Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

05 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

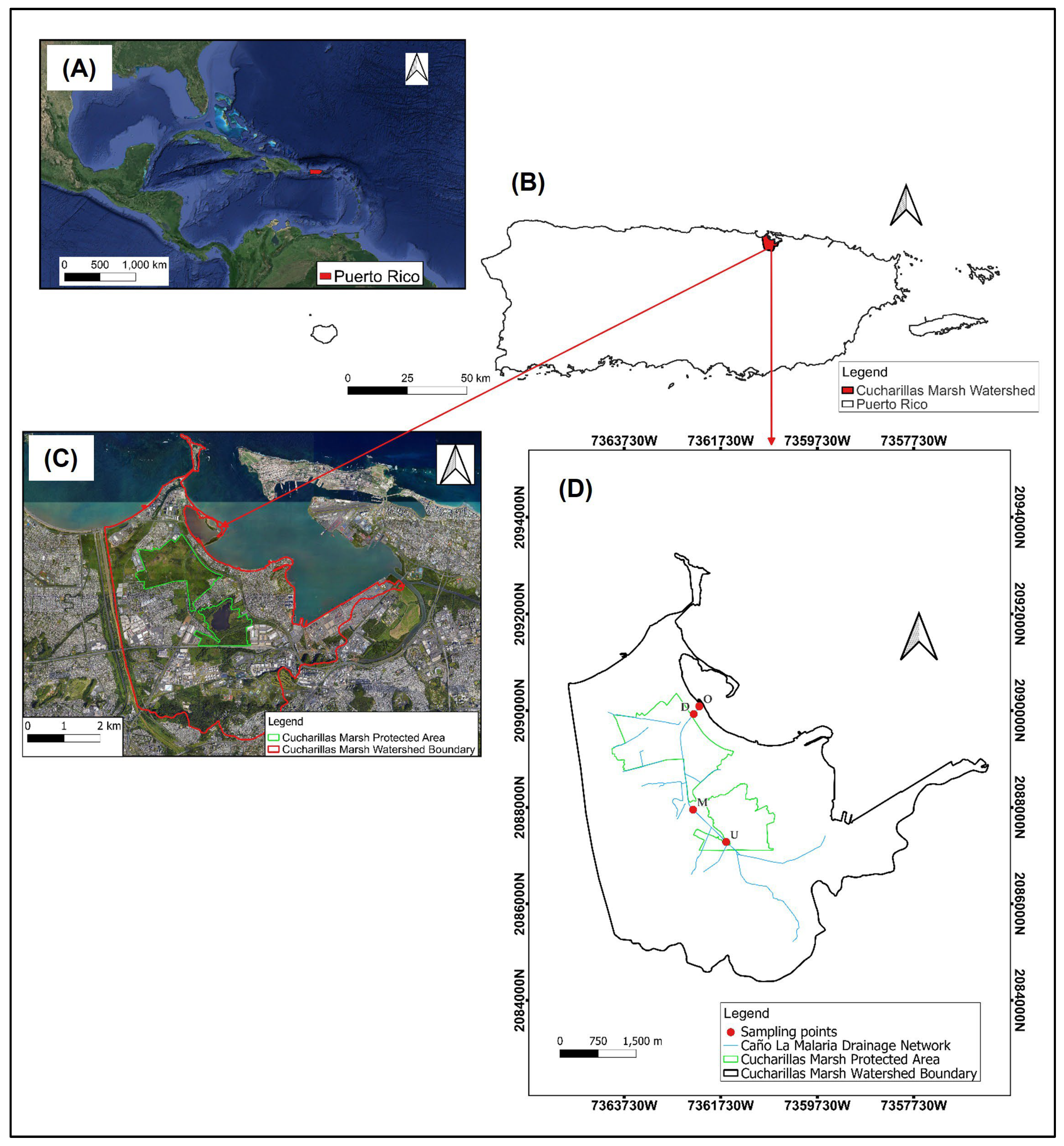

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Design

2.2. Materials and Reagents

2.3. Sample Preparation and Extraction

2.4. GC-MS Instrumental Analysis

2.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Quality Assurance and Quality Control

2.7. Ecological Risk Assessment

| HQwater Range | Ecological Risk Category |

|---|---|

| HQwater < 0.01 | Insignificant |

| 0.01 ≤ HQwater < 0.1 | Low |

| 0.1 ≤ HQwater < 1.0 | Moderate |

| HQwater ≥ 1.0 | High |

3. Results

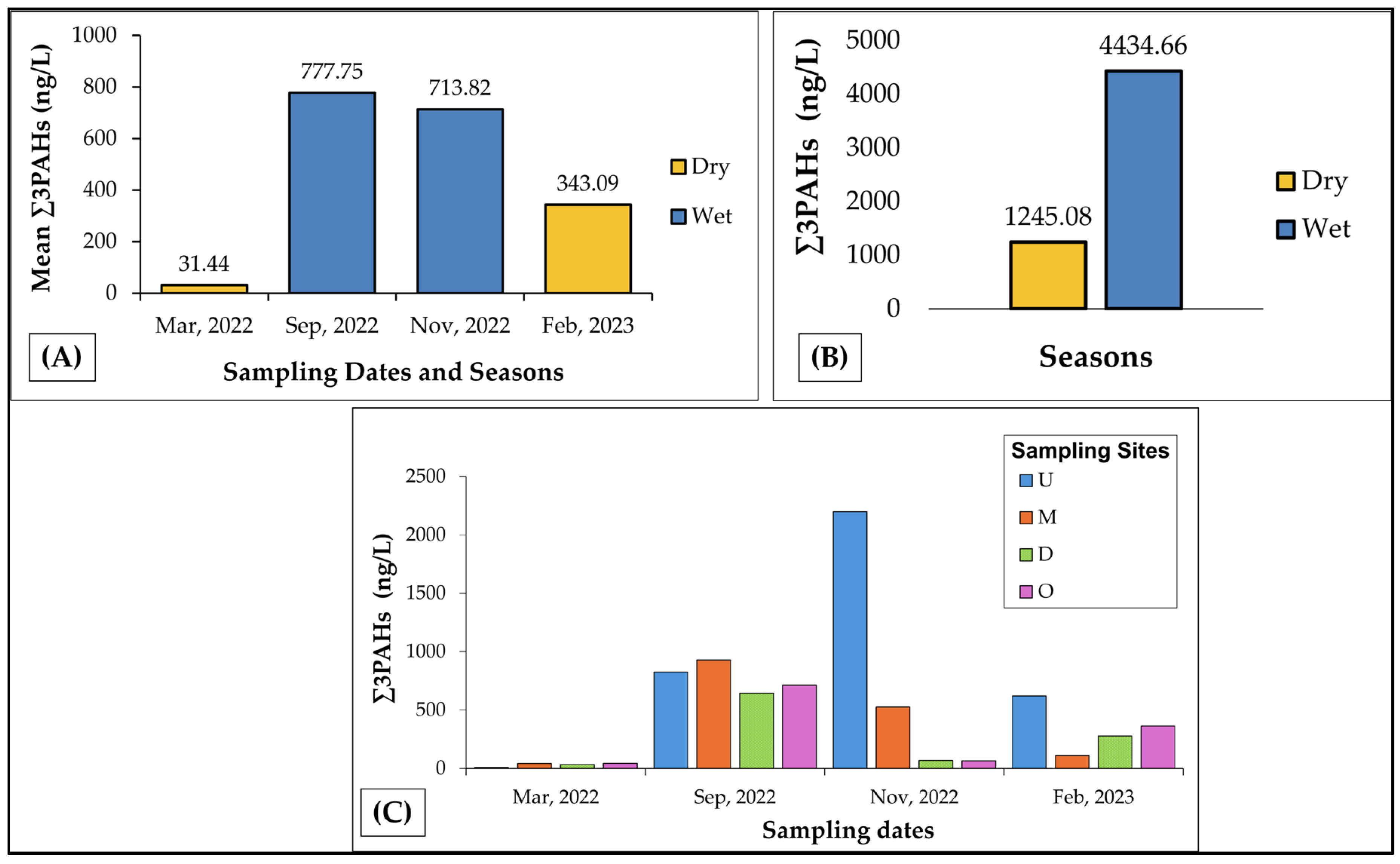

3.1. Spatial and Seasonal Variability in PAH Concentrations

3.3. PAH Sources and Compositional Patterns

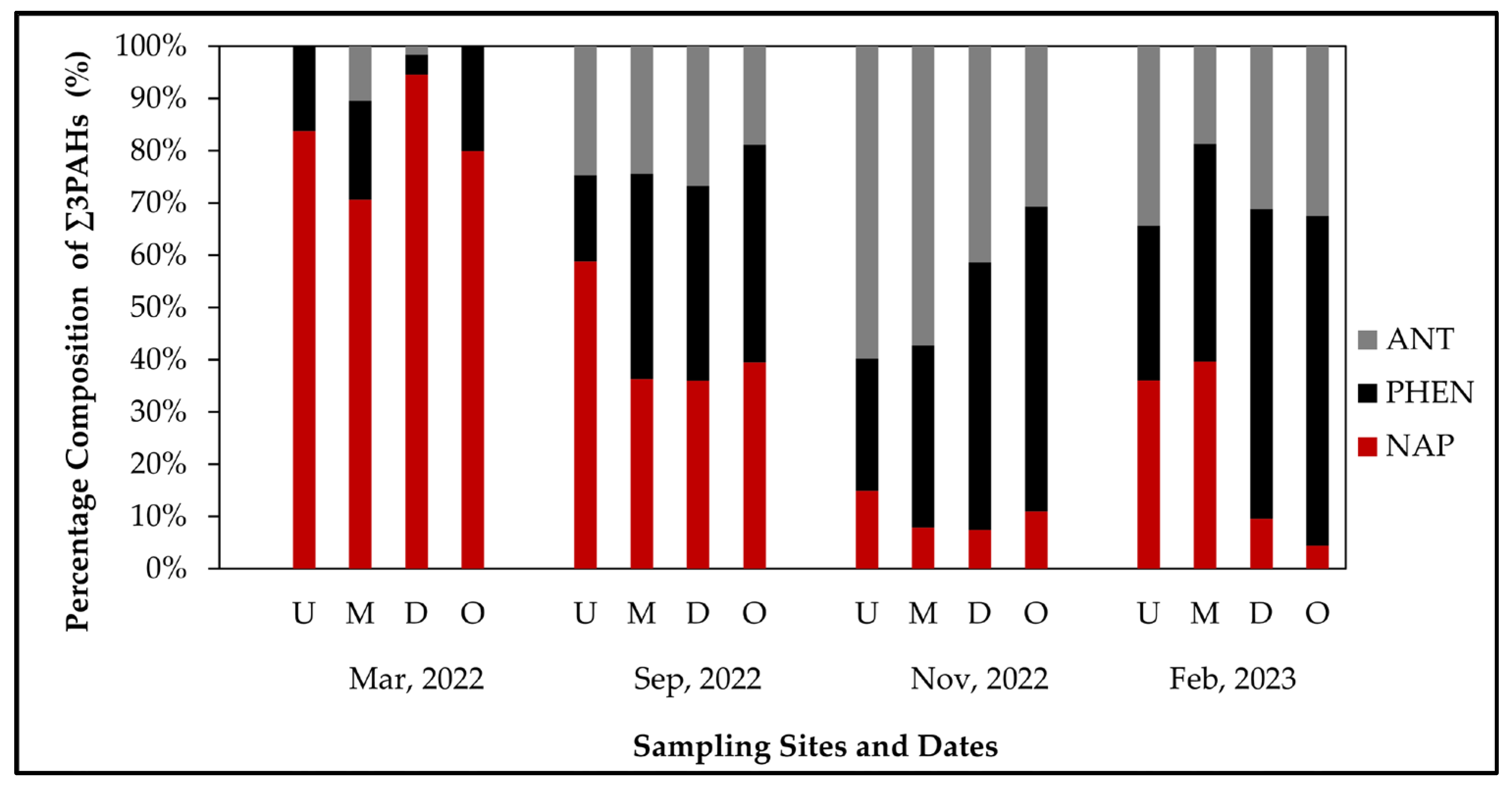

3.3.1. Compositional Patterns

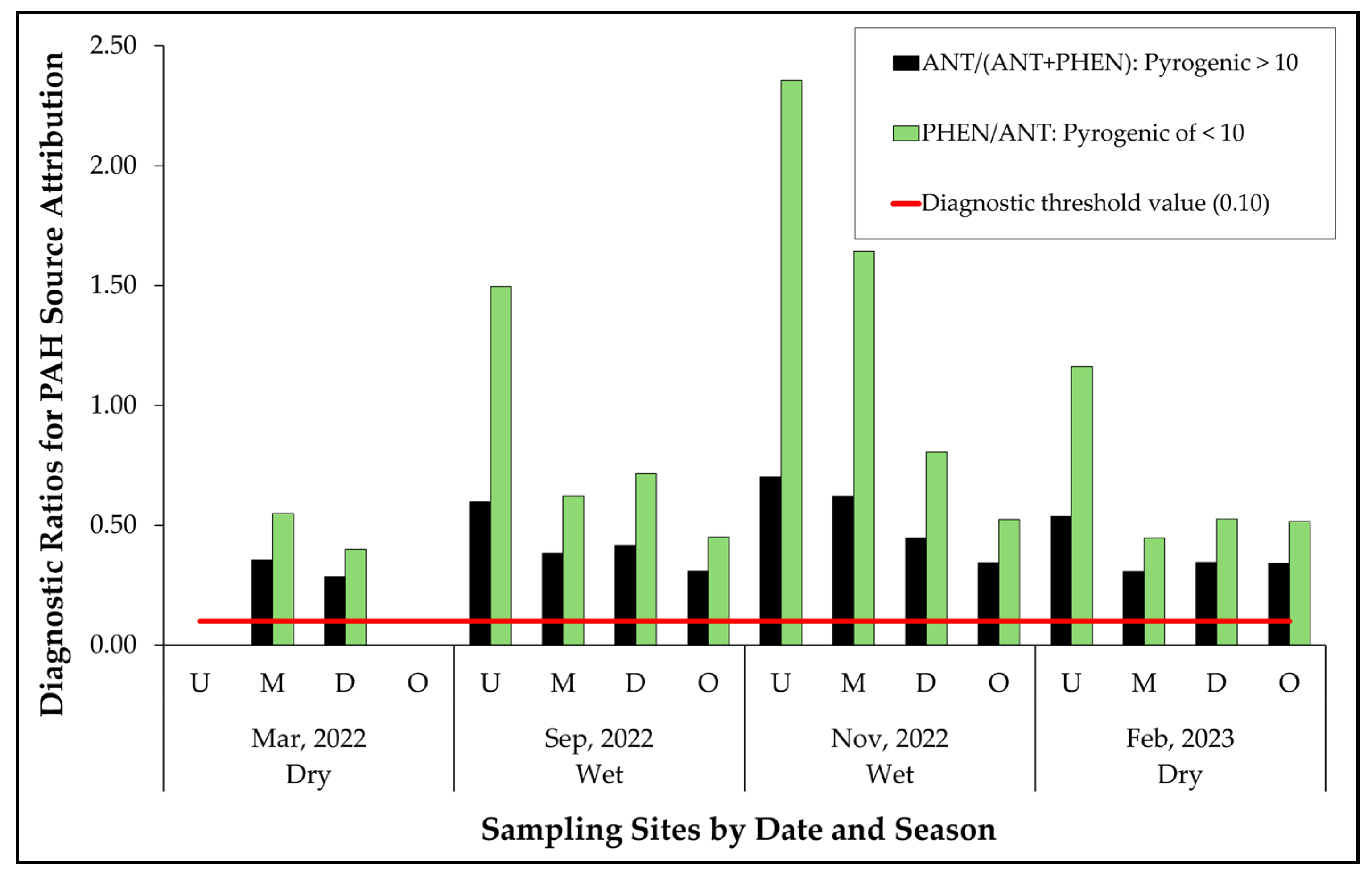

3.3.2. Sources by Diagnostic Ratios

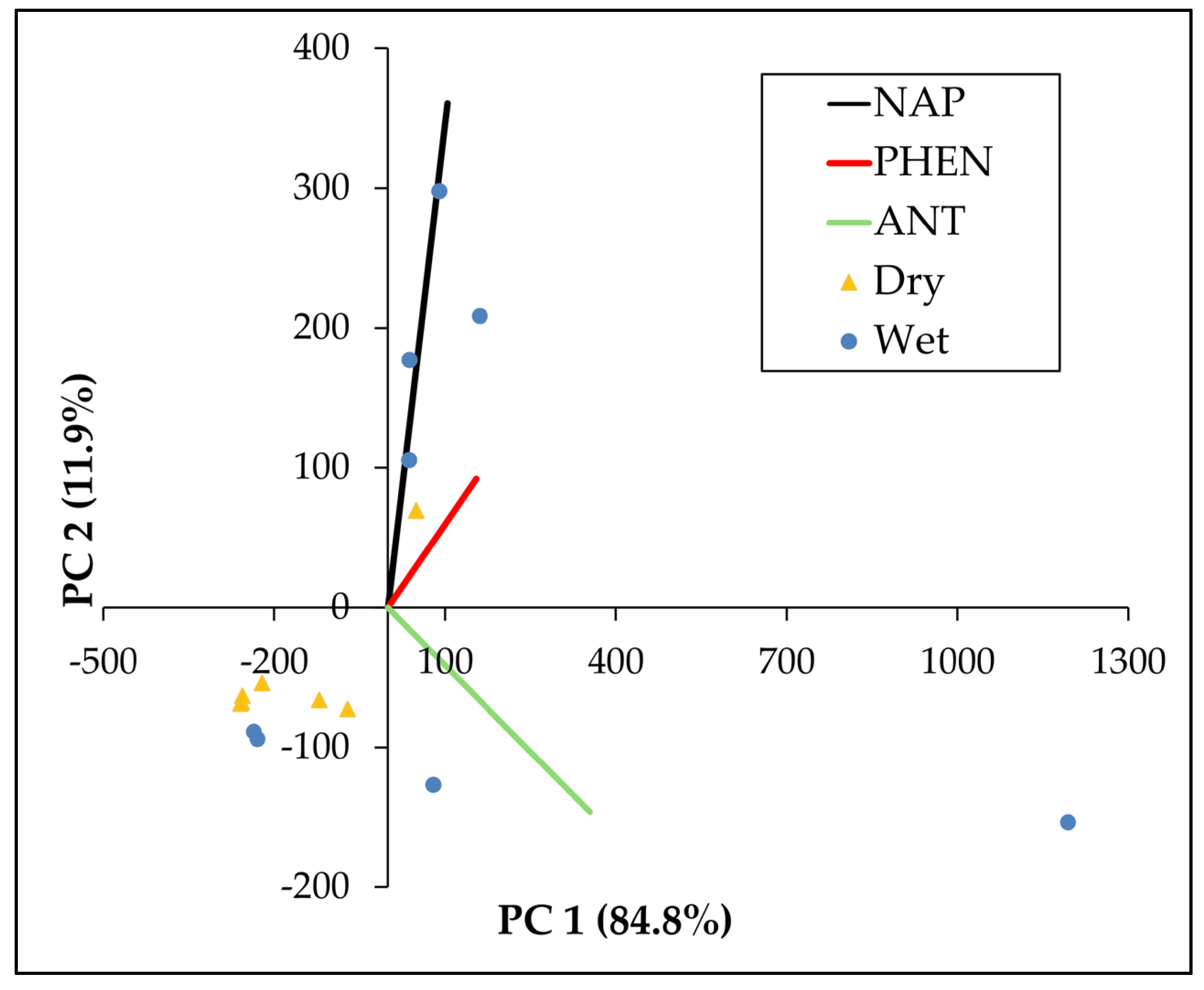

3.3.3. Sources by Principal Component Analysis

3.4. Correlation Patterns

3.5. Ecological Risk Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Seasonal Hydrology on PAH Dynamics

4.2. Spatial Distribution and Attenuation of PAHs

4.3. Source Apportionment of PAHs

4.4. Environmental Benchmarks and Management Recommendations

4.5. Ecological Risk Assessment

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAHs | polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| LMW-PAHs | low molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| HMW-PAHs | high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| NAP | naphthalene |

| PHEN | phenanthrene |

| ANT BaA |

anthracene benzo[a]anthracene |

| Σ3PAHs | sum of three low molecular weight PAHs (naphthalene, phenanthrene, anthracene) |

| DCM | dichloromethane |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| USEPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| ng/L | Nanograms per Liter |

| U | upstream |

| M | midstream |

| D | downstream |

| O | outlet |

| RSD | relative Standard Deviation |

| EU | European Union |

| ND | nondetected |

| ERA | ecological risk assessment |

| HQ | hazard quotient |

| ECwater | environmental concentration in water |

| PNECwater | predicted no-effect concentration in water |

| L(E)C50 | lethal (or effect) concentration for 50% of organisms |

| AF | assessment factor |

References

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S.M. A Review on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Source, Environmental Impact, Effect on Human Health and Remediation. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodu, O.S.; Ojumu, T.V.; Ntwampe, S.K.O.; Amodu, O.S.; Ojumu, T.V.; Ntwampe, S.K.O. Bioavailability of High Molecular Weight Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Using Renewable Resources. In Environmental Biotechnology - New Approaches and Prospective Applications; IntechOpen, 2013 ISBN 978-953-51-0972-3.

- Nahar, A.; Akbor, M.A.; Sarker, S.; Siddique, M.A.B.; Shaikh, M.A.A.; Chowdhury, N.J.; Ahmed, S.; Hasan, M.; Sultana, S. Dissemination and Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Water and Sediment of Buriganga and Dhaleswari Rivers of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaekwe, I.O.; Abba, O. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water: A Review of the Sources, Properties, Exposure Pathways, Bionetwork and Strategies for Remediation. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2022, 10, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; da Rocha, C.C.M.; Franco, C.F.J.; Fontana, L.F.; Pereira Netto, A.D. Seasonal Variation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Concentrations in Urban Streams at Niterói City, RJ, Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 2834–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, M.; T R, P. Critical Review on the Formations and Exposure of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Conventional Hydrocarbon-Based Fuels: Prevention and Control Strategies. Chemosphere 2024, 350, 141005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dat, N.-D.; Chang, M.B. Review on Characteristics of PAHs in Atmosphere, Anthropogenic Sources and Control Technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 609, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.S.B., Astha Bhatia, Gulshan Bhagat, Simran Singh, Salwinder Singh Dhaliwal, Vivek Sharma, Vibha Verma, Rui Yin, Jaswinder PAHs in Terrestrial Environment and Their Phytoremediation. In Bioremediation for Sustainable Environmental Cleanup; CRC Press, 2024 ISBN 978-1-003-27794-1.

- Behera, B.K.; Das, A.; Sarkar, D.J.; Weerathunge, P.; Parida, P.K.; Das, B.K.; Thavamani, P.; Ramanathan, R.; Bansal, V. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Inland Aquatic Ecosystems: Perils and Remedies through Biosensors and Bioremediation. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 212–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.; Abrantes, N. Forest Fires as Drivers of Contamination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons to the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 24, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ali, S.; Debade, X.; Chebbo, G.; Béchet, B.; Bonhomme, C. Contribution of Atmospheric Dry Deposition to Stormwater Loads for PAHs and Trace Metals in a Small and Highly Trafficked Urban Road Catchment. Env. Sci Pollut Res 2017, 24, 26497–26512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awonaike, B.; Lei, Y.D.; Parajulee, A.; Mitchell, C.P.J.; Wania, F. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Quinones in Urban and Rural Stormwater Runoff: Effects of Land Use and Storm Characteristics. ACS EST Water 2021, 1, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojoc, L.; de Castro-Català, N.; de Guzmán, I.; González, J.; Arroita, M.; Besolí-Mestres, N.; Cadena, I.; Freixa, A.; Gutiérrez, O.; Larrañaga, A.; et al. Pollutants in Urban Runoff: Scientific Evidence on Toxicity and Impacts on Freshwater Ecosystems. Chemosphere 2024, 369, 143806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Qamar, Z.; Khan, A.; Waqas, M.; Nawab, J.; Khisroon, M.; Khan, A. Genotoxic Effects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Present in Vehicle-Wash Wastewater on Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon Idella) and Freshwater Mussels (Anodonta Cygnea). Environ. Pollut. 2023, 327, 121513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frapiccini, E.; De Marco, R.; Grilli, F.; Marini, M.; Annibaldi, A.; Prezioso, E.; Tramontana, M.; Spagnoli, F. Anthropogenic Contribution, Transport, and Accumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments of the Continental Shelf and Slope in the Mediterranean Sea. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Li, H.; Kang, Y.; Liu, H.; Huang, X.; Zhang, R.; Yu, K. Bioaccumulation and Trophic Transfer of PAHs in Tropical Marine Food Webs from Coral Reef Ecosystems, the South China Sea: Compositional Pattern, Driving Factors, Ecological Aspects, and Risk Assessment. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shu, Y.; Kuang, Z.; Han, Z.; Wu, J.; Huang, X.; Song, X.; Yang, J.; Fan, Z. Bioaccumulation and Potential Human Health Risks of PAHs in Marine Food Webs: A Trophic Transfer Perspective. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 485, 136946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, S.; Hamilton, P.B.; Wang, C.; Li, C.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, P.; Hua, L.; Wang, X.; Uddin, M.M.; Xu, F. Key Role of Plankton Species and Nutrients on Biomagnification of PAHs in the Micro-Food Chain: A Case Study in Plateau Reservoirs of Guizhou, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 475, 134890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.-K.; Van, T.V. Sources, Distribution and Toxicity of Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Particulate Matter. In Air Pollution; Villanyi, V., Ed.; Sciyo, 2010 ISBN 978-953-307-143-5.

- Tang, L.; Wang, P.; Yu, C.; Jiang, N.; Hou, J.; Cui, J.; Xin, S.; Xin, Y.; Li, M. Adsorption of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Soil and Water on Pyrochars: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Suzuki, N. Toxicities of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons for Aquatic Animals. Int J Env. Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.T.; Konovets, I.M.; Terletskaya, A.V.; Milyukin, M.V.; Lyashenko, A.V.; Shitikova, L.I.; Shevchuk, L.I.; Afanasyev, S.A.; Krot, Y.G.; Zorina-Sakharova, K.Ye.; et al. Contaminants, Mutagenicity and Toxicity in the Surface Waters of Kyiv, Ukraine. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 155, 111153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Junior, F.C.; Felipe, M.B.M.C.; Castro, D.E.F. de; Araújo, S.C. da S.; Sisenando, H.C.N.; Batistuzzo de Medeiros, S.R. A Look beyond the Priority: A Systematic Review of the Genotoxic, Mutagenic, and Carcinogenic Endpoints of Non-Priority PAHs. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 278, 116838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Toxicological Profile for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons 1996.

- Arowojolu, I.M.; Tongu, S.M.; Itodo, A.U.; Sodre, F.F.; Kyenge, B.A.; Nwankwo, R.C. Investigation of Sources, Ecological and Health Risks of Sedimentary Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in River Benue, Nigeria. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 22, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.T.; Achten, C. Time to Say Goodbye to the 16 EPA PAHs? Toward an Up-to-Date Use of PACs for Environmental Purposes. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2015, 35, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, L.H. The Source of U.S. EPA’s Sixteen PAH Priority Pollutants. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2015, 35, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndwabu, S.; Malungana, M.; Mahlambi, P. Efficiency Comparison of Extraction Methods for the Determination of 11 of the 16 USEPA Priority Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water Matrices: Sources of Origin and Ecological Risk Assessment. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2024, 20, 1598–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Lu, Z.; Sanganyado, E.; Wang, Z.; Du, J.; Gao, X.; Gan, Z.; Wu, J. Trophic Transfer of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Marine Mammals Based on Isotopic Determination. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875, 162531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Song, Y.; He, F.; Jing, M.; Tang, J.; Liu, R. A Review of Human and Animals Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Health Risk and Adverse Effects, Photo-Induced Toxicity and Regulating Effect of Microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephansen, D.A.; Arias, C.A.; Brix, H.; Fejerskov, M.L.; Nielsen, A.H. Relationship between Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments and Invertebrates of Natural and Artificial Stormwater Retention Ponds. Water 2020, 12, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyo-Ita, I.; Nkom ,Patience Y.; Ugim ,Samuel U.; Bassey ,Francisca I.; and Oyo-Ita, O.E. Seasonal Changes of PAHs in Water and Suspended Particulate Matter from Cross River Estuary, SE Nigeria in Response to Human-Induced Activity and Hydrological Cycle. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2022, 42, 5456–5473. [CrossRef]

- Alikhani, S.; Nummi, P.; Ojala, A. Urban Wetlands: A Review on Ecological and Cultural Values. Water 2021, 13, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough, K.L.; Dickhut, R.M. Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Input to Urban Wetlands in Relation to Adjacent Land Use. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettoof, D.C.; Bateman, P.W.; Aubret, F.; Gagnon, M.M. The Broad-Scale Analysis of Metals, Trace Elements, Organochlorine Pesticides and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Wetlands Along an Urban Gradient, and the Use of a High Trophic Snake as a Bioindicator. Arch Env. Contam Toxicol 2020, 78, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ren, G.; Ma, X.; Zhou, B.; Yuan, D.; Liu, H.; Wei, Z. Presence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons among Multi-Media in a Typical Constructed Wetland Located in the Coastal Industrial Zone, Tianjin, China: Occurrence Characteristics, Source Apportionment and Model Simulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayanand, M.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Subramanian, R.; Issac, P.K.; Nasr, M.; Khoo, K.S.; Rajagopal, R.; Greff, B.; Wan Azelee, N.I.; Jeon, B.-H.; et al. Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Water Environment: A Review on Toxicity, Microbial Biodegradation, Systematic Biological Advancements, and Environmental Fate. Environ. Res. 2023, 227, 115716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, A.; Soman, V.; R, A.K.; A, R.; K, H.R. Sources, Toxicity, Fate and Transport of Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Aquatic Environment: A Review. Environ. Forensics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Xu, J.; Shang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xie, H.; Kong, Q.; Wang, Q. Application of Constructed Wetlands in the PAH Remediation of Surface Water: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 780, 146605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayinka, O.O.; Adewusi, A.A.; Olarenwaju, O.O.; Aladesida, A.A. Concentration of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Estimated Human Health Risk of Water Samples Around Atlas Cove, Lagos, Nigeria. J. Health Pollut. 2018, 8, 181210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.N.; Mariz, C.F., Jr.; de Melo Alves, M.K.; Cavalcanti, M.G.N.; de Melo, T.J.B.; de Arruda-Santos, R.H.; Zanardi-Lamardo, E.; Carvalho, P.S.M. Contamination and Toxicity of Surface Waters Along Rural and Urban Regions of the Capibaribe River in Tropical Northeastern Brazil. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 3063–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Chen, C.S.; Wang, Z.-X.; Tien, C.-J. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in 30 River Ecosystems, Taiwan: Sources, and Ecological and Human Health Risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makobe, S.; Seopela, M.P.; Ambushe, A.A. Seasonal Variations, Source Apportionment, and Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Sediments from Klip River, Johannesburg, South Africa. Env. Monit Assess 2025, 197, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Olivero-Verbel, J.; Corada-Fernández, C.; Lara-Martín, P.A.; Juan-García, A. Emerging Contaminants and Priority Substances in Marine Sediments from Cartagena Bay and the Grand Marsh of Santa Marta (Ramsar Site), Colombia. Env. Monit Assess 2021, 193, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhang, C.; Xu, X.; Jin, R.; Li, D.; Christakos, G.; Xiao, X.; He, J.; Agusti, S.; Duarte, C.M.; et al. Underestimated PAH Accumulation Potential of Blue Carbon Vegetation: Evidence from Sedimentary Records of Saltmarsh and Mangrove in Yueqing Bay, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 152887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menone, M.L.; Díaz-Jaramillo, M.; Mitton, F.; Garanzini, D.S.; Costa, P.G.; Lupi, L.; Lukaszewicz, G.; Gonzalez, M.; Jara, S.; Miglioranza, K.S.B.; et al. Distribution of PAHs and Trace Elements in Spartina Densiflora and Associated Sediments from Low to Highly Contaminated South American Estuarine Saltmarshes. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 842, 156783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, M.M.; Bhuiyan, M.K.A.; Amran, M.I.U.A.; Cabral, A.C.; Garcia, M.R.D. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Pollution in Mangrove Ecosystems: Global Synthesis and Future Research Directions. Rev Env. Sci Biotechnol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Sun, K.; Wen, Z. Spatiotemporal Distribution, Bioaccumulation, and Ecological and Human Health Risks of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Surface Water: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, J.; Singhvi, R.; Kumar, K.; Jain, V.K.; Taneja, A. Seasonal Variation and Sources of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Indoor and Outdoor Air in a Semi Arid Tract of Northern India. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2012, 12, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, G.; Liu, X.; Cui, H.; Han, J. Sources, Transport and Fate of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a Typical River-Estuary System in the North China: From a New Perspective of PAHs Loading. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 214, 117692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus, F.; Pereira, J.L.; Campos, I.; Santos, M.; Ré, A.; Keizer, J.; Nogueira, A.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Abrantes, N.; Serpa, D. A Review on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Distribution in Freshwater Ecosystems and Their Toxicity to Benthic Fauna. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Peng, S.; Lai, Z.; Mai, Y. Seasonal Variation of Temperature Affects HMW-PAH Accumulation in Fishery Species by Bacterially Mediated LMW-PAH Degradation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 853, 158617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, G.; Bian, D.; Zou, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, F. Pollution and Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Urban Rivers in a Northeastern Chinese City: Implications for Continuous Rainfall Events. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, R.M.; Gómez-Gómez, F. Synoptic Survey of Water Quality and Bottom Sediments, San Juan Bay Estuary System, Puerto Rico, December 1994-July 1995; U.S. Geological Survey ; Branch of Information Services: Guaynabo, PR, 1998;

- Branoff, B.; Cuevas, E.; Hernández, E. Assessment of Urban Coastal Wetlands Vulnerability to Hurricanes in Puerto Rico; Department of Natural Resources of Puerto Rico: San Juan, PR, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Cintrón, A. Assessment of Land Use Land Cover Patterns Influence on Toxic Metals Distribution in Freshwater Sediments a Case Study – Ciénaga Las Cucharillas, Puerto Rico. Ph.D., 2025.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency 02/03/2003: EPA Proposes to Fine the Municipality of Cataño for Raw Sewage Discharges Available online:. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/archive/epapages/newsroom_archive/newsreleases/d568d21c3a4bd717852571630060f20d.html(accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Mejías, C.L.; Carlos Musa, J.; Otero, J. Exploratory Evaluation of Retranslocation and Bioconcentration of Heavy Metals in Three Species of Mangrove at Las Cucharillas Marsh, Puerto Rico. J. Trop. Life Sci. 2013, 3, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldarondo-Torres, J.X.; Samara, F.; Mansilla-Rivera, I.; Aga, D.S.; Rodríguez-Sierra, C.J. Trace Metals, PAHs, and PCBs in Sediments from the Jobos Bay Area in Puerto Rico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 1350–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjeltema, J.; Stoskopf, M.; Shea, D.; De Voe, R. Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Contamination of Breeding Pools Utilized by the Puerto Rican Crested Toad, Peltophryne Lemur. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 2012, 309853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pait, A.S.; Whitall, D.R.; Dieppa, A.; Newton, S.E.; Brune, L.; Caldow, C.; Mason, A.L.; Apeti, D.A.; Christensen, J.D. Characterization of Organic Chemical Contaminants in Sediments from Jobos Bay, Puerto Rico. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 5065–5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitall, D.; Mason, A.; Pait, A.; Brune, L.; Fulton, M.; Wirth, E.; Vandiver, L. Organic and Metal Contamination in Marine Surface Sediments of Guánica Bay, Puerto Rico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 80, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo-Santiago, J.I. Evaluación de Plantas Con Potencial Fitoremediador de Hidrocarburos Aromaticos Policíclicos de La Ciénaga Las Cucharrillas, Universidad Metropolitana: San Juan, PR, 2008.

- Sturla Irizarry, S.M.; Cathey, A.L.; Zimmerman, E.; Rosario Pabón, Z.Y.; Huerta Montañez, G.; Vélez Vega, C.M.; Alshawabkeh, A.N.; Cordero, J.F.; Meeker, J.D.; Watkins, D.J. Prenatal Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Exposure and Neurodevelopment among Children in Puerto Rico. Chemosphere 2024, 366, 143468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.J.; Zayas, H.R.T.; Welton, M.; Vega, C.M.V.; Pabón, Z.R.; Arroyo, L.D.A.; Cathey, A.L.; Cordero, N.R.C.; Alshawabkeh, A.; Cordero, J.F.; et al. Changes in Exposure to Environmental Contaminants in the Aftermath of Hurricane Maria among Pregnant Women in Northern Puerto Rico. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramlich, K.C.; Monteiro, F.C.; Carreira, R. da S. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on the Atlantic Coast of South America and the Caribbean: A Systematic Literature Review on Biomonitoring Coastal Regions Employing Marine Invertebrates. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 78, 103792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Pantojas, G.M.; Vélez, V.; Zayas, B.; Malavé Zayas, K. EVALUACIÓN DE LA CALIDAD MICROBIOLÓGICA DEL AGUA DEL CAÑO LA MALARIA Y EL RIESGO A LAS COMUNIDADES. Perspect. En Asun. Ambient. 2014, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.A.; Enfield, D.B.; Chen, A.A. Influence of the Tropical Atlantic versus the Tropical Pacific on Caribbean Rainfall. J. Geophys. Res. : Ocean. 2002, 107, 10–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Valcárcel, Á.; Harbor, J.; González-Avilés, C.; Torres-Valcárcel, A. Impacts of Urban Development on Precipitation in the Tropical Maritime Climate of Puerto Rico. Climate 2014, 2, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency Method 610: Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, 1984;

- GIS Puerto Rico Geodatos—Sistemas de Información Geográfica (GIS) Available online: https://gis.pr.gov/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- European Union Reference Laboratories Guidance Document on the Estimation of LOD and LOQ for Measurements in the Field of Contaminants in Feed and Food; European Union Reference laboratory: Freiburg, Germany, 2016;

- Gao, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Fan, B.; Li, W.; Liu, Z. Exposure and Ecological Risk of Phthalate Esters in the Taihu Lake Basin, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 171, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Qi, Y.; Guan, X.; Zhao, C.; Wang, H.; Zhu, S.; Fu, G.; Zhu, J.; He, J. Distribution, Sources, and Ecological Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Tidal Creek Water of Coastal Tidal Flats in the Yellow River Delta, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, R. Derivation of Predicted No Effect Concentration and Ecological Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Musks Tonalide and Galaxolide in Sediment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 229, 113093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Pang, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, X.; Fu, K.; Zhang, T.; Han, J.; Yang, L.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, S. Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Pesticides in Danjiangkou Reservoir and Evaluation of Ecological Risk. Toxics 2024, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, A.M.; Moore, M.K.; Warner, K.A.; Stadig, S.R.; Deeds, J.R. Evaluation of Variation within the Barcode Region of Cytochrome c Oxidase I (COI) for the Detection of Commercial Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Blue Crab) Products of Non-US Origin. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabourin, T.D. Respiratory and Circulatory Responses of the Blue Crab to Naphthalene and the Effect of Acclimation Salinity. Aquat. Toxicol. 1982, 2, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency ECOTOX Knowledgebase Available online:. Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Grmasha, R.A.; Abdulameer, M.H.; Stenger-Kovács, C.; Al-sareji, O.J.; Al-Gazali, Z.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Meiczinger, M.; Hashim, K.S. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Surface Water and Sediment along Euphrates River System: Occurrence, Sources, Ecological and Health Risk Assessment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 187, 114568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Nhon, N.T.T.; Hai, H.T.N.; Chi, N.D.T.; Hien, T.T. Characteristics of Microplastics and Their Affiliated PAHs in Surface Water in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Polymers 2022, 14, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Bery, C.C.; dos Santos Gois, A.R.; Silva, B.S.; da Silva Soares, L.; Santos, L.G.G.V.; Fonseca, L.C.; da Silva, G.F.; Freitas, L.S.; Santos, E.; Alexandre, M.R.; et al. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Surface Water of Rivers in Sergipe State, Brazil: A Comprehensive Analysis of Sources, Spatial and Temporal Variation, and Ecotoxicological Risk. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 202, 116370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, M.; Zhao, Y.; Rina, S.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, J. Residues, Potential Source and Ecological Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Surface Water of the East Liao River, Jilin Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 886, 163977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Zhao, D.; Chen, X.; Zheng, L.; Li, C.; Ren, M. Distribution, Source and Ecological Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Groundwater in a Coal Mining Area, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodora CIUCURE, C.; Geana, E.-I.; Lidia CHITESCU, C.; Laurentiu BADEA, S.; Elena IONETE, R. Distribution, Sources and Ecological Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Waters and Sediments from Olt River Dam Reservoirs in Romania. Chemosphere 2023, 311, 137024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Lin, L.; He, J.; Pan, X.; Wu, X.; Yang, Y.; Jing, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yin, G. PAHs in the Surface Water and Sediments of the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Han River, China: Occurrence, Source, and Probabilistic Risk Assessment. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 164, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambade, B.; Sethi, S.S.; Giri, B.; Biswas, J.K.; Bauddh, K. Characterization, Behavior, and Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Estuary Sediments. Bull Env. Contam Toxicol 2022, 108, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Bao, K.; Zhao, K.; Neupane, B.; Gao, C. A Baseline Study of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Distribution, Source and Ecological Risk in Zhanjiang Mangrove Wetlands, South China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iloma, R.U.; Okpara ,Kingsley Ezechukwu; Tesi ,Godswill Okeoghene; and Techato, K. Spatio-Temporal Distribution, Source Apportionment, Ecological and Human Health Risks Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sombreiro River Estuary, Niger Delta, Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2024, 0, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; der Beek, T. aus; Zhang, J.; Schmid, C.; Schüth, C. Characterizing Spatiotemporal Variations of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Taihu Lake, China. Env. Monit Assess 2022, 194, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezekwe, C.; Onwudiegwu, C.A.; Uzoekwe, S.A. Risk Assessment and Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water and Sediments Along Ibelebiri Axis of Kolo Creek, Ogbia Local Government Area, Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. Chem. Afr. 2025, 8, 1199–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. Distribution, Sources, and Ecological Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Surface Water in the Coal Mining Area of Northern Shaanxi, China. Env. Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 50496–50508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshmvahm, H.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Zarei, M.; Esmaeili, H.R.; Hooda, P.S. Investigation of the Concentration, Origin and Health Effects of PAHs in the Anzali Wetland: The Most Important Coastal Freshwater Wetland of Iran. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 193, 115191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhradini, S.S.; Moore, F.; Keshavarzi, B.; Lahijanzadeh, A. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Water and Sediment of Hoor Al-Azim Wetland, Iran: A Focus on Source Apportionment, Environmental Risk Assessment, and Sediment-Water Partitioning. Env. Monit Assess 2019, 191, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashayeri, N.Y.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Kersten, M.; Yazdi, M.; Lahijanzadeh, A.R. Presence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments and Surface Water from Shadegan Wetland – Iran: A Focus on Source Apportionment, Human and Ecological Risk Assessment and Sediment-Water Exchange. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 148, 1054–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojiri, A.; Zhou, J.L.; Ohashi, A.; Ozaki, N.; Kindaichi, T. Comprehensive Review of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water Sources, Their Effects and Treatments. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696, 133971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, L.; Yu, Y.; Tan, L.; Wang, Z.; Suo, S.; Liu, C.; Qin, Y.; Peng, X.; Lu, H.; et al. Distribution, Source, Risk and Phytoremediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Typical Urban Landscape Waters Recharged by Reclaimed Water. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 330, 117214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, C.-H.; Khim, J.S.; Kannan, K.; Villeneuve, D.L.; Senthilkumar, K.; Giesy, J.P. Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-Dioxins (PCDDs), Dibenzofurans (PCDFs), Biphenyls (PCBs), and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and 2,3,7,8-TCDD Equivalents (TEQs) in Sediment from the Hyeongsan River, Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2004, 132, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarawou, T.; Erepamowei, Y.; Aigberua, A. Determination of Sources, Spatial Variability, and Concentration of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Surface Water and Sediment of Imiringi River. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2021, 9, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Huang, G.-B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Liu, Z.-X.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, S.-Y.; Xu, D.-D.; Liu, H.-L.; Mo, S.-P.; et al. Composition Characteristics, Source Analysis and Risk Assessment of PAHs in Surface Waters of Lipu. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 490, 137733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambade, B.; Sethi, S.S.; Kurwadkar, S.; Kumar, A.; Sankar, T.K. Toxicity and Health Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Surface Water, Sediments and Groundwater Vulnerability in Damodar River Basin. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 13, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Han, M.; Cao, X.; Cheng, X.; Yang, S.; Li, S.; Sun, C.; He, H. Sedimentary Spatial Variation, Source Identification and Ecological Risk Assessment of Parent, Nitrated and Oxygenated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in a Large Shallow Lake in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Souza, M.R.R.; Vilela Junior, A.R.; Soares, L.S.; Frena, M.; Alexandre, M.R. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH) in Superficial Water from a Tropical Estuarine System: Distribution, Seasonal Variations, Sources and Ecological Risk Assessment. Mar Pollut Bull 2018, 127, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Qu, C.; Sun, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Qi, S. Multimedia Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Wang Lake Wetland, China. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 306, 119358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, K.; Xie, Z.; Zhi, L.; Wang, Z.; Qu, C. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Water Bodies of Dong Lake and Tangxun Lake, China: Spatial Distribution, Potential Sources and Risk Assessment. Water 2023, 15, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areguamen, O.I.; Calvin, N.N.; Gimba, C.E.; Okunola, O.J.; Elebo, A. Seasonal Assessment of the Distribution, Source Apportionment, and Risk of Water-Contaminated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs). Env. Geochem Health 2023, 45, 5415–5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunker, M.B.; Macdonald, R.W.; Vingarzan, R.; Mitchell, R.H.; Goyette, D.; Sylvestre, S. PAHs in the Fraser River Basin: A Critical Appraisal of PAH Ratios as Indicators of PAH Source and Composition. Org. Geochem. 2002, 33, 489–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Jing, Z.; Guo, F.; Jia, J.; Jiang, Y.; Cai, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, H.; Song, X. Spatial Variation Characteristics of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Their Derivatives in Surface Water of Suzhou City: Occurrence, Sources, and Risk Assessment. Toxics 2025, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Hou, L.; Li, X.; Yin, G.; Sun, P.; Yang, J.; Wei, X.; He, Y.; Zheng, D. Geographical Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Estuarine Sediments over China: Human Impacts and Source Apportionment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 768, 145279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, N.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Tavakol, T.; Lahijanzadeh, A.R.; Jaafarzadeh, N.; Kermani, M. Ecological and Human Health Hazards of Heavy Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Road Dust of Isfahan Metropolis, Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 505, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grmasha, R.A.; Stenger-Kovács, C.; Bedewy, B.A.H.; Al-sareji, O.J.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Meiczinger, M.; Hashim, K.S. Ecological and Human Health Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH) in Tigris River near the Oil Refineries in Iraq. Environ. Res. 2023, 227, 115791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Ma, T.; Cao, X.; Li, W.; Zhu, F.; He, H.; Sun, C.; Yang, S.; Li, S.; Xian, Q. Occurrence, Partition Behavior, Source and Ecological Risk Assessment of Nitro-PAHs in the Sediment and Water of Taige Canal, China. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 124, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azah, E.; Kim, H.; Townsend, T. Source of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon in Roadway and Stormwater System Maintenance Residues. Env. Earth Sci 2015, 74, 3029–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, J.P.; Dash, S.; Sandil, S.; Chaminda, T.; Mahlknecht, J.; Kumar, M. Long-Range Transport of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Metals in High Altitude Lacustrine Environments of the Eastern Himalayas: Speciation, and Source Apportionment Perspectives. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 3400–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrahan, P.; Lupu, A.; Leibovici, E.; Ninio, S. BTEX and PAH Contributions to Lake Kinneret Water: A Seasonal-Based Study of Volatile and Semi-Volatile Anthropogenic Pollutants in Freshwater Sources. Env. Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 61145–61159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Lin, T.; Sun, X.; Wu, Z.; Tang, J. Spatiotemporal Distribution and Particle–Water Partitioning of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Bohai Sea, China. Water Res. 2023, 244, 120440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency Freshwater Screening Benchmarks; United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2006;

- Baumard, P.; Budzinski, H.; Michon, Q.; Garrigues, P.; Burgeot, T.; Bellocq, J. Origin and Bioavailability of PAHs in the Mediterranean Sea from Mussel and Sediment Records. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 1998, 47, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yao, X.; Zang, S.; Wan, L.; Sun, L. A National-Scale Study of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Surface Water: Levels, Sources, and Carcinogenic Risk. Water 2024, 16, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, J. Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs); Ministry of the Environment, Land and Parks: British Columbia, Canada, 1993.

- Directive 2013/39/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 August 2013 Amending Directives 2000/60/EC and 2008/105/EC as Regards Priority Substances in the Field of Water Policy Text with EEA Relevance; 2013; Vol. 226.

- Sajid, M.; Nazal, M.K.; Ihsanullah, I. Novel Materials for Dispersive (Micro) Solid-Phase Extraction of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Environmental Water Samples: A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1141, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, N.K. Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs); Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Province of British Columbia: British Columbia, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tillmanns, A.R.; McGrath, J.A.; Di Toro, D.M. International Water Quality Guidelines for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Advances to Improve Jurisdictional Uptake of Guidelines Derived Using The Target Lipid Model. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2024, 43, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Fan, B.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Cui, L.; Liu, Z. Development of Human Health Ambient Water Quality Criteria of 12 Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH) and Risk Assessment in China. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Liu, F.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yu, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R. Occurrence, Distribution, Sources, and Bioaccumulation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Multi Environmental Media in Estuaries and the Coast of the Beibu Gulf, China: A Health Risk Assessment through Seafood Consumption. Env. Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 52493–52506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, A.Q.; Tran, K.H.; Vu, Y.H.T.; Nguyen, T.P.T.; Nguyen, H.D.; Nguyen, H.T.; Hoang, N.; Van Vu, T.; Tran, T.M. Comprehensive Investigation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Multiple Water Types from Hanoi, Vietnam: Contamination Characteristics, Influencing Factors, and Ecological Risks. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Yang, B.; Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Qadeer, A. Levels, Sources and Risk Assessment of PAHs in Multi-Phases from Urbanized River Network System in Shanghai. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundo, R.; Matsunaka, T.; Iwai, H.; Ochiai, S.; Nagao, S. Environmental Processes and Fate of PAHs at a Shallow and Enclosed Bay: West Nanao Bay, Noto Peninsula, Japan. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 184, 114105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xing, X.; Yu, H.; Du, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Li, X.; Zou, Y.; Shi, M.; Liu, W.; et al. Fate of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAHs) in Urban Lakes under Hydrological Connectivity: A Multi-Media Mass Balance Approach. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 366, 125556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, E.; Cardaci, A.; Pietrini, I.; Fusini, D.; Conte, A.; De Folly D’Auris, A.; Grifoni, M.; Pedron, F.; Barbafieri, M.; Petruzzelli, G.; et al. Nature-Based Solutions for Restoring an Agricultural Area Contaminated by an Oil Spill. Plants 2022, 11, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. A Systematic Review of the Scientific Literature on Pollutant Removal from Stormwater Runoff from Vacant Urban Lands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, A.; Matta, A.; Moghadam, S.V.; Dessouky, S.; Hutchinson, J.; Kapoor, V. Field Performance of Two Stormwater Bioretention Systems for Treating Heavy Metals and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons from Urban Runoff. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 123080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoveidadianpour, Z.; Doustshenas, B.; Alava, J.J.; Savari, A.; Karimi Organi, F. Environmental and Human Health Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Musa Estuary (Northwest of Persian Gulf), Iran. J. Sea Res. 2023, 191, 102335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.V.; Sullivan, T. The Role of Water Quality Monitoring in the Sustainable Use of Ambient Waters. One Earth 2022, 5, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerga, B. Integrated Watershed Management: A Review. Discov Sustain 2025, 6, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.; Rhodes, C.; Shah, F.A. Upstream Water Resource Management to Address Downstream Pollution Concerns: A Policy Framework with Application to the Nakdong River Basin in South Korea. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, V.; Moodley, B. Assessment of the Impact of Reforestation on Soil, Riparian Sediment and River Water Quality Based on Polyaromatic Hydrocarbon Pollutants. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 324, 116331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ávila, C.; Rao, B.; Hussain, T.; Zhou, H.; Pitt, R.; Colvin, M.; Hayman, N.; DeMyers, M.; Reible, D. Particle Size-Based Evaluation of Stormwater Control Measures in Reducing Solids, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs). Water Res. 2025, 277, 123299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.K.; Binelli, A.; Chatterjee, M.; Bhattacharya, B.D.; Parolini, M.; Riva, C.; Jonathan, M.P. Distribution and Ecosystem Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Core Sediments of Sundarban Mangrove Wetland, India. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2012, 32, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okbah, M.A.; Nassar, M.; Ibrahim, M.S.; El-Gammal, M.I. Environmental Study of Some Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Edku Wetland Waters, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2024, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, J.; Shi, X.; You, X.; Cao, Z. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Water from Three Estuaries of China: Distribution, Seasonal Variations and Ecological Risk Assessment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 109, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozarpour, R.; Bakhtiari, A.R.; Gorabi, F.G.; Azimi, A. Assessing Ecological and Health Risks of PAH Compounds in Anzali Wetland: A Weight of Evidence Perspective. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 220, 118428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ololade, I.A.; Lajide, L.; Amoo, I.A. Occurrence and Toxicity of Hydrocarbon Residues in Crab (Callinectes Sapidus) from Contaminated Site. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2008, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pie, H.V.; Schott, E.J.; Mitchelmore, C.L. Investigating Physiological, Cellular and Molecular Effects in Juvenile Blue Crab, Callinectus Sapidus, Exposed to Field-Collected Sediments Contaminated by Oil from the Deepwater Horizon Incident. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 532, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, M.A.; Weinstein, M.P.; Lohmann, R. Trophodynamic Behavior of Hydrophobic Organic Contaminants in the Aquatic Food Web of a Tidal River. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 12533–12542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Hu, P.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Sun, J. Ecological and Health Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Surface Water from Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yellow River. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2016, 36, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeh, C.T.; Nduka, J.K.; Omokpariola, D.O.; Morah, J.E.; Mmaduakor, E.C.; Okoye, N.H.; Lilian, E.-E.I.; Kalu, I.F. Ecological Pollution and Health Risk Monitoring Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Heavy Metals in Surface Water, Southeastern Nigeria. Env. Anal Health Toxicol 2023, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Date | Site | NAP Mean (ng/L)±SD |

Range | PHEN Mean (ng/L)±SD |

Range | ANT Mean (ng/L)±SD |

Range | Σ3PAHs (ng/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar, 2022 | U | 6.20±0.00 | ND—6.20 | 1.20±0.00 | ND—1.20 | ND | ND | 7.40 |

| M | 30.13±28.46 | 10.00—50.25 | 8.10±1.91 | 6.75—9.45 | ND | ND | 38.23 | |

| D | 30.50±26.38 | 11.85—49.15 | 1.25±0.00 | ND—1.25 | 0.50±0.00 | ND—0.50 | 32.25 | |

| O | 34.73±32.99 | 11.40—58.05 | 8.70±0.00 | ND—8.70 | ND | ND | 43.43 | |

| Sep, 2022 | U | 485.10±231.93 | 321.10—649.10 | 135.87±48.11 | 85.65—181.55 | 203.40±0.00 | 114.50—292.30 | 824.37 |

| M | 337.60±32.39 | 308.60—372.55 | 364.72±47.34 | 321.55—415.35 | 227.25±109.39 | 149.90—304.60 | 929.57 | |

| D | 232.12±29.02 | 203.80—261.80 | 240.47±33.11 | 218.50—278.55 | 171.95±116.67 | 100.75—306.60 | 644.54 | |

| O | 281.62±67.63 | 230.50—358.30 | 297.17±81.43 | 224.35—385.10 | 133.75±36.98 | 108.90—176.25 | 712.54 | |

| Nov, 2022 | U | 327.80±183.92 | 197.75—457.85 | 557.43±0.00 | 554.05—560.80 | 1313.60±0.00 | 1285.15—1342.05 | 2198.83 |

| M | 41.48±38.36 | 14.35—68.60 | 183.30±167.02 | 65.20—301.40 | 301.08±383.29 | 30.05—572.10 | 525.86 | |

| D | 34.35±0.99 | 33.65—35.05 | 5.00±0.49 | 4.65—5.35 | 27.68±3.22 | 25.40—29.95 | 67.03 | |

| O | 6.98±4.56 | 3.75—10.20 | 37.13±12.48 | 28.30—45.95 | 19.48±2.02 | 18.05—20.90 | 63.59 | |

| Feb, 2023 | U | 223.66±185.24 | 43.00—399.15 | 183.49±191.92 | 5.60—359.70 | 213.04±213.39 | 2.25—412.20 | 620.19 |

| M | 43.76±1.29 | 41.75—45.75 | 46.04±9.44 | 31.95—54.90 | 20.57±17.34 | 2.45—39.10 | 110.37 | |

| D | 26.73±20.12 | NQ—52.80 | 165.11±61.73 | 115.35—255.00 | 86.87±15.61 | 72.20—112.95 | 278.71 | |

| O | 16.12±11.70 | 3.60—28.80 | 228.98±24.01 | 204.50—251.00 | 118.01±4.33 | 112.30—123.50 | 363.11 |

| Date | Site | Max. NAP (ng/L) |

HQ (ng/L) |

Ecological Risk Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar, 2022 | U | 6.20 | 9.12E-05 | Insignificant |

| M | 50.25 | 7.39E-04 | Insignificant | |

| D | 49.15 | 7.23E-04 | Insignificant | |

| O | 58.05 | 8.54E-04 | Insignificant | |

| Sep, 2022 | U | 649.10 | 9.55E-03 | Insignificant |

| M | 372.55 | 5.48E-03 | Insignificant | |

| D | 261.80 | 3.85E-03 | Insignificant | |

| O | 358.30 | 5.27E-03 | Insignificant | |

| Nov, 2022 | U | 457.85 | 6.73E-03 | Insignificant |

| M | 68.60 | 1.01E-03 | Insignificant | |

| D | 35.05 | 5.15E-04 | Insignificant | |

| O | 10.20 | 1.50E-04 | Insignificant | |

| Feb, 2023 | U | 399.15 | 5.87E-03 | Insignificant |

| M | 45.75 | 6.73E-04 | Insignificant | |

| D | 52.80 | 7.76E-04 | Insignificant | |

| O | 28.80 | 4.24E-04 | Insignificant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).