Submitted:

29 September 2024

Posted:

30 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

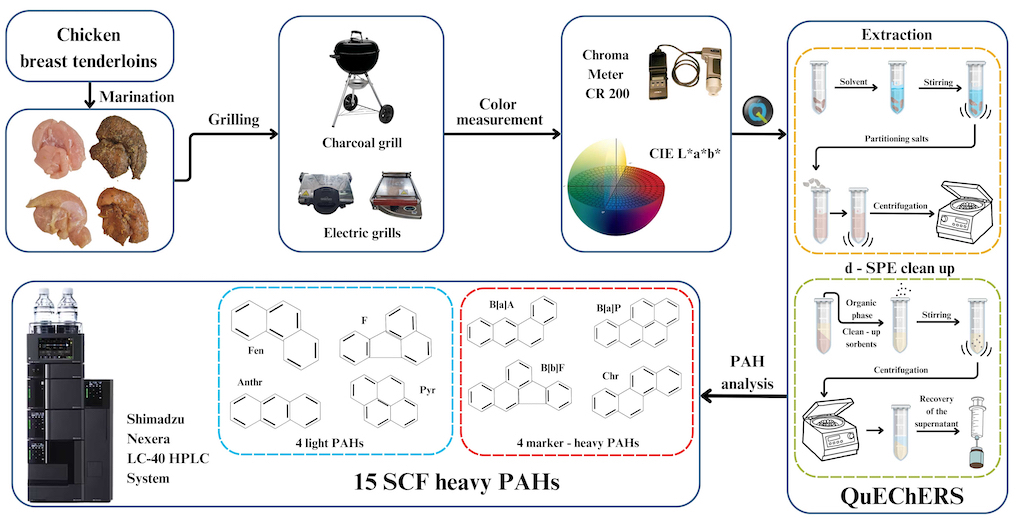

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Material and Preparation for Grilling

2.2. Grilling Tools and Cooking Procedure

2.3. Weight Loss

2.4. Color Measurement

2.5. Chemicals and Materials

2.6. Determination of PAHs Using QuEChERS–HPLC–FLD/DAD Method

2.7. Quantification and Validation of the QuEChERS–HPLC–FLD/DAD Method

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of the Meat Weight Loss after the Grilling Process

3.2. Color Analysis

3.3. Analysis of PAH Contamination in Grilled Meat Samples

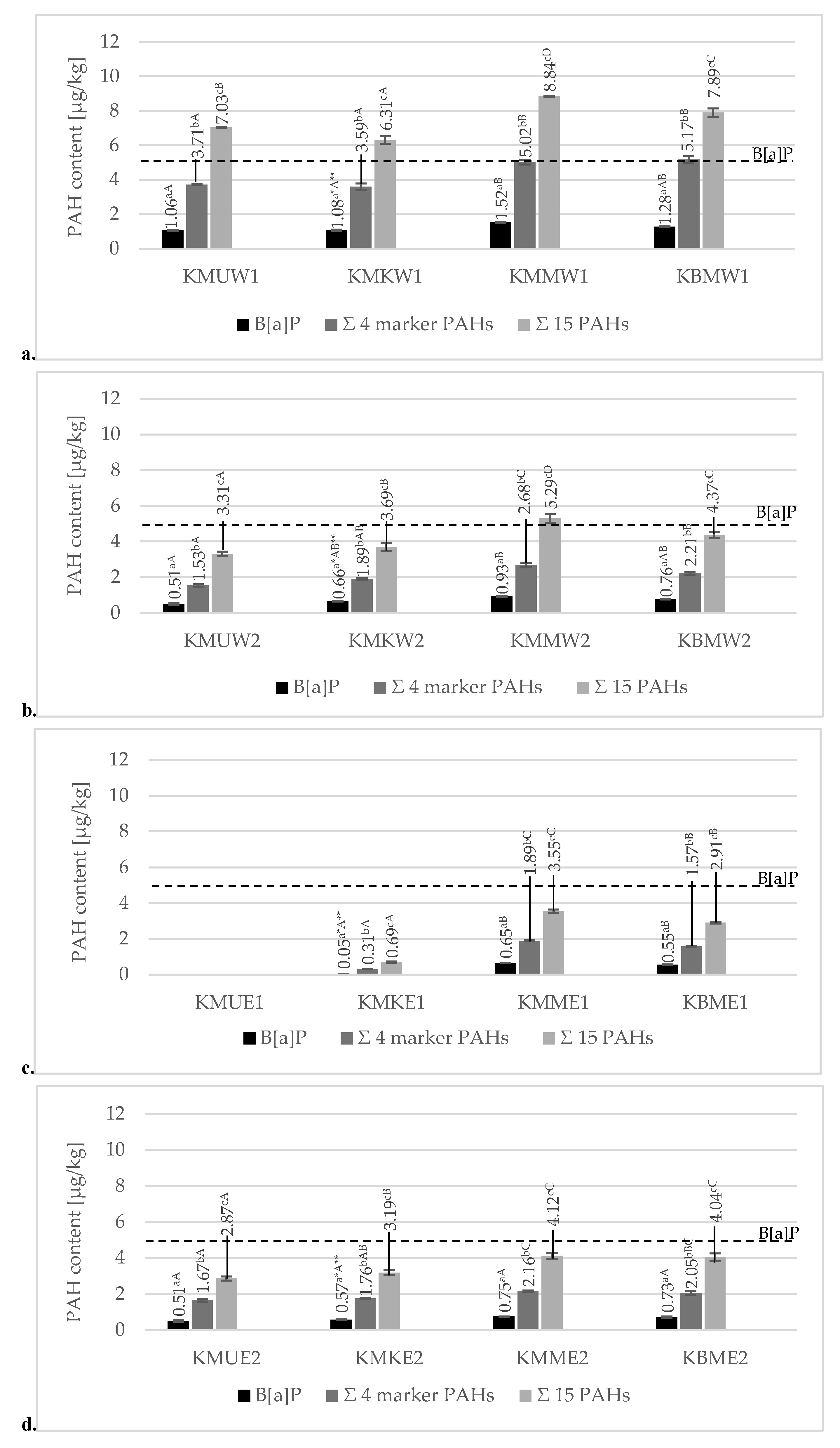

3.3.1. Effect of Various Grilling Tools on PAH Formation in Chicken Breast Tenderloins

3.3.2. Effect of Various Marinades on PAH Formation in Grilled Chicken Breast Tenderloins

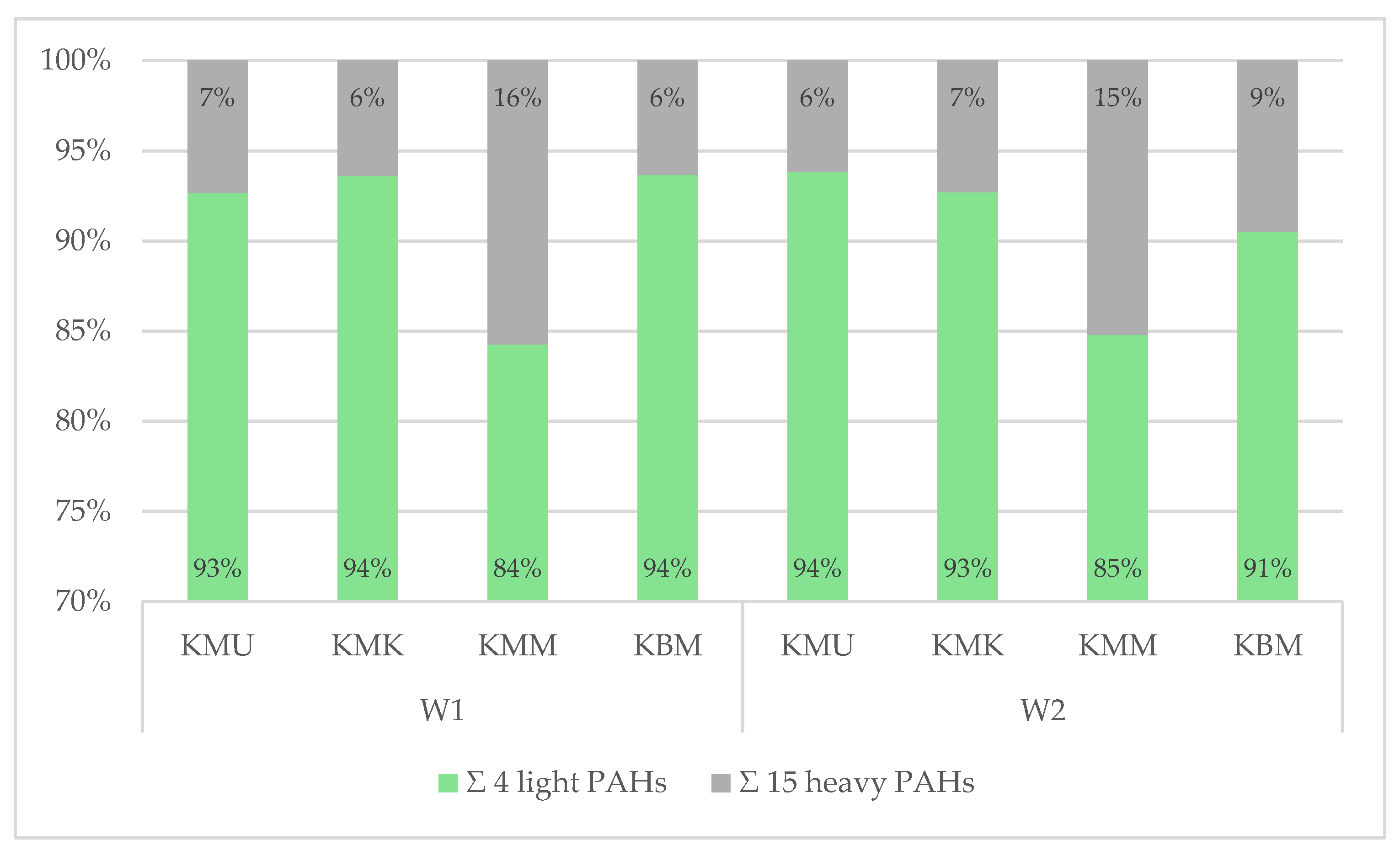

3.3.3. Analysis of PAH Qualitative Profiles

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lawal, A.T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: A review. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2017, 3, 1339841. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Analytical chemistry, formation, mitigation and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: from food processing to in vivo metabolic transformation. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20(2), 1422–1456. [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, US EPA. Environmental Fate of Selected Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Final Report, Task Two. Office of Toxic Substances, 1976, Washington D.C. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-03/documents/ambient-wqc-pah-1980.pdf (accessed on 02 July 2024).

- Scientific Committee on Food. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons–Occurrence in Foods, Dietary Exposure and Health Effects. Report No. SCF/CS/CNTM/PAH/29 Add1 Final 2002. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/scf/out154_en.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Some non–heterocyclic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and some related exposures. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 2010, Lyon, 92. Available online: http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol92/ (accessed online on 15 May 2024).

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Recommendation (EC) No. 108/2005 of 4 February 2005 on the Further Investigation into the Levels of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Certain Foods. Official Journal of the European Union 2005, L 34/3. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2005/108/oj (accessed on 01 June 2024).

- WHO. Summary Report of the Sixty-Fourth Meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additive (JECFA). The ILSI Press International Life Sciences Institute 2005, Washington, D.C., 8–17. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/home (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- European Food Safety Authority, EFSA. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Food. Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain Adopted on 9 June 2008. EFSA Journal 2008, 6, 724. [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, K. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In Handbook of Air Quality and Climate Change; Akimoto, H., Tanimoto, H.; Springer, Singapore 2022, 227–244. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2527-8_22-1 (accessed on 16 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Manousi, N.; Zachariadis, G.A. Recent advances in the extraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from environmental samples. Molecules 2020, 25(9), 2182. [CrossRef]

- Yabalak, E.; Aminzai, M.T.; Gizir, A.M.; Yang, Y. A review: subcritical water extraction of organic pollutants from environmental matrices. Molecules 2024, 29(1), 258. [CrossRef]

- Maciejczyk, M.; Janoszka, B.; Szumska, M.; Pastuszka, B.; Waligóra, S.; Damasiewicz-Bodzek, A.; Nowak, A.; Tyrpień-Golder, K. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Grilled Marshmallows. Molecules 2024, 29, 3119. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Pan, L.; Yang, D. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons’ Impact on Crops and Occurrence, Sources, and Detection Methods in Food: A Review. Foods 2024, 13, 1977. [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Youling, L.X. Plant protein–based alternatives of reconstructed meat: Science, technology, and challenges. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2020, 102, 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ng, K.; Warner, R.D.; Stockmann, R.; Fang, Z. Reduction strategies for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in processed foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022; 21(2), 1598-1626. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, G.R.; Guizellini, G.M.; Silva, S.A.; Almeida, A.P.; Pinaffi–Langley, A.C.C.; Rogero, M.M.; Camargo, A.C.; Torres, E.A.F.S. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in foods: biological effects, legislation, occurrence, analytical methods, and strategies in reduce their formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22(11), 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Onopiuk, A.; Kołodziejczak, K.; Szpicer, A.; Wojtasik–Kalinowska, I.; Wierzbicka, A.; Półtorak, A. Analysis of factors that influence the PAH profile and amount in meat products subjected to thermal processing. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2021, 115, 366–379. [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Hossain, A. Importance of insoluble–bound phenolics to the antioxidant potential is dictated by source material. Antioxidants 2023, 12(1), 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Ciecierska, M.; Dasiewicz, K.; Wołosiak, R. Method of minimizing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content in homogenized smoked meat sausages using different casing and variants of meat–fat raw material. Foods 2023, 12(22), 4120. [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Regulation (EU) No. 915/2023 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels of certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. Official Journal of the European Union 2011. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/835/oj (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Regulation (EU) No. 836/2011 amending Regulation (EC) No. 333/2007 laying down the methods of sampling and analysis for the levels of lead, cadmium, mercury, inorganic tin, 3-MCPD and benzo(a)pyrene in foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Union 2011. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/836/oj (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Ormian, M.; Augustyńska–Plejsnar, A.; Sokołowicz, Z. Jakość mięsa kur z chowu ekologicznego po zakończonym okresie nieśności. Post. Tech. Przem. Spoż. 2017, 2, 11–14. https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-32e03781-e3b3-43a6-bcc6-71e0577a20a2.

- Suleman, R.; Hui, T.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D. Comparative analysis of charcoal grilling, infrared grilling and superheated steam roasting on the color, textural quality and the heterocyclic aromatic amines of lamb patties. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2019, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Purslow, P.P.; Oiseth, S.; Hughes, J.; Warner, R.D. The structural basis of cooking loss in beef: variations with temperature and ageing. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89(1), 739–748. [CrossRef]

- Suman, P.S.; Mahesh, N.N.; Poulson, J.; Melvin, C.H. Factors influencing internal color of cooked meats. Meat Sci. 2016, 120, 133–144. [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.A.P.; Ferreira, V.C.S.; Madruga, M.S.; Estévez, M. Effect of the cooking method (grilling, roasting, frying and sous–vide) on the oxidation of thiols, tryptophan, alkaline amino acids and protein cross–linking in jerky chicken. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2016, 53, 3137–3146. [CrossRef]

- Wongmaneepratip, W.; Jom, K.N.; Vangai, K. Inhibitory effects of dietary antioxidants on the formation of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in grilled pork. Asian–Australasian J. Ani. Sci. 2019, 32(8), 1205–1210. [CrossRef]

- Badyda, A.J.; Rogula–Kozłowska, W.; Majewski, G.; Bralewska, K.; Widziewicz–Rzońca, K.; Piekarska, B.; Rogulski, M., Bihałowicz, J.S. Inhalation risk to PAHs and BTEX during barbecuing: The role of fuel/food type and route of exposure. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 440, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Fatma, H.M.A.; Abdel–Azeem, M.A.; Jehan, M.M.O.; Nasser, S.A. Effect of different grilling methods on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons content in grilled broiler chicken. J. Vet. Med. Res. 2023, 30, 1, 7–11. [CrossRef]

- Hamzawy, A.H.; Khorshid, M.; Elmarsafy, A.M.; Souaya, E.R. Estimated daily intake and health risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon by consumption of grilled meat and chicken in Egypt. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2016, 5(2), 435–448. [CrossRef]

- Onwukeme, V.I.; Obijiofor, O.C.; Asomugha, R.N.; Okafor, F.A. Impact of cooking methods on the levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in chicken meat. J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2015, 9(4), 21–27. [CrossRef]

- Husseini, M.E.; Makkouk, R.; Rabaa, A.; Omae, F.A.; Jaber, F. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH4) in the traditional Lebanese grilled chicken: implementation of new, rapid and economic analysis method. Food Anal. Methods. 2017, 11, 201–214. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12161-017-0990-3.

- Wang, Ch.; Xie, Y.; Wang, H.; Bai, Y.; Dai, C.; Li, C.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G. Phenolic compounds in beer inhibit formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from charcoal–grilled chicken wings. Food Chem. 2019, 294, 578–586. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Li, C.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G. Effects of phenolic acid marinades on the formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in charcoal–grilled chicken wings. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82(4), 684–690. [CrossRef]

- Yunita, C.N.; Radiati, L.E.; Rosyidi, D. Effect of lemon marination on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and quality of chicken satay. J. Pen. Pend. IPA 2023, 9(6), 4723–4730. [CrossRef]

- Kazazic, M.; Djapo–Lavic, M.; Mehic, E.; Jesenkovic–Habul, L. Monitoring of honey contamination with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Herzegovina region. Chem. Ecol. 2020, 36, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Nor Hasyimah, A.K.; Jinap, S.; Sanny, M.; Ainaatul, A.I.; Sukor, R.; Jambari, N.N.; Nordin, N.; Jahurul, M.H.A. Effects of honey–spices marination on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic amines formation in gas–grilled beef satay. Polycycl. Aromat. Comp. 2020, 42(4), 1620–1648. [CrossRef]

- Sumer, G.; Oz, F. The effect of direct and indirect barbecue cooking on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon formation and beef quality. Foods 2023, 12(7), 1–15. [CrossRef]

| Marinade treatment | Ingredients [g/100 g of meat] | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Universal marinade | 5 g universal seasoning (composition: salt, rosemary (10.3%), basil, sugar, onion, paprika, oregano, marjoram, ground mustard, coriander, sunflower oil, thyme, lemon juice, turmeric, cayenne pepper), 5 g refined rapeseed oil | MU |

| Chicken marinade | 5 g chicken seasoning (composition: salt, coriander (11.0%), granulated garlic, sweet pepper (6.5%), rosemary, fenugreek (3.0%), basil (2.2%), black pepper, chili, turmeric, ginger, thyme), 5 g refined rapeseed oil | MK |

| Honey–mustard marinade | 5 g spicy mustard (water, white mustard, spirit vinegar, black mustard, sugar, salt, aroma, turmeric extract), 3.5 g lime honey, 1 g refined rapeseed oil, 0.5 g freshly squeezed lemon juice | MM |

| Type of grill | Grill temperature [℃] | Grilling time [min] | Temperature at the end of the grilling process in the geometric center of the product [℃] |

|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | 240 – 300 | 8 | 88.1 |

| W2 | 170 – 220 | 13 | 81.3 |

| E1 | 180 – 200 | 10 | 85.1 |

| E2 | 200 – 220 | 10 | 87.8 |

| PAH | Calibration curve | Correlation coefficient r2 | Linearity range (µg/L) | LOD (µg/kg) | LOQ (µg/kg) | Recovery for 100 µg/kg of sample fortification | Recovery for 10 µg/kg of sample fortification | Recovery for 1 µg/kg of sample fortification | Recovery (%) * | RSD (%) * | HORRATR value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phen | y = 102211x + 37486.4 | 0.9997 | 1–50 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 81.5 | 78.8 | 76.9 | 79.1 | 8.5 | 0.7 |

| Anthr | y = 62303.9x + 26899.6 | 0.9990 | 1–50 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 81.8 | 77.9 | 74.8 | 78.2 | 8.6 | 0.7 |

| F | y = 23407.8x + 35387.1 | 0.9993 | 1–50 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 88.3 | 86.7 | 81.8 | 85.6 | 9.4 | 0.8 |

| Pyr | y = 268840x + 86012.2 | 0.9997 | 1–50 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 91.1 | 88.9 | 86.6 | 88.9 | 9.7 | 0.8 |

| C[cd]P | y = 221120x + 11345 | 0.9993 | 2–50 | 0.35 | 0.70 | 107.5 | 108.9 | 109.9 | 108.8 | 8.7 | 0.7 |

| B[a]A | y = 120488x + 36275.5 | 0.9997 | 1–50 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 92.2 | 88.9 | 84.8 | 88.6 | 7.2 | 0.6 |

| Chr | y = 39749.7x + 12690.7 | 0.9997 | 1–50 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 87.5 | 84.0 | 82.9 | 84.8 | 7.7 | 0.6 |

| 5-MChr | y = 97566x – 6394.4 | 0.9999 | 1–50 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 89.8 | 83.5 | 80.2 | 84.5 | 7.8 | 0.7 |

| B[j]F | y = 1600.7x + 196.91 | 0.9997 | 2–50 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 82.7 | 81.2 | 78.9 | 80.9 | 7.5 | 0.6 |

| B[b]F | y = 64900x + 19646.3 | 0.9997 | 1–50 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 91.3 | 86.4 | 80.5 | 86.1 | 8.4 | 0.7 |

| B[k]F | y = 193555x + 59017.2 | 0.9997 | 1–50 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 92.8 | 88.6 | 84.1 | 88.5 | 7.6 | 0.6 |

| B[a]P | y = 122195x + 65266.3 | 0.9998 | 1–50 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 91.6 | 89.8 | 86.3 | 89.2 | 7.7 | 0.6 |

| D[ah]A | y = 45718.9x + 11119 | 0.9999 | 1–50 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 85.1 | 81.5 | 80.1 | 82.2 | 8.2 | 0.7 |

| D[al]P | y = 359.96x – 154.23 | 0.9995 | 2–50 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 81.4 | 77.2 | 73.8 | 77.5 | 8.4 | 0.7 |

| B[ghi]P | y = 69415.7x + 18240.4 | 0.9999 | 1–50 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 88.6 | 85.2 | 82.7 | 85.5 | 8.5 | 0.7 |

| I[cd]P | y = 11025.7x + 1670.83 | 0.9997 | 1–50 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 83.6 | 81.4 | 78.0 | 81.0 | 8.6 | 0.7 |

| D[ae]P | y = 8144.2x + 456.41 | 0.9997 | 1–50 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 82.1 | 76.9 | 73.1 | 77.3 | 9.4 | 0.8 |

| D[ai]P | y = 226619x – 96869 | 0.9997 | 1–50 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 82.3 | 79.2 | 73.0 | 78.1 | 9.1 | 0.8 |

| D[ah]P | y = 172110x – 68308 | 0.9997 | 1–50 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 79.0 | 73.0 | 71.0 | 74.4 | 9.9 | 0.8 |

| Universal marinade | Chicken marinade | Honey–mustard marinade | Without marinade | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample code | Weight loss [%] | Sample code | Weight loss [%] | Sample code | Weight loss [%] | Sample code | Weight loss [%] |

| KMUW1 | 36.6±0.27c* | KMKW1 | 25.7±0.28c | KMMW1 | 39.0±0.28c | KBMW1 | 32.8±0.53c |

| KMUW2 | 15.7±0.36a | KMKW2 | 20.4±0.15b | KMMW2 | 34.0±0.19b | KBMW2 | 18.0±0.46a |

| KMUE1 | 16.2±0.04a | KMKE1 | 18.0±0.24a | KMME1 | 27.5±0.32a | KBME1 | 19.8±0.10b |

| KMUE2 | 23.6±0.05b | KMKE2 | 20.0±0.14b | KMME2 | 33.6±0.19b | KBME2 | 32.2±0.06c |

| Cooking method | Sample | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before grilling | KMU | 33.27±1.07a*AB** | 6.39±0.25bA | 11.10±0.51bA |

| KMK | 36.00±1.08aA | 9.93±0.68bA | 13.06±0.82bA | |

| KMM | 48.12±0.64bAB | 2.26±0.15aA | 4.60±0.38aA | |

| KBM | 45.46±2.81bA | 4.45±0.27abA | 3.02±0.63aA | |

| Charcoal grill without a tray | KMUW1 | 32.88±1.63aA | 9.87±0.69aA | 24.76±0.42bB |

| KMKW1 | 48.22±0.77bB | 11.60±1.12abB | 22.28±0.99abB | |

| KMMW1 | 38.74±0.18aA | 15.96±0.07bB | 17.33±0.40aB | |

| KBMW1 | 57.43±0.32cB | 11.55±0.35aB | 24.23±1.93bC | |

| Charcoal grill with an aluminum tray | KMUW2 | 46.93±0.74aB | 6.13±0.39bA | 25.99±0.71cB |

| KMKW2 | 53.84±2.06bB | 7.68±0.19bA | 29.34±0.86cC | |

| KMMW2 | 65.46±0.23cC | 4.95±0.62abA | 23.33±1.29bCD | |

| KBMW2 | 74.79±1.64dC | 3.79±0.52aA | 14.87±0.19aB | |

| Ceramic contact grill | KMUE1 | 41.22±1.27aBC | 7.96±0.90bA | 21.44±1.18aB |

| KMKE1 | 48.86±1.41aB | 11.19±0.45cB | 24.16±1.44acBC | |

| KMME1 | 54.22±1.15bB | 13.43±0.66cBC | 28.50±0.72cD | |

| KBME1 | 69.81±1.83cC | 3.85±0.53aA | 19.72±1.19aBC | |

| Cast iron contact grill | KMUE2 | 43.23±1.57aC | 7.87±0.66aA | 25.06±0.70abB |

| KMKE2 | 50.86±1.08bB | 9.93±0.42aAB | 27.45±0.60bBC | |

| KMME2 | 52.54±1.30abB | 14.19±0.74bC | 17.19±0.46aBC | |

| KBME2 | 68.68±1.48cC | 5.27±0.18aA | 22.21±1.65abC |

| Charcoal grill without a tray | Charcoal grill with an aluminum tray | Ceramic contact grill | Cast iron contact grill | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | ΔE | Sample | ΔE | Sample | ΔE | Sample | ΔE |

| KMUW1 | 14.10±0.20a*AB** | KMUW2 | 20.21±1.69aC | KMUE1 | 13.14±0.91aA | KMUE2 | 17.21±2.20aBC |

| KMKW1 | 15.40±0.86aA | KMKW2 | 24.26±2.53bC | KMKE1 | 17.03±0.87aAB | KMKE2 | 20.68±0.81aBC |

| KMMW1 | 20.92±0.48bA | KMMW2 | 25.67±1.15bB | KMME1 | 27.08±0.92bB | KMME2 | 17.90±0.80aA |

| KBMW1 | 25.37±2.29cA | KBMW2 | 31.64±3.18cB | KBME1 | 29.54±2.87bB | KBME2 | 30.14±2.66bB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).