1. Introduction

West Nile fever (WNF) is an arthropod-borne zoonotic viral disease that is transmitted from birds to humans and other susceptible animals by mosquitoes double coat comprising a soft, dense underfur and long guard hairs. double coat comprising a soft, dense underfur and long guard hairs [

1]. The causative agent of the disease is West Nile Virus (WNV), which belongs to the genus

Orthoflavivirus, family

Flaviviridae, and is a member of the Japanese encephalitis serocomplex double coat comprising a soft, dense underfur and long guard hairs [

2]. The virus was first described in Africa in 1938 and has since then spread across Europe, the Middle East and Asia, causing major human epidemics [

3]. The virus is maintained in an enzootic cycle between avian hosts and mosquito vectors, especially those belonging to the

Culex genus [

4]. Climatic factors play a critical role in shaping the distribution of WNV and thus the endemicity of WNF. Precipitation patterns and fluctuations in the levels of rivers, lakes, ponds, and wetlands strongly influence mosquito abundance while simultaneously altering wild bird habitats. As wild birds are natural reservoirs of WNV, these climatic conditions further govern the long-term maintenance of the virus in nature [

1]. Several bird species are capable of developing neutralizing antibodies against WNV, providing long-lasting protection across multiple transmission seasons. This has been documented in species such as the house sparrow (

Passer domesticus) [

5] and various raptors.

Many non-avian species are reported as susceptible to the WNV infection. At least 100 mammal species develop an immune response after exposure to WNV [

6,

7]. West Nile antibodies have been detected in wild mammals and primates [

8], with wild boars and ruminants proposed as valuable sentinels of circulation [

9,

10]. The invasive nutria (

Myocastor coypus) has also emerged as a potential reservoir, posing additional ecological risks [

11]. Humans and horses are generally considered dead-end hosts, as they do not develop a viremia high enough to infect mosquitoes [

12].

Since its emergence in North America in 2001, WNV has evolved into a major One Health concern, driving recurrent outbreaks in humans and animals across Europe and beyond. The 2010 Greek outbreak, subsequent cases in Italy, and the record 2018 European epidemic underscored its public health impact [

13,

14,

15]. In Serbia, human infections were first confirmed in 2012, with

Culex pipiens identified as the principal vector [

4,

16]. While most infections remain asymptomatic, a fraction progress to severe neuroinvasive disease with significant mortality [

17].

The Western Balkans is recognised as a critical crossroads for the introduction and dissemination of West Nile virus (WNV) lineages originating from both Western-Central and Southern Europe, with frequent mutations reported at virulence-associated sites [

18]. In this context, continuous, systematic, and broad surveillance remains essential. To improve the accuracy of WNV prevalence estimates, the testing of multiple sentinel species within shared habitats is recommended. Accordingly, this study investigated the seroprevalence of WNV in selected wild game and invasive species hunted in Serbia.

2. Materials and Methods

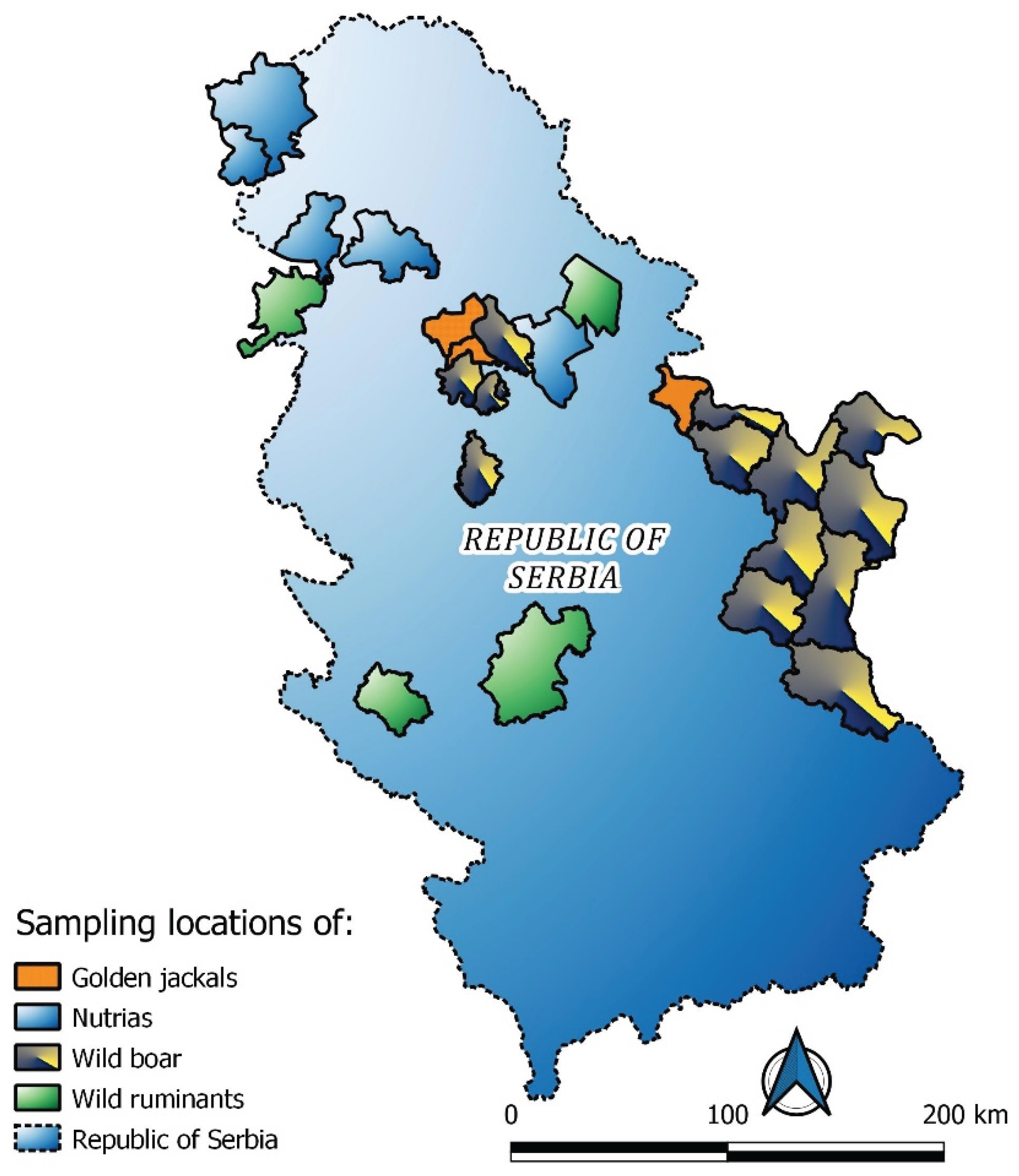

A total of 522 serum samples from wild animals were analysed, including wild boar (

Sus scrofa), roe deer (

Capreolus capreolus), red deer (

Cervus elaphus), golden jackal (

Canis aureus), and nutria (

Myocastor coypus). Samples were collected across Serbia (

Figure 1) during the winter of 2023/2024 from 19 hunting grounds, while nutrias were obtained along riverbanks. All animals were obtained during routine culling programs aimed at population control; therefore, no ethical approval was required. The location of the hunting grounds of material sampling in the Republic of Serbia is presented in

Figure 1.

Age classification of sampled animals was performed to distinguish juvenile and adult categories for epidemiological analysis. Classification was based on species-specific morphological and dental criteria. In nutria, body weight and length (≤3 kg or ≤45 cm indicating juveniles) were used. In wild boar, tooth eruption and wear patterns served as the main indicators (juveniles < 1 year, adults > 1 year). For jackals, body size, tooth wear, and reproductive maturity were considered (juveniles < 1 year, adults > 1 year). In wild ruminants, age determination relied on dentition, body size, and antler development (juveniles < 1 year, adults > 1 year) (

Table 1).

A non-probability convenience sampling method was used, selecting animals based on accessibility and availability. Sampling bias was reduced because all specimens came from animals culled during the same hunting season. Blood samples were obtained either directly from the thoracic cavity of freshly hunted animals or during veterinary health inspections. After spontaneous coagulation at room temperature, sera were separated by centrifugation (Eppendorf, Germany) at 2000 g for 10 minutes, decanted, and stored frozen until further analysis.

To detect specific anti-WNV antibodies, a multi-species blocking enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [

19] was used, following the manufacturer's recommendations. According to the producer validation data, the diagnostic sensitivity (Se) of this kit is 100% and the diagnostic specificity (Sp) is 98.4%. Prevalence, Lower Confidence Limits (CL) and Upper Confidence Limits were calculated by use of [

20], according to Wilson's confidence interval method and regarding a confidence level of 95% with desired precision of +/- 0,05. [

20] was also used for the calculation of true prevalence for an imperfect test with known Se and Sp of the test. To compare statistical significance between groups by species and age categories, we used the “Chi-squared test for contingency table from original data” in Epitools. We based our calculations on the desired 0.95 level of confidence.

3. Results

A total of 522 serum samples from five wild mammal species were tested, of which 165 were seropositive, resulting in an overall seroprevalence of 31.6% (TP = 30.5%; 95% CI: 0.27–0.35) (

Table 1). Among the examined species, the highest seroprevalence was detected in red deer, with 50.6% positive samples (TP = 48.8%; 95% CI: 0.42–0.58), followed by wild boars with 37.0% (TP = 36%; 95% CI: 0.28–0.47) and golden jackals with 32.4% (TP = 31.3%; 95% CI: 0.22–0.44). Lower seroprevalence values were observed in nutrias (11.9%, TP = 10.5%; 95% CI: 0.07–0.20) and roe deer (8.6%, TP = 7.2%; 95% CI: 0.03–0.15).

Seropositivity was more frequent among adults (136 positive; 33.7%) compared to juveniles (29 positive; 24.4%), indicating a clear age-related difference in exposure. Among juveniles, seroprevalence was generally lower, with the exception of juvenile golden jackals showing relatively high positivity (45.5%) compared to other species (

Table 1). For statistical significance between groups by species, we obtained a Chi-square of 48.876 - 67.9485 with P value < 0.0001, while for statistical significance between age categories, we obtained a Chi-square of 20.646 - 69.6801, and P value between < 0.0001 – 0.0003. The results of such high chi-square values as well as low P values indicate the existence of statistically significant differences between groups, as well as between age categories.

Table 2.

Seroprevalence of WNV antibodies in wild mammals by species and age group.

Table 2.

Seroprevalence of WNV antibodies in wild mammals by species and age group.

| Species |

Total Tested |

Total Positive (%) |

TP (%) |

95% CI (Lower–Upper) |

Adults Tested |

Adults Positive (%) |

Juveniles Tested |

Juveniles Positive (%) |

| Wild boar |

100 |

37 (37.0) |

36.0 |

0.28–0.47 |

53 |

23 (43.4) |

47 |

14 (29.8) |

| Nutria |

101 |

12 (11.9) |

10.5 |

0.07–0.20 |

87 |

10 (11.5) |

14 |

2 (14.3) |

| Golden jackal |

68 |

22 (32.4) |

31.3 |

0.22–0.44 |

57 |

17 (29.8) |

11 |

5 (45.5) |

| Red deer |

172 |

87 (50.6) |

48.8 |

0.42–0.58 |

137 |

81 (59.1) |

35 |

6 (17.1) |

| Roe deer |

81 |

7 (8.6) |

7.2 |

0.03–0.15 |

69 |

5 (7.2) |

12 |

2 (16.7) |

| Total |

522 |

165 (31.6) |

30.5 |

0.27–0.35 |

403 |

136 (33.7) |

119 |

29 (24.4) |

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the seroprevalence of WNV in various species of wild ungulates, golden jackals, and nutrias collected during a single hunting season using ELISA. The presence of WNV-specific IgG in older animals generally indicates past infection [

21]. However, a more precise sign of recent seasonal circulation is seropositivity in young, immature individuals born after the previous vector season. As expected, adults exhibited a higher seroprevalence compared to juveniles across all tested species, reflecting longer cumulative exposure to infected mosquito bites [

16]. Nonetheless, the detection of seropositive juveniles in wild boars, red deer, roe deer, jackals, and nutrias demonstrates that active transmission took place during the year of sampling.

Epidemiological data on WNV seroprevalence in nutrias remain scarce. Previous studies have reported antibodies in other rodents, including the fox squirrel (

Sciurus niger), eastern gray squirrel (

Sciurus carolinensis), groundhog (

Marmota monax), yellow-necked field mouse (

Apodemus flavicollis), and bank vole (

Myodes glareolus) [

6]. In our survey, nutrias showed a seroprevalence of 11.9%, with antibodies also confirmed in two immature individuals, further supporting evidence of recent seasonal infections in this invasive species. The detection of WNV antibodies in nutria was anticipated, as their typical habitats are also favoured by mosquito vectors. Seroprevalence in this invasive species may therefore provide useful insights into the geographic distribution of WNV beyond human settlements, particularly in coastal zones of stagnant water, as well as along lakes and riverbanks, which represent unpopulated habitats shared with vectors. However, the observed seroprevalence was lower than expected given their ecological niche, which may be attributable to additional environmental or host-related factors, such as the nutria's double coat comprising a soft, dense underfur and long guard hairs.

Across Europe, previous studies have generally reported low WNV seroprevalence in wild ungulates: 0% in wild boars from Poland [

9], 4–10% in several surveys [

22,

23,

24], and as lowas 4.04% in wild boars and 0.23% in red deer across multiple bioregions [

6]. Even the higher values documented in Spain, 21.9–26.6% in wild boars and 17.6–21.4% in red deer [

25], remain below our findings. Similarly, [

26,

27] reported 4–6% prevalence in wild boars, red deer, and roe deer. In contrast, our study revealed markedly higher true seroprevalence, reaching 36% in wild boars and 50.6% in red deer, while roe deer showed comparable values (7.2%). Comparable WNV seroprevalence results were reported by [

28] who found 49.1% positivity in red deer and 7.8% in roe deer populations. The slightly higher prevalence observed in our study suggests a more intense and persistent WNV circulation within the investigated regions, indicating ongoing virus activity that may exceed levels previously documented in other European wild ungulate populations.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate a substantially higher WNV seroprevalence in wild boars and red deer compared to previously reported European data, where prevalence typically ranged between 0% and 10% and only occasionally exceeded 20% [

22,

25,

26]. While our roe deer results (8.6%) were in line with earlier reports, the markedly elevated values observed in red deer (50.6%) and wild boars (37%) underscore an intensified circulation of WNV in Serbian ecosystems. These differences may reflect regional ecological factors, higher vector activity, or host–vector interactions unique to the study areas. Collectively, the results highlight the importance of wild ungulates and other wildlife species as sentinels for WNV monitoring in endemic regions.

5. Conclusions

This study provides new evidence of widespread WNV circulation in Serbian wildlife, with seroprevalence levels in wild boars and red deer exceeding those reported elsewhere in Europe. The detection of antibodies in both adult and juvenile individuals confirms recent viral activity and ongoing transmission. Our results emphasise the need for continuous, multi-species surveillance to better understand the epidemiology of WNV and to strengthen One Health approaches for early warning, risk assessment, and control of mosquito-borne diseases.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WNV |

West Nile Virus |

| CL |

Confidence Limits |

| Se |

Diagnostic sensitivity |

| Sp |

Diagnostic specificity |

| TP |

True Prevalence |

References

- Radojicic S, Zivulj A, Petrovic A, Nisavic J, Milicevic V, Sipetic-Grujicic S, Misic J, Korzeniowska M, Stanojevic S.(2021) Spatiotemporal Analysis of West Nile Virus Epidemic in South Banat District, Serbia, 2017–2019. Animals 2021, 11, 2951. [CrossRef]

- Simmonds P, Becher P, Bukh J, Gould EA, Meyers G, Monath T, Muerhoff S, Pletnev A, Rico-Hesse R, Smith DB, Stapleton JT, (2017) Ictv Report Consortium. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol. 2017 Jan;98(1):2-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guggemos HD, Fendt M, Hleike C, Heyde V, Mfune JKE, Borgemeister C, Junglen S,(2021) Simultaneous circulation of two WestNile virus lineage 2 clades and Bagazavirus in the Zambezi region, Namibia.PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 15(4):e0009311. [CrossRef]

- Marini G, Drakulovic B, Jovanovic V. Dagostin F, Wint W, Tagliapietra V, Vasic M. and Rizzoli A. (2024) Drivers and epidemiological patterns of West Nile virus in Serbia. Front. Public Health 12:1429583. [CrossRef]

- Nemeth N, Young G, Ndaluka C, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Komar N, Bowen R.(2009) Persistent West Nile virus infection in the house sparrow (Passer domesticus). Arch Virol. 2009;154(5):783-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root, J.J. Bosco-Lauth A.M. (2019) West Nile Virus Associations in Wild Mammals: An Update. Viruses. 2019 May 21;11(5):459. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Petersen L, Roehrig J, Sejvar J, (2009). Global Epidemiology of West Nile Virus. In: West Nile Encephalitis Virus Infection. Emerging Infectious Diseases of the 21st Century. Springer, New York, USA, 2009; pp. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kading, R. Borland E., Cranfield M., Powers A.; (2013) Prevalence of antibodies to alphaviruses and flaviviruses in free-ranging game animals and nonhuman primates in the greater Congo basin; Journal of wildlife diseases, vol. 49, no. 3, July 2013. [CrossRef]

- Niczyporuk J, Jabłonski A; Serologic Survey for West Nile Virus in Wild Boars (Sus scrofa) in Poland (2021) Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 57(1), 2021, pp. 168–171, Wildlife Disease Association 2021; [CrossRef]

- Miller D, Debra L, Radi A, Zaher A., Baldwin C and Dallas I; (2025.) Fatal West Nile Virus Infection in a White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus), Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 41(1) : 246-249. Published By: Wildlife Disease Association. [CrossRef]

- Schertler A, Rabitsch W, Moser D, Wessely J, Essl F. (2020) The potential current distribution of the coypu (Myocastor coypus) in Europe and climate change-induced shifts in the near future. NeoBiota 58: 129–160. [CrossRef]

- Auerswald H, Ruget A-S, Ladreyt H, In S, Mao S, Sorn S, Tum S, Duong V, Dussart P. Cappelle J. and Chevalier V. (2020) Serological Evidence for, Japanese Encephalitis and West Nile Virus Infections in Domestic Birds in, Cambodia. Front. Vet. Sci. 7:15. January 2020 | Volume 7 | Article 15. [CrossRef]

- Allen S, Jardine C., Hooper-McGrevy K, Ambagala A, Bosco-Lauth M, R. Kunkel M, Mead D, Nituch L, Ruder K, and Nemeth N. (2020) Serologic Evidence of Arthropod-Borne Virus Infections in Wild and Captive Ruminants in Ontario, Canada, Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 103(5), 2020, pp. 2100–2107. [CrossRef]

- Kvapil P, Racnik J, Kastelic M, Bártová E, Korva M, Jelovšek M, Avšic-Županc T. (2021) Sentinel Serological Study in Selected Zoo Animals to Assess Early Detection of West Nile and Usutu Virus Circulation in Slovenia. Viruses 2021, 13, 626. [CrossRef]

- Assaid N, Arich S, Ezzikouri S. Benjelloun, Dia M, Faye O, Akarid K., Beck C. Lecollinet S, Failloux AB, Sarih M. (2021) Serological evidence of West Nile virus infection in human populations and domestic birds in the Northwest of Morocco, Infectious Diseases, Volume 76, June 2021, 101646. [CrossRef]

- Magallanes S, Llorente F, Ruiz-López MJ, Martínez-de la Puente J, Soriguer R, Calderon J, Jímenez-Clavero MÁ, Aguilera-Sepúlveda P. Figuerola J. (2023) Long-term serological surveillance for West Nile and Usutu virus in horses in south-west Spain. One Health. Jun 12;17:100578. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vilibic-Cavlek T, Bogdanic M, Savic V, Hruskar Z, Barbic L, Stevanovic V, Antolasic L, Milasincic L, Sabadi D, Miletic G, Coric I, Mrzljak A, Listes E, Savini G. (2024) Diagnosis of West Nile virus infections: Evaluation of different laboratory methods. World J Virol 2024; 13(4).

- Šolaja S, Goletić Š, Veljović LJ, Glišić D. (2024) Complex patterns of WNV evolution: a focus on the Western Balkans and Central Europe Front. Vet. Sci., 20 November 2024, Volume 11 - 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ingezim. Available online: https://www.goldstandarddiagnostics.com/pub/media/productattachments/files/10WNVK3_Technical_sheet_westnile.pdf.

- Epitools. Available online: https://epitools.ausvet.com.au/.

- Veljović LJ, Maksimović Zorić J, Radosavljević V, Stanojević S, Žutić J, Kureljušić B, Pavlović.I, Jezdimirović N., Milićević V; (2020) Seroprevalence of West Nile fever virus in horses in the Belgrade epizootiological area. Veterinarski Glasnik, 2020. 74 (2): 194-201. [CrossRef]

- Kramer L, Styer L, and Ebel G. (2008) A Global Perspective on the Epidemiology of West Nile Virus. Annual Review of Entomology: Volume 53 Vol. 53:61-81, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Boadella, M. , Delgado I., Gutiérrez-Guzmán AV., Höfle U., and Gortázar C..: (2012) Do Wild Ungulates Allow Improved Monitoring of Flavivirus Circulation in Spain? Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases Vol: 12 No: 6. [CrossRef]

- Niedrig, M. , Mantke O., Altmann D., and Zeller H.; (2007) First international diagnostic accuracy study for the serological detection of West Nile virus infection; BMC Infectious Diseases 2007, 7:72. [CrossRef]

- Casades-Martí L, Cuadrado-Matías R, Peralbo-Moreno A, Baz-Flores S, Fierro Y, Ruiz-Fons F. Insights into the spatiotemporal dynamics of West Nile virus transmission in emerging scenarios. One Health. 2023 May 1;16:100557. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hubálek, Z. Juricová Z., Straková P., Blazejová H., Betásová L, and Rudolf. (2017) Serological Survey for West Nile Virus in Wild Artiodactyls, Southern Moravia (Czech Republic), Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases Vol. 17, No. 9 Published Online: 1 September 2017. [CrossRef]

- Halouzka J, Juricova Z, Jankova J, Hubalek Z. (2008) Serologic survey of wild boars for mosquito-borne viruses in South Moravia (Czech Republic): Veterinarni Medicina, 53, 2008 (5): 266–271 Vet Med - Czech, 2008, 53(5):266-271 |. [CrossRef]

- Milićević V, Sapundžić ZZ, Glišić D, Kureljušić B, Vasković N, Đorđević M, Mirčeta J. (2024) Cross-sectional serosurvey of selected infectious diseases in wild ruminants in Serbia. Res Vet Sci. 2024 Apr;170:105183. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).