Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

12 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

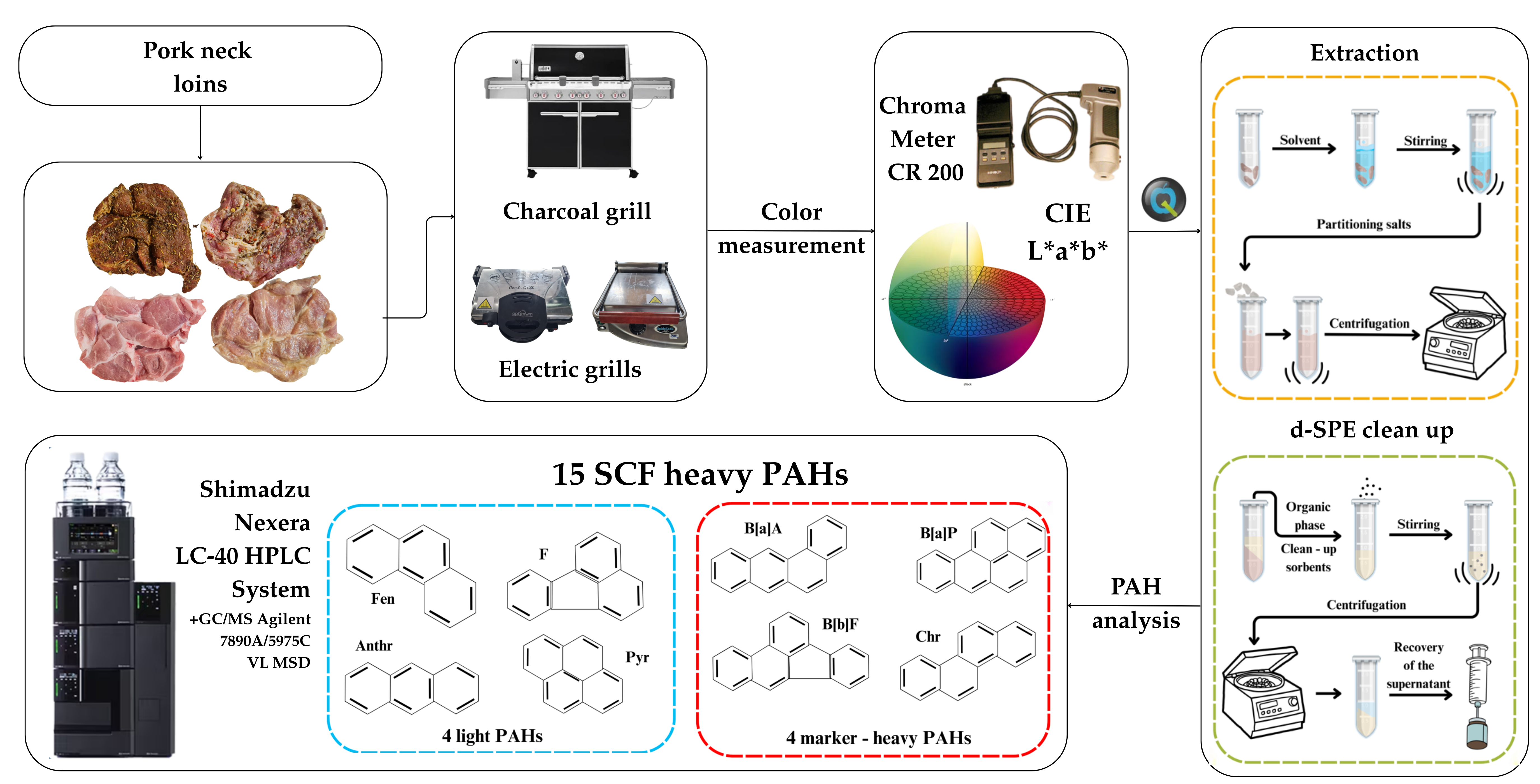

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Material, Its Preparation for Grilling, and Experimental Design

2.2. Grilling Tools and Cooking Procedure

2.3. Weight Loss

2.4. Color Measurement

2.5. Chemicals and Materials

2.6. Determination of PAHs Using the QuEChERS–HPLC–FLD/DAD Method

2.7. Quantification and Validation of the QuEChERS–HPLC–FLD/DAD Method

2.8. Confirmation of Results by GC/MS Method

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of the Meat Weight Loss After the Grilling Process

3.2. Color Analysis

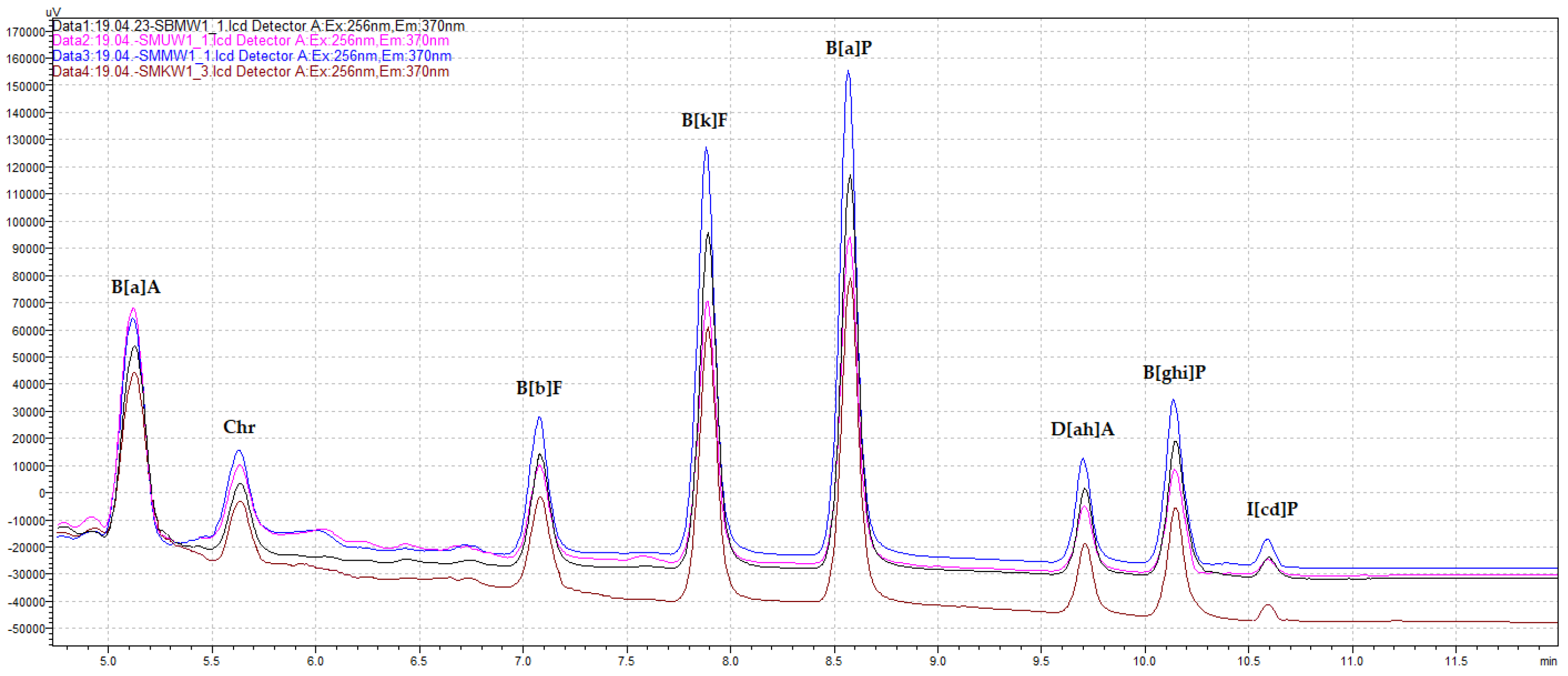

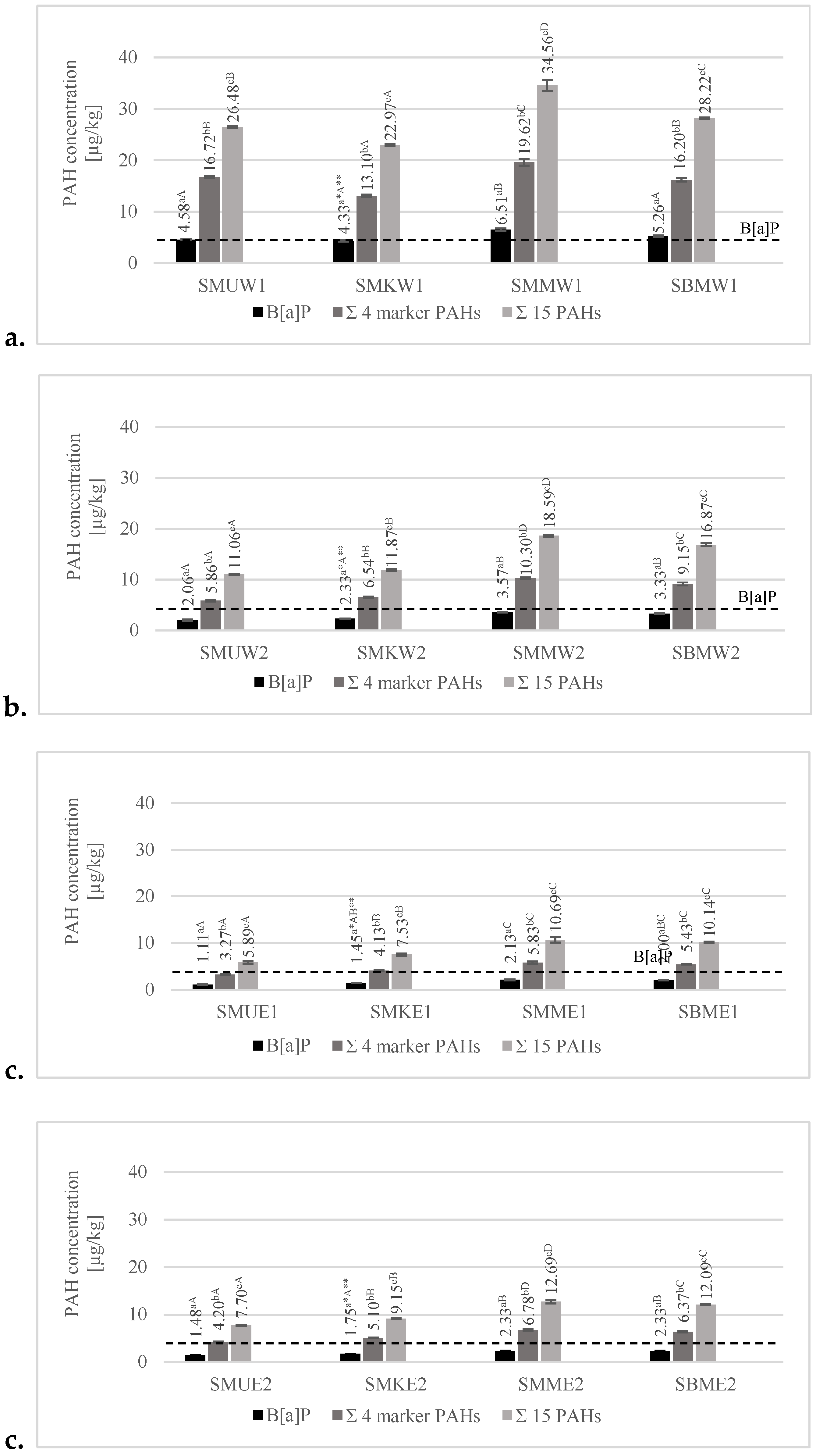

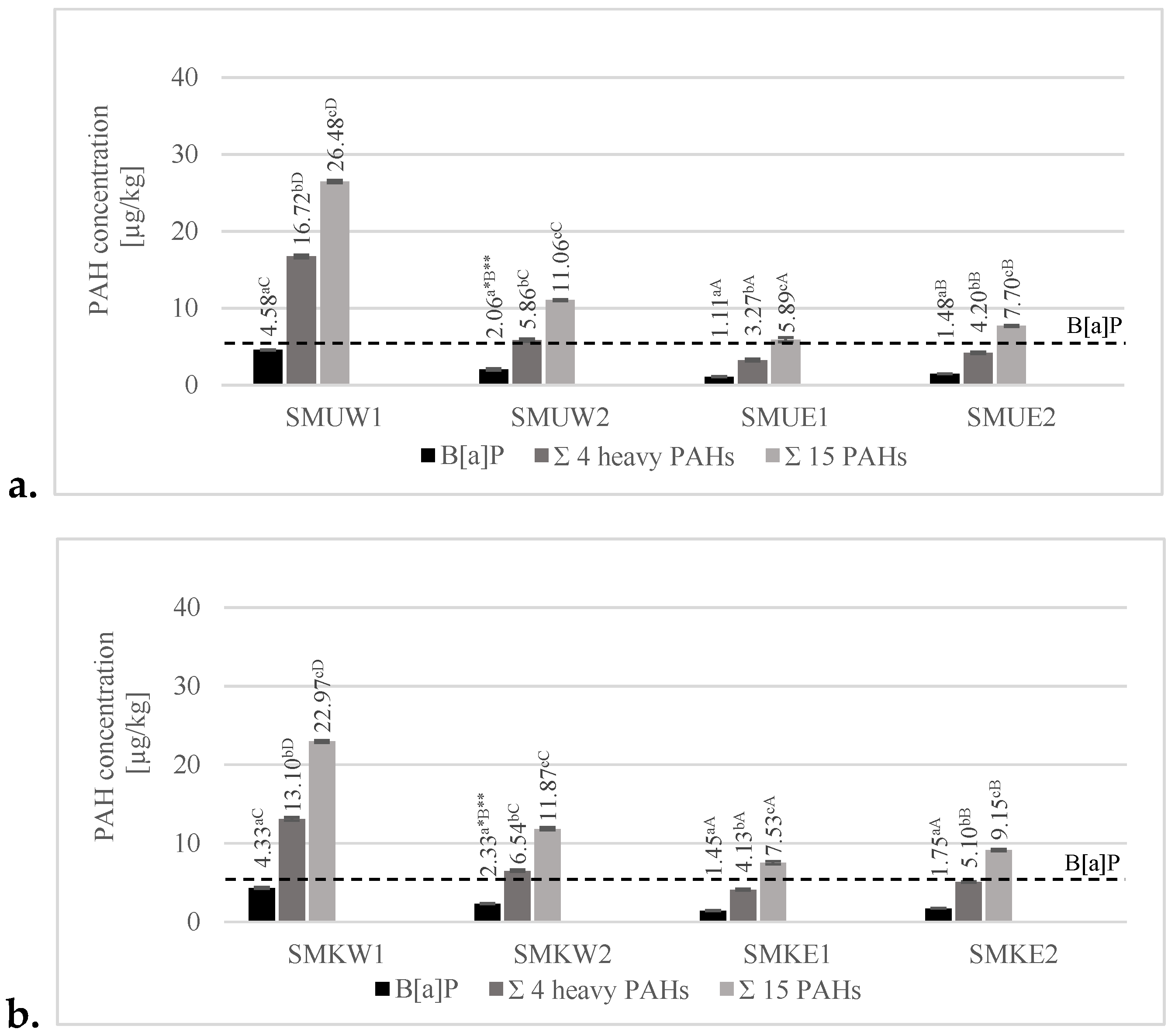

3.3. Analysis of PAH Contamination in Grilled Pork Neck Loins

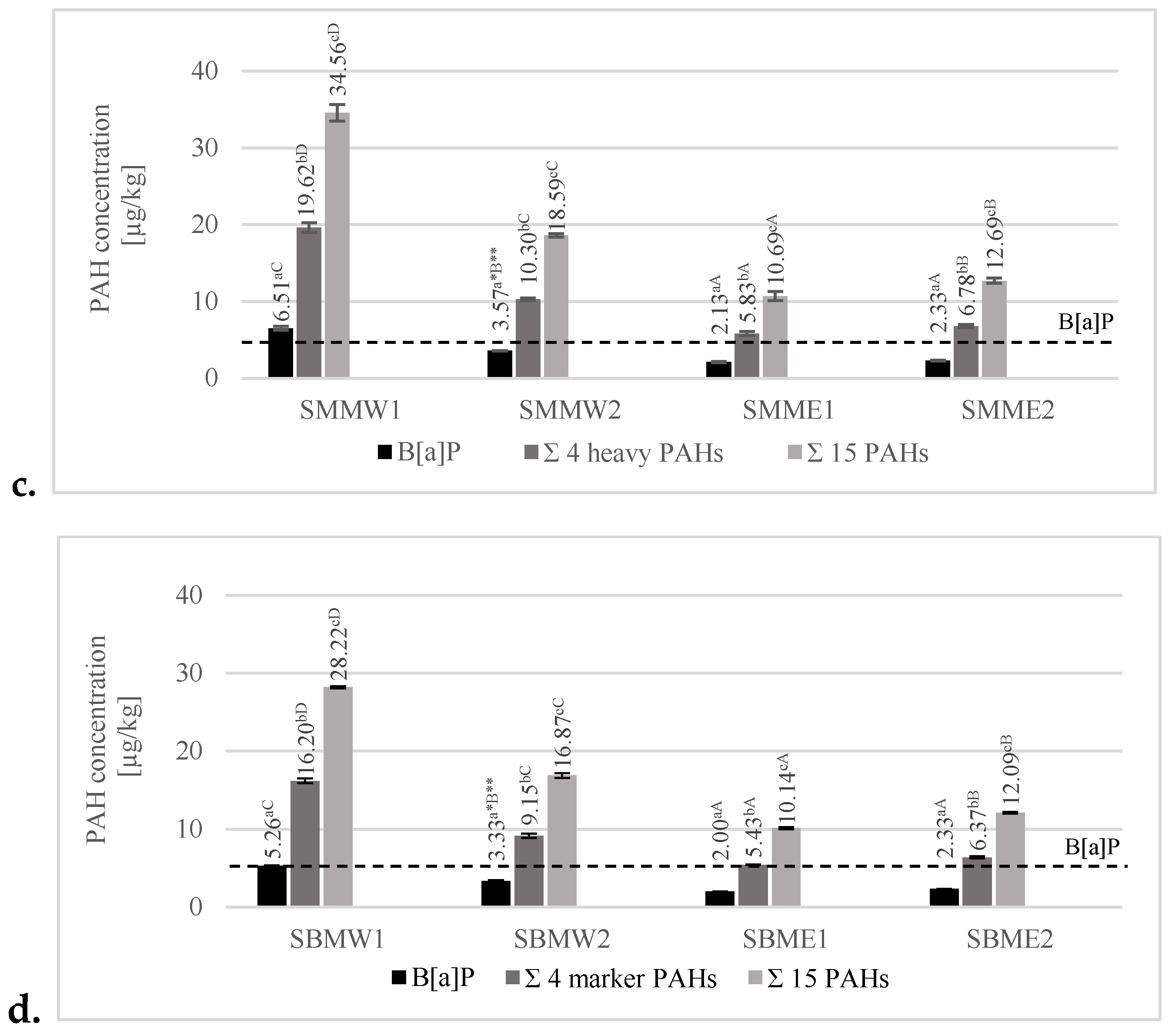

3.3.1. Effects of Various Grilling Tools on the Formation of B[a]P, 4 Heavy–Marker PAHs, and 15 PAHs

3.3.2. Effect of Various Marinades on PAH Formation of B[a]P, 4 Heavy–Marker PAHs, and 15 PAHs

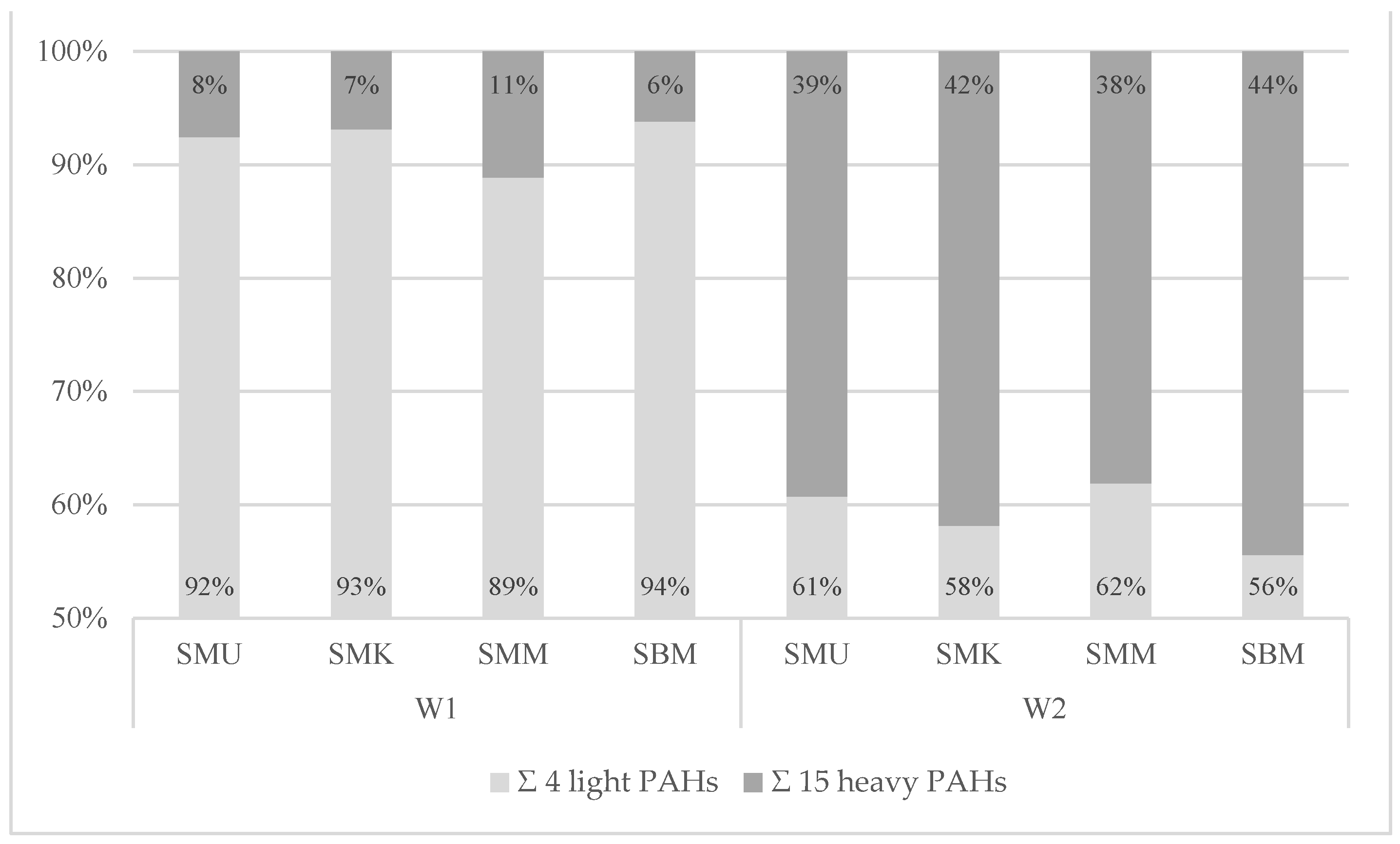

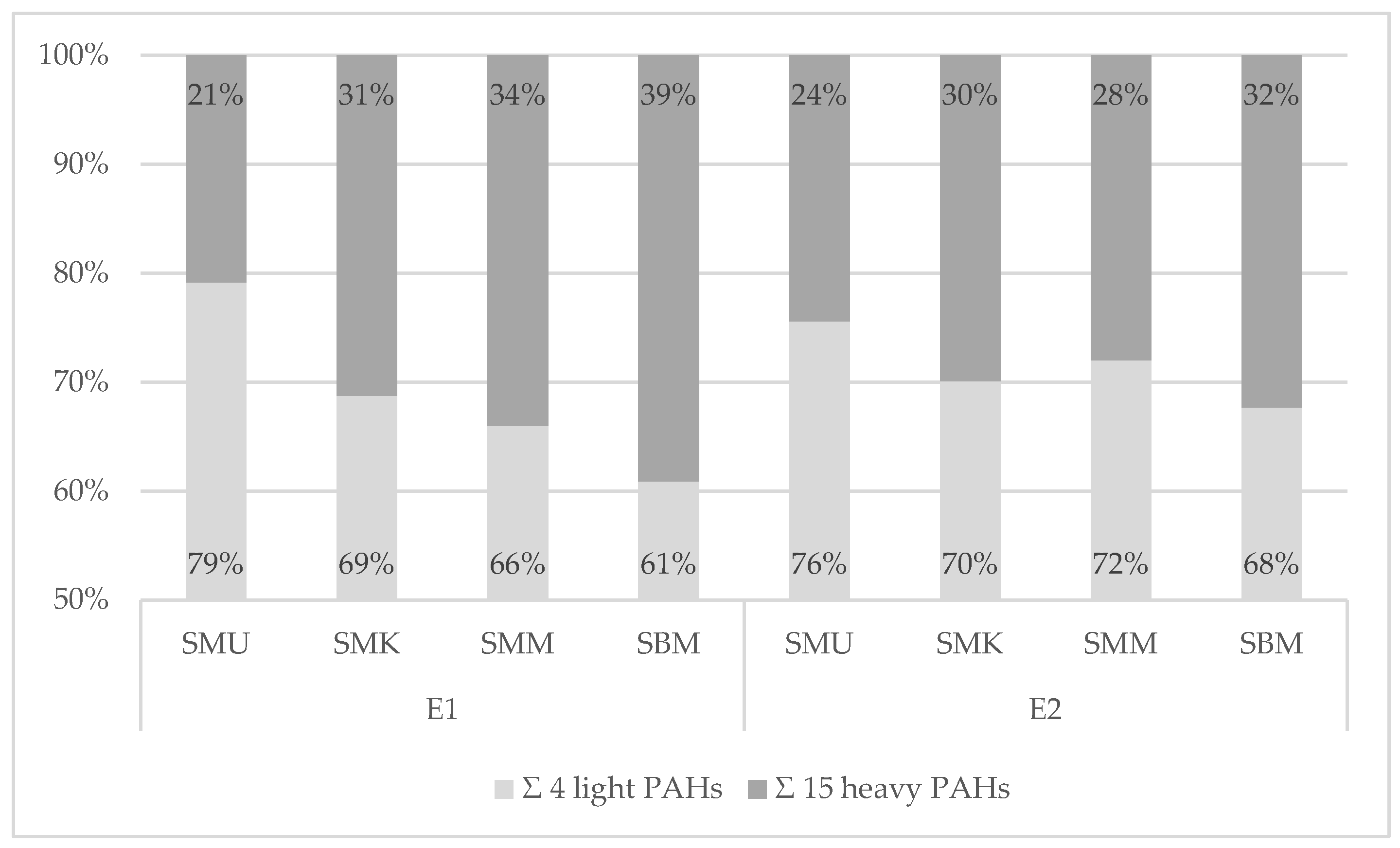

3.3.3. Analysis of PAH Qualitative Profiles of PAH Contamination

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lawal, A.T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: A review. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2017, 3, 1339841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhau, H.; Cai, K.; Xu, B. A review of hazards in meat products: multiple pathways, hazards and mitigation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Food Chem. 2024, 445, 138718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogashane, T.M.; Mokoena, L.; Tshilongo, J. A review on recent developments in the extraction and identification of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from environmental samples. Water 2024, 16, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, US EPA. Environmental Fate of Selected Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Final Report, Task Two. Office of Toxic Substances, 1976, Washington D.C. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-03/documents/ambient-wqc-pah-1980.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Scientific Committee on Food. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons–Occurrence in Foods, Dietary Exposure and Health Effects. Report No. SCF/CS/CNTM/PAH/29 Add1 Final 2002. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/scf/out154_en.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Recommendation (EC) No. 108/2005 of 4 February 2005 on the Further Investigation into the Levels of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Certain Foods. Official Journal of the European Union 2005, L 34/3. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2005/108/oj (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- WHO. Summary Report of the Sixty-Fourth Meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additive (JECFA). The ILSI Press International Life Sciences Institute 2005, Washington, D.C., 8–17. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/home (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority, EFSA. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Food. Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain Adopted on 9 June 2008. EFSA Journal 2008, 6, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalteh, S.; Ahmadi, E.; Ghaffari, H.; Yousefzadeh, S.; Abtahi, M.; Dobaradan, S.; Saeedi, R. Occurence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in meat and meat products: systematic review, meta–analysis and probabilistic human health risk. Int. J. Env. Anal. Chem. 2022, 104, 3533–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Wang, Z.; Li, Ch.; Wang, T.; Xiao, T.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, M.; Gai, S.; Hou, B.; Liu, D. Raw to charred: changes of protein oxidation and in vitro digestion characteristics of grilled lamb. Meat Sci. 2023, 204, 109239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.T.H.; Tongkhao, K.; Hengniran, P.; Vangnai, K. Assessment of high–temperature refined charcoal to improve the safety of grilled meat through the reduction of carcinogenic PAHs. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, G.R.; Guizellini, G.M.; Silva, S.A.; Almeida, A.P.; Pinaffi–Langley, A.C.C.; Rogero, M.M.; Camargo, A.C.; Torres, E.A.F.S. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in foods: biological effects, legislation, occurrence, analytical methods, and strategies in reduce their formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, G.; Oz, F. The effect of direct and indirect barbecue cooking on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon formation and beef quality. Foods 2023, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciecierska, M.; Komorowska, U. Effect of Different Marinades and Types of Grills on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Content in Grilled Chicken Breast Tenderloins. Foods 2023, 13, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.H.; Chen, S.; Huang, C.W.; Chen, C.J.; Chen, B.H. Occurrence and exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in kindling–free–charcoal grilled meat products in Taiwan. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 71, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.C.; Pyo, H.; Kim, W.; Yoon, K.S. Effects of cooking methods and tea marinades on the formation of benzo[a]pyrene in grilled pork belly (Samgyeopsal). Meat Sci. 2017, 129, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oformata, B.I.; Ogugua, A.J.; Akinseye, V.O.; Nweze, E.J.; Nwanta, J.A.; Obidike, R.I. Onions, salt and palm oil marination reduced polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon in cooked chevon and beef meat: a risk assessment study. Polycycl. Aromat. Comp. 2024, 44, 7087–7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Regulation (EU) No. 915/2023 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels of certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. Off. J. Eur. Union 2011. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/835/oj (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Ciecierska, M.; Dasiewicz, K.; Wołosiak, R. Method of minimizing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content in homogenized smoked meat sausages using different casing and variants of meat–fat raw material. Foods 2023, 12, 4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Regulation (EU) No. 836/2011 amending Regulation (EC) No. 333/2007 laying down the methods of sampling and analysis for the levels of lead, cadmium, mercury, inorganic tin, 3-MCPD and benzo(a)pyrene in foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2011. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/836/oj (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Wilczyńska, A.; Żak, N.; Stasiuk, E. Content of selected harmful metals (Zn, Pb, Cd) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in honeys from apiaries located in urbanized areas. Foods 2024, 13, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purslow, P.P.; Oiseth, S.; Hughes, J.; Warner, R.D. The structural basis of cooking loss in beef: Variations with temperature and ageing. Foods Res. Int. 2016, 89, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latoch, A.; Głuchowski, A.; Czarniecka–Skubina, E. Sous–vide as an alternative method of cooking to improve the quality of meat: a review. Foods 2023, 12, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alugwu, S.U.; Okonkwo, T.M.; Ngadi, M.O. Effects of cooking conditions on cooking yield, juiciness, instrumental and sensory texture properties of chicken breast meat. A. Food Sci. J. 2024, 23, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- War Nur Zahidah, W.Z.; Raja Arief Deli, R.N.; Noor Zainah, A.; Norhida Arnieza, M.; Mohd Fakhri, H. Effect of retort processing on the microbiological, sensory evaluation and physicochemical properties of the ready–to–eat grilled beef. A. Food Sci. J. 2024, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assogba, M.F.; Kpoclou, Y.E.; Ahouansou, R.H.; Daloe, A.; Sanya, E.; Mahillon, J.; Scippo, M.L.; Hounhouigan, D.J.; Anihouvi, V.B. Thermal and technological performances of traditional grills used in cottage industry and effects on physicochemical; characteristics of grilled pork. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Barido, F.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kwon, J.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.; Hur, S.J.; Jang, A. Effect of extract of Perilla leaves on the Quality characteristics and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons of charcoal barbecued pork patty. Food Sci. of An. Res. 2022, 43, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.A.P.; Ferreira, V.C.S.; Madruga, M.S.; Estévez, M. Effect of the cooking method (grilling, roasting, frying and sous–vide) on the oxidation of thiols, tryptophan, alkaline amino acids and protein cross–linking in jerky chicken. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2016, 53, 3137–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, S. Reduction of the heterocyclic amines in grilled beef patties through the combination of thermal food processing techniques without destroying the grilling quality characteristics. Foods 2021, 10, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Kim, S.Y.; Moon, J.S.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, D.H.; Yoon, H.J. Effects of grilling procedures on levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in grilled meats. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeyeye, S.A.O. Heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in cooked meat products: a review. Polycycl. Aromat. Comp. 2018, 40, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, Z.; Shehzad, F.; Rahat, A.; Shah, HU.; Khan, S. Effect of marination and grilling techniques in lowering the level of polyaromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metal in barbecued meat. Sarhad J. Agric. 2019, 35, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldaly, E.A.; Hussein, M.A.; El–Gaml, A.M.A.; Elhefny, D. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in charcoal grilled meat (Kebab) and kofta and the effect of marinating on their existence. Zag. Vet. J. 2016, 44, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, T.; Viegas, O.; Silva, M.; Martins, Z.E.; Fernandes, I.; Ferreira, I.M.L.P.V.O.; Pinho, O.; Mateus, N.; Calhau, C. Inhibitory effects of vinegars on the formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in charcoal-grilled pork. Meat Sci. 2020, 167, 108083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulanda, S.; Janoszka, B. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in roasted pork meat and the effect of dried fruits on PAH content. Int. J Env. Res. Pub. Health. 2023, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, E.; Edris, A.M.; Kirella, G.A.K. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon in charcoal beef steak and inhibitory profile of thyme oil, lactic acid bacteria and marinating on their existence. Pakistan J. of Zool. 2023, 56, 2667–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Ch.; Huang, S.; Lei, Y.; Huang, M.; Zhang, X. Inhibitory effect of coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) extract marinades on the formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in roasted duck wings. Food Sci. Hum. Well. 2023, 12, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Cho, J.; Kim, D.; Park, T.S.; Jin, S.K.; Hur, S.J.; Lee, S.K.; Jang, A. Effects of Gochujang (Korean red pepper paste) marinade on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon formation in charcoal-grilled pork belly Food Sci. Anim. Res. 2021, 41, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazazic, M.; Djapo–Lavic, M.; Mehic, E.; Jesenkovic–Habul, L. Monitoring of honey contamination with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Herzegovina region. Chem. Ecol. 2020, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surma, M.; Sadowska–Rociek, A.; Draszanowska, A. Levels of contamination by pesticide residues, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and 5–hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) in honey retailed in Europe. Arch. Env. Con. Tox. 2023, 84, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor Hasyimah, A.K.; Jinap, S.; Sanny, M.; Ainaatul, A.I.; Sukor, R.; Jambari, N.N.; Nordin, N.; Jahurul, M.H.A. Effects of honey–spices marination on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic amines formation in gas–grilled beef satay. Polycycl. Aromat. Comp. 2020, 42, 1620–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Marinade Treatment | Ingredients [g/100 g of Meat] |

Code |

|---|---|---|

| Universal marinade | 5 g universal seasoning (composition: salt, rosemary (10.3%), basil, sugar, onion, paprika, oregano, marjoram, ground mustard, coriander, sunflower oil, thyme, lemon juice, turmeric, cayenne pepper), 5 g refined rapeseed oil | MU |

| Pork marinade | 5 g pork seasoning (composition: salt, garlic (22.0%), red pepper (14.0%), coriander, rosemary, black pepper, citric acid, parsley (2.2%), bay leaves), 5 g refined rapeseed oil | MK |

| Honey mustard marinade | 5 g spicy mustard (water, white mustard, spirit vinegar, black mustard, sugar, salt, aroma, turmeric extract), 3.5 g lime honey, 1 g refined rapeseed oil, 0.5 g freshly squeezed lemon juice | MM |

| Type of Grill |

Grill Temperature [℃] |

Grilling Time [min] |

Temperature at the End of the Grilling Process in the Product Geometric Center [℃] |

|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | 240 – 300 | 12 | 94.5 |

| W2 | 170 – 220 | 17 | 90.2 |

| E1 | 180 – 200 | 15 | 93.2 |

| E2 | 200 – 220 | 15 | 94.9 |

| Universal Marinade |

Pork Marinade |

Honey Mustard Marinade |

Without Marinade |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Code |

Weight Loss [%] | Sample Code |

Weight Loss [%] | Sample Code |

Weight Loss [%] | Sample Code |

Weight Loss [%] |

| SMUW1 | 41.1±1.63c* | SMKW1 | 54.7±0.57d | SMMW1 | 45.4±0.32b | SBMW1 | 50.3±0.23c |

| SMUW2 | 30.0±0.00a | SMKW2 | 32.0±0.50a | SMMW2 | 43.4±0.61a | SBMW2 | 34.5±0.62a |

| SMUE1 | 37.2±0.05b | SMKE1 | 38.0±0.12b | SMME1 | 52.0±0.08c | SBME1 | 45.9±0.09b |

| SMUE2 | 46.4±0.05d | SMKE2 | 43.4±0.13c | SMME2 | 53.5±0.15d | SBME2 | 54.8±0.00d |

| Cooking Method | Sample | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before grilling | SMU | 33.66±0.75a*A** | 10.52±0.92aB | 12.66±1.77bA |

| SMK | 37.16±0.28aA | 10.99±0.83aB | 5.38±0.61abA | |

| SMM | 52.19±0.56bB | 11.66±1.55aA | 8.01±0.86bA | |

| SBM | 448.70±2.90bB | 13.16±1.05aC | 4.24±0.42aA | |

| Charcoal grill without a tray | SMUW1 | 38.38±2.43aA | 6.54±0.27aA | 14.01±1.09bB |

| SMKW1 | 39.18±4.29aA | 9.00±2.15aB | 7.46±0.77aA | |

| SMMW1 | 48.46±1.67bAB | 9.25±0.87aA | 10.55±0.61abA | |

| SBMW1 | 44.70±3.80aA | 12.21±2.16bBC | 7.91±3.04aAB | |

| Charcoal grill with an aluminum tray | SMUW2 | 40.89±2.11aA | 6.32±1.25aA | 14.45±1.00bB |

| SMKW2 | 46.42±1.22aB | 5.25±0.63aA | 12.38±1.25abB | |

| SMMW2 | 44.30±3.96aA | 11.01±0.31bA | 10.45±0.26aA | |

| SBMW2 | 55.88±2.20bC | 7.82±0.67aA | 11.31±1.32abBC | |

| Ceramic contact grill | SMUE1 | 40.59±4.92aA | 6.86±0.85aA | 8.59±1.22aA |

| SMKE1 | 40.26±1.40aAB | 8.03±1.00aAB | 7.52±1.73aA | |

| SMME1 | 49.45±2.73bAB | 8.71±0.65aA | 9.84±0.76abA | |

| SBME1 | 47.28±2.49bB | 8.91±0.94aA | 13.51±1.74bC | |

| Cast iron contact grill | SMUE2 | 35.02±1.26aA | 7.69±0.80aA | 10.82±0.92abAB |

| SMKE2 | 40.24±1.62aAB | 8.42±2.18aB | 7.71±1.59aA | |

| SMME2 | 46.87±0.68bAB | 8.25±0.25aA | 9.39±0.33abA | |

| SBME2 | 46.96±4.86bB | 9.85±1.89aAB | 11.76±3.40bC |

| Charcoal Grill Without a Tray | Charcoal Grill With an Aluminum Tray | Ceramic Contact Grill | Cast Iron Contact Grill | ||||

| Sample | ΔE | Sample | ΔE | Sample | ΔE | Sample | ΔE |

| SMUW1 | 6.32±2.59a*A** | SMUW2 | 8.55±2.66abA | SMUE1 | 14.96±4.45bB | SMUE2 | 4.53±0.85aA |

| SMKW1 | 3.52±1.22aA | SMKW2 | 12.95±1.54bB | SMKE1 | 4.64±1.74aA | SMKE2 | 5.54±1.08aA |

| SMMW1 | 5.12±1.81aA | SMMW2 | 8.29±3.07aA | SMME1 | 4.42±1.95aA | SMME2 | 6.46±1.05aA |

| SBMW1 | 14.51±2.36bA | SBMW2 | 11.40±3.18bA | SBME1 | 10.30±1.37bA | SBME2 | 12.51±1.95bA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).