Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

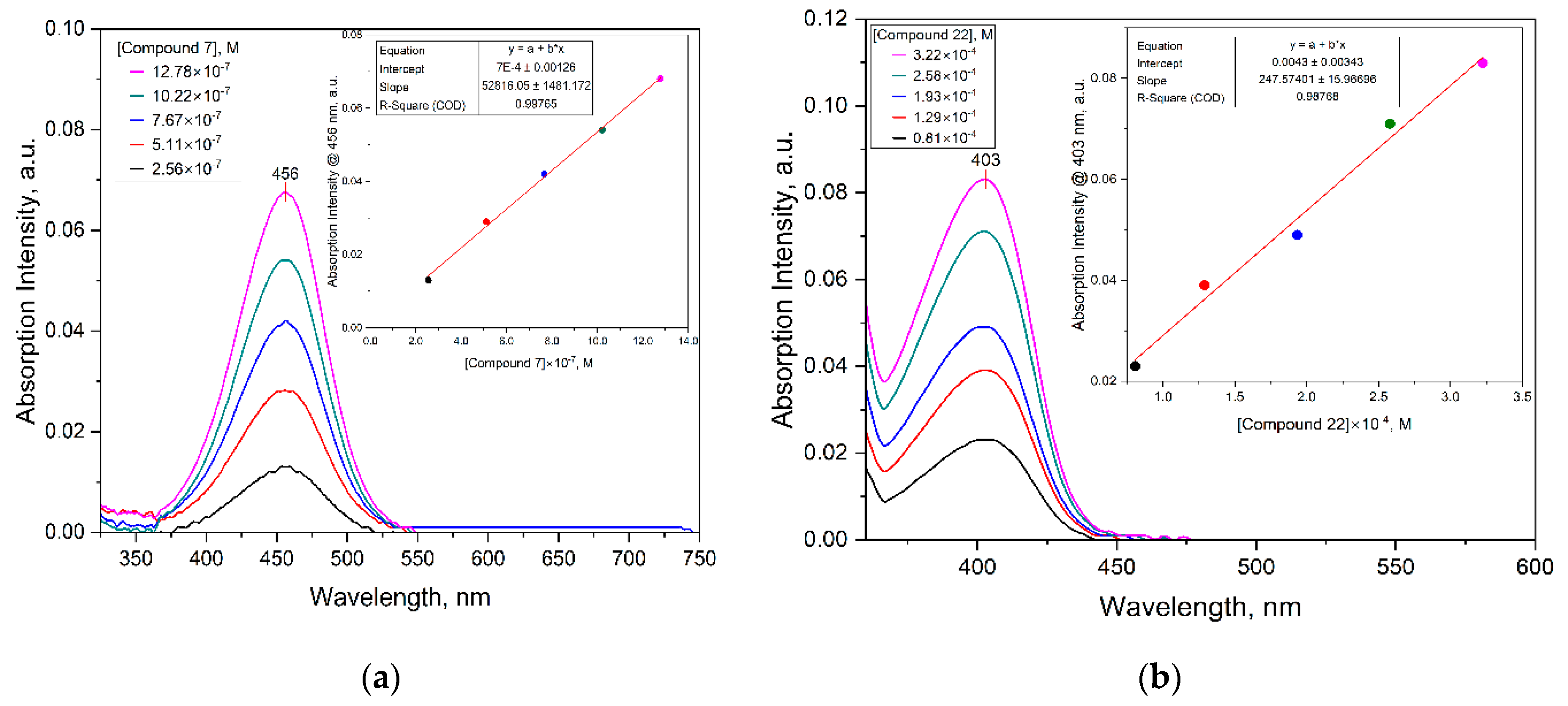

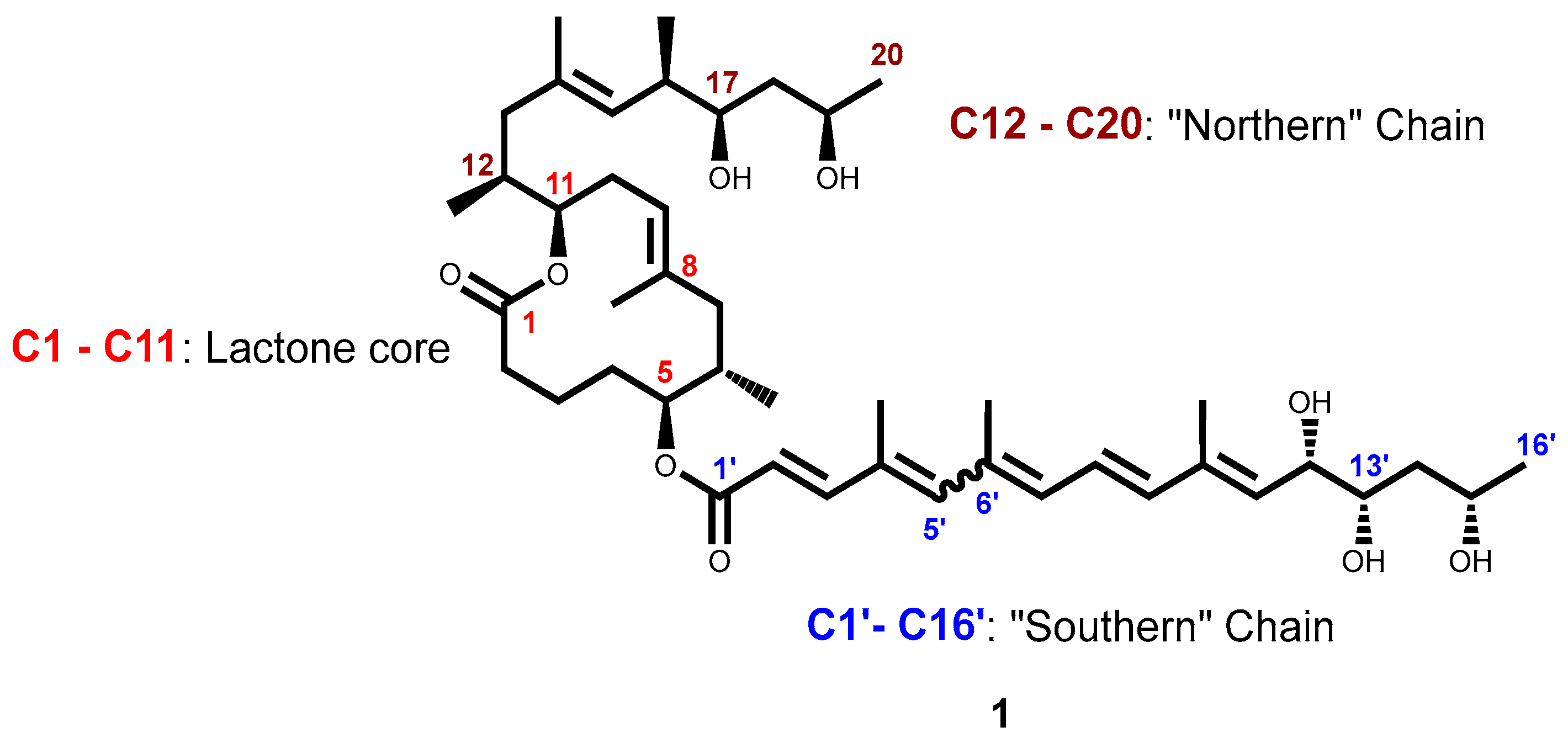

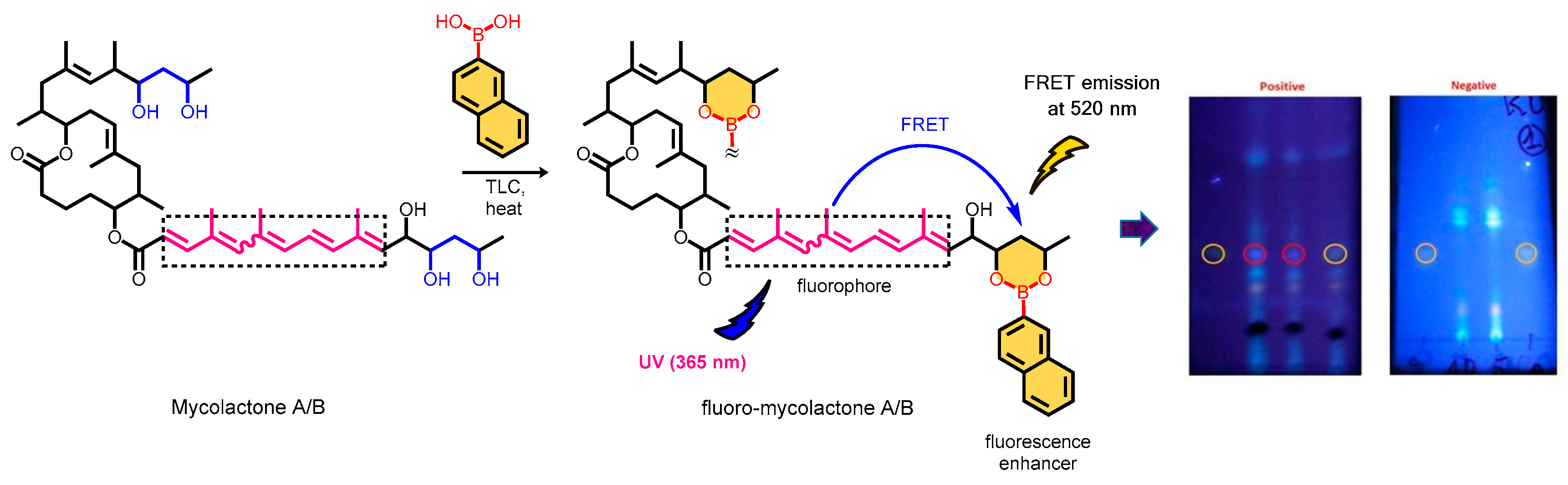

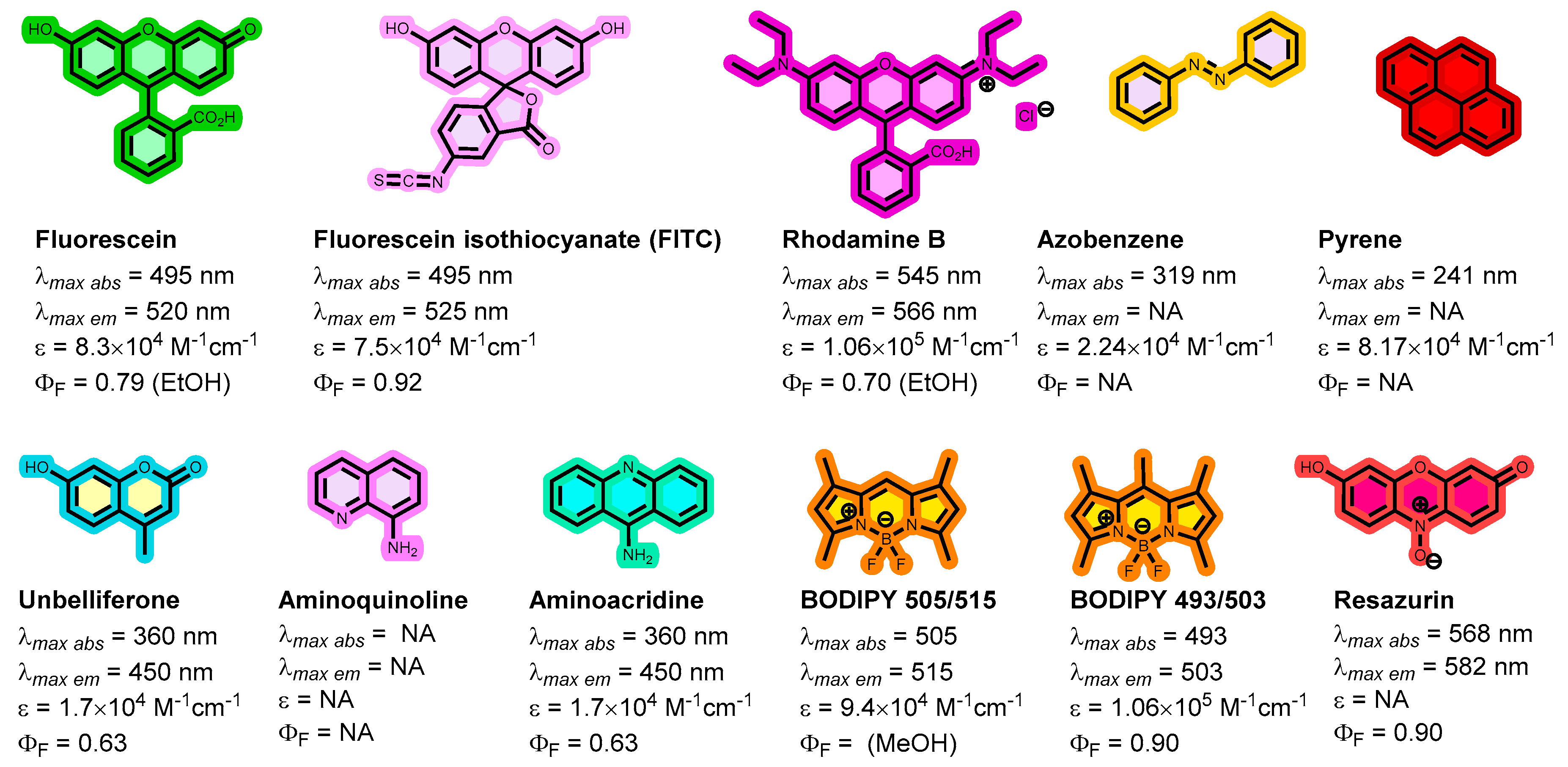

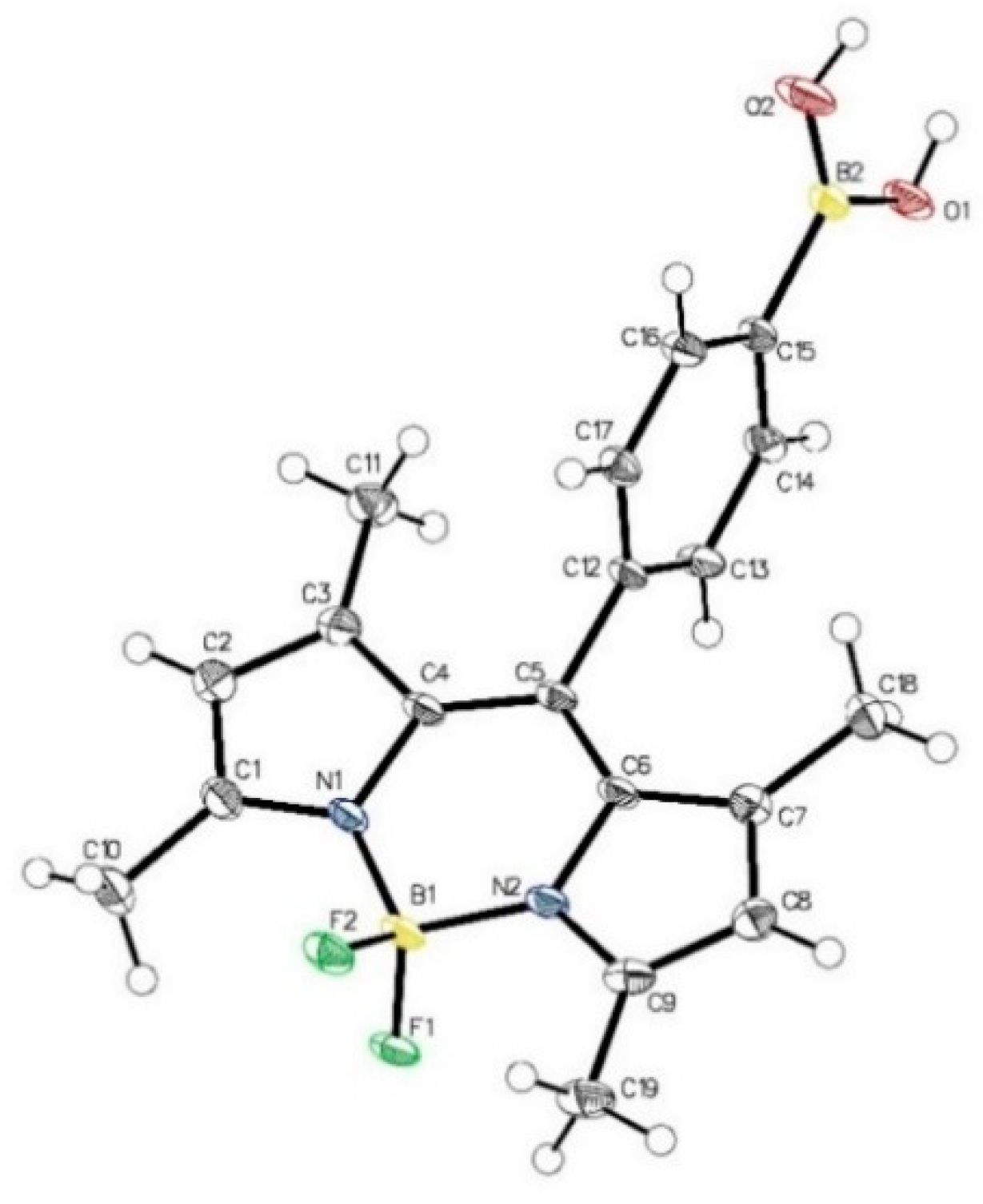

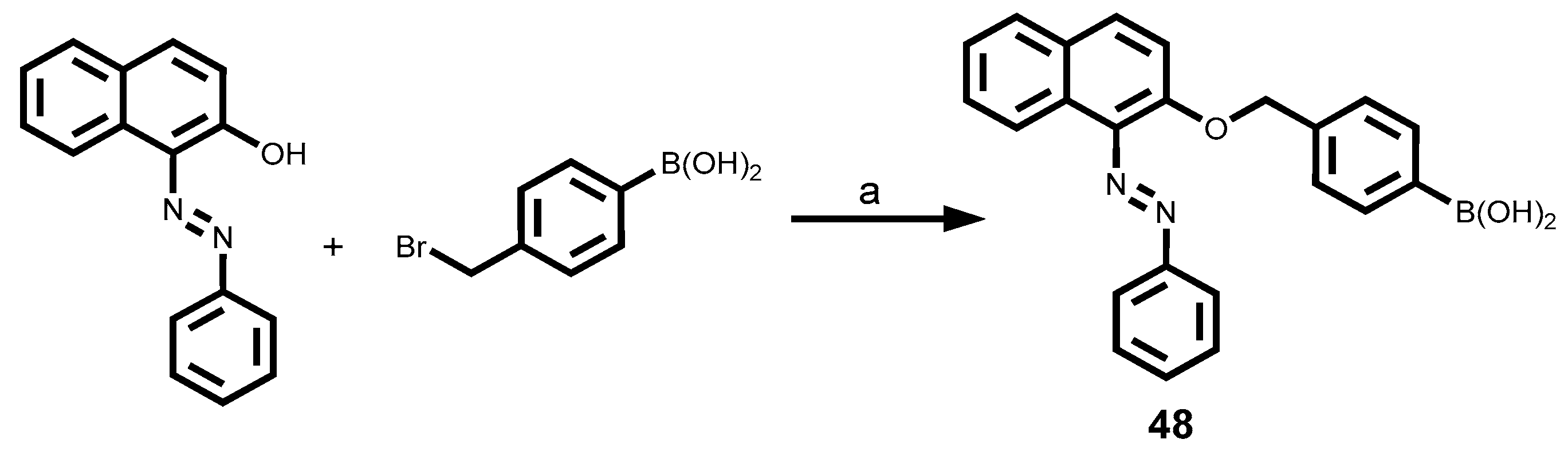

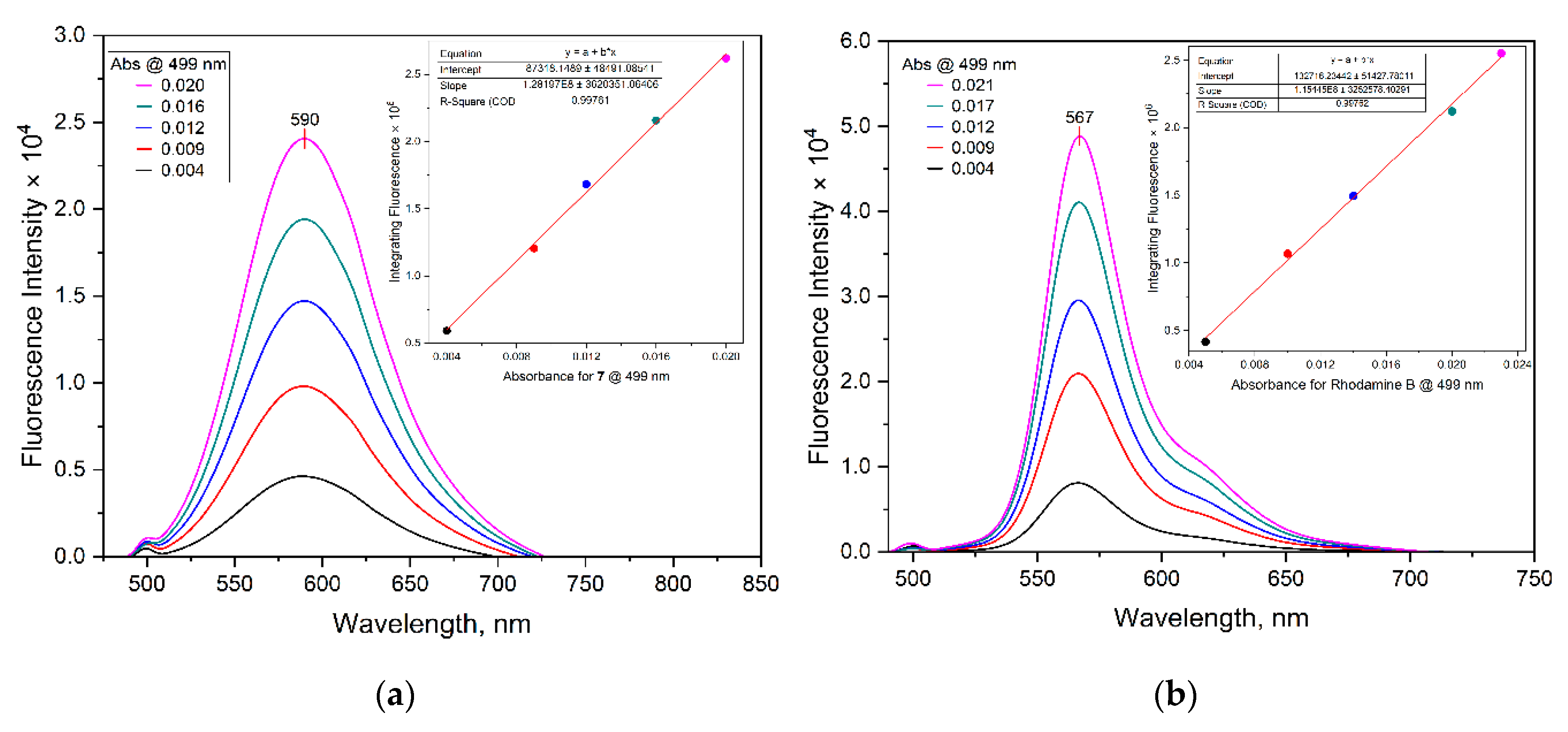

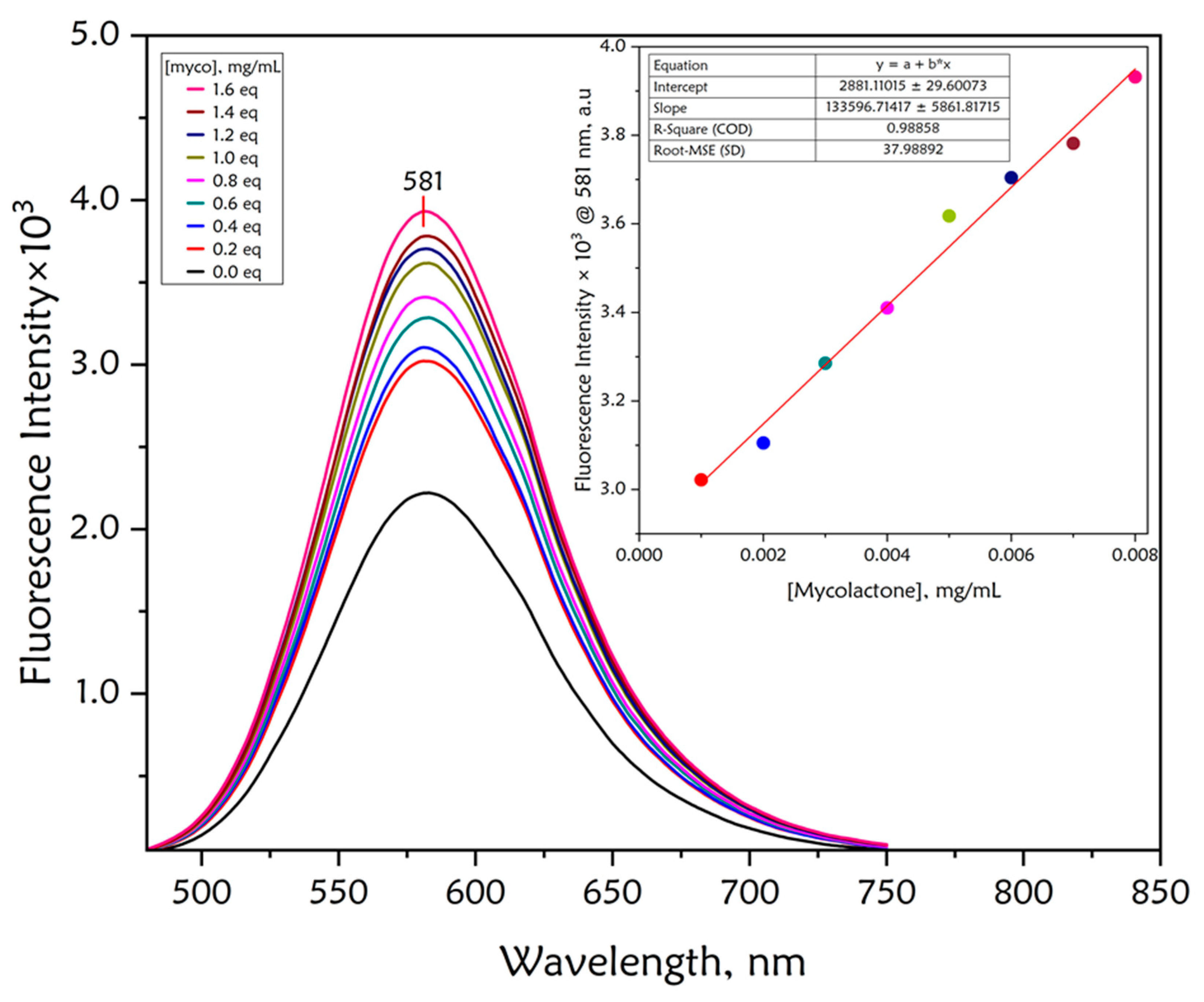

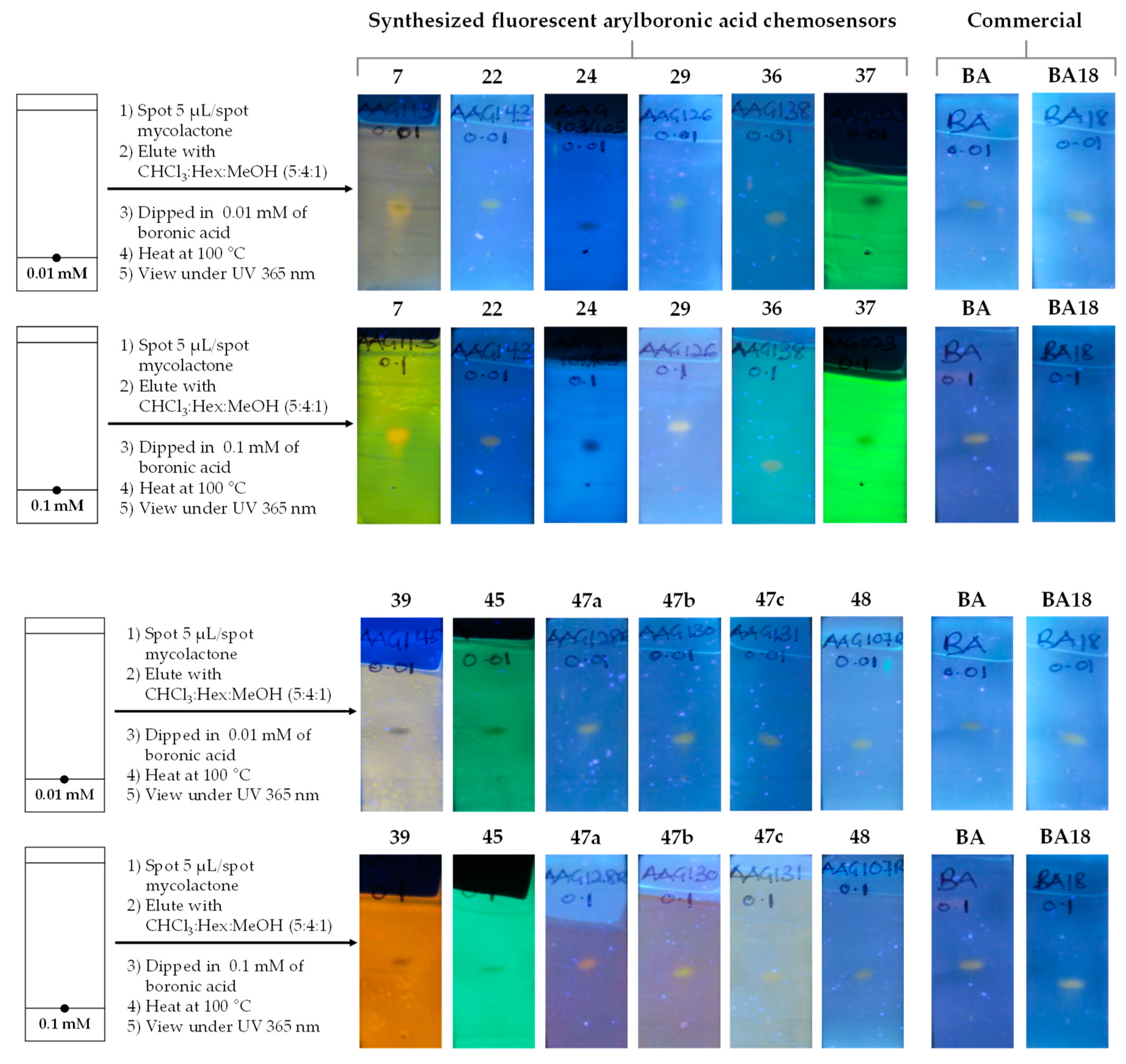

Fluorescent chemosensors are increasingly becoming relevant in recognition chemistry due to their sensitivity, selectivity, fast response time, real-time detection capability, and low cost. Boronic acids have been reported for the recognition of mycolactone, the cytotoxin responsible for tissue damage in Buruli ulcer disease. A library of fluorescent arylboronic acid chemosensors with various signaling moieties with certain beneficial photophysical characteristics (i.e. aminoacridine, aminoquinoline, azo, BODIPY, coumarin, fluorescein, and rhodamine variants); and a recognition moiety (i.e. boronic acid unit) were rationally designed and synthesized using combinatorial approaches; purified and fully characterized using a set of complementary spectrometric and spectroscopic techniques such as NMR, LC-MS, FT-IR, and X-ray crystallography. In addition, a complete set of basic photophysical quantities such as absorption maxima (labsmax), emission maxima (lemmax), Stokes shift (∆λ), molar extinction coefficient (ε), fluorescence quantum yield (ΦF), and brightness were determined using UV-vis absorption and fluorescence emission spectroscopy techniques. The synthesized arylboronic acid chemosensors were investigated as chemosensors for mycolactone detection using the fluorescent-thin layer chromatography (f-TLC) method. Compound 7 (with a coumarin core) emerged the best (labsmax = 456 nm, (lemmax = 590 nm, ∆λ = 134 nm, ε = 52816 M-1cm-1, ΦF = 0.78, and brightness = 41197 M-1cm-1).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Instruments

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization

2.3. Categories of Fluorescent Arylboronic Acid Chemosensor Dyes

2.3.1. Coumarin Dyes

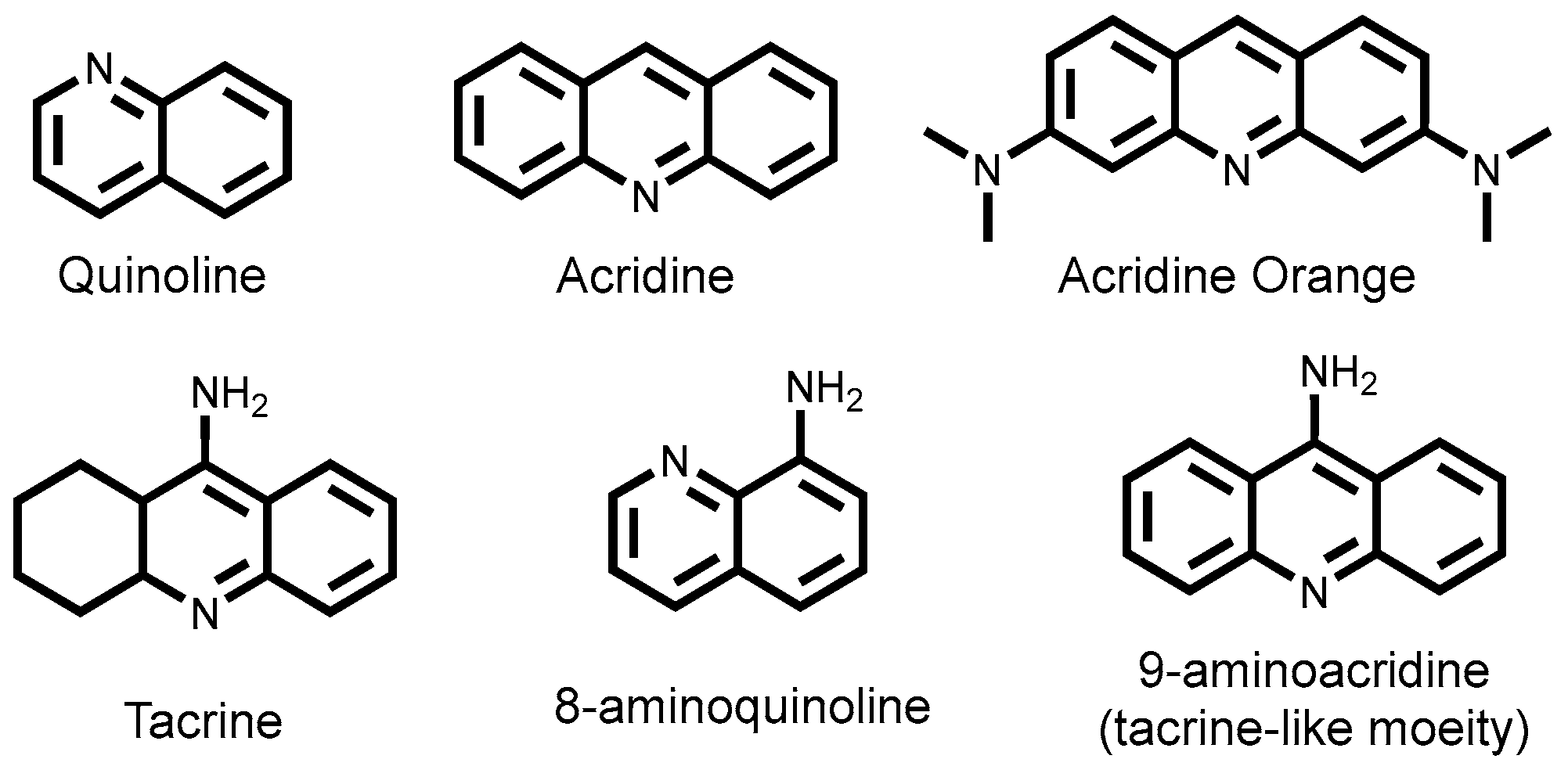

2.3.2. 9-Aminoacridine Dyes

2.3.3. 8-Aminoquinoline Dyes

2.3.4. Fluorescein Dyes

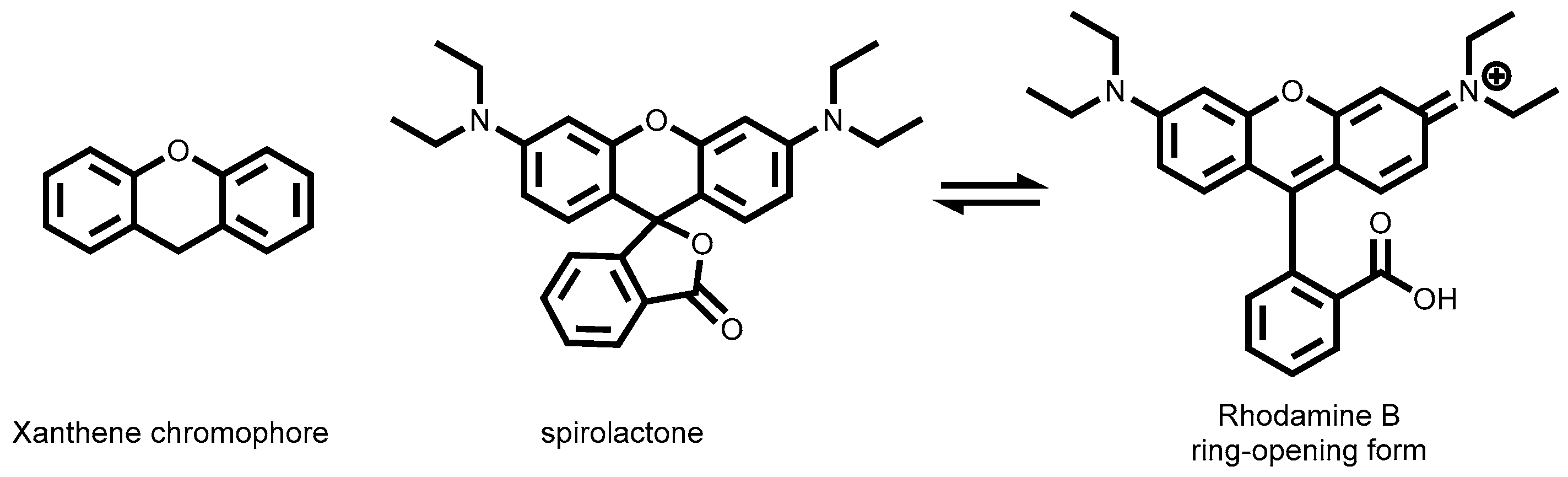

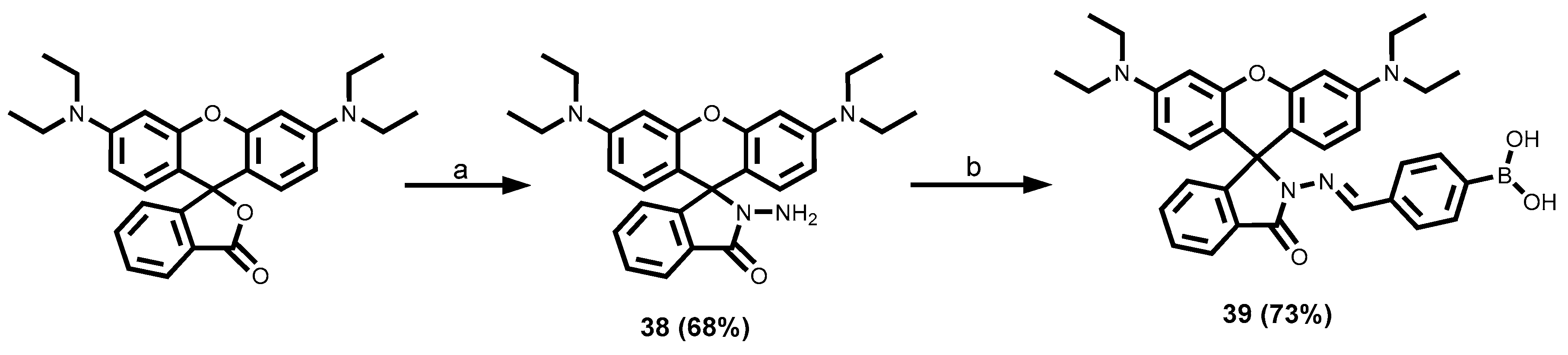

2.3.5. Rhodamine Dyes

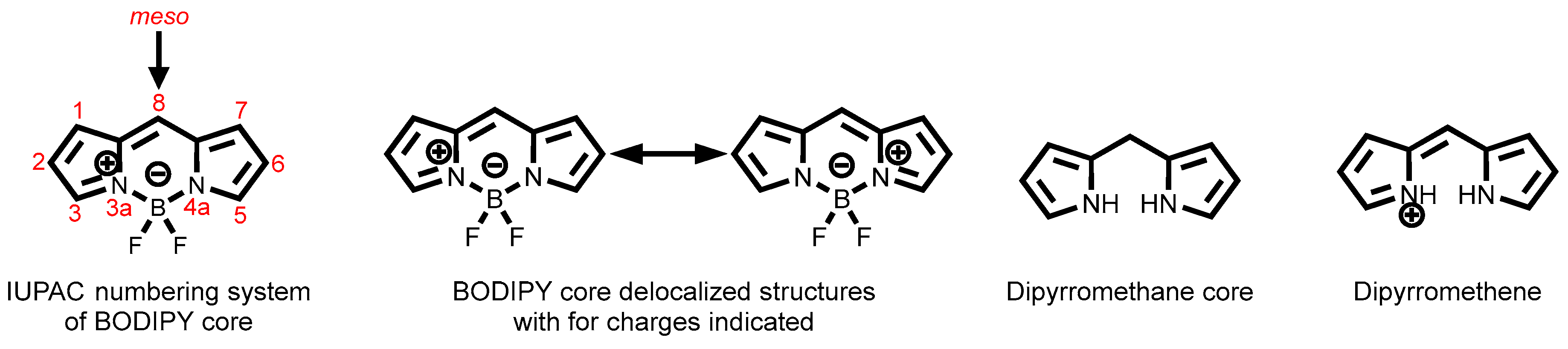

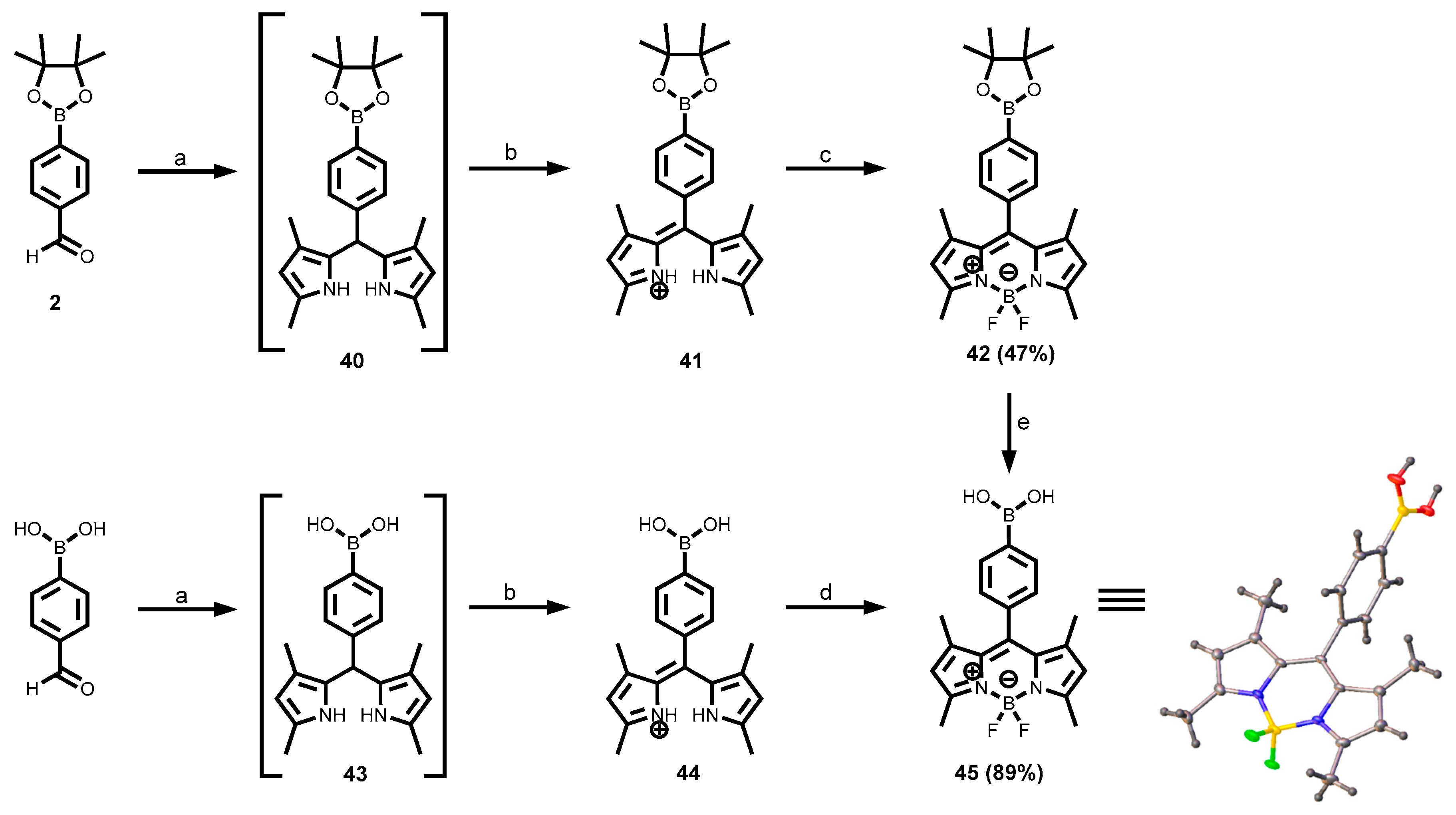

2.3.6. BODIPY Dyes

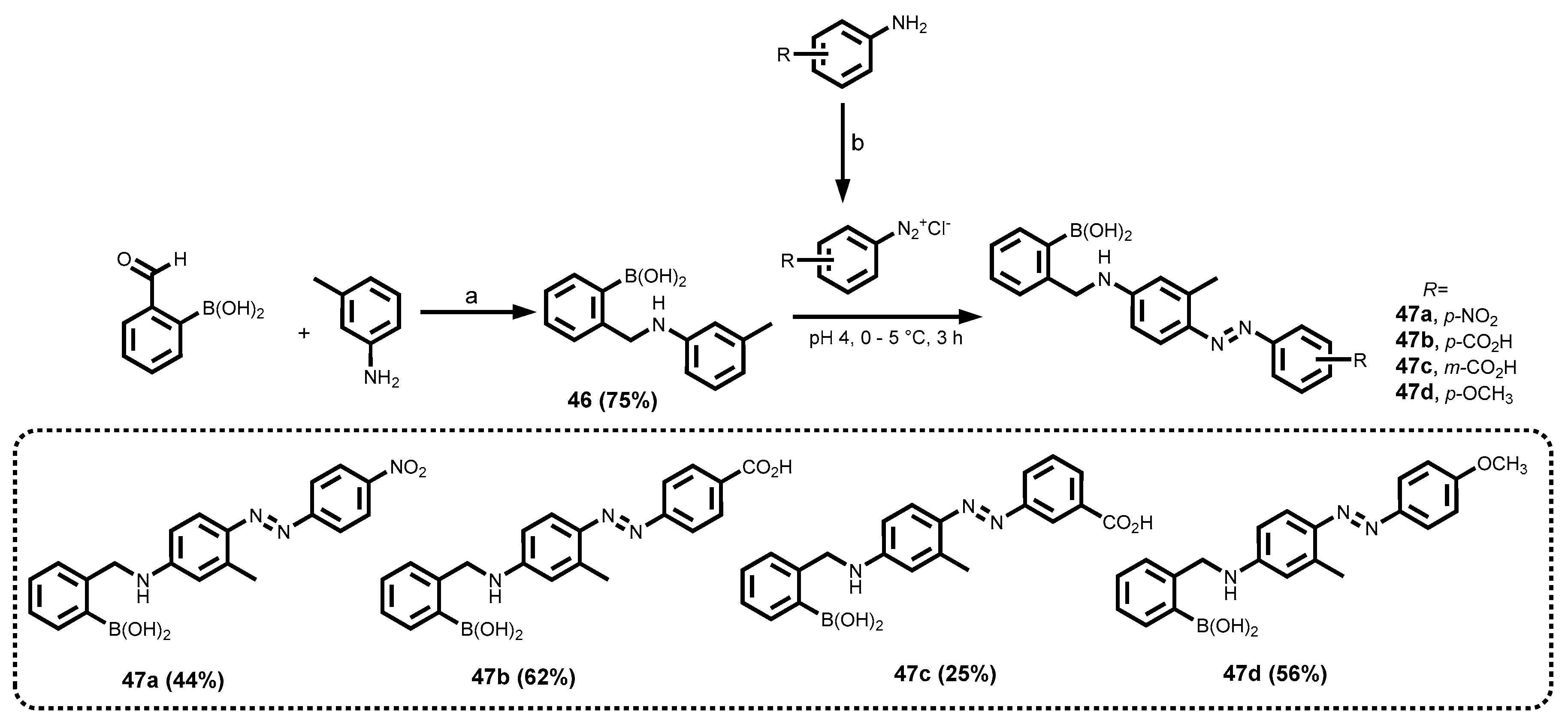

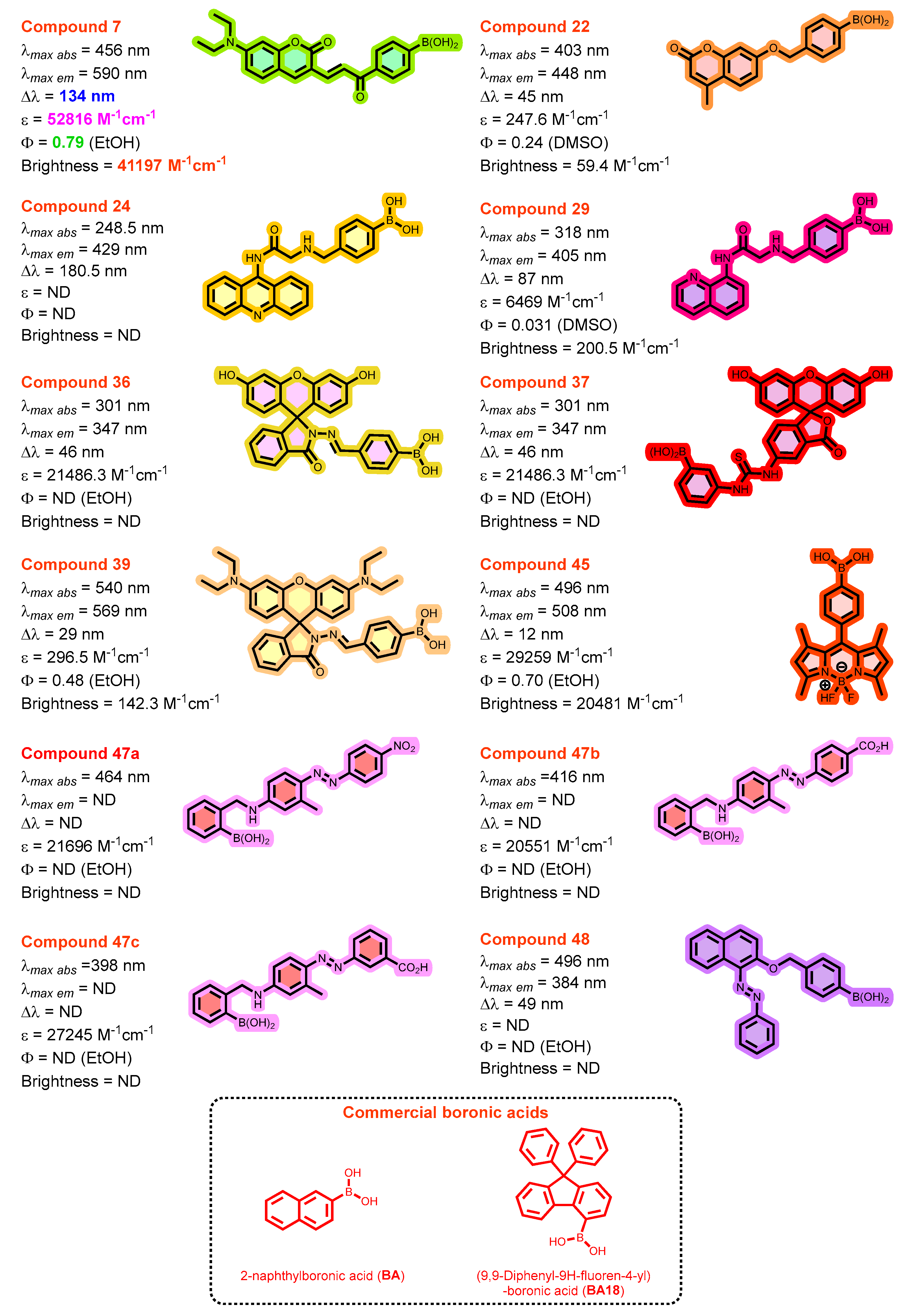

2.3.7. Azo Dyes

2.3.8. Sudan I Dyes Boronic Acid

2.4. Measurements of Photophysical Properties of Synthesized Compounds

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Various Arylboronic Acid Chemosensors Fluorescent Dyes

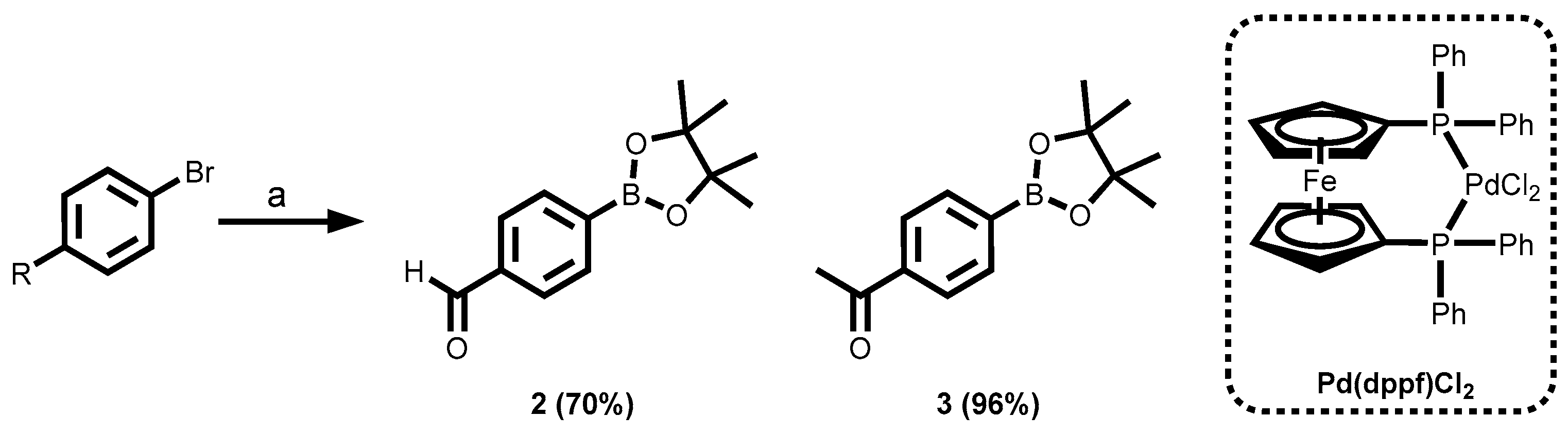

3.1.1. Synthesis of the Building Blocks Through Miyaura Borylation

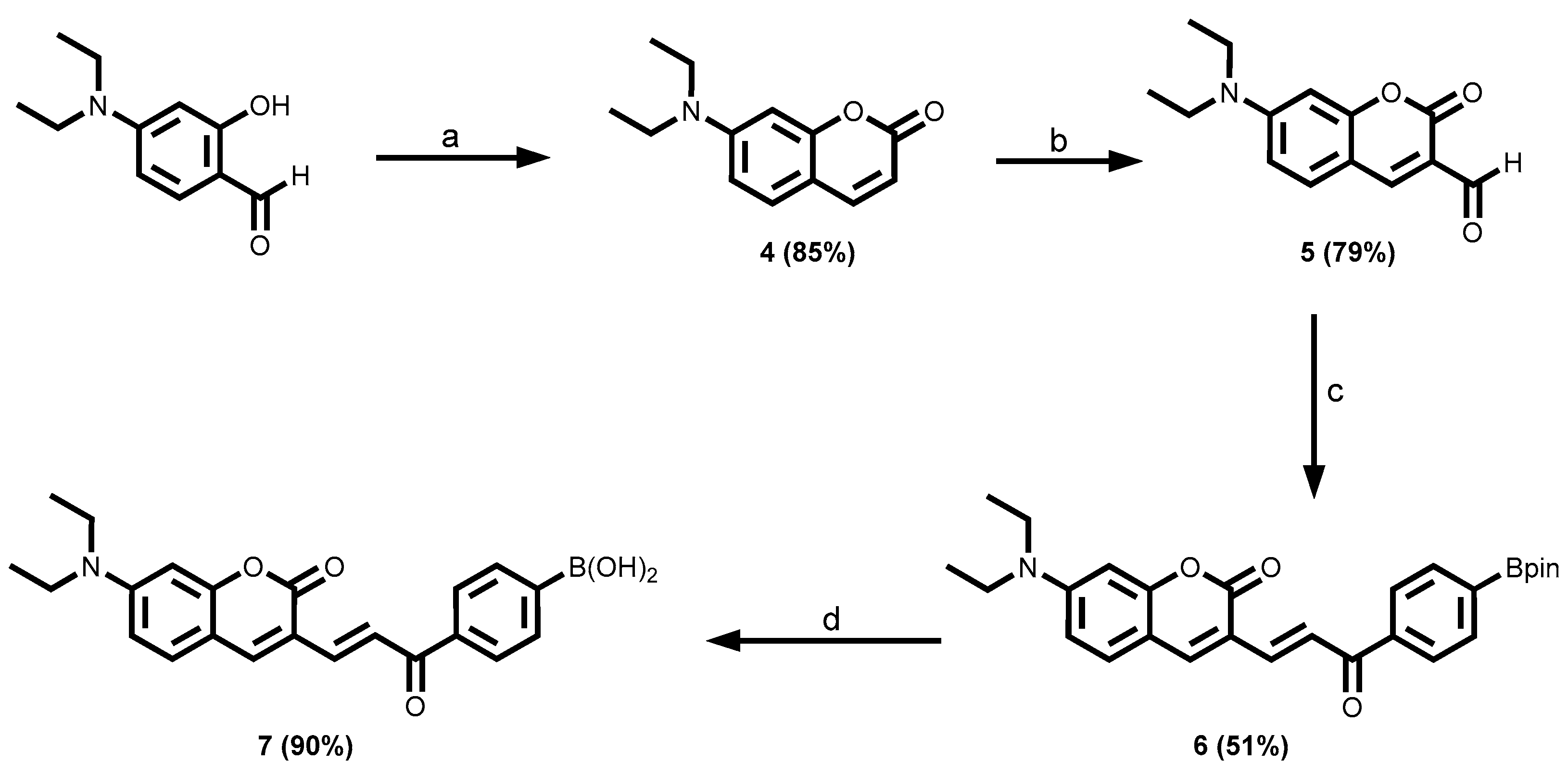

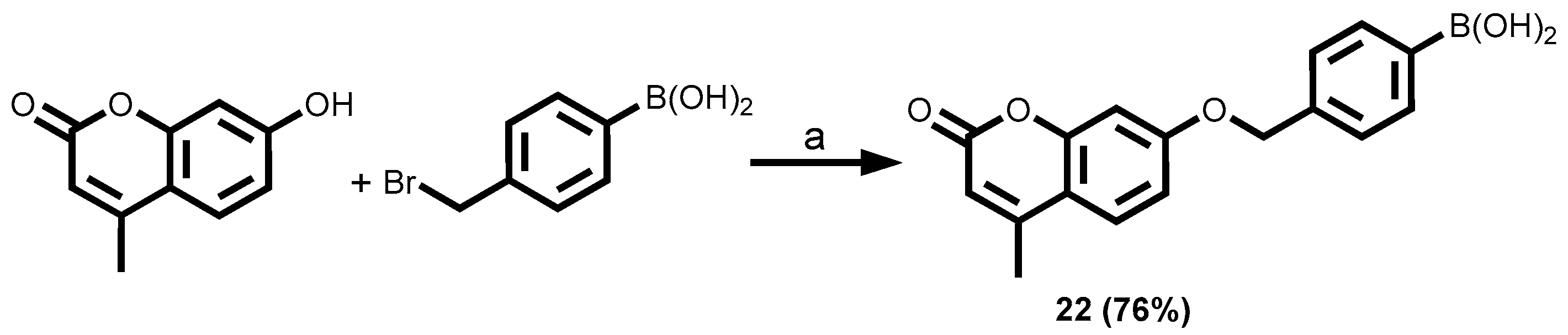

3.1.2. Coumarin-Tagged Boronic Acids

3.1.3. 9-Aminoacridine-Tagged Boronic Acid Dyes

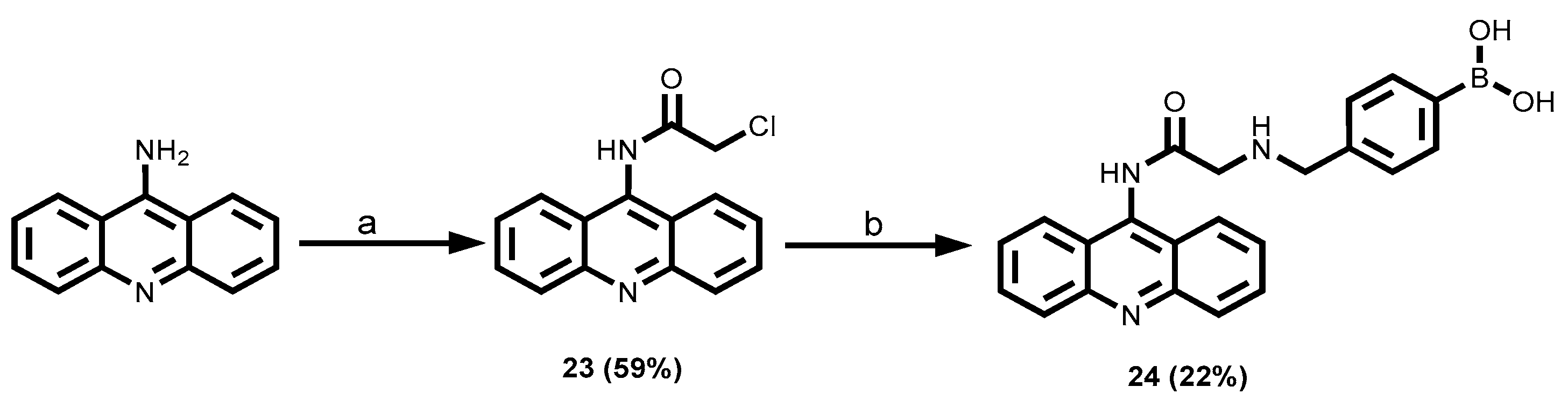

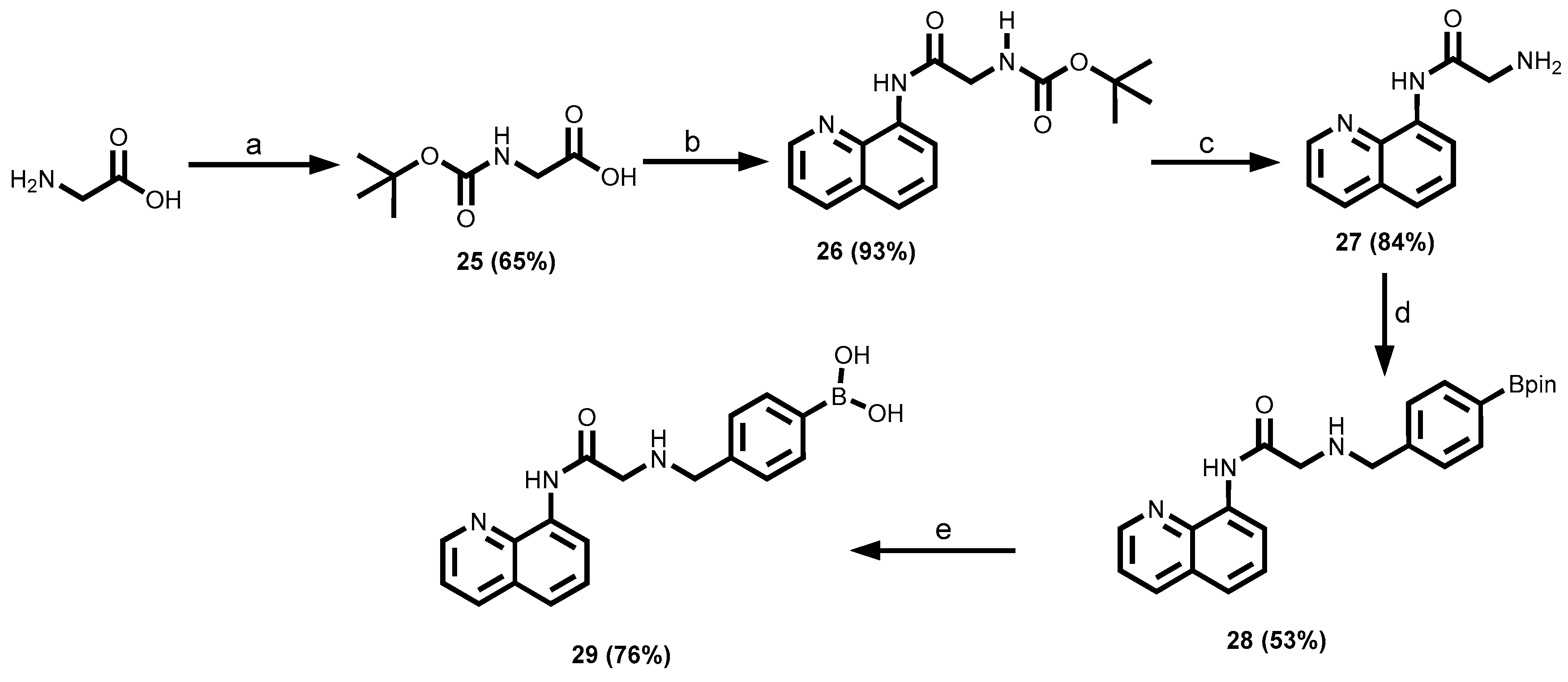

3.1.4. 8-Aminoquinoline-Tagged Boronic Acid Dyes

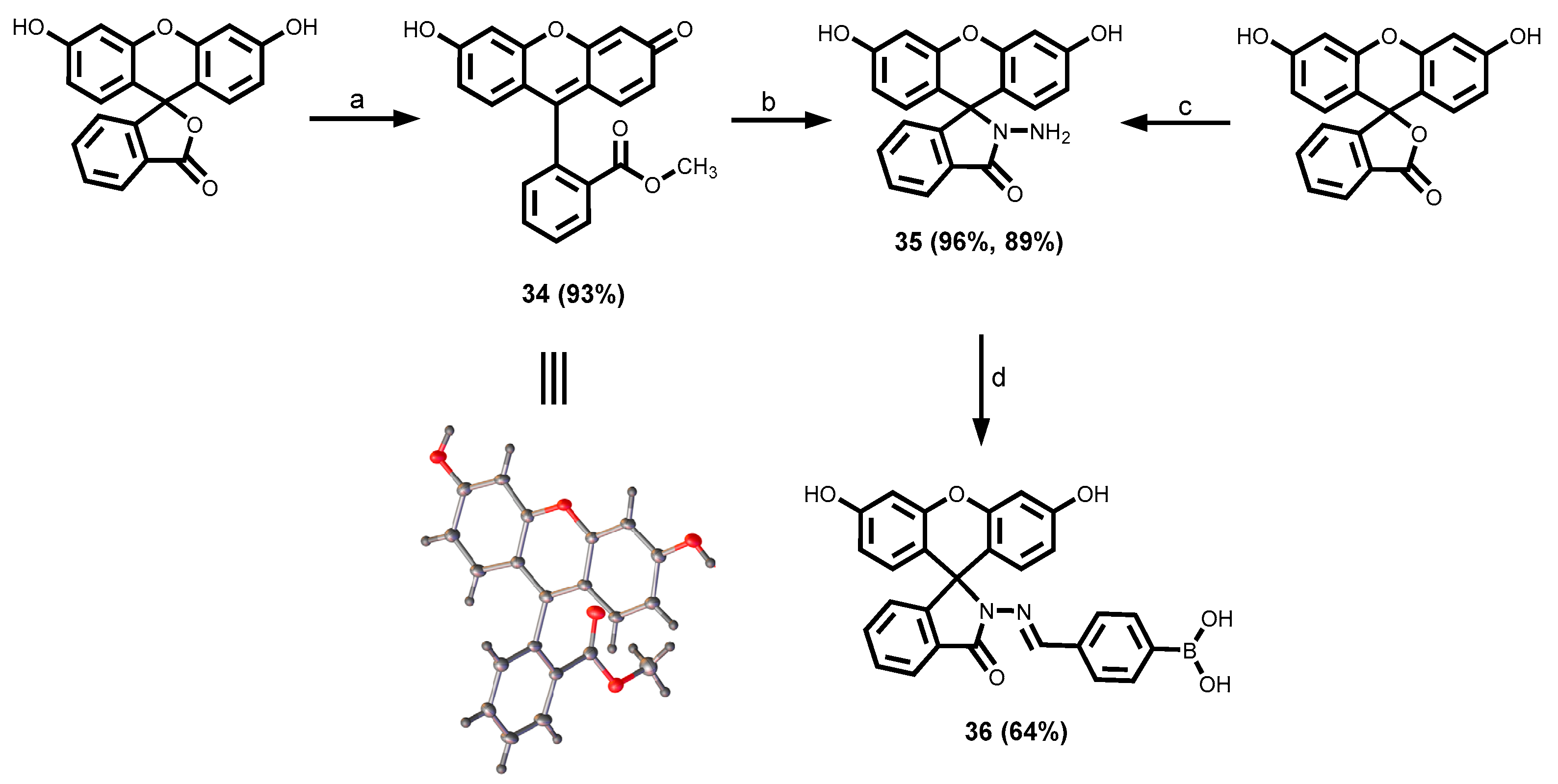

3.1.5. Fluorescein-Tagged Boronic Acid Dyes

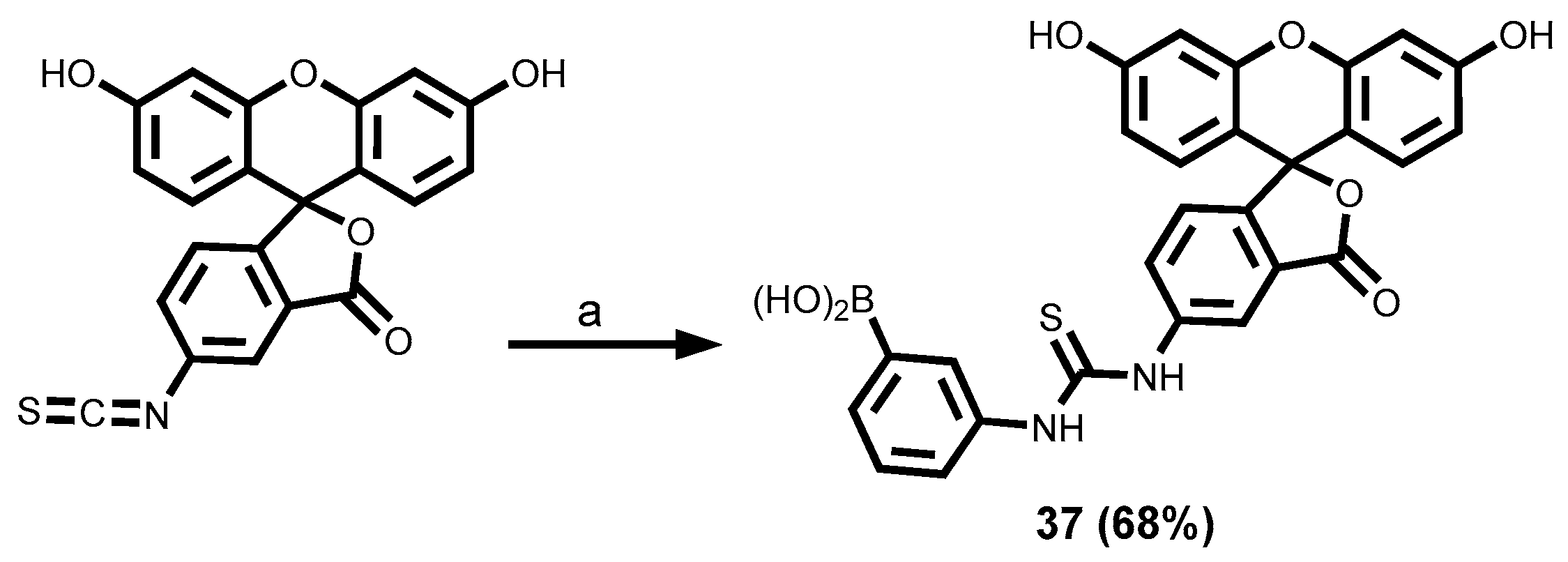

3.1.6. Rhodamine-Tagged Boronic Acid Dye

3.1.7. BODIPY-Tagged Boronic Acid Dyes

3.1.8. Azo-Tagged Boronic Acid Dyes

3.1.9. Sudan I Boronic Acid Dye

3.2. Photophysical Properties of the Different Arylboronic Acid Chemosensor Dyes

3.3. Detection of Mycolactone by the f-TLC Method Using the Synthesized Dyes

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whyte, G.F.; Vilar, R.; Woscholski, R. Molecular recognition with boronic acids—applications in chemical biology. Journal of Chemical Biology 2013, 6, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Czarnik, A.W. Chemosensors of ion and molecule recognition; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012; Volume 492. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.-S.; Liu, W.-M.; Zhuang, X.-Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, P.-F.; Tao, S.-L.; Zhang, X.-H.; Wu, S.-K.; Lee, S.-T. Fluorescence Turn on of Coumarin Derivatives by Metal Cations: A New Signaling Mechanism Based on C=N Isomerization. Organic Letters 2007, 9, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valeur, B.; Berberan-Santos, M.N. Molecular fluorescence: principles and applications; John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tharmaraj, V.; Pitchumani, K. d-Glucose sensing by (E)-(4-((pyren-1-ylmethylene)amino)phenyl) boronic acid via a photoinduced electron transfer (PET) mechanism. RSC Advances 2013, 3, 11566–11570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtius, H.; Kaiser, G.; Müller, E.; Bosbach, D. Radionuclide release from research reactor spent fuel. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2011, 416, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Chen, X.-X.; Jiang, Y.-B. Recent advances in boronic acid-based optical chemosensors. Analyst 2017, 142, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.G. Boronic Acids. 2011.

- Springsteen, G.; Wang, B. A detailed examination of boronic acid–diol complexation. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 5291–5300. [Google Scholar]

- Springsteen, G.; Wang, B. Alizarin Red S. as a general optical reporter for studying the binding of boronic acids with carbohydrates. Chemical Communications 2001, 1608–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Lorand, J.P.; EDWARDS, J.O. Polyol complexes and structure of the benzeneboronate ion. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 1959, 24, 769–774. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.; Czarnik, A.W. Fluorescent chemosensors of carbohydrates. A means of chemically communicating the binding of polyols in water based on chelation-enhanced quenching. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1992, 114, 5874–5875. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Shin, I.; Yoon, J. Recognition and sensing of various species using boronic acid derivatives. Chemical Communications 2012, 48, 5956–5967. [Google Scholar]

- Lacina, K.; Skládal, P.; James, T.D. Boronic acids for sensing and other applications - a mini-review of papers published in 2013. Chemistry Central Journal 2014, 8, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Chaicham, A.; Sahasithiwat, S.; Tuntulani, T.; Tomapatanaget, B. Highly effective discrimination of catecholamine derivatives via FRET-on/off processes induced by the intermolecular assembly with two fluorescence sensors. Chemical Communications 2013, 49, 9287–9289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Fang, H.; Gao, X.; Li, H.; Wang, B. Substituent effect on anthracene-based bisboronic acid glucose sensors. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 2583–2589. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Mitra, N.; Yan, E.C.; Zhou, S. Multifunctional hybrid nanogel for integration of optical glucose sensing and self-regulated insulin release at physiological pH. Acs Nano 2010, 4, 4831–4839. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Zhou, T.; Berliner, A.; Banerjee, P.; Zhou, S. Glucose-Mediated Assembly of Phenylboronic Acid Modified CdTe/ZnTe/ZnS Quantum Dots for Intracellular Glucose Probing. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2010, 49, 6554–6558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-J.; Ouyang, W.-J.; Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Fossey, J.S.; James, T.D.; Jiang, Y.-B. Glucose sensing via aggregation and the use of “knock-out” binding to improve selectivity. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2013, 135, 1700–1703. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, W.; Male, L.; Fossey, J.S. Glucose selective bis-boronic acid click-fluor. Chemical Communications 2017, 53, 2218–2221. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, G.F.; Vilar, R.; Woscholski, R. Molecular recognition with boronic acids-applications in chemical biology. J Chem Biol 2013, 6, 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Pohanka, M. Glycated Hemoglobin and Methods for Its Point of Care Testing. Biosensors 2021, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhou, X.; Xing, D. Ultrasensitive and selective detection of mercury (II) in aqueous solution by polymerase assisted fluorescence amplification. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2011, 26, 2666–2669. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, R.; Chen, H.; Cao, F.; Cao, D.; Deng, Y. Two fluorescence turn-on chemosensors for cyanide anions based on pyridine cation and the boronic acid moiety. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2013, 38, 112–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.A.; You, G.R.; Choi, Y.W.; Jo, H.Y.; Kim, A.R.; Noh, I.; Kim, S.-J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, C. A new multifunctional Schiff base as a fluorescence sensor for Al 3+ and a colorimetric sensor for CN− in aqueous media: an application to bioimaging. Dalton Transactions 2014, 43, 6650–6659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pizer, R.; Tihal, C. Equilibria and reaction mechanism of the complexation of methylboronic acid with polyols. Inorganic chemistry 1992, 31, 3243–3247. [Google Scholar]

- Pizer, R.D.; Tihal, C.A. Mechanism of boron acid/polyol complex formation. comments on the trigonal/tetrahedral interconversion on boron. Polyhedron 1996, 15, 3411–3416. [Google Scholar]

- DeFrancesco, H.; Dudley, J.; Coca, A. Boron chemistry: an overview. Boron reagents in synthesis 2016, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ooyama, Y.; Furue, K.; Uenaka, K.; Ohshita, J. Development of highly-sensitive fluorescence PET (photo-induced electron transfer) sensor for water: Anthracene–boronic acid ester. RSC Advances 2014, 4, 25330–25333. [Google Scholar]

- Ooyama, Y.; Matsugasako, A.; Oka, K.; Nagano, T.; Sumomogi, M.; Komaguchi, K.; Imae, I.; Harima, Y. Fluorescence PET (photo-induced electron transfer) sensors for water based on anthracene–boronic acid ester. Chemical Communications 2011, 47, 4448–4450. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, C.; Srikun, D.; Lim, C.S.; Chang, C.J.; Cho, B.R. A two-photon fluorescent probe for ratiometric imaging of hydrogen peroxide in live tissue. Chemical Communications 2011, 47, 9618–9620. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, H.; An, Q.; Sugihara, F.; Doura, T.; Tsuchiya, A.; Yoshioka, Y.; Sando, S. Phenylboronic Acid-based 19F MRI Probe for the Detection and Imaging of Hydrogen Peroxide Utilizing Its Large Chemical-Shift Change. analytical sciences 2015, 31, 331–335. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Fang, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, A.; Sun, J.; Wu, Z. Boronic acid-based enzyme inhibitors: a review of recent progress. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 21, 3271–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Luo, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z. A glucose-sensitive block glycopolymer hydrogel based on dynamic boronic ester bonds for insulin delivery. Carbohydrate research 2017, 445, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Kaur, G.; Wang, B. Progress in boronic acid-based fluorescent glucose sensors. Journal of Fluorescence 2004, 14, 481–489. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M.-H.; Chang, C.-N. Synthesis of three fluorescent boronic acid sensors for tumor marker Sialyl Lewis X in cancer diagnosis. Tetrahedron Letters 2014, 55, 4437–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, K.; Liu, Z.L.; Weston, B.; Wang, B. Fluorescent conjugate of sLex-selective bisboronic acid for imaging application. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 2013, 23, 6307–6309. [Google Scholar]

- George, K.M.; Chatterjee, D.; Gunawardana, G.; Welty, D.; Hayman, J.; Lee, R.; Small, P.L. Mycolactone: a polyketide toxin from Mycobacterium ulcerans required for virulence. Science 1999, 283, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demangel, C.; Stinear, T.P.; Cole, S.T. Buruli ulcer: reductive evolution enhances pathogenicity of Mycobacterium ulcerans. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009, 7. [Google Scholar]

- George, K.M.; Pascopella, L.; Welty, D.M.; Small, P.L. A Mycobacterium ulcerans toxin, mycolactone, causes apoptosis in guinea pig ulcers and tissue culture cells. Infect Immun 2000, 68, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherr, N.; Gersbach, P.; Dangy, J.P.; Bomio, C.; Li, J.; Altmann, K.H.; Pluschke, G. Structure-activity relationship studies on the macrolide exotoxin mycolactone of Mycobacterium ulcerans. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013, 7, e2143. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Auret, S.; Chany, A.C.; Casarotto, V.; Tresse, C.; Parmentier, L.; Abdelkafi, H.; Blanchard, N. Total Syntheses of Mycolactone A/B and its Analogues for the Exploration of the Biology of Buruli Ulcer. Chimia (Aarau) 2017, 71, 836–840. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.; Coutanceau, E.; Leclerc, M.; Caleechurn, L.; Leadlay, P.F.; Demangel, C. Mycolactone diffuses from Mycobacterium ulcerans–infected tissues and targets mononuclear cells in peripheral blood and lymphoid organs. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2008, 2, e325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfo, F.S.; Phillips, R.O.; Rangers, B.; Mahrous, E.A.; Lee, R.E.; Tarelli, E.; Asiedu, K.B.; Small, P.L.; Wansbrough-Jones, M.H. Detection of Mycolactone A/B in Mycobacterium ulcerans-Infected Human Tissue. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010, 4, e577. [Google Scholar]

- Akolgo, G.A.; Partridge, B.M.; D. Craggs, T.; Amewu, R.K. Alternative boronic acids in the detection of Mycolactone A/B using the thin layer chromatography (f-TLC) method for diagnosis of Buruli ulcer. BMC Infectious Diseases 2023, 23, 495. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, T.; Kishi, Y. Highly sensitive, operationally simple, cost/time effective detection of the mycolactones from the human pathogen Mycobacterium ulcerans. Chemical communications 2010, 46, 1410–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Kishi, Y. Chemistry of mycolactones, the causative toxins of Buruli ulcer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 6703–6708. [Google Scholar]

- Converse, P.J.; Xing, Y.; Kim, K.H.; Tyagi, S.; Li, S.Y.; Almeida, D.V.; Nuermberger, E.L.; Grosset, J.H.; Kishi, Y. Accelerated detection of mycolactone production and response to antibiotic treatment in a mouse model of Mycobacterium ulcerans disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014, 8, e2618. [Google Scholar]

- Amewu, R.K.; Akolgo, G.A.; Asare, M.E.; Abdulai, Z.; Ablordey, A.S.; Asiedu, K. Evaluation of the fluorescent-thin layer chromatography (f-TLC) for the diagnosis of Buruli ulcer disease in Ghana. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0270235. [Google Scholar]

- Wadagni, A.; Frimpong, M.; Phanzu, D.M. Simple, rapid Mycobacterium ulcerans disease diagnosis from clinical samples by fluorescence of mycolactone on thin layer chromatography. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Lin, W.; Yang, Y.; Chen, H. A unique class of near-infrared functional fluorescent dyes with carboxylic-acid-modulated fluorescence ON/OFF switching: rational design, synthesis, optical properties, theoretical calculations, and applications for fluorescence imaging in living animals. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.-F.; Guo, X.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-B. Development of a novel rhodamine-type fluorescent probe to determine peroxynitrite. Talanta 2002, 57, 883–890. [Google Scholar]

- Lavis, L.D.; Raines, R.T. Bright building blocks for chemical biology. ACS chemical biology 2014, 9, 855–866. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Program for empirical absorption correction of area detector data. SADABS 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, L.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Stalke, D. Comparison of silver and molybdenum microfocus X-ray sources for single-crystal structure determination. Journal of applied crystallography 2015, 48, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Blessing, R.H. An empirical correction for absorption anisotropy. Acta Crystallographica Section A: Foundations of Crystallography 1995, 51, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. SHELXT - Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallographica Section A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallographica Section C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov, O.; Bourhis, L.; Gildea, R.; Howard, J.; Puschmann, H. _journal_name_full'American Mineralogist'_journal_year 2021 _journal_volume 106 _journal_page_first 1844 _journal_paper_doi 10.2138/am-2021-7785. J. Appl. Cryst 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama, T.; Murata, M.; Miyaura, N. Palladium(0)-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reaction of Alkoxydiboron with Haloarenes: A Direct Procedure for Arylboronic Esters. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 1995, 60, 7508–7510. [Google Scholar]

- Akgun, B. Boronic Esters as Bioorthogonal Probes in Site-Selective Labeling of Proteins. 2018.

- Ear, A.; Amand, S.; Blanchard, F.; Blond, A.; Dubost, L.; Buisson, D.; Nay, B. Direct biosynthetic cyclization of a distorted paracyclophane highlighted by double isotopic labelling of l-tyrosine. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2015, 13, 3662–3666. [Google Scholar]

- Promchat, A.; Wongravee, K.; Sukwattanasinitt, M.; Praneenararat, T. Rapid Discovery and Structure-Property Relationships of Metal-Ion Fluorescent Sensors via Macroarray Synthesis. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 10390. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson-Wood, K.; Upstone, S.; Evans, K. Determination of Relative Fluorescence Quantum Yields using the FL6500 Fluorescence Spectrometer. Fluoresc. Spectrosc 2018, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Würth, C.; Grabolle, M.; Pauli, J.; Spieles, M.; Resch-Genger, U. Relative and absolute determination of fluorescence quantum yields of transparent samples. Nature protocols 2013, 8, 1535–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, A.M. Standards for photoluminescence quantum yield measurements in solution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry 2011, 83, 2213–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velapoldi, R.A.; Mielenz, K. A Fluorescence Standard Reference Material, Quinine Sulfate Dihydrate; US Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards: 1980.

- Herráez, J.V.; Belda, R. Refractive Indices, Densities and Excess Molar Volumes of Monoalcohols + Water. Journal of Solution Chemistry 2006, 35, 1315–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama, T.; Murata, M.; Miyaura, N. Palladium (0)-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of alkoxydiboron with haloarenes: a direct procedure for arylboronic esters. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 1995, 60, 7508–7510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiyama, T.; Itoh, Y.; Kitano, T.; Miyaura, N. Synthesis of arylboronates via the palladium (0)-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of tetra (alkoxo) diborons with aryl triflates. Tetrahedron letters 1997, 38, 3447–3450. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama, T.; Ishida, K.; Miyaura, N. Synthesis of pinacol arylboronates via cross-coupling reaction of bis (pinacolato) diboron with chloroarenes catalyzed by palladium (0)–tricyclohexylphosphine complexes. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 9813–9816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Shen, J.; Bi, C.; Zhou, H. Coumarin-based Hg2+ fluorescent probe: Synthesis and turn-on fluorescence detection in neat aqueous solution. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2017, 243, 678–683. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, B.-j.; Li, Q.; Li, C.-r.; Yang, Z.-y. A highly selective and sensitive coumarin derived fluorescent probe for detecting Hg2+ in 100% aqueous solutions. Journal of Luminescence 2019, 205, 446–450. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Wang, K.-N.; Xing, M.; Feng, F.; Pan, Q.; Cao, D. A coumarin-boronic ester derivative as fluorescent chemosensor for detecting H2O2 in living cells. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2021, 124, 108414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zhang, M.; Yan, X.; Zhang, R.; He, X.; Yuan, Y. A Coumarin-boronic Based Fluorescent “ON-OFF” Probe for Hg2+ in Aqueous Solution. Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie 2020, 646, 1892–1899. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Hu, Y.; Hou, H.-N.; Yang, W.-N.; Hu, S.-L. A new coumarin-carbonothioate-based turn-on fluorescent chemodosimeter for selective detection of Hg2+. Inorganica Chimica Acta 2018, 471, 705–708. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, M.; Hijazi, A.; Graff, B.; Fouassier, J.-P.; Rodeghiero, G.; Gualandi, A.; Dumur, F.; Cozzi, P.G.; Lalevée, J. Coumarin derivatives as versatile photoinitiators for 3D printing, polymerization in water and photocomposite synthesis. Polymer Chemistry 2019, 10, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, T.; Su, W.; Ma, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, H. Functionalized coumarin derivatives containing aromatic-imidazole unit as organic luminescent materials. Dyes and Pigments 2020, 173, 107958. [Google Scholar]

- Klinck, R.; Stothers, J. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies: Part I. The Chemical Shift of the Formyl Proton in Aromatic Aldehydes. Canadian Journal of Chemistry 1962, 40, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, H.; Sun, Q.; Tian, H.; Qian, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W. A Long-Wavelength Fluorescent Probe for Saccharides Based on Boronic-Acid Receptor. Chinese Journal of Chemistry 2013, 31, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Akgun, B.; Hall, D.G. Fast and Tight Boronate Formation for Click Bioorthogonal Conjugation. Angewandte Chemie 2016, 128, 3977–3981. [Google Scholar]

- Moriya, T. Excited-state reactions of coumarins. VII. The solvent-dependent fluorescence of 7-hydroxycoumarins. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan 1988, 61, 1873–1886. [Google Scholar]

- Aaron, J.-J.; Buna, M.; Parkanyi, C.; Antonious, M.S.; Tine, A.; Cisse, L. Quantitative treatment of the effect of solvent on the electronic absorption and fluorescence spectra of substituted coumarins: Evaluation of the first excited singlet-state dipole moments. Journal of fluorescence 1995, 5, 337–347. [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy, S.; Wu, P.-Y.; Wu, S.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Tzou, S.-C.; Wang, C.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Wang, Y.-M. In vitro and in vivo imaging of peroxynitrite by a ratiometric boronate-based fluorescent probe. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2017, 91, 849–856. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, P.; Liu, X.; Fu, J.; Xue, K.; Xu, K. Novel enantioselective fluorescent sensors for tartrate anion based on acridinezswsxa. Luminescence 2017, 32, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, P. Acridine-based complex as amino acid anion fluorescent sensor in aqueous solution. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2016, 157, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Fu, J.; Yao, K.; Xue, K.; Xu, K.; Pang, X. Acridine-based fluorescence chemosensors for selective sensing of Fe3+ and Ni2+ ions. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2018, 199, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Turan-Zitouni, G.; Kaplancikli, Z.; Uçucu, Ü.; Özdemir, A.; Chevallet, P.; Tunali, Y. Synthesis of some 2-[(benzazole-2-yl) thio]-diphenylmethylacetamide derivatives and their antimicrobial activity. Phosphorus, Sulfur, and Silicon 2004, 179, 2183–2188. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplancikli, Z.A.; Turan-Zitouni, G.; Revial, G.; Guven, K. Synthesis and study of antibacterial and antifungal activities of novel 2-[[(benzoxazole/benzimidazole-2-yl) sulfanyl] acetylamino] thiazoles. Archives of pharmacal research 2004, 27, 1081–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Demir Özkay, Ü.; Özkay, Y.; Can, Ö.D. Synthesis and analgesic effects of 2-(2-carboxyphenylsulfanyl)-N-(4-substitutedphenyl) acetamide derivatives. Medicinal Chemistry Research 2011, 20, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewska, A.; Pohl, R.; Brázdová, M.; Fojta, M.; Hocek, M. Chloroacetamide-Linked Nucleotides and DNA for Cross-Linking with Peptides and Proteins. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2016, 27, 2089–2094. [Google Scholar]

- Czaplinska, B.; Spaczynska, E.; Musiol, R. Quinoline fluorescent probes for zinc–from diagnostic to therapeutic molecules in treating neurodegenerative diseases. Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 14, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, K.A.P.; Lima, F.M.R.; Monteiro, T.O.; Silva, S.M.; Goulart, M.O.F.; Damos, F.S.; Luz, R.d.C.S. Amperometric Photosensor Based on Acridine Orange/TiO 2 for Chlorogenic Acid Determination in Food Samples. Food Analytical Methods 2018, 11, 2731–2741. [Google Scholar]

- López-Soria, J.M.; Pérez, S.J.; Hernández, J.N.; Ramírez, M.A.; Martín, V.S.; Padrón, J.I. A practical, catalytic and selective deprotection of a Boc group in N,N′-diprotected amines using iron(iii)-catalysis. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 6647–6651. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.; Tamaki, M.; Hruby, V. Fast, efficient and selective deprotection of the tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) group using HCl/dioxane (4 m). The Journal of Peptide Research 2001, 58, 338–341. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.; Tamaki, M.; Hruby, V. Fast, efficient and selective deprotection of the tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) group using HCL/dioxane (4 M). The journal of peptide research : official journal of the American Peptide Society 2001, 58, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Magid, A.F.; Carson, K.G.; Harris, B.D.; Maryanoff, C.A.; Shah, R.D. Reductive amination of aldehydes and ketones with sodium triacetoxyborohydride. studies on direct and indirect reductive amination procedures1. The Journal of organic chemistry 1996, 61, 3849–3862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.F.M.M.; Park, S.-E.; Kadi, A.A.; Kwon, Y. Fluorescein Hydrazones as Novel Nonintercalative Topoisomerase Catalytic Inhibitors with Low DNA Toxicity. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 57, 9139–9151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaschula, C.H.; Hunter, R. Synthesis and structure–activity relations in allylsulfide and isothiocyanate compounds from garlic and broccoli against in vitro cancer cell growth. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry 2016, 50, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Podhradský, D.; Drobnica, Ľ.; Kristian, P. Reactions of cysteine, its derivatives, glutathione, coenzyme A, and dihydrolipoic acid with isothiocyanates. Experientia 1979, 35, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beija, M.; Afonso, C.A.; Martinho, J.M. Synthesis and applications of Rhodamine derivatives as fluorescent probes. Chemical Society Reviews 2009, 38, 2410–2433. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.N.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, J. A new trend in rhodamine-based chemosensors: application of spirolactam ring-opening to sensing ions. Chemical Society Reviews 2008, 37, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, V.Y.; Sekiguchi, A.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, J. Biology terface. Chem. Soc. Rev 2008, 37, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Huang, W.; Duan, C.; Lin, Z.; Meng, Q. Highly sensitive fluorescent probe for selective detection of Hg2+ in DMF aqueous media. Inorganic Chemistry 2007, 46, 1538–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.-K.; Yook, K.-J.; Tae, J. A Rhodamine-Based Fluorescent and Colorimetric Chemodosimeter for the Rapid Detection of Hg2+ Ions in Aqueous Media. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2005, 127, 16760–16761. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K.; Swamy, K.; Chung, S.-Y.; Kim, H.N.; Kim, M.J.; Jeong, Y.; Yoon, J. New fluorescent and colorimetric chemosensors based on the rhodamine and boronic acid groups for the detection of Hg2+. Tetrahedron Letters 2010, 51, 3286–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Tong, A.; Jin, P.; Ju, Y. New Fluorescent Rhodamine Hydrazone Chemosensor for Cu(II) with High Selectivity and Sensitivity. Organic Letters 2006, 8, 2863–2866. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, J.; Wang, L.; Dou, W.; Tang, X.; Yan, Y.; Liu, W. Tuning the selectivity of two chemosensors to Fe (III) and Cr (III). Organic letters 2007, 9, 4567–4570. [Google Scholar]

- Bossi, M.; Belov, V.; Polyakova, S.; Hell, S.W. Reversible red fluorescent molecular switches. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2006, 45, 7462–7465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Treibs, A.; Kreuzer, F.H. Difluorboryl-komplexe von di-und tripyrrylmethenen. Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 1968, 718, 208–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ojida, A.; Sakamoto, T.; Inoue, M.-a.; Fujishima, S.-h.; Lippens, G.; Hamachi, I. Fluorescent BODIPY-based Zn (II) complex as a molecular probe for selective detection of neurofibrillary tangles in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2009, 131, 6543–6548. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.W.; Alonso, A.; Brown, C.M.; Dzyuba, S.V. Triazole-containing BODIPY dyes as novel fluorescent probes for soluble oligomers of amyloid Aβ1–42 peptide. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2010, 391, 1455–1458. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, K.E.; Szychowski, J.; Fisk, J.D.; Tirrell, D.A. A BODIPY-cyclooctyne for protein imaging in live cells. ChemBioChem 2011, 12, 2137–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Huang, W.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chou, H.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Lin, J.T.; Lin, H.-W. BODIPY dyes with β-conjugation and their applications for high-efficiency inverted small molecule solar cells. Chemical Communications 2012, 48, 8913–8915. [Google Scholar]

- Altan Bozdemir, O.; Erbas-Cakmak, S.; Ekiz, O.O.; Dana, A.; Akkaya, E.U. Towards unimolecular luminescent solar concentrators: BODIPY-based dendritic energy-transfer cascade with panchromatic absorption and monochromatized emission. Angewandte Chemie 2011, 123, 11099–11104. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, T.; Cravino, A.; Ripaud, E.; Leriche, P.; Rihn, S.; De Nicola, A.; Ziessel, R.; Roncali, J. A tailored hybrid BODIPY–oligothiophene donor for molecular bulk heterojunction solar cells with improved performances. Chemical communications 2010, 46, 5082–5084. [Google Scholar]

- Karolin, J.; Johansson, L.B.-A.; Strandberg, L.; Ny, T. Fluorescence and absorption spectroscopic properties of dipyrrometheneboron difluoride (BODIPY) derivatives in liquids, lipid membranes, and proteins. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1994, 116, 7801–7806. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmannsberger, M.; Gareis, T.; Heinl, S.; Daub, J.; Breu, J. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence and Proton-Dependent Switching of Fluorescence: Functionalized Difluoroboradiaza-s-indacenes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 1997, 36, 1333–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Loudet, A.; Burgess, K. BODIPY dyes and their derivatives: syntheses and spectroscopic properties. Chemical reviews 2007, 107, 4891–4932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, G.; Ziessel, R.; Harriman, A. The chemistry of fluorescent bodipy dyes: versatility unsurpassed. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2008, 47, 1184–1201. [Google Scholar]

- Boens, N.; Leen, V.; Dehaen, W. Fluorescent indicators based on BODIPY. Chemical Society Reviews 2012, 41, 1130–1172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Biagiotti, G.; Purić, E.; Urbančič, I.; Krišelj, A.; Weiss, M.; Mravljak, J.; Gellini, C.; Lay, L.; Chiodo, F.; Anderluh, M. Combining cross-coupling reaction and Knoevenagel condensation in the synthesis of glyco-BODIPY probes for DC-SIGN super-resolution bioimaging. Bioorganic Chemistry 2021, 109, 104730. [Google Scholar]

- Mahato, P.; Saha, S.; Das, P.; Agarwalla, H.; Das, A. An overview of the recent developments on Hg 2+ recognition. RSC Advances 2014, 4, 36140–36174. [Google Scholar]

- Bartelmess, J.; De Luca, E.; Signorelli, A.; Baldrighi, M.; Becce, M.; Brescia, R.; Nardone, V.; Parisini, E.; Echegoyen, L.; Pompa, P.P. Boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) functionalized carbon nano-onions for high resolution cellular imaging. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 13761–13769. [Google Scholar]

- Brückner, C.; Karunaratne, V.; Rettig, S.J.; Dolphin, D. Synthesis of meso-phenyl-4, 6-dipyrrins, preparation of their Cu (II), Ni (II), and Zn (II) chelates, and structural characterization of bis [meso-phenyl-4, 6-dipyrrinato] Ni (II). Canadian journal of chemistry 1996, 74, 2182–2193. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, M.; Thangaraj, K.; Soong, M.L.; Wolford, L.T.; Boyer, J.H.; Politzer, I.R.; Pavlopoulos, T.G. Pyrromethene–BF2 complexes as laser dyes: 1. Heteroatom Chemistry 1990, 1, 389–399. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, L.P.; Dzyuba, S.V. Expeditious, mechanochemical synthesis of BODIPY dyes. Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 2013, 9, 786–790. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H.; Weaver, C. The preparation of some azo boronic acids. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1948, 70, 232–234. [Google Scholar]

- Smoum, R.; Srebnik, M. Boronated saccharides: potential applications. Studies in Inorganic Chemistry 2005, 22, 391. [Google Scholar]

- Egawa, Y.; Miki, R.; Seki, T. Colorimetric sugar sensing using boronic acid-substituted azobenzenes. Materials 2014, 7, 1201–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, J.S.; Christensen, J.B.; Petersen, J.F.; Hoeg-Jensen, T.; Norrild, J.C. Arylboronic acids: A diabetic eye on glucose sensing. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2012, 161, 45–79. [Google Scholar]

- DiCesare, N.; Lakowicz, J.R. Spectral Properties of Fluorophores Combining the Boronic Acid Group with Electron Donor or Withdrawing Groups. Implication in the Development of Fluorescence Probes for Saccharides. J Phys Chem A 2001, 105, 6834–6840. [Google Scholar]

- Beda, N.; Nedospasov, A. A spectrophotometric assay for nitrate in an excess of nitrite. Nitric Oxide 2005, 13, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinan, R.; Al-Uzri, W.A. Spectrophotometric Method for Determination of Sulfamethoxazole in Pharmaceutical Preparations by Diazotization-Coupling Reaction. Al-Nahrain Journal of Science 2011, 14, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, P.F.; Gregory, P. Organic chemistry in colour; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dhami, S.; Mello, A.d.; Rumbles, G.; Bishop, S.; Phillips, D.; Beeby, A. Phthalocyanine fluorescence at high concentration: dimers or reabsorption effect? Photochemistry and Photobiology 1995, 61, 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Resch-Genger, U.; Grabolle, M.; Cavaliere-Jaricot, S.; Nitschke, R.; Nann, T. Quantum dots versus organic dyes as fluorescent labels. Nature Methods 2008, 5, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cavazos-Elizondo, D.; Aguirre-Soto, A. Photophysical Properties of Fluorescent Labels: A Meta-Analysis to Guide Probe Selection Amidst Challenges with Available Data. Analysis & Sensing 2022, 2, e202200004. [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz, J.R. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy; Springer, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, B.; Poole, C.F.; Weins, C. Quantitative thin-layer chromatography: a practical survey; Springer Science & Business Media, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomazzo, G.E.; Palladino, P.; Gellini, C.; Salerno, G.; Baldoneschi, V.; Feis, A.; Scarano, S.; Minunni, M.; Richichi, B. A straightforward synthesis of phenyl boronic acid (PBA) containing BODIPY dyes: new functional and modular fluorescent tools for the tethering of the glycan domain of antibodies. RSC advances 2019, 9, 30773–30777. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Isak, S.J.; Eyring, E.M.; Spikes, J.D.; Meekins, P.A. Direct blue dye solutions: photo properties. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2000, 134, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dinçalp, H.; Toker, F.; Durucasu, İ.; Avcıbaşı, N.; Icli, S. New thiophene-based azo ligands containing azo methine group in the main chain for the determination of copper(II) ions. Dyes and Pigments 2007, 75, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, H.; Kamounah, F.S.; Gooijer, C.; van der Zwan, G.; Antonov, L. Excited state intramolecular proton transfer in some tautomeric azo dyes and schiff bases containing an intramolecular hydrogen bond. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2002, 152, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, M.; Mokbel, H.; Graff, B.; Toufaily, J.; Hamieh, T.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Mono vs. difunctional coumarin as photoinitiators in photocomposite synthesis and 3D printing. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, M.; Graff, B.; Toufaily, J.; Hamieh, T.; Noirbent, G.; Gigmes, D.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. 3-Carboxylic Acid and Formyl-Derived Coumarins as Photoinitiators in Photo-Oxidation or Photo-Reduction Processes for Photopolymerization upon Visible Light: Photocomposite Synthesis and 3D Printing Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Dufort, B.; Iten, R.; Tibbitt, M.W. Linking molecular behavior to macroscopic properties in ideal dynamic covalent networks. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2020, 142, 15371–15385. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Fang, H.; Wang, B. Boronolectins and fluorescent boronolectins: An examination of the detailed chemistry issues important for the design. Medicinal research reviews 2005, 25, 490–520. [Google Scholar]

| Dye | MW [gmol-1] | Solvent | λabsmax [nm] | λemmax [nm] | Stokes Shift (∆λ) [nm] | ε [M-1cm-1] | Quantum yield (ΦF) | Brightness[M-1cm-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 391.2 | EtOH | 456 | 590 | 134 | 52816.1 | 0.78 | 41196.6 |

| 22 | 310.1 | DMSO | 403 | 448 | 45 | 247.6 | 0.24 | 59.4 |

| 24 | 385.2 | MeOH | 248.5 | 429 | 180.5 | ND | ND | |

| 29 | 335.2 | DMSO | 318 | 405 | 87 | 6468.8 | 0.031 | 200.5 |

| 36 | 478.3 | EtOH | 301 | 347 | 46 | 21486.3 | ND | |

| 37 | 526.3 | EtOH | 480 | 525 | 45 | 9368.7 | 0.47 | 4403.3 |

| 39 | 588.5 | EtOH | 540 | 569 | 29 | 296.5 | 0.48 | 142.3 |

| 45 | 368.0 | EtOH | 496 | 508 | 12 | 29259.1 | 0.70 | 20481.4 |

| 47a | 390.2 | EtOH | 464 | - | - | 21695.7 | ND | |

| 47b | 389.2 | EtOH | 416 | - | - | 20550.8 | ND | |

| 47c | 389.2 | EtOH | 398 | - | - | 27245.4 | ND | |

| 48 | 382.2 | MeOH | 335 | 384 | 49 | ND | ND | |

| BA | 172.0 | MeOH | 275 | 328 | 53 | ND | ND | |

| BA18 | 362.2 | MeOH | 270 | 333 | 63 | ND | ND |

| Integrated Fluorescence Intensity | ||

|---|---|---|

| Absorbance @ 499 nm | 7 | Rhodamine B |

| 0.020 | 2619195.0 | 2549829.2 |

| 0.016 | 2158588.5 | 2121340.3 |

| 0.012 | 1682211.2 | 1495319.2 |

| 0.009 | 1204913.3 | 1066673.4 |

| 0.004 | 591676.7 | 415287.3 |

| Slope | 128197000.0 | 115445000.0 |

| Absorbance @ 358 nm | 22 | Quinine sulfate |

| 0.072 | 2384944.0 | 9169983.2 |

| 0.058 | 2080661.1 | 7757302.9 |

| 0.051 | 1560798.8 | 6858240.1 |

| 0.038 | 1032764.1 | 5131493.2 |

| 0.028 | 510273.4 | 3945263.9 |

| Slope | 43905200.0 | 120830000.0 |

| Absorbance @ 332 nm | 29 | Quinine sulfate |

| 0.080 | 406256.1 | 10254500.0 |

| 0.066 | 331390.9 | 8717544.0 |

| 0.053 | 269142.8 | 7633669.7 |

| 0.040 | 195980.9 | 5868201.1 |

| 0.030 | 134100.4 | 4435606.5 |

| Slope | 5383876.6 | 114494000.0 |

| Absorbance @ 502.5 nm | 37 | Rhodamine B |

| 0.023 | 2014294.3 | 2863728.4 |

| 0.020 | 1785124.7 | 2380927.6 |

| 0.014 | 1300128.5 | 1745938.7 |

| 0.010 | 942578.1 | 1216051.1 |

| 0.005 | 455519.6 | 489246.6 |

| Slope | 861649000.0 | 128111000.0 |

| Absorbance @ 544.5 nm | 39 | Rhodamine B |

| 0.078 | 6696547.2 | 8871962.3 |

| 0.064 | 6251111.1 | 7476185.8 |

| 0.048 | 4931408.8 | 5593976.4 |

| 0.032 | 3405442.5 | 3872951.0 |

| 0.017 | 1858555.0 | 1555633.8 |

| Slope | 81524200.0 | 118451000.0 |

| Absorbance @ 502.5 nm | 45 | Rhodamine B |

| 0.023 | 3049627.7 | 2863728.4 |

| 0.019 | 2613267.2 | 2380927.6 |

| 0.014 | 1973366.8 | 1745938.7 |

| 0.010 | 1360672.8 | 1216051.1 |

| 0.005 | 731821.0 | 489246.6 |

| Slope | 127606000.0 | 128111000.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).