1. Introduction

The rapid development of the global textile industry has heighted the urgency of treating dye wastewater and addressing the environmental pollution [

1].Traditional methods for treating dye wastewater often face challenges such as low efficiency, high cost, and the generation of large amounts of by-products [

2,

3]. In the textile industry, the synthesis or application of dyes typically leads to the generation of high-salinity dye wastewater [

4]. The dye synthesis process yields a large amount of inorganic salt (i.e. ~5.0% NaCl) as a byproduct, diminishing the dye purity and reducing the brightness of the printed image in textile applications [

5,

6,

7]. Discharging a large amount of salt along with dyes is the main issue in textile wastewater [

8,

9,

10]. Therefore, effective treatment of textile wastewater is of great significance to mitigate the release of the highly polluted dye waste water. Various approaches including biotechnology and adsorption have been applied to treat dye wastewater. However, most of these solutions face problems such as toxic nanomaterials leaching problem, limited flexibility, high cost, and complicated operating processes. Therefore, the identification of green materials and simple procedures is crucial to solve this problem.

As a green nanomaterial, 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxide radical (TEMPO)-oxidized cellulose nanofiber (TOCNF) has many advantages, such as high surface-to-volume ratio, excellent mechanical stability, low cost and multi-functional surface groups [

11]. TOCNF has made significant breakthroughs in the fields of adsorption and separation [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Through processing and functional modification of TOCNF, it can be applied to the preparation of nanofiltration (NF) or Reverse Osmosis (RO) membranes for dye wastewater treatment [

16]. Due to its hydrogen-bonded parallel chains, TOCNF is a strong natural nanomaterial with one-dimensional (1D) structure [

17,

18]. it can be combined with other two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials to fabricate NF membranes[

19,

20]. Yang

et al. [

19] reported a mixed-dimensional NF membrane fabricated by assembling TOCNFs and covalent organic framework (COF) nanosheets. The prepared TOCNF/COF NF membrane exhibited outstanding hydrolytic stability and improved mechanical properties. Mohammed

et al. [

20] developed a NF membrane by incorporating GO nanosheets into CNF matrix via vacuum filtration method followed by cross-linking by glutaraldehyde. The obtained GO/CNF mix-dimensional NF membrane showed a pure solvent flux of 13.9 Lm

−2h

−1bar

−1 for water and over 90% rejections for two dyes.

Additionally, TOCNFs can serve as additives or as substrates for thin composite NF/RO membrane[

21,

22,

23]. Wang

et al. [

23] prepared a composite RO membrane with modified TOCNFs incorporated in polyamide barrier layer an. The inclusion of TOCNF improved both flux and rejection of the composite RO membrane, attributed to the formation of external water channels caused by TOCNFs. In our previous work, TOCNFs were used as additives incorporated into the polyamide selective layer of RO membrane to enhance the water flux and hydrophilicity of the membrane[

22]. However, few research work has focused on using pure TOCNF to fabricate a dense separating layer of NF/RO membrane.

Herein, we develop an environmentally-friendly NF membrane with a hierarchical nanostructured TOCNF separating layer via simple vacuum filtration method. Different diameter of TOCNFs were vacuum filtrated on Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) substrate membrane to form a dense NF membrane with narrow pore size, which can reject dyes. Specifically, Thick-TOCNFs (without probe ultrasonication) were vacuum filtrated on the substrate membrane, followed by the addition of Fine-TOCNFs (with probe ultrasonication) to form a compact barrier layer of NF membrane. The Fine-TOCNFs serves to reduce pore size of the composite membrane, consequently enhancing dye rejection rate. Furthermore, TMC were used as a crosslinking agent to enhance the stability of the TOCNF layer. The morphology and physicochemical properties of the fabricated TOCNF NF membrane with different Fine-TOCNF concentration were characterized, and their dye/salt separation performance were also evaluated compared with the neat Thick-TOCNF membrane. For better comparison, Fine-TOCNF membranes cross-linked with different concentration of TMC were also synthesized. To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first study to use pure TOCNFs in fabricating the separating layer of NF membrane.

2. Result and Discussion

2.1. Morphology of TOCNFs and TCM Membranes

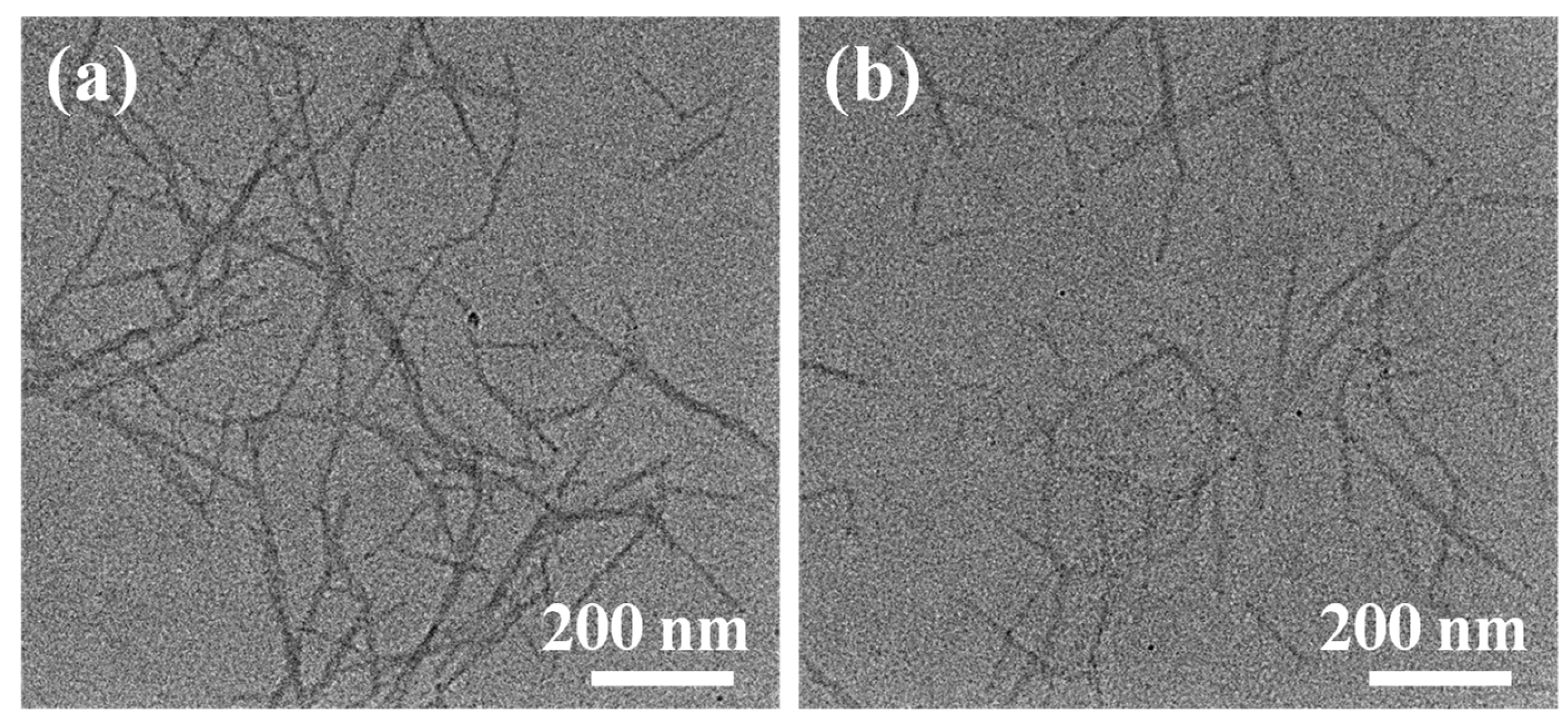

The morphologies of the Fine-TOCNFs and Thick-TOCNFs were observed by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

(Figure 1). The length and diameter distributions of Fine-TOCNFs and Thick-TOCNFs are shown in

Figure 1. The result shows that the Thick-TOCNFs exhibit a long rod structure, while the Fine-TOCNFs shows a shorter and finer rod structure. The length of Thick-TOCNFs is in range of 300-1100 nm and the average length is about 802 nm. After the probe ultrasonic treatment, the Fine-TOCNFs become shorter and thinner, the average length of Fine-TOCNFs reduce to 476 nm, and average width of Fine-TOCNFs decreases from 20.8 nm to 14.8 nm. In this study, Thick-TOCNFs without probe ultrasound were longer and used to fill the big holes of PVDF substrate membrane (pore size 220 nm). Then, Thin-TOCNFs were filtrated and cross-linked on the prefabricated membrane to form a denser layer, due to their finer diameter.

2.2. Characterization of Membranes

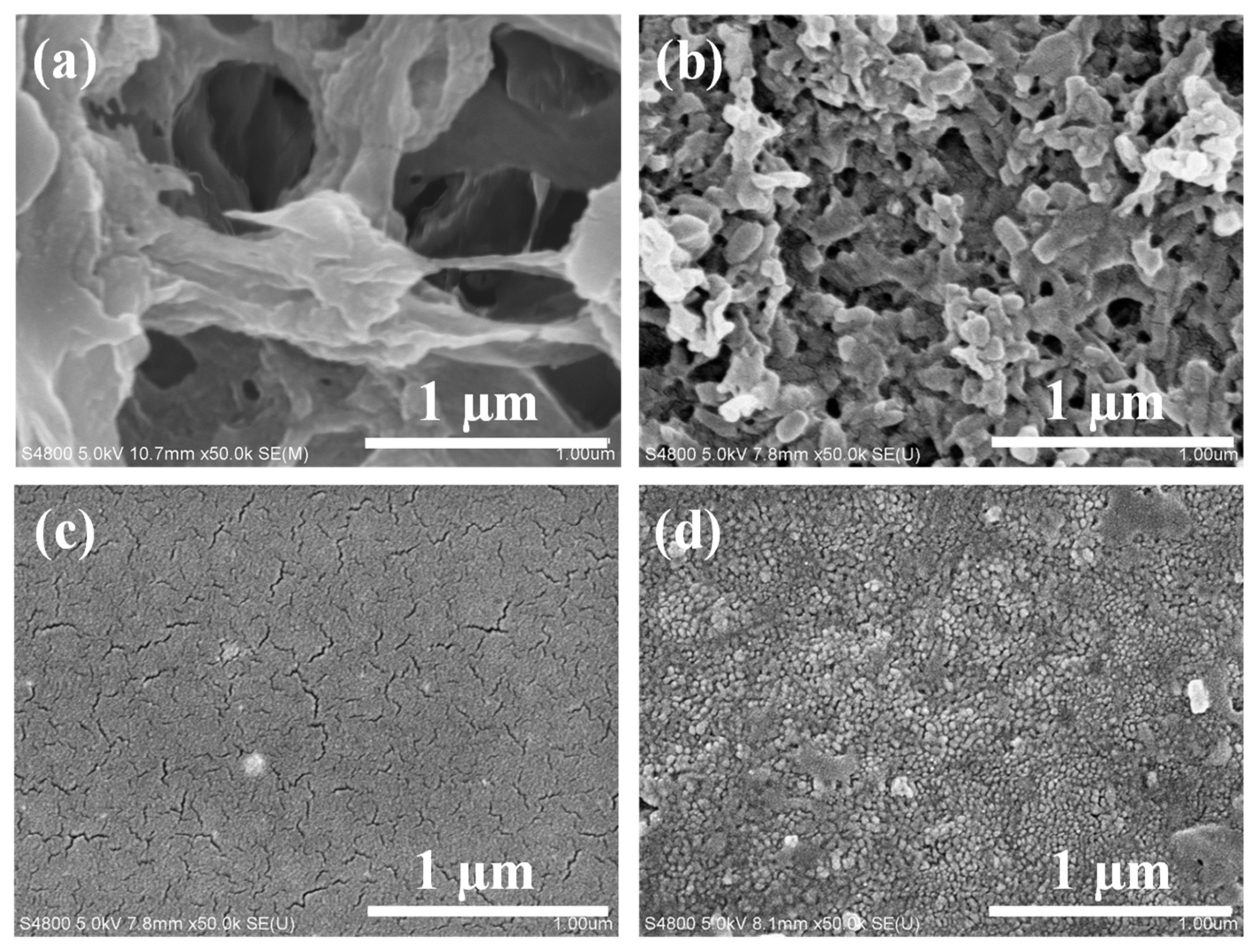

Figure 2 shows the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) surface morphology images of PVDF substrate membrane, and TCM-0 membrane (5 ml Thick-TOCNFs + 0 ml Fine-TOCNFs), TCM-5 membrane (5 ml Thick-TOCNFs + 5 ml Fine-TOCNFs) and TCM-10 membrane (5 ml Thick-TOCNFs + 10 ml Fine-TOCNFs). The average pore size of PVDF membrane is ~220 um,while some huge pores (500~600 um) are observed in

Figure 2a., while the pore size of TCM-0 membrane (

Figure 2b) become much smaller (average pore size is ~ 30 nm). TCM-0 membrane was prepared by vacuum filtrated 5 ml on PVDF membrane, the Thick-TOCNFs are uniformly distributed on the surface of the PVDF membrane, with obviously reduced surface pore size. But this pore size is still not enough to reject dye molecules. After filtrated additional Fine-TOCNFs, and followed by TMC cross-linking, TCM-5 and TCM-10 membrane were obtained. Both of TCM-5 and TCM-10 membrane exhibit uniform and compact surface structure, which can provide a possibility to reject dyes.

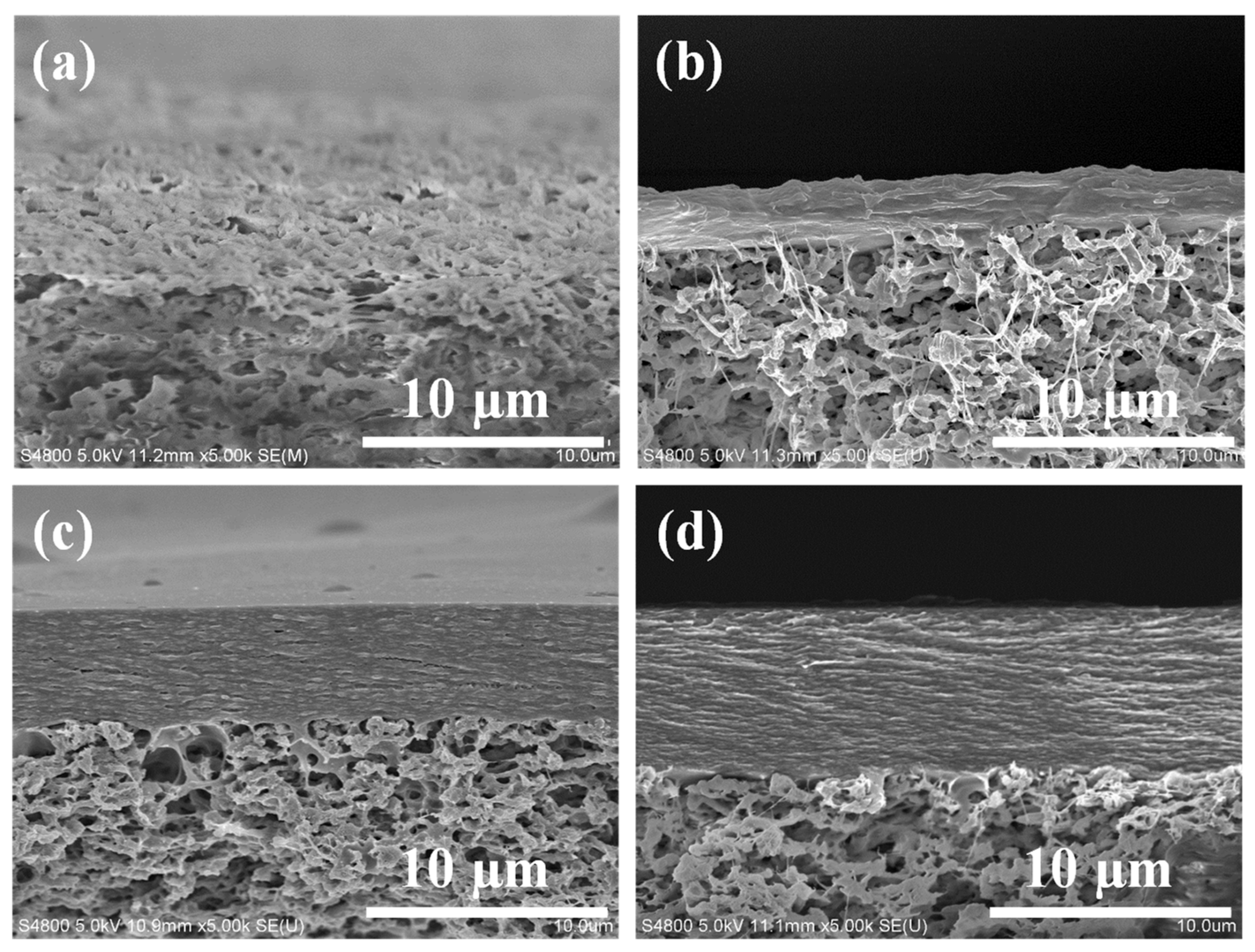

Figure 3 shows the cross-sectional SEM image of TCM membranes. As the content of Fine-TOCNFs increases, the fthickness of the top layer of composite membrane also increases. Moreover, the image reveals that the top layers of TCM-5 and TCM-10 membrane are more compact, presenting a tight layered stacking structure. This is mainly due to the Fine-TOCNFs filling the pores of Thick-TOCNFs layer, thus creating a denser separation layer.

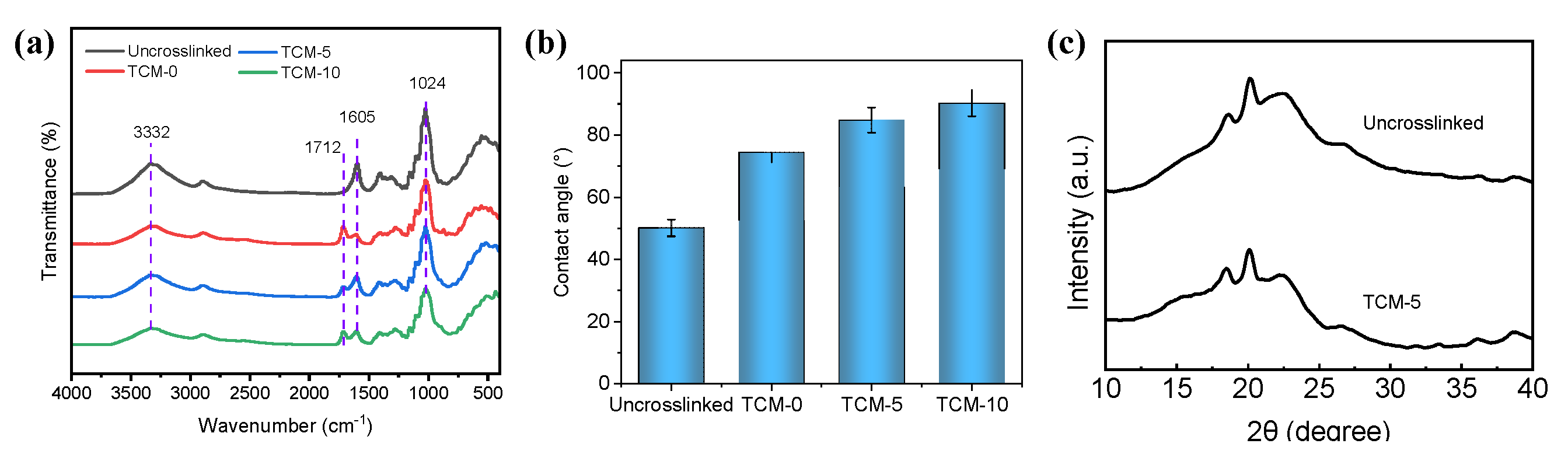

Figure 4a shows the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of membrane samples including control (TOCNFs content equivalent to TCM-5 but without TMC crosslinking process), TCM-0 membrane, TCM-5 membrane, and TCM-10 membrane sample. The characteristic peaks of TOCNFs are typically observed near 3322 cm

−1 and 1024 cm

−1, corresponding to the hydroxyl and cyclic alcohol groups in CNFs, respectively [

22]. Additionally, the peak at 1605 cm

−1 is the C=C ring stretching vibration. Compared to the Uncrosslinked membrane sample, all of TOCNF membranes cross-linked with TMC (TCM-0, TCM-5, and TCM-10 membrane) exhibit an additional peak at 1712 cm

-1 , indicating the presence of the ester bond generated via acylation reaction between the acyl chloride groups of TMC and -OH groups of TOCNF [

24]. This peak confirms the successful crosslinking between TMC and TOCNFs on the membrane surface. Furthermore, in comparison to the Uncrosslinked membrane without TMC crosslinking, the crosslinked membranes (TCM-0, TCM-5, and TCM-10 membrane) show lower transmittance peaks near 3322 cm

−1 and 1023 cm

−1, with the intensity of these two peaks decreasing as the concentration of Fine-TOCNFs increases. This result suggests that the increase in -OH group concentration due to TOCNFs may the increase in membrane hydrophilicity, while crosslinking agent TMC could weaken the membrane hydrophilicity.

Figure 4b shows the water contact angle of Uncrosslinked, TCM-0, TCM-5, and TCM-10 membrane sample. It can be seen that with the Fine-TOCNF content increases, the hydrophilicity gradually weakens, which may be related to the increased hydrophobicity of TOCNF after TMC cross-linking. With the increase of TOCNF content, the cross-linked TOCNFs also increase, causing a slight increase in the contact angle, consistent with the infrared spectroscopy results.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of TOCNF membrane before and after TMC crosslinking are shown in

Figure 4c. The result shows similar peaks at 2θ= 18° and 20°for both the TOCNF membrane with and without TMC crosslinking. However, the TOCNF membrane after TMC crosslinking shows a weaker peak at 2θ= 22.5°, corresponding to the (002) crystal plane of cellulose I [

25]. This small difference may exhibit that TMC crosslinking weaken the crystalline structure of TOCNF membrane.

2.3. The Performance of TCM Membranes

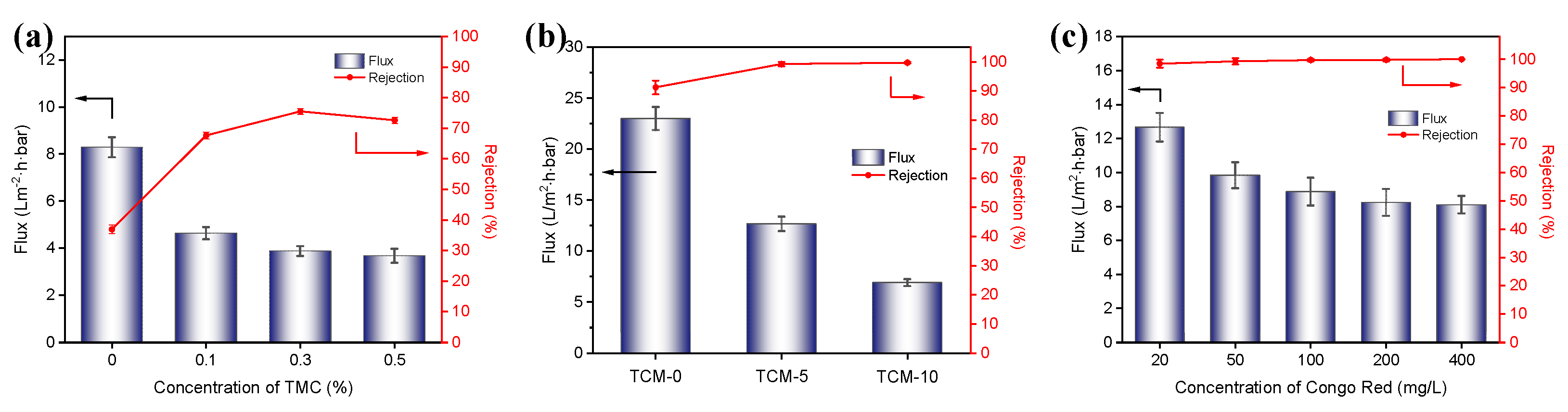

The effect of crosslinking agent (TMC) concentration on the pure water flux and Na

2SO

4 rejection performance of the composite membranes was investigated (

Figure 5a). All of the membrane samples preparation method as TCM-5 membrane sample except for the crosslinking agent (TMC) concentration. Compared with Uncrosslinked membrane, membrane crosslinked with 0.1% TMC, the pure water flux of the nanofiltration membrane decreased from 8.29 L/m

2·h·bar to 4.63 L/m

2·h·bar, and the Na

2SO

4 rejection rate increased from 36.9% to 67.6%, indicating an improvement in the membrane's rejection performance after TMC crosslinking, but a decrease in the water flux. This is mainly due to the consumption of hydrophilic carboxyl groups on the surface of TMC crosslinked membrane, resulting in decreased hydrophilicity and reducing the rate of water molecule transport through the membrane, thereby decreasing the flux. With further increase in TMC concentration, the flux slightly decreased, but the Na

2SO

4 rejection effect first increased and then decreased. This is mainly because the increase in TMC concentration helps to improve the crosslinking degree of TOCNFs and obtained a denser surface, thus enhances the membrane's rejection performance, but too high crosslinking degree reduces the water flux while the pore size sieving effect cannot further improve the Na

2SO

4 rejection rate. When the TOCNFs were not crosslinked with TMC, the structure formed by the hydrogen bonding between the TOCNFs was relatively loose and not strong. Therefore, when the TMC concentration is 0.3%, the nanofiltration membrane has the optimal rejection performance with a Na

2SO

4 rejection rate of 75.5% and a pure water flux of 3.87 L/m

2·h·bar.

The effect of the Fine-TOCNF content on the separation performance of TCM membranes. As can be seen from the Figure 5b, the flux decreases as the TOCNF content increases. The rejection rate of CR increased rapidly after adding Fine-TOCNFs, and the CR rejection rate of TCM-5 membrane increases from 91.2% to 99.2% compared to TCM-0, and further increases to 99.7% for TCM-10 membrane. This indicates that the dense pore structure produced by probe ultrasound treated TOCNF (Fine-TOCNF) has excellent rejection effect on small molecule dyes. The results show that by increasing the CNF content loaded on the membrane surface, the rejection rate of the membrane can be improved to a certain extent, but the flux decreases to a certain extent. TCM-5 membrane still has a rejection rate of 99.2% for CR while retaining a certain permeability performance (12.67 L/m2·h·bar).

The impact of different concentrations of CR on the performance of nanofiltration membranes was tested by adjusting the dye concentration (

Figure 5c)

. The water flux of the TCM-5 membrane slightly decreased with the increase of dye concentration, from 12.66 L/m

2·h·bar to around 8.09 L/m

2·h·bar. This is because as the dye concentration increases, the dye molecules are more likely to attach to the pores and permeation channels on the membrane surface, forming a dense layer of dye molecules, which increases the transmembrane resistance of water molecules and leads to a decrease in water flux. In addition, as the dye concentration increases, the membrane's rejection rate of dye also slightly increases, from 98.4% to 99.9%. This is mainly due to the formation of a “filter cake” layer on the membrane surface, which creates a spatial resistance effect that blocks the passage of dye molecules, resulting in a decrease in water flux but an increase in the membrane's rejection rate of dye.

2.4. Separation Performance of TCM Membrane for Different Salts and Dyes

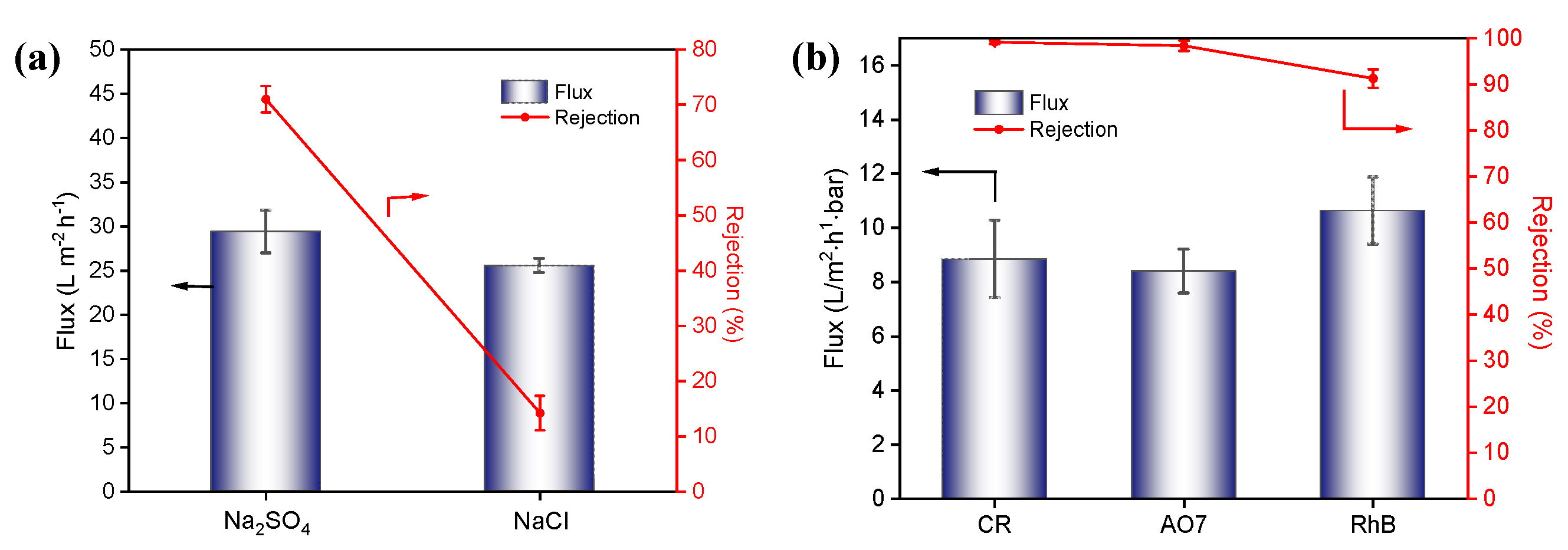

The salt separation performance of the TCM-5 membrane was evaluated from the rejection of Na

2SO

4 and NaCl salt solutions at a pressure of 0.4 MPa, and the results of the permeation flux and rejection ratios are shown in

Figure 6a. The TCM-5 membrane shows good rejection performance for divalent salt with rejection of 71.0% for Na

2SO

4 and poor rejection for monovalent salt with rejection of 14.2% for NaCl. The result is consistent with literature reports on negatively charged nanofiltration membrane performance[

26]. According to the Donnan effect theory, the negatively charged nanofiltration membrane has a stronger repulsion force for divalent anions (SO

42-) than monovalent anions (Cl

-), resulting in a higher rejection rate of Na

2SO

4 by the membrane. This result shows that TCM-5 membrane has good NaCl/Na

2SO

4 selectivity. Similarly, the low rejection rate of Rhodamine B (RhB) dyes with positive charges on the negatively charged membrane surface indicates that the separation mechanism of the composite membrane is a combination of pore size screening and electrostatic effects.

The dye removal performance of the TCM-5 membrane was evaluated by filtration of three types of dye solutions (Congo Red (CR), Orange Yellow (AO7) and RhB), and the results are shown in

Figure 6b. As seen, the rejection efficiency reached over 99% when processing CR and AO7, while the rejection rate of RhB was 91%. Generally, the removal rate of the membrane for these three dyes is determined by their molecular weight, and the larger the molecular weight, the more significant the removal effect. The experimental result shows that the rejection rate of CR (Mw=670 g/mol) is greater than that of AO7 (Mw=350 g/mol). However, for RhB (Mw=479 g/mol), the rejection is lower than that of AO7 with a larger molecular weight. This is mainly because the nanofiltration membrane surface is negatively charged, resulting in greater electrostatic repulsion of AO7 dye than RhB, and the combined effect of pore size and electrostatic effects leads to a lower rejection rate of RhB dye. The experimental results show that the prepared TCM-5 membrane also has good rejection effect for dyes.

3. Experimental

3.1. Materials

1,3,5-benzenetriacyl chloride (TMC), 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxide radical (TEMPO), sodium hypochlorite (NaClO), sodium bromide (NaBr), Congo red (CR), rhodamine B (RhB), orange yellow (AO7), Na2SO4, MgSO4, NaCl, MgCl2 were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Co. Ltd. Polyvinylidene fluoride membranes were purchased from Nantong Longjin Film Technology Co., Ltd.

3.2. Preparation of TOCNF

1 g pulp was used as raw material, shredded and dissolved in 100 ml of deionized water, and added with 100 mg of NaBr, 16 mg of TEMPO and 11.16 g of NaClO (concentration of 12.5%). The pH of the mixed solution was adjusted to 10 and reacted for 8 hours. Then, centrifugation was performed three times at 9000 rpm to obtain a gel-like solid. 500 ml of deionized water was added to dissolve the solid, and stirred in a homogenizer for 3 minutes to obtain a transparent aqueous solution. The obtained solution was named as Thick-TOCNFs. Finally, the obtained Thick-TOCNFs solution was further broken by an ultrasonic probe to obtain Fine-TOCNF, the dimeter of Fine-TOCNFs is smaller than the Thick-TOCNFs.

3.3. Preparation of TCM

Vacuum-assistant method was adopted to prepare the TOCNF membranes. Specific steps were as follows: Firstly, 5 ml Thick-TOCNF solution was filtrated onto a PVDF membrane (pore size 200 nm). Then additional 0, 5, or 10 ml Fine-TOCNF solution were filtered on the membrane, respectively. After the TOCNF solutions vacuumed, 5ml TMC solution (0.3% in n-hexane) were poured on the membrane to crosslink the TOCNFs. Finally, the obtained TOCNF membranes were kept in an oven at 80℃ for 30 minutes for better crosslink. Based on the different Fine-TOCNF dosage, the obtained membranes are named TCM-0, TCM-5, and TCM-10, respectively. As a comparison, Uncrosslinked membrane was prepared in the same condition with TCM-5 without TMC cross-linking step.

3.4. Characterization of Membranes

The morphology of Thick-TOCNFs and Fine-TOCNFs were observed by TEM (FEI Tecnai F20, USA). Diluted Thick-TOCNFs and Fine-TOCNFs drops were dropped on copper grids respectively. The surface and cross-section morphology of the PVDF membrane, TCM-0, TCM-5 and TCM-10 membrane were observed by SEM. All the samples were coated with gold prior and the cross-section membrane samples were fractured in liquid nitrogen. The chemical composition of Uncrosslinked membrane, TCM-0, TCM-5 and TCM-10 membrane were obtained through FTIR (Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS 10, USA) in the wavelength range of 400-4000 cm−1. The hydrophilicity of PVDF membrane, TCM-0, TCM-5 and TCM-10 membrane was measured at room temperature using a contact angle measuring instrument (OSA 60, Germany). The contact angles of water drops were measured in quintuplicate to get the average contact angle. XRD pattens of Uncrosslinked membrane and TCM-5 membrane were measured by a XRD (Rigaku Miniflex 600, Japan). XRD patterns were determined at 40 kV and 25 mA.

3.5. Permeability Performance of TCM Membrane

The filtration performance of composite membranes was evaluated using a cross-flow filtration system. Membrane flux and rejection rate tests were conducted on an effective membrane surface area of 25.12 cm

2 at 0.4 MPa. Dye or salt solutions were used as feed solution, and the weight of permeate solution was continuously recorded using a precision electronic balance connected to a computer. All results given are averages with standard deviations for at least three samples of each type of membrane. Pure water flow rate was calculated using equation (1). Salt rejection rate was calculated using equation (2).

where

F is the permeate flux (L/m

2h),

V is the permeate volume (L),

A is the membrane area (m

2), and Δ

t is the filtration time (h).

where

R is the rejection, and

Cp and

Cf are the NaCl concentrations (electrical conductivity used in this work) of permeate and feed solution, respectively.

4. Conclusions

In this work, TCM nanofiltration membranes were fabricated by depositing Fine-TOCNF into Thick-TOCNF structure, followed by crosslinking with TMC. The dense selective layer of the TCM nanofiltration membrane consists entirely of pure cellulose nanofibers. The fabrication conditions were optimized, and the results show that 0.3% TMC as cross-linking agent is optimal concentration, and Fine-TOCNF 5 ml filtrated on the Thick-TOCNF membrane is the optimal fabrication condition. The SEM result shows that TCM-5 and TCM-10 membranes have tighter pore structure compared with TCM-0 membrane (without Fine-TOCNF) layer. The hydrophilicity of the TCM membranes decreases as the Fine-TOCNF content increased. The TCM-5 membrane shows a good rejection rate for divalent salt (Na2SO4) with rejection rates of 71.0% while a low rejection of monovalent ion (NaCl) at only 14.2%. Meanwhile, the TCM-5 membrane shows excellent removal performance for various dyes (all over 90%), especially for CR and AO7 (both over 99.0%). These findings highlight the TCM-5 membrane’s exceptional dyes/NaCl selectivity and NaCl/Na2SO4 selectivity. Moreover, TOCNF membranes, derived from sustainable resources, offer their low cost and high separation efficiency, making them promising candidates to be used in the field of dye/salt wastewater treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z. X. and H. T.; methodology, S. L. and M. S. (Mei Sun); validation, S. L. and K. Z.; formal analysis, C. W., M. S. (Meng Shan); Investigation, Y. H., M. W.; data curation, K. W., and J. W.; writing-original draft preparation, S. L.; writing-review and editing, Z.X. and H.T.; visualization, K. Z; funding acquisition, S.L. Y. H. and H.T. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financially supported by Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (2108085ME188), the Anhui Polytechnic University Startup Foundation for Introduced Talents, China (2021YQQ048), the Anhui Polytechnic University Startup Foundation for Introduced Talents, China (2022YQQ083), the Key Program of Anhui Polytechnic University, China (Xjky2022115). The Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (S202210363249).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, H.; Wu, D. Rapid, Massive, and Green Synthesis of Polyoxometalate-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks to Fabricate POMOF/PAN Nanofiber Membranes for Selective Filtration of Cationic Dyes. Molecules 2024, 29, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, Q.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L. Comb-shaped amphiphilic triblock copolymers blend PVDF membranes overcome the permeability-selectivity trade-off for protein separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Rahmatinejad, J.; Raisi, B.; Ye, Z. Triethanolamine-based zwitterionic polyester thin-film composite nanofiltration membranes with excellent fouling-resistance for efficient dye and antibiotic separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 670, 121355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, X.; Tao, R.; Cui, Z.; Matindi, C.; Shi, W.; Chu, R.; Ma, X.; Fang, K.; et al. Selective separation of dye and salt by PES/SPSf tight ultrafiltration membrane: Roles of size sieving and charge effect. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.-L.; Yan, Y.-N.; Zhou, F.-Y.; Sun, S.-P. Tailoring nanofiltration membranes for effective removing dye intermediates in complex dye-wastewater. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Zaidi, S.J. Nanoparticles in reverse osmosis membranes for desalination: A state of the art review. Desalination 2020, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, Z.; Rui, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z. A Review on Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration Membranes for Water Purification. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, L.; Elcik, H.; Blankert, B.; Ghaffour, N.; Vrouwenvelder, J. Textile dye wastewater treatment by direct contact membrane distillation: Membrane performance and detailed fouling analysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nia, M.H.; Tavakolian, M.; Kiasat, A.R.; van de Ven, T.G.M. Hybrid Aerogel Nanocomposite of Dendritic Colloidal Silica and Hairy Nanocellulose: an Effective Dye Adsorbent. Langmuir 2020, 36, 11963–11974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routoula, E.; Patwardhan, S.V. Degradation of Anthraquinone Dyes from Effluents: A Review Focusing on Enzymatic Dye Degradation with Industrial Potential. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 647–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Low, Z.X.; Xie, Z.; Wang, H.J.A.M.T. TEMPO-Oxidized Cellulose Nanofibers: A Renewable Nanomaterial for Environmental and Energy Applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2001180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Lindström, T.; Sharma, P.R.; Chi, K.; Hsiao, B.S.J.C.R. Nanocellulose for sustainable water purification. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 8936–9031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautner, A. Nanocellulose water treatment membranes and filters: a review. Polym. Int. 2020, 69, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Pu, J. Facile fabrication of an effective nanocellulose-based aerogel and removal of methylene blue from aqueous system. J. Water Process. Eng. 2020, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bai, L.; Zhu, X.; Xu, D.; Li, G.; Liang, H.; Wiesner, M.R. The role of carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals placement in the performance of thin-film composite (TFC) membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norfarhana, A.; Ilyas, R.; Ngadi, N.J.C.P. A review of nanocellulose adsorptive membrane as multifunctional wastewater treatment. Carbohyd. Polym. 2022, 119563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzeid, R.E.; Salama, A.; El-Fakharany, E.M.; Guarino, V. Mineralized polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate hydrogels incorporating cellulose nanofibrils for bone and wound healing. Molecules 2022, 27, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yuan, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, L.; Guo, H.; Xu, K.; Zhang, L.; Du, G.J.M. Preparation of nanocellulose-based aerogel and its research progress in wastewater treatment. Molecules 2023, 28, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, Y.; Nasir, N.; Song, Y.; Wu, H.; Pan, F.J.N.c. Covalent organic framework membranes through a mixed-dimensional assembly for molecular separations. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Hegab, H.M.; Ou, R.; Design. Nanofiltration performance of glutaraldehyde crosslinked graphene oxide-cellulose nanofiber membrane. Chem. Eng. Res. 2022, 183, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, H.; Chu, B.; Hsiao, B.S. Thin-film nanofibrous composite reverse osmosis membranes for desalination. Desalination 2017, 420, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Low, Z.-X.; Hegab, H.M.; Xie, Z.; Ou, R.; Yang, G.; Simon, G.P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Enhancement of desalination performance of thin-film nanocomposite membrane by cellulose nanofibers. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, L.; Ma, H.; Venkateswaran, S.; Hsiao, B.S. High-flux nanofibrous composite reverse osmosis membrane containing interfacial water channels for desalination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 26199–26214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroña, G.N.B.; Lim, J.; Choi, M.; Jung, B. Interfacial polymerization of polyamide-aluminosilicate SWNT nanocomposite membranes for reverse osmosis. Desalination 2013, 325, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Cai, Z.; Ma, Z.; Gong, S. Cellulose Nanofibril/Reduced Graphene Oxide/Carbon Nanotube Hybrid Aerogels for Highly Flexible and All-Solid-State Supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 3263–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Liu, Y.; Ding, A.; Ren, N.; Li, G.; Liang, H. Fabrication and characterization of thin-film composite (TFC) nanofiltration membranes incorporated with cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) for enhanced desalination performance and dye removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 358, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).