Submitted:

02 April 2024

Posted:

03 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolates

2.2.1. DNA Extraction

2.2.2. gyrB Sequencing

2.3. Molecular Serotyping

2.4. Genetic Typing Using PCR-Based DNA Fingerprinting Techniques

2.4.1. REP-PCR

2.4.2. BOX-PCR

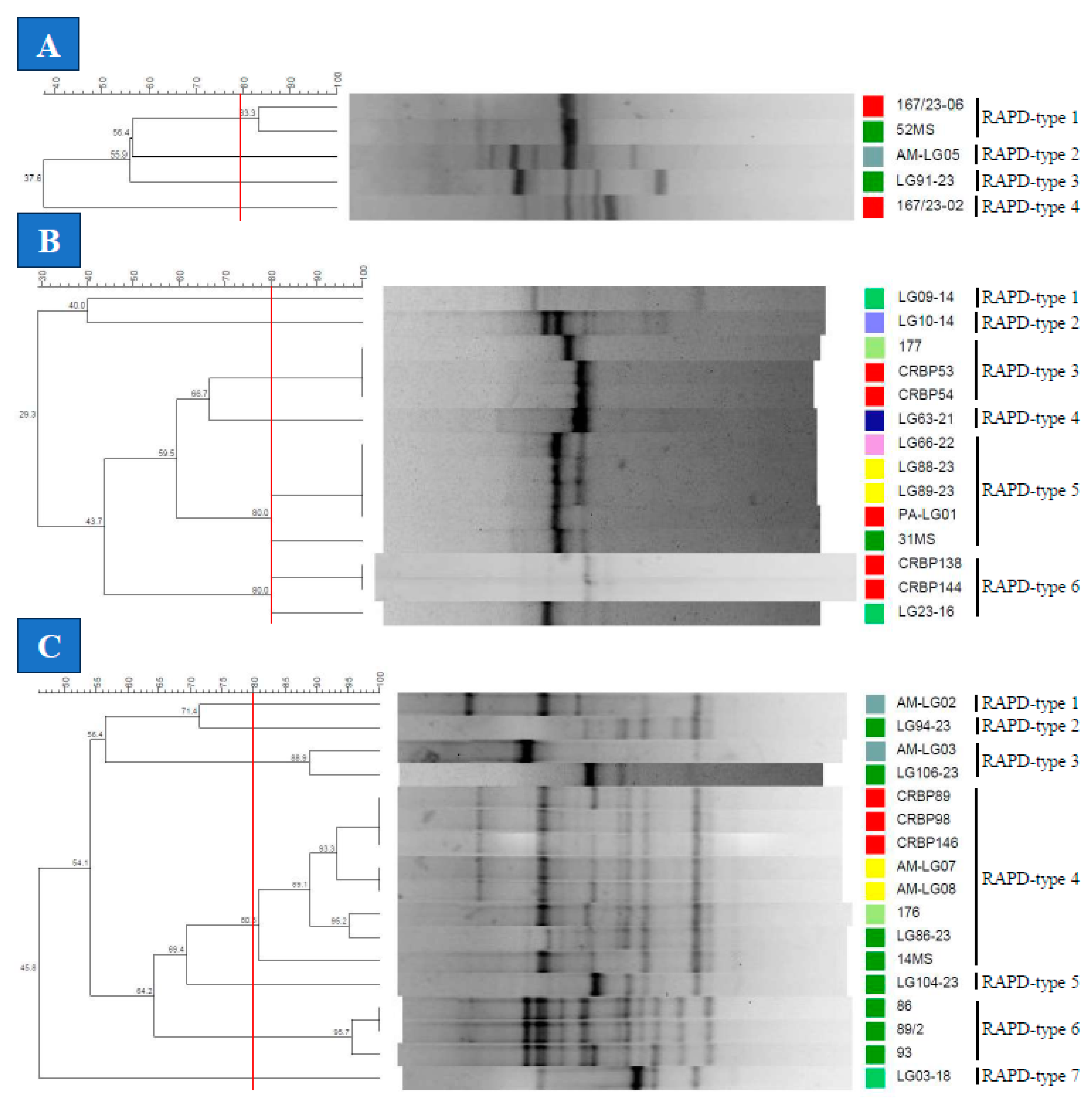

2.4.3. RAPD-PCR

2.4.4. Analysis of Agarose Gels

3. Results

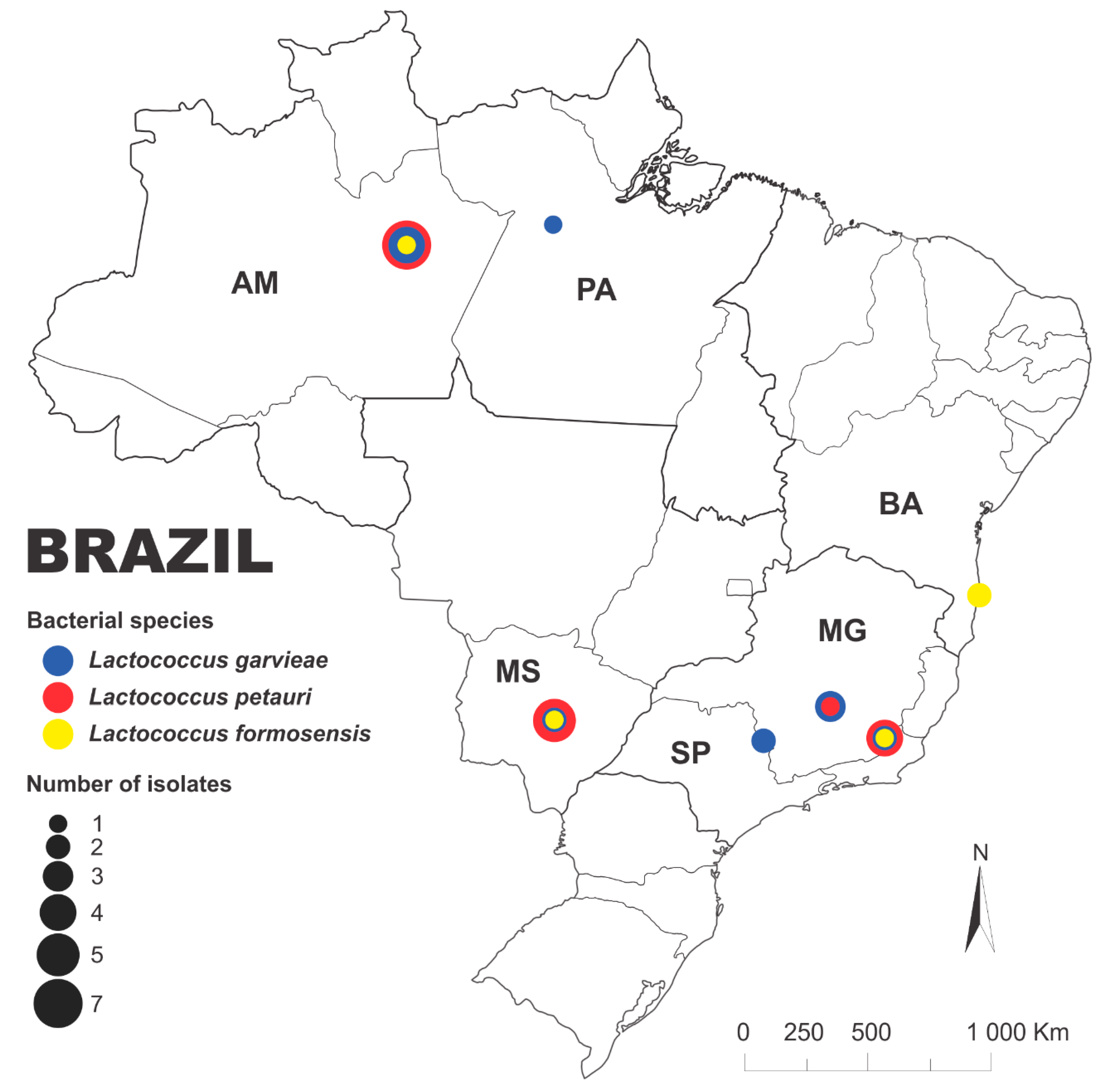

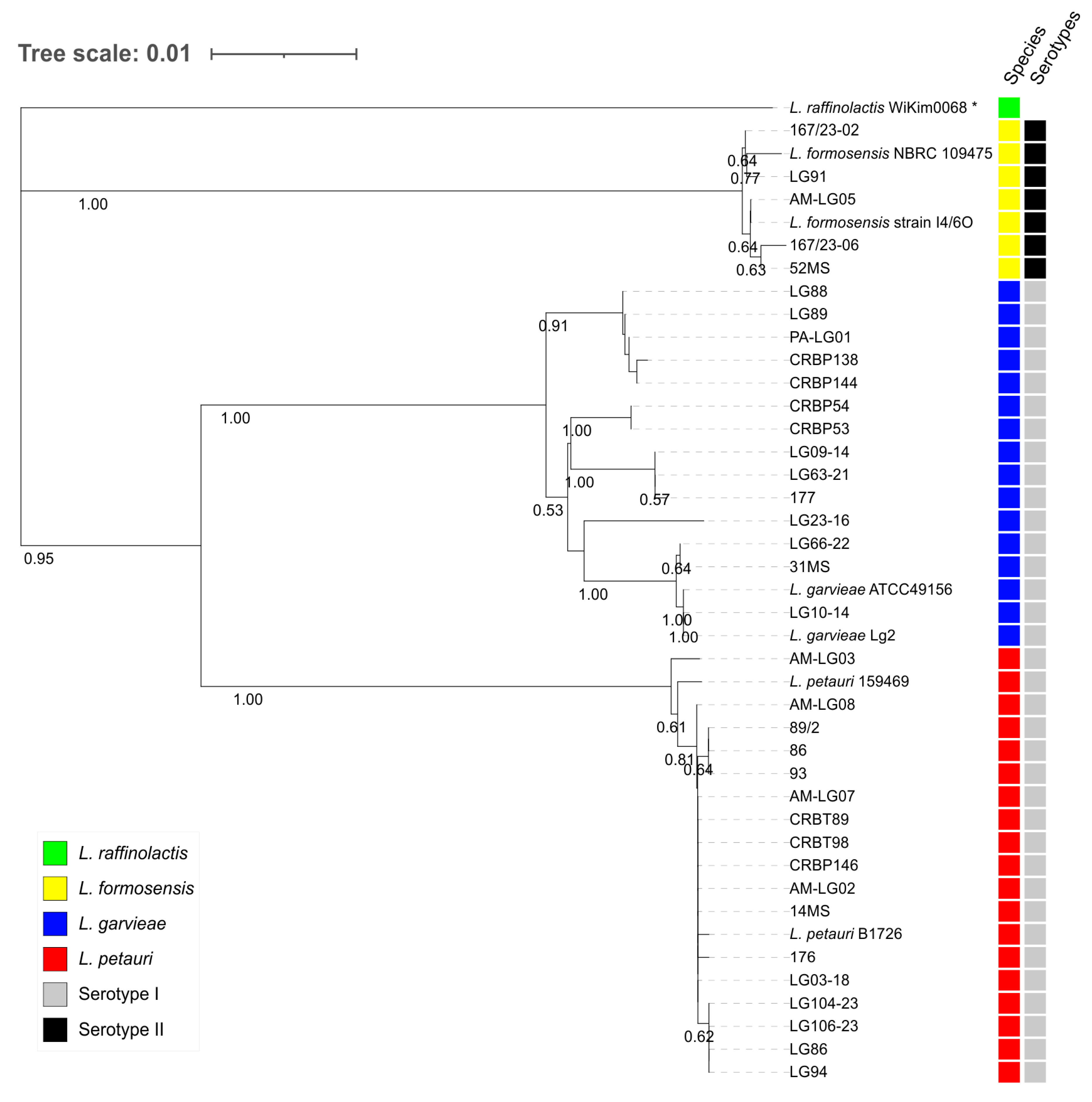

3.1. Bacterial Identification

3.2. Serotyping of the Lactococcus spp. Strains

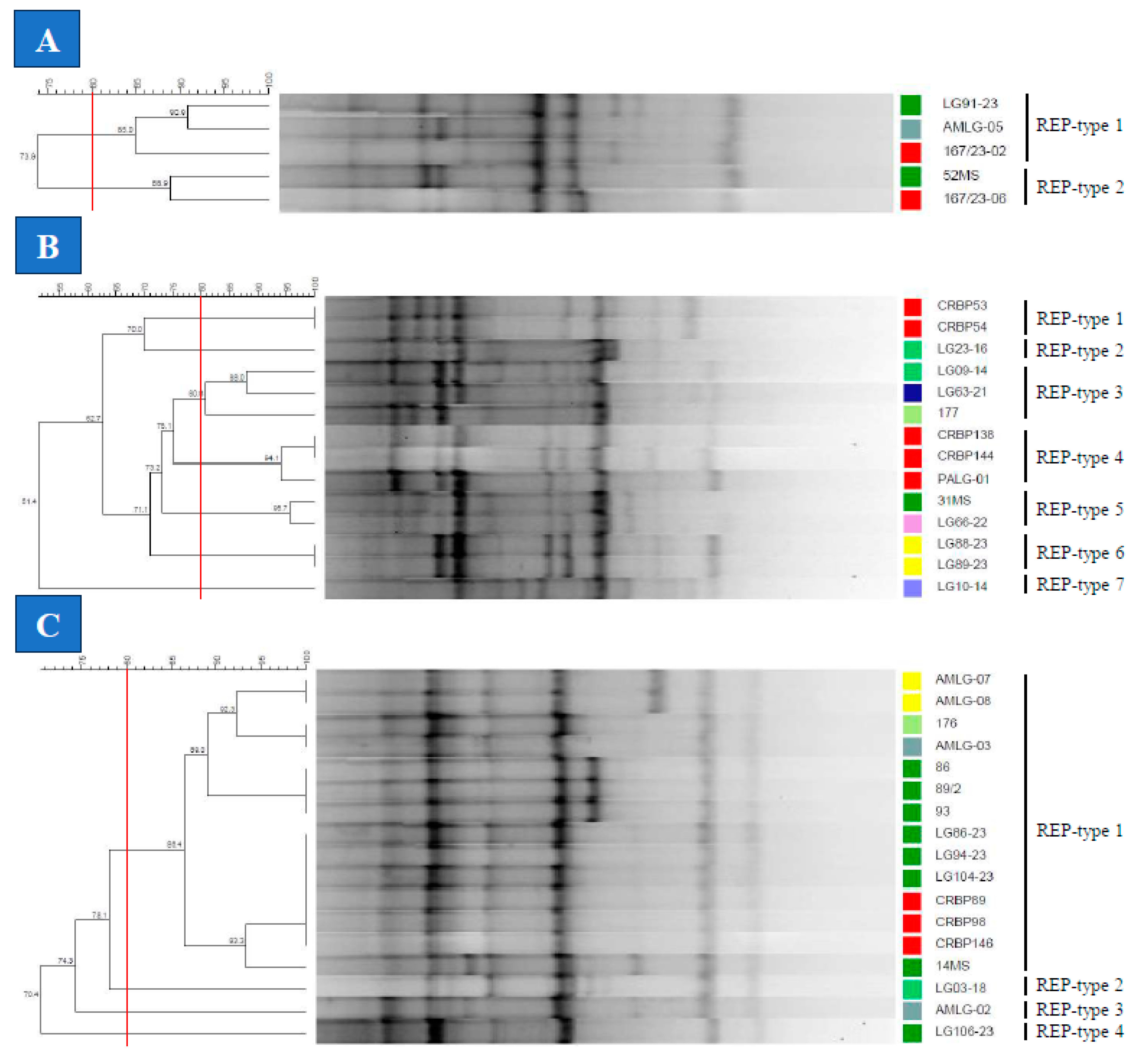

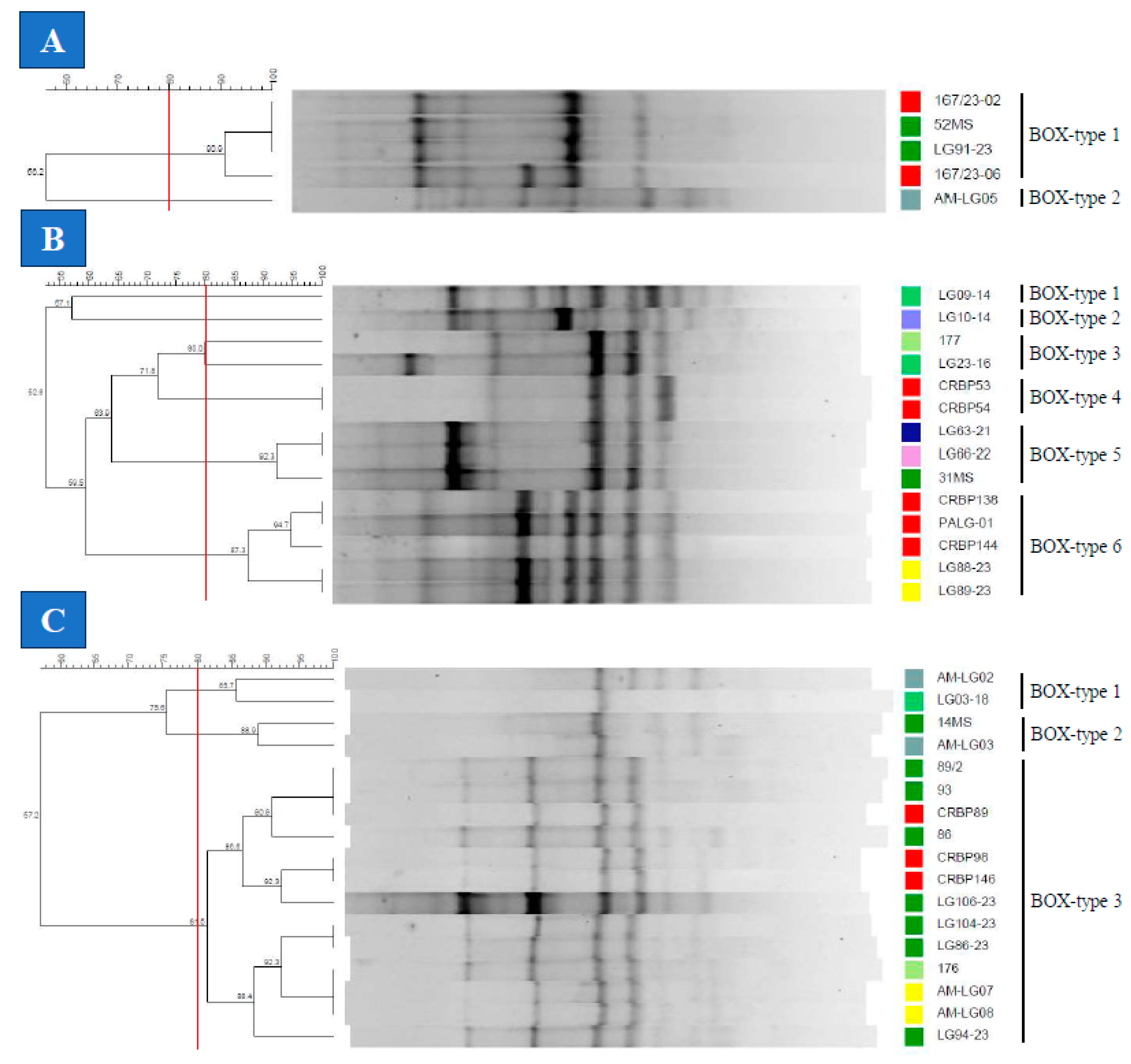

3.3. Genotyping of the Lactococcus spp. Isolates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Approval

References

- Altinok, I.; Ozturk, R.C.; Ture, M. NGS Analysis Revealed That Lactococcus garvieae Lg-Per Was Lactococcus petauri in Türkiye. J. Fish Dis. 2022, 45, 1839–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, T.; Yazdi, Z.; Littman, E.; Shahin, K.; Heckman, T.I.; Quijano Cardé, E.M.; Nguyen, D.T.; Hu, R.; Adkison, M.; Veek, T.; et al. Detection and Virulence of Lactococcus garvieae and L. petauri from Four Lakes in Southern California. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 2023, 35, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.J.; Klesius, P.H.; Shoemaker, C.A. First Isolation and Characterization of Lactococcus garvieae from Brazilian Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.), and Pintado, Pseudoplathystoma corruscans (Spix & Agassiz). J. Fish Dis. 2009, 32, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, H.C.S.; Leal, C.A.G.; Cavalcante, R.B.; Figueiredo, H.C.P.; Arijo, S.; Moriñigo, M.A.; Ishikawa, M.; Borra, R.C.; Ranzani-Paiva, M.J.T. Lactococcus garvieae Outbreaks in Brazilian Farms Lactococcosis in Pseudoplatystoma Sp. – Development of an Autogenous Vaccine as a Control Strategy. J. Fish Dis. 2017, 40, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, R.C.; Rosa, J.C.C.; Resende, L.F.L.; de Pádua, S.B.; de Oliveira Barbosa, F.; Zerbini, M.T.; Tavares, G.C.; Figueiredo, H.C.P. Emerging Fish Pathogens Lactococcus petauri and L. garvieae in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Farmed in Brazil. Aquaculture 2023, 565, 739093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, C.I.F.; Guidoli, M.G.; Domitrovic, H.A.; Blanco, T.K. Lactococosis En Pseudoplatystoma reticulatum. Rev. Vet. 2017, 28, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, C.; Irgang, R.; Valladares-Carranza, B.; Collarte, C.; Avendaño-Herrera, R. First Identification and Characterization of Lactococcus garvieae Isolated from Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Cultured in Mexico. Animals 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahin, K.; Veek, T.; Heckman, T.I.; Littman, E.; Mukkatira, K.; Adkison, M.; Welch, T.J.; Imai, D.M.; Pastenkos, G.; Camus, A.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Lactococcus garvieae from Rainbow Trout, Onchorhyncus mykiss, from California, USA. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 2326–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bwalya, P.; Hang’ombe, B.M.; Evensen, Ø.; Mutoloki, S. Lactococcus garvieae Isolated from Lake Kariba (Zambia) Has Low Invasive Potential in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). J. Fish Dis. 2021, 44, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyburgh, C.M.; Bragg, R.R.; Boucher, C.E. Lactococcus garvieae: An Emerging Bacterial Pathogen of Fish. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2017, 123, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salogni, C.; Bertasio, C.; Accini, A.; Gibelli, L.R.; Pigoli, C.; Susini, F.; Podavini, E.; Scali, F.; Varisco, G.; Alborali, G.L. The Characterisation of Lactococcus garvieae Isolated in an Outbreak of Septicaemic Disease in Farmed Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax, Linnaues 1758) in Italy. Pathogens 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, A.I.; del Mar Blanco, M.; Colussi, S.; Kotzamanidis, C.; Prearo, M.; Altinok, I.; Acutis, P.L.; Volpatti, D.; Alba, P.; Feltrin, F.; et al. The Association of Lactococcus petauri with Lactococcosis Is Older than Expected. Aquaculture 2024, 578, 740057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyngor, M.; Zlotkin, A.; Ghittino, C.; Prearo, M.; Douet, D.-G.; Chilmonczyk, S.; Eldar, A. Clonality and Diversity of the Fish Pathogen Lactococcus garvieae in Mediterranean Countries. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5132–5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Hur, J.W.; Cho, J.B.; Park, K.H.; Jung, H.J.; Kang, Y.J. Introduction of Bacterial and Viral Pathogens from Imported Ornamental Finfish in South Korea. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohbayashi, K.; Oinaka, D.; Hoai, T.D.; Yoshida, T.; Nishiki, I. PCR-Mediated Identification of the Newly Emerging Pathogen Lactococcus garvieae Serotype II from Seriola quinqueradiata and S. dumerili. Fish Pathol. 2017, 52, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Pham, T.H.; Poudyal, S.; Cheng, L.-W.; Nazareth, S.C.; Wang, P.-C.; Chen, S.-C. First Report on Genetic Characterization, Cell-Surface Properties and Pathogenicity of Lactococcus garvieae, Emerging Pathogen Isolated from Cage-Cultured Cobia (Rachycentron canadum). Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahi, N.; Mallik, S.K.; Sahoo, M.; Chandra, S.; Singh, A.K. First Report on Characterization and Pathogenicity Study of Emerging Lactococcus garvieae Infection in Farmed Rainbow Trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), from India. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldar, A.; Goria, M.; Ghittino, C.; Zlotkin, A. Herve Bercovier Biodiversity of Lactococcus garvieae Strains Isolated from Fish in Europe, Asia, and Australia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Wright, A. Genus Lactococcus. In Lactic Acid Bacteria: Microbiological and Functional Aspects; Vinderola, G., Ouwehand, A., Salminen, S., von Wright, A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2019; pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- de Ruyter, T.; Littman, E.; Yazdi, Z.; Adkison, M.; Camus, A.; Yun, S.; Welch, T.J.; Keleher, W.R.; Soto, E. Comparative Evaluation of Booster Vaccine Efficacy by Intracoelomic Injection and Immersion with a Whole-Cell Killed Vaccine against Lactococcus petauri Infection in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Pathogens 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.L.; Cerutti, L.; Gürtler, A.; Griener, T.; Zelazny, A. Stefan Emler Performance and Application of 16S RRNA Gene Cycle Sequencing for Routine Identification of Bacteria in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, C.; Ricci, G.; Borgo, F.; Rollando, A.; Fortina, M.G. Genetic Investigation within Lactococcus garvieae Revealed Two Genomic Lineages. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012, 332, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.; Chen, M.-Y.; Sudpraseart, C.; Lin, P.; Yoshida, T.; Wang, P.-C.; Chen, S.-C. Genotyping and Phenotyping of Lactococcus garvieae Isolates from Fish by Pulse-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) and Electron Microscopy Indicate Geographical and Capsular Variations. J. Fish Dis. 2022, 45, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, T.J.; Grimwood, K.; Ramsay, K.A.; Rainey, P.B.; Bell, S.C. Comparison of Three Molecular Techniques for Typing Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates in Sputum Samples from Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Corral, Y.; Santos, Y. Clonality of Lactococcus garvieae Isolated from Rainbow Trout Cultured in Spain: A Molecular, Immunological, and Proteomic Approach. Aquaculture 2021, 545, 737190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.A.A.; Leal, C.A.G.; Leite, R.C.; Figueiredo, H.C.P. Genotyping of Streptococcus dysgalactiae Strains Isolated from Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.). J. Fish Dis. 2014, 37, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastião, F.A.; Furlan, L.R.; Hashimoto, D.T.; Pilarski, F. Identification of Bacterial Fish Pathogens in Brazil by Direct Colony PCR and 16S RRNA Gene Sequencing. Adv. Microbiol. 2015, 05, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, G.B.N.; Pereira, F.L.; Zegarra, A.U.; Tavares, G.C.; Leal, C.A.; Figueiredo, H.C.P. Use of MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry for the Fast Identification of Gram-Positive Fish Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, S.L.A.; Chagas, E.C.; Oliveira, P.M.; Benavides, M.V.; Majolo, C.; Boijink, C. de L.; Tavares-Dias, M.; Ishikawa, M.M.; Fujimoto, R.Y.; Rodrigues, F.B.; et al. Agentes Patogênicos de Tambaquis Cultivados, Com Destaque Para Registros Em Rio Preto Da Eva, AM 2016, 80.

- Rosário, A.E.C. do; Henrique, M.C.; Costa, É.J.C. da; Barbanti, A.C.C.; Tavares, G.C. Surtos de Bacteriose Em Juvenis de Pirarucu (Arapaima gigas) Provevientes de Pisciculturas Amazônicas e Avaliação Da Sensibilidade de Aeromonas jandaei a Antimicrobianos. In Enfermidades parasitárias e bacterianas na piscicultura brasileira: insights e perspectivas; Cruz, M.G. da, Castro, J. da S., Jerônimo, G.T., Eds.; i-EDUCAM, 2023; pp. 33–46.

- Cardoso, P.H.M.; Moreno, L.Z.; de Oliveira, C.H.; Gomes, V.T.M.; Silva, A.P.S.; Barbosa, M.R.F.; Sato, M.I.Z.; Balian, S.C.; Moreno, A.M. Main Bacterial Species Causing Clinical Disease in Ornamental Freshwater Fish in Brazil. Folia Microbiol. (Praha). 2021, 66, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Prospects for Inferring Very Large Phylogenies by Using the Neighbor-Joining Method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 11030–11035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The Neighbor-Joining Method: A New Method for Reconstructing Phylogenetic Trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dice, L.R. Measures of the Amount of Ecologic Association between Species. Ecology 1945, 26, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, R.; Michener, C. A Statistical Method for Evaluating Systematic Relationship. Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull. 1958, 38, 1409–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, P.; Berry, G.; Matthews, J.N.S. Statistical Methods in Medical Research; 4th ed.; Blackwell Science Ltd: Bodmin, 2002; ISBN 9780470773666.

- Hunter, P.R. Reproducibility and Indices of Discriminatory Power of Microbial Typing Methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990, 28, 1903–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, P.R.; Gaston, M.A. Numerical Index of the Discriminatory Ability of Typing Systems: An Application of Simpson’s Index of Diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1988, 26, 2465–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubert, L.; Arabie, P. Comparing Partitions. J. Classif. 1985, 2, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.L. A Method for Comparing Two Hierarchical Clusterings: Comment. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1983, 78, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F.R.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Ramirez, M. A Confidence Interval for the Wallace Coefficient of Concordance and Its Application to Microbial Typing Methods. PLoS One 2008, 3, e3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.-A.; Wang, P.-C.; Yoshida, T.; Liaw, L.-L.; Chen, S.-C. Development of a Sensitive and Specific LAMP PCR Assay for Detection of Fish Pathogen Lactococcus garvieae. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2013, 102, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibello, A.; Galán-Sánchez, F.; Blanco, M.M.; Rodríguez-Iglesias, M.; Domínguez, L.; Fernández-Garayzábal, J.F. The Zoonotic Potential of Lactococcus garvieae: An Overview on Microbiology, Epidemiology, Virulence Factors and Relationship with Its Presence in Foods. Res. Vet. Sci. 2016, 109, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrell, D.; Balcázar, J.L.; Ruiz-Zarzuela, I.; de Blas, I.; Gironés, O.; Múzquiz, J.L. Lactococcus garvieae in Fish: A Review. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2006, 29, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravelo, C.; Magariños, B.; López-Romalde, S.; Alicia, E.T.; Jesús, L.R. Molecular Fingerprinting of Fish-Pathogenic Lactococcus garvieae Strains by Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA Analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, M.M.; Abdelsalam, M.; Kawato, S.; Harakawa, S.; Kawakami, H.; Hirono, I.; Kondo, H. Comparative Genome Analyses of Three Serotypes of Lactococcus Bacteria Isolated from Diseased Cultured Striped Jack (Pseudocaranx dentex). J. Fish Dis. 2023, 46, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neupane, S.; Rao, S.; Yan, W.-X.; Wang, P.-C.; Chen, S.-C. First Identification, Molecular Characterization, and Pathogenicity Assessment of Lactococcus garvieae Isolated from Cultured Pompano in Taiwan. J. Fish Dis. 2023, 46, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salighehzadeh, R.; Sharifiyazdi, H.; Akhlaghi, M.; Soltanian, S. Serotypes, Virulence Genes and Polymorphism of Capsule Gene Cluster in Lactococcus garvieae Isolated from Diseased Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and Mugger Crocodile (Crocodylus palustris) in Iran. Iran. J. Vet. Res. 2020, 21, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.Z.; Nishiki, I.; Yanagi, S.; Yoshida, T. Epidemiological Study on Newly Emerging Lactococcus garvieae Serotype II Isolated from Marine Fish Species in Japan. Fish Pathol. 2019, 54, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalendar, R.; Lee, D.; Schulman, A.H. Java Web Tools for PCR, in Silico PCR, and Oligonucleotide Assembly and Analysis. Genomics 2011, 98, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neoh, H.; Tan, X.-E.; Sapri, H.F.; Tan, T.L. Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE): A Review of the “Gold Standard” for Bacteria Typing and Current Alternatives. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 74, 103935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borba, M.P.; Ballarini, A.E.; Witusk, J.P.D.; Lavin, P.; Van Der Sand, S. Evaluation of BOX-PCR and REP-PCR as Molecular Typing Tools for Antarctic Streptomyces. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 3573–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.A. Bacterial Typing Methods from Past to Present: A Comprehensive Overview. Gene Reports 2022, 29, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, A.N.; Roggenkamp, A.; Hoffmann, H. Specificity of Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus and Repetitive Extragenic Palindromic Polymerase Chain Reaction for the Detection of Clonality within the Enterobacter cloacae Complex. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2005, 53, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foschino, R.; Nucera, D.; Volponi, G.; Picozzi, C.; Ortoffi, M.; Bottero, M.T. Comparison of Lactococcus garvieae Strains Isolated in Northern Italy from Dairy Products and Fishes through Molecular Typing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 105, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, M.; Buyukekiz, A.G.; Saticioglu, I.B.; Cengiz, M.; Sahinturk, P.; Altun, S. Epidemiology, Genotypic Diversity, and Antimicrobial Resistance of Lactococcus garvieae in Farmed Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) TT -. IFRO 2020, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fadaeifard, F.; Rabiei, M.; Sharifpour, M.F. Genetic Characterization of Lactococcus garvieae Isolated from Farmed Rainbow Trout by Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA-PCR in Iran. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2020, 71, 2023–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, C.; Ricci, G.; Milani, C.; Lugli, G.A.; Ventura, M.; Eraclio, G.; Borgo, F.; Fortina, M.G. Lactococcus garvieae: Where Is It From? A First Approach to Explore the Evolutionary History of This Emerging Pathogen. PLoS One 2013, 8, e84796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, G.C.; de Queiroz, G.A.; Assis, G.B.N.; Leibowitz, M.P.; Teixeira, J.P.; Figueiredo, H.C.P.; Leal, C.A.G. Disease Outbreaks in Farmed Amazon Catfish (Leiarius marmoratus x Pseudoplatystoma corruscans) Caused by Streptococcus agalactiae, S. iniae, and S. dysgalactiae. Aquaculture 2018, 495, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolate | Species | Host | Tissue | Year | Brazilian state | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14MS | L. petauri | Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum | Kidney | 2012 | MS | [27] |

| 167/23-02 | L. formosensis | Arapaima gigas | Brain | 2023 | BA | This study |

| 167/23-06 | L. formosensis | Arapaima gigas | Brain | 2023 | BA | This study |

| 176 | L. petauri | Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum | Brain | 2012 | MS | [4] |

| 177 | L. garvieae | Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum | Brain | 2012 | MS | [4] |

| 31MS | L. garvieae | Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum | Kidney | 2012 | MS | [27] |

| 52MS | L. formosensis | Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum | Brain | 2012 | MS | [27] |

| 86 | L. petauri | Pseudoplatystoma sp. | Brain | 2012 | MS | [4] |

| 89/2 | L. petauri | Pseudoplatystoma sp. | Brain | 2012 | MS | [4] |

| 93 | L. petauri | Pseudoplatystoma sp. | Brain | 2012 | MS | [4] |

| AM-LG02 | L. petauri | Colossoma macropomum | Intestine | 2020 | AM | This study |

| AM-LG03 | L. petauri | Colossoma macropomum | Intestine | 2022 | AM | This study |

| AM-LG05 | L. formosensis | Colossoma macropomum | Intestine | 2022 | AM | This study |

| AM-LG07 | L. petauri | Brycon amazonicus | Brain | 2022 | AM | This study |

| AM-LG08 | L. petauri | Brycon amazonicus | Brain | 2022 | AM | This study |

| CRBP138 | L. garvieae | Arapaima gigas | Intestine | 2023 | AM | This study |

| CRBP144 | L. garvieae | Arapaima gigas | Intestine | 2023 | AM | This study |

| CRBP146 | L. petauri | Arapaima gigas | Intestine | 2023 | AM | This study |

| CRBP53 | L. garvieae | Arapaima gigas | Intestine | 2023 | AM | This study |

| CRBP54 | L. garvieae | Arapaima gigas | Intestine | 2023 | AM | This study |

| CRBT89 | L. petauri | Arapaima gigas | Intestine | 2023 | AM | This study |

| CRBT98 | L. petauri | Arapaima gigas | Intestine | 2023 | AM | This study |

| LG03-18 | L. petauri | Pseudoplatystoma corruscans | Brain | 2018 | MG | This study |

| LG09-14 | L. garvieae | Pseudoplatystoma corruscans | Kidney | 2014 | SP | [28] |

| LG10-14 | L. garvieae | Lophiosilurus alexandri | Brain | 2014 | MG | [28] |

| LG104-23 | L. petauri | Pseudoplatystoma sp. | Brain | 2023 | MG | This study |

| LG106-23 | L. petauri | Pseudoplatystoma sp. | Kidney | 2023 | MG | This study |

| LG23-16 | L. garvieae | Pseudoplatystoma corruscans | Brain | 2016 | SP | [60] |

| LG63-21 | L. garvieae | Hoplias macrophtalmus | Kidney | 2021 | MG | This study |

| LG66-22 | L. garvieae | Phractocephalus hemioliopterus | Kidney | 2022 | MG | This study |

| LG86-23 | L. petauri | Pseudoplatystoma sp. | Kidney | 2023 | MG | This study |

| LG88-23 | L. garvieae | Brycon amazonicus | Brain | 2023 | MG | This study |

| LG89-23 | L. garvieae | Brycon amazonicus | Kidney | 2023 | MG | This study |

| LG91-23 | L. formosensis | Pseudoplatystoma sp. | Brain | 2023 | MG | This study |

| LG94-23 | L. petauri | Pseudoplatystoma sp. | Brain | 2023 | MG | This study |

| PA-LG01 | L. garvieae | Arapaima gigas | Brain | 2018 | PA | [30] |

| Bacterial species | Evaluation Method | Number of types | SDI | ARI | WC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REP | BOX | RAPD | REP | BOX | RAPD | ||||

| LF | REP | 2 | 0.600 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.286 | 1.000 | 0.500 | 0.250 |

| BOX | 2 | 0.400 | 1.000 | 0.138 | 0.333 | 1.000 | 0.167 | ||

| RAPD | 4 | 0.900 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

| LG | REP | 7 | 0.901 | 1.000 | 0.429 | 0.221 | 1.000 | 0.667 | 0.444 |

| BOX | 6 | 0.835 | 1.000 | 0.261 | 0.400 | 1.000 | 0.400 | ||

| RAPD | 6 | 0.824 | 1.000 | 0.250 | 0.375 | 1.000 | |||

| LP | REP | 4 | 0.331 | 1.000 | 0.421 | 0.239 | 1.000 | 0.736 | 0.341 |

| BOX | 3 | 0.412 | 1.000 | 0.139 | 0.838 | 1.000 | 0.300 | ||

| RAPD | 7 | 0.765 | 1.000 | 0.969 | 0.750 | 1.000 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).