Submitted:

24 April 2024

Posted:

28 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Some algorithms stack and combine polarimetric decomposition features without considering the inherent limitations of the decomposition methods.

- Some methods normalize polarimetric features without accounting for the distribution characteristics of the data, often applying linear normalization methods to non-linear PolSAR data.

- Some methods employ different forms of CNN but overlook the complete scattering information and various polarimetric scattering characteristics in PolSAR images, utilizing incomplete polarized data as input for the network.

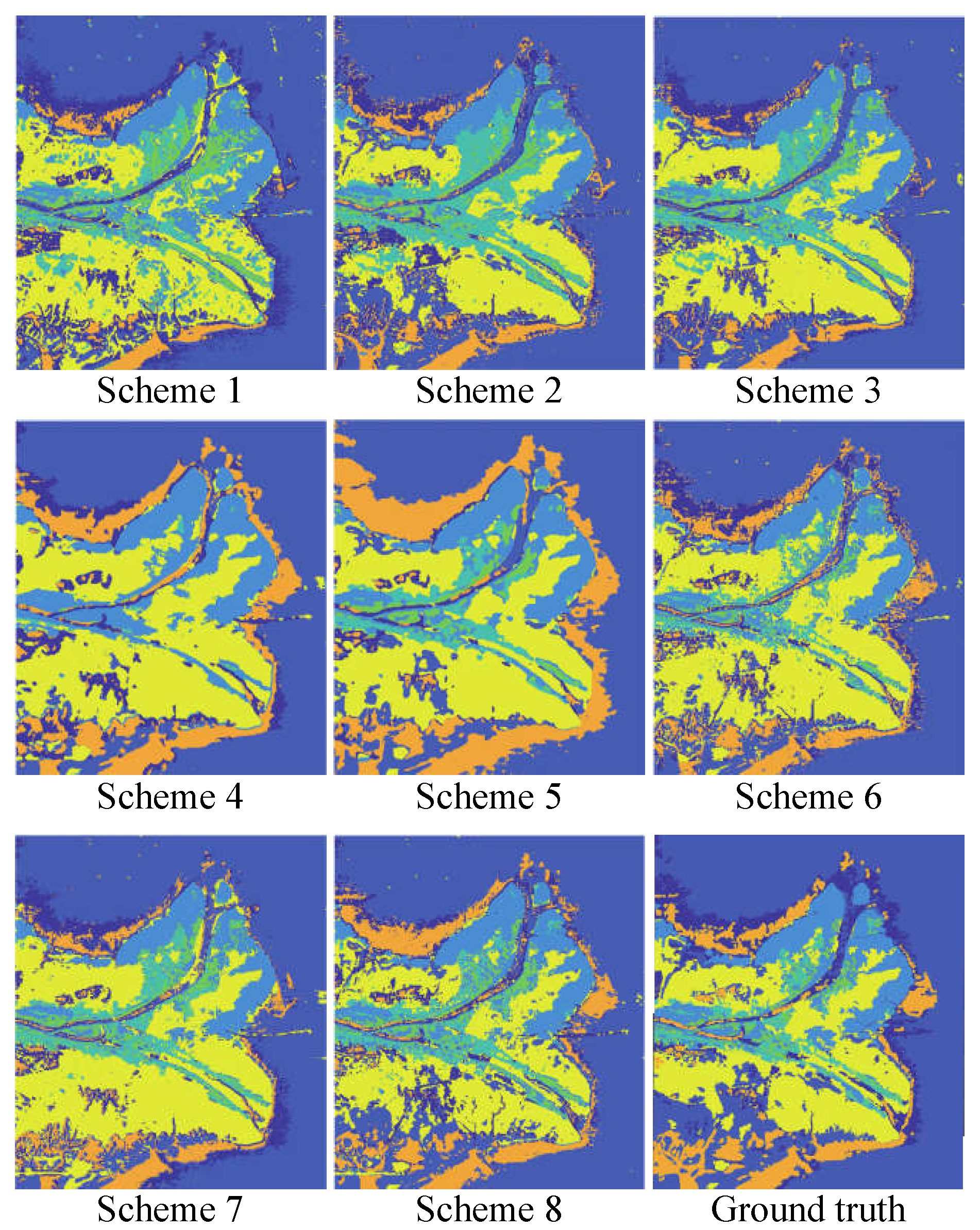

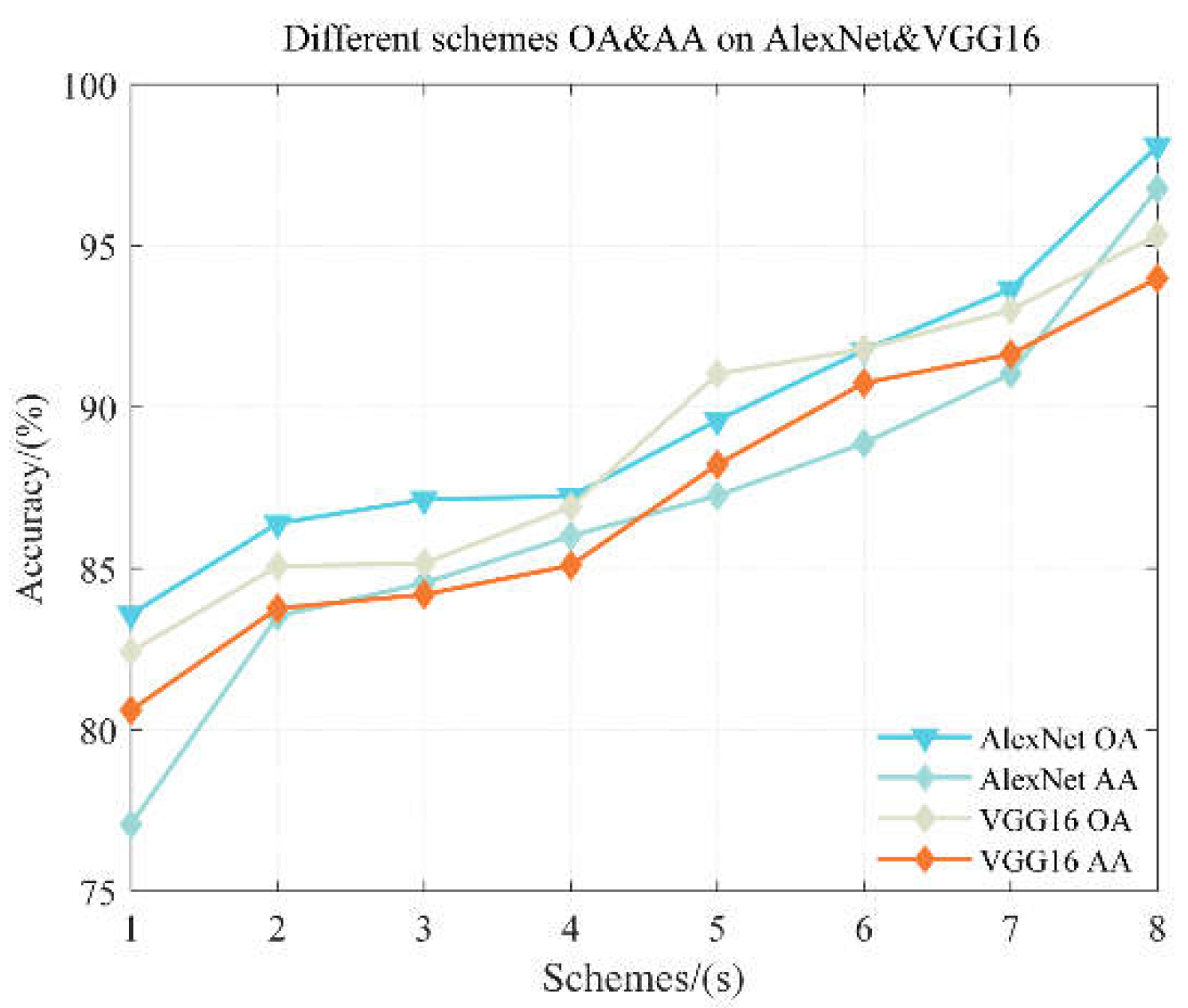

- The classification performance utilizing total power values of the second component (P2) and the third component (P3) obtained from RSD surpasses schemes using surface scattering power value (PS) and double-bounce scattering power value (PD) from RSD. However, the optimal input scheme includes all P2, P3, PS, and PD.

- Regarding input schemes, in the face of limited computational resources, it is advisable to directly use the input scheme with all elements of the T matrix or utilize all components obtained through RSD, as both ensure the completeness of polarimetric information.

- The 21-channel input scheme should be used when computational resources are sufficient.

- The two classic CNNs employed, VGG16 and AlexNet, differ in depth. After five rounds of accuracy statistics, VGG16 demonstrates superior stability. While the 5-layer AlexNet neural network achieves high accuracy, it suggests that for PolSAR image classification using CNNs, an excessively deep network is unnecessary. In other words, VGG16 exhibits better stability, while the 5-layer AlexNet achieves higher accuracy.

2. Related Works

2.1. PolSAR Classification with CNN

2.2. Perform Polarization Decomposition Using a Scattering Mechanism

3. Methods

3.1. Data Analysis and Feature Extraction

3.2. Experimental Images and Preprocessing

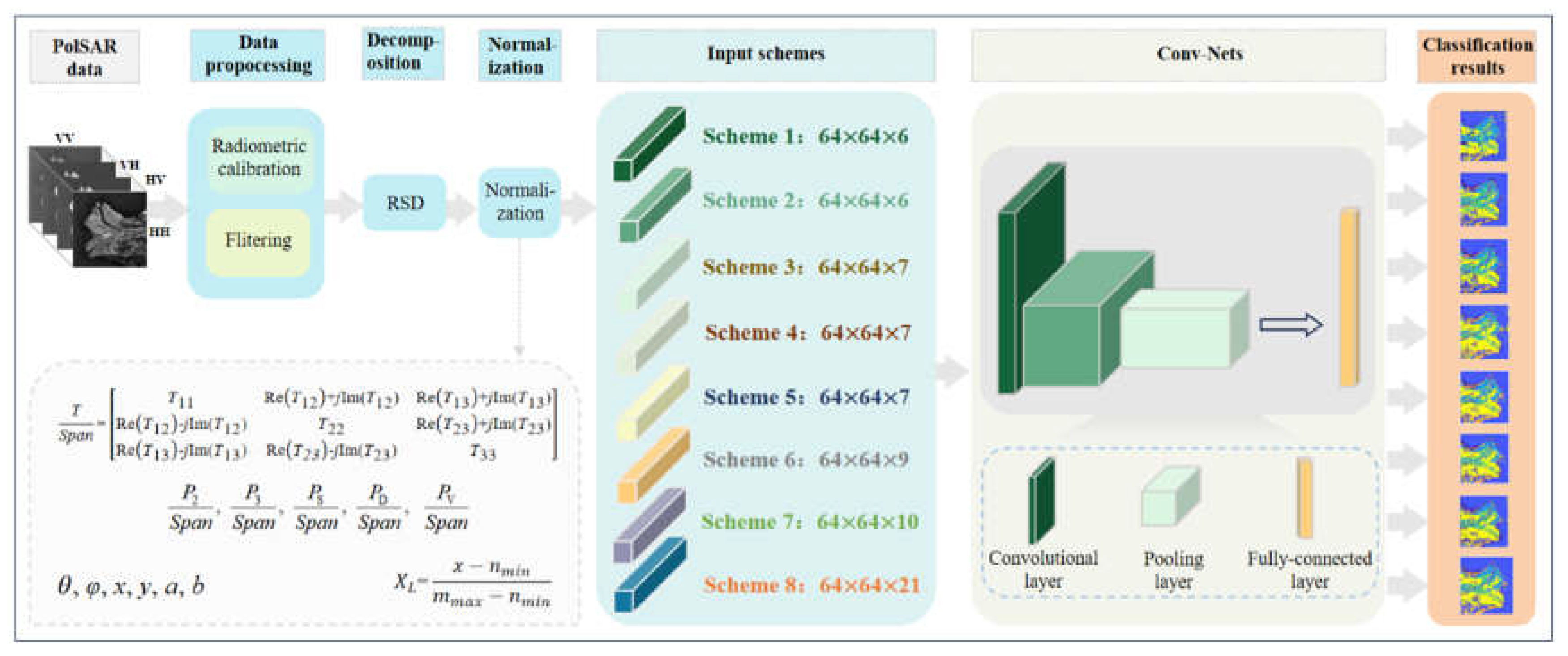

3.3. PolSAR Classification Using Different Polarimetric Data Input Schemes

3.4. Network Selection and Parameter Configuration, Loss Function, Evaluation Criteria

3.5. Experimental Process

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

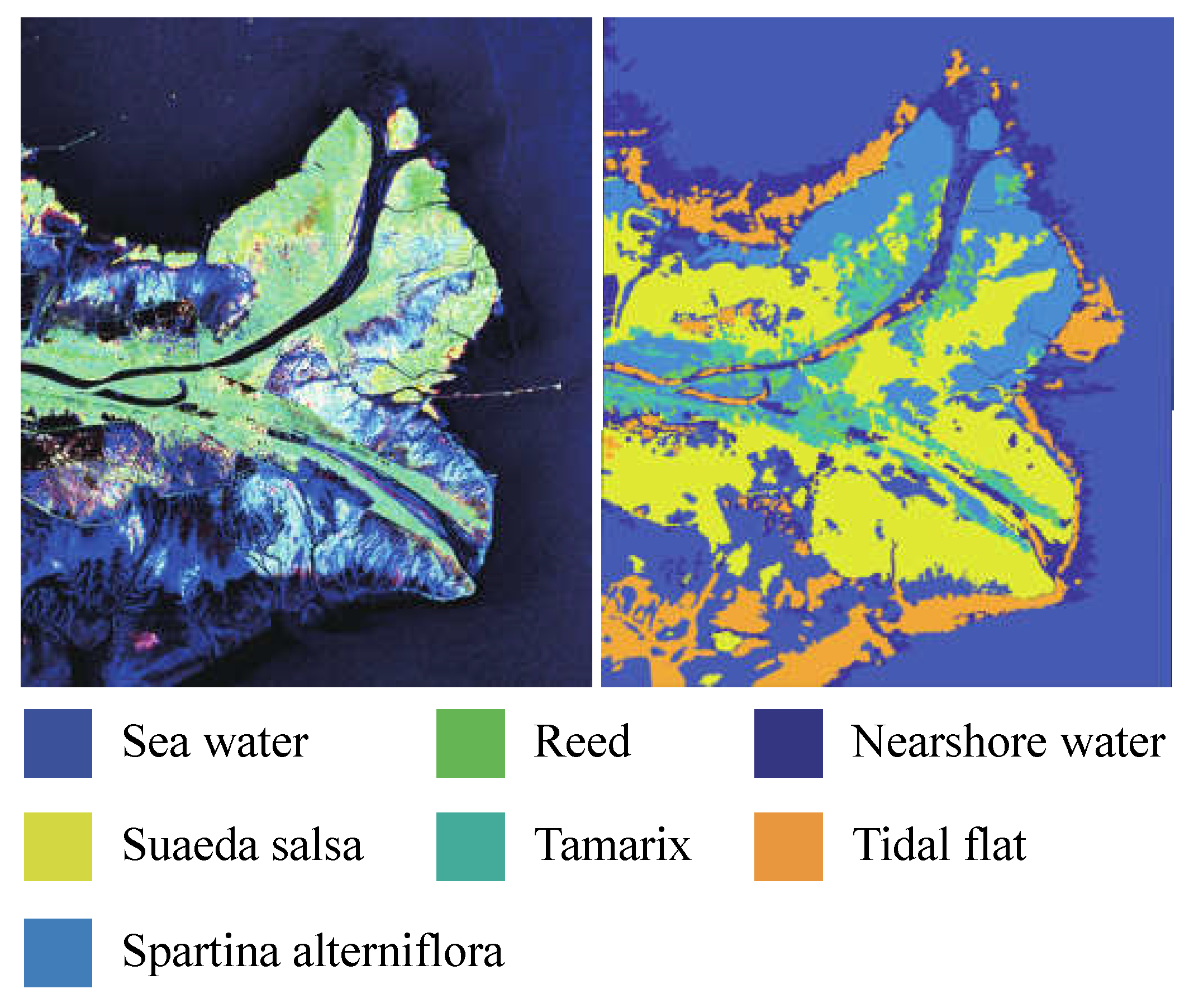

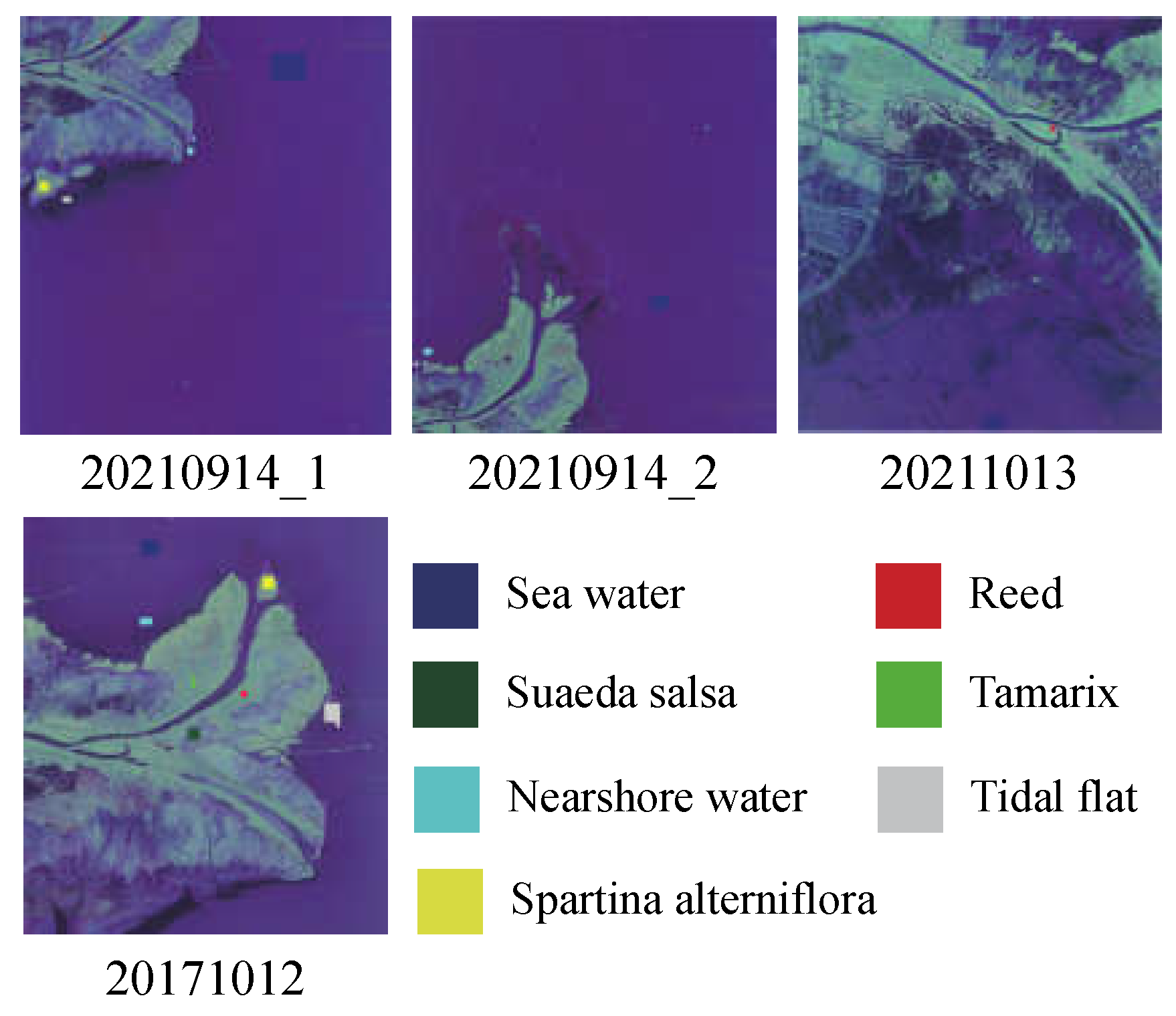

4.1. Data Explanation

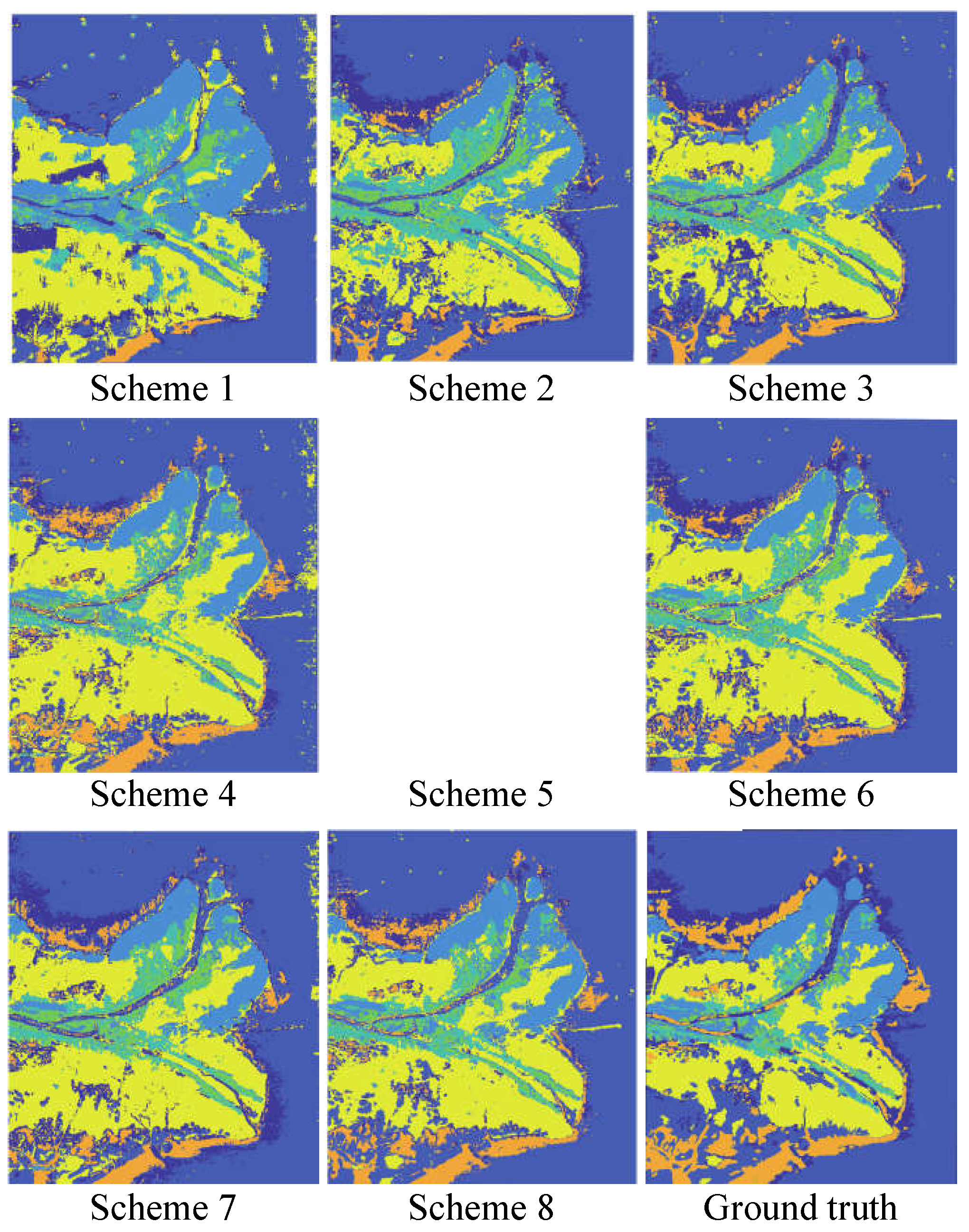

4.2. Classification Results of the Yellow River Delta on AlexNet

4.3. Classification Results on VGG16

5. Conclusions

- The classification performance utilizing total power values of the second component (P2) and the third component (P3), obtained through reflection symmetry decomposition, surpasses the research scheme using surface scattering power (PS) and second-order scattering power (PD) from RSD.

- Concerning polarization data input schemes with limited computational resources, direct use of scheme 7, which encompasses all information of the T matrix, is suggested. If device configuration allows, prioritizing the use of the 21-parameter polarization data input scheme 8, including all parameters of the T matrix and RSD, is recommended.

- Among the two classic CNN models in the experiment, VGG16 exhibits better stability, while the 5-layer AlexNet achieves higher overall classification accuracy. Therefore, for PolSAR image classification using CNN, an excessively deep network may not be necessary. However, deeper networks tend to offer better stability in training accuracy.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Y. Yajima, Y. Yamaguchi, R. Sato, H. Yamada and W. -M. Boerner, “POLSAR Image Analysis of Wetlands Using a Modified Four-Component Scattering Power Decomposition,” in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 46, no. 6, pp. 1667-1673, 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. Shi, T. He, S. Ji, M. Nie and H. Jin, “CNN-improved Superpixel-to-pixel Fuzzy Graph Convolution Network for PolSAR Image Classification,” in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing. [CrossRef]

- M. Gu, Y. Wang, H. Liu and P. Wang, “PolSAR Ship Detection Based on Noncircularity and Oblique Subspace Projection,” in IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 20, pp. 1-5, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Freeman and S. L. Durden, “A three-component scattering model for polarimetric SAR data,” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 963–973, 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Cloude and E. Pottier, ‘‘An entropy based classifification scheme for land applications of polarimetric SAR,’’ IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 68–78, 1997. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Huynen, “Physical reality of radar targets,” Proc. SPIE, vol. 1748, pp. 86–96, 1993.

- J.-S. Lee, M. R. Grunes, and R. Kwok, “Classifification of multi-look polarimetric SAR data based on complex Wishart distribution,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 2299–2311, 1994.

- F. Zhang, P. Li, Y. Zhang, X. Liu, X. Ma and Z. Yin, “A Enhanced DeepLabv3+ for PolSAR image classification,” 2023 4th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application (ICCEA), Hangzhou, China, 2023, pp. 743-746. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, C. He, B. He and M. Tong, “Learning Scattering Similarity and Texture-Based Attention With Convolutional Neural Networks for PolSAR Image Classification,” in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 61, pp. 1-19, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Nie, K. Huang, J. Yang and P. Li, “A Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Framework for PolSAR Imagery Classification,” in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 60, pp. 1-15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. T. Ulaby and C. Elachi, “Radar polarimetry for geoscience applications,” in Geocarto International, Norwood, MA, USA: Artech House, 1990, pp. 376. [Online]. Available: http://www.informaworld.com .

- M. Yang, L. Zhang, S. C. K. Shiu, and D. Zhang, “Gabor feature based robust representation and classifification for face recognition with Gabor occlusion dictionary,” Pattern Recognit., vol. 46, no. 7. pp. 1865–1878, 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, T. X. Han, and S. Yan, “An HOG-LBP human detector with partial occlusion handing,” in Proc. IEEE 12th Int. Conf. Comput. Vis., 2009, pp. 32–39. [CrossRef]

- S. Lazebnik, C. Schmid, and J. Ponce, “Beyond bags of features: Spatial pyranic matching recognizing natural scene categories,” in Proc. IEEE Comput. Soc. Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., 2006, pp. 2169–2178.

- Q. Chen, L. Li, Q. Xu, S. Yang, X. Shi, and X. Liu, ‘‘Multi-feature segmentation for high-resolution polarimetric SAR data based on fractal net evolution approach,’’ Remote Sens., vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 570, 2011. [CrossRef]

- W. Hua, S. Wang, W. Xie, Y. Guo, and X. Jin, “Dual-channel convolutional neural network for polarimetric SAR images classifification,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Geosci. Remote Sens. Symp., 2019, pp. 3201–3204. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ren, B. Hou, Z. Wen, and L. Jiao, “Patch-sorted deep feature learning for high resolution SAR image classifification,” IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens., vol. 11, no. 9, pp. 3113–3126, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Ai, F. Wang, Y. Mao, Q. Luo, B. Yao, H. Yan, M. Xing, and Y. Wu, “A Fine PolSAR Terrain Classification Algorithm Using the Texture Feature Fusion-Based Improved Convolutional Autoencoder,” in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 60, pp. 1-14, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, H. Wang, F. Xu, and Y.-Q. Jin, “Polarimetric SAR image classifification using deep convolutional neural networks,” IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett., vol. 13, no. 12, pp. 1935–1939, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S.-W. Chen and C.-S. Tao, “PolSAR image classifification using polarimetric-feature-driven deep convolutional neural network,” IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 627–631, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Feng, T. Min, W. Xie, and L. Hanqiang, “A new parallel dual-channel fully convolutional network via semi-supervised fcm for polsar image classification,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, no. 99, pp. 1-1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Shi, H. Jin and X. Li, “A Novel Multi-Feature Joint Learning Method for Fast Polarimetric SAR Terrain Classification,” in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 30491-30503, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. J. van Zyl, M. Arii, and Y. Kim, “Model-based decomposition of polarimetric SAR covariance matrices constrained for nonnegative eigenvalues,” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., vol. 49, no. 9, pp. 3452–3459, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Q. Yin, W. Hong, F. Zhang, and E. Pottier, “Optimal combination of polarimetric features for vegetation classifification in PolSAR image,” IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens., vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 3919–3931, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and G. Hinton, “Imagenet classifification with deep convolutional neural networks,” in Proc. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., 2012, pp. 1097–1105.

- Szegedy et al., “Going deeper with convolutions,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR), 015, pp. 1–9.

- K. Simonyan and A. Zisserman, “Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent., 2015, pp. 1–14.

- S. Gou, X. Li and X. Yang, “Coastal Zone Classification With Fully Polarimetric SAR Imagery,” in IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 13, no. 11, pp. 1616-1620, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Bi, J. Sun and Z. Xu, “A Graph-Based Semisupervised Deep Learning Model for PolSAR Image Classification,” in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 2116-2132, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Gui, X. Xu, R. Yang, Z. Xu, L. Wang and F. Pu, “A General Feature Paradigm for Unsupervised Cross-Domain PolSAR Image Classification,” in IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 19, pp. 1-5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, J. Cheng, Y. Zhou, F. Zhang and Q. Yin, “A Multichannel Fusion Convolutional Neural Network Based on Scattering Mechanism for PolSAR Image Classification,” in IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 19, pp. 1-5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Xiao, Z. Wang, Y. Wu, X. Gao and X. Sun, “Terrain Segmentation in Polarimetric SAR Images Using Dual-Attention Fusion Network,” in IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 19, pp. 1-5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cui et al., “Polarimetric Multipath Convolutional Neural Network for PolSAR Image Classification,” in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 60, pp. 1-18, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yamaguchi, T. Moriyama, M. Ishido, and H. Yamada, “Four-component scattering model for polarimetric SAR image decomposition,” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., vol. 43, no. 8, pp. 1699-1706, 2005. [CrossRef]

- W. An, “Research on Target Polarization Decomposition and Scattering Characteristic Extraction based on Polarized SAR,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Tsinghua University, 2010.

- W.T. An, and M.S. Lin, “A Reflection Symmetry Approximation of Multi-look Polarimetric SAR Data and its Application to Freeman-Durden Decomposition,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience & Remote Sensing, vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 3649-3660, 2019. [CrossRef]

- User Manual of Gaofen-3 Satellite Products, China Resources Satellite Application Center, 2016.

- J.S. Lee, “Digital image enhancement and noise filtering by use of local statistics,” IEEE Trans. on Pattern Analysis Machine Intelligence, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 165-168, 1980. [CrossRef]

- L.M. Novak, and M.C. Burl, “Optimal speckle reduction in polarimetric SAR imagery,” IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, vol. AES-26, no. 2, pp. 293-305, 1990. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen, Y.L. Chen, W.T. An, Y. Cui, and J. Yang, “Nonlocal filtering for polarimetric SAR data: A pretest approach,” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., vol. 49, pp. 1744–1754, 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, “Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification,” In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13, 2015.

- Y. Gao, W. Li, M. Zhang, J. Wang, W. Sun, R. Tao, and Q. Du, “Hyperspectral and multispectral classification for coastal wetland using depthwise feature interaction network,” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., vol. 60, pp. 1–15, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Bentes, D. Velotto, and B. Tings, “Ship classification in TerraSAR-X images with convolutional neural networks,” IEEE J. Ocean. Eng., vol. 43, pp. 258–266, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sunaga, R. Natsuaki, and A. Hirose, “Land form classification and similar land-shape discovery by using complex-valued convolutional neural networks,” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., vol. 57, pp. 7907–7917, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Hou, A. Wei, Q. Song, J. Lai, H. Wang, and F. Xu, “FUSAR-Ship: Building a high-resolution SAR-AIS matchup dataset of Gaofen-3 for ship detection and recognition,” Sci. China Inf. Sci., vol. 63, pp. 140303, 2020. [CrossRef]

- China Ocean Satellite Data Service System. https://osdds.nsoas.org.cn/ (last access: October 30 2023) .

- W. An, M. Lin, and H. Yang, “Modified Reflection Symmetry Decomposition and a New Polarimetric Product of GF-3,” IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, vo1. 19, pp. 1-5, 2022. [CrossRef]

| Scheme | parameters | Polarization features |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | NonP0, T22, T33, coe12, coe13, coe23 |

| 2 | 6 | P0, T22, T33, coe12, coe13, coe23 |

| 3 | 7 | P0, T11, T22, T33, coe12, coe13、coe23 |

| 4 | 7 | P0,T11, T22, T33, PS, PD, PV |

| 5 | 7 | P0, T11, T22, T33, P2, P3, PV |

| 6 | 9 | P0, T11, T22, T33, P2, P3, PS, PD, PV |

| 7 | 10 | P0, T11, T22, T33, Re(T12), Re(T13), Re(T23), Im(T12), Im(T13), Im(T23) |

| 8 | 21 | P0, T11, T22, T33, Re(T12), Re(T13), Re(T23), Im(T12), Im(T13), Im(T23), P2, P3, PS, PD, PV, x, y, a, b |

| Id | Date | Time (UTC) | Inc. angle (°) | Mode | Resolution | Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2021.09.14 | 22:14:11 | 30.98 | QPSI | 8 m | Train |

| 2 | 2021.09.14 | 22:14:06 | 30.97 | QPSI | 8 m | Train |

| 3 | 2021.10.13 | 10:05:35 | 37.71 | QPSI | 8 m | Train |

| 4 | 2017.10.12 | 22:07:36 | 36.89 | QPSI | 8 m | Test |

| Images | Nearshore water | Seawater | Spartina alterniflora | Tamarix | Reed | Tidal flat | Suaeda salsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20210914_1 | 500 | 400 | 1000 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| 20210914_2 | 500 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 500 | 0 |

| 20211013 | 0 | 400 | 0 | 500 | 500 | 0 | 500 |

| Total | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Classification accuracy Input scheme |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearshore water | 96.8 | 100 | 76.9 | 85.0 | 93.4 | 94.8 | 96.4 | 99.7 |

| Seawater | 96.9 | 100 | 99.5 | 98.8 | 98.7 | 99.2 | 98.7 | 99.7 |

| Spartina alterniflora | 96.8 | 100 | 93.3 | 93.2 | 85.2 | 92.9 | 95.5 | 100 |

| Tamarix | 100 | 97.6 | 99.0 | 93.8 | 75.9 | 100 | 96.0 | 96.7 |

| Reed | 94.5 | 98.3 | 93.4 | 63.7 | 93.3 | 94.9 | 99.2 | 100 |

| Tidal flat | 49.3 | 16.2 | 49.5 | 78.6 | 85.5 | 61.1 | 71.6 | 90.6 |

| Suaeda salsa | 50.8 | 92.7 | 98.4 | 97.6 | 95.1 | 99.4 | 98.2 | 100 |

| Indepent experiments Overall Accuracy | 83.59 | 86.40 | 87.14 | 87.24 | 89.59 | 91.76 | 93.66 | 98.10 |

| 81.41 | 85.19 | 84.27 | 87.19 | 88.91 | 91.76 | 91.84 | 96.54 | |

| 77.83 | 82.64 | 84.01 | 85.37 | 86.30 | 87.69 | 91.06 | 96.44 | |

| 73.66 | 81.86 | 83.67 | 85.29 | 86.19 | 86.61 | 89.29 | 96.40 | |

| 68.87 | 81.53 | 83.66 | 84.96 | 85.30 | 86.60 | 89.33 | 96.36 | |

| Average Overall Accuracy | 77.072 | 83.524 | 84.55 | 86.01 | 87.258 | 88.884 | 91.036 | 96.768 |

| Kappa coefficient | 0.8085 | 0.8413 | 0.8500 | 0.8512 | 0.8785 | 0.9038 | 0.9260 | 0.9778 |

| Classification accuracy Input scheme |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearshore water | 95.7 | 82.5 | 91.1 | 91.3 | 94.9 | 93.4 | 90.5 | 77.2 |

| Seawater | 97.7 | 98.8 | 99.8 | 98.5 | 99.4 | 99.3 | 99.3 | 99.6 |

| Spartina alterniflora | 96.6 | 95.9 | 94.1 | 95.7 | 93.5 | 94.9 | 98.7 | 100 |

| Tamarix | 98.5 | 100 | 1000 | 67.5 | 100 | 89.6 | 99.9 | 90.8 |

| Reed | 93.8 | 85.0 | 91.3 | 68.0 | 82.2 | 69.6 | 91.7 | 99.9 |

| Tidal flat | 28.5 | 42.0 | 25.7 | 88.5 | 67.2 | 95.8 | 71.4 | 99.8 |

| Suaeda salsa | 66.2 | 91.3 | 94.1 | 98.9 | 100 | 100 | 99.6 | 100 |

| Indepent experiments Overall Accuracy | 82.43 | 85.07 | 85.16 | 86.91 | 91.03 | 91.80 | 93.01 | 95.33 |

| 82.21 | 85.03 | 84.66 | 86.63 | 88.99 | 90.61 | 92.03 | 94.93 | |

| 81.44 | 84.74 | 84.10 | 86.57 | 87.50 | 90.54 | 91.94 | 94.76 | |

| 79.44 | 82.06 | 83.64 | 84.90 | 86.77 | 90.43 | 91.29 | 92.96 | |

| 77.53 | 81.93 | 83.41 | 80.47 | 86.83 | 90.37 | 89.94 | 91.97 | |

| Average Overall Accuracy | 80.61 | 83.766 | 84.194 | 85.096 | 88.224 | 90.75 | 91.642 | 93.99 |

| Kappa coefficient | 0.7950 | 0.8258 | 0.8268 | 0.8473 | 0.8953 | 0.9043 | 0.9185 | 0.9455 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).