Submitted:

27 March 2024

Posted:

28 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Description and Model Formulation

- Susceptible populations of dogs and humans are recruited at a rate level .

- The rabies infection does not transfer from infected humans to susceptible dogs.

- Rabies transmission from humans to humans was ignored.

- Exposed dogs cannot transfer the rabies disease either to dogs or to humans.

- Giving post-exposed prophylaxis for dogs and humans.

- Giving pre-exposed prophylaxis for dogs and humans.

- For dogs, giving both pre-exposed and post-exposure treatment or prophylaxis.

- The primary way of rabies virus transmission is (i) from infectious dogs to susceptible dogs and (ii) from infectious dogs to susceptible humans.

- Individuals in each compartment have an equal natural death rate.

- All the model parameters are positive quantities.

| Variables and Parameters | Description |

|

|

Susceptible dog populations Exposed dog population Infectious dog population with prodromal phase Infectious dog population with the furious phase Recovered dog population Susceptible human populations Exposed human populations Infectious human populations Recovered human population Dogs annual crop of newborn puppies Prodromal phase dog -to-dog transmission rate Furious phase dog-to-dog transmission rate The incubation period of dog populations Rate of prodromal to furious stage Pre-exposure prophylaxis (vaccine) for dogs Post-exposure prophylaxis (treatment) for dogs The death rate of dogs due to rabies The natural death rate of dogs Loss of immunity in dogs Human annual birth Prodromal phase dog-to-human transmission rate Furious phase dog -to-Human transmission rate The incubation period of human populations Pre-exposure prophylaxis (vaccine) for humans Post-exposure prophylaxis (treatment) for humans The death rate of humans due to rabies Natural death rate of humans Rate of recovery to Susceptible human |

3. Model Analysis

3.1. Positivity

3.2. Boundedness of the Model

3.4. Disease-Free Equilibrium

3.5. Basic Reproduction Number

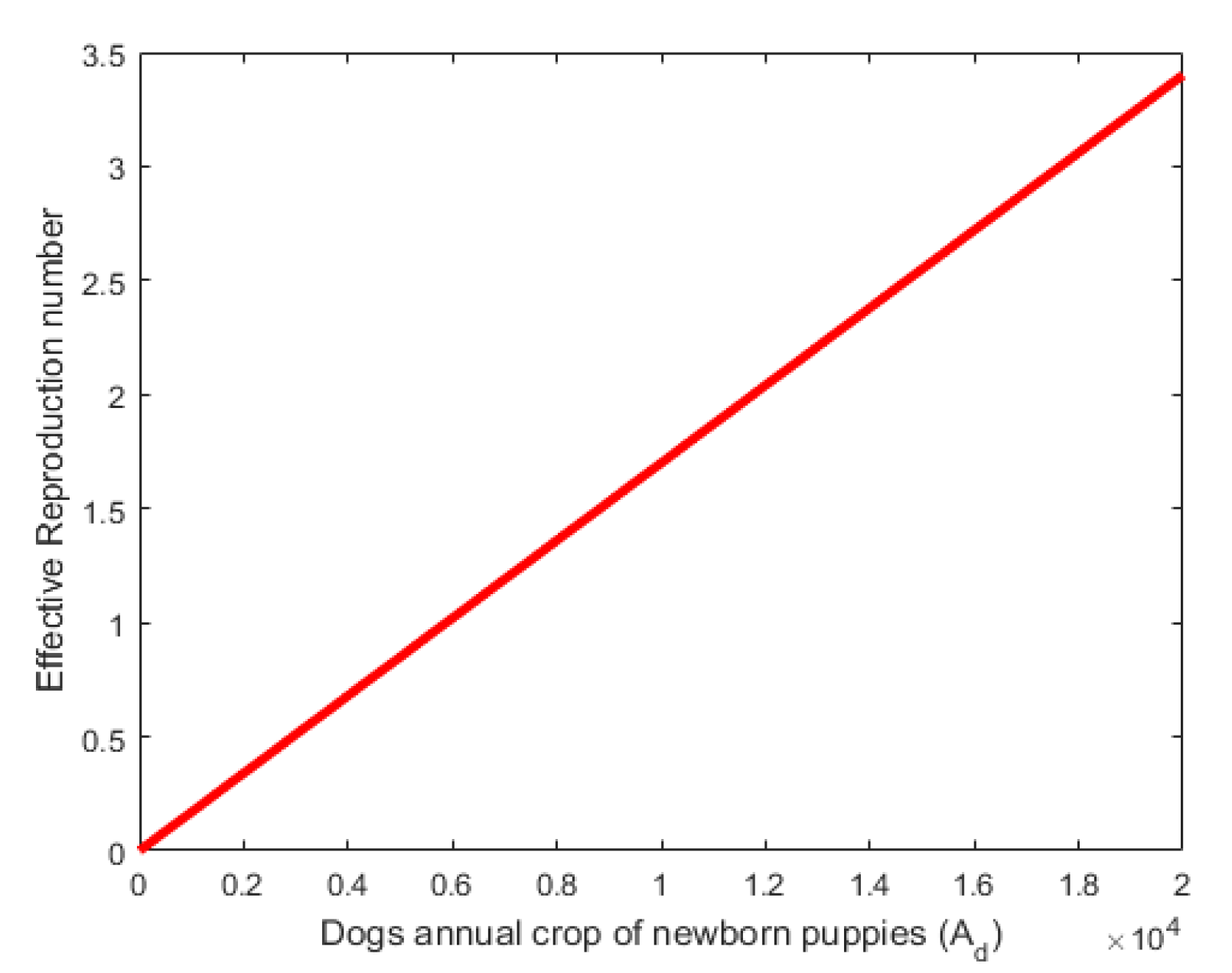

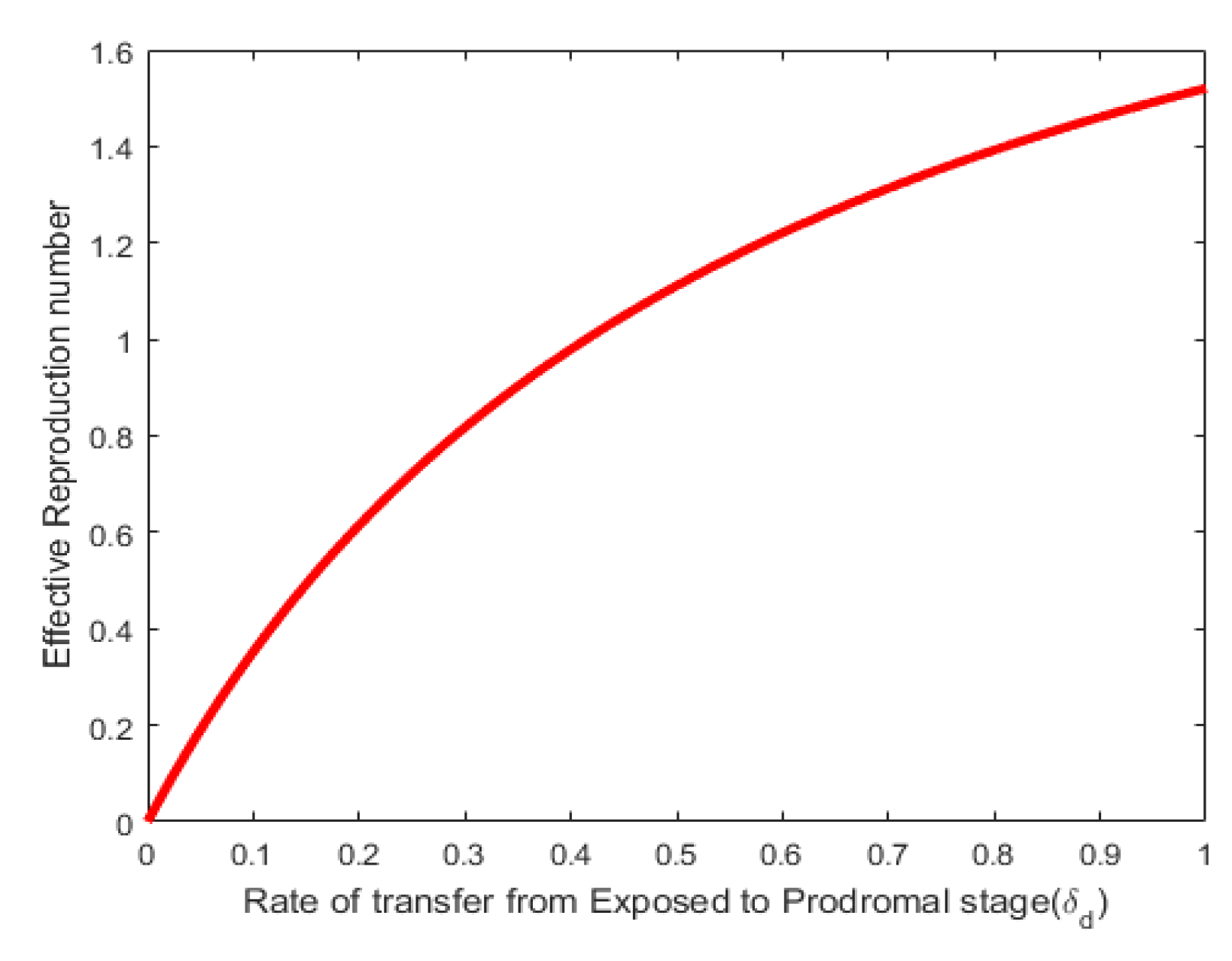

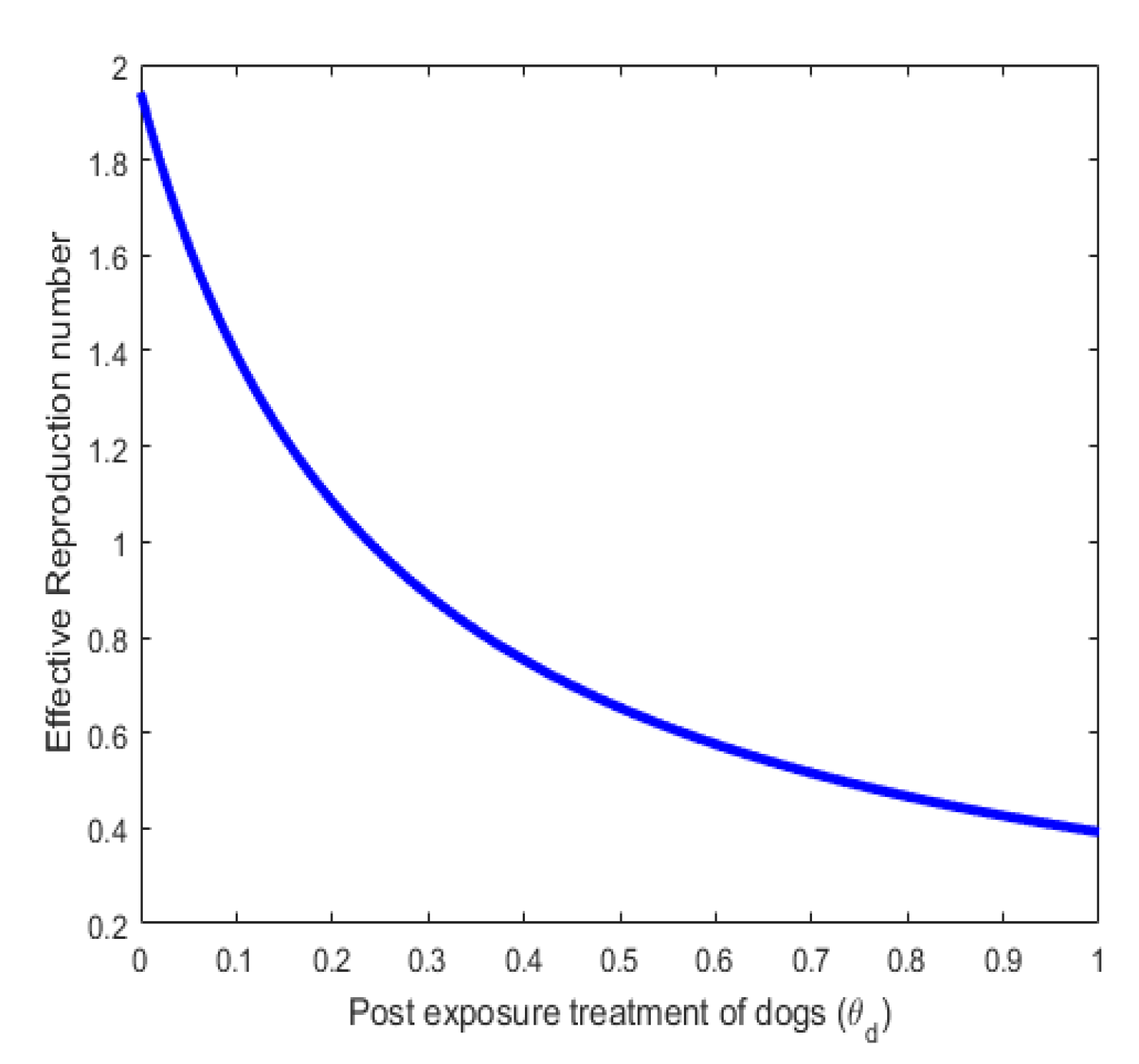

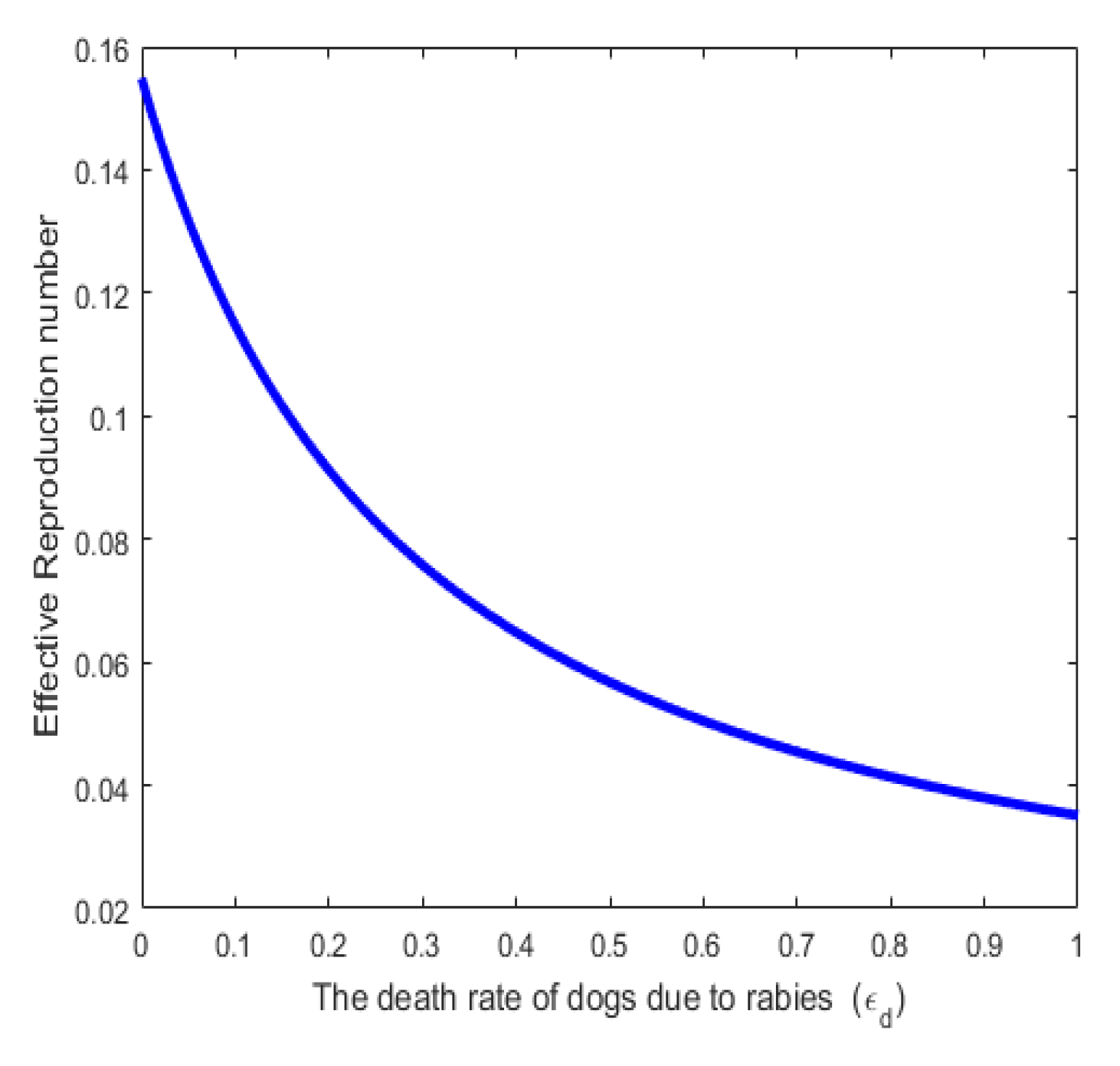

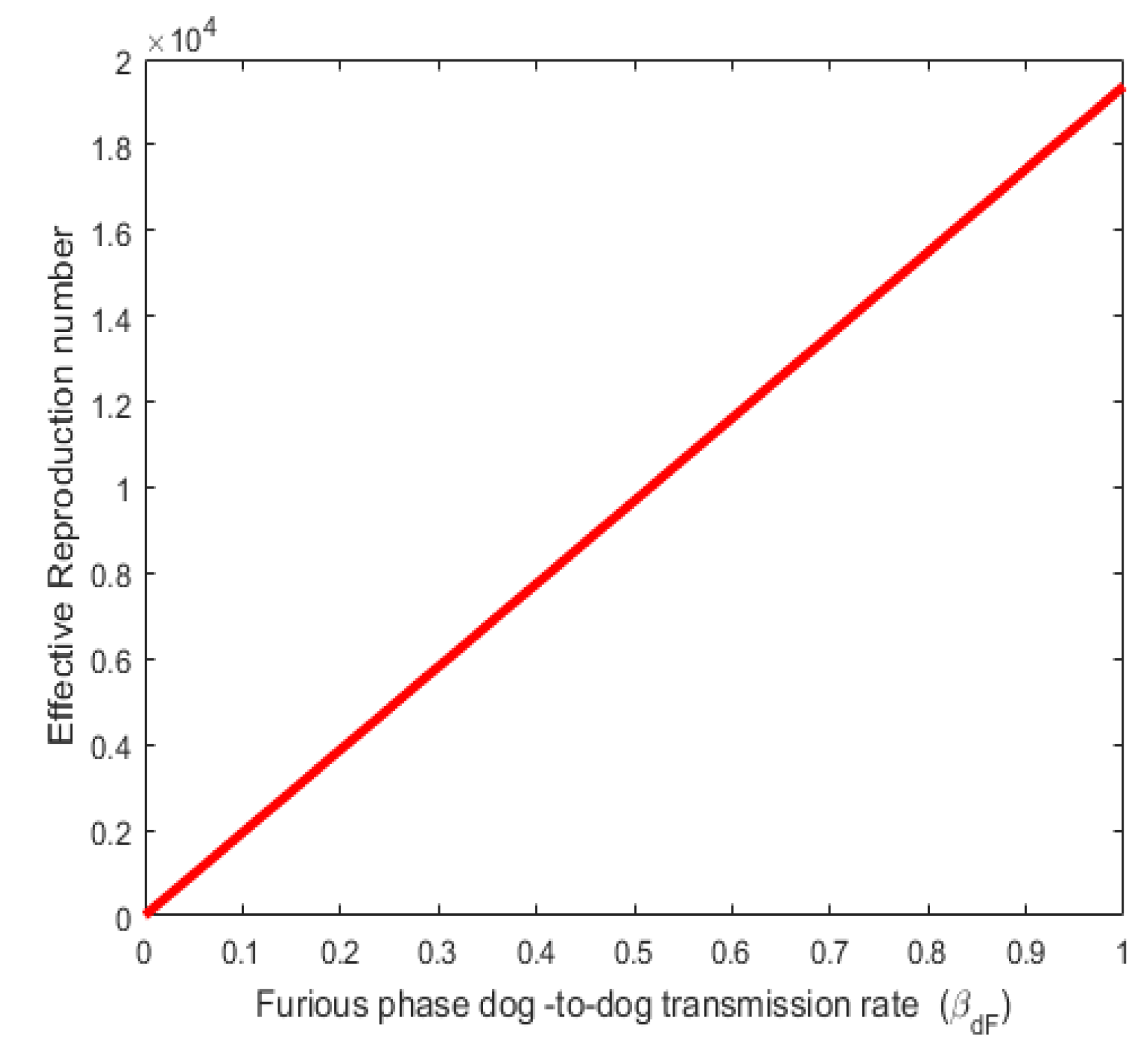

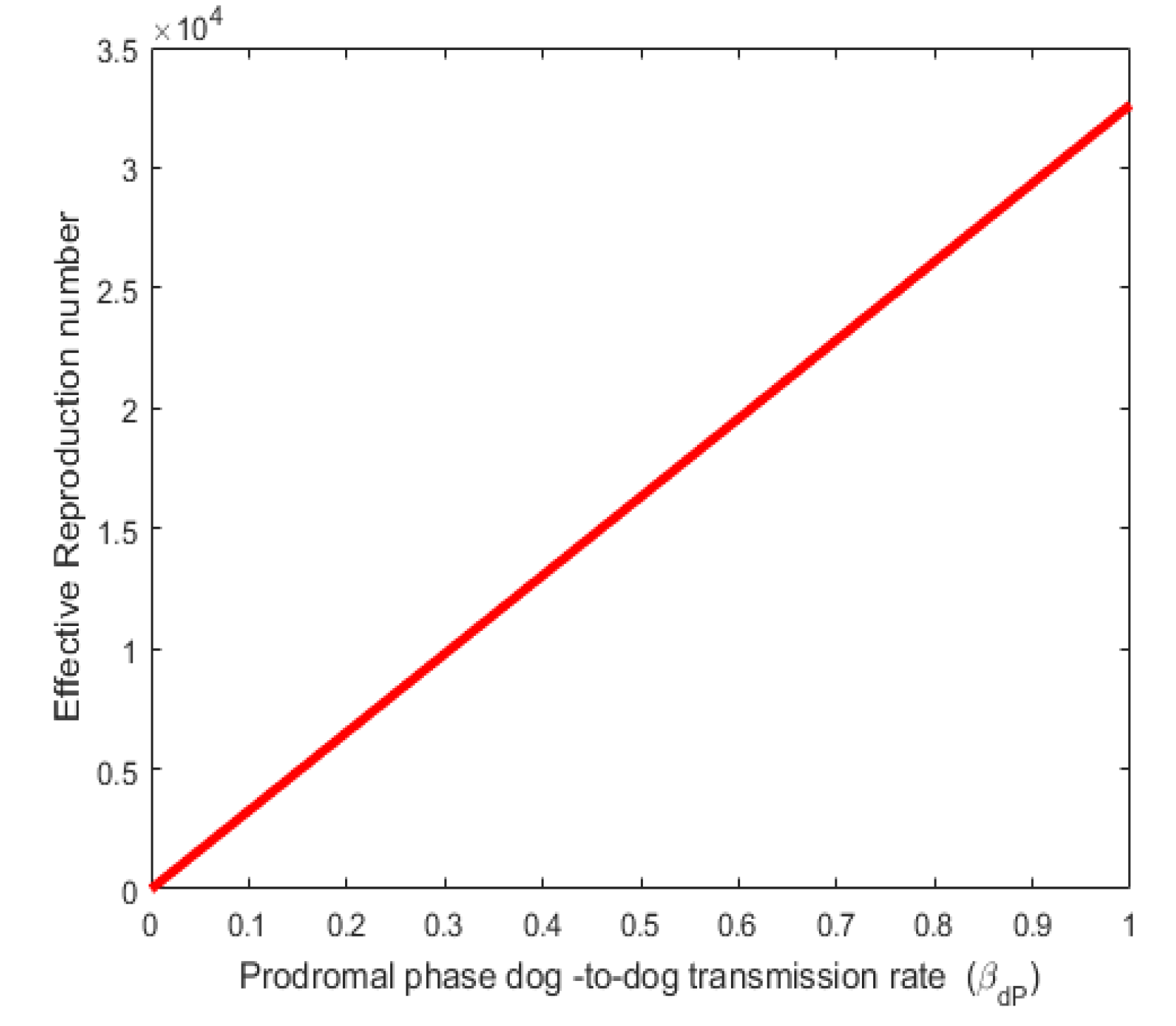

3.5.1. Effective Reproduction Number

3.6. Global Stability of Disease-Free Equilibrium Points

- i.

- B0 should be a matrix whose eigenvalues are real and negative; and

- ii.

- Bz should be a Metzler matrix.

4. Sensitivity Analysis

4.1. Interpretation of Sensitivity Indices

5. Analysis of the Optimal Control Model

5.1. Characterization of the Optimal Control

6. Simulations and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

6.1. Numerical Simulations

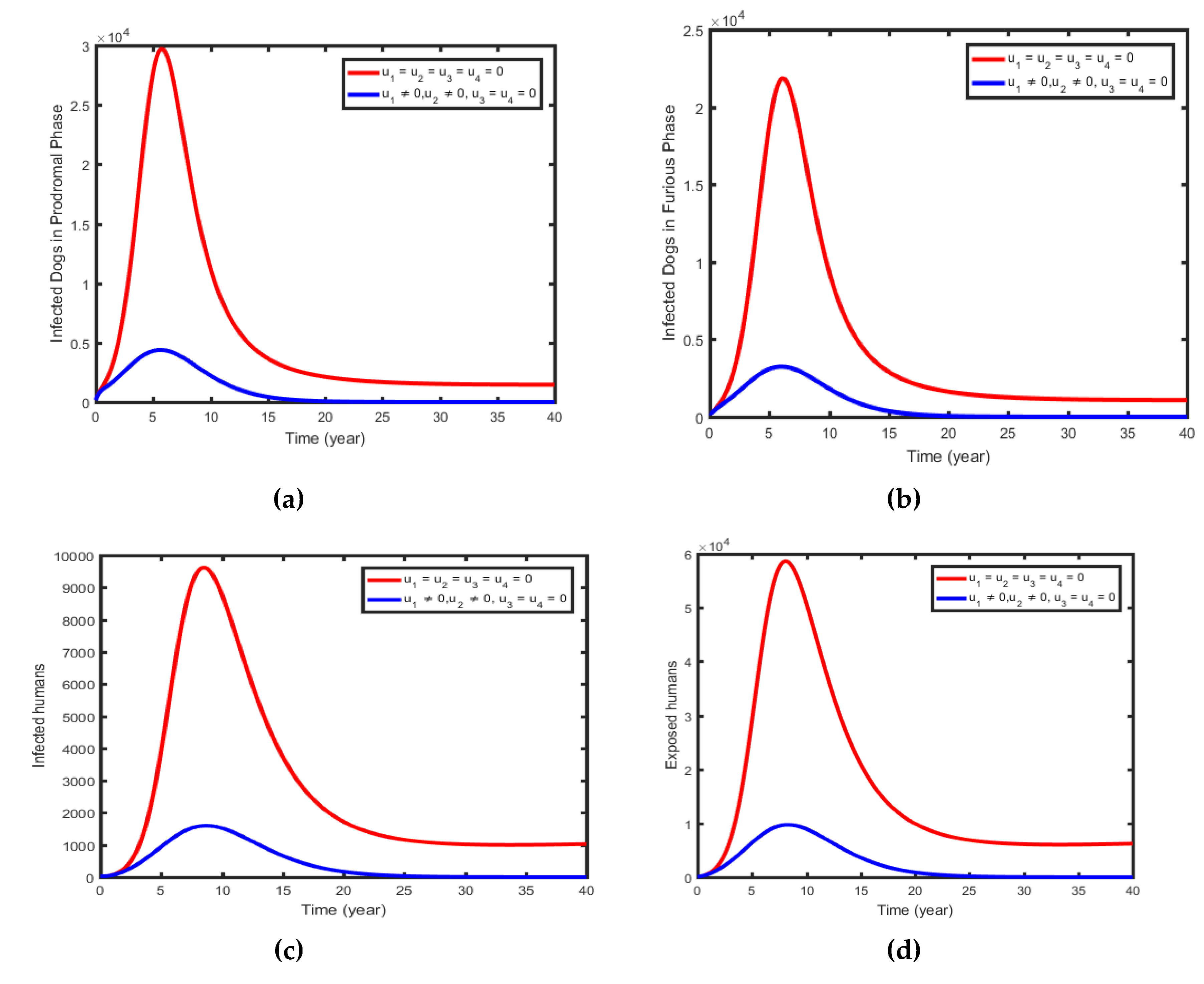

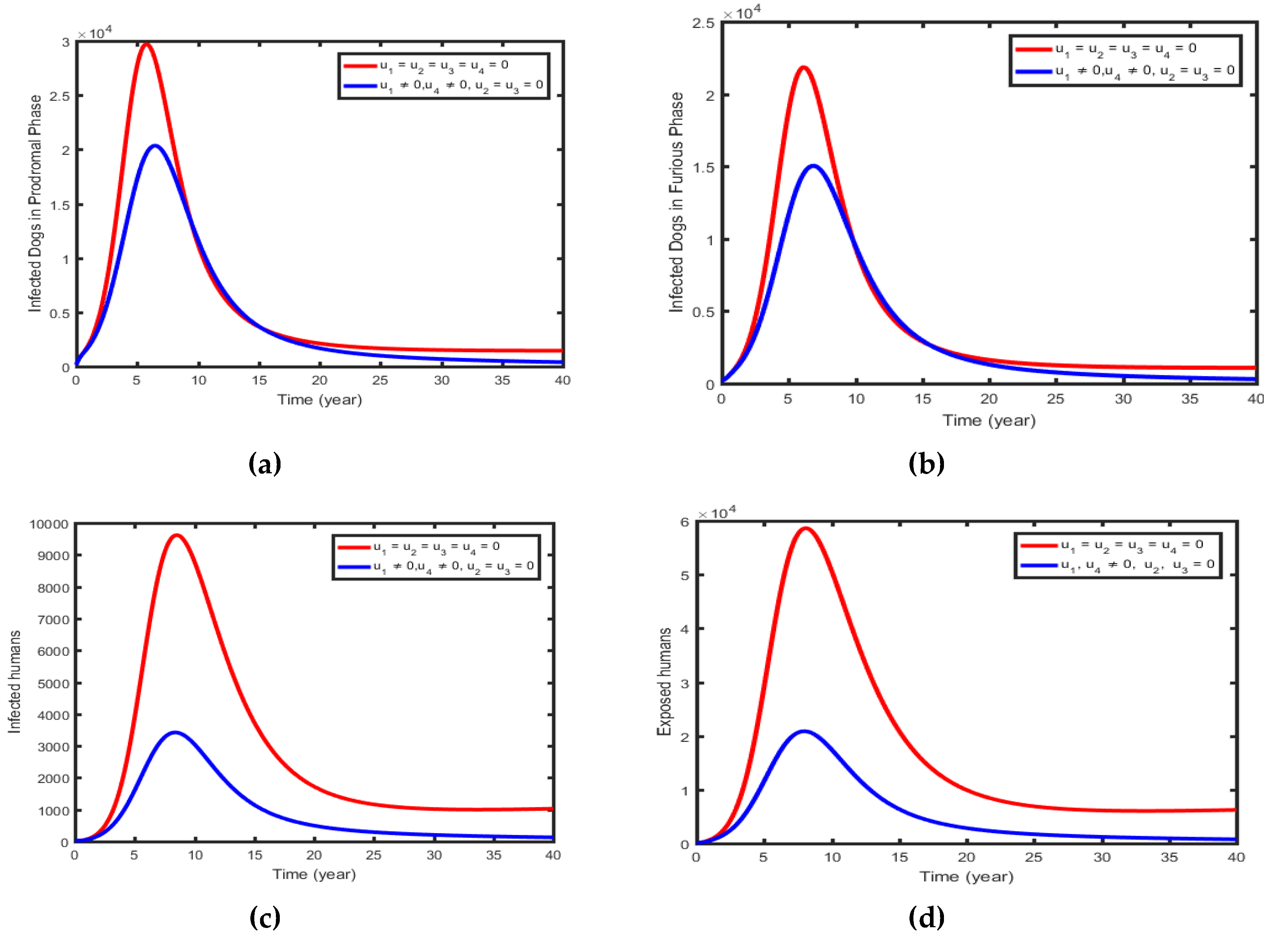

6.1.1. Intervention 1: Optimal Use of Pre-Exposed Prophylaxis and Treating the Exposed Dogs

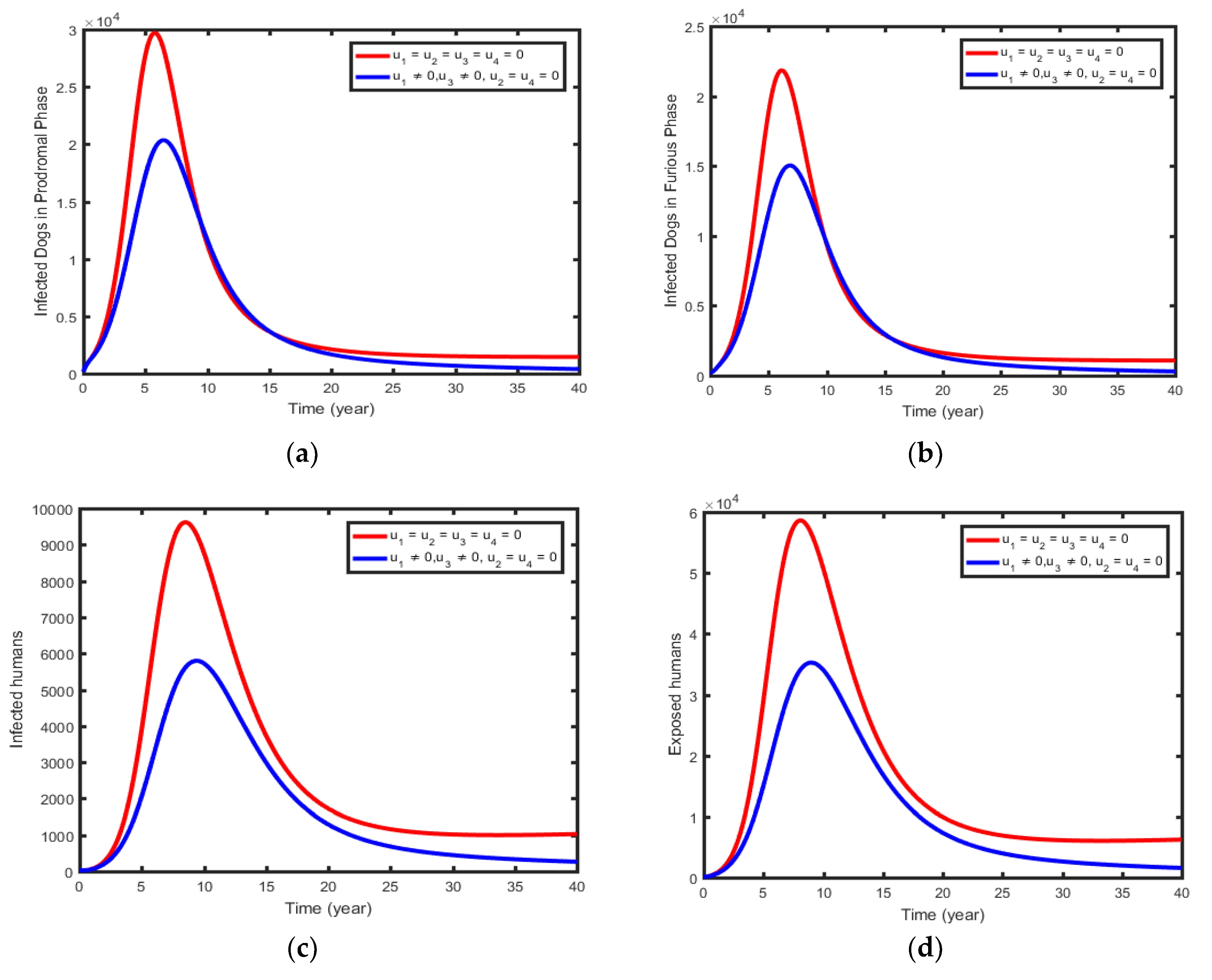

6.1.2. Intervention 2: Optimal Use of Pre-Exposed Prophylaxis Dogs and Pre-Exposed Prophylaxis Humans

6.1.3. Intervention 3: Optimal Use of Dogs Per-Exposed Prophylaxis and Human Post-Exposed Prophylaxis

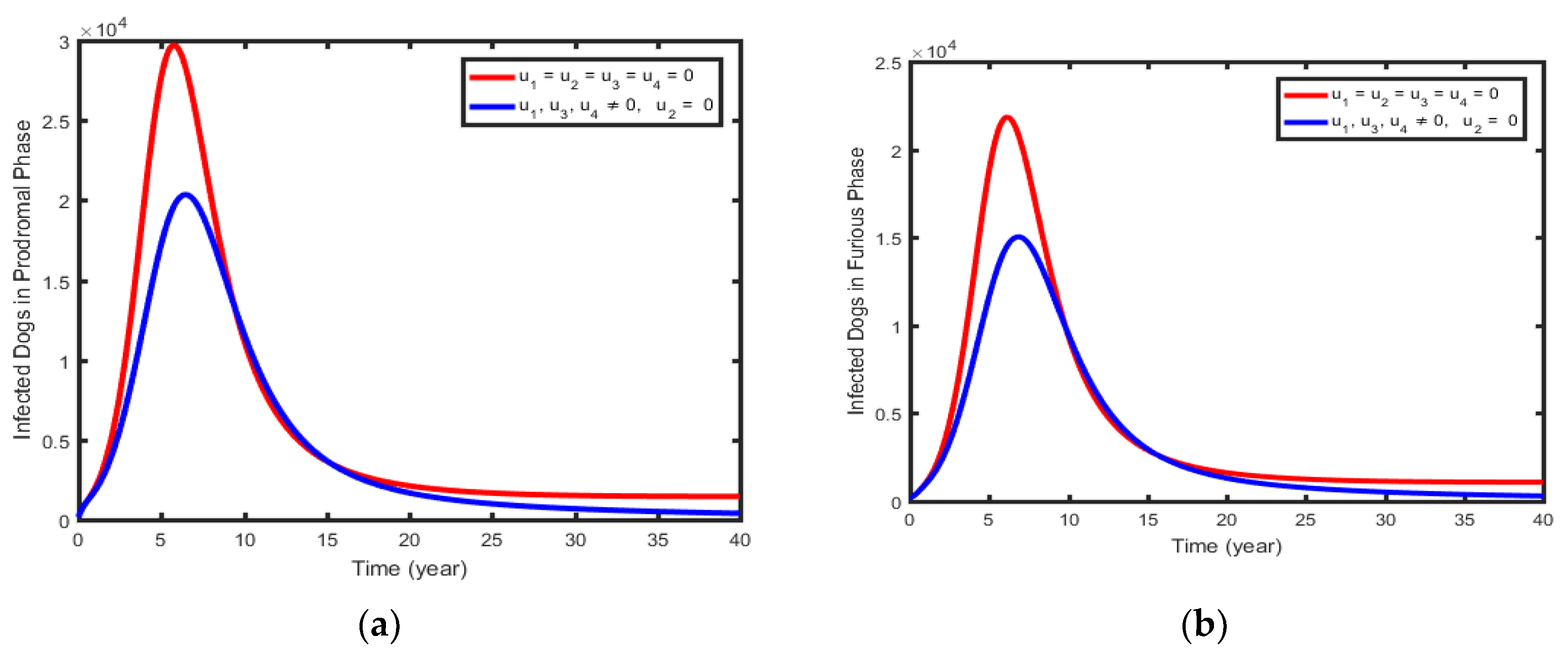

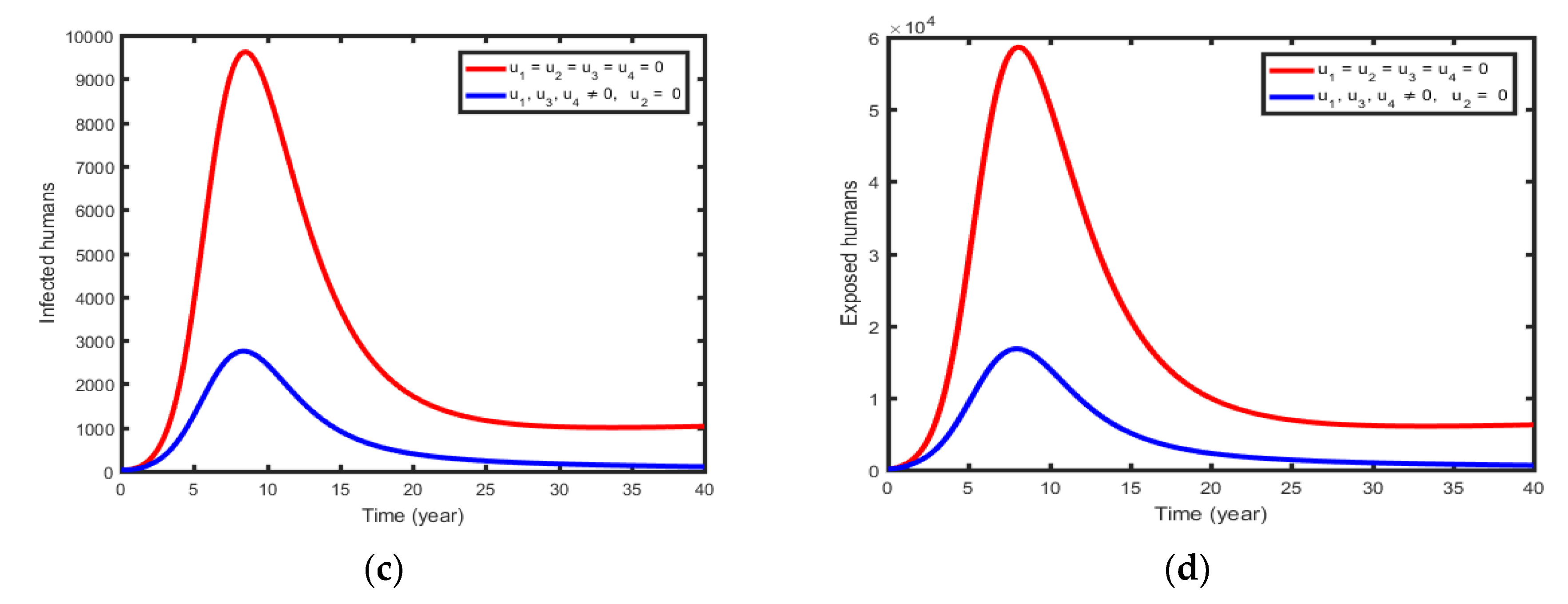

6.1.4. Intervention 4: Optimal Use of Dogs Per-Exposed Prophylaxis, Human’s Per-Exposed Prophylaxis and Human’s Post-Exposed Prophylaxis

6.1.5. Intervention 4: Implementing All Optimal Control Strategies

7. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

8. Conclusion and Recommendations

8.1. Conclusion

8.2. Recommendations

- ✓ The dynamics of rabies transmission should be investigated more thoroughly to develop the optimal control measures.

- ✓ Workshops, seminars, and trainings are examples of educational initiatives that should be conducted to raise awareness regarding rabies transmission and prevention strategies.

- ✓ Dog owners should be encouraged by media coverage to crate their pets rather than allow them free reign on the streets.

- ✓ The government and policymakers should come up with strategies to control and reduce the number of stray dogs. A plan that confines owned dogs to specific locations to restrict the annual crop of newborn puppies and lower the frequency of dog-to-dog transmission.

- ✓ The primary focus of strategy development should be on implementing the most effective control methods, such as vaccinating dog populations, decreasing the annual number of newborn puppies, and removing stray dogs, to reduce the human population and rapidly eliminate diseases.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asfaw, G. B., Abagero, A., Addissie, A., Yalew, A. W., Watere, S. H., Desta, G. B., ... & Deressa, S. G. (2024). Epidemiology of suspected rabies cases in Ethiopia: 2018–2022. One Health Advances, 2(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Shigui Ruan, (2017). Modeling the transmission dynamics and control of rabies in China. Mathematical. Biosciences Volume 286, April, Pages 65-93.

- Musaili, J. S., & Chepkwony, I. (2020). A Mathematical Model of Rabies Transmission Dynamics in Dogs Incorporating Public Health Education as a Control Strategy-A Case Study of Makueni County. Journal of Advances in Mathematics and Computer Science, 35(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Eze, O. C., Mbah, G. E., Nnaji, D. U., & Onyiaji, N. E. (2020). Mathematical modelling of transmission dynamics of rabies virus. International Journal of Mathematics Trends and Technology-IJMTT, 66.

- Thongtha, A., & Modnak, C. (2021). A mathematical modeling of rabies with vaccination and culling. International Journal of Biomathematics, 14(06), 2150039. [CrossRef]

- Pantha, B., Giri, S., Joshi, H. R., & Vaidya, N. K. (2021). Modeling transmission dynamics of rabies in Nepal. Infectious Disease Modelling, 6, 284-301. [CrossRef]

- Iggidr, A., Mbang, J., Sallet, G., & Tewa, J. J. (2007, August). Multi-compartment models. In Conference Publications (Vol. 2007, No. Special, pp. 506-519). Conference Publications.

- Edward, S., & Nyerere, N. (2015). A mathematical model for the dynamics of cholera with control measures. Applied and computational Mathematics, 4(2), 53-63. [CrossRef]

- Josephine, E. A. (2009). The basic reproduction number: Bifurcation and stability. A PGD thesis submitted to the African Institute of Mathematical Sciences.

- Hailemichael, D. D., Edessa, G. K., & Koya, P. R. (2023). Mathematical Modeling of Dog Rabies Transmission Dynamics Using Optimal Control Analysis. Contemporary Mathematics, 296-319.

- Asamoah, J. K. K., Oduro, F. T., Bonyah, E., & Seidu, B. (2017). Modelling of rabies transmission dynamics using optimal control analysis. Journal of Applied Mathematics, 2017.

- Ega, T. T., Luboobi, L., & Kuznetsov, D. (2015). Modeling the dynamics of rabies transmission with vaccination and stability analysis.

- Hailemichael, D. D., Edessa, G. K., & Koya, P. R. (2022). Effect of vaccination and culling on the dynamics of rabies transmission from stray dogs to domestic dogs. Journal of Applied Mathematics, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pontryagin, L.S. (2018). Mathematical theory of optimal processes. Routledge.

- Olaniyi, S. , Okosun, K. O., Adesanya, S. O., & Lebelo, R. S. (2020). Modelling malaria dynamics with partial immunity and protected travellers: optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis. Journal of biological dynamics, 14(1), 90-115. [CrossRef]

- Olaniyi, S.J.A.M. (2018). Dynamics of Zika virus model with nonlinear incidence and optimal control strategies. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci, 12(5), 969-982. [CrossRef]

- Modnak, C. (2017). Mathematical modelling of an avian influenza: optimal control study for intervention strategies. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci, 11(4), 1049-1057. [CrossRef]

- Hugo, A., Makinde, O. D., Kumar, S., & Chibwana, F. F. (2017). Optimal control and cost effectiveness analysis for Newcastle disease eco-epidemiological model in Tanzania. Journal of Biological Dynamics, 11(1), 190-209. [CrossRef]

- Lenhart, S., & Workman, J. T. (2007). Optimal control applied to biological models. Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Renalda, E. K., Kuznetsov, D., & Kreppel, K. (2020). Desirable Dog-Rabies Control Methods in an Urban setting in Africa-a Mathematical Model.

- Sharma, P. M., Dobhal, Y., Sharma, V., Kumar, S., & Gupta, S. (2015). Rabies: Understanding Neuropathology and Management. Int. J. Heal. Sci. Res, 5, 320-332.

| Parameter | Value | Interpretation | Source |

| 15900 | Dogs annual crop of newborn puppies | Assumed | |

| Prodromal dog-to-dog transmission rate | Assumed | ||

| Furious dog-to-dog transmission rate | Assumed | ||

| 0.17 | The incubation period of dog populations | [12] | |

| 0.821 | Rate of prodromal to furious stage | Assumed | |

| 0.25 | Pre-exposure prophylaxis for dogs | [11] | |

| 0.2 | Post-exposure prophylaxis for dogs | [11] | |

| 1 | The death rate of dogs due to rabies | [11] | |

| 0.056 | The natural death rate of dogs | [11] | |

| 0.01792 | Rabid dog culling rate | [20] | |

| 1 | Loss of immunity in dogs | [11] | |

| 112980 | Human annual birth | [12] | |

| Prodromal dog-to-human transmission rate | Assumed | ||

| Furious dog-to-human transmission rate | Assumed | ||

| 0.1667 | The incubation period of human populations | [12] | |

| 0.2 | Pre-exposure prophylaxis for humans | Assumed | |

| 0.2 | Post-exposure prophylaxis for humans | [11] | |

| 1 | The death rate of humans due to rabies | [11] | |

| 0.0074 | Natural death rate of humans | [11] |

| Strategy | Total infection Averted | Total cost ($) |

| 1 | 2,348,380 | 8,649,100 |

| 2 | 1,046,800 | 44,140,000 |

| 3 | 1,879,180 | 38,264,000 |

| 4 | 2,053,240 | 37,035,000 |

| 5 | 2,628,870 | 6,671,200 |

| Intervention | Total infection | Total cost | |

| Strategy | Averted | ($) | ICER |

| 2 | 1,046,800 | 44,140,000 | 42.16660 |

| 3 | 1,879,180 | 38,264,000 | -7.05928 |

| 4 | 2,053,240 | 37,035,000 | - |

| 1 | 2,348,380 | 8,649,100 | - |

| 5 | 2,628,870 | 6,671,200 | - |

| Intervention | Total infection | Total cost | |

| Strategy | Averted | ($) | ICER |

| 3 | 1,879,180 | 38,264,000 | 20.36207 |

| 4 | 2,053,240 | 37,035,000 | -7.06078 |

| 1 | 2,348,380 | 8,649,100 | - |

| 5 | 2,628,870 | 6,671,200 | - |

| Intervention | Total infection | Total cost | |

| Strategy | Averted | ($) | ICER |

| 4 | 2,053,240 | 37,035,000 | 18.03734 |

| 1 | 2,348,380 | 8,649,100 | -96.17775 |

| 5 | 2,628,870 | 6,671,200 | - |

| Intervention | Total infection | Total cost | |

| Strategy | Averted | ($) | ICER |

| 1 | 2,348,380 | 8,649,100 | 3.68301 |

| 5 | 2,628,870 | 6,671,200 | -7.051588 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).