Submitted:

08 April 2024

Posted:

09 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

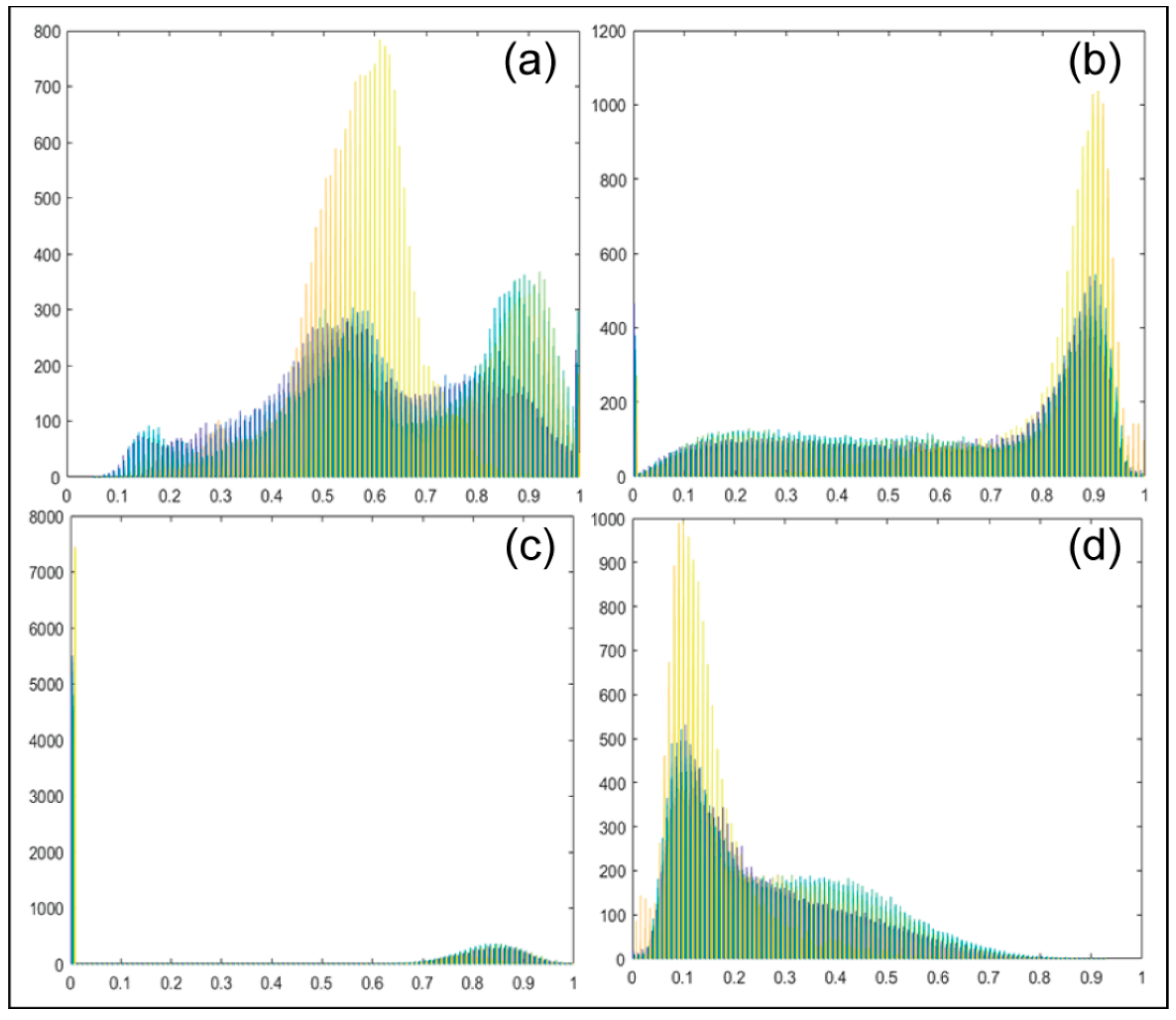

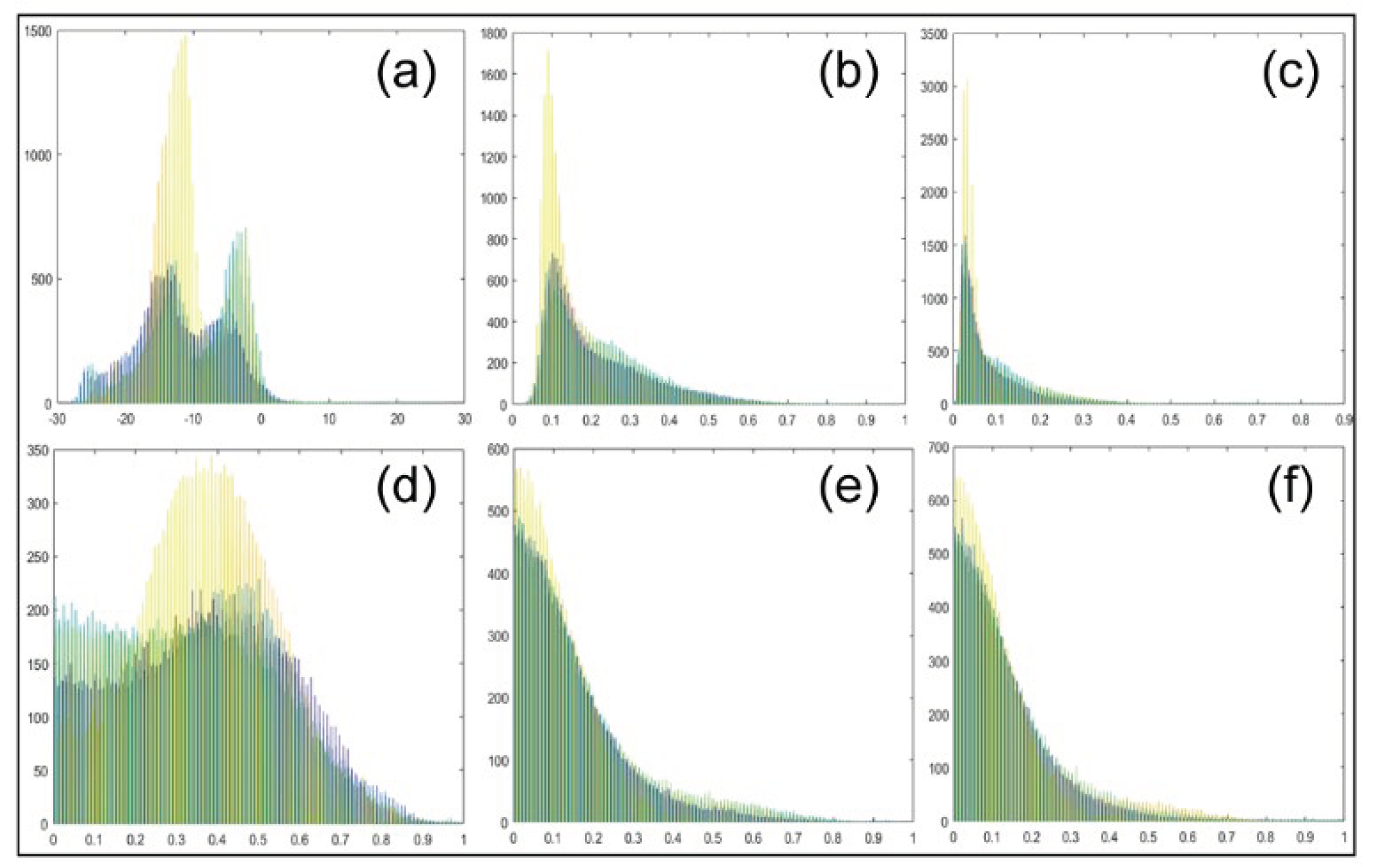

2.1. Polarization Decomposition Method Based on Polarimetric Scattering Features

2.2. Vertical, Horizontal, Left-Handed Circular, Right-Handed Circular Polarization Methods

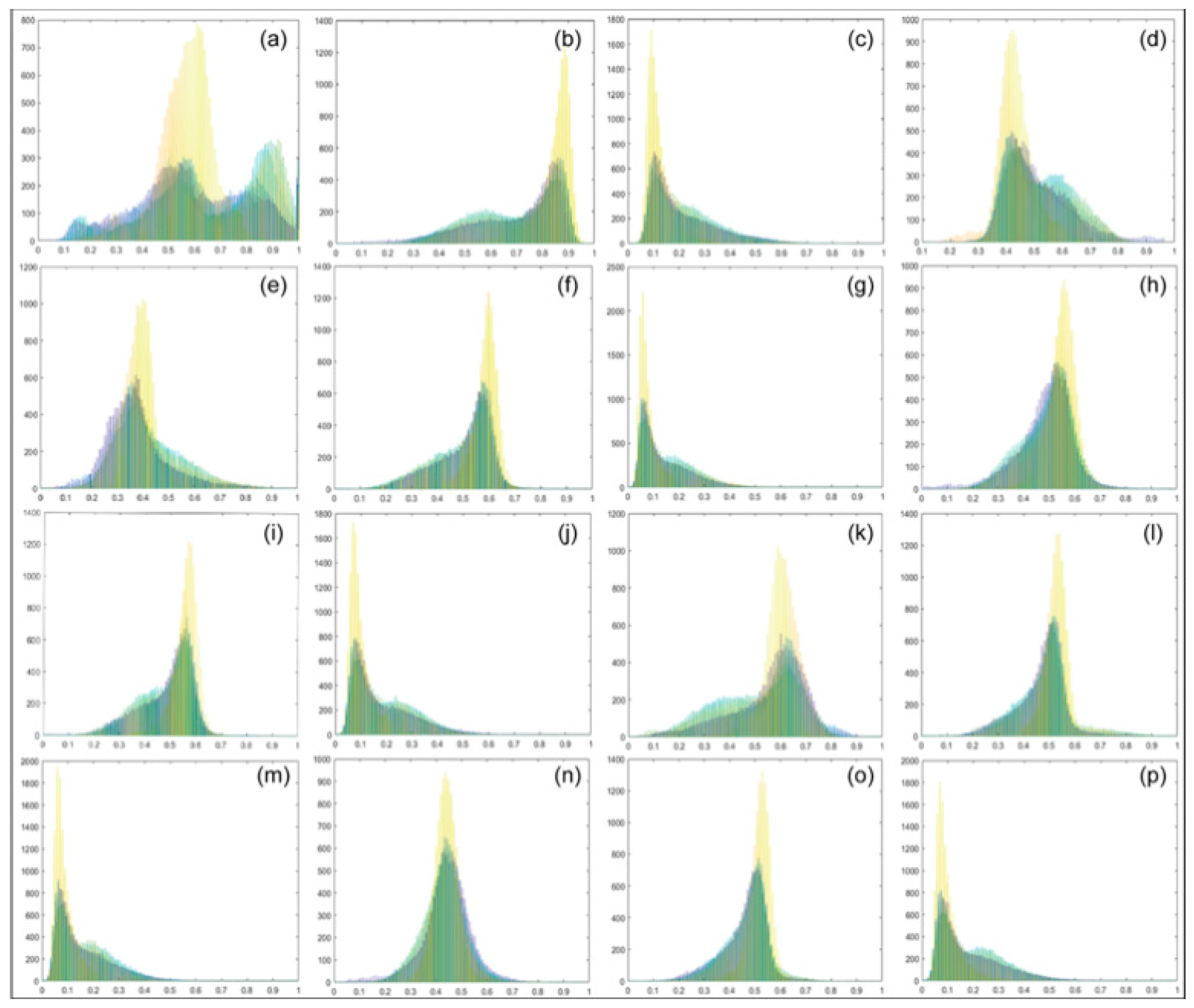

2.3. Input Feature Normalization and Design of Three Schemes

2.4. Experiment and Pre-Processing

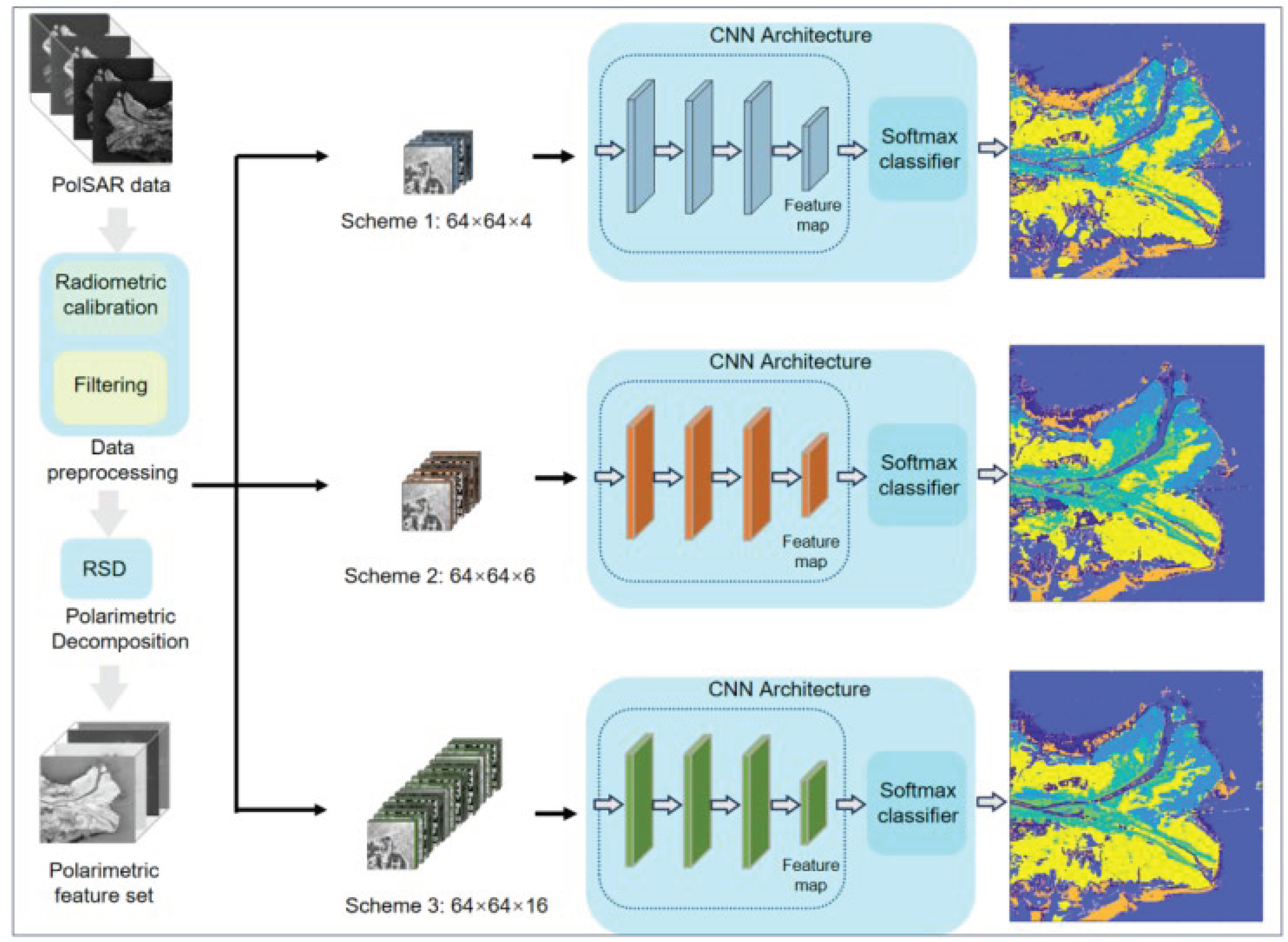

2.5. Classification Process of Polarization Scattering Characteristics Using Deep Learning

| Pseudocodes of the experiment: A deep learning classification scheme for PolSAR image based on polarimetric features |

|

Input: GF-3 PolSAR images. Output: Predict label Ytest {y1, y2, ... ym} 1: Processing GF-3 PolSAR images. 2: Polarimetric decomposition. 3: Extract polarimetric features. 4: Feature normalization. 5: Three schemes are proposed based on the previous studies and scattering mechanisms. 6: Randomly select a certain proportion of training samples (Patch_Xtrain: {Patch_x1, Patch_x2, ..., Patch_xn}, the remaining labeled samples are used as validate samples 7: Inputting Patch_xi into CNN. for i < N do the train one time. If good fitting, then Save model, and break. else if over-fitting or under-fitting, then Adjust parameters includes, i.e., learning rate, bias. End 8: Predict Label: Y = Softmax (Patch_Xtrain) 9: Test images are input to the model, and do predict to the patches of all pixels. 10: Do method evaluation, i.e., Statistic OA, AA and Kappa coefficient. |

3. Experimental and Result Analysis

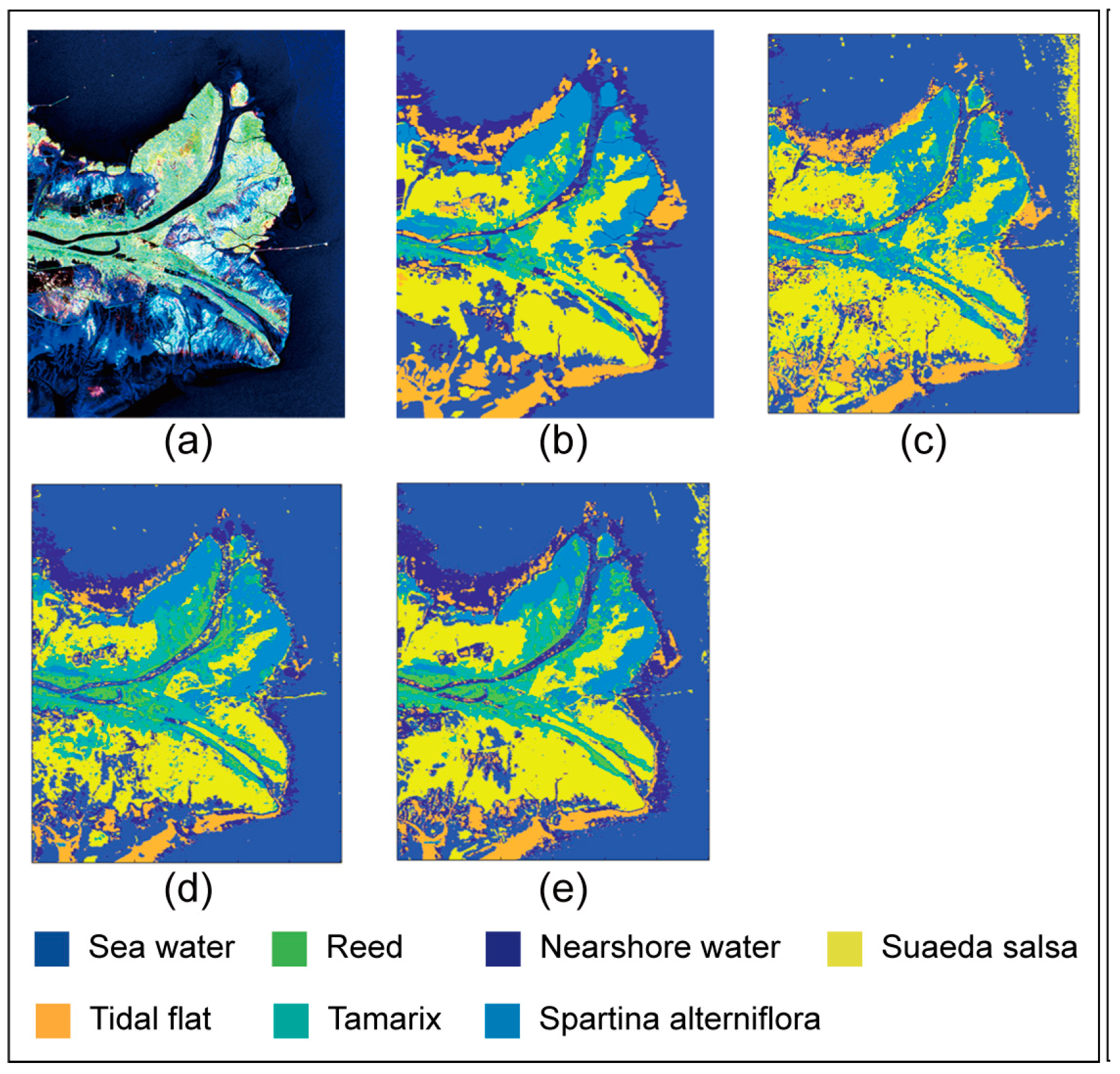

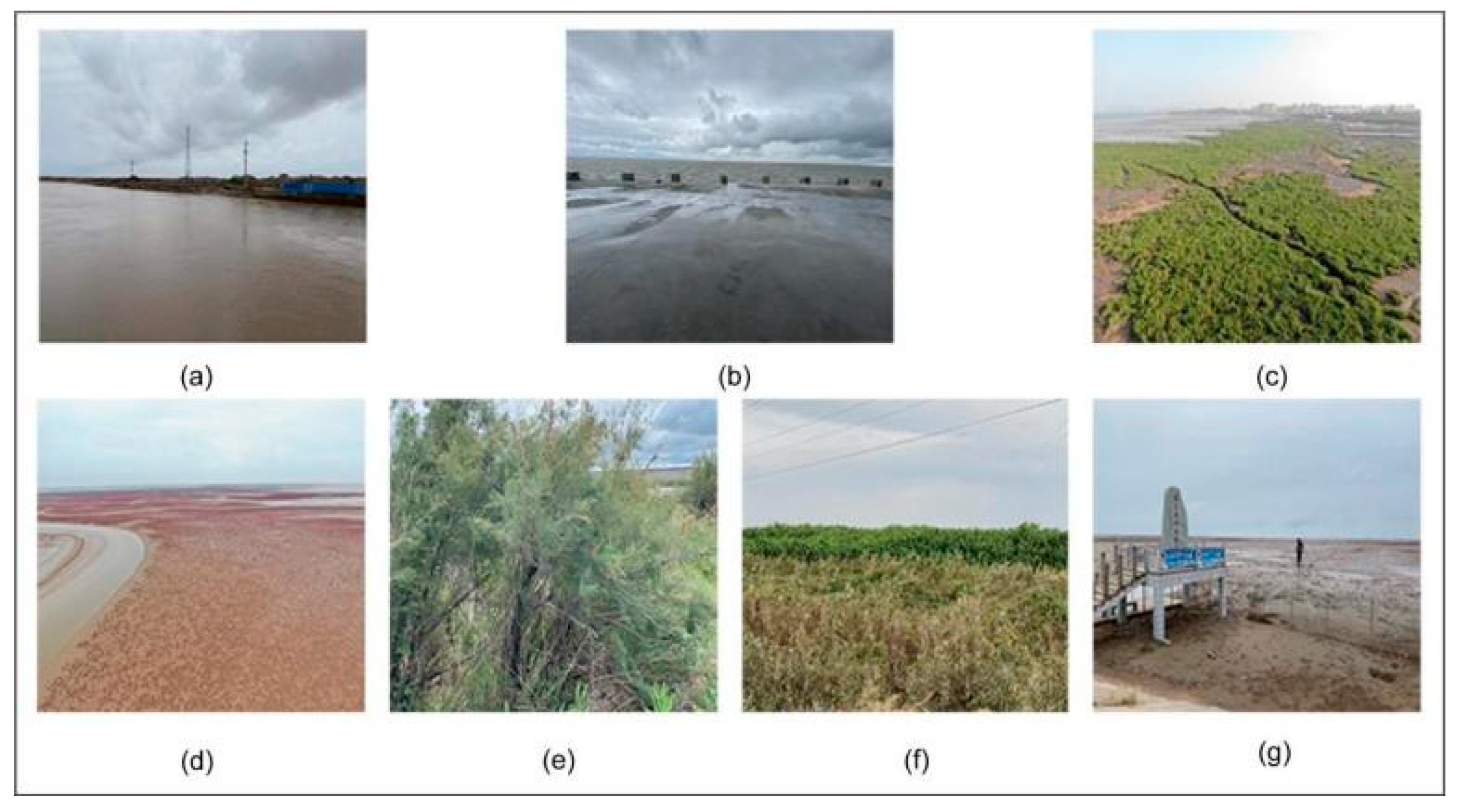

3.1. Study Area and Dataset

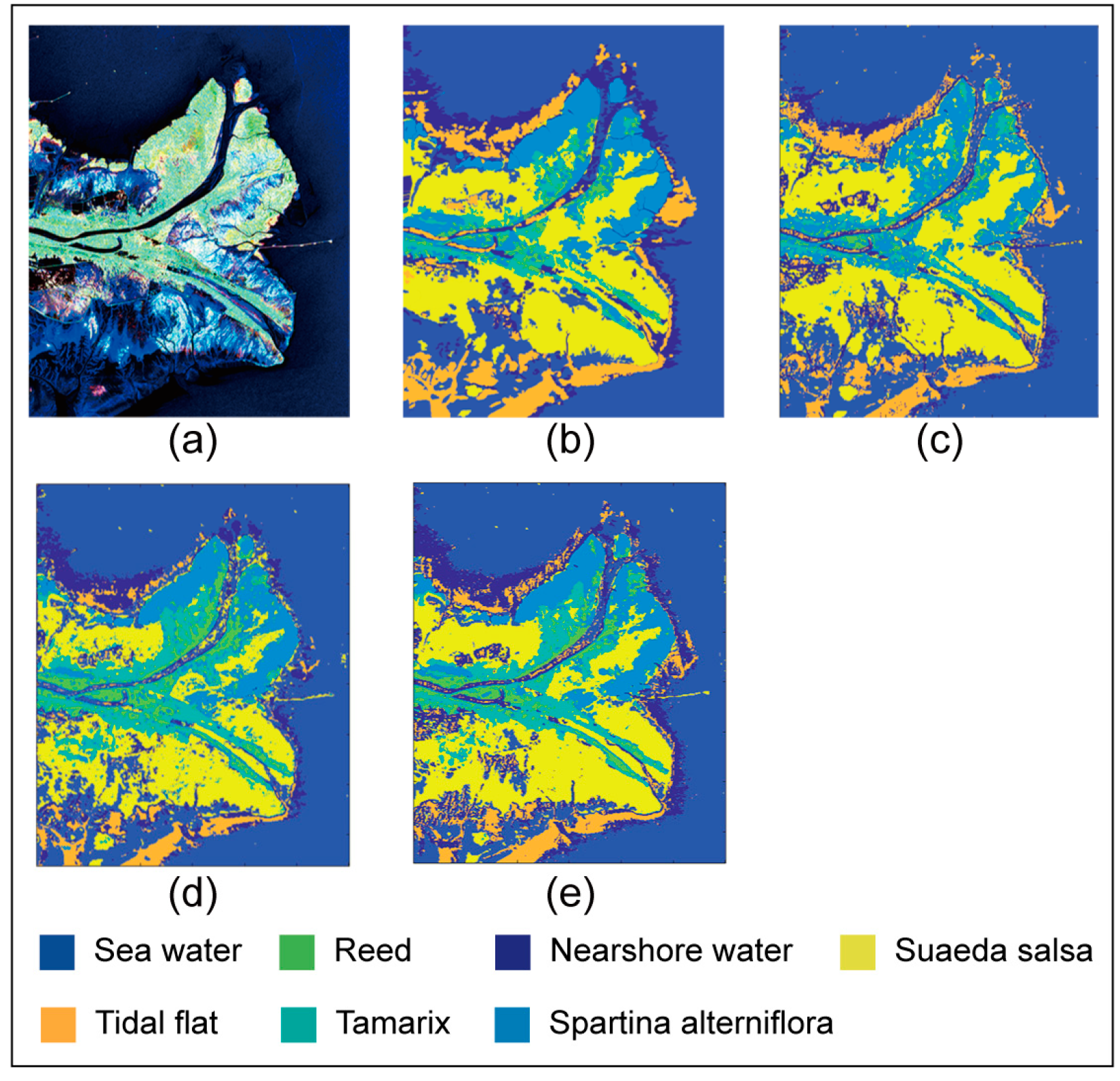

3.2. Classification Results of the Yellow River Delta on AlexNet

3.3. Classification Results of the Yellow River Delta on VGG16

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Lee, J.S.; Grunes, M.R.; Pottier, E. Quantitative comparison of classification capability: Fully polarimetric versus dual and single-polarization SAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 2343–2351. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yin, Q. A multichannel fusion convolutional neural network based on scattering mechanism for PolSAR image classification. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Nengyuan Pi, Yiming. PolSAR image classification based on deep polarimetric feature and contextual information. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing 2019, 13.

- Dong, H.; Zhang, L.; Lu, D.; Zou, B. Attention-based polarimetric feature selection convolutional network forPolSAR image classification. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonnqvist, A.; Rauste, Y.; Molinier, M.; Hame, T. Polarimetric SAR data in land cover mapping in boreal zone. IEEE Trans. Geosci. RemoteSens. 2010, 48, 3652–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNairn, H.; Shang, J.; Jiao, X.; Champagne, C. The contribution of ALOS PALSAR multipolarization and polarimetric data to crop classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 3981–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Yeh, A.G.-O.; Li, X.; Lin, Z. A novel algorithm for land use and land cover classification using RADARSAT-2 polarimetric SAR data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 118, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloude, S.R.; Pottier, E. A review of target decomposition theorems in radar polarimetry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1996, 34, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloude, S.R.; Pottier, E. An entropy based classification scheme for land applications of polarimetric SAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1997, 35, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardeux, C.; et al. Support vector machine for multifrequency SAR polarimetric data classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 4143–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, C.; Siqueira, P.; Clewley, D.; Lucas, R. Classification of forest composition using polarimetric decomposition in multiple landscapes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 131, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; et al. Unsupervised classification using polarimetric decomposition and the complex Wishart classifier. IEEE Trans. Geosci.Remote Sens. 1999, 37, 2249–2258. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, W.B.; Freitas, C.C.; Sant’Anna, S.J.S.; Frery, A.C. Classification of segments in PolSAR imagery by minimum stochastic distances between Wishart distributions. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2013, 6, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Kuang, G.Y.; Li, J.; Sui, L.C.; Li, D.G. Unsupervised land cover/land use classification using PolSAR imagery based on scattering similarity. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 51, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.; Ji, K.F.; Yu, W.X.; Su, Y. Region-based classification of Polarimetric SAR imaged using Wishart MRF. IEEE Trans. Geosci.Remote Sens. Lett. 2008, 5, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; et al. Superpixel-based classification with an adaptive number of classes for polarimetric SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 51, 907–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloude, S.R.; Pottier, E. A review of target decomposition theorems in radar polarimety [J]. IEEE TGRS 1996, 34, 498–518. [Google Scholar]

- Krogager, E. New decomposition of the radar target scattering matrix [J]. Electronics Letters 1990, 26, 1525–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.; Durden, S.L. A three-component scattering model for polarimetric SAR data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing l998, 36, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshio Yamaguchi. Four-component scattering model for polarimetric SAR image decomposition. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2005, 43, 1699–l706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W T, A.; Lin, M.S. A reflection symmetry approximation of multi-look polarimetric SAR data and its application to freeman-durden decomposition[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience & Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 3649–3660. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, A.; Durden, S.L. A three-component scattering model for polarimetric SAR data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1998, 36, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, J.J.; Arii, M.; Kim, Y. Model-based decomposition of polarimetric SAR covariance matrices constrained for nonnegative eigenvalues. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 3452–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloude, S.R.; Pottier, E. An entropy based classification scheme for land applications of polarimetric SAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1997, 35, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynen, J.R. Physical reality of radar targets. Proc. SPIE 1993, 1748, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, W.L.; Leung, L.K. Feature motivated polarization scattering matrix decomposition. in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Radar, vol. 1, May 1990, pp. 549–557. 19 May.

- Krogager, E. New decomposition of the radar target scattering matrix. Electron. Lett. 1990, 26, 1525–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Huang, K.; Yang, J.; Li, P. A deep reinforcement learning-based framework for PolSAR imagery classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yin, Q. A multichannel fusion convolutional neural network based on scattering mechanism for PolSAR image classification. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, B.; Chanussot, J.; Jiao, L. A mutual information-based self-supervised learning model for PolSAR land cover classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 59, 9224–9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E.; Osindero; Teh, Y.-W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Comput. 2006, 18, 1527–1554. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent P; Larochelle H; Lajoie I; Bengio Y, Manzagol P-A. Stacked denoising autoencoders: Learning useful representations in a deep network with a local denoising criterion. J. Mach. Learn. 2010, 11, 3371–3408.

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Communications of the ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 25th international conference on neural information processing systems, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–6 December 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich. A going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, L.; Liu, F. Wishart deep stacking network for fast POLSAR image classifification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2016, 25, 3273–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Jiao, L.; Tang, X. Task-oriented GAN for PolSAR image classifification and clustering. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 2707–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, C.; Shi, D.; Zhang, D.; Hou, B. Wishart RBM based DBN for polarimetric synthetic radar data classifification. In Proceedings of the IEEE Int. Geosci. Remote Sens. Symp. (IGARSS); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L. Stacked sparse autoencoder modeling using the synergy of airborne LiDAR and satellite optical and SAR data to map forest above-ground biomass. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. 2017, 10, 5569–5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, W.; Zhang, D. Stacked sparse autoencoder in PolSAR data classifification using local spatial information. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2016, 13, 1359–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, J.; Guan, H.; Wang, C. Automated detection of three-dimensional cars in mobile laser scanning point clouds using DBM-Hough-forests. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 4130–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, G.; Gu, Y. Deep learning-based classifification of hyperspectral data. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 2094–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, Z.; Wu, J. A hierarchical oil tank detector with deep surrounding features for high-resolution optical satellite imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 4895–4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Li, Q. Hyperspectral imagery classifification using sparse representations of convolutional neural network features. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, J.; Guan, H.; Jia, F.; Wang, C. Learning hierarchical features for automated extraction of road markings from 3-D mobile LiDAR point clouds. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, K.; Lin, S.; Hou, B. Multilayer feature learning for polarimetric synthetic radar data classifification. in Proc. IEEE IGARSS, Jul. 2014, pp. 2818–2821.

- Huynen, J.R. Physical reality of radar targets. Proc. SPIE 1993, 1748, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Hou, Z.; Dong, Z.; He, Z. Performance analysis of wavenumber domain algorithms for highly squinted SAR. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2023, 16, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.A.F.; Mao, Y.; Luo, Q.; Yao, B. A fine PolSAR terrain classification algorithm using the texture feature fusion-based improved convolutional autoencoder. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, F.; Jin, Y.-Q. Polarimetric SAR image classifification using deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2016, 13, 1935–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-W.; Tao, C.-S. PolSAR image classifification using polarimetric-feature-driven deep convolutional neural network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 15, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Lin, M.; Yang, H. Modified reflection symmetry decomposition and a new polarimetric product of GF-3. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Wentao. Polarimetric decomposition and scattering characteristic extraction of polarimetric SAR. Ph.D. Dissertation, Tusinghua University, Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. On Theoretical Problems in Radar Polarimetry. Ph.D Dissertation, Niigata University, Niigata, Japan, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- User Manual of Gaofen-3 Satellite Products, China Resources Satellite Application Center, 2016.

- Chen, J.; Chen, Y.L.; An, W.T.; Cui, Y.; Yang, J. Nonlocal filtering for polarimetric SAR data: A pretest approach. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; An, W.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, L.; Xie, C. Wetlands Classification Using Quad-Polarimetric Synthetic Aperture Radar through Convolutional Neural Networks Based on Polarimetric Features. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Shuaiying Zhang received the B.S. and M.S. degrees from the Henan Polytechnic University, Jiaozuo, China and National Marine Environmental Forecasting Center, Beijing, China in 2020 and 2023, respectively. He is pursuing the Ph.D. degree with the College of Electronic Science and Engineering, National University of Defense Technology (NUDT), Changsha, China. His research interests include PolSAR data processing and Radar image interpretation. |

|

Lizhen Cui received the B.S. degree in environmental science from Hebei Agricultural University, China, in 2018. She is currently pursuing the Ph.D. degree with ecology at the Laboratory of Terrestrial Ecosystems, College of Life Sciences, the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China since 2018. She is interested in the restoration and sustainable development of alpine grassland ecosystems. |

|

Wentao An received the B.S. degree in communication engineering from Nankai University, Tianjin, China, in 2003, and the Ph.D. degree in electronic engineering from Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, in 2010. He is currently a Researcher with the Department of Systematic Engineering, National Satellite Ocean Application Service, Beijing. His research interests include polarimetric SAR data. |

|

Zhen Dong was born in Anhui, China, in Sepember 1973. He received the Ph.D. degree in electrical engineering from National University of Defense Technology (NUDT), Changsha, in 2001. He is currently a Professor with the College of Electronic Science and Engineering, NUDT. His recent research interests include SAR system design and processing, Ground Moving Target Indication (GMTI), and very-high-resolution SAR imaging. |

| Scheme | parameters | Polarization features |

| 1 | 4 | P0, PS, PD, PV |

| 2 | 6 | NonP0, T22, T33, coeT12, coeT13, coeT23 |

| 3 | 16 | P0, T12, T23, T23, H(T12), H(T13), H(T23), L(T12), L(T13), L(T23), V(T12), V(T13), V(T23), R(T12), R(T13), R(T23) |

| Images | Nearshore water | Seawater | Spartina alterniflora | Tamarix | Reed | Tidal flat | Suaeda salsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20210914_1 | 500 | 400 | 1000 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| 20210914_2 | 500 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 500 | 0 |

| 20211013 | 0 | 400 | 0 | 500 | 500 | 0 | 500 |

| Total | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Classification accuracy Input scheme |

1 | 2 | 3 |

| Nearshore water | 83.4 | 96.8 | 100 |

| Seawater | 98.7 | 96.9 | 99.60 |

| Spartina alterniflora | 87.0 | 96.8 | 93.3 |

| Tamarix | 40.1 | 100 | 100 |

| Reed | 50.4 | 94.5 | 68.50 |

| Tidal flat | 61.8 | 49.3 | 44.6 |

| Suaeda salsa | 98.2 | 50.8 | 96.8 |

| Indepent experiments Overall Accuracy | 74.23 | 83.59 | 86.11 |

| 71.36 | 81.41 | 81.53 | |

| 70.41 | 77.83 | 77.04 | |

| 68 | 73.66 | 73.73 | |

| 67.84 | 68.87 | 71.99 | |

| Average Overall Accuracy | 70.368 | 77.072 | 78.08 |

| Kappa coefficient | 0.6993 | 0.8085 | 0.8380 |

| Classification accuracy Input scheme |

1 | 2 | 3 |

| Nearshore water | 89.3 | 95.7 | 95.6 |

| Seawater | 99.4 | 97.7 | 99.7 |

| Spartina alterniflora | 87.6 | 96.6 | 95.9 |

| Tamarix | 40.2 | 98.5 | 100 |

| Reed | 26.1 | 93.8 | 44.7 |

| Tidal flat | 73.2 | 28.5 | 58.3 |

| Suaeda salsa | 100 | 66.2 | 94.1 |

| Indepent experiments overall accuracy | 73.69 | 82.43 | 84.04 |

| 72.8 | 82.21 | 83.57 | |

| 69.7 | 81.44 | 82.07 | |

| 68.66 | 79.44 | 81.54 | |

| 67.6 | 77.53 | 80.11 | |

| Average overall accuracy | 70.49 | 80.61 | 82.266 |

| Kappa coefficient | 0.6930 | 0.7950 | 0.8138 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).