Submitted:

05 May 2024

Posted:

06 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Diversity of the rodent Fauna of Saudi Arabia

3.2. Zoogeographical affinities of the rodents of Saudi Arabia

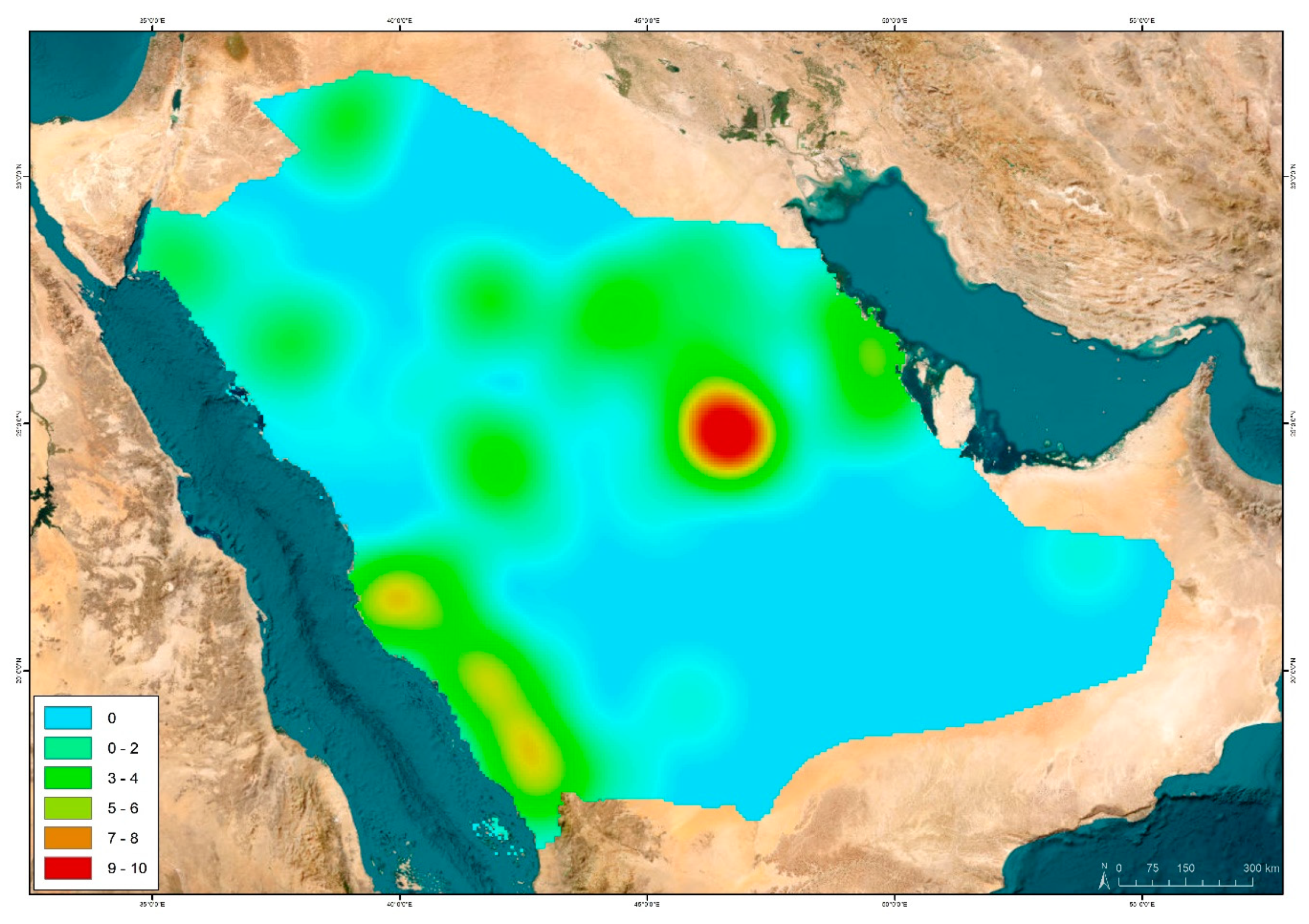

3.3. Species richness of rodents in Saudi Arabia

3.4. Conservation of rodents in Saudi Arabia

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Locality | N | E | Locality | N | E | |

| Abha | 18° 14' | 42° 31' | Kamis Mushayat | 18° 18' | 42° 44' | |

| Abqaiq | 25° 57' | 49° 41' | Karan Island | 27° 43' | 49° 50' | |

| Abu Ali Island | 27° 20' | 49° 33' | Khulays | 22° 09' | 43° 55' | |

| Abu Hadriya | 27° 05' | 49° 00' | Kushm Buwaybiyat | 25° 12' | 46° 52' | |

| Adama | 19° 19' | 42° 04' | Kushm Dibi | 24° 18' | 46° 09' | |

| Adnan | 20° 26' | 41° 31' | Luga | 29° 46' | 42° 38' | |

| Adwa | 27° 20' | 42° 15' | Mahazat as-Sayd | 22° 14' | 41° 50' | |

| Aga | 27° 26' | 41° 35' | Makkah-Lith | 21° 22' | 39° 38' | |

| Ajibba | 27° 20' | 44° 20' | Maqna | 28° 24' | 34° 45' | |

| Al Aba Oasis | 26° 42' | 49° 46' | Medain Salih | 26° 50' | 38° 00' | |

| Al Arf | 22° 01' | 40° 55' | Mekka by pass | 21° 15' | 39° 42' | |

| Al Azizah | 18° 13' | 42° 25' | Nabek | 24° 27' | 50° 49' | |

| Al Baha | 20° 01' | 41° 28' | Nabhaniyah | 25° 51' | 43° 04' | |

| al Beda’a | 28° 29' | 35° 02' | Najran | 17° 30' | 44° 20' | |

| Al Daba’ah | 28° 44' | 37° 58' | Neom | 28° 05' | 35° 29' | |

| Al Dalhan | 18° 01' | 43° 24' | Nuayriyah | 27° 32' | 48° 24' | |

| Al Hadda | 21° 26' | 39° 35' | Qaisumah | 28° 20' | 46° 06' | |

| Al Haniq | 19° 45' | 41° 57' | Qalat Al Muazzam | 27° 44' | 37° 30' | |

| Al Jawf | 29° 52' | 39° 26' | Qasab | 24° 14' | 38° 53' | |

| Al Khardj | 23° 55' | 47° 30' | Qbah | 27° 24' | 44° 20' | |

| Al Khubra | 25° 05' | 43° 39' | Qubat Al Zbair | 24° 52' | 39° 56' | |

| Al Khunfa | 28° 38' | 39° 19' | Qunfidah | 19° 09' | 41° 07' | |

| Al Masgi | 17° 58' | 42° 52' | Quwaywiyah | 23° 27' | 44° 39' | |

| Al Na’amah | 20° 14' | 41° 16' | Ras al-Abkhara | 27° 24' | 49° 14' | |

| Al Qarrah | 18° 07' | 42° 42' | Ras az Zaur | 27° 29' | 49° 12' | |

| Al Qasab | 25° 24' | 45° 47' | Raudha Tinhat | 26° 15' | 46° 00' | |

| Al Saiyarat | 27° 10' | 44° 50' | Raydah Protected Area | 18° 11' | 42° 24' | |

| Al Sarhan | 18° 16' | 42° 22' | Rijal Alma’a | 18° 09' | 42° 09' | |

| Al Souda | 18° 15' | 42° 24' | Risayah | 18° 57' | 42° 11' | |

| Al Thumamah | 25° 22' | 46° 36' | Riyadh | 24° 30' | 38° 49' | |

| Al Uquar | 25° 39' | 50° 13' | Rumah | 25° 37' | 47° 07' | |

| Al Wajh | 26° 20' | 37° 30' | Rumaihiya | 25° 30' | 47° 00' | |

| Alagan | 28° 23' | 36° 33' | Safaha Desert | 27° 19' | 42° 23' | |

| Alogl | 18° 34' | 42° 32' | Saja/Umm Ar-Rimth | 22° 30' | 42° 28' | |

| Alous | 18° 26' | 42° 30' | Salim | 23° 06' | 42° 18' | |

| Alzobara | 27° 50' | 41° 70' | Sanam | 23° 42' | 44° 45' | |

| An Namas | 19° 11' | 42° 19' | Sarhan | 18° 16' | 42° 22' | |

| Anaiza | 26° 05' | 44° 03' | Sha’ib Al Shoki | 25° 42' | 45° 51' | |

| Ar Rayn | 23° 32' | 45° 30' | Shaib al Tawqi | 25° 30' | 46° 33' | |

| Artawiya | 26° 30' | 45° 30' | Shaib Hajlil | 27° 30' | 44° 30' | |

| Ash Sharayi | 21° 40' | 40° 40' | Shaib Hanjur | 18° 15' | 42° 45' | |

| Asir National Park | 18° 12' | 42° 29' | Sharma | 28° 01' | 35° 13' | |

| Athnen | 18° 46' | 42° 16' | Shaybah | 22° 32' | 53° 58' | |

| Bahara | 21° 23' | 39° 27' | Summan Plateau | 27° 00' | 47° 00' | |

| Balum wells | 27° 15' | 44° 00' | SW Al Ula | 26° 38' | 37° 54' | |

| Bani Musayqirah | 20° 21' | 44° 30' | Tabuk | 28° 23' | 36° 36' | |

| Bani Sar | 20° 08' | 41° 45' | Taif | 21° 15' | 40° 21' | |

| Barazan | 27° 52' | 41° 70' | Tala’a | 18° 04' | 43° 57' | |

| between Abha-Al Darb | 18° 01' | 42° 25' | Tanomah | 18° 55' | 42° 09' | |

| Birka | 27° 30' | 44° 30' | Thamami wells | 27° 40' | 45° 00' | |

| Bsitah | 30° 44’ | 38° 31’ | Thamniya | 18° 01' | 42° 45' | |

| Buridah | 26° 20' | 43° 59' | Todiah | 24° 12' | 48° 03' | |

| Dailami | 20° 20' | 42° 40' | Tumeir | 25° 43' | 45° 51' | |

| Dammam-Dhahran Rd. | 26° 16' | 49° 59' | Turaif | 31° 39' | 38° 39' | |

| Dar el Harma | 26° 50' | 38° 20' | Tuwaiq Escarpment | 24° 23' | 46° 30' | |

| Dauhat ad Dafi | 27° 03' | 49° 24' | Umm Ad Dabah | 23° 47' | 45° 04' | |

| Dauhat al Musallamiya | 27° 26' | 49° 12' | Uruq Bani Ma’arid | 19° 20' | 45° 54' | |

| Dirab | 24° 29' | 46° 36' | Wadi Amag | 18° 40' | 42° 17' | |

| Duba | 27° 21' | 35° 48' | Wadi Arsha | 19° 45' | 41° 36' | |

| Eljameayein | 27° 29' | 41° 41' | Wadi As Sulai | 24° 36' | 46° 55' | |

| Elkhomashiya | 27° 28' | 41° 42' | Wadi Awsat | 24° 18' | 46° 29' | |

| Farasan Al-Kebir | 16° 42' | 41° 58' | Wadi Bin Hashbal | 18° 58' | 43° 06' | |

| Farasan Island | 16° 44' | 41° 50' | Wadi Dalaghan | 18° 02' | 42° 50' | |

| Fayfa | 17° 15' | 43° 06' | Wadi Eia | 18° 52' | 42° 28' | |

| Gariya | 27° 35' | 47° 40' | Wadi Habagah | 29° 47' | 42° 40' | |

| Hafir Kishb | 22° 49' | 41° 08' | Wadi Hanifah | 24° 35' | 46° 42' | |

| Hafr Al Batin | 28° 12' | 46° 07' | Wadi Hiswa | 18° 15' | 42° 28' | |

| Hail | 27° 31' | 41° 45' | Wadi Hizma | 18° 05' | 43° 56' | |

| Hamid | 18° 48' | 42°56' | Wadi Hureimala | 25° 06' | 46° 05' | |

| Harrart Al Harrah | 30° 56' | 39° 11' | Wadi Karj | 24° 21' | 47° 11' | |

| Hazm al Faidah | 27° 17' | 49°1 0' | Wadi Karrar | 21° 18' | 40° 07' | |

| Hazm an-Nuquria | 27° 18' | 49° 17' | Wadi Khumra | 24° 55' | 46° 11' | |

| Hesua | 18° 14' | 42° 22' | Wadi Liya | 21° 15' | 40° 20' | |

| Hijla | 18° 15' | 42° 38' | Wadi Nissah | 24° 12' | 46° 04' | |

| Hofuf | 21° 30' | 39° 12' | Wadi Qatan | 18° 07' | 44° 07' | |

| Ibex Reserve | 23° 21' | 46° 26' | Wadi Rasid | 24° 17' | 46° 16' | |

| Jabal Al Alam | 25° 36' | 41° 04' | Wadi Sanakhah | 18° 01' | 44° 07' | |

| Jabal Al Aswad | 17° 39' | 42° 39' | Wadi Shaib Luha | 24° 25' | 46° 48' | |

| Jabal Ammariyah | 24° 48' | 46° 14' | Wadi Sharayi | 21° 30' | 39° 55' | |

| Jabal Banban | 25° 23' | 46° 36' | Wadi Shija | 24° 51' | 46° 10' | |

| Jabal Farrash | 19° 37' | 43° 26' | Wadi Shuqub | 20° 40' | 41° 15' | |

| Jabal Maniq | 24° 19' | 46° 07' | Wadi Sirhan | 18° 16' | 42° 22' | |

| Jabal Shada | 19° 50' | 41° 18' | Wadi Thalham | 18° 24' | 44° 08' | |

| Jabal Shar | 27° 23' | 35° 27' | Wadi Turabah | 20° 37' | 41° 17' | |

| Jabal Thamamah | 25° 21' | 46° 51' | Wadi Uranah | 21° 21' | 39° 57' | |

| Jana Island | 27° 22' | 49° 18' | Wadi Wajj | 21° 10' | 40° 16' | |

| Jeddah | 21° 30' | 39°12' | Wosanib | 18° 34' | 42° 23' | |

| Jizan | 16° 56' | 42°33' | ||||

| Jubail | 26°57' | 49° 34' | ||||

References

- Wilson, D.; Lacher, T.; Mittermeier, R. Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 6. Lagomorphs and Rodents I. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, 2016, 987p.

- Wilson, D.; Lacher, T.; Mittermeier, R. Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 7. Rodents II. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, 2017, 1008p.

- Davidson, A.D.; Lightfoot, D.C.; McIntyre, J.L. Engineering rodents create key habitat for lizards. J. Arid Environ. 2008, 72, 2142–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, W.G.; Kay, F.R. Biopedturbation by mammals in deserts: a review. J. Arid Environ. 1999, 41, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheesman, D.R.E.; Hinton, M.A.C. On the mammals collected in the desert of Central Arabia by Major R. E. Cheesman. Ann. Mag. nat. Hist. 1924, 14, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesey-Fitzgerald, D. Notes on some rodents from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 1953, 51, 424–428. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.E. , Lewis, J.H. & Harrison, D.L. On a collection of mammals from northern Saudi Arabia. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1965, 144, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, D.; Nader, I.A. Pygmy shrew and rodents from the Near East. Senck. biol. 1983, 64, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, K. Noteworthy Mammal records from the Summan Plateau / NE Saudi Arabia. Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien 1988, 90, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Seddo, P.J.; Heezik, Y.; Nader, I.A. Mammals of the Harrat al-Harrah protected area, Saudi Arabia. Zool. Middle East 1997, 14, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, M.W.; Shah, M.S.; Shobrak, M. Rodent trapping in the Saja/Umm Ar-Rimth Protected Area of Saudi Arabia using two different trap types. Zool. Middle East 2008, 43, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paray, B.A.; Al-Sadoon, M.K. A survey of mammal diversity in the Turaif province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi-Said, M.; Al-Zein, M.S. Rodents diversity in Wadi As Sulai, Riyadh Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Jordan J. Nat. Hist. 2022, 9, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Buttiker, W.; Harrison, D. L. Mammals of Saudi Arabia. On a collection of Rodentia from Saudi Arabia. Fauna of Saudi Arabia 1982, 4, 488–502. [Google Scholar]

- Nader, I.A.; Kock, D.; Al-Khalili, A.D. Eliomys melanurus (Wagner, 1839) and Praomys fumatus (Peters, 1878) from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Mamnmalia: Rodentia). Senck. biol. 1983, 63, 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khalili, A.D.; Delany, M.J.; Nader, I.A. The ecology of the rock rat, Praomys fumatus yemeni Sanborn and Hoogstraal, in Saudi Arabia. Mammalia 1988, 52, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarli, J.; Lutermann, H.; Alagaili, A.N.; Mohammed, O.B.; Bennett, N.C. Reproductive patterns in the Baluchistan gerbil, Gerbillus nanus (Rodentia: Muridae), from western Saudi Arabia: The role of rainfall and temperature. J. Arid Environ. 2015, 113, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaili, A.N.; Mohammed, O.B.; Bennett, N.C.; Oosthuizen, M.K. Now you see me, now you don’t: The locomotory activity rhythm of the Asian garden dormouse (Eliomys melanurus) from Saudi Arabia. Mamm. Biol. 2014, 79, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaili, A.N.; Mohammed, O.B.; Bennett, N.C.; Oosthuizen, M.K. Down in the Wadi: The locomotory activity rhythm of the Arabian spiny mouse, Acomys dimidiatus from the Arabian Peninsula. J. Arid Environ. 2014, 102, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaili, A.N.; Mohammed, O.B.; Bennett, N.C.; Oosthuizen, M.K. A tale of two jirds: The locomotory activity patterns of the King jird (Meriones rex) and Lybian jird (Meriones lybicus) from Saudi Arabia. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 88, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaili, A.N.; Mohammed, O.B.; Bennett, N.C.; Oosthuizen, M.K. Lights out, let's move about: Locomotory activity patterns of Wagner's Gerbil from the desert of Saudi Arabia. Afr. Zool. 2012, 47, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi-Said, M.R.; Al Zein, M.S.; Abu Baker, M.A.; Amr, Z.S. Diet of the desert eagle owl, Bubo ascalaphus, Savigny 1809 in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Pak. J. Zool. 2020, 52, 1169–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ahmary, A.; Al Obaid, A.; Al Ghamdi, A.-R.; Shuraim, F.; Al Jbour, S.; Al Bough, A.; Amr, Z.S. Diet of the Barn Owl, Tyto alba, from As Saqid Island, Farasan Archipelago, Saudi Arabia. Sandgrouse 2023, 45, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Al Ghamdi, A.-R.; Alshammary, T.; Al Gethami, F.; Al Boug, A.; Al Jbour, S.; Amr, Z.S. Diet of Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus, from Ara’r region, northeastern Saudi Arabia. Ornis Hung. 2023, 31, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghamdi, A.-R.; Al Gethami, F.; Abu Baker, M.; Al Atawi, T.; Al Boug, A.; Amr, Z.S. Diet composition of the Pharaoh eagle owl, Bubo ascalaphus, diet across agricultural and natural areas in Saudi Arabia. Brazil. J. Biol. 2023, 83, e276117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. 3rd Edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, 2005, 2142 pp.

- Harrison, D.L.; Bates, P.J.J. The Mammals of Arabia.2nd Edition. Harrison Zoological Museum Publication. 1991, 354 pp.

- Bates, P. Desert Specialists: Arabia’s elegant mice. Arabian Wildlife 1996, 2, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Amr, Z.S.; Abu Baker, M.A.; Qumsiyeh, M.; Eid, E. Systematics, distribution and ecological analysis of rodents in Jordan. Zootaxa 2018, 4397, 1–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingdon, J. Arabian Mammals. A Natural History. Academic Press, London/New York/Tokyo/Sydney. 1990.

- Atallah, S.I. Mammals of the Eastern Mediterranean: their ecology, systematics and zoogeographical relationships. Säugetierkd. Mitt 1978, 26, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khalili, A.D. New records of ectoparasites of small rodents from SW Saudi Arabia. Fauna of Saudi Arabia 1984, 6, 510–512. [Google Scholar]

- Khadhim, A.H.; Wahid, I.N. Reproduction of male Euphrates jerboa Allactaga euphratica Thomas (Rodentia: Dipodidae) from Iraq. Mammalia 1986, 50, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Bates, P. Diet of the Desert Eagle Owl in Harrat al Harrah reserve, northern Saudi Arabia. Ornithological Society of the Middle East Bulletin 1993, 30, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, D.; Nader, I. Terrestrial mammals of the Jubail Marine Wildlife Sanctuary. In: Krupp, F.; Abuzinada, A.H.; Nader, I.A.A. (Edits.). Marine Wildlife Sanctuary for the Arabian Gulf: Environmental research and conservation following the 1991 Gulf War oil spill. 1996, Pp. 421-437.

- Henry, O.; Dubost, G. Breeding periods of Gerbillus cheesmani (Rodentia, Muridae) in Saudi Arabia. Mammalia 2012, 76, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, R.; Wacher, T.; Bruce, T.; Barichievy, C. The status and ecology of the sand cat in the Uruq Bani Ma’arid Protected Area, Empty Quarter of Saudi Arabia. Mammalia 2021, 85, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadim, A.H.; Mustafa, A.M.; Jabir, H.A. Biological notes on jerboas Allactaga euphratica and Jaculus jaculus from Iraq. Acta Theriol. 1979, 24, 24,93–98. [Google Scholar]

- El Bahrawy, AA.; Al Dakhil, MA. Studies on the ectoparasites (fleas and lice) on rodents in Riyadh and its surroundings, Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 1993, 23, 23,723–35. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saleh, A.A. Cytological studies of certain desert mammals of Saudi Arabia 6. First report on chromosome number and karyotype of Acomys dimidiatus. Genetica 1988, 76, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmed, A.M.; Al-Dawood, A.S. Rodents and their ectoparasites in Wadi Hanifah, Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2001, 31, 737–43. [Google Scholar]

- Masseti, M. The mammals of the Farasan archipelago, Saudi Arabia. Turk. J. Zool. 2010, 34, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiry, K.A.; Fetoh, B.E.A. Occurrence of ectoparasitic arthropods associated with rodents in Hail region northern Saudi Arabia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 10120–10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekolnikov, A.A.; Alghamdi, S.; Alagaili, A.N.; Makepeace, B.L. First data on chigger mites (Acariformes: Trombiculidae) of Saudi Arabia, with a description of four new species. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2019, 24, 1937–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.D.; Al-Mohammed, H.I.; Alyousif, M.S.; Said, A.E.; Salim, B.; Abdel-Shafy, S.; Shaapan, R.M. Species diversity and seasonal distribution of hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting mammalian hosts in various districts of Riyadh province. Saudi Arabia. J. Med. Entomol. 2019, 56, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolnik, A.; Borut, A. Temperature and water relations in two species of spiny mice (Acomys). J. Mamm. 1969, 50, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolnik, A. Studies in the comparative biology of Israel’s two species of spiny mice (genus Acomys). Ph. D. dissertation. Hebrew University. Jerusalem. 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Amr, Z.S.; Saliba, E.K. Ecological observations on the Fat Jird, Psammomys obesus dianae, in the Mowaqqar area of Jordan. Dirasat 1986, 13, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Baker, M.; Amr, Z. A morphometric and taxonomic revision of the genus Gerbillus in Jordan with notes on its current distribution. Zool. Abh. (Dresden) 2003, 53, 177–204. [Google Scholar]

- Schenbort, G.; Krasnov, B.; Khokhlova, I. Biology of Wagner’s gerbil, Gerbillus dasyurus (Wagner, 1842) (Rodentia: Gerbillidae) in the Negev Highlands, Israel. Mammalia 1997, 61, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenain, D.M.; Olfermann, E.; Warrington, S. Ecology, diet and behaviour of two fox species in a large, fenced protected area in central Saudi Arabia. J. Arid Environ. 2004, 57, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, S.I. A collection of mammals from El-Jafr, southern Jordan. Säugetierkd Mitt 1967, 32, 307–309. [Google Scholar]

- Schenbort, G.; Krasnov, B.; Khokhlova, I. On the biology of Gerbillus henleyi (Rodentia: Gerbillidae) in the Negev Highlands, Israel. Mammalia 1994, 58, 581–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.M.; Dunstone, N. Environmental determinants of the composition of desert-living rodent communities in the north-east Badia region of Jordan. J. Zool. 2000, 251, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison-Scott, T.C.S. Some Arabian mammals collected by Mr. H. St. J.B. Philby: C.I.E. Novit. Zool. 1939, 41, 181–211. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Dieyeh, M.H. The Ecology of some rodents in Wadi Araba with special reference to Acomys cahirinus. M.Sc. thesis. Jordan University. 216 pp. 1988.

- Qumsiyeh, M.B. Mammals of the Holy Land. Texas Tech University Press. 1996, 389 pp.

- Krasnov, B.R.; Shenbrot, G.I.; Khokhlova, I.S.; Degen, A.A.; Rogovin, K.A. On the biology of Sundevall's jird (Meriones crassus Sundevall, 1842) (Rodentia: Gerbillidae) in the Negev Highlands, Israel. Mammalia 1996, 60, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, S.I. Mammals of the Eastern Mediterranean: their ecology, systematics and zoogeographical relationships. Säugetierkd Mitt 1977, 25, 241–320. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, D.J.; Helmy, I. The contemporary land mammals of Egypt (including Sinai). Fieldiana Zool. 1980, 5, 1–579. [Google Scholar]

- Ellerman, J.R. Key to the rodents of south-west Asia in the British Museum collection. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1948, 118, 765–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S. The vector biology and microbiome of parasitic mites and other ectoparasites of rodents. Ph. D. thesis. University of Liverpool, 2019, 328 pp.

- Al-Saleh, A.A.; Khan, M.A. Cytological studies of certain desert mammals of Saudi Arabia 5. The karyotype of Meriones rex. Genetica 1987, 73, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, T.A.; El Bahrawy, A.F.; El Dakhil, M.A. Ecto- and blood parasites affecting Meriones rex trapped in Najran, Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2001, 31, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Mohammed, H.I. Taxonomical studies of ticks infesting wild rodents from Asir Province in Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2008, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harrison, A.; Robb, G.N.; Alagaili, A.N.; Hastriter, M.W.; Apanaskevich, D.A.; Ueckermann, E.A.; Bennett, N.C. Ectoparasite fauna of rodents collected from two wildlife research centres in Saudi Arabia with discussion on the implications for disease transmission. Acta Trop. 2015, 147, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharoni, B. Die Muriden von Palästina und Syrien. Z. Säugetierkd. 1932, 7, 166–240. [Google Scholar]

- Nader, I.A. A new record of the bushy-tailed jird, Sekeetamys calurus calurus Thomas, 1892 from Saudi Arabia. Mammalia 1974, 38, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shargal, E.; Kronfeld, N.; Dayan, T. On the population ecology of the bushy-tailed jird (Sekeetamys calurus) at En Gedi. Isr. J. Zool. 1998, 44, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Geffen, E.; Hefner, R.; MacDonald, D.W.; Ucko, M. Diet and foraging behavior of Blanford’s foxes, Vulpes cana, in Israel. J. Mamm. 1992, 73, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalili, A.D. Ecology of small rodents in the Asir National Park, Saudi Arabia. Ph. D. thesis, University of Bradford, UK. 1983.

- Doughty, C. M. Travels in Arabia Deserta. Cambridge: University Press, 1888, 674 pp.

- Dickson, H. R.P. The Arab of the Desert. London: George Allen & Unwin. 1949, 664 pp.

- Al-Safadi, M.M.; Nader, I.A. The Indian crested porcupine, Hystrix indica indica Kerr, 1792 in North Yemen with comments on the occurrence of the species in the Arabian Peninsula (Mammalia: Rodentia: Hystricidae). Fauna of Saudi Arabia 1991, 12, 411–415. [Google Scholar]

- Alkon, P.U.; Saltz, D. Influence of season and moonlight on temporal-activity patterns of Indian crested porcupines (Hystrix indica). J. Mamm. 1988, 69, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delany, M.J. The zoogeography of the mammal fauna of southern Arabia. Mamm. Rev. 1989, 19, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, H.J.; Cuttelod, A. (Compilers). The Status and Distribution of Mediterranean Mammals. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN. vii+32pp. 2009.

- Aloufi, A.; Eid, E. Zootherapy: A study from the Northwestern region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2016, 15, 561–569. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sheikhly, O.F.; Haba, M.K.; Barbanera, F.; Csorba, G.; Harrison, D.L. Checklist of the mammals of Iraq (Chordata: Mammalia). Bonn Zool. Bull. 2015, 64, 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Amr, Z.S. The Mammals of Jordan. 2nd edition. Al Rai Press, Amman. 2012.

- AI-Khalili, A.D. New records and a review of the mammalian fauna of the State of Bahrain, Arabian Gulf. J. Arid Environ. 1990, 19, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Baker, M.A.; Buhadi, Y.A.; Alenezi, A.; Amr, Z.S. Mammals of the State of Kuwait, IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Environment Public Authority: Kuwait, Kuwait, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, A.; Madkour, G. New records of some mammals from Qatar: Insectivora, Lagomorpha and Rodentia. Qatar Univ. Sci. Bull. 1984, 4, 4,125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, P.L. Checklist and status of the terrestrial mammals from the United Arab Emirates. Zool. Middle East 2004, 33, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, E.C.; Pardiñas, U.F.J. First record of the bushy-tailed jird, Sekeetamys calurus (Thomas, 1892) (Rodentia: Muridae) in Oman. Mammalia 2016, 80, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensoor, M. The mammals of Yemen (Chordata: Mammalia). Preprints.org 2023, 2023010181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Present study | Delany [76] |

| Eliomys melanurus | Afr-Pal | Afr-Pal-Or |

| Jaculus loftusi | Pal | Afr-Pal |

| Scarturus euphratica | Pal | Not listed |

| Gerbillus cheesmani | Pal | Pal |

| Gerbillus dasyurus | Pal | Pal |

| Gerbillus henleyi | Afr-Pal | Afr |

| Gerbillus nanus | Afr-Pal-Or | Afr-Pal-Or |

| Gerbillus poecilops | Endemic | Endemic |

| Meriones crassus | Afr-Pal-Or | Afr-Pal |

| Meriones libycus | Afr-Pal-Or | Afr-Pal |

| Meriones rex | Endemic | Endemic |

| Psammomys obesus | Afr-Pal | Not listed |

| Sekeetamys calurus | Afr-Pal | Not listed |

| Acomys dimidiatus | Afr-Pal | Afr-Pal |

| Acomys russatus | Afr-Pal | Afr-Pal |

| Mus musculus | Cosmopolitan | Introduced |

| Myomyscus yemeni | Endemic | Endemic |

| Rattus norvegicus | Cosmopolitan | Introduced |

| Rattus rattus | Cosmopolitan | Introduced |

| Hystrix indica | Pal-Or | Pal-Or |

| Species | IUCN global assessment | IUCN Mediterranean assessment [77] | IUCN national assessment |

| Eliomys melanurus | LC | LC | LC |

| Jaculus loftusi | LC | LC* | LC |

| Scarturus euphratica | LC | NT | EN |

| Gerbillus cheesmani | LC | LC | LC |

| Gerbillus dasyurus | LC | LC | LC |

| Gerbillus henleyi | LC | LC | DD |

| Gerbillus nanus | LC | LC | LC |

| Gerbillus poecilops | LC | NA | DD |

| Meriones crassus | LC | LC | LC |

| Meriones libycus | LC | LC | LC |

| Meriones rex | LC | NA | LC |

| Psammomys obesus | LC | LC | LC |

| Sekeetamys calurus | LC | LC | DD |

| Acomys dimidiatus | LC | LC | LC |

| Acomys russatus | LC | LC | LC |

| Mus musculus | LC | LC | LC |

| Myomyscus yemeni | DD | NA | LC |

| Rattus norvegicus | LC | LC | LC |

| Rattus rattus | LC | LC | LC |

| Hystrix indica | LC | LC | NT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).