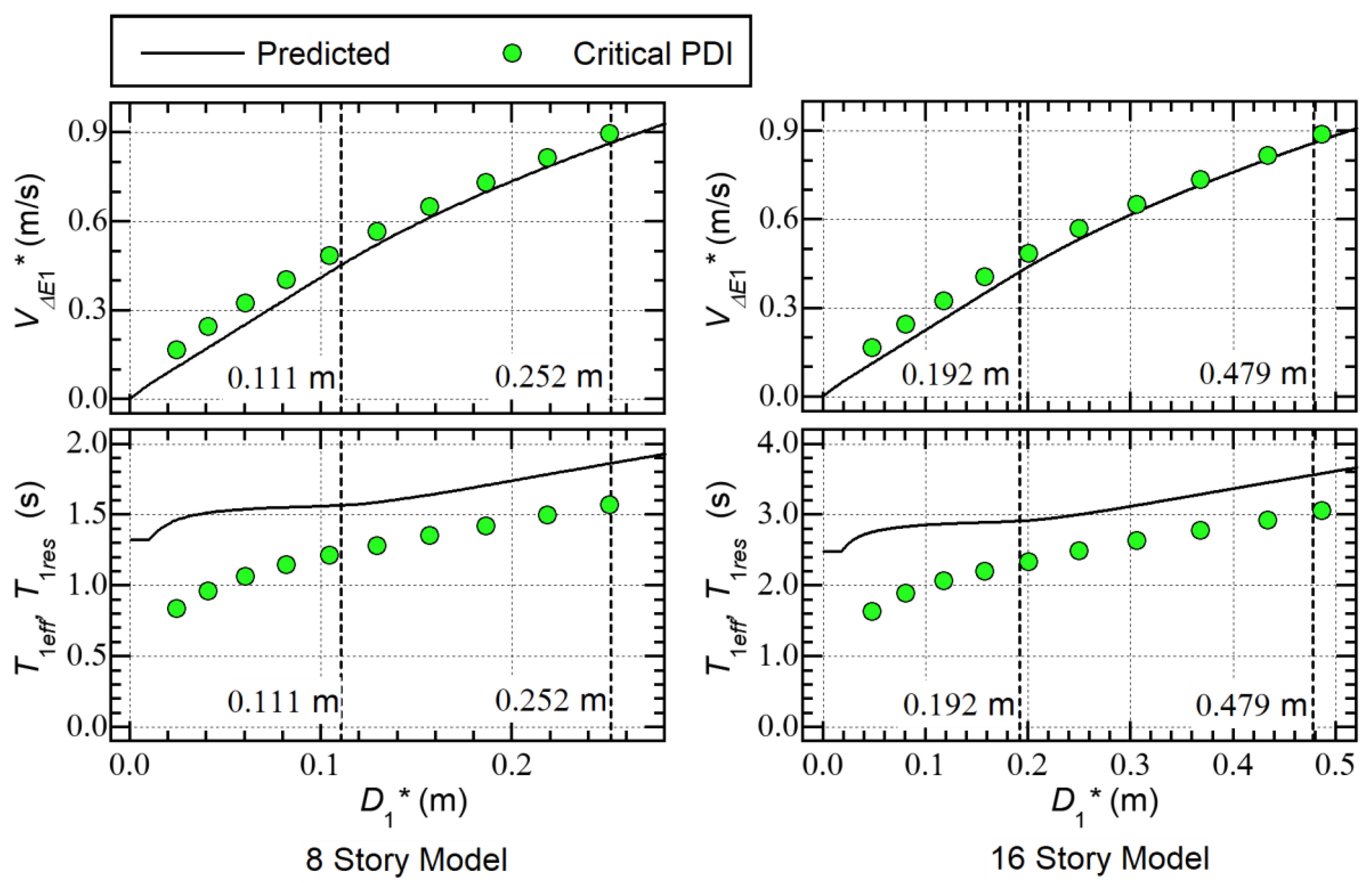

- The predicted – curves agree well with the – plots obtained from the critical PDI results. More specifically, the predicted – curve of the 8-story model agrees very well with the critical PDI results when is larger than 0.111 m (= ). Similarly, the predicted – curve of the 16-story model agrees very well with the critical PDI results when is larger than 0.192 m.

- The predicted – curves are above the – plots obtained from the critical PDI results, although its trend is similar. The predicted – curves show a gradual increase in as increases, which is consistent with the – plots. However, the difference between and becomes significant when is small.

5.2. RC Frame Models with SDCs

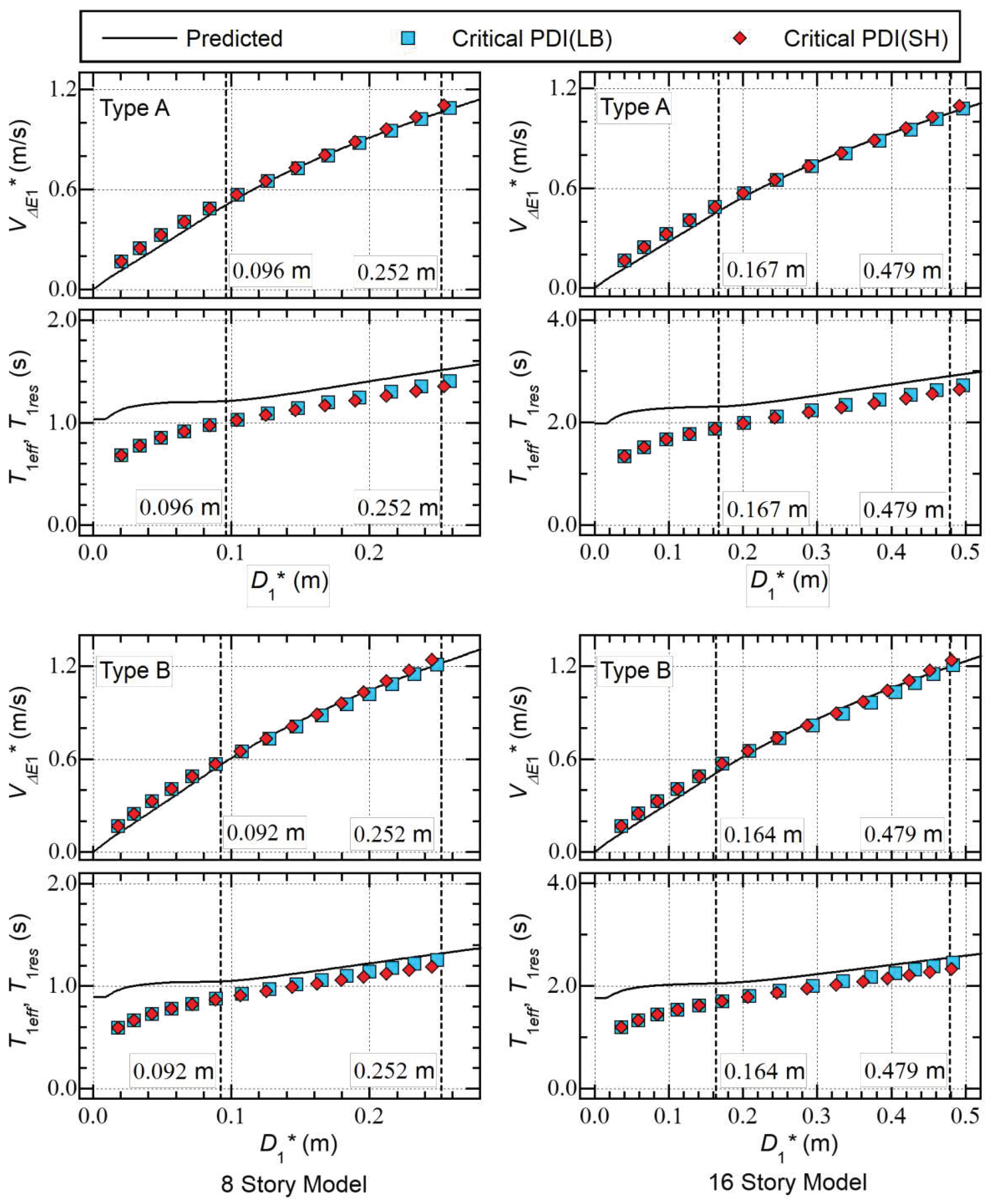

- As far as the – and – plots are concerned, the differences between the LB (without strain hardening) and SH (with strain hardening) plots are very small in the critical PDI analysis results shown herein.

- The predicted – curves agree well with the – plots obtained from the critical PDI results for all models shown herein.

- The predicted – curves are above the – plots obtained from the critical PDI results, and the difference between the predicted – curves and the – plots decreases as increases.

5.3. Discussion

- A)

- The predicted – curves agree well with the – plots obtained from the critical PDI results for all models shown herein.

- B)

- The predicted – curves are slightly above the – plots obtained from the critical PDI results. Although their trends are similar, the predicted – curves show a gradual increase in as increases, which is consistent with the – plots.

- C)

- The influence of the strain hardening of the damper panels on the – and – plots of the RC MRF models with SDCs is negligibly small.

6. Conclusions

- The equivalent acceleration ()–equivalent displacement () curves obtained from the pushover analysis results agree very well with the hysteresis loops (– relationship) obtained by the critical PDI analysis in the case of models without SDCs. In the case of models with SDCs, the – curve obtained from the pushover analysis differs slightly from the hysteresis loop obtained by the critical PDI analysis.

- The effective period of the first modal response (), calculated from the equation of the peak equivalent displacement () and the equivalent velocity of the maximum momentary input energy (), is clearly related to the response period (); the ratio is within a narrow range between 1.0 and 1.2.

- The predicted – curves agree well with the – plots obtained from the critical PDI results for all models shown herein. Meanwhile, the predicted – curves are slightly above the – plots obtained from the critical PDI results. Although their trends are similar, the predicted – curves show a gradual increase in as increases, which is consistent with the – plots.

- The influence of the strain hardening of the damper panels on the – and – plots of the RC MRF models with SDCs is negligibly small.

- What is the dependence of the – curve on the number of impulsive inputs? It is expected that the ratio of the amplitude of in the positive and negative directions changes as the number of impulsive inputs increases. Therefore, the relationship between the increment of the energy input in each half cycle and the local peak equivalent displacement should vary depending on the number of impulsive inputs.

- Can the distribution of the cumulative strain energy of the SDCs in the critical PDI analysis at each floor level be properly evaluated from the pushover analysis results? Because the pushover analysis cannot consider the strain hardening effect, the distribution of the deformation of the SDCs may be different from the critical PDI analysis results. It is expected that the influence of the strain hardening effect on the distribution of the cumulative strain energy of the SDCs may be significant when the number of impulsive inputs increases.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Angelucci, G., Quaranta, G., Mollaioli, F., Kunnath, SK. (2023a). “Correlation between seismic energy demand and damage potential under pulse-like ground motions”, In: Varum, H., Benavent-Climent, A., Mollaioli, F. (eds) Energy-Based Seismic Engineering. IWEBSE 2023. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, vol 236. Springer, Cham.

- Angelucci, G., Mollaioli, F., Quaranta, G. (2023b). Correlation between energy and displacement demands for infilled reinforced concrete frames. Frontiers in Built Environment. 9, 1198478. [CrossRef]

- Akehashi, H., Takewaki, I. (2021). Pseudo-double impulse for simulating critical response of elastic-plastic MDOF model under near-fault earthquake ground motion. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering. 150, 106887. [CrossRef]

- Akehashi, H., Takewaki, I. (2022). Pseudo-multi impulse for simulating critical response of elastic-plastic high-rise buildings under long-duration, long-period ground motion. The Structural Design of Tall and Special Buildings. 31(14), e1969. [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H. (1985). Earthquake Resistant Limit-State Design for Buildings. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

- Akiyama, H. (August 1988). “Earthquake resistant design based on the energy concept”, in Proceedings of the 9th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Tokyo-Kyoto, Japan.

- Akiyama, H. (1999). Earthquake-Resistant Design Method for Buildings Based on Energy Balance. Tokyo: Gihodo Shuppan.

- Benavent-Climent, A., Akiyama, H., López-Almansa, F., Pujades, LG. (2004). Prediction of ultimate earthquake resistance of gravity-load designed RC buildings. Engineering Structures. 26. 1103-1103. [CrossRef]

- Benavent-Climent, A. (2011). A seismic index method for vulnerability assessment of existing frames: application to RC structures with wide beams in Spain. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 9. 491-517. [CrossRef]

- Decanini, L., Mollaioli, F., Saragoni, R. (January 2000). “Energy and displacement demands imposed by near-source ground motions,” in Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Elwood, K.J.; Sarrafzadeh, M.; Pujol, S.; Liel, A.; Murray, P.; Shah, P.; Brooke, N.J. (April 2021). “Impact of prior shaking on earthquake response and repair requirements for structures—Studies from ATC-145,” in Proceedings of the NZSEE 2021 Annual Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand.

- Fajfar, P. (1992). Equivalent ductility factors, taking into account low-cycle fatigue. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics. 21, 837–848. [CrossRef]

- Fajfar, P., Gaspersic, P. (1996). The N2 method for the seismic damage analysis of RC buildings. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics.25, 31-46. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K. (2014). Prediction of the largest peak nonlinear seismic response of asymmetric buildings under bi-directional excitation using pushover analyses. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering. 12, 909–938. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K., Miyagawa, K. (June 2018). “Nonlinear seismic response of a seven-story steel reinforced concrete condominium retrofitted with low-yield-strength-steel damper columns” in Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Earthquake Engineering (Thessaloniki).

- Fujii, K., Sugiyama, H., Miyagawa, K. (2019). Predicting the peak seismic response of a retrofitted nine-storey steel reinforced concrete building with steel damper columns. Earthquake Resistant Engineering Structures XII, WIT Transactions on The Built Environment. 185, PII75–85.

- Fujii, K., Kanno, H., and Nishida, T. (2019). Formulation of the time-varying function of momentary energy input to a SDOF system by Fourier series. Journal of Japan Association for Earthquake Engineering. 19, 247–266. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K., Murakami, Y. (September 2021). “Bidirectional momentary energy input to a one-mass two-DOF system. In Proceedings of the 17th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering,” Sendai, Japan.

- Fujii, K. (2021). Bidirectional seismic energy input to an isotropic nonlinear one-mass two-degree-of-freedom system. Buildings. 11, 143. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K. (2022). Peak and cumulative response of reinforced concrete frames with steel damper columns under seismic sequences. Buildings. 12, 275. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K., and Shioda, M. (2023). Energy-based prediction of the peak and cumulative response of a reinforced concrete building with steel damper columns. Buildings. 13, 401. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K. (2023), Energy-based response prediction of reinforced concrete buildings with steel damper columns under pulse-like ground motions. Frontiers in Built Environment. 9, 1219740. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K. (July 2023). “Equivalent Number of Cycles Formulation for a Base-Isolated Building,” In: Varum, H., Benavent-Climent, A., Mollaioli, F. (eds) Energy-Based Seismic Engineering. IWEBSE 2023. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, vol 236. Springer, Cham.

- Gaspersic, P.; Fajfar, P.; Fischinger, M. (July 1992). “An approximate method for seismic damage analysis of buildings,” in Proceedings of the 10th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Madrid, Spain.

- Hori, N., Iwasaki, T., Inoue, N. (January 2000). “Damaging properties of ground motions and response behavior of structures based on momentary energy response,” in Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Hori, N., Inoue, N. (2002). Damaging properties of ground motion and prediction of maximum response of structures based on momentary energy input. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics. 31, 1657–1679. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, N., Wenliuhan, H., Kanno, H., Hori, N., Ogawa, J. (2000). “Shaking table tests of reinforced concrete columns subjected to simulated input motions with different time durations, “ in Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Kalkan, E., Kunnath, SK. (2007). Effective Cyclic Energy as a Measure of Seismic Demand, Journal of Earthquake Engineering, 11(5), 725-751. [CrossRef]

- Katayama, T., Ito, S., Kamura, H., Ueki, T., Okamoto, H. (January 2000). “Experimental study on hysteretic damper with low yield strength steel under dynamic loading,” in Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Kojima, K., Fujita, K., Takewaki, I. (2015). Critical double impulse input and bound of earthquake input energy to building structure. Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 5. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K., Takewaki, I. (2015a). Critical earthquake response of elastic–plastic structures under near-fault ground motions (Part 1: Fling-step input). Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K., Takewaki, I. (2015b). Critical earthquake response of elastic–plastic structures under near-fault ground motions (Part 2: Forward-directivity input). Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K., Takewaki, I. (2015c). Critical input and response of elastic–plastic structures under long-duration earthquake ground motions. Frontiers in Built Environment. 1, 15. [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, G., M., Cosenza, E. (2003). Cumulative demand of the earthquake ground motions in the near source. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics. 32, 1853–1865. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, M. (1995). Strain-hardening behaviour of shear panels made of low-yield steel 1: test. Journal of Structural Engineering, ASCE. 121(12), 1742-1749. [CrossRef]

- Mollaioli, F., Bruno, S., Decanini, L., Saragoni, R. (2011). Correlations between energy and displacement demands for performance-based seismic engineering. Pure and Applied Geophysics. 168, 237-259. [CrossRef]

- Mota-Páez, S., Escolano-Margarit, D., Benavent-Climent, A. (2021). Seismic response of RC frames with a soft first story retrofitted with hysteretic dampers under near-fault earthquakes, Applied Sciences. 2021, 11, 1290. [CrossRef]

- Mukoyama, R., K. Fujii, K., Irie, C., Tobari, R., Yoshinaga, M., K. Miyagawa, K. (October 2021). “Displacement-controlled Seismic Design Method of Reinforced Concrete Frame with Steel Damper Column,” in Proceedings of the 17th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Sendai, Japan.

- Teran-Gilmore, A. (1998). A parametric approach to performance-based numerical seismic design. Earthquake Spectra. 14(3), 501-520. [CrossRef]

- Wada, A., Huang, YH., Iwata, M. (2000). Passive damping technology for buildings in Japan. Progress in Structural Engineering and Materials. 2(3), 335-350. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).