Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

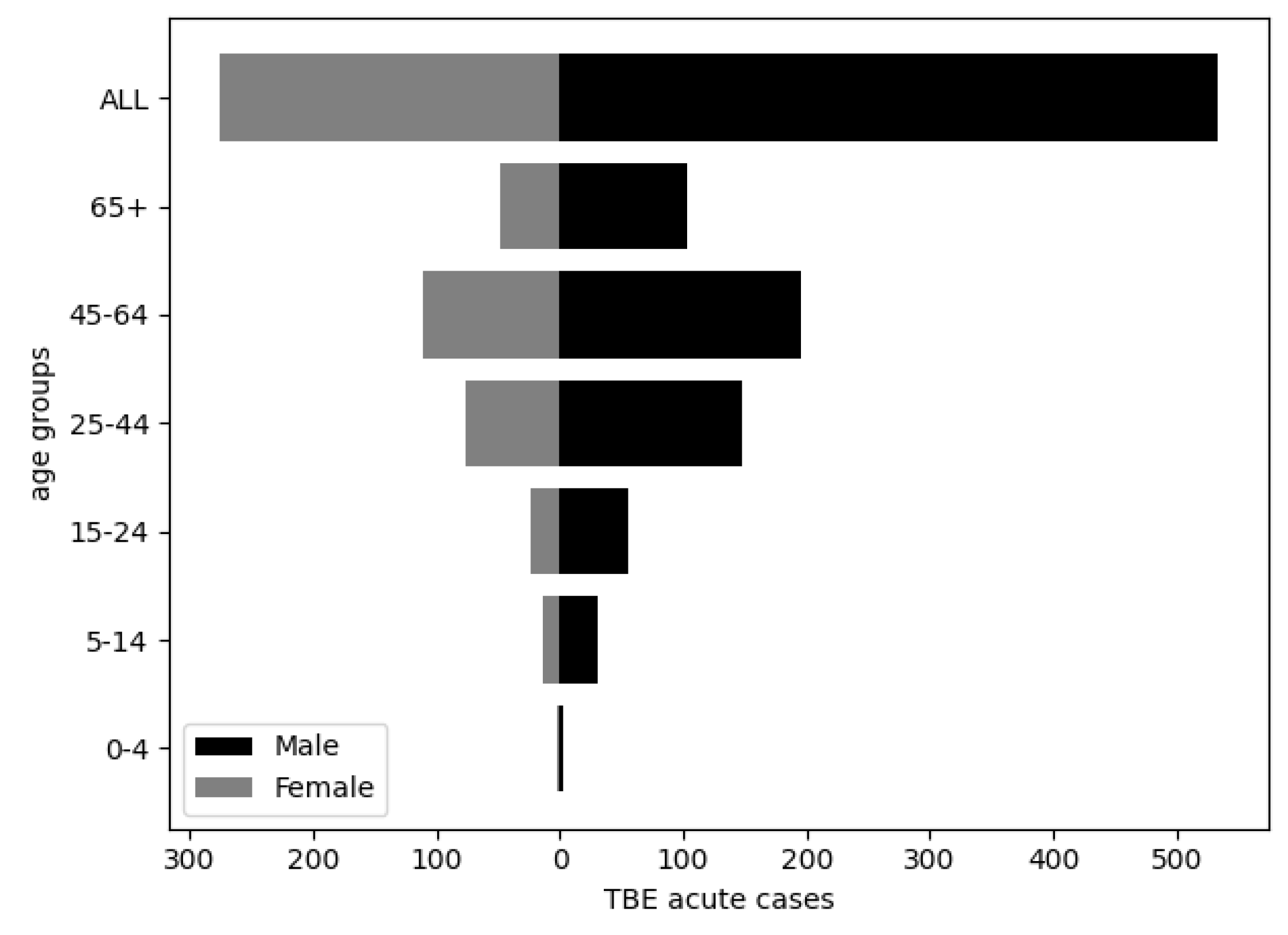

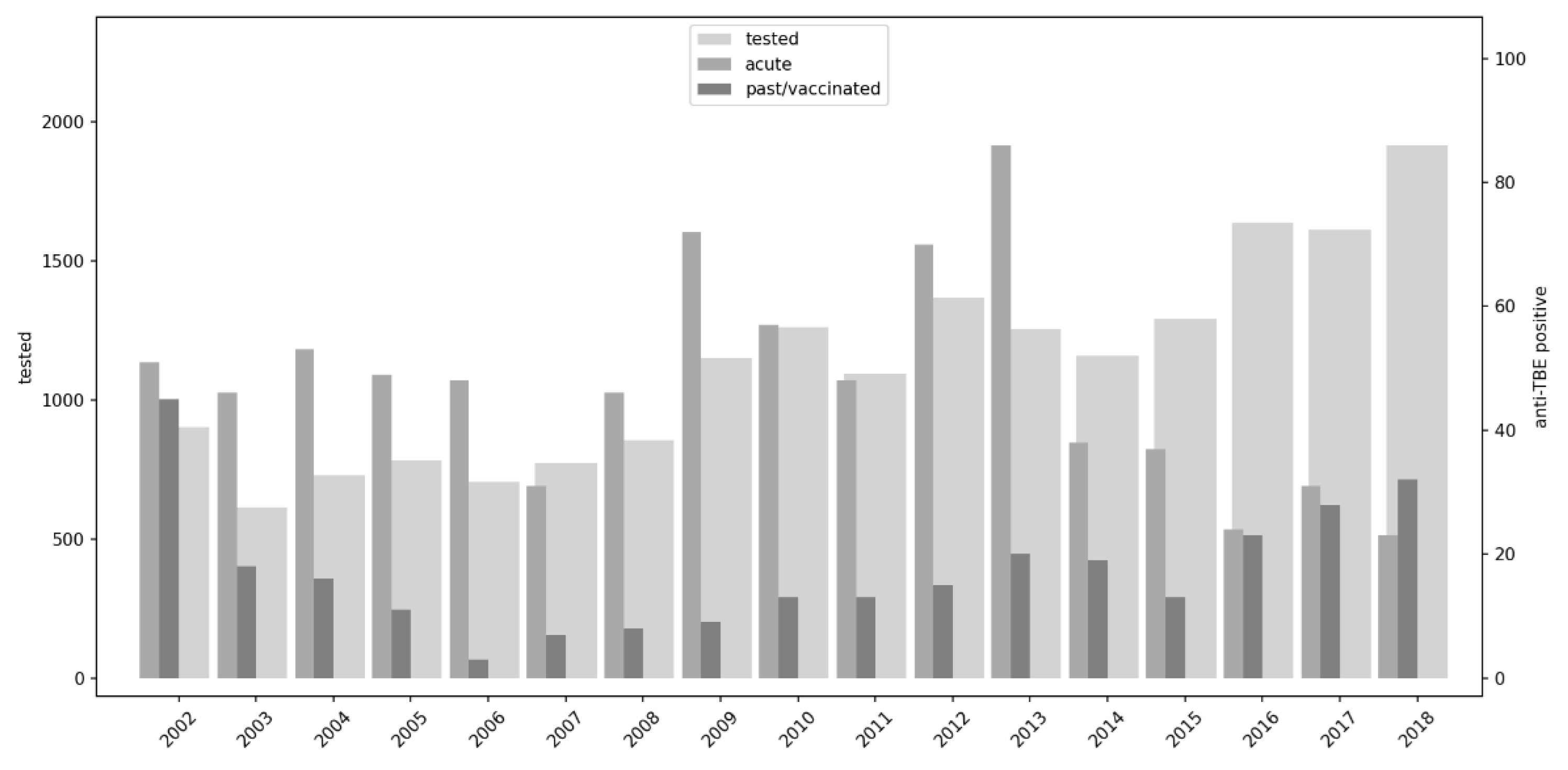

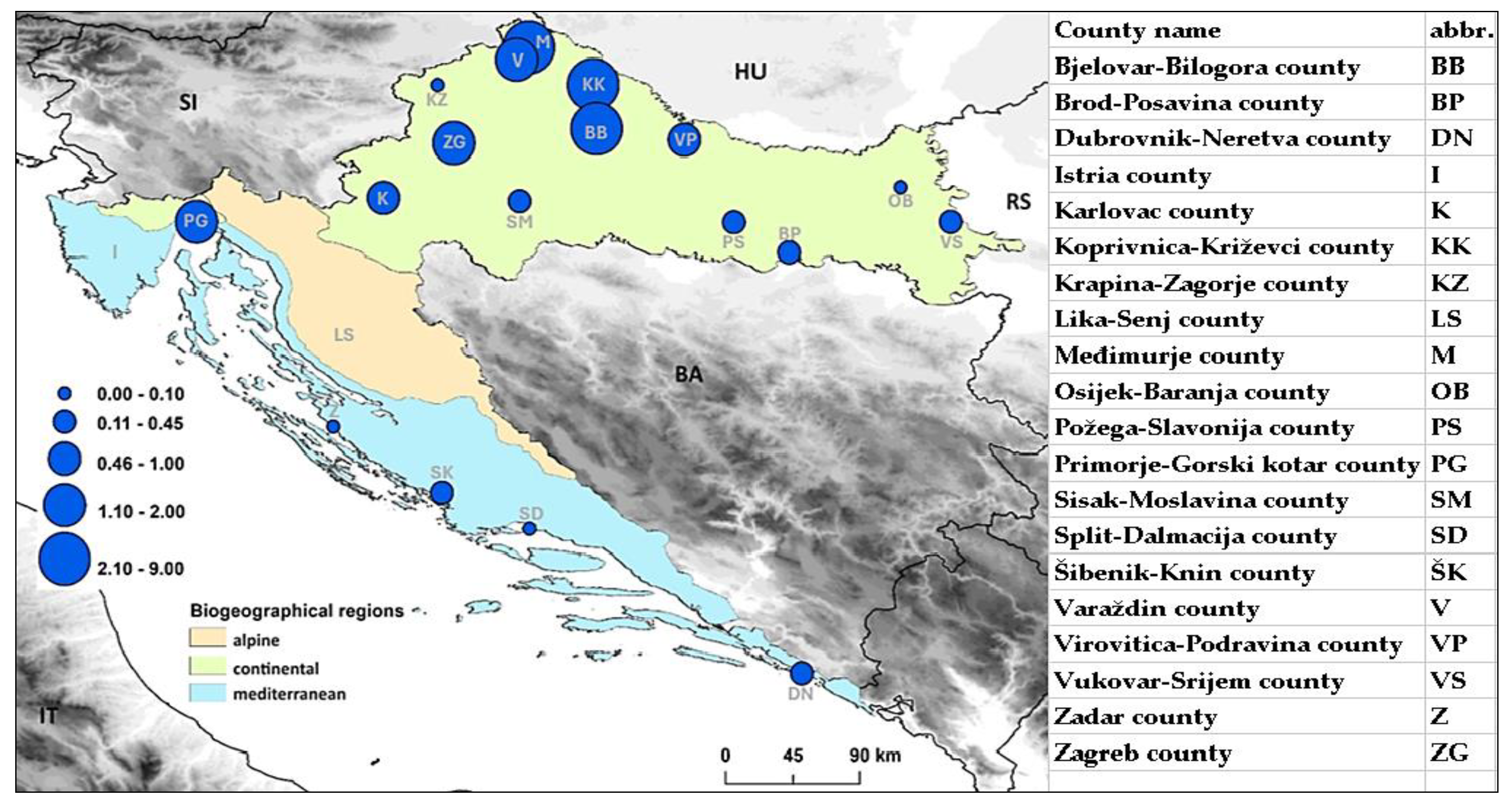

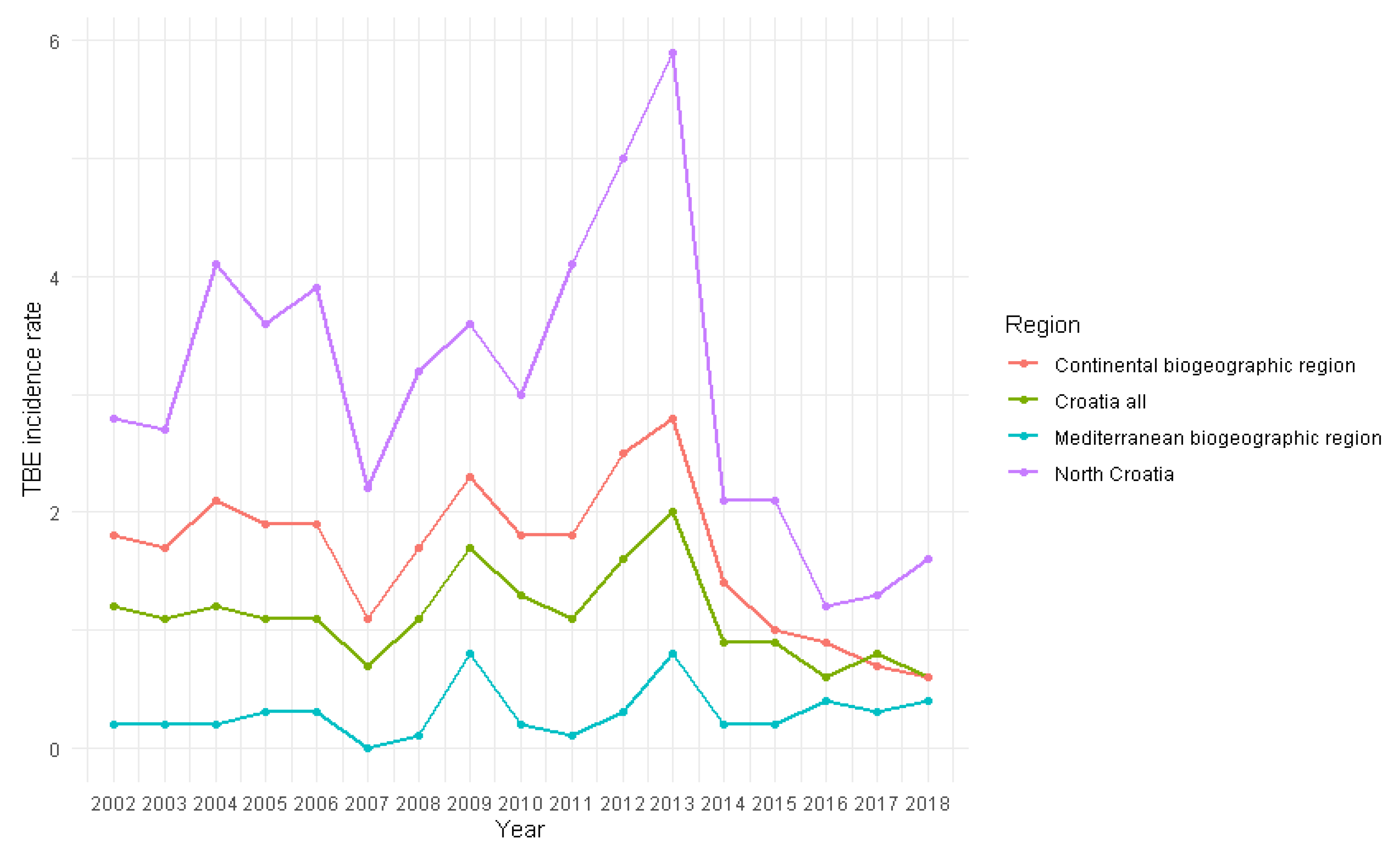

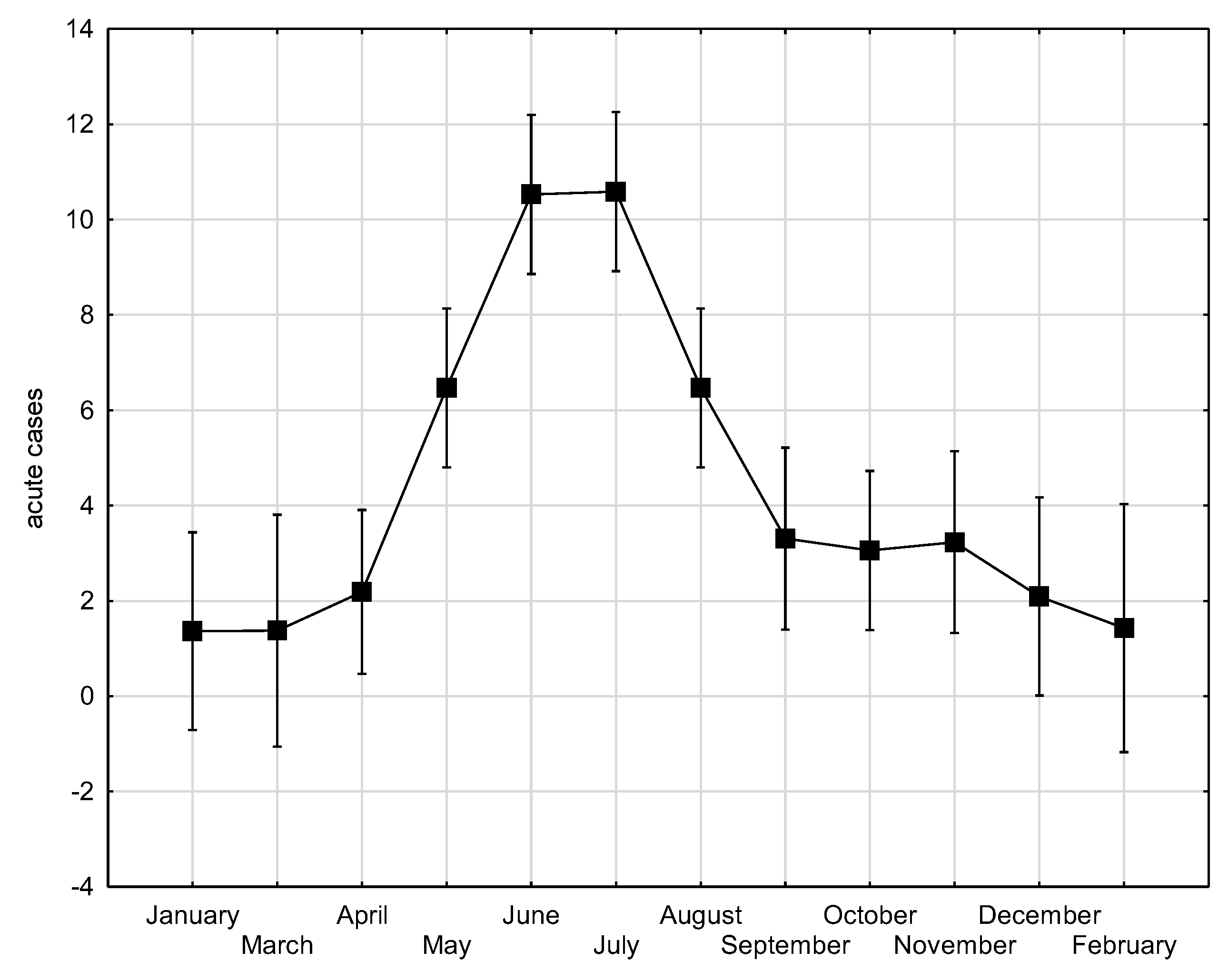

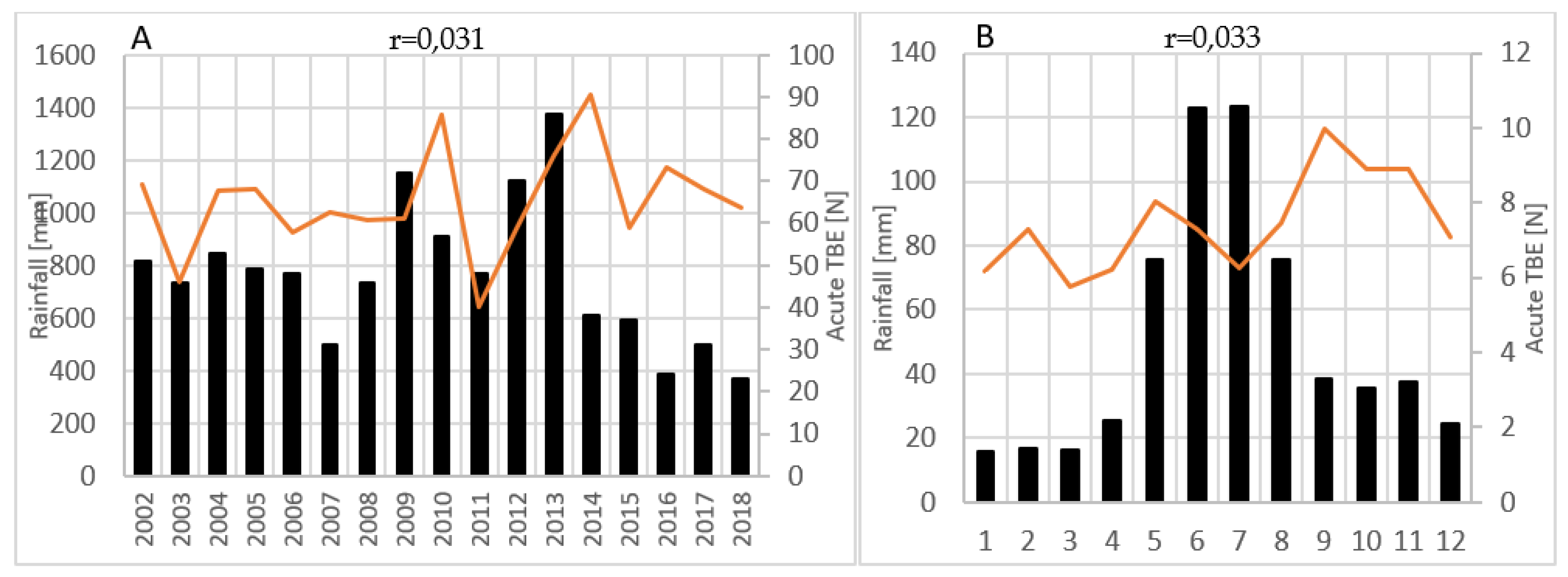

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is the most significant arboviral infection in Croatia. The aim of the study was to analyse and correlate 17-year TBE seroprevalence data with winter temperature, precipitation and wildlife abundance to identify possible patterns that can be predictive of TBE incidence. TBE diagnosis was based on IgM/IgG anti-TBE antibodies and individual clinical interpretation of the results. Of the 19,094 analysed patients, 4.2% had acute TBE, significantly more often in older age (p<0.001) and in men (p<0.001). Overall seroprevalence of TBE among the tested population was 5.8%, and varied annually from 2.8% to 10.7%. The mean acute TBE incidence rate was 1.1 per 100.000 population with significant regional differences: 1.7 in the continental vs. 0.2 and 0.5 in the Mediterranean and Alpine regions, respectively. Particularly high incidence of 3.1 was recorded in northern Croatia. TBE displayed a seasonal pattern, peaking in June and July. Moderate negative correlations were observed between TBE acute cases and winter temperatures from December to February (r=-0.461; p=0.062), relative rodent abundance (r=-0.414; p=0.098) and yearly precipitation from one year before (r=-0.401; p=0.123). Considerable efforts are needed to understand the impact on TBE incidence to improve disease prevention.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.1.1. TBE Cases

2.1.2. Rodent and Common Game Abundance

2.1.3. Winter Temperatures and Precipitation

2.2. Statistical Methodology and Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization, Vaccines against Tick-Borne Encephalitis: WHO Position Paper – Recommendations. Weekly epidemiological record 2021, 24, 241-256.

- Süss, J. Tick-borne encephalitis 2010: Epidemiology, risk areas, and virus strains in Europe and Asia—An overview. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases 2011, 2, 2-15. [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, L.; Vapalahti, O. Tick-borne encephalitis. The Lancet 2008, 371, 1861-1871. [CrossRef]

- Michelitsch, A.; Wernike, K.; Klaus, C.; Dobler, G.; Beer, M. Exploring the Reservoir Hosts of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus. Viruses 2019, 11, 669. [CrossRef]

- Šumilo, D.; Bormane, A.; Asokliene, L.; Vasilenko, V.; Golovljova, I.; Avsic-Zupanc, T.; Hubalek, Z.; Randolph, S.E. Socio-economic factors in the differential upsurge of tick-borne encephalitis in central and Eastern Europe. Reviews in Medical Virology 2008, 18, 81-95. [CrossRef]

- Šumilo, D.; Asokliene, L.; Avsic-Zupanc, T.; Bormane, A.; Vasilenko, V.; Lucenko, I.; Golovljova, I.; Randolph, S.E. Behavioural responses to perceived risk of tick-borne encephalitis: Vaccination and avoidance in the Baltics and Slovenia. Vaccine 2008, 26, 2580-2588. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, M.; Kříž, B.; Danielová, V.; Beneš, Č. Sudden increase in tick-borne encephalitis cases in the Czech Republic, 2006. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2008, 298, 81-87. [CrossRef]

- Randolph, S.E.; On Behalf Of The Eden-Tbd Sub-Project Team. Human activities predominate in determining changing incidence of tick-borne encephalitis in Europe. Eurosurveillance 2010, 15. [CrossRef]

- Kunze, M.; Banović, P.; Bogovič, P.; Briciu, V.; Čivljak, R.; Dobler, G.; Hristea, A.; Kerlik, J.; Kuivanen, S.; Kynčl, J.; et al. Recommendations to Improve Tick-Borne Encephalitis Surveillance and Vaccine Uptake in Europe. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1283. [CrossRef]

- Cocchio, S.; Bertoncello, C.; Napoletano, G.; Claus, M.; Furlan, P.; Fonzo, M.; Gagliani, A.; Saia, M.; Russo, F.; Baldovin, T.; et al. Do We Know the True Burden of Tick-Borne Encephalitis? A Cross-Sectional Study. Neuroepidemiology 2020, 54, 227-234. [CrossRef]

- Pilz, A.; Erber, W.; Schmitt, H.-J. Vaccine uptake in 20 countries in Europe 2020: Focus on tick-borne encephalitis (TBE). Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases 2023, 14, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Hansson, M.E.A.; Örvell, C.; Engman, M.-L.; Wide, K.; Lindquist, L.; Lidefelt, K.-J.; Sundin, M. Tick-borne encephalitis in childhood. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2011, 30, 355-357. [CrossRef]

- Schley, K.; Friedrich, J.; Pilz, A.; Huang, L.; Balkaran, B.L.; Maculaitis, M.C.; Malerczyk, C. Evaluation of under-testing and under-diagnosis of tick-borne encephalitis in Germany. BMC Infectious Diseases 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Brinkley, C.; Nolskog, P.; Golovljova, I.; Lundkvist, Å.; Bergström, T. Tick-borne encephalitis virus natural foci emerge in western Sweden. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2008, 298, 73-80. [CrossRef]

- Tonteri, E.; Kurkela, S.; Timonen, S.; Manni, T.; Vuorinen, T.; Kuusi, M.; Vapalahti, O. Surveillance of endemic foci of tick-borne encephalitis in Finland 1995–2013: evidence of emergence of new foci. Eurosurveillance 2015, 20. [CrossRef]

- Topp, A.-K.; Springer, A.; Dobler, G.; Bestehorn-Willmann, M.; Monazahian, M.; Strube, C. New and Confirmed Foci of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus (TBEV) in Northern Germany Determined by TBEV Detection in Ticks. Pathogens 2022, 11, 126. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, M.; Danielová, V.; Kříž, B.; Jirsa, A.; Nožička, J. Shift of the Tick Ixodes ricinus and Tick-Borne Encephalitis to Higher Altitudes in Central Europe. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2003, 22, 327-328. [CrossRef]

- Jaenson, T.G.; Jaenson, D.G.; Eisen, L.; Petersson, E.; Lindgren, E. Changes in the geographical distribution and abundance of the tick Ixodes ricinus during the past 30 years in Sweden. Parasites & Vectors 2012, 5, 8. [CrossRef]

- Stjernberg, L.; Holmkvist, K.; Berglund, J. A newly detected tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) focus in south-east Sweden: A follow-up study of TBE virus (TBEV) seroprevalence. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases 2008, 40, 4-10. [CrossRef]

- Smura, T.; Tonteri, E.; Jääskeläinen, A.; Von Troil, G.; Kuivanen, S.; Huitu, O.; Kareinen, L.; Uusitalo, J.; Uusitalo, R.; Hannila-Handelberg, T.; et al. Recent establishment of tick-borne encephalitis foci with distinct viral lineages in the Helsinki area, Finland. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2019, 8, 675-683. [CrossRef]

- Achazi, K.; Růžek, D.; Donoso-Mantke, O.; Schlegel, M.; Ali, H.S.; Wenk, M.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Ohlmeyer, L.; Rühe, F.; Vor, T.; et al. Rodents as Sentinels for the Prevalence of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2011, 11, 641-647. [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, P.J.; Obiegala, A.; Schmuck, H.M.; Dobler, G.; Chitimia-Dobler, L.; Pfeffer, M. Seroprevalence of Tick-Borne Encephalitis (TBE) Virus Antibodies in Wild Rodents from Two Natural TBE Foci in Bavaria, Germany. Pathogens 2023, 12, 185. [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, M.; Hagedorn, P.; Schulze, Y.; Hellenbrand, W.; Pfeffer, M.; Niedrig, M. Review: Sentinels of tick-borne encephalitis risk. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases 2015, 6, 592-600. [CrossRef]

- Jaenson, T.G.T.; Petersson, E.H.; Jaenson, D.G.E.; Kindberg, J.; Pettersson, J.H.O.; Hjertqvist, M.; Medlock, J.M.; Bengtsson, H. The importance of wildlife in the ecology and epidemiology of the TBE virus in Sweden: incidence of human TBE correlates with abundance of deer and hares. Parasites & Vectors 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- Knap, N.; Avšič-Županc, T. Correlation of TBE Incidence with Red Deer and Roe Deer Abundance in Slovenia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66380. [CrossRef]

- Tkadlec, E.; Václavík, T.; Široký, P. Rodent Host Abundance and Climate Variability as Predictors of Tickborne Disease Risk 1 Year in Advance. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2019, 25, 1738-1741. [CrossRef]

- SLE https://sle.mps.hr/.

- Gannon, WL.; Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. Journal of Mammalogy 2007, 88, 809-823.

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population, Households and Apartments 2021; Croatian Bureau of Statistics: 2021.

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics, Population estimate of the Republic of Croatia in 2021; Croatian Bureau of Statistics: 2021.

- Borčić, B.; Kaić, B.; Kralj, V. Some epidemiological data on TBE and Lyme borreliosis in Croatia. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie 1999, 289, 540-547. [CrossRef]

- Vilibic-Cavlek, T.; Krcmar, S.; Bogdanic, M.; Tomljenovic, M.; Barbic, L.; Roncevic, D.; Sabadi, D.; Vucelja, M.; Santini, M.; Hunjak, B. An Overview of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Epidemiology in Endemic Regions of Continental Croatia, 2017–2023. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 386. [CrossRef]

- Van Heuverswyn, J.; Hallmaier-Wacker, L.K.; Beauté, J.; Gomes Dias, J.; Haussig, J.M.; Busch, K.; Kerlik, J.; Markowicz, M.; Mäkelä, H.; Nygren, T.M.; et al. Spatiotemporal spread of tick-borne encephalitis in the EU/EEA, 2012 to 2020. Eurosurveillance 2023, 28. [CrossRef]

- Vesenjak-Hirjan, J. Tick-borne encephalitis in Croatia. JAZU 1976, 372, 1-9.

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Croatian health statistics yearbook 2018; Croatian Institute of Public Health: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019; p. 197.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Tick-borne encephalitis Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. ECDC Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023.

- Dumpis, U.; Crook, D.; Oksi, J. Tick-Borne Encephalitis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1999, 28, 882-890. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.; Mahling, M.; Pfister, K. Abundance and seasonal activity of questing Ixodes ricinus ticks in their natural habitats in southern Germany in 2011. Journal of Vector Ecology 2014, 39, 56-65. [CrossRef]

- Voyiatzaki, C.; Papailia, S.I.; Venetikou, M.S.; Pouris, J.; Tsoumani, M.E.; Papageorgiou, E.G. Climate Changes Exacerbate the Spread of Ixodes ricinus and the Occurrence of Lyme Borreliosis and Tick-Borne Encephalitis in Europe—How Climate Models Are Used as a Risk Assessment Approach for Tick-Borne Diseases. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 6516. [CrossRef]

- Dautel, H.; Dippel, C.; Kämmer, D.; Werkhausen, A.; Kahl, O. Winter activity of Ixodes ricinus in a Berlin forest. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2008, 298, 50-54. [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, E.; Gustafson, R. Tick-borne encephalitis in Sweden and climate change. The Lancet 2001, 358, 16-18. [CrossRef]

- Simonović Z.; Učakar V.; Praprotnik M. In TBE-The Book; Dobler, G.; Erber, W.; Schmitt H.J. Global Health Press, Singapore, 2024; Volume 7, Chapter 13, p. 326-331.

- Randolph, S.E.; Asokliene, L.; Avsic-Zupanc, T.; Bormane, A.; Burri, C.; Gern, L.; Golovljova, I.; Hubalek, Z.; Knap, N.; Kondrusik, M.; et al. Variable spikes in tick-borne encephalitis incidence in 2006 independent of variable tick abundance but related to weather. Parasites & Vectors 2008, 1, 44. [CrossRef]

- Danielová, V.; Benes, C. Possible role of rainfall in the epidemiology of tick-borne encephalitis. Central European journal of public health 1997, 5, 151-154.

- Haemig, P.D.; Sjöstedt De Luna, S.; Grafström, A.; Lithner, S.; Lundkvist, Å.; Waldenström, J.; Kindberg, J.; Stedt, J.; Olsén, B. Forecasting risk of tick-borne encephalitis (TBE): Using data from wildlife and climate to predict next year's number of human victims. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases 2011, 43, 366-372. [CrossRef]

- Vollack, K.; Sodoudi, S.; Névir, P.; Müller, K.; Richter, D. Influence of meteorological parameters during the preceding fall and winter on the questing activity of nymphal Ixodes ricinus ticks. International Journal of Biometeorology 2017, 61, 1787-1795. [CrossRef]

- Bolzoni, L.; Rosà, R.; Cagnacci, F.; Rizzoli, A. Effect of deer density on tick infestation of rodents and the hazard of tick-borne encephalitis. II: Population and infection models. International Journal for Parasitology 2012, 42, 373-381. [CrossRef]

- Rizzoli, A.; Hauffe, H.C.; Tagliapietra, V.; Neteler, M.; Rosà, R. Forest Structure and Roe Deer Abundance Predict Tick-Borne Encephalitis Risk in Italy. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4336. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, L.; Maffey, G.L.; Ramsay, S.L.; Hester, A.J. The effect of deer management on the abundance of Ixodes ricinus in Scotland. Ecological Applications 2012, 22, 658-667. [CrossRef]

- Ostfeld, R.S.; Keesing, F. Biodiversity series: The function of biodiversity in the ecology of vector-borne zoonotic diseases. Canadian Journal of Zoology 2000, 78, 2061-2078. [CrossRef]

- Bjedov, L.; Tadin, A.; Margaletić, J.; Turk, N.; Markotić, A.; Vucelja, M.; Labaš, N.; Štritof, Z.; Habuš, J.; Svoboda, P. Influence of beech mast on small rodent populations and hantavirus prevalence in Nacional Park „Plitvice lakes“ and Nature Park „Medvednica“. Šumarski list 2016, 140, 455-463. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.S. Seed production and outbreaks of non-cyclic rodent populations in deciduous forests. Oecologia 1982, 54, 184-192. [CrossRef]

|

Period Temperature |

JANUARY mean |

DECEMBER-FEBRUARY mean |

JANUARY minimum |

YEARLY minimum |

||||

| r* | p- value | r | p- value | r | p- value | r | p- value | |

|

ZAGREB COUNTY acute TBE cases |

-0.251 | 0.330 | -0.340 | 0.181 | -0.048 | 0.852 | -0.173 | 0.506 |

|

CROATIA acute TBE cases |

-0.303 | 0.236 | -0.461 | 0.062 | -0.122 | 0.640 | -0.170 | 0.512 |

| ZAGREB COUNTY acute TBE and one year back temperature correlation | 0.207 | 0.425 | 0.023 | 0.928 | 0.430 | 0.085 | -0.013 | 0.958 |

| CROATIA acute TBE and one year back temperature correlation | 0.169 | 0.515 | -0.132 | 0.613 | 0.364 | 0.151 | -0.061 | 0.814 |

| Game species | Rodents | Roe deer | Red deer | Wild boar | Common pheasant | |||||

| r* | p- value | r | p- value | r | p- value | r | p- value | r | p- value | |

| Acute TBE | -0.414 | 0.098 | -0.208 | 0.422 | -0.334 | 0.189 | -0.248 | 0.337 | -0.354 | 0.163 |

|

Acute TBE and one year back data correlation |

-0.206 | 0.443 | -0.206 | 0.443 | -0.186 | 0.488 | -0.280 | 0.293 | -0.251 | 0.347 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).