Submitted:

07 May 2024

Posted:

08 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions

2.2. Plasmid Construction and Gene Deletion

2.3. Nodulation Test and Acetylene Reduction Assay (ARA)

2.4. Bacterial Induction, RNA Isolation, and qRT-PCR Analysis of Gene Expression

2.5. Protein Preparation, Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) Analysis, and Protein Identification

2.6. Microscopy

2.7. Bioinformatics

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

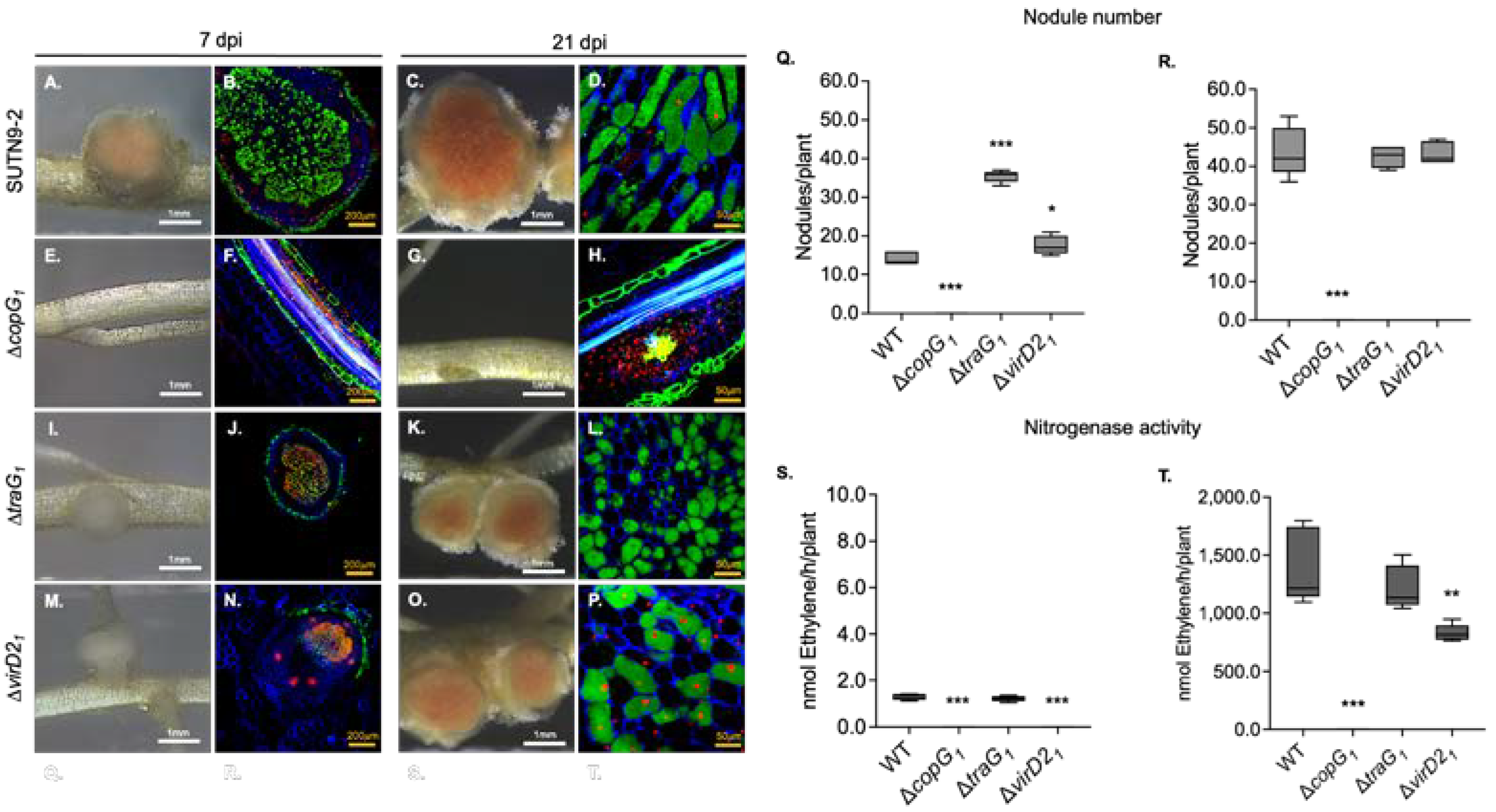

3.1. Symbiotic Properties of ΔcopG1, ΔtraG1, and ΔvirD21 in Vigna Radiata cv. SUT4 Symbiosis

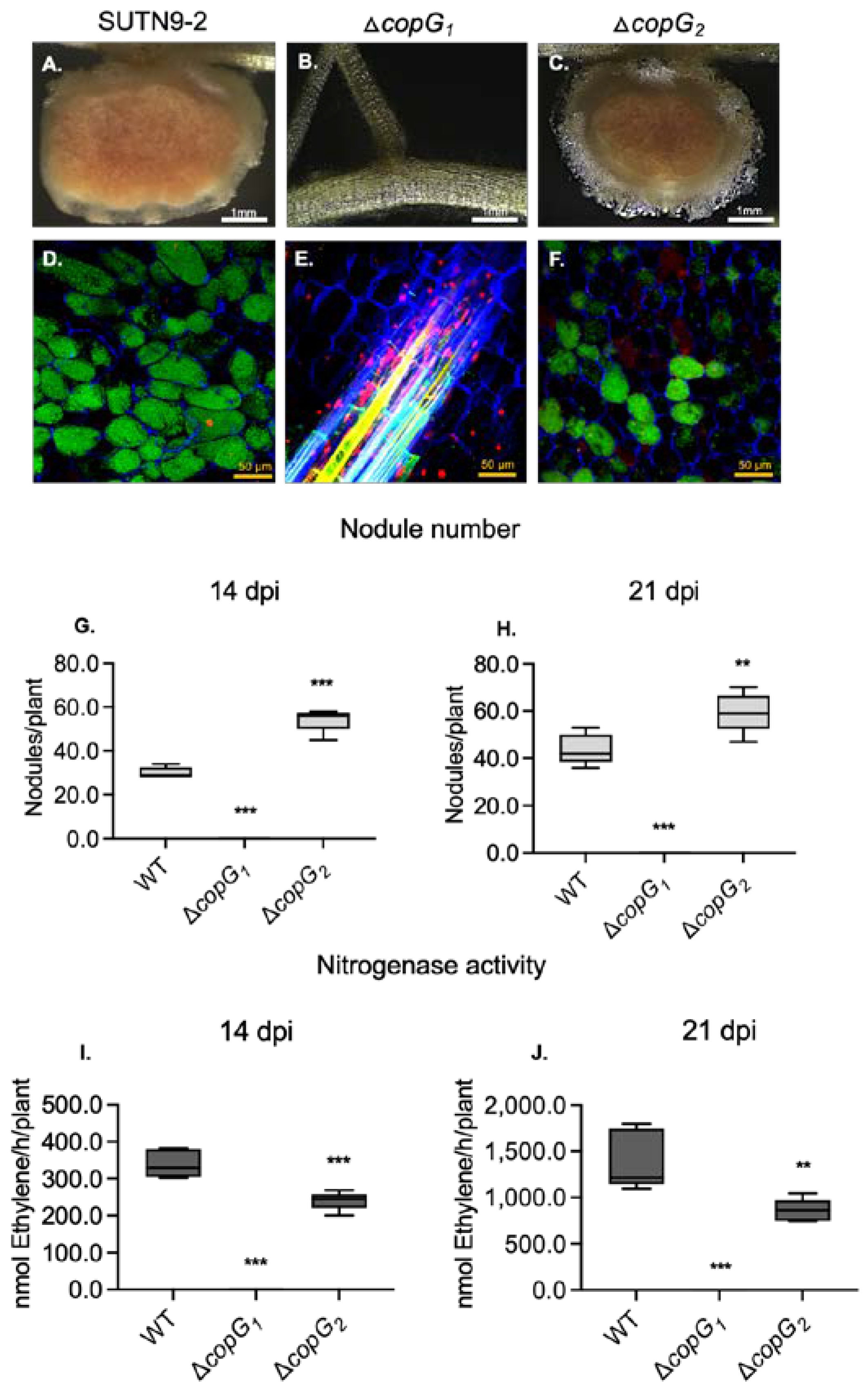

3.2. The copG Genes Are Involved in Nodulation Efficiency of Bradyrhizobium sp. SUTN9-2

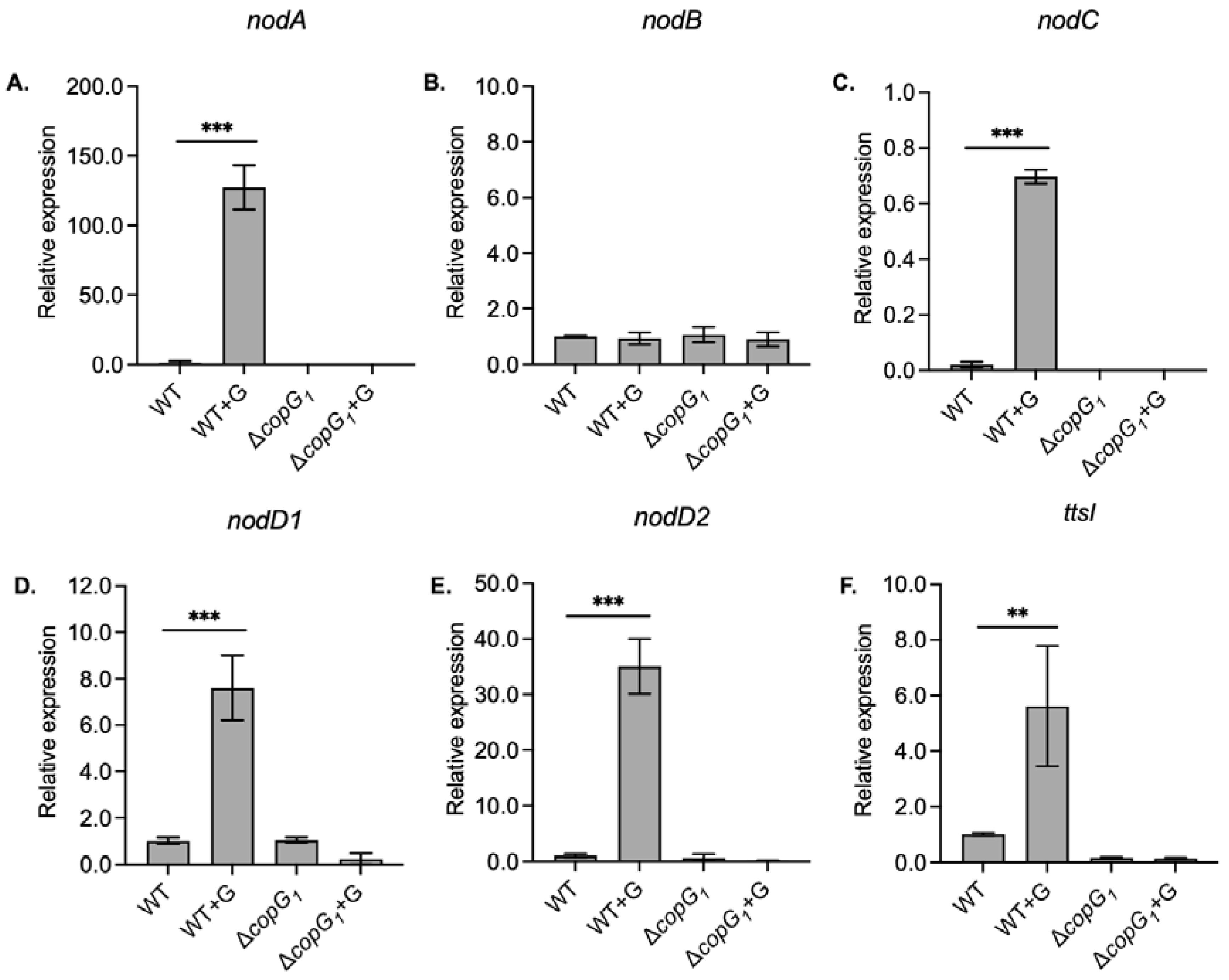

3.3. The copG1 Gene Plays a Crucial Role in the Expression of Nodulation (nod) Genes and Transcriptional Regulator TtsI (ttsI)

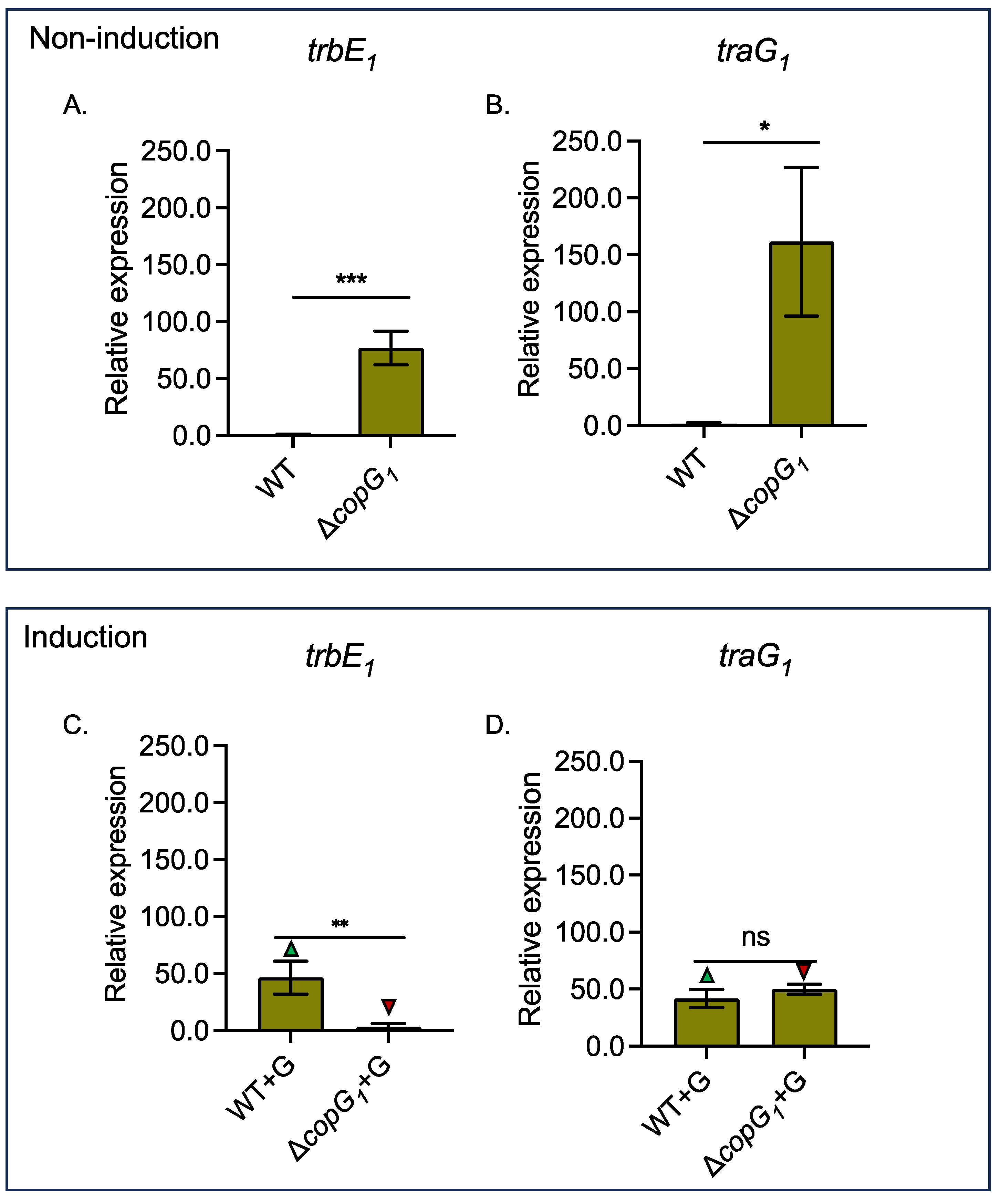

3.4. Bradyrhizobium sp. SUTN9-2 copG1 is Involved in the Repression of T4SS Structural Genes traG1 and trbE1

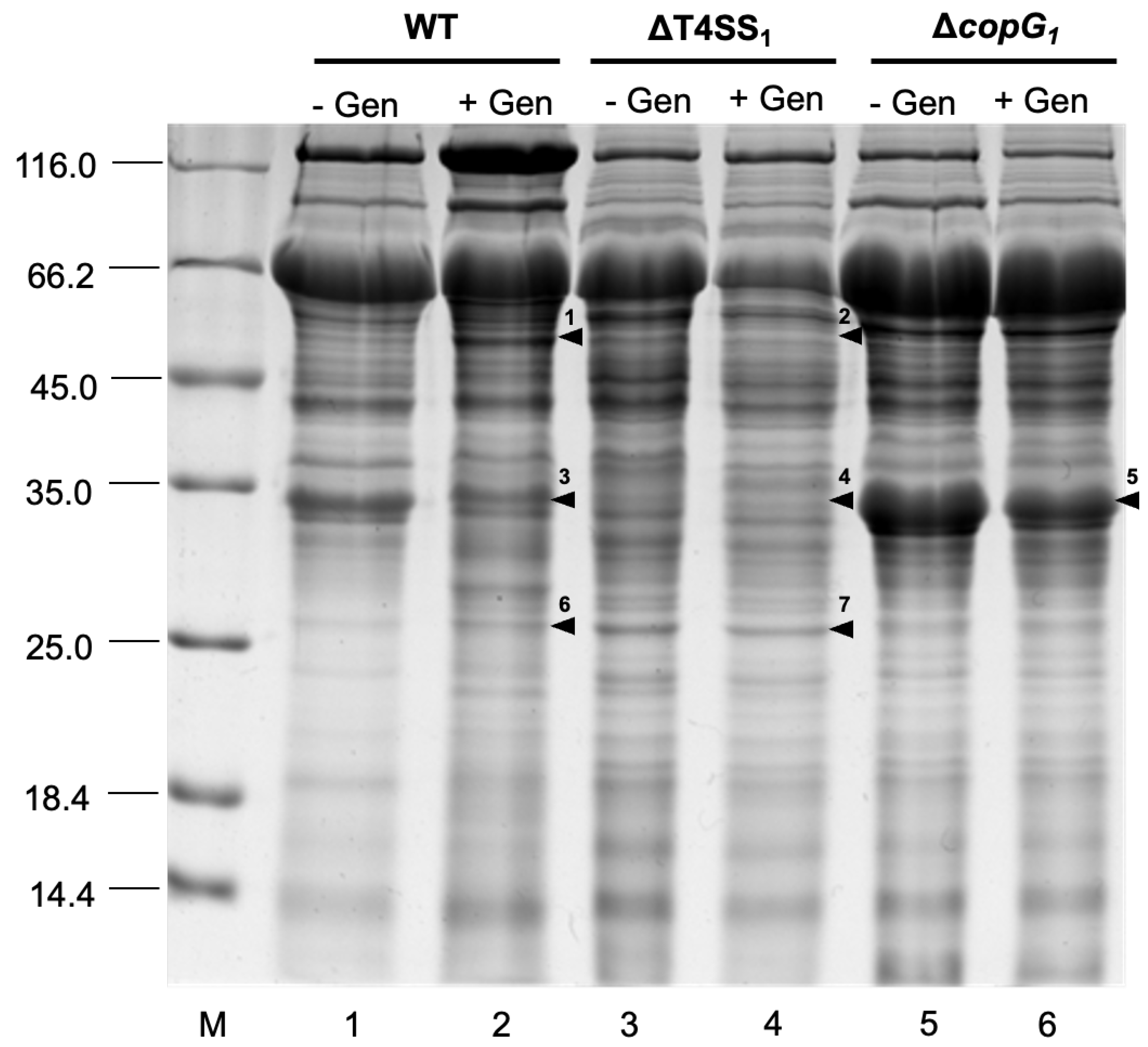

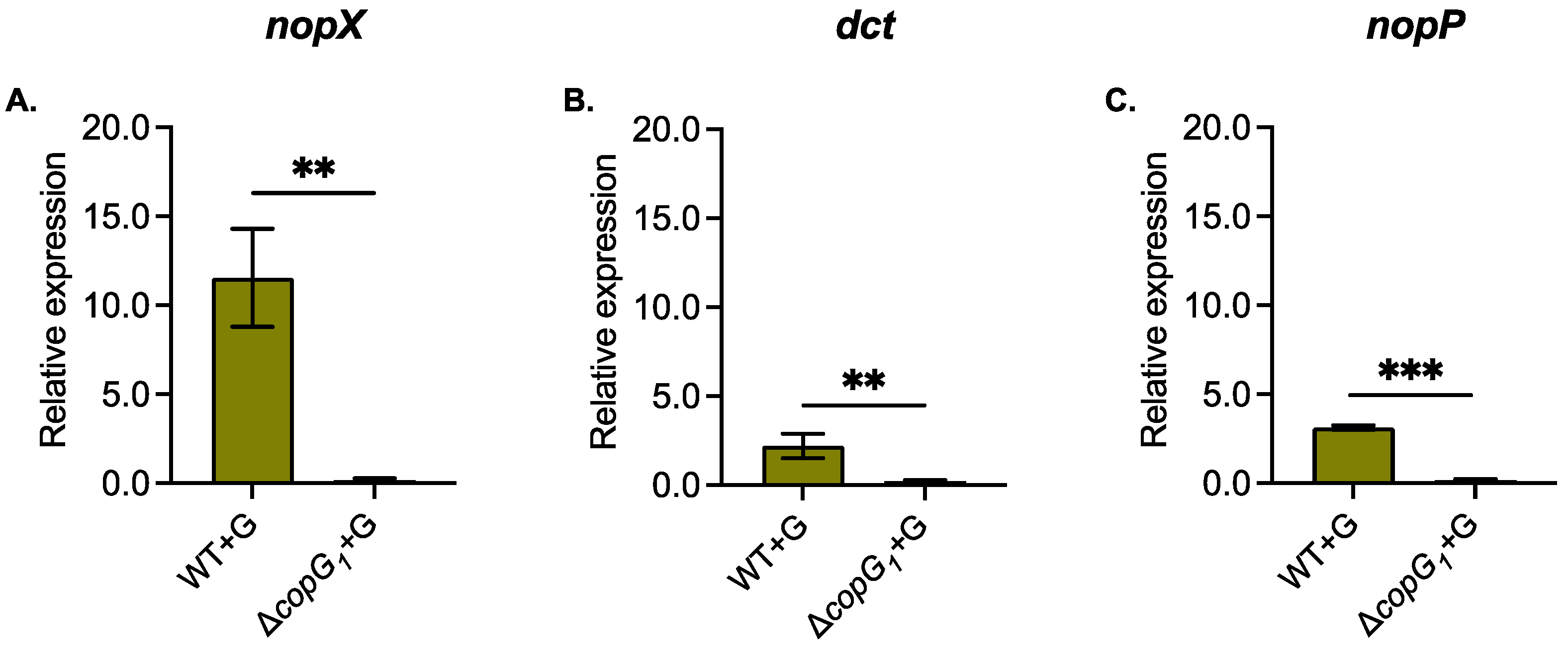

3.5. Effect of T4SS and copG1 on Secreted Protein Pattern after 48 h With Genistein Induction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Dénarié, J.; Debellé, F.; Promé, J.-C. Rhizobium lipo-chitooligosaccharide nodulation factors: signaling molecules mediating recognition and morphogenesis Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996, 65, 503–535.

- Hanin, M.; Jabbouri, S.; Quesada-Vincens, D.; Freiberg, C.; Perret, X.; Promé, J. -C.; Broughton, W.J.; Fellay, R. Sulphation of Rhizobium sp. NGR234 Nod-Factors is dependent on noeE, a new host-specificity gene. Mol. Microbiol. 1997, 24, 1119–1129.

- Fauvart, M.; Michiels, J. Rhizobial secreted proteins as determinants of host specificity in the rhizobium-legume symbiosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 285, 1-9.

- Nelson, M.S.; Sadowsky, M.J. Secretion systems and signal exchange between nitrogen-fixing rhizobia and legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 491. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Guerrero, I.; Medina, C.; Vinardell, J.M.; Ollero, F.J.; López-Baena, F.J. The rhizobial type 3 secretion system: The Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in the rhizobium–legume symbiosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11089. [CrossRef]

- Songwattana, P.; Chaintreuil, C.; Wongdee, J.; Teulet, A.; Mbaye, M.; Piromyou, P.; Gully, D.; Fardoux, J.; Zoumman, A.M.A.; Camuel, A.; et al. Identification of type III effectors modulating the symbiotic properties of Bradyrhizobium vignae strain ORS3257 with various Vigna species. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4874.

- Paço, A.; Da-Silva, J.R.; Eliziário, F.; Brígido, C.; Oliveira, S.; Alexandre, A. traG gene is conserved across Mesorhizobium spp. able to nodulate the same host plant and expressed in response to root exudates. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 3715271. [CrossRef]

- Salinero-Lanzarote, A.; Pacheco-Moreno, A.; Domingo-Serrano, L.; Durán, D.; Ormeño-Orrillo, E.; Martínez-Romero, E.; Albareda, M.; Palacios, J.M.; Rey, L. Type VI secretion system of Rhizobium etli Mim1 has a positive effect in symbiosis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95, fiz054. [CrossRef]

- Tighilt, L.; Boulila, F.; De Sousa, B.F.S.; Giraud, E.; Ruiz-Argüeso, T.; Palacios, J.M.; Imperial, J.; Rey, L. The Bradyrhizobium sp. LmicA16 type VI secretion system is required for efficient nodulation of Lupinus spp. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 84, 844–855. [CrossRef]

- Fronzes, R.; Christie, P.J.; Waksman, G. The structural biology of type IV secretion systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 703–714. [CrossRef]

- Piromyou, P.; Songwattana, P.; Teamtisong, K.; Tittabutr, P.; Boonkerd, N.; Tantasawat, P.A.; Giraud, E.; Göttfert, M.; Teaumroong, N. Mutualistic co-evolution of T3SSs during the establishment of symbiotic relationships between Vigna radiata and bradyrhizobia. MicrobiologyOpen 2019, 8, e00781.

- Kaneko, T.; Maita, H.; Hirakawa, H.; Uchiike, N.; Minamisawa, K.; Watanabe, A.; Sato, S. Complete genome sequence of the soybean symbiont Bradyrhizobium japonicum strain USDA6T. Genes 2011, 2, 763–787.

- Okazaki, S.; Noisangiam, R.; Okubo, T.; Kaneko, T.; Oshima, K.; Hattori, M.; Teamtisong, K.; Songwattana, P.; Tittabutr, P.; Boonkerd, N.; et al. Genome analysis of a novel Bradyrhizobium sp. DOA9 carrying a symbiotic plasmid. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0117392. [CrossRef]

- Cytryn, E.J.; Jitacksorn, S.; Giraud, E.; Sadowsky, M.J. Insights learned from pBTAi1, a 229-Kb accessory plasmid from Bradyrhizobium sp. strain BTAi1 and prevalence of accessory plasmids in other Bradyrhizobium sp. strains. ISME J. 2008, 2, 158–170.

- Wangthaisong, P.; Piromyou, P.; Songwattana, P.; Wongdee, J.; Teamtaisong, K.; Tittabutr, P.; Boonkerd, N.; Teaumroong, N. The type IV secretion system (T4SS) mediates symbiosis between Bradyrhizobium sp. SUTN9-2 and legumes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e00040-23.

- Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, E.T.; Tian, C.F.; Wang, F.Q.; Han, L.L.; Chen, W.F.; Chen, W.X. Bradyrhizobium elkanii , Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense and Bradyrhizobium japonicum are the main rhizobia associated with Vigna unguiculata and Vigna radiata in the subtropical region of China. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 285, 146–154.

- Albareda, M.; Rodríguez-Navarro, D.N.; Temprano, F.J. Soybean inoculation: dose, N fertilizer supplementation and rhizobia persistence in sSoil. Field Crops Res. 2009, 113, 352–356.

- Costa, M.; Solà, M.; Del Solar, G.; Eritja, R.; Hernández-Arriaga, A.M.; Espinosa, M.; Gomis-Rüth, F.X.; Coll, M. Plasmid transcriptional repressor CopG oligomerises to render helical superstructures unbound and in complexes with oligonucleotides. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 310, 403–417. [CrossRef]

- Schröder, G.; Krause, S.; Zechner, E.L.; Traxler, B.; Yeo, H.-J.; Lurz, R.; Waksman, G.; Lanka, E. TraG-like proteins of DNA transfer systems and of the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system: inner membrane gate for exported substrates? J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 2767–2779.

- Tegtmeyer, N.; Linz, B.; Yamaoka, Y.; Backert, S. Unique TLR9 activation by Helicobacter pylori depends on the Cag T4SS, but not on VirD2 relaxases or VirD4 coupling proteins. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 121. [CrossRef]

- Sadowsky, M.J.; Tully, R.E.; Cregan, P.B.; Keyser, H.H. Genetic Diversity in Bradyrhizobium japonicum serogroup 123 and its relation to genotype-specific nodulation of soybean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 2624–2630. [CrossRef]

- Ditta, G.; Stanfield, S.; Corbin, D.; Helinski, D.R. Broad host range DNA cloning system for Gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1980, 77, 7347–7351. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.-W.; Alley, M.R.K. Proteolysis of the McpA chemoreceptor does not require the Caulobacter major chemotaxis operon. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 504–507. [CrossRef]

- Blondelet-Rouault, M.-H.; Weiser, J.; Lebrihi, A.; Branny, P.; Pernodet, J.-L. Antibiotic resistance gene cassettes derived from the π interposon for use in E. coli and Streptomyces. Gene 1997, 190, 315–317.

- Muyzer, G.; De Waal, E.C.; Uitterlinden, A.G. Profiling of complexmicrobial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 695–700.

- Teamtisong, K.; Songwattana, P.; Noisangiam, R.; Piromyou, P.; Boonkerd, N.; Tittabutr, P.; Minamisawa, K.; Nantagij, A.; Okazaki, S.; Abe, M.; et al. Divergent nod-containing Bradyrhizobium sp. DOA9 with a megaplasmid and its host range. Microbes Environ. 2014, 29, 370–376. [CrossRef]

- Ehrhardt, D.; Atkinson, E.; Long depolarization of alfalfa root hair membrane potential by Rhizobium meliloti Nod factors. Science 1992, 256, 998–1000. [CrossRef]

- Renier, S.; Hébraud, M.; Desvaux, M. Molecular biology of surface colonization by Listeria monocytogenes : an additional facet of an opportunistic Gram-positive foodborne pathogen. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 835–850. [CrossRef]

- Somasegaran, P.; Hoben, H.J. Handbook for rhizobia; Springer New York: New York, NY, 1994; ISBN 978-1-4613-8377-2.

- Phimphong, T.; Sibounnavong, P.; Phommalath, S.; Wongdee, J.; Songwattana, P.; Piromyou, P.; Greetatorn, T.; Boonkerd, N.; Tittabutr, P.; Teaumroong, N. Selection and evaluation of Bradyrhizobium inoculum for peanut, Arachis hypogea production in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2023, 15, 137–154.

- Bradford, M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254.

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [CrossRef]

- Haag, A.F.; Baloban, M.; Sani, M.; Kerscher, B.; Pierre, O.; Farkas, A.; Longhi, R.; Boncompagni, E.; Hérouart, D.; Dall’Angelo, S.; et al. Protection of Sinorhizobium against host cysteine-rich antimicrobial peptides is critical for symbiosis. PLoS Biol. 2011, 9, e1001169. [CrossRef]

- Acebo, P.; García De Lacoba, M.; Rivas, G.; Andreu, J.M.; Espinosa, M.; Solar, G.D. Structural features of the plasmid pMV158-encoded transcriptional repressor CopG, a protein sharing similarities with both helix-turn-helix and β-sheet DNA binding proteins. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 1998, 32, 248–261.

- Vallenet, D.; Calteau, A.; Dubois, M.; Amours, P.; Bazin, A.; Beuvin, M.; Burlot, L.; Bussell, X.; Fouteau, S.; Gautreau, G.; et al. MicroScope: an integrated platform for the annotation and exploration of microbial gene functions through genomic, pangenomic and metabolic comparative analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, gkz926. [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [CrossRef]

- Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Blum, M.; Chuguransky, S.; Grego, T.; Pinto, B.L.; Salazar, G.A.; Bileschi, M.L.; Bork, P.; Bridge, A.; Colwell, L.; et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D418–D427.

- Gomis-Ruth, F.X. The structure of plasmid-encoded transcriptional repressor CopG unliganded and bund to its operator. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 7404–7415.

- Heidstra, R.; Bisseling, T. Nod factor-induced host responses and mechanisms of Nod factor perception. New Phytol. 1996, 133, 25–43. [CrossRef]

- Marie, C.; Deakin, W.J.; Ojanen-Reuhs, T.; Diallo, E.; Reuhs, B.; Broughton, W.J.; Perret, X. TtsI, a key regulator of Rhizobium species NGR234 is required for type III-dependent protein secretion and Synthesis of Rhamnose-Rich Polysaccharides. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2004, 17, 958–966. [CrossRef]

- Cascales, E.; Atmakuri, K.; Sarkar, M.K.; Christie, P.J. DNA Substrate-Induced Activation of the Agrobacterium VirB/VirD4 Type IV Secretion System. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 2691–2704. [CrossRef]

- Christie, P.J.; Whitaker, N.; González-Rivera, C. Mechanism and structure of the bacterial type IV secretion systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 1578–1591. [CrossRef]

- Gunton, J.E.; Gilmour, M.W.; Baptista, K.P.; Lawley, T.D.; Taylor, D.E. Interaction between the co-inherited TraG coupling protein and the TraJ membrane-associated protein of the H-plasmid conjugative DNA transfer system resembles chromosomal DNA translocases. Microbiology 2007, 153, 428–441. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wong, J.J.W.; Edwards, R.A.; Manchak, J.; Frost, L.S.; Glover, J.N.M. Structural basis of specific TraD-TraM recognition during F plasmid-mediated bacterial conjugation. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 70, 89–99.

- Byrd, D.R.; Matson, S.W. Nicking by transesterification: the reaction catalysed by a relaxase. Mol. Microbiol. 1997, 25, 1011–1022. [CrossRef]

- Van Kregten, M.; Lindhout, B.I.; Hooykaas, P.J.J.; Van Der Zaal, B.J. Agrobacterium -mediated T-DNA transfer and integration by minimal VirD2 consisting of the relaxase domain and a type IV secretion system translocation signal. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2009, 22, 1356–1365.

- Ramsay, J.P.; Sullivan, J.T.; Stuart, G.S.; Lamont, I.L.; Ronson, C.W. Excision and transfer of the Mesorhizobium loti R7A symbiosis island requires an integrase IntS, a novel recombination directionality factor RdfS, and a putative relaxase RlxS. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 62, 723–734.

- Hausrath, A.C.; Ramirez, N.A.; Ly, A.T.; McEvoy, M.M. The bacterial copper resistance protein CopG contains a cysteine-bridged tetranuclear copper cluster. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 11364–11376. [CrossRef]

- Marrero, K.; Sánchez, A.; González, L.J.; Ledón, T.; Rodríguez-Ulloa, A.; Castellanos-Serra, L.; Pérez, C.; Fando, R. Periplasmic proteins encoded by VCA0261–0260 and VC2216 genes together with copA and cueR products are required for copper tolerance but not for virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 2012, 158, 2005–2016. [CrossRef]

- Breg, J.N.; Van Opheusden, J.H.J.; Burgering, M.J.M.; Boelens, R.; Kaptein, R. Structure of Arc repressor in solution: evidence for a family of β-sheet DNA-binding proteins. Nature 1990, 346, 586–589.

- Somers, W.S.; Phillips, S.E.V. Crystal structure of the Met repressor–operator complex at 2.8 Å resolution reveals DNA recognition by β-strands. Nature 1992, 359, 387–393.

- del Solar, G.; Hernández-Arriaga, A.M.; Gomis-Rüth, F.X.; Coll, M.; Espinosa, M. A Genetically economical family of plasmid-encoded transcriptional repressors involved in control of plasmid copy number. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 4943–4951. [CrossRef]

- Guglielmini, J.; Quintais, L.; Garcillán-Barcia, M.P.; de la Cruz, F.; Rocha, E.P.C. The repertoire of ICE in prokaryotes underscores the unity, diversity, and ubiquity of conjugation. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002222. [CrossRef]

- Bellanger, X.; Payot, S.; Leblond-Bourget, N.; Guédon, G. Conjugative and mobilizable genomic islands in bacteria: evolution and diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 720–760. [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.; Doerfel, A.; Göttfert, M. Mutational and transcriptional analysis of the type III secretion system of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2002, 15, 1228–1235. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Graven, Y.N.; Broughton, W.J.; Perret, X. Flavonoids induce temporal shifts in gene-expression of nod -box controlled loci in Rhizobium sp. NGR234. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 51, 335–347.

- Teulet, A.; Camuel, A.; Perret, X.; Giraud, E. Theversatile roles of type III secretion systems in Rhizobium-legume symbioses. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 76, 45–65.

- Yurgel, S.N.; Kahn, M.L. Dicarboxylate transport by rhizobia. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 28, 489–501. [CrossRef]

- Ronson, C.W.; Lyttleton, P.; Robertson, J.G. C4 -dicarboxylate transport mutants of Rhizobium trifolii form ineffective nodules on Trifolium Repens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1981, 78, 4284–4288.

- Yurgel, S.N.; Kahn, M.L. Sinorhizobium meliloti dctA mutants with partial ability To transport dicarboxylic acids. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 1161–1172. [CrossRef]

- Marie, C.; Deakin, W.J.; Viprey, V.; Kopciñska, J.; Golinowski, W.; Krishnan, H.B.; Perret, X.; Broughton, W.J. Characterization of Nops, nodulation outer proteins, secreted via the type III secretion system of NGR234. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2003, 16, 743–751. [CrossRef]

- Bartsev, A.V.; Boukli, N.M.; Deakin, W.J.; Staehelin, C.; Broughton, W.J. Purification and phosphorylation of the effector protein NopL from Rhizobium sp. NGR234. FEBS Lett. 2003, 554, 271–274. [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, M.; Takahashi, S.; Umehara, Y.; Iwano, H.; Tsurumaru, H.; Odake, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Kondo, H.; Konno, Y.; Yamakawa, T.; et al. ariation in bradyrhizobial NopP effector determines symbiotic incompatibility with Rj2-soybeans via effector-triggered immunity. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3139.

- Streeter, J.G. Effect of nitrate on the organic acid and amino acid composition of legume nodules. Plant Physiol. 1987, 85, 774–779. [CrossRef]

- Forde, B.G.; Lea, P.J. Glutamate in plants: metabolism, regulation, and signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 2339–2358. [CrossRef]

- Finan, T.M.; Wood, J.M.; Jordan, D.C. Symbiotic properties of C4-dicarboxylic acid transport mutants of Rhizobium leguminosarum. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 154, 1403–1413. [CrossRef]

- Jording, D.; Sharma, P.K.; Schmidt, R.; Engelke, T.; Uhde, C.; Pühler, A. Regulatory aspects of the C4-dicarboxylate transport in Rhizobium meliloti: transcriptional activation and dependence on effectave symbiosis. J. Plant Physiol. 1993, 141, 18–27. [CrossRef]

| Strain or Plasmid | Relevant Characteristics | Reference or |

|---|---|---|

| Source | ||

| Strain | ||

| Bradyrhizobium sp. | ||

| SUTN9-2 | A. americana nodule isolate (paddy crop) | |

| ∆copG1 | SUTN9-2 derivative containing an Ω cassette insertion at HindIII site, copG copy 1::sm/sp; Smr, Spr | This study |

| ∆copG2 | SUTN9-2 derivative containing an Ω cassette insertion at BamHI site, copG copy 2::sm/sp; Smr, Spr | This study |

| ∆traG1 | SUTN9-2 derivative containing an Ω cassette insertion at BamHI site, traG copy 1::sm/sp; Smr, Spr | This study |

| ∆virD21 | SUTN9-2 derivative containing an Ω cassette insertion at BamHI site, virD2 copy 1::sm/sp; Smr, Spr | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | Toyobo Inc. |

| Plasmid | ||

| pRK2013 | ColE1 replicon carrying RK2 transfer genes; Kmr; Helper plasmid | [22] |

| pNTPS129 | Cloning vector harboring sacB gene under the control of the constitutive npt2 promoter; Kmr | [23] |

| pNTPS129-∆copG1 | pNTPS129-npt2-sacB containing the flanking region of copG copy 1 | This study |

| pNTPS129-∆copG2 | pNTPS129-npt2-sacB containing the flanking region of copG copy 2 | This study |

| pNTPS129-∆traG1 | pNTPS129-npt2-sacB containing the flanking region of traG copy 1 | This study |

| pNTPS129-∆virD21 | pNTPS129-npt2-sacB containing the flanking region of virD2 copy 1 | This study |

| Name | Sequences (5’-3’) | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Primers for gene deletion | ||

| Up.copG1. XbaI.F | CCT TGA GAT CTA GAT GTA GTC TGC CCC GAA GTA GC | This primer sets used to obtain the deletion of copG1 gene of Bradyrhizobium sp. SUTN9-2 by double crossing over. |

| Up. copG1. overl. HindIII. R | GAG GCG GAC ATG AAA GCT TAA TGA AGG CGG ACG GCC ACT AG | |

| Dw. copG1. overl. HindIII. F | GTC CGC CTT CAT TAA GCT TTC ATG TCC GCC TCA CAG TCC GA | |

| Dw. copG1. EcoRI.R | AGA TCG GGA ATT CGT TGA CCG AGG ATC TTC AGG CCA | |

| Up. copG2. XbaI.F | GCC GTT TCT AGA ATT GCG ACA ACG GAC CAG GGC AA | This primer sets used to obtain the deletion of copG2 gene of Bradyrhizobium sp. SUTN9-2 by double crossing over. |

| Up. copG2. overl. HindIII. R | GCG CGA CCG AAT GAA GCT TAA GCT GGT CAC GCT ATC GGC T | |

| Dw. copG2. overl. HindIII. F | GCG TGA CCA GCT TAA GCT TCA TTC GGT CGC GCA TAT TGC C | |

| Dw. copG2. EcoRI. R | CTG TCC GAA TTC ATG TCG TTC CTC GGG TTG TAC C | |

| Up. traG1. XbaI. F | TTC GGG TCT AGA TGT AGT CTG CCC CGA AGT AGC | This primer sets used to obtain the deletion of traG1 gene of Bradyrhizobium sp. SUTN9-2 by double crossing over. |

| Up. traG1. overl. BamHI | TCC CTC CAA TCA CGG ATC CAT CCT GGT GAC GAT CTC GGA C | |

| Dw. traG1. overl. BamHI | TCG TCA CCA GGA TGG ATC CGT GAT TGG AGG GAT CGT TCA CAG | |

| Dw. traG1.EcoRI.R | CCG GCT GAA TTC CTT GGA AAG CCT TGG TCT CG | |

| Up. virD21. XbaI. F | ACC GGC TTC TAG AAG ATG CGC AGT CCG CAT CAT C | This primer sets used to obtain the deletion of virD21 gene of Bradyrhizobium sp. SUTN9-2 by double crossing over. |

| Up. virD21. overl. BamHI | GAG GAG AAG GAA TGG ATC CTG AAC GAT CCC TCC AAT CAC CG | |

| Dw. virD21. overl. BamHI | GAG GGA TCG TTC AGG ATC CAT TCC TTC TCC TCA GCC ATG GC | |

| Dw. virD21. EcoRI. R | CCA TCG GAA TTC TTG TCG ATG CGG AGG AGG CAT C | |

|

Primers for qRT-PCR analysis |

||

| SUTN9-2. nodA. F | GTT CAA TGC GCA GCC CTT TGA G | Specific primers for nodA gene expression in SUTN9-2 on chromosome |

| SUTN9-2. nodA. R | ATT CCG AGT CCT TCG AGA TCC G | |

| SUTN9-2. nodC. F | ATT GGC TCG CGT GCA ACG AAG A | Specific primers for nodC gene expression in SUTN9-2 on chromosome |

| SUTN9-2. nodC. R | AAT CAC TCG GCT TCC CAC GGA A | |

| SUTN9-2. nodD1. F | ATT CGT CTC CTC AGA CCG TGC T | Specific primers for nodD1 gene expression in SUTN9-2 on chromosome |

| SUTN9-2. nodD1. R | TTC ATG TCG AGT GCG CAC CCT A | |

| SUTN9-2. nodD2. F | TGC TTA ACT GCA ACG TGA CCC | Specific primers for nodD2 gene expression in SUTN9-2 on chromosome |

| SUTN9-2. nodD2. R | ATG AGC ACG AGG AGC TTC TC | |

| SUTN9-2. trbE1. F | GAT TGC AGG AGA ACC GTG AGG C | Specific primers for trbE1 gene expression in SUTN9-2 on chromosome |

| SUTN9-2. trbE1. R | AAC AGC GCC GAG GAT TCA GTC T | |

| SUTN9-2. traG1. F | TTC TCG ATC TGG TTC AGC GAC TG | Specific primers for traG1 gene expression in SUTN9-2 on chromosome |

| SUTN9-2. traG1. R | TTG ACC GAG GAT CTT CAG GCC A | |

| SUTN9-2. ttsI. F | ATG AGT TCG TCG GTG GAC AC | Specific primers for transcriptional regulator TtsI (ttsI) gene expression in SUTN9-2 on chromosome |

| SUTN9-2. ttsI. R | CCA CAT GGT CCT GCT CGA AT | |

| 16s. F | ATT ACC GCG GCT GCT GG | Universal primers for 16S rRNA used as internal control for bacterial gene expression [25] |

| 16s. R | ACT CCT ACG CGA GGC AGC AG | |

| dct. F | CGA CTA TCA GGG CGT GAA AT | Specific primers for C4-dicarboxylate transport (dct) gene expression in SUTN9-2 on chromosome |

| dct. R | TCC AGC AAT CAG ACC TGT G | |

| nopX. F | GGGTGGTCGAGGAAGTATTG |

Specific primers for Type III secretion system (T3SS) gene expression in SUTN9-2 on chromosome |

| nopX. R | GGTTATGACCCAGACCGATG | |

| nopP. F | GGTCACACCGACGAAGATAC | |

| nopP. R | CCGAAGATCCACTTGGGATG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).