Submitted:

11 April 2024

Posted:

11 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Data Arrangement

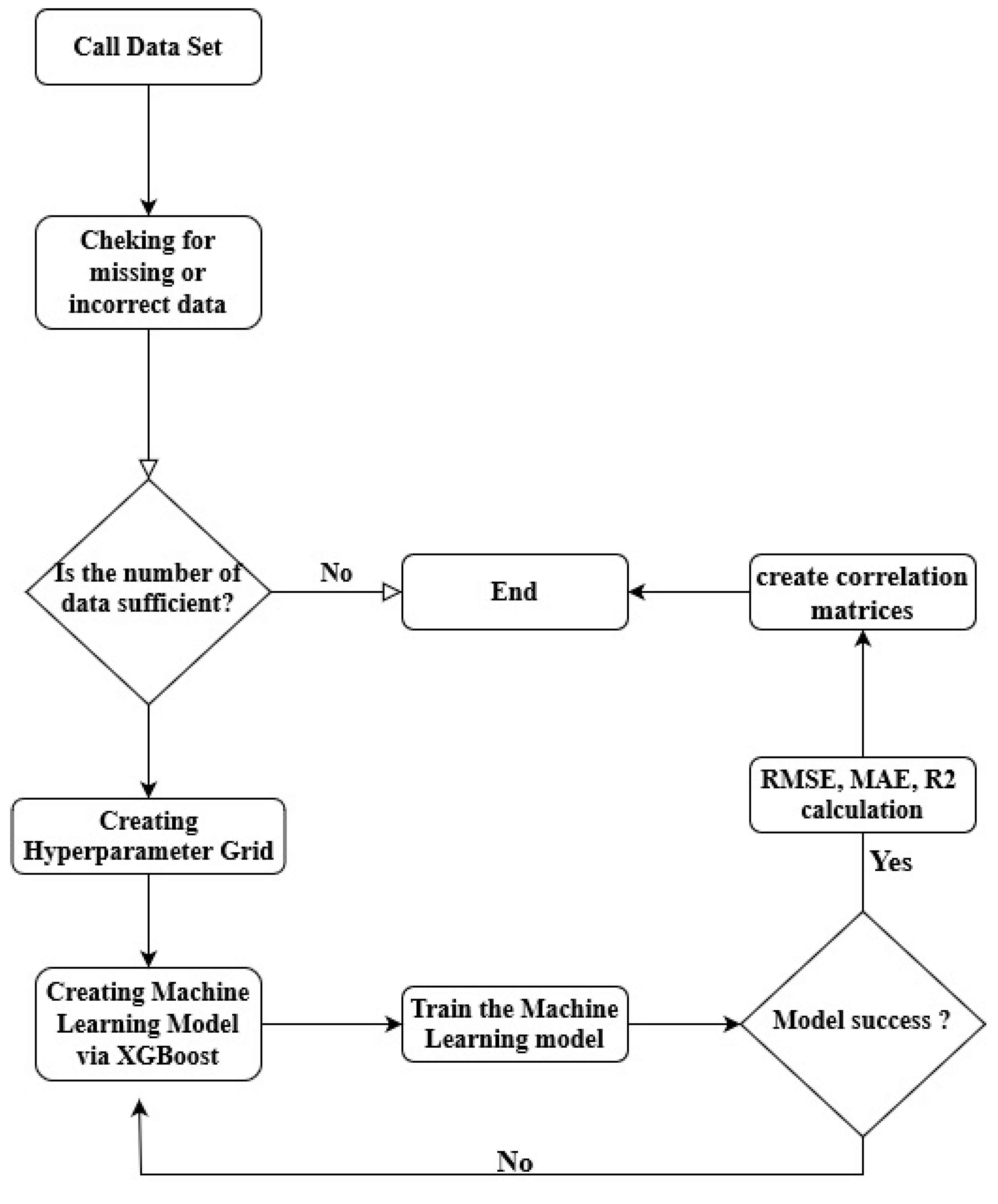

2.2. Machine Learning Algorithm

3. Results

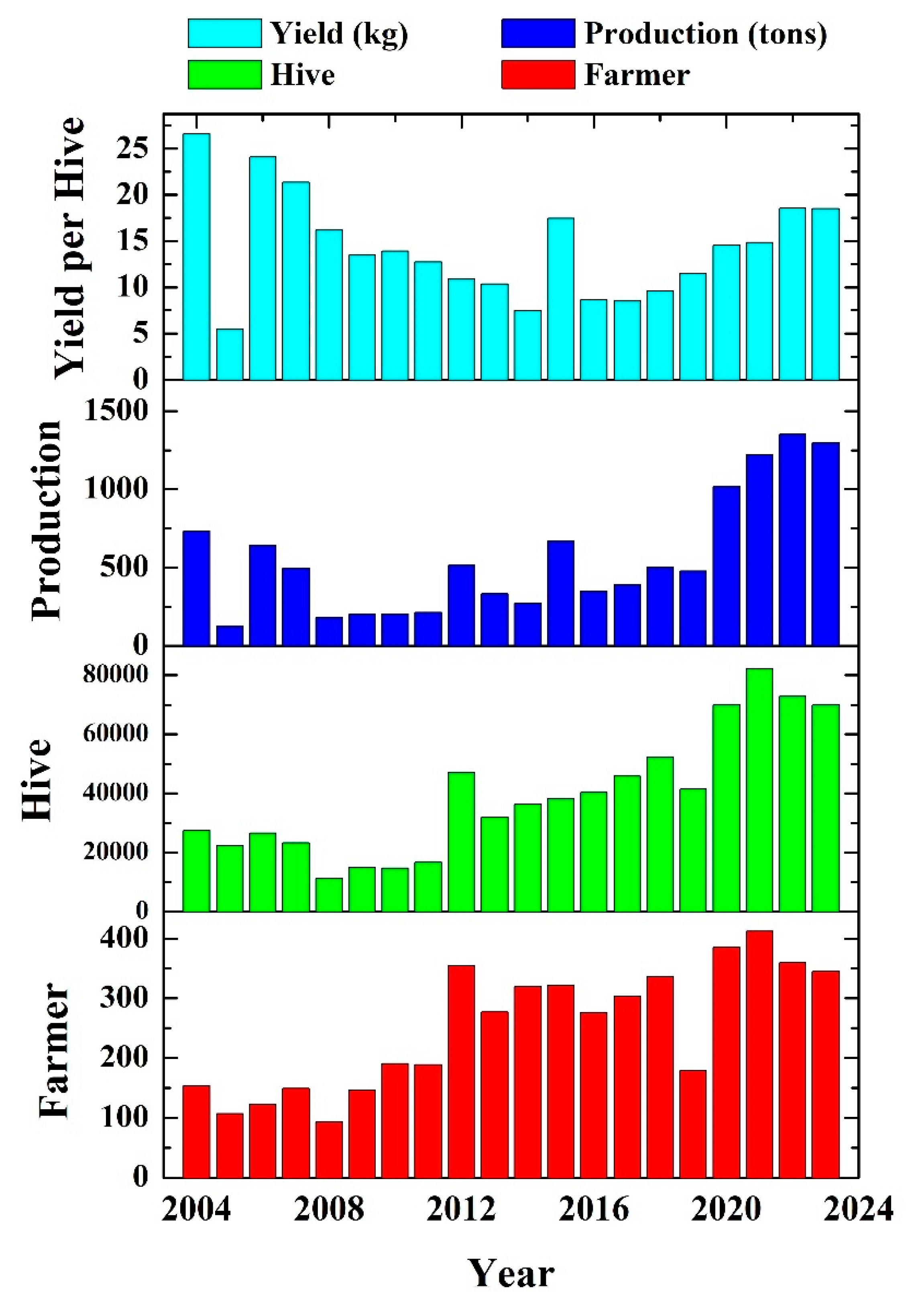

3.1. Organic Honey Production

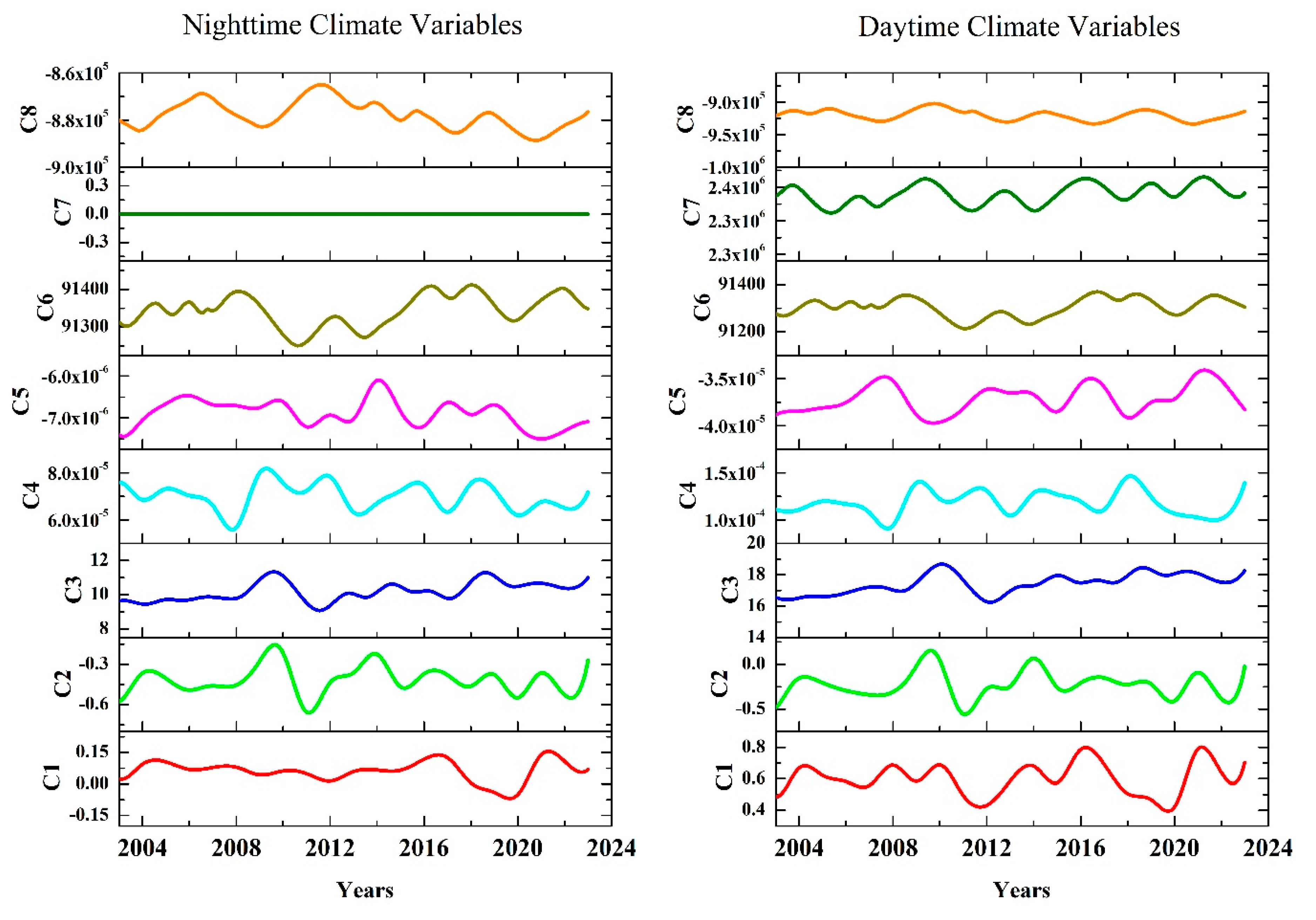

3.2. Climate Change on Türkiye

3.3. Machine Learning for Organic Honey Yield

4. Conclusions

References

- Organic beekeeping situation in turkey, Available online: https://ispecjournal.com/index.php/ispecjas/article/view/70/88 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Özkirim, A. Beekeeping in Turkey: Bridging Asia and Europe. Asian Beekeeping in the 21st Century 2018, 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanovi´c, S.; Michalczyk, M.; Oztokmak, A.; Ozmen Ozbakir, G.; Çaglar, O. Conservation of Local Honeybees (Apis Mellifera L.) in Southeastern Turkey: A Preliminary Study for Morphological Characterization and Determination of Colony Performance. Animals 2023, Vol. 13, Page 2194 2023, 13, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleskerova, Y.; Todosiichuk, V. Analysis of Economic Aspects of Organic Beekeeping Production. Green, Blue and Digital Economy Journal 2021, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdal Ertürk, Y.; Yılmaz, O. Türkiye’de Organik Arıcılık. COMU Journal of Agriculture Faculty 2013, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.R. Genetic Diversity in Turkish Honey Bees. Uludağ Arıcılık Dergisi 2002, 02, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cakirli Akyüz, N.; Theuvsen, L. Organic Agriculture in Turkey: Status, Achievements, and Shortcomings. Organic Agriculture 2021, 11, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terin, M.; Yildirim, İ.; Aksoy, A.; Sari, M.M. Agricultural Academy. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science 2018, 24, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pignagnoli, A.; Pignedoli, S.; Carpana, E.; Costa, C.; Dal Prà, A. Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions from Honey Production: Two-Year Survey in Italian Beekeeping Farms. Animals 2023, 13, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barahona, N.A.; Vergara, P.M.; Alaniz, A.J.; Carvajal, M.A.; Castro, S.A.; Quiroz, M.; Hidalgo-Corrotea, C.M.; Fierro, A. Understanding How Environmental Degradation, Microclimate, and Management Shape Honey Production across Different Spatial Scales. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2024, 31, 12257–12270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, F.; Tarazona, A.; Mateo, E.M. Comparative Study of Several Machine Learning Algorithms for Classification of Unifloral Honeys. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.L.; Zeng, L.; Gensch, T.; Sigman, M.S.; Doyle, A.G.; Anslyn, E. V. The Evolution of Data-Driven Modeling in Organic Chemistry. ACS Cent Sci 2021, 7, 1622–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davatzikos, C.; Ruparel, K.; Fan, Y.; Shen, D.G.; Acharyya, M.; Loughead, J.W.; Gur, R.C.; Langleben, D.D. Classifying Spatial Patterns of Brain Activity with Machine Learning Methods: Application to Lie Detection. Neuroimage 2005, 28, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Rong, S.; Wang, R.; Yu, S. Recent Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Nonlinear Relationship Analysis and Process Control in Drinking Water Treatment: A Review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 405, 126673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tırınk, S.; Öztürk, B. Evaluation of PM10 Concentration by Using Mars and XGBOOST Algorithms in Iğdır Province of Türkiye. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2023, 20, 5349–5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahegan, M. On the Application of Inductive Machine Learning Tools to Geographical Analysis. Geogr Anal 2000, 32, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TÜİK - Veri Portalı . Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Kategori/GetKategori?p=Tarim-111 (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Physical Location Map of Turkey, within the Entire Continent . Available online: http://www.maphill.com/turkey/location-maps/physical-map/entire-continent/ (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Lionello, P.; Abrantes, F.; Gacic, M.; Planton, S.; Trigo, R.; Ulbrich, U. The Climate of the Mediterranean Region: Research Progress and Climate Change Impacts. Reg Environ Change 2014, 14, 1679–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, T.; Ertuğrul, M.; Varol, T. Climate Change and Forest Fire Trend in the Aegean and Mediterranean Regions of Turkey.

- Bär, R.; Rouholahnedjad, E.; Rahman, K.; Abbaspour, K.C.; Lehmann, A. Climate Change and Agricultural Water Resources: A Vulnerability Assessment of the Black Sea Catchment. Environ Sci Policy 2015, 46, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doĝan, U. Fluvial Response to Climate Change during and after the Last Glacial Maximum in Central Anatolia, Turkey. Quaternary International 2010, 222, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirci, K.; Kirtiloglu, Y. Effect of Climate Change to Solar Energy Potential: A Case Study in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Turkey. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 2839–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayanç, M.; İm, U.; Doğruel, M.; Karaca, M. Climate Change in Turkey for the Last Half Century. Clim Change 2009, 94, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus . Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Gono, D.N.; Napitupulu, H. ; Firdaniza Silver Price Forecasting Using Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) Method. Mathematics 2023, Vol. 11, Page 3813 2023, 11, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoni, F.G.; Missiaggia, M.; Scifoni, E.; -, al; Yao, X. ; Shen, C.; Xu -, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Ji, Z.; et al. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) Method in Making Forecasting Application and Analysis of USD Exchange Rates against Rupiah. J Phys Conf Ser 2021, 1722, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dang, W.; Wang, F.; Nie, H.; Wei, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.; Feng, Y.; Li, F. Prediction of TOC Content in Organic-Rich Shale Using Machine Learning Algorithms: Comparative Study of Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and XGBoost. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, F.; Furqon, M.T. The Simplicity of XGBoost Algorithm versus the Complexity of Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Neural Networks Algorithms in Urban Forest Classification. F1000Research 2022 11:1069 2022, 11, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.C.; Tsai, Y.C.; Wu, P.Y.; Lien, Y.H.; Chien, C.Y.; Kuo, C.F.; Hung, J.F.; Chen, S.C.; Kuo, C.H. Predictive Modeling of Blood Pressure during Hemodialysis: A Comparison of Linear Model, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression, XGBoost, LASSO Regression and Ensemble Method. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2020, 195, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesantez-Narvaez, J.; Guillen, M.; Alcañiz, M. Predicting Motor Insurance Claims Using Telematics Data—XGBoost versus Logistic Regression. Risks 2019, Vol. 7, Page 70 2019, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okudum, R.; Şeremet, M.; Alaeddinoğlu, F. Organik Tarım Üzerinde Konvansiyonelleşme ve Kırsal Kalkınma Tartışmaları. Türk Coğrafya Dergisi. [CrossRef]

- Bischl, B.; Binder, M.; Lang, M.; Pielok, T.; Richter, J.; Coors, S.; Thomas, J.; Ullmann, T.; Becker, M.; Boulesteix, A.L.; et al. Hyperparameter Optimization: Foundations, Algorithms, Best Practices, and Open Challenges. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Data Min Knowl Discov 2023, 13, e1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yu, Z.; Qu, Y.; Xu, J.; Cao, Y. Application of the XGBoost Machine Learning Method in PM2.5 Prediction: A Case Study of Shanghai. Aerosol Air Qual Res 2020, 20, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercelli, M.; Novelli, S.; Ferrazzi, P.; Lentini, G.; Ferracini, C. A Qualitative Analysis of Beekeepers’ Perceptions and Farm Management Adaptations to the Impact of Climate Change on Honey Bees. Insects 2021, Vol. 12, Page 228 2021, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajardo-Rojas, M.; Muñoz, A.A.; Barichivich, J.; Klock-Barría, K.; Gayo, E.M.; Fontúrbel, F.E.; Olea, M.; Lucas, C.M.; Veas, C. Declining Honey Production and Beekeeper Adaptation to Climate Change in Chile. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091333221093757, 2022; 46, 737–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landaverde, R.; Rodriguez, M.T.; Parrella, J.A. Honey Production and Climate Change: Beekeepers’ Perceptions, Farm Adaptation Strategies, and Information Needs. Insects 2023, 14, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A.J.; Flay, R.G.J.; Panofsky, H.A. Vertical Coherence and Phase Delay between Wind Components in Strong Winds below 20 m. Boundary Layer Meteorol 1983, 26, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemi, T. Effects of Climate Change Variability on Agricultural Productivity. International Journal of Environmental Sciences & Natural Resources 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Conte, Y.; Navajas, M. Climate Change: Impact on Honey Bee Populations and Diseases. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz 2008, 27, 499–510. [Google Scholar]

| Hyperparameters | Values |

|---|---|

| nrounds | 500 |

| max_depth | 9 |

| eta | 0.3 |

| gamma | 0 |

| colsample_bytree | 0.9 |

| min_child_weight | 3 |

| subsample | 0.9 |

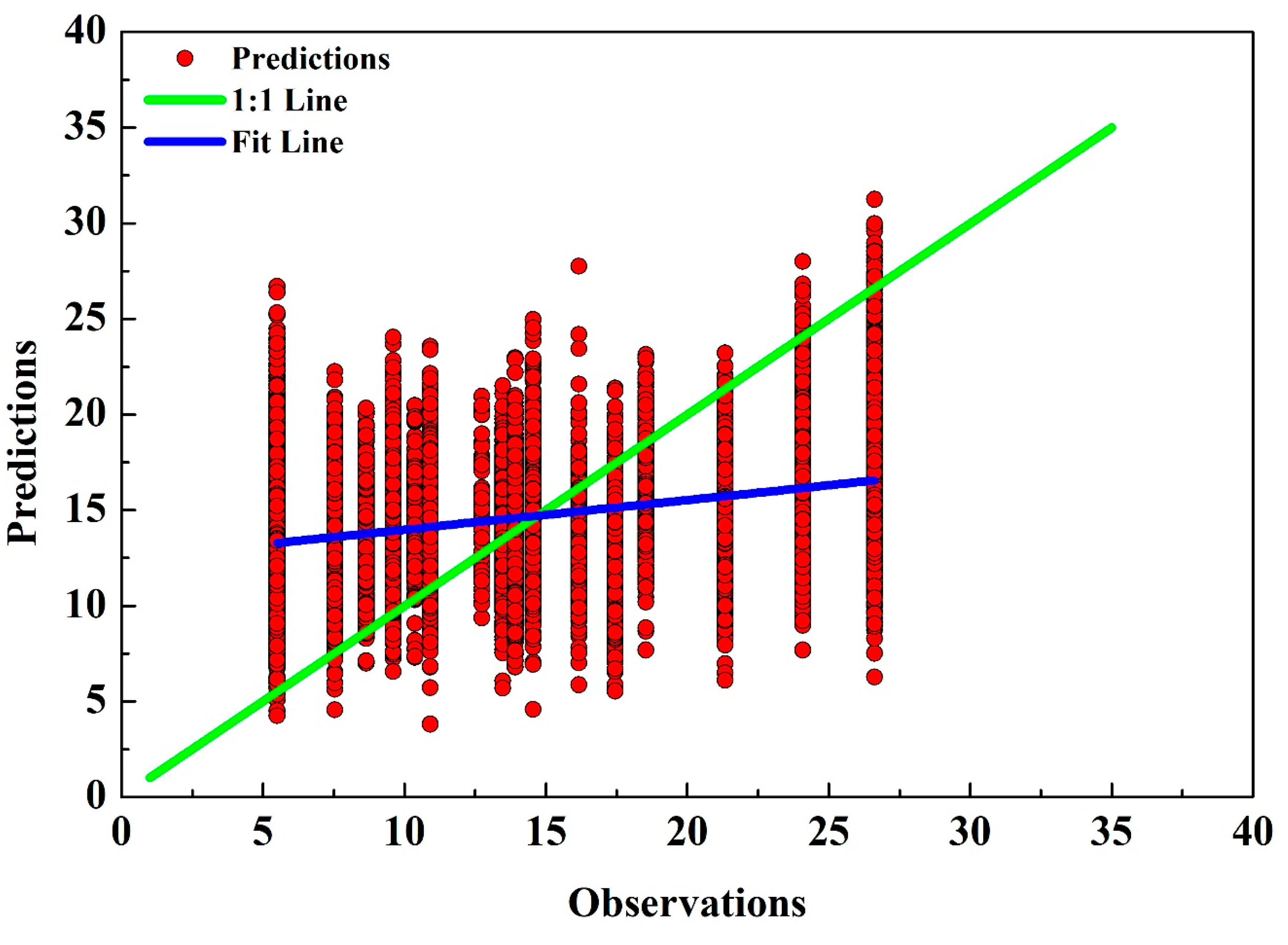

| Performance Parameters | Values |

| RMSE | 1.38317 |

| MAE | 1.03812 |

| R2 | 0.78493 |

| Importance Level | Feature | Gain | Cover | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Top solar radiation (Daytime) | 0.09059515 | 0.08744304 | 0.07077136 |

| 2 | Top thermal radiation (Daytime) | 0.08399873 | 0.08117384 | 0.06785828 |

| 3 | 2-meter temperature (Daytime) | 0.08203138 | 0.09039404 | 0.06629731 |

| 4 | Top thermal radiation (Nighttime) | 0.08199702 | 0.09630029 | 0.06948521 |

| 5 | 2-meter temperature (Nighttime) | 0.07341991 | 0.08106766 | 0.07414614 |

| 6 | 10-meter U-wind (Daytime) | 0.07337569 | 0.07362262 | 0.07587200 |

| 7 | 10-meter V-wind (Daytime) | 0.06866239 | 0.06897497 | 0.07506953 |

| 8 | 10-meter V-wind (Nighttime) | 0.06601100 | 0.07524847 | 0.07822445 |

| 9 | Humidity (Daytime) | 0.06586092 | 0.05029741 | 0.06457145 |

| 10 | Surface pressure (Nighttime) | 0.05971670 | 0.04765959 | 0.06813310 |

| 11 | Humidity (Nighttime) | 0.05883414 | 0.04883785 | 0.06471435 |

| 12 | Total precipitation (Nighttime) | 0.05749842 | 0.03658732 | 0.06279062 |

| 13 | 10-meter U-wind (Nighttime) | 0.05693347 | 0.07092535 | 0.07497059 |

| 14 | Total precipitation (Daytime) | 0.05668634 | 0.04762505 | 0.06436259 |

| 15 | Surface pressure (Daytime) | 0.02437875 | 0.04384252 | 0.02273302 |

| 16 | Top solar radiation (Nighttime) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Variable | Mean dropout loss | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Importance Level | Sensitivity Level | Full Model | 1.383171 |

| 16 | 16 | Top solar radiation (Nighttime) | 1.383171 |

| 13 | 15 | 10-meter U-wind (Nighttime) | 2.54861 |

| 8 | 14 | 10-meter V-wind (Nighttime) | 2.676877 |

| 7 | 13 | 10-meter V-wind (Daytime) | 2.800314 |

| 12 | 12 | Total precipitation (Nighttime) | 2.830632 |

| 6 | 11 | 10-meter U-wind (Daytime) | 2.848633 |

| 11 | 10 | Humidity (Nighttime) | 2.855943 |

| 9 | 9 | Humidity (Daytime) | 2.989901 |

| 14 | 8 | Total precipitation (Daytime) | 3.025835 |

| 15 | 7 | Surface pressure (Daytime) | 3.316515 |

| 10 | 6 | Surface pressure (Nighttime) | 3.481531 |

| 5 | 5 | 2-meter temperature (Nighttime) | 4.385817 |

| 2 | 4 | Top thermal radiation (Daytime) | 4.689841 |

| 3 | 3 | 2-meter temperature (Daytime) | 5.135982 |

| 1 | 2 | Top solar radiation (Daytime) | 5.470182 |

| 4 | 1 | Top thermal radiation (Nighttime) | 6.179276 |

| Base line | 6.972226 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).