1. Introduction

The presence of chiral amino acids in living organisms is rooted in the origins of life and the natural selection of molecular synthesis. The early Earth environment likely harbored certain physical or chemical conditions that led to chiral selection, laying the foundation for the formation of life molecules. Within living organisms, the molecular synthesis process exhibits selectivity for specific chiral amino acids, with enzymes and catalysts favoring the efficient synthesis or utilization of L-configured amino acids. Throughout the evolutionary process, organisms gradually developed a preference for specific chiral amino acids, enhancing their chances of survival and reproduction.[

1] This selectivity is associated with affinity for particular configurations, catalytic efficiency, and molecular stability, ultimately influencing normal biological functions and adaptation to the environment. In summary, the existence of chiral amino acids is a result of the interplay between the early Earth environment and biological evolution, providing crucial groundwork for the formation and development of life systems.[

2,

3]

Amino acids are the basic units that constitute the macromolecule proteins in living organisms and are also crucial components in life processes.[

4] In the natural amino acids, apart from glycine, all other amino acids exist in two stereoisomeric forms, L and D. During protein synthesis, living organisms selectively utilize L-configured amino acids, highlighting the biological preference for this stereoisomer. The specific spatial arrangement of L-amino acids is essential for proper protein folding, maintaining the structural integrity critical for biological activity.[

5] Enzymes, hormones, and other biomolecules often exhibit high selectivity for L-configured amino acids, influencing metabolic pathways and biological functions. Additionally, the role of amino acid chirality extends to drug design, where the preferential use of L-configured amino acids enhances the biological compatibility and efficacy of pharmaceuticals.[

6] The role of D-amino acids in living organisms is relatively limited, primarily demonstrated in specific areas such as antimicrobial activity, drug design, research tools, and applications in veterinary medicine and animal feed, showcasing certain biological functions and potential utility.[

7] Overall, the chiral nature of amino acids profoundly impacts the structure, function, and regulation of biological systems, reflecting the evolutionary adaptability and survival advantages associated with specific stereoisomers.

Lysine is a basic amino acid, and most higher animals cannot synthesize lysine.[

8] Therefore, lysine is an essential amino acid that must be ingested in sufficient quantities from the diet to maintain protein synthesis.[

9] L-lysine is considered an essential amino acid of great importance to human health, playing a significant role in enhancing immunity, promoting calcium absorption, and improving central nervous system function.[

10] Abnormal metabolism of L-lysine may lead to certain cancers.[

11] L-lysine has multiple functions, including enhancing immunity, promoting skeletal muscle growth, facilitating fat metabolism, and alleviating anxiety.[

12,

13,

14,

15]Additionally, it can also produce synergistic effects with other nutrients and promote their absorption, improving the utilization efficiency of various nutrients, and thereby better expressing the physiological functions of different nutrients.[

16,

17] A deficiency in D-lysine may lead to adverse health reactions, including uremia. There are differences in the efficiency with which D-lysine and L-lysine are absorbed and utilized by the body, with D-lysine having a lower absorption and utilization rate, while the primary biological activity is provided by L-lysine.[

18] Lysine plays a crucial role in the function of proteins. Due to its widespread and reliable role as a drug target, lysine has received extensive attention.[

19] Therefore, it also plays an important role in distinguishing different enantiomers.

Although there are already some methods for detecting lysines, such as the luminol chemiluminescence method,[

20] gas chromatography-mass spectrometry,[

21] synchrotron X-ray powder diffraction, and thermogravimetric analysis,[

22] these methods come with the disadvantages of expensive equipment and cumbersome detection processes. Therefore, there is a need for a simple and efficient method for detecting lysine. Fluorescence analysis, with its advantages of high sensitivity, strong selectivity, low sample requirement, and simplicity, has attracted great interest from researchers. However, the current synthesis of many fluorescent probes is challenging, and they only exhibit limited enantioselectivity.[

23] Therefore, preparing efficient fluorescent probes for the chiral recognition of lysine via a simple synthetic route remains a significant challenge.

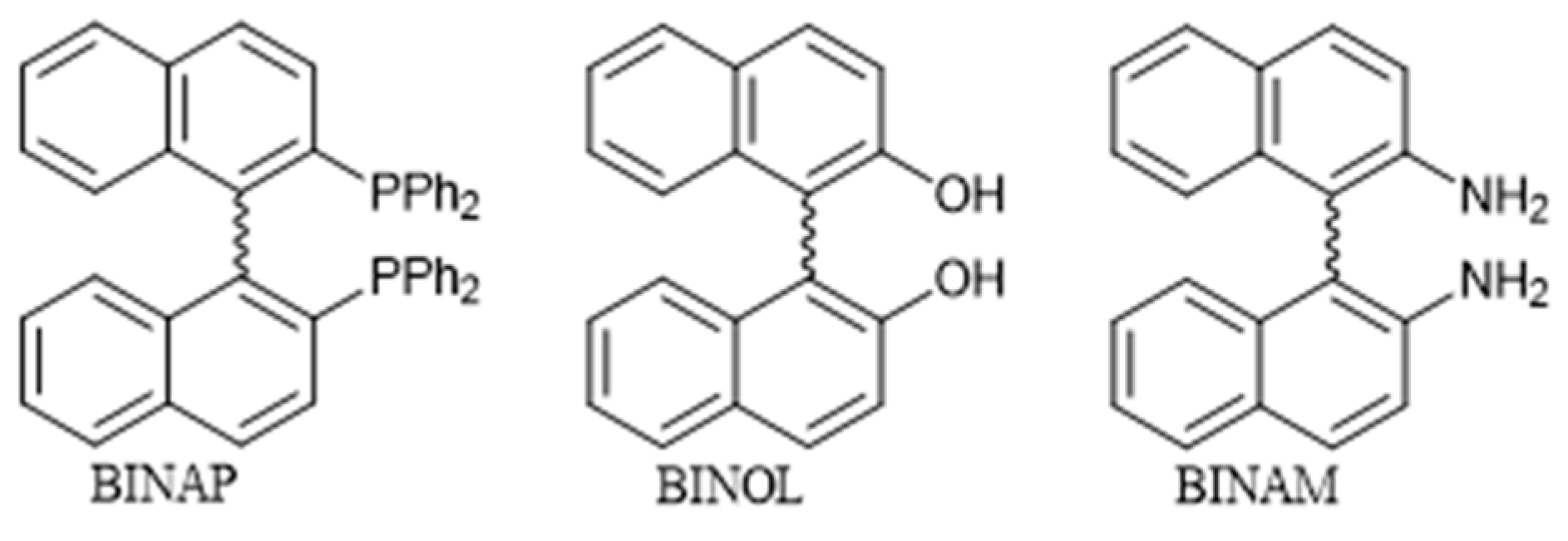

In recent years, axially chiral 1.1'-Binaphthyl-2.2'-diphemyl phosphine(BINAP), 1,1'-binaphthyl-2,2'-diol(BINOL) (

Figure 1), and their derivatives have become one of the most successful chiral ligands/catalysts in asymmetric catalysis and are widely used in various enantioselective catalyzes.[

24] However, 2,2'-Diamino-1,1'-binaphthalene (BINAM), which also possesses axial chirality, has seen very limited application in asymmetric synthesis, with relatively few related publications. BINAM has long been considered by researchers as a potential fluorescent detector for the efficient chiral recognition of α-phenylethylamine and tryptophan enantiomers.[

25] Previous studies have shown that probes based on BINAM can highly selectively recognize lysine in aqueous solutions, but the results indicated a significant fluorescent response for both configurations, thus unable to distinguish the configuration of lysine.[

26] This article has discovered and synthesized a fluorescent probe that can selectively recognize L-lysine with high selectivity in physiological conditions. The results indicate that other amino acids do not affect the recognition effect, and the probe has the advantages of being acid and alkali resistant, sensitive, and capable of recognition over a longer period. We also studied the recognition effect of the probe in the presence of certain metal ions and the substitution sites of the probe. The results are presented below.

2. Experimental

2.1. Reagents and Apparatus

1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra were measured using a Bruker AM600 NMR spectrometer. The chemical shifts of the NMR spectra are given in ppm relative to the internal reference TMS (1H, 0.00ppm) for protons. HRMS spectral data were recorded on a Bruker Micro-TOF-QII mass spectrometer. Fluorescence spectra were obtained at 298 K using a (F97 Pro) spectrofluorophotometer with an excitation wavelength of 365 nm. All chemicals involved in the experiments were purchased from Adamas Chemistry Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The chemicals were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. All solvents used in the optical spectroscopy studies were of HPLC or spectroscopic grade.

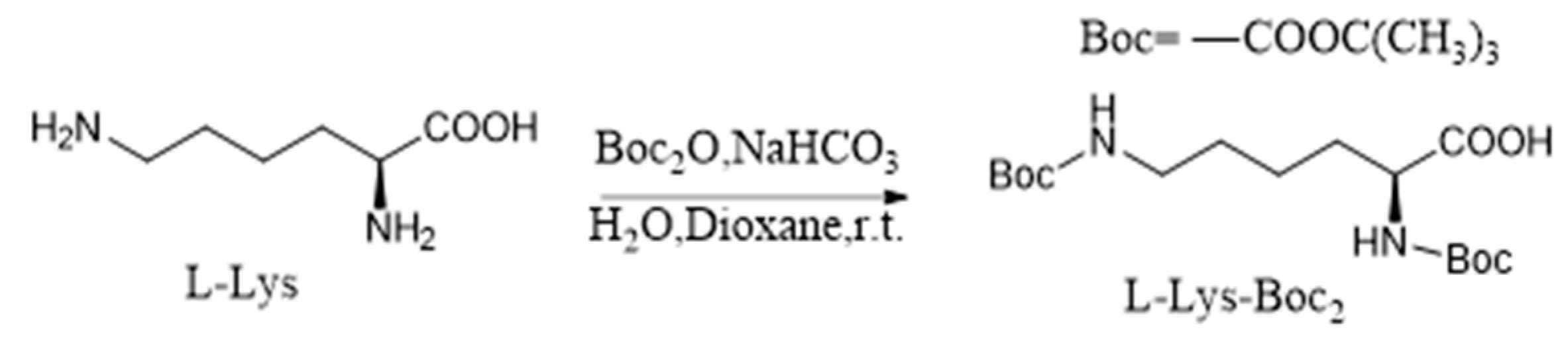

2.2. Synthesis of L-Lys-Boc2

L-Lysine (731 mg, 5 mmol) was added to 100 mL of H

2O containing NaHCO

3 (840 mg, 10 mmol), and, under stirring, Boc

2O (1500 mg, 6.87 mmol) dissolved in 50 mL of dioxane was slowly added, followed by stirring at room temperature for 12 hours. Boc

2O (1500 mg, 6.87 mmol) dissolved in 50 mL of dioxane was then added slowly again under stirring, and the reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). After the reaction proceeded for an additional 12 hours, it was extracted three times with 50 mL of DCM and washed three times with 20 mL of H

2O. The organic solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography, eluting with DCM/MeOH (30:1) to obtain a yellow gel-like L-Lys-Boc

2 with a yield of 84% (1455 mg, 4.2 mmol), as shown in

Scheme 1. Similarly, a colorless gel-like D-Lys-Boc

2 was obtained using the same method, with a yield of 80%.

2.3. Synthesis of (L, R)-1

To a solution of R-BINAM (284 mg, 1 mmol) in DCM (30 mL), triethylamine (200 μL, 1.5 mmol) was added. After cooling the mixture to 0°C, 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzoyl chloride (230 mg, 1 mmol) was slowly added dropwise, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 8 hours. The progress of the reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). After the reaction was complete, the mixture was washed three times with 20 mL of H

2O. The organic solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography, eluting with DCM/PE (1:1) to obtain a pale-yellow powder R-1, with a yield of 65% (310 mg, 0.65 mmol). The same method yielded a pale-yellow powder S-1, with a yield of 59%. Next, R-1 (239 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added to a DCM solution (30 mL) and stirred at 0°C. After cooling the system to 0°C, HOBt (81 mg, 0.6 mmol) and EDCI (93 mg, 0.6 mmol) were added, and the mixture was stirred for 2 minutes before adding L-Lys-Boc

2 (346 mg, 1 mmol). The system was then transferred to room temperature and stirred for 20 hours, with the progress of the reaction monitored by TLC. After the reaction was complete, the mixture was washed three times with 20 mL of H

2O. In the back of removing the organic solvent under reduced pressure, the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography, eluting with DCM/MeOH (50:1), and following removing the organic solvent under reduced pressure, a white powder defined as (L, R)-1 was obtained, with a yield of 34% (137 mg, 0.17 mmol), as shown in

Scheme 2. L/D is the configuration of Lys-Boc2 and R/S is the configuration of BINAM. The same method yielded (L, S)-1 with a yield of 32%, (D, R)-1 with a yield of 38%, and (D, S)-1 with a yield of 28%.

The four fluorescent probes were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, 19F NMR, and MS, with the spectral data provided in the supplemental Information.

2.4. Preparation of Samples for Fluorescence Analysis

Solutions of four sensors were separately prepared at a concentration of 2.0 mM in ethanol, and amino acids were prepared at a concentration of 200 mM in Deionized water as stock solutions, to be used immediately upon preparation. In the study of selectivity towards amino acids, 30 μL of the sensor/EtOH stock solution was mixed with 30 μL of the amino acid/ H2O stock solution, left to stand for 10 minutes, and then diluted with PBS buffer (pH=7.4) to 3000 μL to form the detection solution. In the study of Amino acids selectivity, 30 μL of the L-Lys stock solution was first mixed with 30 μL of the stock solution of another amino acid, left to stand for 10 minutes, followed by the addition of 30 μL of the sensor/EtOH stock solution, and then diluted with PBS buffer to 3000 μL to form the detection solution. For the study recognition in different pH, 30 μL of the sensor/EtOH stock solution was mixed with 30 μL of the Lys/ H2O stock solution, left to stand for 10 minutes, and then diluted with PBS buffer at the corresponding pH to 3000 μL to form the detection solution, adjusting the pH with dilute solutions of NaOH and HCl. In the study of the detection limit of the probes, Lys was re-prepared at a concentration of 20 mM in Deionized water as the stock solution. 30 μL of the sensor/EtOH stock solution was mixed with 3x μL of the Lys/ H2O stock solution, left to stand for 10 minutes, and then diluted with buffer to 3000 μL to form the detection solution, where x corresponds to the concentration ratio of Lys. In the study of the effect of metal ions on probe recognition, 30 μL of the sensor/EtOH stock solution was first mixed with 30 μL of a 4.0 mM solution of metal chloride, left to stand for 10 minutes, followed by the addition of 30 μL of the L-Lys stock solution, and then diluted with PBS buffer at pH 7.4 to 3000 μL to form the detection solution.

In the experiments described, the volume concentration of EtOH in the detection solution is 1%, and the concentration of the sensor is 0.02 mM. Except for the experiments determining the detection limit, the concentration of amino acids is maintained at 2 mM. All fluorescence data, except for those related to stability studies, were obtained within 3 hours. Unless specifically stated, the data were obtained at room temperature with PBS buffer (pH=7.4, EtOH/PBS =1/99, v/v) solution as the solvent. Reaction time :30 min. PMT: 650V. Error bars from three independent experiments. λexc = 365 nm. Slit: 20/10 nm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W. and X.L.; Validation, L.W.; Formal analysis, L.W.; Investigation, L.W.; Resources, G.Z.; Writing—original draft, L.W.; Writing—review and editing, W.C., Y.Z., X.Z. and J.Y.; Visualization, L.W.; Validation, W.C.; Supervision, G.Z.; Project administration, X.L.; Funding acquisition, G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

BINAP, BINOL and BINAM.

Figure 1.

BINAP, BINOL and BINAM.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of L-Lys-Boc2.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of L-Lys-Boc2.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of (L, R)-1.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of (L, R)-1.

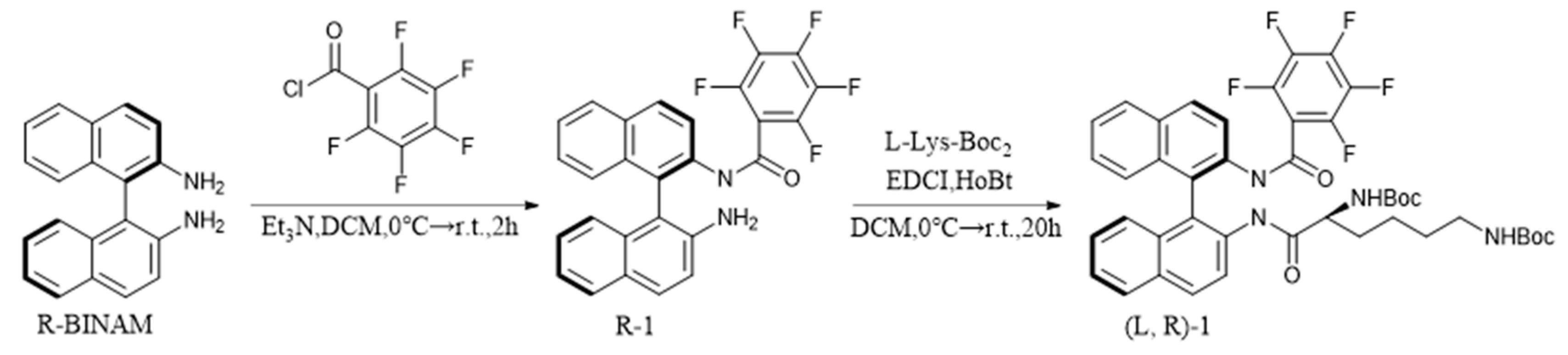

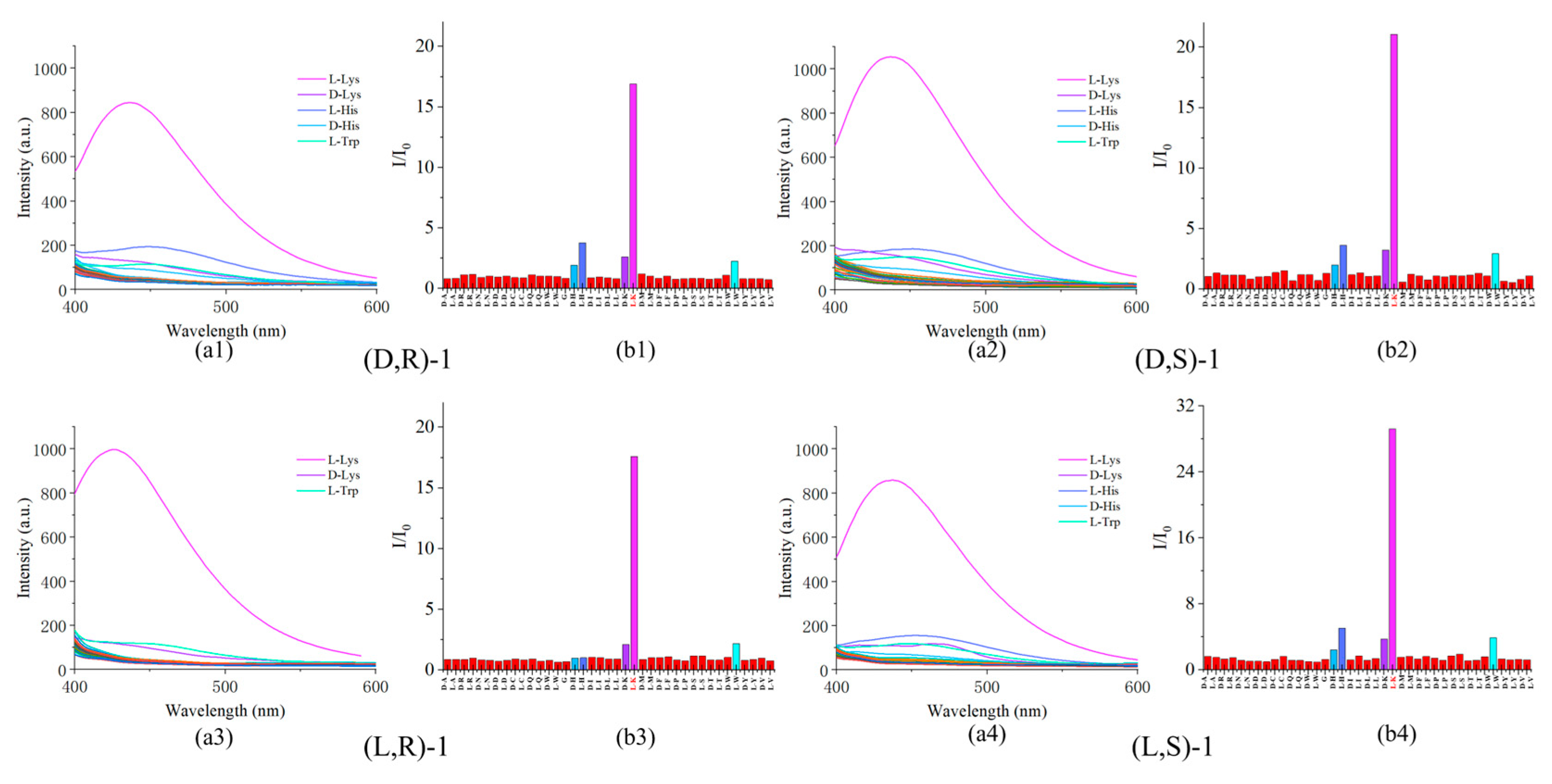

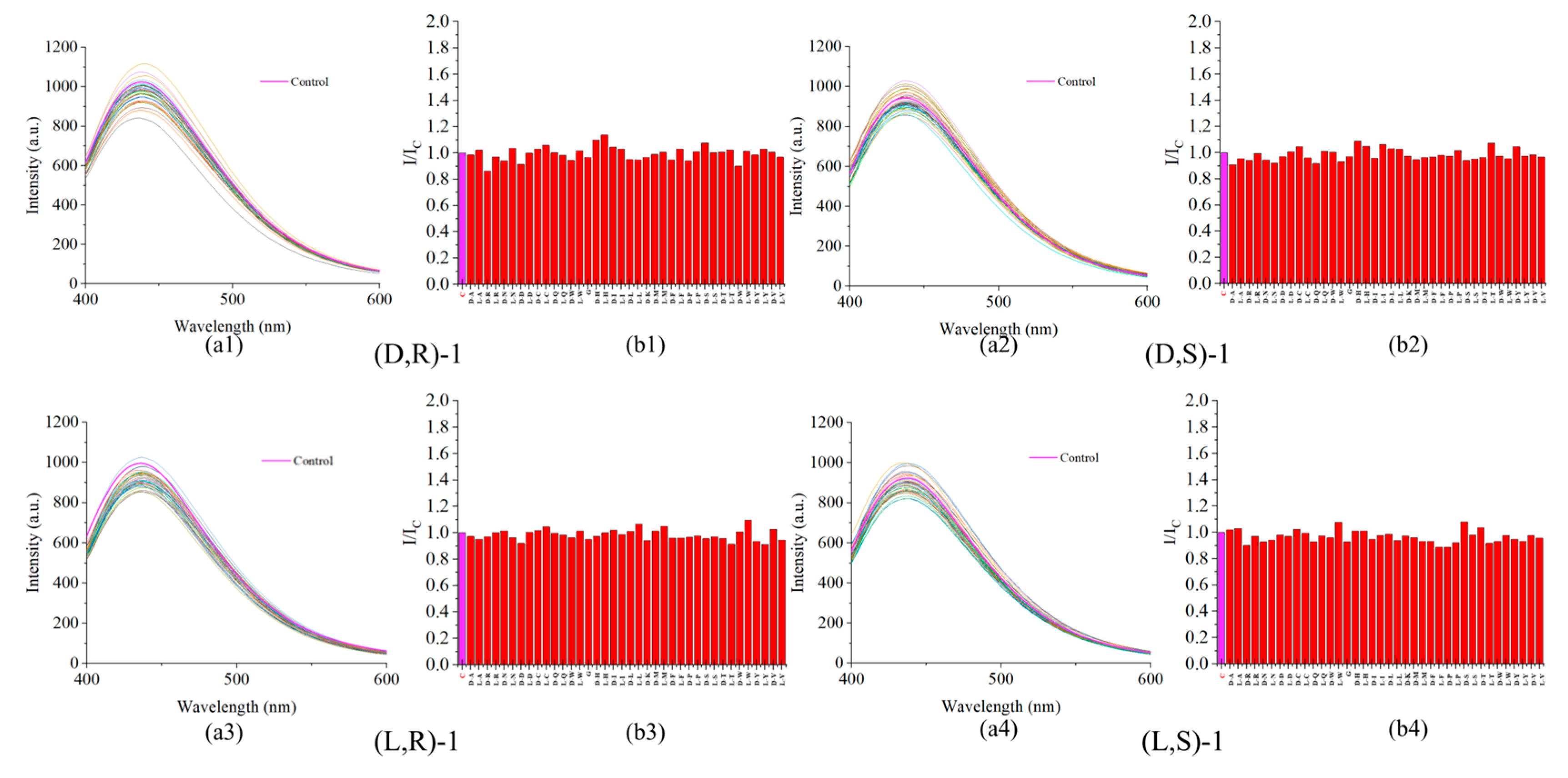

Figure 2.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of probe (0.02 mM) to various amino acids (2 mM). (b) Plot of the fluorescence enhancement I/I0 at 437 nm. (The sequence of amino acids tested includes: D/L-Ala(A), D/L-Arg(R), D/L-Asp(N), D/L-Asp(P), D/L-Cys(C), D/L-Glu(Q), D/L-Glu(E), Gly(G), D/L-His(H), D/L-Iso(I), D/L-Leu(L), D/L-Lys(K), D/L-Met(M), D/L-Phe(F), D/L-Pro(P), D/L-Ser(S), D/L-Thr(T), D/L-Trp(W), D/L-Tyr(Y) ,and D/L-Val(V).).

Figure 2.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of probe (0.02 mM) to various amino acids (2 mM). (b) Plot of the fluorescence enhancement I/I0 at 437 nm. (The sequence of amino acids tested includes: D/L-Ala(A), D/L-Arg(R), D/L-Asp(N), D/L-Asp(P), D/L-Cys(C), D/L-Glu(Q), D/L-Glu(E), Gly(G), D/L-His(H), D/L-Iso(I), D/L-Leu(L), D/L-Lys(K), D/L-Met(M), D/L-Phe(F), D/L-Pro(P), D/L-Ser(S), D/L-Thr(T), D/L-Trp(W), D/L-Tyr(Y) ,and D/L-Val(V).).

Figure 3.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of probe (0.02mM) with L-Lys (2mM) in the presence of other amino acids (2mM). (b) Plot of the fluorescence enhancement I/Ic at 437 nm. (The sequence of amino acids tested includes: Control Group(C), D/L-Ala(A), D/L-Arg(R), D/L-Asp(N), D/L-Asp(P), D/L-Cys(C), D/L-Glu(Q), D/L-Glu(E), Gly(G), D/L-His(H), D/L-Iso(I), D/L-Leu(L), D-Lys(K), D/L-Met(M), D/L-Phe(F), D/L-Pro(P), D/L-Ser(S), D/L-Thr(T), D/L-Trp(W), D/L-Tyr(Y) ,and D/L-Val(V).).

Figure 3.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of probe (0.02mM) with L-Lys (2mM) in the presence of other amino acids (2mM). (b) Plot of the fluorescence enhancement I/Ic at 437 nm. (The sequence of amino acids tested includes: Control Group(C), D/L-Ala(A), D/L-Arg(R), D/L-Asp(N), D/L-Asp(P), D/L-Cys(C), D/L-Glu(Q), D/L-Glu(E), Gly(G), D/L-His(H), D/L-Iso(I), D/L-Leu(L), D-Lys(K), D/L-Met(M), D/L-Phe(F), D/L-Pro(P), D/L-Ser(S), D/L-Thr(T), D/L-Trp(W), D/L-Tyr(Y) ,and D/L-Val(V).).

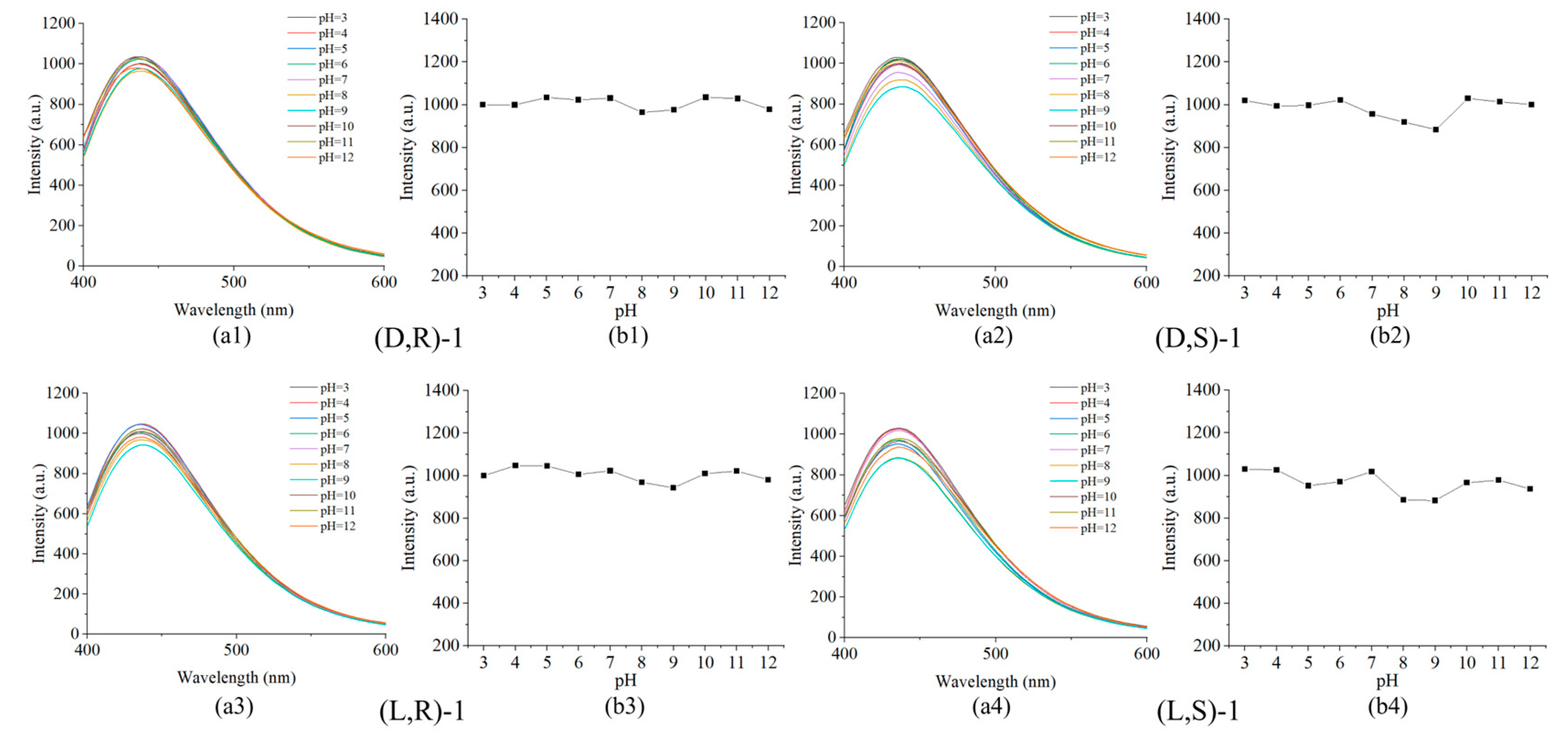

Figure 4.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of probe (0.02mM) with L-Lys (2mM) with a pH range of 3 to 12. (b) Plot of the fluorescence intensity at 437 nm.

Figure 4.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of probe (0.02mM) with L-Lys (2mM) with a pH range of 3 to 12. (b) Plot of the fluorescence intensity at 437 nm.

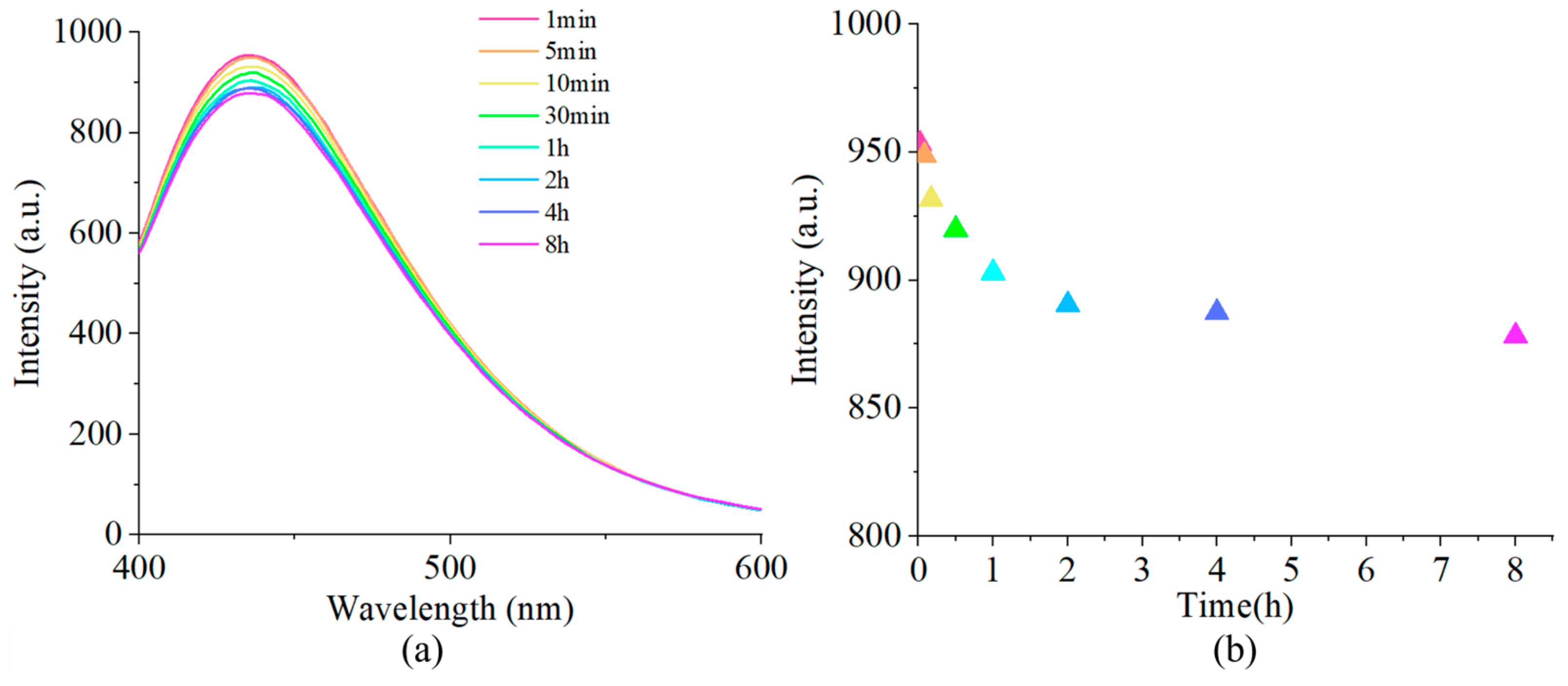

Figure 5.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of probe (0.02mM) with L-Lys (2mM) at 1 min, 5 min, 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 8 h. (b) Plot of the fluorescence intensity at 437 nm.

Figure 5.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of probe (0.02mM) with L-Lys (2mM) at 1 min, 5 min, 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 8 h. (b) Plot of the fluorescence intensity at 437 nm.

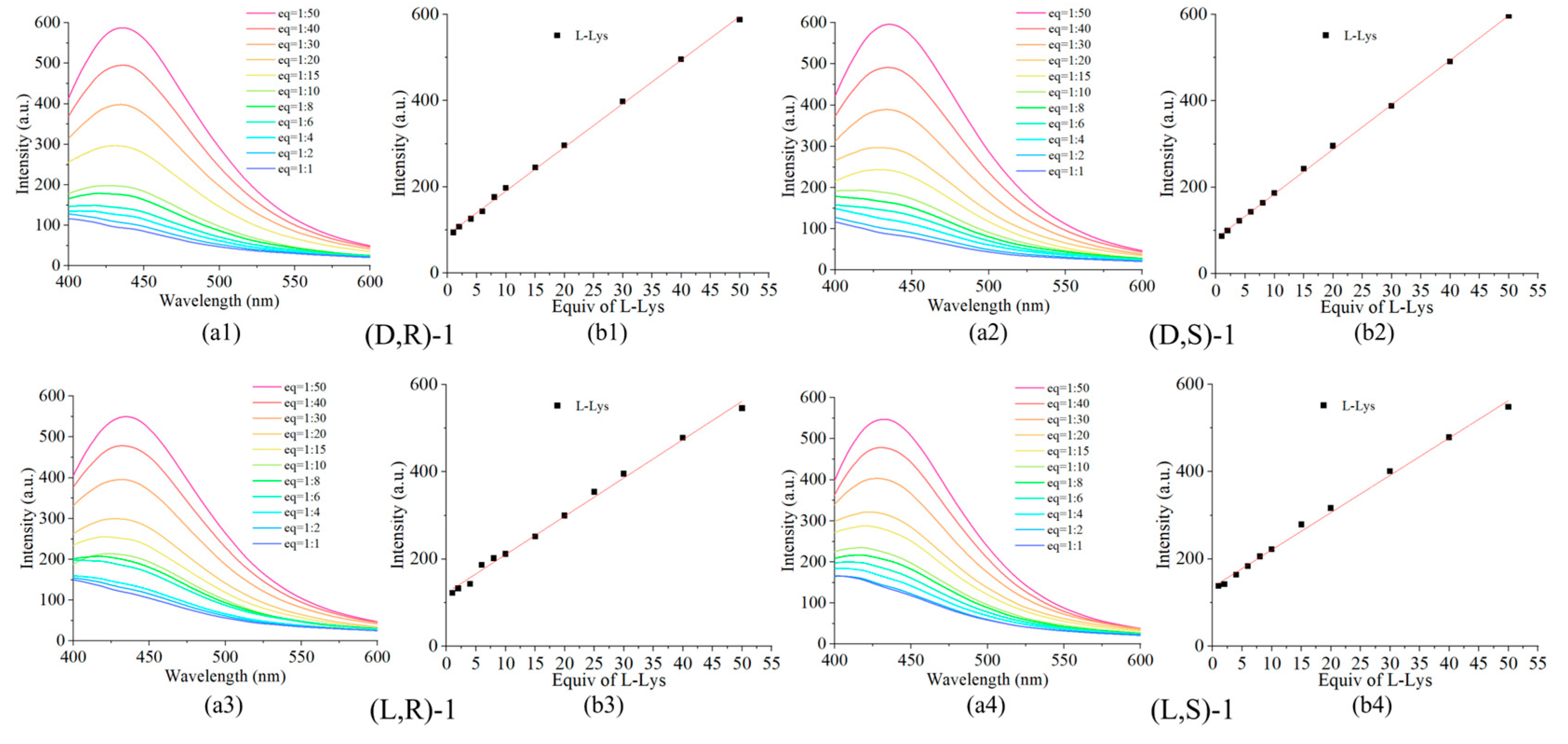

Figure 6.

(a) Fluorescence spectra for the gradient recognition of 1 to 50 equivalents of L-Lys by the probe (0.02 mM) concentration. (b) Plot of the fluorescence intensity at 437 nm.

Figure 6.

(a) Fluorescence spectra for the gradient recognition of 1 to 50 equivalents of L-Lys by the probe (0.02 mM) concentration. (b) Plot of the fluorescence intensity at 437 nm.

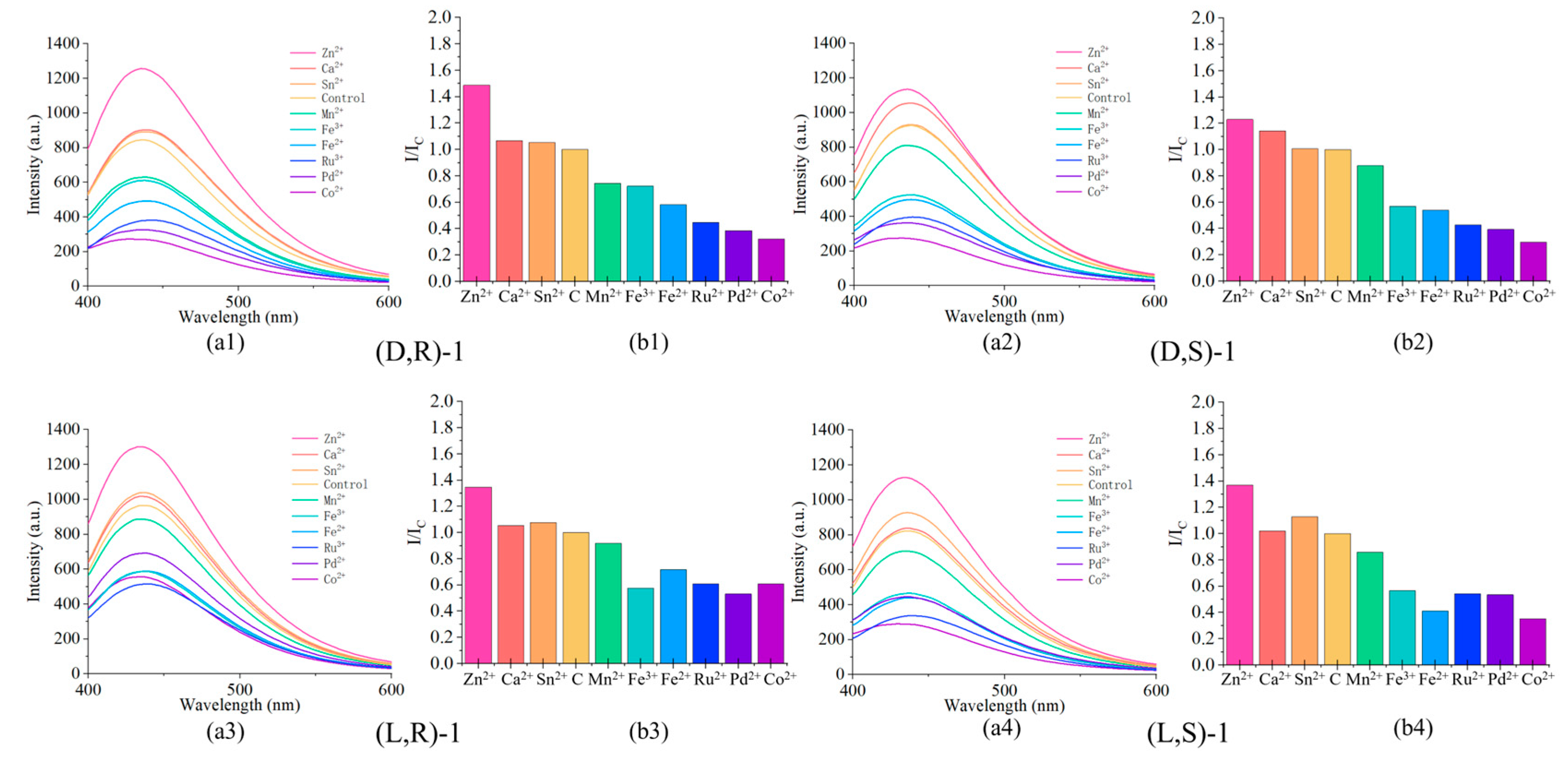

Figure 7.

(a) Fluorescence spectrum upon addition of 2 equivalents of: Co2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Mn2+, Pd2+, Ru3+, Zn2+, Sn2+, and Ca2+ to the probe. (b) Plot of the fluorescence intensity at 437 nm.

Figure 7.

(a) Fluorescence spectrum upon addition of 2 equivalents of: Co2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Mn2+, Pd2+, Ru3+, Zn2+, Sn2+, and Ca2+ to the probe. (b) Plot of the fluorescence intensity at 437 nm.

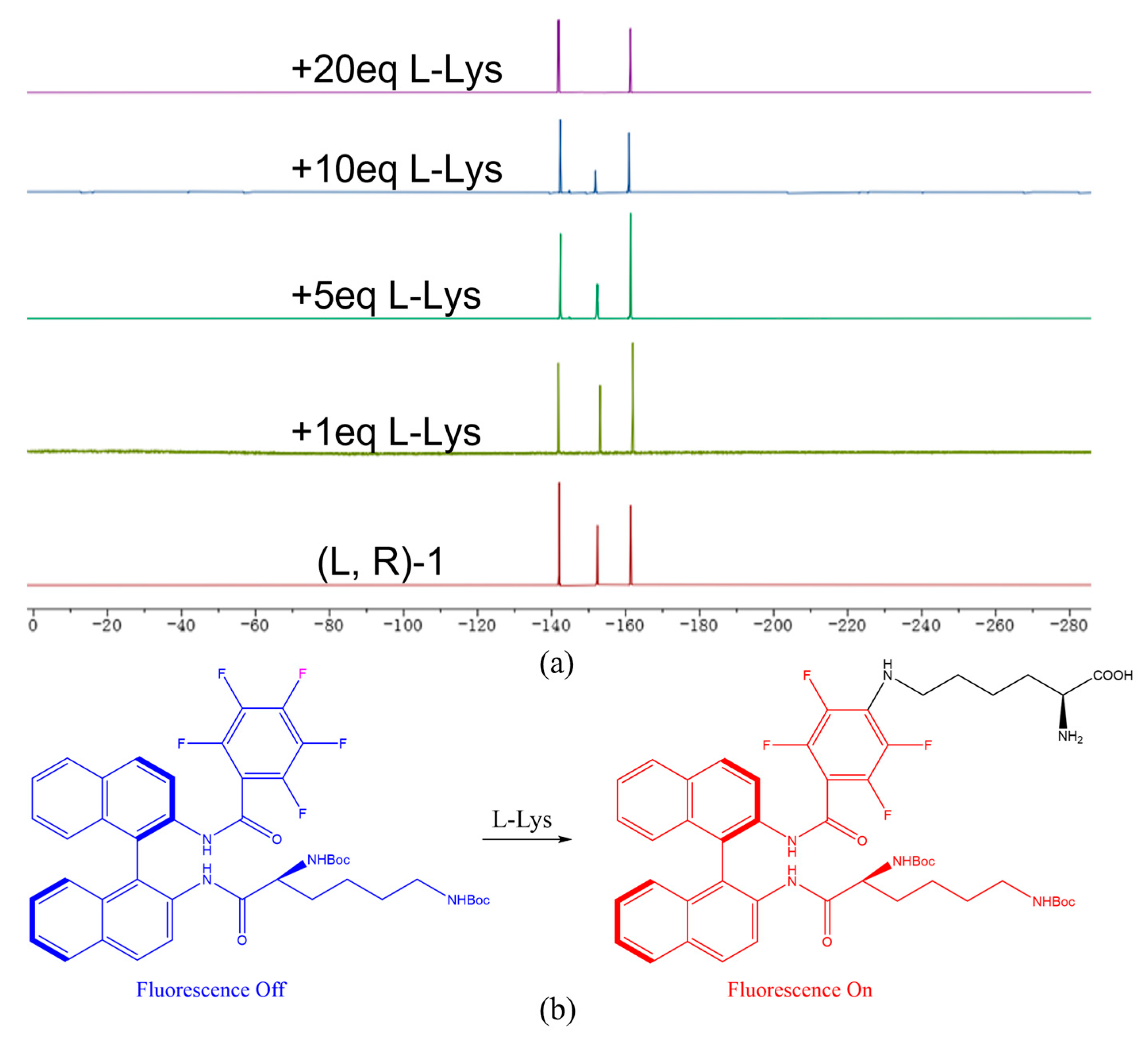

Figure 8.

(a) 19F NMR spectra of (L, R)-1 treated with 0- 20 equivalents of L-Lys. (b) (L, R)-1 showed significant fluorescence enhancement for L-Lys through nucleophilic substitution.

Figure 8.

(a) 19F NMR spectra of (L, R)-1 treated with 0- 20 equivalents of L-Lys. (b) (L, R)-1 showed significant fluorescence enhancement for L-Lys through nucleophilic substitution.