1. Introduction

The quality of seedlings has significant implications for the growth, yield, and quality of crops[

1,

2]. To cultivate high-quality seedlings, besides environmental factors such as light, temperature, and moisture, excellent germplasm resources and suitable substrates are equally indispensable[

3]. Among these factors, substrate selection is crucial for agricultural practitioners. In the current substrate market, peat-based substrates still occupy a considerable proportion[

4]. From an environmental perspective, peat, as a non-renewable resource, suffers from excessive exploitation, leading to severe ecological pressures and the release of carbon into the atmosphere[

5]. From a production standpoint, peat is generally priced at around 0.5 RMB/L, while substrate prices in the market are approximately 0.7 RMB/L. The extensive use of peat in substrates undoubtedly increases the production cost of substrates[

6]. Therefore, finding a suitable alternative to peat for substrate preparation has long been a focal point for many scholars[

7].

Based on previous investigations into Chinese vegetable seedling substrate patents, we found that the most frequently occurring ingredients in substrate formulations with the potential to replace peat are livestock and poultry manure[

8], straw[

9], and coconut coir[

10]. From the perspective of production convenience, both livestock and poultry manure[

11] and straw[

5] need to undergo composting to form corresponding organic fertilizers before they can participate in substrate preparation. However, to meet substrate-related standards, organic fertilizers with relatively high pH and electrical conductivity (EC) are difficult to apply in large quantities to substrate preparation[

12]. Coconut coir, after desalination treatment, can significantly reduce its EC value, eliminating salt stress on crops[

13]. Additionally, coconut coir's physical properties, such as bulk density and porosity, are more suitable for the growth needs of crop seedlings compared to organic fertilizers[

14,

15]. Therefore, in substrate-related research, coconut coir is increasingly seen as a material with the potential to replace peat[

16].

However, coconut coir also has its own drawbacks in the substrate preparation process. The main issue lies in the fact that after desalination treatment, coconut coir's nutrient content is hardly sufficient to meet the normal growth requirements of crop seedlings. To address this issue, the addition of exogenous nutrients is a relatively easy-to-implement approach. Based on previous relevant studies, we hypothesize that composted rice husks, pig manure, and humic acid may have the potential to address the problem of poor growth of crop seedlings in coconut coir substrates due to insufficient nutrients. In order to comprehensively evaluate the suitability of coconut coir substrates supplemented with nutrients from different sources for different crops and to align with the practical application of substrates in agricultural production, this study selected cucumber and rice as cultivation objects. The aim is to provide a comprehensive substrate that meets the growth requirements of crop seedlings under different cultivation conditions, and to provide a more comprehensive research direction and technical basis for further reducing the proportion of peat in substrates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The peat used in this study was purchased from Pindstrup, Denmark. The vermiculite was obtained from Guangdong Chenxing Agricultural Co., Ltd. Coconut coir was sourced from Xiamen Xiantu Horticultural Technology Co., Ltd. Organic fertilizer derived from pig manure was procured from Hangzhou Xiaoshan Huirun Compound Organic Fertilizer Co., Ltd. Agricultural humic acid was acquired from Dachen Nursery Cultivation Center, Han Gu Management Area, Tangshan City. The composted rice husks were prepared in-house at the Organic Cycling Research Institute (Suzhou), China Agricultural University. The cucumber variety tested was 'Shenqing 1', while the rice variety examined was 'Nanjing 46'. The basic physicochemical properties of the materials are detailed in

Table 1.

2.2. Methods

The experiment was conducted on October 9, 2023, at the Artificial Climate and Plant Cultivation Center of the Institute of Organic Recycling, China Agricultural University (Suzhou), with all necessary data collected by November 20, 2023. Referring to relevant studies on strawberry substrates conducted by the Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences and considering economic costs, this experiment focused on the formulation of "30% peat + 50% coconut coir + 10% vermiculite + 10% nutrient source" as the research subject. Three treatments were designed based on different nutrient sources, namely 10% pig manure organic fertilizer (T1), 10% decomposed rice husk (T2), and 10% agricultural humic acid (T3). Simultaneously, two control treatments were established using "90% peat + 10% vermiculite" and "30% peat + 60% coconut coir + 10% vermiculite," denoted as CK1 and CK2, respectively. This study consisted of two experiments: cucumber seedling substrate experiment and rice seedling substrate experiment.

2.2.1. Pre-Treatment of Test Material

Coconut husk was obtained and processed by soaking in water at a ratio of 6.67 L per kilogram for 30 minutes to achieve a final moisture content of 86.96%. The husks were then air-dried naturally. Other raw materials were also air-dried and stored for subsequent use. Cucumber seeds were disinfected using a 10% sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 minutes. Rice seeds were subjected to a pre-germination treatment by soaking in water at 30°C for 24 hours followed by a 48-hour germination period. The soaking solution for rice seeds was prepared at a concentration of 10 g/L of Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis (Bti).

2.2.2. Determination of Seed Germination Effect

Following the methods prescribed in Chinese agricultural industry standard NY/T 525-2021and incorporating the findings of Kong

et al.[

17], radish seeds were employed to determine the germination index (GI) of each treatment's seedling substrate. Ten milliliters of the extraction solution from each treatment's seedling substrate were added to Petri dishes lined with 9 cm filter paper, with distilled water used as the control (CKw). Ten seeds were placed in each Petri dish and incubated in a constant temperature chamber at 25 ℃ in darkness for 48 hours. Post-incubation assessment criteria included germination rate, total root length, and seedling root fresh weight. Germination index was calculated using germination rate and total root length, with the calculation formula as follows:

2.2.3. Cucumber Seedling Substrate Test

Following the methodology outlined by Liu

et al.[

18], the research was conducted using the tray-seedling method. Each well in the tray contained one cucumber seed, with a total of 50 wells per tray. The experiment was arranged in a randomized complete block design with three replicates per treatment, each tray serving as one replicate. The trays were placed in a growth chamber with controlled conditions set to 25°C and 80% humidity for a period of 15 days. During the experimental period, each well was irrigated with 1.5 L of distilled water, and an additional 500 mL of water was added every 48 hours to maintain consistent moisture levels.

2.2.4. Rice Seedling Substrate Test

In accordance with the methodology outlined by Ge

et al.[

19], the study was conducted using rice-specific seedling trays. Rice seeds were sown at a depth of 0.2 cm from the surface of the substrate, with 50 seeds sown per tray. Each treatment was replicated three times, with each tray constituting one replicate. The seedling trays were placed in a growth chamber maintained at 30°C and 80% humidity for 28 days. Each tray was uniformly watered with 1 L of water upon seeding, followed by daily watering with an additional 1 L of water throughout the experimental period.

2.3. Measurement Indicators and Methods

2.3.1. Physicochemical Properties of Seedling Substrates

Following the methods prescribed in the agricultural industry standard NY/T 2118-2012, the bulk density, water holding capacity, air-filled porosity, and total porosity of the seedling substrate were determined using the ring knife method. Additionally, the air-water ratio was calculated based on the ratio of air-filled porosity to water holding capacity. Specifically, the hydrolyzed nitrogen content was measured using the alkali diffusion method, the available phosphorus content was determined using the molybdenum antimony anti-spectrophotometric method, the readily available potassium content was measured using flame photometry, and the organic matter content was determined using the potassium dichromate volumetric method. pH and EC values were measured using electrode methods.

2.3.2. Growth Indicators for Young Cucumber Seedlings

15 cucumber seedlings were taken from each hole tray 15 days after seeding and their height was measured with a straightedge and stem thickness was assessed with a vernier caliper. The cucumber seedlings' leaf area was calculated using the length and width coefficient method; the cucumber seedlings' completely expanded leaves were measured using a chlorophyll content meter, and the chlorophyll content was reported as SPAD values. Using a brush, the seedling substrates adhered to the 15 cucumber seedlings were removed and stored in a sealed container at 4°C for testing. A root scanner (WinRHIZO) was used to measure the root length and root surface area of cucumber seedlings. The above-ground and below-ground weights of cucumber seedlings were measured using an electronic balance. Subsequently, they were killed at 90 ℃ and dried at 60 ℃ to a constant weight. The strong seedling index was calculated using plant height, stem thickness and plant weight, which provides a relatively comprehensive picture of the overall quality of cucumber seedlings. The formula is shown below:

2.3.3. Growth Indicators for Young Rice Seedlings

Rice seeds were germinated and cultivated under controlled conditions in a growth chamber. After 5 days of cultivation, the number of emerged rice seedlings was recorded to calculate the emergence rate. After 28 days of cultivation, 15 randomly selected rice seedlings from the non-boundary areas of each treatment in the nursery trays were measured for various growth parameters, including plant height, stem diameter, root length, and fresh/dry weight of aboveground (and belowground) parts, following the methodology outlined in "Growth Indicators for Young Cucumber Seedlings".

2.3.4. Seedling Effectiveness Evaluation Survey

Ten experienced agricultural technicians engaged in agricultural production were invited to evaluate and score both substrate quality and seedling growth conditions. Evaluation criteria comprised seedling appearance, root development, substrate texture, and willingness to use. Scoring criteria were set as follows: 0 (poor), 1 (fair), 3 (good), and 5 (excellent). Participants were provided with standardized evaluation forms detailing each criterion and corresponding scoring scale. Prior to assessment, participants underwent training sessions to ensure consistency and accuracy in scoring. The evaluation process involved individual assessments of substrate quality and seedling growth conditions by each technician. Evaluations were conducted in a controlled environment to minimize external influences. Following completion of evaluations, scores from all technicians were aggregated and analyzed statistically using appropriate methods to determine overall ratings for both substrate quality and seedling growth conditions.

2.3.5. Data Statistics and Analysis

Using DPS software[

20], the trial's raw data were submitted to one-way ANOVA after being tallied using Excel 2019.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Seed Germination

The results, as depicted in

Table 2, illustrate a 100% germination rate across all treatments, indicating the favorable effect of coconut coir substrate on seed germination promotion. Regarding root length, all substrate treatments exhibited an increase compared to the control (CK). Specifically, while the difference in root length between T2 and T3 treatments was not significant, both were significantly higher than the T1 treatment. In detail, compared to CKw, CK1 showed a 13.89% increase in root length, CK2 showed a 13.24% increase, T1 showed an 18.49% increase, T2 showed a 29.03% increase, and T3 showed a 28.60% increase. Lastly, concerning the germination index, treatments with different nutrient sources (T1, T2, T3) displayed a decrease relative to CK1 and CK2, although the differences between T2, T3, and the control group were not significant.

3.2. Physical Properties of Seedling Substrates

Table 3 illustrates the bulk density results, indicating significant increases in bulk density for treatments T1, T2, and T3 compared to CK1 and CK2. Notably, treatment T3 exhibited the highest bulk density, measuring 0.26g·cm⁻³, which represents a 36.84% increase over CK1 (0.19 g·cm⁻³) and an 18.18% increase over CK2 (0.22 g·cm⁻³). Regarding air-filled pore space, treatments T1, T2, and T3 showed significantly lower values compared to CK1 and CK2. Particularly, CK1 exhibited the highest air-filled pore space at 43.45%, while treatment T3 had the lowest at 27.33%. Compared to CK1, treatments T1, T2, and T3 decreased by 15.64%, 16.09%, and 16.16%, respectively. Concerning water-holding pore space, treatments T1, T2, and T3 showed significant increases compared to CK1 but were significantly lower than CK2. Compared to CK1, treatments T1, T2, and T3 increased by 16.78%, 18.48%, and 9.68%, respectively. In terms of total pore space, CK2 exhibited the highest value at 83.49%, while treatment T3 had a total pore space of 78.65%, significantly lower than the other treatments. Compared to CK1, treatments T1, T2, and T3 increased by 7.00%, 9.09%, and 7.56%, respectively.

3.3. Chemical Properties of Seedling Substrates

Table 4 presents the results of various soil parameters under different treatments. In terms of pH, treatments T1, T2, and T3 exhibited significantly higher values compared to CK1 and CK2. Particularly, treatment T2 demonstrated the highest pH value at 6.47, which was 15.79% higher than that of CK1 (pH = 5.60) and 21.58% higher than that of CK2 (pH = 5.53). Regarding electrical conductivity (EC), treatments T1, T2, and T3 showed significantly higher values than CK1. Notably, treatments T2 and T3 displayed the highest EC values at 0.58 mS·cm

-1, which were 7.41% higher than CK1 (EC = 0.54 mS·cm

-1) and 3.57% higher than CK2 (EC = 0.56 mS·cm

-1). For alkali hydrolyzable nitrogen, treatment T2 showed significantly higher values than CK1 and CK2, reaching the maximum value among all treatments at 0.60 g·kg

-1. In terms of available phosphorus, there were no significant differences between treatments T1, T2, T3, and CK2, while treatments T2 and T3 were significantly lower than CK1. As for available potassium, treatments T2 and T3 showed significantly higher values compared to CK1 and CK2. Particularly, treatment T3 exhibited the highest content of available potassium at 10.43 g·kg

-1. Regarding organic matter, treatments T1, T2, and T3 displayed significantly lower values compared to CK1 and CK2. Notably, treatment T1 exhibited the lowest organic matter content at 55.66%.

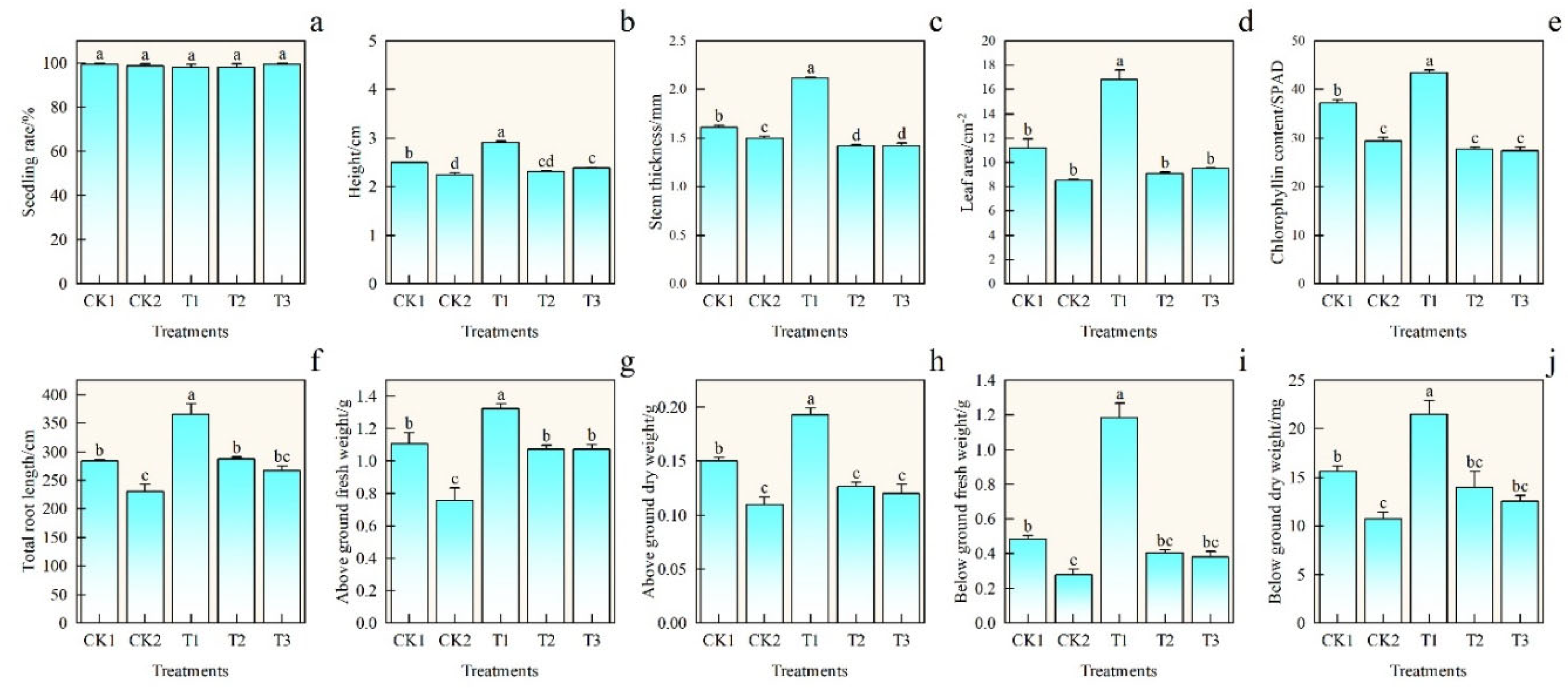

3.4. Cucumber Seedling Growth

The growth parameters of cucumber seedlings are presented in

Figure 1. It can be observed that different substrates did not significantly affect the emergence rate of cucumber seedlings (

Figure 1a), with all treatments exhibiting an emergence rate of over 98.00%. However, concerning plant height (

Figure 1b), stem diameter (

Figure 1c), chlorophyll content (

Figure 1d), and aboveground dry weight (

Figure 1h), all treatments, except for T1, showed significantly lower performance compared to the CK1 treatment. In terms of the aforementioned parameters, T1 treatment exhibited a significant increase of 16.99%, 30.06%, 18.13%, and 28.57%, respectively, compared to the CK1 treatment. Moreover, T1 treatment also demonstrated significantly higher performance in other growth parameters compared to the other treatments. T2 and T3 treatments did not exhibit significant differences compared to the CK2 treatment in terms of leaf area, chlorophyll content, aboveground dry weight, and belowground biomass. However, in stem diameter, they showed a significant decrease compared to the CK2 treatment, with T3 treatment exhibiting a significant increase of 5.78% only in plant height compared to the CK2 treatment.

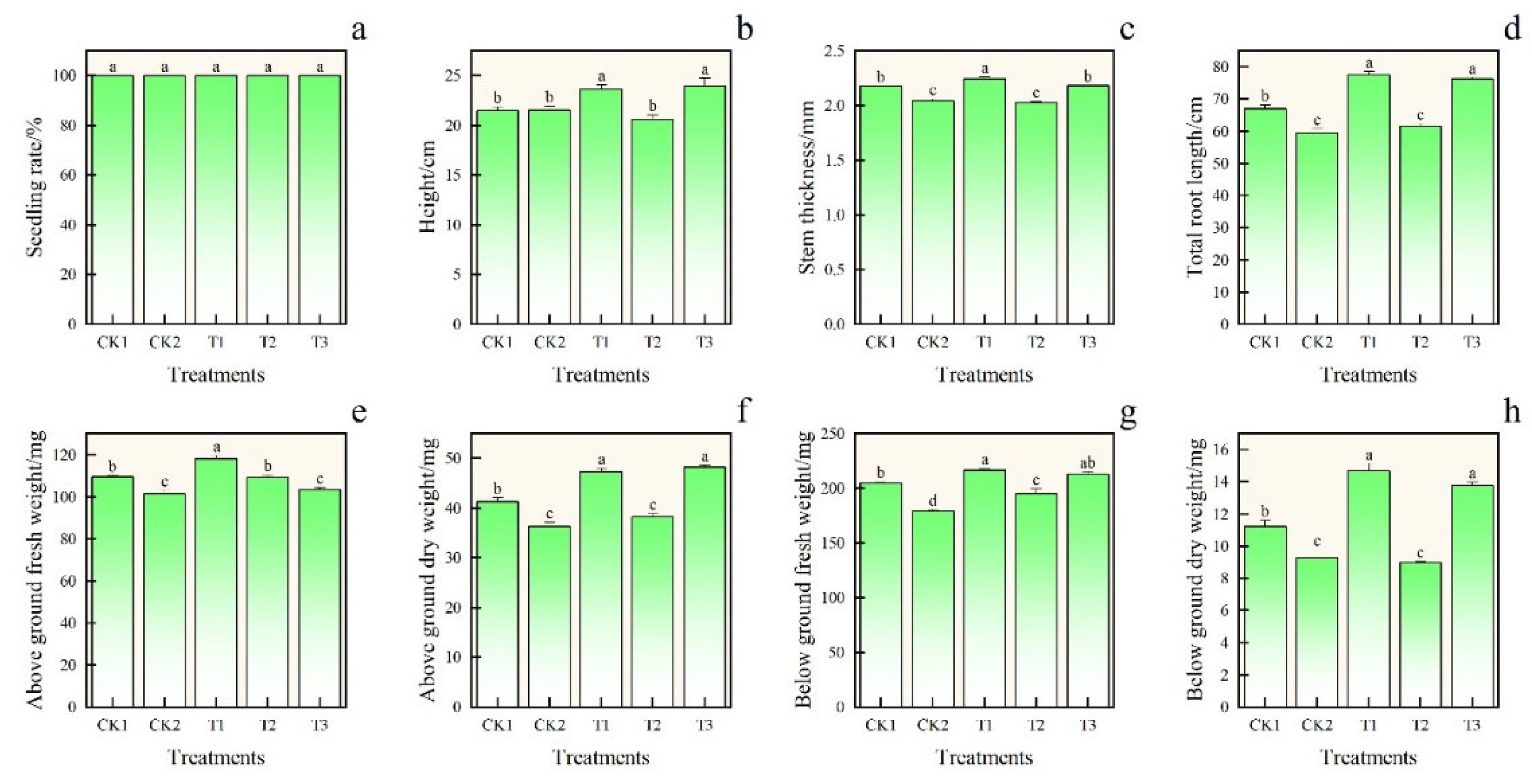

3.5. Rice Seedling Growth

From the growth of rice seedlings (

Figure 2), it can be observed that, similar to the emergence rate of cucumber seedlings (

Figure 2a), the different substrate treatments had no significant effect on the emergence rate of rice seedlings, with all treatment groups achieving 100% emergence rate. Treatments T1 and T3 exhibited the highest levels in rice seedling height (

Figure 2b), total root length (

Figure 2c), aboveground dry weight (

Figure 2d), and belowground dry weight (

Figure 2e), reaching statistically similar levels between the two, while CK2 treatment significantly lagged behind CK1 treatment in all the aforementioned parameters except for plant height. T1 and T3 treatments showed respective increases of 10.00%, 15.79%, 14.49%, and 30.42% compared to CK1 treatment in the above-mentioned parameters. Treatment T2, besides significantly surpassing CK2 treatment in aboveground and belowground fresh weights, showed no significant differences from CK2 treatment in the remaining parameters.

3.6. Seedling Strength Index

Table 5 presents the results of seedling vigor index for cucumber and rice. In terms of cucumber seedling vigor index, the highest value was observed in the T1 treatment, reaching 1.01, representing a significant increase of 36.49% compared to CK1 (0.74) and 86.32% compared to CK2 (0.53). For rice seedling vigor index, both T1 and T3 treatments exhibited significant increases compared to CK1 and CK2. Specifically, the T1 treatment showed the highest rice seedling vigor index at 23.84, indicating a substantial improvement of 33.75% over CK1 (17.81) and 57.89% over CK2 (15.15). While the T1 treatment simultaneously achieved the maximum seedling vigor index for cucumber under cucumber seedling substrate and rice under rice seedling substrate, the T3 treatment attained the maximum value for rice seedling vigor index but did not significantly enhance the seedling vigor index of cucumber compared to CK1.

3.7. Research and Evaluation of Substrate Effectiveness

Table 6 illustrates the substrate tactile perception, wherein CK1 and T1 treatments exhibited higher average scores of 4.6, indicating their substrates possessed a moderate texture, facilitating ease of handling and blending. Conversely, T2 and T3 treatments scored lower with average scores of 3.8 and 4.4, respectively. This disparity might be attributed to the inclusion of composted rice hulls and agricultural humic acid, impacting the texture and blending efficiency of the substrates. Regarding the external appearance of cucumber plants and root development, T1 treatment attained the highest average scores of 4.6 and 4.8, signifying robust growth of cucumber plants, vibrant leaf coloration, and well-developed roots. Following closely was the CK1 treatment with average scores of 4.2 and 4.4. T2 and T3 treatments exhibited lower average scores in this regard, with scores of 0.7 and 0.7, 2.3 and 2.4, respectively, indicating a certain restriction in cucumber plant growth. In terms of rice external appearance and root development, T1 treatment secured the highest average scores of 4.6 and 4.6, followed by CK1 treatment with average scores of 4.2 and 4.2. Conversely, T2 and T3 treatments demonstrated lower average scores of 0.7 and 0.7, 3.6 and 3.6, respectively, in this aspect. Regarding the willingness to use, both CK1 and T1 treatments received perfect average scores of 5.00, indicating a strong inclination among agricultural technicians to utilize these substrates for cucumber or rice seedling cultivation. Notably, T3 treatment garnered the highest average score of 5.00 for rice seedling substrate, yet obtained a lower average score of 0.50 for cucumber seedling substrate.

4. Discussion

Utilizing substrates for cultivating crop seedlings is an effective approach to enhancing crop vigor and yield. The practical application value of substrates has also propelled the development of related industries. The 2023 Central Document further emphasizes the need to accelerate the development of intensive vegetable seedling sunstrate. Traditional crop substrates mainly rely on peat, but with the continuous advancement of industry technology, numerous organic waste materials have directly or indirectly participated in substrate preparation, with coconut coir being a typical representative[

21]. The suitability of coconut coir for substrate preparation primarily lies in its excellent physical properties, which align well with the germination and seedling growth stages of crops. However, coconut coir contains a large amount of salt, requiring leaching to remove the salt content before substrate preparation. During the leaching process, although the physical properties of coconut coir remain intact, the included readily available nutrients are essentially lost along with the salt content. This results in poor growth conditions for crop seedlings when the proportion of coconut coir in the substrate is too high, as notably observed in CK2 treatment in cucumber seedling cultivation in this study. Therefore, it is essential to supplement external nutrients to coconut coir-based substrates, while maintaining the suitability of the substrate for seed germination and seedling growth.

Regarding the technical indicators for vegetable seedling substrates and rice seedling substrates, the agricultural industry standards NY/T 2118-2012 and NY/T 3838-2021 provide clear requirements. This study utilized pig manure organic fertilizer, decomposed rice husks, and agricultural humic acid as nutrient supplements for coconut coir substrates. Through comparison with the two agricultural industry standards, the substrate supplemented with pig manure organic fertilizer was closest to the specified indicators in the standards. While its physicochemical properties as a rice seedling substrate fully complied with the relevant requirements, as a cucumber seedling substrate, it only exceeded the highest limit of effective phosphorus content in NY/T 2118-2012. Therefore, utilizing pig manure organic fertilizer as a nutrient supplement for coconut coir substrates demonstrates considerable feasibility in terms of physicochemical property indicators.

Furthermore, this study referenced the determination method of germination index in organic fertilizer agricultural industry standard NY/T 525-2021 to measure the germination index of each treatment substrate. For organic fertilizers, a germination index exceeding 70% (compared to water) can be technically considered non-toxic to crop seeds[

22,

23]. However, for substrates, their purpose is to promote seed germination and seedling growth; thus, only when the germination index exceeds 100% can it be demonstrated that the substrate may have a certain growth-promoting effect. The results of this study showed that the germination index of all treatments exceeded 100%, with the substrate supplemented with pig manure organic fertilizer having the lowest germination index at 118.87%. This is mainly due to the relatively low germination index of pig manure organic fertilizer, which was previously validated in our research at 72.35%. Although it meets the germination index standard for organic fertilizers, there is still a significant gap for the substrate's requirement of a germination index exceeding 100%. For most organic waste composts, their own germination index is one of the reasons limiting their application proportion in substrates due to their chemical properties[

24].

The germination index reflects the relative suitability of the substrate for crops; however, its assessment only requires 48 hours. The overall suitability of substrates for crop growth still needs to be judged through subsequent seedling growth conditions. In this study, the same treatment substrates were applied to cucumber seedling cultivation and rice seedling cultivation. This was mainly done considering the situations that arise in actual agricultural production, where substrates intended for vegetable seedlings might be used by agricultural practitioners for rice seedling cultivation. To avoid potential economic losses due to improper use, this study evaluated and compared the performance of the same substrate in the seedling growth stages of cucumber and rice. The results showed that the substrate prepared with pig manure organic fertilizer could meet the growth requirements of both crops, and its suitability for rice also aligned with the author's previous relevant research. The substrate prepared with agricultural humic acid could satisfy the growth requirements of rice seedlings but was not suitable for cucumber seedling cultivation. The probable reason lies in the high content of readily available nutrients in agricultural humic acid, which imposed certain stress on cucumber seedling growth. However, due to the unique characteristics of rice seedling trays, the large amount of nutrients in agricultural humic acid may be leached out of the substrate during irrigation, thus avoiding stress on rice seedlings.

In addition to the determination of seedling growth indicators by the experimenters, this study also invited technical personnel engaged in practical agricultural production to evaluate the seedling effects of the substrates. As frontline personnel in contact with and using substrates, the assessment of substrate seedling effects by agricultural technicians is crucial. The results showed that the assessment of substrate seedling effects by agricultural technicians was more consistent with the determinations by the experimenters. Both groups considered the substrate prepared with 10% volume of pig manure organic fertilizer to be the most suitable for seedling cultivation of cucumber and rice. This provides crucial reference opinions for subsequent substrate-related research.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the ameliorative effects of three common nutrient sources in agricultural production processes on seedling cultivation in coconut coir-based substrates. The results demonstrate that a substrate formula consisting of "10% pig manure + 30% peat + 50% coconut coir + 10% vermiculite" can simultaneously meet the growth requirements of cucumber and rice seedlings. It is recommended to further reduce the dosage of pig manure organic fertilizer based on this study, ensuring optimal crop growth while aligning its physicochemical properties and economics more closely with the practical needs of agricultural production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L.; methodology, X.L; software, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Project “Research and Application of Fertilizer and Pesticide Reduction and Efficiency Technology Promotion Service Model in Northern Rice Areas” (2018YFD0200200).

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zaller, J.G. Vermicompost in seedling potting media can affect germination, biomass allocation, yields and fruit quality of three tomato varieties. European Journal of Soil Biology 2007, 43, S332–S336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, S.K.; Mahal, S.S.; Brar, A.S.; Vashist, K.K.; Sharma, N.; Buttar, G.S. Transplanting time and seedling age affect water productivity, rice yield and quality in north-west India. Agricultural Water Management 2012, 115, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.-y.; Yan, J.; Li, M.; Yan, Z.-x.; Wei, H.-y.; Xu, D.-j.; Cheng, X. Preparation of polysaccharide-conjugated selenium nanoparticles from spent mushroom substrates and their growth-promoting effect on rice seedlings. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 126789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X.; Gu, Z.; Cao, H.; Yuan, Q. Effects of different fermentation synergistic chemical treatments on the performance of wheat straw as a nursery substrate. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 334, 117486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Wang, Q.; Lv, Z.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, M.; Li, J.; Ma, X.; Cui, Z.; Ren, L. Novel seedling substrate made by different types of biogas residues: Feasibility, carbon emission reduction and economic benefit potential. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 184, 115028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultberg, M.; Oskarsson, C.; Bergstrand, K.-J.; Asp, H. Benefits and drawbacks of combined plant and mushroom production in substrate based on biogas digestate and peat. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 28, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.-H.; Duan, Z.-Q.; Li, Z.-G. Use of Spent Mushroom Substrate as Growing Media for Tomato and Cucumber Seedlings. Pedosphere 2012, 22, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Shang, W.; Zhang, T.; Chang, X.; Wu, Z.; He, Y. Effect of microbial inoculum on composting efficiency in the composting process of spent mushroom substrate and chicken manure. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 353, 120145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Li, J.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Gao, Y. Effects of different fermentation assisted enzyme treatments on the composition, microstructure and physicochemical properties of wheat straw used as a substitute for peat in nursery substrates. Bioresource Technology 2021, 341, 125815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A'Saf, T.S.; Al-Ajlouni, M.G.; Ayad, J.Y.; Othman, Y.A.; St. Hilaire, R. Performance of six different soilless green roof substrates for the Mediterranean region. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 730, 139182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillero, L.; Solera, R.; Perez, M. Agronomic and phytotoxicity test with biosolids from anaerobic CO-DIGESTION with temperature and micro-organism phase separation, based on sewage sludge, vinasse and poultry manure. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 354, 120146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, L.C.; Campos, C.M.; Cona, M.I.; Giordano, C.V. The quality of endozoochorous depositions: Effect of dung on seed germination and seedling growth of Neltuma flexuosa (DC.) C.E. Hughes & G.P. Lewis. Journal of Arid Environments 2024, 220, 105114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J.S.; Rubio, F.; Martínez, V.; García-Sánchez, F. Amelioration of salt stress by irrigation management in pepper plants grown in coconut coir dust. Agricultural Water Management 2010, 97, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lonardo, S.; Cacini, S.; Becucci, L.; Lenzi, A.; Orsenigo, S.; Zubani, L.; Rossi, G.; Zaccheo, P.; Massa, D. Testing new peat-free substrate mixtures for the cultivation of perennial herbaceous species: A case study on Leucanthemum vulgare Lam. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 289, 110472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Kenari, M.A.; Okhawilai, M. Chapter 6 - Matrix materials for coir fibers: Mechanical and morphological properties. In Coir Fiber and its Composites; Jawaid, M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2022; pp. 107–133. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, L.P.; Barois, I. Development of the earthworm Pontoscolex corethrurus in soils amended with a peat-based plant growing medium. Applied Soil Ecology 2016, 104, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, W.; Yang, Y.; Ma, R.; Li, D.; Shen, Y.; Li, G.; Yuan, J. Phytotoxicity of farm livestock manures in facultative heap composting using the seed germination index as indicator. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2022, 247, 114251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Ge, L.; Li, S.; Pan, R.; Liu, X. Study on the Effect of Kitchen Waste Compost Substrate on the Cultivation of Brassica chinensis L. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 4139–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Jia, K.; Yan, L.; Dong, X.; Pan, R. Suitability Analysis of Kitchen Waste Compost for Rice Seedling Substrate Preparation. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 3115–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.-Y.; Zhang, C.-X. Data Processing System (DPS) software with experimental design, statistical analysis and data mining developed for use in entomological research. Insect Science 2013, 20, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Qin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, J.; Guo, G.; Khan, M.A.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Chang, K.; et al. Assessing the suitability of municipal sewage sludge and coconut bran as breeding medium for Oryza sativa L. seedlings and developing a standardized substrate. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 344, 118644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Guo, Q.; Jia, J. Comparing the effects of three in situ methods on nitrogen loss control, temperature dynamics and maturity during composting of agricultural wastes with a stage of temperatures over 70 °C. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 230, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, G.; Liu, G.; Dang, R.; Li, G.; Yuan, J. Determining the extraction conditions and phytotoxicity threshold for compost maturity evaluation using the seed germination index method. Waste Management 2023, 171, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.; Guo, Q.; Pandey, P.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Sun, Y. Pretreatment by composting increased the utilization proportion of pig manure biogas digestate and improved the seedling substrate quality. Waste Management 2021, 129, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).