Submitted:

27 March 2024

Posted:

28 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

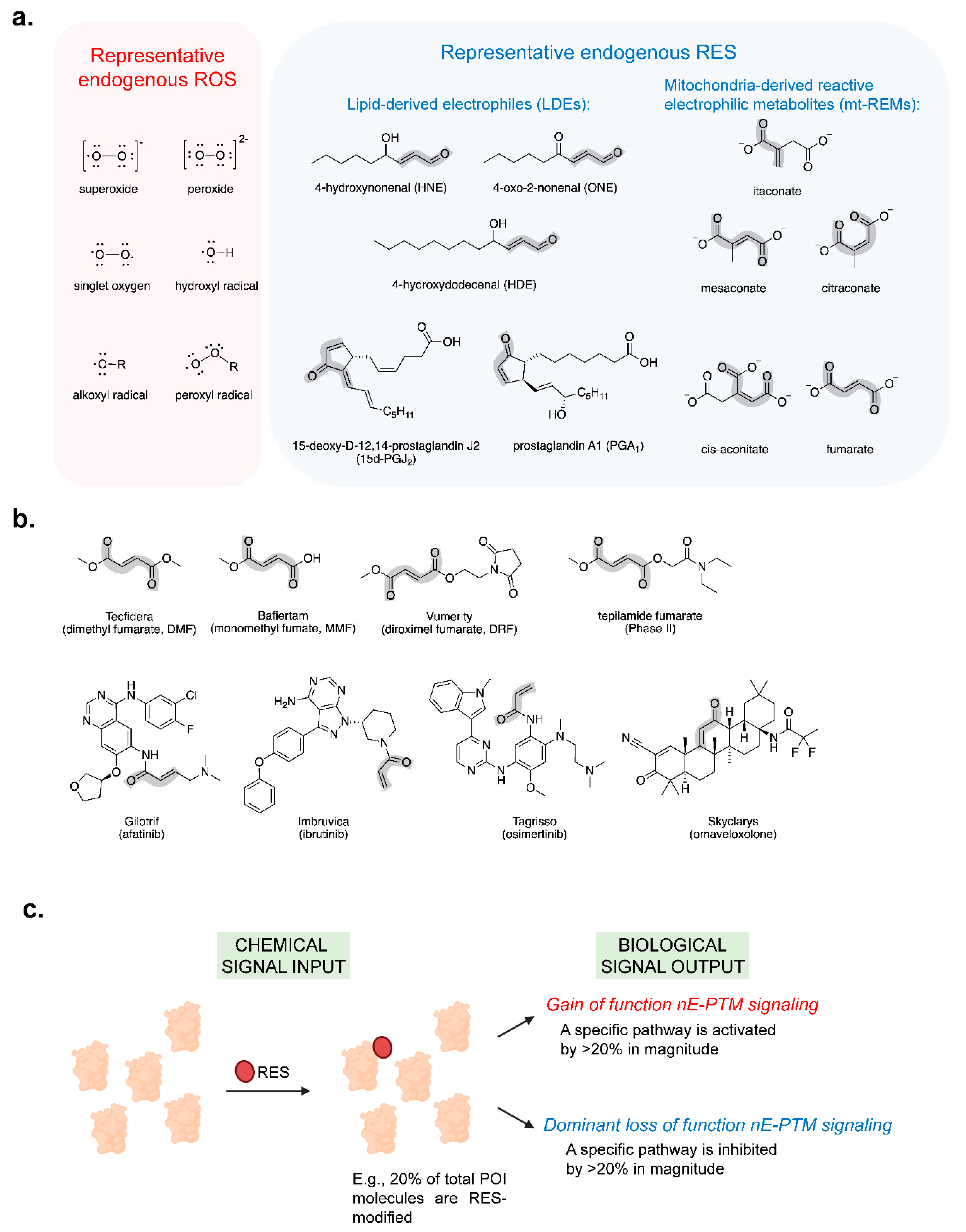

1. Introduction

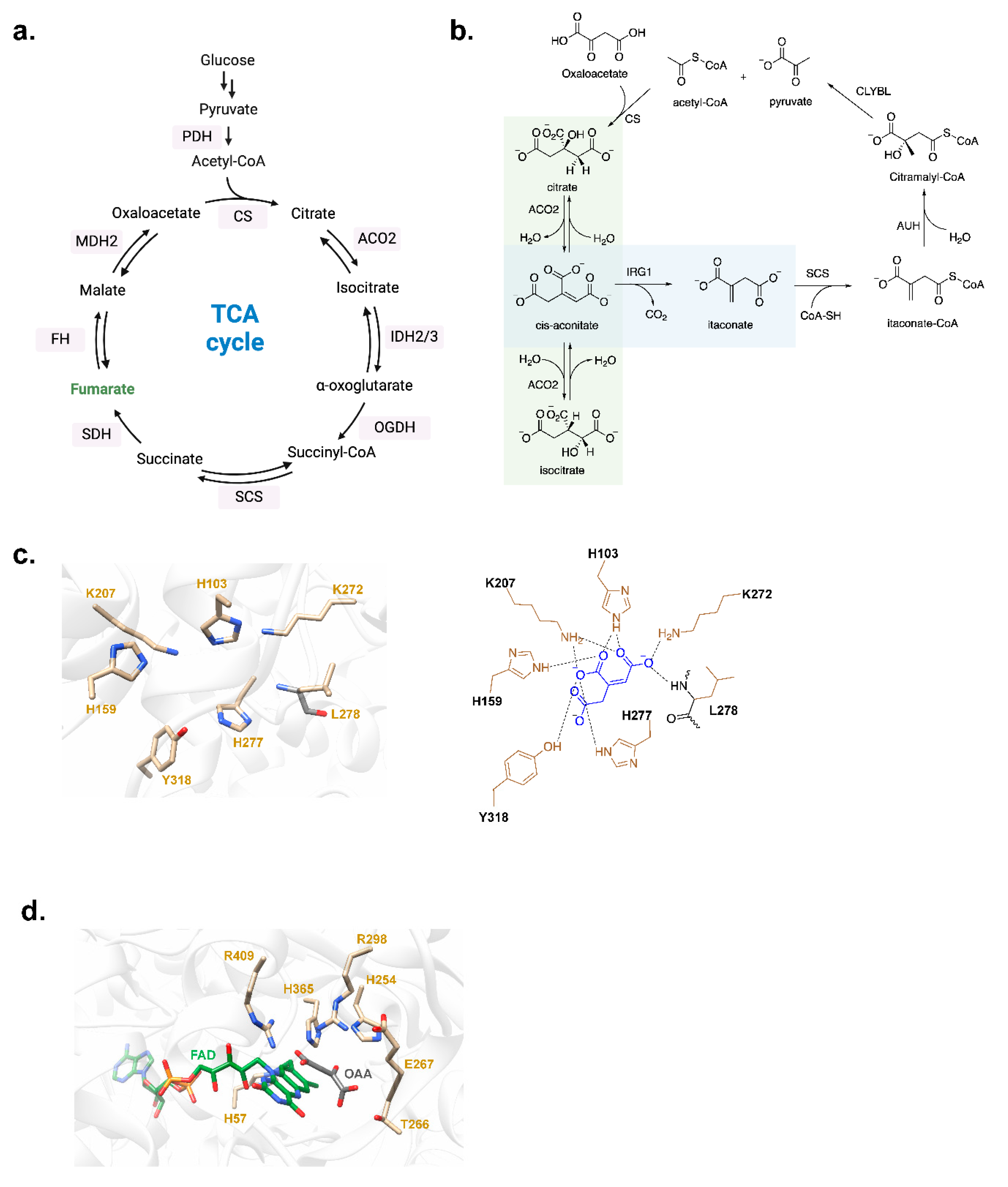

2. mt-REMs and Their Immunometabolic Signaling

2.1. Itaconate

2.1.1. Biosynthesis, Metabolic Transformations, and ‘Self-Modulation’

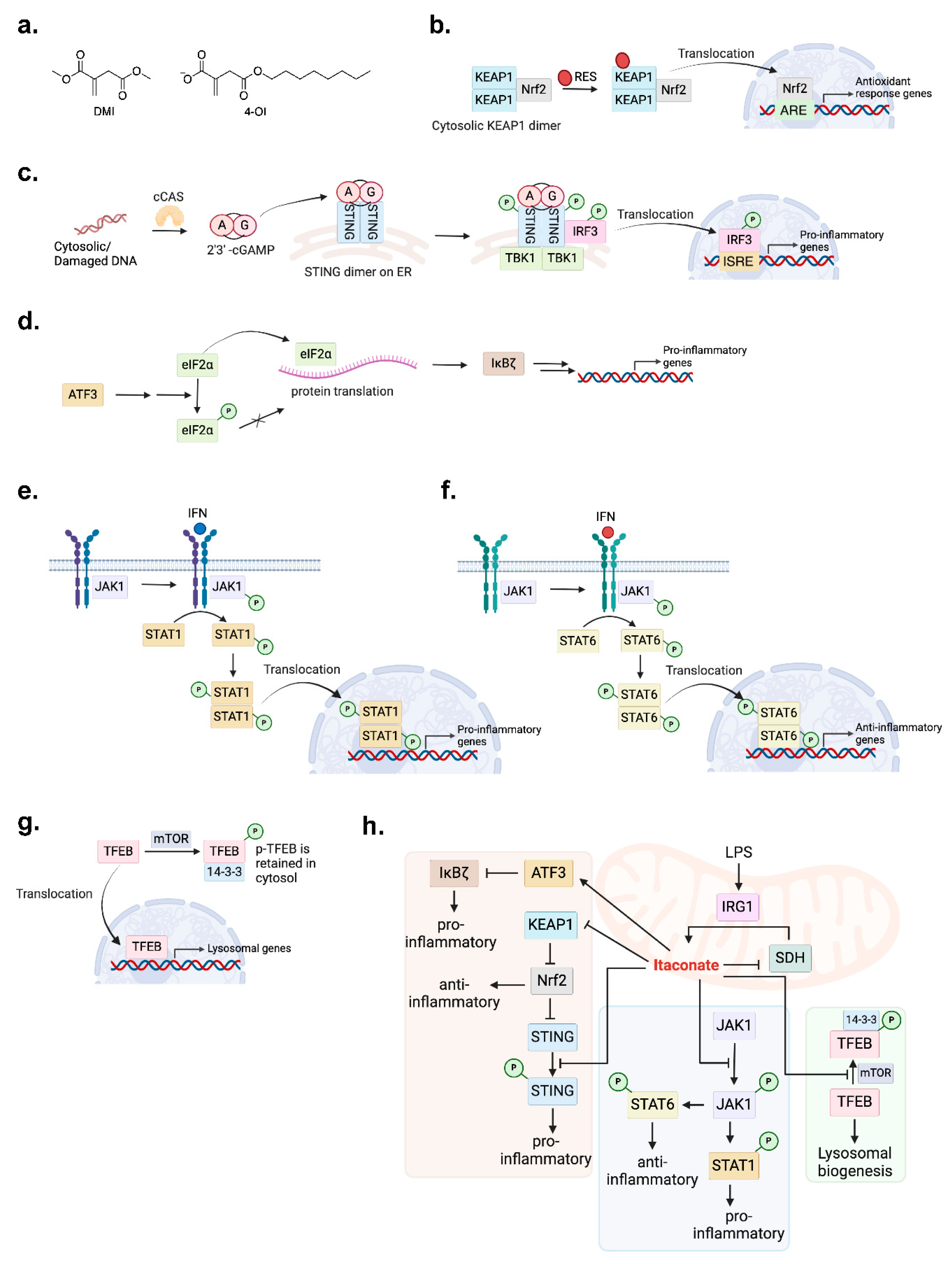

2.1.2. Immunomodulatory Activities

2.1.3. Mechanistic Pathway Actions

2.2. Mesaconate and Citraconate

2.3. Fumarate

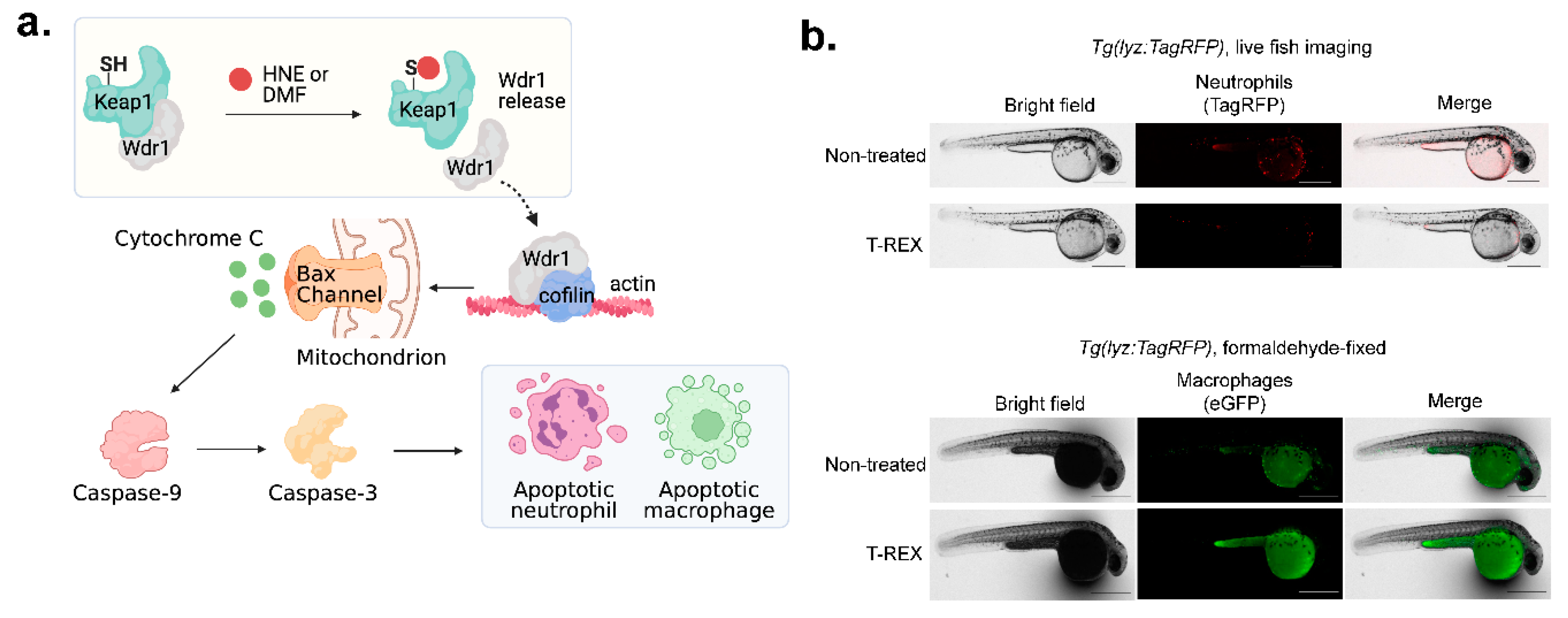

3. Chemical Biology Approaches to Study mt-REMs

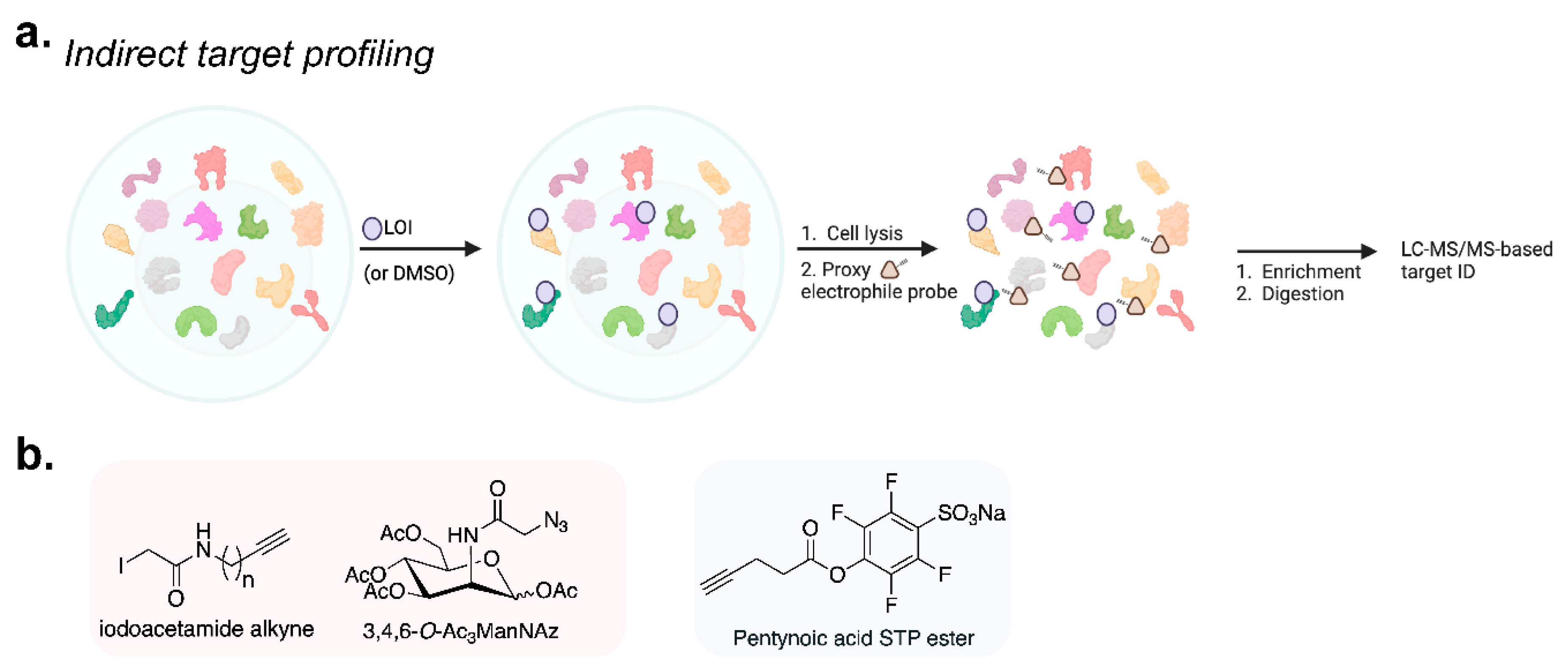

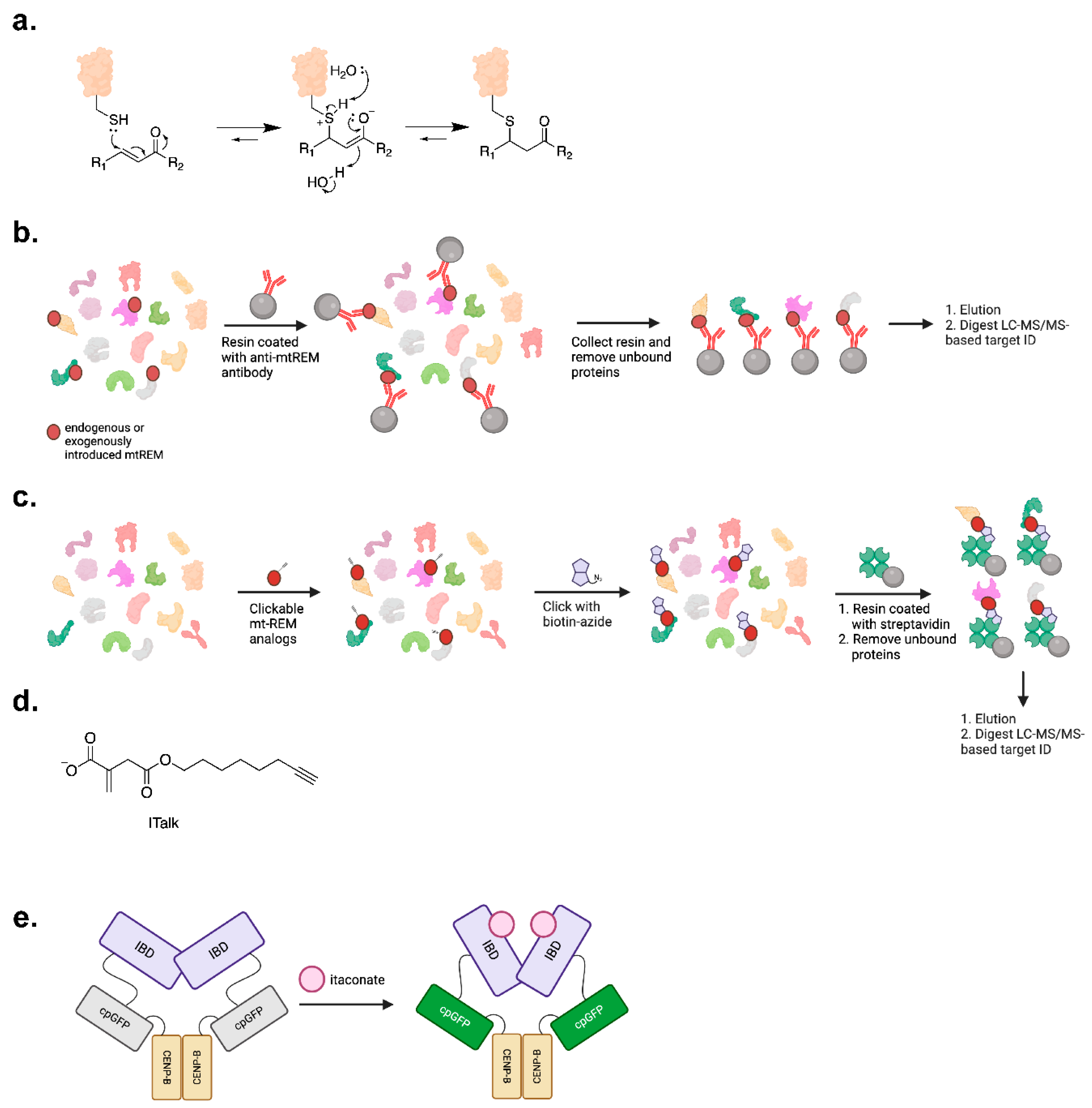

3.1. Protein Target-ID

3.2. Potential Biosensing of mt-REMs

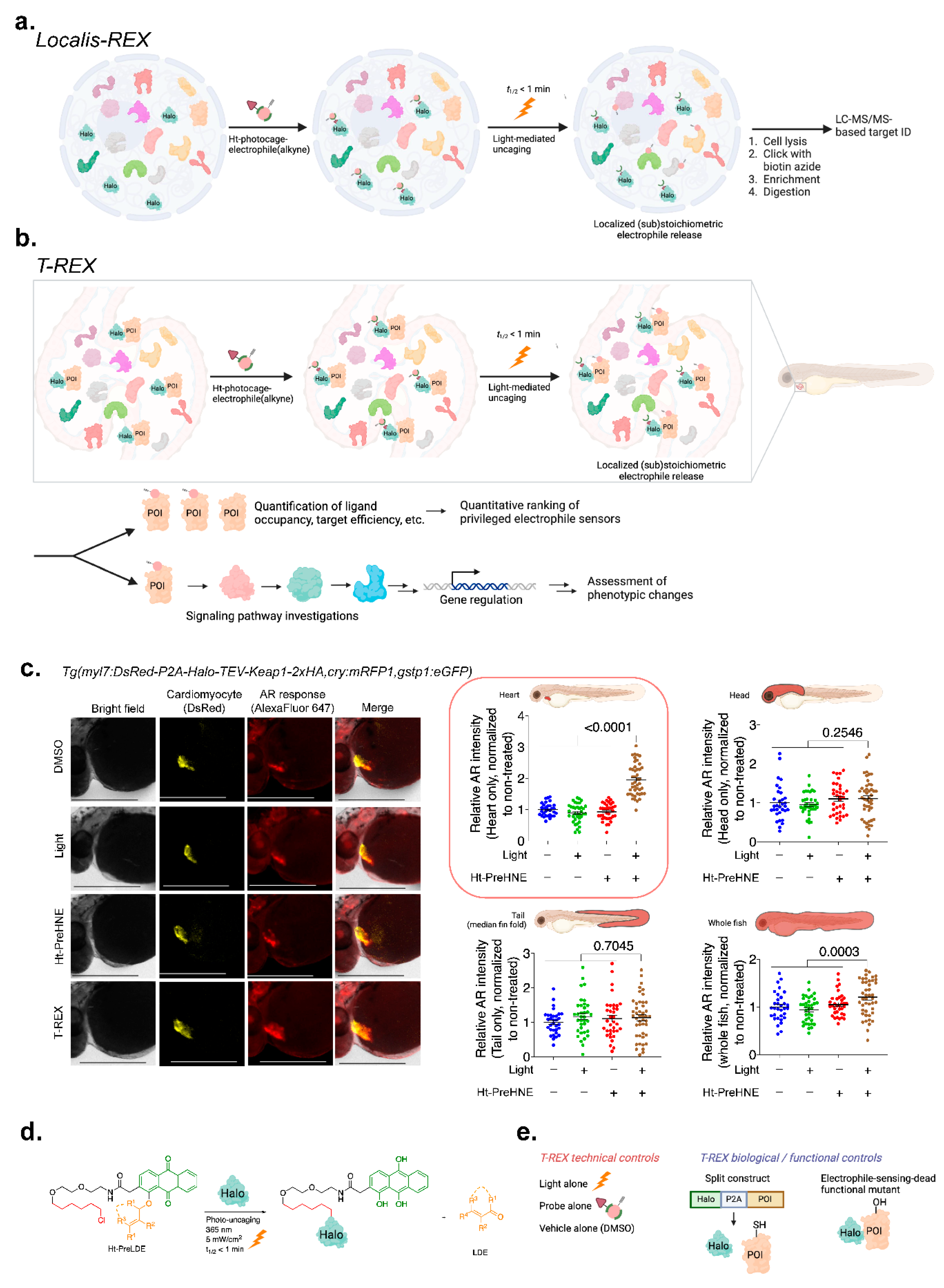

3.3. Precision Interrogations into Reactive-Metabolite-Directed nE-PTM Signaling

4. Outlook

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of interest

References

- Baker, S.A.; Rutter, J. Metabolites as signalling molecules. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2023, 24, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.J.C.; Huang, K.T.; Aye, Y. The not so identical twins: (dis)similarities between reactive electrophile and oxidant sensing and signaling. Chem Soc Rev 2021, 50, 12269–12291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H.; et al. Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvez, S.; Long, M.J.C.; Poganik, J.R.; Aye, Y. Redox Signaling by Reactive Electrophiles and Oxidants. Chem Rev 8798, 118, 8798–8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Long, M.J.C.; Aye, Y. Proteomics and Beyond: Cell Decision-Making Shaped by Reactive Electrophiles. Trends Biochem Sci 2019, 44, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.J.C.; Aye, Y. Privileged Electrophile Sensors: A Resource for Covalent Drug Development. Cell Chem Biol 2017, 24, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; et al. Precision Targeting of pten-Null Triple-Negative Breast Tumors Guided by Electrophilic Metabolite Sensing. ACS Cent Sci 2020, 6, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; et al. The signaling pathways and therapeutic potential of itaconate to alleviate inflammation and oxidative stress in inflammatory diseases. Redox Biol 2022, 58, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peace, C.G.; O’Neill, L.A. The role of itaconate in host defense and inflammation. J Clin Invest 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Dowerg, B.; Cordes, T. The yin and yang of itaconate metabolism and its impact on the tumor microenvironment. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2023, 84, 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.N.; Heiden, M.G.V. Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment. Annual Review of Cancer Biology 2020, 4, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angajala, A.; et al. Diverse Roles of Mitochondria in Immune Responses: Novel Insights Into Immuno-Metabolism. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, L.A.J.; Artyomov, M.N. Itaconate: the poster child of metabolic reprogramming in macrophage function. Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, W.; Kong, W.; Zeng, T. Itaconate: A Potent Macrophage Immunomodulator. Inflammation 2023, 46, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauble, H.; Stout, C.D. Steric and conformational features of the aconitase mechanism. Proteins 1995, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, J.; Wang, S.F.; Lardy, H.A. The metabolism of itaconic acid by liver mitochondria. J Biol Chem 1957, 229, 865–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; et al. Mesaconate is synthesized from itaconate and exerts immunomodulatory effects in macrophages. Nat Metab 2022, 4, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, E.L.; et al. Itaconate is an anti-inflammatory metabolite that activates Nrf2 via alkylation of KEAP1. Nature 2018, 556, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. ABCG2 is an itaconate exporter that limits antibacterial innate immunity by alleviating TFEB-dependent lysosomal biogenesis. Cell Metab 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, W.; Zhang, J.T. Human ABCG2: structure, function, and its role in multidrug resistance. Int J Biochem Mol Biol 2012, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sendra, M.; Saco, A.; Rey-Campos, M.; Novoa, B.; Figueras, A. Immune-responsive gene 1 (IRG1) and dimethyl itaconate are involved in the mussel immune response. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2020, 106, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strelko, C.L.; et al. Itaconic acid is a mammalian metabolite induced during macrophage activation. J Am Chem Soc 2011, 133, 16386–16389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelucci, A.; et al. Immune-responsive gene 1 protein links metabolism to immunity by catalyzing itaconic acid production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 7820–7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, D.; Lupien, A.; Behr, M.A.; Auclair, K. Effect of pH on the antimicrobial activity of the macrophage metabolite itaconate. Microbiology (Reading) 2021, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; et al. Targeting IRG1 reverses the immunosuppressive function of tumor-associated macrophages and enhances cancer immunotherapy. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadg0654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; et al. Myeloid-derived itaconate suppresses cytotoxic CD8(+) T cells and promotes tumour growth. Nat Metab 2022, 4, 1660–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming via ACOD1 depletion enhances function of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived CAR-macrophages in solid tumors. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulou, V.; et al. Itaconate Links Inhibition of Succinate Dehydrogenase with Macrophage Metabolic Remodeling and Regulation of Inflammation. Cell Metab 2016, 24, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordes, T.; et al. Immunoresponsive Gene 1 and Itaconate Inhibit Succinate Dehydrogenase to Modulate Intracellular Succinate Levels. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 14274–14284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipp, F.V.; Scott, D.A.; Ronai, Z.e.A.; Osterman, A.L.; Smith, J.W. Reverse TCA cycle flux through isocitrate dehydrogenases 1 and 2 is required for lipogenesis in hypoxic melanoma cells. Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research 2012, 25, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso, K.; et al. Itaconate ameliorates autoimmunity by modulating T cell imbalance via metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinz, A.; et al. Itaconate controls its own synthesis via feedback-inhibition of reverse TCA cycle activity at IDH2. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2022, 1868, 166530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, A.K.; et al. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity 2015, 42, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, S.T.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Sansom, O.J.; Campbell, A.D.; Morton, J.P. Therapeutic targeting of tumour myeloid cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2023, 23, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnewies, M.; et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruytinx, P.; Proost, P.; Van Damme, J.; Struyf, S. Chemokine-Induced Macrophage Polarization in Inflammatory Conditions. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, A.; Munari, F.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.; Scolaro, T.; Castegna, A. The Metabolic Signature of Macrophage Responses. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, T.; Metallo, C.M. Itaconate Alters Succinate and Coenzyme A Metabolism via Inhibition of Mitochondrial Complex II and Methylmalonyl-CoA Mutase. Metabolites 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Hakomaki, H.; Levonen, A.L. Electrophilic metabolites targeting the KEAP1/NRF2 partnership. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2024, 78, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poganik, J.R.; Aye, Y. Electrophile Signaling and Emerging Immuno- and Neuro-modulatory Electrophilic Pharmaceuticals. Front Aging Neurosci 2020, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayalan Naidu, S.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. Omaveloxolone (Skyclarys(TM)) for patients with Friedreich’s ataxia. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2023, 44, 394–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, E.H.; et al. Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. The Nrf2 regulatory network provides an interface between redox and intermediary metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci 2014, 39, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olagnier, D.; et al. Nrf2 negatively regulates STING indicating a link between antiviral sensing and metabolic reprogramming. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motwani, M.; Pesiridis, S.; Fitzgerald, K.A. DNA sensing by the cGAS-STING pathway in health and disease. Nat Rev Genet 2019, 20, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; et al. 4-octyl itaconate as a metabolite derivative inhibits inflammation via alkylation of STING. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 112145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambouskova, M.; et al. Electrophilic properties of itaconate and derivatives regulate the IkappaBzeta-ATF3 inflammatory axis. Nature 2018, 556, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; et al. The central inflammatory regulator IkappaBzeta: induction, regulation and physiological functions. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1188253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElAzzouny, M.; et al. Dimethyl Itaconate Is Not Metabolized into Itaconate Intracellularly. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 4766–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runtsch, M.C.; et al. Itaconate and itaconate derivatives target JAK1 to suppress alternative activation of macrophages. Cell Metab 2022, 34, 487–501 e488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vale, K. Targeting the JAK-STAT pathway in the treatment of ‘Th2-high’ severe asthma. Future Med Chem 2016, 8, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; et al. From the regulatory mechanism of TFEB to its therapeutic implications. Cell Death Discov 2024, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; et al. Itaconate is a lysosomal inducer that promotes antibacterial innate immunity. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 2844–2857 e2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; et al. Citraconate inhibits ACOD1 (IRG1) catalysis, reduces interferon responses and oxidative stress, and modulates inflammation and cell metabolism. Nat Metab 2022, 4, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onuora, S. Mitochondrial fumarate implicated in inflammation. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 2023, 19, 257–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seton-Rogers, S. Functions of fumarate. Nature Reviews Cancer 2016, 16, 617–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrowietz, U.; et al. Tepilamide Fumarate (PPC-06) Extended Release Tablets in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis: Safety and Efficacy Results from the Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled AFFIRM Study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2022, 15, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sullivan Lucas, B.; et al. The Proto-oncometabolite Fumarate Binds Glutathione to Amplify ROS-Dependent Signaling. Molecular Cell 2013, 51, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menko, F.H.; et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer 2014, 13, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolay, J.P.; et al. Dimethyl fumarate treatment in relapsed and refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a multicenter phase 2 study. Blood 2023, 142, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braley, T.J.; et al. A randomized, subject and rater-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of dimethyl fumarate for obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2018, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, C.L.; et al. Treatment with dimethyl fumarate reduces the formation and rupture of intracranial aneurysms: Role of Nrf2 activation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020, 40, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meili-Butz, S.; et al. Dimethyl fumarate, a small molecule drug for psoriasis, inhibits Nuclear Factor-kappaB and reduces myocardial infarct size in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2008, 586, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campolo, M.; et al. The Neuroprotective Effect of Dimethyl Fumarate in an MPTP-Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease: Involvement of Reactive Oxygen Species/Nuclear Factor-kappaB/Nuclear Transcription Factor Related to NF-E2. Antioxid Redox Signal 2017, 27, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lastres-Becker, I.; et al. Repurposing the NRF2 Activator Dimethyl Fumarate as Therapy Against Synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016, 25, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, X.; et al. Dimethyl fumarate attenuates 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells and in animal model of Parkinson’s disease by enhancing Nrf2 activity. Neuroscience 2015, 286, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkutewicz, I.; et al. Dimethyl fumarate attenuates intracerebroventricular streptozotocin-induced spatial memory impairment and hippocampal neurodegeneration in rats. Behav Brain Res 2016, 308, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkutewicz, I.; et al. Age-dependent effects of dimethyl fumarate on cognitive and neuropathological features in the streptozotocin-induced rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res 2018, 1686, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; et al. Combination of the Immune Modulator Fingolimod With Alteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Pilot Trial. Circulation 2015, 132, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, D.; et al. Phase I trial of dimethyl fumarate, temozolomide, and radiation therapy in glioblastoma. Neurooncol Adv 2020, 2, vdz052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze-Topphoff, U.; et al. Dimethyl fumarate treatment induces adaptive and innate immune modulation independent of Nrf2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 4777–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.J.C.; Rogg, C.; Aye, Y. An Oculus to Profile and Probe Target Engagement In Vivo: How T-REX Was Born and Its Evolution into G-REX. Acc Chem Res 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvez, S.; et al. T-REX on-demand redox targeting in live cells. Nat Protoc 2016, 11, 2328–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.T.; et al. Z-REX: shepherding reactive electrophiles to specific proteins expressed tissue specifically or ubiquitously, and recording the resultant functional electrophile-induced redox responses in larval fish. Nat Protoc 2023, 18, 1379–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poganik, J.R.; et al. Wdr1 and cofilin are necessary mediators of immune-cell-specific apoptosis triggered by Tecfidera. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, K.; Tong, K.I.; Yamamoto, M. Molecular mechanism activating Nrf2-Keap1 pathway in regulation of adaptive response to electrophiles. Free Radic Biol Med 2004, 36, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cravatt, B.F.; Wright, A.T.; Kozarich, J.W. Activity-based protein profiling: from enzyme chemistry to proteomic chemistry. Annu Rev Biochem 2008, 77, 383–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blewett, M.M.; et al. Chemical proteomic map of dimethyl fumarate-sensitive cysteines in primary human T cells. Sci Signal 2016, 9, rs10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, R.A.; et al. A chemoproteomic portrait of the oncometabolite fumarate. Nat Chem Biol 2019, 15, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, H.S.; Yan, T.; Backus, K.M. SP3-FAIMS-Enabled High-Throughput Quantitative Profiling of the Cysteinome. Curr Protoc 2022, 2, e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradova, E.V.; et al. An Activity-Guided Map of Electrophile-Cysteine Interactions in Primary Human T Cells. Cell 2020, 182, 1009–1026 e1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; et al. S-glycosylation-based cysteine profiling reveals regulation of glycolysis by itaconate. Nat Chem Biol 2019, 15, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasov, M.E.; et al. A proteome-wide atlas of lysine-reactive chemistry. Nat Chem 2021, 13, 1081–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poganik, J.R.; Long, M.J.C.; Aye, Y. Getting the Message? Native Reactive Electrophiles Pass Two Out of Three Thresholds to be Bona Fide Signaling Mediators. Bioessays 2018, 40, e1700240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannahill, G.M.; et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF-1alpha. Nature 2013, 496, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; et al. Discovery of Itaconate-Mediated Lysine Acylation. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145, 12673–12681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Quantitative Profiling of Protein Carbonylations in Ferroptosis by an Aniline-Derived Probe. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140, 4712–4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, W.; et al. Chemoproteomic Profiling of Itaconation by Bioorthogonal Probes in Inflammatory Macrophages. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142, 10894–10898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.J.C.; Liu, J.; Aye, Y. Finding a vocation for validation: taking proteomics beyond association and location. RSC Chem Biol 2023, 4, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; et al. Function-guided proximity mapping unveils electrophilic-metabolite sensing by proteins not present in their canonical locales. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.J.C.; Miranda Herrera, P.A.; Aye, Y. Hitting the Bullseye: Endogenous Electrophiles Show Remarkable Nuance in Signaling Regulation. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2022, 35, 1636–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.F.; et al. Proximity labeling in mammalian cells with TurboID and split-TurboID. Nature Protocols 2020, 15, 3971–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, V.; et al. Spatially resolved proteomic mapping in living cells with the engineered peroxidase APEX2. Nature Protocols 2016, 11, 456–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geri, J.B.; et al. Microenvironment mapping via Dexter energy transfer on immune cells. Science 2020, 367, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.J.C.; Assari, M.; Aye, Y. Hiding in Plain Sight: The Issue of Hidden Variables. ACS Chem Biol 2022, 17, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Haegele, J.A.; Disare, M.T.; Lin, Q.; Aye, Y. A generalizable platform for interrogating target- and signal-specific consequences of electrophilic modifications in redox-dependent cell signaling. J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137, 6232–6244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffrey, S.R. RNA-Based Fluorescent Biosensors for Detecting Metabolites in vitro and in Living Cells. Adv Pharmacol 2018, 82, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohata, J.; Bruemmer, K.J.; Chang, C.J. Activity-Based Sensing Methods for Monitoring the Reactive Carbon Species Carbon Monoxide and Formaldehyde in Living Systems. Accounts of Chemical Research 2019, 52, 2841–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyan, W.; Zhang, D.Y.; Lippard, S.J.; Radford, R.J. Reaction-based fluorescent sensor for investigating mobile Zn2+ in mitochondria of healthy versus cancerous prostate cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; et al. A genetically encoded fluorescent biosensor for detecting itaconate with subcellular resolution in living macrophages. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 6562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.J.; et al. beta-TrCP1 Is a Vacillatory Regulator of Wnt Signaling. Cell Chem Biol 2017, 24, 944–957 e947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.J.; et al. Akt3 is a privileged first responder in isozyme-specific electrophile response. Nat Chem Biol 2017, 13, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hall-Beauvais, A.; et al. Z-REX uncovers a bifurcation in function of Keap1 paralogs. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; et al. Crystal structure of cis-aconitate decarboxylase reveals the impact of naturally occurring human mutations on itaconate synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 20644–20654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Maklashina, E.; Cecchini, G.; Iverson, T.M. The roles of SDHAF2 and dicarboxylate in covalent flavinylation of SDHA, the human complex II flavoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 23548–23556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).