Submitted:

28 April 2024

Posted:

29 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

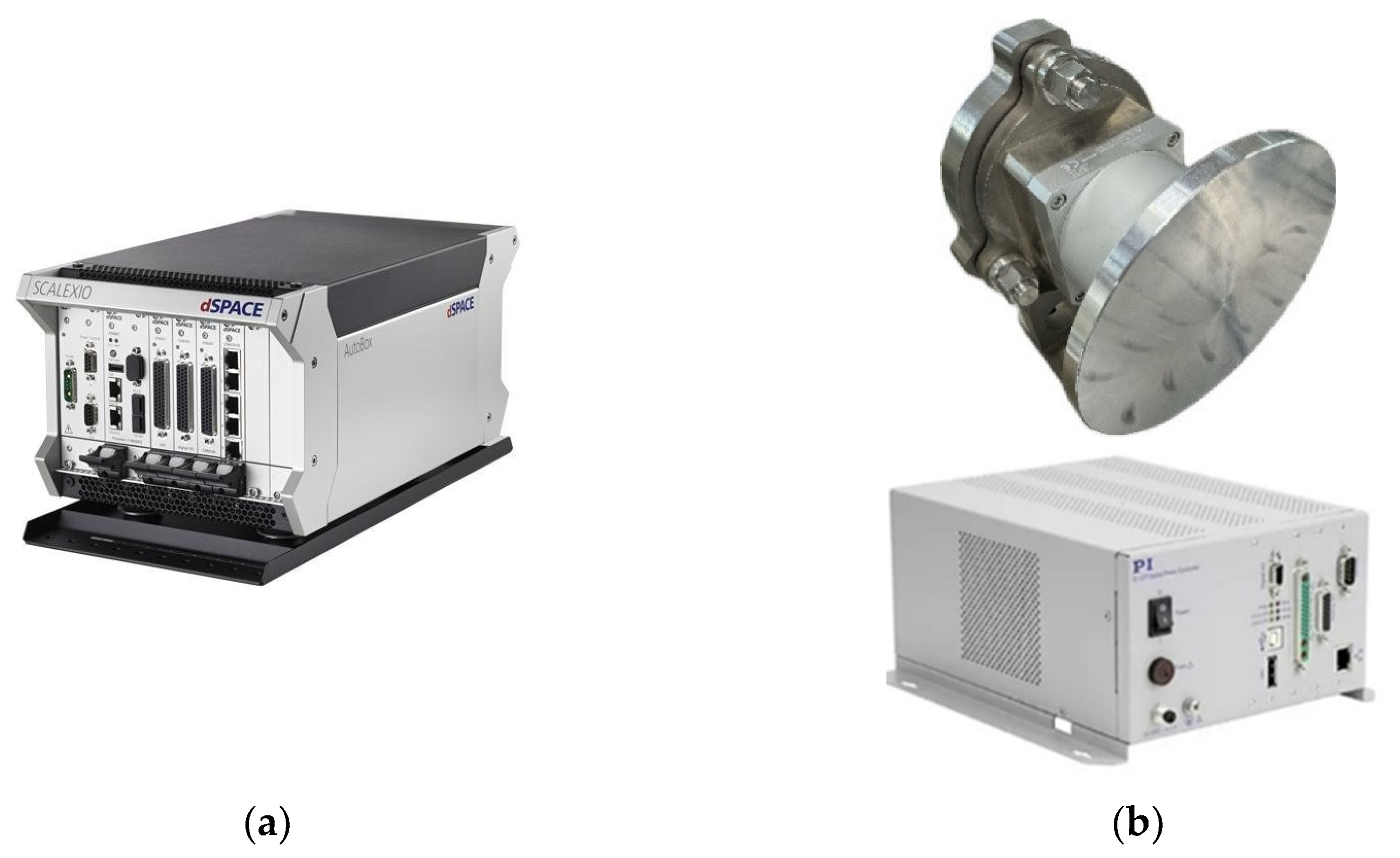

2. FSM Control System

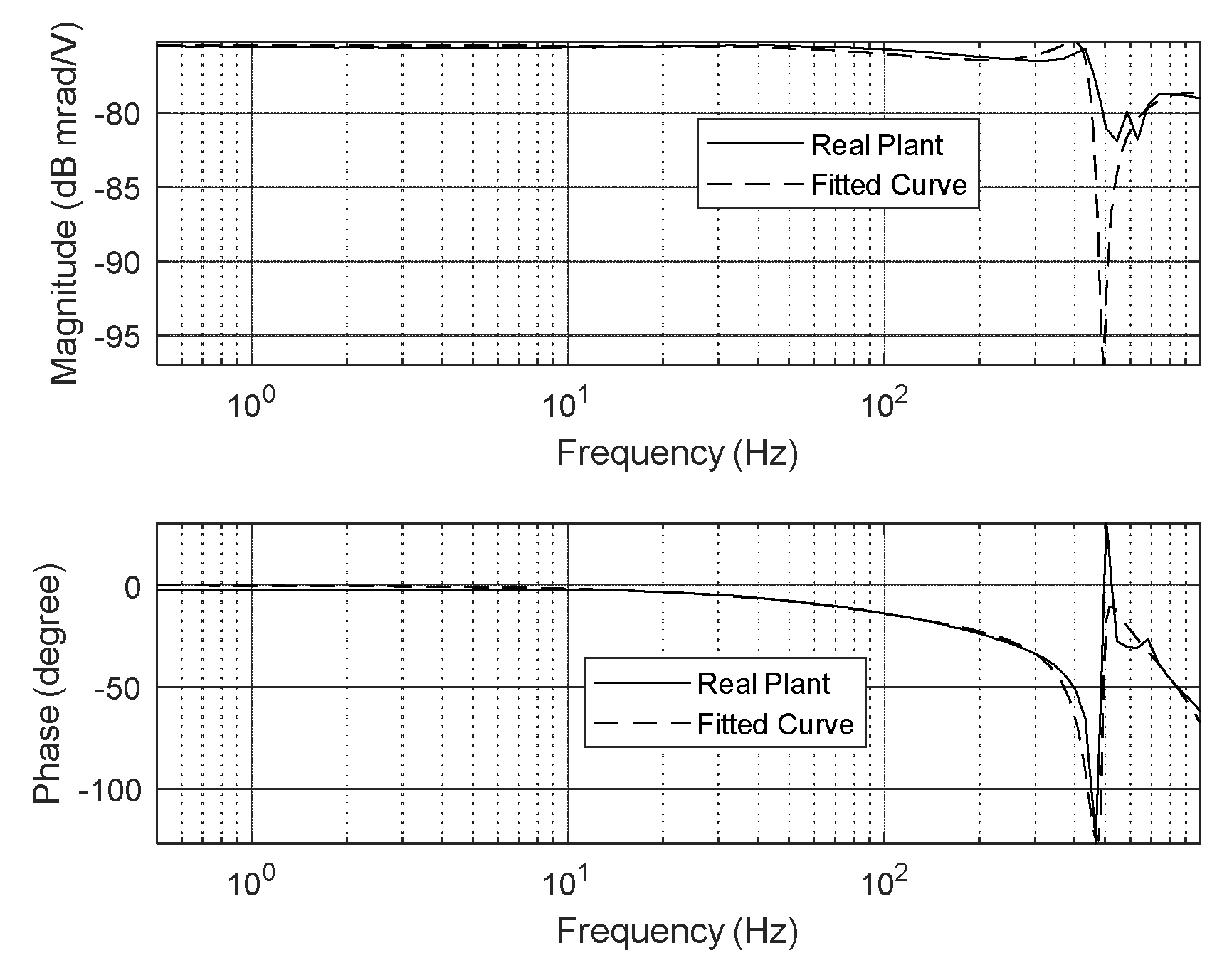

2.1. Dynamic Characteristics of PZT Actuator

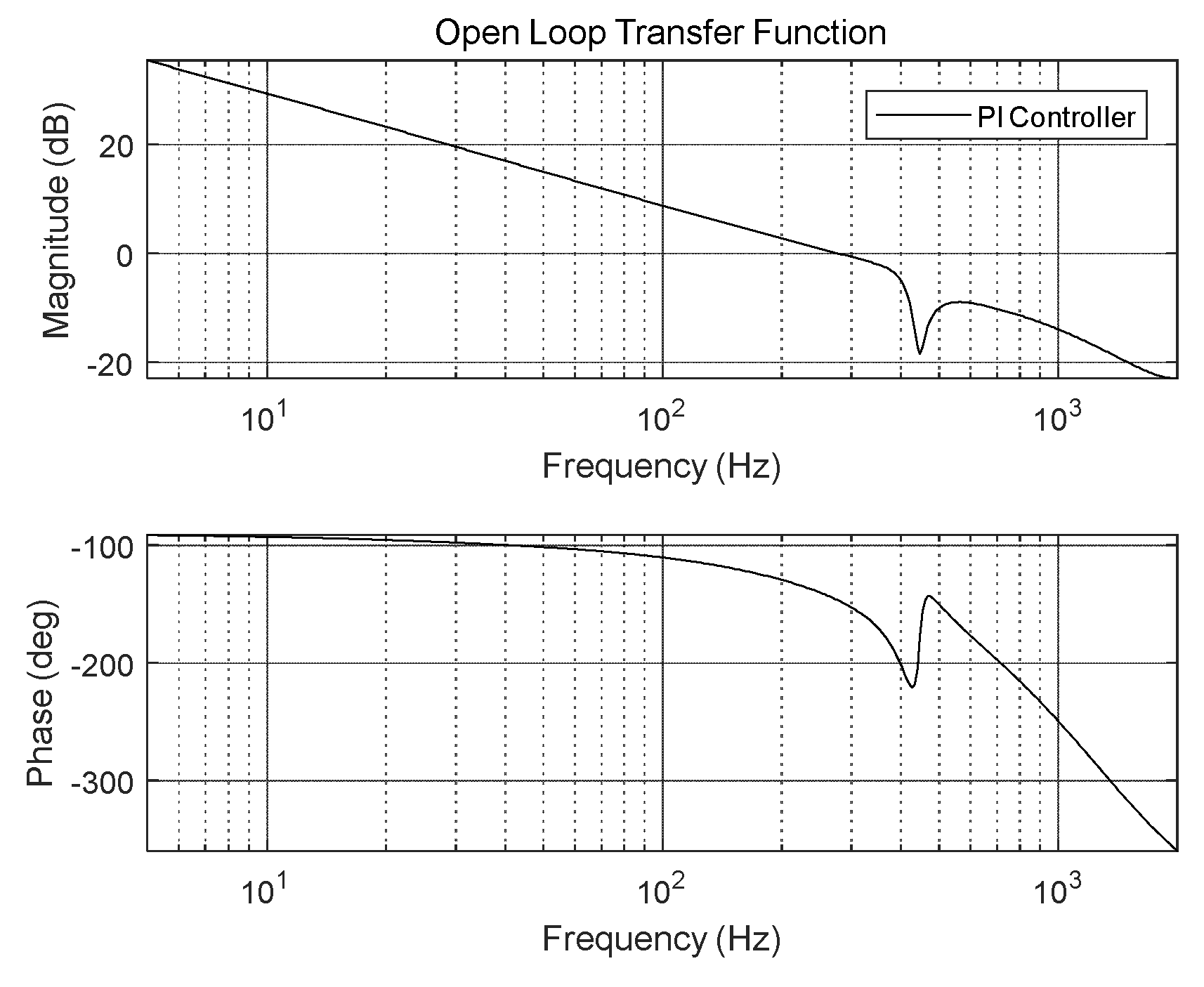

2.1. Tip-Tilt Controller of FSM Control System

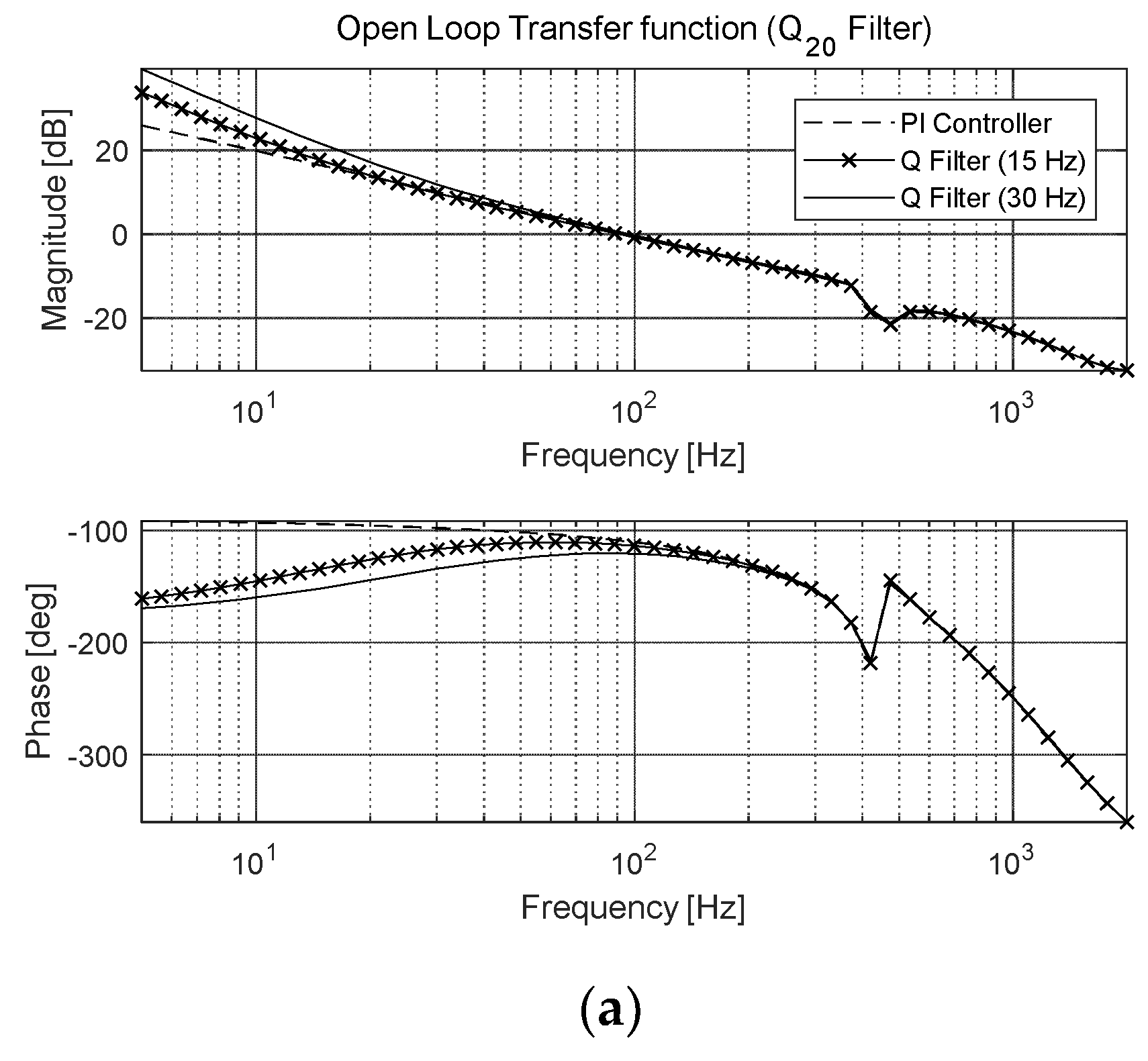

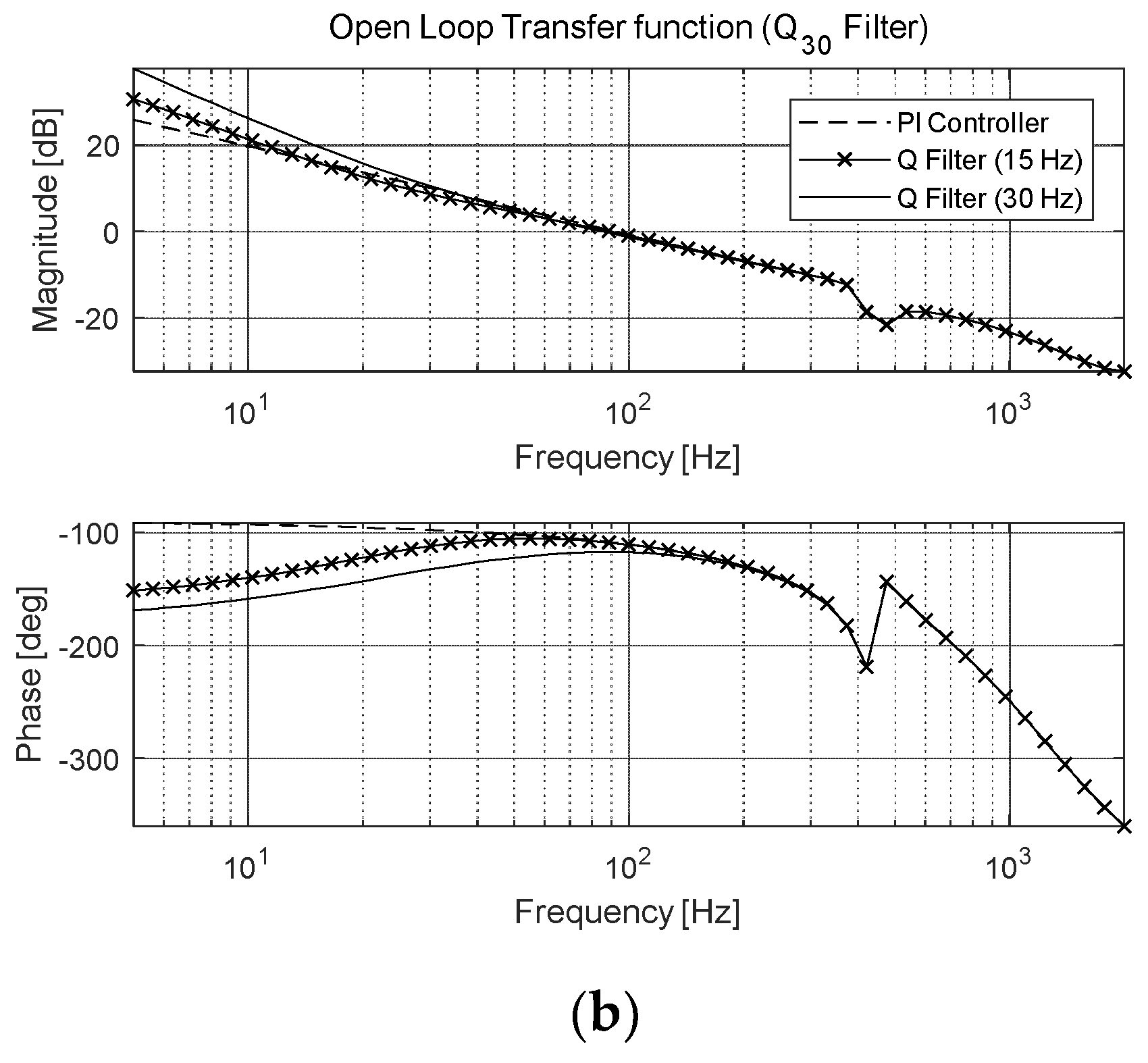

3. Anti-Shock Controller for FSM System

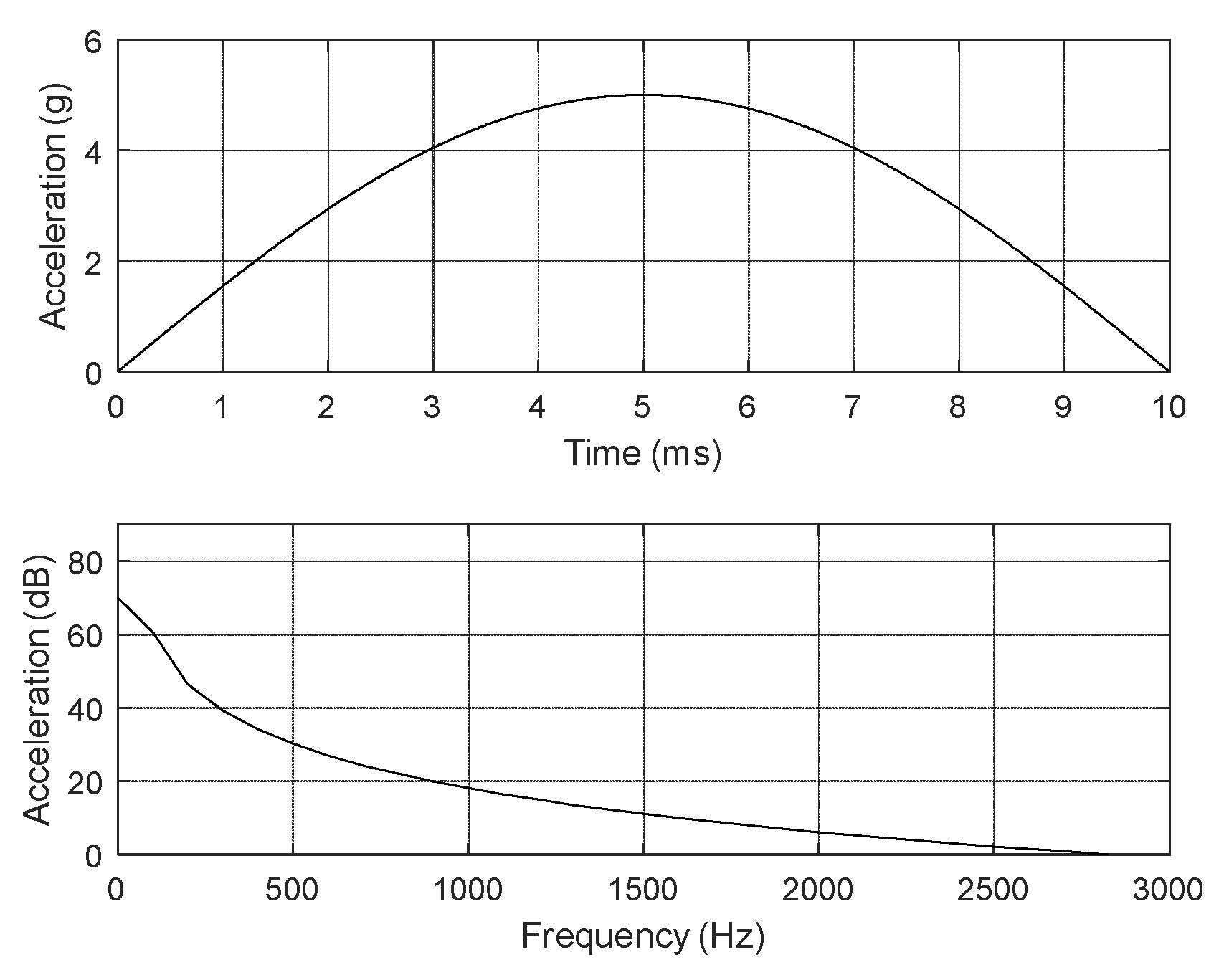

3.1. Shock Specifications

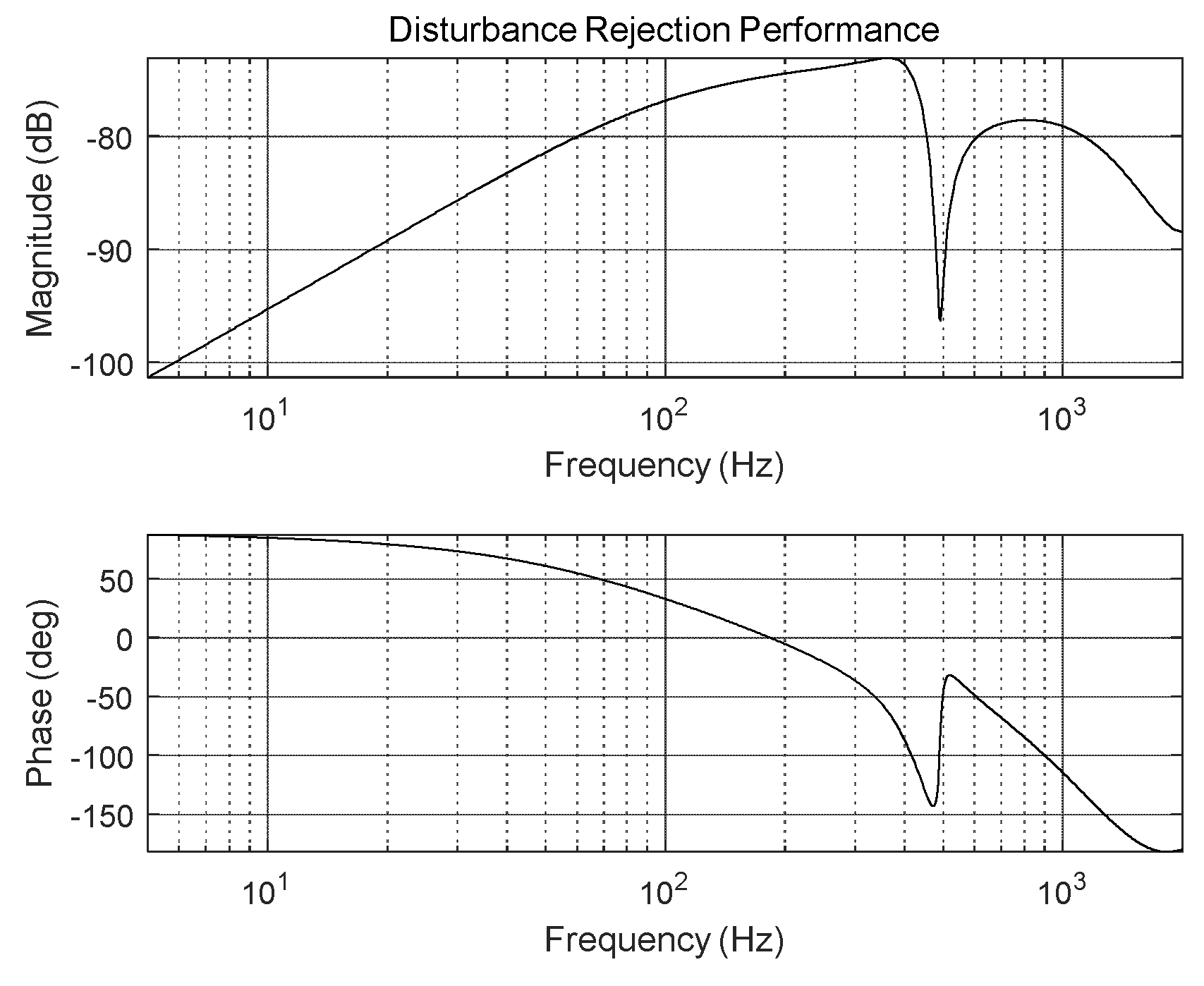

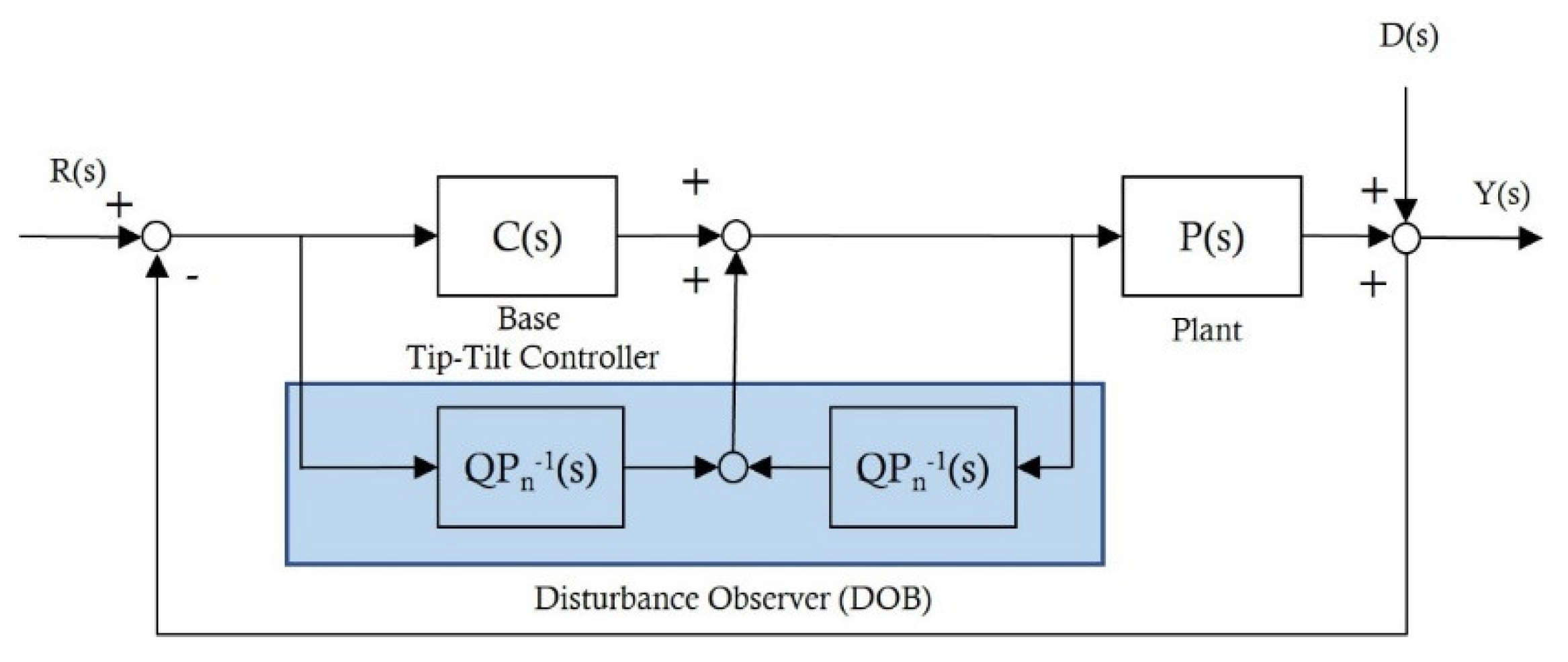

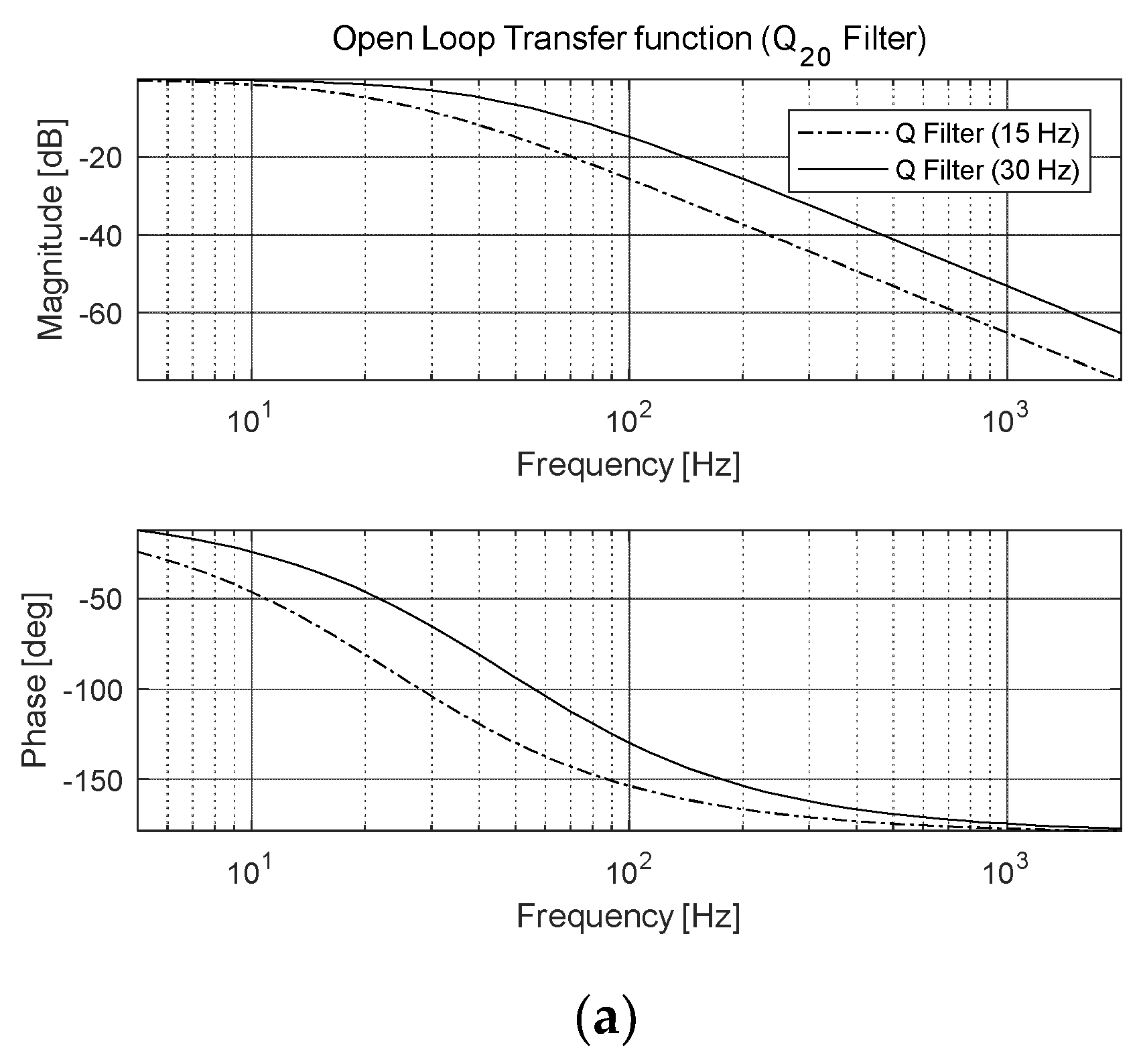

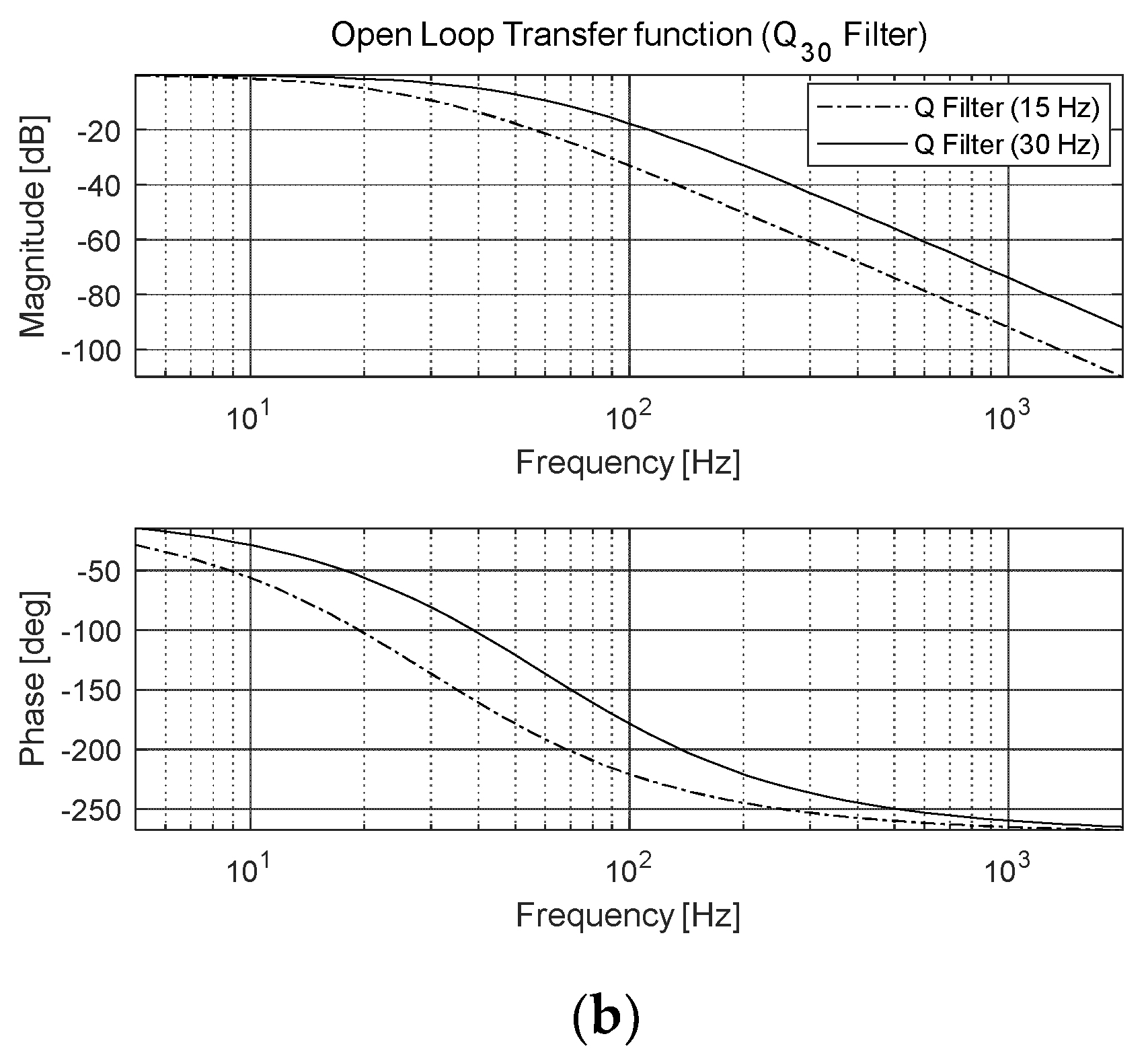

3.1. DOB-Based Anti-Shock Controller

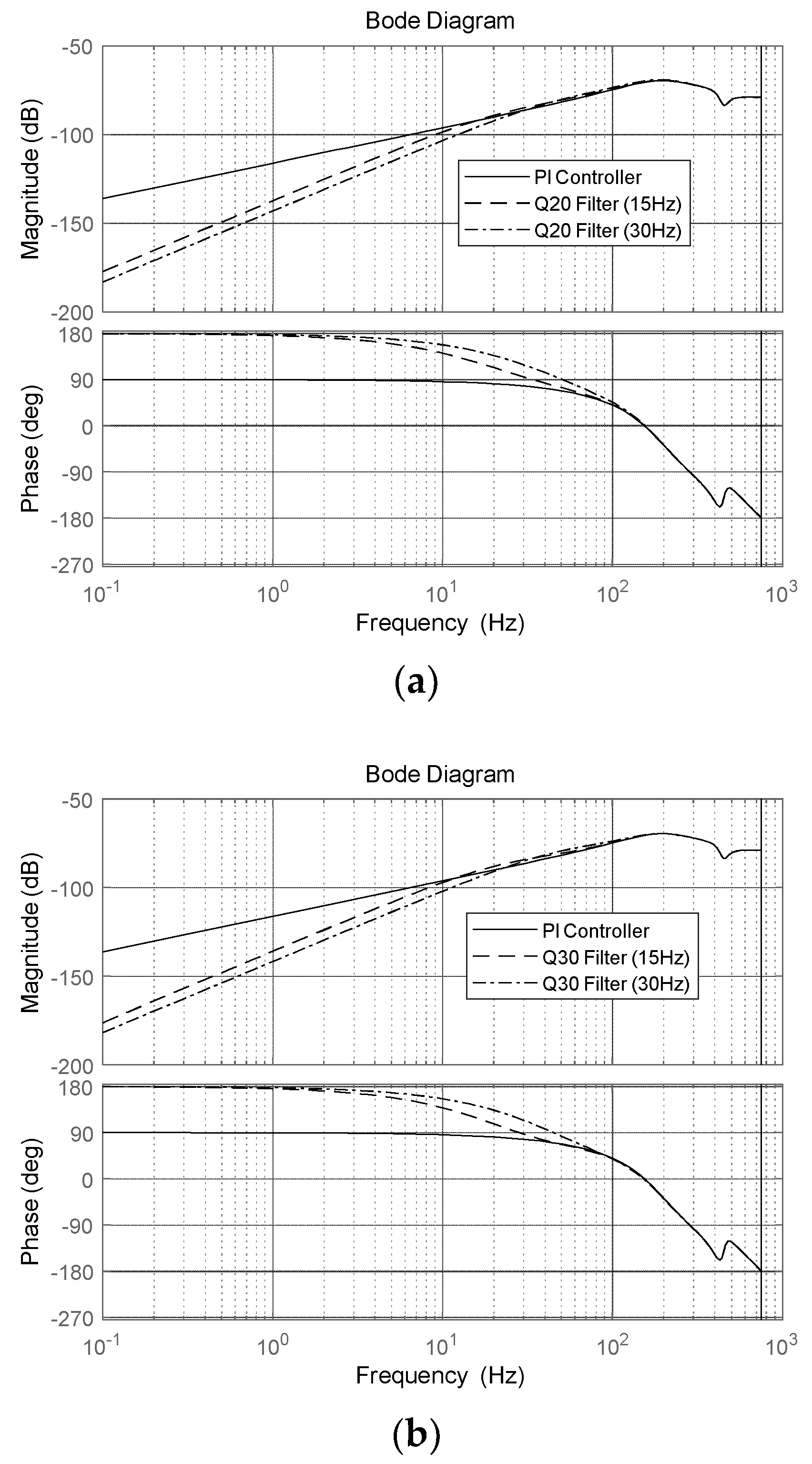

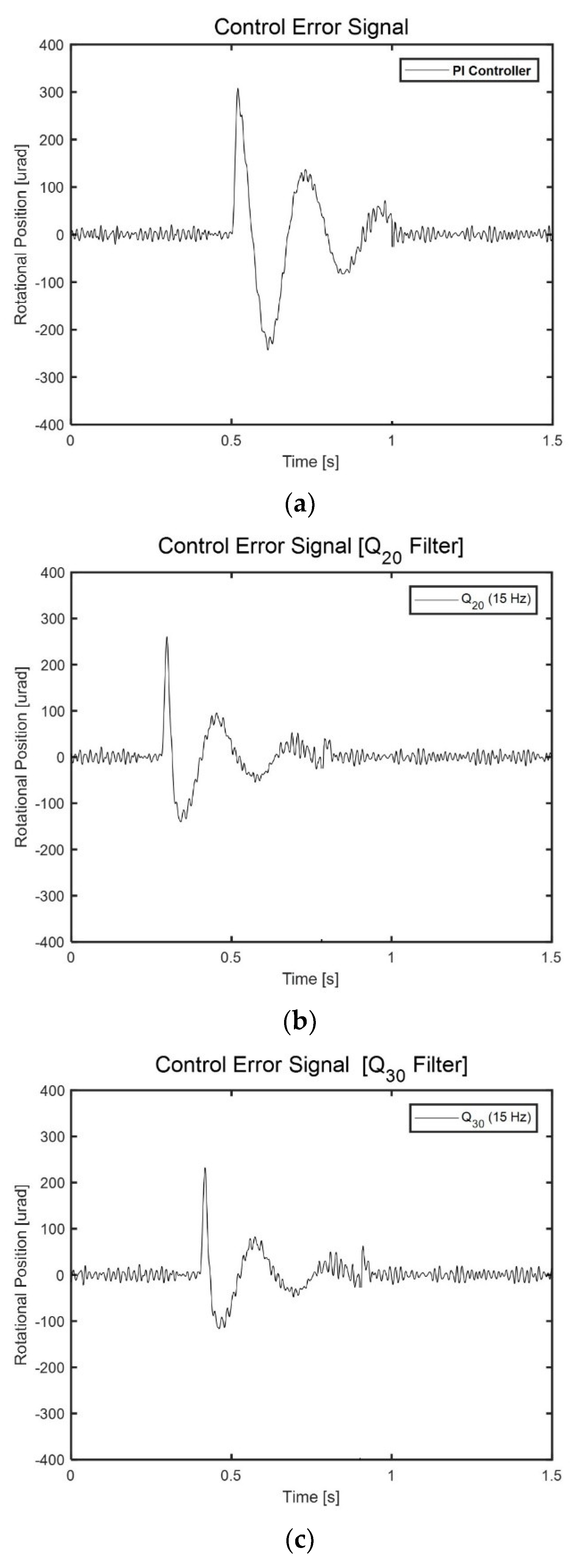

4. Experimental Results of Anti-Shock Controller for FSM System

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun C, Ding Y, Wang D, et al. “Backscanning step and stare imaging system with high frame rate and wide coverage,” App. Opt. 2015, 54, 4960–4965. [CrossRef]

- Chen N, Potsaid B, Wen J T, et al. “Modeling and control of a fast steering mirror in imaging applications,” In: Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Auto. Sei. Eng. Toronto: IEEE, 2010, 27–32.

- Park J H, Lee H S, Lee J H, et al. “Design of a piezoelectric-driven tilt mirror for a fast laser scanner,” JAP 2012, 51(9S2), 09MD14.

- Liu W, Yao K, Huang D, et al. “Performance evaluation of coherent free space optical communications with a double-stage fast-steering-mirror adaptive optics system depending on the Greenwood frequency,” Opt. Exp. 2016, 24, 13288–13302. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Q, Ben-Tzvi P, Fan D, “Design and analysis of a fast steering mirror for precision laser beams steering,” Sensors Transducers J. 2009, 5, 104–118.

- Mokbel H F, Yuan W, Ying L Q, et al. “Research on the mechanical design of two-axis fast steering mirror for optical beam guidance,” In: Proc. 2012 Int. Conf. Mech. Eng. Mat. Sci. 2012, 205–209.

- Wang C, Hu L, Xu H, et al. “Wavefront detection method of a single-sensor based adaptive optics system,” Opt. Exp. 2015, 23, 21403–21414.

- Pan J W, Chu J, Zhuang S, et al. “A new method for incoherent combining of far-field laser beams based on multiple faculae recognition,” In: Proc. SPIE 10710, Young Scientists Forum. 2017, 1071034.

- Loney G L, “Design of a small-aperture steering mirror for high-bandwidth acquisition and tracking,” Opt. Eng. 1990, 29, 1360–1365.

- Merritt P H, Albertine J R, “Beam control for high-energy laser devices,” Opt. Eng. 2013, 52, 021005. [CrossRef]

- Wood G L, Perram G P, Marciniak M A, et al. “High-energy laser weapons: Technology overview,” In: Proc. SPIE 5414, Laser Technol. Def. Security 2004, 1–25.

- Meline M E, Harrell J P, Lohnes K A, “Universal beam steering mirror design using the cross blade flexure,” In: Proc. SPIE 1697, 1992, 424–443.

- Dong W, Tang J, ElDeeb Y, “Design of dual-stage actuation system for high precision optical manufacturing,” In: Proc. SPIE 6928, 2008, 692828.

- Schellekens P, Rosielle N, Vermeulen H, et al., “Design for precision: Current status and trends,” CIRP Ann. 1998, 47, 557–586. [CrossRef]

- Ghai D P, Venkatesh A, Swami H R, et al., “Large aperture, tip tilt mirror for beam jitter correction in high power lasers”, Defense Sci. J. 2013, 63, 606–610.

- Kluk D J, Boulet MT, Trumper D L. “A high-bandwidth, high-precision, two-axis steering mirror with moving iron actuator,” Mechatronics 2012, 22, 257–270. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Wu T, Ji Y, et al., “Model analysis and resonance suppression of wide-bandwidth inertial reference system,” Nanotechnol. Precis. Eng. 2 2019, 177–187. [CrossRef]

- Gu G Y, Zhu L M, Su CY, et al., “Modeling and control of piezo-actuated nanopositioning stages: A survey,” IEEE Trans. Auto. Sci. Eng. 2016, 13, 313–332.

- Ling J, Feng Z, Ming M, et al., “Damping controller design for nanopositioners: A hybrid reference model matching and virtual reference feedback tuning approach,” Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2018, 19, 13–22. [CrossRef]

- Wadikhaye S P, Yong Y K, Bhikkaji B, et al., “Control of a piezoelectrically actuated high-speed serial-kinematic AFM nanopositioner,” Smart Mater. Struct. 2014, 23, 025030. [CrossRef]

- Gu G Y, Zhu L M, Su C Y, “Integral resonant damping for high-bandwidth control of piezoceramic stack actuators with asymmetric hysteresis nonlinearity,” Mechatronics 2014, 24, 367–375.

- McEver M A, Cole D G, Clark R L, “Adaptive feedback control of optical jitter using Q-parameterization,” Opt. Eng. 2004, 43, 904–910. [CrossRef]

- Nestor O, Arancibia O, Chen N, et al., “Adaptive control of a MEMS steering mirror for free-space laser communications,” In: Proc. SPIE. 2005, 5892, 589210.

- Wang G, Chen G, Bai F, “High-speed and precision control of a piezoelectric positioner with hysteresis, resonance and disturbance compensation,” Microsyst. Technol. 2016, 22, 2499–2509.

- Schitter G, Thurner P J, Hansma P K, “Design and input-shaping control of a novel scanner for high-speed atomic force microscopy,” Mechatronics 2008, 18, 282–288. [CrossRef]

- Odgaard P F, Stoustrup J, Andersen P, et al., “A simulation model of focus and radial servos in compact disc players with disc surface defects,” In: Proc. 2004 IEEE Int. Conf. Control Applicat. 2004, 105–110.

- Vidal E, Hansen K G, Andersen R S, et al., “Linear quadratic controller with fault detection in compact disk players,” In: Proc. 2001 IEEE Int. Conf. Control Applicat. 2001, 77–81.

- Germann L M, Gupta A A, Lewis R A, “Precision pointing and inertial line-of-sight stabilization using fine-steering mirrors, star trackers, and accelerometers,” In: Proc. SPIE 1988, 887, 96.

- Hilkert, J M, “A comparison of inertial line-of-sight stabilization techniques using mirrors,” In: Proc. SPIE 2004, 5430, 13.

- Zhou Y, Steinbuch M, “Estimator-based sliding mode control of an optical disc drive under shock and vibration,” In: Proc. 2002 IEEE Int. Conf. Control Applicat. 2002, 631–636.

- Gu G Y, Zhu L M, “Motion control of piezoceramic actuators with creep, hysteresis and vibration compensation,” Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 2013, 197, 76–87.

- Böhm M, Pott J U, Kürster M, et al., “Delay compensation for real time disturbance estimation at extremely large telescopes,” IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2016, 25, 1384–1393. [CrossRef]

- Glück M, Pott J U, Sawodny O, “Piezo-actuated vibration disturbance mirror for investigating accelerometer-based tip-tilt reconstruction in large telescopes,” IFAC Papersonline 2016, 49, 361–366.

- Nakao M, Ohnishi K, Miyachi K A, “Robust decentralized joint control based on interference estimation,” In: Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Robotics Automat. 1987, 326–331.

- Ohnishi K, “Microprocessor-controlled DC motor for load-insensitive position servo system,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1985, 34, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Ohishi K, Ohde H, “Collision and force control for robot manipulator without force sensor,” In: Proc. 20th Ann. Conf. IEEE Indust. Electron., Bologna, Italy, 5–9 September 1994, 2, 766–771.

- Umeno T, Hori Y, “Robust speed control of DC servomotors using modern two degrees-of-freedom controller design,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2002, 38, 363–368. [CrossRef]

- Kim B K, Chung W K, Youm Y, “Robust learning control for robot manipulators based on disturbance observer,” In: Proc. 22nd Int. Conf. Indust. Electron., Control, Instrumentation 1996, 1276–1282.

- Ishikawa J, Tomizuka M, “Pivot friction compensation using an accelerometer and a disturbance observer for hard disk,” IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 1998, 3, 194–201. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y H, Massner W, “A novel disturbance observer design for magnetic hard drive servo system with rotary actuator,” IEEE Trans. Magn. 1998, 34, 1892–1894.

- Wang L, Su J, Xiang G, “Robust motion control system design with scheduled disturbance observer,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 6519–6529. [CrossRef]

- Chen W H, Yang J, Guo L, et al., “Disturbance-observer-based control and related methods—An overview,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 1083–1095.

- Tang T, Ma J, Ge R, “PID-I controller of charge coupled device-based tracking loop for fast-steering mirror,” Opt. Eng. 2011, 50, 043002. [CrossRef]

- Lee H S, Tomizuka M, “Robust motion controller design for high-accuracy positioning systems,” IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2000, 2, 32–38.

- White M, Tomizuka M, Smith C, “Improved track following in magnetic disk drives using a disturbance observer,” IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2000, 5, 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Nam B U, Gimm H I, Kang D W, et al. “Design and analysis of a tip-tilt guide mechanism for the fast steering of a large-scale mirror,” Opt. Eng. 2016, 55, 106120.

- Nam B U, Gimm H I, Kim J G, et al. “Development of a fast steering mirror of large diameter,” In: Proc. SPIE. 2017, 10249, 102490R.

| Specification | Value |

|---|---|

| Resonance frequency | 450.2 Hz |

| 5 Hz sensitivity | 168.3 µrad/V |

| Gain of voltage amplifier | 10 V/V |

| Gain of sensor amplifier | 0.0059 V/µrad |

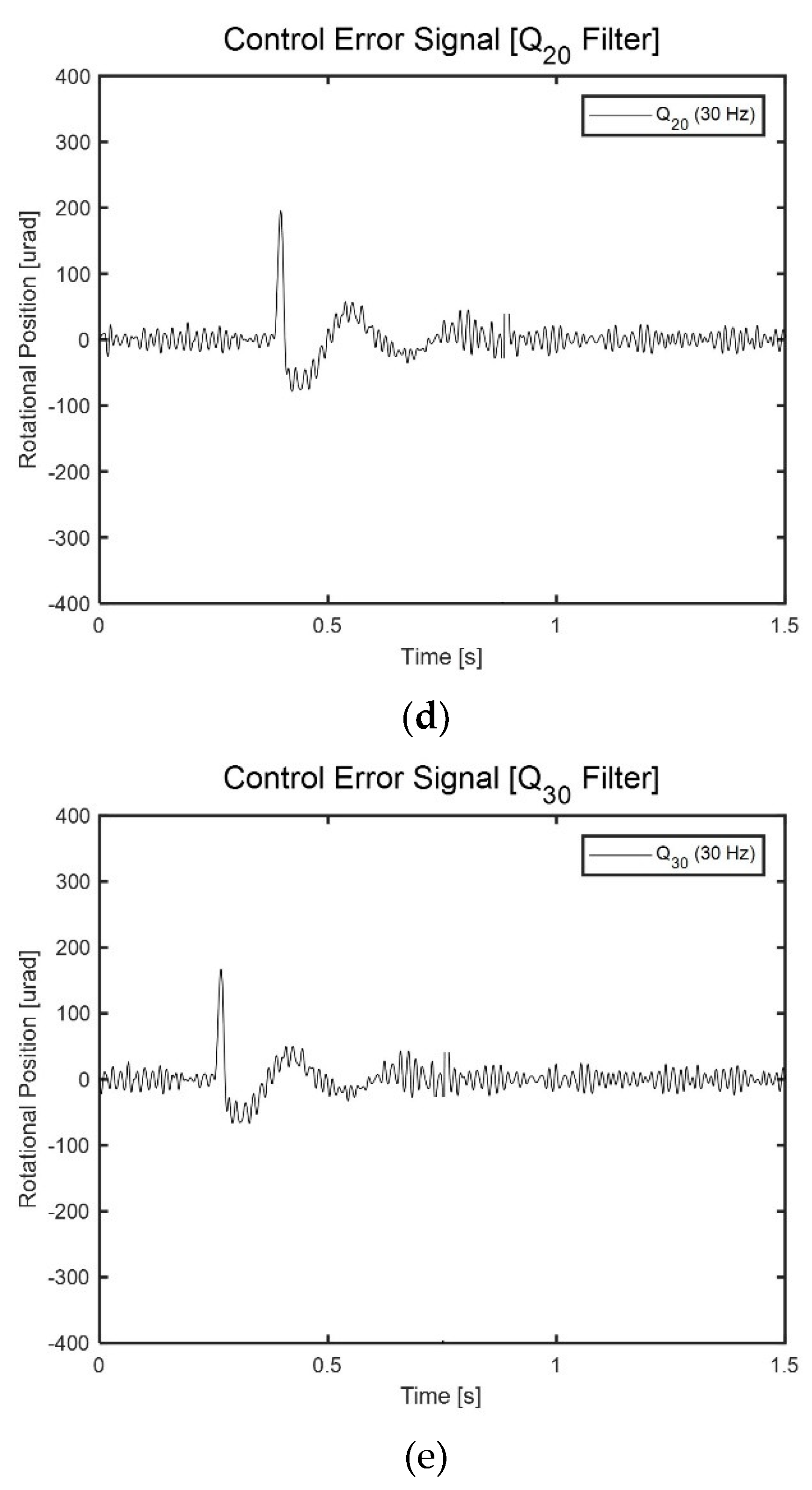

| Specification | PI controller |

Q20 filter | Q30 filter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 Hz | 30 Hz | 15 Hz | 30 Hz | ||

| Minimum rotational position error (rms) | 308.1 μrad | 260.5 μrad | 195.9 μrad | 232.3 μrad | 167.2 μrad |

| Reduced rate | - | 15.5 % | 36.4 % | 24.6 % | 45.7 % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).