Submitted:

04 May 2024

Posted:

06 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

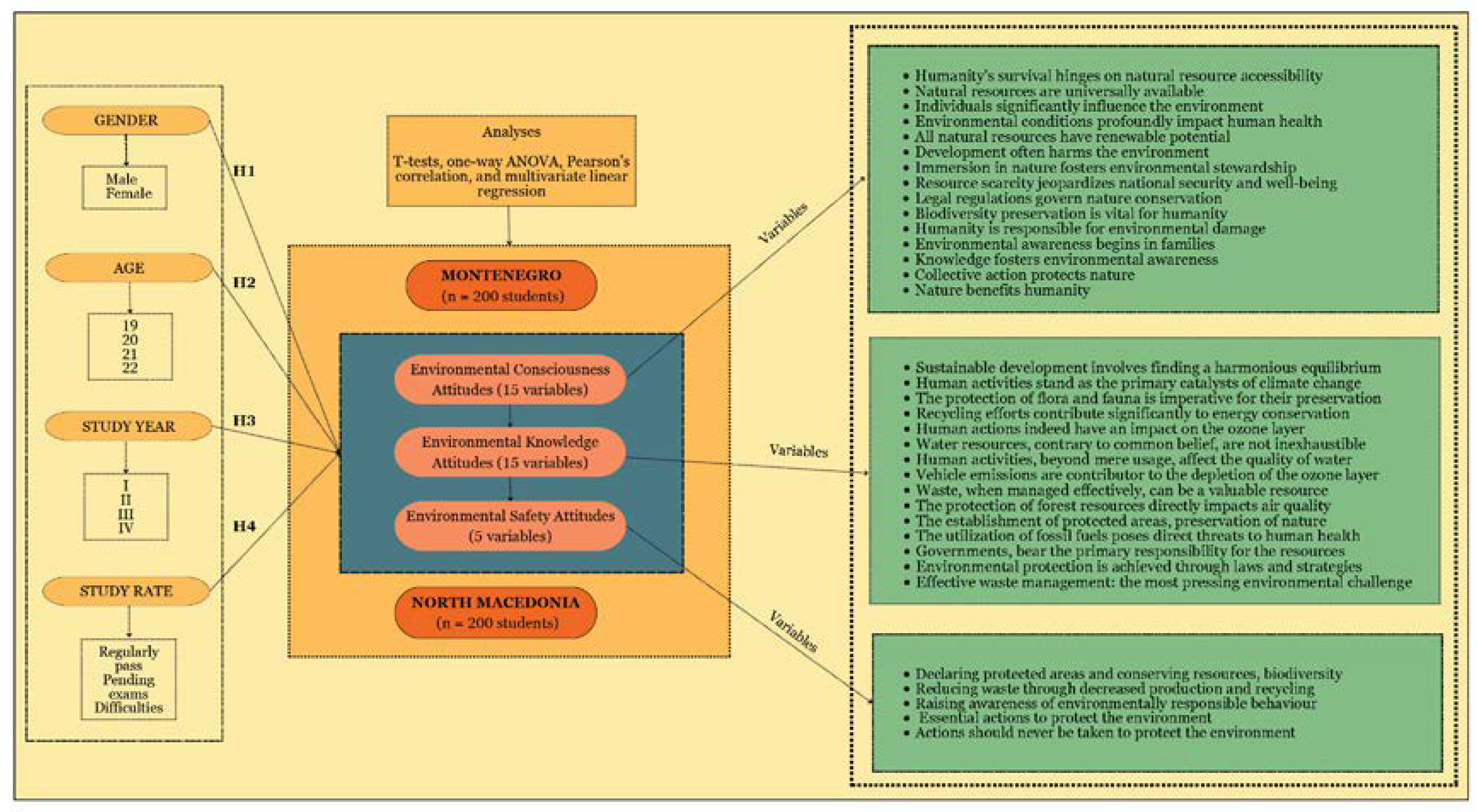

2. Methods

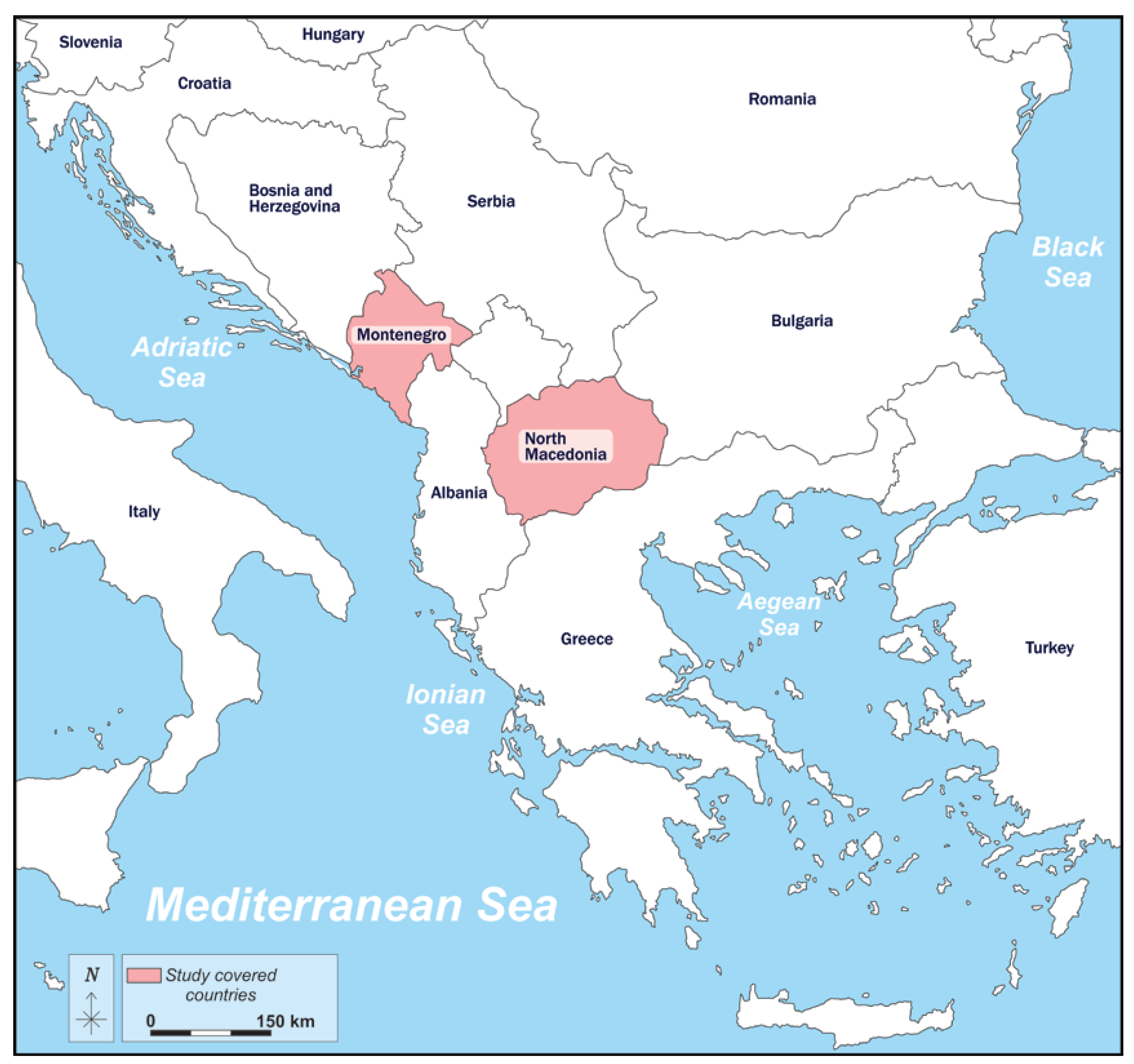

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Socio-Economic and Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

2.3. Questionnaire Design for Surveys and Focus Group Interviews:

2.4. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. The Predictors of Environmental Awareness, Safety and Environmental Knowledge

3.2. A Comparative Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Students' Environmental Awareness, Knowledge and Safety Attitudes in Montenegro and North Macedonia

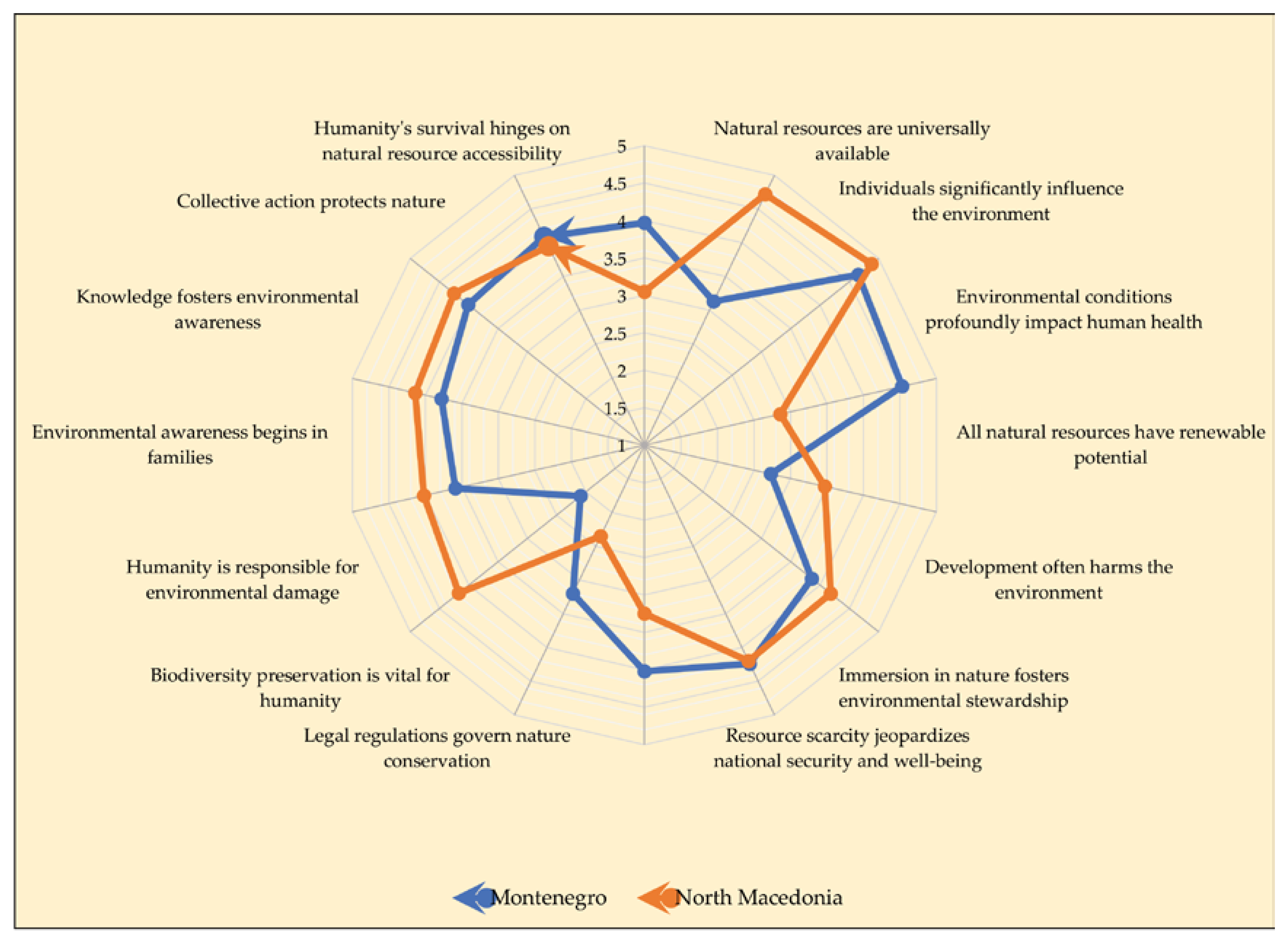

3.2.1. Environmental Awareness Attitudes

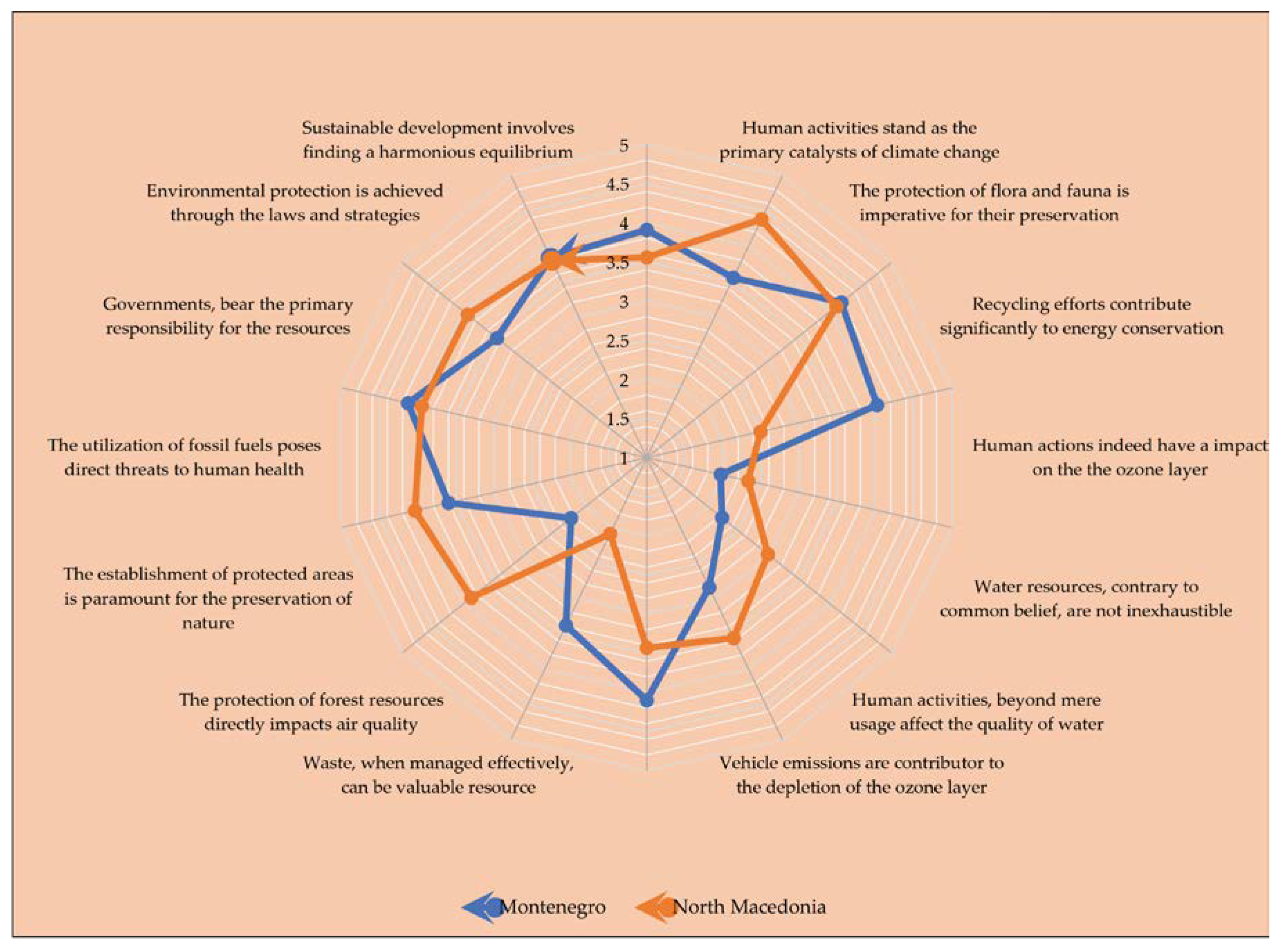

3.2.2. Environmental Knowledge Attitudes

3.2.3. Environmental Safety Attitudes

3.3. Influences of Demographic and Socioeconomic Factors on the Environmental Awareness and Perception of Knowledge, and Safety

3.3.1. Influences on the Environmental Awareness and Safety Attitudes

3.3.2. Influences on Environmental Knowledge Attitudes

3.4. Additional Findings from the Focus Group Interview in Montenegro

3.4.1. Assessing Environmental Perceptions in Montenegro: A Comparative Analysis by Region and Student Characteristics

3.4.2. The quintessential Environmental Challenges in Montenegro

3.4.3. Institutions in Montenegro Engaged in Environmental Protection and Methods of Protecting Natural Resources in Montenegro

3.4.4. Enhancing Environmental Awareness: Analyzing the Focus Group's Insights

3.4.5. Waste Management Solutions in Montenegro

3.4.6. Identifying Sustainable Practices for Utilizing Natural Resources

3.4.7. Climate Change Threat and Adaptation Strategies for Montenegro

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- By declaring protected areas and conserving resources and biodiversity. (1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5)

- By reducing waste through decreased production and recycling. (1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5)

- By raising and/or strengthening awareness of environmentally responsible behavior (living in harmony with nature, sustainable resource use, and/or non-pollution of the environment and resources). (1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5)

- According to your opinion, what three actions are essential to protect the environment?______________________________________________________________________________

- According to your opinion, what three actions should never be taken to protect the environment? ______________________________________________________________________________

- Is there anything you expected us to ask but didn't find in the questionnaire? (What would you ask if you were conducting this research?) ______________________________________________

- Gender: Please indicate your gender.

- Age: State your age.

- Highest Education Attained: Specify the highest level of education you have completed.

- Region of Origin and Residence until Commencing College: Identify the region where you were born and resided until beginning college.

- Parental Education: Provide details on your parents' educational background.

- Place of Residence: Describe your current residential setting.

- Academic Year at the Faculty: Indicate your current academic year.

- Residence during Academic Pursuits: Specify your living arrangements while attending university.

- Assessment of Environmental Conditions in Montenegro: Express your viewpoint regarding the environmental status in Montenegro.

- Primary Environmental Concerns in Montenegro: Enumerate the five most pressing ecological issues necessitating resolution in Montenegro.

- Environmental Institutions in Montenegro: Identify and rank institutions in Montenegro engaged in environmental protection.

- Strategies for Safeguarding Natural Resources in Montenegro: Propose methodologies for safeguarding natural resources within Montenegro.

- National Park Analysis in Montenegro: Quantify the number of national parks and evaluate their efficacy in conserving designated natural resources.

- Waste Management Solutions in Montenegro: Devise strategies for mitigating or resolving waste-related challenges.

- Sustainable Utilization of Montenegro's Natural Endowments: Suggest sustainable approaches for harnessing natural resources.

- Climate Change Perception and Adaptation Strategies in Montenegro: Assess the perceived threat of climate change and outline strategies for resistance or adaptation.

References

- Schmidt, M.; Onyango, V.; Palekhov, D. Environmental Challenges and Management of Natural Resources. Implementing Environmental and Resource Management: Springer; 2011, 1-4.

- Spruyt, B.; De Keere, K.; Keppens, G.; Roggemans, L.; Van Droogenbroeck, F. What is it worth? An empirical investigation into attitudes towards education amongst youngsters following secondary education in Flanders. British Journal of Sociology of Education 2016, 37, 586–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrón, N.G.; Gruber, S.; Huffman, G. Student engagement and environmental awareness: Gen Z and ecocomposition. Environmental Humanities 2022, 14, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Z.; Umar, S.; Bashir, S.; Kuchey, Z.F.; ud din Bhat, M. A study of environmental awareness, attitude and participation among secondary school students of district Kulgam, J&K., India. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research 2022, 11, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, T.O. Assessment of secondary school students’ awareness of climate change. International Journal of Scientific Research and Education 2014, 2, 2713–2723. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, T.; Gericke, N.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Olsson, D.; Chang, T.-C. A cross-cultural comparative study of sustainability awareness between students in Taiwan and Sweden. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2020, 22, 6287–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, B.G. Assessing impacts of locally designed environmental education projects on students’ environmental attitudes, awareness, and intention to act. Environmental Education Research 2016, 22, 480–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapport, D.J. Sustainability science: an eco-health perspective. Sustainability Science 2007, 2, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, B. Sustainability, human welfare, and ecosystem health. Environmental values 1992, 1, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, M. Environmental Awareness by curricular and Co-curricular activities among student teachers. Sparkling International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research Studies 2019, 2, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bhola, N. A study of environmental awareness among secondary school students. EXCEL International Journal of Multidisciplinary Management Studies 2013, 3, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Tanasić, J.; Ocal, A.; Kešetović, Ž.; Nikolić, N.; Dragašević, A. Capacity Development of Local Self-Governments for Disaster Risk Management. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 10406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, V.; Ursi, S.; Lima, E.; Katon, G. Environmental perception: Notes on transdisciplinary approach. Scientific Journal of Biology & Life Sciences 2020, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Berrios, R.; Totterdell, P.; Kellett, S. Individual differences in mixed emotions moderate the negative consequences of goal conflict on life purpose. Personality and Individual Differences 2017, 110, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Haggar, S.M. Sustainability of municipal solid waste management. Sustain Ind Des Waste Manag 2007, 149–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kassinis, G.; Panayiotou, A.; Dimou, A.; Katsifaraki, G. Gender and environmental sustainability: A longitudinal analysis. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2016, 23, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathevet, R.; Bousquet, F.; Raymond, C.M. The concept of stewardship in sustainability science and conservation biology. Biological Conservation 2018, 217, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asan, I.; Mile, S.; Ibrahim, J. Attitudes of Macedonian high school students towards the environment. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2014, 159, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković V, Milašinović, Srđan, Lazić, Željko. Examination of citizens' attitudes towards providing support to vulnerable people and volunteering during natural disasters. 2017.

- Srbinovski, M.S. Environmental attitudes of Macedonian school students in the period 1995-2016. Inovacije u nastavi-časopis za savremenu nastavu 2019, 32, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.A.; Thompson, C.J.; Hauser, C.; et al. Resource allocation for efficient environmental management. Ecology Letters 2010, 13, 1280–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltseva, S.M.; Balashova, E.S.; Bystrova, N.V.; Stroganov, D.A. Ecological Safety in the Ecological Awareness of Pedagogical University Students. Siberian Journal of Life Sciences and Agriculture 2021, 13, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, V.I.; Mdivani, M.O.; Sh, R.K.; Lidskaya, E.V. The development of the questionnaire for investigation of ecological awareness of townspeople in Russia. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2013, 86, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oğuz, D.; Çakci, I.; Kavas, S. Environmental awareness of university students in Ankara, Turkey. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2010, 5, 2629–2636. [Google Scholar]

- Rajovic, G.; Bulatovic, J. State of environmental awareness in northeastern Montenegro: a review. International Letters of Natural Sciences 2015. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Bansal, M. Environmental awareness, its antecedents and behavioural outcomes. Journal of Indian Business Research 2013, 5, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherdymova, E.I.; Afanasjeva, S.A.; Parkhomenko, A.G.; et al. Student ecological awareness as determining component of ecological-oriented activity. EurAsian Journal of BioSciences 2018, 12, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Shimoda, T.A. Responsibility as a predictor of ecological behaviour. Journal of environmental psychology 1999, 19, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.; de Loë, R.C. Conceptualizations of local knowledge in collaborative environmental governance. Geoforum 2012, 43, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.U.; Chapin Iii, F.S.; Ewel, J.J.; et al. Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge. Ecological monographs 2005, 75, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, T.P.; Habeck, J.O. When'the environment'comes to visit: Local environmental knowledge in the far north of Russia. Environmental Values 2004, 13, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulözü, N. Youths’ perception and knowledge towards environmental problems in a developing country: in the case of Atatürk University, Turkey. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 12482–12490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.; Qian, Q.; Bao, L. Environment Knowledge, Law-Abiding Awareness and Risk Perception Influencing Environmental Behavior. 2020, EDP Sciences. p. 02032.

- Stevanin, S.; Bressan, V.; Bulfone, G.; Zanini, A.; Dante, A.; Palese, A. Knowledge and competence with patient safety as perceived by nursing students: The findings of a cross-sectional study. Nurse education today 2015, 35, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernández-Sáinz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behaviour: comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 61, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderhan-Opel, J.; Bogner, F.X. The relation between knowledge acquisition and environmental values within the scope of a biodiversity learning module. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.A. Environmental sustainability awareness in selected countries. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2020, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Karpudewan, M.; Mohd Ali Khan, N.S. Experiential-based climate change education: Fostering students' knowledge and motivation towards the environment. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 2017, 26, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.M.; Akhtar, R.; Afroz, R.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Kari, F.B. Pro-environmental behavior and public understanding of climate change. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2015, 20, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, T.; Hasan, M.K.; Sony, M.M.A.A.M. Climate change, conflict, and prosocial behavior in Southwestern Bangladesh: implications for environmental justice. Environment, climate, and social justice: perspectives and practices from the Global South: Springer; 2022, 349–369.

- Frankl, A.; Lenaerts, T.; Radusinović, S.; Spalevic, V.; Nyssen, J. The regional geomorphology of Montenegro mapped using Land Surface Parameters. Zeitschrift fur Geomorphologie 2016, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurović, P.; Djurović, M. Physical geographic characteristics and sustainable development of the mountain area in Montenegro. Sustainable Development in Mountain Regions: Southeastern Europe 2016, 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Tošić, B.; Živanović, Z. Comparative analysis of spatial planning systems and policies: Case study of Montenegro, Republic of North Macedonia and Republic of Serbia. Zbornik radova-Geografski fakultet Univerziteta u Beogradu 2019, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gecevska, V. Report on ICT in Education in the Republic of North Macedonia. Comparative Analysis of ICT in Education Between China and Central and Eastern European Countries 2020, 261–283. [Google Scholar]

- Srbinovski, M. Macedonian students’ ecological knowledge and level of information about the environment. Nastava i vaspitanje 2019, 68, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalka, R. The psychological constitution of environmental awareness in primary school students. Natura;2016.

- Sarancha, I.; Fushtei, O. Conscious perception of environmental threats: the role of environmental psychology in the formation of environmental awareness. Personality and environmental issues 2023, 2, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Sheng, J. How can environmental knowledge transfer into pro-environmental behavior among Chinese individuals? Environmental pollution perception matters. Journal of Public Health 2018, 26, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich, M.I.; Zaks, M.A.; Varona, P. Sequential dynamics of complex networks in mind: Awareness and creativity. Physics Reports 2020, 883, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärling, T.; Golledge, R.G. Environmental perception and cognition. Advance in Environment, Behavior, and Design: Volume 2, Springer; 1989, 203–236.

- Shumilina, A.; Anсiferova, N. Mechanisms for developing and shaping environmental awareness in the globalised world. 2023, EDP Sciences. p. 06023.

- Liobikienė, G.; Poškus, M.S. The importance of environmental knowledge for private and public sphere pro-environmental behavior: modifying the value-belief-norm theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental education research 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. International journal of psychology 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corburn, J. Bringing local knowledge into environmental decision making: Improving urban planning for communities at risk. Journal of planning education and research 2003, 22, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Geiger, M.; Wilhelm, O. Environment-specific vs. general knowledge and their role in pro-environmental behavior. Frontiers in psychology 2019, 10, 405705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, A.; Addoah, T. Does environmental knowledge drive pro-environmental behaviour in developing countries? Evidence from households in Ghana. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2021, 23, 2719–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimovska, M.; Gjorgjev, D.; Tozija, F. Are schools in Macedonia ready to achieve children‘s environmental and health policy priority goals? Injury prevention 2012, 18, A105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srbinovski, M.; Stanišić, J. Environmental worldviews of Serbian and Macedonian school students. Australian Journal of Environmental Education 2020, 36, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boca, G.D.; Saraçlı, S. Environmental education and student’s perception, for sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevencan, F.; Yavuz, C.I.; Acar Vaizoğlu, S. Environmental awareness of students from secondary and high schools in Bodrum, Turkey. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24, 3045–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntanos, S.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Arabatzis, G.; Palios, V.; Chalikias, M. Environmental behavior of secondary education students: A case study at central Greece. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srbinovski, M.; Ismaili, M.; Abazi, A. The trend of the high school students’ level of environmental knowledge in the republic of Macedonia. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2011, 15, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.P.M. Environmental awareness among students in senior secondary schools: The case of Hong Kong. Environmental Education Research 1998, 4, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaili, M.; Srbinovski, M.; Sapuric, Z. Students’ conative component about the environment in the Republic of Macedonia. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2014, 116, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosheva, S.; Kjosevska, E.; Stefanovska, V.V. Assessment of the physical environment situation in primary schools in the Republic of North Macedonia. Archives of Public Health 2020, 12, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, A.; Radziemska, M.; Fronczyk, J. Determination of risk perceptions of university students and evaluating their environmental awareness in Poland. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi Fen Edebiyat Fakültesi Fen Bilimleri Dergisi 2016, 37, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaizoglu, S.; Altintas, H.; Temel, F. Evaluation of the environmental awareness of the students in a medical faculty in Ankara. 2005.

- Srbinovski, M.; Erdogan, M.; Ismaili, M. Environmental literacy in the science education curriculum in Macedonia and Turkey. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2010, 2, 4528–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, B.; Boldero, J.; Holdsworth, R. Gender patterns in environmental awareness among adolescents. The Australian and New Zealand journal of sociology 1996, 32, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernández-Sainz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Does gender make a difference in pro-environmental behavior? The case of the Basque Country University students. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 176, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N. The effect of gender on students' sustainability awareness: A nationwide Swedish study. The Journal of Environmental Education 2017, 48, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumara, K.; Sangeetha Mane, R.; Diksha, J.; Nagara, O. Effect of gender on environmental awareness of post-graduate students. British Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science 2015, 8, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riechard, D.E.; Peterson, S.J. Perception of environmental risk related to gender, community socioeconomic setting, age, and locus of control. The Journal of environmental education 1998, 30, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, W.L.; Hara, N. Gender differences in environmental concern among college students. Sex Roles 1994, 31, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.D.; Hafeez, M.; Kim, J.-Y. Workers’ age and the impact of psychological factors on the perception of safety at construction sites. Sustainability 2017, 9, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Díaz-Reviriego, I.; Luz, A.C.; Cabeza, M.; Pyhälä, A.; Reyes-García, V. Rapid ecosystem change challenges the adaptive capacity of local environmental knowledge. Global Environmental Change 2015, 31, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garai-Fodor, M. The Impact of the Coronavirus on Competence from a Generation-Specific Perspective. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica 2022, 19, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Aghamolaei, R.; Myint, P.K. How do older women perceive their safety in Iranian urban outdoor environments? Ageing International 2020, 45, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, H.; You, S. Analysis of the impact of environmental perception on the health status of middle-aged and older adults: a study based on CFPS 2020 data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venables, D.; Pidgeon, N.F.; Parkhill, K.A.; Henwood, K.L.; Simmons, P. Living with nuclear power: Sense of place, proximity, and risk perceptions in local host communities. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2012, 32, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. COVID-19 Place confinement, pro-social, pro-environmental behaviors, and residents’ wellbeing: A new conceptual framework. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11, 566333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattino, S.; De Piccoli, N.; Fassio, O.; Rollero, C. Quality of life and sense of community. A study on health and place of residence. Journal of Community Psychology 2013, 41, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.J.; Malilay, J.N.; Parkinson, A.J. Climate change: the importance of place. American journal of preventive medicine 2008, 35, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-S. A Study on the Relationship between Psychological Responses and Safety Accidents to Safe Housing Environments. Journal of the Korean Society of Hazard Mitigation 2018, 18, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, F.; Turkyilmaz, A.; Myrzagali, A.; Kerimray, A.; Bell, P. An Empirical Model for Assessing the Impact of Air Quality on Urban Residents’ Loyalty to Place of Residence. Environment and Urbanization ASIA 2021, 12, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinson, T.; Morgan, K. Living in extended-stay hotels: Older residents’ perceptions of satisfying and stressful environmental conditions. Journal of Housing for the Elderly 2014, 28, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Burgui-Burgui, M.; Da Silva, E.V.; Hussein, K.; Alkaabi, K. Factors affecting environmental sustainability habits of university students: Intercomparison analysis in three countries (Spain, Brazil and UAE). Journal of cleaner production 2018, 198, 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A. Heterogeneity in the preferences and pro-environmental behavior of college students: The effects of years on campus, demographics, and external factors. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 112, 3451–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChano, L.M. A multi-country examination of the relationship between environmental knowledge and attitudes. International Research in Geographical & Environmental Education 2006, 15, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Grozdanić, G.; Cvetković, V.M.; Lukić, T.; Ivanov, A. Sustainable Earthquake Preparedness: A Cross-Cultural Comparative Analysis in Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumurdzanov, N.; Serafimovski, T.; Burchfiel, B.C. Cenozoic tectonics of Macedonia and its relation to the South Balkan extensional regime. Geosphere 2005, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Gland, Switzerland IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK; 2012.

- Levchev, V.; Taylor, H. Black book of the endangered species Paperback: Word Works Books; 1999.

- Rönnlund, M. Student participation in activities with influential outcomes: Issues of gender, individuality and collective thinking in Swedish secondary schools. European Educational Research Journal 2010, 9, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselinovska, S.S.; Osogovska, T.L. Engagement of students in environmental activities in school. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2012, 46, 5015–5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, N.; Tully, E.C.; Garcia, S.E.; South, S.; Iacono, W.G.; McGue, M. Genetic and environmental influences on affiliation with deviant peers during adolescence and early adulthood. Developmental psychology 2014, 50, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasilnikova, E.V.; Kuznecova, S.N. On the formation of environmental awareness among students of an agricultural university. 2021, IOP Publishing. p. 042006.

- Pitts, R.E.; Canty, A.L.; Tsalikis, J. Exploring the impact of personal values on socially oriented communications. Psychology & Marketing 1985, 2, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Meggers, B.J. Environmental limitation on the development of culture. American anthropologist 1954, 56, 801–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, A.; Bhatti, W.A.; Glowik, M. The influence of cultural values on pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 268, 122305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonell, C.; Wells, H.; Harden, A.; et al. The effects on student health of interventions modifying the school environment: systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013, 67, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, S.; Rusu, D.; Dragomir, M.; Popescu, D.; Nedelcu, Ș. Competitive development tools in identifying efficient educational interventions for improving pro-environmental and recycling behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berryhill, J.C.; Prinz, R.J. Environmental interventions to enhance student adjustment: Implications for prevention. Prevention Science 2003, 4, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.; Shallcross, T. Social change and education for sustainable living. Curriculum Studies 1998, 6, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyes, E.; Stanisstreet, M. Environmental education for behaviour change: Which actions should be targeted? International Journal of Science Education 2012, 34, 1591–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Anguita, P.M.; Alonso, E.; Martin, M.A. Environmental economic, political and ethical integration in a common decision-making framework. Journal of environmental management 2008, 88, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R. Social goals and the valuation of ecosystem services. Ecosystems 2000, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, S.T. Contextual influences on environmental concerns cross-nationally: A multilevel investigation. Social science research 2012, 41, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, P.J.; Balisky, A.C.; Coward, L.P.; Kneeshaw, D.D.; Cumming, S.G. The value of managing for biodiversity. The forestry chronicle 1992, 68, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchtele, R.; Lapka, M. The usual discourse of sustainable development and its impact on students of economics: a case from Czech higher education context. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2022, 23, 1001–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological conservation 2020, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovski, V. Policy Processes in the Institutionalisation of Private Forestry in the Republic of North Macedonia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öllerer, K. Environmental education–the bumpy road from childhood foraging to literacy and active responsibility. Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences 2015, 12, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.; Maureaud, C.; Wilcox, C.; Hardesty, B.D. How successful are waste abatement campaigns and government policies at reducing plastic waste into the marine environment? Marine Policy 2018, 96, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seadon, J.K. Sustainable waste management systems. Journal of cleaner production 2010, 18, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansel, B. From electronic consumer products to e-wastes: Global outlook, waste quantities, recycling challenges. Environment international 2017, 98, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloodworth, A. Educational (de) segregation in North Macedonia: The intersection of policies, schools, and individuals. European Educational Research Journal 2020, 19, 310–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M.B.; Rudman, A.N.; Greene, L.K.; Razafindrainibe, F.; Andrianandrasana, L.; Welch, C. Back to basics: Gaps in baseline data call for revisiting an environmental education program in the SAVA region, Madagascar. PloS one 2020, 15, e0231822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M. Family and school influences on cognitive development. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 1985, 26, 683–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. Journal of cleaner production 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvan, O.D. The legal environmental risk analysis (LERA) sample of mining and the environment in Turkish legislation. Resources Policy 2013, 38, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koebel, J.T. Facilitating university compliance using regulatory policy incentives. JC & UL 2018, 44, 160. [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Gerro, T.; Greenspan, I.; Handy, F.; Vered, Y. Environmental behavior in three countries: The role of intergenerational transmission and domains of socialization. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2020, 71, 101343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Ahmadi, S.; Karimi, H. The role of online social networks in university students’ environmentally responsible behavior. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2022, 23, 1045–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, J.; Pedretti, E. Educators’ perceptions of bringing students to environmental awareness through engaging outdoor experiences. Environmental Education Research 2016, 22, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, R.; Voulvoulis, N. The role of public communication in decision making for waste management infrastructure. Journal of environmental management 2017, 203, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.H. Effects of deliberate practice on blended learning sustainability: A community of inquiry perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Roder, G.; Öcal, A.; Tarolli, P.; Dragićević, S. The Role of Gender in Preparedness and Response Behaviors towards Flood Risk in Serbia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetković, V.; Nikolić, N.; Nenadić, R.U.; Ocal, A.; Zečević, M. Preparedness and Preventive Behaviors for a Pandemic Disaster Caused by COVID-19 in Serbia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocal, A.; Cvetković, V.; Baytiyeh, H.; Tedim, F.; Zečević, M. Public reactions to the disaster COVID-19, A comparative study in Italy, Lebanon, Portugal, and Serbia. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk 2020, 11, 1864–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adem, Ö.J.I.J.o.D.R.M. Natural Disasters in Turkey: Social and Economic Perspective. 2019, 1, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Aktar, M.A.; Shohani, K.; Hasan, M.N.; Hasan, M.K. Flood Vulnerability Assessment by Flood Vulnerability Index (FVI) Method: A Study on Sirajganj Sadar Upazila. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2021, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-ramlawi, A.; El-Mougher, M.; Al-Agha, M. The Role of Al-Shifa Medical Complex Administration in Evacuation & Sheltering Planning. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2020, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrina, M.; Budiarti, D.; Yu, Z.; Pasha, F.; Shaw, R. Governmental Incentivization for SMEs’ Engagement in Disaster Resilience in Southeast Asia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2019, 1, 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baruh, S.; Dey, C.; Dutta, N.P.M.K. Dima Hasao, Assam (India) landslides’ 2022, A lesson learnt. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2023, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carla, S.R.G. School-community collaboration: disaster preparedness towards building resilient communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2019, 1, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chakma, U.K.; Hossain, A.; Islam, K.; Hasnat, G.T. Water crisis and adaptation strategies by tribal community: A case study in Baghaichari Upazila of Rangamati District in Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V. Risk Perception of Building Fires in Belgrade. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2019, 1, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mougher, M.M.; Sharekh, S.A.M.A.; Ali, M.R.F.A.; Zuhud, E.A.A.M. Risk Management of Gas Stations that Urban Expansion Crept into in the Gaza Strip. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2023, 5, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Dragićević, S.; Petrović, M.; Mijaković, S.; Jakovljević, V.; Gačić, J. Knowledge and perception of secondary school students in Belgrade about earthquakes as natural disasters. Polish journal of environmental studies 2015, 24, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Nikolić, N.; Ocal, A.; Martinović, J.; Dragašević, A. A Predictive Model of Pandemic Disaster Fear Caused by Coronavirus (COVID-19): Implications for Decision-Makers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetković, V.; Stanišić, J. Relationship between demographic and environmental factors with knowledge of secondary school students on natural disasters. , SASA. Journal of the Geographical Institute Jovan Cvijic 2015, 65, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, Vladimir M., Adem Öcal, Yuliya Lyamzina, Eric K. Noji, Neda Nikolić, and Goran Milošević. Nuclear Power Risk Perception in Serbia: Fear of Exposure to Radiation vs. Social Benefits" Energies 14, no. 9, 2464. [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, N.C.V.; Zečević, M. Human Resource Management in Environmental Protection in Serbia. Bulletin of the Serbian Geographical Society 2020, 100, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueira, J.R.C. A mathematical view of biological complexity. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation 2009, 14, 2581–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Role of Indigenous people in biodiversity conservation and utilization in Jinping divide Nature Reserve: An ethnoecological perpective. Chinese Journal of Ecology 2003, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Brymer, E.; Davids, K. Ecological dynamics as a theoretical framework for development of sustainable behaviours towards the environment. Environmental Education Research 2013, 19, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shernoff, D.J.; Kelly, S.; Tonks, S.M.; et al. Student engagement as a function of environmental complexity in high school classrooms. Learning and Instruction 2016, 43, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, D.; Assaraf, O.B.Z.; Shaharabani, D. Influence of a non-formal environmental education programme on junior-high-school students’ environmental literacy. International Journal of Science Education 2013, 35, 515–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, A.I.V.; Sudar, S. Recognition and perception of risks and environmental hazards on the part of the student population in the Republic of Macedonia. 2015, University “St. Kliment Ohridski” - Bitola Faculty of Security.

- Cvetković, VM. , Dragašević, A, Protić, D, Janković, B, Nikolić, N, Milošević, P. Fire Safety Behavior Model for Residential Buildings: Implications for Disaster Risk Reduction. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2022, 75, 102981. [Google Scholar]

- Parham-Mocello, J.; Smith, M. Environmentally Responsible Engineering in a New First-Year Engineering Experience. 2022, IEEE. p. 1-8.

- Irby, D.M.; Wilkerson, L. Educational innovations in academic medicine and environmental trends. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2003, 18, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | Montenegro |

North Macedonia |

Total | |||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | Male Female |

110 90 |

55.0 45.0 |

95 105 |

47.5 52.5 |

205 195 |

52.5 47.5 |

| Age | 19 20 21 22 |

40 50 56 54 |

20.0 25.0 28.0 27.0 |

35 55 60 50 |

17.5 27.5 30.0 25.0 |

75 105 116 104 |

18.75 26.25 29.0 26.0 |

| Place of residence | City centre Suburban area Village |

66 80 54 |

33.0 40.0 27.0 |

70 67 63 |

25.0 33.5 31.5 |

136 147 117 |

33.75 36.75 29.5 |

| Study year | I II III IV |

45 46 51 58 |

22.50 23.0 25.50 29.0 |

65 56 57 22 |

32.5 28.0 28.5 11.0 |

110 102 108 80 |

27.5 25.5 27.0 20.0 |

| Study rate | Regularly pass exams Pending exams Difficulties with exams |

80 30 90 |

40.0 15.0 45.0 |

90 50 60 |

45.0 25.0 30.0 |

170 80 150 |

42.5 20.0 37.5 |

|

Predictor Variable |

Environmental awareness attitudes |

Knowledge of environmental protection attitudes |

Contribute to environmental safety |

||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Gender | 0.067 | 0.048 | 0.074 | ̶ 0.058 | 0.051 | ̶ 0.060 | 0.245 | 0.082 | 0.158 |

| Age | ̶ 0.135 | 0.056 | ̶ 0.146 | 0.007 | 0.059 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.095 | 0.013 |

| Place of residence | 0.035 | 0.073 | 0.024 | 0.034 | 0.077 | 0.022 | ̶ 0.104 | 0.125 | ̶ 0.042 |

| Studu year | 0.125 | 0.061 | 0.128 | ̶ 0.135 | 0.065 | ̶ 0.131 | 0.144 | 0.105 | 0.086 |

| Study rate | 0.028 | 0.047 | 0.031 | ̶ 0.042 | 0.049 | ̶ 0.044 | ̶ 0.005 | 0.080 | ̶ 0.003 |

| 0.019 (0.006) | 0.020 (0.008) | 0.027 (0.015) | |||||||

| Environmental awareness variables | Montenegro | North Macedonia | Total | |||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Humanity's survival hinges on natural resource accessibility | 3.97 | 0.99 | 3.05 | 1.23 | 3.51 | 1.06 |

| Natural resources are universally available | 3.13 | 1.04 | 4.72 | 0.59 | 3.92 | 1.08 |

| Individuals significantly influence the environment | 4.65 | 0.53 | 4.88 | 0.53 | 4.77 | 0.79 |

| Environmental conditions profoundly impact human health | 4.53 | 0.79 | 2.86 | 1.25 | 3.70 | 1.02 |

| All natural resources have renewable potential | 2.73 | 1.13 | 3.47 | 1.01 | 3.10 | 1.07 |

| Development often harms the environment | 3.86 | 0.98 | 4.18 | 1.19 | 4.02 | 1.09 |

| Immersion in nature fosters environmental stewardship | 4.24 | 0.77 | 4.20 | 0.99 | 4.22 | 0.88 |

| Resource scarcity jeopardizes national security and well-being | 4.02 | 0.87 | 3.25 | 1.13 | 3.64 | 0.92 |

| Legal regulations govern nature conservation | 3.20 | 1.18 | 2.35 | 1.03 | 2.78 | 0.12 |

| Biodiversity preservation is vital for humanity | 2.09 | 0.90 | 4.17 | 0.98 | 3.13 | 0.87 |

| Humanity is responsible for environmental damage | 3.59 | 1.19 | 4.02 | 1.13 | 3.80 | 1.16 |

| Environmental awareness begins in families | 3.78 | 1.13 | 4.14 | 1.00 | 3.96 | 0.99 |

| Knowledge fosters environmental awareness | 4.01 | 0.93 | 4.25 | 0.93 | 4.13 | 0.95 |

| Collective action protects nature | 4.09 | 0.92 | 3.95 | 1.24 | 4.02 | 1.16 |

| Nature benefits humanity | 3.65 | 1.23 | 3.61 | 1.01 | 3.63 | 1.10 |

| Environmental knowledge variables | Montenegro | North Macedonia |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Sustainable development involves finding a harmonious equilibrium | 3.91 | 0.66 | 3.56 | 1.30 | 3.75 | 0.90 |

| Human activities stand as the primary catalysts of climate change | 3.55 | 1.09 | 4.38 | 0.95 | 3.96 | 1.12 |

| The protection of flora and fauna is imperative for their preservation | 4.18 | 0.84 | 4.10 | 1.21 | 4.14 | 1.08 |

| Recycling efforts contribute significantly to energy conservation | 4.02 | 0.89 | 2.49 | 1.45 | 3.26 | 1.17 |

| Human actions indeed have an impact on the ozone layer | 1.97 | 0.89 | 2.33 | 1.24 | 2.15 | 1.06 |

| Water resources, contrary to common belief, are not inexhaustible | 2.23 | 1.06 | 2.98 | 1.29 | 2.61 | 1.18 |

| Human activities, beyond mere usage, affect the quality of water | 2.84 | 1.06 | 3.56 | 1.13 | 3.20 | 1.10 |

| Vehicle emissions are contributor to the depletion of the ozone layer | 4.10 | 0.79 | 3.43 | 1.15 | 3.77 | 0.99 |

| Waste, when managed effectively, can be a valuable resource | 3.38 | 1.06 | 2.08 | 0.99 | 2.73 | 1.02 |

| The protection of forest resources directly impacts air quality | 2.24 | 1.10 | 3.87 | 1.09 | 3.05 | 1.05 |

| The establishment of protected areas is paramount for the preservation | 3.60 | 1.01 | 4.04 | 1.00 | 3.99 | 1.05 |

| The utilization of fossil fuels poses direct threats to human health | 4.13 | 0.75 | 3.95 | 1.06 | 4.04 | 1.01 |

| Governments, bear the primary responsibility for the resources | 3.45 | 1.06 | 3.93 | 1.19 | 3.69 | 1.13 |

| Environmental protection is achieved through laws and strategies | 3.83 | 0.91 | 3.79 | 1.00 | 3.81 | 0.92 |

| Effective waste management, the most pressing, environmental challenge | 3.71 | 1.10 | 4.02 | 0.85 | 3.87 | 0.95 |

| Environmental safety variables | Montenegro | North Macedonia |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

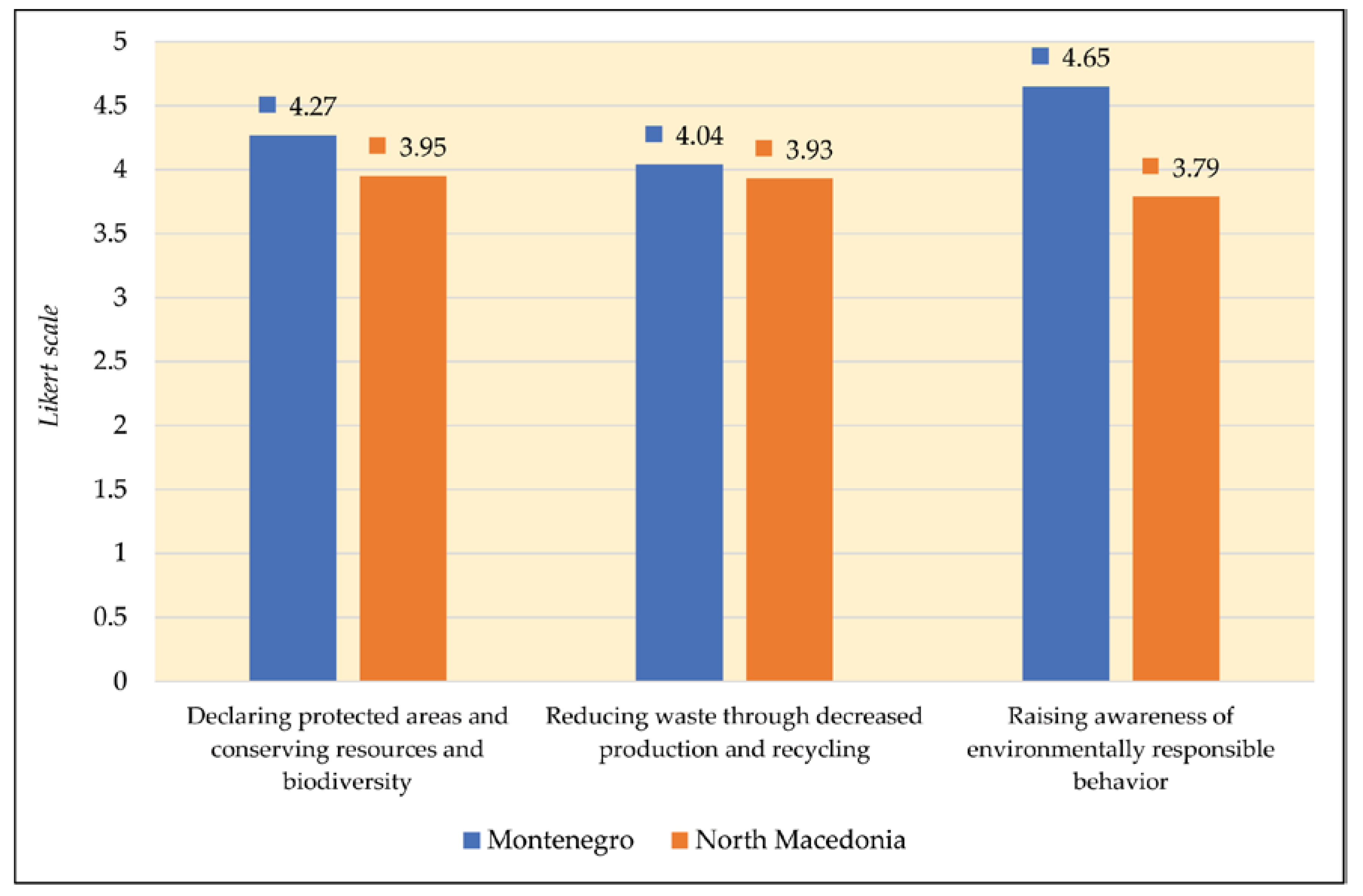

| Declaring protected areas and conserving resources, biodiversity | 4.27 | 0.87 | 3.95 | 1.06 | 4.11 | 0.98 |

| Reducing waste through decreased production and recycling | 4.04 | 1.05 | 3.93 | 1.19 | 3.98 | 1.12 |

| Raising awareness of environmentally responsible behavior | 4.65 | 0.59 | 3.79 | 1.00 | 4.22 | 0.81 |

| Variables | Age | |

|---|---|---|

| Sig. | r | |

| Humanity's survival hinges on natural resource accessibility | 0.000** | 0.209 |

| Natural resources are universally available | 0.035* | 0.106 |

| Individuals significantly influence the environment | 0.002* | 0.154 |

| Environmental conditions profoundly impact human health | 0.013* | 0.123 |

| All natural resources have renewable potential | 0.002* | 0.156 |

| Development often harms the environment | 0.470 | 0.042 |

| Immersion in nature fosters environmental stewardship | 0.918 | 0.005 |

| Resource scarcity jeopardizes national security and well-being | 0.000** | 0.244 |

| Legal regulations govern nature conservation | 0.000** | 0.266 |

| Biodiversity preservation is vital for humanity | 0.000** | 0.189 |

| Humanity is responsible for environmental damage | 0.832 | 0.011 |

| Environmental awareness begins in families | 0.000** | 0.204 |

| Knowledge fosters environmental awareness | 0.054 | 0.96 |

| Collective action protects nature | 0.960 | 0.003 |

| Nature benefits humanity | 0.297 | 0.052 |

| Declaring protected areas and conserving resources and biodiversity | 0.333 | 0.049 |

| Reducing waste through decreased production and recycling | 0.026* | ̶ 0.112 |

| Raising awareness of environmentally responsible behavior | 0.090 | 0.086 |

| Variable | F | t | Sig. (2-Tailed) |

df | Male M (SD) |

Female M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival hinges on resource accessibility | 0.041 | ̶ 3.072 | 0.002* | 392 | 4.00 (1.017) | 4.31 (0.921) |

| Resources are universally available | 0.112 | 3.470 | 0.719 | 396 | 3.08 (1.077) | 3.12 (1.200) |

| Individuals influence the environment | 50.819 | 0.000 | 0.001** | 396 | 4.78 (0.441) | 4.58 (0.665) |

| Environmental conditions affect health | 6.231 | ̶ 0.360 | 0.139 | 392 | 4.66 (0.774) | 4.76 (0.608) |

| All resources have renewable potential | 6.244 | ̶ 0.359 | 0.082 | 396 | 2.69 (1.084) | 2.90 (1.308) |

| Development harms the environment | 7.483 | 3.470 | 0.045* | 396 | 3.73 (0.891) | 3.50 (1.103) |

| Nature immersion fosters stewardship | 14.49 | 3.430 | 0.087 | 392 | 4.29 (0.810) | 4.11 (1.180) |

| Resource scarcity jeopardizes security | 5.926 | ̶ 1.472 | 0.720 | 396 | 4.12 (0.840) | 4.09 (1.040) |

| Legal regulations govern conservation | 1.791 | ̶ 1.483 | 0.365 | 392 | 3.19 (1.100) | 3.29 (1.203) |

| Biodiversity preservation is vital | 6.790 | ̶ 1.746 | 0.310 | 298 | 2.17 (0.972) | 2.27 (0.991) |

| Humanity is responsible for the damage | 1.905 | ̶ 1.730 | 0.983 | 388 | 3.88 (1.099) | 3.87 (1.168) |

| Environmental awareness begins in families | 24.23 | 1.953 | 0.000** | 396 | 4.12 (0.942) | 3.70 (1.247) |

| Knowledge fosters environmental awareness | 7.057 | 2.011 | 0.017** | 392 | 4.20 (0.800) | 3.97 (1.094) |

| Collective action protects nature | 5.547 | 1.714 | 0.657 | 396 | 4.19 (0.843) | 4.15 (1.027) |

| Nature benefits humanity | 2.256 | 1.707 | 0.356 | 392 | 3.74 (1.216) | 3.86 (1.289) |

| Protected areas and biodiversity conservation | 0.786 | 1.429 | 0.376 | 393 | 4.21 (0.812) | 4.08 (0.941) |

| Waste reduction and recycling | 1.836 | 1.124 | 0.176 | 394 | 4.03 (1.11) | 3.89 (1.23) |

| Environmental behaviour awareness | 28.65 | 3.689 | 0.000** | 395 | 4.65 (0.53) | 4.36 (0.994) |

| Variables | Place of Residence |

Study Year |

Study Rate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Survival hinges on resource accessibility | 0.038 | 0.963 | 6.159 | 0.000** | 6.727 | 0.000** |

| Resources are universally available | 1.689 | 0.186 | 0.966 | 0.409 | 3.410 | 0.018* |

| Individuals influence the environment | 0.326 | 0.722 | 1.779 | 0.151 | 0.585 | 0.625 |

| Environmental conditions affect health | 1.113 | 0.330 | 6.842 | 0.000** | 0.825 | 0.481 |

| All resources have renewable potential | 0.102 | 0.903 | 4.603 | 0.004* | 8.246 | 0.000** |

| Development harms the environment | 1.374 | 0.255 | 6.361 | 0.000** | 8.370 | 0.000** |

| Nature immersion fosters stewardship | 0.775 | 0.462 | 0.605 | 0.612 | 2.092 | 0.101 |

| Resource scarcity jeopardizes security | 3.706 | 0.025* | 4.468 | 0.004* | 12.589 | 0.000** |

| Legal regulations govern conservation | 0.526 | 0.591 | 4.546 | 0.003* | 7.641 | 0.000** |

| Biodiversity preservation is vital | 10.720 | 0.000** | 2.651 | 0.048* | 1.856 | 0.137 |

| Humanity is responsible for the damage | 0.341 | 0.711 | 0.982 | 0.401 | 6.952 | 0.000** |

| Environmental awareness begins in families | 2.042 | 0.131 | 1.914 | 0.127 | 4.125 | 0.007* |

| Knowledge fosters environmental awareness | 2.101 | 0.124 | 2.647 | 0.049* | 2.933 | 0.033* |

| Collective action protects nature | 2.675 | 0.070 | 1.463 | 0.224 | 29.241 | 0.000** |

| Nature benefits humanity | 2.732 | 0.066 | 10.419 | 0.000** | 2.732 | 0.044* |

| Protected areas and biodiversity conservation | 1.212 | 0.299 | 1.005 | 0.391 | 6.991 | 0.000** |

| Waste reduction and recycling | 0.442 | 0.643 | 2.150 | 0.093 | 13.519 | 0.000** |

| Environmental behaviour awareness | 1.388 | 0.251 | 4.224 | 0.006* | 3.284 | 0.021* |

| Variables | Age | |

|---|---|---|

| Sig. | r | |

| Sustainable development involves finding a harmonious equilibrium | 0.010* | 0.131 |

| Human activities stand as the primary catalysts of climate change | 0.001** | 0.165 |

| The protection of flora and fauna is imperative for their preservation | 0.105 | 0.081 |

| Recycling efforts contribute significantly to energy conservation | 0.350 | 0.047 |

| Human actions indeed have an impact on the ozone layer | 0.612 | 0.026 |

| Water resources, contrary to common belief, are not inexhaustible | 0.766 | ̶ 0.015 |

| Human activities, beyond mere usage, affect the quality of water | 0.129 | ̶ 0.076 |

| Vehicle emissions are contributor to the depletion of the ozone layer | 0.001** | 0.159 |

| Waste, when managed effectively, can be a valuable resource | 0.005* | ̶ 0.140 |

| The protection of forest resources directly impacts air quality | 0.886 | ̶ 0.007 |

| The establishment of protected areas, preservation of nature | 0.146 | 0.073 |

| The utilization of fossil fuels poses direct threats to human health | 0.027* | 0.110 |

| Governments, bear the primary responsibility for the resources | 0.001** | 0.172 |

| Environmental protection is achieved through laws and strategies | 0.004* | 0.145 |

| Effective waste management: the most pressing environmental challenge | 0.000** | 0.298 |

| Variable | F | t | Sig. (2-Tailed) |

df | Male M (SD) |

Female M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable development | 57.10 | 1.909 | 0.057 | 382 | 3.84 (0.715) | 3.67 (1.001) |

| Human activities and climate change | 14.11 | 2.847 | 0.005* | 394 | 3.71 (0.938) | 3.37 (1.412) |

| Flora and fauna preservation | 18.08 | 2.819 | 0.959 | 382 | 3.37 (1.412) | 4.28 (1.038) |

| Recycling and energy conservation | 117.78 | 2.204 | 0.028* | 394 | 4.17 (0.801) | 3.93 (1.283) |

| Human actions and the ozone layer | 13.64 | 2.185 | 0.000** | 394 | 1.86 (0.874) | 2.62 (1.432) |

| Water resources sustainability | 1.527 | ̶ 6.299 | 0.000** | 392 | 2.05 (1.060) | 2.52 (1.217) |

| Human activities and water quality | 14.66 | ̶ 6.255 | 0.003* | 382 | 2.74 (1.102) | 3.09 (1.251) |

| Vehicle emissions and the ozone layer | 0.111 | ̶ 4.106 | 0.000** | 390 | 4.00 (0.888) | 3.64 (1.110) |

| Waste management | 0.011 | ̶ 4.098 | 0.871 | 382 | 3.41 (1.106) | 3.39 (1.123) |

| Forest resources and air quality | 0.077 | ̶ 2.995 | 0.287 | 390 | 2.10 (1.069) | 2.22 (1.037) |

| Protected areas and nature preservation | 5.283 | ̶ 2.986 | 0.109 | 382 | 3.65 (1.010) | 3.82 (1.114) |

| Fossil fuels and human health | 0.302 | 3.560 | 0.000** | 394 | 4.30 (0.669) | 3.85 (1.031) |

| Government responsibility for resources | 19.92 | 3.537 | 0.890 | 382 | 3.69 (1.051) | 3.71 (1.141) |

| Environmental protection laws and strategies | 19.95 | 0.162 | 0.565 | 396 | 3.91 (0.871) | 3.84 (1.240) |

| Waste management in North Macedonia | 57.10 | ̶ 1.066 | 0.321 | 396 | 3.80 (0.944) | 3.68 (1.159) |

| Variables | Place of Residence |

Study Year |

Study Rate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Sustainable development | 0.165 | 0.848 | 1.540 | 0.204 | 15.933 | 0.000** |

| Human activities and climate change | 0.553 | 0.575 | 6.886 | 0.000** | 3.282 | 0.021* |

| Flora and fauna preservation | 4.450 | 0.012* | 2.638 | 0.049* | 0.759 | 0.518 |

| Recycling and energy conservation | 0.346 | 0.708 | 3.047 | 0.029* | 8.499 | 0.000** |

| Human actions and the ozone layer | 1.043 | 0.353 | 4.399 | 0.005* | 10.124 | 0.000** |

| Water resources sustainability | 0.674 | 0.510 | 4.896 | 0.002* | 1.504 | 0.213 |

| Human activities and water quality | 0.768 | 0.465 | 11.931 | 0.000** | 5.299 | 0.001** |

| Vehicle emissions and the ozone layer | 5.682 | 0.004* | 20.532 | 0.000** | 3.702 | 0.012* |

| Waste management | 0.558 | 0.573 | 10.142 | 0.000** | 4.173 | 0.006* |

| Forest resources and air quality | 0.606 | 0.546 | 9.518 | 0.000** | 5.600 | 0.001** |

| Protected areas and nature preservation | 0.785 | 0.457 | 1.892 | 0.130 | 2.383 | 0.069 |

| Fossil fuels and human health | 0.477 | 0.621 | 4.332 | 0.005* | 1.322 | 0.267 |

| Government responsibility for resources | 1.156 | 0.316 | 6.188 | 0.000** | 0.148 | 0.931 |

| Environmental protection laws and strategies | 0.896 | 0.409 | 1.579 | 0.194 | 3.191 | 0.024* |

| Waste management in North Macedonia | 2.329 | 0.099 | 7.038 | 0.000** | 12.281 | 0.000** |

| State of the environment | Region | ||||||||

| Central | Southern | Northern | |||||||

| Type of completed secondary school | |||||||||

| High School | Medical School | Other Secondary Schools училишта | High School | Medical School | Other Secondary Schools училишта | High School | Medical School | Other Secondary Schools училишта | |

| Bad | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Good | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Excellent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Environmental condition | Year of Study | |||||||

| I | II | III | IV | |||||

| Regular | Non-regular | Regular | Non-regular | Regular | Non-regular | Regular | Non-regular | |

| Poor | 2 | / | 2 | / | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Good | 2 | / | 3 | / | 1 | / | 1 | / |

| Excellent | 1 | / | 0 | / | / | / | / | / |

| Total | 5 | / | 5 | / | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Year, number, and status of the student according to the year of study | Offered questions | ||||||||||||||||

| National parks present in Montenegro | Protection of natural resources occurs in national parks | Protection of natural resources | |||||||||||||||

| Regular | Non-regular | Regular | Non-regular | Regular | Non-regular | Regular | Non-regular | ||||||||||

| a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | a | b | a | b | c | a | b | c | ||

| 5 | 0 | / | / | 5 | / | / | / | 5 | / | / | / | 1 | / | 4 | / | / | / |

| I | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 5 | 0 | / | / | 5 | / | / | / | 5 | / | / | / | 2 | / | 3 | / | / | / |

| II | / | / | 5 | / | / | / | 5 | / | / | / | 2 | / | 3 | / | / | / | |

| 2 | 2 | / | / | 2 | / | / | 2 | 2 | / | 2 | / | 2 | / | / | 1 | / | 1 |

| III | / | / | 2 | / | / | 2 | 2 | / | 2 | / | 2 | / | / | 1 | / | 1 | |

| 2 | 1 | / | / | / | 1 | / | / | 2 | / | 1 | / | 1 | 1 | / | 1 | / | / |

| IV | / | / | 2 | / | / | 2 | / | 1 | / | 1 | 1 | / | 1 | / | / | ||

| 14 | 3 | / | / | 14 | 1 | / | 2 | 14 | / | 3 | / | 6 | 1 | 7 | 2 | / | 1 |

| 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | ||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).