1. Introduction

High bioavailability of persistent pollutants in marine environments raises serious concern regarding the health of aquatic organisms (1). They are more vulnerable to different sources of toxic chemicals (2), that are persistent in the environment and able to last for several years before breaking down (3). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are toxic, persistent and act as agents of endocrine disruption, mutagenicity and/or carcinogenicity (4). These organic compounds are composed of 2–7 fused aromatic rings with petrogenic, biogenic, and pyrogenic sources (5), and represent as much as 5% of crude oils (6). They directly affect marine ecosystems and come from activities, related to the oil and gas exploration, production, transportation, refining, and use (7), however, there also acute and long-term negative impacts of oils spill events.

All organisms, no matter their trophic level, are prone to “bioaccumulate” contaminants from the environment, through consumption of feed that contains them or by passive absorption of the compounds present in the water or sediment (8). The higher the level of contamination in an area, the more bioaccumulation is likely to occur. Organism animals higher (fishes) on the pyramid will consistently have much higher concentrations of persistent contaminants than lower trophic level species (mollusks and crustaceans). The major source of pollution in estuaries and coastal delta systems is sediment, because it becomes a sink for different organic and inorganic contaminants (9).

Seafood fatty tissues can accumulate PAHs and alkyl PAHs (10). To understand the fate of contaminants in aquatic food webs, it is essential to define key terms related to chemical accumulation. Bioaccumulation refers to the net uptake of a substance by an organism from all exposure routes, including direct uptake from water, ingestion of contaminated food, and contact with contaminated sediment. It represents the total accumulation of a chemical within an organism over its lifetime (11). The observed trophic dilution of lipophilic persistent organic pollutants (PAHs) is due to two key factors: low assimilation efficiencies and efficient metabolic transformation. Organisms, especially fish, have well-developed cytochrome P450 enzyme systems that efficiently convert PAHs into polar, water-soluble compounds (12). This results in lower Bioconcentration Factor Values (BCF) in their tissues. Conversely, mussels and lower invertebrates (mollusk and crustaceans) have limited capacity for PAH transformation, leading to higher accumulation of PAHs. Bivalve molluscs, like oysters, are particularly sensitive to lipophilic PAH bioaccumulation (13).

Thus, the pervasive nature of PAHs, their diverse toxicological effects on aquatic life, the complex dynamics of their trophic transfer, and the associated human health risks from seafood consumption underscore the urgent need for studies to assess and classify the PAH bioaccumulation on seafood. Our work assessed the level of contamination of the seafood before and after the Brazilian oil spill, and defined the risk associated with its consumption.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

A total of 37 analytes (PAHs, including alkyl PAHs) were selected for analysis in this study. The organic reagents, like n-hexane, dichloromethane (DCM), methanol (MeOH), acetonitrile (ACN), and methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), were all chromatographic grade; as well as, others chemicals and reagents used were also of high purity (>98%).

The standard PAH solution was obtained from Sigma Aldrich, Supelco (Saint Louis, USA), contained the following PAHs: naphthalene, acenaphthylene, acenaphthene, fluorene, phenanthrene, anthracene, fluoranthene, pyrene, benz(a)anthracene, chrysene, benzo(b)fluoranthene, benzo(k)fluoranthene, ben-zo(a)pyrene, dibenz(a,h)anthracene, benzo(g,h,i)perylene and indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene) and individual standards of each compound, benzo(j)fluoranthene and dibenzo(a,l)pyrene. In order to prevent volatilization and photodegradation, mixed standard solutions containing all PAHs were prepared by dilution of the stock solutions with acetonitrile (Sigma–Aldrich) and stored in darkness at -20°C. We obtained ultrapure water from a Milli-Q simplicity 185 system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA).

2.2. Sample Collection

Seafood samples were collected from Parnaiba Delta River on the Northeast of Brazil, during the rainy and dry seasons of 2019 (during the oil spill) and at the dry season in 2021 (after the oil spill), to evaluate the PAHs bioaccumulation. The wild seafood were caught with the help of local fishermen. In total, three species were collected, including shellfish (

Anomalocardia brasiliana) (F1, n = 40), mangrove crab (

Ucides cordatus) (F2, n = 25), mullet (

Mugil curema) (F3, n = 25). Samples were individually wrapped in aluminum foil, stored in polyethylene bags, and kept on ice during transportation. At the laboratory, the seafood were measured (

Table 1), processed and then stored at −20 °C before further analysis. Raw crab and shellfish specimens were carefully cleaned and opened for edible tissues extraction. Fishes were filleted for muscle separation.

2.3. Extraction and Quantitative Analysis

The PAHs extraction was carried out using the QuEChERS method. A deuterated PAH mixture (naphthalene-d8, acenaphthene-d10, phenanthrene-d10, chrysene-d12 and perylene-d12 homogenized) were added to the samples (2g wet weight, ww) as an internal standard (5 ng mL-1). The extraction used ultrapure water and a solution of acetone, ethyl acetate and isooctane (2:2:1), as well as MgSO4 and NaCl. A clean-up stage was performed to extract purification, using a deactivated alumina/silica column. A surrogate standard (p-terphenyl-d14) was used as an analytical control (5 ng mL-1). For injection into the GC/MS, the samples were filtered through a PTFE membrane filter (0.20 µm, Whatman®).

PAH quantification was conducted in accordance with the EPA8270-D protocol (14) using gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (Thermos Trace-ITQ instrument). In brief, 1 μL of each extract was injected into the equipment, which was equipped with a DB-5ms column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) and maintained a constant flow (1.2 mL min−1). The following temperature protocol was then applied: 50°C for 5 minutes, 50°C min−1 to 80°C, 6°C min−1 to 280°C for 25 minutes, and 12°C min−1 to 305°C for 10 minutes. The data acquisition was conducted in the selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode, with the typical PAH analysis ions (m/z) in mind (15). Quantification was conducted using 9-point calibration curve (1.0; 2.0; 5.0; 10.0; 20.0; 50.0; 100.0; 200.0 and 400.0 ng mL -1) that contained a mixture of 16 priority PAHs. Meanwhile, compounds that were not included in the mixture (alkylated homologs) were quantified by utilizing the response factor of homologs with similar structures (16). The limits of quantification for individual PAHs were 0.5 ng g−1 wet weight (ww) for the samples

2.4. Toxicity Equivalent Concentration (TEP)

Benzo(a)pyrene (BaP) exhibited the highest levels of carcinogenicity and toxicity among the seven carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). BaP is commonly employed to assess the carcinogenic potential of PAHs, with the toxic effect factor (TEF) serving as a metric for the carcinogenic capacity of each individual PAH in relation to BaP. The formula for calculating the equivalent concentration of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) using the toxic equivalent factor (17) is as follows:

where: PAHi represents the concentration of PAH monomer i, TEFi denotes the toxicity equivalent factor of PAH monomer i, TEQ signifies the toxicity equivalent of the compound’s equivalent concentration, and the TEF value for BaP is 1, the highest among all PAHs (

Table 2).

2.5. Carcinogenic Risks Assessment

The National Health Surveillance Agency (18) published the concern levels for evaluating the safety of seafood in Brazil after the 2019 oil disaster. The cancer risk for individual PAHs after seafood ingestion by humans was determined using the toxic equivalency (TEQ) approach in comparison to benzo[a]pyrene, as outlined in equation:

where: LOC is the concern level, RL is the acceptable risk level (1 x 10

-5), BW is the estimated average body weight of the exposed adult (60 kg), AT is the average life time of exposition (70 years), CF is the conversion factor (10

6 µg kg

-1), CSF is the cancer slope factor or carcinogenic potency relative to benzo[a]pyrene (BaPeq) (

Table 2), CR is the consumption rate of seafood, and ED is a estimated exposure duration (5 years). The CR for fish was set at 180 g day

−1and mollusks/crustaceans at 60 g day

−1. The values for individual PAH relative carcinogenic potencies and non-carcinogenic were taken from ICF-EPA (19) and (18), respectively.

2.6. Data Analysis

Means and standard deviations were calculated using Excel software. PCA, PLS, Normality test and ANOVA were performed using the PAST (Paleontological Statistics Software Package) (20).

3. Results

3.1. PAHs Profile

The PAH concentrations during (2019) and after (2021) the oil spill was analyzed in a total of 90 organisms (40 shellfish, 25 crustaceans, and 25 fishes). The sum of 37 PAH and alkylated compounds concentrations ranged from 22.39 ng g−1 ww in crab samples, to 445.69 ng g−1 ww in shellfish samples, with a global average of 199.90 ± 175.71 ng g−1 ww, on dry season of 2019. For crabs and fishes, the lowest ΣPAH values were detected during the oil spill (Iin 2019), while for shellfish, the lowest values were detected two years after the accident (in 2021).

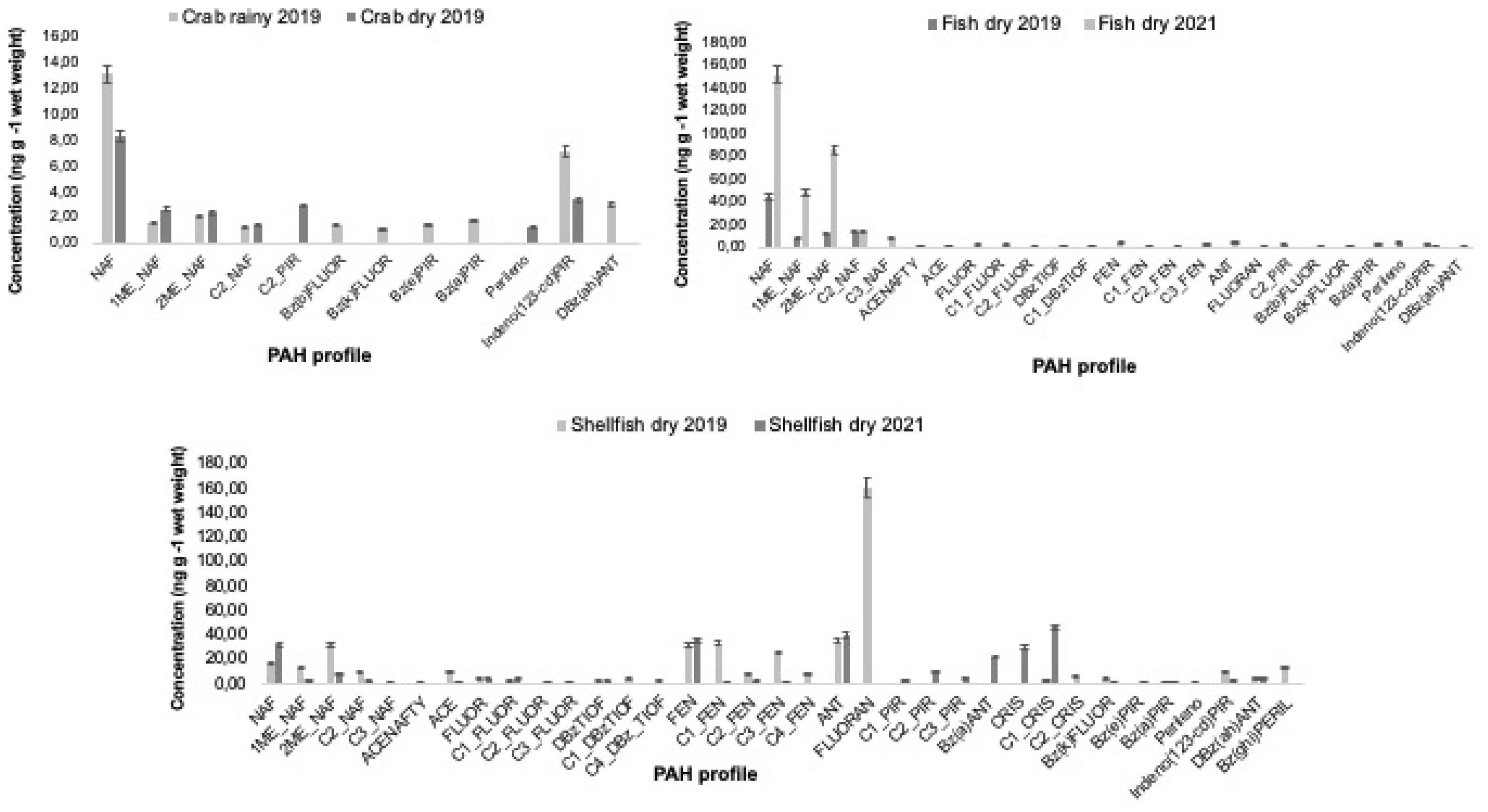

The PAH profile was different for each species. For crab, 12 PAHs were detected and quantified, for fish, 25 PAHs, and for shellfish, 35 PAHs (

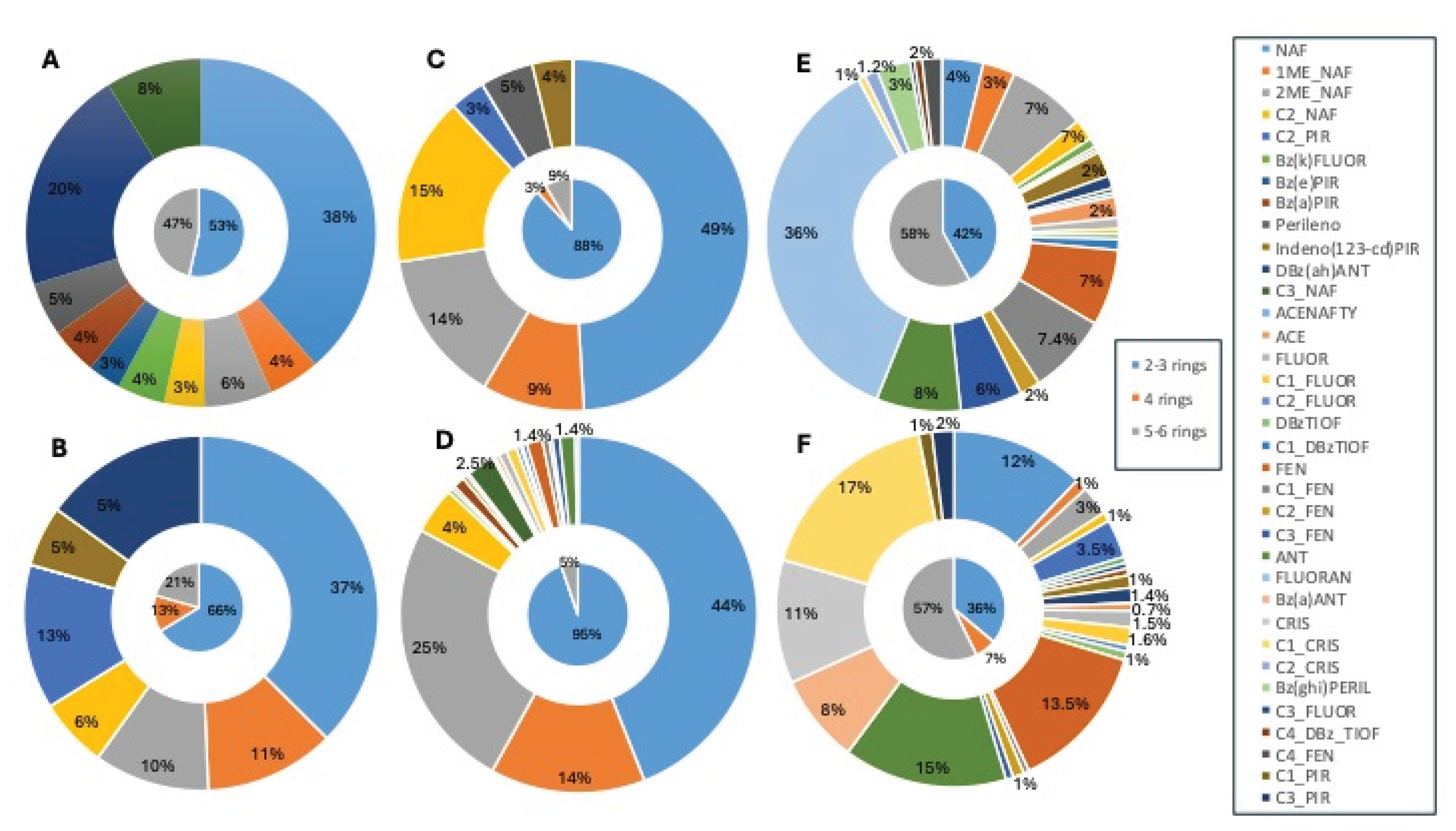

Figure 1). Low molecular weight (LMW) compounds, classified with 2-3 rings, particularly naphthalene and its alkylated homologs, were prevalent in fish samples. For shellfish and crab from rainy season, there was a equality distribution between LMW and high molecular weight (with 5-6 rings) PAHs in the samples. Medium molecular weight (4 rings, MMW) PAHs were representative (13.20%) only in crab samples from dry season (

Figure 2).

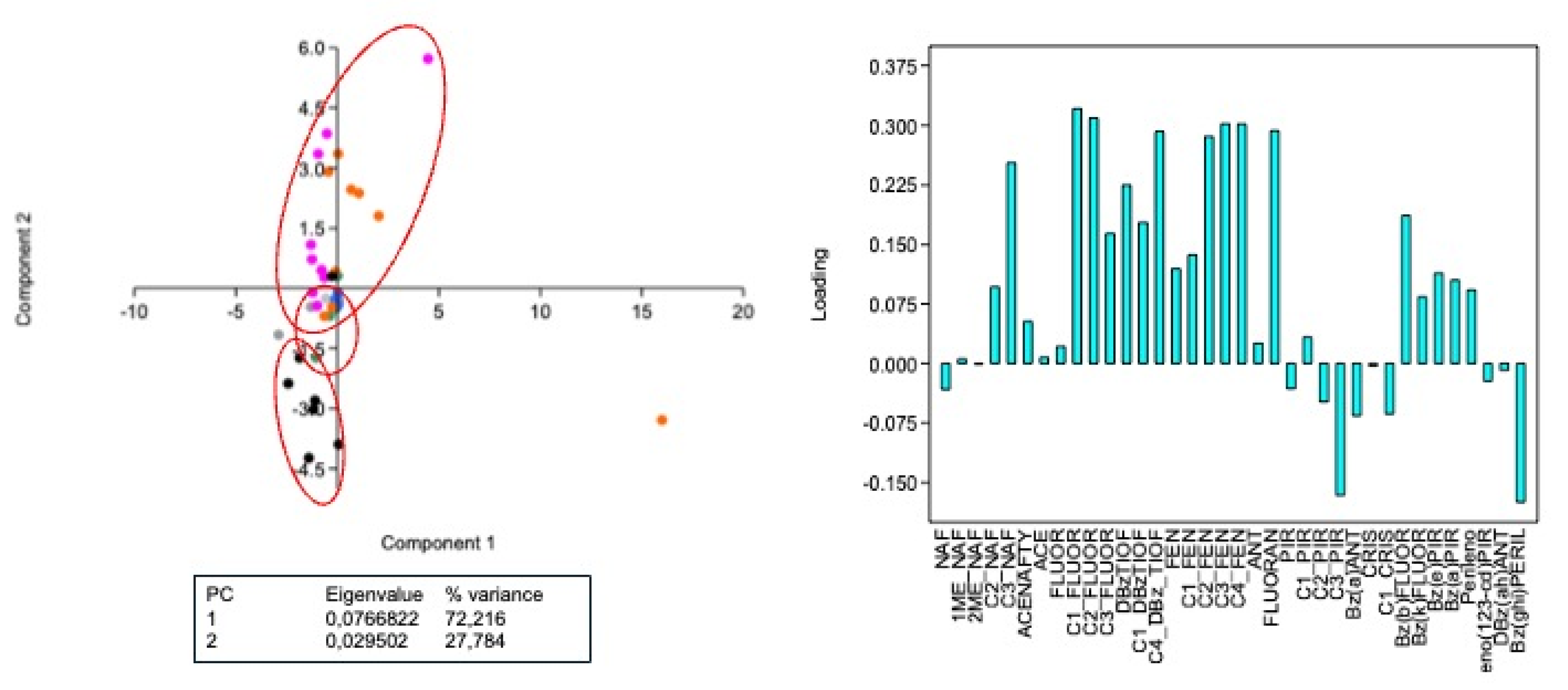

PCA analysis segregated three groups (

Figure 3). A well-defined group formed by fishes, with a predominance of 88% of LMW PAHs; a second group formed by crabs that presented similar proportions between low and high molecular weight PAHs; and finally the group of shellfishes, which presented a great diversity of PAHs (35 compounds of the 37 monitored), with a small intersection that demonstrated similarity in some PAHs found in the crab samples. The PLS (Partial Least Squares) analysis identified which PAHs were important for the model tested. It was noted that LMW and HMW PAHs were responsible for the differentiation between the samples, while medium molecular weight PAHs (pyrenes) were not significant, as well as NAF and Bz(ghi)Perilene (

Figure 3).

3.2. PAHs Source Analysis

The feature ratio method is frequently employed to determine the source of PAHs in the environment: LMW/HMW > 1 represents the crude oil source, and LMW/HMW < 1 represents high-temperature pyrolysis and/or combustion source (21). The LMW/HMW ration for crab and fish was higher than 1, demonstrate an oil spill contamination in 2019, and 2021 for fishes. For shellfish, the same.

3.3. Bioaccumulation of PAHs

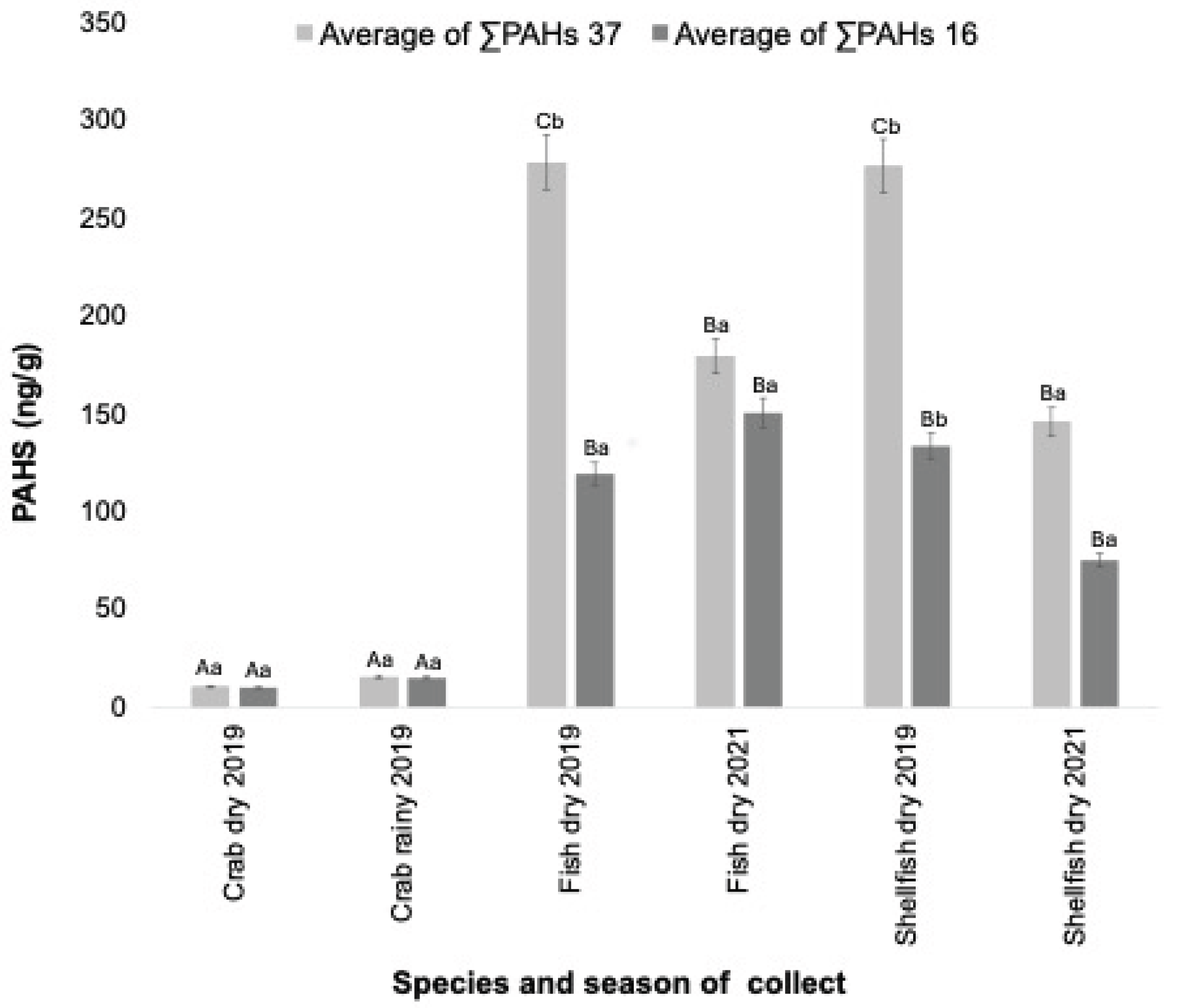

Bioaccumulation was assessed by the ΣPAHs (16 priority and 37 more compounds) determined in each species. The effect of contamination varied among the species studied. Crabs, a species that feeds on organic matter in mangrove areas, had the lowest contamination rate compared to the other species studied (p<0.05). Fish and shellfish showed similar levels of contamination, despite having distinct feeding habits (omnivorous fish and filter-feeding shellfish) (p>0.05) (

Figure 4).

Regarding contamination over time (before and after the oil spill), there was no difference between the rainy and dry seasons of 2019 for crabs (p>0.05). For fishes, higher contamination of ΣPAHs 16, considered to have the greatest carcinogenic potential, was detected in 2019, with a reduction in the contamination level in 2021 (p<0.05). For ΣPAHs 37, there was no change during the monitoring period for fish (p>0.05). Shellfish showed the highest contamination level in 2019, during the oil spill, and the lowest level in 2021, for both parameters used (ΣPAHs 16 and ΣPAHs 37) (

Figure 4). In summary, crabs were less affected by the oil spill, while fish and shellfish were contaminated, showing levels of PAHs even two years after the accident.

3.4. Risk Assessment

The Toxicity equivalent concentration (TEF,

Table 3) was used for levels of concern calculations for non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic PAHs in the samples (

Table 4). The concentrations of non-carcinogenic PAHs in the analyzed samples were significantly lower than the concern thresholds established for oil spill incidents in Brazil (18) (

Table 4).

Fish samples collected in 2021 exhibited fluoranthene values near the limit of concern set by Brazilian legislation. Similar results were noted for specific carcinogenic and mutagenic PAHs in crabs, fish, and shellfish (

Table 4). Indeno [1,2,3-cd]pyrene concentrations exceeded the concern threshold (> 5 ng g

−1 ww) established by Brazilian authorities in all samples, except for the analyzed crab. Fish samples from 2019 and 2021 contained 41 ng g

−1 ww and 104 ng g

−1 ww of indeno [1,2,3-cd]pyrene, respectively. Shellfish samples collected in 2019 and 2021 contained 14 ng g

−1 ww and 47 ng g

−1 ww, respectively. Fish were also above the acceptable limit for benzo[b]fluoranthene (BbF) (100 ng g

−1 ww) and benzo[k]fluoranthene (BkF) (145 ng g

−1 ww). The only sample that was above the limit for benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) (8 ng g

−1 ww) was the shellfish collected in 2021 (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

This study provides a critical assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) contamination in seafood from the Parnaiba Delta River following the 2019 oil spill in Brazil, offering valuable insights into the differential bioaccumulation and long-term residual effects of the incident. The findings successfully demonstrate a clear, acute contamination effect during the oil spill in 2019, followed by a persistent residual contamination two years later in 2021, with significant differences in the PAH profiles among species.

The observed variability in PAH concentrations and bioaccumulation across the different species—crab, fish, and shellfish—is a key finding that reflects their distinct physiological and ecological characteristics. As filter-feeders, shellfish had the highest overall PAH concentrations in 2019, followed by a significant reduction in 2021. This aligns with findings from other studies, which consistently show that bivalve mollusks, as sessile organisms with filter-feeding habits, are particularly susceptible to PAH bioaccumulation and have a limited capacity for metabolizing these compounds (22). In contrast, fish, which are at a higher trophic level, showed similar contamination levels to shellfish. This might seem counterintuitive, as higher-trophic-level organisms are expected to have higher concentrations of persistent contaminants due to biomagnification. However, this study’s data supports the existing knowledge that fish possess well-developed enzyme systems, such as cytochrome P450, that efficiently metabolize and excrete PAHs, resulting in lower bioconcentration factors (BCF) in their tissues (23). The fact that fish still showed high levels of contamination, especially in 2019, indicates the severity of the initial spill, overwhelming their metabolic detoxification systems. The relatively low contamination observed in crabs, which feed on organic matter in mangrove areas, suggests a different exposure dynamic, possibly related to their habitat or feeding habits compared to the open-water fish and sediment-dwelling shellfish. Research indicates that crustaceans have a moderate ability to remove PAHs from their bodies compared to fish and bivalve mollusks. Crustaceans can metabolize PAHs, converting them into more water-soluble forms like 1-OH pyrene for excretion in urine, but this process is not always highly efficient (24).

The analysis of PAH profiles provides crucial information regarding the sources of contamination over time. The LMW/HMW ratio is a widely accepted method to differentiate sources, with LMW PAHs typically originating from crude oil (petrogenic sources) and HMW PAHs from high-temperature pyrolysis or combustion (pyrogenic sources) (21). The predominance of LMW PAHs in fish samples from 2019 and 2021 clearly points to a persistent petrogenic source, consistent with the oil spill. This indicates an acute effect of the contamination event. Conversely, shellfish showed a different profile, with a great diversity of PAHs and a more even distribution between LMW and HMW compounds in 2019, and a shift towards HMW PAHs in 2021. This finding is significant, as it suggests a residual effect of contamination associated with pyrogenic sources, such as combustion and anthropogenic activities, which became more prominent after the initial crude oil contamination subsided. The mixed PAH profile in crabs, with similar proportions of LMW and HMW compounds, further underscores the complexity of PAH sources in this coastal environment, which is subject to both acute spill events and chronic pollution from other anthropogenic activities. The persistence of PAHs is also linked to their low solubility and high persistence, allowing them to remain in the environment and pose a long-term chronic risk (25). Global studies show varying PAH concentrations in edible seafood tissues, with high molecular weight PAHs (HMW-PAHs) predominant over low molecular weight PAHs (LMW-PAHs) in commonly consumed species like Littorina littorea, Crassostrea virginica, and Periophthalmus koeleuteri. This suggests a predominant anthropogenic and pyrolytic origin for the detected PAHs (26). South Korea’s katsuobushi, a skipjack tuna product, contains high levels of benzo[a]pyrene, exceeding the EU limit of 5.0 µg/kg. Shellfish, fish, and crustacea have the highest detection rates for PAHs, with chrysene being the most prominent congener (27). In Nigeria, PAH levels range from 0.059 to 0.126 mg/kg in fish, prawn, and crab. This study also noted a significant predominance of 3- and 4-ring PAHs, with benzo[a]anthracene being particularly prevalent across all three species (28).

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in marine and aquatic food webs are complex processes that involve uptake from various environmental sources, absorption from the diet, and the organism’s ability to metabolize and excrete these compounds. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for accurately assessing ecological and human health risks. Bioaccumulation is the net uptake of a substance by an organism from all its exposure routes, including water, air, sediment, and food (29). Organisms at the base of the food chain, such as filter-feeding bivalves like oysters and mussels, are highly susceptible to bioaccumulation (30). Biomagnification is the increase in concentration of a substance in an organism as it consumes prey at a lower trophic level, characteristic of compounds that are highly resistant to degradation, fat-soluble (lipophilic), and not easily excreted (31). PAHs, particularly high-molecular-weight (HMW) compounds, are highly lipophilic and have the potential to biomagnify (32). The physicochemical properties of PAHs, such as lipophilicity and molecular weight, play a significant role in their behavior in the environment and within organisms. PAHs enter the aquatic food web at the lowest trophic levels, with primary producers such as phytoplankton and algae absorbing PAHs from the water column, while primary consumers like zooplankton and filter-feeders accumulate PAHs from both the dissolved phase and particles (33). The concentration of PAHs in organisms at higher trophic levels, such as fish, is more variable and complex due to their efficient metabolic detoxification systems. Fish possess a highly developed mixed-function oxygenase (MFO) system, which metabolizes PAHs into more water-soluble derivatives, leading to lower PAH concentrations in their muscle tissue (34). Case studies have shown a significant negative relationship between PAH concentrations and the trophic levels of organisms, with the highest concentrations in lower trophic level organisms. Filter-feeders, which lack the advanced metabolic capacity of vertebrates, are ideal bioindicators for monitoring environmental contamination (35). Key factors influencing trophic transfer include metabolic capacity, diet and exposure pathway, lipid content, and PAH type. Thus, the bioaccumulation of PAHs in marine food webs is a complex interaction influenced by the unique properties of different PAH compounds, primary exposure pathways, and diverse metabolic capabilities of organisms at each trophic level (36). The resulting pattern is often a mix of bioaccumulation, biomagnification, and trophic dilution, which must be considered when assessing risks associated with PAH contamination in seafood.

The most critical finding of this study relates to the human health risks associated with consuming the contaminated seafood. The analysis against ANVISA’s concern levels reveals that despite a decrease in overall PAH concentrations, certain carcinogenic PAHs remained at levels that exceeded legal limits. All fish and shellfish samples contained indeno [1,2,3-cd]pyrene concentrations above the established concern threshold. Furthermore, fish samples also exceeded the acceptable limits for benzo[b]fluoranthene and benzo[k]fluoranthene. Most alarmingly, shellfish collected in 2021, two years after the oil spill, were the only samples to present contamination above the acceptable limit for benzo[a]pyrene (BaP). This highlights that even with the visible signs of the oil spill gone, a residual public health risk persists, especially from the accumulation of these highly carcinogenic compounds. These findings align with and build upon global research on PAH contamination in seafood. A study in South Korea, for instance, also found elevated levels of benzo[a]pyrene in marine products, emphasizing the widespread nature of this particular health concern (27). The prevalence of carcinogenic PAHs from pyrogenic sources suggests that continuous monitoring is essential, as these compounds are known to be particularly persistent and toxic.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this research successfully demonstrates the acute impact of the 2019 oil spill on the marine ecosystem of the Parnaiba Delta River, highlighting the differential bioaccumulation of PAHs in fish, crabs, and shellfish. The study also reveals a significant, residual public health risk from the lingering contamination of carcinogenic PAHs two years after the event. The persistence of these compounds, even after the acute phase of the spill, underscores the critical need for long-term environmental monitoring and robust regulatory frameworks to protect seafood safety and public health in coastal areas vulnerable to both acute and chronic pollution events. Future research should focus on continuous monitoring to track the long-term fate and effects of these PAHs. Investigating the specific metabolic pathways and bioavailability of different PAH compounds in a wider range of marine species would also be crucial to better understand and model the risks to both aquatic life and human consumers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Fogaça; Formal analysis, Melo, Massone, Carreira and Fogaça; Funding acquisition, Torres; Investigation, Fogaça and Melo; Project administration, Torres; Supervision, Ramos and Torres; Writing—original draft, Fogaça; Writing—review and editing, Fogaça, Melo and Torres. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Capes (Process 009/2020).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.D.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akhbarizadeh, R.; Moore, F.; Keshavarzi, B. Investigating microplastics bioaccumulation and biomagnification in seafood from the Persian Gulf: A threat to human health? Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 2019, 36, 1696–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, M.; Zanghì, G.; Cristaldi, A.; Copat, C.; Grasso, A.; Fiore, M.; Signorelli, S.S.; Zuccarello, P.; Conti, G.O. PAHs in seafood from the Mediterranean Sea: An exposure risk assessment. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2018, 115, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP/GPA. The state of Marine Environment: Trends and processes. UNEP/GPA, 2006. (accessed on 20/08/25). Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/675041?v=pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- IARC. Some non-heterocyclic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and some related exposures. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans 2010, 1, 773. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xia, K.; Waigi, M.G.; Gao, Y.; Odinga, E.S.; Ling, W.; Liu, J. Application of biochar to soils may result in plant contamination and human cancer risk due to exposure of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, 2018, 121, Part 1, 169-177. Environment International 2018, 121 Pt 1, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodson, P.V. The toxicity to fish embryos of PAH in crude and refined oils. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2017, 73, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. Oil in the Sea: Inputs, fates and effects, 2nd ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, USA, 2003; Volume 1, p. 25057607. [Google Scholar]

- Windsor, F.M.; Pereira, M.G.; Tyler, C.R.; Ormerod, S.J. Biological traits and the transfer of persistent organic pollutants through river food webs. Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53, 13246–13256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslen, M.; Miebaka, C.A. Temporal variation of heavy metal concentrations in species obtained from Azuabie Creek in the Upper Bonny Estuary, Nigeria. Current Studies in Comparative Education, Science and Technology 2016, 3, 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Nakken, C.L.; Sørhus, E.; Holmelid, B.; Meier, S.; Mjøs, S.A.; Donald, C.E. Transformative knowledge of polar polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons via high-resolution mass spectrometry. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 960, 178349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleeker, E.M.; Verbruggen, J. Bioaccumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in aquatic organisms. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/601779002.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Larsen, T.; Ventura, M.; Andersen, N.; O’Brien, D.M.; Piatkowski, U. Tracing carbon sources through aquatic and terrestrial food webs using amino acid stable isotope fingerprinting. PLoS ONE 2014, 8(9), e73441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, M.O. Biotransformation and Disposition of PAH in Aquatic Invertebrates. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387018961_Biotransformation_and_Disposition_of_PAH_in_Aquatic_Invertebrates/citation/download (accessed on day month year).

- EPA. Method 8270D: Semivolatile organic compounds by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, 2014, 16 p. Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/epa/sites/production/files/2015-12/documents/8270d.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- Mauad, C.R.; Wagener, A.L.R.; Massone, C.G.; Aniceto, M.S.; Lazzari, L.; Carreira, R.S.; Farias, C.O. Urban rivers as conveyors of hydrocarbons to sediments of estuarine areas: Source characterization, flow rates and mass accumulation. Science of The Total Environment 2015, 506–507, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, K.M.; Carreira, R.S.; Rosa Filho, J.S.; Rocha, P.P.; Santana, F.M.; Yogui, G.T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in fishery resources affected by the 2019 oil spill in Brazil: Short-term environmental health and seafood safety. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2022, 175, 113334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-J.; Shih, T.-S.; Chen, H.-L.; Lee, W.-J.; Lai, C.-H.; Liou, S-H. Assessing and predicting the exposures of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their carcinogenic potencies from vehicle engine exhausts to highway toll station workers. Atmospheric Environment 2004, 38, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANVISA. Riscos a saúde humana decorrentes do consumo de pescados oriundos das praias contaminadas por óleo cru na Região Nordeste do Brasil, Nota Técnica n. 27/2019/SEI/GGALI/DIRE2/ANVISA, 2019, 5p. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília, DF, Brazil. Available online: https://portalcievs.saude.pe.gov.br/docs/SEI_ANVISA_-_0815698_-_Nota_T%C3%A9cnica_GGALI.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- Yender, R.; Michel, J.; Lord, C. Managing Seafood Safety After an Oil Spill; Hazardous Materials Response Division, Office of Response and Restoration, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Seattle, USA,, 2002; 72p. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 2001, 4(1), 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.-Y.; Li, Y.-X.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Zhang, T.; Liu, G.-H.; Huang, M.-Z.; Li, X.; Ruan, J.-J.; Kannan, K.; Qiu, R-L. Associations between polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) exposure and oxidative stress in people living near e-waste recycling facilities in China. Environment International 2016, 94, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Esteso, C.; Roselló-Carrió, A.; Carrasco-Correa, E.J.; Lerma-García, M.J. Bioaccumulation of environmental pollutants and marine toxins in bivalve molluscs: A review. Explor Foods Foodomics 2024, 2, 788–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves, R.; Colás-Ruiz, M.G.; Pintado-Herrera, M.S.; Salerno, B.; Tonini, F.; Lara-Martín, P.A.; Hampel, M. Bioconcentration, biotransformation, and transcriptomic impact of the UV-filter 4-MBC in the manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 912, 169178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, R.A.; Francioni, E.; Silva, A.H.M.F.T.; Magalhães, C.A.; Gallotta, F.D.C.; Oliveira, F.F.; Souza, J.M.; Araújo, L.F.M.; Araújo, L.P.; Araújo Júnior, M.A.G.; Meniconi, M.F.G.; Lopes, M.A.F.S.B.G. Bioaccumulation study of produced water discharges from Southeastern Brazilian offshore petroleum industry using feral fishes. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2018, 74, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, W. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): Environmental persistence and human health risks. Natural Product Communications 2025, 20(1), e1934578X241311451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaichi, E.O.; Ntorgbo, S.A. Assessment of PAHs levels in some fish and seafood from different coastal waters in the Niger Delta. Toxicol Rep 2016, 13, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paik, Y.; Kim, H.S.; Joo, Y.S.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, K.W. Evaluation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contents in marine products in South Korea and risk assessment using the total diet study. Food Sci Biotechnol 2024, 2024 33, 2377–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, R.; Yang, X.; Su, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Levels, sources and probabilistic health risks of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the agricultural soils from sites neighboring suburban industries in Shanghai. Sci Total Environ 2018, 616, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoca, D.; Pace, A. Bioaccumulation, Biodistribution, Toxicology and Biomonitoring of Organofluorine Compounds in Aquatic Organisms. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, N.; Martin, L.; Xu, W. Impact of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Accumulation on Oyster Health. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 734463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, Z. Multi-cascade physiologically based kinetic (PBK) matrix model: Simulating chemical bioaccumulation across food webs. Environment International 2025, 198, 109376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, I.; Abdel-Shafy, M.; Mansour, S.M. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum 2016, 25, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouch, A.; Zaborska, A.; Dabrowska, A.M.; Pazdro, K. Bioaccumulation of PCBs, HCB and PAHs in the summer plankton from West Spitsbergen fjords Mar. Pollut Bull 2022, 177, 113488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomann, R.V.; Komlos, J. Model of biota-sediment accumulation factor for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ Toxicol Chem Int J 1999, 18, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, B.; Wan, Y.; Jin, X.; Hu, J.; Jin, F. Trophic dilution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a marine food web from North China. Environmen Sci Techn 2007, 41, 3109–3114. [Google Scholar]

- Meador, J.P.; Stein, J.E.; Reichert, W.L.; Varanasi, U. Bioaccumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by marine organisms. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 1995, 143, 79–165. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Mean PAH profiles and alkylated compounds in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill. Error bars depict the 95% confidence level around the means. Legend: naphthalene (NAF), acenaphthylene (ACENAFTY), acenaphthene (ACE), fluorine (FLUOR), dibenzothiophene (DBz), phenanthrene (FEN), anthracene (ANT), fluoranthene (FLUORAN), pyrene (PIR), benzo[a]anthracene (BaA), chrysene (CRI), benzo[b]fluoranthene (BbFt), benzo[k]fluoranthene (BkFt), benzo[e]pyrene (BePy), benzo[a]pyrene (BaPy), perylene (Per), perileno, indeno [1,2,3-cd]pyrene (I-Py), dibenz[a,h]anthracene (DBahA), and benzo[ghi]perylene (BghiP).

Figure 1.

Mean PAH profiles and alkylated compounds in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill. Error bars depict the 95% confidence level around the means. Legend: naphthalene (NAF), acenaphthylene (ACENAFTY), acenaphthene (ACE), fluorine (FLUOR), dibenzothiophene (DBz), phenanthrene (FEN), anthracene (ANT), fluoranthene (FLUORAN), pyrene (PIR), benzo[a]anthracene (BaA), chrysene (CRI), benzo[b]fluoranthene (BbFt), benzo[k]fluoranthene (BkFt), benzo[e]pyrene (BePy), benzo[a]pyrene (BaPy), perylene (Per), perileno, indeno [1,2,3-cd]pyrene (I-Py), dibenz[a,h]anthracene (DBahA), and benzo[ghi]perylene (BghiP).

Figure 2.

PAH and alkylated compounds percentages in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill. A: crab from rainy season of 2019; B: crab from dry season of 2019; C: fish from dry season of 2019; D: fish from dry season of 2021; E: shellfish from dry season of 2019; and F: shellfish from dry season of 2021.

Figure 2.

PAH and alkylated compounds percentages in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill. A: crab from rainy season of 2019; B: crab from dry season of 2019; C: fish from dry season of 2019; D: fish from dry season of 2021; E: shellfish from dry season of 2019; and F: shellfish from dry season of 2021.

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis (PCA) based on PAH concentrations in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill. Black: shellfish from dry season of 2019; Gray: shellfish from dry season of 2021; Green: crab from rainy season of 2019; Blue: crab from dry season of 2019; Red: fish from dry season of 2019; Purple: fish from dry season of 2021.

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis (PCA) based on PAH concentrations in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill. Black: shellfish from dry season of 2019; Gray: shellfish from dry season of 2021; Green: crab from rainy season of 2019; Blue: crab from dry season of 2019; Red: fish from dry season of 2019; Purple: fish from dry season of 2021.

Figure 4.

ΣPAH concentrations in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill. Common lowercase letter shows differences between the collect season (P< 0.05). Capital letter shows differences between species (P<0.05). Barrs means error values (95%).

Figure 4.

ΣPAH concentrations in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill. Common lowercase letter shows differences between the collect season (P< 0.05). Capital letter shows differences between species (P<0.05). Barrs means error values (95%).

Table 1.

Physiological parameters for the collected seafood on the Parnaiba Delta River and their effective concentrations of PAHs predicted using the optimized PBPK model.

Table 1.

Physiological parameters for the collected seafood on the Parnaiba Delta River and their effective concentrations of PAHs predicted using the optimized PBPK model.

| ID |

Species |

Habitat |

Season |

Length (cm) |

Weight (g) |

| Shellfish |

Anomalocardia brasiliana |

sediment |

Rainy/2019 |

1.28 + 0.26 |

4.19 + 0.81 |

| Dry/2019 |

2.47 + 0.26 |

3.41 + 1.12 |

| Dry/2021 |

2.62 + 2.22 |

5.91 + 1.44 |

| Crab |

Ucides cordatus |

mangrove |

Rainy/2019 |

6.94 + 3.74 |

139.34+19.49 |

| Dry/2019 |

7.16 + 0.31 |

158.30+21.37 |

| Dry/2021 |

6.50 + 2.64 |

114.42+17.20 |

| Fish |

Mugil curema |

estuary |

Dry/2019 |

24.98+1.77 |

150.63+29.37 |

| Dry/2021 |

27.62+3.29 |

231.80+79.44 |

Table 2.

Relative potency of eight PAHs of high molecular weight.

Table 2.

Relative potency of eight PAHs of high molecular weight.

| PAH |

RP |

| Benz(a)anthracene |

0.145 |

| Chrysene |

0.0044 |

| Benzo(b)fluoranthene |

0.140 |

| Benzo(k)fluoranthene |

0.066 |

| Benzo(a)pyrene |

1.00 |

| Dibenz(a,h)anthracene |

1.11 |

| Indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene |

0.232 |

| Benzo(g,h,i)perylene |

0.022 |

Table 3.

Toxicity equivalent concentration of PAHs in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill.

Table 3.

Toxicity equivalent concentration of PAHs in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill.

| PAHs |

TEFBap

|

TEQ average (mg/kg) |

| 2019 |

2021 |

| Crab |

Fish |

Shellfish |

Fish |

Shellfish |

| Nap |

0.001 |

14.83 |

79.64 |

72.36 |

308.66 |

44.01 |

| Ace |

0.001 |

0 |

0 |

8.73 |

1.30 |

1.80 |

| Acy |

0.001 |

0 |

0 |

1.61 |

0.86 |

0 |

| Flu |

0.001 |

0 |

0 |

4.46 |

7.10 |

9.67 |

| Phe |

0.001 |

0 |

0 |

105.98 |

5.45 |

41.00 |

| Ant |

0.010 |

0 |

0 |

34.52 |

4.73 |

39.14 |

| Fla |

0.001 |

0 |

0 |

160.72 |

1.07 |

1.74 |

| Pyr |

0.001 |

2.96 |

2.96 |

0 |

0 |

17.50 |

| BaA |

0.100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

21.20 |

| Chy |

0.010 |

0 |

0 |

8.25 |

0 |

74.99 |

| BbF |

0.100 |

0 |

0 |

3.78 |

1.39 |

0 |

| BkF |

0.100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.96 |

1.44 |

| BaP |

1.000 |

0 |

0 |

1.34 |

3.65 |

1.61 |

| Ind |

0.100 |

0 |

3.37 |

10.19 |

1.34 |

2.98 |

| DahN |

1.000 |

3.37 |

0 |

5.21 |

0.91 |

3.64 |

| BghiP |

0.100 |

0 |

0 |

13.63 |

0 |

0 |

Table 4.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) concentration in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill.

Table 4.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) concentration in crab, fish and shellfish from Parnaiba Delta River, Piaui, during and after the 2019 oil spill.

| PAHs |

LOC* |

LOC (ng/g ww) |

| 2019 |

2021 |

| Crab |

Fish |

Shellfish |

Fish |

Shellfish |

| Non-carcinogenic |

| Nap |

6,670 |

944 |

175 |

193 |

45 |

318 |

| Ace |

20,000 |

0 |

0 |

1,603 |

10,765 |

7,762 |

| Acy |

- |

0 |

0 |

8,697 |

16,225 |

0 |

| Flu |

13,330 |

0 |

0 |

3,141 |

1,971 |

1,448 |

| Phe |

- |

0 |

0 |

132 |

2,568 |

341 |

| Ant |

100,000 |

0 |

0 |

40 |

296 |

36 |

| Fla |

13,330 |

0 |

0 |

87 |

13,056 |

8,055 |

| Pyr |

10,000 |

4,735 |

4,735 |

0 |

0,00 |

800 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Carcinogenic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BaA |

41 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| Chy |

1,364 |

0 |

0 |

169 |

0 |

18 |

| BbF |

43 |

0 |

0 |

37 |

100 |

0 |

| BkF |

91 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

145 |

97 |

| BaP |

6 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

4 |

8 |

| Ind |

5 |

0 |

41 |

14 |

104 |

47 |

| DahN |

26 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

15 |

4 |

| BghiP |

273 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).