1. The Fundamental Nature of Entropy: The Judgment Criterion

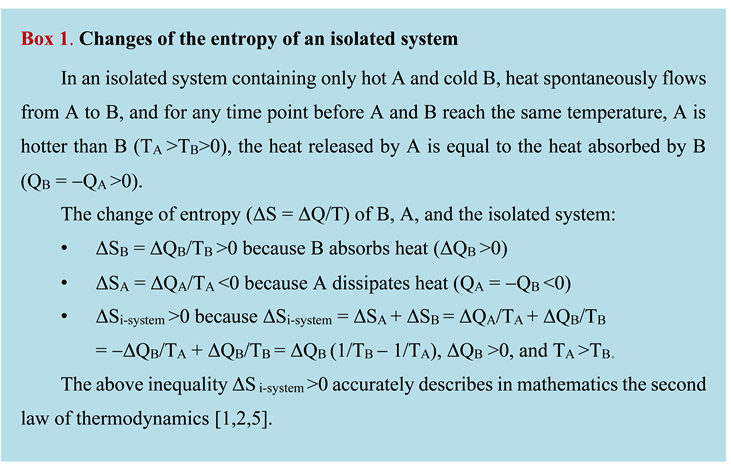

In the 1860s, Rudolf Clausius created the entropy concept (S) to mathematically describe the second law of thermodynamics (Box 1) and explain the efficiency of heat-to-work conversion in Carnot cycles [

1]. The law states that heat can spontaneously flow from a hot object to a cold object and cannot spontaneously flow reversely. The law involves two parameters, heat energy (Q), the kinetic energy of the unordered vibration of molecules in an object [

2,

3,

4] and thermodynamic temperature (T). T is higher than zero for all objects worldwide, according to the third law of thermodynamics [

2,

3,

4].

Clausius invented the Clausius formula, ΔS = ΔQ/T, which means that, at a time point, the increase in the entropy of an object (ΔS) is equal to the heat absorbed by the object (ΔQ) divided by the thermodynamic temperature of the object (T) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. This formula suggests that the entropy of an object increases when it absorbs heat from its surroundings (ΔQ>0) and declines when it dissipates heat into its surroundings (ΔQ<0), and suggests that the entropy of an isolated system always increases until its components reach the same temperature (Box 1), which accurately describes in mathematics the second law of thermodynamics [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

The Clausius formula defines the fundamental nature of entropy: entropy is a physical concept analogous to energy because entropy is heat energy divided by thermodynamic temperature [

2,

3,

4]. This aligns with Rudolf Clausius's statement: “…I have designedly coined the word ‘entropy’ to be similar to ‘energy’, for these two quantities are so analogous in their physical significance...” [

6] The fundamental nature of entropy, which is uncontroversial and pivotal in current thermodynamics [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6], is employed in this article as the criterion to judge the correctness of other notions associated with entropy.

Entropy is an additive quantity in physics. For example, the entropy of the isolated system composed of object A and object B in Box 1 is equal to the entropy of object A plus the entropy of object B [

2,

3,

4].

The increase in the entropy of an object due to heat absorption can lead to at least four types of changes, exemplified as below: a stone, metal, or ideal gas becomes hotter; ice melts into water; a solar battery gains electrical energy; and carbon dioxide, along with water, can form glucose through heat-absorbing organic synthesis (photosynthesis) in plant leaves [

7,

8]. In the first two types of changes, the increased heat or entropy of the objects remains as heat energy, which can be dissipated if the surroundings become colder. In contrast, some of the increased heat or entropy of the objects in the last two types of changes is stored as electrical energy or chemical energy, which can be stored in the objects even if the surroundings become colder

7.

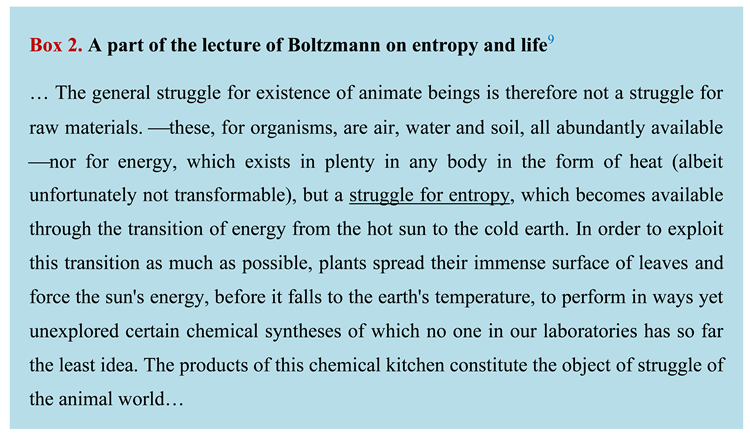

2. Boltzmann's Statement Regarding Entropy and Life

Ludwig Boltzmann stated in 1886 that animals struggle for the entropy that is transformed from the solar energy in plants (Box 2). This statement is correct according to the fundamental nature of entropy because the entropy of plants increases when they absorb heat from sunlight, and the increased entropy or energy is stored as chemical energy in carbohydrate molecules through photosynthesis (

Section 1) [

7,

8]. Animals can use the entropy or energy stored in the carbohydrate molecules in plants, which serve as animals' food, and released through the metabolic degradation of animals' food for their movement, maintenance of their body temperatures, and other purposes. Animals do not struggle for the heat energy abundant on Earth that they cannot utilize

3. The Boltzmann Formula of Entropy

In 1900, Max Planck defined entropy with the equation, S =

k Ln

W, which he termed the Boltzmann formula because the equation originated from Boltzmann's view that the second law of thermodynamics can be explained with the statistical probability associated with heat transfer [

9,

10]. In the formula, Ln represents natural logarithm,

k represents the Boltzmann constant (1.38065×10

−23 J/K), and

W is assumed to represent a probability associated with heat transfer [

9,

10].

To combine the Clausius formula and the Boltzmann formula, it can be deduced that, at a time point:

ΔS =ΔQ/T = S2 − S1 = k LnW2 − k LnW1 = k (LnW2 − LnW1) = k (ΔLnW)

ΔLnW = ΔQ/(kT)

This shows that

W is a quantity associated with heat energy and thermodynamic temperature.

W is from the German “Wahrscheinlichkeit”, which means probability [

11], However, it remains unknown what kind of probability of what kind of authentic microparticles is represented by

W. Later,

W was translated in English with the words of complexions, permutations, thermodynamic probability, or multiplicity (the count of microstates) [

11]. Here, we just need to know that these terms and the Boltzmann formula do not challenge the fundamental nature of entropy defined by the Clausius formula [

9,

10,

11]. Additionally, the calculation of the natural logarithm within the Boltzmann formula acknowledges that entropy is an additive quantity.

4. Modern Explanations of the Second Law of Thermodynamics

The Clausius formula and the Boltzmann formula were established before or in 1900, when the essence of heat transfer remained unknown. According to modern knowledge regarding the structures of atoms and molecules and electromagnetic waves, heat can be transferred through conduction (molecule collisions) in solids, convection (molecule mixing) in gases or liquids, and radiation through electromagnetic waves [

2,

4]. These three types of heat transfer explicitly explain the second law of thermodynamics and modify its expression as follows: within an isolated system, heat energy is spontaneously exchanged between a hot object and a cold object, and more heat energy is transferred from the hot object to the cold object than vice versa.

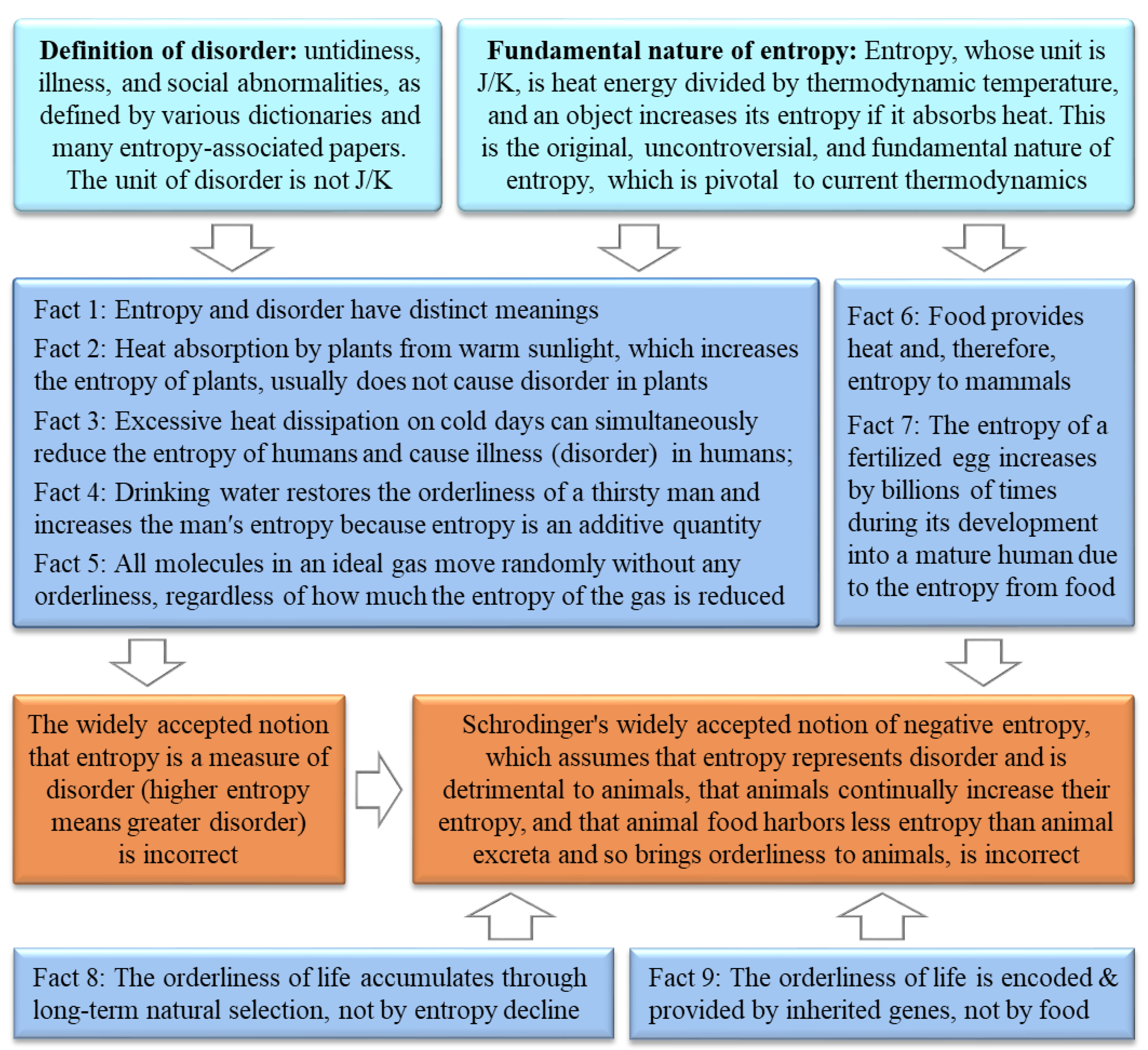

5. The notion that entropy is a measure of disorder is incorrect

In the 1880s, Hermann von Helmholtz used the word “disorder” to describe entropy, possibly from which the notion that entropy is a measure of disorder (higher entropy means greater disorder) emerged [

12]. This notion has been widely stated in various dictionaries [

13], encyclopedias [

5,

6,

14,

15], textbooks [

2,

4], and many research articles [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], although this notion has faced a few challenges [

3,

24,

25,

26,

27]. This notion can be disproved for the following reasons.

(1) Entropy and disorder have distinct meanings. According to the fundamental nature of entropy, entropy is analogous to energy with the unit of J/K [

2,

3,

4]. By contrast, according to the explanations of disorder in various Oxford dictionaries [

28], the Collins English Dictionary [

29], and some entropy-associated research articles [

16,

17,

18,

19], disorder means untidiness, illness, and social abnormalities (e.g., violence or rioting). Disorder usually stems from the decline in the orderliness of a system, and its unit cannot be J/K. Although some people argue that the “disorder” in thermodynamics means different things from the “disorder” in biology, social sciences, or usual thinking [

14], the notion that entropy represents disorder has been widely applied to investigate the “disorder” in biology and social sciences [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], as exemplified by Schrödinger's negative entropy (negentropy) notion, which will be detailed below. Moreover, what we argue is that entropy does not mean the “disorder” in biology, social sciences, or usual thinking.

(2) Heat absorption by plants from warm sunlight, which increases plants' entropy, usually does not cause disorder to plants. Therefore, entropy cannot represent disorder in plants.

(3) Excessive heat dissipation of humans on cold days can reduce their entropy and cause disorder in human bodies, i.e., insufficient entropy can increase disorder in humans. Therefore, entropy cannot represent disorder in humans.

(4) Drinking water can restore the orderliness of a thirsty man, which simultaneously increases the man's entropy because entropy is an additive quantity [

2,

3,

4]. This fact suggests that entropy cannot represent disorder in humans.

(5) No molecules in an ideal gas move in an orderly manner, regardless of how much the entropy of the gas is reduced. This suggests that entropy cannot represent disorder even in the classical system of ideal gases in thermodynamics.

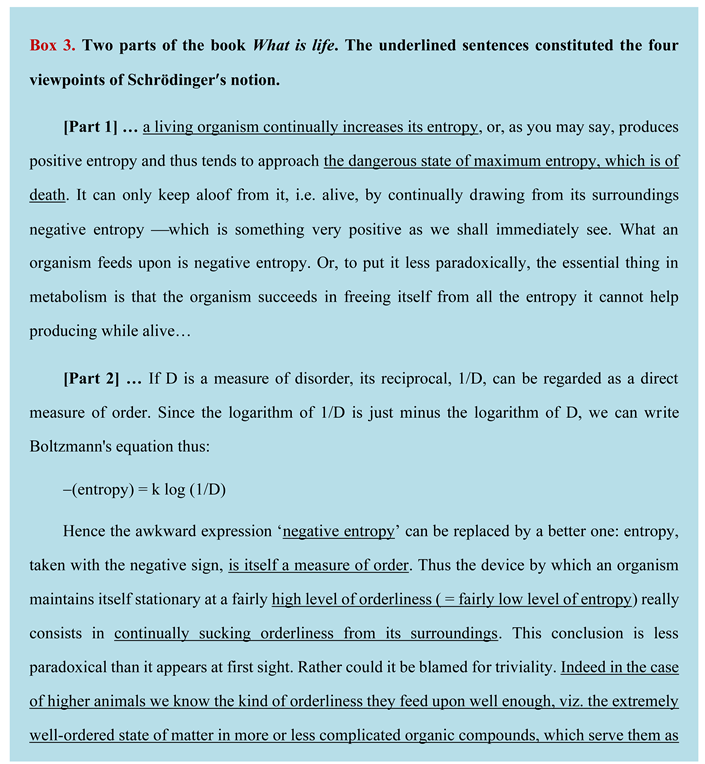

6. Schrödinger's negentropy notion is incorrect

Nobel laureate Erwin Schrödinger published in 1944 that life relies on negentropy in the famous tiny book,

What is life [

30,

31]. Schrödinger's negentropy notion, which contradicts Boltzmann's correct statement (

Section 2), is based on the incorrect notion that entropy represents disorder (

Section 5) and irrationally substitutes the quantity

W in the Boltzmann formula with disorder in its reasoning (Box 3). This notion contains four viewpoints, none of which is correct, as detailed below.

The first viewpoint that a living organism continually increases its entropy is incorrect because, according to the fundamental nature of entropy, healthy humans are consistently releasing heat to their

surroundings as their bodies are usually hotter than their surroundings, and thus they consistently reduce their entropy except when they are eating, drinking, or absorbing heat from sunlight or other warm surroundings.

The second viewpoint of Schrödinger's negentropy notion that entropy represents disorder and is thus detrimental to animals has been disproved in

Section 5.

The third viewpoint of Schrödinger's negentropy notion that animals continually obtain orderliness (negentropy) from their surroundings or from their food is incorrect because, in biology, animal lives are supported by three pillars: orderliness, constituent materials, and energy (or entropy) (

Figure 1), like the software (orderliness), hardware (constituent materials), and energy required to operate a computer. The orderliness is encoded and provided by genes inherited from parents

32, while the constituent materials and the energy are mainly from food. The orderliness of life accumulates through long-term natural selection and is neither provided by food nor suddenly emerges due to negentropy (the decrease in an organism's entropy as it dissipates entropy to its surroundings) (

Figure 1) [

32]. Furthermore, food provides humans with heat and, thus, entropy to support humans' lives with energy (

Section 2). Schrödinger's assumption that animal food contains less entropy than animal excreta is incorrect because food metabolism dissipates heat, and hence animal food contains more entropy than animal excreta. During the developmental process from a fertilized egg into a mature human, its weight and entropy increase by billions of times because entropy is an additive property, and these increases are due to the entropy derived from the food consumed by the mother or by the developing organism itself.

The fourth viewpoint of Schrödinger's negentropy notion that sunlight provides negentropy to plants is incorrect because, according to the fundamental nature of entropy, the entropy of plants, stones, ices, and other objects increases when they absorb heat from sunlight. Some of the energy or entropy absorbed by plants is stored as chemical energy in carbohydrate molecules through heat-absorbing photosynthesis [

8]. Furthermore, in biology, sunlight or any type of energy cannot directly provide orderliness to plants, and the orderliness in plants is also encoded and provided by inherited genes and accumulates through long-term natural selection [

32].

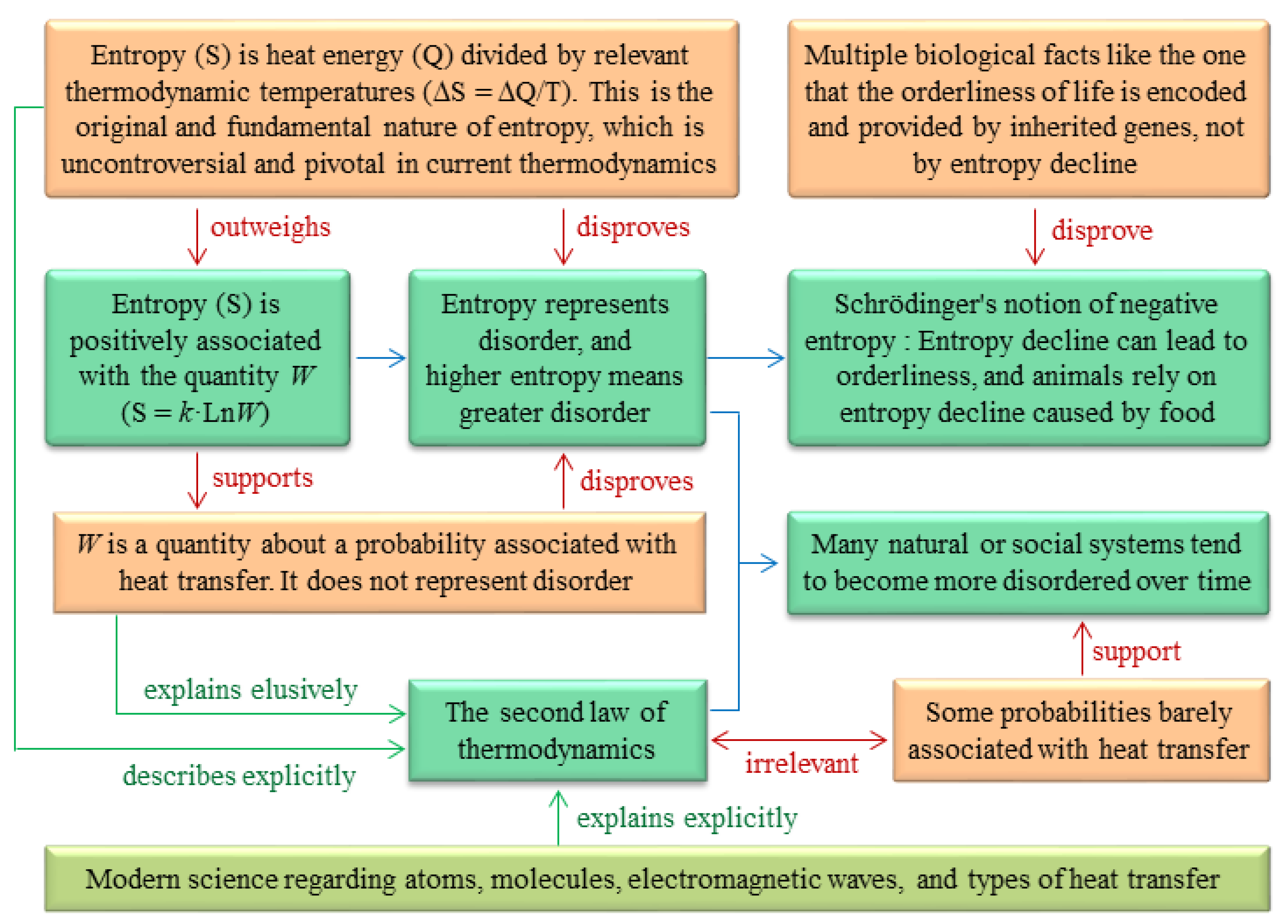

Although the four viewpoints of Schrödinger's negentropy notion are all incorrect, as explained above and shown in

Figure 2, it has garnered widespread acceptance for nearly 80 years, with only a few criticisms [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Notably, Google Scholar showed at the end of 2023 that Schrödinger's book,

What is life, had been positively cited approximately 10,000 times mainly due to the inclusion of this notion. In 2022 and 2023, this book was cited for more than 1,000 times by authors from various countries [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43], with few doubts about this notion.

Coinciding with the popularity of this notion, English Wikipedia and other academic websites deliberately added the word “negative” with brackets in Boltzmann's statement in Box 2 before “entropy” [

44,

45]. However, it is unlikely that Boltzmann neglected the word "negative" because the concept of negative entropy was coined after his death and Boltzmann's statement is correct according to the fundamental nature of entropy (

Section 2).

In recent decades, negentropy has also been employed to represent information [

46], which is also controversial [

30,

47].

7. Misuse of the second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics, which states that heat can flow spontaneously from hot objects to cold objects and cannot flow reversely, has been frequently misused. For example, it was assumed by researchers from various fields that many natural or social systems tend to become more disordered over time due to the second law of thermodynamics [

2,

4,

5,

6,

18,

19,

32,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The fact that many natural or social systems tend to become more disordered over time results from some statistical probabilities because it is more probable for these systems to stay at a disordered status than at an ordered status. However, these statistical probabilities are barely associated with heat transfer. Therefore, the fact that many natural or social systems tend to become more disordered is unrelated to the second law of thermodynamics.

Interestingly, although many natural or social systems tend to become more disordered over time due to statistical probabilities, we have explicitly explained in recent years that some principles of physics and chemistry (e.g., the second law of thermodynamics), features of the Earth, and features of carbon atoms and other carbon-based entities (e.g., organic molecules and organisms) lead to three mechanisms that have driven inanimate materials to evolve into complex organisms and societies on Earth, and the evolution demonstrates a natural tendency to increase orderliness [

48]. Some researchers also acknowledge the significance of laws of thermodynamics in the CBEP [

49].

The reasoning errors behind the two notions and some misuses of the second law of thermodynamics are given in

Figure 3.

8. Conclusions

Although the two notions disproved by this article have faced a few challenges in the past decades, the challenges, which were largely from the perspective of physics [

3,

25,

26,

27,

32,

33,

34,

50], have not gained sufficient attention. This article clarifies the original, uncontroversial, and fundamental nature of entropy, from which multiple facts in physics (e.g., ideal gases, solar batteries), chemistry (e.g., organic synthesis reactions), and biology (e.g., the roles of genes and the heat requirement of humans) are deduced. These facts constitute novel and compelling arguments to systematically disprove the two notions. Moreover, this article further clarifies the reasoning errors of the two notions. It also shows that the tendency of many natural or social systems to become more disordered over time does not result from the second law of thermodynamics.

The two notions disproved by this article have been cited hundreds of times annually in various scientific fields for decades [

3,

24,

25,

26,

27,

32,

33,

34,

50,

51], suggesting that these two notions may represent profound academic misconceptions of the 20th and 21st centuries. They have unnecessarily complicated the study of thermodynamics and have misled research on complexity, order, and evolution. The systematic refutation of these two notions in this article can expedite the eradication of their adverse effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Meng Yang for her various constructive comments. The authors also thank Yingqing Chen who contributed much to Section 3, Section 4, and figures. This work was supported by the High-Level Talent Fund of Foshan University (No. 20210036).

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Clausius, R. Über die bewegende Kraft der Wärme und die Gesetze, welche sich daraus für die Wärmelehre selbst ableiten lassen. Annalen der Physik 155, 368–397 (1850). [CrossRef]

- Borgnakke, C. & Sonntag, R.E. Fundamentals of Thermodynamics (Wiley, 2022).

-

Thermodynamics and Chemistry https://www2.chem.umd.edu/thermobook/v10-screen.pdf (DeVoe, H., accessed 27 March 2024).

- Zhang, S.H., An, Y., Ruan, D. & Li, Y.S. College Physics- Mechanics & Thermodynamics (Tsinghua University Press, 2018).

-

Entropy in physics https://www.britannica.com/science/entropy-physics (Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed 27 March 2024).

-

Entropy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/entropy (Wikipedia, accessed 27 March 2024).

- Kabo, G.J., Blokhin, A.V., Paulechka, E., et al. Thermodynamic properties of organic substances: Experiment, modeling, and technological applications. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 131, 225-246 (2019).

- Mauzerall, D. Thermodynamics of primary photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 116, 363–366 (2013). . [CrossRef]

- Boltzmann, L. The second law of thermodynamics. In Theoretical physics and philosophical problems: Select writings (ed. McGuinness, B.F.) 13−33 (Springer, 1974).

- Planck, M. Entropie und temperatur strahlender wärme. Annalen der Physik. 306, 719–737 (1900).

- Baierlein, R. Thermal Physics (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- Anderson, G.M. Thermodynamics of natural systems (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

-

Entropy https://www.oxfordreference.com/search?q=entropy (Oxford Reference, accessed 27 March 2024).

-

Entropy (order and disorder) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entropy_(order_and_disorder) (Wikipedia, accessed 27 March 2024).

-

Entropy and disorder https://www.britannica.com/science/principles-of-physical-science/Entropy-and-disorder (Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed 27 March 2024).

- Prigogine, I. Time, structure and fluctuation (Nobel Lecture). Science. 201, 777–785 (1978). . [CrossRef]

- Saxberg, B., Vrajitoarea, A., Roberts, G., Panetta, M.G., Simon, J. & Schuster, D.I. Disorder-assisted assembly of strongly correlated fluids of light. Nature. 612, 435–441 (2022). . [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.E. Cells solved the Gibbs paradox by learning to contain entropic forces. Sci. Rep. 13, 16604 (2023). . [CrossRef]

- Aristov, V.V., Karnaukhov, A.V., Buchelnikov, A.S., Levchenko, V.F. & Nechipurenko, Y.D. The degradation and aging of biological systems as a process of information loss and entropy increase. Entropy. 25(7), 1067 (2023). . [CrossRef]

- Friston, K., Da Costa, L., Sakthivadivel, D.A., Heins, C., Pavliotis, G.A., Ramstead, M. & Parr, T. Path integrals, particular kinds, and strange things. Phys. Life Rev. 47, 36–62 (2023). . [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R.C., Belgio, E. & Zucchelli, G. Photosystem I, when excited in the chlorophyll Qy absorption band, feeds on negative entropy. Biophys. Chem. 233, 36–46 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kleidon, A. Life, hierarchy, and thermodynamic machinery of planet Earth. Phys. Life Rev. 7, 424–460 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Ramstead, M.J.D., Badcock, P.B. & Friston, K.J. Answering Schrödinger's question: A free-energy formulation. Phys. Life Rev. 24, 1–16 (2018).

- Chen, J. A new evolutionary theory deduced mathematically from entropy amplification. Chin. Sci. Bull. 45, 91–96 (2000). . [CrossRef]

- Lambert, F.L. Disorder—A cracked crutch for supporting entropy discussions. J. Chem. Educ. 79, 187 (2002). . [CrossRef]

- Grandy, W.T. Entropy and the Time Evolution of Macroscopic Systems. 55–58. (Oxford University Press, 2008).

- Bejan, A. Evolution in thermodynamics. Appl Phys Rev. 4, 011305 (2017). . [CrossRef]

-

Disorder https://www.oxfordreference.com/search?q=disorder (Oxford Reference, accessed 27 March 2024).

-

Disorder https://www.collinsdictionary.com/us/dictionary/english/disorder (Collins Dictionaries, accessed 27 March 2024).

-

Negentropy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negentropy (Wikipedia, accessed 27 March 2024).

- Schrodinger, E. What is life 67−75 (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Futuyma, D.J. & Kirkpatrick, M. Evolution (Sinauer Associates, 2017).

- Moberg, C. Schrödinger's What is Life?-The 75th Anniversary of a book that inspired biology. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 2550−2553 (2020). . [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. Schrödinger's contribution to chemistry and biology. In Schrödinger. Centenary celebration of a polymath (ed. Kilmister, C.W.) 225-233 (Cambridge University Press,1987).

- Chen, J.M. & Chen J.W. Root of Science: The driving force and mechanism of the extensive evolution (Science Press, 2020).

- Roth, Y. What is life? The observer prescriptive. Results Phys. 49, 106449 (2023). . [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, K. Temporal cohesion as a candidate for negentropy in biological thermodynamics. Biosystems. 230, 104957 (2023). . [CrossRef]

- Portugali J. Schrödinger's What is Life?-Complexity, cognition and the city. Entropy (Basel). 2023;25(6):872. . [CrossRef]

- Freeland, S. Undefining life's biochemistry: implications for abiogenesis. J. R. Soc. Interface. 19, 20210814 (2022). . [CrossRef]

- Swenson, R. 2023 A grand unified theory for the unification of physics, life, information and cognition (mind). Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 381, 20220277 (2023). . [CrossRef]

- Cushman, S.A. Entropy, ecology and evolution: Toward a unified philosophy of biology. Entropy. 25, 405 (20lience23). . [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.N., Müller, F., Marques, J.C., Bastianoni, S. & Jørgensen, S.E. Thermodynamics in ecology-An introductory review. Entropy. 22(8), 820 (2020). . [CrossRef]

- Brown, O.R. & Hullender, D.A. Neo-Darwinism must mutate to survive. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Bio. 172, 24–38 (2022). . [CrossRef]

-

Entropy and life https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entropy_and_life (Wikipedia, accessed 27 March 2024).

-

Ludwig Boltzmann quotes https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/178457. (DeVoe, H., accessed 27 March 2024).

- Brillouin; L. The negentropy principle of information. J. Appl. Phys. 24, 1152–1163 (1953). . [CrossRef]

- Wilson J.A. Entropy, not negentropy. Nature. 219, 535–536 (1968). . [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M., Chen, Y.Q., & Chen J.W. Carbon-Based Evolutionary Theory. Preprints, 2024. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202010.0004/v13.

- Bejan, A. The principle underlying all evolution, biological, geophysical, social and technological. Philos. Trans. A. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 381(2252), 20220288 (2023). . [CrossRef]

- Atkins, P.; de Paula, J, & Keeler, J. Atkins' physical chemistry: Molecular thermodynamics and kinetics (Oxford University Press, 2019).

- Roach, T.N.F. Use and abuse of entropy in biology: A case for caliber. Entropy. 22, 1335 (2020). . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).