Submitted:

28 March 2024

Posted:

29 March 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Experimental Design

2.2. Measurement of Germination Rate, Shoot Length and Fresh Weight

2.3. Measurement of Physiological and Biochemical Indices

2.4. Transcriptomics Analysis

2.5. Functional Annotation and Enrichment Analysis of Differential Genes

2.6. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis

3. Result

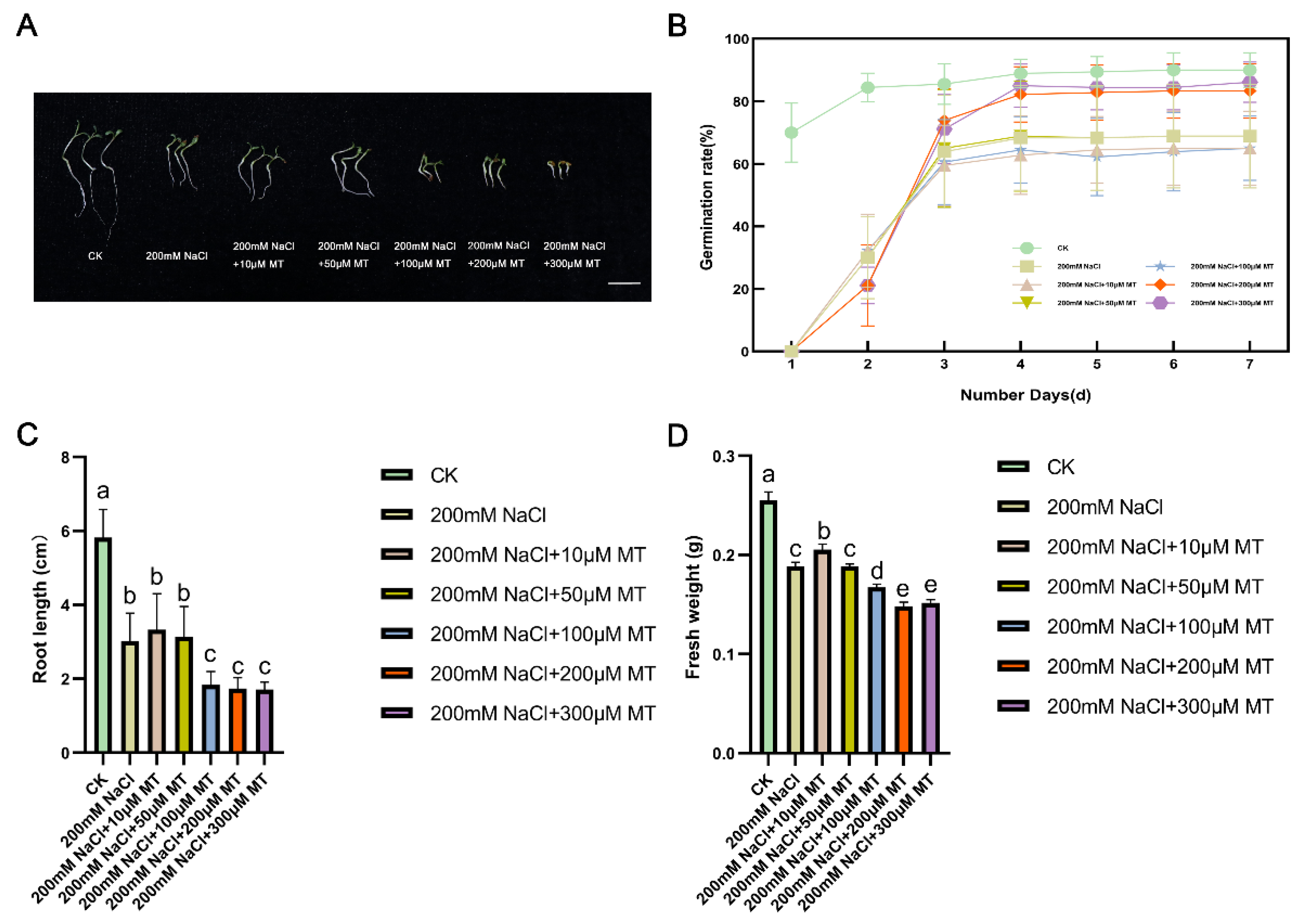

3.1. Effect of MT on the Growth of NaCl-Stressed Alfalfa Plants

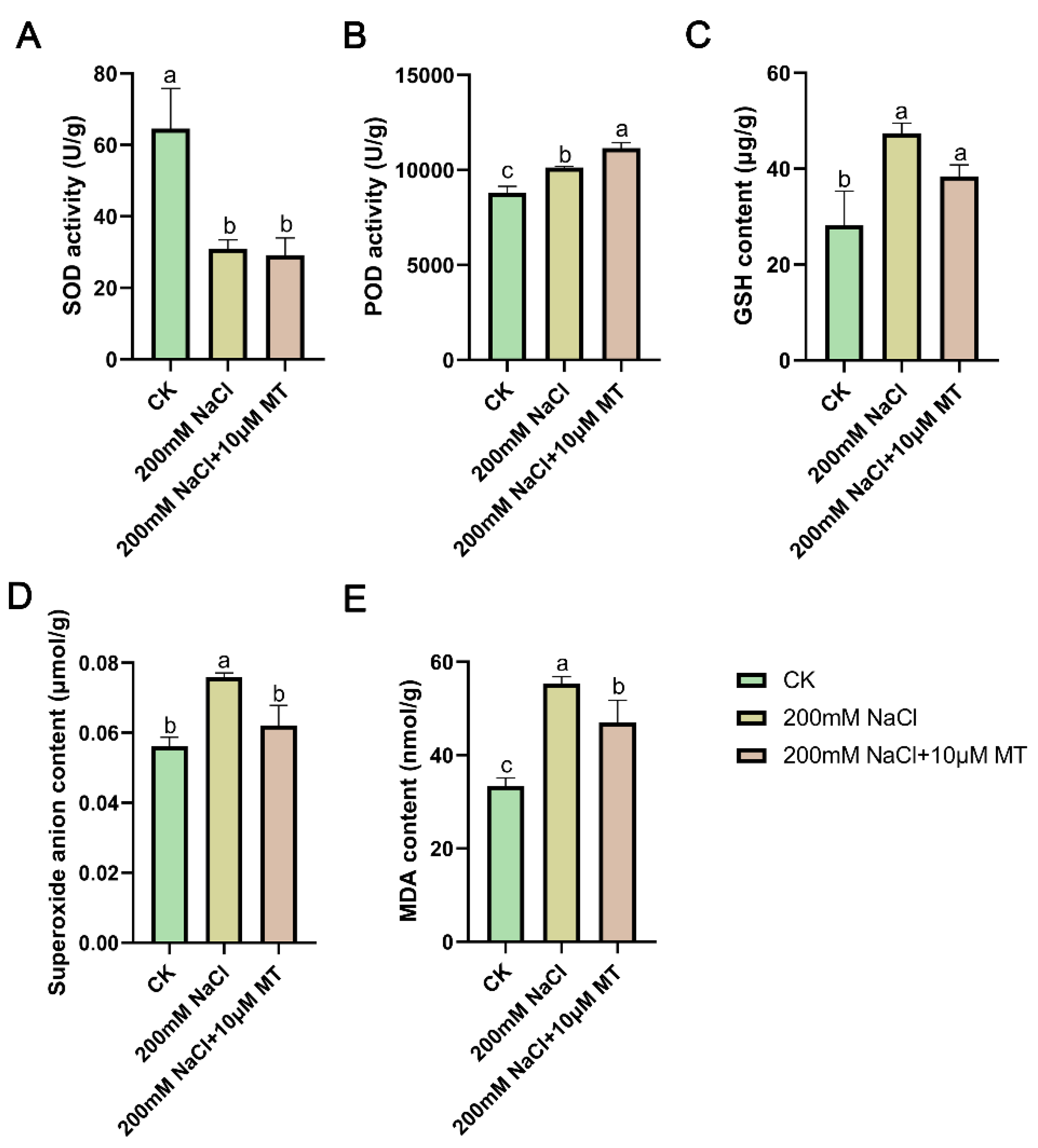

3.2. Changes of Indicators in Oxidation System

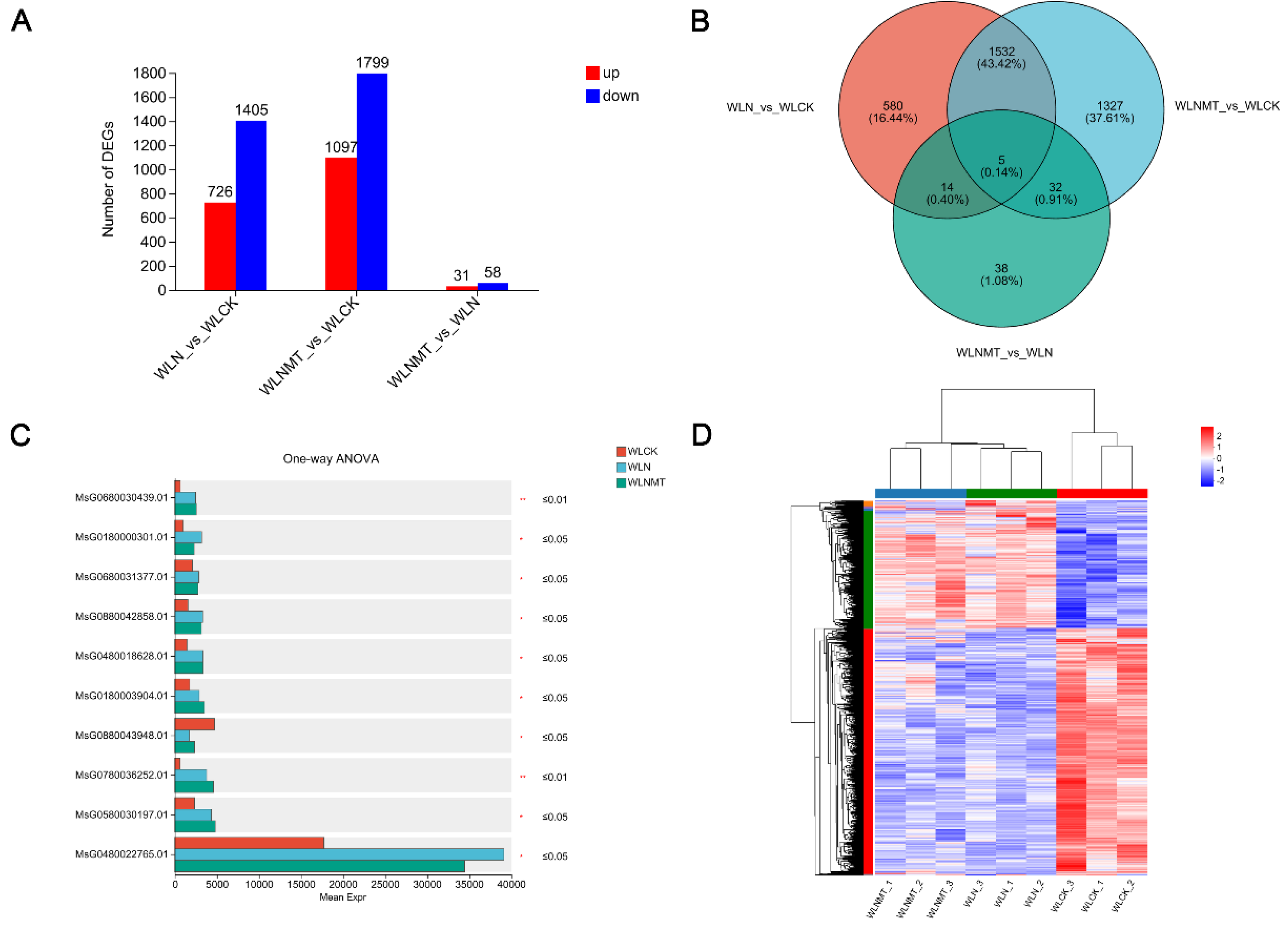

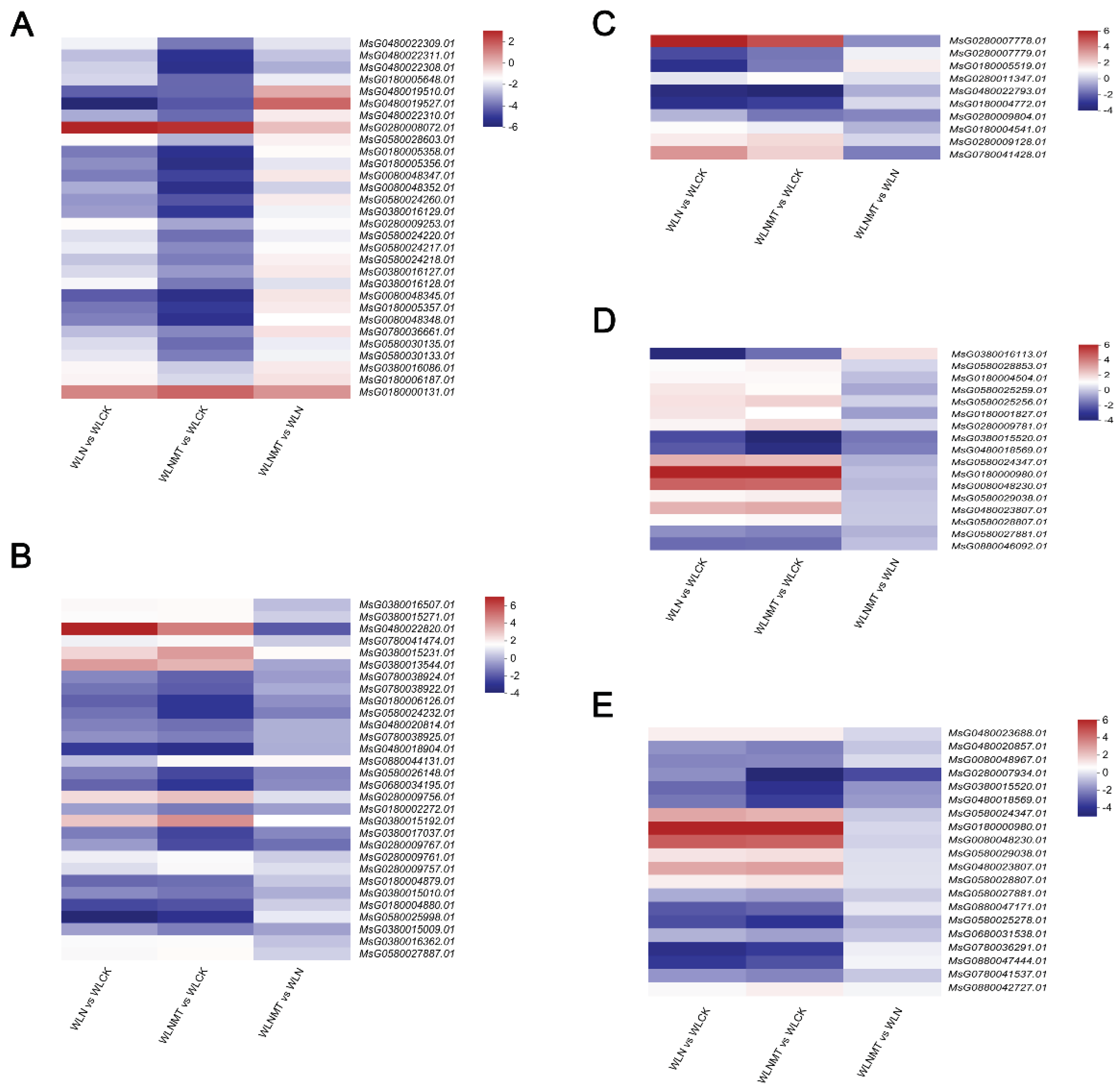

3.3. Differential Expression Analysis and Cluster Analysis of Genes in Alfalfa Seedlings

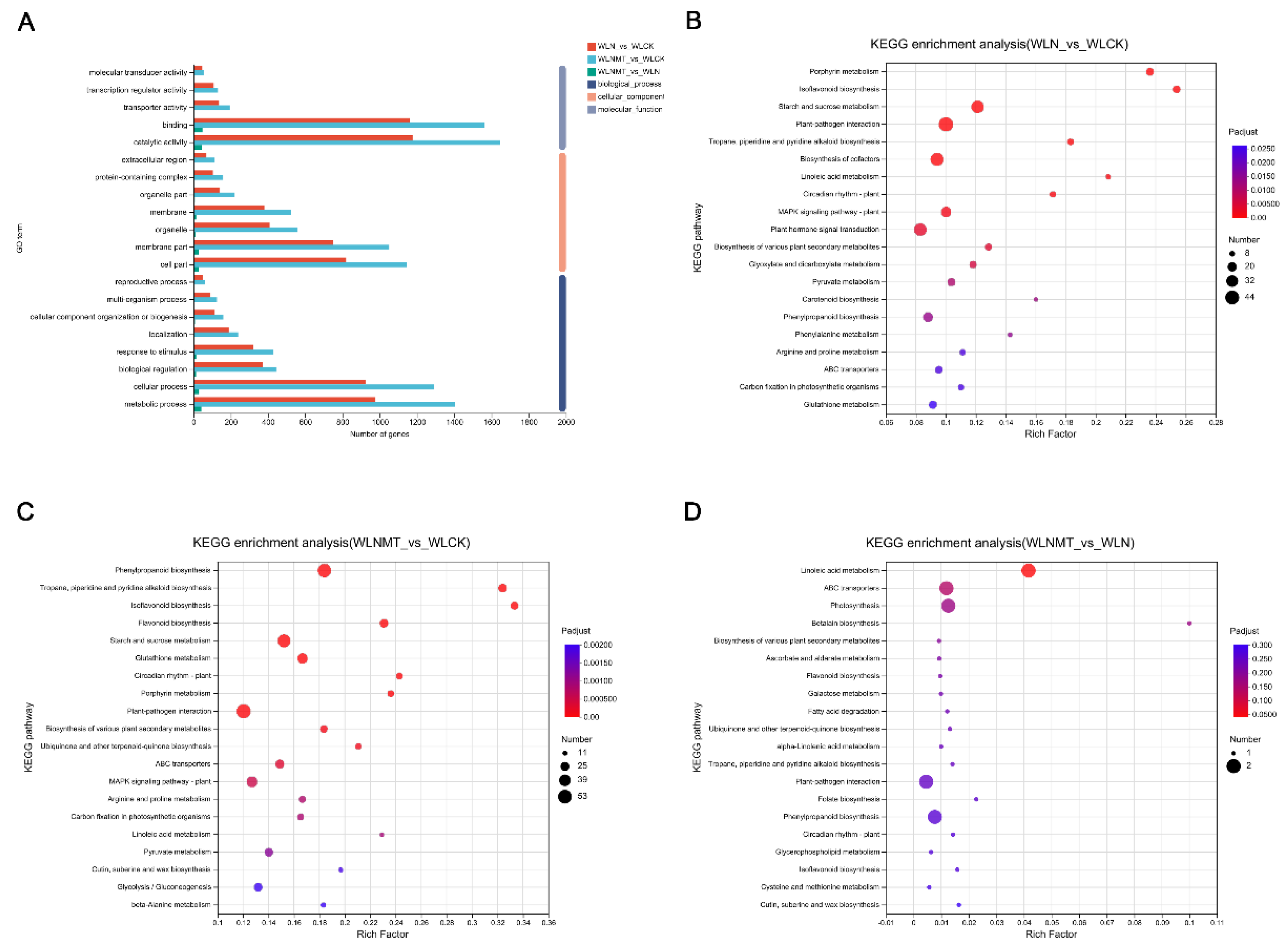

3.4. GO Annotation Analysis and KEGG Enrichment Pathway Analysis of DEGs

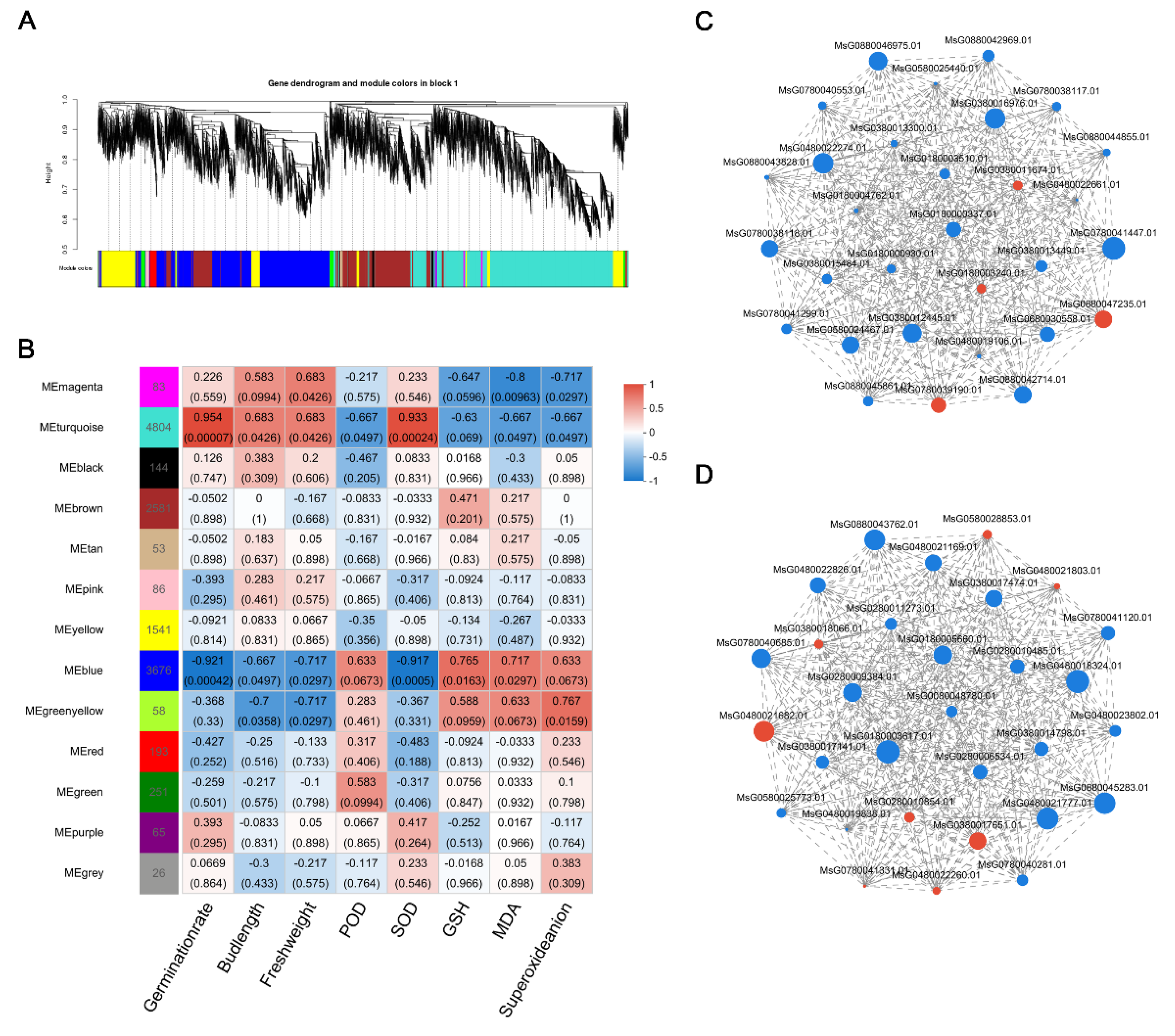

3.5. Gene Co-Expression Networks

4. Discussion

4.1. Biosynthesis of Flavonoid Compounds

4.2. Glutathione Metabolism Pathway

4.2. Plant Hormone Synthesis and Signal Transduction

4.3. MAPK Signalling Pathway

4.4. ABC Transporters

4.5. Biosynthesis of Physiological Regulatory Substances

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morton, M. J. L.; Awlia, M.; Al-Tamimi, N.; Saade, S.; Pailles, Y.; Negrão, S.; Tester, M. Salt stress under the scalpel – dissecting the genetics of salt tolerance. Plant J, 2019, 97(1), 148–163. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Akbar, A.; Parveen, A.; Rasheed, R.; Hussain, I.; Iqbal, M. Phenological application of selenium differentially improves growth, oxidative defense and ion homeostasis in maize under salinity stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 123, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyerman, SD.; Munns, R.; Fricke, W.; Arsova, B.; Barkla, BJ.; Bose, J.; Bramley, H.; Byrt, C.; Chen, Z.; Colmer, TD.; et al. Energy costs of salinity tolerance in crop plants. New Phytol. 2019, 221(1), 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahab, S.; Suhani, I.; Srivastava, V.; Chauhan, P. S.; Singh, R. P.; Prasad, V. Potential risk assessment of soil salinity to agroecosystem sustainability: current status and management strategies. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 764, 144164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baena, G.; Xia, L.; Waghmare, S.; Yu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Blatt, M. R.; Zhang, B.; Karnik, R. Arabidopsis SNARE SYP132 impacts on PIP2;1 trafficking and function in salinity stress. Plant J. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, L.; Tang, B.; Zhang, H.; Hao, F.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Allele-aware chromosome-level genome assembly and efficient transgene-free genome editing for the autotetraploid cultivated alfalfa. Nat. 2020, 11, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radović, J.; Sokolović, D.; Marković, J. J. B. A. H. Alfalfa-most important perennial forage legume in animal husbandry. Biotechnol. Anim. Husb. 2009, 25, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, F.; Rafiei, F.; Shabani, L.; & Shiran, B.; & Shiran, B. Differential expression pattern of transcription factors across annual Medicago genotypes in response to salinity stress. Biol. Plant. 2017, 61(2), 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Wei, C.; Zhang, Y.; Long, R.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Kang, J.; Chen, L. Genome-wide association analysis coupled with transcriptome analysis reveals candidate genes related to salt stress in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 826584. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, T.; Zhao, C.; Li, L.; Chen, M. The role of melatonin in salt stress responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20(7), 1735–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z. Plant abiotic stress: New insights into the factors that activate and modulate plant responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63(3), 429–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Yin, Q.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Niu, J.; Zhang, J.; Fan, K. Exogenous Silicon Enhanced Salt Resistance by Maintaining K+/Na+ Homeostasis and Antioxidant Performance in Alfalfa Leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2020,11, 1183. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, N.; Li, X.; Dong, Y.; Yao, N.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; et al. Overexpression of vacuolar proton pump ATPase (V-H+-ATPase) subunits B, C and H confers tolerance to salt and saline-alkali stresses in transgenic alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 2279–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Xiao, J.; Huang, M.; Zhuo, L.; Zhang, D. Enhancement of salt tolerance of alfalfa: Physiological and molecular responses of transgenic alfalfa plants expressing Syntrichia caninervis-derived ScABI3. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024, 207, 108335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Yi, D.; Li, F.; Wen, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. MsWRKY33 increases alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) salt stress tolerance through altering the ROS scavenger via activating MsERF5 transcription. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46(12), 3887-3901. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. J.; Wang, T. Plant Sci. 2015, 234, 110–118. [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Debnath, S.; Sun, L.; Flanagan, A.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Wen, J.; Wang, Z. Y. From model to crop: functional characterization of SPL8 in M. truncatula led to genetic improvement of biomass yield and abiotic stress tolerance in alfalfa. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16(4), 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, H.; Wang, T.; Liu, H.; Tian, D.; Zhang, Y. Melatonin Application Improves Salt Tolerance of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) by Enhancing Antioxidant Capacity. Plants. 2020, 9(2), 220. [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, M.; Saleem, M. F.; Ullah, N.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Shahid, M. R.; Alamri, S. A.; Alyemeni, M. N.; Ahmad, P. Exogenously applied growth regulators protect the cotton crop from heat-induced injury by modulating plant defense mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8(1), 17086.

- Park, S.; Back, K. Melatonin promotes seminal root elongation and root growth in transgenic rice after germination. J. Pineal. Res. 2012, 53(4), 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.Y.; Xin, L.F.; Li, Z.; Zheng, H.F.; Mao, J.; Yang, Q.H. Physiology and transcriptome analyses reveal a protective effect of the radical scavenger melatonin in aging maize seeds. Free Radical Res. 2018, 52, 1094–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnao, M. B.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Functions of melatonin in plants: a review. J. Pineal Res. 2015, 59(2), 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. E.; Mao, J. J.; Sun, L. Q.; Huang, B.; Ding, C. B.; Gu, Y.; Liao, J. Q.; Hu, C.; Zhang, Z. W.; Yuan, S.; et al. Exogenous melatonin enhances salt stress tolerance in maize seedlings by improving antioxidant and photosynthetic capacity. Physiol. Plant. 2018, 164, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Beneficial Effects of Exogenous Melatonin on Overcoming Salt Stress in Sugar Beets (Beta vulgaris L.). Plants Basel. 2021, 10, 886–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, A.; Rafudeen, M.; Gomaa, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Exogenous melatonin enhances the reactive oxygen species metabolism, antioxidant defense-related gene expression, and photosynthetic capacity of Phaseolus vulgaris L. to confer salt stress tolerance. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Ding, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Xu, X.; Wei, H.; Li, G. Exogenous melatonin alleviates salt stress by improving leaf photosynthesis in rice seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 163, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H. J.; Zhang, N.; Yang, R. C.; Wang, L.; Sun, Q. Q.; Li, D. B.; Cao, Y. Y.; Weeda, S.; Zhao, B.; Ren, S.; et al. Melatonin promotes seed germination under high salinity by regulating antioxidant systems, ABA and GA₄ interaction in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57(3), 269–279.

- Xu, L.; Yue, Q.; Bian, F.; Sun, H.; Zhai, H.; Yao, Y. Melatonin Enhances Phenolics Accumulation Partially via Ethylene Signaling and Resulted in High Antioxidant Capacity in Grape Berries. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Gong, B.; Sun, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Wei, M.; Yang, F.; Li, Y.; Shi, Q. Promoting Roles of Melatonin in Adventitious Root Development of Solanum lycopersicum L. by Regulating Auxin and Nitric Oxide Signaling. Front Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnao, M. B.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Melatonin and its relationship to plant hormones. Ann. Bot. 2018, 121(2), 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu Z, Lee B. Friends or foes: new insights in jasmonate and ethylene co-actions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56(3), 414-420. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chang, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Gu, X.; Wei, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X. Exogenous Melatonin Confers Salt Stress Tolerance to Watermelon by Improving Photosynthesis and Redox Homeostasis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, P.; Wei, Z.; Liang, D.; Liu, C.; Yin, L.; Jia, D.; Fu, M.; Ma, F. The mitigation effects of exogenous melatonin on salinity-induced stress in Malus hupehensis. J. Pineal Res. 2012, 53(3), 298–306.

- Mukherjee, S.; David, A.; Yadav, S.; Baluška, F.; Bhatla, S. C. Salt stress-induced seedling growth inhibition coincides with differential distribution of serotonin and melatonin in sunflower seedling roots and cotyledons. Physiol. Plant. 2014, 152, 714–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018, 34(17), i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 2015, 12(4), 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Du, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, T. The Chromosome-Level Genome Sequence of the Autotetraploid Alfalfa and Resequencing of Core Germplasms Provide Genomic Resources for Alfalfa Research. Mol. Plant. 2020, 13(9), 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M. I., Huber, W., Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15(12), 550. [CrossRef]

- Klopfenstein, D. V.; Zhang, L.; Pedersen, B. S.; Ramírez, F.; Warwick Vesztrocy, A.; Naldi, A.; Mungall, C. J.; Yunes, J. M.; Botvinnik, O.; Weigel, M.; et al. GOATOOLS: A Python library for Gene Ontology analyses. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8(1), 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C. A.; Blake, J. A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J. M.; Davis, A. P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S. S.; Eppig, J. T.; et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25(1), 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gene Ontology Consortium, Aleksander, S. A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J. M.; Drabkin, H. J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N. L.; Hill, D. P.; et al. The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics, 2023, 224(1), iyad031. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1), 27-30. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 2019, 28(11), 1947–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. ; KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D587–D592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, J. L.; Luo, X. G.; Han, M. W.; Zhao, S. P.; Zhu, Y. Analysis of the biodegradation and phytotoxicity mechanism of TNT, RDX, HMX in alfalfa (Medicago sativa). CHEMOSPHERE. 2021, 281, 130842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Jiang, L.; Chen, Y.; Shu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Guo, C. Deep-sequencing transcriptome analysis of field-grown Medicago sativa l. crown buds acclimated to freezing stress. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 2016, 16(5), 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xia, F.; Wang, M.; Mao, P. Physiological and proteomic analysis reveals the impact of boron deficiency and surplus on alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) reproductive organs. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 214, 112083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Xu, X.; Wang, W.; Zhao, L.; Ma, D.; Xie, Y. Comparative analysis of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) seedling transcriptomes reveals genotype-specific drought tolerance mechanisms. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Lu, X.; Zhao, B.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J. Integrative analysis of transcriptome and metabolome reveal mechanism of tolerance to salt stress in oat (Avena sativa L.). Plant Physiol. biochem. 2021, 160, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtari, F.; Rafiei, F.; Shabani, L.; Shiran, B. Differential expression pattern of transcription factors across annual Medicago genotypes in response to salinity stress. Biol. Plantarum. 2017, 61(2), 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, W. J.; Vu, T. T.; Jeong, C. Y.; Hong, S. W.; Lee, H. High accumulation of anthocyanins via the ectopic expression of AtDFR confers significant salt stress tolerance in Brassica napus l. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36(8), 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S. S.; Anjum, N. A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Gill, R.; Trivedi, D. K.; Ahmad, I.; Pereira, E.; Tuteja, N. Glutathione and glutathione reductase: a boon in disguise for plant abiotic stress defense operations. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2013, 70, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinemer, P.; Dirr, H. W.; Ladenstein, R.; Huber, R.; Lo Bello, M.; Federici, G.; Parker, M. W. Three-dimensional structure of class π glutathione S-transferase from human placenta in complex with S-hexylglutathione at 2.8 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1992, 227(1), 214–226. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Du, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Huang, J.; Jiang, J. Effects of Exogenous Potassium (K) Application on the Antioxidant Enzymes Activities in Leaves of Tamarix ramosissima under NaCl Stress. Genes, 2022, 13(9), 1507. [CrossRef]

- Waadt, R.; Seller, C. A.; Hsu, P.-K.; Takahashi, Y.; Munemasa, S.; Schroeder, J. I. Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Lin, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Chen, M. Phytohormone involved in salt tolerance regulation of elaeagnus angustifolia l. seedlings. J. For. Res. 2019, 24(4), 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, R.; Khan, A. L.; Bilal, S.; Waqas, M.; Kang, S. M.; Lee, I. J. Inoculation of abscisic acid-producing endophytic bacteria enhances salinity stress tolerance in Oryza sativa. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 136, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, G.J.; Bressan, R.A.; Song, C.P.; Zhu, J.K.; Zhao, Y. Abscisic acid dynamics, signaling, and functions in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poór, P.; Borbély, P.; Czékus, Z.; Takács, Z.; Ördög, A.; Popović, B.; Tari, I. Comparison of changes in water status and photosynthetic parameters in wild type and abscisic acid-deficient sitiens mutant of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Rheinlands Ruhm) exposed to sublethal and lethal salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 232, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Raina, S.K.; Sultan, S.M. Arabidopsis MAPK signaling pathways and their cross talks in abiotic stress response. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 700–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teige, M.; Scheikl, E.; Eulgem, T.; Dóczi, R.; Ichimura, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Dangl, J. L.; Hirt, H. The MKK2 pathway mediates cold and salt stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell. 2004, 15(1), 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, K.; AbuQamar, S.; Jarrar, M.; Al-Rajab, A. J.; Trémouillaux-Guiller, J. MAPK cascades and major abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Rep. 2014, 33(8), 1217–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Park, J.; Choi, H.; Burla, B.; Kretzschmar, T.; Lee, Y.; Martinoia, E. Plant ABC Transporters. The arabidopsis book. 2011, 9, e0153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andolfo, G.; Ruocco, M.; Di Donato, A.; Frusciante, L.; Lorito, M.; Scala, F.; Ercolano, M. R. Genetic variability and evolutionary diversification of membrane ABC transporters in plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Bovet, L.; Maeshima, M.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y. The ABC transporter AtPDR8 is a cadmium extrusion pump conferring heavy metal resistance. Plant J. 2007, 50(2), 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, M.; Dittgen, J.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, C.; Hou, B. H.; Molina, A.; Schulze-Lefert, P.; Lipka, V.; Somerville, S. Arabidopsis PEN3/PDR8, an ATP binding cassette transporter, contributes to nonhost resistance to inappropriate pathogens that enter by dire ct penetration. Plant Cell. 2006, 18(3), 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruocco, M.; Ambrosino, P.; Lanzuise, S.; Woo, S. L.; Lorito, M.; Scala, F. Four potato (Solanum tuberosum) ABCG transporters and their expression in response to abiotic factors and Phytophthora infestans infection. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168(18), 2225–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Y.; Niu, T.; Zhang, M.; Fan, C.; Liang, W.; Shu, Y.; Guo, C.; Guo, D.; Bi, Y. GmABCG5, an ATP-binding cassette G transporter gene, is involved in the iron deficiency response in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1289801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Li, JL.; Liu, LN.; Xie, Q.; Sui, N. Photosynthetic Regulation Under Salt Stress and Salt-Tolerance Mechanism of Sweet Sorghum. Front Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Choudhary, KK.; Chaudhary, N.; Gupta, S.; Sahu, M.; Tejaswini, B.; Sarkar, S. Salt stress resilience in plants mediated through osmolyte accumulation and its crosstalk mechanism with phytohormones. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1006617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprasanna, P.; Rai, A. N.; Kumari, P. H.; Kumar, S. A.; Kishor, P. B. K. Modulation of proline: implications in plant stress tolerance and development. CABI. 2014, 68–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M. F. M. R.; Foolad, M. Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 59, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M. N.; Wani, A. S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of proline under changing environments: a review. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, K. Melatonin metabolism, signaling and possible roles in plants. Plant J. 2021, 105(2), 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).