Submitted:

06 May 2024

Posted:

06 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mackenzie, J.S.; Gubler, D.J.; Petersen, L.R. Emerging flaviviruses: the spread and resurgence of Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and dengue viruses. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissenböck, H.; Hubálek, Z.; Bakonyi, T.; Nowotny, N. Zoonotic mosquito-borne flaviviruses: worldwide presence of agents with proven pathogenicity and potential candidates of future emerging diseases. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 140, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, C.; Jimenez-Clavero, M.A.; Leblond, A.; Durand, B.; Nowotny, N.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Zientara, S.; Jourdain, E.; Lecollinet, S. Flaviviruses in Europe: complex circulation patterns and their consequences for the diagnosis and control of West Nile disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2013, 10, 6049–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkash, V.; Woods, K.; Kafetzopoulou, L.; Osborne, J.; Aarons, E.; Cartwright, K. West Nile virus infection in travelers returning to United Kingdom from South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 367–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habarugira, G.; Suen, W.W.; Hobson-Peters, J.; Hall, R.A.; Bielefeldt-Ohmann, H. West Nile virus: an update on pathobiology, epidemiology, diagnostics, control and “One Health” implications. Pathogens. 2020, 9, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzoli, A.; Jimenez-Clavero, M.A.; Barzon, L.; Cordioli, P.; Figuerola, J.; Koraka, P.; Martina, B.; Moreno, A.; Nowotny, N.; Pardigon, N.; Sanders, N.; Ulbert, S.; Tenorio, A. The challenge of West Nile virus in Europe: knowledge gaps and research priorities. Euro Surveill. 2015, 20, 21135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubálek, Z. An annotated checklist of pathogenic microorganisms associated with migratory birds. J. Wildl. Dis. 2004, 40, 639–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Z.; Sjödin, H.; Semenza, J.C.; Tozan, Y.; Sewe, M.O.; Wallin, J.; Rocklöv, J. European projections of West Nile virus transmission under climate change scenarios. One Health. 2023, 16, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesen, C.; Herrador, Z.; Fernandez-Martinez, B.; Figuerola, J.; Gangoso, L.; Vazquez, A.; Gómez-Barroso, D. A systematic review of environmental factors related to WNV circulation in European and Mediterranean countries. One Health. 2023, 16, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Barriga, D.; Aguilera-Sepúlveda, P.; Guerrero-Carvajal, F.; Llorente, F.; Reina, D.; Pérez-Martín, J.E.; Jiménez-Clavero, M.A.; Frontera, E. West Nile and Usutu virus infections in wild birds admitted to rehabilitation centres in Extremadura, western Spain, 2017–2019. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 255, 109020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bocanegra, I.; Franco, J.J.; León, C.I.; Barbero-Moyano, J.; García-Miña, M.V.; Fernández-Molera, V.; Gómez, M.B.; Cano-Terriza, D.; Gonzálvez, M. High exposure of West Nile virus in equid and wild bird populations in Spain following the epidemic outbreak in 2020. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 3624–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzal, A.; Ferraguti, M.; Muriel, J.; Magallanes, S.; Ortiz, J.A.; García-Longoria, L.; Bravo-Barriga, D.; Guerrero-Carvajal, F.; Aguilera-Sepúlveda, P.; Llorente, F.; de Lope, F.; Jiménez-Clavero, M.Á.; Frontera, E. Circulation of zoonotic flaviviruses in wild passerine birds in Western Spain. Vet. Microbiol. 2022, 268, 109399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramozzino, P.; Carvelli, A.; Bruni, G.; Cappiello, G.; Censi, F.; Magliano, A.; Manna, G.; Ricci, I.; Rombolà, P.; Romiti, F.; Rosone, F.; Sala, M.G.; Scicluna, M.T.; Vaglio, S.; Liberato, C.D. West Nile and Usutu viruses co-circulation in central Italy: outcomes of the 2018 integrated surveillance. Parasit. Vectors. 2021, 14, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, U.; Bergmann, F.; Fischer, D.; Müller, K.; Holicki, C.M.; Sadeghi, B.; Sieg, M.; Keller, M.; Schwehn, R.; Reuschel, M.; Fischer, L.; Krone, O.; Rinder, M.; Schütte, K.; Schmidt, V.; Eiden, M.; Fast, C.; Günther, A.; Globig, A.; Conraths, F.J.; Staubach, C.; Brandes, F.; Lierz, M.; Korbel, R.; Vahlenkamp, T.W.; Groschup, M.H. Spread of West Nile virus and Usutu virus in the German bird population, 2019-2020. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, S.C.; Ramos, F.; Fagulha, T.; Duarte, M.; Henriques, M.; Luís, T.; Fevereiro, M. Serological evidence of West Nile virus circulation in Portugal. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 152, 407–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A. Serological surveillance of West Nile virus and molecular diagnostic of West Nile virus, Usutu virus, avian Influenza and Newcastle disease virus in wild birds of Portugal. Master Thesis, University of Lisbon – Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Lisbon, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Filipe, A.R.; Pinto, M.R. Survey for antibodies to arboviruses in serum of animals from southern Portugal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1969, 18, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraldes, M.A.; Cunha, M.V.; Godinho, C.; Lima, R.F.; Giovanetti, M. The historical ecological background of West Nile virus in Portugal provides One Health opportunities into the future. [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, J.; Barros, S.C.; Zé-Zé, L.; Damineli, D.S.C.; Giovanetti, M.; Osório, H.C.; Amaro, F.; Henriques, A.M.; Ramos, F.; Luís, T.; Duarte, M.D.; Fagulha, T.; Alves, M.J.; Obolski, U. West Nile virus transmission potential in Portugal. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, Y.; Sofer, D.; Bucris, E.D.; Mendelson, E. Surveillance and diagnosis of West Nile virus in the face of Flavivirus cross-reactivity. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, M.P.; Kleinman, S.H.; Tobler, L.H.; Kamel, H.T.; Norris, P.J.; Walsh, I.; Matud, J.L.; Prince, H.E.; Lanciotti, R.S.; Wright, D.J.; Linnen, J.M.; Caglioti, S. Virus and antibody dynamics in acute West Nile virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 198, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvjetković, I.H.; Radovanov, J.; Kovačević, G.; Turkulov, V.; Patić, A. Diagnostic value of urine qRT-PCR for the diagnosis of West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023, 107, 115920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalleri, J.V.; Korbacska-Kutasi, O.; Leblond, A.; Paillot, R.; Pusterla, N.; Steinmann, E.; Tomlinson, J. European College of Equine Internal Medicine consensus statement on equine flaviviridae infections in Europe. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2022, 36, 1858–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, F.; Fischer, D.; Fischer, L.; Maisch, H.; Risch, T.; Dreyer, S.; Sadeghi, B.; Geelhaar, D.; Grund, L.; Merz, S.; Groschup, M.H.; Ziegler, U. Vaccination of zoo birds against West Nile virus - a field study. Vaccines (Basel). 2023, 11, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/west-nile-virus-infection http://www.cdc.gov/westnile/index.html (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Casades-Martí, L.; Cuadrado-Matías, R.; Peralbo-Moreno, A.; Baz-Flores, S.; Fierro, Y.; Ruiz-Fons, F. Insights into the spatiotemporal dynamics of West Nile virus transmission in emerging scenarios. One Health. 2023, 16, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallari, C.T.; Efstathiou, A.; Moysi, M.; Papanikolas, N.; Christodoulou, V.; Mazeris, A.; Koliou, M.; Kirschel, A.N.G. Evidence of West Nile virus seropositivity in wild birds on the island of Cyprus. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csank, T.; Drzewnioková, P.; Korytár, Ľ.; Major, P.; Gyuranecz, M.; Pistl, J.; Bakonyi, T. A Serosurvey of Flavivirus Infection in Horses and Birds in Slovakia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2018, 18, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Tarifa, E.; Napp, S.; Lecollinet, S.; Arenas, A.; Beck, C.; Cerdà-Cuéllar, M.; Fernández-Morente, M.; García-Bocanegra, I. Monitoring of West Nile virus, Usutu virus and Meaban virus in waterfowl used as decoys and wild raptors in southern Spain. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 49, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, A.; Allepuz, A.; Napp, S.; Soler, M.; Selga, I.; Aranda, C.; Casal, J.; Pages, N.; Hayes, E.B.; Busquets, N. Ecological surveillance for West Nile in Catalonia (Spain), learning from a five-year period of follow-up. Zoonoses Public Health. 2014, 61, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfle, U.; Blanco, J.M.; Crespo, E.; Naranjo, V.; Jiménez-Clavero, M.A.; Sanchez, A.; de la Fuente, J.; Gortazar, C. West Nile virus in the endangered Spanish imperial eagle. Vet. Microbiol. 2008, 129, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdélyi, K.; Ursu, K.; Ferenczi, E.; Szeredi, L.; Rátz, F.; Skáre, J.; Bakonyi, T. Clinical and pathologic features of lineage 2 West Nile virus infections in birds of prey in Hungary. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007, 7, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, F.; Fischer, D.; Eiden, M.; Fast, C.; Reuschel, M.; Müller, K.; Rinder, M.; Urbaniak, S.; Brandes, F.; Schwehn, R.; Lühken, R.; Groschup, M.H.; Ziegler, U. West Nile virus and Usutu virus monitoring of wild birds in Germany. Int. J. Environ Res. Public Health. 2018, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, S.; Niedrig, M.; Kaiser, A.; Ellerbrok, H.; Müller, K.; Müller, T.; Conraths, F.J.; Mühle, R.U.; Schmidt, D.; Köppen, U.; Bairlein, F.; Berthold, P.; Pauli, G. Serologic evidence of West Nile virus infections in wild birds captured in Germany. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007, 77, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisher, C.H.; Karabatsos, N.; Dalrymple, J.M.; Shope, R.E.; Porterfield, J.S.; Westaway, E.G.; Brandt, W.E. Antigenic relationships between flaviviruses as determined by cross-neutralization tests with polyclonal antisera. J. Gen. Virol. 1989, 70, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonin, Y. Circulation of West Nile virus and Usutu virus in Europe: overview and challenges. Viruses. 2024, 16, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuno, G. Serodiagnosis of flaviviral infections and vaccinations in humans. Adv. Virus Res. 2003, 61, 3–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingartl, H.M.; Drebot, M.A.; Hubálek, Z.; Halouzka, J.; Andonova, M.; Dibernardo, A.; Cottam-Birt, C.; Larence, J.; Marszal, P. Comparison of assays for the detection of West Nile virus antibodies in chicken serum. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2003, 67, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, Y.S.; Milton, A.A.P.; Ghatak, S.; Ghosh, S. Migratory Birds and Public Health Risks. In Role of Birds in Transmitting Zoonotic Pathogens; Livestock Diseases and Management; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.; Jimenez-Clavero, M.A.; Tejedor, C.G.; Soriguer, R.; Figuerola, J. Prevalence of West Nile virus neutralizing antibodies in Spain is related to the behavior of migratory birds. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008; 8, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguero, M.; Fernandez-Pinero, J.; Buitrago, D.; Sanchez, A.; Elizalde, M.; San Miguel, E.; Villalba, R.; Llorente, F.; Jimenez-Clavero, M.A. Bagaza virus in partridges and pheasants, Spain, 2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1498–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannoli, S.; Sambri, V. West Nile virus and Usutu virus co-circulation in Europe: epidemiology and implications. Microorganisms. 2019, 7, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.R. Sex identification in birds. Semin. Avian Exot. Pet Med. 2000, 9, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, I. Moult and plumage. Ringing & Migration 2009, 24, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuberogoitia, I.; Zabala, J.; Martínez, J.E. Moult in birds of prey: a review of current knowledge and future challenges for research. Ardeola 2018, 65, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaDeau, S.L.; Kilpatrick, A.M.; Marra, P.P. West Nile virus emergence and large-scale declines of North American bird populations. Nature. 2007, 447, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, H.S.; Van Wettere, A.J.; McFarlane, L.; Shearn-Bochsler, V.; Dickson, S.L.; Baker, J.; Hatch, G.; Cavender, K.; Long, R.; Bodenstein, B. West Nile virus transmission in winter: the 2013 Great Salt Lake bald eagle and eared grebes mortality event. PLoS Curr. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/westnile/index.html (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- 49. Birdlife International. European Red List of Birds; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster, G.; Tomassone, L.; Tamba, M.; Chiari, M.; Lavazza, A.; Piazzi, M.; Favretto, A.R.; Balduzzi, G.; Pautasso, A.; Vogler, B.R. The Degree of One Health Implementation in the West Nile Virus Integrated Surveillance in Northern Italy, 2016. Front. Public Health. 2017, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todoric, D.; Vrbova, L.; Mitri, M.E.; Gasmi, S.; Stewart, A.; Connors, S.; Zheng, H.; Bourgeois, A.C.; Drebot, M.; Paré, J.; Zimmer, M.; Buck, P. An overview of the National West Nile Virus Surveillance System in Canada: A One Health approach. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2022, 48, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, V.; Lecollinet, S.; Durand, B. West Nile virus in Europe: A comparison of surveillance system designs in a changing epidemiological context. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011, 11, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carrasco, J.M.; Muñoz, A.R.; Olivero, J.; Segura, M.; García-Bocanegra, I.; Real, R. West Nile virus in the Iberian Peninsula: using equine cases to identify high-risk areas for humans. Euro Surveill. 2023, 28, 2200844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Order | Common name (Scientific name) |

Number (%) tested | Number (%) of seropositive |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accipitriformes | Northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) |

13 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-21.0 |

| Sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) |

10 (4.8) | 1 (10.0) | 0.0-44.5 | |

| Cinereous vulture (Aegypius monachus) |

5 (2.4) | 1 (20.0) | 0.0-71.6 | |

| Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti) |

1 (0.5) | 1 (100) | 0.0-100 | |

| Bonelli’s eagle (Aquila fasciata) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 | |

| Common buzzard (Buteo buteo) |

31 (14.9) | 15 (48.4) | 30.2-67.0 | |

| Short-toed snake-eagle (Circaetus gallicus) |

1 (0.5) | 1 (100) | 0.0-100 | |

| Montagu’s harrier (Circus pygargus) |

2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-84.2 | |

| Griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus) |

18 (8.7) | 1 (5.6) | 0.0-27.3 | |

| Booted eagle (Hieraaetus pennatus) |

10 (4.8) | 7 (70.0) | 34.8-93.3 | |

| Black kite (Milvus migrans) |

6 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-45.9 | |

| Red kite (Milvus milvus) |

7 (3.4) | 1 (14.3) | 0.0-57.9 | |

| Apodiformes | Common swift (Apus apus) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 |

| Pallid swift (Apus pallidus) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 | |

| Caprimulgiformes | European nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus) |

3 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-70.7 |

| Charadriiformes | Yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis) |

3 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-70.7 |

| Ciconiiformes | Grey heron (Ardea cinerea) |

4 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-60.2 |

| White stork (Ciconia ciconia) |

17 (8.2) | 2 (11.8) | 0.0-36.4 | |

| Columbiformes | Rock pigeon (Columba livia) |

3 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-70.7 |

| Common wood-pigeon (Columba palumbus) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 | |

| Collared dove (Streptopelia decaocto) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 | |

| Coraciiformes | Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 |

| Falconiformes | Peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) |

6 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-45.9 |

| Common kestrel (Falco tinnunculus) |

4 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-60.2 | |

| Passeriformes | European greenfinch (Chloris chloris) |

2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-84.2 |

| Common raven (Corvus corax) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 | |

| Carrion crow (Corvus corone) |

5 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-52.2 | |

| Western house-martin (Delichon urbicum) |

2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 (84.2) | |

| Eurasian jay (Garrulus glandarius) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 | |

| Eurasian magpie (Pica pica) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 | |

| Piciformes | Eurasian green-woodpecker (Picus viridis) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 |

| Strigiformes | Short-eared owl (Asio flammeus) |

1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 |

| Long-eared owl (Asio otus) |

2 (1.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0.0-98.7 | |

| Little owl (Athene noctua) |

4 (1.9) | 1 (25.0) | 0.0-80.6 | |

| Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo) |

3 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-70.7 | |

| Tawny owl (Strix aluco) |

22 (10.6) | 8 (36.4) | 17.2-59.3 | |

| Barn owl (Tyto alba) |

13 (6.3) | 2 (15.4) | 0.0-45.5 | |

| Total | 208 (100) | 42 (20.2) | 15.0-26.3 |

| Variable | Number (%) tested | Number (%) of seropositive |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rehabilitation centre | |||

| CERAS | 21 (10.1) | 7 (33.3) | 14.6-57.0 |

| CERVAS | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 |

| CIARA | 3 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-70.7 |

| CRAS-HVUTAD | 182 (87.5) | 35 (19.2) | 13.8-25.7 |

| RIAS | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 |

| p = 0.362 | |||

| Order | |||

| Accipitriformes | 105 (50.5) | 28 (26.7) | 18.5-36.2 |

| Ciconiiformes | 21 (10.1) | 2 (9.5) | 0.0-30.4 |

| Falconiformes | 10 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-30.9 |

| Passeriformes | 12 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-26.5 |

| Strigiformes | 45 (21.6) | 12 (26.7) | 14.6-42.0 |

| Othera | |||

| p < 0.001 | |||

| Age | |||

| Juvenile | 54 (26.0) | 5 (9.3) | 0.0-20.3 |

| Adult | 28 (13.5) | 9 (32.1) | 15.9-52.4 |

| Undetermined§ | 126 (60.6) | 28 (22.2) | 15.3-30.5 |

| p = 0.014 | |||

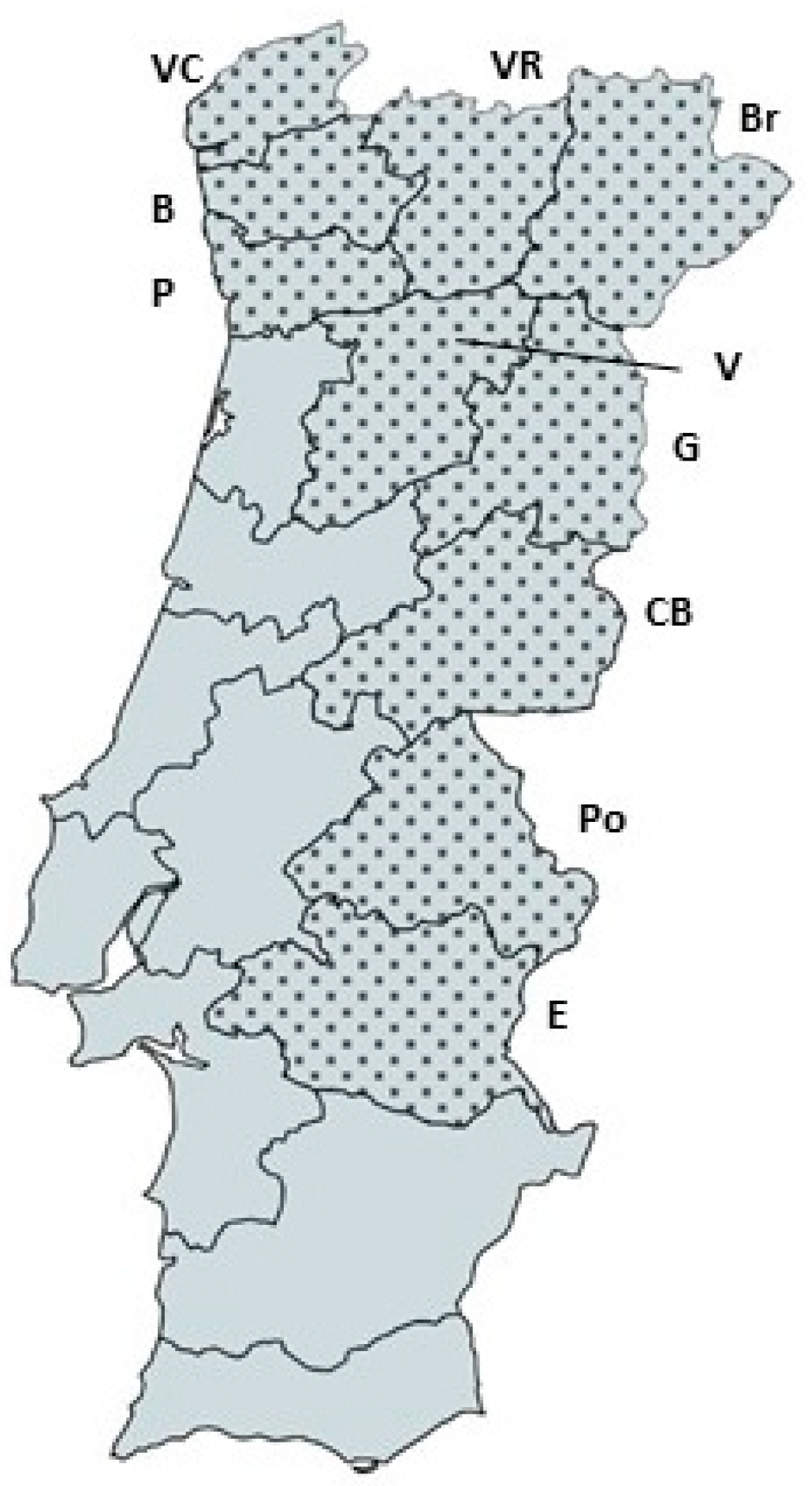

| Geographical region | |||

| North | 133 (63.9) | 26 (19.5) | 13.2-27.3 |

| Centre | 21 (10.1) | 6 (28.6) | 11.3-52.2 |

| Lisbon Metropolitan Area | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0-97.5 |

| Alentejo | 9 (4.3) | 2 (22.2) | 0.0-60.0 |

| Unknown§ | 44 (21.2) | 8 (18.2) | 0.0-32.7 |

| p = 0.725 | |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 21 (10.1) | 1 (4.8) | 0.0-23.8 |

| Male | 32 (15.4) | 11 (34.4) | 18.6-53.2 |

| Undetermined§ | 155 (74.5) | 30 (19.4) | 13.5-26.5 |

| p = 0.017 | |||

| Migratory behavior | |||

| Resident | 158 (76.0) | 31 (19.6) | 13.7-26.7 |

| Migratory | 27 (13.0) | 8 (29.6) | 13.8-50.2 |

| Mixed | 23 (11.1) | 3 (13.0) | 0.0-33.6 |

| p = 0.334 | |||

| TOTAL | 208 (100) | 42 (20.2) | 15.0-26.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).