Submitted:

01 April 2024

Posted:

02 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problem Description

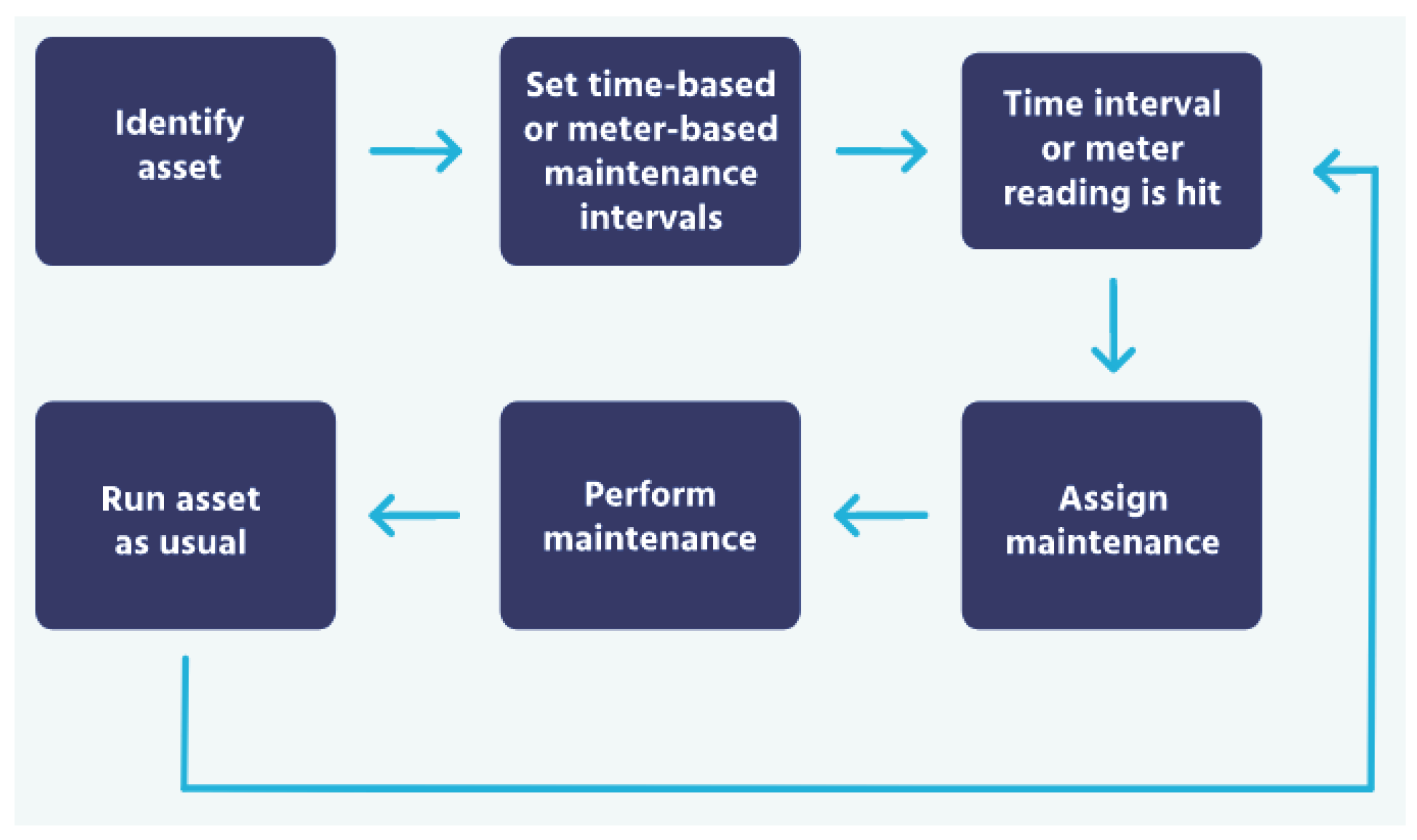

2.1. Problem Background

2.2. Problem Formulation

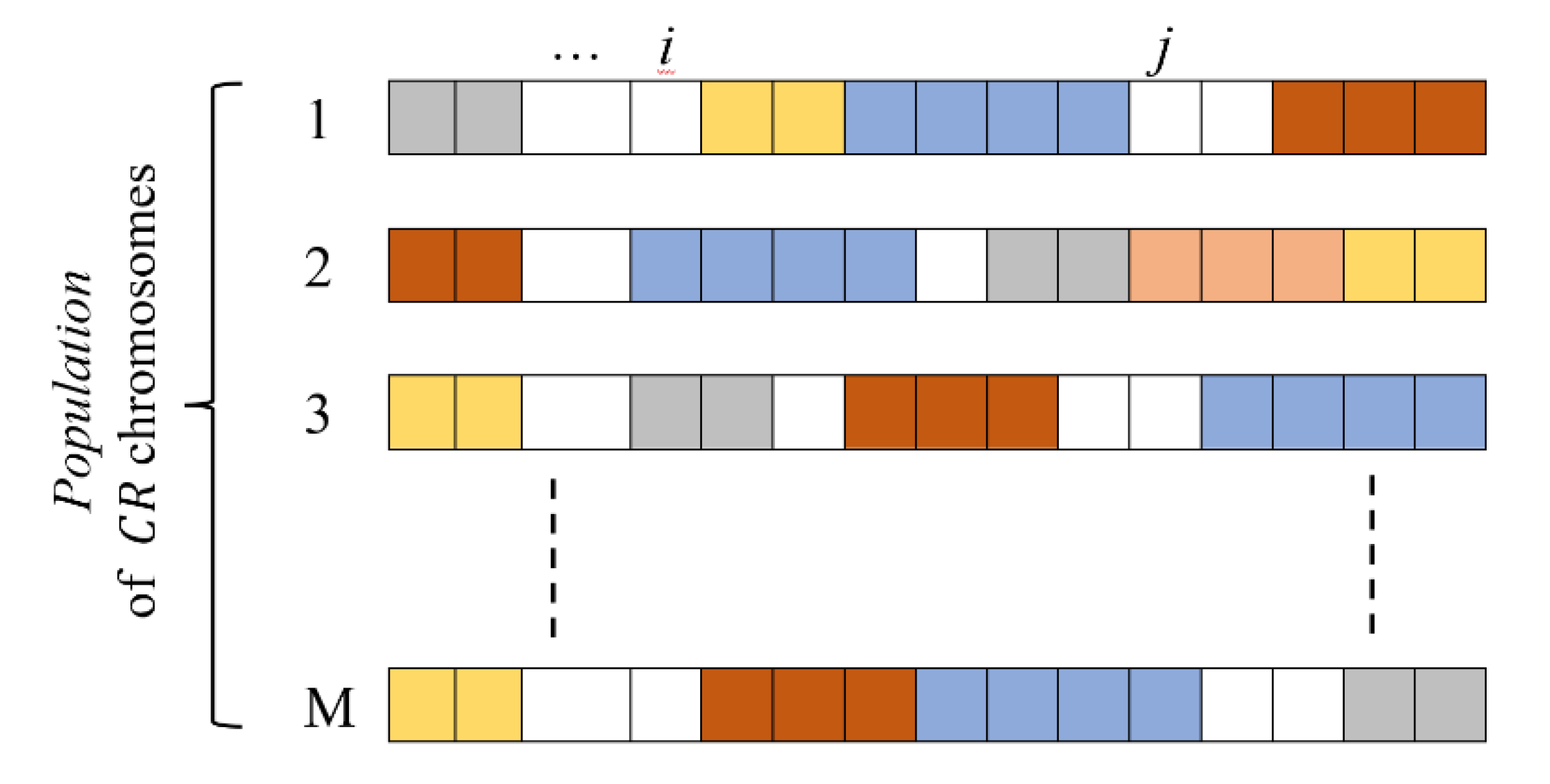

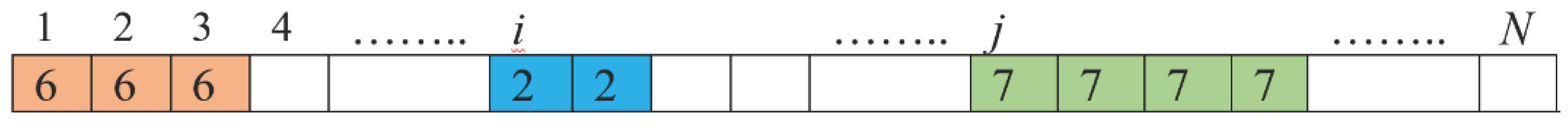

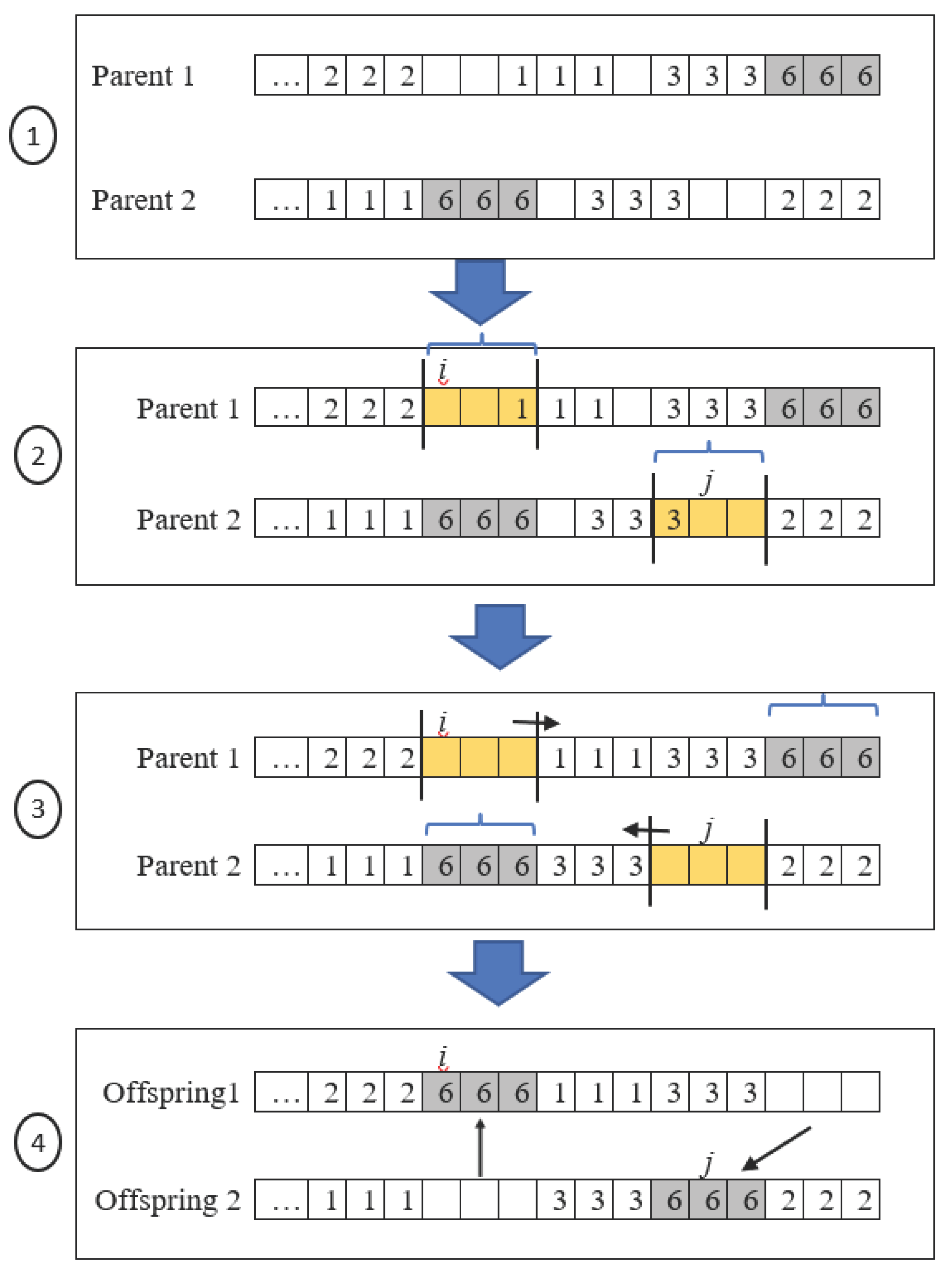

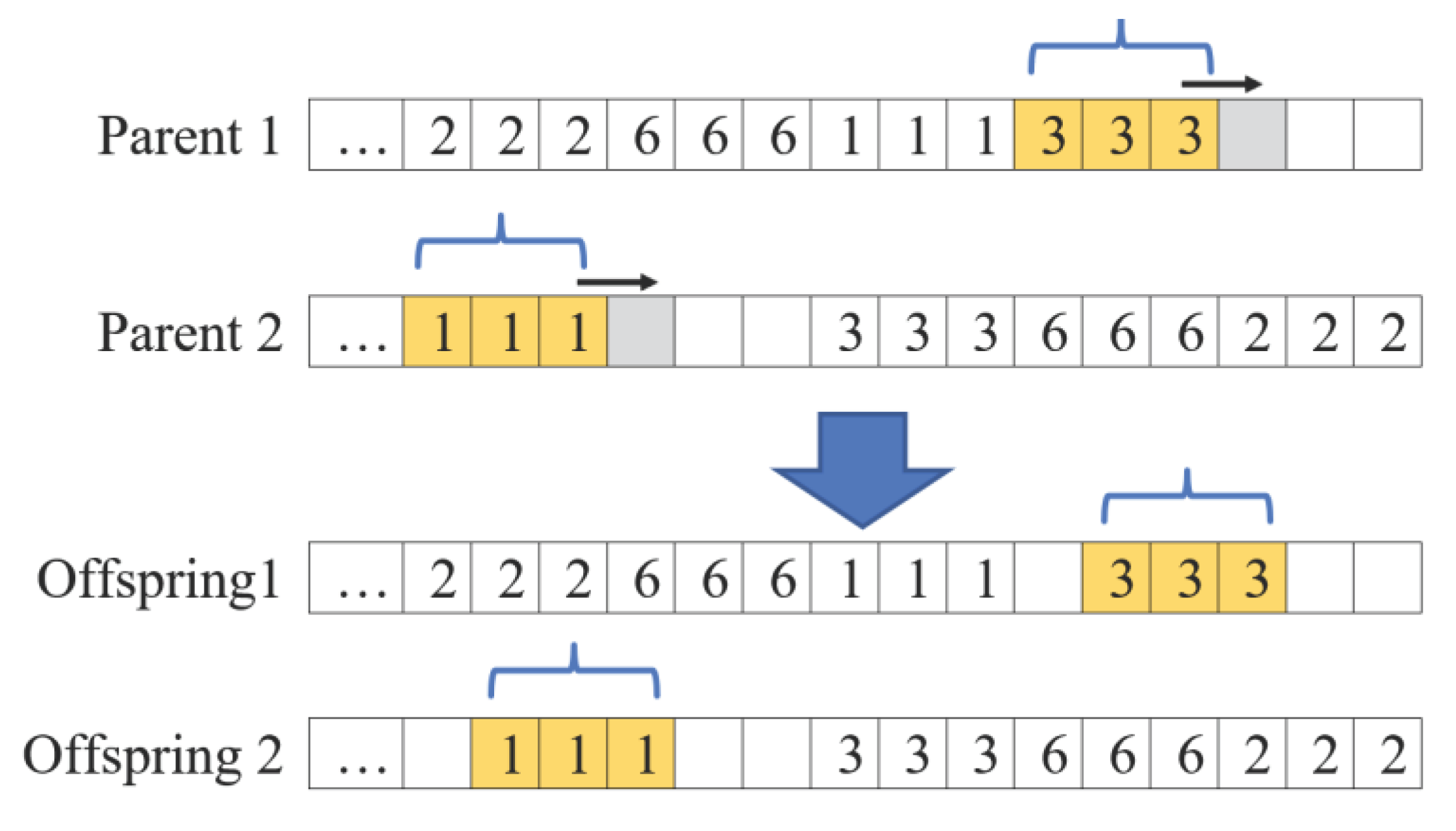

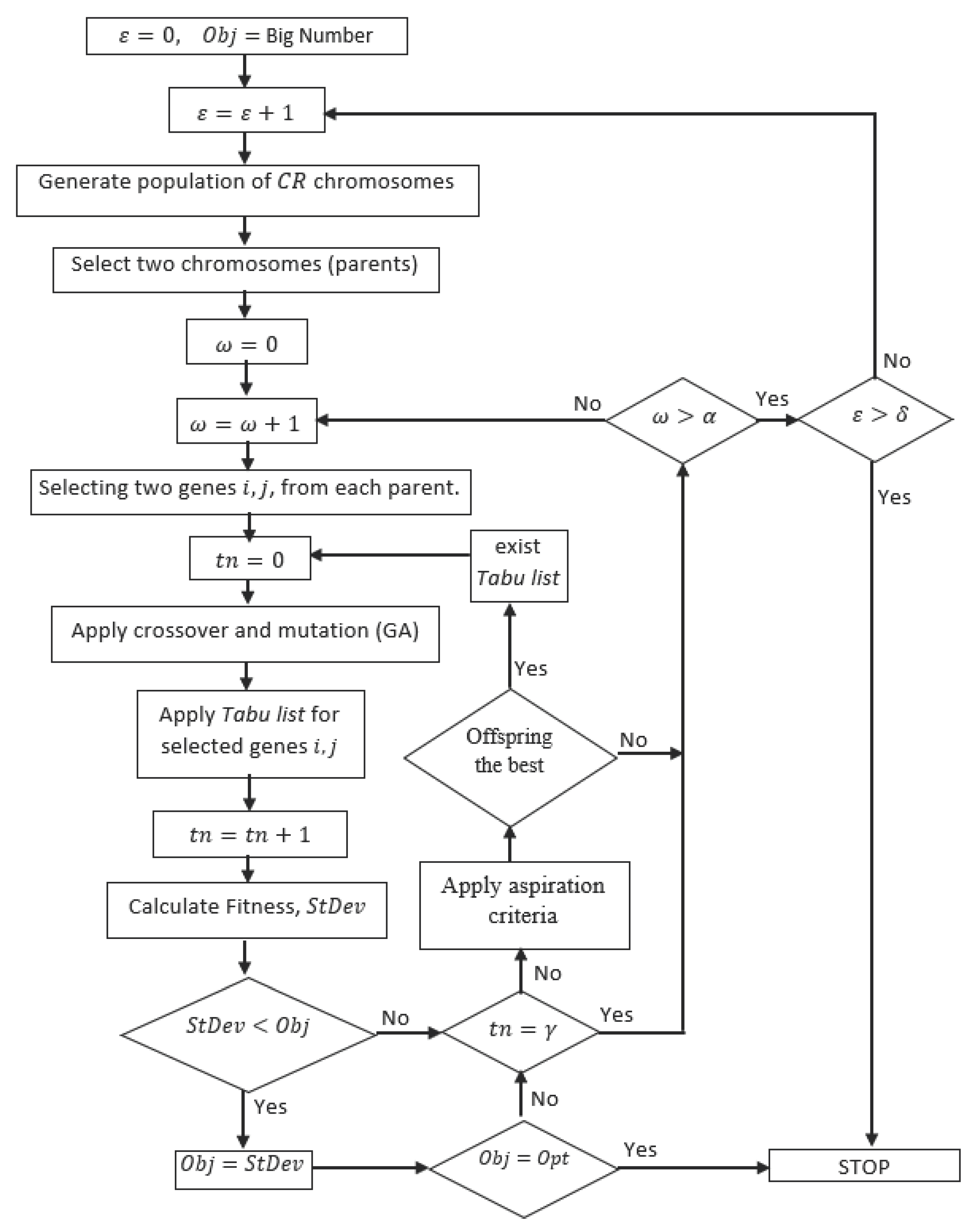

2.3. Hybrid Approach

3. Computational Results

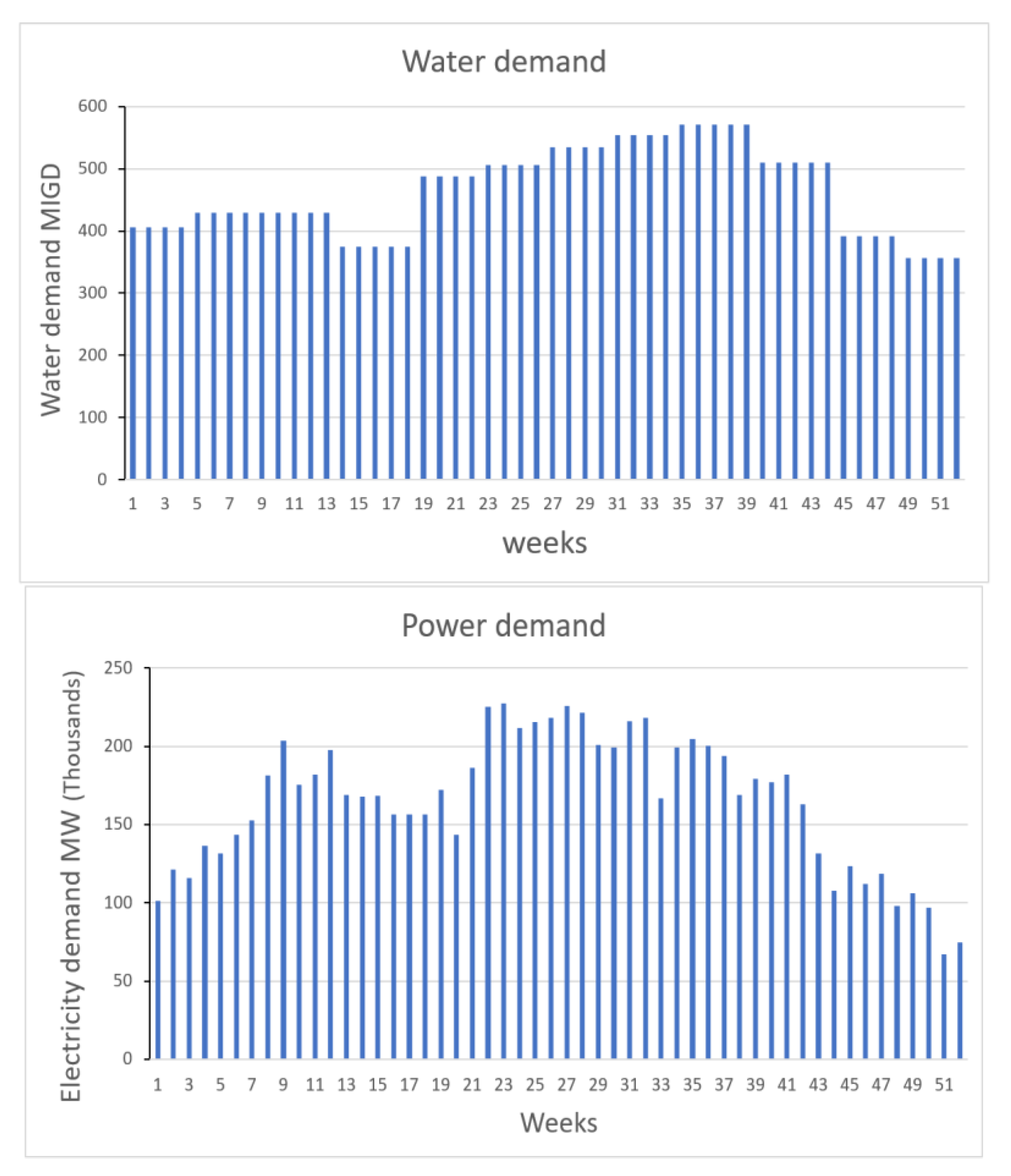

3.1. General Data

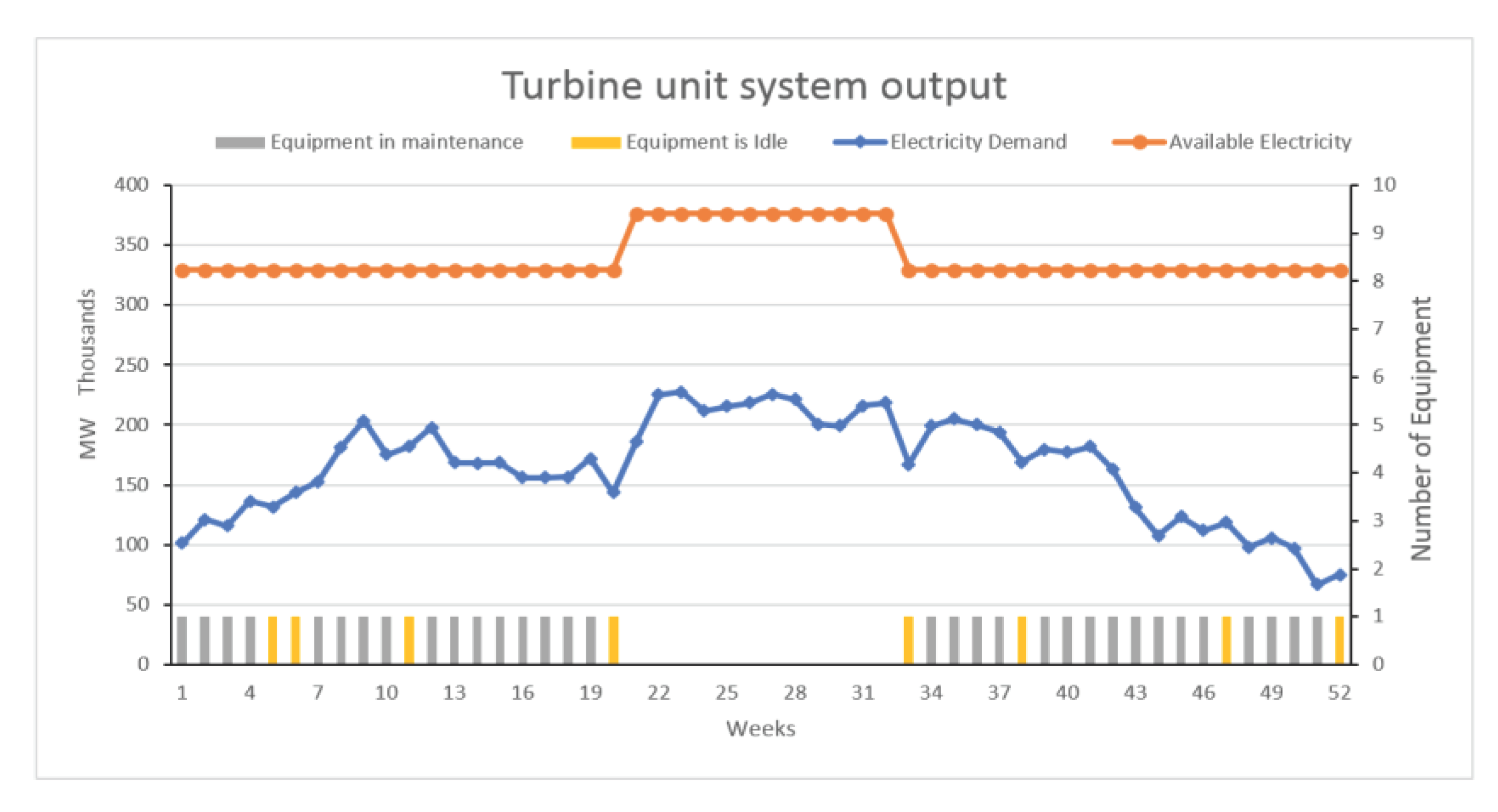

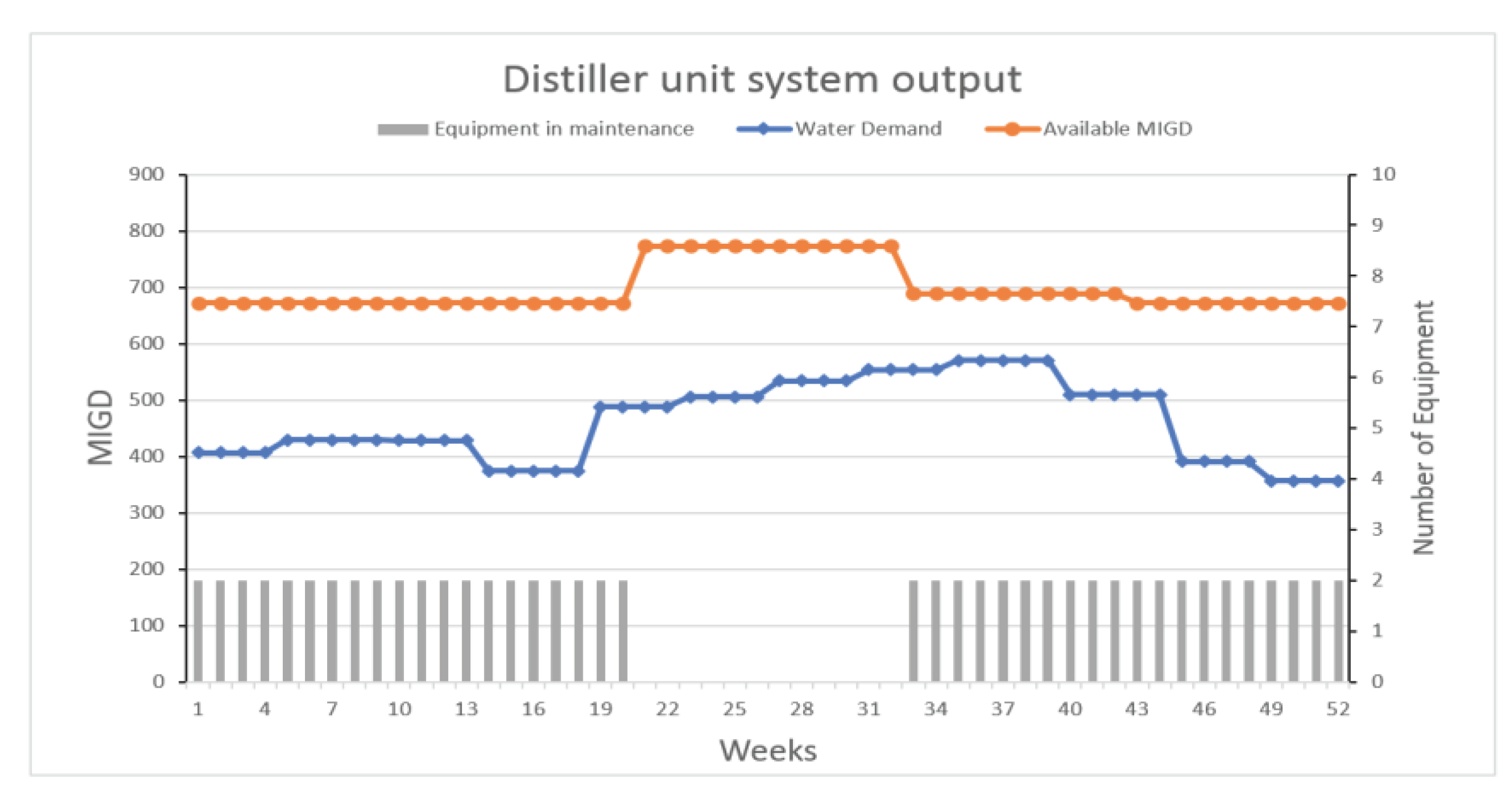

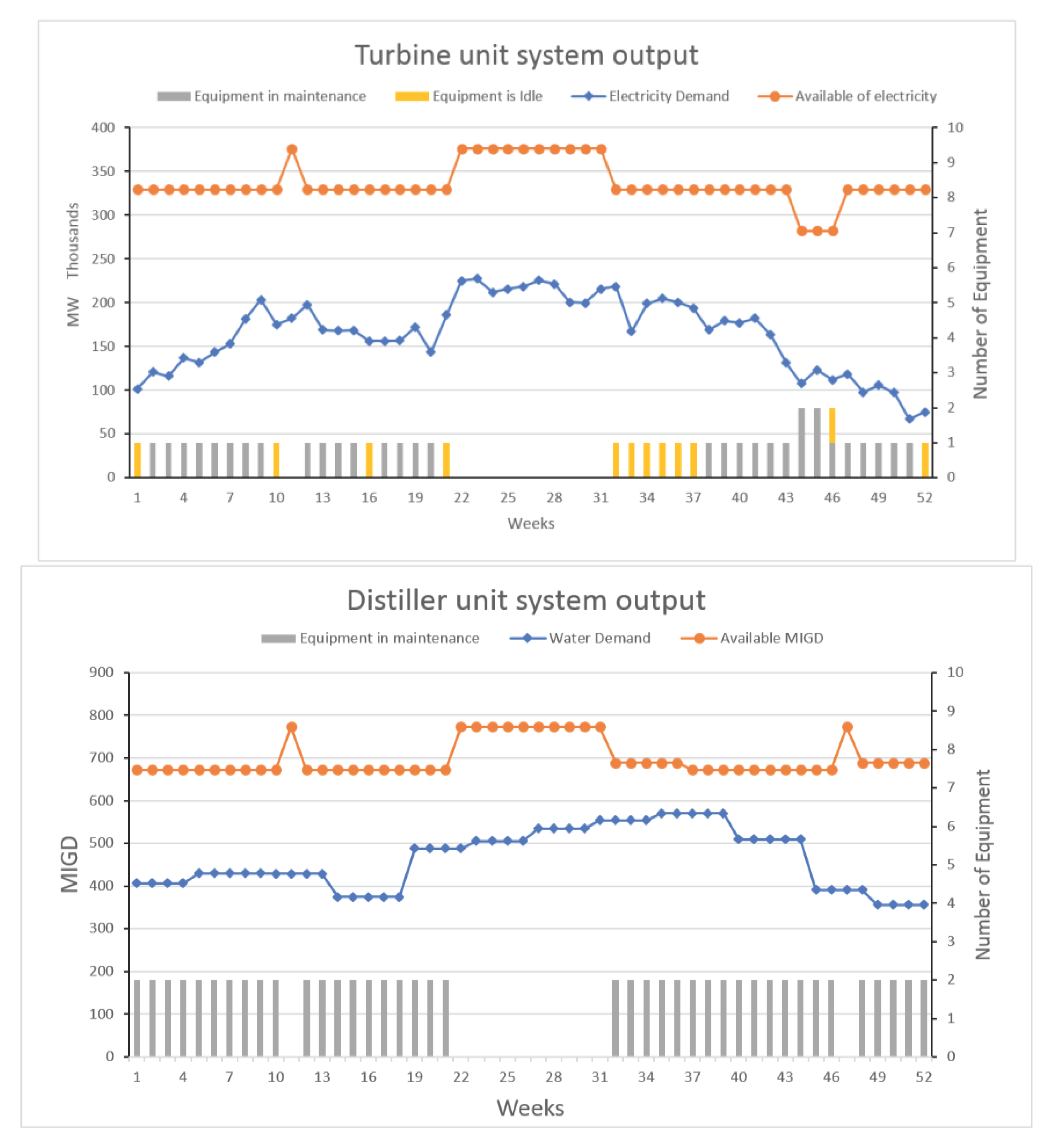

3.2. Model Validation and Analysis: Test1

3.3. Model Validation and Analysis: Test2

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 35 Latest Maintenance Statistics for 2024: Data, Adoption & Strategies - Financesonline.com.

- https://www.mrisoftware.com/blog/4-types-of-maintenance-management-strategies/.

- hpps://www.fiixsoftware.com/blog/evaluating-maintenance-strategies-select-model-asset-management/.

- Hpps:www.gofmx.com/preventive-maintenance.

- www.gofmx.com/blog/benefits-of-preventive-maintenance/.

- Joo, S.J.; Levary, R.R.; Ferris, M.E. Planning Preventive Maintenance for a Fleet of Police Vehicles Using Simulation. SIMULATION 1997, 68, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güner, G.G.; Sakar, C.T.; Yet, B. A Multicriteria Method to Form Optional Preventive Maintenance Plans: A Case Study of a Large Fleet of Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 70, 2153–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaei, N.; Banjevic, D.; Jardine, A.K.S. Workforce-constrained maintenance scheduling for military aircraft fleet: a case study. Ann. Oper. Res. 2011, 186, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.Y.; Yoon, K.B. Dynamic preventive maintenance scheduling of the modules of fighter aircraft based on random e ects regression model, Journal of the Operational Research Society, 2010, 61, 974–979.

- Lin, B.; Wu, J.; Lin, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X. Optimization of high-level preventive maintenance scheduling for high-speed trains. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 183, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhao, Y. Synchronized optimization of EMU train assignment and second-level preventive maintenance scheduling. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 215, 107893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, H.; Kim, J.-S.; Lee, D.-H. Operation and preventive maintenance scheduling for containerships: Mathe- matical model and solution algorithm, European Journal of Operational Research, 2013, 229, 626–636.

- Kamel, G.; Aly, M.F.; Mohib, A.; Afefy, I.H. Optimization of a multilevel integrated preventive maintenance scheduling mathematical model using genetic algorithm. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2020, 15, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.-Y.; Pan, Q.-K.; Miao, Z.-H.; Gao, L. An effective multi-start iterated greedy algorithm to minimize makespan for the distributed permutation flowshop scheduling problem with preventive maintenance. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 169, 114495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mourelatos, Z.; Singh, A. Optimal Preventive Maintenance Schedule Based on Lifecycle Cost and Time-Dependent Reliability. SAE Int. J. Mater. Manuf. 2012, 5, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Lu, B. Preventive maintenance scheduling for serial multi-station manufacturing systems with interaction between station reliability and product quality. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 122, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamad, K.; Alhajri, M. A zero-one integer programming for preventive maintenance scheduling for elec- tricity and distiller plants with production, Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, 2019, 26, 555–574.

- Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Lin, K.-Y. Preventive maintenance scheduling optimization based on opportunistic production-maintenance synchronization. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 32, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Domnguez, J.; Sanchez-Barroso, G.; Garca-Sanz-Calcedo, J. Scheduling of preventive maintenance in healthcare buildings using markov chain, Applied Sciences, 2020, 10, 52–63.

- Joseph, J.; Madhukumar, S. A novel approach to Data Driven Preventive Maintenance Scheduling of medical instruments. 2010 International Conference on Systems in Medicine and Biology (ICSMB). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 193–197.

- Liu, S.-S.; Faizal Ardhiansyah Ari n, M. Preventive maintenance model for national school buildings in indonesia using a constraint programming approach, Sustainability, 2021, 13, 1874.

- Gharoun, H.; Hamid, M.; Torabi, S.A. An integrated approach to joint production planning and reliability based multi-level preventive maintenance scheduling optimisation for a deteriorating system considering due-date satisfaction, International Journal of Systems Science: Operations & Logistics, 2022, 9, 489–511.

- Alhamad, K.; Alardhi, M.; Almazrouee, A. Preventive Maintenance Scheduling for Multicogeneration Plants with Production Constraints Using Genetic Algorithms. Adv. Oper. Res. 2015, 2015, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollahassani-Pour, M.; Abdollahi, A.; Rashidinejad, M. Application of a novel cost reduction index to preventive maintenance scheduling. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2014, 56, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamad, K.; M’hallah, R.; Lucas, C. A Mathematical Program for Scheduling Preventive Maintenance of Cogeneration Plants with Production. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamad, K.; Alkhezi, Y.; Alhajri, M.F. Nonlinear Integer Programming for Solving Preventive Maintenance Scheduling Problem for Cogeneration Plants with Production. Sustainability 2022, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetanat, A.; Sha pour, G. Generation maintenance scheduling in power systems using ant colony optimiza tion for continuous domains based 01 integer programming, Expert Systems with Applications, 2011, 38, 9729–9735.

- Perez Canto, S. Using 0/1 mixed integer linear programming to solve a reliability-centered problem of power plant preventive maintenance scheduling, Optimization and Engineering, 2011, 12, 333–347.

- Lapa, C.M.F.; Pereira, C.M.N.; de Barros, M.P. A model for preventive maintenance planning by genetic algorithms based in cost and reliability. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2006, 91, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimohammadi, M.; Behnamian, J. Preventive maintenance scheduling of electricity distribution network feeders to reduce undistributed energy: A case study in Iran. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 201, 107509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, K.P.; Chakpitak, N. Generator maintenance scheduling in power systems using metaheuristic-based hybrid approaches. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2006, 77, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, Y.S.; Szpytko, J.; del Castillo Serpa, A.M. Monte Carlo simulation model to coordinate the preventive maintenance scheduling of generating units in isolated distributed Power Systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 182, 106237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapat, N.; Tiwari, A.; Gan, X.-P.; Ince, N.Z.; Hutabarat, W. Preventive maintenance scheduling optimization: A review of applications for power plants, Advances in Through-life Engineering Services, 2017, 397-415.

- Froger, A.; Gendreau, M.; Mendoza, J.E.; Pinson. ; Rousseau, L.-M. Maintenance scheduling in the electricity industry: A literature review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 251, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Genetic Algorithms and the Optimal Allocation of Trials. SIAM J. Comput. 1973, 2, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Genetic algorithms, Scientific American, 1992, 267, 66–73.

- Glover, F. Tabu search part ii, ORSA Journal on computing, 1990, 2, 432.

| Unit | Equipment | Production | Unit | Equipment | Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | D1 | 50.4 1 | 5 | D1 | 50.4 |

| D2 | 50.4 | D2 | 50.4 | ||

| R | 47,040 2 | R | 47,040 | ||

| 2 | D1 | 50.4 | 6 | D1 | 50.4 |

| D2 | 50.4 | D2 | 50.4 | ||

| R | 47,040 | R | 47,040 | ||

| 3 | D1 | 50.4 | 7 | D1 | 40.2 |

| D2 | 50.4 | D2 | 40.2 | ||

| R | 47,040 | R | 47,040 | ||

| 4 | D1 | 50.4 | 8 | D1 | 40.2 |

| D2 | 50.4 | D2 | 40.2 | ||

| R | 47,040 | R | 47,040 |

| Symbol | CR | |||

| iteration | 10,000 | 50 | 4 | 100 |

| Proposal Approach | MEW | ||

| Distiller | St.Dev. | 59.6 | 70.724 |

| Average | 235.32 | 235.32 | |

| Min. Gap | 118.1 | 101.3 | |

| Turbine | St.Dev | 33519 | 33220.5 |

| Average | 175330 | 171712 | |

| Min. Gap | 124426 | 110971 |

| Week | Proposed Model | MEW | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment under PM | Idle | Equipment under PM | Idle | |

| 1 | B-2, D1-2, D2-2, R-2 | - | B-4, D1-4, D2-4 | R-4 |

| 2 | B-2, D1-2, D2-2, R-2 | - | B-4, D1-4, D2-4, R-4 | - |

| 3 | B-2, D1-2, D2-2, R-2 | - | B-4, D1-4, D2-4, R-4 | - |

| 4 | B-2, D1-2, D2-2, R-2 | - | B-4, D1-4, D2-4, R-4 | - |

| 5 | B-2, D1-2, D2-2 | R-2 | B-4, D1-4, D2-4, R-4 | - |

| 6 | B-5, D1-5, D2-5, R-5 | - | B-3, D1-3, D2-3, R-3 | - |

| 7 | B-5, D1-5, D2-5, R-5 | - | B-3, D1-3, D2-3, R-3 | - |

| 8 | B-5, D1-5, D2-5, R-5 | - | B-3, D1-3, D2-3, R-3 | - |

| 9 | B-5, D1-5, D2-5, R-5 | - | B-3, D1-3, D2-3, R-3 | - |

| 10 | B-5, D1-5, D2-5 | R-5 | B-3, D1-3, D2-3 | R-3 |

| 11 | B-3, D1-3, D2-3 | R-3 | - | - |

| 12 | B-3, D1-3, D2-3, R-3 | - | B-6, D1-6, D2-6, R-6 | - |

| 13 | B-3, D1-3, D2-3, R-3 | - | B-6, D1-6, D2-6, R-6 | - |

| 14 | B-3, D1-3, D2-3, R-3 | - | B-6, D1-6, D2-6, R-6 | - |

| 15 | B-3, D1-3, D2-3, R-3 | - | B-6, D1-6, D2-6, R-6 | - |

| 16 | B-6, D1-6, D2-6, R-6 | - | B-6, D1-6, D2-6 | R-6 |

| 17 | B-6, D1-6, D2-6, R-6 | - | B-5, D1-5, D2-5, R-5 | - |

| 18 | B-6, D1-6, D2-6, R-6 | - | B-5, D1-5, D2-5, R-5 | - |

| 19 | B-6, D1-6, D2-6, R-6 | - | B-5, D1-5, D2-5, R-5 | - |

| 20 | B-6, D1-6, D2-6 | R-6 | B-5, D1-5, D2-5, R-5 | - |

| 21 | - | - | B-5, D1-5, D2-5 | R-5 |

| 22 | - | - | - | - |

| 23 | - | - | - | - |

| 24 | - | - | - | - |

| 25 | - | - | - | - |

| 26 | - | - | - | - |

| 27 | - | - | - | - |

| 28 | - | - | - | - |

| 29 | - | - | - | - |

| 30 | - | - | - | - |

| 31 | - | - | - | - |

| 32 | - | - | B-7, D1-7, D2-7 | R-7 |

| 33 | B-7, D1-7, D2-7 | R-7 | B-7, D1-7, D2-7 | R-7 |

| 34 | B-7, D1-7, D2-7, R-7 | - | B-7, D1-7, D2-7 | R-7 |

| 35 | B-7, D1-7, D2-7, R-7 | - | B-7, D1-7, D2-7 | R-7 |

| 36 | B-7, D1-7, D2-7, R-7 | - | B-7, D1-7, D2-7 | R-7 |

| 37 | B-7, D1-7, D2-7, R-7 | - | B-2, D1-2, D2-2 | R-2 |

| 38 | B-8, D1-8, D2-8, R-8 | - | B-2, D1-2, D2-2, R-2 | - |

| 39 | B-8, D1-8, D2-8, R-8 | - | B-2, D1-2, D2-2, R-2 | - |

| 40 | B-8, D1-8, D2-8, R-8 | - | B-2, D1-2, D2-2, R-2 | - |

| 41 | B-8, D1-8, D2-8, R-8 | - | B-2, D1-2, D2-2, R-2 | - |

| 42 | B-8, D1-8, D2-8 | R-8 | B-1, D1-1, D2-1, R-1 | - |

| 43 | B-4, D1-4, D2-4, R-4 | - | B-1, D1-1, D2-1, R-1 | - |

| 44 | B-4, D1-4, D2-4, R-4 | - | B-1, D1-1, D2-1, R-1, R-7 | - |

| 45 | B-4, D1-4, D2-4, R-4 | - | B-1, D1-1, D2-1, R-1, R-7 | - |

| 46 | B-4, D1-4, D2-4, R-4 | - | B-1, D1-1, D2-1, R-7 | R-1 |

| 47 | B-4, D1-4, D2-4 | R-4 | R-7 | - |

| 48 | B-1, D1-1, D2-1, R-1 | - | B-8, D1-8, D2-8, R-8 | - |

| 49 | B-1, D1-1, D2-1, R-1 | - | B-8, D1-8, D2-8, R-8 | - |

| 50 | B-1, D1-1, D2-1, R-1 | - | B-8, D1-8, D2-8, R-8 | - |

| 51 | B-1, D1-1, D2-1, R-1 | - | B-8, D1-8, D2-8, R-8 | - |

| 52 | B-1, D1-1, D2-1 | R-1 | B-8, D1-8, D2-8 | R-8 |

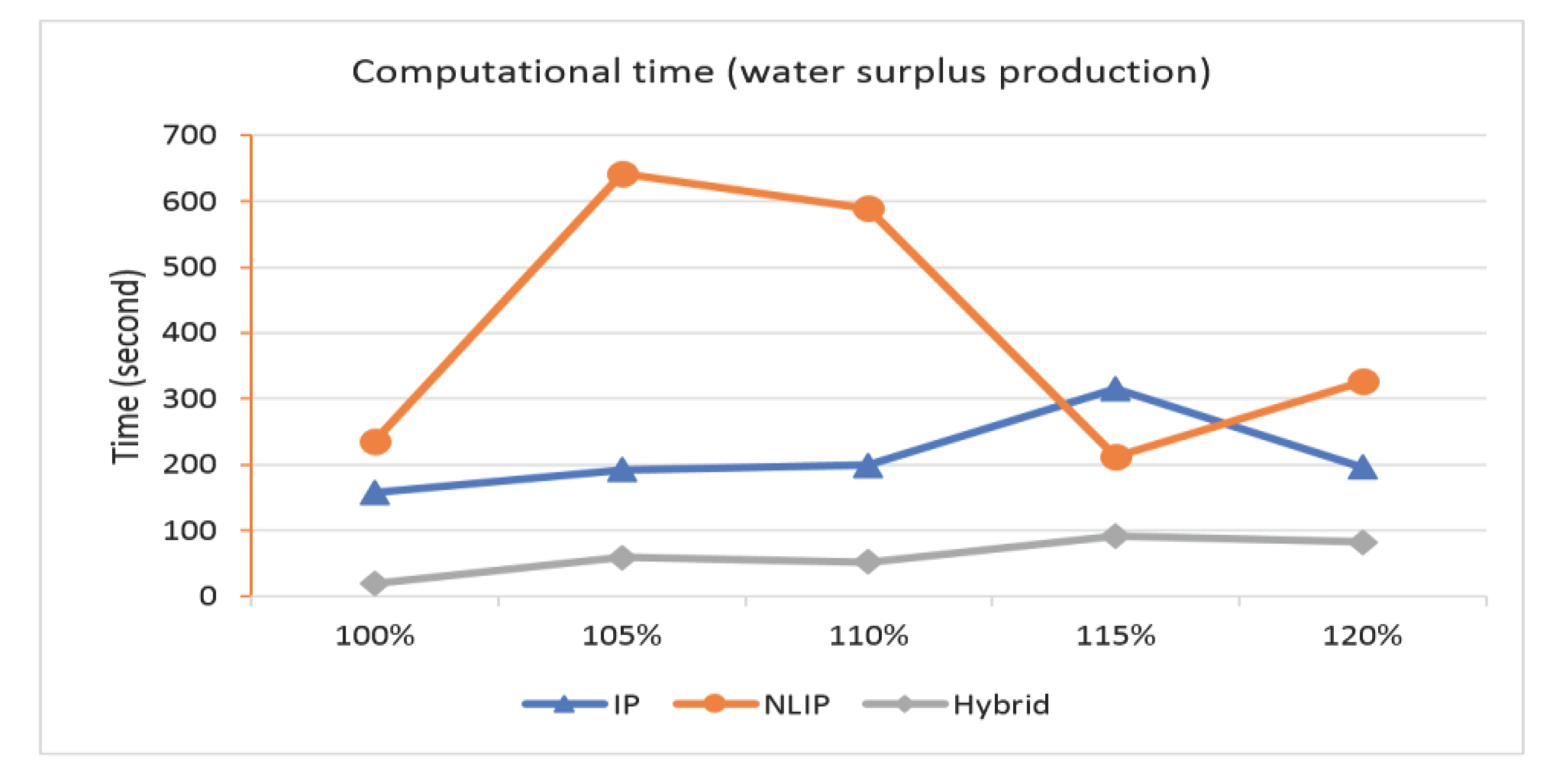

| Water | Min. Gap | Time in second | ||||

| Increased Demand | Distiller | IP | NLIP | Hybrid | ||

| 100% | 100% | 118.1 | 157 | 236 | 20 | |

| 105% | 89.565 | 192 | 642 | 59 | ||

| 110% | 61.03 | 199 | 589 | 52 | ||

| 115% | 32.495 | 315 | 212 | 92 | ||

| 120% | 3.96 | 196 | 326 | 82 | ||

| Average | 211.8 | 401 | 61 | |||

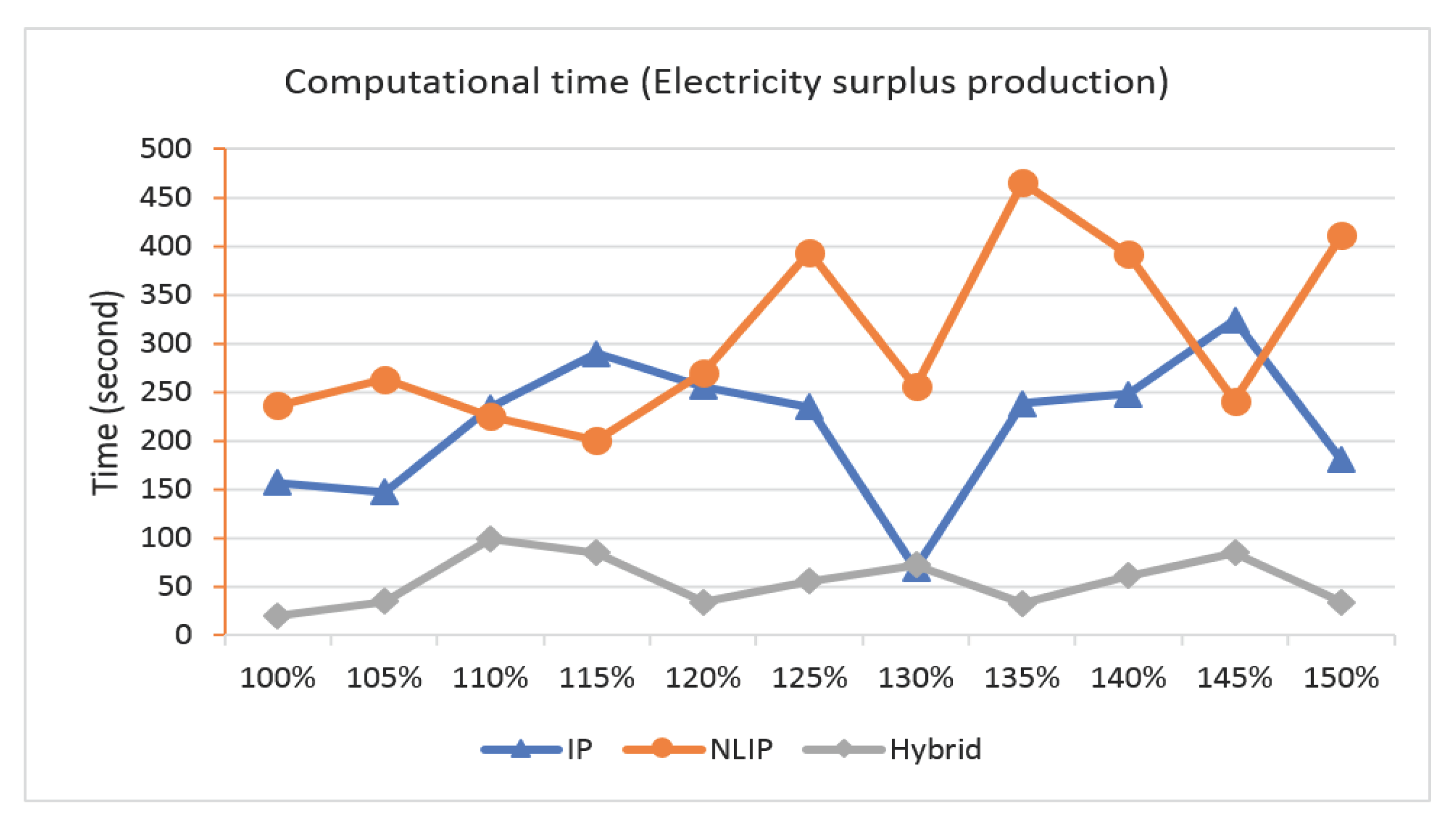

| Electricity | Min. Gap | Time in second | ||||

| Increased Demand | Turbine | IP | NLIP | Hybrid | ||

| 100% | 100% | 124426 | 157 | 236 | 20 | |

| 105% | 114183 | 147 | 263 | 35 | ||

| 110% | 103941 | 234 | 225 | 99 | ||

| 115% | 93697.9 | 290 | 200 | 85 | ||

| 120% | 83455.2 | 256 | 270 | 34 | ||

| 125% | 73212.5 | 235 | 394 | 56 | ||

| 130% | 62969.8 | 69 | 256 | 72 | ||

| 135% | 52727.1 | 238 | 466 | 33 | ||

| 140% | 42484.4 | 248 | 392 | 61 | ||

| 145% | 32241.7 | 324 | 241 | 85 | ||

| 150% | 21999 | 181 | 411 | 34 | ||

| Average | 216.3 | 304.9 | 55.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).