Submitted:

29 April 2024

Posted:

30 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

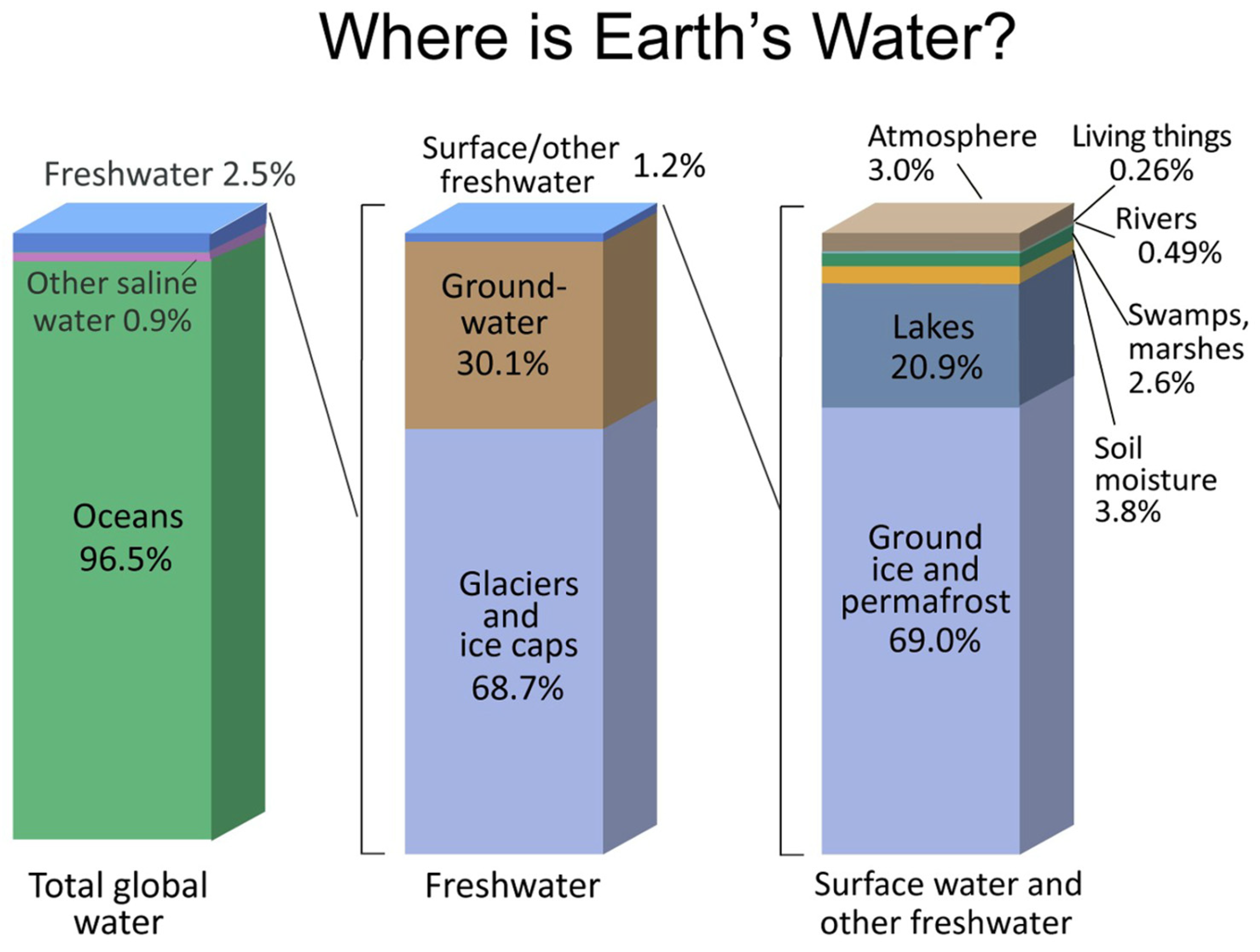

1.2. Freshwater Systems

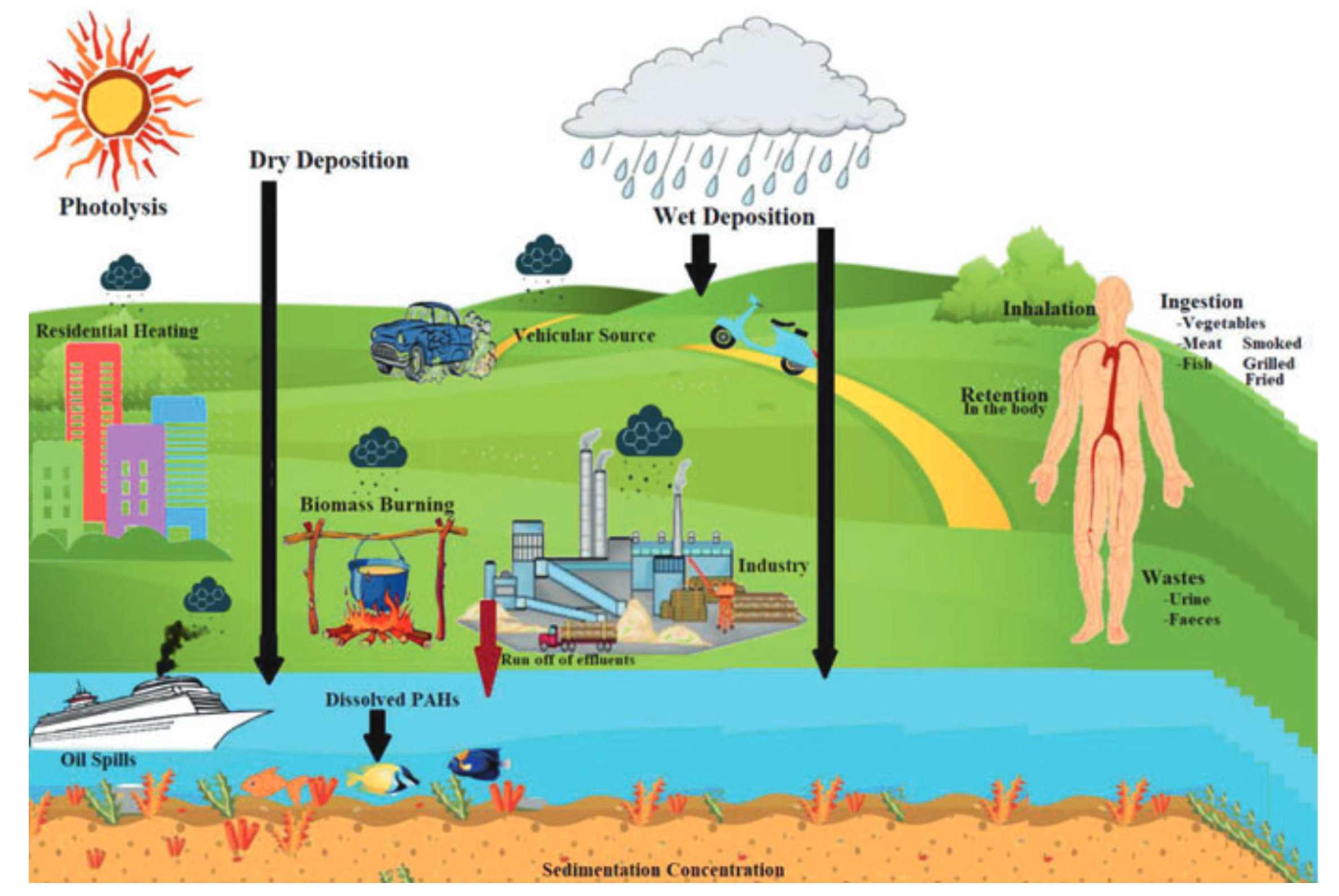

2. Sources of PAHs in Freshwater Environments

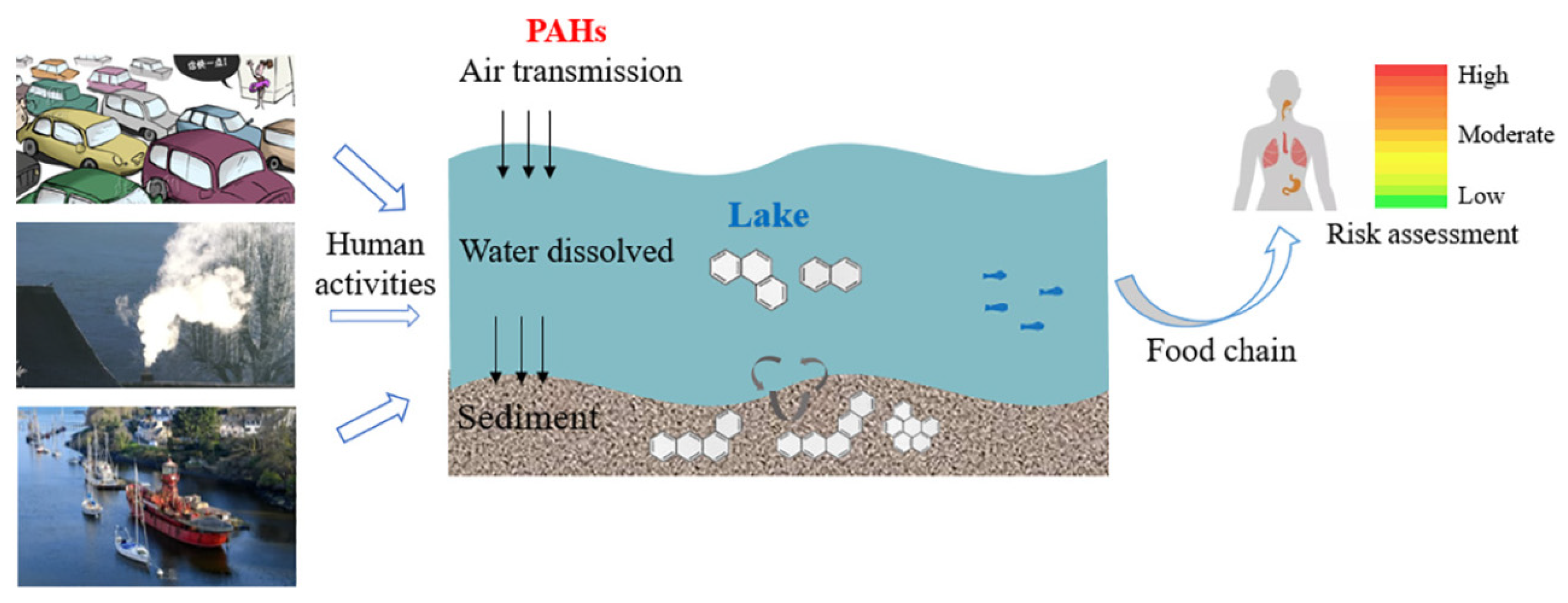

2.1. Lakes

2.2. Rivers

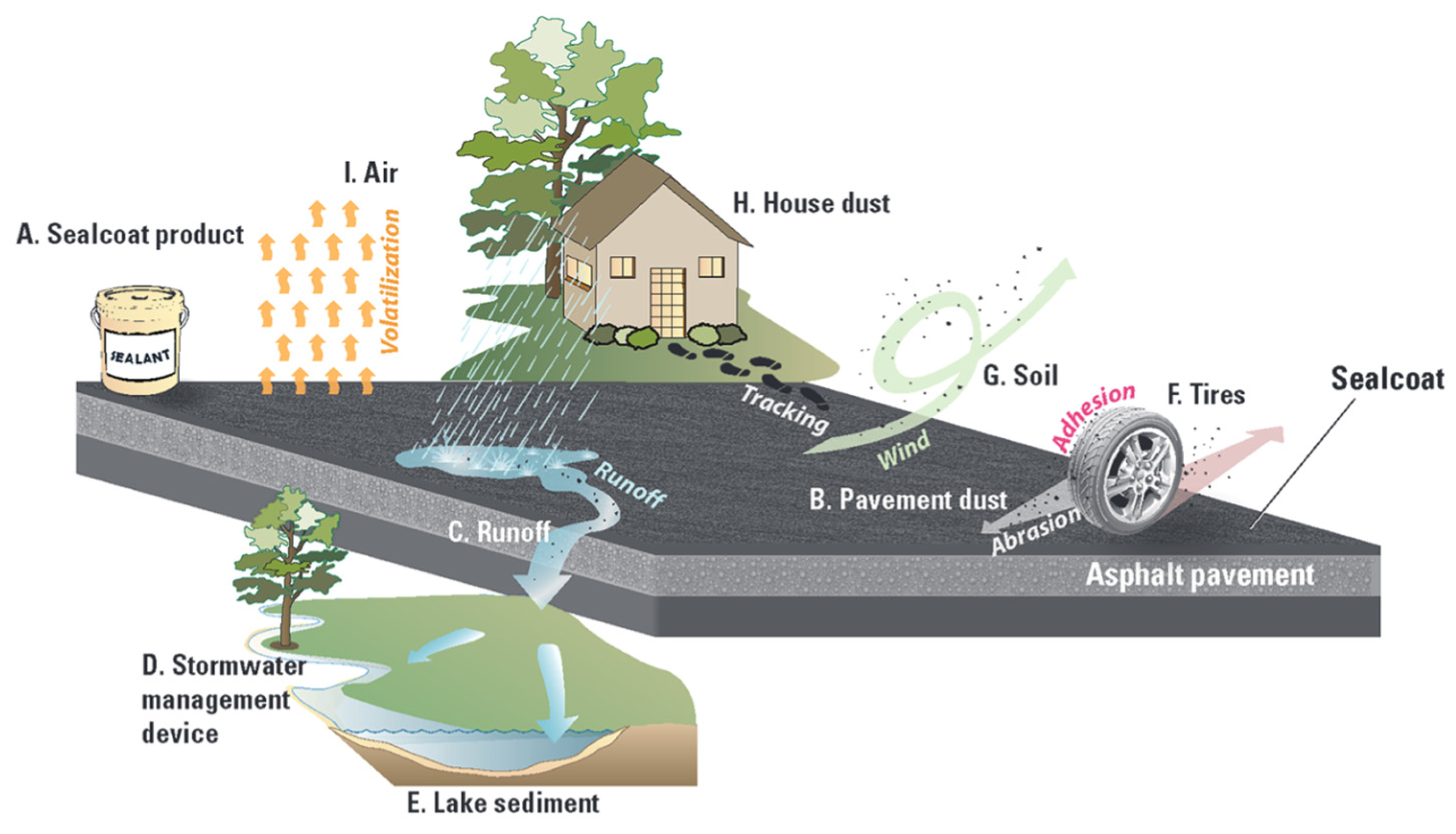

2.3. Streams

2.4. Groundwater

2.5. Wetlands

2.6. Glaciers

3. Distribution of PAHs in Water Systems

3.1. Transport Mechanisms of PAHs in Water Bodies

3.2. Factors Affecting the Distribution

3.3. Interaction with Environmental Matrices

4. Ecotoxicological Impacts of PAHs

4.1. Molecular and Cellular Level Effects

4.2. Impact on Aquatic Organisms

4.2.1. Bioaccumulation

4.2.2. Mutagenic and Carcinogenic Effects

4.3. Case Studies of PAH Impact in Specific Water Systems

5. Characterization and Quantification of PAHs

5.1. Characterization Techniques

5.2. Advanced Methodologies

6. Regulatory Frameworks

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

List of Acronyms

| PAH | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon |

| LMW-PAH | Low molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon |

| HMW-PAH | High molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon |

| USEPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| LRT | Long-range transport |

| ETM | Estuarine turbidity maximum |

| BCF | Bioconcentration factor |

| Kow | Octanol-water partition coefficient |

| Koc | Organic carbon normalized sediment–water partition coefficient |

| Kpm | Particulate matter–water distribution coefficient |

| A-PAH | Alkylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon |

| YRD | Yellow River Delta |

| SPM | Suspended particulate matter |

| PES | Paranaguá Estuarine System |

| TOC/TN | Total organic carbon/total nitrogen ratio |

| δ13C | 13C isotropic chemical shift |

| SWRP | Stormwater retention pond |

| HC5 | Hazardous concentration levels for 5% of species |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| DW | Dry weight |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| CAT | Catalase |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| PCB | Polychlorinated biphenyl |

| BAF | Bioaccumulation factor |

| BaP | Benzo[a]pyrene |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| 3-OHBcP | 3-hydroxybenzo[c]phenanthrene |

| SRKWs | Southern resident killer whales |

| FTT | FAO-Thiaroye processing technique |

| SPE | Solid-Phase Extraction |

| SPME | Solid-Phase Microextraction |

| LLE | Liquid-Liquid Extraction |

| DLLME | Dispersive liquid-liquid micro-extraction |

| ILDLLME | Ionic Liquid-Based Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction |

| SFE | Supercritical Fluid Extraction |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry |

| HPLC-UV | High-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection |

| HPLC-DAD-FLD | High-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array and fluorescence detection |

| HPLC-FLD-UV | High-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence and ultraviolet detection |

| GO | Graphene oxide |

| Ag/pg-CN | Silver nanoparticles embedded within a porous graphitic carbon nitride matrix |

| SERS | Surface-enhanced Raman scattering |

| FL | Fluoranthene |

| NAP | Naphthalene |

| MOF | Metal-organic framework |

| RSD | Relative standard deviation |

| EEM | Excitation-emission matrix |

| PARAFAC | Parallel factor analysis |

| CLIA | Chemiluminescence immunoassay |

| FIA | Fluoroimmunoassay |

| RIA | Radioimmunoassay |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| OHPAH | Hydroxylated PAH |

| ALIE | Average local ionization energy |

| LHA | Leonardite humic acid |

| PHE | Phenanthrene |

| OPAH | Oxygenated PAH |

| NPAH | Nitrated PAH |

| CWA | Clean Water Act |

| SDWA | Safe Drinking Water Act |

References

- Patel, A.B.; Shaikh, S.; Jain, K.R.; Desai, C.; Madamwar, D. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Sources, Toxicity, and Remediation Approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 562813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus, F.; Pereira, J.L.; Campos, I.; Santos, M.; Ré, A.; Keizer, J.; Nogueira, A.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Abrantes, N.; Serpa, D. A Review on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Distribution in Freshwater Ecosystems and Their Toxicity to Benthic Fauna. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 820, 153282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Balachandran, S.; Rafiqul Hoque, R. Sources of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments of the Bharalu River, a Tributary of the River Brahmaputra in Guwahati, India. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2015, 122, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edokpayi, J.; Odiyo, J.; Popoola, O.; Msagati, T. Determination and Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Rivers, Sediments and Wastewater Effluents in Vhembe District, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016, 13, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupte, A.; Tripathi, A.; Patel, H.; Rudakiya, D.; Gupte, S. Bioremediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAHs): A Perspective. The Open Biotechnology Journal 2016, 10, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumard, P.; Budzinski, H.; Michon, Q.; Garrigues, P.; Burgeot, T.; Bellocq, J. Origin and Bioavailability of PAHs in the Mediterranean Sea from Mussel and Sediment Records. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 1998, 47, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Suzuki, N. Toxicities of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons for Aquatic Animals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, Y.B.; Mo, W.Y.; Zhang, F.; Wong, M.H. Health Risk Assessments Based on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Freshwater Fish Cultured Using Food Waste-Based Diets. Environmental Pollution 2020, 256, 113380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez García, M.; García de Llasera, M.P. A Review on the Enzymes and Metabolites Identified by Mass Spectrometry from Bacteria and Microalgae Involved in the Degradation of High Molecular Weight PAHs. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 797, 149035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Jing, C. Anthropogenic PAHs in Lake Sediments: A Literature Review (2002–2018). Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 2018, 20, 1649–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S.M. A Review on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Source, Environmental Impact, Effect on Human Health and Remediation. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum 2016, 25, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, P.D.; Page, D.S.; Brown, J.S.; Neff, J.M.; Burns, W.A. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Levels in Mussels from Prince William Sound, ALASKA, USA, Document the Return to Baseline Conditions. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2004, 23, 2916–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baali, A.; Yahyaoui, A.; Baali, A.; Yahyaoui, A. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Their Influence to Some Aquatic Species. In Biochemical Toxicology - Heavy Metals and Nanomaterials; IntechOpen, 2019 ISBN 978-1-78984-697-3.

- Provencher, J.F.; Thomas, P.J.; Pauli, B.; Braune, B.M.; Franckowiak, R.P.; Gendron, M.; Savard, G.; Sarma, S.N.; Crump, D.; Zahaby, Y.; et al. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds (PACs) and Trace Elements in Four Marine Bird Species from Northern Canada in a Region of Natural Marine Oil and Gas Seeps. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 744, 140959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosein, A.; Mohammed, A.; Umaharan, P.; Ramsubhag, A. Examining the Soils Adjacent to the Historical Pitch Lake for Levels of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (Pahs) and Naturally Occurring Pah-Degrading Bacteria. American Research Journal of Earth Science 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlystov, O.M.; Izosimova, O.N.; Hachikubo, A.; Minami, H.; Makarov, M.M.; Gorshkov, A.G. A New Oil and Gas Seep in Lake Baikal. Pet. Chem. 2022, 62, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.J.; DiToro, D.M.; McGrath, J.A.; Swartz, R.C.; Mount, D.R.; Spehar, R.L.; Burgess, R.M.; Ozretich, R.J.; Bell, H.E.; Reiley, M.C.; et al. Procedures for the Derivation of Equilibrium Partitioning Sediment Benchmarks (ESBs) for the Protection of Benthic Organisms: PAH Mixtures 2003.

- Dhar, K.; Subashchandrabose, S.R.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Krishnan, K.; Megharaj, M. Anaerobic Microbial Degradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: A Comprehensive Review. In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Volume 251; de Voogt, P., Ed.; Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 25–108 ISBN 978-3-030-27149-7.

- Wilcke, W.; Amelung, W.; Krauss, M.; Martius, C.; Bandeira, A.; Garcia, M. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) Patterns in Climatically Different Ecological Zones of Brazil. Organic Geochemistry 2003, 34, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyo-Ita, O.E.; Oyo-Ita, I.O.; Ugim, S.U. Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Sterols in Termite Nest, Soil, and Sediment from Great Kwa River, SE Nigeria. Environ Monit Assess 2013, 185, 1413–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, H.; Toyota, M.; Asakawa, Y.; Kawano, S. Naphthalene—a Constituent of Magnolia Flowers. Phytochemistry 1996, 42, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgens, A.; Webber, A.C.; Gottsberger, G. Floral Scent Compounds of Amazonian Annonaceae Species Pollinated by Small Beetles and Thrips. Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, C.; Parrott, J.L.; Frank, R.A.; Yang, Z.; Brown, C.E.; Hollebone, B.P.; Landriault, M.; Fieldhouse, B.; Liu, Y.; et al. Forensic Source Differentiation of Petrogenic, Pyrogenic, and Biogenic Hydrocarbons in Canadian Oil Sands Environmental Samples. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2014, 271, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, M.; Ragone, R.; Dell’Anna, M.M.; Romanazzi, G.; Damiani, L.; Mastrorilli, P. Improved Identification of Pollution Source Attribution by Using PAH Ratios Combined with Multivariate Statistics. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 19298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, S.Y.; Suratman, S.; Latif, M.T.; Khan, M.F.; Simoneit, B.R.T.; Mohd Tahir, N. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Coastal Sediments of Southern Terengganu, South China Sea, Malaysia: Source Assessment Using Diagnostic Ratios and Multivariate Statistic. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 15849–15862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashayeri, N.Y.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Kersten, M.; Yazdi, M.; Lahijanzadeh, A.R. Presence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments and Surface Water from Shadegan Wetland – Iran: A Focus on Source Apportionment, Human and Ecological Risk Assessment and Sediment-Water Exchange. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 148, 1054–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Santillo, D.; Johnston, P.; Fayad, G.; Baker, K.L.; Law, R.J. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Oysters from Coastal Waters of the Lebanon 10 Months after the Jiyeh Oil Spill in 2006. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2008, 56, 1215–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoli, E.; Samara, C. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Natural Waters: Sources, Occurrence and Analysis. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 1999, 18, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cui, W.; Meng, X.; Tang, X. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Organochlorine Pesticides in Surface Water from the Yongding River Basin, China: Seasonal Distribution, Source Apportionment, and Potential Risk Assessment. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 618, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, P.; Xia, S.; Huang, Q.; nueva, E. a sitio externo E. enlace se abrirá en una ventana Contamination of 16 Priority Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Urban Source Water at the Tidal Reach of the Yangtze River. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 61222–61235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojiri, A.; Zhou, J.L.; Ohashi, A.; Ozaki, N.; Kindaichi, T. Comprehensive Review of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water Sources, Their Effects and Treatments. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 696, 133971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information PubChem Dataset 2023.

- Shen, H. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons; Springer Theses; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2016; ISBN 978-3-662-49678-7.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Toxicological Profile for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons 1996.

- Mackay, D.; Shiu, W.-Y.; Shiu, W.-Y.; Lee, S.C. Handbook of Physical-Chemical Properties and Environmental Fate for Organic Chemicals; 0 ed.; CRC Press, 2006; ISBN 978-0-429-15007-4.

- Bralewska, K.; Rakowska, J. Concentrations of Particulate Matter and PM-Bound Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Released during Combustion of Various Types of Materials and Possible Toxicological Potential of the Emissions: The Results of Preliminary Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xing, W.; Wei, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhao, L.; Toriba, A.; Hayakawa, K.; et al. Size Distribution of Particulate Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Fresh Combustion Smoke and Ambient Air: A Review. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2020, 88, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K.; Nohchi, M.; Yang, X.; Sugiyama, T.; Miura, K.; Takami, A.; Sato, K.; Chen, X.; Kato, S.; Kajii, Y.; et al. Degradation of PAHs during Long Range Transport Based on Simultaneous Measurements at Tuoji Island, China, and at Fukue Island and Cape Hedo, Japan. Environmental Pollution 2020, 260, 113906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, K.; Hoque, R.R.; Balachandran, S.; Medhi, S.; Idris, M.G.; Rahman, M.; Hussain, F.L. Monitoring and Risk Analysis of PAHs in the Environment. In Handbook of Environmental Materials Management; Hussain, C.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 973–1007. ISBN 978-3-319-73645-7. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.S.B. , Astha Bhatia, Gulshan Bhagat, Simran Singh, Salwinder Singh Dhaliwal, Vivek Sharma, Vibha Verma, Rui Yin, Jaswinder PAHs in Terrestrial Environment and Their Phytoremediation. In Bioremediation for Sustainable Environmental Cleanup; CRC Press, 2024 ISBN 978-1-00-327794-1.

- Montuori, P.; De Rosa, E.; Di Duca, F.; De Simone, B.; Scippa, S.; Russo, I.; Sarnacchiaro, P.; Triassi, M. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Dissolved Phase, Particulate Matter, and Sediment of the Sele River, Southern Italy: A Focus on Distribution, Risk Assessment, and Sources. Toxics 2022, 10, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Qadeer, A.; Liu, M.; Zhu, J.-M.; Huang, Y.-P.; Du, W.-N.; Wei, X.-Y. Occurrence, Source, and Partition of PAHs, PCBs, and OCPs in the Multiphase System of an Urban Lake, Shanghai. Applied Geochemistry 2019, 106, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathey, A.L.; Watkins, D.J.; Rosario, Z.Y.; Vélez Vega, C.M.; Loch-Caruso, R.; Alshawabkeh, A.N.; Cordero, J.F.; Meeker, J.D. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Exposure Results in Altered CRH, Reproductive, and Thyroid Hormone Concentrations during Human Pregnancy. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 749, 141581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Song, Y.; He, F.; Jing, M.; Tang, J.; Liu, R. A Review of Human and Animals Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Health Risk and Adverse Effects, Photo-Induced Toxicity and Regulating Effect of Microplastics. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 773, 145403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, F.; Rocha, B.A.; Souza, M.C.O.; Bocato, M.Z.; Azevedo, L.F.; Adeyemi, J.A.; Santana, A.; Campiglia, A.D. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): Updated Aspects of Their Determination, Kinetics in the Human Body, and Toxicity. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 2023, 26, 28–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baran, A.; Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A.; Ukalska-Jaruga, A.; Mierzwa-Hersztek, M.; Gondek, K.; Szara-Bąk, M.; Tarnawski, M.; Spałek, I. Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Bottom Sediments of a Dam Reservoir, Their Interaction with Organic Matter and Risk to Benthic Fauna. J Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 2418–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.; Abrantes, N. Forest Fires as Drivers of Contamination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons to the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 2021, 24, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiklomanov, I. World Fresh Water Resources. In Water in Crisis: A Guide to the World’s Fresh Water Resources; Gleick, P.H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 1993 ISBN 0-19-507628-1.

- Shiklomanov, I.A. Appraisal and Assessment of World Water Resources. Water International 2000, 25, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.J.; Carlson, A.K.; Creed, I.F.; Eliason, E.J.; Gell, P.A.; Johnson, P.T.J.; Kidd, K.A.; MacCormack, T.J.; Olden, J.D.; Ormerod, S.J.; et al. Emerging Threats and Persistent Conservation Challenges for Freshwater Biodiversity. Biological Reviews 2019, 94, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleick, P.H. Water Resources. In Encyclopedia of Climate and Weather; Oxford University Press: New York, 1996; pp. 817–823. [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon, D.; Arthington, A.H.; Gessner, M.O.; Kawabata, Z.-I.; Knowler, D.J.; Lévêque, C.; Naiman, R.J.; Prieur-Richard, A.-H.; Soto, D.; Stiassny, M.L.J.; et al. Freshwater Biodiversity: Importance, Threats, Status and Conservation Challenges. Biological Reviews 2006, 81, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irfan, S.; Alatawi, A.M.M. Aquatic Ecosystem and Biodiversity: A Review. Open Journal of Ecology 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, J.S.; Destouni, G.; Duke-Sylvester, S.M.; Magurran, A.E.; Oberdorff, T.; Reis, R.E.; Winemiller, K.O.; Ripple, W.J. Scientists’ Warning to Humanity on the Freshwater Biodiversity Crisis. Ambio 2021, 50, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Geological Survey The Distribution of Water on, in, and above the Earth. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/distribution-water-and-above-earth (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- UNEP Global Chemicals Outlook II: From Legacies to Innovative Solutions; United Nations Environment Programme: Geneva, 2019.

- Kuhn, A.V.; Pont, G.D.; Cozer, N.; Sadauskas-Henrique, H. The Concentrations of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Fish: A Systematic Review. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2024, 198, 115778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Zhao, Z.; Lang, Z.; Qin, Z.; Zhu, Y. Exploring the Cumulative Selectivity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Phytoplankton, Water, and Sediment in Typical Urban Water Bodies. Water 2022, 14, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmvahm, H.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Zarei, M.; Esmaeili, H.R.; Hooda, P.S. Investigation of the Concentration, Origin and Health Effects of PAHs in the Anzali Wetland: The Most Important Coastal Freshwater Wetland of Iran. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2023, 193, 115191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetzel, D.L.; Van Vleet, E.S. Accumulation and Distribution of Petroleum Hydrocarbons Found in Mussels (Mytilus Galloprovincialis) in the Canals of Venice, Italy. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2004, 48, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambade, B.; Sethi, S.S. Health Risk Assessment and Characterization of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon from the Hydrosphere. Journal of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste 2021, 25, 05020008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Souza, M.R.R.; Junior, A.R.V.; da Silva Soares, L.; Frena, M.; Alexandre, M.R. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Suspended Particulate Matter of a Region Influenced by Agricultural Activities in Northeast Brazil. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2023, 57, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayanand, M.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Subramanian, R.; Issac, P.K.; Nasr, M.; Khoo, K.S.; Rajagopal, R.; Greff, B.; Wan Azelee, N.I.; Jeon, B.-H.; et al. Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Water Environment: A Review on Toxicity, Microbial Biodegradation, Systematic Biological Advancements, and Environmental Fate. Environmental Research 2023, 227, 115716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.-Y.; Zhang, T.; Fang, H.H.-P. Bacteria-Mediated PAH Degradation in Soil and Sediment. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 89, 1357–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Yu, H.; Shi, K.; Shang, N.; He, Y.; Meng, L.; Huang, T.; Yang, H.; Huang, C. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Remote Lakes from the Tibetan Plateau: Concentrations, Source, Ecological Risk, and Influencing Factors. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 319, 115689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, W.A. Sampling Techniques for Organic Substances in Surface Waters. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry 1994, 57, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frapiccini, E.; Panfili, M.; Guicciardi, S.; Santojanni, A.; Marini, M.; Truzzi, C.; Annibaldi, A. Effects of Biological Factors and Seasonality on the Level of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Red Mullet (Mullus Barbatus). Environmental Pollution 2020, 258, 113742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.E.; Hung, H.; Yu, Y.; Letcher, R.J.; Muir, D.C.G. Sources and Environmental Fate of Pyrogenic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Arctic. Emerging Contaminants 2019, 5, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kothiyal, N.C.; Saruchi; Vikas, P. ; Sharma, R. Sources, Distribution, and Health Effect of Carcinogenic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) – Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Journal of the Chinese Advanced Materials Society 2016, 4, 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dat, N.-D.; Chang, M.B. Review on Characteristics of PAHs in Atmosphere, Anthropogenic Sources and Control Technologies. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 609, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, S.; Bellini, A.; Scalici, M. Aquatic Plants and Ecotoxicological Assessment in Freshwater Ecosystems: A Review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 4975–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin, S.L.; Marchand, C. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Mangrove Ecosystems: A Review. Environmental Pollution 2022, 311, 119959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, B.K.; Das, A.; Sarkar, D.J.; Weerathunge, P.; Parida, P.K.; Das, B.K.; Thavamani, P.; Ramanathan, R.; Bansal, V. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Inland Aquatic Ecosystems: Perils and Remedies through Biosensors and Bioremediation. Environmental Pollution 2018, 241, 212–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simão, F.C.P.; Gravato, C.; Machado, A.L.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Pestana, J.L.T. Toxicity of Different Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) to the Freshwater Planarian Girardia Tigrina. Environ Pollut 2020, 266, 115185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Othman, H.; Pick, F.R.; Sakka Hlaili, A.; Leboulanger, C. Effects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Marine and Freshwater Microalgae – A Review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 441, 129869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famiyeh, Lord; Chen, K. ; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, Q.; Wang, C.; Lv, J.; Tang, Y.-T.; Yu, H.; Snape, C.; et al. A Review on Analysis Methods, Source Identification, and Cancer Risk Evaluation of Atmospheric Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 789, 147741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yao, S.; Xue, B. North-South Geographic Heterogeneity and Control Strategies for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Chinese Lake Sediments Illustrated by Forward and Backward Source Apportionments. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 431, 128545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lan, J.; Xie, Z.; Pu, J.; Yuan, D.; Yang, H.; Xing, B. Vertical Migration from Surface Soils to Groundwater and Source Appointment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Epikarst Spring Systems, Southwest China. Chemosphere 2019, 230, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birks, S.J.; Cho, S.; Taylor, E.; Yi, Y.; Gibson, J.J. Characterizing the PAHs in Surface Waters and Snow in the Athabasca Region: Implications for Identifying Hydrological Pathways of Atmospheric Deposition. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 603–604, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heintzman, L.J.; Anderson, T.A.; Carr, D.L.; McIntyre, N.E. Local and Landscape Influences on PAH Contamination in Urban Stormwater. Landscape and Urban Planning 2015, 142, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awonaike, B.; Lei, Y.D.; Parajulee, A.; Mitchell, C.P.J.; Wania, F. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Quinones in Urban and Rural Stormwater Runoff: Effects of Land Use and Storm Characteristics. ACS EST Water 2021, 1, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquès, M.; Mari, M.; Audí-Miró, C.; Sierra, J.; Soler, A.; Nadal, M.; Domingo, J.L. Climate Change Impact on the PAH Photodegradation in Soils: Characterization and Metabolites Identification. Environment International 2016, 89–90, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegbeleye, O.O.; Opeolu, B.O.; Jackson, V.A. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: A Critical Review of Environmental Occurrence and Bioremediation. Environmental Management 2017, 60, 758–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinpelumi, V.K.; Kumi, K.G.; Onyena, A.P.; Sam, K.; Ezejiofor, A.N.; Frazzoli, C.; Ekhator, O.C.; Udom, G.J.; Orisakwe, O.E. A Comparative Study of the Impacts of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water and Soils in Nigeria and Ghana: Towards a Framework for Public Health Protection. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2023, 11, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Xie, Z.; Zhi, L.; Wang, Z.; Qu, C. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Water Bodies of Dong Lake and Tangxun Lake, China: Spatial Distribution, Potential Sources and Risk Assessment. Water 2023, 15, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xu, J.; Yu, T.; Zhao, W. Spatial Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons from Lake Taihu, China. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2011, 87, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Zhang, T.; Jin, B.; Wang, Q.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhou, J.; et al. A Review on Occurrence and Risk of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Lakes of China. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 651, 2497–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, L.; Luo, X.; Cai, H.; Liu, F.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Q. Seasonal Dynamics of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons between Water and Sediment in a Tide-Dominated Estuary and Ecological Risks for Estuary Management. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2021, 162, 111831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keiser, D.A.; Shapiro, J.S. Consequences of the Clean Water Act and the Demand for Water Quality *. Quarterly Journal of Economics 2019, 134, 349–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, H. Does the “10-Point Water Plan” Reduce the Intensity of Industrial Water Pollution? Quasi-Experimental Evidence from China. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 295, 113048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, W. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of the “Source–Sink” Risk Pattern of NPS Pollution in the Upper Reaches of Erhai Lake Basin under Land Use Changes in 2005–2020. Water Air Soil Pollut 2022, 233, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colby GA. 2019. Deposition of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) into Northern Ontario Lake Sediments. bioRxiv.:786913. doi:10.1101/786913. [accessed 2021 May 7]. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/786913v1. [CrossRef]

- Mahler, B.J.; Metre, P.C.V.; Crane, J.L.; Watts, A.W.; Scoggins, M.; Williams, E.S. Coal-Tar-Based Pavement Sealcoat and PAHs: Implications for the Environment, Human Health, and Stormwater Management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3039–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.K.; Corsi, S.R.; Oliver, S.K.; Lenaker, P.L.; Nott, M.A.; Mills, M.A.; Norris, G.A.; Paatero, P. Primary Sources of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons to Streambed Sediment in Great Lakes Tributaries Using Multiple Lines of Evidence. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2020, 39, 1392–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Liu, J.; Shi, X.; You, X.; Cao, Z. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Water from Three Estuaries of China: Distribution, Seasonal Variations and Ecological Risk Assessment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2016, 109, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, R.-S.; Meng, X.-Z.; Xu, J.; Qadeer, A.; Liu, M. Modeling and Evaluating Spatial Variation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Urban Lake Surface Sediments in Shanghai. Environmental Pollution 2018, 235, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhou, S. Determination of Influencing Factors on Historical Concentration Variations of PAHs in West Taihu Lake, China. Environmental Pollution 2019, 249, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golobokova, L.; Khodzher, T.; Khuriganova, O.; Marinayte, I.; Onishchuk, N.; Rusanova, P.; Potemkin, V. Variability of Chemical Properties of the Atmospheric Aerosol above Lake Baikal during Large Wildfires in Siberia. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorshkov, A.G.; Izosimova, O.N.; Kustova, O.V.; Marinaite, I.I.; Galachyants, Y.P.; Sinyukovich, V.N.; Khodzher, T.V. Wildfires as a Source of PAHs in Surface Waters of Background Areas (Lake Baikal, Russia). Water 2021, 13, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Ya, M.; Li, Y.; Hong, H. Seasonal Variation and Spatial Transport of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water of the Subtropical Jiulong River Watershed and Estuary, Southeast China. Chemosphere 2019, 234, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, C.A.; Kronsbein, P.M.; Balik, B.; Schwarzbauer, J. Dynamic Transport and Distribution of Organic Pollutants in Water and Sediments of the Rur River. Water Air Soil Pollut 2023, 235, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dong, Z.; Baccolo, G.; Gao, W.; Li, Q.; Wei, T.; Qin, X. Distribution, Composition and Risk Assessment of PAHs and PCBs in Cryospheric Watersheds of the Eastern Tibetan Plateau. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 890, 164234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, X.; Hao, Y.; Cai, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, J. The Distribution, Sources and Health Risk of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Sediments of Liujiang River Basin: A Field Study in Typical Karstic River. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2023, 188, 114666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeniji, A.O.; Okoh, O.O.; Okoh, A.I. Levels of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Water and Sediment of Buffalo River Estuary, South Africa and Their Health Risk Assessment. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2019, 76, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leizou, K.E.; Ashraf, M.A. Distribution, Compositional Pattern and Potential to Human Exposure of PAHs in Water, Amassoma Axis, Nun River, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Acta Chemica Malaysia 2019, 3, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniji, A.O.; Okoh, O.O.; Okoh, A.I. Analytical Methods for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Their Global Trend of Distribution in Water and Sediment: A Review. In Recent Insights in Petroleum Science and Engineering; Zoveidavianpoor, M., Ed.; InTech, 2018 ISBN 978-953-51-3809-9.

- Umeh, C.T.; Nduka, J.K.; Omokpariola, D.O.; Morah, J.E.; Mmaduakor, C.; Okoye, N.H.; Lilian, E.-E.I.; Kalu, I.F. Ecological Pollution and Health Risk Monitoring Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Heavy Metals in Surface Water, Southeastern Nigeria. 2023, 38.

- Grmasha, R.A.; Abdulameer, M.H.; Stenger-Kovács, C.; Al-sareji, O.J.; Al-Gazali, Z.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Meiczinger, M.; Hashim, K.S. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Surface Water and Sediment along Euphrates River System: Occurrence, Sources, Ecological and Health Risk Assessment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2023, 187, 114568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Shi, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Fan, Z. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Riparian Soils of the Middle Reach of Huaihe River: A Typical Coal Mining Area in China. Soil and Sediment Contamination: An International Journal 2022, 0, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeham, S.G.; Canuel, E.A. Biogenic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments of the San Joaquin River in California (USA), and Current Paradigms on Their Formation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 2016, 23, 10426–10442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arowojolu, I.M.; Tongu, S.M.; Itodo, A.U.; Sodre, F.F.; Kyenge, B.A.; Nwankwo, R.C. Investigation of Sources, Ecological and Health Risks of Sedimentary Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in River Benue, Nigeria. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2021, 22, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Han, C.; Fang, H.; Weng, J.; Shu, X.; Pan, Y.; Ma, L. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Surface Waters from the Seven Main River Basins of China: Spatial Distribution, Source Apportionment, and Potential Risk Assessment. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 752, 141764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Gong, X.; Zhang, L.; Jin, M.; Cai, Y.; Wang, X. Riverine Transport and Water-Sediment Exchange of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) along the Middle-Lower Yangtze River, China. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 403, 123973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-C.; Chen, C.S.; Wang, Z.-X.; Tien, C.-J. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in 30 River Ecosystems, Taiwan: Sources, and Ecological and Human Health Risks. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 795, 148867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakizadeh, M. Spatial Distribution and Source Identification Together with Environmental Health Risk Assessment of PAHs along the Coastal Zones of the USA. Environ Geochem Health 2020, 42, 3333–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, M.M.; Sreeraj, M.K.; Rakesh, P.S.; Thomas, J.K.; Kharat, P.Y.; Sukumaran, S. Distribution, Source and Potential Biological Impacts of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Core Sediments of a Networked Aquatic System in the Northwest Coast of India – A Special Focus on Thane Creek Flamingo Sanctuary (Ramsar Site). Regional Studies in Marine Science 2024, 103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; He, B.; Wu, X.; Simonich, S.L.M.; Liu, H.; Fu, J.; Chen, A.; Liu, H.; Wang, Q. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Urban Stream Sediments of Suzhou Industrial Park, an Emerging Eco-Industrial Park in China: Occurrence, Sources and Potential Risk. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 214, 112095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Metre, P.C.; Mahler, B.J.; Qi, S.L.; Gellis, A.C.; Fuller, C.C.; Schmidt, T.S. Sediment Sources and Sealed-Pavement Area Drive Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon and Metal Occurrence in Urban Streams. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawrot, N.; Pouch, A.; Matej-Łukowicz, K.; Pazdro, K.; Mohsin, M.; Rezania, S.; Wojciechowska, E. A Multi-Criteria Approach to Investigate Spatial Distribution, Sources, and the Potential Toxicological Effect of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Sediments of Urban Retention Tanks. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 27895–27911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, P.R.S.; Moreira, L.F.F.; Moraes, E.P.; de Farias, M.F.; Domingos, Y.S. Traffic-Related Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Occurrence in a Tropical Environment. Environ Geochem Health 2021, 43, 4577–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, F.; Pradhan, A.; Abrantes, N.; Campos, I.; Keizer, J.J.; Cássio, F.; Pascoal, C. Wildfire Impacts on Freshwater Detrital Food Webs Depend on Runoff Load, Exposure Time and Burnt Forest Type. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 692, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieta, K.A.; Owens, P.N.; Petticrew, E.L.; French, T.D.; Koiter, A.J.; Rutherford, P.M. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Terrestrial and Aquatic Environments Following Wildfire: A Review. Environ. Rev. 2023, 31, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiari, N.; Charef, A.; Atoui, A.; Azouzi, R.; Khalil, N.; Khadhar, S. Southern Mediterranean Coast Pollution: Long-Term Assessment and Evolution of PAH Pollutants in Monastir Bay (Tunisia). Marine Pollution Bulletin 2021, 167, 112268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Hua, P.; Krebs, P. Global Trends and Drivers in Consumption- and Income-Based Emissions of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Association of Hydrogeologists Groundwater - More about the Hidden Resource. Available online: https://iah.org/education/general-public/groundwater-hidden-resource (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Li, P.; Karunanidhi, D.; Subramani, T.; Srinivasamoorthy, K. Sources and Consequences of Groundwater Contamination. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2021, 80, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, F.; Liu, Q. PAHs Behavior in Surface Water and Groundwater of the Yellow River Estuary: Evidence from Isotopes and Hydrochemistry. Chemosphere 2017, 178, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabali, Y.; Iaaly, A.; Millet, M. Environmental Occurrence, Spatial Distribution, and Source Identification of PAHs in Surface and Groundwater Samples of Abou Ali River-North Lebanon. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2021, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansilha, C.; Melo, A.; Martins, Z.E.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O.; Pereira, A.M.; Espinha Marques, J. Wildfire Effects on Groundwater Quality from Springs Connected to Small Public Supply Systems in a Peri-Urban Forest Area (Braga Region, NW Portugal). Water 2020, 12, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, P.; Nešković Markić, D.; Stojanović Bjelić, L. Evaluation of Sources and Ecological Risk of PAHs in Different Layers of Soil and Groundwater. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Sun, Y.; nueva, E. a sitio externo E. enlace se abrirá en una ventana; Yuan, D. Transport of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in a Highly Vulnerable Karst Underground River System of Southwest China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2018, 25, 34519–34530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Lan, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Long, Q.; Huang, M.; Yue, K. Linking PAHs Concentration, Risk to PAHs Source Shift in Soil and Water in Epikarst Spring Systems, Southwest China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2023, 264, 115465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, X.; Zheng, B.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Liu, Y. Influencing Factors and Health Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Groundwater in China. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 402, 123419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montuori, P.; De Rosa, E.; Cerino, P.; Pizzolante, A.; Nicodemo, F.; Gallo, A.; Rofrano, G.; De Vita, S.; Limone, A.; Triassi, M. Estimation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Groundwater from Campania Plain: Spatial Distribution, Source Attribution and Health Cancer Risk Evaluation. Toxics 2023, 11, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edet, A.; Nyong, E.; Ukpong, A.; Edet, C. Evaluation and Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Groundwater and Soil near a Petroleum Distribution Pipeline Spill Site, Eleme, Nigeria. Sustainable Water Resources Management 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, J.K. Wetland Assessment, Monitoring and Management in India Using Geospatial Techniques. Journal of Environmental Management 2015, 148, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyuela Leguizamo, M.A.; Fernández Gómez, W.D.; Sarmiento, M.C.G. Native Herbaceous Plant Species with Potential Use in Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals, Spotlight on Wetlands — A Review. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 1230–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashayeri, N.Y.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Kersten, M.; Yazdi, M.; Lahijanzadeh, A.R. Presence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments and Surface Water from Shadegan Wetland – Iran: A Focus on Source Apportionment, Human and Ecological Risk Assessment and Sediment-Water Exchange. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 148, 1054–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsch, W.J.; Gosselink, J.G. Wetlands; John Wiley & Sons, 2007; ISBN 978-0-471-69967-5.

- Sheikh Fakhradini, S.; Moore, F.; Keshavarzi, B.; Lahijanzadeh, A. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Water and Sediment of Hoor Al-Azim Wetland, Iran: A Focus on Source Apportionment, Environmental Risk Assessment, and Sediment-Water Partitioning. Environ Monit Assess 2019, 191, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanza, R.; de Groot, R.; Sutton, P.; van der Ploeg, S.; Anderson, S.J.; Kubiszewski, I.; Farber, S.; Turner, R.K. Changes in the Global Value of Ecosystem Services. Global Environmental Change 2014, 26, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, A.J.; Cooke, S.J.; Arthington, A.H.; Baigun, C.; Bossenbroek, L.; Dickens, C.; Harrison, I.; Kimirei, I.; Langhans, S.D.; Murchie, K.J.; et al. People Need Freshwater Biodiversity. WIREs Water 2023, 10, e1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettoof, D.C.; Bateman, P.W.; Aubret, F.; Gagnon, M.M. The Broad-Scale Analysis of Metals, Trace Elements, Organochlorine Pesticides and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Wetlands Along an Urban Gradient, and the Use of a High Trophic Snake as a Bioindicator. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2020, 78, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, H.; Tao, Y.; Kou, X.; He, C.; Wang, Z. Community Diversity of Soil Meso-Fauna Indicates the Impacts of Oil Exploitation on Wetlands. Ecological Indicators 2022, 144, 109451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasta, M.; Sattari, M.; Taleshi, M.S.; Namin, J.I. Identification and Distribution of Microplastics in the Sediments and Surface Waters of Anzali Wetland in the Southwest Caspian Sea, Northern Iran. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2020, 160, 111541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini-Birami, F.; Keshavarzi, B.; Esmaeili, H.R.; Moore, F.; Busquets, R.; Saemi-Komsari, M.; Zarei, M.; Zarandian, A. Microplastics in Aquatic Species of Anzali Wetland: An Important Freshwater Biodiversity Hotspot in Iran. Environmental Pollution 2023, 330, 121762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancheshmeh, R.A.; Bakhtiari, A.R.; Mortazavi, S.; Savabieasfahani, M. Sediment PAH: Contrasting Levels in the Caspian Sea and Anzali Wetland. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2014, 84, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cao, Z.; Lang, Y. Pollution Status of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Northeastern China: A Review and Metanalysis. Environ. Process. 2021, 8, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nas, B.; Argun, M.E.; Dolu, T.; Ateş, H.; Yel, E.; Koyuncu, S.; Dinç, S.; Kara, M. Occurrence, Loadings and Removal of EU-Priority Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Wastewater and Sludge by Advanced Biological Treatment, Stabilization Pond and Constructed Wetland. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 268, 110580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alikhani, S.; Nummi, P.; Ojala, A. Urban Wetlands: A Review on Ecological and Cultural Values. Water 2021, 13, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Xu, J.; Shang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xie, H.; Kong, Q.; Wang, Q. Application of Constructed Wetlands in the PAH Remediation of Surface Water: A Review. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 780, 146605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, J.; Xie, H.; Wu, H.; Jing, Y.; Ji, M.; Hu, Z. Transformation and Toxicity Dynamics of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in a Novel Biological-Constructed Wetland-Microalgal Wastewater Treatment Process. Water Research 2022, 223, 119023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Ren, G.; Ma, X.; Zhou, B.; Yuan, D.; Liu, H.; Wei, Z. Presence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons among Multi-Media in a Typical Constructed Wetland Located in the Coastal Industrial Zone, Tianjin, China: Occurrence Characteristics, Source Apportionment and Model Simulation. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 800, 149601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Xian, W.; He, G.; Xue, Z.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X. Occurrence and Spatiotemporal Distribution of PAHs and OPAHs in Urban Agricultural Soils from Guangzhou City, China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2023, 254, 114767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedevi, M.A.; Harikumar, P.S. Occurrence, Distribution, and Ecological Risk of Heavy Metals and Persistent Organic Pollutants (OCPs, PCBs, and PAHs) in Surface Sediments of the Ashtamudi Wetland, South-West Coast of India. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2023, 64, 103044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemanikharanagh, A.; Bakhtiari, A.R.; Mohammadi, J.; Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R. Toxicity and Origins of PAHs in Sediments of Shadegan Wetland, in Khuzestan Province, Iran. 2017, 15.

- Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Sheng, L.; Liu, X.; Zheng, X. Distribution Characteristics and Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Momoge Wetland, China. IJERPH 2017, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokhbar, M.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Zarei, M.; Hooda, P.S.; Risk, M.J. Occurrence and Source of PAHs in Miankaleh International Wetland in Iran. Chemosphere 2023, 321, 138140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Negi, R.; Jacob, M.; Gayathri, A.; Rokade, A.; Sarma, H.; Kalita, J.; Tasfia, S.T.; Bharti, R.; Wakid, A.; et al. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Aquatic Ecosystem Exposed to the 2020 Baghjan Oil Spill in Upper Assam, India: Short-Term Toxicity and Ecological Risk Assessment. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0293601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, K.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, G. A 200-Year Record of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Contamination in an Ombrotrophic Peatland in Great Hinggan Mountain, Northeast China. J. Mt. Sci. 2014, 11, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nim, N.; Morris, J.; Tekasakul, P.; Dejchanchaiwong, R. Fine and Ultrafine Particle Emission Factors and New Diagnostic Ratios of PAHs for Peat Swamp Forest Fires. Environmental Pollution 2023, 335, 122237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russkikh, I.V.; Strel’nikova, E.B.; Serebrennikova, O.V.; Voistinova, E.S.; Kharanzhevskaya, Yu.A. Identification of Hydrocarbons in the Waters of Raised Bogs in the Southern Taiga of Western Siberia. Geochem. Int. 2020, 58, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pelletier, R.; Noernberg, T.; Donner, M.W.; Grant-Weaver, I.; Martin, J.W.; Shotyk, W. Impact of the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfires on Atmospheric Deposition of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Trace Elements to Surrounding Ombrotrophic Bogs. Environment International 2022, 158, 106910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, T.M.; Uzarski, D.G. Marshes - Non-Wooded Wetlands. In Encyclopedia of Inland Waters; Likens, G.E., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2009; pp. 531–540. ISBN 978-0-12-370626-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhradini, S.S.; Moore, F.; Keshavarzi, B.; Lahijanzadeh, A. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Water and Sediment of Hoor Al-Azim Wetland, Iran: A Focus on Source Apportionment, Environmental Risk Assessment, and Sediment-Water Partitioning. Environ Monit Assess 2019, 191, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, N.A.; Al-Saad, H.T.; Al-Imarah, F.J. The Status of Pollution in the Southern Marshes of Iraq: A Short Review. In Southern Iraq’s Marshes: Their Environment and Conservation; Jawad, L.A., Ed.; Coastal Research Library; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 505–516. ISBN 978-3-030-66238-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.J.; Lyu, X.; Jiang, M.; Bhadha, J.; Wright, A. Impacts of Land Use Change on Soil Organic Matter Chemistry in the Everglades, Florida - a Characterization with Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Geoderma 2019, 338, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caumo, S.; Lázaro, W.L.; Sobreira Oliveira, E.; Beringui, K.; Gioda, A.; Massone, C.G.; Carreira, R.; de Freitas, D.S.; Ignacio, A.R.A.; Hacon, S. Human Risk Assessment of Ash Soil after 2020 Wildfires in Pantanal Biome (Brazil). Air Qual Atmos Health 2022, 15, 2239–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchal, L.; Gateuille, D.; Naffrechoux, E.; Deline, P.; Baudin, F.; Clément, J.-C.; Poulenard, J. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Dynamics in Soils along Proglacial Chronosequences in the Alps. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 902, 165998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, F.; Koziol, K.; Polkowska, Z. Chemical Hazard in Glacial Melt? The Glacial System as a Secondary Source of POPs (in the Northern Hemisphere). A Systematic Review. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 778, 145244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ademollo, N.; Spataro, F.; Rauseo, J.; Pescatore, T.; Fattorini, N.; Valsecchi, S.; Polesello, S.; Patrolecco, L. Occurrence, Distribution and Pollution Pattern of Legacy and Emerging Organic Pollutants in Surface Water of the Kongsfjorden (Svalbard, Norway): Environmental Contamination, Seasonal Trend and Climate Change. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2021, 163, 111900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Gao, H.; Ji, Z.; Jin, S.; Ge, L.; Zong, H.; Jiao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Na, G. Distribution and Sources of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Water Column of Kongsfjorden, Arctic. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2020, 97, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

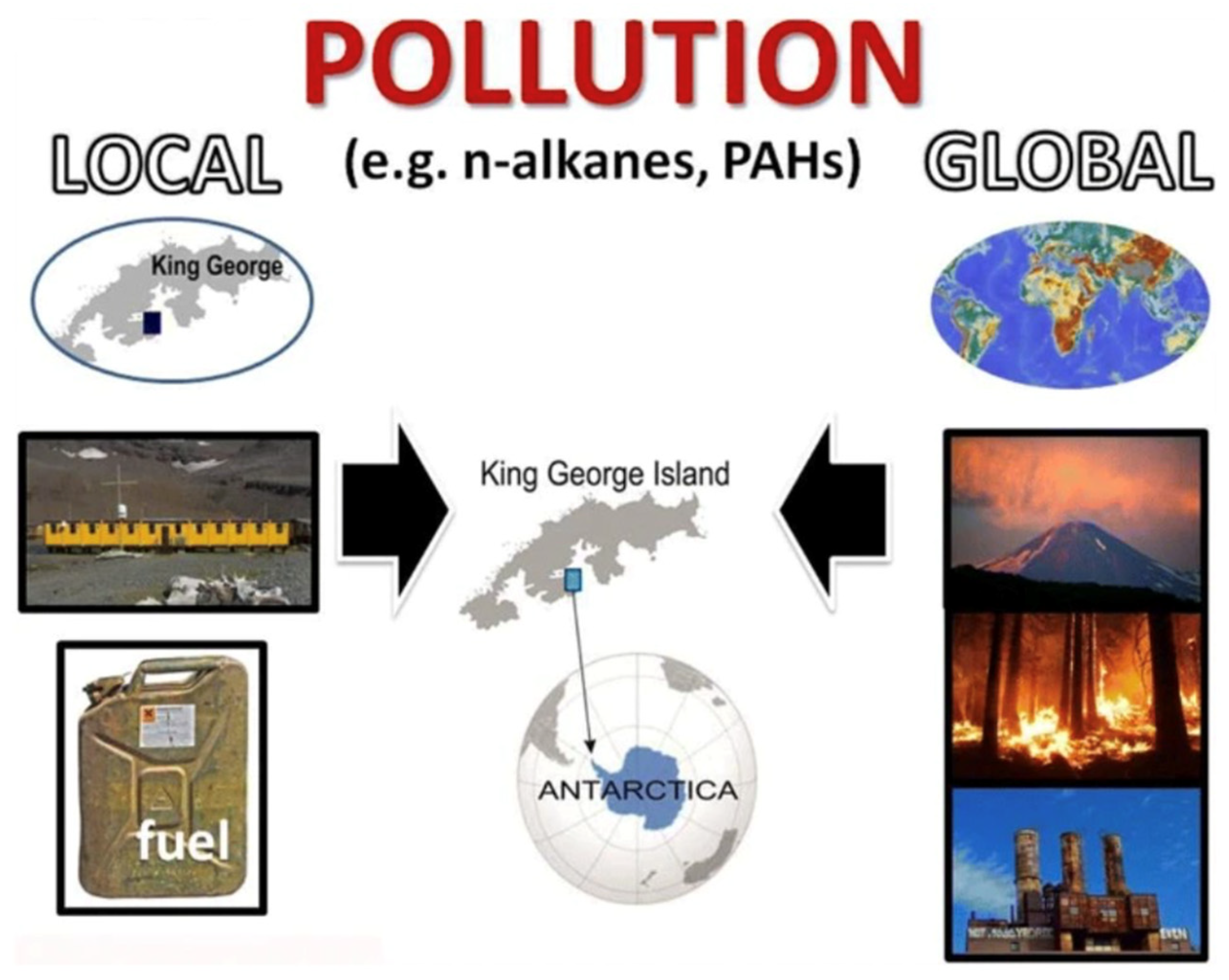

- Szopińska, M.; Szumińska, D.; Bialik, R.J.; Dymerski, T.; Rosenberg, E.; Polkowska, Ż. Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Other Organic Pollutants in Freshwaters on the Western Shore of Admiralty Bay (King George Island, Maritime Antarctica). Environ Sci Pollut Res 2019, 26, 18143–18161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deelaman, W.; Pongpiachan, S.; Tipmanee, D.; Suttinun, O.; Choochuay, C.; Iadtem, N.; Charoenkalunyuta, T.; Promdee, K. Source Apportionment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Terrestrial Soils of King George Island, Antarctica. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 2020, 104, 102832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongpiachan, S.; Hattayanone, M.; Tipmanee, D.; Suttinun, O.; Khumsup, C.; Kittikoon, I.; Hirunyatrakul, P. Chemical Characterization of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in 2013 Rayong Oil Spill-Affected Coastal Areas of Thailand. Environmental Pollution 2018, 233, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeh, C.T.; Nduka, J.K.; Omokpariola, D.O.; Morah, J.E.; Mmaduakor, E.C.; Okoye, N.H.; Lilian, E.-E.I.; Kalu, I.F. Ecological Pollution and Health Risk Monitoring Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Heavy Metals in Surface Water, Southeastern Nigeria. Environ Anal Health Toxicol 2023, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Xiong, J.; Qian, Z.; Xiong, S.; Zhao, R.; Liu, W.; et al. Distribution, Sources and Transport of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Karst Spring Systems from Western Hubei, Central China. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikanorov, A.M.; Reznikov, S.A.; Matveev, A.A.; Arakelyan, V.S. Monitoring of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Lake Baikal Basin in the Areas of Intensive Anthropogenic Impact. Russ. Meteorol. Hydrol. 2012, 37, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M.; Maier, D.; Lloyd, B.J. The Mobilisation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) from the Coal-Tar Lining of Water Pipes. Journal of Water Supply: Research and Technology—AQUA 1999, 48, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Nieto, E.; Sales, D.; Perales, J.A. Sources, Transport and Fate of PAHs in Sediments and Superficial Water of a Chronically Polluted Semi-Enclosed Body of Seawater: Linking of Compartments. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 2013, 15, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, A.; He, J.; Chen, S.; Huang, G. Distribution and Transport of PAHs in Soil Profiles of Different Water Irrigation Areas in Beijing, China. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 2014, 16, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nganje, T.N.; Neji, P.A.; Ibe, K.A.; Adamu, C.I.; Edet, A. Fate, Distribution and Sources of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Contaminated Soils in Parts of Calabar Metropolis, South Eastern Nigeria. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management 2014, 18, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Beek, T.A.D.; Schubert, M.; Yu, Z.; Schiedek, T.; Schüth, C. Sedimentary Archive of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Perylene Sources in the Northern Part of Taihu Lake, China. Environmental Pollution 2019, 246, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, T.; Prahl, F.G.; Simoneit, B.R.T. Suspended Particulate Matter Transport of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Lower C Olumbia River and Its Estuary. Limnology & Oceanography 2015, 60, 1935–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold-Bouchot, G.; Arcega-Cabrera, F.; Ceja-Moreno, V. Dissolved/Dispersed Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Spatial and Temporal Changes in the Western Gulf of Mexico. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 9, 1069315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Gao, S.; Zhu, L.; Jia, X.; Zeng, X.; Yu, Z. Occurrence and Source Apportionment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Soils and Sediment from Hanfeng Lake, Three Gorges, China. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 2017, 52, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dublet-Adli, G.; Cornelissen, G.; Eek, E.; Sørmo, E.; Hansen, C.B.; Tjønneland, M.V.; Maurice, C. A Trade-off in Activated Biochar Capping of Complex Sediment Contamination: Reduced PAH Transport at the Cost of Potential As Mobilisation. J Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaustov, A.; Redina, M. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Snow Cover of Moscow (Case Study of the RUDN University Campus). Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 2021, 41, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabodonirina, S.; Net, S.; Ouddane, B.; Merhaby, D.; Dumoulin, D.; Popescu, T.; Ravelonandro, P. Distribution of Persistent Organic Pollutants (PAHs, Me-PAHs, PCBs) in Dissolved, Particulate and Sedimentary Phases in Freshwater Systems. Environmental Pollution 2015, 206, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenov, M.Y.; Marinaite, I.I.; Zhuchenko, N.A.; Silaev, A.V.; Vershinin, K.E.; Semenov, Y.M. Revealing the Factors Affecting Occurrence and Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water and Sediments of Lake Baikal and Its Tributaries. Chemistry and Ecology 2018, 34, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.J.; Xu, H.Y.; Du, S.Y. Distribution and Numerical Prediction of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) on Atmospheric Particles in Jinan, China. AMR 2011, 183–185, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou DN; Liu M; Xu SY; Cheng SB; Hou LJ; Wang LL Distribution and Ecological Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Overlying Waters and Surface Sediments from the Yangtze Estuarine and Coastal Areas. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2009, 30, 3043–3049.

- Hattum, B.V.; Pons, M.J.C.; Montañés, J.F.C. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Freshwater Isopods and Field-Partitioning Between Abiotic Phases. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 1998, 35, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukarieh, B.; Hamieh, M.; Halloum, W.; Budzinski, H.; Jaber, F. The Effect of the Main Physicochemical Properties of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Their Water/Sediments Distribution. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 10261–10270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y. Parent and Alkylated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Surface Sediments of Mangrove Wetlands across Taiwan Strait, China: Characteristics, Sources and Ecological Risk Assessment. Chemosphere 2021, 265, 129168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

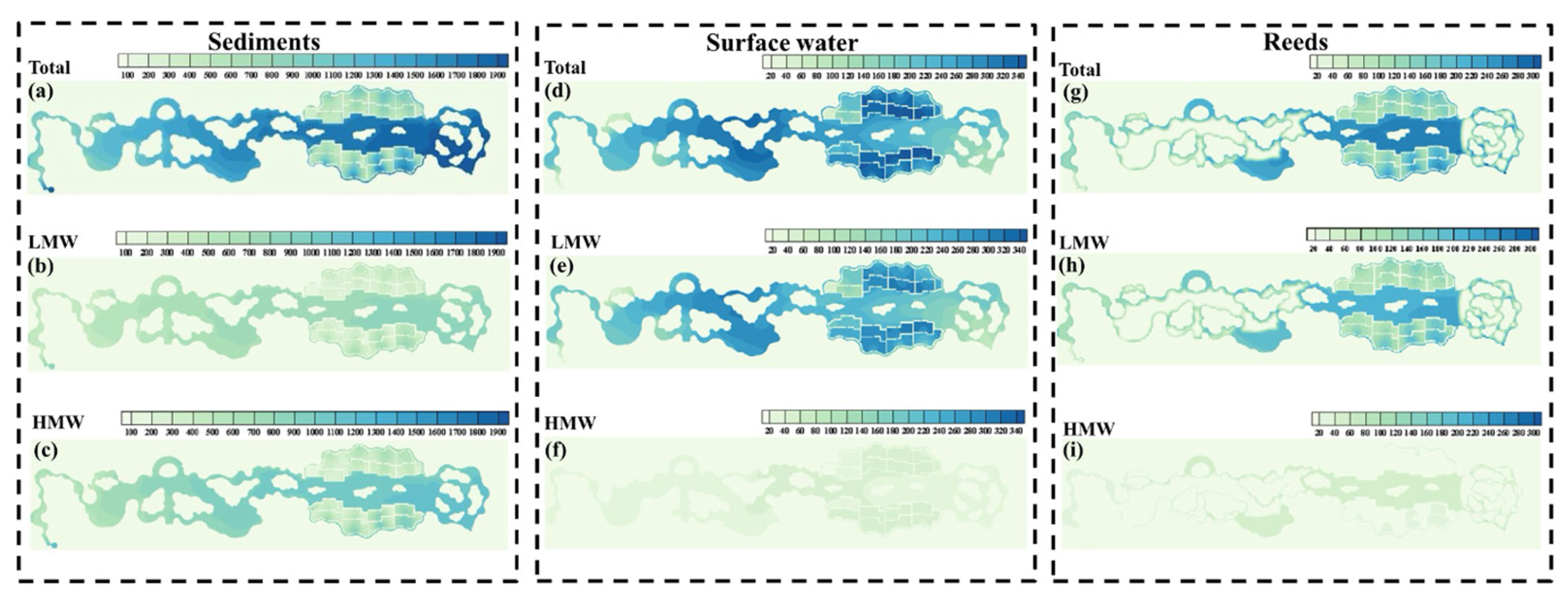

- Cai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cui, L.; Wang, J.; Zuo, X.; Lei, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhai, X.; Li, J.; Li, W. Distribution, Source Diagnostics, and Factors Influencing Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Yellow River Delta Wetland. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2023, 67, 103181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Qu, C.; Sun, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Qi, S. Multimedia Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Wang Lake Wetland, China. Environmental Pollution 2022, 306, 119358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.R.; Martins, C.C. A Systematic Evaluation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in South Atlantic Subtropical Mangrove Wetlands under a Coastal Zone Development Scenario. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 277, 111421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieta, K.A.; Owens, P.N.; Petticrew, E.L. Determination of Sediment Sources Following a Major Wildfire and Evaluation of the Use of Color Properties and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) as Tracers. J Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 4187–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephansen, D.A.; Arias, C.A.; Brix, H.; Fejerskov, M.L.; Nielsen, A.H. Relationship between Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments and Invertebrates of Natural and Artificial Stormwater Retention Ponds. Water 2020, 12, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, F.; Pereira, J.L.; Campos, I.; Santos, M.; Ré, A.; Keizer, J.; Nogueira, A.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Abrantes, N.; Serpa, D. A Review on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Distribution in Freshwater Ecosystems and Their Toxicity to Benthic Fauna. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 820, 153282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raudonytė-Svirbutavičienė, E.; Jokšas, K.; Stakėnienė, R.; Rybakovas, A.; Nalivaikienė, R.; Višinskienė, G.; Arbačiauskas, K. Pollution Patterns and Their Effects on Biota within Lotic and Lentic Freshwater Ecosystems: How Well Contamination and Response Indicators Correspond? Environmental Pollution 2023, 335, 122294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lécrivain, N.; Duparc, A.; Clément, B.; Naffrechoux, E.; Frossard, V. Tracking Sources and Transfer of Contamination According to Pollutants Variety at the Sediment-Biota Interface Using a Clam as Bioindicator in Peri-Alpine Lakes. Chemosphere 2020, 238, 124569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skic, K.; Boguta, P.; Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A.; Ukalska-Jaruga, A.; Baran, A. Effect of Sorption Properties on the Content, Ecotoxicity, and Bioaccumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Bottom Sediments. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 442, 130073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, R.O. Seasonal Variations of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Muscle Tissue of Silurus Triostegus Heckel, 1843 from Derbendikhan Reservoir. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 2023, 43, 2144–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdaini, Z.; Telahigue, K.; Hajji, T.; Rabeh, I.; Pharand, P.; El Cafsi, M.; Tremblay, R.; Gagné, J.P. Spatio-Temporal Distribution and Sources of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Tunis Lagoon: Concentrations in Sediments and Marphysa Sanguinea Body and Excrement. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2023, 189, 114769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.-M.; Hu, Y.-Y.; Yang, T.; Wu, N.; Wang, X.-N. Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress in Vascular-Related Diseases. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, C.E.; Knock, G.A. Control of Vascular Smooth Muscle Function by Src-family Kinases and Reactive Oxygen Species in Health and Disease. The Journal of Physiology 2015, 593, 3815–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrdina, A.I.H.; Kohale, I.N.; Kaushal, S.; Kelly, J.; Selin, N.E.; Engelward, B.P.; Kroll, J.H. The Parallel Transformations of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Body and in the Atmosphere. Environ Health Perspect 2022, 130, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Toxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Chronic Diseases and Aging. Arch Toxicol 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madamanchi, N.R.; Vendrov, A.; Runge, M.S. Oxidative Stress and Vascular Disease. ATVB 2005, 25, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda-Rivera, A.K.; Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Arancibia-Hernández, Y.L.; Hernández-Cruz, E.Y.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. RONS and Oxidative Stress: An Overview of Basic Concepts. Oxygen 2022, 2, 437–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ji, X.; Ding, F.; Wu, X.; Tang, N.; Wu, Q. Apoptosis and Blood-Testis Barrier Disruption during Male Reproductive Dysfunction Induced by PAHs of Different Molecular Weights. Environmental Pollution 2022, 300, 118959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Hu, X.; Yang, B.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y. Amino, Nitro, Chloro, Hydroxyl and Methyl Substitutions May Inhibit the Binding of PAHs with DNA. Environmental Pollution 2021, 268, 115798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Prasad, S.; Kishore, S.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, V. A Perspective Review on Impact and Molecular Mechanism of Environmental Carcinogens on Human Health. Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering Reviews 2021, 37, 178–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.K.; Essigmann, J.M. Establishing Linkages Among DNA Damage, Mutagenesis, and Genetic Diseases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1655–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Khan, R.; Bhattacharya, P.; Devanesan, S.; AlSalhi, M.S. Concentration, Source Apportionment and Potential Carcinogenic Risks of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Roadside Soils. Chemosphere 2022, 292, 133413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Suzuki, N. Toxicities of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons for Aquatic Animals. IJERPH 2020, 17, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pironti, C.; Ricciardi, M.; Proto, A.; Bianco, P.M.; Montano, L.; Motta, O. Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds: An Overview on Their Occurrence in the Aquatic Environment and Human Exposure. Water 2021, 13, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, A.; Ceccaldi, P.; Carbonnel, M.; Feki, A.; Ayoubi, J. Pollution and Endometriosis: A Deep Dive into the Environmental Impacts on Women’s Health. BJOG 2024, 131, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tq, D.; L, C.; A, I.; K, N.; M, M.; Ml, S. In Vitro Profiling of the Potential Endocrine Disrupting Activities Affecting Steroid and Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptors of Compounds and Mixtures Prevalent in Human Drinking Water Resources. Chemosphere 2020, 258, 127332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vondráček, J.; Machala, M. The Role of Metabolism in Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Their Non-Genotoxic Modes of Action. CDM 2021, 22, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlatt, V.L.; Bayen, S.; Castaneda-Cortès, D.; Delbès, G.; Grigorova, P.; Langlois, V.S.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Metcalfe, C.D.; Parent, L.; Rwigemera, A.; et al. Impacts of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals on Reproduction in Wildlife and Humans. Environmental Research 2022, 208, 112584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Net, S.; Henry, F.; Rabodonirina, S.; Diop, M.; Merhaby, D.; Mahfouz, C.; Amara, R.; Ouddane, B. Accumulation of PAHs, Me-PAHs, PCBs and Total Mercury in Sediments and Marine Species in Coastal Areas of Dakar, Senegal: Contamination Level and Impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2015, 9, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettoof, D.C.; Bateman, P.W.; Aubret, F.; Gagnon, M.M. The Broad-Scale Analysis of Metals, Trace Elements, Organochlorine Pesticides and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Wetlands Along an Urban Gradient, and the Use of a High Trophic Snake as a Bioindicator. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2020, 78, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Jahan, S.A.; Kabir, E.; Brown, R.J.C. A Review of Airborne Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Their Human Health Effects. Environment International 2013, 60, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukowska, B.; Mokra, K.; Michałowicz, J. Benzo[a]Pyrene—Environmental Occurrence, Human Exposure, and Mechanisms of Toxicity. IJMS 2022, 23, 6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.D.; Elanjickal, A.I.; Mankar, J.S.; Krupadam, R.J. Assessment of Cancer Risk of Microplastics Enriched with Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 398, 122994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozinovic, G.; Shea, D.; Feng, Z.; Hinton, D.; Sit, T.; Oleksiak, M.F. PAH-Pollution Effects on Sensitive and Resistant Embryos: Integrating Structure and Function with Gene Expression. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barron, M.G.; Vivian, D.N.; Heintz, R.A.; Yim, U.H. Long-Term Ecological Impacts from Oil Spills: Comparison of Exxon Valdez, Hebei Spirit, and Deepwater Horizon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6456–6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørhus, E.; Sørensen, L.; Grøsvik, B.E.; Le Goff, J.; Incardona, J.P.; Linbo, T.L.; Baldwin, D.H.; Karlsen, Ø.; Nordtug, T.; Hansen, B.H.; et al. Crude Oil Exposure of Early Life Stages of Atlantic Haddock Suggests Threshold Levels for Developmental Toxicity as Low as 0.1 Μg Total Polyaromatic Hydrocarbon (TPAH)/L. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2023, 190, 114843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekiguchi, T.; Honda, M.; Suzuki, N.; Mizoguchi, N.; Hano, T.; Takai, Y.; Oshima, Y.; Kawago, U.; Hatano, K.; Kitani, Y.; et al. Assessing the Influence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Aquatic Animals. In Field Work and Laboratory Experiments in Integrated Environmental Sciences; Hasebe, N., Honda, M., Fukushi, K., Nagao, S., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 87–104. ISBN 978-981-9965-31-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bramatti, I.; Matos, B.; Figueiredo, N.; Pousão-Ferreira, P.; Branco, V.; Martins, M. Interaction of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Compounds in Fish Primary Hepatocytes: From Molecular Mechanisms to Genotoxic Effects. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 855, 158783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, A.; Harris, K.J.; Archibong, A.E. Reproductive Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. In Reproductive and Developmental Toxicology; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 759–778 ISBN 978-0-323-89773-0.

- José, S.; Jordao, L. Exploring the Interaction between Microplastics, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Biofilms in Freshwater. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 2022, 42, 2210–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarano, L.; Zupo, V.; Guida, M.; Libralato, G.; Caramiello, D.; Ruocco, N.; Costantini, M. PAHs and PCBs Affect Functionally Intercorrelated Genes in the Sea Urchin Paracentrotus Lividus Embryos. IJMS 2021, 22, 12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Raverty, S.; Cottrell, P.; Zoveidadianpour, Z.; Cottrell, B.; Price, D.; Alava, J.J. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) Source Identification and a Maternal Transfer Case Study in Threatened Killer Whales (Orcinus Orca) of British Columbia, Canada. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 22580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, C.; Cai, G.; Li, S.; Nie, X.; Zhou, S. Assessing the Effects of Heavy Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Benthic Foraminifera: The Case of Houshui and Yangpu Bays, Hainan Island, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1123453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfeh, K.; Jacxsens, L.; Amoa-Awua, W.K.; Gamarro, E.G.; Ouadi, Y.D.; De Meulenaer, B. Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Smoked Sardinella Sp. in Ghana: Impact of an Improved Oven on Public Health Protection. Risk Analysis 2022, 42, 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, M.Y.; Marinaite, I.I.; Silaev, A.V.; Begunova, L.A. Composition, Concentration and Origin of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Waters and Bottom Sediments of Lake Baikal and Its Tributaries. Water 2023, 15, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.Q.; Guo, Y.N.; Zheng, S.J.; Liu, Q.S.; Zhang, J.L. Solid Phase Extraction of 16 Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons from Environmental Water Samples by π-Hole Bonds. Journal of Chromatography A 2021, 1645, 462067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, V.; Barkhordari, A.; Ghiasvand, A. Solid-Phase Microextraction Technique for Sampling and Preconcentration of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: A Review. Microchemical Journal 2020, 157, 104967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Dutta, R.; Das, P. A Critical Review on Plant Biomonitors for Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Air through Solvent Extraction Techniques. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Guijarro, P.A.; Álvarez-Vázquez, E.R.; Fernández-Espinosa, A.J. A Rapid Soxhlet and Mini-SPE Method for Analysis of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Atmospheric Particles. Anal Bioanal Chem 2021, 413, 2195–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termedashev, Z.A.; Volovik, S.P.; Korpakova, I.G.; Pavlenko, L.F.; Eletskiy, B.D. About the Nature of Origin of the Alkanes in the Productive Water Layer of the Open Regions of the East Part of the Black Sea. 2021, 25, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Pena, M.T.; Casais, M.C.; Mejuto, M.C.; Cela, R. Development of an Ionic Liquid Based Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction Method for the Analysis of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water Samples. Journal of Chromatography A 2009, 1216, 6356–6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, P.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M. Progress in the Analytical Research Methods of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs). Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies 2020, 43, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bu, Q.; Cao, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; He, X.; Yun, M. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Surface Water from Wuhai and Lingwu Sections of the Yellow River: Concentrations, Sources, and Ecological Risk. Journal of Chemistry 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soursou, V.; Campo, J.; Picó, Y. Revisiting the Analytical Determination of PAHs in Environmental Samples: An Update on Recent Advances. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry 2023, 37, e00195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistnes, H.; Sossalla, N.A.; Røsvik, A.; Gonzalez, S.V.; Zhang, J.; Meyn, T.; Asimakopoulos, A.G. The Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) with HPLC-DAD-FLD and GC-MS Techniques in the Dissolved and Particulate Phase of Road-Tunnel Wash Water: A Case Study for Cross-Array Comparisons and Applications. Toxics 2022, 10, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aygun, S.F.; Bagcevan, B. Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Drinking Water of Samsun and It’s Surrounding Areas, Turkey. J Environ Health Sci Engineer 2019, 17, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felemban, S.; Vazquez, P.; Moore, E. Future Trends for In Situ Monitoring of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water Sources: The Role of Immunosensing Techniques. Biosensors 2019, 9, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartore, D.M.; Vargas Medina, D.A.; Bocelli, M.D.; Jordan-Sinisterra, M.; Santos-Neto, Á.J.; Lanças, F.M. Modern Automated Microextraction Procedures for Bioanalytical, Environmental, and Food Analyses. J of Separation Science 2023, 46, 2300215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q. History of Organic Pollution in Montane Lake Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan, Central Asia, Inferred from a Sediment Core. Environmental Research 2024, 250, 118505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Yao, X.; Ding, Q.; Gong, X.; Wang, J.; Tahir, S.; Kimirei, I.A.; Zhang, L. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Organic Micropollutants (OMPs) Pollution and Prioritization in Equatorial Lakes from Mainland Tanzania, East Africa. Water Research 2022, 217, 118400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Li, Y.; Qian, B.; He, Y.; Peng, L.; Yu, H. Adsorption and Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water through the Aggregation of Graphene Oxide. Open Chemistry 2018, 16, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Bi, Z.; Shang, G. A Nanocomposite of Silver Nanoparticles and Porous G-C 3 N 4 for Recyclable SERS Detection of Trace Fluorene. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijunelyte, I.; Betelu, S.; Moreau, J.; Ignatiadis, I.; Berho, C.; Lidgi-Guigui, N.; Guénin, E.; David, C.; Vergnole, S.; Rinnert, E.; et al. Diazonium Salt-Based Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Nanosensor: Detection and Quantitation of Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water Samples. Sensors 2017, 17, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Ghaemi, F.; Maleki, B. Hybrid Nanocomposites Prepared from a Metal-Organic Framework of Type MOF-199(Cu) and Graphene or Fullerene as Sorbents for Dispersive Solid Phase Extraction of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Microchim Acta 2019, 186, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonani, S.; Ghiasvand, A. A Highly Porous Fiber Coating Based on a Zn-MOF/COF Hybrid Material for Solid-Phase Microextraction of PAHs in Soil. Talanta 2024, 267, 125236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atirah Mohd Nazir, N.; Raoov, M.; Mohamad, S. Spent Tea Leaves as an Adsorbent for Micro-Solid-Phase Extraction of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) from Water and Food Samples Prior to GC-FID Analysis. Microchemical Journal 2020, 159, 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretto, N.; Tedetti, M.; Guigue, C.; Mounier, S.; Redon, R.; Goutx, M. Identification and Quantification of Known Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Pesticides in Complex Mixtures Using Fluorescence Excitation–Emission Matrices and Parallel Factor Analysis. Chemosphere 2014, 107, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosental, M.; Coldman, R.N.; Moro, A.J.; Angurell, I.; Gomila, R.M.; Frontera, A.; Lima, J.C.; Rodríguez, L. Using Room Temperature Phosphorescence of Gold(I) Complexes for PAHs Sensing. Molecules 2021, 26, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Lu, D.-F.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Qi, Z.-M. Optofluidic Immunosensor Based on Resonant Wavelength Shift of a Hollow Core Fiber for Ultratrace Detection of Carcinogenic Benzo[a]Pyrene. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titaley, I.A.; Walden, D.M.; Dorn, S.E.; Ogba, O.M.; Massey Simonich, S.L.; Cheong, P.H.-Y. Evaluating Computational and Structural Approaches to Predict Transformation Products of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaii Babolghani, F.; Mohammadi-Manesh, E. Simulation and Experimental Study of FET Biosensor to Detect Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Applied Surface Science 2019, 488, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Ju, F.; Pan, H.; Tang, Z.; Ling, H. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the Interaction of Water and Humic Acid in the Adsorption of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020, 27, 25754–25765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, M.; Liao, Z.; Wang, L. Atmospheric Oxidation of Gaseous Anthracene and Phenanthrene Initiated by OH Radicals. Atmospheric Environment 2020, 234, 117587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA, Clean Water Act (CWA) and Federal Facilities. https://www.epa.gov/enforcement/clean-water-act-cwa-and-federal-facilities#:~:text=under%20the%20CWA.-,Application%20of%20CWA%20to%20Federal%20Facilities,Of%20dredged%20or%20fill%20material).

- EPA Safe Drinking Water Act. https://www.epa.gov/sdwa.

- Liefferink, D.; Wiering, M.; Uitenboogaart, Y. The EU Water Framework Directive: A Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Implementation and Domestic Impact. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaika, M. The Water Framework Directive: A New Directive for a Changing Social, Political and Economic European Framework. European Planning Studies 2003, 11, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, W.; Dulio, V.; Ågerstrand, M.; Allan, I.; Altenburger, R.; Brinkmann, M.; Bunke, D.; Burgess, R.M.; Cousins, I.; Escher, B.I.; et al. Towards the Review of the European Union Water Framework Directive: Recommendations for More Efficient Assessment and Management of Chemical Contamination in European Surface Water Resources. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 576, 720–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallis, G. The EU Water Framework Directive: Measures and Implications. Water Policy 2001, 3, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Taro; M. Takayuki; A. Mari Recent Contributions of the National Institute of Public Health to Drinking Water Quality Management in Japan. J. Natl. Inst. Public Health 2022, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Huang, C.-L.; Wang, J.-Z.; Ni, H.-G.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Bao, L.-J.; Zeng, E.Y. Significance of Anthropogenic Factors to Freely Dissolved Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Freshwater of China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 8304–8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. https://Semspub.Epa.Gov/Work/10/500015457.pdf.

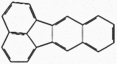

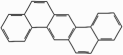

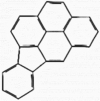

| No. | Name | CS(a) | Rings | Class.(b) | MW(c) | BP(d) | MP(e) | S(f) | Log Kow(g) | VP(h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Naphthalene |  |